Abstract

With universities increasingly offering mindfulness-based interventions to enhance students’ mental health conditions and alleviate the strain on overwhelmed psychological services, this study aimed to investigate the potential effectiveness of a brief VR-based mindfulness intervention for university students with depression and anxiety symptoms. Employing a quasi-experimental design, the present study assessed whether the intervention could enhance students’ mindfulness, olfactory perception, and chemosensory while reducing anxiety and depression symptoms. Forty-nine university students (M = 22.06, 10 males) participated in this quasi-experimental study and were tested at three time points: T1 (pre-intervention), T2 (post-intervention), and T3 (follow-up). The intervention immersed participants in virtual environments featuring natural elements and integrated mindfulness practices. The Eligible participants displayed anxiety symptoms while engaged in the study. We also conducted person-to-person interviews and performed a thematic analysis to understand the participants’ insights and feedback regarding the intervention, aiming to inform and improve the design of subsequent interventions. The findings indicated that the intervention showed an immediate and significant impact on reducing anxiety and depression symptoms while improving mindfulness, olfactory perception, chemosensory, and sensory image. Notably, this reduction in depression and anxiety symptoms persisted for one week. Furthermore, the intervention showed the potential to enhance mindfulness and sensory imagery, with these substantial effects also enduring for one week. Qualitative results further supported the findings from the interviews. This study provides preliminary evidence for the effectiveness of brief VR-based mindfulness interventions in alleviating depression and anxiety symptoms among university students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Mental health challenges among university students have increasingly been a concern (Lattie et al., 2019; Pedrelli et al., 2015; Storrie et al., 2010). University students frequently experience subclinical levels of anxiety and depression that do not meet the threshold for clinical diagnosis but still significantly impact their well-being and academic performance (Stallman, 2010; Asif et al., 2020). These symptoms, such as persistent worry, low mood, and fatigue are often exacerbated by academic stressors such as heavy workloads and exams (Hysenbegasi et al., 2005; Zivin et al., 2009; Duffy et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021; Wuthrich et al., 2020), and by non-academic factors including body image concerns and substance use (Gao et al., 2020). Research shows that while many students may not qualify for a clinical diagnosis, they nonetheless exhibit great levels of psychological distress that warrant intervention (Wang et al., 2021). Consequently, both clinical and subclinical levels of anxiety and depression are prevalent in this population, contributing to a broader mental health crisis (Pedrelli et al., 2015), particularly in the Chinese contexts (Gao et al., 2020; X. Zhang et al., 2023).

While considerable research has focused on the psychological aspects of anxiety and depression symptoms in students, less attention has been given to sensory perceptions, which are deeply connected to mental health (Dinh et al., 1999; Flavián et al., 2021; Paletta et al., 2020, 2021; Ye et al., 2021; X. Zhang et al., 2023). Olfactory dysfunction has been identified as a potential marker of both depression and anxiety. Depression is known to impair olfactory perception, including deficits in odor identification, discrimination, and hedonic processing (Athanassi et al., 2021; Kohli et al., 2016). This connection is due in part to the shared neural circuits between olfaction and emotional regulation, as both rely on brain regions like the orbitofrontal cortex and amygdala, which are involved in processing emotional and sensory information (Wang et al., 2020). These sensory impairments may serve as both state and trait markers, depending on whether they persist after the remission of symptoms. They also affect quality of life and daily functioning, potentially contributing to the onset or worsening of depressive symptoms (Rochet et al., 2018).

In the case of anxiety disorders, recent findings indicate that generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is also associated with significant olfactory deficits. Patients with GAD show impairments in odor threshold, discrimination, and identification, with the severity of these deficits being inversely correlated with anxiety symptoms. Specifically, poorer odor discrimination is linked to more severe somatic anxiety. In contrast, overall olfactory function, as measured by the TDI score (threshold, discrimination, identification), correlates with both somatic and psychic anxiety (Chen et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020). This relationship between anxiety and olfactory impairment reinforces the idea that sensory dysfunction may contribute to or exacerbate psychological symptoms.

These findings suggest that addressing sensory dysfunction may be key to a more comprehensive understanding of depressive and anxiety symptoms as well as the corresponding treatments and interventions for alleviation. Research has shown a correlation between high sensory processing sensitivity (SPS, Aron and Aron, 1997) and psychological outcomes such as depressive tendencies and anxiety symptoms (Mac et al., 2024). Given the complex interplay between psychological symptoms and sensory perceptions, particularly olfactory function, addressing both dimensions may lead to more effective mental health interventions. Specifically, interventions should not only target emotional symptoms such as anxiety and depression but also consider the sensory experiences that may be contributing to or exacerbating these mental health issues. For university students, who are particularly vulnerable to anxiety and depression, therapeutic approaches that integrate sensory-focused interventions, such as mindfulness and virtual reality, hold promise for targeting both emotional and sensory processing issues, offering a holistic approach.

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) and mental health

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) are well-established and experimentally supported methods for addressing a range of mental health issues, particularly anxiety and depression (Aspy and Proeve, 2017; Djernis et al., 2019; Simpson et al., 2019; Yildirim and O’Grady, 2020). Rooted in Eastern contemplative traditions, MBIs have been adapted for Western contexts and have received growing attention and empirical examination over the last few decades (Djernis et al., 2019; Simpson et al., 2019; D. Zhang et al., 2021). MBIs provide a systematic framework for developing mindfulness which involves a heightened state of awareness (Tang et al., 2015), characterized by nonjudgmental attention to one’s thoughts (Simpson et al., 2019), emotions (Geiger et al., 2016), and body sensations (Pérez-Peña et al., 2022). This focused attention has been linked to various psychological and physiological advantages, including reductions in anxiety, depression, and rumination, as well as enhanced emotional regulation (Simpson et al., 2019).

In addition to its psychological benefits, mindfulness positively impacts sensory perceptions, particularly by promoting focused attention on bodily sensations (interoception) and external stimuli (exteroception). Research has demonstrated that individuals with a higher mindfulness disposition (MD) tend to exhibit enhanced awareness of both internal bodily states and external sensory experiences, particularly olfaction (Lefranc et al., 2020). This fine-tuned interplay between interoception and exteroception enables more effective emotional regulation and sensory engagement, including the heightened awareness of olfactory stimuli, which is key in processing both emotional and sensory experiences.

Furthermore, mindfulness training has shown a potential to enhance olfactory perception. Mahmut et al. (2021) found that while objective improvements in odor identification were not significant, participants reported increased awareness of odors after mindfulness training. These findings suggest that mindfulness can improve subjective sensory perception, contributing to the broader benefits of sensory engagement in mental health interventions.

Enhancing mindfulness with natural exposure

The combination of mindfulness and nature has been shown to yield significant improvements in mental health, particularly by reducing symptoms of anxiety, depression, and cognitive fatigue (Hanley et al., 2017). Natural environments have long been recognized as powerful enhancers of mindfulness practices, primarily through their ability to support cognitive restoration and emotional well-being. Two leading theories explain the restorative power of nature: Attention Restoration Theory (ART) and Stress Reduction Theory (SRT). ART posits that natural environments help restore attention by providing a soft fascination that allows cognitive fatigue to dissipate, while SRT suggests that exposure to nature reduces stress by promoting a calm, reflective state that lowers physiological arousal (Kaplan, 1995; Ulrich et al., 1991).

Mindfulness, which involves focused attention and nonjudgmental awareness of the present moment, aligns well with the natural settings described by these theories. Research comparing mindfulness practices in natural versus urban environments consistently shows that natural surroundings enhance the effectiveness of mindfulness. For instance, Djernis et al. (2019) found that mindfulness training conducted in natural settings led to greater improvements in mood and mental well-being compared to similar practices in urban environments. Accordingly, certain natural scenes are commonly integrated to facilitate mindfulness practice, such as oceans, flowers, rivers, and forests (Ma et al., 2023).

