Abstract

This study investigates the impact of advanced digital technologies, particularly virtual reality (VR), on the sustainability of cultural heritage tourism, focusing on user reuse behavior. Amid the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, traditional tourism has gravitated toward immersive technologies to enhance economic, social, and environmental sustainability. Utilizing the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) model, this research examines how existential authenticity and immersion influence cultural attachment, satisfaction, and subsequently, intent to reuse and social sustainability. The methodology employs the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) to analyze user data. The results indicated that while existential authenticity significantly affects cultural attachment and satisfaction, immersion does not directly impact satisfaction, contradicting previous research. Cultural attachment emerges as a pivotal variable, influencing satisfaction, intention to reuse, and social sustainability, underscoring its critical role in enhancing user experiences in virtual exhibitions. The study recommends that VR experiences be designed to evoke existential authenticity to improve cultural attachment and user satisfaction, which are essential for advancing social sustainability. This research contributes empirical evidence to the role of immersive technologies in fostering social sustainability within cultural heritage tourism and offers practical insights for stakeholders in the sector.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Advanced digital technologies accelerate business development (Ardolino et al. 2018). Suh and Prophet (2018) reported that immersive technologies, such as virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR), have become increasingly important for innovative marketing strategies across various sectors, and the utilization of innovative technologies in the tourism industry is seen as a natural step towards seeking breakthroughs (Fan et al. 2022). The usage of immersive technologies in tourism are regarded as a practical approach for sustainable development (Buhalis et al. 2023), and tourism corporations actively participate in constructing digital development to promote tourism competitiveness and performance due to the recession in the last several years caused by COVID-19 (Lu et al. 2022), with the express intentions of improving destination revenue by virtual tourism (Manchanda and Deb 2021), indicating improved economic sustainability (Jiang and Phoong 2023). It was also found that an increasing number of travelers are concerned about the potential benefits of immersive tourism products, which can eliminate environmental damage caused by on-site tourism and maintain sustainability. Talwar et al. (2022) pointed out that virtual tourism is a unique experience that can stimulate tourists’ actual behavior for better satisfaction and is an active opportunity for environmental sustainability (Scurati et al. 2021). In the COVID-19 era defined by traveling restrictions, virtual tourism can be a viable alternative for fulfilling economic, social, and environmental sustainability (El-Said and Aziz 2021). Zhang et al. (2022) reported that museums using virtual technologies received positive emotional feedback from tourists during COVID-19. Some museums are utilizing AR to promote cultural information and enhancing experience marketing (Zhu and Wang 2022). Additionally, from the perspective of customer behavior research, immersive technologies can increase visitor perception (Han et al. 2019), strengthen the sense of authenticity (Atzeni et al. 2022a), and promote the satisfaction of the experience (Trunfio et al. 2018; Trunfio et al. 2022), alongside promoting social sustainability. One of the advantages of cultural heritage tourism is that it improves understanding and appreciation of culture, offering people social welfare, which is one of the criteria for social sustainability (Vallance et al. 2011). Researchers seek to enhance tourists’ satisfaction with sustainable practices using new technologies (Talwar et al. 2022). Although there is some research on the relationship between immersive technologies and environmental and economic sustainability, the lack of concern for social sustainability makes it necessary to explore the function of the promotion of immersive technologies for social sustainability in a cultural heritage context (Jiang and Phoong 2023).

It is important to define authenticity within the context of cultural heritage tourism due to the applied theoretical dimensions in this research. Authenticity is a complex construct with multiple dimensions, encompassing objective, constructive, and existential authenticity. Objective authenticity relates to the representation’s factual accuracy and historical correctness, while constructive authenticity centers on interpreting and presenting a site or experience to create a sense of genuineness. As a trigger, existential authenticity focuses on visitors’ subjective emotional responses and personal feelings (Gao et al. 2022).

This research prioritizes existential authenticity due to its relevance to emotional engagement and the personal connection crucial for fostering cultural attachment, a key element of social sustainability within cultural heritage tourism (Brown 2013; Rickly-Boyd 2013). Unlike objective or constructive authenticity, existential authenticity does not depend solely on factual accuracy or curated presentations but on individual visitor experiences and the extent to which these experiences evoke meaningful emotions and a sense of connection to the heritage. This feeling of authenticity is critical for promoting cultural attachment and social sustainability.

