Abstract

This study aimed to investigate student- and school-level variables influencing middle school students’ social and emotional competencies and to verify the mediation effects among these variables. Data were obtained from the Seoul Education Longitudinal Study 2020, and a multilevel path analysis was conducted. The analysis revealed that at the student level, higher problematic smartphone use was associated with decreased exercise, reading, and sleep, and lower levels of social and emotional competencies. Additionally, less exercise and reading were related to lower social and emotional competencies. At the school level, a higher proportion of online classes was associated with better peer relationships and higher social and emotional competencies. In mediation analysis, exercise and reading mediated the relationship between problematic smartphone use and social and emotional competencies at the student level. At the school level, peer relationships mediated the relationship between the proportion of online classes and social and emotional competencies. Based on the results, specific strategies for enhancing middle school students’ social and emotional competencies were discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, which has affected the entire world over the past few years, has significantly altered many aspects of daily life. One of the most substantial changes experienced by students during the pandemic was their inability to attend in-person classes. The implementation of remote learning not only transformed educational methods but also impacted interactions with key figures in adolescents’ lives, such as family members, teachers, and classmates (Calandri et al., 2021). As students spent more time at home and less time interacting face-to-face with their peers, the time they spent with their families increased, whereas in-person peer interactions diminished. This isolation from the external environment adversely affected their mental health, with reports indicating an increase in depression, stress, anger, and anxiety during the pandemic (Calandri et al., 2021; Conceição et al., 2021; Deolmi & Pisani, 2020; Guessoum et al., 2020; Hammerstein et al., 2021). Additionally, the sudden shift to online learning environments led to a general decline in academic achievement (Bailey et al., 2021) and exacerbated educational disparities between high- and low-achieving students (Bailey et al., 2021). Despite the various impacts of COVID-19, much research has focused on reducing the achievement gap post-pandemic, with relatively less attention paid to the psychological support and social skill development of students (Calandri et al., 2021). Therefore, it is crucial to not only address academic deficits but also emphasize the importance of social and emotional domains that are naturally acquired during developmental processes.

Social and emotional competencies

Social and emotional competencies in adolescents refer to the ability to appropriately recognize and respond to the social and emotional aspects of oneself and others, enabling the performance of life tasks such as learning, forming relationships, solving daily problems, and adapting to complex developmental challenges (Elias et al., 1997). The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL, 2005) defines five core social and emotional competencies: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making.

Self-awareness involves understanding one’s emotions and values, appropriately assessing personal qualities, and recognizing their impact on decisions and behaviors. Self-management refers to regulating emotions, thoughts, and actions to cope with stressful events, and staying motivated. Social awareness entails empathizing with others and understanding that people may have different perspectives regardless of their similarities or differences to oneself. Relationship skills encompass effective communication, active listening, and the ability to resist negative social influences while pursuing positive relationships and managing conflicts wisely. Finally, responsible decision-making refers to making responsible and ethical decisions by critically understanding problems, considering alternative solutions, anticipating the outcomes of choices, and monitoring their consequences.

These clusters of social and emotional competencies are taught, modeled, and practiced within the school environment to help students internalize these skills and prevent maladaptive behaviors (CASEL, 2005; Zins et al., 2007). Research has shown that social and emotional competencies positively influence engagement in learning contexts (Nix et al., 2013) and academic achievement (Nix et al., 2013; Oberle et al., 2014; Rhoades et al., 2011). Additionally, these competencies are foundational for positive and prosocial behaviors, forming the basis for adolescents’ sense of belonging in school (Durlak et al., 2011). Enhancing these competencies can reduce suspensions, aggressive behaviors, substance abuse, and absenteeism while increasing school engagement and classroom participation (Gueldner et al., 2020). Furthermore, the impact of social and emotional competencies during adolescence extends into adulthood, suggesting that their stable development is a critical developmental task (Katz et al., 2011).

Given the importance of social and emotional competencies in adolescents, identifying the factors that influence their development is essential. Various individual and environmental factors are known to affect social and emotional competencies. At the individual level, family variables such as parental beliefs and interests (Li et al., 2023), and socioeconomic status (Shi et al., 2023) significantly influence these competencies. Additionally, lifestyle factors such as physical activity (Cho, 2020; Haugen et al., 2013), participation in book clubs, and adequate sleep (Hosseinzadeh Siboni et al., 2023) contribute to their improvements. At the school level, the teaching and learning environment, including active learning strategies (Wang et al., 2024), clear goals and standards (Wang et al., 2024), and social and emotional learning curricula (Shi et al., 2023) has been found to play a significant role in fostering social-emotional competencies.

Thus, social and emotional competencies are shaped not only by individual, day-to-day factors but also by broader institutional environments. Therefore, analyzing these influencing factors requires a multilevel perspective, considering both individual and school-level variables. This study adopts a comprehensive approach by examining the pathways that influence social and emotional competencies at two levels: the student and school levels. Specifically, the study focuses on variables significantly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, including the institutional remote learning environment and changes in students’ individual life circumstances. Furthermore, given that today’s younger generation today is increasingly exposed to the online environment from an early age and considers internet accessibility a fundamental necessity (Koulopoulos & Keldsen, 2016), this study investigates the role of digital-related factors in shaping social and emotional competencies. To reflect this unique digital familiarity, the analysis incorporates digital-related variables as key themes for each level: problematic smartphone use at the individual level and online classes at the school level.

The impact of problematic smartphone use on social and emotional competencies

According to incentive sensitization theory (Robinson & Berridge, 2001), addictive behaviors initially stem from positive reinforcement—such as the mood-enhancing effects of smartphone use—but gradually evolve into craving and compulsive engagement (Elhai et al., 2017; Robinson & Berridge, 1993). This process is exemplified by adolescents’ persistent checking of notifications and the pursuit of social reassurance, which is closely linked to the “fear of missing out (FoMO)” (Billieux et al., 2015; Elhai et al., 2017). Over time, this pattern of behavior can negatively impact adolescents’ social and emotional competencies.

The comprehensive model of problematic mobile phone use proposes three pathways that are closely related to social and emotional competencies (Billieux et al., 2015): the excessive reassurance pathway, the impulsive pathway, and the extraversion pathway. First, the excessive reassurance pathway describes how adolescents who frequently turn to digital platforms to cope with anxiety, stress, or the FoMO may struggle to develop adaptive strategies such as cognitive reappraisal or seeking in-person social support (Elhai et al., 2017). Constant peer comparison and the pursuit of online affirmation may further disrupt the reflective processes that are crucial for developing a stable sense of self and emotional regulation (Billieux et al., 2015; Elhai et al., 2017). Second, the impulsive pathway characterizes individuals with poor impulse control, leading to uncontrolled urges and deregulated smartphone use (Billieux et al., 2015). This lack of self-regulation may interfere with their ability to manage emotions effectively, thereby impairing social and emotional competencies. Lastly, the extraversion pathway is associated with a heightened need for stimulation and a strong sensitivity to rewards (Billieux, 2012; Billieux et al., 2015). This pathway is particularly relevant to the management and regulation of emotions and behaviors within the framework of social and emotional competencies.

