Abstract

Farmers view the forced expropriation of land during urban expansion as a harmful influence. This study aims to investigate how peri-urban farmers perceive being evicted due to urban expansion, focusing on land valuation process, compensation amount, and livelihood improvement. These factors are taken as latent variables for analysis together with 11 other indicators. The research was carried out in Injibara, Burie, and Gish Abay towns in the Amhara region of Ethiopia. Data was collected from 197 evicted households through random selection. Data analysis utilized partial least square-structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). The results demonstrate that the amount of compensation and the land valuation process positively and significantly impact the livelihoods of evicted farmers. Specifically, land valuation has a direct, indirect, and total effect on livelihood improvement by 30.65%, 5.2%, and 35.8%, respectively. Furthermore, compensation has a direct impact of 27.7% and acts as a mediating variable between valuation and livelihood improvement. This depicts that the land valuation process has a more substantial effect on improving household livelihoods compared to compensation. The study suggests that addressing farmers’ perceptions of land eviction involves improving the livelihoods of evicted households. This could be achieved by making the land valuation process participatory, considering the land’s location, enhancing the skill of land valuation professionals, reducing corruption, prioritizing employment for evicted households, and ensuring timely compensation payments while considering inflation expectations. In conclusion, this research highlights the importance of conducting thorough socioeconomic assessments before evicting peri-urban farmers, as overlooking their perceptions towards land eviction could lead to community discord.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urbanization has emerged as a key indicator of a nation’s economic progress. Recently, there has been a notable surge in the urbanization rate of less developed countries, especially in Africa, leading to the forceful displacement of farmers from agricultural lands in peri-urban areas. This pattern of land eviction has significant repercussions on the sustainability of livelihoods, extending across economic, social, and cultural dimensions (Alamneh et al. 2023b; Mohammed et al. 2020; Kosa et al. 2017).

First, the economic impact can be observed through the annual income generated by the agricultural sector. Studies by Gebeyehu et al. (2022) and Alamneh et al., (2023a) have shown that evicted farmers experience a decline in their mean annual income and per capita consumption expenditure compared with non-evicted households with similar socioeconomic backgrounds. This is due to the fact that farmers lose their productive asset (land), lack of employment opportunities in the urbanities, lack of competitive skill in transitioning to non-agricultural works, and allocation of compensation in non-productive assets instead of income-generating activities because they lack financial administration capabilities when a lump-sum of money is given at a time in the form of compensation (Alamneh et al. 2023a; Endris et al. 2021).

Furthermore, sustainable urban development is contingent upon the cultivation of a sense of “belongingness”. A lack of belongingness to specific projects can pose a challenge to their sustainability. Sustainability requires actively involving evicted farmers and giving them the tools they need to support development goals. Projects can have a long-lasting effect by encouraging social cohesiveness and community involvement through programs that foster strong relationships and ownership. By encouraging resilience, community ownership, and behavioral change through a sense of belonging, stakeholders play a critical role in improving programs (du Toit-Brits, 2022; Holland, 2017; Arnstein, 2017; Chambers, 1994; Weldearegay et al. 2021). This can be addressed by promoting the positive perception of evicted farmers towards land eviction because farmers’ perceptions of land expropriation due to urban expansion significantly shape their views on property rights, livelihoods, and community relations. Addressing these concerns through inclusive planning processes is crucial to prevent conflicts. Stakeholder involvement in decision-making, trust-building between farmers and urban planners, and effective communication are key to avoid conflict for successful urban development initiatives.

Eviction of farmland is a common practice in many nations, particularly in emerging economies like Ethiopia, where farmers’ agricultural lands are often replaced by residential areas, industrial zones, and infrastructure. However, the perceptions of farmers displaced by urban expansion and development projects remains overlooked, particularly their perceptions towards land eviction are under-researched and lack considerable empirical evidence. Although there are a limited number of research in this arena, most of them are focusing on the economic impacts of urban expansion on evicted peri-urban farmers (Gebeyehu et al. 2022; Mohammed et al. 2020), while neglecting a comprehensive understanding of the farmers perception towards land eviction spectacles.

The effects of land eviction extend beyond economic concerns while it includes psychological traits, such as farmers perception which can be seen as markers of social status and prestige for farmers. However, the perception of evicted farmers on land eviction is often overlooked. Hence, there is a lack of empirical evidence on how displaced farmers perceive land eviction resulting from urban expansion and development projects. This created a knowledge gap among various stakeholders. The narrow focus of this limited scope may have adverse effects on urban development plans and has the potential to result in social and political turmoil during and/or after eviction. Therefore, it is essential to address the perspectives of displaced farmers concerning eviction, compensation policies, and their participation in the valuation process through conducting empirical research to make knowledge-based decisions. However, the track record of Ethiopian cities in this arena is poor so far. Hence, there is a dearth of substantial empirical evidence on how evicted farmers perceive land eviction resulting from urban expansion and development undertakings. It is, therefore vital to comprehend the perception of evicted farmers towards land eviction, compensation policies, and their involvement in the valuation process. Finally, the contribution of this research is to add empirical evidence to the existing body of literature by bridging the prevailing knowledge gap in academia, and the findings will offer practical guidance to municipality administrators involved in urban development, providing insights for policy makers to undertake well-informed decisions before commencing eviction procedures. Additionally, it can be used as input for future empirical studies in the area.