Natural spaces seem to facilitate deeper mindfulness by fostering a sense of connection to one’s surroundings, which enhances sensory perceptions and emotional regulation (Hanley et al., 2017). In addition, nature also contributes to enhanced sensory awareness. The immersion in natural settings often heightens perceptions such as sound, smell, and sight, which complement the core aspects of mindfulness. This sensory engagement is key to improving interoceptive and exteroceptive awareness, helping individuals become more attuned to both their internal bodily states and external stimuli, such as the feel of the wind or the sound of rustling leaves (Paletta et al., 2020). Natural environments, through their gentle stimuli and stress-reducing properties, offer an ideal backdrop for mindfulness, amplifying its benefits and creating a deeply restorative experience. Given these synergies, integrating nature-based elements into mindfulness practices can lead to more effective outcomes for improving mental health and sensory perceptions, especially for individuals facing high levels of stress or mental fatigue.

Nature-based MBIs through VR: a holistic approach

Virtual reality (VR) has emerged as an innovative and effective tool for enhancing mindfulness interventions. Incorporating mindfulness practices into VR interventions is a noteworthy avenue of exploration. Previous research established a serious learning meditation environment with the help of cloud technology, proving VR can be used to increase the effectiveness of MBIs (Cikajlo et al., 2017). Another study evaluated the engagement of students in mental health training, exploring the applicability of Virtual Reality Apps in assisting the MBCT (Damen and Van Der Spek, 2018).

Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of VR-based interventions in improving mental health outcomes, particularly for anxiety and depression. For instance, Failla et al. (2022) found that VR-enhanced mindfulness interventions were associated with significant reductions in anxiety and depressive symptoms. Similarly, Navarro-Haro et al. (2017) showed that VR-facilitated mindfulness could increase mindfulness engagement by immersing participants in calming, nature-based virtual environments. These studies highlight the potential of VR to not only simulate natural surroundings but also amplify the benefits of mindfulness by providing users with a fully immersive, distraction-free experience that promotes emotional regulation and cognitive restoration. Based on the promotion of MBIs by natural exposure, recent studies emphasize the critical significance of natural surroundings in enhancing the effectiveness of virtual reality-based mindfulness programs (Sadowski et al., 2020; Sadowski and Khoury, 2022). VR offers a way to create immersive, engaging environments that replicate natural settings (Burdea and Coiffet, 2003). Through VR, users can fully engage with virtual simulations of nature, allowing them to experience the benefits of natural exposure without the need to physically visit these environments. This technology creates a sense of presence that fosters deep relaxation and focused attention, key components of mindfulness practice (Riva, 2005). For instance, Giachos et al. (2022) developed the Nature-Based Stress Reduction (NBSR) program to advocate for the use of the natural video component in mindfulness meditation. The use of VR to study multisensory environments also has shown great promise. Yildirim et al. (2024) employed a multisensory VR system to simulate workplace environments that integrated visual, auditory, and olfactory elements to investigate the restorative benefits of nature-based experiences. Their study demonstrated that VR is not only effective in recreating real-world settings with high ecological validity but also offers precise control over experimental variables, which enhances the internal validity of research. By immersing individuals in these controlled environments, VR enables users to escape the stressors of their daily lives and focus on mindfulness in a way that may be more accessible and impactful than traditional methods. Research indicating the extra restorative gains from natural settings, combined with the established beneficial relationship between nature interaction and mindfulness, endorses the idea of embedding nature-based features within more immersive virtual reality mindfulness exercises.

For university students, the utilization of virtual reality (VR) technology in mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) is a practical, accessible solution for reducing their anxiety and depression symptoms (Failla et al., 2022; Kaplan-Rakowski et al., 2021; Modrego-Alarcón et al., 2021). For example, Falconer et al. (2016) demonstrated the feasibility and acceptability of using VR to deliver mindfulness interventions, reporting substantial reductions in anxiety symptoms among university students. Moreover, Gál et al. (2021) highlighted the potential of VR in managing academic stress through mindfulness-based interventions. By providing immersive, virtual natural environments, VR allows students to practice mindfulness in a controlled setting, enabling them to experience the psychological and sensory benefits of mindfulness without the constraints of time or physical access to nature (Lee et al., 2020). This approach, as demonstrated by Yildirim et al. (2024), can significantly enhance both emotional well-being and cognitive performance, making it a promising tool for addressing the mental health challenges that are increasingly prevalent in academic settings (Stallman, 2010).

Research questions and hypotheses

While extensive research has demonstrated the benefits of MBIs and nature exposure in improving mental health, there remain gaps in understanding how immersive VR environments (especially natural settings) can enhance these interventions, particularly in university students facing academic and emotional stress, particularly within mainland China (Cieślik et al., 2020). Additionally, the relationship between mindfulness, sensory perceptions—particularly olfaction—and mental health, has been underexplored. Previous studies have focused primarily on the emotional and cognitive benefits of mindfulness but have overlooked the sensory dimension, despite growing evidence linking sensory processing with mental well-being.

This is especially important given the increasing frequency of mental health issues in this group, where existing support services and healthcare resources frequently fall short of meeting the increased treatment needs (Charlson et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2019). This research gap highlights the importance of performing thorough studies to investigate the potential advantages of integrating mindfulness and virtual nature experiences customized particularly for university students in mainland China, who experienced depression and anxiety symptoms (Gao et al., 2020; Wang and Liu, 2022) and exhibited higher sensory processing sensitivity compared to American college students and Japanese (Ye et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2023).

Filling this gap will not only benefit the mental health of this vulnerable population but will also provide insight into innovative methods for developing effective and accessible mental health treatments within the specific socio-cultural framework of China’s university settings. Additionally, mindfulness practices emphasize the development of focused attention and present-moment awareness (Barros et al., 2015). When applied to sensory sensations such as taste and smell, mindfulness training can help people fully engage with and enjoy these indicators (Paletta et al., 2020). This increased sensitivity may also extend to chemosensory signals, making people more sensitive to subtle odors and tastes in their surroundings (Paletta et al., 2020). However, it is notable that only a limited number of studies incorporating mindfulness training have utilized both objective and subjective measurements to evaluate the influence of mindfulness on olfaction, and the perception of taste.

The current virtual reality (VR) solution has been painstakingly designed to coincide with the processes inherent in mindfulness practices. It is intended to specifically engage participants’ positive moods, enhance their sensitivity, and focus their attention on olfactory and taste perceptions by incorporating cues related to natural surroundings, such as plants, landscapes, bodies of water, and various scents (for further details, please refer to “Methods: Intervention” section).

The significance of this study lies in its holistic approach, addressing both mental health and sensory experiences through an innovative use of VR technology. By integrating natural elements and mindfulness practices into an immersive virtual environment, this research offers a novel method for improving well-being among university students. The findings are expected to contribute valuable insights into the role of sensory perceptions in mental health and provide a practical, accessible solution for addressing the increasing mental health challenges faced by students.

This study aimed to assess the effectiveness of a VR-based psychological intervention in reducing symptoms of anxiety, depression, and rumination while improving mindfulness, olfactory perception, sensory imagery, and chemosensory perception in a sample of university students with anxiety symptoms, while also taking into account the influence of study design and participant-related covariates. In addition, to better understand participants’ overall experience with the VR intervention and gather actionable insights to inform future iterations of the intervention, we will conduct interviews to gather participants’ feedback and perspectives about the intervention following the session.

The following study hypotheses are formulated:

Hypothesis 1: The VR-based mindfulness intervention can immediately reduce participants’ anxiety symptoms, depression symptoms, and rumination, while increasing participants’ mindfulness, olfactory discrimination, sensory image, and chemosensory abilities.

