Abstract

This study attempted to determine how political engagement, accreditation, and female autonomy controlled intimate partner violence (IPV) in the COVID-19 scenario. The empirical investigation used published statistics on IPV for 27 Indian states and two union territories. The investigation used methods such as principal component analysis, the technical inefficiency effects model, and nonparametric analysis of variance (ANOVA). The results showed that Odisha, West Bengal, Uttarakhand, and Chhattisgarh were the states most efficient in regulating IPV. The Judiciary and Public Safety Score, female autonomy, and political involvement and accreditation, as evaluated based on female Members of Parliament (MPs) and Members of the Legislative Assembly (MLAs), are the most important factors in minimizing state-managed inefficiency. The study concludes with pertinent conclusions, some policy recommendations, and a focus on the trajectory of future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intimate partner violence (IPV) threatens millions of people worldwide (Patra et al. 2018). Any instance of IPV constitutes a violation of fundamental human rights. IPV has detrimental effects on the victim’s psychological and physical wellness as well as on any offspring of this broken relationship (Patra et al. 2018).

IPV is any behaviour that causes psychological, physiological, or sexual harm to someone in an intimate relationship, whether married or just living together. The concept of IPV includes any kind of psychological, physical, or sexual abuse or control (Krug et al. 2002). IPV is commonly misunderstood as domestic violence. However, these two concepts are legally different. In cases of domestic violence, an assailant may have one, two, or more family members. Maltreatment, be it emotional, physical, or sexual, faced by a family member or other person is referred to as domestic violence (American Psychological Association et al. 1996). However, with IPV, only two people are involved: the assailant and the victim (Cunradi, 2010). IPV is commonly a unidirectional male-to-female phenomenon (Morse, 1995; Archer, 2000). Nonetheless, female-to-male IPV exists, but it is probably less common if we consider global experiences (Straus, 1995; Schafer et al. 1998; Cunradi, 2010). Global literature has documented that nearly half of IPV cases are bidirectional, with the remaining half being either female-to-female or male-to-female violence (Straus, 2005; Caetano et al. 2005).

The Indian Penal Code (IPC) has no provisions for IPV. However, IPC 498A addresses this issue in a moderately different manner. Pursuant to the Criminal Law (Second Amendment) Act, 1983 (46 of 1983), Section 498A of the IPC was created specifically to address domestic violence committed by a spouse or husband’s relatives. Section 498A of the IPC is the only Indian legal amendment covering IPV. It states that torturing a spouse or close family member of a spouse will be recognized as IPV. Anyone who subjects a woman or her close relative to cruelty while they are married is subject to a period of imprisonment that might last up to three years, as well as a fine (derived from the India Code, 1983). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recognize four categories of IPV: physical assault, sexual assault, stalking, and psychological abuse (CDCP, 2016). Although IPV can be man-to-woman or woman-to-man, IPC 498A considers only man-to-woman cases. The reality is that female-to-male IPV in Indian society is rare. In Indian society, marriage is universal and men are inevitably the rulers of both households and society. Live-in relationships are atypical. Some metro cities witness live-in relationships, but these relationships are very unpopular. In the absence of a proper Indian legal amendment for IPV, we consider the crimes reported under Section 498A of the IPC as registered IPV cases. Notably, IPV is an androgynous phenomenon predominantly committed by male spouses toward their female partners (Gupta and Nazrin, 2020; Peterman et al. 2020; van Gelder et al. 2020).

Police forces are considered the defenders of society. The defender’s role is more acute in developing countries, and this applies to India. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, the role of the police changed significantly; they became more like health warriors than defenders. The changing role of the police has increased the likelihood of crimes, particularly those arising from personal relationships. IPV is a form of personal crime, and there was concern that lockdowns or stay-at-home policies could escalate crimes against women (Vives-Cases et al., 2021b). Myth became reality through the experiences of couples; 64.2% of those who experienced IPV since COVID-19 said that it was either new to their relationship (34.1%) or worsened during the pandemic (26.6%) (Lyons and Brewer, 2022). Socioeconomic crises and humanitarian disasters may be the causes of the increase in IPV (Vives-Cases et al. 2021a). Episodes of IPV may be precipitated by social distancing, lockdowns, staying at home, and self-isolation (Moreira and Da Costa, 2020; Evans et al. 2020). Not only did IPV incidences escalate during the pandemic, but the severity of physical IPV also increased compared with the previous three years (Gosangi et al. 2021). Increasing social, economic, and emotional stress due to the lockdown, quarantine, and isolation increased the likelihood of IPV (Gupta and Nazrin, 2020; van Gelder et al. 2020).

Due to the serious social, economic, and public health consequences of cruelty against women (Krug et al. 2002; Bott et al. 2012), its elimination has been included as one of the Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, 2015). Accordingly, it is important to understand how efficiently a state or country regulates IPV, specifically in the context of COVID-19. However, no studies have been conducted on this issue.

This context inspired us to examine estimates of the efficiency of efforts to suppress IPV in various Indian states under the COVID-19 scenario. This is particularly important given the changing responsibilities of the police. This study had two objectives: to explore the efficacy of IPV regulation under a pandemic scenario by states and union territories (UTs) in India and to identify the determinants of the inefficacy of states and UTs in regulating IPV. This study aimed to clarify the significance of women’s political engagement, accreditation, inherent autonomy, and the state’s judicial and public safety status in regulating IPV during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This study is the first of its kind to explore efficiency estimates and the factors responsible for manageable inefficiency in regulating IPV in Indian states and UTs. No earlier studies, either national or international, have explored these topics. The study area, objectives, methodology, and most importantly, the choice of inefficiency effect variables make this study novel. It is the first study to consider female political engagement and accreditation, female autonomy, as well as “Judiciary and Public Safety” status as inefficiency effects variables.

The study is structured as follows. The theoretical underpinning, secondary data sources, econometric model, and relevant variables of this empirical investigation are discussed in Section “Methods”. The empirical findings and their discussion are presented in Sections “Results” and “Discussion”, respectively. Pertinent conclusions, policy recommendations, and a focus on the trajectory of future research are presented in Section “Conclusion”.