Method of data analysis

Description of the study areas

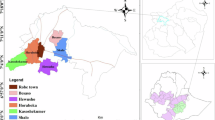

The research was carried out in urban areas within the Amhara National Regional State, specifically Injibara, Burie, and Gish Abay. Injibara, situated 420 km northwest of Addis Ababa and 135 km southwest of Bahir Dar, serves as the administrative hub of the Awi Zone in the Amhara Region. With coordinates of 10°57′N 36°56′E and an elevation of 2560 meters above sea level, the town had an estimated population of 21,065 in 2007, projected to reach 56,723 by 2023. Modern Injibara, founded in 1991 at Kosober, lies at the crossroads of the highway from Addis Ababa to Bahir Dar and the route leading west to Benishangul Gumuz and the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. On the other hand, Bure, established in 1608, is a town in western Ethiopia within the west Gojjam Zone of the Amhara Region, serving as the administrative center of the Burie district. Positioned at 10°42′0”N 37°4′0”E with an elevation of 2091 meters above sea level, Bure thrives as a major business hub connecting Wolega, Gondar, and Shewa. Gish Abay, located in west-central Ethiopia within the West Gojjam Zone of the Amhara Region, is the administrative center of Sekela Woreda. Named after Mount Gish and the Abay River (Blue Nile), Gish Abay is linked to Tilili by a 39 km gravel road, which in turn connects to the main Addis Ababa–Debre Markos–Bahir Dar Road. With geographical coordinates of 10°59′N and 37°13′E and an elevation of 2744 meters above sea level, the town embodies a significant locale in the region (Central Statistical Agency, 2013) (see Fig. 1).

Data collection and sampling

In this research, a multi-stage sampling technique was used to determine the sample households. In the first stage, the Amhara regional state was purposively selected due to its high rate of urban growth (6%), surpassing both other regions and the national average growth rate of the country (3.86%). In the second stage, two representative zonal administrations (Awi and West Gojam zones) were randomly selected from eleven zones where urban expansion is undergoing in the region based on their swiftness of urban expansion. In the third stage, three municipalities (Injibara, Burie, and Gish Abay municipalities) were randomly selected out of the existing municipalities based on the urban expansion potential and speed of urban growth where a large number of investors are attracted, public sector projects are expanding drastically, industrial expansion and land demand for residential is accelerating compared to others. In the fourth stage, eleven peri-urban kebeles were selected purposively for easy access to the targeted population. Finally, evicted households were systematically chosen from the household lists provided by each municipality’s registrar using the proportional-to-size method.

To reduce the possible sampling error, a random sampling technique was employed. To be specific, a systematic random sampling technique was employed as the random sampling to ensure the representativeness of on-target group-households that got displaced. Finally, representative samples were selected from each kebeles based on probability proportional to sample size (PPS). Hence, the sample size was determined by using (Kothari, 2004) formula.

where n = sample size, z = the value of the standard variate at a given confidence level (z = 1.96 for 95% confidence level), P = sample proportion, q = 1−p and e = acceptable error (e = 5%). N is the total number of households from which the sample is drawn.

Thus, the sample size of evicted households will be:

Theoretical framework

The structural equation model (SEM) is a statistical modeling technique that combines both measurement models and structural models to analyze complex relationships among observed and latent variables. SEM allows researchers to test and estimate the associations between variables, taking into account measurement error and the underlying theoretical framework (Byrne, 2013). It has two components: the measurement model and the structural model.

The measurement model specifies the association between observed variables and latent constructs. The measurement model defines how these latent constructs are measured using observed variables, often through the use of multiple indicators. It allows researchers to assess the reliability and validity of the measurement instruments (Wright, 1934). The measurement model is a crucial component of the structural equation model (SEM) that specifies the relationships between observed variables and latent constructs. It outlines how the observed variables are used to measure the underlying theoretical concepts or latent variables. The measurement model accounts for measurement error and provides a way to assess the reliability and validity of the measurement instruments (Wright, 1934; Kline, 2018).

Latent constructs, also known as factors or latent variables, are unobserved variables that represent theoretical concepts that are considered key components of measurement models. They are not directly measured but inferred from the observed variables. However, observed variables, also called indicators or manifest variables, are the measurable variables that are used to capture the latent constructs. They can be survey items, observed behaviors, or other quantifiable measurements. Each latent construct is typically indicated by multiple observed variables, forming a set of indicators (Hu and Bentler, 1999).

The measurement model specifies the relationship between the observed variables and the latent constructs. It defines how the observed variables are related to the underlying construct they are intended to measure. This relationship can be represented by factor loadings, which indicate the strength and direction of the association between each observed variable and the corresponding latent construct. Moreover, reliability refers to the consistency or stability of measurement. In the measurement model, reliability is assessed by examining the factor loadings and the internal consistency of the indicators (Hassim et al., 2020). Common measures of reliability include Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability where higher factor loadings and internal consistency coefficients indicate greater reliability.

The structural model is a core component of the structural equation model (SEM) that represents the causal relationships among latent constructs. It specifies the direct and indirect effects between variables and provides insights into the underlying theoretical framework (Bentler and Bonett, 1980; Kline, 2018). The structural model allows researchers to test hypotheses, analyze complex relationships, and evaluate the overall fit of the model.

The causal relationships of the structural model represent how one latent construct directly or indirectly influences another latent variable. These relationships are typically depicted as arrows connecting the constructs in a path diagram, whereas direct effects represent the immediate impact of one construct on another, and indirect effects occur when the influence of one construct on another is mediated by one or more intervening constructs. Indirect effects are estimated by decomposing the total effect into direct and indirect components using statistical techniques such as mediation analysis. Moreover, estimating the structural model involves determining the strength and significance of the relationships between constructs (Byrne, 2013).

Model specification and hypothesis development

The objective to estimate psychological traits such as perception, attitude and satisfaction towards land eviction of peri-urban farmers have different measurements which can be explained by latent variables. In this research, the latent variables that are supposed to explain the objective of this article are hypothesized as the attitude of peri-urban farmers towards the land valuation process; compensation practices undertaken; and livelihood improvement after eviction had taken place. These indicators serve to explain the latent variables on one side, while on the other side, these latent variables exert influence (cause) on other latent variables. Chikkala and Kumar (2021) in their book noted that “over the years, numerous large-scale development projects have managed to displace millions of people without providing them with meaningful compensation while also failing to consider their perception towards compensation”. Not only is compensation often inadequate from a purely financial perspective, but it is further diminished by corrupt practices and distortions during its distribution.

