Abstract

Mental health research has traditionally focused on isolated contexts, such as medical education, quarantine, or clinical settings, without examining how demographic factors such as age, gender, and education influence mental health across different populations and settings. This lack of cross-context comparison limits our understanding of how demographic and situational factors interact to shape mental health outcomes. To address this gap, we conduct a comparative cross-dataset analysis using three distinct datasets—medical students, quarantined individuals, and psychiatric disordered subjects—analyzing them separately before drawing cross-context comparisons. Through statistical and network-based analyses, we explore how demographic factors shape mental health outcomes in these varied contexts. While isolated analyses reveal important patterns—such as women experiencing heightened stress during quarantine and medical students displaying increased empathy—our comparative approach uncovers novel insights. For instance, the impact of age on mental health differs significantly between quarantine and clinical settings. Additionally, while higher education is generally linked to better mental health, this association does not hold for medical students. These findings highlight the value of cross-dataset analysis in providing richer insights into how external factors impact mental health across diverse contexts, offering valuable guidance for future research and interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Background and literature review

Mental health, defined as “a state of well-being in which every individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community” (World Health Organization, 2014), is essential for overall well-being. Overall well-being, a multidimensional concept encompassing physical, mental, and social health, is often measured by indicators, such as life satisfaction, happiness, and the ability to function effectively in daily life (Huppert and So, 2013). Over the past decade, global mental health research has expanded significantly, with numerous studies emphasizing the role of demographic factors—such as age, gender, and education—in shaping mental health outcomes (Patel et al. 2018).

Much of this research has examined demographic influences within specific settings or populations. For example, studies on gender differences consistently show that women tend to experience higher rates of depression than men, particularly during adolescence (Salk et al. 2017). Similarly, research on age indicates that younger individuals in the United States tend to experience more psychological distress (Twenge et al. 2019), while older adults (50–64 years) tend to experience fewer mental health issues compared to today’s younger adults (18–29 years) (Westerhof and Keyes, 2010). Education has also been identified as a protective factor, with lower levels associated with poorer mental health outcomes (Avendano et al. 2017; Sperandei et al. 2023). However, the impact of education is complex; for instance, intense professional training, such as in medical schools, can adversely affect students’ mental health (Neumann et al. 2011).

While demographic factors play a significant role in mental health, contextual environments further complicate these relationships. Educational institutions, especially high-stress environments such as medical schools, face distinct mental health challenges (Rotenstein et al. 2016). For example, Dyrbye et al. (2014) observed high rates of burnout—including emotional exhaustion and depersonalization—among medical students, particularly in clinical training years. Similarly, the global COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the mental health challenges posed by quarantine measures, with significant variations based on age, gender, and previous mental health history (Brooks et al. 2020). Studies such as Loades et al. (2020) found increased loneliness and depression among young adults (ages 22–29) during quarantine, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions in this age group. Clinical settings reveal that individuals with psychiatric disorders are particularly vulnerable, with factors such as age, education, and gender influencing outcomes (Drew and Funk, 2010). For instance, McGrath et al. (2023) documented increased trauma exposure with advancing age.

Despite the growing body of research on mental health, existing studies often examine demographic factors—such as age, gender, and education—in isolation, without considering how these factors interact across different contexts. For instance, while studies on gender differences consistently show that women experience higher rates of depression than men, they rarely explore how these differences manifest in high-stress environments such as medical schools or during global crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic. Similarly, research on age and education often fails to account for the interplay between these factors and contextual environments. This fragmented approach limits our understanding of how demographic and contextual factors collectively shape mental health outcomes, highlighting the need for more integrated research that spans multiple populations and settings.

Research gaps, question, and contributions

The existing literature reveals several critical gaps. First, there is a lack of cross-dataset analyses that integrate data from multiple contexts to uncover universal trends and context-specific variations. Second, while demographic factors such as age, gender, and education are often studied independently, their combined effects across different populations and settings remain underexplored. Third, the impact of contextual environments—such as medical education, quarantine, and clinical settings—on mental health outcomes is not well understood, particularly in relation to demographic factors.

To address these gaps, our study seeks to answer the following research question: How do demographic and contextual factors interact to influence mental health outcomes across diverse populations, and what patterns emerge when these factors are studied across different contexts?

This study makes the following contributions to the literature:

-

We comprehensively examine mental health across diverse settings, including medical education, quarantine life, and clinical diagnoses, providing a broader understanding of how mental health varies across different contexts.

-

We investigate how multiple demographic factors, such as age, gender, and education, individually influence mental health outcomes, offering insights into the role of each factor across different populations.

-

We conduct a comparative cross-dataset analysis by examining each dataset separately and synthesizing the findings, revealing universal patterns and context-specific variations that are not evident in studies limited to a single context.

By addressing the lack of cross-dataset analyses, the underexplored combined effects of demographic factors, and the impact of contextual environments, our study aims to provide a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of mental health, ultimately informing more effective interventions and policies.

Methods

In this section, we explain how we study mental health patterns using different datasets.

Research methodology

Our study employs a cross-dataset analysis to investigate how demographic and contextual factors influence mental health outcomes across diverse populations. By integrating data from three distinct datasets—focused on medical students, individuals in quarantine, and those with psychiatric disorders—we aim to uncover patterns and insights that are not evident in single-context studies. This approach allows us to examine the interplay of age, gender, and education across different settings, providing a more comprehensive understanding of mental health. The datasets were selected for their complementary contexts and demographic diversity, enabling us to explore both universal trends and context-specific variations. We employ a combination of statistical, network-based, and machine learning methods to analyze the data, ensuring robust and multifaceted insights.

Datasets and heterogeneity analysis

Our research makes use of three separate datasets, each of which provides special insights into experiences with mental health in various settings. The first dataset, the “Medical student mental health” dataset, comprises 886 medical students and includes a comprehensive set of variables. These range from demographic information (age, gender, curriculum year, mother tongue) and lifestyle factors (partnership status, employment) to study habits and health satisfaction. Crucially, it incorporates various psychometric measures, including empathy scores (JSPE, QCAE), depression (CES-D), anxiety (STAI), and burnout (MBI) measures.

The second dataset, “Mental health depression during quarantine life”, consists of 824 participants and focuses on mental health experiences during the COVID-19 quarantine period. It captures demographic information (age, gender, occupation) alongside various indicators of mental health and lifestyle changes during quarantine, such as stress levels, frustration, habit changes, work interest, and mood swings.

The third dataset, “Identification of major psychiatric disorders”, includes 919 participants. It combines demographic information, cognitive measures (IQ), and extensive EEG data. This dataset categorizes participants into major psychiatric disorder groups including specific disorder diagnoses.

These datasets complement each other and allow for the study of mental health experiences across diverse contexts and demographics. Although each dataset was collected with different goals, our study seeks to uncover insights regarding demographic influences on mental health experiences across various contexts. Tables 1–3 present the key attributes of each dataset used in this study. These attributes form the basis of our analyses and results presented in subsequent sections.

To evaluate the comparability of the datasets and explore heterogeneity, we analyzed demographic characteristics and key variables across the three datasets. Significant differences were observed in the age distribution of participants across the datasets. The “Medical student mental health" dataset predominantly includes younger individuals, with a mean age of 22.38 years (standard deviation, SD = 3.30). In contrast, the “Mental health depression during quarantine life" dataset encompasses a broader age distribution, ranging from 16 to above 30 years, reflecting a more diverse sample. The “Identification of major psychiatric disorders" dataset features an even wider age range, with participants spanning different diagnostic groups, such as individuals with alcohol use disorder (mean age = 34.11 ± 11.73) and healthy controls (mean age = 25.77 ± 4.56). These differences emphasize the diverse age profiles across the datasets.

