Abstract

Air pollution has been increasingly associated with heightened mental health risks. However, there is a scarcity of nationwide research addressing the mental health issue of rural older adults, as well as a lack of thorough investigations into the underlying issues of health inequality. This study leverages data from the 2014–2018 “China Longitudinal Ageing Social Survey” to conduct a comprehensive longitudinal analysis utilizing latent growth models and random intercept cross-lagged panel models. The findings reveal a concerning trend of worsening depressive symptoms among rural Chinese older adults, with an average annual growth rate of 1.9%. PM2.5 concentrations significantly contribute to depression in this population. PM2.5 pollution exhibit a indicative association with depressive symptoms in the lagged periods, with standard influence coefficients of 0.089 and 0.073, respectively. However, this association is only observed in middle- and low-income groups, with no evidence found in high-income groups. Data suggest that lower income levels heighten vulnerability to the adverse effects of PM2.5 on mental health, with low-income rural older adults being the most severely affected subgroup. This implies that there are health inequalities related to the impact of air pollution among elderly populations of different income levels. Consequently, targeted interventions aimed at addressing the disparities in rural are essential for mitigating these inequalities and improving health outcomes in this vulnerable population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mental health issues are frequently overlooked by the public, yet their detrimental effects can be significantly more severe (Wickstead and Furnham, 2017; Carmichael et al. 2019). According to the World Health Organization’s “World Mental Health Report,” approximately one in eight individuals globally is affected by mental health disorders (WHO, 2017). Among these, depression stands out as one of the most prevalent mental health conditions worldwide and has emerged as a critical concern in the context of global aging. In China, mental health challenges, particularly depression, have become pressing public health issues for older adults. This concern is especially pronounced in rural regions, where older adults often face more severe manifestations of depression. The report titled “The Path to Healthy Ageing in China” indicates that 25.2% of rural older adults frequently experience symptoms of depression, such as feelings of sadness and loss, which is 5.3% higher than the rate observed among their urban counterparts (Chen et al. 2022). This disparity can be attributed to several factors, including significant rural depopulation and limited access to healthcare resources (Wang et al. 2019; Ye et al. 2024). Consequently, it is crucial to increase awareness and attention to the issue of depression among the rural elderly population in China.

Over the past two decades, systematic disparities have persisted among vulnerable social groups concerning social status, economic income, and health security (Sabo et al. 2015). From the standpoint of health equity, these marginalized populations face significant obstacles in achieving good health and accessing healthcare services, with the issue of health inequality being particularly pronounced in developing countries (Chancel et al. 2022; Tam and Chan, 2017). In rural China, relative poverty continues to be a critical issue, resulting in significant health disparities among older adults within the same region. Low-income rural older adults often lack adequate pension support to cover their basic living expenses, compelling them to remain engaged in agricultural activities to sustain their livelihoods into later life. Furthermore, medical coverage for this demographic remains insufficient, exacerbated by a scarcity of essential medical resources (Cai et al. 2017). A few scholars have identified inequalities in mental health among older adults, where the greater the income inequality is, the more likely low-income groups are to suffer from depression (Hou et al. 2022; Park and Seo, 2021; Jun et al. 2021). This phenomenon may be attributed to the economic burdens borne by low-income older adults, which can lead to sustained life stress and exacerbate the occurrence of depression (Lei et al. 2022; Pan et al. 2021; Wang et al. 2020). Therefore, it is imperative that this research addresses the social issue of health inequality across different income groups and prioritizes the investigation of the elevated prevalence of depression among rural older adults. Such efforts are crucial for enhancing the mental well-being of rural populations and ensuring that environmental factors do not inadvertently perpetuate health disparities among specific groups, ultimately contributing to reduced inequalities between diverse populations.

In the field of environmental health research, environmental perception theory explores how individuals’ emotions are shaped by their surroundings in specific contexts, which can subsequently elicit physiological responses from the immune system (Xue et al. 2014; Zeng et al. 2020). It is well-documented that suboptimal environmental conditions can heighten stress and anxiety among older adults, and the relationship between air pollution and depression in this demographic has been extensively investigated (Cao et al. 2023; Gu et al. 2019). While air quality management initiatives in urban areas of China have yielded positive results, the issue of PM2.5 pollution in rural regions remains a considerable challenge. The primary sources of PM2.5 in these rural areas may differ significantly from those found in urban environments. Notably, reliance on coal for heating and the incineration of agricultural residues are significant contributors to PM2.5 emissions. Moreover, the rapid pace of development in China has led to a new form of secondary pollution in certain rural areas, stemming from industrialization and increased vehicular traffic (Aunan et al. 2019). Investigating PM2.5 levels in rural settings is crucial for understanding and analyzing the potential impacts of pollution on mental health, thereby providing a scientific foundation for the realization of a Healthy China initiative. As such, this study prioritizes PM2.5 as a central focus of air pollution research. Among various air pollutants, PM2.5 is recognized as one of the most detrimental types of particulate matter to human health, significantly impacting depression rates among older adults. Research indicates that higher concentrations of PM2.5 correlate with an increased likelihood of depression within this demographic (Zhang et al. 2020; Chen et al. 2021; Zheng et al. 2019). Furthermore, environmental psychology underscores that health responses resulting from environmental interactions necessitate a dual emotional analysis (Clayton et al. 2016). The first aspect involves direct responses to simple environmental stimuli, such as the physical health impacts of PM2.5. The second aspect encompasses a more profound erosion of well-being, wherein PM2.5 negatively affects residents’ mental health through both its physical health repercussions and the accompanying stressors they create.

Scholars have also found that the mechanism through which PM2.5 pollution impacts depression among older adults is multifaceted (Zheng et al. 2019; Zijlema et al. 2016; Fan et al. 2020; Shi et al. 2020). For example, long-term haze and gloomy weather can affect older adults’ emotions and reduce social activities (Zheng et al. 2019; Zijlema et al. 2016). Such gloomy weather may evoke feelings of loss, which can subsequently manifest as depressive symptoms (Fan et al. 2020; Shi et al. 2020). Moreover, severe air pollution can deter social interactions and physical activities, thereby heightening the likelihood of emotional instability and exacerbating depressive symptoms in individuals who may already be experiencing marginal psychological issues (Gu et al. 2019; Zheng et al. 2019). Additionally, PM2.5 pollution is known to induce oxidative stress and various inflammatory responses in the body, conditions closely linked to depression (Bao et al. 2017; Sabeti et al. 2021). Prolonged exposure to elevated PM2.5 concentrations can also lead to chronic health conditions such as asthma, bronchitis, cardiovascular diseases, and hypertension (Xing et al. 2016; Yang et al. 2020; Liang et al. 2014; David et al. 2014; Guan et al. 2016). As the physical health of older adults deteriorates due to long-term exposure to PM2.5, they may experience a loss of hope regarding their health and well-being, which can gradually lead to the development of depressive symptoms (Yao et al. 2022; Hautekiet et al. 2022). Consequently, the impact of environmental pollution, particularly PM2.5, on depression among older adults is significant and warrants serious consideration. It is essential to guide individuals’ perceptions of their environment in ways that promote health.

