Abstract

It is widely acknowledged that motivational beliefs significantly influence writing performance. This study explores the relationship between writing motivation and writing performance among Chinese primary school students, particularly examining the effect of writing self-efficacy on this relationship. A total of 307 fourth-grade students from Chinese primary schools were surveyed using the adapted writing motivation questionnaire and the writing self-efficacy questionnaire, along with a narrative writing task. Descriptive analyses show that students had moderate to high levels of motivation and self-efficacy for writing. This research delineates the pathways through which motivation modulates self-efficacy in writing, subsequently informing writing performance. Specifically, intrinsic motivation significantly enhances self-efficacy for ideation, conventions, and self-regulation. In contrast, extrinsic motivation has no effect on any aspect of self-efficacy. Furthermore, self-efficacy for self-regulation emerges as a salient predictor of writing performance. The study also elucidates that intrinsic motivation indirectly influences writing performance through self-efficacy for self-regulation. This study provides new perspectives into primary school students’ motivational beliefs and writing performance in Chinese. It highlights the critical role of self-regulation in the effect of motivation, especially intrinsic motivation, on writing performance. The educational implications of these findings for improving writing instruction are also briefly discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With student initiative in the learning process acknowledged, an increasing cohort of scholars has recognised the important impact of motivational beliefs on writing (Camacho et al. 2021; Sabti et al. 2019; Zhu et al. 2023). This line of inquiry underscores that successful writing involves not only the use of cognitive-linguistic skills but also motivational beliefs, which are essential to a writer’s capacity to articulate ideas successfully (Bruning et al. 2013; Graham et al. 2012; Guan et al. 2024). Specifically, writing motivation—the driving force behind students’ reasons for writing—significantly influences their engagement in the writing process (Graham 2018). This concept is elaborated upon by the Writer(s)-Within-Community (WWC) model introduced by Graham (2018), which posits that an individual’s writing is not an isolated act but is shaped by the broader writing community. This model underscores the integrative role of motivation in personal growth within the sociocultural context. Self-efficacy, another central concept, refers to an individual’s belief in their capabilities to perform a specific task (Bandura 1986). In the context of writing, self-efficacy is paramount, as it directly influences students’ writing performance and learning engagement (Pajares et al. 2007). It is the confidence that fuels the persistence and effort required to articulate ideas effectively.

In China, learning to write plays a significant role in the basic education curriculum. The Chinese Language Curriculum Guidelines for Compulsory Education (2022 Edition) includes stimulating students’ intrinsic motivation as a propositional requirement for writing. The teaching of writing for fourth-grade students focuses on guiding students to write for the purposes of self-expression and communication with others, with a particular emphasis on students’ personal experiences and insights (Ministry of Education of China 2022). Therefore, the stimulation of students’ motivation and the cultivation of self-efficacy to improve their language writing ability are two important goals of compulsory education in China.

The relationship between writing motivation, writing self-efficacy, and students’ writing performance is a vital topic in writing research (Chea and Shumow 2017; Pajares 2003). However, the existing research mainly focuses on the effects of writing motivation or self-efficacy on students’ writing achievement, respectively, or explores the path between writing motivation and self-efficacy individually (Ng et al. 2021; Ng et al. 2022; Yeung et al. 2020). Very few studies have examined these variables concurrently, particularly in the field of Chinese writing research. Moreover, most of the existing literature investigates writing motivation and self-efficacy with samples of Western or Caucasian students (Camping et al. 2020; Rasteiro and Limpo 2023; Rocha et al. 2019), and few studies have investigated other ethnic groups. The uniqueness of educational settings may influence the research findings concerning students’ motivational beliefs and academic performance. Therefore, there is an urgent need to extend existing research to different contexts and populations.

Contextualised in primary education in China, the current study investigated the impact of writing motivation and self-efficacy on fourth-grade students’ writing performance. The study is significant for its theoretical contribution to the under-researched area of Chinese primary school students’ writing motivational beliefs and its practical implications for language education. Practically, the results provide valuable insights into how teaching strategies could be adapted to boost young students’ motivation and self-efficacy in writing and, consequently, improve their writing performance.

Literature review

A multi-dimensional perspective of writing motivation

Students develop a range of dispositions, beliefs, and goals in a variety of tasks and situations related to writing, which establish the basis of their motivation to write (Boscolo and Gelati 2019). The current study is anchored in the WWC model, which is influenced by self-determination theory (SDT) and reflects the complex and diverse characteristics of writing motivation (Camping et al. 2020). According to the model, writing motivation (i.e., intrinsic motivation and extrinsic motivation) is defined as the driving forces that justify the reasons behind students’ engagement in writing activities (Graham 2018). Intrinsic motivation refers to the personal satisfaction and enjoyment derived from the writing itself, while extrinsic motivation is motivated by the desire to obtain an external result, such as grades or praise (Graham et al. 2022). Writing motivation assumes a pivotal role in the WWC model, as it is the antecedent and consequence of other writing beliefs, such as writing preference, attributions of success, and identity as a writer, identified within the model (Graham et al. 2021; Camping et al. 2020). Specifically, the strength of intrinsic motivation is influenced by beliefs about competence (e.g., “I can write on the topic well.”), preference (e.g., “Writing is important to me and I like writing.”), and identity (e.g., “Being a good writer is important to me.”). The strength of extrinsic motivation is influenced by beliefs about success (e.g., “I will receive good grades or praise if I write well.”) and communities (e.g., “My parents wanted me to get good writing grades.”). These two kinds of motivation have a substantial impact on the learning of writing. Intrinsic motivation may increase the frequency of writing, and extrinsic motivation may encourage students to undertake more challenging writing tasks (Camping et al. 2020; Graham et al. 2021; Schiefele and Schaffner 2016).