According to Mathur (2009), impoverished individuals often do not receive the full compensation they are entitled to, hindering their recovery from losses. The most vulnerable individuals are disproportionately affected by rampant corruption, and government agencies lack integrity in ensuring timely disbursement of rightful compensation. Unnecessary government intervention impedes market-driven transactions between willing buyers and sellers, even in circumstances of land acquisition for private sector initiatives. This results in lower compensation for small landowners and a rise in poverty (Addisu, 2015).

Global research on land eviction increasingly focuses on exposing the risks of eviction faced by displaced farmers and emphasizes the need for targeted strategies to mitigate these risks and facilitate rehabilitation (Mathur, 2009; Cernea, 2000, 2021; Chikkala and Kumar, 2021). Consistently, the findings highlight recurring risks and destitution outcomes rather than isolated incidents. One significant factor contributing to this impoverishment is the deliberately low compensation payments maintained by many governments, reflecting their political and policy stance (Sen, 2004).

The relationships among the proposed variables were established through the analysis of previous empirical evidence and existing literature (Pascual et al. 2012). The observed relations on the parameter path were used by the model to assess the extent to which the hypothesized connections were captured. Therefore, this study employed the empirical model proposed by (Cernea, 2000) and further developed by (Cernea, 2021).

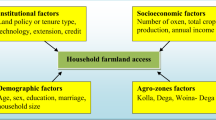

Drawing upon the theoretical and empirical foundations discussed above, this research aimed to examine the relationship between latent variables (valuation (F1), compensation (F2), and livelihood (F3)) and their corresponding indicators. Additionally, attempted to investigate the direct and indirect effects of land valuation and compensation on livelihood. It also considered compensation as a mediating variable to look through the indirect effect of valuation on livelihood. The study employed a structural equation model, focusing on the perception of peri-urban farmers regarding farmland eviction resulting from urban expansion. Based on the above discussion, the following hypotheses are developed:

H1: Land valuation process positively affects the amount of compensation that evictees are provided.

H2: the amount of compensation provision positively affects the livelihood improvement of evicted farmers.

H3: Land valuation process positively affects the livelihood improvement of evicted farmers.

H4: The compensation amount mediates the relationship between the land valuation process and livelihood improvement of evicted farmers.

The observed variables such as the participation level of evicted farmers during the land valuation process (participation), the technical skill of land valuation committee members (skill), reduced level of corruption and mal-practices of the land valuation experts and local administrators (corruption), government supportive policies, land tenure reforms, and government programs targeting displaced farmers (gov. policy), the availability of essential services and facilities in the vicinity, major infrastructure projects, and commercial developments (location) are indicators of the latent variable of land valuation process (valuation/F1). On the other hand, increased number of new employment opportunities for the household (newjob), the consideration of inflation and future losses i.e., if the cash compensation considers inflation and factors in any potential future losses or risks associated with the eviction (inflation), timely and full payment i.e., the full amount is paid to the farmers in a timely manner or not delayed or partial payments can indicate inadequacy and cause financial hardships for the evicted farmers (timely pay) are indicator variables for the latent variable compensation practices (compensation/F2). Lastly, indicators such as the reduced prevalence of malnutrition and decreased incidence of disease (incidence), increased income and saving of the household (income), and access to infrastructure after eviction (infrastructure) were indicators of their respective latent variable, i.e. the livelihood improvement of evicted farmers after eviction (livelihood/F3).

Construction of structural model

The structural model that describes the causal relationship between latent variables is expressed as (Peng and Jiang, 2022):

where η = (n1, n2, ….., nn) is the vector composed of intrinsic latent variables, ξ = (ξ1, ξ2,⋯,ξn) is the vector composed of extrinsic latent variables, B(m × m) is the path coefficient matrix of intrinsic latent variables, Γ(m × n), represented the path coefficient matrix of exogenous latent variables, whereas the vector made up of residual terms, τ(m × 1), represent the proportion of η in the equation that is not explained. The observed variables that correlate to latent variables made up of a measuring portion of the structural equation model. The following is an expression of the relationships between the latent variables and the observed variables:

The equations that affect the measurement model are as follows:

The measurement equations of exogenous latent variables and explicit variables are expressed as

The measurement equations of endogenous latent variables and explicit variables are expressed as

Based on the above theoretical model, the empirical path model of this research is written within the following system of structural equations:

where Fs are latent variables; Q1–Q11 are indicator variables (Table 2) and es are error terms, while σ are (m × n) path coefficients. The path diagram between F1, F2, and F3 shows the cause–effect relationship between latent variables. Every model construct was evaluated using a series of rating scale items (questions) undertaken with a five-point Likert-scale grading (strongly disagree = 1, disagree = 2, indifferent = 3, agree = 4 and strongly agree = 5) (see Table 1).

Results and discussion

The structural equation model (SEM) in this analysis involved the measurement model assessment and then the structural model assessment (Ali and Park, 2016). To assess the structural model, it was necessary to ensure that all the constructs were accurately measured. For hypothesis testing purposes, a partial least-square structural equation model (PLS-SEM) was adopted. As per Lowry and Gaskin (2014) PLS-SEM measures the measurement model and the structural model at the same time. The reason for choosing SmartPLS over other statistical packages is its utilization of the partial least squares (PLS) algorithm, which is specifically designed for conducting PLS-based structural equation modeling (SEM) analyses. It is a variance-based approach that is well-suited for exploratory research and complex models with latent variables that focus on prediction, theory development, or small sample sizes and contextually appropriate choice since it does not require any parametric condition (Wynne W. Chin, 1998) and also overcome with the limitation of small sample size (Alapján-, 2016) while SPSS and AMOS, on the other hand, primarily use the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) method, which is more suitable for confirmatory research and larger sample sizes (Hair et al. 2019). Moreover, SmartPLS, is known to be more robust to violations of normality assumptions in the data. This means that SmartPLS can handle data that may not meet the strict normality requirements of MLE-based approaches used in SPSS and AMOS. It also applies bootstrapping i.e., a non-parametric resampling technique that does not rely on assumptions of normality and is considered more robust (Hair et al. 2019; Henseler et al. 2016). Furthermore, SmartPLS allows for both reflective and formative measurement models. Reflective models assume that observed variables directly measure underlying latent constructs, while formative models treat observed variables as indicators that define the latent constructs. SPSS and AMOS primarily focus on reflective measurement models (Gefen et al. 2011). Furthermore, SmartPLS employs bootstrapping as the default method for estimating standard errors, generating confidence intervals, and conducting significance tests. Bootstrapping is a resampling technique that does not rely on distributional assumptions, providing more robust statistical inference. SPSS and AMOS also support bootstrapping, but it may require additional steps or extensions (Henseler et al. 2016). Therefore, PLS-SEM is a non-parametric multivariate technique that has gained much recognition in academia (Ketchen, 2013). The Smart PLS package was used for data analysis.