Hypothesis 2: One week following the intervention, the effect of the intervention on depression symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and rumination will be maintained, as will the improvement in mindfulness, olfactory discrimination, sensory image, and chemosensory ability.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The present study was approved by the ethical review board of the Ethical Committee of the Department of Psychology at the South China Normal University (Reference No.: SCNU-PSY-152). A total of 51 university students with anxiety symptoms and low mood were recruited via both research participant platforms and school notice boards at institutions around Guangzhou City, China. Participants must be: (1) full-time university students; (2) have experienced low mood and anxious symptoms (i.e., concerns, worry, stress) during the last month; (3) proficient Chinese language users; and (4) are not currently undertaking psychotherapies (including mindfulness training). Participants were excluded from this intervention study who: (1) lived with a specific phobia (i.e., three-dimensional VR environment; natural environment, animal, height); (2) had been diagnosed with severe mental disorders (i.e., Major Depressive Disorder; Mania, Schizophrenia, Somatic and Disassociation Disorder); (3) have been taking antidepressants regularly for over 1 month; (4) smokers.

In this study, we adopted a mixed methods research design, integrating both quantitative and qualitative data to provide a comprehensive understanding of the impact of the VR-based mindfulness intervention. The theoretical models guiding this integration are triangulation and complementarity, combined with thematic analysis for qualitative data interpretation. Triangulation involves using multiple data sources to validate findings, enhancing the overall reliability of the results (Carter et al., 2014). Complementarity was employed to explore how quantitative and qualitative data reveal different aspects of the same phenomenon (Bazeley, 2018). In this study, quantitative data, collected through standardized measures of anxiety, depression, mindfulness, and sensory perceptions, provided objective assessments of the intervention’s effectiveness. To complement these results, we conducted one-on-one semi-structured interviews and used thematic analysis to identify recurring themes that reflected participants’ experiences with the intervention.

A quasi-experimental design was employed with one group of participants serving as their control with repeated measurements. A single group of participants in the present study were delivered a VR-based intervention and measured at three time points: the baseline pre-intervention test (T1), post-intervention test (T2), and one-week follow-up test (T3). This within-subject approach allowed for a comprehensive exploration of changes within the same group across the various stages of the study. Notably, the baseline phase served as a crucial control condition, facilitating a nuanced assessment of alterations in measured outcomes before and after the intervention.

Potential participants indicated their interest through online registration, which was subsequently verified by the researcher to confirm their eligibility. A total of 49 participants (male = 10) visited the VR lab and participated in the research. Participants read the research information sheet and consented to their participation before baseline measurements. The included participants were given a gift package value of ¥30 for compensation. The demographic information characteristics are described in Table 1.

Baseline assessments of anxiety, mindfulness, depression, rumination, and olfactory sensations were conducted. After a 20-min VR intervention, participants completed an olfactory sensation test and an online questionnaire. The post-intervention follow-up was administered 1 week after the intervention. Participants were invited to fill out the same online questionnaire they were measured in T1 and T2. Due to the olfactory test lab’s limited accessibility, participants’ objective olfactory was only collected at T1 and T2.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted after the intervention as complementary evidence to support quantitative results. The content of the interviews was explored by thematic analysis, allowing us to capture the complexity of sensory perceptions, emotional shifts, and practical challenges in the intervention.

Measurements

Demographic information

Questions regarding demographic variables including gender, age, educational level (grade), ethnicity, mental health status, and treatment history regarding anxiety and depression (if any), were also recorded.

Olfactory discrimination is a well-established object measurement to investigate one’s olfactory ability to discriminate between different odors (Hummel et al., 1997). This Sniffin’ Sticks-like tool was assessed using a triplet-based method where participants identified the differing scents among three odorants. Triplets were selected based on factors like odor intensity and hedonic similarity. Each odor was sampled once per participant. Triplets were presented within 30-s intervals, with individual presentations separated by 3 s.

Mindfulness

The Chinese Version of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS) was used to assess participants’ mindfulness changes over time (Deng et al., 2012). MAAS employs a five-point Likert scale. Participants are presented with a series of statements and are asked to rate the extent to which each statement applies to them, ranging from “Almost Always” to “Almost Never.” This scale allows individuals to indicate the frequency with which they engage in mindful behaviors and their ability to maintain present-moment awareness. MAAS exhibits good psychometric properties (α = 0.83). It has also been widely used across a range of different samples. The reliability of MAAS in the current sample is high (T1: α = 0.82; T2: α = 0.89; T3: α = 0.92).

Depression

Chinese version of Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) was employed to measure participants’ fluctuations in depressive symptoms across the study period (Shek, 1990). BDI employs a four-point Likert scale. Respondents assess the intensity of their feelings regarding various statements, spanning from “Not at all” to “Severely.” This scale facilitates the expression of their emotional experiences and levels of depression. The BDI demonstrates robust psychometric properties (α = 0.86), establishing its reliability and validity (Shek, 1990). The reliability of BDI in the current sample is high (T1: α = 0.85; T2: α = 0.91; T3: α = 0.92).

Anxiety

The Chinese Version of the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) was employed to assess participants’ variations in anxiety levels throughout the study duration (Pang et al., 2019). BAI employs a four-point Likert scale. Participants evaluate the severity of their emotions in response to specific statements, ranging from “Not at all” to “Severely.” This scale provides a means to capture their anxious feelings and levels. The BAI demonstrates strong psychometric characteristics (α = 0.80), affirming its reliability and validity. Furthermore, the BAI has been widely applied across diverse participant cohorts (Garcia et al., 2021; Williams et al., 2012). The reliability of BAI in the current sample is high (T1: α = 0.92; T2: α = 0.89; T3: α = 0.90).

Rumination

The Chinese version of the Rumination Response Scale (RRS) was used to examine changes in participants’ rumination tendencies during the course of the study. RRS is a 10-item questionnaire with a five-point Likert scale, which shows good psychometric properties in Chinese university students sample (He et al., 2021). Participants evaluate the frequency of their responses to ruminative thoughts, ranging from “Almost Never” to “Almost Always.” The Chinese RRS shows robust psychometric properties (α = 0.82), affirming its reliability and validity. The reliability of RRS in the current sample is high (T1: α = 0.89; T2: α = 0.92; T3: α = 0.95).

Sensory imagery

The Plymouth Sensory Imagery Questionnaire (Psi-Q) was utilized to assess participants’ sensory imagery experiences during the study period. Psi-Q utilizes a rating scale ranging from 0 to 10 (Andrade et al., 2014). Participants provide ratings for the vividness of their sensory imagery across diverse domains, encompassing a scale from 0 (no imagery at all) to 10 (the imagery is as clear and vivid as it really feels). This scale affords insights into participants’ capacity for engaging in sensory imagery. The Chinese Psi-Q has yet to be recognized, and the backup translation was created by two separate researchers who are fluent in both English and Chinese and translated the original version to Chinese. The reliability of BDI in the current sample is high (T1: α = 0.95; T2: α = 0.94; T3: α = 0.97).

Chemosensory

This study adopted the Chinese version of the Chemosensory Pleasure Scale (CPS-C) to measure participants’ hedonic capabilities connected to smell and taste (Zhao et al., 2019). This scale is reliable (α = 0.93) and consists of three independent factors: food, imagination, and nature, which assess the individual’s ability to derive pleasure from eating, anticipate food, and feel pleasure through the sense of smell, in that order. Items were assessed on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not applicable to me) to 6 (very applicable to me). Lower scores on the scale imply a greater possibility of the individual having impaired hedonic smell and taste skills. The reliability of CPS-C in the current sample is high (T1: α = 0.80; T2: α = 0.83; T3: α = 0.90).