As the exploration of the relationship between pollution and depression among older adults continues, some scholars have noted that older adults with low socioeconomic status are particularly vulnerable to the effects of PM2.5 pollution (Pun et al. 2017; Xue et al. 2021). This increased susceptibility may be attributed to their substandard living conditions and lifestyle habits, which can lead to higher concentrations of PM2.5, thereby triggering oxidative stress and inflammation that contribute to depression. Income, a critical component of socioeconomic status, has been recognized as an important factor in this research. However, current studies have primarily focused on individuals across varying socioeconomic statuses, often neglecting the implications of income inequality on health equity among different demographic groups. Notably, there has been insufficient attention paid to the rural elderly population. Therefore, it is imperative to further investigate the impact of PM2.5 on depression among rural older adults across different income brackets to uncover issues related to social health inequality. This research will enhance our understanding of the health status of older adults in low-income rural areas and promote social equity and health justice.

Currently, the majority of research on the impact of PM2.5 on depression has predominantly focused on urban older adults, often overlooking their rural counterparts. Paradoxically, rural older adults may experience more acute PM2.5 pollution, leading to heightened levels of depression (Aunan et al. 2019; Yun et al. 2020). Although there has been a notable annual decline in air pollution levels in China, the PM2.5 concentration remains above the standards set by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2021; Chan and Yao, 2008; Yao et al. 2020). In rural areas, industrialization and development inevitably exacerbate resource constraints, contributing to environmental degradation and pollution (Aunan et al. 2019). Compared to urban settings, the efforts to control air pollution in rural areas are generally weaker, resulting in less substantial reductions in pollution levels. Consequently, pollution levels in rural and urban areas are gradually converging, with certain rural regions exhibiting air quality that is worse than that of many urban centers (Tilt, 2013; Tian et al. 2015). Some studies even suggest that the risk of deaths attributable to PM2.5 is higher in rural areas than in urban zones (Yun et al. 2020; Zhao et al. 2021; Liu, 2019; Liu et al. 2021). In light of these findings, there is an urgent need to examine the impact of PM2.5 on depression among rural older adults.

Notably, existing studies on the impact of PM2.5 on depression among Chinese older adults have been mostly cross-sectional studies (Shi et al. 2020; Yao et al. 2022; Wang et al. 2019). However, relying solely on cross-sectional studies may not be accurate to determine the relationships between PM2.5 and mental health, nor can other potential influencing factors be excluded, and there is still a problem of sample selection bias. In the published literature, we found that fewer longitudinal studies have focused on the impact of PM2.5 on depression among older adults (Wang et al. 2020; Xue et al. 2021). Wang et al. (2020) found that depressive symptoms among older adults increased in conjunction with rising annual PM2.5 concentrations, suggesting that higher PM2.5 levels could exacerbate depressive symptoms by diminishing physical activity and social engagement. Xue et al. (2021) based on the three-year trajectory of PM2.5 pollution and depression among Chinese older adults, demonstrated a sustained impact of PM2.5 on depression among older adults. Additionally, Xue et al. (2021) also indicated that clean air policies could enhance the mental health of older adults not only in China but also in other middle- and low-income countries. However, there is still a lack of relevant longitudinal studies focusing on rural China, particularly those that integrate issues of health inequality to investigate the impact of PM2.5 on depression among older adults across different income groups. This gap in research underscores the necessity for targeted investigations into the unique challenges faced by rural older adults in relation to PM2.5 exposure and mental health outcomes.

To address the identified knowledge gaps, this study integrates rural PM2.5 pollution and social issues related to health inequality to conduct an in-depth analysis. Utilizing data from the China Longitudinal Ageing Social Survey (CLASS) spanning from 2014 to 2018, the study employed latent growth models to assess the trajectories of depression among rural older adults and PM2.5 pollution. Specifically, a random intercept cross-lagged model was used to identify the indicative associations between PM2.5 pollution and depression among rural older adults, while also evaluating differences across various income groups to analyze the impact of pollution on health disparities. This research contributes to existing theoretical and practical frameworks in three significant ways. First, it enhances the development of environmental perception theory and environmental psychology by providing longitudinal insights into the indicative associations between PM2.5 pollution and depression among rural older adults. Second, the study highlights a societal issue of health inequality stemming from environmental hazards, thereby offering new avenues for promoting equitable health outcomes. Third, this research seeks to draw the attention of policymakers to the persistent health inequalities faced by vulnerable populations. By deepening the incorporation of humanistic perspectives in the realms of environmental protection and public health, it aims to foster the development of truly elder-friendly rural communities and promote social equity.

Based on a thorough review and analysis, the study systematically explores and addresses the following research questions:

-

1.

What are the trajectories of depression and PM2.5 pollution among rural older adults from 2014 to 2018?

-

2.

Does PM2.5 pollution have significant indicative associations with depression among rural older adults?

-

3.

Are there health inequalities in the impact of PM2.5 pollution on depression among rural older adults with different incomes?

Methods

Data and samples

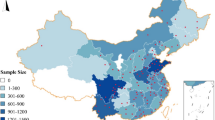

This research utilized data from the “China Longitudinal Ageing Social Survey” (CLASS), a comprehensive nationwide longitudinal study conducted entirely by the Renmin University of China. The respondents included Chinese older adults aged 60 and above, and the survey encompassed 29 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities across China. The CLASS project systematically collects data on the health, living environments, and living conditions of older adults in China, thereby providing essential theoretical support and empirical evidence to address the challenges posed by an aging population. The CLASS project initiated its first nationwide baseline survey in 2014, followed by two tracking surveys in 2016 and 2018. Despite relatively high sample attrition rates in both baseline and follow-up surveys, a comparison of the demographic characteristics of the valid samples indicates a general consistency, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The mechanism behind sample attrition appears largely random, ensuring that the rural older adults retained in the two tracking surveys possess a commendable degree of representativeness. The study utilized a multi-stage sampling method, using the map addresses of each village or community as the sampling frame and randomly selecting households. Within each household, individuals aged 60 and above were sampled, and one participant was selected for a face-to-face interview. In the 2014 baseline survey, this research obtained a total of 4603 questionnaires from rural residents. In the 2016 follow-up survey, 3376 rural older adults participated in the 2014 baseline survey; while in the 2018 survey, 2103 rural older adults participated in the 2016 and 2014 surveys. Ultimately, the study focused on the sample of rural older adults who participated in all three surveys. After excluding cases with missing income data, we obtained a final total of 1833 valid samples. Our research examined disparities in income levels based on relative income. The income levels of rural older adults were classified into three categories according to their effective annual income: low-income (0–30% percentile, <1444 CNY), medium-income (30–70% percentile, 1444–5564 CNY), and high-income (70–100% percentile, >5564 CNY). The final analysis revealed 550 samples of low-income rural older adults, 733 samples of medium-income rural older adults, and 550 samples of high-income rural older adults.

Measurement variable selection

Depression among rural older adults

Depression has emerged as a significant public health concern (Wickstead and Furnham, 2017; Carmichael et al. 2019). In this study, the dependent variable is depression, which is measured using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as revised by Cong and Silverstein (Cong and Silverstein, 2008). Older adults were asked to report the frequency with which they experienced six negative emotions over the past week, specifically: (1) Do you feel lonely? (2) Do you feel sad? (3) Do you have no appetite? (4) Do you have trouble sleeping? (5) Do you feel worthless? (6) Do you feel that you have nothing to do? Each item offers three frequency options to choose from: 1=Rarely or none of the time, 2=Some of the time, 3=Most of the time, with higher scores indicating higher levels of depression. The scale demonstrates robust reliability and validity (Vilagut et al. 2016; Lewinsohn et al. 1997). In this study, the Cronbach’s α coefficients for the CES-D scale at various time points were 0.989 (2014), 0.972 (2016), and 0.984 (2018), indicating strong reliability and high consistency among the six items. To streamline the analysis, this study considers the six items as a single construct. The scores for these items are summed to produce a total CES-D score, which ranges from 6 to 18. A higher total score signifies greater levels of depression and poorer mental health status.