A number of studies have demonstrated that the relationship between students’ writing motivation and writing performance can vary across cultures. Unlike Western students, who have intrinsic and extrinsic motivation at opposite ends of the spectrum (Rocha et al. 2019), Chinese students’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivation are closely and positively correlated (Yeung et al. 2020). Some scholars posit that China’s collectivist and pragmatic cultural values, along with the prevalence of exam-focused educational settings, contribute to heightened extrinsic motivation for writing learning, such as competition and achievement (Ng et al. 2021; Ng et al. 2022; Yeung et al. 2020). With fourth-grade children in Shanghai, Ng et al. (2022) revealed that achievement served as the fundamental motivation for engaging in writing tasks. However, the newly introduced policy aims to reduce the pressure on primary school students while addressing the one-sided pursuit of high scores (Ministry of Education of China 2022). Therefore, it is worth exploring whether the motivation of Chinese primary school students has shifted from extrinsic motivation to intrinsic motivation driven in the new context.

Recently, Graham et al. (2022) developed the Writing Motivation Questionnaire (WMQ), which categorises motivation for writing into intrinsic and extrinsic motivation, with a total of 28 items. Intrinsic motivation is further divided into curiosity (writing driven by a desire to explore fascinating topics), involvement (writing driven by the enjoyment derived from the writing process), emotional regulation (writing to alleviate negative feelings), and boredom relief (writing to reduce a sense of boredom). Extrinsic motivation consists of grades (writing to enhance academic performance), competition (writing to surpass others in terms of performance), and social recognition (writing to earn acclaim and admiration from others) (Graham et al. 2022). The WMQ was chosen for this study because of its extensive utilization recently which offers a more fine-grained analysis of motivation to write than other questionnaires (Limpo et al. 2020). Several studies have already used the WMQ for empirical investigations and have established the validity of the multiple constructs of writing motivation among student populations in Western society (Camping et al. 2020; Limpo et al. 2020; Rasteiro and Limpo 2023; Rocha et al. 2019). However, WMQ has not been sufficiently used in China. Since different cultural and educational backgrounds may affect students’ motivation to write, more research is needed to verify the applicability of the WMQ in China and the authenticity of multidimensional writing motivation in Chinese students.

Writing self-efficacy and its associations with writing motivation and writing performance

Writing self-efficacy refers to the extent of confidence a student has in their capacity to successfully complete various specific writing tasks (e.g., narrative, informational) (Hidi and Boscolo 2006; Pajares 2003). Various scales have been developed and implemented across diverse contexts and demographics to assess writing self-efficacy. Among these, the Self-Efficacy in Writing Scale (SEWS), proposed by Bruning et al. (2013), stands out as one of the most widely used instruments. In their validation study with middle and high school students in America, Bruning and colleagues found that the SEWS exhibited strong alignment with collected data and demonstrated notable internal consistency. The SEWS is structured around a three-factor model, encompassing writing self-efficacy for ideation, conventions, and self-regulation. Ideation refers to a writer’s belief in generating and organizing ideas. Conventions involve adhering to writing norms, including spelling and grammar. Self-regulation extends beyond writing tasks to managing emotions during the process (De Smedt et al. 2023; Zumbrunn et al. 2020). In this study, the three-factor model of writing self-efficacy proposed by Bruning et al. (2013) is utilised for two main rationales. First, it was suggested that employing a multidimensional framework could provide a more detailed and nuanced comprehension of self-efficacy in writing (Rasteiro and Limpo 2023). Second, more research is needed to explore the relationship between different self-efficacy domains and writing performance from a multidimensional perspective (Rasteiro and Limpo 2023; Zumbrunn et al. 2020).

Bandura (1989) contends that cognitive processes are the primary source of human motivation. As a result of introducing the concept of self-efficacy into the discourse, researchers have delved into its association with motivation (Pajares 2003). Intrinsically motivated students find learning enjoyable and feel confident in their ability to complete tasks, which positively contributes to self-efficacy (Alemayehu and Chen 2023; Hong et al. 2017). Similarly, Alemayehu and Chen (2023) suggest that students who are extrinsically motivated by rewards or incentives also tend to exhibit increased levels of self-efficacy. Building on the theoretical foundation of the influence of motivation on self-efficacy, some empirical studies have delved into the relationship between the two variables across various fields (Walker et al. 2006; Wu et al. 2020). These studies have consistently found a direct and positive correlation between students’ motivation and their learning self-efficacy. In the writing field, empirical studies with student samples from the United States (Pajares et al. 2006), Belgium (De Smedt et al. 2023), and Portugal (Limpo and Alves 2017) have indeed confirmed a correlation between motivation to write and self-efficacy. However, these studies have not explicitly examined the relationship between specific sub-dimensions of self-efficacy and those of writing motivation. In contrast, a study conducted by Ng et al. (2021) in a Chinese educational context provided more refined insights. Their research has shown that intrinsic (e.g., curiosity, boredom relief) and extrinsic motives (e.g., grades) positively affect primary students’ Chinese writing self-efficacy in generating ideas and basic skills. It affirms that intrinsic and extrinsic motivations are pivotal in shaping an individual’s self-efficacy and reinforcing students’ confidence and ability to succeed in language-related tasks in the Chinese educational context. Therefore, this paper posits that both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations are positively correlated with writing self-efficacy among Chinese primary school students, a hypothesis that merits further empirical validation.

In addition, while theoretically students with higher writing self-efficacy typically outperform students with lower self-efficacy (Bulut 2017; Chea and Shumow 2017; Usher and Pajares 2008), empirical studies report inconsistent findings regarding the relationship between an individual’s writing self-efficacy and the quality of their written performance. Moreover, there is a paucity of literature examining the relationship between self-efficacy and writing performance in the context of L1 Chinese education. Among the scant research, self-efficacy did not significantly predict writing performance in both the elementary level (Yeung et al. 2024) and tertiary-level educational settings (Xu et al. 2023; Yao et al. 2023). However, in a recent meta-analysis, Sun et al. (2021) observed that L1 writing self-efficacy indeed had a positive influence on students’ L1 writing performance, despite the relatively small effect size. Given the inconsistencies in the literature, further research should be directed to the nuanced role of self-efficacy in L1 writing within Chinese educational settings.