Evaluation of the model

All three constructs in the model were measured reflectively. The reliability of the model was evaluated by the Cronbach Alpha, and it was >0.6 of the minimum thresholds. The composite reliability (CR) was calculated to measure the internal consistency of the constructs. CR was >0.7 for all the constructs. Moreover, convergent validity refers to how well a measure correlates positively with alternative measures of the same construct. In the domain sampling model, indicators of a reflective construct are treated as diverse methods to capture the same construct. Therefore, indicators of a specific reflective construct should converge or exhibit a significant proportion in variance. To assess the convergent validity of reflective constructs, consider the outer loadings of the indicators, and the average variance extracted (AVE) are employed. Large outer loadings on a construct suggest that the related indicators share a significant portion of commonality that is represented by the construct. It is essential that all indicators display statistically significant outer loadings, with standardized outer loadings ideally reaching or exceeding 0.708. Meanwhile, the AVE value equal to or exceeding 0.50 suggests that, on average, the construct accounts for over half of the variance among its indicators. Conversely, an AVE below 0.50 implies that, on average, more variance is attributable to measurement error in the items rather than being explained by the construct (Ketchen, 2013). Based on the above references, the outer loadings were significant and higher than 0.7, while the average variance extracted (AVE) was found to be >0.5 and significant at a 95% level (see Table 2).

Discriminant validity is the degree to which a construct in the model is actually unique from other constructs. In order to make sure that the various constructs being constructed are measuring distinct elements as intended, it is crucial to validate that there is no strong correlation between them. This was established using the criteria of Heterotrait–Monotrait (HTMT) ratio which could be <1.0. This criterion is the strictest among the other two criteria for discriminant validity viz. cross-loading criteria and the Fornell and Larker criteria (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Hence, the Heterotrait–Monotrait ratio (HTMT) value of the data for each of the constructs is below one. Therefore, the model is a well-fitted model (see Table 3).

As per Edeh et al. (2023) collinearity assessment needs to be carried out before the structural model evaluation. Towards this end, the VIF for each of the construct items was ascertained. The measurement models for the collinearity of indicators are by looking at the indicators’ variable inflation factor (VIF) values to assess the collinearity problem among the indicators. Each predictor construct’s (VIF) value should be higher than 0.20 (lower than 5). According to the results, “location” has the highest VIF value (4.44). Hence, VIF values are uniformly below the threshold value of 5 (see Table 4).

We conclude, therefore, that collinearity does not reach critical levels in any of the and is not an issue for the estimation of the PLS path model. Hence, there was no collinearity concern in the data. Moreover, multicollinearity test result for latent variables using Inner VIF values is depicted below (see Table 5).

One of the commonly used measures to evaluate the structural model is the coefficient of determination (R² value). This coefficient is a measure of the model’s predictive power and is calculated as the squared correlation between a specific endogenous construct’s actual and predicted values. The “R square” value is given in Table 6. Hence, the R-square for the construct compensation and livelihood is 0.036 and 0.203, respectively, which the construct can be described as weak, but both of the constructs have strongly significant coefficient of determination (see Table 6).

Apart from assessing the R² values for predictive accuracy, researchers should analyze Stone–Geisser’s Q² value as well which is called the blindfolding measure (Geisser, 1974; Wynne W. Chin, 1998; Chin, 2010; Preacher and Hayes, 2008). This measure serves as a gauge of the model’s capability to predict out-of-sample data or its predictive relevance. When a PLS-SEM path model demonstrates predictive relevance, it effectively forecasts data that were not part of the model’s estimation. In the structural model, Q² values above zero associated with a reflective endogenous latent variable signify the predictive relevance of the path model for a specific dependent construct. Thus, the blindfold estimation of the PLS-SEM model yields a Q2 value above 0, it indicates the predictive relevance of the endogenous variables under scrutiny (see Table 7).

The path coefficients are ascertained after running the PLS algorithm. The algorithm is designed to reject a set of path specific null hypothesis of no effect. The study highlighted that the construct valuation had the highest effect (β = 0.306***, t = 4.203) on the livelihood followed by compensation (β = 0.277***, t = 4.203 (see Table 8).

This finding can be ascribed that the present study was based on the evicted farmers perception towards land eviction. It was observed that compensation mediates the association between the construct’s valuation and livelihood which supported the fourth hypothesis (H4). This is because as per the theory, significant indirect effects using bootstrapping mean significant mediation (Preacher and Hayes, 2008) (see Fig. 2).

Test for goodness of fit

The goodness of fit measure was ascertained as per (Henseler and Sarstedt, 2013). The standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) was 0.097 which was well below the threshold limit of 0.14. Thus, the model was an overall good fit (see Table 9).