Participants’ feedback and perspective on intervention

Participants were invited to participate in an interview following the intervention to explore their general experience, feelings, and feedback on the intervention. The subsequent test included two open-ended questions: (1) Please provide your comments on the intervention, including its strengths and weaknesses. (2) Do you have any suggestions for improving this intervention?”

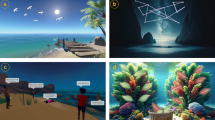

Intervention

The VR intervention is powered by a PICOS VR headset, comprised of two immersive video sets: one featuring natural environments and another providing instructional guidance for mindful stress reduction, free association, and relaxation techniques. A team of accomplished psychologists and therapists developed the video content, drawing on the Attention Restoration Theory and Stress Reduction Theory’s insights into the cognitive benefits of natural environment exposure. These videos incorporated mindfulness practices, including nonjudgmental awareness and present-moment focus, coupled with controlled breathing during body scanning exercises for mindful observation of natural surroundings. Participants engaged in free association exercises to reflect on recent experiences, followed by relaxation and mindfulness practices aimed at enhancing self-compassion and emotional tranquillity.

The video materials for the VR intervention were sourced from Storyblocks and were subject to copyright protection. Content presentation in the VR environment was meticulously tailored, aligning with principles of mindfulness, free association, and relaxation practices set against natural backdrops. The VR psychological intervention, spanning approximately 20 min, encompassed 30 distinct scenes (see Appendix 1).

Though the current virtual reality (VR) intervention is based on passive interaction rather than active interaction with boating and other activities, the natural videos are mostly three-dimensional (except for transitional phases), allowing participants to be more immersive and look around the environment (Yeo et al., 2020), and encouraging them to be more engaged in the intervention rather than being distracted by other noises or visual stimuli in the lab. Moreover, VR offers highly realistic immersive experiences, with studies indicating that the level of realism influences affective responses. VR can evoke positive affective responses comparable to real natural scenes, and environments with high realism enhance the sense of presence and restoration. This addresses the importance of realism, especially in environmental restoration research using VR (Newman et al., 2022).

The intervention’s overarching goal is to lead participants toward mindfulness and exposure to real natural environments, as opposed to computer-generated simulations, drawing from the Attention Restoration Theory. The aim is to evoke feelings of fascination and effortless attention through the immersive VR headset, ultimately enhancing positive mood and alleviating stress and anxiety symptoms.

Data analysis

For data analysis, SPSS 26.0 was employed. The findings of the pre-test and post-test were compared on a statistically significant level, which is defined as a p-value less than 0.05. The normality test was performed on all data groups to select the most suitable data analysis technique from the t-test and nonparametric test. In the absence of a parametric test, a nonparametric test (Wilcoxon Signed Ranks Test/or Friedman test) was utilized, whereas the One-way ANOVA was used to evaluate the changes of normally distributed variables over three time points. Descriptive data was reported using score or rank means and standard deviation. Cronbach’s alpha was determined for all scale scores at each collection timepoint to confirm the sample’s internal consistency.

For the content of the post-intervention interviews, Thematic Analysis served as the primary method for analyzing the qualitative data. This analytic approach, grounded in Braun and Clarke’s (2006) framework, is a flexible method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) within qualitative data. Thematic analysis allows for a detailed and nuanced understanding of participants’ perspectives, which is particularly useful for interpreting how individuals experience and engage with complex interventions like VR-based mindfulness.

The process of thematic analysis involves several key phases: (1) Familiarization with the data by reading and re-reading interview transcripts; (2) Generating initial codes by identifying meaningful segments in the data related to participants’ experiences with the intervention; (3) Searching for themes by collating codes into broader categories, such as easeful feeling, auditory pleasure, and mindset change; (4) Reviewing themes to ensure they accurately represent the data; (5) Defining and naming themes, ensuring clarity and coherence for the final analysis; (6) Producing the report, which integrates these themes into the broader findings of the study.

Thematic analysis provides the flexibility to explore both anticipated and emergent themes, making it especially suitable for capturing the complex interactions between mindfulness, sensory experiences, and emotional regulation in a VR-based intervention.

Results

A total of 49 college students consented to participate in the study. Since it is a single intervention, participants’ mental health outcomes were measured immediately before (T1) and after (T2) the VR session, and only one participant’s data was missed at T2. After a week (T3), the researcher sent the follow-up questionnaire (using the online questionnaire platform) to the participants with a response rate of 96% (47/49).

Sample characteristics

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants. Among them, 10 (20%) participants were male and 39 (80%) were female. One participant did not provide the researchers with further demographic information. The mean age of the participants was 22.06 (SD = 4.56). Two students identified themselves as ethnic minorities. One student received psychotherapy in the past 6 months. Moreover, none of them reported a history of taking antipsychotic drugs within 6 months.

The results of the dependent variables’ normality tests are presented in Table 2. The Shapiro–Wilk test revealed that most dependent variables were normally distributed (p > 0.05). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to assess the effect of the intervention on olfactory experience for both normally distributed and non-normally distributed data.

The effectiveness of the intervention

Overall, statistical results revealed significant effects of the intervention on the improvement of olfactory sensation, trait mindfulness, depression, anxiety, sensory imagery, and the hedonic capacity for smell and taste pleasure. However, the intervention had a nonsignificant impact on rumination (see Table 3).

Olfactory sensation

A Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to examine changes in the olfactory sensation and showed a significant increase from pre- to post-intervention (Z = 2.834, p = 0.005), suggesting a significant improvement in participants’ olfactory sensitivity after the intervention (see Fig. 1).

Trait mindfulness

From pre-intervention to follow-up, a one-way repeated measures ANOVA presented a statistically significant increase in trait mindfulness (F(2,47) = 7.148, p = 0.002), meaning that VR-based intervention can significantly improve participants’ mindfulness over time. Additionally, no significant changes were found from the T2 to the T3 follow-up timepoint (t = 0.152, p = 0.880), implying that the effect of the intervention has been maintained one week after the intervention (see Fig. 1).

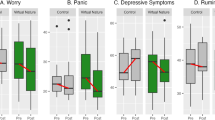

Depression

A Friedman test showed a significant decrease from pre-intervention to follow-up timepoint in the depression level of the participants (χ2(2) = 43.772, p < 0.001). It indicates that the VR-based intervention effectively reduced participants’ depression levels. Furthermore, no significant changes have been detected from post-intervention to follow-up (U = 0.556, p > 0.05), suggesting that the impact of the intervention has been sustained one week after its implementation (see Fig. 2).

Anxiety

Similarly, the Friedman test’s results showed that participants’ anxiety levels decreased significantly after the intervention (χ2(2) = 27.605, p < 0.001). Additionally, the effect of the intervention on anxiety was maintained after the post-intervention to the follow-up timepoint (U = 1.616, p = 0.318) (see Fig. 3).

Rumination

Friedman test result showed that the effect of the intervention on rumination was not significant after the intervention (χ2(2) = 4.905, p = 0.086), suggesting that the VR-based intervention did not lead to a reduction in participants’ rumination following the intervention. However, the mean scores of rumination reduced from pre-intervention to post-intervention and to follow-up (see Fig. 4).

Sensory imagery

There was a significant improvement in sensory imagery when changes were examined by the one-way repeated measures ANOVA (F(2,47) = 9.522, p < 0.001). Furthermore, no significant changes were found from post-intervention to follow-up timepoint (t = −1.105, p = 0.275), suggesting that this improvement has been sustained for one week since its implementation (see Fig. 4).

Chemosensory

A one-way repeated measures ANOVA result revealed that the hedonic capacity for smell and taste pleasure improved significantly (F(2,47) = 10.869, p < 0.001). However, no tendency was found that there was a further improvement in the hedonic capacity for smell and taste pleasure from post-intervention to one-week follow-up (t = −3.818, p < 0.001) (see Fig. 4).