When self-efficacy is viewed as a three-dimensional construct that includes ideation, conventions, and self-regulation, the predictive value of different dimensions of writing self-efficacy for students’ writing performance also exhibits some inconsistency. For instance, De Smedt et al. (2016) identified that writing self-efficacy for ideation positively relates to writing performance. Meanwhile, a positive correlation between self-efficacy for conventions and students’ writing achievements was found in several studies (e.g., Rocha et al. 2019; Yilmaz Soylu et al. 2017; Zumbrunn et al. 2020). Furthermore, both Limpo and Alves (2017) and Camacho et al. (2021) discovered a positive connection between self-efficacy for self-regulation and students’ writing achievements. In conclusion, while the literature has documented the influence of writing self-efficacy on writing achievement, more nuanced explorations have revealed certain inconsistencies, possibly attributable to sample or methodological variations (Rasteiro and Limpo 2023). Therefore, additional investigations employing a multidimensional lens on self-efficacy are warranted to elucidate the association patterns between different dimensions of self-efficacy and writing performance.

Overview of the literature and the present study

Two major findings emerge after the review of the related literature. Firstly, while existing literature has established that both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations influence self-efficacy, there is a lack of research measuring students’ motivation from a comprehensive, multi-dimensional perspective (Ng et al. 2022). Moreover, research specifically addressing the impact of writing motivations on self-efficacy among Chinese primary students remains limited (e.g., Hong et al. 2017; Ng et al. 2021). Secondly, the relationship between self-efficacy and writing performance has been extensively discussed. However, findings regarding the relationships between the three sub-dimensions of writing self-efficacy (ideation, conventions, and self-regulation) and writing performance have been inconsistent (De Smedt et al. 2016; Limpo and Alves 2017; Rasteiro and Limpo 2023; Zumbrunn et al. 2020). Therefore, additional research is warranted to clarify these connections, especially involving participants from diverse cultural backgrounds to provide more empirical evidence to this line of inquiry. This study intends to address the following three research questions:

-

(1)

What are the relationships between writing motivation (intrinsic and extrinsic) and writing self-efficacy (for ideation, conventions, and self-regulation) among fourth-grade students in China?

-

(2)

What are the relationships between writing self-efficacy and writing performance?

-

(3)

To what extent can writing motivation indirectly influence writing performance through writing self-efficacy?

Research methodology

Participants

The participants included 307 fourth graders from one public elementary school in northern China. The school was situated in an urban setting, with most of its students coming from a middle socioeconomic background. The participants were aged between 9 and 11 years old (Mean age = 9.84, SD = 0.62, 56.68% male). All participants were native speakers of Putonghua Chinese. In addition, students at this school had a 40-minute weekly writing class beginning in third grade.

Instruments

Writing motivation questionnaire

The 28-item writing motivation questionnaire was developed based on the WMQ (Graham et al. 2022). The questionnaire encompassed seven motivational dimensions: four pertaining to intrinsic motivation—namely, curiosity, involvement, emotional regulation, and boredom relief—and three associated with extrinsic motivation, which includes grades, competition, and social recognition. Each section had four questions (Supplementary Appendix 1). All items were measured on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 signifies “strongly disagree” and 5 signifies “strongly agree”.

Writing self-efficacy questionnaire

The Writing Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (WSEQ) was adapted to measure students’ self-efficacy beliefs from three aspects: ideation, convention, and self-regulation. There were 16 items in total, 15 of which were derived from the 16-item scale developed by Bruning et al. (2013); one item was adopted by Yao et al. (2023) (Supplementary Appendix 2). As the participants were primary school students, revisions to the wording of these items were made based on suggestions from primary school teachers to ensure that all items were comprehensible to the participants. The items were measured on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Writing task and scoring rubrics

Students were requested to complete a narrative composition on the given topic, “Narrating a favourite place of yours,” in one hour. This genre was chosen for the following reasons. Firstly, narrative writing is the most extensively researched genre in writing studies and the most often used writing task (Troia et al. 2013). Secondly, narrative writing is the focus of the curriculum and assessment of writing for fourth-grade students (Ministry of Education of China 2022).

The rating rubrics proposed by Yeung et al. (2020) were chosen for this study due to their comprehensive coverage of key aspects of writing: content, vocabulary, sentence structure, and organization, which are critical in evaluating the quality of composition (Supplementary Appendix 3). Two teachers with extensive Chinese teaching and assessment experience scored the compositions. Students received scores ranging from 0 to 20. If there was a difference of more than two marks in the same paper, a third marker was introduced for assessment, and the final mark was calculated as the average of the two scores that were closest to each other (Lu et al. 2021). The intra-class correlation coefficient of the two teachers who scored the writing task was measured, and ICC = 0.89. As the ICC value is between 0.75 and 0.9, the reliability is good (Koo and Li 2016).

Data collection

The questionnaires and writing task were administered under the guidance of the classroom teachers. With informed consent received from both the schools and parents, a questionnaire was distributed to the students. The completion of the whole questionnaire took approximately 20 min. Throughout this procedure, classroom teachers provided a comprehensive explanation of the questionnaire’s objective and its components, aiming to ensure a thorough understanding of the questionnaire among the students. One week later, students were given an in-class Chinese writing examination, for which they were allotted one hour to complete the task.

Data analysis

Preliminary analyses were conducted using SPSS 26.0. Firstly, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was employed to test the questionnaires’ reliability. Then, a descriptive analysis of all research variables was conducted to understand the general levels of fourth-grade students’ writing motivation and writing self-efficacy. Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed to explore the bivariate correlation between the variables. AMOS 26.0 software was then employed to conduct confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test the construct validity of the writing motivation and self-efficacy questionnaires. Finally, structural equation modelling (SEM) was utilised to examine the relationships among the six variables. To enhance the precision and clarity of the structural model, we implemented item parcelling for writing motivation. Item parcelling entails the aggregation of multiple items into a unified indicator. This technique boasts several benefits, such as increased reliability, more distinct factor structures, and superior model fit compared to item-level solutions (Wilson and Trainin 2007).

We employed Mplus 8.3 (Muthén and Muthén 2017) for conducting path analysis due to its greater flexibility in managing indirect effects (Mallinckrodt et al. 2006). Since the effective sample in this study was 307 (n > 300), instead of using the Chi-square statistic (χ2) as the only indicator of model fit, indicators that exhibit reduced sensitivity to both model complexity and sample size were employed in order to assess model fit, including CMIN/df (good <3), the comparative fit index (CFI; acceptable >0.90), the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; acceptable <0.08), and standardised root mean square (SRMR; acceptable <0.08) (Kline 2023; Hair et al. 2010).