Result

The factors identified in this study, which encompass different dimensions of perceptions related to land eviction in peri-urban areas, exhibit intricate interconnections. To understand these relationships, a structural equation modeling (SEM) approach, using SmartPLS, was employed to develop a construct of “valuation-compensation-livelihood improvement” in peri-urban areas, as shown in Fig. 2. Under the hypothesis verification of ensuring the influences between various potential variables, the specific influencing factors of the land eviction perception by each observation variable need to be judged according to the specific path value of each observation variable. In order to enhance the likelihood to improve livelihood of evictees after land expropriation, municipal administrators should know how to make the victimized farmers sustainable, particularly in the time of post-eviction when development-induced urban expansion is undertaken and make the evicted farmers partners in development intervention making them to have a positive attitude towards land eviction.

-

I.

Land valuation process: The standardized path coefficients for the land valuation process among evicted farmers are illustrated in Fig. 2. These coefficients pertain to observed variables such as (location) which define the availability of essential services and facilities in the vicinity, major infrastructure projects, and commercial developments; (skill)—the technical skill of land valuation committee members, (corruption)—corruption and malpractices of land valuation experts and local administrators; (gov. policy)—supportive government policies, land tenure reforms, and government programs; and (participation)—the level of participation of evicted farmers during the land valuation process. The respective path coefficients for these variables are 0.844, 0.765, 0.744, 0.775, and 0.784. Among these variables, the highest path coefficient is assigned to the availability of essential services in the vicinity (location, 0.844), indicating its strongest association with the perception of land valuation among evicted farmers. The level of participation (participation, 0.784) follows as the second-highest path coefficient. Government policy (Gov. policy, 0.775), technical skill of land valuation experts (skill, 0.765), and corruption and malpractices (corruption, 0.744) rank third, fourth, and fifth, respectively. Importantly, all variables exhibit strong associations as reflected by their path coefficients. Therefore, it is crucial for municipality administrators and policymakers to prioritize and pay special attention to improving the positive attitude of evicted farmers towards land valuation, considering the significant correlation of these variables.

-

II.

Compensation practices: The path values of observed variables incorporate various factors when determining compensation practices for evictees. These factors comprise inflation and future losses (inflation), the increased number of new jobs available to household members (newjob), and the complete and timely payment of compensation (timely payment). These variables have path values of 0.825, 0.827, and 0.871, respectively. The highest path value is assigned to timely payment at 0.871, indicating its crucial role in fostering a positive attitude among evictees towards compensation. Ensuring on-time payment of the full compensation amount without any delays significantly contributes to a positive perception of the compensation process. Additionally, the variables of increased new job opportunities (newjob, 0.827) and considering inflation when determining compensation (inflation, 0.825) have path values close to timely payment, suggesting that they also play vital roles. Therefore, it is reasonable to consider these variables to cultivate a positive attitude among evicted farmers toward the compensation they receive.

-

III.

Livelihood improvement: The path values of the observed variable i.e., the livelihood improvement status are reduced prevalence of malnutrition and decreased incidence of disease (incidence), increased income and saving of the household after eviction (income), increased access to infrastructure such as health institutes, market, electricity, tap-water, etc after eviction (infrastructure) 0.924, 0.925 and 0.779, respectively. The path value of income (0.925) is the largest, indicating increased income and saving of evictees is a key indicator of livelihood improvement after eviction and improving the income level of evicted farmers plays a key role. The reduced prevalence and incidence of disease (incidence, 0.924) and increased access to infrastructure (infrastructure, 0.779) all have the highest association with the latent variable, indicating that these variables have a significant correlation with livelihood improvement.

-

IV.

The direct, indirect, and total effect: This article explores the effect of the land valuation process (valuation) and compensation practices (compensation) on livelihood improvement (livelihood). Valuation (F1) is an exogenous latent variable, while compensation (compensation/F2) is an endogenous latent variable and intermediate control variable. These factors influence directly or indirectly the livelihood improvement (F3) variable. Based on the above premises, valuation (valuation/F1) has a direct effect on livelihood improvement (livelihood/F3). The hypothesis is that the land valuation process has a direct positive impact on the livelihood improvement of the household at (p = 0.000). Figure 2 shows that the estimate from valuation (F1) to livelihood (F3) is 0.306, depicting that the land valuation process has an important influence on the livelihood improvement of the evicted households. Meanwhile, the land valuation process also has significant positive influence on compensation practices (compensation/F2) at (p = 0.000). The estimate from valuation (F1) to compensation (F2) is 0.189 at (p = 0.008), indicating that the land valuation process has a positive influence on the compensation amount provided to the evicted farmers and this result supported the hypothesis that states compensation has a positive impact on livelihood improvement.

The land valuation significantly affects livelihoods improvement, as indicated in Fig. 2. The analysis reveals that land valuation indirectly influences livelihood improvement (0.052) with a significance level of p = 0.028. Furthermore, the findings demonstrate a positive correlation, indicating that land valuation has a beneficial effect on the livelihood improvement of farmers who have been evicted. The municipal administrators should focus on the land valuation process which can strengthen the livelihood of evicted farmers in a sustainable way. The total effect of the latent variable land valuation is 0.358 which is the sum of the direct effect of valuation and the indirect effect of valuation through the mediating variable compensation. Therefore, land valuation has a significant influence on livelihood.

Discussion

The perception of peri-urban farmers regarding land eviction has significant implications for the future development agendas of the government. While development plans often involve acquiring land from farmers, it is crucial to consider the farmers’ attitudes towards these initiatives. Positive attitudes can foster cooperation and facilitate the implementation of development projects. However, if farmers perceive corruption, malpractice, inadequate compensation, and a lack of improvement in their livelihoods after receiving compensation, their attitude towards land eviction becomes highly skeptical.