Methods

Theoretical foundation

The application of efficiency estimates in comparing performances is common in research. Performance efficiency can be computed either by using the Stochastic Frontier Approach (SFA) or by Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA). SFA is parametric, whereas DEA is a non-parametric technique. Both techniques have several applications. Both approaches have their strengths and weaknesses. The application of SFA for efficiency measurement necessitates a clearly defined input-output relationship, and that relationship must be presented as a widely acknowledged production function. Typically, a production function with a broader scope, such as the “Translog production function,” is utilized for this. The application of SFA in regulating crime is rare in the literature (Maity and Sinha, 2018). Interestingly, DAE is frequently used to assess the efficiency of police force performance since it allows us to incorporate more than one outcome variable, which is required in this situation. The use of SFA restricts us to using a single outcome variable. If we can define a single, well-accepted outcome variable as the basis of comparison of the performances of different decision-making units, then only the application of SFA is permissible. Thus, when we use SFA to measure the efficiency of states and UTs of India in regulating IPV within a stochastic production frontier framework considering a single output, the study becomes unique.

Based on Maity and Sinha (2018) and Murray and Frenk (2001), the theoretical foundation of the present study conceptualizes its IPV-regulating efficiency. The well-accepted outcome variable here is the “rate of intimate partner violence (IPV),” and as the lower the rate, the greater the efficiency, we have considered the reciprocal of the “IPV” as the output of the production frontier. On the vertical axis of Fig. 1, the relevant output is measured. Contrarily, the horizontal axis measures the societal input set.

Where m is the accomplished degree of crime-regulating output and (l + m) is the prospective output, Eq. 1 is described as the “system delivers relative to its prospective” (Murray and Frenk, 2001). To gauge the efficacy of the crime-regulating system, a systemic instrument is necessary. The most effective instrument for this is Farrell’s (1957) output-oriented measure of technical efficiency, which defines technical efficiency as the proportion of actual to the highest attainable outputs (Maity, 2011). In the current study, the “stochastic production frontier (SPF)” has been used to assess the technical efficacy of various Indian states in reducing IPV in the COVID-19 scenario. Battese and Coelli’s (1995) two-step technical inefficiency effects (TIE) approach may be applied to compute both the efficiency score and the variables causing inefficiency in IPV management across Indian states simultaneously. The corresponding econometric model is presented thereafter.

Methodology

This section presents the data sources, variables, and econometric model for this empirical investigation.

Data Source

This study is primarily empirical and is based on published data. Relevant data for this study is compiled from numerous secondary data sources. The study involves 27 Indian states and two UTs, viz., Delhi and Jammu & Kashmir. To facilitate the application of Battese and Coelli (1995), we need to specify three core variables, viz., output, inputs, and exogenous variables. The present paper involves seven inputs and eleven exogenous variables. The output variable is the reciprocal of the rate of intimate partner violence (IPV). The main data source is the “National Crime Record Bureau (NCRB).” The crime rate and statistics related to crime control mechanisms are assembled from the NCRB. Table 1 shows the comprehensive explanations of the variables as well as the data sources.

The current study is being accomplished from 2019 to 2022 to explore how the COVID-19 pandemic would affect IPV.

It is possible to measure the technical efficacy of the Indian states’ IPV regulations by taking panel data into account as well. Nevertheless, the efficiency study is carried out using data from 2021 due to the unavailability of panel data for some inputs and exogenous variables. Therefore, cross-sectional data is used in this efficiency analysis utilizing the inefficiency effects model.

Variables

The application of the “Technical Inefficiency Effects Model (TIEM)” of Battese and Coelli (1995) needs three types of variables (Maity et al. 2020; Maity and Barlaskar, 2022). Foremost, it is crucial to figure out a useful output indicator that captures the state’s efficacy in regulating the IPV. For identification, an adequate list of inputs that are directly connected to output production is required. Finally, another set of variables whose influence over crime control outcomes cannot be ignored; however, by no means can they be recognized as inputs. These non-crime-regulating variables are termed exogenous’. These exogenous variables are included in the analysis to capture the influence of non-crime-regulating factors on regulating crime.

Output

The comparison of efficiency across Indian states and UTs in regulating IPV is only possible if we can identify an adequate output that proxies the crime-regulating mechanism. As our objective here is to explore the inter-state discrepancies in regulating IPV during the pandemic, we consider the rate of IPV as the output variable. WHO (2013) defines IPV as any behaviour in an intimate relationship that harms the individuals involved physically, psychologically, or sexually. Consequently, the cases filed under “IPC-Section 498A” may be considered reported IPV-related offenses. The NCRB provides us with the total as well as the rate of crime reported under Section 498A. Our study area is Indian states and UTs, which are subject to variation in population size, so it will be appropriate to consider the rate of intimate partner violence (IPV) for further empirical analysis. Subsequently, it is undeniably true that efficiency increases with decreasing crime; the “reciprocal of the IPV” is the output component for this investigation.

Inputs

A couple of distinct options are available for input choices, viz., physical quantities or expenditures in monetary terms, like per-capita expenditures of the relevant variables. Since our goal is to examine the efficiency of crime control across Indian states and UTs, the primary inputs are measures of crime control, such as the overall strength of police, the number of people arrested, the number of prisons, etc. Accordingly, physical quantities for these variables will be appropriate to consider, and we exactly do the same. Moreover, to address the differences in population size, the number of police is standardized by considering “the proportion of policemen serving per 100,000 people.” Together with these physical quantities of input variables, we have also considered some monetary expenditures, like “Per-capita Police Expenditures”, and “Per-capita Net State Domestic Product” as inputs. Altogether, seven inputs are included in the efficiency analysis. Table 1 lists each input along with a brief description of what it means.

Exogenous

Patently, improved law-and-order conditions are not an exclusive outcome of well-performing crime-regulating mechanisms (Dinnen, 2000). Even after having well-performing crime control mechanisms, we fail to achieve a zero-crime society. The influence of these non-crime-related variables cannot be ignored. However, by no means can they be identified as inputs to regulating crime. Such variables are termed exogenous variables. These variables are extremely important, especially when we are exploring the determinants of inefficiency across states. These variables are specially utilized to facilitate the inefficiency effects analysis. Notably, our objective here is to investigate the role of female political engagement and accreditation in regulating IPV, which is performed by including the proportion of female legislators in each state’s and UT’s legislature and parliament (female MPs and MLAs) as exogenous variables in the model. Another interesting exogenous variable included in the study is the “Female Autonomy Index (FAI),” an amalgamated index measuring the degree of female autonomy across Indian states and UTs. The detailed specification (Modality List) of the FAI is furnished in Table A.1 in the appendices. Finally, the exogenous variable “Judiciary and Public Safety Score (JPSS)” delineates the scenario for law and order in any state. Altogether, eleven exogenous variables are involved in this analysis. The exogenous variables, together with their definitions, are furnished in Table 1.