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly exacerbated the excessive use of digital devices as remote interactions replaced face-to-face communication. Prolonged periods of remote learning and the absence of in-person schooling led to increased screen time across all age groups, with adolescents experiencing an average increase of 0.9 h per day (Trott et al., 2022). Studies conducted worldwide highlighted the pandemic’s impact on adolescents’ problematic smartphone use. For example, in Brazil, problematic smartphone use during the pandemic displaced other leisure activities (de Freitas et al., 2022), while in Switzerland, excessive screen media use was associated with negative mental health outcomes in adolescents (Marciano et al., 2022). Notably, in South Korea, national statistics revealed a steady rise in adolescent smartphone dependence during pandemic, with the proportion of adolescents at risk increasing from 29.3% in 2018 and 30.2% in 2019 to 35.8% in 2020, 37.0% in 2021, and 40.1% in 2022 (Ministry of Science and ICT, 2021).

The increase in problematic smartphone use among adolescents has had detrimental effects on their physical and mental health, hindering the development of social and emotional competencies. For instance, Buctot et al. (2020) demonstrated that problematic smartphone use negatively affects adolescents’ quality of life both physically and mentally, irrespective of gender. Similarly, Hartati et al. (2023) identified a negative relationship between problematic smartphone use and emotional intelligence, while Pera (2020) observed that problematic smartphone use in younger generations leads to psychological symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and difficulties with impulse control. Additionally, Al-Kandari and Al-Sejari (2021) reported a positive correlation between problematic smartphone use and social isolation across diverse age groups and genders. Collectively, the evidence highlights the negative impact of problematic smartphone use on adolescents’ social and emotional competencies. Addressing these issues is critical for fostering healthier developmental trajectories during adolescence.

The relationship between problematic smartphone use, lifestyle habits, and social and emotional competencies

Problematic smartphone use has a detrimental impact on various aspects of life, with the most pronounced effects on fundamental lifestyle habits essential for adolescent development, such as exercise, reading, and sleep. Problematic smartphone use disrupts these habits, which in turn influences social and emotional competencies. For instance, excessive smartphone use has been shown to interfere with physical activity (Haripriya et al., 2019; Lepp et al., 2013), reduce time spent on reading (Çizmeci, 2017; Gezgin et al., 2023), and decrease both the duration and quality of sleep (Gezgin, 2018; Park et al., 2022). These disruptions impair adolescents’ ability to develop and maintain essential social and emotional skills.

Previous research has shown that physical activity is positively correlated with social and emotional competencies, self-esteem, and social adaptability (Damasio, 1996; Liu et al., 2023). Exercise plays a crucial role in shaping social and emotional competencies, extending beyond mere physical improvement. Participation in physical activities fosters positive emotions and social skills in adolescents (Boone & Leadbeater, 2006). Team sports, in particular, require communication and cooperation, enhancing social and emotional competencies through interaction (Luna et al., 2021; Su et al., 2018). Similarly, multiple studies confirm that reading contributes positively to the development of social and emotional competencies (Benner et al., 2005; Yu et al., 2023). Recognizing these benefits, various reading strategies have been employed to enhance emotional and social skills (Fettig et al., 2018; Llorent et al., (2022)). Lastly, insufficient or delayed sleep reduces adolescents’ ability to interact with others and manage stress, which negatively affects their social and emotional competencies (Killgore et al., 2008). In South Korea, where academic demands often result in sleep deprivation among students (Rhie et al., 2011), the role of sleep as a critical factor in personal development warrants greater attention. Based on this discussion, this study hypothesizes that adolescents’ dependence on smartphones negatively impacts their social and emotional competencies, with lifestyle habits such as reading, exercise, and sleep acting as mediators. Specifically, the following hypotheses are proposed:

\({H}_{1.}\) Problematic smartphone use will negatively affect social and emotional competence.

\({H}_{2.}\) Lifestyle habits will positively affect social and emotional competencies.

\({H}_{3.}\) The relationship between problematic smartphone use and social and emotional competencies will be mediated by lifestyle habits.

The relationship between online learning environment in schools, peer relationships, and social and emotional competencies

At the school level, COVID-19 pandemic negatively impacted the development of students’ social and emotional competencies by closing schools and introducing the new challenges of the online learning environment. Online learning refers to educational experiences that enable synchronous or asynchronous interactions through devices with internet access (Dhawan, 2020). This modality allows students to engage with peers and instructors regardless of location (Singh & Thurman, 2019). While online learning provides flexibility for students to progress at their own pace (McDonald, 1999), it also presents challenges, including limited attention spans, reduced classroom interaction, and lack of student feedback regarding understanding instructors (Mukhtar et al., 2020).

During the pandemic, schools’ role as spaces for fostering social and emotional development through interactions with teachers and peers was significantly constrained. The shift to remote learning drastically reduced face-to-face interactions among students, leading to decreased attachment to schools and diminished in-person interactions among classmates (Ellis et al., 2020; Maiya et al., 2021). These reductions likely had varying negative effects on the development of social and emotional competencies, depending on the school context.

Peer relationships are critical for adolescents’ social and emotional development, as they help individuals acquire behaviors, skills, attitudes, and experiences that enhance their quality of life and adaptability (Rubin et al., 2008). These interactions extend beyond the influence of family, school, and neighborhood, playing a central role in shaping adolescents’ social and emotional competencies. In response, social-emotional learning theory emphasizes the importance of acquiring socially normative behaviors, rules, and positive interactions through peer engagement, which fosters attachment and bonding with the school (Zins, 2004). Thus, examining the role of peer relationships alongside the impact of online learning environments at the school level is essential.

Empirical studies demonstrate that the quality of peer relationships directly affects children’s social development (Berndt, 2002; Ee & Ong, 2014). However, the lack of face-to-face interactions during the pandemic reduced opportunities for conversations and activities with peers, negatively impacting adolescents’ social and emotional competencies (Singh et al., 2020). Even adolescents who previously displayed no social vulnerabilities experienced difficulties in social communication (Martinsone et al., 2022), indicating that COVID-19 hindered close peer interactions and likely negatively impacted social and emotional development. Based on the discussion, we hypothesized the following relationships at the school level:

\({H}_{4.}\) The proportion of online classes will negatively affect social and emotional competence.

\({H}_{5.}\) Peer relationships will positively affect social and emotional competence.

\({H}_{6.}\) The relationship between the proportions of online classes and social and emotional competencies will be mediated by peer relationships.

Methods

Data and participants

This study used data from the Seoul Education Longitudinal Study 2020 conducted by the Seoul Metropolitan Office of Education to analyze the long-term effects of educational policies and activities (Seoul Education Research & Information Institute, 2020). Although the first year of data collection was planned for 2020, that collection was postponed until 2021 due to COVID-19.

The Seoul Education Longitudinal Study employs a multistage stratified cluster sampling method to collect data from students, parents, teachers, principals, and schools in a multilevel structure. The sampling procedure consists of three key steps. First, stratified sampling divides the population into strata based on specific variables that influence academic achievement, such as district and school type, and then selects an allocated number of samples from each stratum. Second, multistage sampling is applied, where schools are selected in the first stage, followed by the selection of classes within those schools in the second stage. Third, cluster sampling is used, where all students in the selected classes are included in the study. The survey was conducted primarily online, except for the measurement of social and emotional competencies, which was administered offline. Participation in the study was voluntary, and no compensation was provided.

