Abstract

The digital connectivity view (DCV) represents a distinct strategic framework for understanding how firms leverage interconnected digital technologies to create sustainable competitive advantages in global markets. While digital connectivity promises enhanced innovation performance, organizations face significant challenges in effectively leveraging these capabilities, with outcomes remaining highly uneven across industries. This study examines how different configurations of digital connectivity elements and organizational capabilities drive innovation performance in manufacturing firms through an integrated theoretical framework combining dynamic capabilities theory and DCV. Using fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis of 63 Chinese high-tech manufacturing firms, the research identifies multiple distinct pathways to high innovation performance. The findings reveal four key mechanisms that explain how firms effectively leverage digital connectivity, with digital-architecture resources playing a central role. Different capability configurations produce varying levels of radical and incremental innovation outcomes. The research advances innovation management literature by empirically validating configurational patterns, developing a novel theoretical framework bridging DCV with dynamic capabilities theory, and providing practical insights for manufacturing firms in emerging economies navigating global crises while maintaining innovation vitality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Digital connectivity has emerged as a transformative force in international business and innovation management, fundamentally reshaping how firms create, capture, and deliver value (Ahi et al. 2022; Nambisan and Luo 2021; Wu and Li 2024). The digital connectivity view (DCV) represents a strategic paradigm distinct from traditional digital transformation, emphasizing how firms leverage interconnected digital technologies and capabilities to create sustainable competitive advantages in global markets (Appio et al. 2021; Luo 2022). While digital transformation focuses on technological adoption and business process redesign, DCV encompasses a broader strategic perspective on how firms orchestrate their digital resources and capabilities across global networks to drive innovation (Autio et al. 2021; Ciarli et al. 2021).

Despite the promising potential of digital connectivity for enhancing innovation performance, firms face significant challenges in effectively leveraging these digital capabilities. Recent evidence suggests that innovation outcomes from digital connectivity initiatives remain highly uneven across industries (Nambisan et al. 2017; Blichfeldt and Faullant 2021). This variation in performance can be attributed to the complex interplay between digital technologies, organizational capabilities, and innovation processes (Babina et al. 2024; Rammer et al. 2022). While existing research has explored various aspects of digital globalization, there remains a critical need to understand the configurational effects of digital connectivity elements and organizational capabilities on innovation performance (Verbeke and Hutzschenreuter 2021).

Our study addresses this gap by examining how different configurations of digital connectivity elements and organizational capabilities lead to high innovation performance in manufacturing firms. We integrate the dynamic capabilities perspective with DCV to develop a comprehensive theoretical framework that explains how firms can orchestrate their digital resources and capabilities to achieve high innovation performance. Drawing on a unique dataset of 63 Chinese high-tech manufacturing firms engaged in digital globalization, we employ fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) to identify the complex combinations of factors that drive innovation success.

This research makes three contributions to the innovation management literature. First, we advance the theoretical understanding of DCV by identifying and empirically validating the configurational patterns through which digital connectivity elements and organizational capabilities interact to produce high innovation outcomes. Second, we introduce a novel theoretical framework that bridges DCV with dynamic capabilities theory, revealing four distinct mechanisms—innovation enablers, facilitators, amplifiers, and orchestrators—that explain how firms can effectively leverage digital connectivity for innovation. Third, we provide practical insights for manufacturing firms by identifying specific capability configurations that enable successful innovation in the digital age, particularly relevant for firms operating in emerging economies (Bouncken et al. 2022; Kolb et al. 2020; Liu et al. 2024).

Theoretical framework

The digital connectivity view: conceptual foundations

Building on Luo’s (2022) pioneering work, we conceptualize digital connectivity as a complex, multi-dimensional construct that transcends mere technological implementation. Unlike traditional digital transformation approaches that often focus on broad technological integration, DCV provides a nuanced examination of how intangible digital flows—encompassing data, knowledge, and digital-enabled services—generate novel innovation pathways (Appio et al. 2021; Ciarli et al. 2021). This new connectivity weakens traditional flows of investment and capital while intensifying digital forms of connectivity (Kolb 2008; Kolb et al. 2012). As digital connectivity generates growing centrifugal forces for manufacturing firms competing in a turbulent world (Autio et al. 2021; Kolb et al. 2020; Wu and Li 2024), it also necessitates organizational capabilities such as agility to support manufacturing firms’ orchestration of global digital resources.

To advance the DCV, we propose a novel integration of digital connectivity elements with dynamic capabilities theory (Teece et al. 1997; Teece 2007). This integration allows us to explore how firms not only configure digital resources but also dynamically reconfigure them in response to rapidly changing business environments. By focusing on the specific mechanisms through which digital connectivity elements interact with organizational capabilities, our study extends existing research on digital transformation and innovation (Appio et al. 2021; Blichfeldt and Faullant 2021) by providing a nuanced understanding of how these configurations lead to high innovation performance.

Digital connectivity elements

Our framework delineates three critical digital connectivity elements that collectively shape innovation potential: digital-technology resources, digital-architecture resources, and digital-intelligence capabilities.

Digital-technology resources address the technological features of digital tools enabling information processing and sharing (Luo 2022). These resources spread through organizations based on their perceived benefits, compatibility with existing systems, and ease of implementation. These digital tools include, but are not limited to, software applications, databases, cloud computing services, and communication networks, playing a critical role in reinventing innovation processes and outcomes in an increasingly digital world (Nambisan et al. 2017). By leveraging digital-technology resources, firms can enhance their operational efficiency, update technical design and services, and create value for their customers (Verbeke and Hutzschenreuter 2021).

Digital-architecture resources represent an organization’s strategic capability to optimize and integrate digital portfolios, transforming existing socio-technical structures (Nambisan et al. 2019; Luo 2022). The adoption and integration of these resources often follow patterns influenced by organizational culture, leadership, and existing technological infrastructure. Examples of digital-architecture resources include enterprise architecture frameworks, data governance policies and procedures, and application programming interfaces (APIs). These resources are characterized by transferability and modularity, which facilitate reducing complexity and increasing flexibility in the orchestration of digital resources.

Digital-intelligence capabilities refer to the cognitive layer of digital connectivity, transforming raw digital resources into actionable intelligence through advanced analytics, machine learning, and artificial intelligence (Luo 2022; Rammer et al. 2022). These capabilities evolve within organizations as they accumulate experience and knowledge, often spreading from one business unit to another as their value becomes apparent. By cultivating digital-intelligence capabilities, firms can make more informed decisions, enhance their innovation performance, and gain a competitive advantage in the digital economy (Babina et al. 2024).