Gender distribution also varies significantly among the datasets. The “Medical student mental health" dataset has a higher proportion of female participants (68.4%), while the “Mental health depression during quarantine life" dataset has a more balanced gender distribution, with 52.67% female and 47.33% male participants. In contrast, the “Identification of major psychiatric disorders" dataset demonstrates gender imbalances that are specific to diagnostic groups. For example, the alcohol use disorder group consists of 79.8% male participants. These gender differences underscore the importance of considering population-specific attributes when interpreting mental health patterns.

The datasets also differ in their sociodemographic characteristics. The “Mental health depression during quarantine life" dataset captures a diverse array of occupational statuses, including business professionals, homemakers, and other sectors, thereby reflecting a broad spectrum of socioeconomic settings. On the other hand, the “Medical student mental health" dataset is more homogenous, comprising students in the early stages of their academic curriculum. This homogeneity offers insights into mental health experiences in a specific professional education setting but limits generalizability across broader populations.

Furthermore, each dataset originates from a distinct context and population, adding a layer of contextual heterogeneity. The “Medical student mental health" dataset focuses on a professional group, highlighting ongoing mental health challenges in an academic environment. The “Mental health depression during quarantine life" dataset captures a unique moment in global history during the COVID-19 pandemic, providing a snapshot of mental health during an acute global crisis. Meanwhile, the “Identification of major psychiatric disorders" dataset emphasizes clinical populations, enabling comparisons between individuals diagnosed with psychiatric conditions and healthy controls. These contextual differences highlight the richness and complementary nature of the datasets.

Given the extensive demographic and contextual variations across the datasets, detailed demographic tables are provided in the Supplementary Material (Supplementary Tables 1–3) for further reference. These tables present comprehensive information, including age distributions, gender compositions, and other key variables, which serve as the basis for the analyses presented in this study.

Reasons for adopting these datasets

The selection of these three distinct datasets was made to provide a comprehensive and multifaceted view of mental health across different contexts, populations, and time frames. Each dataset represents a unique population: the medical student dataset focuses on a specific professional group, the quarantine dataset captures the general population during a global health crisis, and the psychiatric disorders dataset includes both clinical and healthy populations. This diversity enables us to examine how mental health patterns vary across different demographic groups and life circumstances.

Moreover, the datasets originate from three different countries: Switzerland (medical students), Bangladesh (quarantine), and South Korea (psychiatric disorders). These countries represent diverse cultural and socioeconomic settings, allowing for a broader understanding of how mental health is shaped by different demographic and environmental factors. The datasets also span different time periods and contexts. The medical student data provides insights into ongoing mental health challenges in a specific professional education setting, the quarantine dataset captures a unique moment in global history during an acute crisis, and the psychiatric disorders dataset offers a more clinical, long-term perspective on mental health. This temporal diversity allows us to examine both acute and chronic mental health experiences.

Additionally, the datasets encompass different socioeconomic sectors. By including both privileged groups, such as medical students, and potentially more challenged groups, such as psychiatric disordered subjects, alongside the general population captured during quarantine, we can investigate how mental health experiences vary across socioeconomic strata. By combining these datasets, we aim to identify both universal patterns in the demographic and contextual influences on mental health, as well as context-specific variations. This approach improves the generalizability of our findings and underscores the significance of taking specific contexts into account in mental health research and interventions.

Measures

This study employs a combination of standard mental health indicators, such as depression and anxiety, along with additional variables, including burnout, its subcomponents (cynicism and exhaustion), empathy, and social weakness. These variables are selected based on their theoretical and empirical relevance to mental health outcomes.

Depression is assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), a screening tool for depressive symptomatology in the general population. The CES-D has been validated in various studies and is widely used in epidemiological research to identify individuals at risk for depression (Lewinsohn et al. 1997). Anxiety is measured using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), which differentiates between temporary (state) and long-standing (trait) anxiety. The STAI is a validated instrument commonly used in clinical and research settings to assess anxiety levels (Marteau and Bekker, 1992).

Burnout is operationalized as a work-related syndrome consisting of three core components: exhaustion, cynicism (or depersonalization), and a reduced sense of professional efficacy (Maslach and Leiter, 2016; Maslach et al. 2001). While burnout is analyzed as a composite variable, cynicism and exhaustion are also examined individually to explore their distinct contributions to mental health outcomes (Lubbadeh, 2020). Exhaustion reflects the depletion of emotional and physical resources, whereas cynicism captures a detachment or negative attitude toward work and interpersonal relationships. In this study, burnout subcomponents showed significant associations with depressive symptomatology, supporting their relevance as predictors of mental health outcomes.

Empathy, assessed through the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy (JSPE) and Questionnaire of Cognitive and Affective Empathy (QCAE), encompasses both cognitive and affective dimensions. It plays a significant role in interpersonal functioning and emotional regulation. However, as O’Connor et al. (2002) and Schreiter et al. (2013) noted, excessive or insufficient empathy may increase the risk of depression, especially when combined with low emotional self-regulation (O’Connor et al. 2002; Schreiter et al. 2013). The relationship between empathy and depression is further influenced by emotion dysregulation, with quadratic associations observed (Berking and Wupperman, 2012; Tully et al. 2016).

Performance variables, such as academic and occupational outcomes, are assessed through self-reported measures of productivity and satisfaction. Prior research highlights the link between burnout and reduced performance, emphasizing the critical role of mental health in maintaining professional efficacy (Dyrbye et al. 2006). Social weakness refers to difficulties in maintaining social connections or networks. During the pandemic, such isolation exacerbated the risk of depression and anxiety, as supported by studies on social phobia and its associated disabilities (Wittchen et al. 2000).

While depression and anxiety were measured only in the “Medical student mental health" dataset, burnout and empathy were specific to the same dataset. In contrast, variables such as stress, coping struggles, and social weakness were unique to the “Mental health depression during quarantine life" dataset, while clinical diagnostic categories were the focus of the “Identification of major psychiatric disorders" dataset.

Analytical methods used for each dataset

Since we worked with similar yet distinct datasets, we employed a range of analytical methods to address our research question effectively. All analyses were conducted using Python (version 3.12.3) in Jupyter Notebook (Kluyver et al. 2016), utilizing libraries such as pandas (McKinney et al. 2010), statsmodels (Seabold and Perktold, 2010), scipy (Virtanen et al. 2020), networkx (Hagberg et al. 2008), seaborn (Waskom, 2021), and matplotlib (Hunter, 2007) for data manipulation, statistical analysis, and visualization.