Pollution (PM2.5)

This study utilized global ground observation PM2.5 concentration raster data (version V5.GL.02), developed by the Atmospheric Composition Analysis Group at Washington University in St. Louis, USA. This dataset features a spatial resolution of 1 km × 1 km. The specific development method is as follows: First, the GEOS-Chem chemical transport model simulates the surface PM2.5 concentration, integrating aerosol optical depth (AOD) data obtained from satellite instruments, including the moderate-resolution imaging spectroradiometer (MODIS), the multi-angle imaging spectroRadiometer (MISR), and the sea-viewing wide field-of-view sensor (SeaWiFS). Subsequently, the GEOS-Chem simulation values were verified and calibrated using geographically weighted regression based on ground observation data from the China Atmospheric Monitoring Network. This process enhances the rigor and credibility of the resulting data. The latest version of the dataset not only demonstrates strong predictive performance for annual average surface PM2.5 estimates but also exhibits high congruence with globally distributed ground-based monitoring systems. The dataset is available at the following website: https://sites.wustl.edu/acag/datasets/surface-pm2-5/. The accuracy of the PM2.5 raster data in V5.GL.02 has been validated by multiple scholars and has been employed in various studies examining the long-term health impacts of PM2.5 exposure (Van Donkelaar et al. 2021; Ali et al. 2023).

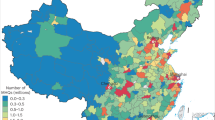

In the CLASS dataset, 1833 rural older adults participated across three surveys conducted in 82 counties in China. This research aggregated monthly PM2.5 exposure concentrations from a 1 km × 1 km spatial resolution to the county level by averaging the grid estimates across the 82 county polygons. This methodological approach enabled us to derive the annual average PM2.5 exposure at the county level during the study period (2014, 2016, 2018).

Covariates

To account for potential confounding factors, this research adopted a two-level approach, controlling for variables at both the individual and county levels. The covariate data were drawn from baseline measurements collected in 2014. At the individual level, the control variables included gender (0 = Male; 1 = Female), education level (1 = Illiterate; 2 = Private school/literacy class; 3 = Primary school; 4 = Junior high school; 5 = High school/technical school; 6 = College or above), age, number of cohabitants, chronic illness (0 = No; 1 = Yes), social participation (assessed via seven items encompassing community patrolling, caregiving for other elderly individuals, environmental sanitation efforts, dispute mediation, companionship, technical volunteer services, and caregiving for children; each item was scored 0 = not participated, 1 = participated, yielding a total score range of 0 to 7), and social network (comprising six items: the number of times meeting with family/relatives, the number of times having heartfelt conversations with family/relatives, the number of times receiving help from family/relatives, the number of times meeting with friends, the number of times having heartfelt conversations with friends, and the number of times receiving help from friends; each item was scored as 0 = none, 1 = once, 2 = twice, 3 = 3–4times, and 5 = 5–8times, with a cumulative score range of 0 to 30). At the county level, the control variable was per capita GDP (CNY), measured in hundreds of yuan.

Research design and analytical methods

Research design and statistical analysis

The study use the latent growth model (LGM) and the random intercept cross-lagged model (RI-CLPM) for longitudinal analysis. The LGM and the RI-CLPM present significant advantages in longitudinal research. The LGM is particularly effective in capturing individual changes over time and in revealing the long-term developmental trends associated with environmental factors and health outcomes. Meanwhile, the RI-CLPM incorporates random intercepts to account for stable individual differences, thereby effectively distinguishing between individual-level effects and within-person effects. This approach enables researchers to accurately identify the dynamic relationships across different time points and to clarify the influence between independent and dependent variables (Hamaker et al. 2015).

This study first employed LGM to analyze depression among rural older adult and the corresponding PM2.5 levels in the respective counties measured in T1(2014), T2(2016), and T3(2018). In this model, the intercept represented the initial level, while the slope indicated change, enabling us to examine the developmental trajectory of PM2.5 and depression among rural older adults, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

Secondly, the study constructed a RI-CLPM of PM2.5 pollution on the depression of rural older adults, the following expressions are employed (Formula 1):

In these equations, Xit, Yit represent the observed values of PM2.5 for county i and the depression among rural older adults j at time t (where t = 1,2,3). The parameters μxt,μyt denote the group means of PM2.5 and depression, respectively, at time t. The terms Ixi,Iyi correspond to the stable characteristic factors for each county and older adults, which vary across individuals. All loadings of the characteristic factors are fixed at 1, functioning as random intercepts. The terms \({{{X}_{it}^{\ast}\quad{Y}_{ji}^{\ast}}}\) signify the specific deviations for PM2.5 and depression for county i and individual j at time t, indicating the temporal variability of each subject concerning these variables.

Subsequent to the separation of group means and stable characteristic factors, the RI-CLPM employs the time-specific deviations \({{({X}_{it}^{\ast}\quad{Y}_{\,i}^{\ast})}}\) to construct a cross-lagged model, expressed as follows (Formula 2):

In this model, βxt and βyt represent the autoregressive coefficients, while γxt and γyt denote the cross-lagged coefficients. The terms dxit and dyjt are the regression residuals. This cross-lagged structure typically incorporates both autoregressive paths and cross-lagged paths, enabling a comprehensive analysis of the dynamic relationships between the variables over time.

This study utilized SPSS 22.0 and Mplus 8.3 for data analysis. All models were estimated using the full information maximum likelihood method (Muthen and Muthen, 2012). To enhance model simplicity, stability and cross-lagged paths were constrained to be equal across all models. In accordance with recommendations by Hu and Bentler (1999), several model fit evaluation indices and their respective standards were utilized in this study. Firstly, the chi-square statistic divided by the degrees of freedom (χ2/df) was employed, with smaller values indicating better fit. This ratio reflects the divergence between the hypothesized relationships among the variables and the actual relationships captured in the data. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that χ2/df can be influenced by sample size; therefore, it should be interpreted alongside other fit indices. Secondly, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) was calculated, which represents the average residual sum of squares between predicted and actual values, normalized by the square root of the sample size. A smaller RMSEA value indicates better model fit, with values less than 0.08 generally considered indicative of good fit. Additionally, the comparative fit index (CFI) and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) were utilized to quantify model fit by comparing discrepancies between predicted and observed values. These indices range from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 signifying a better fit. Typically, a CFI greater than 0.90 and a TLI exceeding 0.90 suggest a satisfactory model fit. The study employed multi-group analysis methods to test the moderating role of income level in this relationship. Finally, the study uses the maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors to estimate the parameters, increase the control variables, and bootstrap nonparametric estimation to test the robustness of the model’s statistical results.