Qualitative thematic analysis

Twenty semi-structured interviews were conducted after the intervention as complementary evidence to complement quantitative results, exploring participants’ experiences and perspectives. Through thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke, 2006), seven key themes were identified regarding feelings and perspectives for the intervention. Among them, five themes were identified to reflect participants’ positive perspectives: (1) Easeful Feeling, (2) Auditory Pleasure, (3) Sleep Aid, (4) Mindset Change, and (5) Physical Relaxation, while two themes were identified for further improvements of the intervention design: (6) Limited Screen and (7) Poor Transition. The description, frequency, and quotes of these themes are shown in Table 4.

Participants frequently reported feeling comfortable, relaxed, and calm while immersed in the virtual nature environment. Easeful Feeling and Auditory Pleasure reflected participants’ immediate psychological relief, which aligns with the reduction in anxiety symptoms and improved mood. The theme of Easeful Feeling, with 75% of participants expressing relaxation and calmness, supports the quantitative findings, indicating a significant reduction in anxiety and rumination. Similarly, Auditory Pleasure (45%) highlights the sensory experience of nature sounds contributing to mindfulness and calm, reinforcing the importance of sensory stimuli in mental health improvement.

Participants noted experiencing restful sleepiness during the intervention, likely due to the relaxation effects of the virtual nature and mindfulness practices. This theme illustrates how the intervention not only reduces mental fatigue but also promotes physical relaxation, further supporting its broader impact on well-being.

Mindset Change demonstrates how participants experienced a shift in thinking, reflecting improved mindfulness and emotional regulation. This theme (50% of participants) demonstrates cognitive shifts post-intervention, supporting the hypothesis that VR-enhanced mindfulness leads to better emotional regulation and mindfulness.

Participants’ experiences of Physical Relaxation (35%) highlight increased bodily awareness and mindfulness, aligning with the predicted long-term improvements in sensory perceptions and relaxation post-intervention. This theme shows how participants learned to connect their bodily sensations with relaxation, which ties into the hypothesis about mindfulness and sensory perception improvements, suggesting long-term effects on bodily awareness.

While the intervention successfully improved participants’ mental states, feedback on Limited Screen (35%) and Poor Transition (20%) underscores areas for enhancement. The Limited Screen feedback highlights a key limitation of the intervention’s technical design, suggesting that enhancing the immersive quality of the VR experience is crucial for optimizing psychological engagement and outcomes. Participants identified issues with abrupt transitions between video and audio segments, which disrupted the flow of the experience and reduced immersion. These issues, which limit immersion, highlight the importance of optimizing the VR experience for better engagement and psychological outcomes.

Discussion

General discussion

Anxiety and depression symptoms of Chinese University students may develop due to academic pressure and relationship issues. However, insufficient mental health services restrict them from being treated or referred to professional assistance (Charlson et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2022). Therefore, the current study focuses on developing a cost-effective and self-help mental health intervention to bridge the existing treatment gap. The outcomes of the study reveal that the intervention led to improvements across all measured variables, except rumination, which showed no significant change. This indicates that while the intervention was generally effective, its influence on reducing ruminative thoughts requires further attention. Specifically, the VR-based mindfulness intervention significantly reduces depression and anxiety symptoms of stressed university student, while promoting their mindfulness, olfactory sensations, and chemosensory perceptions.

The symptoms improvement of university students is consistent with previous studies which demonstrated the effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Interventions (MBIs) in treating depression and anxiety symptoms (Modrego-Alarcón et al., 2021; Yildirim and O’Grady, 2020; D. Zhang et al., 2021; Johnson et al., 2023). Furthermore, research that combined mindfulness with VR led to a higher level of mindfulness (Yildirim and O’Grady, 2020). Based on these findings, our study incorporated mindfulness practices (including attention shifting, present-moment awareness, body scanning, breathing exercises, sensory expansion, and cultivation of positive affect) within a VR-provided nature setting, significantly reducing depression and anxiety symptoms among university students and filling in research gaps in anxiety symptoms in the current population. However, rumination has not been intervened significantly. It is attributed to rumination patterns, a long-term and stable personality trait, that cannot be improved effectively by single-session intervention (Baer and Sauer, 2011).

In addition to mental indicators, it is important to incorporate body sensation indicators, such as body scanning and expanded senses, into mindfulness interventions study; however, there are few explorations of participants’ sensory perceptions in relevant studies (Ma et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2023). Only a few studies have specifically investigated the effects of meditation on olfactory discrimination. Although there is no significant difference statistically, some of the participants in the mindfulness group reflected an increased odor awareness (Mahmut et al., 2021). Notably, the present study discovered that VR-based mindfulness interventions in virtually natural environments can effectively improve olfactory sensations, sensory perception, and chemosensory experiences, proving the advanced effectiveness of the current intervention and contributing to the existing body of knowledge.

Hypothesis two of this study proposed the levels of mindfulness, depression, anxiety symptoms, and sensory imagery one week after the intervention. Results concluded that the positive mental effects can remain for up to one week, despite participants engaging in the intervention only once. However, the degree of chemosensory perception showed a significant decrease in one week, but it was still higher than the pre-intervention test. The failure to maintain the effect of intervention can be explained by external stressors, responsiveness, environmental influences, and the absence of ongoing mindfulness practice.

The qualitative findings from post-intervention interviews provide valuable real-world confirmation of the intervention’s benefits, reinforcing the quantitative results. The majority of participants reported feeling more easeful and relaxed both mentally and physically in natural setting during the intervention, which is consistent with the scale results and the previous studies, filling the research gap on physical sensations after intervention as well (Sadowski et al., 2020; Kaplan-Rakowski et al., 2021; Modrego-Alarcón et al., 2021; Sadowski and Khoury, 2022; Failla et al., 2022). Specifically, the Easeful Feeling theme emerged as a prominent reflection of the intervention’s success in reducing anxiety and promoting calm. This qualitative insight aligns directly with the quantitative data, which demonstrated significant reductions in anxiety and depression levels post-intervention. These experiences also extend the quantitative results by highlighting the physical sensations of relaxation, which are often underreported in traditional mental health metrics. By focusing on the embodied experience of mindfulness, this study addresses a gap in existing research on physical sensations during mindfulness practices (Sadowski et al., 2020; Kaplan-Rakowski et al., 2021).

The theme of Auditory Pleasure, reported by 45% of participants, further supports the sensory benefits of the intervention, complementing the quantitative findings related to improvements in sensory perceptions, particularly olfaction and sensory imagery. Participants emphasized the soothing effects of natural sounds, such as rain and flowing water, which not only enhanced their mindfulness experience but also contributed to emotional regulation and mood improvement. These qualitative insights confirm the importance of multisensory engagement in mindfulness practices and support the theoretical underpinnings of sensory-based mental health interventions (Failla et al., 2022).

Additionally, the Mindset Change theme, where half of the participants reported cognitive shifts, provides further evidence of the intervention’s ability to foster emotional regulation and self-awareness. This theme aligns with the quantitative improvements in mindfulness and emotional clarity, offering a deeper understanding of how the intervention facilitates reflective thinking and emotional processing. The qualitative feedback highlights participants’ ability to reorganize their emotions and reduce rumination, thereby complementing the observed reductions in anxiety and depression.

Moreover, depending on the emotional coping strategies, individuals felt a differentiated experience of mood improvement based on their situation. At the same time, half of the participants felt drowsy in a cozy way. Consistent with the findings from prior research advocating relaxation exercises and nature sounds for sleep assistance (De Niet et al., 2009; Debellemaniere et al., 2018; Beck et al., 2021; Johnson, 2023), the current study provides evidence to support further research to corroborates our intervention with language-guided relaxation guidance to enhance sleep quality.