For the “Medical student mental health” dataset, we begin with descriptive statistics to find the mean, standard deviations, and distributions for different demographic and psychometric factors using pandas (McKinney et al. 2010). Then, we use Pearson’s correlation (via scipy.stats.pearsonr()) (Virtanen et al. 2020) analyses, regression plots, and scatter plots to show the connections between signs of mental distress (such as depression, anxiety, exhaustion, and cynicism) and academic efficacy. Additionally, multiple linear regression analyses built using statsmodels (Seabold and Perktold, 2010) assessed how these mental health indicators were influenced by factors such as curricular year and gender (Carrard et al. 2022). This approach allowed for a focused analysis of individual mental health outcomes, which was the primary objective, rather than modeling the interrelationships between outcomes. We also perform linear regressions, using each empathy indicator as an independent variable and each mental health and stress indicator as a dependent variable (Carrard et al. 2022; Damiano et al. 2017). To explore the relationships between key variables more comprehensively, we perform a correlation-based network analysis using networks (Hagberg et al. 2008), where Pearson correlations are computed between all attribute pairs. In the resulting network, green edges indicate direct positive correlations, while red edges signify direct negative correlations, and the strength of the correlation is represented by the thickness of the edges, with thicker edges corresponding to stronger correlations. To handle multiple comparisons, we apply the Benjamini–Hochberg correction (∣r∣ ≥ 0.25 and p < 0.05) to control the false discovery rate (via statsmodels.stats.multitest.multipletests()) (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995).

We used descriptive statistics to summarize demographic variables and mental health indicators during the analysis of the “Mental health depression during quarantine life” dataset using pandas (McKinney et al. 2010). Since most of the attributes in the dataset are categorical, we use chi-square tests (scipy.stats.chi2_contingency()) (Virtanen et al. 2020) to check for any links between them. We also utilize logistic regression models to evaluate the probability of mental health issues in relation to demographic and isolation-related factors with the help of statsmodels (Seabold and Perktold, 2010), though no significant results are found (Ling et al. 2023). Logistic regression was selected here due to the binary nature of the mental health outcomes in this dataset, which aligns with its primary purpose of modeling categorical dependent variables. We also conducted correlation studies to explore how various mental health indicators related to changes in habit. Finally, we employ the association network approach using networkx (Hagberg et al. 2008), based on chi-square tests p < 0.07 to capture near-significant associations between categorical variables. This method provided a visual representation of the relationships between mental health indicators and quarantine-related factors. Here again, the strength of the correlation is represented by the thickness of the edges, with thicker edges corresponding to stronger correlations.

For the “Identification of major psychiatric disorders” dataset, we focus on demographic and psychiatric disorder-related variables, excluding the EEG data. We use descriptive statistics to summarize demographic and clinical characteristics using pandas (McKinney et al. 2010). Additionally, we perform ANOVA (statsmodels.api.anova_lm()) (Virtanen et al. 2020) to compare IQ scores, education levels, and age across different psychiatric disorders, followed by Tukey’s HSD test (Seabold and Perktold, 2010) for subsequent comparisons between specific disorder groups (Mungas, 1983; Nanda et al. 2021). Finally, a correlation-based network analysis was performed using networkx (Hagberg et al. 2008) to examine the relationships between demographic variables and psychiatric disorders, with significant correlations (∣r∣ ≥ 0.15 and p < 0.05) visualized as a network structure to identify key interconnected variables. Green and red edges in this network represent positive and negative correlations, respectively, helping to identify key interconnected variables.

To improve causal inference beyond simple associations, we applied advanced techniques such as propensity score matching (PSM) and instrumental variable (IV) analysis. For example, we used PSM to balance covariates and estimate the causal effects of gender, age, and education on mental health outcomes across the datasets. In the “Medical student mental health” dataset, IV analysis was implemented by using curriculum year as an instrument for age to estimate its causal effect on outcomes such as depression and total empathy. Recognizing the importance of intersectionality, we have extended our analysis to include interaction terms in our regression models–specifically, we have modeled interactions among gender, education, and stress (or related proxies) in the “Medical student mental health” dataset, as well as analogous models in our other two datasets. Additionally, we re-estimated these models using Bayesian methods, which allowed us to quantify uncertainty in our estimates via posterior distributions and credible intervals. To further capture non-linear relationships among predictors, we applied machine learning techniques across the datasets. For the continuous outcomes in the “Medical student mental health” dataset and “Identification of major psychiatric disorders” dataset, Random Forest regressors were used—with hyperparameter tuning via GridSearchCV—to capture complex interactions. For the categorical outcomes in the “Mental health depression during quarantine life” dataset, we employed Random Forest classifiers (with hyperparameter tuning) to predict outcomes.

Results

We conducted a comprehensive analysis across three distinct datasets, encompassing a total of 2629 participants. We present the detailed demographic, behavioral, and mental health characteristics obtained from these groups.

Demographic influences on mental health

Demographic factors such as age, education, and gender are key factors in shaping mental health outcomes. Understanding how these variables interact with mental health across different contexts provides valuable insights into the specific challenges faced by various groups. In this section, we examine the impact of age, education, and gender on mental health by analyzing patterns across our three datasets: Medical student mental health, Mental health depression during quarantine life, and Identification of major psychiatric disorders.

Age-related findings

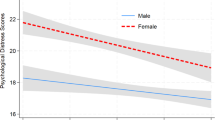

Our analysis reveals that age significantly influences mental health experiences across all three datasets, though the nature of this influence varies by context. Although direct age-related results were challenging to interpret due to limited age variability among medical students in the “Medical student mental health” dataset, progression through curriculum years allows us to deduce age-related trends. As students advance in their training, empathy levels increase for both males (Slope = 1.59) and females (Slope = 1.48), while behavioral empathy shows a slight decline (Males: Slope = −0.16; Females: Slope = −0.03). Interestingly, cynicism levels also rise over time (Males: Slope = 0.33; Females: Slope = 0.14), showing an age-related trend in emotional and professional experiences. Figure 1 highlights these trends, showing that while empathy increases, both depression and anxiety slightly decrease over time, with female students consistently reporting higher empathy scores. The propensity score matching (PSM) analysis showed that curriculum year significantly impacts mental health outcomes, with higher depression (t = −3.84), increased empathy (t = 3.18), and higher anxiety (t = −2.66) among medical students. To maintain consistency for cross-dataset comparison, we also categorized ages into broader groups and included this additional analysis as a supplementary figure (Supplementary Fig. 1). Detailed results of the PSM analysis—including t-values, confidence intervals, and significance levels for each outcome—are provided in Supplementary Table 4, which is included in the Supplementary File under the ‘Propensity Score Matching (PSM) Analysis’ section. To address potential endogeneity concerns regarding the effect of age on mental health outcomes, we employed a two-stage least squares (2SLS) instrumental variable (IV) approach. In our model, age is treated as the endogenous regressor and is instrumented by year, while controlling for language (glang), partnership status (part), employment (job), study hours (stud_h), self-reported health (health), and psychometric scores (psyt). The IV estimation results indicate that age has a statistically significant effect on several mental health outcomes. For depression, the coefficient on age is −0.98 (t = −4.74, p < 0.001), suggesting that an additional year in age is associated with a reduction in depression scores by ~0.98 units. Similarly, for anxiety, the coefficient on age is −0.47 (t = −2.14, p = 0.032), indicating that increasing age corresponds with a significant decrease in anxiety. In contrast, for total empathy, the coefficient on age is 1.37 (t = 7.09, p < 0.001), demonstrating that older students exhibit higher empathy levels. However, for efficacy, the effect of age is not statistically significant (coefficient = 0.08, t = 0.89, p = 0.371), suggesting no meaningful association between age and perceived efficacy. These results indicate that later-year students have significantly lower depression and anxiety scores, as well as higher total empathy scores compared to early-year students.

Trends in total empathy, depression, and anxiety across different curriculum years, separated by gender (Dataset: Medical student mental health (Carrard et al. 2022)).