Measurement invariance test

This study analyzed the invariance of the latent variable of depression among rural older adults over a four-year period, utilizing three measurement points, as illustrated in Table 1. The findings indicate that the configural invariance model (M1), weak invariance model (M2), and strong invariance model (M3) all exhibited good fit. Furthermore, comparative analyses revealed no statistically significant differences between M1 and M2, indicating successful weak invariance testing. This outcome demonstrates that the factor loadings for the depression measurement variables remained consistent across different time points, suggesting a stable understanding of the construct of depression throughout the three surveys. Similarly, no statistically significant differences were noted between M2 and M3, implying that the parameters and measurement quality for rural older adults were relatively stable across different time points. Consequently, this study concludes that the depression among rural older adults met the requirements for both weak and strong measurement invariance across the three evaluations.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The means and standard deviations (SD) of PM2.5 levels and depression among rural older adults from three measurements in 2014–2018 are presented in Table 2. Over the period from T1 to T3, the PM2.5 concentration gradually decreased, with the average value decreasing from 49.058 µg/m³ to 35.942 µg/m³. Additionally, this study revealed that the difference in average PM2.5 levels in counties is statistically significant, where rural older adults with different incomes resided at different time points. More specifically, this study found that older adults in rural areas with higher income levels had higher PM2.5 levels. Notably, in 2014, the average PM2.5 concentration in regions inhabited by the high-income group was particularly high, reaching 52.677 µg/m³. Over the duration from T1 to T3, the severity of depression among rural older adults progressively increased. In 2014, a statistically significant difference was observed between the various income groups, with low-income rural older adults exhibiting significantly higher levels of depression compared to their medium-income and high-income counterparts. This suggests that lower income is associated with more severe depressive symptoms.

In this study, covariate analyses reveal that the gender ratio within the overall sample was approximately 1:1 (calculation formula: male/female), though significant variations were observed across different income groups. The proportion of women was notably higher in the low-income group, and as income levels increased, the proportion of women gradually declined, with only 29.2% of the high-income group being female older adults. Regarding age, the overall sample exhibited an average age of nearly 70 years, yet significant disparities were noted among different income groups. Specifically, as income levels increased, the average age tended to decrease, with the average age of the low-income group approximating 72 years, while that of the high-income group was around 67 years. In terms of education, the overall average educational level in the sample was 2.290, indicating a generally low level of education among rural older adults, which falls below the threshold of primary school graduation. Additionally, the study found that lower income levels among rural older adults were associated with lower levels of educational attainment. With respect to cohabitation, the overall sample reported an average of 2.744 cohabitants, close to three individuals, with statistically significant differences evident among various income groups. Notably, middle-income older adults reported the fewest cohabitants. Concerning chronic diseases, the sample exhibited a chronic illness score of 0.791, suggesting that a considerable proportion of the elderly population experiences poor health. The study further identified that rural older adults with lower income are associated with a higher probability of chronic diseases. In terms of social participation, the overall engagement rate among rural older adults proved to be markedly low. The findings also indicated that younger elderly individuals were more likely to participate actively in social activities. Regarding social networks, the average social network score for rural older adults stood at 17.936. Among the various income groups, those in the medium-income possessed the most extensive social networks, while high-income individuals exhibited relatively weaker connectivity within their networks. Finally, an analysis of regional per capita GDP revealed noticeable variations among different income groups of rural older adults. As income levels decreased, so too did the per capita GDP of the regions in which these older adults resided.

Trajectories of PM2.5 and depression among rural older adults

PM2.5 pollution level

Table 3 presents the fit indices of the linear unconditional latent growth model for overall samples and different income samples of PM2.5 in the counties. The results indicate a strong model fit, indicating that the developmental trajectory of PM2.5 in regions with older adults, both overall and across different income levels, exhibited a linear growth path from 2014 to 2018.

Similarly, in the county from which the overall sample was drawn, the initial PM2.5 intercept was recorded at 49.181 µg/m³ (p < 0.001). PM2.5 pollution displayed a linear downward trend on an annual basis, with a slope of −6.438 (p < 0.001), indicating a reduction of 6.438 µg/m³ every two years. Further calculations revealed that the average annual decrease rate of PM2.5 is approximately 6.5%, as calculated by the formula: [(final value - initial value) / initial value]/number of years. The significant variability in both the intercept and slope underscores the statistically meaningful differences in the initial PM2.5 levels and developmental slopes across different counties. Additionally, a significant negative correlation between the slope and intercept was identified, suggesting that counties with lower initial levels of PM2.5 experienced slower rates of reduction, as illustrated in Fig. 3b.

The observed differences in the unconditional linear growth model of PM2.5 in regions with older adults of varying income levels are statistically significant, with both the intercept and slope showing significant values. As income levels decrease, the intercept of PM2.5 in these regions demonstrates a downward trend. Specifically, the intercepts for the low-income, middle-income, and high-income groups were found to be 47.116 µg/m³, 48.772 µg/m³, and 52.733 µg/m³ respectively (all P < 0.001). This indicates that regions with lower-income populations had relatively the lowest pollution levels in 2014. Likewise, the slopes of the unconditional linear growth model of PM2.5 for regions with older adults of differing income levels were −5.939, −6.252, and −7.240 respectively (all p < 0.001). This suggests that as the income level of the population decreases, the improvement in PM2.5 pollution levels within their residing areas occurs at a slower rate.

Depression among rural older adults

The linear unconditional latent growth model of the overall sample of rural older adults demonstrates a good fit, which indicates that the development trajectory of depression among rural older adults from 2014 to 2018 conforms to the linear growth trajectory. The statistical results of the model are detailed in Table 4 and Fig. 3a. The intercept indicates that the initial level of depression among rural older adults is 9.304 (p < 0.001), and the slope is 0.355 (p < 0.001), meaning that depression among rural older adults gradually worsened from 2014 to 2018, with a significant increase of 0.355 units every two years, and an average growth rate of 1.9%. In addition, the variances of the intercept and slope are both significant, and there is no significant correlation between the intercept and slope, as shown in Table 4.

The fitting degree of the linear unconditional latent growth model varies among different income groups of rural older adults. Specifically, the model fits well for the middle-income older adults group, but the fit of the models for the low-income and high-income older adults groups is not satisfactory. This shows that only the development trajectory of depression among the middle-aged older adults conforms to the linear growth trend, while the development trajectories for low-income and high-income individuals do not conform to a linear growth trend. For middle-income rural older adults, the intercept for depression is 9.575 (p < 0.001), with a slope of 0.212 (p < 0.001), and an average growth rate of 1.1%. In comparison, the intercept for depression in the low-income older adult group is 9.748, and that in the high-income older adult group is 8.611. Although the change in depression in the low-income and high-income groups does not conform to the linear growth trend, the differences between depression intercepts of different income groups are relatively considerable. Therefore, overall, the lower the income, the higher the intercept. For rural older adults, lower income implies a greater risk of mental health problems.

Random intercept cross-lagged model analysis of the impact of PM2.5 on depression among rural older adults

The statistical results of the overall rural older adult sample model

This study employed a random intercept cross-lagged regression analysis to investigate the indicative associations between PM2.5 and depression among overall rural older adults from 2014 to 2018 (Martens and Haase, 2006). The model incorporated several covariates—namely age, education, gender, cohabitation, chronic diseases, social participation, social network, and the county’s per capita GDP—to control for potential confounding factors. By constraining the autoregressive paths (AR Paths) and cross-lagged paths (CL Paths) to be equal, this research obtained a well-fitting model. This implies that the autoregressive relationship and lag effect of PM2.5 and depression among rural older adults are basically consistent during the T1 → T2 and T2 → T3 periods. Specific fit indices are provided in Table 5, while Fig. 4 illustrates the model diagram.