Organizational capabilities as environmental enablers

Organizational-level capabilities are crucial for constructing a supportive organizational structure that aligns with the new logic of digital connectivity. These capabilities evolve over time as organizations adapt to changing technological landscapes and competitive pressures. The innovation management literature has extensively documented how supportive constituencies within the organization shape its connective activities and structure (Choudhury et al. 2021; Lanzolla et al. 2021; Luo 2022). Significantly, when digital connectivity attributes strengthen or weaken the firm’s global activities, global employees are likely to require structural modifications within the organization to foster their creativity (Liu et al. 2024). Building on the dynamic capabilities framework, we identify two critical organizational capabilities that enable effective digital connectivity: organizational agility and openness.

Organizational agility, which often develops and spreads within firms in response to environmental uncertainties, is the ability to quickly detect and respond to threats and changes, enabling faster decision-making (Giudice et al. 2021; Hund et al. 2021; Teece et al. 2016). This capability aligns closely with the sensing and seizing aspects of dynamic capabilities, allowing firms to rapidly identify and act upon opportunities arising from digital connectivity. While agility is frequently highlighted as a necessary organizational capability for many firms to survive amid increasing complexity and uncertainty (Teece et al. 2016), firms need to elaborate on their operational activities, which are driven by digital globalization (Ciampi et al. 2022; Mudambi 2008).

Organizational openness, which tends to permeate organizations gradually as they engage with diverse external partners and ideas, is a valuable capability that entails the flexibility and adaptability of firms in response to emerging ideas and technological change (Luo 2022; Ruvio et al. 2014). This capability supports the transforming aspect of dynamic capabilities, enabling firms to reconfigure their resources and processes in response to new digital opportunities and challenges. It addresses whether organizations are willing to consider digital connectivity as more than just technical connectivity and whether they are incubating new ways of innovation (Ruvio et al. 2014).

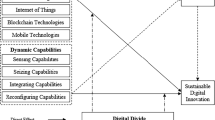

The interplay of digital connectivity elements and organizational capabilities

To deepen our understanding of how digital connectivity differs from both digital transformation and technology adoption, it’s crucial to explore the interplay among the three elements of digital connectivity and their impact on innovation performance for firms (Appio et al. 2021). We propose a novel theoretical framework that integrates dynamic capabilities theory with the digital connectivity view (Luo 2022). This integration allows us to capture the dynamic and co-evolutionary nature of digital resources, capabilities, and organizational processes in driving innovation performance. It emphasizes that elements in a system evolve together and influence each other, leading to the emergence of novel forms and functions, much like how innovations spread and interact within complex organizational ecosystems.

Firstly, digital-technology resources and digital-architecture resources interact during the innovation process (Hylving and Schultze 2020; Marion et al. 2015; Yoo et al. 2010). This interaction goes beyond simple technology adoption by contributing to firms’ sensing capabilities, allowing them to identify new technological opportunities and potential innovations (Blichfeldt and Faullant 2021). It creates new components and meaningful knowledge that can enhance innovation (Miehé et al. 2022). Nambisan et al. (2017) note that digital tools and architecture resources can generate novel pathways for innovation by creating flexible and adaptive structures.

Secondly, digital-technology resources and digital-intelligence capabilities co-occur during new technology development (Nambisan et al. 2017). This co-occurrence is particularly important in the context of artificial intelligence and machine learning, where digital intelligence actively selects and reconfigures digital resources to forecast potential opportunities (Rammer et al. 2022). This synergy can lead to more effective innovation strategies and better anticipation of market demands, enhancing firms’ seizing capabilities.

Thirdly, digital-intelligence capabilities and digital-architecture resources interact to create generative conditions for architectural innovation (Nambisan and Luo 2021). This interaction represents a key differentiator from traditional digital transformation approaches, as it supports firms’ transforming capabilities through continuous alignment of digital assets with changing business environments (Ciarli et al. 2021). For instance, customized ERP systems can influence how companies collaborate with strategic partners, fostering innovative solutions. This dynamic capabilities perspective allows us to examine how manufacturing firms develop and deploy specific capabilities to leverage their digital connectivity elements for innovation. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence into these systems enables more sophisticated forms of architectural innovation and resource orchestration (Babina et al. 2024).

In sum, extant research suggests that high innovation performance emerges from the interaction between digital-technology resources, digital-architecture resources, and digital-intelligence capabilities (Nambisan et al. 2017; Luo 2022). Our integrated theoretical framework provides a comprehensive lens through which to examine how these elements spread, interact, and evolve within manufacturing firms, ultimately shaping their innovation outcomes.

Configurational analysis and high innovation performance

Digital connectivity offers firms opportunities and benefits, but also poses significant risks (Ahi et al. 2022; Verbeke and Hutzschenreuter 2021). To be innovatively competitive in the age of digital globalization, firms must address challenges beyond just digital connectivity (Furr et al. 2022; Vial 2019). We propose a configurational approach to understand how combinations of digital connectivity elements and organizational capabilities lead to high innovation performance. This method allows us to identify multiple, equally effective pathways to innovation success (Fiss 2011; Ragin 2008).

Recent empirical evidence suggests that successful innovation requires more than mere technology adoption or digital transformation initiatives (Rammer et al. 2022). Instead, firms must carefully configure their digital resources and organizational capabilities to match their specific context and innovation objectives (Ciarli et al. 2021). Configurational analysis reveals valuable hybrid strategies, considering both digital connectivity and organizational capabilities (Fainshmidt et al. 2017). This approach advances the digital connectivity framework by explaining complex systems of relationships and accounting for complementarity and substitution between elements (Miller 1986). By investigating various pathways to high innovation performance, we can better explain the variance in firms’ strategic innovation outcomes. A conceptual foundation for firms’ innovation is presented in Fig. 1.

Methodology

Data collection

To investigate the effectiveness of digital connectivity elements and organizational capabilities in driving innovation performance, we selected Chinese high-tech manufacturing firms engaged in digital internationalization as our research samples. Our study focuses on Chinese high-tech manufacturing firms publicly listed in 2018, a critical year in the implementation of smart manufacturing policies in China. This timeframe allows for sufficient observation of firms’ responses to policy changes introduced after 2016, while providing a two-year window to measure innovation outcomes in 2020.