The “Mental health depression during quarantine life” dataset reveals a statistically significant association between age and social weakness (p = 0.038). The distribution of social weakness varies across age groups, with the highest proportion of individuals reporting social weakness observed in the 25–30 age group. This finding highlights a potential increased vulnerability specifically during the transition from young adulthood to later adulthood, rather than suggesting a linear increase with advancing age. Figures 2 and 3 illustrate this relationship across different age groups. Additionally, a near-significant association between age and days spent indoors (p = 0.064) hints at age-related differences in quarantine behaviors. To further assess whether these associations reflect a causal effect after accounting for potential confounders, we conducted a propensity score matching (PSM) analysis. The t-test for social weakness yielded a t-value of 2.35 (p = 0.0189), indicating a statistically significant difference between the matched groups. In contrast, the difference in Days Indoors (t = 1.95, p = 0.0511) was only marginally significant. These findings suggest that after balancing on key covariates, individuals in the later age groups exhibit slightly higher levels of social weakness and tend to spend more days indoors during quarantine compared to those in the younger age groups. Detailed results of the PSM analysis are provided in Supplementary Table 6, which is included in the Supplementary File under the ‘Propensity score matching (PSM) analysis’ section.

Stacked bar plot of age by social weakness (Dataset: Mental health depression during quarantine life (Amin et al. 2024)).

Contingency table of age and social weakness (Dataset: Mental health depression during quarantine life (Amin et al. 2024)).

In the “Identification of major psychiatric disorders” dataset, age significantly influences the occurrence of various mental health issues. Trauma and stress-related disorders (TSD) are more frequently experienced by older individuals (mean age = 36.36 years), while younger individuals (mean age = 25.77 years) are typically observed among healthy controls (HC). Other disorders include addictive disorder (AddiD), anxiety disorder (AnxD), mood disorder (MD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), and schizophrenia (S). Table 4 illustrates the relationship between these psychiatric disorders and their mean ages. It presents the mean age of participants for each disorder alongside the t-values and p-values from comparisons to the healthy control group. Additionally, ANOVA results indicate significant age differences between groups (F = 8.82, p < 0.0001), with Tukey’s HSD test revealing further age-based distinctions among various disorders. Figure 4 presents a box plot of age distribution across psychiatric disorders, offering a visual representation of both overlaps and unique patterns related to age. The interquartile ranges, medians, and the presence of outliers provide additional insights into the variation in age among individuals with different disorders, highlighting both the commonalities and unique age-related trends across these psychiatric conditions. Furthermore, to assess the causal impact of psychiatric disorder status on age while adjusting for potential confounders, we conducted a propensity score matching (PSM) analysis. In this analysis, individuals with trauma and stress-related disorders (treatment group) were compared to healthy controls (control group) using sex and education as covariates. The matching yielded a mean age difference of 11.34 years between the groups. An independent t-test revealed a t-value of 8.54 (p < 0.0001), confirming that, even after controlling for confounding variables, individuals with trauma and stress-related disorders are significantly older than healthy controls.

Box plot showing age distribution by psychiatric disorder (Dataset: Identification of major psychiatric disorders (Park et al. 2021)).

Gender-related findings

In the medical student mental health and quarantine life dataset, differences between men and women were particularly noticeable.

Within the “Medical student mental health” dataset, we observe distinct gender-specific trends. While total empathy increases over time for both genders, males show a slightly higher rate of growth. In contrast, behavioral empathy exhibits a small decline for both genders, although this decrease is more pronounced in males. Notably, emotion recognition correlates differently by gender: depression positively correlates with emotion recognition in men but negatively correlates in women. Cynicism levels increase for both genders; however, this increase appears to be more pronounced in men. Differences in academic efficacy are also notable, with men experiencing slight improvements while women face minor declines. Finally, the effects of empathy on mental health vary by gender: affective empathy increases anxiety and despair in women, whereas cognitive empathy reduces anxiety in men. The linear regression slopes, as shown in Table 5, demonstrate how mental health variables change differently for men and women, revealing distinct gender-specific trends across the data. To further validate our associations, we conducted a propensity score matching (PSM) analysis comparing mental health outcomes between genders. In this analysis, we see gender differences significantly affect mental health outcomes, with higher depression (t = 4.30), efficacy (t = 2.70), empathy (t = 3.07), and anxiety (t = 5.45) among medical students (detailed results of PSM analysis are provided in Supplementary Table 5, which is included in the Supplementary File under the ‘Propensity score matching (PSM) analysis’ section).

The analysis of “Mental health depression during quarantine life” dataset reveals a statistically significant association between gender and coping difficulties during quarantine (χ2 = 4.125, P-value = 0.042). Specifically, a higher percentage of women (39%) reported difficulties coping with everyday issues compared to men (32%). This suggests that women may have faced greater challenges in managing everyday issues during quarantine compared to men. Although not highly significant (χ2 = 4.716, p = 0.095), females are more likely to report increased stress during quarantine. Moreover, there is a near-significant association indicating that women may undergo more significant changes (χ2 = 5.823, P-value = 0.054). Figure 5 shows the gender comparisons for both growing stress and coping struggles during quarantine, highlighting the differences in how various genders experienced stress and dealt with struggles during the same period. To further assess the effect of gender on these outcomes while adjusting for potential confounders, we conducted a propensity score matching (PSM) analysis. After matching, the comparison of the outcome Coping Struggles yielded a t-value of 3.21 (p = 0.0014), while the outcome Growing Stress resulted in a t-value of −0.87 (p = 0.3870). These results are summarized in Supplementary Table 7.

a shows gender-wise responses to increasing stress during quarantine, categorized into Yes, Maybe, and No. Female participants reported more frequent experiences of growing stress than males. b presents gender-wise differences in coping struggles, comparing how males and females responded to difficulties in managing daily challenges during the quarantine period. A higher proportion of females reported coping struggles compared to males.

In the “Identification of major psychiatric disorders” dataset, we observe that, except for trauma and stress-related disorders, the number of male patients is higher across the remaining six disorders, as shown in Fig. 6. However, despite this distribution, we do not find any significant correlation between gender and mental health. To fully understand the impact of gender on mental health in this dataset, further studies or additional data are required.

Bar chart showing the distribution of male and female patients by psychiatric disorder (Dataset: Identification of major psychiatric disorders (Park et al. 2021)).

Educational background influences

As medical students progress through their training, several measures of their mental health and academic performance change in different ways, as observed through the analysis of curriculum-year-based trends in the “Medical student mental health” dataset. Notably, changes in academic efficacy differ based on gender. While total empathy and cynicism tend to increase with advancing curriculum years, behavioral empathy shows a decline. As discussed earlier, curriculum year indirectly reflects age and accumulated educational experiences. Thus, these findings suggest that the medical education process itself, along with age-related experiences, plays a vital role in shaping students’ mental health outcomes and professional attitudes. Figure 7 illustrates the relationship between academic efficacy and various mental health indicators (depression, anxiety, exhaustion, and cynicism) across genders. As the figure demonstrates, the connection between academic efficacy and these mental health measures not only varies by indicators but also differs between genders.

a Scatterplot of academic efficacy vs. depression, color-coded by gender. A negative trend is observed: higher depression scores are associated with lower efficacy. b Scatterplot of efficacy vs. anxiety shows a similar inverse relationship, with males and females distributed differently along the axis of anxiety. c Scatterplot of efficacy vs. exhaustion indicates that students with higher exhaustion scores report lower academic efficacy. d Scatterplot of efficacy vs. cynicism reveals that increased cynicism is associated with reduced academic efficacy, with gender-specific clustering across efficacy levels.