After extracting the individual-level effects, within the T1 → T2 → T3 time interval, this research observed that PM2.5 at T1 significantly positively predicted depression among rural older adults at T2 two years later, with a standardized coefficient of β = 0.089 (p < 0.001). This indicates that for each standard deviation increase in PM2.5 concentration at T1, depression among rural older adults at T2 increases by 0.089 standard deviations, suggesting that higher PM2.5 pollution at T1 will statistically lead to increased depression among rural older adults at T2. Similarly, PM2.5 levels at T2 positively predicted depression among rural older adults at T3, two years later, with a standardized coefficient of β = 0.073 (p < 0.001). This implies that for each standard deviation increase in PM2.5 concentration at T2, depression among rural older adults at T3 rises by 0.073 standard deviations, further indicating that higher PM2.5 pollution at T2 will statistically exacerbate depressive symptoms at T3. Overall, from 2014 to 2018, higher levels of PM2.5 exposure resulted in exacerbated depression among rural older adults, and this effect was statistically significant.

In the analysis of covariates, gender, education, and social networks did not have a statistically significant impact on depression among rural older adults at the lagged periods (T2 and T3). Age demonstrated a statistically significant impact on depression in the first lagged period, with a coefficient of 0.058 (p < 0.05). Additionally, social participation was found to have a statistically significant negative impact on depression during the second lagged period (T3), with a coefficient of −0.050 (p < 0.05). The number of cohabitants and per capita GDP consistently showed a significant negative impact on depression among rural older adults across the lagged periods: the coefficients for the first lagged period were −0.064 (p < 0.01) for cohabitants and −0.054 (p < 0.05) for per capita GDP; in the second lagged period, these coefficients were −0.065 (p < 0.01) and −0.129 (p < 0.001), respectively. Chronic illness has a sustained positive effect on depression among rural older adults, with coefficients of 0.081 (p < 0.001) for the lagged first period and 0.059 (p < 0.05) for the lagged second period. These findings suggest that chronic illnesses may exacerbate depressive symptoms among older adults. Conversely, increasing the number of cohabitants, raising income levels, and enhancing social participation may potentially improve their mental health. Detailed results are summarized in Table 6.

Comparison of groups of rural older adults with different incomes

The statistical results of the RI-CLPM group comparison of rural older adults with different income levels show that, after extracting individual-level effects, the previous period’s PM2.5 cannot significantly predict the depression among high-income rural older adults in the subsequent period during T1 → T2 and T2 → T3 (Supplement Fig. 1). This lagged effect is significant only for low and medium-income rural older adults. Specifically, PM2.5 measured at T1 significantly predicts depression in rural low-income older adults at T2, with a standardized effect coefficient of β = 0.117 (p < 0.01). Similarly, PM2.5 at T2 significantly predicts depression among rural low-income older adults at T3, with a standardized effect coefficient of β = 0.113 (p < 0.01). This suggests that higher PM2.5 levels may contribute to more severe depressive symptoms in this demographic. Figure 5 provides a visual representation of low-income model. Similarly, in the medium-income group, the lagged effect of PM2.5 on depression is also statistically significant. PM2.5 at T1 significantly predicts depression among rural medium-income older adults at T2 in a statistically meaningful way, with a standardized effect coefficient of β = 0.081 (p < 0.05). Furthermore, PM2.5 at T2 significantly predicts depression among this group at T3 in a statistically meaningful way, evidenced by a standardized effect coefficient of β = 0.072 (p < 0.05). Figure 6 presents the model diagram for the medium-income older adults. The results from the model group comparisons reveal statistically significant differences in the coefficients reflecting the impact of PM2.5 on depression among rural older adults at different income levels. Specifically, the impact of PM2.5 on depression is more pronounced in individuals with lower income levels.

In the analysis of the impact of covariates on depression among rural older adults at different income levels, both gender and age demonstrate a statistically significant positive impact on the depression of high-income seniors in the lagged second period, with coefficients of 0.133 and 0.113, respectively. Conversely, the number of cohabitants has a statistically significant negative impact on the depression of low-income seniors in the lagged second period, indicated by a coefficient of −0.125. Moreover, per capita GDP significantly impacts depression among low-, medium-, and high-income rural older adults in the lagged second period, exhibiting coefficients of −0.144, −0.146, and −0.144, respectively. Chronic illness also significantly impacts the depression of low- and middle-income seniors in the lagged second period, with coefficients of 0.093 and 0.083, respectively. Education level, social participation, and social networks do not demonstrate statistically significant impacts on depression among the entire older adult population. These findings are largely consistent with the overall sample while also revealing some notable group differences. Among the high-income group, older age is associated with higher levels of depression. Additionally, high-income female seniors exhibit greater depressive symptoms than their male counterparts. The influence of the number of cohabitants is significant only for low-income seniors, specifically indicating that a lower number of cohabitants is associated with elevated levels of depression. Detailed results are provided in Table 7.

Robustness analysis

To ensure the robustness of the research conclusions, the study implemented three robustness testing methods. The findings consistently indicate that the statistical results and conclusions of the model remain stable across all approaches, demonstrating substantial robustness:

-

(1)

MLR estimation method: The study utilized maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR) through Mplus software. This approach provides robust standard errors and chi-square statistics, significantly enhancing the precision and reliability of the model estimates. Importantly, after applying the MLR method, the primary findings and conclusions of the model exhibited no significant alterations, thereby reinforcing the validity of our research outcomes.

-

(2)

Reduction of control variables: The original model included a considerable number of control variables to account for potential confounders influencing depressive symptoms. For robustness checks, we streamlined the model by retaining only essential demographic variables, such as age, gender, education level, and the number of cohabitants. Results indicated that, even with this reduced set of control variables, the impact of PM2.5 on depressive symptoms remained statistically significant, with effect coefficients closely aligning with those observed in the original model. This consistency further suggests a high degree of robustness in our findings.

-

(3)

Bootstrap sampling method: The study implemented the Bootstrap sampling method, conducting 1000 replications to further evaluate robustness. Through extensive resampling, we obtained the distribution of model parameters, allowing for the calculation of standard errors and confidence intervals for these estimates. The results demonstrated that the estimates derived via the Bootstrap method were highly consistent with those from the original model, thereby further validating the reliability of our conclusions.

In summary, through the application of these three robustness testing methods, this study has conducted a thorough evaluation of the lagged effects of PM2.5 on depressive symptoms among rural older adults across varying income levels. Results from all testing methods unequivocally affirm the robustness and reliability of the model’s conclusions.