Among the three panels comprising elementary, middle, and high school students, this study focused on the middle school panel (7th grade, twelve to thirteen years old) to examine social and emotional competencies during periods of significant physical, emotional, and social change. This panel was selected because these students experienced a mix of remote and in-person classes during their transition to middle school, requiring them to form new peer relationships in an online environment, which likely presented greater challenges than in other grades. The data used in this study included a total of 4813 students, with 2325 male students (48.3%) and 2350 female students (48.8%); 137 students did not report their gender. The sample comprised 98 schools, with a minimum of 20 students and a maximum of 111 students surveyed per school.

Measures

Social competence

The social competence assessment used in the Seoul Education Longitudinal Study is based on the conceptual definition of the ability to form and maintain social relationships for living harmoniously with others. This assessment tool was developed by the Seoul Metropolitan Office of Education (Kim et al., 2019) and comprises three sub-competencies: relationships, cooperation, and conflict resolution. Relationship competence includes diversity, communication, and interpersonal skills; cooperation competence includes consideration and collaboration skills; and conflict resolution competence includes avoidance, relationship focus, goal pursuit, and co-operative resolution. The social competence assessment consists of 50 self-report items in which the respondents evaluate how they would act in various scenarios. Examples of the items include: ‘When my friend speaks, I express my thoughts or feelings through facial expressions, eye contact, and nodding’, and ‘When a group member faces difficulties, I first ask if they need help’. Among the scales, nine conflict resolution items were reverse-coded to ensure consistent interpretation, which higher values reflecting more ideal conflict resolution strategies. In this study, the Cronbach’s α of the subfactor was 0.903 for relationship competence, 0.929 for cooperation competence, and 0.739 for conflict resolution competence.

Emotional competence

The emotional competence assessment used in the Seoul Education Longitudinal Study is based on the definition of the ability to recognize and positively manage one’s own and others’ emotions in the context of achieving goals and interacting with others in school, as outlined in previous studies (Mayer & Salovey, 1997; Mayer et al., 2004; Salovey & Mayer, 1990). The Seoul Metropolitan Office of Education developed and validated this assessment tool. It comprises four sub-competencies: emotional regulation, emotional management, emotional awareness, and emotional expression. Emotional regulation competence encompasses the self-regulation of emotions (self and others) and resilience (optimism and vitality). Emotional management competence includes emotional control and management of emotional resources. Emotional awareness competence includes emotional recognition and cognitive and emotional empathy. Emotional expression competence is a single form of competence. The assessment uses scenarios depicting everyday emotional situations in the school context to provide a vivid emotional setting for self-reported responses. The items were developed considering the stages of emotional development specific to each school level, as presented in CASEL’s (2005) Illinois Social and Emotional Learning Standards study to enhance the realism of emotional responses. Emotional competence was assessed using 47 items. Examples of the items include: ‘I can appropriately express my emotions without hurting my friend’s feelings’, and ‘When a friend is sad, I feel empathy and want to comfort them’. In this study, the Cronbach’s α of the subfactor was 0.901 for emotional regulation competence, 0.861 for emotional management competence, 0.906 for emotional awareness competence, and 0.808 for emotional expression competence.

Problematic smartphone use

Problematic smartphone use was measured using five items: ‘I often get nagged by my parents about my smartphone use’, ‘I feel anxious when I go out without my smartphone’, ‘I place my smartphone within easy reach or hold it while sleeping’, ‘I check my smartphone as soon as I wake up’, and ‘I feel bad when I can’t connect to the Internet’. Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating greater problematic use of smartphones. In this study, the reliability of the items, measured by Cronbach’s α, was 0.752.

Hours of exercise, reading volume, sleep duration

Exercise hours were measured as the average weekly hours of exercise, excluding physical education classes. Reading volume was assessed using the average number of books read per month, excluding textbooks and workbooks. The sleep duration was self-reported as the average number of hours of sleep per night. Sleep duration was measured on a scale where less than 5 h was scored as 1, 5–6 h as 2, 6–7 h as 3, 7–8 h as 4, 8–9 h as 5, 9–10 h as 6, 10–11 h as 7, 11–12 h as 8, and >12 h as 9. In this study, the average number of hours of exercise for the participants was 2.61 h per week, and the average reading volume was 3.4 books per month. The average sleep duration score was 3.75, indicating an average sleep duration of 7–8 h per night.

Proportion of online classes

The proportion of online classes was calculated using responses to a school-level questionnaire regarding the number of days of online and in-person classes. The proportion of online classes was derived by dividing the number of online class days by the total number of school days (the sum of online and in-person class days). When the survey was conducted in 2021, South Korea had implemented a hybrid model for in-person and online classes. The number of in-person class days was adjusted based on class size, regional conditions, and COVID-19 infection rates.

Peer relationships

Peer relationships were measured using three items: ‘I have friends I can trust and talk to’, ‘I prefer to spend time with classmates or peers rather than being alone’, and ‘I make an effort to reconcile after a fight with friends’. Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree), with higher scores indicating better peer relationships. In this study, the reliability of the items, as measured by Cronbach’s α, was 0.785.

Control variables

First, the socio-demographic variables were controlled for in the analysis. In this study, gender (0 = male, 1 = female), coeducational status (0 = school with all gender, 1 = single-gender school), parental educational level (0 = below elementary school to 7 = doctoral degree), and household income were included as control variables. These variables were selected based on prior research indicating that boys (Chen et al., 2015; Oberle et al., 2014; Shi et al., 2023), lower-income households (Lee et al., 2024; Shi et al., 2023), and lower parental education levels (Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2024) are associated with lower levels of social and emotional competence.

Second, variables that might influence patterns of digital device use were also included as control variables. At the school level, the average of students’ individual problematic smartphone use and their online chat usage (1 = never use, 2 = once or twice a month, 3 = three or four times a month, 4 = two to four times a week, 5 = almost everyday) were included as school-level control variables. Additionally, the school-level average of students’ responses regarding the most frequently used class format during COVID-19 (0 = others, 1 = real-time, interactive classes with co-operative work or peer debates) was controlled to account for the potential effects of online class formats and peer relationship experiences, which are key pathways investigated in this study.

Analysis

As the data used in this study have a multilevel structure in which students are nested in schools, a multilevel path analysis was used to analyze the data. The model’s goodness of fit was checked at the student and school levels using the method proposed by Ryu and West (2009), who suggested checking fit at the within-group and between-group levels using the following four steps: In the first step, a saturated model is set for the between-level model, and a baseline model is analyzed for the within-level model. A saturated model assumes that all the variables are correlated, whereas a baseline model assumes that all the variables are unrelated. In the second step, the saturation model is analyzed for the between-level model, and the theoretical model (research model) is analyzed for the within-level model. The values (\({\chi }^{2}\), degrees of freedom) derived from these two processes are used to calculate the goodness of fit at the within-group level. The third step is to analyze the saturation model at the within level and the underlying model at the between level. The fourth step analyzes the saturated model at the within-level and the theoretical model at the between-level and calculates the between-level fit using the same values from the two processes as the within-level fit. We calculated the CFI, TLI, and RMSEA values at the student and school levels using these methods. The SRMR did not need to be calculated separately because the Mplus program used in the analysis provided values separately by default.