We can show the model construction flowchart because we have a clear understanding of the theoretical foundation and can identify the output, inputs, and exogenous variables. That is exactly what Fig. 2 accomplishes.

Econometric model

The cross-sectional SPF model is presented by Equation 2:

Here, y, x and β are the crime regulating outcome, vectors of inputs, and parameters respectively and i presents a cross-sectional unit. These parameters are to be estimated. All variables, viz., output and inputs are expressed in log terms. Lag transformation is common for all variables. \(\exp ({V}_{i})\) is the random disturbance. Two widely used forms of production functions are- Trans-log and Cobb-Douglas production function. The specification of the production function is an apriori requirement for estimating Equation 2. The likelihood-ratio (L.R.) test offers assistance concerning the decision of the type of production function to use. Testing the null hypothesis of the combined insignificance of the second-order elements of the Trans-log production function may lead to the conclusion that the Cobb-Douglas production function may be preferable to the Trans-log. Accordingly, the null hypothesis can be specified as follows:

The corresponding test statistic is:

where, \(L.R\sim {\chi }_{k}^{2}\); k = number of restrictions, (Coelli et al. 2005)

Here, \({L}_{CD}\) and \({L}_{TL}\) are the restricted (Cobb-Douglas) and unrestricted (Trans-log) maximum likelihood functions respectively.

Following, Kumbhakar et al. (1991), with an error is one-sided, the Eq. 2 can be reframed as:

Here, the assumption concerning the distribution of Vi is that it is IID Normally distributed with mean 0 and variance \({\sigma }_{V}^{2}\). \({U}_{i}\) is also assumed to be IID Normal with \(({\omega }_{i}\delta ,{\sigma }_{U}^{2})\). In a firm’s production, the technical inefficiency over time is depicted by a vector of (pxq), explanatory variables included in \({\omega }_{i}\). Corresponding coefficients of unknown vectors of (qxp) are given by δ.

The associated distribution of \({U}_{i}\) is Truncated Normal with the assumption that \({U}_{i}\) and \({V}_{i}\) are mutually independent and \({x}_{i}\) is non-stochastic (Stevenson, 1980).

Corresponding to the SPF presented in Eq. 5 the TIE of the ith state may be represented by the following equation (Battese and Coelli, 1995):

Here, \({\varpi }_{i}\sim TN(0,{\sigma }_{U}^{2})\). Where TN stands for truncated normal. The truncation point is \(-{\omega }_{i}\delta\), that is, \({\varpi }_{i}\ge -{\omega }_{i}\delta\). Thus \({U}_{i}\sim N({\omega }_{i}\delta ,{\sigma }_{U}^{2})\).

Maximum likelihood estimators of the parameters of the SFP function and the inefficiency impacts are simultaneously provided by the application of the Battese and Coelli (1995) model. Concomitantly, the estimates of the corresponding variance parameters are given as follows:

\({\sigma }^{2}={\sigma }_{V}^{2}+{\sigma }_{U}^{2}\) and \(\gamma =\tfrac{{\sigma }_{U}^{2}}{{\sigma }^{2}}\), where γ ranges from 0 to 1. The specified model is estimated by using FRONTIER-4.1, developed by Coelli, (1996).

Subsequently, the model to be estimated for comparing and identifying the determinants of efficiency across Indian sates and UTs in regulating IPV based on specified set of output, inputs and exogenous variables is given be Eqs. 7 and 8.

Here ln indicates natural logarithm with base e.

The corresponding technical inefficiency effects (TIE) equation is:

Equation 7 is specified by assuming log-liner Cobb-Douglas production function will be appropriate for our purpose.

Results

The mentioned objectives are explored empirically in this section.

ANOVA of the rate of intimate partner violence (IPV)

In Indian society, women are considered inferior to men (Sultana, 2012). Men are the undisputed leaders of the family, and anything that happens to women within the family is considered a private matter. Women kept silent on such issues. However, the scenario is not the same for all Indian states. In some states, women are treated equally to men, and they receive respect and dignity from society. It makes sense that crimes against women, especially IPV, will vary throughout Indian states given the status of women in society. The discussion related to efficiency in regulating IPV will be meaningful if and only if there are discrepancies in reported IPV. We have used 27 Indian states and 2 UTs in a non-parametric ANOVA to confirm these disparities. Table 2 displays the test results.

At a 1% level, the null hypothesis that there is no inter-state variance in IPV among Indian states and UTs is rejected. This follows from the tabulated result, which shows a high F-statistic of 65.521. The existence of inter-state variance in reported IPV is guaranteed by the high value of F-statistics. Therefore, it will be pertinent to evaluate the efficiency of various Indian states and UTs in regulating IPV. Additionally, this outcome suggests that there must be some underlying causes for the inter-state variability in IPV.

Cobb-Douglas versus trans-log production function

We may select the proper functional form of the production function using the log-likelihood ratio (LR ratio) test (Coelli et al. 2005). Here, we have two options: the generalized Trans-log production function or the restrictive Cobb-Douglas production function. Table 3 depicts the LR ratio test result.

The statistical insignificance \({\chi }^{2}\) restricts us from choosing the Trans-log production function over Cobb-Douglas. The test result as depicted in Table 3 indicates that the simplest form of the Trans-log production function, that is, Cobb-Douglas, is more appropriate in our case. Table 3 shows that compared to Cobb-Douglas regression, the associated value of the log-likelihood functions for Trans-log regression is significantly lower. Consequently, we consider a Cobb-Douglas production function while doing the subsequent estimation and reject the Trans-log form.

State-wise rate of intimate partner violence under COVID-19 scenario in India

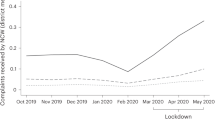

The first confirmed COVID-19 case in India occurred on January 27, 2020, in Thrissur, Kerala. Thenceforth, three medical students who had travelled from the epicentre, Wuhan, China, were found to be COVID-19 positive on January 30, 2020. A lockdown was thus declared for the whole country on March 25, 2020. This period was recognized as the period of the first wave of COVID-19 in India. Reportedly, the second wave commenced in March 2021, and it was even more cataclysmic compared to the first wave. Thus, to understand the pandemic scenario, the second wave will be more appropriate than the first one. Accordingly, the study includes the IPV across Indian states for three periods: 2019, 2020, and 2021. Figure 3 shows a graphical illustration of the IPV among Indian states.