Discussion

The health hazards of pollution on both physical and mental health have attracted considerable scholarly attention across various countries and governmental bodies (Bao and Liu, 2022; Lu and Wen, 2016). There has been relatively little research on the impact of pollution on depression among rural older adults, and most of the existing studies have been based on cross-sectional research (Shi et al. 2020; Yao et al. 2022). Furthermore, longitudinal studies on the impact of pollution on the health of older adults in rural areas are particularly scarce. To fill this gap, this study used data from the CLASS to analyze the trajectory of changes in PM2.5 and depression among rural older adults from 2014 to 2018. The study used latent growth models and RI-CLPM to reveal the indicative associations of PM2.5 and depression among rural older adults. The RI-CLPM is regarded as a robust statistical tool for analyzing the interrelationships among variables, thereby enhancing the reliability and scientific validity of our research findings. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to utilize longitudinal data to investigate the indicative associations between air pollution and depression among rural older adults in China while also addressing health inequalities. This study found that the depression levels among rural older adults are becoming increasingly severe, with PM2.5 pollution identified as a significant factor contributing to this depression. Furthermore, the research revealed that the lower the income, the greater the detrimental impact of PM2.5 on the mental health of rural older adults. Low-income rural older adults represent the group most severely affected by depression and the group most impacted by PM2.5 pollution. This means that air pollution hazards have caused more serious health inequalities among elderly people with different incomes.

In terms of environmental conditions, PM2.5 pollution in China’s counties demonstrated a gradual improvement between 2014 and 2018, with an average annual reduction rate of 6.5%, indicating a positive trend. This decline in pollution levels can be attributed to the increased emphasis on environmental protection by the Chinese government during this period. Various environmental protection policies and initiatives have been implemented, including large-scale afforestation and grassland restoration projects aimed at mitigating land degradation (Song et al. 2022). These measures have contributed to reduced pollution levels, enhanced air and water quality, and the expansion of green spaces. Additionally, technological advancements have facilitated improved monitoring, assessment, and management of environmental conditions, enabling governmental and non-governmental organizations to more effectively address ecological challenges (Lu et al. 2020). However, it was observed that although initial PM2.5 concentrations were lower in regions populated by low-income older adults compared to those inhabited by their high-income counterparts, the rate of improvement in air quality among the low-income population was significantly slower. This discrepancy can be attributed to the comparatively less rigorous environmental governance in less developed regions, resulting in poorer outcomes regarding environmental improvements.

Depression among rural older adults has exhibited a concerning upward trend from 2014 to 2018, with the severity of depressive symptoms increasing by 1.9% annually. This finding underscores the urgent need for targeted intervention. In addition, China’s rural socioeconomic conditions are relatively poor, medical resources are insufficient, social isolation is increasing, the aging population is rapidly growing, and there is a lack of awareness of mental health (Hoeft et al. 2018). These interrelated factors collectively heighten the vulnerability of rural older adults to mental health disorders. The study also revealed that low-income rural older adults face a greater risk of depression. The low-income group may encounter elevated health inequalities, leading to more severe depression. In fact, this demographic is often considered among the most vulnerable in terms of health disparities (Wang et al. 2019; Ye et al. 2024). The mental health challenges faced by low-income rural older adults warrant special attention and cannot be overlooked.

Our study utilized the RI-CLPM to confirm the indicative associations of PM2.5 exposure and depression among rural older adults. An increase in PM2.5 leads to exacerbation of depression among rural older adults. Previous cross-sectional studies have also indicated the correlation between PM2.5 and depression among rural older adults (Zhang et al. 2020; Chen et al. 2021; Zheng et al. 2019). An important contribution of the study is to provide more scientific evidence regarding the relationship between these variables. The mechanisms through which PM2.5 exposure adversely impacts depression among rural older adults can be understood from multiple perspectives. Firstly, rural older adults exhibit heightened vulnerability to the neurotoxic effects of PM2.5, with exposure potentially leading to dysfunction in brain regions implicated in emotional regulation. This exposure may also increase the likelihood of inflammation and oxidative stress, compromising neuronal function and connectivity, which could precipitate depressive symptoms. Moreover, beyond its direct physiological effects, PM2.5 exposure may indirectly influence mental health by intensifying psychological stress and fatigue. Prolonged exposure compels rural older adults to continually confront the detrimental effects of pollutants, a situation further exacerbated by substandard sanitary conditions often present in rural settings. This chronic state of stress can elevate psychological strain and fatigue, thereby increasing the likelihood of developing mental health disorders, including depression. Additionally, the spatial dispersal common in rural areas may further exacerbate feelings of social isolation among older adults. High concentrations of PM2.5 can diminish outdoor activities, contributing to an increased risk of social isolation. Such isolation is closely linked to depression, particularly among rural older adults who heavily rely on social support networks (Jie et al. 2022; Henning-Smith et al. 2019).

The study provides compelling evidence of the associations between PM2.5 exposure and depression among rural older adults. This significant finding offers new insights for the development of environmental perception theory and serves as a scientific foundation for policymakers and public health experts to formulate targeted interventions aimed at improving the mental health of low-income rural older adults. Firstly, to effectively address these pressing concerns, policymakers should design air quality improvement initiatives specifically targeting low-income populations. It is essential to prioritize the environmental health challenges faced by low-income rural older adults while simultaneously providing financial subsidies to facilitate access to air purification devices that can mitigate the adverse effects of PM2.5. Furthermore, the implementation of environmental education and outreach programs is crucial, as these initiatives can enhance environmental awareness among rural older adults. Additionally, public health practitioners should actively engage in mental health screening and intervention efforts, particularly within rural communities, to ensure that low-income older adults have access to essential psychological counseling and support. Establishing community support networks and providing health education, alongside protective measures, can empower these individuals to better manage the health challenges associated with air pollution. Lastly, fostering interdepartmental collaboration to conduct research and gather data focused on low-income elderly populations will create a robust foundation for future policy development and service delivery. By enacting these comprehensive measures, it is possible to significantly enhance the quality of life and mental health of low-income rural elderly individuals, thereby alleviating the detrimental impacts of PM2.5 on their overall well-being.

More importantly, this research found that the impact of PM2.5 on depression is more pronounced among rural older adults with lower incomes. This research did not find evidence that pollution significantly harms the mental health of high-income rural older adults. This indicative association only exists within middle- and low-income rural older adults. Several factors may contribute to this disparity. First, low-income individuals generally possess limited socioeconomic resources to mitigate the effects of environmental pollution, including access to improved living conditions and air purification equipment. This lack of resources heightens their vulnerability to the adverse effects of PM2.5, potentially resulting in more severe depressive symptoms. Additionally, low-income rural older adults may experience heightened psychological stress due to economic and social pressures, with PM2.5 pollution exacerbating their psychological burden and increasing the risk of depression. In contrast, high-income rural older adults are likely to have greater resources to cope with these pressures, including access to a higher quality of life and medical resources, which may buffer the impact of pollution on their mental health (Park and Seo, 2021; Lei et al. 2022; Pan et al. 2021; Xu et al. 2016).

The findings of our research highlight the presence of social health inequalities, particularly regarding the impact of PM2.5 pollution on the mental health of rural older adults. Our analysis indicates that lower income levels among this demographic correlate with more pronounced mental health deterioration due to pollution exposure. This observation underscores the differential burdens that individuals from varying socioeconomic backgrounds face when confronted with environmental risks. Such conclusions are significant and warrant increased attention to this vulnerable population. Low-income rural older adults exhibit heightened susceptibility to the detrimental effects of PM2.5 pollution, a vulnerability exacerbated by their limited socioeconomic resources and elevated psychological stress. It is imperative for policymakers to recognize the specific needs of low-income groups and implement measures aimed at mitigating the environmental health risks they encounter.