Immersion is another critical variable in this study. Often viewed as a subjective experience (Pine and Gilmore 2011), immersion represents the degree to which users feel engaged in a virtual environment. This engagement extends beyond visual immersion to sensory, emotional, and cognitive involvement (Hansen and Mossberg 2013). Within virtual cultural heritage tourism, immersion significantly influences user experiences and their link to the heritage (Chang and Chiang 2022). Higher levels of immersion foster stronger emotions and deeper engagement, molding user attitudes, perceptions, and behaviors.

By focusing on existential authenticity and immersion, this study offers a comprehensive approach to investigating the influence of technology-mediated experiences on visitor behavior in cultural heritage tourism. This study examines the effects of these constructs on cultural attachment and satisfaction, both critical determinants of positive user engagement and social sustainability within the tourism sector.

It has been reported that the existing digital communication tool, WeChat applets in China, offer tourists an integrated experience with immersive technology, such as Cloud Tour the Palace and Cloud Tour Dunhuang applications developed by the Palace Museum and the Dunhuang Academy (Li and Xiao 2021; Song 2023). Moreover, in the study of antecedents as well as processes of virtual cultural heritage tourism experience, apart from the widely researched interactivity, immersion, and presence as important influencing factors (Blumenthal and Gjerald 2022), authenticity (Çiftçi and Çizel 2024), and cultural attachment (Genc and Gulertekin Genc 2023) are considered important variables affecting tourists’ experiential satisfaction and behavior. In the context of immersive applications, the relationship between these factors seems subtly altered compared to the everyday virtual viewing context. While there has been extensive research on the effects of virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) on consumer perception processes (Wei 2019), few studies have explored the role of authenticity, immersion, and cultural attachment in the experience of cultural heritage-related immersion applications. Thus, this study addresses its objectives in the context of the above by proposing the following three research questions:

RQ (1). What is the impact of stimuli (existential authenticity and immersion) on organisms (cultural attachment and satisfaction)?

RQ (2). What is the relationship between organism (cultural attachment, satisfaction), and response (intention to reuse and social sustainability)?

RQ (3). What is the social sustainability impact of the intention to reuse immersive technology used in applets?

This study aims to close the abovementioned research gaps and address the research questions by investigating the impact of stimuli for experiencing immersive virtual application use on the organism based on the SOR model, thus influencing the final behavioral outcomes. Also, this article focuses on the impacts of immersive applications for cultural heritage on social sustainability and aims to provide theoretical and empirical guidance to stakeholders of cultural heritage tourism interested in improving cultural heritage sustainability.

Literature review and hypotheses development

Immersive application in the tourism industry

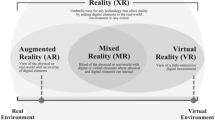

Immersive technology is present across various sectors, mainly businesses (Liberatore and Wagner 2021), marketing (Adachi et al. 2020; Alcañiz et al. 2019; Alfaro et al. 2019; Buhalis et al. 2023), education (Klippel et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2020), and medicine (Ahuja et al. 2023; Pears et al. 2020). The literature summarizes how immersive technologies are used in tourism (Beck et al. 2019; Ercan 2020; Fan et al. 2022; Hincapie et al. 2023; Loureiro et al. 2020; Pratisto et al. 2022; Wei 2019). Previous research stipulates that immersive technologies, such as virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and mixed reality (MR)—are considered key components of advanced technologies (Handa et al. 2012). Carmigniani et al. (2011) stated that AR uses information technology to add images or audio elements to the existing world, while Perry Hobson and Williams (1995) implied that VR creates an environment that makes people think they are actually in it. Immersive technologies became a component of tourism research, with the studies evolving from exploring the perception process of its user experience to marketing (Yung et al. 2021), education (Shen et al. 2022), cultural heritage conservation (Trunfio et al. 2022), and sustainability (Talwar et al. 2022). The impact of VR and AR applications has been widely covered in previous studies (Pratisto et al. 2022). Fan et al. (2022) analyzed the drivers of immersive technology usage, showing that despite the popularity of immersive technology, it does not offer enough of an experience to be a natural alternative to tourism, due to the various levels of acceptance and engagement by the people involved. Furthermore, the utilization of immersive technology in the tourism industry can have a double-edged effect; overly immersive experiences may generate unrealistic expectations, potentially resulting in heightened disappointment during actual visits (Collin-Lachaud and Passebois 2008; Prandi et al. 2023).