We employed a rigorous selection process to identify our final sample. Following the OECD/Eurostat (2018) classification of manufacturing industries, we initially identified 127 high-tech manufacturing firms active in digital internationalization. We then applied additional criteria to ensure data quality and relevance to our research questions. Specifically, we required firms to have filed patent applications during the examination period and to have complete data for all variables in our study. This process resulted in a final sample of 63 firms, with 64 firms excluded due to incomplete data (37 firms) or lack of patent applications (27 firms).

Our focus on publicly listed companies ensures data accessibility and reliability, allowing us to utilize comprehensive public information including annual reports, company disclosures, and patent applications. This approach provides a robust foundation for our analysis of digital connectivity and innovation performance in Chinese high-tech manufacturing firms. After finalizing our sample selection, we collected detailed data on these 63 firms. Table 1 provides a summary of the observations. This sample, while focused, represents a group of Chinese high-tech manufacturing firms actively engaged in both digital internationalization and innovation activities, allowing for meaningful insights into our research questions.

Measurement of causal conditions

Our study aims to evaluate the effectiveness of digital connectivity elements and organizational capabilities in enhancing innovation performance through a configurational model. Drawing on the digital connectivity framework proposed by Luo (2022), we identified five causal conditions that may influence innovation performance: digital-technology resources, digital-architecture resources, digital-intelligence capabilities, organizational agility, and organizational openness. We operationalized these conditions by outlining how each factor contributes to the performance outcome, as discussed below.

Operationalization of causal conditions

Digital-technology resources refer to the common information and digital resources firms can obtain by using digital technology. We measured this construct using a composite index based on three dimensions: (1) the degree to which the company uses information and communication technology, (2) the extent of data analytics implementation, and (3) the adoption of digital enablers (Luo 2022). Each dimension was scored on a scale from 0 to 1, based on the frequency and sophistication of related terms in the company’s annual reports and other public documents. For example, a high score in data analytics would be assigned if the company frequently mentioned and described the use of big data analytics or cloud computing in their operations.

Digital-architecture resources play a crucial role in facilitating the firm’s digital resources to be integrated and utilized optimally. We measured this construct using three dimensions: digital asset and platform portfolios, digital portfolio configurations, and digital infrastructure coordination (Luo 2022). Each dimension was scored on a scale from 0 to 1, based on the comprehensiveness and sophistication of the firm’s digital architecture as described in their public documents. For instance, a high score in digital infrastructure coordination would be assigned if the company detailed how they orchestrate various digital resources to achieve innovation goals.

Digital-intelligence capabilities refer to the process of extracting and analyzing tacit knowledge generated during the company’s daily operations, with the goal of providing novel insights for innovative decision-making. We measured this construct using three dimensions: advanced intelligence for critical decision-making, predictive and prescriptive intelligence to monitor global operations, and integrated knowledge intelligence systems (Luo 2022). Each dimension was scored on a scale from 0 to 1, based on the sophistication and extent of intelligent systems described in the company’s public documents.

Organizational capabilities are assessed using a five-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). To evaluate organizational agility, three items were selected from the original set of seven items based on their theoretical and empirical relevance across various occupations (Giudice et al. 2021). One representative item is “Your company can accommodate rapidly to market changes”. Organizational openness is also evaluated using a three-item scale adopted by Ruvio et al. (2014), with a representative item being “Your company is always moving toward the development of new answers”. These items are listed in Table 2.

Methodology for data evaluation

To address potential subjectivity in evaluating causal conditions, we employed two measures. First, we collected and organized the annual reports using the Python web scraping function (specifically, we used the ‘beautifulsoup4’ library for web scraping and ‘PyPDF2’ for PDF text extraction) and converted the text content utilizing the Java PDFbox library. Drawing from previous research by Luo (2022), Nambisan and Luo (2021), and Luo (2021), we utilized the word segmentation component of Python (specifically, the ‘jieba’ library for Chinese text segmentation) to construct the feature lexicon of digital connectivity for firms.

This study categorizes the feature lexicons of digital connectivity into three categories: digital-technology resources, digital-architecture resources, and digital-intelligence capabilities. We conducted a word frequency analysis by eliminating stop words, function words, and punctuation marks in the annual reports of the firms under investigation. The study calculates the frequency of items related to different dimensions of digital connectivity and assigns values to each measurement item.

To assess organizational capabilities, we employed a content analysis approach using annual reports, company archives, and publicly available Internet information. We developed a structured coding scheme based on a five-point Likert scale to evaluate organizational agility and openness. This approach allowed us to systematically analyze qualitative data and convert it into quantitative measures.

Specifically, we assigned four graduate students to analyze and code the data, following the approach used in previous research (Leppänen et al. 2023; Wiesche et al. 2017). Before coding, the graduate students were required to thoroughly review the relevant literature on digital connectivity. The team leader provided a detailed explanation of the coding analysis framework, scheme, and rules to ensure that all team members had a clear understanding of the coding task. Each graduate student independently coded 15 companies and then compared their results with a fellow team member who had also coded the same data.

The coders looked for evidence of organizational agility and openness, assigning scores on a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) for each of the three items measuring these capabilities. The team collectively analyzed the coding items and refined the coding approach based on their observations. Krippendorff’s alpha reliability analysis was conducted to determine the credibility of the coding, with all results above 0.8 (Krippendorff 2004), indicating strong inter-coder agreement. In cases of disagreement, a third researcher reviewed the materials and made a final determination. This rigorous coding process allowed us to quantify organizational capabilities based on firms’ public disclosures and communications.

Measurement of outcome

We measure innovation performance using the total number of successful patent applications in the t + 2 year. We chose this two-year lag based on previous innovation studies (e.g., Ahuja and Katila 2001) which suggest that the effects of organizational capabilities and resources on innovation outcomes typically manifest within a 1–3 year period. Patent grants are typically seen as a better indicator of innovation outputs because they capture the efficacy of innovation efforts (Freixanet and Rialp 2022; Liu and Qiu 2016). While we acknowledge that patents do not capture all aspects of innovation, they represent an externally validated measure of technological novelty with economic significance (Ahuja and Katila 2001). Empirical studies have shown that patents correlate well with other measures of innovative output, such as new products, innovation counts, and sales growth (Freixanet and Rialp 2022).