However, it is essential to acknowledge the limitations of our study. Firstly, while the survey data used in this study were collected through three rounds of tracking surveys, which revealed the indicative associations between pollution and depression among rural older adults, the number of tracking times were relatively small. Second, the PM2.5 data utilized in this study were derived from county-level comparisons of older adult samples, representing macro-level environmental indicators. Future research should aim to acquire PM2.5 data at the village level to yield more localized and precise conclusions. Finally, this study focused on PM2.5 as the measure of pollution, which encompasses various pollution types. Future investigations could benefit from examining multiple pollution sources to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of their effects.

Conclusion

The study observed a significant worsening of depression among older adults in rural China from 2014 to 2018, particularly among low-income individuals who faced more severe challenges related to depression. The study also identified indicative associations between PM2.5 exposure and depression among rural older adults. However, this association appears to be evident primarily among middle- and low-income groups, whereas no significant association was found among high-income rural older adults. Specifically, low-income rural older adults not only exhibited the highest levels of depression but also faced the greatest hazard associated with PM2.5 pollution. Our findings indicate that enhancing pollution control measures and improving environmental quality could effectively alleviate depressive symptoms among this demographic. Consequently, it is crucial to prioritize attention and resources toward low-income rural older adults, ensuring that investments in environmental pollution control are directed toward underserved populations and regions. By concentrating efforts on these vulnerable groups, this research aims to enhance the mental health of low-income rural older adults, thereby promoting health equity and social justice.

References

Ali MA, Huang Z, Bilal M, Assiri ME, Mhawish A, Nichol JE et al. (2023) Long-term PM2. 5 pollution over China: Identification of PM2. 5 pollution hotspots and source contributions. Sci Total Environ 893:164871. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.164871

Aunan K, Hansen MH, Liu Z et al. (2019) The hidden hazard of household air pollution in rural China. Environ Sci Policy 93:27–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2018.12.004

Bao R, Liu T (2022) How does government attention matter in air pollution control? Evidence from government annual reports. Resour Conserv Recycl 185:106435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2022.106435

Bao ZJ, Fan YM, Cui YF et al. (2017) Effect of PM2.5 mediated oxidative stress on the innate immune cellular response of Der p1 treated human bronchial epithelial cells. Eur Rev Med Pharm Sci 21(12):2907–2912. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28682426

Cai J, Coyte PC, Zhao H (2017) Decomposing the causes of socioeconomic-related health inequality among urban and rural populations in China: a new decomposition approach. Int J Equity Health 16:128. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-017-0624-9

Cao Z, Zhou J, Li M et al. (2023) Urbanites’ mental health undermined by air pollution. Nat Sustain 6:470–478. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-01032-1

Carmichael V, Adamson G, Sitter KC et al. (2019) Media coverage of mental illness: a comparison of citizen journalism vs. professional journalism portrayals. J Ment Heal 28(5):520–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2018.1466050

Chan CK, Yao X (2008) Air pollution in mega cities in China. Atmos Environ 42:1–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.09.003

Chancel L et al. (eds) (2022) World inequality report 2022. Harvard University Press

Chen B, Ma W, Pan Y et al. (2021) PM2.5 exposure and anxiety in China: evidence from the prefectures. BMC Public Health 21:429. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10471-y

Chen X, Giles J, Yao Y et al. (2022) The path to healthy ageing in China: a Peking University–Lancet Commission. Lancet 400(10367):1967–2006. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01546-X

Clayton S, Devine-Wright P, Swim J et al. (2016) Expanding the role for psychology in addressing environmental challenges. Am Psychol 71(3):199. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039482

Cong Z, Silverstein M (2008) Intergenerational time-for-money exchanges in rural China: Does reciprocity reduce depressive symptoms of older grandparents? Res Hum Dev 5:6–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427600701853749

David L, Hare, Samia R, Toukhsati, Peter J, Tiny J (2014) Depression and cardiovascular disease: a clinical review. Eur Heart J 35:1365–1372. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht462

Fan SJ, Heinrich J, Bloom MS et al. (2020) Ambient air pollution and depression: a systematic review with meta-analysis up to 2019. Sci Total Environ 701:134721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.134721

Gu X, Liu Q, Deng F, Wang X, Lin H, Guo X, Wu S (2019) Association between particulate matter air pollution and risk of depression and suicide: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 215(2):456–467. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.295

Guan WJ, Zheng XY, Chung KF et al. (2016) Impact of air pollution on the burden of chronic respiratory diseases in China: time for urgent action. Lancet 388:1939–1951. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31597-5

Hamaker EL, Kuiper RM, Grasman R (2015) A critique of the cross-lagged panel model. Psychol Methods 20:102–116. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038889

Hautekiet P, Saenen ND, Demarest S et al. (2022) Air pollution in association with mental and self-rated health and the mediating effect of physical activity. Environ Health 21:29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12940-022-00839-x

Henning-Smith C, Moscovice I, Kozhimannil K (2019) Differences in social isolation and its relationship to health by rurality. J Rural Health 35:540–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12344

Hou J, Zhou W, Jiang Y (2022) Multidimensional energy poverty and depression among China’s older adults. Front Public Health 10:977958. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.977958

Hoeft TJ, Fortney JC, Patel V, Unützer J (2018) Task‐sharing approaches to improve mental health care in rural and other low‐resource settings: a systematic review. J Rural Health 34(1):48–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12229

Hu L, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling 6(1):1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Jie L, Chen Y, Shi JY et al. (2022) Social isolation transitions and psychological distress among older adults in rural China: A longitudinal study before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord 308:337–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.04.045

Jun L, Hao Y, Xiao T, Tong Z, Qiang Z (2021) Transition in air pollution, disease burden and health cost in China: A comparative study of long-term and short-term exposure. Environ Pollut 277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.116770

Lei S, Guo LY, Deng HZ (2022) The mechanisms underlying the negative effect of depression on life satisfaction among the elderly: The roles of ostracism and economic income. Int Psychogeriatr 34:715–724. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610221001162

Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, Allen NB (1997) Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol aging 12(2):277

Liang R, Zhang B, Zhao X et al. (2014) Effect of exposure to PM2. 5 on blood pressure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens 32(11):2130–2141. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000000342

Liu L (2019) Rural–urban inequities in deaths and cancer mortality amid rapid economic and environmental changes in China. Int J Public Health 64:39–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-018-1109-3

Liu T, Meng H, Yu M, Xiao Y et al. (2021) Urban-rural disparity of the short-term association of PM2. 5 with mortality and its attributable burden. The Innovation, 2(4). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100171

Lu F, Wen JL (2016) Legislation, plans, and policies for prevention and control of air pollution in China: achievements, challenges, and improvements. J Clean Prod 112:1549–1558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.08.013

Lu X, Zhang S, Xing J et al. (2020) Progress of air pollution control in China and its challenges and opportunities in the ecological civilization era. Engineering 6(12):1423–1431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eng.2020.03.014

Martens MP, Haase RF (2006) Advanced Applications of Structural Equation Modeling in Counseling Psychology Research. Couns Psychol 34(6):878–911. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000005283395

Muthen LK, Muthen BO (2012) Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthen & Muthen

Pan G, Li S, Geng Z, Zhan K (2021) Do Social Pension Schemes Promote the Mental Health of Rural Middle-Aged and Old Residents? Evidence From China. Front Public Health 9:710128. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.710128

Park GR, Seo BK (2021) Mental Health Among the Korean Older Population: How is it Related to Asset-based Welfare? J Appl Gerontol 40(2):142–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464820917295