Results

Preliminary analysis

The descriptive statistics, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients, and bivariate correlations between all the study variables are shown in Table 1. The kurtosis of all variables was between +10 and −10, and the skewness was between +3 and −3, which means that the data can be regarded as normally distributed (Kline 2008). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients indicate that the questionnaires displayed an acceptable level of internal consistency (α > 0.70) (Kline 2013). Table 1 also presents a comprehensive overview of the bivariate correlations observed between key variables in this research. There were two notable findings. First, a significant positive correlation was observed among most pairs of motivational variables (0.132 < r < 0.756), except between involvement and emotion regulation. Second, writing scores exhibited correlations with all factors (0.142 < r < 0.288) except for emotional regulation, grades, and social recognition.

We then examined the construct validity of the WMQ and WSEQ. For the WMQ, the seven-factor model moderately fit the data: χ2 /df = 2.370, p < 0.01; CFI = 0.857; RMSEA = 0.067; SRMR = 0.076). Due to the CFI being below 0.9, which does not meet the threshold for acceptable fit, we further examined the standardised factor loadings of each item. The factor loadings for items Q7 (involvement) and Q12 (emotion regulation) were found to be less than 0.5, which was below the recommended threshold and thus removed (Hair et al. 2010). Upon inspection, the Modification Indices (MI) suggested that we can add two correlations within the same factor between residuals e17 and e18 (grades: items Q17 and Q18), e27 and e28 (social recognition: items Q27 and Q28). The revised measurement model (26 items) showed an acceptable fit to the data: χ2 /df = 2.035, p < 0.01; CFI = 0.901; RMSEA = 0.058; SRMR = 0.060 (Fig. 1). All items had significant factor loadings (0.51–0.75) on their respective factors, p < 0.001 (Table 2). Regarding the factor correlations among the seven specific motivational constructs (curiosity, involvement, emotional regulation, boredom relief, grades, competition, and social recognition), all were positively correlated (0.12 < r < 1.03, p < 0.001).

For WSEQ, the CFA indicated that the three-factor model reached an acceptable fit to the data: χ2/df = 2.153, p < 0.01; CFI = 0.943; RMSEA = 0.061; SRMR = 0.042. The factor loadings of all items were significant and ranged from 0.56 to 0.79, p < 0.01. Based on the MI provided by AMOS, we added one correlation between the residuals of two items (writing self-efficacy for conventions: item Q34 and Q35). The revised model shows a good fit: χ2 /df = 1.866, p < 0.01; CFI = 0.958; RMSEA = 0.053; SRMR = 0.040 (Fig. 2). In terms of the factor correlation, writing self-efficacy for ideation was positively associated with writing self-efficacy for conventions (r = 0.72, p < 0.001) and writing self-efficacy for self-regulation (r = 0.77, p < 0.001). Writing self-efficacy for conventions was positively associated with writing self-efficacy for self-regulation (r = 0.75, p < 0.001). All items had significant factor loadings (0.55–0.82) on their respective factors, p < 0.001 (Table 3).

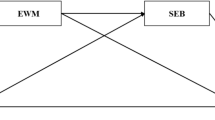

SEM results

The structural model (Fig. 3) was found to have an acceptable fit: χ2(307) = 536.678, df = 239, χ2/df = 2.245, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.910; RMSEA = 0.064; SRMR = 0.056. Standardised path coefficient estimates are displayed in Fig. 3. Intrinsic motivation was positively related to all three dimensions of self-efficacy: ideation (β = 0.835, p < 0.001), conventions (β = 0.519, p < 0.001), and self-regulation (β = 0.694, p < 0.001). Interestingly, extrinsic motivation did not show a significant correlation with any form of self-efficacy. Besides, among the three dimensions of self-efficacy, only self-regulation was positively associated with writing performance (β = 0.405, p < 0.001). According to Hair et al. (2019), rs close to 0.25, 0.40, and 0.60 may be interpreted as low, moderate, and high levels of correlation. Thus, the positive relationships between intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy, as well as self-efficacy and performance, were of medium to large magnitude. The R2s of writing self-efficacy for ideation, conventions, and self-regulation, and writing performance in this model were 0.610 (p < 0.001), 0.381 (p < 0.001), 0.495 (p < 0.001), 0.126 (p < 0.05), respectively, meaning that approximately 61%, 38.1%, 49.5% and 12.6% of the variances in these variables can be explained by the model.

Standardised path coefficients of the structural model (Note. Dotted arrows indicate an insignificant direct path and arrows indicate a significant direct path (**p < 0.01). IM intrinsic motivation, EM extrinsic motivation, WSEI writing self-efficacy for ideation, WSEC writing self-efficacy for conventions, WSESR writing self-efficacy for self-regulation).

The Bootstrap method (2000 resamples) was used to test the significance of the mediating effect in the model, and we only found one significant indirect path, which was intrinsic motivation→writing self-efficacy for self-regulation→writing test grades (β = 0.281, S. E. = 0.122, p = 0.021), as the Bias-corrected confidence interval (BCCI) for the path did not contain 0 (95% CI = [0.042, 0.520]) (Preacher and Hayes 2008).

Discussion

This study examines the relationship between writing motivation, self-efficacy, and writing performance among Chinese fourth-grade students who demonstrate clear and steady writing motivation, coupled with a distinct understanding of writing self-efficacy. These findings corroborate the outcomes demonstrated by the multidimensional model of writing motivation and self-efficacy outlined in previous studies (Bandura 2012; Graham 2023).

Relationship between writing motivation and writing self-efficacy

Initially, it is crucial to recognise the distribution of writing motivation levels among Chinese elementary students, which predominantly ranges from 3 to 5 on the Likert scale, indicating a moderate to high level of motivation. Intrinsic motivation (Mean = 3.67) slightly surpasses extrinsic motivation (Mean = 3.34), consistent with global educational literature (Rocha et al. 2019). The average value for emotion regulation motives is notably lower (Mean = 2.66), suggesting that students may not perceive writing as a tool for managing negative emotions, potentially limiting their view of writing as an emotional regulation strategy. Conversely, students rated their engagement in writing activities the highest (Mean = 4.24), associating writing with enjoyment and fulfilment rather than a mere task (Graham et al. 2021).