While the qualitative themes provide robust support for the intervention’s effectiveness, they also identify specific areas for improvement. The Limited Screen and Poor Transition themes highlight technological limitations that affected participants’ sense of immersion. These feedback points, though critical, are not inconsistent with the positive outcomes, but rather provide direction for refining the intervention to maximize its benefits.

In summary, the qualitative themes not only validate the quantitative results but also extend our understanding of the intervention’s impact by highlighting participants’ personal and sensory experiences.

Strengths, limitations and further directions

The present study has several strengths. First, it demonstrates a comprehensive understanding of the rationale and theoretical framework that underpins the integration of mindfulness practices within a virtual reality environment, emphasizing the importance of incorporating visual stimuli featuring natural settings during mindfulness exercises. Additionally, this study provides explicit instructions and intervention content that can serve as a valuable resource for other researchers and clinical practitioners. Second, the present study effectively measures mindfulness and rumination, whereas some previous research on VR-based mindfulness interventions focused solely on depression, anxiety, and mood without assessing these specific outcomes (Failla et al., 2022; Modrego-Alarcón et al., 2021). This study demonstrates the sustained improvement in mindfulness following the intervention, highlighting the significance of mindfulness within this intervention context. Third, this study assesses both objective and subjective facets of sensory variables, aligning with the mindfulness practice’s core objectives. The research validates the notably positive impact of VR-based mindfulness intervention on participants’ olfactory discrimination, sensory imagery, and hedonic capacity related to smell and taste pleasure. Subsequent studies can draw upon these insights, advocating for the adoption of VR-based interventions with immersive environments as a time-efficient, accessible, and supportive tool for university students alleviating anxiety and depressive symptoms and improving sensory awareness in everyday settings, thereby promoting better mental health outcomes.

Moreover, the present study included students experiencing a wide range of mental health issues, from mild distress to more severe symptoms, without the need for formal diagnostic criteria. This focus on symptomatology (specifically anxiety and depression symptoms) rather than formal clinical diagnoses ensures that the intervention is relevant and applicable to the broader student population, which often suffers from emotional distress without necessarily seeking clinical treatment.

In addition, qualitative data revealed participants’ feelings and perspectives on the intervention. It is essential to reflect on the explanations of indicators changing from the participants’ perspective. It not only provides more possible views to understand the mechanism of intervention but also helps researchers gain feedback for future improvement of the intervention.

Several limitations were identified in the current study, including the absence of control groups, the use of a single session for the intervention, and challenges in establishing causality regarding the intervention’s effects. However, it is essential to acknowledge that this study serves as an intervention investigation, primarily designed to generate preliminary insights into the impacts of the newly developed VR-based mindfulness program. Given the ethical considerations and the exploratory nature of the research, the decision to conduct randomized controlled trials (RCTs) is more fitting once the feasibility and potential usefulness of the intervention have been established.

Future studies are encouraged to address these limitations by increasing participant recruitment and using more rigorous research methods, such as RCTs, to test the effectiveness of this intervention fully. This approach will provide a stronger foundation for drawing causal inferences and making informed decisions about the utility of VR-based mindfulness interventions in addressing mental health concerns. Furthermore, considering the typical duration of formal mindfulness-based interventions, which typically span 8 weeks (Zhang et al., 2021), it is advisable to increase the frequency of the VR-based mindfulness sessions and determine the optimal dosage for this intervention. Since the current study only involved a single session of the intervention, the follow-up assessments were limited to a one-week timeframe. Future studies could benefit from extending the follow-up period to three months and even six months to evaluate the long-term effects of the intervention. For VR images and content design, it is recommended to adopt a more realistic 3D surround environment rather than a 2D scene. Also, a softer and slower way of video and audio transition should be used during scene transitions to reduce the possibility of distraction or interruption of participants’ attention.

Additionally, regarding participants’ gender, age and ethnicity, the current study’s gender diversity is limited, as seen by the inclusion of only 10 male participants, making the findings more directly applicable to the female university student group. According to a longitudinal research in China (N = 1892), female university students are more likely to suffer from anxiety than male students (Gao et al., 2020). Furthermore, the inclusion of only two minority students suggests that the observed results may be most relevant to Han Chinese university students. To improve the generalizability of findings, prospective large-scale studies should include a more diverse ethnic composition of students and include gender as a covariant in the data analysis, ensuring that the intervention’s efficacy extends to a broader range of university students.

In terms of age, participants’ average age of 22 reflects a dominating undergraduate student presence. Subsequent research projects should seek more inclusion by involving a larger cohort of postgraduate and senior students, resulting in a more nuanced and complete knowledge of the intervention’s impact. As previous research has shown that nature interventions are more effective in urban residents than in rural areas, it is worth noting that, while not measured in the current study, all participating students stayed on urban campus with limited access to natural resources. This promotes the evaluation of living circumstances and access to nature as potentially important covariates. Subsequent studies should integrate careful measurement and study of these factors to improve our knowledge of their effect on intervention results.

In summary, future empirical investigations, building upon the foundation laid by the current study, should consider the following recommendations: (1) Employ a randomized controlled trial (RCT) design with three groups, including the intervention group, an audio-led mindfulness group, and a waiting list control group, to rigorously evaluate the effects of the intervention on participants’ depression, anxiety, mood, sensory perceptions, and other relevant health-related outcomes. (2) Conduct replication studies in diverse university populations to assess the generalizability and validity of the intervention’s effects across different demographic groups. (3) Implement multiple sessions of the intervention to enhance and consolidate the positive effects observed, ensuring a more robust and lasting impact on participants’ mental health; (4) Take age, gender, ethnicity, and present living circumstances into consideration as covariants to determine how these characteristics impact the intervention’s effectiveness.

Overall, the study has limitations, however, framing the study’s narrative within the context of the particular obstacles faced by university students increases the findings’ broader relevance. Instead, it emphasizes the significance of adapting treatments to specific demographic requirements. Recognizing the different pressures encountered by university students aids in creating tailored and effective mental health solutions that may be applied to other populations.

Conclusion

This research presents initial evidence of the notable positive impacts of a brief VR-based mindfulness intervention on university students in China who are living with mental health issues. University students experiencing anxiety symptoms could potentially benefit from this virtual reality (VR) intervention. This includes immersing people in finely realistic virtual surroundings with natural landscapes, leaves, and flowers, while also leading them through mindfulness activities. The intervention effectively reduced sadness and anxiety while also improving mindfulness, olfaction, sensory imagery, and chemosensor. Moreover, the intervention maintained a positive effect on the above-measured outcomes for one week, except for rumination and chemosensory. Further study might have benefited from the use of robust randomized control trials to confirm these findings. Nonetheless, this study highlights the potential of virtual reality-based mindfulness therapies in educational and mental health settings, providing essential tools to ease the psychological issues experienced by worried university students and giving timely help to this vulnerable group.

Data availability

Research data is open to the public and uploaded as a supplementary file.