Previous studies focused more on the usage acceptance by tourists, such as ease of use, usefulness, and commercial practices (El-Said and Aziz 2021). Bogicevic et al. (2019) indicated that empirical studies of virtual tourism are limited; therefore, studies are now gradually paying attention to the continued willingness to use (Cheng and Huang 2022; Kim et al. 2023), intention to re-use (Anand et al. 2022; Daassi and Debbabi 2021), immersive process (Blumenthal and Gjerald 2022), and various other factors that influence the perception process (Trunfio et al. 2022).

Immersive technology and museum tourism: social sustainability

Immersive technologies are frequently used in practice and the development of tourism research. Previous research hotspots have been digital construction and tourism development (Zsarnoczky 2018), however, the irreversible damage to the tourism industry caused by COVID-19 (Kwok and Koh 2021) represents a breakthrough for virtual technology, given the need for sustainable development in the tourism industry (Lu et al. 2022). Previous research has not shown that immersive technology in the tourism industry is a net positive, while current research shows that the impact of the appropriate use of immersive technology is mostly positive vis-à-vis sustainability (Scurati et al. 2021; Yang et al. 2022).

Sustainable tourism combines economic, environmental, and social aspects (Higgins-Desbiolles 2018). Go and Kang (2023) believed that sustainable progress in tourism cannot be realized without the development of immersive technologies. Choi and Kim (2021) present VR exhibitions as a new way of being stimulated during COVID-19, relieving the pressure on museums to be sustainable. Moreover, virtual tourism applications have value for future sustainable development of the tourism industry when overcoming challenges (Putra et al. 2021). Loach et al. (2017) pointed out that museums’ digital development significantly contributes to social and cultural sustainability. Social sustainability generally includes social equity and participation, cultural preservation, and social well-being (Vallance et al. 2011). Caciora et al. (2021) regarded that using VR in heritage can effectively raise awareness of conservation among visitors from a social perspective.

The International Council of Museums (ICOM) defines a museum as a permanent non-profit institution serving society by researching, collecting, conserving, interpreting, and displaying tangible and intangible heritage (Tatlı et al. 2023). Therefore, museums, as public infrastructures integrating the functions of cultural heritage, leisure and entertainment, and social services, are closely linked to SDGs, and are one of the most important organizations to promote sustainable development (McGhie 2020). As museums are historical and cultural carriers, as educational and cultural institutions, they play an increasingly important role in defining the connotation of sustainable development and promoting social sustainable development (Pop et al. 2019). Reflecting on how museums can better fulfill their social service functions in the current environment needs to be emphasized. Cultural heritage exhibitions embodied in museums are committed to social sustainable development to inherit and develop distinguished cultures, raising awareness of cultural preservation, and enabling more visitors to be educated and actively participate in the dissemination of cultures, as well as to be able to receive equalized social benefits and gain a sense of well-being from them (Ahmed et al. 2020; Hansson and Öhman 2022).

Previous studies explored the impacts of the direct and/or indirect relationship between VR and environmental sustainability (Su et al. 2024). However, more empirical evidence is required for studies exploring the relationship between the use of virtual technologies in museums and social sustainability. Therefore, this study broadens the scope of the research from tourism experiences to social sustainability to investigate the topic of more comprehensive immersive technologies in tourism research.

Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) model

Before exploring the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) model, it is important to contextualize this study within a broader context of theoretical frameworks that help explain user behavior in immersive environments. Various models, such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT), have historically informed our understanding of technology acceptance and usage. However, the S-O-R model is especially relevant to this research, as it effectively captures the intricate psychological processes within immersive virtual experiences. This model is suitable for examining the nuanced complexities of cultural heritage tourism, allowing for a deeper exploration of how various stimuli influence user experiences.

The Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) model, which originated in the domain of environmental psychology, postulates that diverse elements of the external environment function as stimuli (S), which subsequently influence the behavioral responses (R) of individuals by affecting their internal states (O) (Mehrabian and Russell 1974). Generally, the stimulus (S) represents the external environmental stimuli encountered by an individual at a particular time that tends to induce internal mental processes known as organisms (O), thereby triggering a behavioral response (R), which is an explanation as a sequential mechanism and also the process by which the behavior occurs (Jacoby 2002).