To evaluate the innovation performance of a firm, we distinguish between radical and incremental innovation performance based on the novelty and creativity level of the patents. This distinction aligns with the Oslo Manual’s (2018) emphasis on differentiating degrees of innovation novelty, although we recognize that our patent-based measures may not fully capture all aspects of product and process innovations as defined in the manual.

Radical innovation refers to a new patent that incorporates a fundamentally different core technology, with the newness of the knowledge component being the major criterion for this type of innovation (Chandy and Tellis 2000; Dewar and Dutton 1986; Kobarg et al. 2019). Its performance is measured by the number of successful applications for a firm’s invention patents (Freixanet and Rialp 2022). In the Chinese patent system, invention patents represent the highest level of innovation and undergo the most rigorous examination process. These patents typically represent significant technological advancements and can be considered analogous to ‘new-to-market’ innovations as described in the Oslo Manual.

Incremental innovation, on the other hand, refers to minor changes made to existing products using current technologies (Dewar and Dutton 1986; Song and Thieme 2009). Its performance is measured by the number of successful utility model patents and design patent applications filed by a company (Freixanet and Rialp 2022). In the Chinese system, utility model patents protect technical solutions relating to the shape or structure of a product, while design patents protect new designs of a product’s shape, pattern, or color. Both typically represent more incremental innovations compared to invention patents. These patents often align with the Oslo Manual’s concept of ‘new-to-firm’ innovations or incremental process improvements. The patent filing data are downloaded from the State Intellectual Property Office of China (SIPO). Table 3 displays the means, standard deviations, and correlations of the scores for all variables in the analysis.

Calibration

The calibration of all conditions and outcomes into set membership, which precedes a fuzzy set analysis, is crucial (Ragin 2000). The degree of set membership in each causal and outcome condition utilized in the study is determined by the researcher using three thresholds. The membership ratings range from 0 to 1, where 0 denotes full non-membership, 1 represents full membership, and values between 0 and 1 represent a fuzzy set. To assess the degree of set membership of the conditions and outcomes, calibration should be based on substantive and theoretical knowledge to define meaningful thresholds (Misangyi et al. 2017; Ragin 2008). However, in cases where there is little to no theoretical or substantial understanding regarding relevant thresholds that apply to strategically complex phenomena, scales, and other comparable measurement tools can offer useful assistance in calibrating (Leppänen et al. 2023; Misangyi et al. 2017).

We calibrated all three digital connectivity constituents and the two kinds of organizational capabilities based on the scales used in the data collection. The minimum and maximum aggregated values of the separate constructs rarely approached the theoretical endpoints because all of these constructs contained three items, each of which was evaluated along a Likert scale ranging from 0 to 1 or 1 to 5. Therefore, we set the thresholds at 0.75 (fully in), 0.50 (crossover point), and 0.25 (fully out) when the scale was 0–1. Similarly, we chose to calibrate organizational capabilities by defining full membership as an average score of 4 and non-membership as an average score of 2, using 3 as the crossover point.

For the calibration of our outcome condition, innovation performance, we used the fuzzy set membership scores. Due to a lack of theoretical knowledge of thresholds for firms’ innovation performance, we turned to the SIPO and compiled a dataset containing the total number of manufacturing firms’ patents between 2019 and 2020. Like prior studies that use fsQCA (e.g., Fiss 2011; Jacqueminet and Durand 2020; Leppänen et al. 2023; Misangyi and Acharya 2014), we sought to use the population-level mean to distinguish between fully in and fully out. For radical innovation, we set the calibration thresholds to the mean (9.6), which refers to the “crossover point”, and the prevailing convention of above the mean value (17.5), which refers to “fully in” and is close to the 90th percentile at the population level. In addition, we set the lower threshold at 5.3, which refers to “fully out” and close to the 75th percentile at the population level. For incremental innovation, we set the calibration thresholds to the mean (42.3), which refers to the “crossover point”, and the prevailing convention of above the mean value (78.6), which refers to “fully in” and is close to the 90th percentile at the population level. In addition, we set the lower threshold at 13.8, which refers to “fully out” and is close to the 75th percentile at the population level. Table 4 presents the calibration thresholds.

Analysis

After calibrating the data, we evaluated the necessity of each condition using the fsQCA 3.0 software. A necessary condition must be present for the outcome to occur (Ragin 2008). To analyze necessary conditions, we used a consistency score with the procedures of fsQCA, which reflects how much the condition is a superset of the outcome. If a condition’s consistency score is more than 0.9, it is considered necessary (Schneider et al. 2010). As shown in Table 5, none of the individual factors exceeds the consistency threshold of 0.90 for the necessary conditions using fsQCA (Schneider and Wagemann 2012).

Next, we adopted the fsQCA methodology to analyze the causal conditions that influence innovation performance in firms. Following Fiss (2011), our approach consists of three steps. First, we construct a truth table that lists every theoretically possible combination of the causal conditions that were employed in the analysis (Ragin 2000). Second, consistency and frequency thresholds are included as two additional thresholds for the analysis. In accordance with earlier studies, we set the consistency at 0.80, higher than the recommended value of 0.75, and utilize a minimal proportional reduction in consistency (PRI consistency) threshold of 0.75 (Ragin 2008; Fiss 2011; Misangyi and Acharya 2014; Jacqueminet and Durand 2020). We chose these thresholds to ensure robust results while maintaining a balance between parsimony and explanatory power. The frequency threshold is set at a minimum of two cases per configuration. Third, a counterfactual analysis is introduced to simplify the assumptions.

Results and discussion

Configurations leading to high innovation performance

The necessity and sufficiency analyses indicate that no individual elements of digital connectivity and organizational capabilities can produce high innovation performance. Instead, specific configurations of these elements provide a better explanation for the variance in a firm’s innovation outcomes. Five configurations for high innovation performance have been identified, and the results of the fsQCA are presented in Table 6. Each column in the table represents a solution corresponding to the high innovation performance of manufacturing firms, with each configuration exhibiting consistencies greater than the standard threshold of 0.8. We have identified two configurations for firms’ radical innovation and three configurations for firms’ incremental innovation.

Configurations leading to high radical innovation performance

As shown in Table 6, configurations C1a and C1b correspond to high radical innovation in firms. Both configurations C1a and C1b show clear consistency among constituents of digital connectivity. Indeed, they include the presence of digital-technology resources as a core condition and of digital-architecture resources as a peripheral condition.