In the “Mental health depression during quarantine life” dataset, the data do not explicitly address educational background. However, future studies should explore how education influences mental health during quarantine.

The “Identification of major psychiatric disorders” dataset reveals that higher levels of education are associated with improved mental health outcomes. For instance, healthy controls have the highest average education level (14.91 years), while people with schizophrenia show the lowest (12.84 years). The ANOVA results show significant differences in education levels (F = 7.33, p < 0.0001), with Tukey’s HSD test confirming notable differences between healthy controls and various disorders, especially schizophrenia. Table 6 presents the association between different psychiatric disorders and mean education levels. The table displays the mean years of education for each disorder along with the corresponding t-values and p-values from t-tests against the healthy control group. Furthermore, to assess whether the observed differences in education levels persist after adjusting for potential confounders, we conducted a propensity score matching (PSM) analysis comparing individuals with schizophrenia (treatment group) to healthy controls (control group). Using sex and age as covariates, the matching procedure yielded a matched sample in which the mean difference in education was −2.23 years. An independent t-test produced a t-value of −6.64 (p < 0.0001), indicating that, even after adjusting for confounders, individuals with schizophrenia have significantly lower educational attainment compared to healthy controls.

These analyses reveal the nuanced and sometimes unexpected ways that age, education, and gender interact to shape mental health outcomes across different contexts. To highlight the key insights, Table 7 provides a summary of the most important findings from our datasets, emphasizing the complexity of demographic influences on mental health.

Impact of mental health issues on performance

Mental health issues such as depression, anxiety, and exhaustion significantly impact both academic and work performance. Our analysis across three distinct datasets reveals that the nature and extent of this impact vary depending on the context, be it medical school, quarantine conditions, or broader psychiatric conditions.

In the “Medical student mental health” dataset, mental health problems are tightly interrelated. Anxiety and depression show a high connection (72%), while depression strongly correlates with exhaustion (61%), and exhaustion links with anxiety (53%). These statistics highlight the frequent co-occurrence of these mental health challenges. Notably, these issues negatively influence academic efficacy. For instance, anxiety (−46%), exhaustion (−48%), and cynicism (−57%) all correlate with lower academic efficacy, indicating that as these mental health issues increase, academic performance tends to decrease. Figure 8 highlights these connections, emphasizing how mental health challenges are often interconnected and affect academic success. Interestingly, gender differences further influence these relationships. For male students (−52%), anxiety has a stronger negative impact on academic performance compared to females (−45%), whose academic performance only slightly decreases over time. Conversely, cynicism tends to rise more in males as time goes on. These patterns suggest that while mental health issues harm all genders academically, the effects manifest differently based on gender.

Correlation heatmap among health issues and academic efficacy (Dataset: Medical student mental health (Carrard et al. 2022)).

In our analysis of the “Mental health depression during quarantine life” dataset, we find that gender has a significant impact on how people cope with mental health challenges during the COVID-19 quarantine. Women report greater coping difficulties, higher stress levels, and more significant weight changes compared to men. These findings suggest that the quarantine worsens existing mental health issues for women, leading to a greater negative impact on their work performance. Table 8 summarizes these gender differences. Additionally, frustrations during quarantine weakly correlate with past mental health issues and social vulnerability, with p-values of 0.098 and 0.059. This suggests that people with a history of mental health problems or greater social weakness may be more susceptible to increased frustration, further affecting their interest and performance at work during difficult times such as quarantine.

In our study of the “Identification of major psychiatric disorders” dataset, we explore the connections between mental health, education, and cognitive functioning, which may indirectly impact work performance(Lerner and Henke, 2008). Age emerges as a critical factor, with older individuals more likely to have trauma and stress-related disorders. Education also plays a significant role, with healthy controls tending to have higher levels of education, while individuals with schizophrenia exhibit the lowest levels of educational attainment. IQ further contributes to these distinctions, with healthy controls exhibiting higher IQ scores, reflecting better cognitive functioning. Although our dataset does not contain direct measures of work performance, these factors—education and IQ—are often associated with an individual’s ability to perform in academic or professional settings (Strenze, 2007). Figure 9 presents a box plot, displaying the IQ distribution across different psychiatric disorders, illustrating cognitive differences associated with various mental health conditions. The plot shows median IQ scores, interquartile ranges, and potential outliers for each disorder group, providing a clear view of cognitive functioning across these psychiatric categories.

Box plot showing IQ distribution by psychiatric disorder (Dataset: Identification of major psychiatric disorders (Park et al. 2021)).

Thus, the connection between mental health and performance is multifaceted, influenced by factors such as age, gender, education, and the specific challenges of quarantine or academic stress. Table 9 presents a summary of the interactions between mental health issues and performance in various contexts, including medical education, COVID-19 quarantine, and psychiatric diseases. The most vital signs of mental health such as depression, anxiety, exhaustion, trouble adjusting, weight changes, and IQ levels are included in the table. Understanding these characteristics enables the design of specific strategies to assist individuals in coping with mental health issues either in their workplace and educational environment.

Network analysis across datasets

In this section, we explore the network relationships among various attributes in the three datasets. By analyzing the correlation and association networks, we gain a clearer view of how different variables are interconnected.

In the “Medical student mental health” dataset, we identify strong interconnections among mental health and academic factors through a correlation-based network analysis. Notably, three distinct maximal cliques emerge in the network. The first clique consisting of five entities—depression, anxiety, cynicism, efficacy, and exhaustion—forms a completely interconnected sub-network. This clique highlights the strong interrelationship between mental health issues and their impact on academic efficacy. The second clique includes depression, anxiety, and affective empathy, highlighting how emotional response links with common mental health challenges. The third clique involves total empathy, cognitive empathy, and affective empathy, reflecting the internal cohesion among different empathy types. The maximum clique within this dataset is the first one, indicating the most significant subset of correlated mental health issues. Figure 10a visualizes the correlation network, while Fig. 10b highlights the maximal and maximum cliques.

a Correlation network of key variables (e.g., depression, anxiety, empathy, efficacy), where edge color (green/red) indicates positive/negative correlations and thickness reflects strength. b Maximal cliques (purple) within the network; the largest (blue) clique highlights strong interconnections among depression, anxiety, exhaustion, cynicism, and efficacy, underscoring their impact on academic performance.

In the Mental Health Quarantine dataset, the association network reveals several significant connections between categorical variables. Multiple small maximal cliques are identified, including [Social Weakness, Age], [Social Weakness, Quarantine Frustrations], [Coping Struggles, Gender], [Growing Stress, Changes Habits], [Days Indoors, Age], [Weight Change, Occupation], and [Weight Change, Gender]. Although these cliques are small in size, they indicate important associations between social and mental health variables during the quarantine period. Figure 11a shows the association network, with thicker edges representing stronger associations.

a Association network from the quarantine dataset based on chi-square values, where edge thickness indicates the strength of association between categorical variables (e.g., stress, age, gender, coping struggles). b Correlation network from the psychiatric disorders dataset, where green/red edges show positive/negative correlations and thickness reflects strength; smaller cliques reveal key links (e.g., Age–Education, Disorder–IQ).

For the “Identification of major psychiatric disorders” dataset, the correlation network shows several notable connections among key demographic and clinical variables. Maximal cliques of size two include relationships such as [Education, Age], [Education, IQ], [Main Disorder, Age], and [Main Disorder, IQ]. Although the cliques are small, they reveal important links between educational attainment, cognitive function, and psychiatric disorders. Figure 11b illustrates the correlation network, showing both positive and negative relationships between these attributes.