According to the data, IPV increased significantly in all Indian states in 2021. By focusing on IPV cases that have been reported in all Indian states for 2021, the COVID-19 scenario’s impact on IPV may be better understood. For each of the three designated periods, Assam has the highest IPV on record. From 70.7 in 2019 to 75.0 in 2021, the rate increased sharply. Delhi has the second-highest rate, and a similar escalation is noted there as well. From 40.8 in 2019 to 48.9 in 2020, Delhi’s IPV grew. The rate only showed a declining tendency in a few states, such as Goa, Gujarat, etc. This graphical display supports the idea that during a pandemic, recorded IPV increases throughout Indian states and Union Territories. More research is needed to determine how Indian states and UTs regulate IPV.

IPV regulating efficiency estimates of Indian states and UTs

The police force is considered the backbone of maintaining law and order in any country. However, COVID-19 has changed the role of the police force. During the COVID-19 scenario, the police force was not only responsible for maintaining their primary duties (maintaining law and order) but also served as a liaison between health agencies. In fact, the police force in Indian states and UTs become health warriors as the COVID-19 epidemic spreads. Consequently, the police department’s social obligations surpass its obligations to reduce crime in some manner. Contrarily, during this time, the crime rate escalated, and according to the NCRB (2021), IPV sharply elevated during the pandemic. Subsequently, it will be appropriate to collate how states and UTs in India are performing in reducing IPV under an epidemic scenario. The apriori condition of heterogeneity for such an analysis was verified earlier through a non-parametric ANOVA. Notably, efficiency scores are a measure of relative performance. It indicates how well one state is doing in reducing and/or regulating IPV in comparison to the most efficient one. By using the benchmark of 0.674, the overall mean efficiency score, a state’s relative position, efficient or not, is determined (Maity and Sinha, 2018; Maity and Barlaskar, 2022). Therefore, a state will be considered technically efficient if its efficiency score exceeds the overall mean efficiency score, and vice versa. In particular, West Bengal has a technical efficiency score of 0.995, which is greater than the overall mean efficiency score. Consequently, compared to the other mentioned states and UTs, the state is thought to be technically effective in regulating IPV (Maity and Burlaskar, 2022). This benchmark results in the fact that out of 29 states and UTs, only 16 are considered technically efficient in regulating IPV. This indicates that 55% of states are efficiently regulating IPV. Figure 4 displays the efficiency scores for the various Indian states and UTs.

The figure discloses that Odisha, West Bengal, Uttarakhand, and Chhattisgarh achieve the top three efficiency scores. West Bengal and Uttarakhand hold the second position. It is noteworthy that West Bengal is the only state in the top-ranking list whose chief minister is a woman. In actuality, the Chief Minister also serves as the Minister of Health and Family Welfare. Contrarily, Tripura and Haryana are the two worst-performing states.

Notably, the efficiency score ranking of the state does not consider the actual outcomes of crime regulation and simply shows the relative performance of the subject state. Jharkhand, for example, is rated 19th on the list with a relative efficiency score of 0.439, which is considered inefficient. However, concerning the state’s real IPV-regulating achievements, Jharkhand ranked ninth out of twenty-nine states and UTs with IPV 4.9 in 2021 (NCRB Report, 2021). The current crime-regulating system’s efficiency rating stipulates that Jharkhand might have lowered the IPV further if it could manage crime as well as Odisha.

Determinants of output and efficiency

The implication of female autonomy and female political engagement and accreditation in regulating IPV across states and UTs of India is explored in this section. Table 4 lists the estimates of all coefficients along with the related t-ratio.

The TIE model has two parts, viz., the input-output relationship and the inefficiency effects analysis. The table’s first part presents the input-output orientation. The reciprocal of the IPV is the output. A list of inputs, like ‘Arrested,’ ‘Jails,’ ‘Jail Staff,’ ‘Police,’ ‘Police expenditures,’ ‘Police Station,’ and ‘Per-capita NSDP’ (PNSDP), in the SPF framework corroborates significant influence on output. The inputs, like ‘Arrested’,’ Jails,’ ‘Police,’ and ‘PNSDP,’ reduce the rate of IPV (as these variables are in positive relation to the reciprocal of IPV) across Indian states. On the contrary, ‘Jail Staff,’ ‘Police Expenditures,’ and ‘Police Station’ are in a paradoxical relation to IPV. The estimated coefficients of these variables predict that an increase in these variables will also increase IPV during a pandemic. All the estimated coefficients are statistically meaningful.

The empirical results pertaining to the calculated coefficients of inefficiency effects are particularly fascinating. The study includes 11 exogenous variables to explore the possible reasons behind the inefficiency in regulating IPV across Indian states and UTs. Notably, ‘Urban,’ ‘Sex-ratio,’ ‘Poverty,’ ‘Female Literacy Rate (FLR),’ ‘Judiciary and Public Safety Score (JPSS),’ ‘Female MPs,’ ‘Female MLAs,’ and ‘Female Autonomy (FAI)’ are the determinants of the state’s controllable inefficiency in administering IPV. The estimated coefficients of these exogenous variables are statistically significant. These factors are responsible for the inefficiency on the part of the state in regulating IPV efficiently. In the SFA framework, these manageable factors help regulate IPV. The negative sign suggests that these exogenous factors are contributing better to increasing the state’s ability to regulate IPV with greater efficiency. As disclosed in the table, the exogenous variables that negatively affect the state’s inefficiency in regulating IPV are ‘Sex ratio,’ ‘Female Literacy Rate (FLR),’ ‘Judiciary and Public Safety Score (JPSS),’ ‘Female MPs,’ ‘Female MLAs,’ and ‘Female Autonomy (FAI).’ Conversely, ‘urbanization’ and ‘poverty’ are the main factors aggravating the state’s inability to manage IPV. Notably, here ‘Female MPs and MLAs’ are the proxy to epitomize female political engagement and accreditation, and the composite index FAI quantifies females’ autonomy for a particular state. Concerning FAI, a higher value indicates higher female autonomy, and vice versa. Each of the aforementioned exogenous factors is statistically significant at various levels.

The discussion section presents the possible reasons for the empirical findings.

The statistical significance of all variance components reflects the stability of the proposed model. The statistical significance of γ ensures half-normal distribution of the error term. Notably, the estimated sigma-squares (\({\hat{\sigma }}_{s}^{2}\)), 4.146 is statically significant demonstrating the accuracy of the assumption made regarding the distribution of the composite error term. The variance parameter, γ measures the proportion of overall to specific state variability and the positive and significant value of it establishes the essentiality of the study. Here, value of γ is positive and it is statistically meaningful, means state-specific technical efficacy is relevant in explaining the overall diversity in IPV regulation. Moreover, the viability of the model is well understood by the relatively large estimated values of γ and \({\hat{\sigma }}_{s}^{2}\). The statistical significance of γ indicates the validity of the application TIEM for Indian states in regulating IPV. In actuality, the statistically significant values of the variance components ensure the validity, appropriateness, and reliability of the model.