References

Andrade J, May J, Deeprose C et al. (2014) Assessing vividness of mental imagery: the Plymouth sensory imagery questionnaire. Br J Psychol 105(4):547–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjop.12050

Aron EN, Aron A (1997) Sensory-processing sensitivity and its relation to introversion and emotionality. J Pers Soc Psychol 73(2):345–368. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.2.345

Asif S, Mudassar A, Shahzad TZ, Raouf M, Pervaiz T (2020) Frequency of depression, anxiety and stress among university students. Pak J Med Sci 36(5):971–976. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.36.5.1873

Aspy DJ, Proeve M (2017) Mindfulness and loving-kindness meditation: effects on connectedness to humanity and to the natural world. Psychol Rep 120(1):1

Athanassi A, Dorado Doncel R, Bath KG, Mandairon N (2021) Relationship between depression and olfactory sensory function: a review. Chem Senses 46:bjab044. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjab044

Baer RA, Sauer SE (2011) Relationships between depressive rumination, anger rumination, and borderline personality features. Pers Disord Theory Res Treat 2(2):142–150. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019478

Bazeley P (2018) Integrating analyses in mixed methods research. Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526417190

Barros VVde, Kozasa EH, Souza ICWde, Ronzani TM (2015) Validity evidence of the Brazilian version of the Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS). Psicol Reflex Crít 28(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1590/1678-7153.201528110

Beck J, Loretz E, Rasch B (2021) Exposure to relaxing words during sleep promotes slow-wave sleep and subjective sleep quality. Sleep. https://doi.org/10.1093/sleep/zsab148

Burdea GC, Coiffet P (2003) Virtual reality technology. John Wiley & Sons

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual res psychol 3(2):77–101

Carter N, Bryant-Lukosius D, DiCenso A, Blythe J, Neville AJ (2014) The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncol Nurs Forum 41(5):545–547. https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.545-547

Charlson FJ, Baxter AJ, Cheng HG et al. (2016) The burden of mental, neurological, and substance use disorders in China and India: a systematic analysis of community representative epidemiological studies. Lancet 388(10042):10042. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30590-6

Chen X, Guo W, Yu L, Luo D, Xie L, Xu J (2021) Association between anxious symptom severity and olfactory impairment in young adults with generalized anxiety disorder: a case–control study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 17:2877–2883. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S314857

Cieślik B, Mazurek J, Rutkowski S et al. (2020) Virtual reality in psychiatric disorders: a systematic review of reviews. Complement Ther Med 52:102480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2020.102480

Cikajlo I, Cizman Staba U, Vrhovac S et al. (2017) A cloud-based virtual reality app for a novel telemindfulness service: rationale, design and feasibility evaluation. JMIR Res Protoc 6(6):e108. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.6849

Damen KHB, Van Der Spek ED (2018) Virtual reality as e-Mental Health to support starting with mindfulness-based cognitive therapy. In: Clua E, Roque L, Lugmayr A, Tuomi P (eds) Entertainment computing—ICEC 2018, vol 11112. Springer, pp. 241–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99426-0_24

De Niet G, Tiemens B, Lendemeijer B, Hutschemaekers G (2009) Music‐assisted relaxation to improve sleep quality: meta‐analysis. J Adv Nurs 65(7):1356–1364. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2009.04982.x

Debellemaniere E, Gomez-Merino D, Erblang M, Dorey R, Genot M, Perreaut-Pierre E, Pisani A, Rocco L, Sauvet F, Léger D, Rabat A, Chennaoui M (2018) Using relaxation techniques to improve sleep during naps. Ind Health 56(3):220–227. https://doi.org/10.2486/indhealth.2017-0092

Deng Y-Q, Li S, Tang Y-Y et al. (2012) Psychometric properties of the Chinese translation of the mindful attention awareness scale (MAAS). Mindfulness 3:10–14

Dinh HQ, Walker N, Hodges LF et al. (1999) Evaluating the importance of multi-sensory input on memory and the sense of presence in virtual environments. In: Proceedings IEEE Virtual Reality (Cat. No. 99CB36316). pp. 222–228. https://doi.org/10.1109/VR.1999.756955

Djernis D, Lerstrup I, Poulsen D et al. (2019) A systematic review and meta-analysis of nature-based mindfulness: effects of moving mindfulness training into an outdoor natural setting. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(17):17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16173202

Duffy A, Saunders KEA, Malhi GS et al. (2019) Mental health care for university students: a way forward? Lancet Psychiatry 6(11):885–887. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30275-5

Failla C, Marino F, Bernardelli L et al. (2022) Mediating mindfulness-based interventions with virtual reality in non-clinical populations: the state-of-the-art. Healthcare 10(7):1220. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare10071220

Falconer CJ, Rovira A, King JA et al. (2016) Embodying self-compassion within virtual reality and its effects on patients with depression. BJPsych Open 2(1):74–80. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjpo.bp.115.002147

Flavián C, Ibáñez-Sánchez S, Orús C (2021) The influence of scent on virtual reality experiences: the role of aroma-content congruence. J Bus Res 123:289–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.09.036

Gao L, Xie Y, Jia C, Wang W (2020) Prevalence of depression among Chinese university students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep 10(1):15897. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72998-1

Gao W, Ping S, Liu X (2020) Gender differences in depression, anxiety, and stress among college students: a longitudinal study from China. J Affect Disord 263:292–300

Garcia JM, Gallagher MW, O’Bryant SE, Medina LD (2021) Differential item functioning of the Beck Anxiety Inventory in a rural, multi-ethnic cohort. J Affect Disord 293:36–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.005

Geiger PJ, Boggero IA, Brake CA et al. (2016) Mindfulness-based interventions for older adults: a review of the effects on physical and emotional well-being. Mindfulness 7(2):296–307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0444-1

Giachos D, Paschali M, Datko MC et al. (2022) Characterizing nature videos for an attention placebo control for MBSR: the development of nature-based stress reduction (NBSR). Mindfulness 13(6):1577–1589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01903-w

Gál É, Ștefan S, Cristea IA (2021) The efficacy of mindfulness meditation apps in enhancing users’ well-being and mental health related outcomes: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Affect Disord 279:131–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.134

Hanley AW, Derringer SA, Hanley RT (2017) Dispositional mindfulness may be associated with deeper connections with nature. Ecopsychology 9(4):225–231. https://doi.org/10.1089/eco.2017.0018

He J, Liu Y, Cheng C, Fang S, Wang X, Yao S (2021) Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the 10-item ruminative response scale among undergraduates and depressive patients. Front Psychiatry 12:626859. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.626859

Huang Y, Wang Y, Wang H et al. (2019) Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry 6(3):3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30511-X

Hummel T, Sekinger B, Wolf SR et al. (1997) ‘Sniffin’ Sticks’: olfactory performance assessed by the combined testing of odour identification, odor discrimination and olfactory threshold. Chem Senses 22(1):39–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/22.1.39

Hysenbegasi A, Hass SL, Rowland CR (2005) The impact of depression on the academic productivity of university students. J Ment Health Policy Econ 8(3):145–151

Johnson BT, Acabchuk RL, George EA et al. (2023) Mental and physical health impacts of mindfulness training for college undergraduates: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Mindfulness. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-023-02212-6

Johnson D (2023) A good night’s sleep: three strategies to rest, relax and restore energy. J Interprof Educ Pract 30:100591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xjep.2022.100591

Kaplan S (1995) The restorative benefits of nature: toward an integrative framework. J Environ Psychol 15(3):3. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-4944(95)90001-2

Kaplan-Rakowski R, Johnson KR, Wojdynski T (2021) The impact of virtual reality meditation on college students’ exam performance. Smart Learn Environ 8(1):21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-021-00166-7

Kohli P, Soler ZM, Nguyen SA, Muus JS, Schlosser RJ (2016) The association between olfaction and depression: a systematic review. Chem Senses 41(6):479–486. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjw061

Lattie EG, Lipson SK, Eisenberg D (2019) Technology and college student mental health: challenges and opportunities. Front Psychiatry 10:246. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00246

Lee M, Lee SA, Jeong M, Oh H (2020) Quality of virtual reality and its impacts on behavioral intention. Int J Hosp Manag 90:102595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102595

Lefranc B, Martin-Krumm C, Aufauvre-Poupon C, Berthail B, Trousselard M (2020) Mindfulness, interoception, and olfaction: a network approach. Brain Sci 10(12):921. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci10120921

Ma J, Zhao D, Xu N, Yang J (2023) The effectiveness of immersive virtual reality (VR) based mindfulness training on improvement mental-health in adults: a narrative systematic review. Explore 19(3):3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.explore.2022.08.001