In addition, when validating the multilevel structural equation model in Mplus, the parameters are estimated by default through the Maximum Likelihood estimation with robustness (MLR) method, but the method proposed by Ryu and West (2009) is based on the Maximum Likelihood estimation (ML) method; therefore, the MLR method was used to estimate the parameters of the overall research model, but the ML method was used to calculate the goodness of fit. Missing values were handled using the Full Information Maximum Likelihood method, which has been shown to perform well, even in multilevel structures (Larsen, 2011).

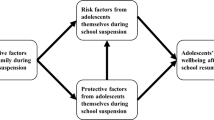

Mediation effects were tested using Monte Carlo (MC) 95% confidence intervals. The MC method assumes that the indirect effect coefficient is a joint normal distribution with a mean and covariance matrix (Preacher & Selig, 2012) and generates a distribution for the indirect effect coefficient (ab) by generating the coefficients (a, b) from the joint normal distribution several times and multiplying them. Bootstrapping is commonly used to test for mediation in structural equation models; however, there are limitations to using bootstrapping in multilevel models (Goldstein, 2011). For example, if the required number of samples from the lower level are repeatedly drawn, and the higher level of the sample is categorized, the number of higher-level groups and the number of individuals included in each group may be different from the original sample. Conversely, if repeated sampling is performed at a higher level, the number of higher-level groups may vary depending on the sampling, such that certain groups cannot be selected. Therefore, this study used the MC method, which does not have the problem of a fluctuating number of individuals at a lower or higher level in the multilevel model. Descriptive statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 25.0, R studio for data preprocessing, and Mplus 8.3 for multilevel path analysis. The final model used in this study is shown in Fig. 1. The measurement variables are represented by rectangles, the latent variables by circles, and errors and covariances are omitted.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

The results of the descriptive statistical analysis of the main variables are presented in Tables 1 and 2. At the student level, social competence and emotional competence were highly positively correlated and negatively associated with problematic smartphone use. Problematic smartphone use was also negatively correlated with hours of exercise, reading volume, and sleep. In contrast, the lifestyle variables—exercise, reading, and sleep—were positively correlated with one another. At the school level, the proportion of online classes and the school-average peer relationships were positively correlated. Most of the variables had a skewness below 2 and a kurtosis below 7, indicating the normality of the data (Curran et al., 1996). Although the kurtosis of the log-transformed household income variable slightly exceeded the cutoff, it remained within an acceptable range.

Since social competence, emotional competence, and problematic smartphone use (a school-level control variable) were analyzed at both the student and school levels, the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were calculated for these variables. The ICC for social competence was 0.017, and for emotional competence, it was 0.021, indicating that school-level variance accounted for 1.7% and 2.1% of the total variance for each competence, respectively. The ICC for problematic smartphone use was 0.014, suggesting the minimal variance at the school level.

Although the ICC values were relatively low, it is important to account for the multilevel structure of the data. Previous research has shown that Type I error rates increase with larger sample sizes in multilevel datasets, irrespective of the ICC magnitudes (Barcikowski, 1981; Hox, 1998). Consequently, this study employed a model that accounts for the hierarchical nature of the data to ensure statistical accuracy and robustness.

Multilevel path analysis

The goodness of fit of the model was calculated at each level, following Ryu and West (2009). All fit indices met the criteria of Browne and Cudeck (1992) and Hu and Bentler (1999) except for TLI, which was slightly lower at student-level (Table 3).

The coefficients for each path are presented in Table 4. At the student level, problematic smartphone use demonstrated significant negative relationships with exercise, reading, and sleep. As problematic smartphone use increased, time spent on exercise, reading volume, and sleep duration decreased. Additionally, exercise and reading were positively associated with both social competence and emotional competence, while sleep showed no significant relationship with either competence. Problematic smartphone use, however, was significantly and negatively associated with both social competence and emotional competence.

At the school level, the proportion of online classes during the COVID-19 pandemic was significantly and positively associated with peer relationships. This result suggests that students in schools with a higher percentage of online classes during the pandemic, on average, reported better peer relationships. Peer relationships, in turn, were positively associated with both social competence and emotional competence. However, the proportion of online classes did not show a significant direct relationship with social or emotional competence at the school level.

Finally, the mediation effects at the student and school levels were tested using MC confidence intervals and are presented in Table 5 and Fig. 2. At the student level, exercise and reading were found to mediate the relationship between problematic smartphone use and social and emotional competence; however, there was no mediating effect on sleep duration. In other words, the higher the problematic smartphone use, the lower the exercise and reading, and the more negative the effect on social and emotional competence. At the school level, peer relationships mediated the relationship between the proportion of online classes and social and emotional competence. This means that schools with a higher proportion of online classes had better peer relationships on average and that good peer relationships had a positive effect on social and emotional competence.

Discussion

This study employed multilevel path analysis to investigate whether lifestyle mediates the relationship between problematic smartphone use and social and emotional competence at the student level and whether peer relationships mediate the relationship between online classes and social and emotional competence at the school level. The findings of the analysis are summarized as follows.

First, at the student level, problematic smartphone use was negatively associated with social and emotional competence, supporting \({H}_{1}\). This finding aligns with previous research demonstrating the detrimental effects of problematic smartphone use on social and emotional competencies (Morales Rodríguez et al., 2020). Excessive smartphone use has been shown to impair self-regulation (Akulwar-Tajane et al., 2020; Pera, 2020), a core aspect of self-management within social and emotional competence, which involves regulating emotions and behaviors in stressful situations (CASEL, 2005). Additionally, problematic smartphone use is associated with reduced intrapersonal management and awareness (Nidhi et al., 2024), which negatively affects relationship skills, a key component of social competence.

Importantly, the negative relationship between problematic smartphone use and social and emotional competencies remained significant even after controlling for the effects of gender and family environment variables (e.g., parental education level and household income), which are known to influence the development of social and emotional skills (Lee et al., 2024; Rimm-Kaufman et al., 2024; Shi et al., 2023). This suggests that problematic smartphone use diminishes adolescents’ opportunities to develop social and emotional competencies and maintain a healthy mental state, ultimately hindering their psychological and social maturity.

Among lifestyle habits, exercise and reading volume were positively associated with both social and emotional competencies, supporting \({H}_{2}\). These findings are consistent with prior research. Physical activity has been shown to reduce negative emotions and enhance positive ones (Cooney et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2015), facilitating improvements in social and emotional competencies. Similarly, reading has been associated with benefits such as improved self-esteem (Kang, 2017) and heightened social-cognitive competence in adolescence (Lenhart et al., 2022). These studies align with the observed positive effects of exercise and reading on adolescents’ social and emotional competence in this study.