The high negative log-likelihood value of −15.439 confirms the model’s convergence. Notably, the corresponding Likelihood Ratio Chi-squares value is also high at 41.409, and it is statistically meaningful with a p-value equal to 0.004. These values demonstrate the appropriateness and robustness of the specification.

Here, we have utilized a composite index as an exogenous variable. Thus, it is imperative to check the endogeneity. Eventually, the appropriateness of the estimation technique is checked by conducting the endogeneity test. Table 5 presents the result.

According to the table, the estimates for the Wu-Hausman and Durbin (score) values are 0.0097 and 0.0030, respectively, with corresponding probabilities of 0.922 and 0.958. The test result permits us to conclude that the factors are exogenous. Notably, the instruments for the FAI consist of three separate indices.

Discussion

Under the coronavirus scenario, police forces appeared to play a different role as health warriors. Simultaneously, a significant number of men lost their jobs, and a long period of lockdown caused insecurity concerning earnings. Such circumstances make the lives of female partners miserable. The enhanced IPV across Indian states demonstrates this fact. In light of the aforementioned circumstances, it becomes important to examine the state’s efficiency in regulating IPV and to pinpoint the root causes of the achievement gaps across Indian states. Thus, this analysis will enable us to pinpoint the causes of the state’s inefficiency in upregulating IPV. The study involves 27 states and 2 UTs. Based on the established benchmark, 55% of the sample turns out to be efficient. The state of Odisha receives the highest efficiency rating of 0.997, and the lowest is for Haryana (0.070). The wide differences in the efficiency score indicate discrepancies across states in regulating IPV under a pandemic scenario. Thus, beyond the input-output relationship, it demands further investigation to identify the factors responsible for such discrepancies. The input-output orientation in the SFA framework and the assessment of inefficiency effects are two components of the empirical estimates of the SFA model (Maity and Barlaskar, 2022). A Cobb-Douglas production function is utilized in the SFA framework to represent the input-output conjunction as directed by the results of the LR test. Nearly all input variables in the SPF framework have statistically significant relationships with output. However, some of the estimated coefficients of the inputs, such as jail staff, police expenditures, and police stations, give paradoxical results. The inputs like “arrested,” “jails,” “police,” and “PCNSDP” predict that the escalation of these variables will help in regulating IPV across Indian states. Such a result is quite obvious, as all these except PCNSDP are direct crime-regulating instruments; hence, an increment in these instruments as expected may have some direct positive effect on reducing crime. An increase in PCNSDP means the availability of more resources for the welfare of the citizens and, thus, more resources available for regulating crime, including IPV. Our primary concern is the paradoxical input-output relationship that we obtained for jail staff, police expenditures, and police stations. The increase in jail staff and police expenditures may have a direct effect on regulating crime; however, such tools might not be able to directly control a specific crime, such as IPV. (Bullinger et al. 2021). IPV is a rarely reported crime in Indian society, and unless the consequences are very serious, the victims may not be punished with imprisonment (Koenig et al. 2006). Thus, an increase in jail staff may not have a direct effect on regulating IPV (Bullinger et al. 2021). Under the COVID-19 scenario, an increment in police expenditures may be due to securing the health protection of the police forces, which act as supportive staff for Indian states and UTs (Ghosh, 2020). Such increased expenditures may not have an impact on regulating crime; rather, they may be more effective in improving the health scenario of Indian states and UTs. An increase in the number of police stations means a higher likelihood of reporting crime. Moreover, to make women feel comfortable reporting any crime against them, the Indian government introduced some special women-run police stations where women can go and comfortably report any crime, including IPV, against them. The increase in reported IPV due to the increase in police stations may be a consequence of the ease of reporting such crimes (Hadeed and El-Bassel, 2006). Notably, proficiency in regulating crime is not the sole outcome of efficient utilization of existing crime-regulating machines and available resources; the truth is that socio-economic and demographic issues have an impact on the result (Uthman et al. 2009). These factors are adequately regarded as exogenous factors rather than being classified as inputs. This research uses eleven exogenous factors to pinpoint the causes of states’ inefficiency in non-regulating IPV. To explore our second objective, we have included three exogenous factors, namely, ‘Female MPs’ and ‘Female MLAs’ and ‘Judiciary and Public Safety Score (JPSS).’ The first two exogenous variables are used as proxies to illustrate the effect of females’ political engagement and accreditation on reducing IPV. Contrarily, JPSS illustrates the role of good governance in regulating IPV. The empirical findings documented positive and significant impacts of ‘Urban’ and ‘Poverty,’ indicating that increased urbanization and poverty increase the inefficiency of regulating IPV across Indian states and UTs. Urbanization means a percentage increase in the urban population, which is mainly possible due to the rural-to-urban migration of unskilled laborers in search of a job. These labor forces are mainly engaged in the informal sector. They mainly stay in suburban areas. COVID-19 and the consequent lockdown caused loss of jobs, lack of income, distress, and disappointment for them. COVID-19 increases poverty across the country (Gupta and Nazrin, 2020; Vives-Cases et al. 2021a; van Gelder et al. 2020). They are forced to be reverse-migrated. The female partner becomes the soft target for draining all the frustration from her male counterpart (Birkley and Eckhardt, 2015). Moreover, in Indian society, a wife is symbolized as Laxmi (the goddess of resources), who brings good luck to her husband. The wife is considered unlucky for any adverse luck for the husband, and to escape from bad luck, the husband is often advised and sometimes believed that the wife should be excluded from his life (Morris et al. 2023). Such Indian societies always blame women for infertility (Morris et al. 2023). Giving birth to a girl child may also cause anguish for the female partner (Morris et al. 2023). Poor, low, or no education are the main sources of such a mentality (Jeyaseelan et al. 2004). This may be the reason for the negative influence of ‘Urban’ and ‘Poverty’ on the efficient regulation of IPV. Conversely, significant effects with a negative sign are reported for the exogenous variables: sex ratio (SR), female literacy rate (FLR), JPSS, female MPs, female MLAs, and FAI. The improvement of these exogenous factors helps in increasing efficiency in regulating IPV across Indian states and UTs. Unquestionably, favorable sex ratios and increased FLR give a protesting voice to the voicless (Prasad, 2021), increase reporting of IPV, and eventually increase efficiency in regulating the same. The paper mainly involves scrutinizing the role of female autonomy and political accreditation in regulating IPV. Three exogenous factors, viz., female MPs, female MLAs, and FAI, demonstrate the consequences of females’ political engagement, accreditation, and autonomy, respectively (for details, check Table A.1 in the appendices) in a specified state. All these variables demonstrate a desirable outcome. The escalation of these three variables helps in escalating the efficiency of sampled UTs and states in reducing IPV. In literature, we find females’ political accreditation always produces a better society and a better socio-economic scenario (Chattopadhyay and Duflo, 2004; Maity and Barlaskar, 2022). Unfortunately, only West Bengal has a female chief minister among the states and UTs in our sample; hence, in this research, political leadership is proxied by the proportion of females in parliament and the legislative assembly. Notably, West Bengal, the only female-governed state here, ranked second in efficiency score in regulating IPV. Political leadership is a stepping stone towards decision-making and empowerment. It empowers female leaders to speak out against such crimes on a large platform and to force the government to administer proper law and order for female protection. Such leaders become role models for others and motivate other women to speak out against injustice and irrationality (Iyer et al. 2012). In Indian society, men are the undisputed leaders of the family, and anything within the family is very private. It gives enough opportunity for the male partner to behave oppressively towards the female partner. Moreover, social stigma, income, livelihood, and social insecurity protect females from reporting such crimes (Sabri et al. 2014). All these make IPV a rarely reported crime (Sabri et al. 2014). The knowledge of such ground realities enables female leaders to administer proper laws and other machines for regulating IPV (Iyer et al. 2012). This is the reason for the escalation of efficiency with the increase in female MPs and female MLAs. Three separate autonomy indices—females’ decision-making, females’ economic, and females’ emotional autonomy—combine to form the FAI. Undeniably, FAI escalates the protesting power of women and consequently escalates the efficiency of regulating IPV. Unfortunately, the absence of such a study, either at the national or international level, makes it impossible for us to cite any similar study. Good governance means an environment of peace and social justice for all. A stable society is the primal condition for economic flourishing. Improved law-and-order conditions provide an environment where goals of social and economic development are achieved simultaneously. Here, we use JPSS to comprehend the legal environment and law-and-order situation in any state and UT. An improved score means better judiciary and law-and-order conditions and is an achiever in regulating crime, including IPV. Eventually, it will be more efficient in regulating crime, including IPV (Stack et al. 2007).