Mac A, Kim M-K, Sevak RJ (2024) A review of the impact of sensory processing sensitivity on mental health in university students. Ment Health Clin 14(4):247–252. https://doi.org/10.9740/mhc.2024.08.247

Mahmut MK, Fitzek J, Bittrich K et al. (2021) Can focused mindfulness training increase olfactory perception? A novel method and approach for quantifying olfactory perception. J Sens Stud 36(2):e12631

Modrego-Alarcón M, López-del-Hoyo Y, García-Campayo J et al. (2021) Efficacy of a mindfulness-based programme with and without virtual reality support to reduce stress in university students: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Res Ther 142:103866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2021.103866

Navarro-Haro MV, López-del-Hoyo Y, Campos D et al. (2017) Meditation experts try virtual reality mindfulness: a pilot study evaluation of the feasibility and acceptability of virtual reality to facilitate mindfulness practice in people attending a mindfulness conference. PLoS ONE 12(11):e0187777. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187777

Newman MARK, Gatersleben B, Wyles KJ, Ratcliffe E (2022) The use of virtual reality in environment experiences and the importance of realism. J Environ Psychol 79:101733

Paletta L, Pszeida M, Schüssler S et al. (2021) Virtual reality-based sensory triggers and gaze-based estimation for mental health care. Adv Neuroergon Cogn Eng 259:461–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-80285-1_53

Paletta L, Schüssler S, Kober SE et al. (2020) Virtual reality–based mindfulness training, sensory activation and mental assessment in dementia care: developing topics. Alzheimer’s Dement 16(S7):e047344. https://doi.org/10.1002/alz.047344

Pang Z, Tu D, Cai Y (2019) Psychometric properties of the SAS, BAI, and S-AI in Chinese university students. Front Psychol 10:93. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00093

Pedrelli P, Nyer M, Yeung A, Zulauf C, Wilens T (2015) College students: mental health problems and treatment considerations. Acad Psychiatry 39(5):503–511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-014-0205-9

Pérez-Peña M, Notermans J, Desmedt O et al. (2022) Mindfulness-based interventions and body awareness. Brain Sci 12(2):285. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12020285

Riva G (2005) Virtual reality in psychotherapy: review. Cyberpsychol Behav 8(3):220–230. 10

Rochet M, El-Hage W, Richa S et al. (2018) Depression, olfaction, and quality of life: a mutual relationship. Brain Sci 8(5):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci8050080

Sadowski I, Böke N, Mettler J et al. (2020) Naturally mindful? The role of mindfulness facets in the relationship between nature relatedness and subjective well-being. Curr Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01056-w

Sadowski I, Khoury B (2022) Nature-based mindfulness-compassion programs using virtual reality for older adults: a narrative literature review. Front Virtual Real 3:892905. https://doi.org/10.3389/frvir.2022.892905

Shek DTL (1990) Reliability and factorial structure of the Chinese version of the Beck Depression Inventory. J Clin Psychol 46(1):35–43

Simpson R, Simpson S, Ramparsad N et al. (2019) Mindfulness-based interventions for mental well-being among people with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 90(9):9. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2018-320165

Stallman HM (2010) Psychological distress in university students: a comparison with general population data. Aust Psychol 45(4):4. https://doi.org/10.1080/00050067.2010.482109

Storrie K, Ahern K, Tuckett A (2010) A systematic review: students with mental health problems—a growing problem. Int J Nurs Pract 16(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2009.01813.x

Tang YY, Hölzel BK, Posner MI (2015) The neuroscience of mindfulness meditation. Nat Rev Neurosci 16(4):213–225. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn3916

Ulrich RS, Simons RF, Losito BD et al. (1991) Stress recovery during exposure to natural and urban environments. J Environ Psychol 11(3):3. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80184-7

Wang C, Wen W, Zhang H et al. (2021) Anxiety, depression, and stress prevalence among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2021.1960849

Wang F, Jin J, Wang J et al. (2020) Association between olfactory function and inhibition of emotional competing distractors in major depressive disorder. Sci Rep 10(1):6322. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-63416-7

Wang X, Liu Q (2022) Prevalence of anxiety symptoms among Chinese university students amid the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon 8(8):e10117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10117

Williams MT, Chapman LK, Wong J, Turkheimer E (2012) The role of ethnic identity in symptoms of anxiety and depression in African Americans. Psychiatry Res 199(1):31–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2012.03.049

Wuthrich VM, Jagiello T, Azzi V (2020) Academic stress in the final years of school: a systematic literature review. Child Psychiatry, Hum Dev 51(6):986–1015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-020-00981-y

Xu Z, Gahr M, Xiang Y et al. (2022) The state of mental health care in China. Asian J Psychiatry 69:102975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102975

Ye T, He Z, Chen C (2021) Sensory processing sensitivity among Chinese college students: gender and cultural difference. Adv Soc Sci 10(10):2751–2762. https://doi.org/10.12677/ASS.2021.1010376

Yeo NL, White MP, Alcock I, Garside R, Dean SG, Smalley AJ, Gatersleben B (2020) What is the best way of delivering virtual nature for improving mood? An experimental comparison of high definition TV, 360 video, and computer generated virtual reality. J Environ Psychol 72:101500

Yildirim C, O’Grady T (2020) The efficacy of a virtual reality-based mindfulness intervention. IEEE Int Conf Artif Intell Virtual Real 2020:158–165. https://doi.org/10.1109/AIVR50618.2020.00035

Yildirim M, Globa A, Gocer O, Brambilla A (2024) Multisensory nature exposure in the workplace: exploring the restorative benefits of smell experiences. Build Environ 262:111841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2024.111841

Zhang D, Lee EKP, Mak ECW et al. (2021) Mindfulness-based interventions: an overall review. Br Med Bull 138(1):41–57. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldab005

Zhang Q, Fu Y, Lu Y et al. (2021) Impact of virtual reality-based therapies on cognition and mental health of stroke patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res 23(11):e31007. https://doi.org/10.2196/31007

Zhang S, Chen M, Yang N et al. (2023) Effectiveness of VR based mindfulness on psychological and physiological health: a systematic review. Curr Psychol 42(6):5033–5045. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01777-6

Zhao JB, Wang YL, Ma QW et al. (2019) The chemosensory pleasure scale: a new assessment for measuring hedonic smell and taste capacities. Chem Senses 44(7):457–464. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjz040

Zivin K, Eisenberg D, Gollust SE, Golberstein E (2009) Persistence of mental health problems and needs in a college student population. J Affect Disord 117(3):180–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.001

Zhang X, Zhang M, Huang Y, Koyama S (2023) A survey on sensory hypersensitivity among university students in Japan and China. Int J Affect Eng 22(1):11–16. https://doi.org/10.5057/ijae.IJAE-D-22-00004

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Prof. Laiquan Zou for generously providing the instruments and guidance on using the olfactory equipment. This work was supported by the Program for National Natural Science Foundation of China (31970982; 32171019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jingni Ma: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Haoke Li: Data Curation, Investigation, Writing—Review & editing. Chuoyan Liang: Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis. Siqi Li: Data curation, Investigation, Formal analysis. Ziliang Liu: Investigation. Chen Qu: Funding acquisition, Project administration, Supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the School of Psychology, South China Normal University (approval number: SCNU-PSY-152) on March 24, 2023. All research procedures involving human participants strictly adhered to the ethical guidelines of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments, as well as applicable national regulations for human subject research. The approved scope of this study encompassed participant recruitment, data collection methods (including physiological measurements and subjective questionnaires), and the experimental intervention protocol. Written informed consent with a Participant Information Sheet was obtained from all participants before their participation.

Informed consent