Contrary to expectations, sleep duration did not significantly affect social or emotional competence. This may be attributed to the relative importance of sleep quality over the absolute amount of sleep. For instance, previous research has demonstrated that sleep quality mediates the relationship between smartphone overdependence and depressive symptoms (Hong et al., 2020). Consequently, future studies should include instruments measuring sleep quality, such as the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (Buysse et al., 1989), to determine whether it is associated with social and emotional competence alongside sleep duration.

Second, the mediating effect of problematic smartphone use on social and emotional competencies through exercise duration and reading volume was significant, partially supporting \({H}_{3}\). The negative relationships between problematic smartphone use on exercise and reading are found to be significant, aligning with findings from previous studies (Buke et al., 2021; Bukhori et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2015). These results are consistent with prior research suggesting that when students are distracted by a powerful, disruptive device—such as a smartphone—they tend to experience boredom with activities requiring physical or mental effort, favoring more sedentary environments instead (Gezgin et al., 2023; Lepp et al., 2013; Sağır & Eraslan, 2019).

The results of the mediation analysis offer a plausible explanation of the pathway between problematic smartphone use and social and emotional competencies. Specifically, the mediation pathway indicates that adolescents with higher levels of problematic smartphone use spend less time and effort engaging in activities that stimulate their brain and body, ultimately resulting in lower social and emotional competencies. However, viewed conversely, this finding highlights the potential of healthy habits such as exercise and reading to buffer the harmful effects of problematic smartphone use on social and emotional competencies. As widely recognized, exercise and reading are effective strategies for improving mental health issues such as anxiety and depression, as well as enhancing social and emotional well-being (Billington et al., 2010; Stathopoulou et al., 2006). Therefore, it is critical to explore strategies that help students mitigate the distractions caused by smartphones and develop interest in physical activities and reading as part of efforts to foster social and emotional maturity. School education policies and parental guidance can play a pivotal role in encouraging these healthy habits.

Another notable finding at the individual level is that the direct effect of problematic smartphone use on social and emotional competencies remained significant, even after accounting for the mediation effect of lifestyle habits. This suggests the existence of a lifestyle-independent pathway through which problematic smartphone use impacts social and emotional competencies. Previous research points to the possibility of psychological mechanisms, such as increased depression or reduced self-esteem, mediating the relationship between problematic smartphone use and social and emotional competencies. Future studies should explore these alternative pathways by including mediators beyond lifestyle factors to determine whether other mechanisms may explain this relationship.

Third, at the school level, the proportion of online classes did not have a direct effect on social and emotional competencies, which did not support \({H}_{4}\). However, peer relationships had a significant positive effect on social and emotional competence, supporting \({H}_{5}\). The nonsignificant relationship between online classes and social and emotional competencies suggests that online classes do not directly influence these competencies after accounting for the mediating effect of peer relationships. Together, the results of the mediation analysis indicate that online learning impacts social and emotional competence indirectly through its influence on peer relationships.

The significant effect of peer relationships on social and emotional competencies aligns with the importance of peer relationships as emphasized by social-emotional learning theory (Zins, 2004) and empirical studies (Berndt, 2002; Ee & Ong, 2014). Previous research has highlighted the value of interventions that help students build positive peer relationships as an effective strategy to enhance relationship skills, a core component of social and emotional competencies (Ng & Bull, 2018). The findings of this study reaffirm the critical role of fostering amicable peer relationships in supporting students’ social and emotional development.

Furthermore, the results showed that schools with a higher proportion of online classes during the COVID-19 pandemic had students with better overall peer relationships, and these relationships positively affected social and emotional competencies, demonstrating full mediation. This finding contrasts with previous research and H6, which hypothesized that online learning during the pandemic would negatively impact peer relationships by reducing opportunities for peer-to-peer interactions (Martinsone et al., 2022; Rosanbalm, 2021; Singh et al., 2020). Notably, the positive association between online classes and peer relationships remained significant even after controlling for school characteristics (e.g., coeducational status), students’ digital device use (e.g., problematic smartphone use and online chat usage at the school level), and the delivery format of online classes (e.g., real-time classes with peer communication).

There are two possible explanations for these unexpected results. First, some studies have identified similar findings, suggesting that online classes may foster certain aspects of peer relationships. For instance, Baek and Rha (2023) found that subfactors of classroom community—such as caring, trust, and reliance—were higher in online classes compared to offline classes. This may be because students initially formed peer relationships online during the pandemic, making offline interactions feel less familiar or more awkward. Similarly, students in this study may have established their first peer connections through online classes when they began middle school. At the time of the survey (October 2021), schools were still alternating between online and offline classes, and the full resumption of in-person learning in the greater Seoul area only began in late November 2021 (Chung, 2021, November 19). Consequently, students who continued with partial online learning may have felt more comfortable with the online interactions they were accustomed to.

Additionally, Branquinho et al. (2020) highlighted the positive aspects of online social life, such as strengthening friendships by enabling a broader selection of friends. This finding further underscores the potential for digital platforms to facilitate unique opportunities for peer interaction, even during periods with limited in-person contact. Furthermore, as digital natives, students may have a preference for online communication, aligning with previous research highlighting the comfort that younger generations feel in digital environments (Baek & Rha, 2023; Poláková & Klímová, 2019).

Given these characteristics of digital-native students, it is crucial for schools to focus on developing social and emotional competencies tailored to online interactions. More attention should be given to fostering social-emotional e-competencies—skills necessary for successful virtual communication and interaction (Cebollero-Salinas et al., 2022). These competencies are not only vital for maintaining prosocial peer relationships but are also linked to essential digital skills such as digital literacy (Katzman & Stanton, 2020). Further exploration of this area is needed to prepare students for the evolving demands of contemporary society.

Another possible explanation for the positive relationship between online classes and peer relationships lies in the reduced exposure to negative social interactions in an online learning environment. Online classes may limit opportunities for face-to-face conflicts, which are more common in offline settings. For example, Vania et al. (2022) found that while companionship and closeness were lower in online classes compared to offline environments, peer conflicts were also significantly reduced. Similarly, Sharma et al. (2021) reported online that the transition to online learning during the pandemic helped reduce school-related bullying, which improved adolescents’ life satisfaction.

Supporting these findings, data from South Korea’s Ministry of Education revealed a decline in bullying victimization rates during the pandemic. The rate dropped from 1.6% in 2019 to 0.9% in 2020 (when full virtual learning was implemented) and 1.1% in 2021 (when hybrid learning was adopted). However, it increased again to 1.7% in 2022 and 1.9% in 2023 during the post-pandemic period (Ministry of Education, 2023). This suggests that the online learning environment, by minimizing harmful interactions, may have allowed students to perceive peer relationships more positively.

In summary, while online learning poses challenges to peer interaction, it also offers opportunities to reduce conflicts and promote positive peer dynamics in some contexts. Future research should further investigate the unique characteristics of online peer interactions and develop educational strategies to enhance social and emotional competencies in virtual environments.