The result of the measurement model stated that the association between the factor (valuation/F1) and the item variables, such as corruption, skill, location participation, and government policy, has a strong and positive relationship with the factor loadings (0.744, 0.765, 0.784, 0.775, 0.844), respectively. This depicted that there is a strong correlation between the land valuation and the respective indicators. These associations illustrate that, when corruption is prevalent, dishonest practices may occur, such as bribery or manipulation of land values. This can result in an unfair land valuation process for evicted farmers, as their land may be undervalued deliberately. This can be evidenced by the strength of the factor loading with a higher value (0.744), indicating that reduced corruption and malpractices of land valuation experts explained the land valuation process positively. Corruption undermines the transparency and integrity of the valuation process and can lead to social and economic injustices. Moreover, the expertise skill and competence of land valuation experts involved in the process are also essential, which can explain its factor loading value (0.765). Competent professionals with extensive knowledge of land valuation methods and market trends can provide accurate and fair valuations. However, if the experts lack expertise or are influenced by external pressures, their valuation may be biased or inaccurate, leading to unjust valuation for the affected farmers (Chikkala and Kumar, 2021). Furthermore, the location of the land plays a crucial role in its valuation, having a strong association with land valuation (0.844). this is due to various factors such as infrastructure development, natural resources, and market demand for the land can influence its value. If the land is situated in a prime location with high development potential, its value may be higher compared to remote or less desirable areas.

The participation level of evicted farmers also has a strong correlation with the land valuation process depicted by large factor loading (0.775). If the evictees participate actively, they may gain more negotiation power and higher participation levels can signal unity and determination among the farmers, making it difficult for the municipal authorities to disregard their demands completely. This increased bargaining power may lead to negotiations between the farmers and the municipal authorities, potentially affecting the land valuation process by providing firsthand knowledge and evidence about the land’s productivity, historical use, or other relevant factors potentially leading to adjustments in the land’s valuation. Hence, the strong participation of evicted farmers during the land valuation process can generate pressure on the municipal authorities responsible for the eviction. Policymakers may feel compelled to address the concerns raised by the farmers or to intervene in the valuation process to ensure fairness (Cernea, 2021). However, participation alone does not guarantee to secure a fair valuation unless supporting government policy is devised. The measurement model result of this research confirmed that supportive government policy has a strong relationship to the land valuation process with a high factor loading of (0.775). Well-designed policies play a crucial role in ensuring a fair and transparent land valuation process during evictions by outlining the factors to be considered during valuation and providing a framework for resolving any grievance and social unrest that may arise. The result conforms with other empirical works such as (Mathur, 2009; Addisu, 2015).

In the context of compensation for evicted farmers, inflation has a positive and strong association with a factor loading value of 0.825. provision of compensation without taking into account the inflation variable can erode the value of the compensation received. If the compensation is not adjusted to account for inflation, the purchasing power of the farmers may diminish over time (Ambaye, 2001; Daniel, 2015). Therefore, it is important for compensation practices to consider inflationary factors and ensure that the amount provided adequately reflects the economic realities at the time of the eviction. Besides, the creation of new job opportunities for evicted farmers and their households can impact compensation practices in several ways. Firstly, if the farmers are able to secure alternative employment or income-generating activities, the compensation may be adjusted to reflect their improved financial situation. This adjustment could potentially result in lower compensation amounts. Additionally, if the farmers are offered new job opportunities as part of the compensation package, the value and nature of those employment options may be factored into the overall compensation assessment. Hence, this logic was verified by this empirical finding that there is a strong association between new jobs and compensation having a strong association (0.827) factor loading. Furthermore, timely payment has a strong correlation with compensation having a larger factor loading (0.871). This is due to the fact that timely payment of compensation is crucial for ensuring the well-being and stability of evicted farmers. Delayed or irregular payments can create financial hardships, disrupt livelihoods, and prolong the rehabilitation process. Therefore, compensation practices should prioritize prompt payment to minimize the negative impacts on the farmers. This allows the farmers to make necessary arrangements, such as acquiring new land or investing in alternative livelihoods, without undue delay or uncertainty (Admasu et al. 2019).

The livelihood improvement of evicted farmers can be associated with indicator variables, including increased income and savings, improved infrastructure, and a reduction in the incidence of disease and malnutrition. The factor loadings of these variables depicted a strong correlation between the indicator variable inflation (0.825), newjob (0.827), and timely payment (0.871) and the latent variable (livelihood improvement). Improved infrastructure, such as access to better housing, clean water, sanitation facilities, and transportation, can significantly enhance the living conditions of evicted farmers. Adequate infrastructure creates an enabling environment for economic activities and social well-being (Gulyani and Talukdar, 2010). Furthermore, the reduction in the incidence of disease and malnutrition can be attributed to various factors. With improved income, farmers have better access to nutritious food, leading to improved dietary intake and a decrease in malnutrition (Bloom et al. 2004). Overall, when livelihood improvement is prioritized during the eviction process, and appropriate support mechanisms are in place, evicted farmers can experience positive changes in their income, savings, infrastructure, and health condition.

The structural model of this research depicted that the land valuation process has a direct effect on compensation practices and livelihood improvement with regression coefficients of 0.189 and 0.306, respectively, where the influence on both variables is highly significant at <1%. The land valuation process and compensation practices should also consider supporting evicted farmers in transitioning to alternative livelihoods. Evicted farmers in the land valuation process and compensation practices can contribute to better outcomes for their livelihoods. Agrawal and Redford (2009) argue that participatory approaches empower farmers, enable their voices to be heard, and ensure that compensation practices align with their needs and aspirations. This implies that the provision of adequate compensation and fair valuation of the land they dispossessed can help evicted farmers explore new income-generating opportunities and improve their livelihoods in non-agricultural sectors (Béné, 2011; Bishu et al. 2018). Furthermore, land valuation has a significant indirect effect on livelihood with the coefficient value of 0.052 at a <5% significant level. This indicates that the outcome of livelihood improvement is indirectly influenced by the land valuation process and this logic is conformed with the previous empirical works of Holden et al. (2019).