The presence of digital-technology resources as a core condition in both configurations suggests that these resources provide the fundamental tools necessary for radical innovation. When combined with digital-architecture resources, they create a technological foundation that enables firms to reimagine their processes and products. This combination facilitates the development of novel solutions and drives revolutionary changes in business models.

Achieving high radical innovation performance requires organizational capabilities to support digital resource orchestration activities, particularly organizational openness, which appears as a core condition in both configurations. Organizational openness allows firms to leverage these digital resources effectively by facilitating knowledge exchange and collaboration across organizational boundaries, which is crucial for generating novel ideas and solutions.

The key distinction between C1a and C1b lies in the role of organizational agility and digital-intelligence capabilities. Configuration C1a is characterized by the absence of organizational agility and digital-intelligence capabilities, suggesting that firms can achieve high radical innovation performance primarily through the combination of digital resources and organizational openness. In contrast, C1b includes organizational agility as a peripheral condition and digital-intelligence capabilities as a contributing factor. This difference implies that while both configurations can lead to radical innovation, C1b represents a more holistic approach that leverages a wider range of organizational and digital resources.

Configuration C1a is exemplified by a digitally transformed home appliance company. This company has recently emphasized digital-technology and architecture-driven connectivity, integrating digital technology into its business operations to revolutionize the traditional communication model. Furthermore, the company has developed an industrial Internet platform through the integration of existing digital resources, facilitating the development of radical innovation. In this configuration, high radical innovation performance seems to be primarily driven by digital-technology and digital-architecture resources, along with organizational openness, despite limited organizational agility.

Configuration C1b is exemplified by an electronic equipment company that aims to establish a global connection mode with intelligent technologies and scenarios at its core. The company has constructed a more efficient intelligent logistics system and promoted operational innovation across the entire supply chain. In C1b, organizational agility is present as a peripheral condition, suggesting that the ability to quickly respond to market changes complements the digital connectivity elements, enhancing the firm’s capacity for radical innovation. Additionally, the peripheral presence of digital-intelligence capabilities indicates that data-driven insights can further amplify the innovative potential of the digital infrastructure and organizational openness.

When comparing these configurations to existing literature, our findings align with previous studies highlighting the importance of digital technologies and organizational openness in fostering radical innovation (e.g., Blichfeldt and Faullant 2021; Nambisan et al. 2017). However, our results extend this understanding by demonstrating that firms can achieve radical innovation through different combinations of these elements, with varying degrees of organizational agility and digital intelligence involvement.

Configurations leading to high incremental innovation performance

C2a, C2b, and C2c are three paths that lead to high incremental innovation performance. Across all three configurations, digital-architecture resources and organizational agility emerge as core conditions, underscoring their critical role in incremental innovation. Digital-architecture resources likely facilitate the integration and optimization of existing processes, while organizational agility enables firms to rapidly implement incremental changes based on market feedback or internal insights.

A comparative analysis of these configurations reveals interesting patterns. Configuration C2a, which has the highest coverage of 31% (including unique coverage of 19%), relies solely on digital-architecture resources and organizational agility as its core conditions. Notably, it is characterized by the absence of digital-technology resources and digital-intelligence capabilities as peripheral conditions. This suggests that for some firms, a streamlined approach focusing on agile organizational structures and robust digital architectures may be sufficient for incremental innovation.

In contrast, Configuration C2b demonstrates a more comprehensive approach, incorporating all three elements of digital connectivity along with organizational agility. This configuration suggests that some firms benefit from a full spectrum of digital resources when pursuing incremental innovation. Interestingly, organizational openness is an irrelevant condition in this configuration, which diverges from its importance in radical innovation configurations.

Configuration C2b is exemplified by a manufacturing company operating in computer software. With an agile mindset, this enterprise uses the digital tools provided by the digital platform to quickly establish a network with other platform participants and obtain increasing market information through intelligence. The peripheral presence of digital-intelligence capabilities suggests that data-driven insights can enhance incremental innovation by providing a deeper understanding of customer needs and market trends, which allows for more targeted improvements.

Configuration C2c presents a middle ground between C2a and C2b. It maintains digital-architecture resources and organizational agility as core conditions but includes digital-technology resources as a peripheral condition. This configuration suggests that while some firms can achieve incremental innovation without heavily relying on digital technologies (as in C2a), others find value in incorporating these resources to complement their digital architecture and agile practices. A company that produces smart hardware, such as smart wearables, serves as an example of this configuration. This company uses social media platforms built with digital technology to generate, capture, apply, and analyze data, enabling more sophisticated global consumer-business connections. The combination of digital-architecture resources and organizational agility allows the company to capture changes in consumer needs more quickly and make incremental innovations to facilitate technological upgrades.

Configurations leading to low innovation performance

As shown in Table 7, our analysis uncovered four configurations that may contribute to the manufacturing firms’ low innovation performance. These configurations illustrate that the causal conditions that support the presence of high innovation performance are not necessarily the exact inverse of those that lead to low innovation performance, as suggested by the assumption of causal asymmetry. Following that, we briefly outline the configurations that contribute to low innovation performance.

Configurations F1a and F1b are associated with the manufacturing firms’ low radical innovation performance. These two configurations correspond to organizational capabilities that are not extensively adopted by firms, as indicated by the absence of organizational agility or openness as a core condition. Each configuration reflects a state of inconsistency in digital connectivity elements, where one of the connectivity constituents is absent (i.e., digital-intelligence capabilities in configurations F1a and F1b), while the other two are either present or insignificant.

Configurations F2a and F2b are two configurations that lead to low incremental innovation performance in manufacturing firms. Specifically, F2a reflects a situation where firms have a low degree of digital resource conversion, as digital-technology resources are an irrelevant condition, and the support of organizational capabilities are not present as a core condition. Furthermore, F2b indicates that the absence of digital-technology and digital-architecture resources in the configuration, combined with the lack of organizational capabilities, sufficiently prevents manufacturing firms from achieving high incremental innovation performance.

Robustness tests

To ensure the robustness of our findings, we conducted several additional checks following the recommendations of Fiss (2011). Specifically, we performed several fsQCA-specific analyses using different specifications of causal elements. First, we conducted the same analysis with different calibration anchor points for the set membership. The outcomes remained essentially the same in terms of quality in the number of configurations and the pattern of solutions, and the interpretation of our findings remained largely unaltered. Second, we repeated the analysis with lower and higher consistency thresholds. As expected, the number of configurations in the final solution changed, but the main conclusions were consistent.