Limitations and future research suggestions

The limitations of this study are as follows. First, this study utilized cross-sectional data and was unable to test the long-term effects of problematic smartphone use and the proportion of online classes on social and emotional competence. As social and emotional competencies develop over a long period, checking the mediating effect between variables at the same point in time is not sufficient to identify the exact relationship. In addition, this study only analyzed data from 2021; therefore, it is not possible to verify whether the current results are comparable to the pre-COVID-19 situation when in-person classes were the norm. A comparative analysis of pre-COVID-19 and post-2023 data would provide a clearer picture of the impact of changes in learning and personal habits due to COVID-19 on adolescents’ social and emotional competence development.

Second, this study was conducted during the first grade of middle school, which is assumed to be more interactive and a time when students are more sensitive to the environment. However, to systematically train social and emotional competence, it is necessary to examine the influence of peer relationships and lifestyle in the early stages of social and emotional competence formation. Therefore, it would be helpful to develop age-appropriate social and emotional competence programs if future studies are conducted in elementary school or earlier to determine if the same results are found as in this study.

Finally, this study examined whether sleep duration mediates the relationship between smartphone dependence and social and emotional competence within the context of lifestyle habits. This focus on sleep duration was due to the limitations of the available data, as no specific measure of sleep quality was included. However, research by Philbrook et al. (2017) indicates that sleep quality and sleep duration have distinct effects on social and emotional competence. Therefore, future studies should incorporate a broader range of sleep-related variables, including sleep quality, to provide a more comprehensive understanding of their impact on social and emotional competence.

Data availability

The data used in this study can be downloaded from the Seoul Education Research and Information Institute website (https://www.serii.re.kr/) after completing the required form.

References

Akulwar-Tajane I, Parmar KK, Naik PH, Shah AV (2020) Rethinking screen time during COVID-19: impact on psychological well-being in physiotherapy students. Int J Clin Exp Med Res 4(4):201–216

Al-Kandari YY, Al-Sejari MM (2021) Social isolation, social support and their relationship with smartphone addiction. Inf Commun Soc 24(13):1925–1943

Baek J-Y, Rha K-H (2023) Comparing Korean college students perceptions toward online and offline classes. Int J Contents 19(2):91–99

Bailey DH, Duncan GJ, Murnane RJ, Au Yeung N (2021) Achievement gaps in the wake of COVID-19. Educ Res 50(5):266–275

Barcikowski RS (1981) Statistical power with group mean as the unit of analysis. J Educ Stat 6(3):267–285

Benner GJ, Beaudoin K, Kinder D, Mooney P (2005) The relationship between the beginning reading skills and social adjustment of a general sample of elementary aged children. Educ Treat Child 28(3):250–264

Berndt TJ (2002) Friendship quality and social development. Curr Direct Psychol Sci 11(1):7–10

Billieux J (2012) Problematic use of the mobile phone: a literature review and a pathways model. Curr Psychiatry Rev 8(4):299–307

Billieux J, Maurage P, Lopez-Fernandez O, Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD (2015) Can disordered mobile phone use be considered a behavioral addiction? An update on current evidence and a comprehensive model for future research. Curr Addict Rep. 2(2):156–162

Billington J, Dowrick C, Hamer A, Robinson J, Williams C (2010) An investigation into the therapeutic benefits of reading in relation to depression and well-being. The Reader Organization, Liverpool Health Inequalities Research Centre, Liverpool

Boone EM, Leadbeater BJ (2006) Game on: Diminishing risks for depressive symptoms in early adolescence through positive involvement in team sports. J Res Adolesc 16(1):79–90

Branquinho C, Kelly C, Arevalo LC, Santos A, Gaspar de Matos M (2020) “Hey, we also have something to say”: a qualitative study of Portuguese adolescents’ and young people’s experiences under COVID‐19. J Community Psychol 48(8):2740–2752

Browne MW, Cudeck R (1992) Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol Methods Res 21(2):230–258

Buctot DB, Kim N, Kim JJ (2020) Factors associated with smartphone addiction prevalence and its predictive capacity for health-related quality of life among Filipino adolescents. Child Youth Serv Rev 110:104758

Buke M, Egesoy H, Unver F (2021) The effect of smartphone addiction on physical activity level in sports science undergraduates. J Bodyw Mov Ther 28:530–534

Bukhori B, Said H, Wijaya T, Nor FM (2019) The effect of smartphone addiction, achievement motivation, and textbook reading intensity on students’ academic achievement. Int J Interact Mob Technol 13. https://doi.org/10.3991/ijim.v13i09.9566

Buysse DJ, Reynolds III CF, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ (1989) The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res 28(2):193–213

Calandri E, Graziano F, Begotti T, Cattelino E, Gattino S, Rollero C, Fedi A (2021) Adjustment to COVID-19 lockdown among Italian University students: the role of concerns, change in peer and family relationships and in learning skills, emotional, and academic self-efficacy on depressive symptoms. Front Psychol 12:643088

CASEL (2005) Illinois social and emotional learning standards. Safe and Sound: An Educational Leader’s Guide to Evidence-Based Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) Programs

Cebollero-Salinas A, Cano-Escoriaza J, Orejudo S (2022) Social networks, emotions, and education: design and validation of e-COM, a scale of socio-emotional interaction competencies among adolescents. Sustainability 14(5):2566

Chen C-Y, Squires J, Heo KH, Bian X, Chen C-I, Filgueiras A, Xie H, Murphy K, Dolata J, Landeira-Fernandez J (2015) Cross cultural gender differences in social-emotional competence of young children: comparisons with Brazil, China, South Korea, and the United States. Ment Health Fam Med 11(2):59–68

Cho O (2020) Impact of physical education on changes in students’ emotional competence: a Meta-analysis. Int J Sports Med 41(14):985–993

Chung E (2021, November 19). CSAT is over, and in-person classes will resume. Korea JoongAng Daily

Çizmeci E (2017) No time for reading, addicted to scrolling: the relationship between smartphone addiction and reading attitudes of Turkish youth. Intermedia Int E-J 4(7):290–302

Conceição V, Rothes I, Gusmão R (2021) The association between changes in the University educational setting and peer relationships: effects in students’ depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry 12:783776

Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA, Lawlor DA, Rimer J, Waugh FR, McMurdo M, Mead GE (2013) Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013:CD004366(9). 10.1002/14651858.CD004366.pub6. Pubmed:24026850

Curran PJ, West SG, Finch JF (1996) The robustness of test statistics to nonnormality and specification error in confirmatory factor analysis. Psychol Methods 1:16–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.16

Damasio AR (1996) The somatic marker hypothesis and the possible functions of the prefrontal cortex. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci 351(1346):1413–1420

de Freitas BHBM, Gaíva MAM, Diogo PMJ, Bortolini J (2022) Relationship between lifestyle and self-reported smartphone addiction in adolescents in the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-methods study. J Pediatr Nurs 65:82–90

Deolmi M, Pisani F (2020) Psychological and psychiatric impact of COVID-19 pandemic among children and adolescents. Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis 91:e2020149

Dhawan S (2020) Online learning: a panacea in the time of COVID-19 crisis. J Educ Technol Syst 49(1):5–22

Durlak JA, Weissberg RP, Dymnicki AB, Taylor RD, Schellinger KB (2011) The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: a meta‐analysis of school‐based universal interventions. Child Dev 82(1):405–432