Machine learning analysis for capturing non-linear interactions

In order to explore non-linear interactions among demographic factors and mental health outcomes, we applied machine learning models to each of our three datasets. Specifically, we used Random Forest regression for continuous outcomes and a Random Forest classifier for categorical outcomes. The key performance metrics are summarized in Table 10.

These results indicate that Random Forest models capture non-linear patterns in our data, albeit with modest predictive performance. Given the limited sample sizes, the performance metrics are within the expected ranges for complex mental health outcomes. Moreover, these analyses complement our primary econometric methods and provide additional insights into the interaction effects among demographic factors and mental health outcomes. Detailed model specifications, hyperparameter tuning results, and additional diagnostics are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Intersectional analysis and Bayesian modeling

To capture potential non-linear interactions and intersectional effects on mental health outcomes, we extended our analyses by incorporating interaction terms into our regression models and re-estimated them using a Bayesian framework. For the Medical Student Mental Health dataset, our model for depression included interactions among curriculum year, sex, study hours (stud_h), and stress (psyt). The OLS results (Table 11) indicate that, while the main effects of year and sex are statistically significant, most of the interaction terms (e.g., sex:stud_h:psyt) are not significant individually. The Bayesian analysis, which provides posterior estimates and credible intervals, confirms these findings and quantifies the uncertainty in the estimates.

In the Mental Health Depression During Quarantine Life dataset, we modeled the outcome Social Weakness using interactions among Age, Gender, and Growing Stress. Although the overall model explained a modest portion of the variance (R2 = 0.030), one interaction term (Age × Growing Stress for a particular age group) was significant (t = 2.11, p = 0.035), indicating that the impact of growing stress on social weakness may vary by age.

Similarly, in the Identification of Major Psychiatric Disorders dataset, an OLS regression predicting education incorporated interactions among age, sex, and disorder status. The results (Table 11) show that age and sex are significant predictors of educational attainment, and the interaction between age and sex, although not highly significant (t = 1.75, p = 0.080), suggests that the effect of age on education may differ by gender.

Discussion

This study examines mental health across different groups: medical students, people in quarantine, and those with psychiatric disorders. It reveals several interesting trends that both confirm existing knowledge and provide new insights. Our primary focus is on how various demographic factors, including age, gender, and education, influence individual mental health. Although there is substantial research on mental health and its determinants, relatively few studies have conducted a comparative analysis across multiple contexts simultaneously (Kessler et al. 2015). We address this gap in our study and gain several interesting insights.

Data analysis over the datasets in isolation

Our analysis of medical students reveals that empathy generally increases over time for both men and women as they progress through their training. This finding contrasts with previous research by Hojat et al., which suggested a decline in empathy during medical school (Hojat et al. 2009). While some studies indicate that women tend to have higher empathy levels overall (Baig et al. 2023), our findings suggest a relatively greater increase in male students’ empathy scores over time. This does not contradict the established literature but instead highlights potential shifts in empathy development during the observed period. This could suggest that the intense environment of medical school influences gender differently in terms of emotional engagement. Additionally, depression levels tend to decrease over time in both genders, but female students report higher levels of anxiety and depression overall. This matches other studies showing that women are generally more prone to stress and anxiety (Salk et al. 2017). Interestingly, cynicism increases as students advance through medical school, which aligns with findings by Kachel et al. (2020), who documented a rise in cynicism among medical students over time. This trend further supports the observations of Dyrbye et al. (2014), who found that burnout, including emotional exhaustion and depersonalization (a form of cynicism), intensifies throughout medical training.

Our quarantine dataset reveals that individuals transitioning from early to late adulthood are more vulnerable to social isolation during quarantine. This finding aligns with findings by Loades et al. (2020), who reported that young adults (ages 22–29) are at heightened risk for increased loneliness and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, the increased levels of stress and coping difficulties observed in women during quarantine are consistent with the findings of Arcand et al., and Salk et al., on gender differences in stress and depression (Arcand et al. 2023; Salk et al. 2017). The reasons for this difference could include factors such as increased care giving responsibilities or higher rates of job loss among women during the pandemic, as discussed by Power (2020).

In our analysis of the psychiatric disorders dataset, we find that older individuals are more susceptible to trauma and stress-related disorders in clinical populations, which aligns with studies indicating high lifetime exposure to traumatic events among older adults (Magruder et al. 2022; Thorp et al. 2013). While this finding contrasts with previous research suggesting older adults generally have better mental health (Charles and Carstensen, 2010), it aligns with the observation of Udupa et al. regarding heightened trauma in older populations (Udupa et al. 2023). Moreover, this trend indicates that the accumulation of life stressors over time may increase vulnerability to such disorders, a notion supported by the research of McGrath et al. on age-related mental health risks (McGrath et al. 2023). Education also plays a vital role in mental health outcomes. Individuals with higher education levels generally exhibit better mental health, consistent with the work of Araya et al. which suggests that education may offer protective benefits against mental illness (Araya et al. 2003). However, we also observed significant educational disparities across mental health disorders, with individuals suffering from schizophrenia having the lowest education levels. This disparity highlights the complex relationship between education and mental health, as discussed by Cutler and Lleras-Muney (2006).

Cross-dataset analysis

Our approach of using multiple datasets gives a broader view of mental health than studies that look at just one group. This builds on work such as cross-national studies of Kessler et al. (2015) By looking at mental health in different groups—such as medical students, the general population during quarantine, and people with psychiatric disorders—we can compare our findings and make our conclusions stronger. This approach aligns with the concept of triangulation in social research, where the use of multiple data sources enhances the validity and reliability of the findings (Renz et al. 2018).

Stress as a universal factor

Across all datasets, stress consistently emerges as an important factor associated with mental health outcomes. However, its manifestations differ depending on context. In the quarantine dataset, stress and frustration contribute to changes in habits, social isolation, and difficulties coping, particularly among older individuals and women. These findings align with the work of de Maio Nascimento et al., and Kolakowsky-Hayner et al. who both reported significant increases in stress, anxiety, depression, and loneliness among individuals during quarantine (de Maio Nascimento et al. 2023; Kolakowsky-Hayner et al. 2021). Additionally, Kolakowsky-Hayner et al. found that women experienced higher levels of emotional distress than men. In the medical student dataset, stress is closely linked to burnout levels, consistent with prior evidence that prolonged academic stress can significantly impact the psychological well-being of medical students (Ruzhenkova et al. 2018). Stress also plays a crucial role in psychiatric disorders, particularly among older individuals, where it intensifies trauma and stress-related conditions.

Gender differences in different contexts

Gender differences are consistent across datasets, with women generally reporting higher levels of stress and mental health challenges. This is particularly evident in the quarantine and medical student datasets, supporting broader literature on gender disparities in mental health (Arcand et al. 2023; Power, 2020; Salk et al. 2017). In the medical student dataset, we observe a trend where the rate of increase in empathy is slightly higher for male students compared to female students. However, this pertains specifically to the change over time and does not contradict Baig et al.’s well-documented finding that female students generally exhibit higher absolute levels of empathy overall (Baig et al. 2023). This finding suggests that the intense pressure of medical school might impact men and women in different ways.