Conclusion

The objective of this research was to advance the digital connectivity view by deepening our understanding of how digital connectivity influences innovation activities. We propose a novel integration of digital connectivity elements with dynamic capabilities theory as our theoretical framework. Adopting a configurational approach for holistic analysis, we conceptualized digital connectivity as a blend of digital-technology resources, digital-architecture resources, and digital-intelligence capabilities, alongside organizational capabilities. Our research identified non-symmetrical and diverse configurations of these elements that drive high and low innovation performance. This integration elucidates the mechanisms through which specific configurations of digital connectivity elements and organizational capabilities influence innovation outcomes.

Our findings reveal several key mechanisms underlying the relationship between digital connectivity configurations and innovation performance. First, digital-technology resources function as innovation enablers. While these resources alone are insufficient for driving innovation, they provide the necessary foundation upon which firms can build their innovative capabilities. In radical innovation configurations, digital-technology resources emerge as a core condition, suggesting a critical role in enabling breakthrough innovations.

Second, digital-architecture resources act as innovation facilitators. These resources play a crucial role in both radical and incremental innovation configurations by enhancing resource utilization efficiency and reducing coordination issues. Digital-architecture resources provide the structural backbone that allows firms to effectively deploy and reconfigure their digital-technology resources in response to changing innovation needs.

Third, digital-intelligence capabilities serve as innovation amplifiers. In configurations where these capabilities are present, they enhance a firm’s ability to identify innovation opportunities, understand market trends, and make informed decisions about product and process improvements. This amplification effect is particularly evident in incremental innovation configurations, where digital-intelligence capabilities contribute to more targeted and effective improvements.

Lastly, organizational capabilities function as innovation orchestrators. Organizational openness and agility enable firms to effectively leverage their digital resources and capabilities for innovation. Organizational openness is crucial for radical innovation, facilitating knowledge exchange and collaboration across organizational boundaries. This openness allows firms to combine diverse ideas and resources in novel ways, supporting the development of breakthrough innovations. Conversely, organizational agility is critical for both radical and incremental innovation, enabling firms to quickly respond to market changes and implement innovations.

Theoretical contributions

Our study makes several significant theoretical contributions to the understanding of digital connectivity and innovation management. First, we advance the digital connectivity view by conceptually distinguishing it from broader digital transformation processes. While digital transformation encompasses holistic organizational change driven by digital technologies (Appio et al. 2021), DCV specifically focuses on how the orchestration of digital resources and capabilities creates value through connectivity. By employing a configurational approach, we demonstrate that digital connectivity represents a distinct theoretical construct that explains how firms leverage digital resources and capabilities to achieve specific innovation outcomes, rather than merely describing the process of digital adoption or transformation.

Our second contribution lies in developing an integrated theoretical framework that bridges DCV with dynamic capabilities theory (Chang et al. 2012; Henfridsson et al. 2018; Nambisan et al. 2017; Luo 2022). This integration reveals four crucial mechanisms through which digital connectivity elements interact with organizational capabilities to drive innovation. Digital-technology resources function as innovation enablers, providing the technological foundation particularly crucial for radical innovation. Digital-architecture resources serve as innovation facilitators, enhancing resource utilization efficiency and reducing coordination issues in both radical and incremental innovation. Digital-intelligence capabilities act as innovation amplifiers, leveraging artificial intelligence and data analytics to identify opportunities and inform decision-making (Rammer et al. 2022; Babina et al. 2024). Finally, organizational capabilities operate as innovation orchestrators, with openness and agility enabling firms to effectively leverage their digital resources for different types of innovation.

Third, we contribute to the manufacturing firm literature by addressing a critical gap in understanding how digital technologies influence innovation performance (Monaghan et al. 2020; Freixanet and Rialp 2022; Bhandari et al. 2023). Our findings reveal that the relationship between digital technologies and innovation in manufacturing firms is more nuanced than previously theorized. Specifically, we show that different configurations of digital connectivity elements and organizational capabilities can lead to equivalent innovation outcomes, challenging the notion of universal best practices in digital innovation management. This equifinality suggests that manufacturing firms can achieve innovation success through multiple pathways, depending on their specific context and capabilities.

Finally, by situating our study in the Chinese manufacturing context, we extend the theoretical generalizability of DCV across institutional contexts. The dynamic capabilities perspective on digital connectivity in emerging markets reveals unique patterns of resource orchestration that differ from developed market contexts. Our findings suggest that Chinese manufacturing firms’ innovation outcomes depend not just on their digital resource endowments, but on their ability to configure these resources in ways that align with their organizational capabilities and institutional environment. This insight contributes to both the digital innovation literature and the emerging market strategy literature by highlighting the contextual nature of digital resource deployment in innovation processes (Ciarli et al. 2021; Blichfeldt and Faullant 2021).

Managerial implications

Our study offers several managerial implications, particularly for managers of Chinese manufacturing firms. Foremost among these implications is the imperative for managers to adopt a holistic, configurational approach to innovation. Rather than developing individual elements in isolation, executives should focus on creating synergistic combinations of digital resources and organizational capabilities. This approach entails tailoring digital strategies to specific innovation objectives; for instance, radical innovation necessitates a focus on digital-technology resources complemented by organizational openness and agility, while incremental innovation calls for an emphasis on digital-architecture resources and digital-intelligence capabilities, underpinned by organizational agility.

Furthermore, our findings underscore the critical importance of investing in foundational digital architecture and key organizational capabilities. Managers should prioritize the development of scalable and flexible digital infrastructures that can serve as robust platforms for integrating various digital technologies. Concurrently, firms must cultivate crucial organizational capabilities, including absorptive capacity, agility, and orchestration capability. These investments not only create a solid foundation for leveraging digital connectivity across diverse innovation activities but also enable firms to adapt swiftly to the ever-changing technological landscape.

Lastly, our research highlights the necessity of implementing dynamic and context-aware innovation strategies. In today’s rapidly evolving digital environment, static approaches to innovation are inadequate. Instead, managers must establish mechanisms for continually reassessing and reconfiguring their digital connectivity elements and organizational capabilities. This is particularly crucial for firms in emerging markets, which can leverage digital connectivity to overcome resource constraints and compete on a global scale. However, executives must remain vigilant of potential challenges inherent in this approach, such as data security risks and the ongoing need for workforce upskilling. By embracing this dynamic strategy, firms can maintain their innovative edge and thrive in the face of relentless technological change.