Ee J, Ong CW (2014) Which social emotional competencies are enhanced at a social emotional learning camp? J Adventure Educ Outdoor Learn 14(1):24–41

Elhai JD, Dvorak RD, Levine JC, Hall BJ (2017) Problematic smartphone use: A conceptual overview and systematic review of relations with anxiety and depression psychopathology. J Affect Disord 207:251–259

Elias M, Zins JE, Weissberg RP (1997) Promoting social and emotional learning: guidelines for educators. Ascd

Ellis WE, Dumas TM, Forbes LM (2020) Physically isolated but socially connected: psychological adjustment and stress among adolescents during the initial COVID-19 crisis. Can J Behav Sci/Rev Canadienne des Sci du Comport 52(3):177

Fettig A, Cook AL, Morizio L, Gould K, Brodsky L (2018) Using dialogic reading strategies to promote social-emotional skills for young students: An exploratory case study in an after-school program. J Early Child Res 16(4):436–448

Gezgin DM (2018) Understanding patterns for smartphone addiction: Age, sleep duration, social network use and fear of missing out. Kıbrıslı Eğitim Bilimleri Derg 13(2):166–177

Gezgin DM, Gurbuz F, Barburoglu Y (2023) Undistracted reading, not more or less: The relationship between high school students’ risk of smartphone addiction and their reading habits. Technol Knowl Learn 28(3):1095–1111

Goldstein H (2011) Bootstrapping in multilevel models. In: Hox JJ, Roberts JK (eds.). Handbook of advanced multilevel analysis. Routledge, pp 163–171

Gueldner BA, Feuerborn LL, Merrell KW (2020) Social and emotional learning in the classroom: promoting mental health and academic success. Guilford Publications

Guessoum SB, Lachal J, Radjack R, Carretier E, Minassian S, Benoit L, Moro MR (2020) Adolescent psychiatric disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. Psychiatry Res 291:113264

Hammerstein S, König C, Dreisörner T, Frey A (2021) Effects of COVID-19-related school closures on student achievement-a systematic review. Front Psychol 12:746289

Haripriya S, Samuel SE, Megha M (2019) Correlation between smartphone addiction, sleep quality and physical activity among young adults. J Clin Diagn Res 13(10):5–9

Hartati S, Rachmawaty M, Rachmat IF, Maryani I (2023) The effect of smartphone addiction in early childhood towards emotional development: a correlational study. Asia-Pacific J Res Early Childhood Edun 17(1):49–66

Haugen T, Säfvenbom R, Ommundsen Y (2013) Sport participation and loneliness in adolescents: The mediating role of perceived social competence. Curr Psychol 32:203–216

Hong W, Liu R-D, Ding Y, Sheng X, Zhen R (2020) Mobile phone addiction and cognitive failures in daily life: The mediating roles of sleep duration and quality and the moderating role of trait self-regulation. Addict Behav 107:106383

Hosseinzadeh Siboni F, Emami Sigaroudi A, Pouralizadeh M, Maroufizadeh S (2023) Social competence and its related factors in high school students: a cross-sectional study. J Holist Nurs Midwifery 33(2):140–149

Hox J (1998) Multilevel modeling: when and why. In: Classification, data analysis, and data highways. Springer Verlag, New York, pp 147–154

Hu LT, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling Multidiscip J 6(1):1–55

Kang GE (2017) Bibliotherapy to improve self-esteem of minority children from multicultural families in Korea. Research Gate. pp 1–8

Katz SJ, Conway CC, Hammen CL, Brennan PA, Najman JM (2011) Childhood social withdrawal, interpersonal impairment, and young adult depression: a mediational model. J Abnorm Child Psychol 39:1227–1238

Katzman NF, Stanton MP (2020) The integration of social emotional learning and cultural education into online distance learning curricula: Now imperative during the COVID-19 pandemic. Creat Educ 11(9):1561–1571

Killgore WD, Kahn-Greene ET, Lipizzi EL, Newman RA, Kamimori GH, Balkin TJ (2008) Sleep deprivation reduces perceived emotional intelligence and constructive thinking skills. Sleep Med 9(5):517–526

Kim K, Kim W, Choi I, Kim M, Kim K, Park J, Son M, Do S, Kim S (2019) A basic study for the development of the Seoul student competency test. Korea Institute for Curriculum and Evaluation. CRE 2019-1

Kim S-E, Kim J-W, Jee Y-S (2015) Relationship between smartphone addiction and physical activity in Chinese international students in Korea. J Behav Addict 4(3):200–205. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.4.2015.028. Pubmed:26551911

Koulopoulos T, Keldsen D (2016) Gen Z effect: The six forces shaping the future of business. Routledge

Larsen R (2011) Missing data imputation versus full information maximum likelihood with second-level dependencies. Struct Equ Modeling Multidiscip J 18(4):649–662

Lee J, Shapiro VB, Robitaille JL, LeBuffe P (2024) Gender, racial-ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in the development of social-emotional competence among elementary school students. J Sch Psychol 104:101311

Lenhart J, Dangel J, Richter T (2022) The relationship between lifetime book reading and empathy in adolescents: Examining transportability as a moderator. Psychol Aesthet Creat Arts 16(4):679

Lepp A, Barkley JE, Sanders GJ, Rebold M, Gates P (2013) The relationship between cell phone use, physical and sedentary activity, and cardiorespiratory fitness in a sample of US college students. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 10:1–9

Li S, Tang Y, Zheng Y (2023) How the home learning environment contributes to children’s social–emotional competence: A moderated mediation model. Front Psychol 14:1065978

Liu M, Wu L, Ming Q (2015) How does physical activity intervention improve self-esteem and self-concept in children and adolescents? Evidence from a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 10(8):e0134804

Liu Y, Feng Q, Tong Y, Guo K (2023) Effect of physical exercise on social adaptability of college students: chain intermediary effect of social-emotional competency and self-esteem. Front Psychol 14:1120925

Llorent VJ, González-Gómez AL, Farrington DP, Zych I (2022) Improving literacy competence and social and emotional competencies in primary education through cooperative project-based learning. Psicothema 34(1):102–109

Luna P, Cejudo J, Piqueras JA, Rodrigo-Ruiz D, Bajo M, Pérez-González J-C (2021) Impact of the moon physical education program on the socio-emotional competencies of preadolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(15):7896

Maiya S, Dotterer AM, Whiteman SD (2021) Longitudinal changes in adolescents’ school bonding during the COVID‐19 pandemic: individual, parenting, and family correlates. J Res Adolesc 31(3):808–819

Marciano L, Viswanath K, Morese R, Camerini A-L (2022) Screen time and adolescents’ mental health before and after the COVID-19 lockdown in Switzerland: a natural experiment. Front Psychiatry 13:981881

Martinsone B, Stokenberga I, Damberga I, Supe I, Simões C, Lebre P, Canha L, Santos M, Santos AC, Fonseca AM (2022) Adolescent social emotional skills, resilience and behavioral problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal study in three European countries. Front Psychiatry 13:942692