Conclusion and recommendations

This paper is the first of its kind that investigates the perception of evicted peri-urban farmers towards land eviction. The SEM of “land valuation process—compensation practices—livelihood improvement” is constructed. These findings highlight the importance of considering farmers’ perceptions and attitudes towards land eviction in the formulation and implementation of development programs particularly initiatives that can undertake land eviction, which directly affect peri-urban farmers. Addressing issues such as the land valuation process, ensuring fair compensation, and improving livelihoods are crucial steps towards fostering a positive perception among peri-urban farmers. Depending on the result of the measurement model of SEM, all the latent variables are strongly and significantly associated with respective indicators, signifying that the land valuation process has a strong association with variables such as corruption, participation, skill, location, and government policy. However, compensation practice also has a strong association with indicator variables such as inflation, new jobs, and timely payment of the compensated money. Lastly, the livelihood improvement o evicted farmers have strong and positive relationship with the variable income, infrastructure, and reduced incidence of disease and malnutrition.

In the context of the structural model, the land valuation process and compensation practice exert an impact on livelihood improvement. Compensation practice also is a mediator that significantly influences livelihood improvement. Moreover, the land valuation process can indirectly influence livelihood improvement through the compensation practice. Furthermore, land valuation has also been verified to be a very important antecedent that directly influences the factor “compensation practices”.

This paper attempted to develop and empirically examine a conceptual model of the land valuation process, compensation practices, and livelihood improvement of evictees when expropriation is undertaken. This research represents a pioneering effort in both the development and empirical investigation of a conceptual model that examines the interplay between the land valuation process, compensation practices, and the subsequent improvement of livelihoods among individuals who have experienced eviction as a result of urban expansion. Municipal administrators are advised to prioritize these aspects when planning and designing evictions for urban expansion. This approach will help evicted farmers to have a positive perception towards land eviction and development initiatives. Hence, it is recommended that:

-

1.

Creating a system that reduces corruption during land valuation. This can be addressed by establishing transparent procedures and guidelines for all government transactions; create a strong legal framework to enact and enforce strict anti-corruption laws; train public servants on ethics, integrity, and the effects of corruption; and ensure that human resource recruitment, promotion, and decision-making procedures are based on merit.

-

2.

Strengthening the participation of evicted farmers in the land valuation process is essential. Often, these farmers are inadequately represented and have limited participation before, during, and after eviction, leading to their perspectives, voices, and options being overlooked. This exclusion contributes to feelings of marginalization as urban development encroaches upon their lands.

-

3.

It is crucial to provide priority in employment opportunities to the evicted households in both the public and private sectors following the eviction process. This approach aims to ensure sustainable livelihoods for these evictees and foster a positive attitude towards land eviction and urban development projects.

-

4.

When providing compensation, considering inflation expectations is paramount. Planning for one’s financial future is essential for farmers facing eviction, particularly if it involves losing their primary source of income. The compensation can be designed to offer long-term, sustainable financial protection that requires price increases into account by considering inflation expectations.

By considering these factors, policymakers can establish a conducive environment for sustainable and inclusive development that aligns with the needs and aspirations of the farming communities affected by eviction.

Data availability

The data set generated during and/or analyzed during the current study is submitted as supplementary file and can also be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Addisu A (2015) Urban expansion and farmers’ perception in urban expansion In Axum Town, Ethiopia. J Sociol 3(9):1–14

Admasu WF, Van Passel S, Minale AS, Tsegaye EA, Azadi H, Nyssen J (2019) Take out the farmer: an economic assessment of land expropriation for urban expansion in Bahir Dar, Northwest Ethiopia. Land Use Policy 87:104038. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104038

Agrawal A, Redford K (2009) Conservation and displacement: an overview. Conserv Soc 7(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-4923.54790

Alamneh T, Mada M, Abebe T (2023a) Cogent Economics & Finance Impact of Urban expansion on income of evicted farmers in the peri-urban areas of Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia: endogenous switching regression approach impact of urban expansion on income of evicted farmers in the peri-Urb. Cogent Econ Finance 11(1):0–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2023.2199596

Alamneh T, Mada M, Abebe T (2023b) The choices of livelihood diversification strategies and determinant factors among the peri-urban households in Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. Cogent Soc Sci 9(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2281047

Alapján- V (2016) Use of partial least squares (pls) in strategic management research: a review of four recent studies. Strateg Manag J 20(2):1–23

Ali M, Park K (2016) The mediating role of an innovative culture in the relationship between absorptive capacity and technical and non-technical innovation. J Bus Res 69(5):1669–1675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2015.10.036

Ambaye DW (2001) Economic policy and sustainable land use: recent advances in quantitative analysis for developing countries. Journal: Spatial data serving people: land governance environment—building capacity, vol 4(1). p xvi

Arnstein SR (2017) A ladder of citizen participation. In: Foundations of the planning enterprise: critical essays in planning theory, Journal of the American Institute of Planners, Routledge, vol 1. pp 415–423

Béné C (2011) Social protection and climate change. IDS Bull 42(6):67–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2011.00275.x

Bentler PM, Bonett DG (1980) Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychol Bull 88(3):588–606. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.588

Bishu KG, O’Reilly S, Lahiff E, Steiner B (2018) Cattle farmers’ perceptions of risk and risk management strategies: evidence from Northern Ethiopia. J Risk Res 21(5):579–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2016.1223163

Bloom DE, Canning D, Sevilla J (2004) The effect of health on economic growth: a production function approach. World Dev 32(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2003.07.002

Byrne BM (2013) Structural equation modeling with AMOS. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410600219

Central Statistical Agency (2013) Population projection of Ethiopia for all regions at Wereda level from 2014–2017 J Ethnobiol Ethnomed 3(1):28, http://www.csa.gov.et/images/general/news/pop_pro_wer_2014-2017_final

Cernea M (2000) Impoverishment risks, risk management, and reconstruction: a model of population displacement and resettlement. In: UN symposium on hydropower and sustainable development. unpublished paper, pp 1–61

Cernea MM (2021) The risks and reconstruction model for resettling displaced populations. Social Development in the World Bank: Essays in Honor of Michael M. Cernea, September 1996. pp. 235–264. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-57426-0_16

Chambers R (1994) The origins and practice of Partici.Pdf>. World Dev 22(7):953–969

Chikkala N, Kumar KA (2021) Development projects, displacement and resettlement: Ax literature review. J Cult Soc Anthropol 3(1):27–43. https://doi.org/10.22259/2642-8237.0301004