Limitations and future research

This study has several limitations, which present opportunities for further research. First, while the use of fsQCA is appropriate for exploring complex causal configurations and identifying different pathways that lead to firm innovation, it is essential to acknowledge the method’s inherent constraints in establishing direct causal effects. FsQCA operates within a set-theoretic framework, emphasizing the association and interplay of conditions rather than isolating causal impacts in the traditional statistical sense (Ragin 2008). As such, our findings should be interpreted with caution, as they indicate associative patterns rather than definitive causal mechanisms. To enhance causal inference, future research could employ complementary approaches, such as longitudinal panel data analysis or structural equation modeling, to strengthen the evidence of causality and clarify temporal dynamics.

Second, the generalizability of our findings may be limited by the relatively small and non-random nature of our sample. Although our data provide valuable insights, they do not represent a wide range of industries or contexts, which might restrict the applicability of the results. Future research should aim to overcome this limitation by using larger, more diverse, and randomly selected samples. Such studies could improve the robustness and external validity of the findings. Additionally, incorporating mixed methods, such as combining quantitative data with qualitative insights from case studies or interviews, could yield a more comprehensive understanding of how digital connectivity influences innovation in varying organizational and environmental settings.

Third, our measurement approach, which relies on content analysis and archival data, may not fully align with established standards for assessing innovation performance, such as those outlined in the Oslo Manual (OECD/Eurostat 2018). The reliance on subjective assessments introduces the risk of measurement bias and may not entirely capture the nuances of firms’ innovation activities. Future research could address this limitation by developing more objective and standardized measures, potentially incorporating innovation survey data or direct assessments from managers regarding innovation outcomes. This would provide more reliable and precise indicators of digital connectivity and innovation performance, thereby enhancing the study’s methodological rigor and relevance.

Data availability

Replication data for the current study is available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/LDZHPO.

References

Ahi AA, Sinkovics N, Shildibekov Y, Sinkovics RR, Mehandjiev N (2022) Advanced technologies and international business: a multidisciplinary analysis of the literature. Int Bus Rev 31(4):101967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2021.101967

Ahuja G, Katila R (2001) Technological acquisitions and the innovation performance of acquiring firms: a longitudinal study. Strateg Manag J 22(3):197–220. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.157

Appio FP, Frattini F, Petruzzelli AM, Neirotti P (2021) Digital transformation and innovation management: a synthesis of existing research and an agenda for future studies. J Prod Innov Manag 38(1):4–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12562

Autio E, Mudambi R, Yoo Y (2021) Digitalization and globalization in a turbulent world: Centrifugal and centripetal forces. Glo Strateg J 11(1):3–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/gsj.1396

Babina T, Fedyk A, He A, Hodson J (2024) Artificial intelligence, firm growth, and product innovation. J Financ Econ 151:103745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2023.103745

Bhandari KR, Zámborský P, Ranta M, Salo J (2023) Digitalization, internationalization, and firm performance: a resource-orchestration perspective on new OLI advantages. Int Bus Rev 32(4):102135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2023.102135

Blichfeldt H, Faullant R (2021) Performance effects of digital technology adoption and product & service innovation: a process-industry perspective. Technovation 105:102275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2021.102275

Bouncken RB, Fredrich V, Sinkovics N, Sinkovics RR (2022) Digitalization of cross‐border R&D alliances: Configurational insights and cognitive digitalization biases. Glo Strateg J 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/gsj.1469

Chandy RK, Tellis GJ (2000) The incumbent’s curse? Incumbency, size, and radical product innovation. J Mark 64(3):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.64.3.1.18033

Chang YC, Chang HT, Chi HR, Chen MH, Deng LL (2012) How do established firms improve radical innovation performance? The organizational capabilities view. Technovation 32(7-8):441–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2012.03.001

Choudhury P, Foroughi C, Larson B (2021) Work-from-anywhere: the productivity effects of geographic flexibility. Strateg Manag J 42(4):655–683. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3251

Ciampi F, Faraoni M, Ballerini J, Meli F (2022) The co-evolutionary relationship between digitalization and organizational agility: ongoing debates, theoretical developments and future research perspectives. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 176:121383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121383

Ciarli T, Kenney M, Massini S, Piscitello L (2021) Digital technologies, innovation, and skills: emerging trajectories and challenges. Res Policy 50(7):104289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2021.104289

Dewar RD, Dutton JE (1986) The adoption of radical and incremental innovations: an empirical analysis. Manag Sci 32(11):1422–1433. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.32.11.1422

Fainshmidt S, Nair A, Mallon M (2017) MNE performance during a crisis: an evolutionary perspective on the role of dynamic managerial capabilities and industry context. Int Bus Rev 26(6):1088–1099. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IBUSREV.2017.04.002

Fiss PC (2011) Building better causal theories: a fuzzy set approach to typologies in organization research. Acad of Manage J 54(2):393–420. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.60263120

Freixanet J, Rialp J (2022) Disentangling the relationship between internationalization, incremental and radical innovation, and firm performance. Glo Strateg J 12(1):57–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/gsj.1412

Furr N, Ozcan P, Eisenhardt KM (2022) What is digital transformation? Core tensions facing established companies on the global stage. Glo Strateg J 12(4):595–618. https://doi.org/10.1002/gsj.1442

Giudice MD, Scuotto V, Papa A, Tarba SY, Bresciani S, Warkentin M (2021) A self‐tuning model for smart manufacturing SMEs: effects on digital innovation. J Prod Innov Manage 38(1):68–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12560

Henfridsson O, Nandhakumar J, Scarbrough H, Panourgias N (2018) Recombination in the open-ended value landscape of digital innovation. Inf Organ 28(2):89–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2018.03.001

Hund A, Wagner HT, Beimborn D, Weitzel T (2021) Digital innovation: review and novel perspective. J Strateg Inf Syst 30(4):101695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2021.101695

Hylving L, Schultze U (2020) Accomplishing the layered modular architecture in digital innovation: the case of the car’s driver information module. J Strateg Inf Syst 29(3):101621. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2020.101621

Jacqueminet A, Durand R (2020) Ups and downs: the role of legitimacy judgment cues in practice implementation. Acad of Manage J 63(5):1485–1507. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2017.0563

Kobarg S, Stumpf-Wollersheim J, Welpe IM (2019) More is not always better: effects of collaboration breadth and depth on radical and incremental innovation performance at the project level. Res Policy 48(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.RESPOL.2018.07.014