Mayer JD, Salovey P (1997) Emotional development and emotional intelligence. Basics Books, Nova Iorque

Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR (2004) TARGET ARTICLES: Emotional intelligence: theory, findings, and implications. Psychol Inq 15(3):197–215. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1503_02

McDonald DS (1999) Improved training methods through the use of multimedia technology. J Comput Inf Syst 40(2):14–22

Ministry of Education (2023) Announcement of the results of the first school violence survey in 2023. Press Release 14 Dec 2023

Ministry of Science and ICT (2021) Survey on smartphone overdependence. NIA VIII-RSE-C-21048

Morales Rodríguez FM, Lozano JMG, Linares Mingorance P, Pérez-Mármol JM (2020) Influence of smartphone use on emotional, cognitive and educational dimensions in university students. Sustainability 12(16):6646

Mukhtar K, Javed K, Arooj M, Sethi A (2020) Advantages, Limitations and Recommendations for online learning during COVID-19 pandemic era. Pak J Med Sci 36(COVID19-S4):S27

Ng SC, Bull R (2018) Facilitating social emotional learning in kindergarten classrooms: Situational factors and teachers’ strategies. Int J Early Child 50(3):335–352

Nidhi PS, Hegde B, Davis A Nidhi PS, Hegde B, Davis A (2024) The relationship between emotional intelligence, smartphone addiction, and fear of missing out among students. Inspa J Appl School Psychol 5((Special Issue):108–113

Nix RL, Bierman KL, Domitrovich CE, Gill S (2013) Promoting children’s social-emotional skills in preschool can enhance academic and behavioral functioning in kindergarten: findings from Head Start REDI. Early Educ Dev 24(7):1000–1019

Oberle E, Schonert-Reichl KA, Hertzman C, Zumbo BD (2014) Social–emotional competencies make the grade: Predicting academic success in early adolescence. J Appl Dev Psychol 35(3):138–147

Park M, Jeong SH, Huh K, Park YS, Park E-C, Jang S-Y (2022) Association between smartphone addiction risk, sleep quality, and sleep duration among Korean school-age children: a population-based panel study. Sleep Biol Rhythms 20(3):371–380

Pera A (2020) The psychology of addictive smartphone behavior in young adults: problematic use, social anxiety, and depressive stress. Front Psychiatry 11:573473

Philbrook LE, Hinnant JB, Elmore-Staton L, Buckhalt JA, El-Sheikh M (2017) Sleep and cognitive functioning in childhood: ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and sex as moderators. Dev Psychol 53(7):1276

Poláková P, Klímová B (2019) Mobile technology and Generation Z in the English language classroom—a preliminary study. Educ Sci 9(3):203

Preacher KJ, Selig JP (2012) Advantages of Monte Carlo confidence intervals for indirect effects. Commun Methods Meas 6(2):77–98

Rhie S, Lee S, Chae KY (2011) Sleep patterns and school performance of Korean adolescents assessed using a Korean version of the pediatric daytime sleepiness scale. Korean J Pediat 54(1):29

Rhoades BL, Warren HK, Domitrovich CE, Greenberg MT (2011) Examining the link between preschool social–emotional competence and first grade academic achievement: The role of attention skills. Early Child Res Q 26(2):182–191

Rimm-Kaufman SE, Soland J, Kuhfeld M (2024) Social and emotional competency development from fourth to 12th grade: relations to parental education and gender. Am Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001357

Robinson TE, Berridge KC (1993) The neural basis of drug craving: an incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Res Rev 18(3):247–291

Robinson TE, Berridge KC (2001) Incentive‐sensitization and addiction. Addiction 96(1):103–114

Rosanbalm K (2021) Social and emotional learning during COVID-19 and beyond: why it matters and how to support it. Hunt Institute

Rubin KH, Bukowski W, Parker JG (2006) Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In: Handbook of Child Psychology, Vol. 3. Wiley, New York, NY, pp 619–700

Ryu E, West SG (2009) Level-specific evaluation of model fit in multilevel structural equation modeling. Struct Equ Modeling 16(4):583–601. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510903203466

Sağır A, Eraslan H (2019) Akıllı telefonların gençlerin gündelik hayatlarına etkisi: Türkiye’de üniversite gençliği örneği. OPUS Int J Soc Res 10(17):48–78

Salovey P, Mayer JD (1990) Emotional intelligence. Imag Cogn Personal 9(3):185–211

Seoul Education Research & Information Institute (2020) Seoul education longitudinal study of 2020. Seoul Education Research & Information Institute

Sharma M, Idele P, Manzini A, Aladro C, Ipince A, Olsson G, Banati P, Anthony D (2021) Life in lockdown: child and adolescent mental health and well-being in the time of COVID-19. UNICEF Office of Research-Innocenti

Shi J, Qiu H, Ni A (2023) The moderating role of school resources on the relationship between student socioeconomic status and social-emotional skills: empirical evidence from China. Appl Res Qual Life 18(5):2349–2370

Singh S, Roy D, Sinha K, Parveen S, Sharma G, Joshi G (2020) Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health of children and adolescents: a narrative review with recommendations. Psychiatry Res 293:113429

Singh V, Thurman A (2019) How many ways can we define online learning? A systematic literature review of definitions of online learning (1988-2018). Am J Distance Educ 33(4):289–306

Stathopoulou G, Powers MB, Berry AC, Smits JA, Otto MW (2006) Exercise interventions for mental health: a quantitative and qualitative review. Clin Psychol: Sci Pract 13(2):179

Su J, Wu Z, Su Y (2018) Physical exercise predicts social competence and general well-being in chinese children 10 to 15 years old: a preliminary study. Child Indic Res 11(6):1935–1949

Trott M, Driscoll R, Iraldo E, Pardhan S (2022) Changes and correlates of screen time in adults and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 48:1–29

Vania IG, Yudiana W, Susanto H (2022) Does online-formed peer relationship affect academic motivation during online learning? J Educ Health Community Psychol 11(1):72

Wang F, Zeng LM, King RB (2024) University students’ socio-emotional skills: the role of the teaching and learning environment. Stud High Educ 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2024.2389447

Yu L, Yu JJ, Tong X (2023) Social–emotional skills correlate with reading ability among typically developing readers: a meta-analysis. Educ Sci 13(2):220

Zins JE (2004) Building academic success on social and emotional learning: What does the research say? Teachers College Press

Zins JE, Payton JW, Weissberg RP, O’Brien MU (2007) Social and emotional learning for successful school performance. In: Matthews G, Zeidner M, Roberts RD (eds.). The science of emotional intelligence: knowns and unknowns. Oxford University Press, pp 376–395

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sojin Yoon conceptualized, analyzed, and wrote the paper. Na Yeon Lee analyzed and wrote this paper. Sehee Hong supervised and edited the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study used panel data collected from the Seoul Education Research and Information Institute. The authors did not collect the data directly from the human participants, so ethical approval was not required.

Informed consent

This study does not involve human participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yoon, S., Lee, N.Y. & Hong, S. Problematic smartphone use, online classes, and middle school students’ social-emotional competencies during COVID 19: mediation by lifestyle and peers. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 398 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04689-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-04689-z