Conclusion

Worldwide, one in three women experience violent behavior from a male partner in the form of psychological and/or sexual aggressiveness (Patra et al. 2018). Approximately 13–61% of women experience physical cruelty from a partner in their lifetime (World Health Organization, 2013; Patra et al. 2018). Concerning the experiences of Indian women, almost 31% of married women have experienced IPV in their married lives (Kumar et al. 2005; Kimuna et al. 2013). COVID-19 and its corresponding lockdown increased IPV across the country (Pal et al. 2021). In such scenarios, it is crucial to investigate the efficiency and factors influencing the efficacy of states’ and UTs’ efforts to limit IPV during a pandemic. This study empirically explored this topic. The empirical results showed that most of the crime-regulating instruments are operating to reduce IPV. The results obtained from the inefficiency effect models were particularly interesting. The following policies based on the empirical results are suggested to boost the efficiency of the sampled states and UTs in regulating IPV.

First, based on the beneficial effects of crime-regulating tools, such as arrests, police, and jails, we recommend expanding the size of the police force through regular recruitment of officials and other staff. Prompt arrests and quick verdicts against those accused of IPV may boost the confidence of other victims in reporting such crimes. Only by speaking out against such crimes is it possible to reduce IPV. The empirical results also predicted that an increase in female-run police stations may create an environment where female victims are comfortable reporting IPV, increasing the likelihood of initiating legal action against assailants. Overall, improved crime-regulating machinery is the primary requirement for regulating crime, including IPV. Our first recommendation is to increase the efficiency of IPV regulation.

Second, regardless of the current status of the PCNSDP, it is recommended that all Indian states and UTs improve their current PCNSDP. An increase in PCNSDP indicates that more resources are available for social security and improvement. Consequently, with higher PCNSDP, states allocate more resources to controlling crime, resulting in a lower crime rate, including IPV.

Third, the negative influences of urbanization and poverty can only be eliminated by expanding the law-and-order support system in the suburbs. Poverty can only be reduced by expanding employment and self-employment opportunities. Appropriate training is required to exploit these opportunities. The Indian government has implemented the “Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana (PMKVY)” scheme to provide proper training to rural youth to enhance their employment and self-employment opportunities in their areas of residence. This scheme was introduced to eliminate employment searches, reduce rural-to-urban migration, and boost skill development. Formal financial service providers, such as banks, need to operate appropriately to realize self-employment plans. Schemes such as PMKVY have attracted attention, particularly during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Skilled laborers always find ways to secure a livelihood.

Fourth, on January 22, 2015, the Indian government launched the “Beti Bachao Beti Padhao (Save the Daughter, Educate the Daughter)” project in recognition of the significance of a favorable sex ratio and a greater female literacy rate. The program’s goal was to improve the sex ratio through social changes. This program has helped improve the sex ratio and female literacy rate in Indian states and UTs, but there is still room for improvement.

Fifth, society and the economy have improved thanks to the increased participation of women in the political sphere. Women’s political engagement and accreditation result in a favorable societal structure by ensuring gender equality (Spary, 2007). On March 9, 2010, the Indian government announced “The Women’s Reservation Bill, or the Constitution (108th Amendment) Bill,” recognizing the significance of female political engagement and accreditation. The Act stipulates that one-third of all seats in the Lok Sabha, India’s lower house of parliament, and in the legislative assembly of a state should be reserved for women. However, to make this a reality, political well-being is necessary; otherwise, it will become a myth. If women lack the courage to speak out in favor of their fundamental liberties, reservations for certain political seats will not serve their purpose (Hassim, 2004). The government should take positive steps to encourage women to speak out about their political rights without fear or hesitation.

Sixth, here, the JPSS was used as a proxy to understand the scenario of the judiciary and public safety in India’s states and UTs. A higher score indicated an improved judiciary and public safety scenario. Such a favorable environment helps reduce crime, including IPV. Accordingly, improvements in the JPSS would increase the state’s efficiency in regulating IPV. Thus, it is highly recommended that irrespective of the present JPSS value, all Indian states and UTs take appropriate steps to improve the JPSS.