Age and mental health

In the psychiatric disorders dataset, older individuals are more prone to trauma and stress-related disorders, possibly due to accumulated life stressors over time (McGrath et al. 2023). In contrast, the quarantine dataset shows that middle-aged adults (25–30 years) report the highest levels of stress, suggesting that different life stages present unique challenges during crises. This complexity complements the Two Continua Model proposed by Westerhof and Keyes, which recognizes that mental health and mental illness can coexist and fluctuate across the lifespan (Westerhof and Keyes, 2010). Interestingly, in the medical student dataset, while we do not find a direct relation between mental health and age, progression through the curriculum suggests some age-related effects, such as increasing empathy and cynicism. These patterns align with studies by Kachel et al. (2020), who found increasing cynicism among medical students but contrast with findings by Hojat et al. (2009), who reported a decline in empathy throughout medical training.

The role of education

Education plays both a protective and negative role in mental health. In the psychiatric disorders dataset, higher education levels are correlated with better mental health outcomes, supporting findings by Araya et al. (2003) and Sperandei et al. (2023). So, education can serve as a protective factor against mental health issues by providing coping mechanisms that contribute to one’s well-being as proposed by Cutler and Lleras-Muney (2006). In contrast, the medical student dataset reveals that despite high levels of education, students experience increasing depression and burnout as they progress through their training, mirroring findings by Dyrbye et al. (2006) and Neumann et al. (2011) These findings suggest that educational interventions need to address both the protective and detrimental aspects of professional training, particularly in fields such as medicine.

By analyzing diverse datasets across various age groups, we gain valuable insights into how mental health evolves over the lifespan, supporting Cicchetti and Toth’s work on developmental psychopathology (Cicchetti and Toth, 2009). Our multi-dataset approach aligns with the emphasis on big data’s role in mental health research, as highlighted in the scoping review by Ahmed et al. (2022). This method also balances generalizability and specificity, addressing the over reliance on WEIRD populations in mental health studies, as noted by Henrich et al. (2010). Krys et al. further highlight this bias and advocate for better global representation, which our diverse datasets partially address (Krys et al. 2024). Table 12 provides an overview of the information available from the three datasets used in this study, while Table 13 summarizes the key findings from our cross-dataset analysis, highlighting the complex interplay of stress, gender, age, and education across different contexts in mental health.

Counterintuitive findings

Our analysis reveals several unexpected results across the three datasets, challenging some common assumptions about mental health and demographic influences. In the medical student dataset, we observe a contradictory trend in empathy development. While total empathy grows over time for both genders, behavioral empathy slightly declines, especially in men. This aligns partially with the findings of Hojat et al. (2023) on empathy. Another unexpected result is that men with higher emotional recognition experience more depression, while women with strong emotional recognition report lower levels of despair. This challenges the assumption that better emotional awareness universally protects against mental health issues, suggesting gender differences in emotional regulation (Bhatia and Shetty, 2023; Hojat et al. 2009). Additionally, we find that cognitive empathy reduces anxiety in men, while affective empathy increases anxiety and depression in women, indicating that the emotional burden of empathy may differ by gender.

In the quarantine dataset, we find that middle-aged individuals show greater social vulnerability, contradicting the notion that they are better equipped to handle stress due to life experience. This observation is consistent with the findings of Loades et al. (2020), who identified young adults (ages 22–29) as being particularly vulnerable to heightened levels of loneliness and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, there is a strong link between growing stress and changing habits during quarantine. While stress often leads to habit changes, the strong association during quarantine suggests that stress may have a bigger impact on behavior change during extraordinary circumstances than previously thought (Alon-Tirosh et al. 2021).

The psychiatric disorders dataset reveals that trauma and stress-related disorders are more common among older individuals, challenging the belief that these primarily occur in younger people (Twenge et al. 2019). This finding suggests that accumulated life stressors might contribute to greater vulnerability in older adults (McGrath et al. 2023). We also find that individuals with schizophrenia have significantly lower levels of education, further highlighting the adverse impact of severe mental health conditions on educational attainment (Sperandei et al. 2023). Interestingly, individuals with addiction or OCD tend to have higher IQs than those with schizophrenia or anxiety disorders. This observation challenges certain prevalent assumptions in the literature that specific addictive disorders or behaviors are generally associated with impaired cognitive functioning (Karpinski et al. 2018).

In our cross-dataset analysis, several key findings emerge. For instance, stress disproportionately impacts middle-aged individuals during quarantine, yet older adults in clinical settings show higher vulnerability to trauma, challenging conventional views on how age affects stress resilience (de Maio Nascimento et al. 2023; McGrath et al. 2023; Neumann et al. 2011). Additionally, women across both the medical student and quarantine datasets report higher stress levels, challenging the assumption that women, due to their caregiving roles or perceived emotional resilience, might cope better in emotionally demanding situations (Arcand et al. 2023; Power, 2020; Salk et al. 2017). Moreover, while higher education is generally associated with better mental health in the psychiatric dataset, medical students exhibit increased cynicism and burnout despite their educational success, undermining the belief that education always serves as a protective factor (Cutler and Lleras-Muney, 2006; Dyrbye et al. 2006; Sperandei et al. 2023).

These findings underscore the complexity and unexpected patterns in mental health outcomes across different demographic groups and contexts. To provide a clear overview, Table 14 summarizes the key counterintuitive findings from our analysis.

Comparison with existing literature

Our study offers a comprehensive examination of mental health across diverse contexts, building upon and extending previous research in the field. We compare our findings with those from other studies across several key attributes, including empathy trends, gender differences, psychological impact of isolation, age-specific disorders, stress and coping challenges, and demographic insights. Many of these studies explore similar aspects of mental health, focusing on the influence of demographic and psychological factors across different populations.

Several studies emphasize different aspects of mental health analysis across distinct populations. For example, Verdonk et al. (2008) and Carrard et al. (2022) explore gender awareness and demographic influences specifically in medical student populations. In contrast, studies such as Arcand et al. (2023) and Brooks et al. (2020) focus on the psychological effects of stress and isolation in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, primarily within the general population. Hojat et al. (2023) and Baig et al. (2023) investigate empathy trends in clinical or educational settings. Meanwhile, Salk et al. (2017) analyze gender differences in depression across large-scale national samples, and McGrath et al. (2023), Park et al. (2021), and Udupa et al. (2023) examine age-specific disorders in clinical or broader population studies.

In contrast to these focused approaches, our study spans multiple dimensions of mental health across different populations, offering a comprehensive understanding of the connections between empathy, gender differences, isolation, age, stress, and demographic factors. This holistic approach provides a broader perspective on how mental health factors interact across various contexts. A comparative analysis of our study with existing research, highlighting the relative strengths and focuses across key attributes of mental health demographics, is presented in Table 15.

Limitations and future research directions

Our study presents several limitations. Due to its cross-sectional nature, we cannot draw causal conclusions from the observed associations, which is a common challenge in mental health research, as Kraemer et al. (2000) note. While multiple linear regression was used to analyze relationships between predictors and mental health outcomes in the “Medical student mental health” dataset, this approach may oversimplify the complexity of interactions between variables. Multivariate regression models could offer an alternative to account for multiple dependent variables simultaneously and evaluate interaction effects among demographic and contextual factors (Mennies et al. 2021). Future studies could incorporate multivariate methods to provide a more nuanced understanding of such relationships.