Besides, students in this study consistently exhibit a high level of writing self-efficacy, reflected across all three measured subscales (3.85–4.08). This finding suggests that writing self-efficacy is prevalent among primary school students. Similarly, Zumbrunn et al. (2020) analysed elementary students’ writing self-efficacy and found that it generally scored above 3 on a 4-point scale. This aligns with previous research, which indicates that junior students tend to have more positive attitudes and higher writing self-efficacy compared to senior students (Knudson 1991; Pajares 2003). Furthermore, this observation supports educational policies that emphasise the cultivation of students’ self-efficacy as a crucial objective of national education (Ministry of Education of China et al. 2023).

In discussing the role of writing motivation, the following key findings are worth noting. Firstly, the SEM analysis uncovers that intrinsic motivation is significantly correlated with extrinsic motivations in writing among elementary school students in China. Although previous studies involved participants from more economically developed regions of China and employed different instruments to measure writing motivations, their findings are consistent with the present study, confirming that there is a moderate correlation between writing intrinsic and extrinsic motivations in Chinese primary students (Yeung et al. 2020). This correlation suggests that a student’s natural interest in writing can coexist harmoniously with the appreciation they gain from others.

Secondly, the relationship between intrinsic motivation and all three dimensions of self-efficacy is evident. This result is generally consistent with those of previous studies, that is, more intrinsically motivated students have higher self-efficacy (David et al. 2007; Hong et al. 2017). Notably, the link between intrinsic motivation and writing self-efficacy for ideation is particularly strong (β = 0.835). Intrinsic motivation is posited as a pivotal element in fostering creativity, given its capacity to elicit positive emotions, enhance cognitive flexibility, encourage adventurousness, and reinforce tenacity (Grant and Berry 2011). These psychological states, in synergy with intrinsic motivation, can cultivate an inclination towards creative endeavours, thus amplifying students’ self-efficacy in ideation (Karimi et al. 2022). It can be inferred that elementary students, when impassioned about writing and endowed with a spirit of exploration, are likely to develop a fortified belief in their ideational abilities.

Thirdly, only intrinsic motivation influences self-efficacy, while extrinsic motivation has no effect on primary students’ Chinese writing self-efficacy. This finding contrasts with the previous study’s findings, where extrinsic motivation plays a more significant role in students’ writing activities within the context of Chinese education (Ng et al. 2021; Ng et al. 2022; Yeung et al. 2020). The inconsistency may be attributed to the differences in socio-economic contexts between previous studies and the current study. Prior research has concentrated on more prosperous areas in China, such as Shanghai and Hong Kong, which are densely populated, highly competitive, and exhibit greater parental and teacher involvement in academics (Ng et al. 2021). In these environments, students may actively seek social recognition and develop self-recognition, thereby increasing their confidence in completing writing tasks. In contrast, this study was conducted in a northern Chinese city characterized by a medium level of economic development, where education is relatively less prioritized.

In the temporal dimension, the educational landscape in China has evolved significantly in recent years, particularly due to modernization efforts and policy reforms such as the “double reduction” (Shuang Jian) policy (Xue and Li 2023). These changes have altered teaching methodologies and the educational philosophies of teachers and parents, aiming to alleviate students’ burden in learning. In particular, the participants in this study are primary school students who have not yet faced the high pressure of an exam-oriented culture. Moreover, teachers are not allowed to rank students or give specific scores (Ministry of Education of China, 2021). Therefore, students may not regard outperforming others as their primary goal but may be more interested in pursuing a genuine interest in writing. Consequently, elementary students are likely to value personal learning interests above traditional markers of academic success, such as grades and social recognition. Given these developments, future qualitative analysis is essential to deepen our understanding of the motivations behind Chinese students’ engagement with writing.

Relationship between writing self-efficacy and writing performance

The findings of this study reveal that only writing self-efficacy for self-regulation has a significant impact on writing performance, while the predictive roles of self-efficacy for ideation and conventions are not significant. This stands in contrast to some previous findings. For instance, De Smedt et al. (2016) research on over 800 Belgian fifth and sixth graders reports that students with higher self-efficacy for ideation produced narratives of better quality. Notably, De Smedt and colleagues corrected all spelling, punctuation, and capitalization errors before scoring the students’ compositions, thereby reducing presentation effects, a step not taken in our research. Furthermore, the study by Yilmaz Soylu et al. (2017) identified self-efficacy for writing conventions as the only significant predictor of writing assessment scores. However, it is important to consider that their sample consisted of high school students, who focus on basic writing skills such as grammar, syntax, and spelling, which are critical for exam success. This context differs markedly from our study’s focus on younger students not yet subject to such exam pressures. As noted by Zumbrunn et al. (2020), the discrepancy in studies may be attributed to methodological differences, participant ages, and study locations. Therefore, it is imperative for future research to revisit these relationships to accommodate the diverse factors that relate to writing research.

Writing self-efficacy for self-regulation was the sole factor directly influencing the writing performance of fourth-grade elementary school students in China. This finding is supported by both theoretical and empirical evidence, which shows that writing proficiency is greatly influenced by self-regulatory strategies (Graham et al. 2017; Limpo and Alves 2017). These strategies are tied to a heightened awareness of one’s self-regulatory abilities (Chen and Pajares 2010; Limpo and Alves 2017). Similar patterns are observed in Limpo and Alves’ (2017) study with Portuguese middle students, underscoring the role of self-regulation in navigating the cognitive, affective, and behavioural aspects of writing.