Finally, considering the positive and significant influence of FAI, it is strongly advised that governments at all levels act positively to increase the FAI score for all Indian states and UTs. Only by speaking out against and reporting crime can it be stopped.

Notably, this study’s empirical assessment relied on secondary information at the state and UT levels; thus, it involved only reported crime rates. Globally, the incidence of IPV has been underreported. The Indian scenario is much more serious. In Indian society, men are indubitably the heads of the family, and anything that occurs within the family is a private concern. Consequently, IPV is also considered a private issue between two intimate partners (Cunradi, 2010). Approximately 31% to 35% of Indian women between the ages of 15 and 49 encounter at least one kind of IPV in their lifetime (Panda and Agarwal, 2005; Krishnamoorthy et al. 2020). Although 1 in 3 Indian women experience cruelty from an intimate partner, only 1 in 10 cases are reported (Krishnamoorthy et al. 2020). Underreporting is a common phenomenon in IPV. Unfortunately, it is impossible to gather IPV information from the victims on a large scale. Thus, for any empirical study, we need to rely on secondary data. Moreover, the unavailability of micro-level data compelled us to conduct the study based on macro-level aggregate statistics. Further, panel analysis was impossible due to a lack of decadal information on several key factors, such as the female literacy rate and sex ratio. The variables included in the analysis were influenced by the availability of relevant information. This study may be expanded further to rural and urban India using panel analysis, depending on the availability of comprehensive micro-level rural and urban IPV statistics and other pertinent variable information such as women’s political accreditation and physical quality of life. Theoretically, the FRONTIER-4.1 application’s efficiency scores are susceptible to time invariance. Nevertheless, since our investigation was centered on cross-sectional data, the use of FRONTIER-4.1 had no significant repercussions.

Efficiency is a crucial concept that has broad applications in all areas of life, including crime economics. This examination of efficiency in managing IPV allowed us to pinpoint the most efficient states, as well as the factors that influence efficiency in regulating IPV. The model applied in this study is generalized and thus can be applied to any country, depending on data availability.

Data availability

Secondary information was used to perform this empirical investigation. The sources of the data are listed in Table 1. The data set in XL file is also submitted with the article.

References

American Psychological Association, Presidential Task Force on Violence, & the Family. (1996). Violence and the family: Report of the American Psychological Association presidential task force on violence and the family

Archer J (2000) Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: a meta-analytic review. Psychol. Bull. 126(5):651

Battese GE, Coelli TJ (1995) A model for technical inefficiency effects in a stochastic frontier production function for panel data. Empir. Econ. 20:325–332

Birkley EL, Eckhardt CI (2015) Anger, hostility, internalizing negative emotions, and intimate partner violence perpetration: A meta-analytic review. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 37:40–56

Bott, S, Guedes, A, Goodwin, MM and Mendoza, JA, 2012. Violence against women in Latin America and the Caribbean: A comparative analysis of population-based data from 12 countries

Bullinger LR, Carr JB, Packham A (2021) COVID-19 and crime: Effects of stay-at-home orders on domestic violence. Am. J. Health Econ. 7(3):249–280

Caetano R, Ramisetty-Mikler S, Field CA (2005) Unidirectional and bidirectional intimate partner violence among White, Black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Violence Vict. 20(4):393–406

Chattopadhyay R, Duflo E (2004) Women as policy makers: Evidence from a randomized policy experiment in India. Econometrica 72(5):1409–1443

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2016. Retrieve from: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/intimatepartnerviolence/index.html. Accessed on 12.01.2023

Coelli, TJ and Rao, DSP, O’Donnell, CJ and Battese, GE (2005). An introduction to efficiency and productivity analysis, 2

Coelli, TJ, 1996. Centre for efficiency and productivity analysis (CEPA) working papers. Department of Econometrics Universíty of New England Armidale, Australia, 1–50

Cunradi CB (2010) Neighborhoods, alcohol outlets and intimate partner violence: Addressing research gaps in explanatory mechanisms. Int. J. Environ. Res. public health 7(3):799–813

Dinnen, S, 2000. Law and order in a weak state: Crime and politics in Papua New Guinea. University of HaFAIi Press

Evans DB, Tandon A, Murray CJ, Lauer JA (2000) The comparative efficiency of national health systems in producing health: an analysis of 191 countries. World Health Organ. 29(29):1–36

Evans ML, Lindauer M, Farrell ME (2020) A pandemic within a pandemic—intimate partner violence during Covid-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 383(24):2302–2304

Farrell MJ (1957) The measurement of productive efficiency. J. R. Stat. Soc.: Ser. A (Gen.) 120(3):253–281

Ghosh J (2020) A critique of the Indian government’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Ind. Bus. Econ. 47(3):519–530

Gosangi B, Park H, Thomas R, Gujrathi R, Bay CP, Raja AS, Seltzer SE, Balcom MC, McDonald ML, Orgill DP, Harris MB (2021) Exacerbation of physical intimate partner violence during COVID-19 pandemic. Radiology 298(1):E38–E45

Gupta A, Nazrin CS (2020) Intimate partner violence - a statistical measure. Statistica Applicata - Italian. J Appl Stat 31(2):215–226. https://doi.org/10.26398/IJAS.0031-012

Hadeed LF, El-Bassel N (2006) Social support among Afro-Trinidadian women experiencing intimate partner violence. Violence women 12(8):740–760

Hassim, SAA (2004) Identities, interests and constituencies: The politics of the women’s movement in South Africa, 1980–1999

India Code (1983) Digital Repository of All Central and State Acts. Retrieve from: https://www.indiacode.nic.in/showdata?actid=AC_CEN_5_23_00037_186045_1523266765688&orderno=562. Accessed on: 11.12.2022

Iyer L, Mani A, Mishra P, Topalova P (2012) The power of political voice: women’s political representation and crime in India. Am. Economic J.: Appl. Econ. 4(4):165–193

Jeyaseelan L, Sadowski LS, Kumar S, Hassan F, Ramiro L, Vizcarra B (2004) World studies of abuse in the family environment–risk factors for physical intimate partner violence. Inj. control Saf. Promotion 11(2):117–124

Kimuna SR, Djamba YK, Ciciurkaite G, Cherukuri S (2013) Domestic violence in India: Insights from the 2005-2006 national family health survey. J. Interpers. Violence 28(4):773–807