Pun VC, Manjourides J, Suh H (2017) Association of ambient air pollution with depressive and anxiety symptoms in older adults: results from the NSHAP study. Environ Health Perspect 125(3):342–348. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP494

Sabeti Z, Ansarin K, Seyedrezazadeh E et al. (2021) Acute responses of airway oxidative stress, inflammation, and hemodynamic markers to ambient PM2. 5 and their trace metal contents among healthy adolescences: A panel study in highly polluted versus low polluted regions. Environ Pollut 288:117797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117797

Sabo S, De Zapien J, Teufel-Shone N et al. (2015) Service learning: A vehicle for building health equity and eliminating health disparities. Am J Public Health 105(S1):S38–S43. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302364

Shi W, Li T, Zhang Y et al. (2020) Depression and Anxiety Associated with Exposure to Fine Particulate Matter Constituents: A Cross-Sectional Study in North China. Environ Sci Technol 54(24):16006–16016. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.0c05331

Song W, Feng Y, Wang Z (2022) Ecological restoration programs dominate vegetation greening in China. Sci Total Environ 848:157729. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.157729

Tam KP, Chan HW (2017) Environmental concern has a weaker association with pro-environmental behavior in some societies than others: A cross-cultural psychology perspective. J Environ Psychol 53:213–223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.09.001

Tian T, Chen Y, Zhu J, Liu P (2015) Effect of Air Pollution and Rural-Urban Difference on Mental Health of the Elderly in China. Iran J Public Health 44(8):1084–1094. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.d01-231.x

Tilt B (2013) The politics of industrial pollution in rural China. J Peasant Stud 40(6):1147–1164. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2013.860134

Van Donkelaar A, Hammer MS, Bindle L, Brauer M et al. (2021) Monthly global estimates of fine particulate matter and their uncertainty. Environ Sci Technol 55:15287–15300. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.1c05309

Vilagut G, Forero CG, Barbaglia G, Alonso J (2016) Screening for depression in the general population with the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D): a systematic review with meta-analysis. PloS one 11(5):e0155431

Wang R, Yang B, Liu P et al. (2020) The longitudinal relationship between exposure to air pollution and depression in older adults. Int J Geriatr Psychiatr 35:610–616. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5277

Wang R, Liu Y, Xue D, Yao Y, Liu P, Helbich M (2019) Cross-sectional associations between long-term exposure to particulate matter and depression in China: The mediating effects of sunlight, physical activity, and neighborly reciprocity. J Affect Disord 249:8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.02.007

Wang X, Shao S, Li L (2019) Agricultural inputs, urbanization, and urban-rural income disparity: Evidence from China. China Econ Rev 55:67–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2019.03.009

Wickstead P, Furnham A (2017) Comparing mental health literacy and physical health literacy: an exploratory study. J Ment Health 26:449–456. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1294743

World Health Organization(WHO) (2017) Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/depression-global-health-estimates. Accessed 3 Jan 2017

World Health Organization(WHO) (2021) Health topics: Air pollution. https://www.who.int/health-topics/air-pollution. Accessed 18 Mar 2024

Xing YF, Xu YH, Shi MH et al. (2016) The impact of PM2. 5 on the human respiratory system. J Thorac Dis 8(1):E69. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2016.01.19

Xu Y, Yang J, Gao J et al. (2016) Decomposing socioeconomic inequalities in depressive symptoms among the elderly in China. BMC Public Health 16(1):1214. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3876-1

Xue T, Guan T, Zheng Y, Geng G, Zhang Q, Yao Y et al. (2021) Long-term PM2. 5 exposure and depressive symptoms in China: a quasi-experimental study. Lancet Reg Health-W Pac 6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2020.100079

Xue W, Hine DW, Loi NM et al. (2014) Cultural worldviews and environmental risk perceptions: A meta-analysis. J Environ Psychol 40:249–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.07.002

Yao M, Wu G, Zhao X et al. (2020) Estimating health burden and economic loss attributable to short-term exposure to multiple air pollutants in China. Environ Res 183:109184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2020.109184

Yao Y, Lu T, Liu Y et al. (2022) Association of depressive symptoms with ambient PM(2.5) in middle-aged and elderly Chinese adults: A cross-sectional study from the China health and retirement longitudinal study wave 4. Environ Res 203:111889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2021.111889

Yang L, Li C, Tang X (2020) The Impact of PM2.5 on the Host Defense of Respiratory System. Front Cell Dev Biol 8:91. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2020.00091

Ye Z, Li X, Lang H et al. (2024) Income inequality and depressive symptoms among Chinese adults: a quasi-experimental study. Public Health 226:58–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2023.10.042

Yun X, Shen G, Shen H et al. (2020) Residential solid fuel emissions contribute significantly to air pollution and associated health impacts in China. Sci Adv 6:44. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aba7621

Zeng J, Jiang M, Yuan M (2020) Environmental Risk Perception, Risk Culture, and Pro-Environmental Behavior. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(5):1750. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051750

Zhang B, Wu B, Liu J (2020) PM2.5 pollution-related health effects and willingness to pay for improved air quality: evidence from China’s prefecture-level cities. J Clean Prod 273:122876. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122876

Zhao S, Liu S, Hou X et al. (2021) Air pollution and cause-specific mortality: A comparative study of urban and rural areas in China. Chemosphere 262:127884. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127884

Zheng S, Wang J, Sun C et al. (2019) Air pollution lowers Chinese urbanites’ expressed happiness on social media. Nat Hum Behav 3:237–243. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0521-2

Zijlema W, Wolf K, Emeny R et al. (2016) The association of air pollution and depressed mood in 70,928 individuals from four European cohorts. Int J Hyg Environ Health 219:212–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2015.11.006

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Social Science Fund of China (21BRK020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: ZZ and LC; Data curation: ZZ.; Formal analysis, ZZ, LC, NS; Methodology: ZZ and LC; Validation: ZZ and YJ; Software: ZZ and YW; Resources: ZZ; Writing—original draft preparation: ZZ and LC.; writing—review and editing: ZZ, LC and YJ; Visualization: ZZ and LC; Supervision: YW; Project administration: NS; Funding acquisition: ZZ.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The data utilized in this study is derived from the “China Longitudinal Ageing Social Survey” (CLASS), conducted by Renmin University of China. The CLASS survey is a sociological research project and does not fall within the realm of medical research. It adheres to the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and does not involve human experimentation as defined by that Declaration. Furthermore, the questionnaire is specifically designed to avoid any adverse effects on the mental health of the respondents. Consequently, the CLASS survey does not require additional ethical approval. All participants provided written informed consent, and the information collected is intended exclusively for sociological research purposes, with strict measures in place to ensure confidentiality and anonymity.

Informed consent

The interviewer recorded more detailed information regarding the informed consent process, including whether participants agreed to take part in the study and the timing of their consent. The details of the informed consent process are maintained by the Institute of Gerontology at Renmin University of China and the National Survey Research Center.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, Z., Chen, L., Sun, N. et al. Pollution, hazards, and health inequalities: a longitudinal exploration of the impact of PM2.5 on depression among rural older adults with different incomes in China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1682 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04233-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04233-5

This article is cited by

-

PM2.5 risk perception and associated with sociodemographic factors in urban Thailand

Scientific Reports (2025)

-

The Influence of Air Pollution on Older Migrants’ Intentions To Settle in the Destination Cities in China

Applied Spatial Analysis and Policy (2025)