Particularly, intrinsic motivation has a positive and indirect relationship with writing performance through self-efficacy for self-regulation, in line with the results of previous studies (Limpo and Alves 2017). This may be due to the fact that intrinsic motivation increases students’ enthusiasm to write, and self-efficacy for self-regulation also helps them to overcome difficulties encountered in writing to complete writing activities (Bruning et al. 2013; Ryan and Deci 2000). Consequently, intrinsic motivation can indirectly influence writing performance through self-efficacy for self-regulation. Despite the above-mentioned significant relationships, the motivational beliefs of Chinese primary school pupils in relation to writing constitute just a minor proportion of the variance observed in writing performance. This limited contribution can be traced to the notion that motivated beliefs represent a constituent writing element rather than the sole pertinent element. According to Graham (2018), the WWC model posits that writing proficiency is influenced by various elements, including objective knowledge, production processes, control mechanisms, and writing communities. Therefore, future research may include certain variables concerning students’ behavioural responses, such as engagement. This may increase the explained proportion of variance in writing performance.

Conclusion

The current research significantly contributes to the domain of writing motivation through several means. First, this research concurrently assessed the Chinese writing motivation and writing self-efficacy levels of fourth-grade primary school students. The findings not only confirm the presence of distinct and stable writing motivation and self-efficacy among these students but also substantiate the applicability of these instruments within the Chinese cultural context and regions with different economic development levels. Second, this study included writing performance as the dependent variable in the model, examining how students’ motivation and self-efficacy for writing relate to writing performance. Therefore, this study is significant for providing a comprehensive analysis of the interplay between motivational constructs and writing performance, deepening our comprehension of how Chinese students perceive motivation for writing within their cultural context.

Limitations and implications

While the study made some meaningful findings, there are still some limitations that should be addressed in future studies. Firstly, the research focused on narrative texts, which may not reflect the motivational impact of other writing genres. Since the performance of narrative writing is highly associated with motivation (Troia et al. 2022), this could lead to an overestimation of the relationship between intrinsic motivation and writing performance levels. Therefore, future research should comprehensively examine different writing tasks, including expository and argumentative essays, to better understand the influence of motivation on students’ writing performance (De Smedt et al. 2016). Secondly, the reliance on self-reported questionnaires to gauge writing motivation and self-efficacy introduces the risk of subjective bias and measurement error. Future studies could benefit from incorporating qualitative methods, such as interviews and observations, to obtain a more nuanced understanding of students’ writing behaviours and the challenges they face within specific contexts. Thirdly, the use of cross-sectional data limits the ability to discern dynamic changes and causal relationships among the variables (Rindfleisch et al. 2008). Future research could consider a longitudinal design to investigate whether students’ sub-dimensions of writing motivation and writing self-efficacy that affect their writing performance change across grade levels, and how the interactions between these factors change. This would offer valuable insights into the evolution of writing motivation and self-efficacy and their impact on writing proficiency over time.

Given the complexity of our current model, we did not incorporate different individual geographic and demographic variables, such as gender and socio-economic status, into our hypothesized model to mediate or moderate the relationships between motivation, self-efficacy, and writing performance. For example, the study only focused on a school in northern China with a medium socio-economic status, which limits the generalizability of the findings to other populations, such as rural areas or regions with different socio-economic statuses. Future research may involve these demographic factors and perform multi-group SEM to examine the intricate relationships between these variables. With the findings of the study, we aim to provide teachers with systematic and applicable teaching strategies to increase students’ writing motivation and self-efficacy, particularly focusing on intrinsic motivation and self-efficacy for self-regulation. In terms of writing instruction, educators must emphasise the importance of writing for future careers and assign value to writing to intrinsically motivate students and promote self-regulation (Urdan and Schoenfelder 2006). They should also employ strategies to improve students’ writing abilities while crafting authentic, challenging, but achievable writing tasks to boost student engagement, creativity, and achievement (Graham 2013; Rocha et al. 2019). Regarding the writing environment, a supportive atmosphere is essential according to the WWC model (Graham 2023). Teachers must model positive attitudes to create a classroom environment that fosters self-expression and creativity, which can enhance student engagement (Urdan and Schoenfelder 2006). Furthermore, it is crucial to facilitate students’ positive emotional expression through writing and help them manage negative emotions without fear of criticism (Bruning and Horn 2000; Zumbrunn et al. 2020). Educators can encourage students to write a story from various emotional perspectives, such as from the viewpoint of a character who feels happy or another who feels sad. This approach not only creates a safe space for emotional exploration, but also helps students express a variety of emotions through their writing.

Data availability

The raw data includes participants’ questionnaire responses and their test scores. To protect participants’ privacy, the raw data will not be made publicly accessible. However, the datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Alemayehu L, Chen HL (2023) Learner and instructor-related challenges for learners’ engagement in MOOCs: A review of 2014–2020 publications in selected SSCI indexed journals. Interact Learn Environ 31(5):3172–3194. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2021.1920430

Bandura A (1986) The explanatory and predictive scope of self-efficacy theory. J Soc Clin Psychol 4(3):359–373. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1986.4.3.359

Bandura A (1989) Human agency in social cognitive theory. Am Psychol 44(9):1175–1184. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.9.1175

Bandura A (2012) Cultivate self‐efficacy for personal and organizational effectiveness. In: Locke EA (ed) Handbook of principles of organization behavior, 2nd edn. Wiley, New York, pp 179–200

Boscolo P, Gelati C (2019) Motivating writers. In Graham S, MacArthur CA, Fitzgerald J (eds) Best practices in writing instruction. Guilford Press, New York, pp 51–78

Bruning R, Dempsey M, Kauffman DF, McKim C, Zumbrunn S (2013) Examining dimensions of self-efficacy for writing. J Educ Psychol 105(1):25–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029692

Bruning R, Horn C (2000) Developing motivation to write. Educ Psychol 35(1):25–37. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3501_4

Bulut P (2017) The effect of primary school students’ writing attitudes and writing self-efficacy beliefs on their summary writing achievement. Int. Electron J Elem Educ 10(2):281–285. https://doi.org/10.26822/iejee.2017236123

Camacho A, Alves RA, Boscolo P (2021) Writing motivation in school: A systematic review of empirical research in the early twenty-first century. Educ Psychol Rev 33(1):213–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09530-4

Camping A, Graham S, Ng C, Aitken A, Wilson JM, Wdowin J (2020) Writing motivational incentives of middle school emergent bilingual students. Read Writ 33:2361–2390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-020-10046-0