Koenig MA, Stephenson R, Ahmed S, Jejeebhoy SJ, Campbell J (2006) Individual and contextual determinants of domestic violence in North India. Am. J. public health 96(1):132–138

Krishnamoorthy Y, Ganesh K, Vijayakumar K (2020) Physical, emotional and sexual violence faced by spouses in India: evidence on determinants and help-seeking behaviour from a nationally representative survey. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 74(9):732–740

Krug EG, Mercy JA, Dahlberg LL, Zwi AB (2002) The world report on violence and health. lancet 360(9339):1083–1088

Kumar S, Jeyaseelan L, Suresh S, Ahuja RC (2005) Domestic violence and its mental health correlates in Indian women. Br. J. Psychiatry 187(1):62–67

Kumbhakar SC, Ghosh S, McGuckin JT (1991) A generalized production frontier approach for estimating determinants of inefficiency in US dairy farms. J. Bus. Economic Stat. 9(3):279–286

Lyons M, Brewer G (2022) Experiences of Intimate Partner Violence during Lockdown and the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Fam Viol 37:969–977. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-021-00260-x

Maity S, Barlaskar UR (2022) Women’s political leadership and efficiency in reducing COVID-19 death rate: An application of technical inefficiency effects model across Indian states. Socio-Economic Plan Sci 82:101263

Maity S, Sinha A (2018) Interstate disparity in the performance of regulating crime against women in India: efficiency estimate across states. Int. J. Educ. Econ. Dev. 9(1):57–79

Maity S (2011) A study of measurement of efficiency. VDM VerlagDr. Muller GmbH & Co. KG, Germany

Maity S, Ghosh N, Barlaskar UR (2020) Interstate disparities in the performances in combatting COVID-19 in India: efficiency estimates across states. BMC Public Health 20:1–12

Moreira DN, Da Costa MP (2020) The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic in the precipitation of intimate partner violence. Int. J. Law Psychiatry 71:101606

Morris JR, Kawwass JF, Hipp HS (2023) Physical intimate partner violence among women reporting prior fertility treatment: a survey of US postpartum women. Fertil. Steril. 119(2):277–288

Morse BJ (1995) Beyond the Conflict Tactics Scale: Assessing gender differences in partner violence. Violence Vict. 10(4):251–272

Murray C, Frenk J (2001) World Health Report 2000: a step towards evidence-based health policy. Lancet 357(9269):1698–1700

National Crime Record Bureau Report. Crime in India (2021) Retrieve from: https://ncrb.gov.in/en. Accessed on: 10.08.2022

Pal A, Gondwal R, Paul S, Bohra R, Aulakh APS, Bhat A (2021) Effect of COVID-19–related lockdown on intimate partner violence in india: an online survey-based study. Violence Gend. 8(3):157–162

Panda P, Agarwal B (2005) Marital violence, human development and women’s property status in India. World Dev. 33(5):823–850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.01.009

Patra P, Prakash J, Patra B, Khanna P (2018) Intimate partner violence: Wounds are deeper. Indian J. Psychiatry 60(4):494. https://doi.org/10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_74_17

Peterman, A, Potts, A, O’Donnell, M, Thompson, K, Shah, N, Oertelt-Prigione, S and Van Gelder, N, 2020. Pandemics and violence against women and children (Vol. 528, pp. 1-45). Washington, DC: Center for Global Development

Prasad, K, 2021. Understanding the promise of communication for social change: Challenges in transforming India towards a sustainable future. Learning from Communicators in Social Change: Rethinking the Power of Development, pp.83-99

Sabri B, Renner LM, Stockman JK, Mittal M, Decker MR (2014) Risk factors for severe intimate partner violence and violence-related injuries among women in India. Women health 54(4):281–300

Schafer J, Caetano R, Clark CL (1998) Rates of intimate partner violence in the United States. Am. J. Public Health 88(11):1702–1704

Spary C (2007) Female political leadership in India. Commonw. Comp. Politics 45(3):253–277

Stack S, Cao L, Adamzyck A (2007) Crime volume and law and order culture. Justice Q. 24(2):291–308

Stevenson RE (1980) Likelihood functions for generalized stochastic frontier estimation. J. Econ. 13(1):57–66

Straus MA (1995) Trends in cultural norms and rates of partner violence: An update to 1992. Underst. Partn. Violence.: Preval., Causes, Conséq., Solut. 2:30–33

Straus MA (2005) Women’s violence toward men is a serious social problem. Curr. Controversies Fam. violence 2:55–77

Sultana A (2012) Patriarchy and Women's Subordination: A Theoretical Analysis. Arts Fac J 4:1–18. https://doi.org/10.3329/afj.v4i0.12929

United Nation., 2015. Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. General Assembly

Uthman OA, Lawoko S, Moradi T (2009) Factors associated with attitudes towards intimate partner violence against women: a comparative analysis of 17 sub-Saharan countries. BMC Int. health Hum. rights 9(1):1–15

van Gelder NE, van Rosmalen-Nooijens KAWL, A Ligthart S, Prins JB, Oertelt-Prigione S, Lagro-Janssen ALM (2020) SAFE: an eHealth intervention for women experiencing intimate partner violence–study protocol for a randomized controlled trial, process evaluation and open feasibility study. BMC Public Health 20(1):640

Vives-Cases C, La Parra-Casado D, Briones-Vozmediano E, March S, Maria Garcia-Navas A, Carrasco JM, Otero-García L, Sanz-Barbero B (2021a) Coping with intimate partner violence and the COVID-19 lockdown: The perspectives of service professionals in Spain. PloS One 16(10):e0258865

Vives-Cases C, Parra-Casado D, Estévez JF, Torrubiano-Domínguez J, Sanz-Barbero B (2021b) Intimate partner violence against women during the COVID-19 lockdown in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(9):4698. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094698

World Health Organization. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2013. Global and Regional Estimates of Violence against Women: Prevalence and Health Effects of Intimate Partner Violence and Non-Partner Sexual Violence

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge my college administrators from the bottom of my heart for their assistance. I am also thankful to “Editage” for their proofreading support in this paper. No particular grant was given to this research by any funding organisations in the public, private, or nonprofit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was conceived by S.M. Additionally, she planned, oversaw, and carried out the statistical analysis. She has gathered and put together the facts. She wrote the draught and edited the document.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors’. Thus, the author does not need any ethical approval for this article.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors’. Thus, the author does not need any ethical approval for this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Maity, S. Prevalence and determinants of intimate partner violence under a corona virus situation: technical efficiency analysis across Indian states and union territories. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1747 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04313-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04313-6