Kolb DG (2008) Exploring the metaphor of connectivity: attributes, dimensions and duality. Organ Stud 29(1):127–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607084574

Kolb DG, Caza A, Collins PD (2012) States of connectivity: new questions and new directions. Organ Stud 33(2):267–273. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840611431653

Kolb DG, Dery K, Huysman M, Metiu A (2020) Connectivity in and around organizations: waves, tensions and trade-offs. Organ Stud 41(12):1589–1599. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840620973666

Krippendorff K (2004) Reliability in content analysis: some common misconceptions and recommendations. Hum Commun Res 30(3):411–433. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1468-2958.2004.TB00738.X

Lanzolla G, Pesce D, Tucci CL (2021) The digital transformation of search and recombination in the innovation function: tensions and an integrative framework. J Prod Innov Manag 38(1):90–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12546

Leppänen P, George G, Alexy (2023) When do novel business models lead to high performance? A configurational approach to value drivers, competitive strategy, and firm environment. Acad of Manage J 66(1):164–194. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2020.0969

Liu L, Cui L, Han Q, Zhang C (2024) The impact of digital capabilities and dynamic capabilities on business model innovation: the moderating effect of organizational inertia. Hum Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-02910-z

Liu Q, Qiu LD (2016) Intermediate input imports and innovations: evidence from Chinese firms’ patent filings. J Int Econ 103:166–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JINTECO.2016.09.009

Luo Y (2021) New OLI advantages in digital globalization. Int Bus Rev 30(2):101797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2021.101797

Luo Y (2022) New connectivity in the fragmented world. J Int Bus Stud 53:962–980. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-022-00530-w

Marion TJ, Meyer MH, Barczak G (2015) The influence of digital design and IT on modular product architecture. J Prod Innov Manag 32(1):98–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12240

Miehé L, Palmié M, Oghazi P (2022) Connection successfully established: How complementors use connectivity technologies to join existing ecosystems – four archetype strategies from the mobility sector. Technovation 102660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2022.102660

Miller D (1986) Configurations of strategy and structure: towards a synthesis. Strateg Manage J 7:233–249

Misangyi VF, Acharya AG (2014) Substitutes or complements? A configurational examination of corporate governance mechanisms. Acad Manage J 57(6):1681–1705. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2012.0728

Misangyi VF, Greckhamer T, Furnari S, Fiss PC, Crilly D, Aguilera R (2017) Embracing causal complexity: the emergence of a neo-configurational perspective. J Manag 43(1):255–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316679252

Monaghan S, Tippmann E, Coviello N (2020) Born digitals: thoughts on their internationalization and a research agenda. J Int Bus Stud 51(1):11–22. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-019-00290-0

Mudambi R (2008) Location, control and innovation in knowledge-intensive industries. J Econ Geogr 8(5):699–725. https://doi.org/10.1093/JEG/LBN024

Nambisan S, Luo Y (2021) Toward a loose coupling view of digital globalization. J Int Bus Stud 52(8):1646–1663. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-021-00446-x

Nambisan S, Lyytinen K, Majchrzak A, Song M (2017) Digital innovation management: reinventing innovation management research in a digital world. MIS Quart 41(1):223–238. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2017/41:1.03

Nambisan S, Zahra SA, Luo Y (2019) Global platforms and ecosystems: implications for international business theories. J Int Bus Stud 50(9):1464–1486. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41267-019-00262-4

OECD/Eurostat (2018) Oslo Manual 2018: guidelines for collecting, reporting, and using data on innovation: the measurement of scientific, technological and innovation activities. Luxembourg: OECD Publishing, Paris: Eurostat

Ragin CC (2000) Fuzzy set social science. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Ragin CC (2008) Redesigning social inquiry: Fuzzy sets and beyond. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Rammer C, Fernández GP, Czarnitzki D (2022) Artificial intelligence and industrial innovation: evidence from German firm-level data. Res Policy 51(7):104555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2022.104555

Ruvio AA, Shoham A, Vigoda‐Gadot E, Schwabsky N (2014) Organizational innovativeness: construct development and cross‐cultural validation. J Prod Innov Manage 31(5):1004–1022. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12141

Schneider CQ, Wagemann C (2012) Set-theoretic methods for the social sciences: a guide to qualitative comparative analysis. Cambridge University Press, New York

Schneider MR, Schulze-Bentrop C, Paunescu M (2010) Mapping the institutional capital of hightech firms: a fuzzy-set analysis of capitalist variety and export performance. J Int Bus Stud 41:246–266. https://doi.org/10.1057/JIBS.2009.36

Song M, Thieme J (2009) The role of suppliers in market intelligence gathering for radical and incremental innovation. J Prod Innov Manag 26(1):43–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1540-5885.2009.00333.X

Teece D, Peteraf M, Leih S (2016) Dynamic capabilities and organizational agility: risk, uncertainty, and strategy in the innovation economy. Calif Manage Rev 58(4):13–35. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2016.58.4.13

Teece DJ (2007) Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg Manage J 28(13):1319–1350. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.640

Teece DJ, Pisano G, Shuen A (1997) Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg Manage J 18(7):509–533

Verbeke A, Hutzschenreuter T (2021) The dark side of digital globalization. Acad Manage Perspect 35(4):606–621. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2020.0015

Vial G (2019) Understanding digital transformation: a review and a research agenda. J Strateg Inf Syst 28(2):118–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsis.2019.01.003

Wiesche M, Jurisch MC, Yetton PW, Krcmar H (2017) Grounded theory methodology in information systems research. MIS Quart 41(3):685–701. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2017/41.3.02

Wu Y, Li Z (2024) Digital transformation, entrepreneurship, and disruptive innovation: evidence of corporate digitalization in China from 2010 to 2021. Hum Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02378-3

Yoo Y, Henfridsson O, Lyytinen K (2010) Research commentary —the new organizing logic of digital innovation: an agenda for information systems research. Inform Syst Res 21(4):724–735. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1100.0322

Acknowledgements

This article is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 72342029; 72091314; 72032008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Cong Cheng: conceptualization, project administration, recourses, supervision, writing—review & editing. Zefeng Miao: data curation, methodology, empirical analysis and results, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, C., Miao, Z. Leveraging digital connectivity for innovation performance: a fsQCA study on Chinese high-tech manufacturing firms. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 58 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04372-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04372-3