Chea S, Shumow L (2017) The relationships among writing self-efficacy, writing goal orientation, and writing achievement. In: Kimura K, Middlecamp J (eds) Asian-Focused ELT Research and Practice Voices from the Far Edge. IDP Education, Cambodia, pp 169–192

Chen JA, Pajares F (2010) Implicit theories of ability of Grade 6 science students: Relation to epistemological beliefs and academic motivation and achievement in science. Contemp Educ Psychol 35(1):75–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2009.10.003

David P, Song M, Hayes A, Fredin ES (2007) A cyclic model of information seeking in hyperlinked environments: The role of goals, self-efficacy, and intrinsic motivation. Int J Hum Comput Stud 65(2):170–182. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2006.09.004

De Smedt F, Landrieu Y, De Wever B, Van Keer H (2023) The role of writing motives in the interplay between implicit theories, achievement goals, self-efficacy, and writing performance. Front Psychol 14:1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1149923

De Smedt F, Van Keer H, Merchie E (2016) Student, teacher and class-level correlates of Flemish late elementary school children’s writing performance. Read Writ 29:833–868. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-015-9590-z

Graham S (2013) Best practices in writing instruction. Guilford Press, New York

Graham S (2018) A revised writer (s)-within-community model of writing. Educ Psychol 53(4):258–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2018.1481406

Graham S (2023) Writer (s)-Within-Community model of writing as a lens for studying the teaching of writing. In: Horowitz R (ed) The Routledge International Handbook of Research on Writing, 2rd edn. Routledge, New York, pp 337–350

Graham S, Camping A, Harris KR, Aitken AA, Wilson JM, Wdowin J, Ng C (2021) Writing and writing motivation of students identified as English language learners. Int J TESOL Stud 3(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.46451/ijts.2021.01.01

Graham S, Harbaugh-Schattenkirk AG, Aitken A, Harris KR, Ng C, Ray A, Wdowin J (2022) Writing motivation questionnaire: validation and application as a formative assessment. Assess Educ: Princ Policy Pract 29(2):238–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2022.2080178

Graham S, Harris KR, Kiuhara SA, Fishman EJ (2017) The relationship among strategic writing behavior, writing motivation, and writing performance with young, developing writers. Elem Sch J 118(1):82–104. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26546666

Graham S, McKeown D, Kiuhara S, Harris KR (2012) A meta-analysis of writing instruction for students in the elementary grades. J Educ Psychol 104(4):879–896. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029185

Grant AM, Berry JW (2011) The necessity of others is the mother of invention: Intrinsic and prosocial motivations, perspective taking, and creativity. Acad Manag J 54(1):73–96. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.59215085

Guan Y, Zhu X, Xiao L, Zhu S, Yao Y (2024) Investigating the relationships between language mindsets, attributions, and learning engagement of L2 writers. System 125:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2024.103431

Hair Jr J, Page M, Brunsveld N (2019) Essentials of business research methods. Routledge, New York

Hair Jr JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE (2010) Multivariate data analysis, 7th edn. Prentice Hall, London

Hidi S, Boscolo P (2006) Motivation and writing. In: MacArthur CA, Graham S, Fitzgerald J (eds) Handbook of writing research. Guilford Press, New York, pp 304–310

Hong JC, Hwang MY, Tai KH, Lin PH (2017) Intrinsic motivation of Chinese learning in predicting online learning self-efficacy and flow experience relevant to students’ learning progress. Comput Assist Lang Learn 30(6):552–574. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2017.1329215

Karimi S, Malek FA, Farani AY (2022) The relationship between proactive personality and employees’ creativity: the mediating role of intrinsic motivation and creative self-efficacy. Econ Res-Ekon istraž 35(1):4500–4519. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2021.2013913

Kline P (2013) Handbook of psychological testing, 2rd edn. Routledge, London

Kline RB (2008) Becoming a behavioral science researcher: A guide to producing research that matters. Guilford Press, New York

Kline RB (2023) Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press, New York

Knudson RE (1991) Development and use of a writing attitude survey in grades 4 to 8. Psychol Rep 68(3):807–816. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1991.68.3.807

Koo TK, Li MY (2016) A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J Chiropr Med 15(2):155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012

Limpo T, Alves RA (2017) Relating beliefs in writing skill malleability to writing performance: The mediating role of achievement goals and self-efficacy. J Writ Res 9(2):97–125. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2017.09.02.01

Limpo T, Filipe M, Magalhães S, Cordeiro C, Veloso A, Castro SL, Graham S (2020) Development and validation of instruments to measure Portuguese third graders’ reasons to write and self-efficacy. Read Writ 33:2173–2204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-020-10039-z

Lu Q, Zhu X, Cheong CM (2021) Understanding the difference between self-feedback and peer feedback: A comparative study of their effects on undergraduate students’ writing improvement. Front Psychol 12:1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.739962

Mallinckrodt B, Abraham WT, Wei M, Russell DW (2006) Advances in testing the statistical significance of mediation effects. J Couns Psychol 53(3):372–378. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.3.372

Ministry of Education of China (2021) Weichengnianren xuexiao baohu guiding [Minors in schools Protection Provisions of China.] Ministry of Education of China. Available via DIALOG. http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A02/s5911/moe_621/202106/t20210601_534640.html of subordinate document. Accessed 23 Oct 2024

Ministry of Education of China (2022) Yiwu Jiaoyu Yuwen Kecheng Biaozhun (2022 Ban) [Chinese Language Curriculum Guidelines for Compulsory Education (2022 Edition)]. Beijing Normal University Publishing Group, Beijing

Ministry of Education of China et al. (2023) Jiaoyubu deng shiba bumen guanyu jiaqiang xin shidai zhongxiaoxue kexue jiaoyu gongzuo de yijian [Opinions on strengthening science education in primary and secondary schools in the new era] Ministry of Education of China. Available via DIALOG. http://www.moe.gov.cn/srcsite/A29/202305/t20230529_1061838.html of subordinate document. Accessed 23 Oct 2024

Muthén LK, Muthén BO (2017) Mplus user’s guide, 8th edn. Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles

Ng C, Graham S, Lau KL, Liu X, Tang KY (2021) Writing motives and writing self-efficacy of Chinese students in Shanghai and Hong Kong: Measurement invariance and multigroup structural equation analyses. Int J Educ Res 107:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2021.101751