The SOR model provides a suitable basis for our conceptualization in this study. First, the literature shows that the theory has been used in different domains to explain the behavioral processes of users (Asyraff et al. 2023; Chin et al. 2023). The SOR model is often employed as a theoretical foundation in explorations of virtual tourism behavior (Kim et al. 2020). Talwar et al. (2022) explained the factors motivating consumers to visit VR-presented destinations based on the SOR. Li et al. (2024) demonstrated that the interactivity of the VR travel e-commerce platform’s display stimulates interactive pleasure, positively influencing impulse purchase intentions based on SOR. Second, Talwar et al. (2022) argued that due to the complexity of consumers’ psychological processes and the flexibility of the SOR model, different perspectives can be approached to detect psychological complications and the ability to be flexibly extended in different contexts to present a broader dimension of what is being studied.

This study identified the stimulus (S) as existential authenticity based on the literature, which is a state of being rather than objective reality, primarily stimulating the emergence of emotions, sensations, and perceptual relationships (Brown 2013; Rickly-Boyd 2013). Although existential authenticity involves subjective internal feelings, it can be seen as an external stimulus when framed through the lens of how cultural representations are presented in VR. For instance, a VR experience that accurately recreates historical or cultural sites or authentically portrays cultural narratives serves as a stimulus that evokes emotional responses in users. Also, immersion is a significant factor that promotes psychological changes in further VR experiences, serving as the stimulus (S) in this study (Park et al. 2022). Immersion is a significant external stimulus, transforming how users perceive and interact with VR environments. Second, in terms of the organism (O), cultural attachment is considered a standard emotional link that tourists have with culture, which is easily stimulated by external factors and serves as an intermediary variable affecting behavior. Cheng and Chen (2022) posited that cultural attachment can effectively bridge decision-making. This study reiterates the role of user satisfaction as the organism (O) (Chen et al. 2022; Zhu et al. 2020). Finally, in terms of the conceptualization of response (R), the intention to reuse is a typical tourist behavior (Yu et al. 2024), reflecting the outcomes of this study. In order to address one of the research questions on the impact of VR technology on social sustainability, this study conceptualizes social sustainability as an outcome of tourists’ cognition, consistent with previous research, where the assessment of sustainability stems from the internal states triggered by attitudes towards the use of VR tourism (Phaosathianphan and Leelasantitham 2021; Talwar et al. 2022). Since VR is positioned as a more sustainable form of tourism, tourists’ evaluation of its sustainability has been validated (Helgadóttir et al. 2019; López et al. 2018; O’Connor and Assaker 2022).

By synthesizing insights from the literature, the following research hypotheses emerge from the S-O-R framework, emphasizing the sequential relationships among the constructs of existential authenticity, immersion, cultural attachment, satisfaction, intention to reuse, and social sustainability:

-

H1a: Existential authenticity has a positive effect on immersion.

-

H1b: Existential authenticity has a positive effect on satisfaction.

-

H1c: Existential authenticity has a positive effect on cultural attachment.

-

H2a: Immersion has a positive effect on cultural attachment.

-

H2b: Immersion has a positive effect on satisfaction.

-

H3a: Cultural attachment has a positive effect on satisfaction.

-

H3b: Cultural attachment has a positive effect on intention to reuse.

-

H3c: Cultural attachment has a positive effect on social sustainability.

-

H4a: Satisfaction has a positive effect on intention to reuse.

-

H4b: Satisfaction has a positive effect on social sustainability.

-

H5: Intention to reuse has a positive impact on social sustainability.

The research hypotheses proposed in this study are explained using the SOR model, exploring the impact of existential authenticity and immersion on cultural attachment and satisfaction via sequential mechanisms, and subsequently assessing the impact on the intention to reuse and social sustainability. It can be seen that the arguments connecting these relationships lack sufficient depth; therefore, detailed explanations, supported by relevant literature or theoretical frameworks, would enhance the credibility and clarity of the proposed hypotheses. The research model of this study is shown in Fig. 1.