Although our datasets are diverse, they may not fully represent the general population. The inclusion of only three datasets limits the generalizability of our findings, particularly given their distinct contexts and populations. Expanding the analysis to additional datasets with varying cultural, geographic, and demographic profiles would enable more robust validation of the observed patterns and improve the external validity of the results. This limitation also highlights the need for future research to explore heterogeneity analyses across a broader range of datasets to evaluate the consistency of findings across diverse settings.

Additionally, our analysis relies on existing datasets based on self-reported measures, which may introduce biases such as recall or social desirability effects that could distort the accuracy of our conclusions. For example, our findings show that medical students become more empathetic over time, which contrasts with Hojat et al. (2023) and Bhatia et al. (2023), who report that empathy tends to decline during medical training. This discrepancy underscores the need for caution in interpreting self-reported data and suggests that objective measures, such as physiological or behavioral indicators, should supplement self-reported data in future studies.

Another limitation is the absence of a comprehensive exploration of cultural factors, even though Kirmayer emphasizes the importance of cultural considerations in mental health research (Kirmayer, 2012). While our study aimed to explore cross-dataset patterns, it did not account for potential cultural influences that could shape mental health outcomes. Future research should incorporate cultural dimensions and investigate how cultural norms and practices intersect with mental health outcomes in different populations.

Our findings highlight several areas for future research. Longitudinal studies are needed to track changes in mental health over time, particularly to understand the impact of educational and professional experiences on well-being. Additionally, future research should include more diverse populations, especially those often underrepresented in such studies. Expanding the datasets to include populations from underrepresented or underserved communities could address gaps in the current research.

The use of advanced technology, as suggested by Torous et al. (2019) and Sawyer et al. (2024), could improve data collection by offering more objective measures of mental health. For example, digital tools could capture real-time data, reducing biases inherent in self-reported measures. Finally, future research should investigate the intersectionality of factors such as race, gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status in influencing mental health outcomes, as Bowleg (2012) suggests.

Practical applications and interventions

Our findings offer significant real-world applications. In the context of medical education, the gender differences we observe in medical students’ empathy and mental health suggest the need for different approaches for men and women. This aligns with discussions by Rotenstein et al. (2016) and Hale et al. (Hale and Davis, 2023) on improving medical students’ mental health. Additionally, Verdonk et al. (2008) advocate for gender awareness in medical education, aligning with the principles of gender mainstreaming. This supports our observation that incorporating gender-specific interventions could enhance the training and well-being of medical students. The quarantine dataset highlights age-specific and gender-specific mental challenges, with middle-aged adults reporting higher stress levels. This finding emphasizes the importance of targeted support systems during crises, particularly for vulnerable groups. It also highlights the importance of a flexible mental health infrastructure that can quickly adapt to widespread challenges such as pandemics. In our analysis of the psychiatric disorder dataset, we observe a link between education levels and mental health outcomes. This suggests the protective role of education, reinforcing the idea that integrating mental health education across all levels of schooling could have long-term benefits.

However, implementing these insights comes with challenges. Traditional medical education and healthcare systems may resist change, making it difficult to introduce new approaches. There is also the concern that adopting gender-specific interventions might unintentionally reinforce stereotypes. Additionally, allocating resources for specific groups during a crisis can be a significant hurdle. Overcoming these barriers will require collaboration among policymakers, healthcare providers, educational institutions, and community organizations to ensure that these findings can be applied effectively.

In conclusion, our study contributes to a deeper understanding of the complexities of mental health, as outlined by Keyes (2005) in his work on mental health. By examining different groups and contexts, we show that mental health issues manifest in both similar and different ways depending on the situation. These insights could lead to more personalized treatments, aligning with Insel and Cuthbert’s approach through frameworks like RDoC, which emphasize context-specific mental health care advancements (Insel and Cuthbert, 2015).

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are publicly available from the following sources: • Identification of Major Psychiatric Disorders Dataset: https://osf.io/8bsvr/• Medical Students Mental Health Dataset: https://zenodo.org/records/5702895• Mental Health Depression During Quarantine Life Dataset: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/pxjmjyfdh2/1These datasets are openly accessible for research purposes, subject to the terms and conditions specified by their respective repositories.

Change history

05 August 2025

The Acknowledgements section was missing from this article and should have read: This work was conducted at and supported by the Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET), Dhaka, Bangladesh. The original article has been corrected.

References

Ahmed A, Agus M, Alzubaidi M, Aziz S, Abd-Alrazaq A, Giannicchi A, Househ M (2022) Overview of the role of big data in mental health: a scoping review. Comput Methods Prog Biomed Update 2:100076

Alon-Tirosh M, Hadar-Shoval D, Asraf K, Tannous-Haddad L, Tzischinsky O (2021) The association between lifestyle changes and psychological distress during covid-19 lockdown: the moderating role of covid-related stressors. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18:9695

Amin N, Salehin I, Baten MA, Al Noman R (2024) Rhmcd-20 dataset: identify rapid human mental health depression during quarantine life using machine learning. Data Brief 54:110376

Araya R, Lewis G, Rojas G, Fritsch R (2003) Education and income: which is more important for mental health? J Epidemiol Community Health 57:501–505

Arcand M, Bilodeau-Houle A, Juster R-P, Marin M-F (2023) Sex and gender role differences on stress, depression, and anxiety symptoms in response to the covid-19 pandemic over time. Front Psychol 14:1166154

Avendano M., de Coulon A, Nafilyan V (2017) Does more education always improve mental health? Evidence from a British compulsory schooling reform. Health, Econometrics and Data Group (HEDG) Working Papers 17/10, HEDG, c/o Department of Economics, University of York

Baig KS, Hayat MK, Khan MAA, Humayun U, Ahmad Z, Khan MA (2023) Empathy levels in medical students: a single center study. Cureus 15(5):e38487. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.38487

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y (1995) Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc: Ser B (Methodol) 57:289–300

Berking M, Wupperman P (2012) Emotion regulation and mental health: recent findings, current challenges, and future directionsCurr Opin Psychiatry 25:128–134

Bhatia G, Shetty JV (2023) Trends of change in empathy among indian medical students: a two-year follow-up study. Indian J Psychol Med 45:162–167

Bowleg L (2012) The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality—an important theoretical framework for public health. Am J Public Health 102:1267–1273

Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, Rubin GJ (2020) The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet 395:912–920

Carrard V, Bourquin C, Berney S, Schlegel K, Gaume J, Bart P-A, Preisig M, Schmid Mast M, Berney A (2022) The relationship between medical students’ empathy, mental health, and burnout: a cross-sectional study. Med Teach 44:1392–1399

Charles ST, Carstensen LL (2010) Social and emotional aging. Annu Rev Psychol 61:383–409

Cicchetti D, Toth SL (2009) The past achievements and future promises of developmental psychopathology: the coming of age of a discipline. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 50:16–25

Cutler DM, Lleras-Muney A (2006) Education and health: evaluating theories and evidence. Working paper series 12352 (1). National Bureau of Economic Research

Damiano RF, de Andrade Ribeiro LM, Dos Santos AG, Da Silva BA, Lucchetti G (2017) Empathy is associated with meaning of life and mental health treatment but not religiosity among brazilian medical students. J Relig health 56:1003–1017

De Maio Nascimento M, da Silva Neto HR, de Fátima Carreira Moreira Padovez R, Neves VR (2023) Impacts of social isolation on the physical and mental health of older adults during quarantine: a systematic review. Clin Gerontol 46:648–668

Drew N, Funk M (2010) Mental health and development: targeting people with mental health conditions as a vulnerable group. World Health Organization