Ng C, Graham S, Liu X, Lau KL, Tang KY (2022) Relationships between writing motives, writing self-efficacy and time on writing among Chinese students: Path models and cluster analyses. Read Writ 35(2):427–455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-021-10190-1

Pajares F (2003) Self-efficacy beliefs, motivation, and achievement in writing: A review of the literature. Read Writ Q 19(2):139–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573560308222

Pajares F, Johnson MJ, Usher EL (2007) Sources of writing self-efficacy beliefs of elementary, middle, and high school students. Res Teach Engl 42(1):104–120. https://doi.org/10.58680/rte20076485

Pajares F, Valiante G, Cheong YF (2006) Writing self-efficacy and its relation to gender, writing motivation and writing competence: A developmental perspective. In: Hidi S, Boscolo P (eds) Writing and motivation. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley, pp 141–159

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF (2008) Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 40(3):879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Rasteiro I, Limpo T (2023) Examining longitudinal and concurrent links between writing motivation and writing quality in middle school. Writ Commun 40(1):30–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/07410883221127701

Rindfleisch A, Malter AJ, Ganesan S, Moorman C (2008) Cross-sectional versus longitudinal survey research: Concepts, findings, and guidelines. J Mark Res 45(3):261–279. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.45.3.261

Rocha RS, Filipe M, Magalhães S, Graham S, Limpo T (2019) Reasons to write in grade 6 and their association with writing quality. Front Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02157

Ryan R, Deci EL (2000) Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol 55(1):68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Sabti AA, Md Rashid S, Nimehchisalem V, Darmi R (2019) The Impact of writing anxiety, writing achievement motivation, and writing self-efficacy on writing performance: A correlational study of Iraqi tertiary EFL Learners. Sage Open, 9(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019894289

Schiefele U, Schaffner E (2016) Factorial and construct validity of a new instrument for the assessment of reading motivation. Read Res Q 51(2):221–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.134

Sun T, Wang C, Lambert RG, Liu L (2021) Relationship between second language English writing self-efficacy and achievement: A meta-regression analysis. J Second Lang Writ 53:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2021.100817

Troia GA, Harbaugh AG, Shankland RK, Wolbers KA, Lawrence AM (2013) Relationships between writing motivation, writing activity, and writing performance: Effects of grade, sex, and ability. Read Writ 26:17–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-012-9379-2

Troia GA, Wang H, Lawrence FR (2022) Latent profiles of writing-related skills, knowledge, and motivation for elementary students and their relations to writing performance across multiple genres. Contemp Educ Psychol 71:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2022.102100

Urdan T, Schoenfelder E (2006) Classroom effects on student motivation: Goal structures, social relationships, and competence beliefs. J Sch Psychol 44(5):331–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2006.04.003

Usher EL, Pajares F (2008) Self-efficacy for self-regulated learning: A validation study. Educ Psychol Meas 68(3):443–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164407308475

Walker CO, Greene BA, Mansell RA (2006) Identification with academics, intrinsic/extrinsic motivation, and self-efficacy as predictors of cognitive engagement. Learn Individ Differ 16(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2005.06.004

Wilson KM, Trainin G (2007) First-grade students’ motivation and achievement for reading, writing, and spelling. Read Psychol 28(3):257–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702710601186464

Wu H, Li S, Zheng J, Guo J (2020) Medical students’ motivation and academic performance: the mediating roles of self-efficacy and learning engagement. Med Educ Online 25(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/10872981.2020.1742964

Xu W, Zhao P, Yao Y, Pang W, Zhu X (2023) Effects of self-efficacy on integrated writing performance: A cross-linguistic perspective. System 115:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2023.103065

Xue E, Li J (2023) What is the value essence of “double reduction” (Shuang Jian) policy in China? A policy narrative perspective. Educ Philos Theory 55(7):787–796. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2022.2040481

Yao Y, Zhu X, Zhu S, Jiang Y (2023) The impacts of self-efficacy on undergraduate students’ perceived task value and task performance of L1 Chinese integrated writing: A mixed-method research. Assess Writ 55:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2022.100687

Yeung PS, Chung KKH, Chan DWO, and Chan ESW (2024) Relationships of writing self-efficacy, perceived value of writing, and writing apprehension to writing performance among Chinese children. Read Writ, 1–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-024-10512-z

Yeung PS, Ho CSH, Chan DWO, Chung KKH (2020) Writing motivation and performance in Chinese children. Read Writ 33:427–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-019-09969-0

Yilmaz Soylu M, Zeleny MG, Zhao R, Bruning RH, Dempsey MS, Kauffman DF (2017) Secondary students’ writing achievement goals: Assessing the mediating effects of mastery and performance goals on writing self-efficacy, affect, and writing achievement. Front Psychol 8:1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01406

Zhu X, Yao Y, Pang W, Zhu S (2023) Investigating the relationship between linguistic competence, ideal self, learning engagement, and integrated writing performance: A structural equation modeling approach. J Psycholinguist Res 52(3):787–808. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-022-09923-2

Zumbrunn S, Broda M, Varier D, Conklin S (2020) Examining the multidimensional role of self‐efficacy for writing on student writing self‐regulation and grades in elementary and high school. Br J Educ Psychol 90(3):580–603. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12315

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qingyang Li: conceptualisation/data curation/formal analysis/methodology/writing original draft. Yuan Yao: methodology/formal analysis/validation/writing review and editing. Xinhua Zhu: conceptualisation/project administration/supervision/writing review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University on October 26, 2023 (No. HSEARS20231013002). The data collection for this study took place in November 2023.

Informed consent

Before the study began, participants and their legal guardians were informed about the study’s aim and scope, how the data would be used, and their right to withdraw from the study at any time. Informed consent was obtained from each participant and their legal guardians before their participation in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Q., Yao, Y. & Zhu, X. The association between writing motivation and performance among primary school students: considering the role of self-efficacy. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1722 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04298-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04298-2

This article is cited by

-

Timing AI intervention in the writing process for low proficiency learners: relationship with motivation, self-efficacy, and performance

European Journal of Psychology of Education (2025)