Chin WW (1998) The partial least squares approach to structural formula modeling. Adv Hosp Leis 8(2):5

Chin WW (2010) The partial least squares approach to structural equation modeling. In: Modern methods for business research. pp. 295–336

Daniel (2015) Land rights and expropriation in Ethiopia. http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-14639-3

du Toit-Brits C(2022) Exploring the importance of a sense of belonging for a sense of ownership in learning S Afr J High Educ 36(5):58–76. https://doi.org/10.20853/36-5-4345

Edeh E, Lo W-J, Khojasteh J (2023) Review of partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using R: a workbook. Struct Eq Model 30(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2022.2108813

Endris EA, Mansingh JP, Nisha A, Anbarasan P, Makarla R (2021) Farmers’ perception on development induced farmland expropriation in Ethiopia: a review. Alinteri J Agric Sci 36(1):451–456. https://doi.org/10.47059/alinteri/v36i1/ajas21066

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res 18(1):39. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Gebeyehu Z, Haji J, Berihun T, Molla A (2022) Urban expansion impact on peri-urban farm households welfare in metropolitan cities of Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia. Ecol Environ Conserv 28(1):33–44. https://doi.org/10.53550/eec.2022.v28i01.005

Gefen D, Rigdon EE, Straub D (2011) An update and extension to SEM guidelines for administrative and social science research. MIS Q 35(2). https://doi.org/10.2307/23044042

Geisser S (1974) Effect to the random model A predictive approach. Biometrika 61(1):101–107. https://academic.oup.com/biomet/article-abstract/61/1/101/264348

Gulyani S, Talukdar D (2010) Inside informality: the links between poverty, microenterprises, and living conditions in Nairobi’s slums. World Dev 38(12):1710–1726. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2010.06.013

Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM (2019) When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur Bus Rev 31(1):2–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203

Hassim SR, Arifin WN, Kueh YC (2020) Confirmatory factor analysis of the Malay version of the smartphone addiction scale among medical students in Malaysia. Int J Environ Res Public Health Open-Access.pdf

Henseler J, Sarstedt M (2013) Goodness-of-fit indices for partial least squares path modeling. Comput Stat 28(2):565–580. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00180-012-0317-1

Henseler J, Hubona G, Ray PA (2016) Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: updated guidelines. Ind Manag Data Syst 116(1):2–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-09-2015-0382

Holden SC, Manor B, Zhou J, Zera C, Davis RB, Yeh GY (2019) Prenatal yoga for back pain, balance, and maternal wellness: a randomized, controlled pilot study. Global Adv Health Med 8:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2164956119870984

Holland M (2017) The change agent. In: Achieving cultural change in networked libraries. Macmillan Publisher, London, pp 105–117. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315263434-16

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Eq Model 6(1):1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Ketchen DJ (2013) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling. Long Range Plann 46(1–2):184–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2013.01.002

Kline RB (2018) Review of principles and practice of structural equation modeling. In: Structural equation modeling, vol 25(2). Guilford Publications, Montreal. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2017.1401932

Kosa A, Juhar N, Mohammed I (2017) Urbanization in Ethiopia: expropriation process and rehabilitation mechanism of evicted peri-urban farmers (policies and practices). Int J Econ Manag Sci 6(5). https://doi.org/10.4172/2162-6359.1000451

Kothari (2004) Research methodology: methods and techniques. 2nd edn. New Age International Publishers, New Delhi

Lowry PB, Gaskin J (2014) Partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modeling (SEM) for building and testing behavioral causal theory: When to choose it and how to use it. IEEE Trans Prof Commun 57(2):123–146. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPC.2014.2312452

Mathur HM (2009). Development Induced Displacement and the Tribals. 302

Mohammed I, Kosa A, Juhar N (2020) Economic linkage between urban development and livelihood of peri-urban farming communities in Ethiopia (policies and practices). Agric Food Econ 8(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40100-020-00164-2

Pascual U, Muradian R, Brander L, Gómez-Baggethun E, Martín-López B, Verma M, Armsworth P, Christie M, Cornelissen H, Eppink F, Farley J, Loomis J, Pearson L, Perrings C, Polasky S, McNeely JA, Norgaard R, Siddiqui R, David Simpson R, … Simpson RD (2012) The economics of valuing ecosystem services and biodiversity. In: The economics of ecosystems and biodiversity: ecological and economic foundations. Routledge, pp 183–256. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781849775489

Peng Y, Jiang X (2022) Analysis of tourist satisfaction index based on structural equation model. J Sens https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/6710530

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF (2008) Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 40(3):879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879

Sen A (2004) Dialogue capabilities, lists, and public reason: Continuing the conversation. Feminist Econ 10(3):77–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354570042000315163

Weldearegay SK, Tefera MM, Feleke ST (2021) Impact of urban expansion to peri-urban smallholder farmers’ poverty in Tigray, North Ethiopia. Heliyon 7(6). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07303

Wright S (1934) The method of path coefficients. Ann Math Stat 5(3):161–215. https://doi.org/10.1214/aoms/1177732676

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work: conceptualization: Tadele Alamneh and Melkamu Mada; methodology: Tadele Alamneh; software: Tadele Alamneh; data acquisition: Tadele Alamneh; formal analysis: Tadele Alamneh and Melkamu Mada; data curation: Tadele Alamneh and Melkamu Mada; validation: Tadele Alamneh and Tora Abebe. Drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: writing—original draft preparation: Tadele Alamneh, Melkamu Mada, and Tora Abebe.; writing—review and editing: Melkamu Mada and Tora Alamneh; visualization: Melkamu Mada and Tora Abebe. Final approval of the version to be published: project administration and supervision: Tadele Alamneh and Melkamu Mada. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Alamneh, T., Mada, M. & Abebe, T. Perception of peri urban farmers towards farm land eviction resulted from urban expansion. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 265 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04379-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04379-w