Existential authenticity and immersion

Authenticity is defined as “the enjoyment and perception of the authenticity of the experience by tourists, and is divided into existential, constructive, and objective authenticity” (Wang 1999). Authenticity can be considered a factor in virtual domains (Peng and Ke 2015). Existential authenticity refers to individuals’ sense of genuineness when engaging with experiences that resonate deeply with their values, beliefs, and identity, and in the context of cultural heritage tourism, it relates to how well an experience reflects the authentic essence of a culture (Kim and Lee 2022). It can also refer to the subjective feelings and existential state of the tourists’ experience (Steiner and Reisinger 2006; Gao et al. 2022). Generally, in a virtual environment, the higher the fidelity of VR technology, the stronger the sense of authenticity it produces in tourists (Li et al. 2024), making it easier for tourists to immerse themselves in virtual scenes (Dağ et al. 2023). Although there are studies on authenticity and immersion, the impact of existential authenticity on immersion is scarce (Mou et al. 2024). The literature reported a positive relationship between perceived authenticity and satisfaction (Park et al. 2019). Nam et al. (2022) indicated that authenticity in the context of VR heritage tourism positively impacts satisfaction; however, more research is required to assess the influence of existential authenticity on satisfaction in virtual cultural heritage tourism. Atzeni et al. (2022) reported that existential authenticity positively affects tourists’ cognitive and emotional responses. A positive relationship exists between existential authenticity and attachment to VR destinations (Arya et al. 2019; Kim and Lee 2022). However, more evidence is required to demonstrate how existential authenticity in VR affects cultural attachment in heritage tourism. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H1a: Existential authenticity has a positive effect on immersion.

H1b: Existential authenticity has a positive effect on satisfaction.

H1c: Existential authenticity has a positive effect on cultural attachment.

Immersion is considered a subjective experience when placed in real or virtual environments (Pine and Gilmore 2011). It is defined as a sense of spatial and temporal belonging that deeply integrates into the present (Hansen and Mossberg 2013). In the literature, the concept of immersion can be an objective description of the system’s immersion properties and a subjective perception of immersion by the user (Visch et al. 2010). Therefore, as a typical characteristic of VR environments, immersion is often referred to in VR tourism research as the user’s perception of an immersive experience in a VR environment (Bafadhal and Hendrawan 2019).

In the entertainment context, immersion has been extensively studied and identified as a core feature that stimulates the respondents to feel embodied in virtual worlds and return to engage with the content (Haywood and Cairns 2005). Several studies focused on how VR is experienced at different stages of tourism, with an emphasis on the role of presence (Tom Dieck et al. 2024), immersion (Cadet and Chainay 2020), and interaction (Yang et al. 2023). There has also been a growing number of recent studies exploring the relationship between VR and pro-environmental behaviors, suggesting that research on VR in the tourism industry is gaining traction (Kim et al. 2020). Since immersion is an important factor in the VR experience, it often leads to further psychological changes in users using VR (Hudson et al. 2019; Mou et al. 2024).

Features such as 360-degree views, interactive elements, and realistic audio-visual feedback are aspects of the VR technology that create this immersive experience (Park et al. 2022). For example, attachment is the intimate connection and psychological feeling of tourists towards something or a place; the enhanced immersion of virtual tourism technology also helps tourists’ participation in cultural heritage and even attachment to heritage destinations (Chang and Chiang 2022).

Moreover, in cultural heritage tourism, the manifestation of tourists’ cultural attachment represents the emotional connection from a cultural perspective. However, previous work has not analyzed the impact of immersion on cultural attachment in the VR environment. Also, previous research has shown that promoting immersion in the virtual world can significantly enhance tourists’ satisfaction (Melo et al. 2022), illustrating the importance of immersion in virtual tourism experiences (Kyrlitsias et al. 2020). However, empirical data about using VR technology in cultural heritage tourism is scarce. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H2a: Immersion has a positive effect on cultural attachment.

H2b: Immersion has a positive effect on satisfaction.

Cultural attachment and satisfaction

Cultural attachment is similar to the classic concept of attachment. It is considered to be the individual’s ability to receive supportive responses from their culture when needed, and to build confidence to explore new cultural environments, thereby developing cultural attachment (Hong et al. 2013). Cultural attachment represents a unique type of attachment, which captures explicitly the emotional connection between the individual and their cultural group (Liu et al. 2023). Routh and Burgoyne (1998) believed that cultural attachment can be a pride in national, cultural, and historical symbols, such as the national flag, language, historical origins, and currency. In the context of cultural heritage, the cultural pride and emotional connection generated towards heritage can be considered a form of cultural attachment. The literature indicated that attachment is one of the important factors in predicting tourist satisfaction (Xu Ning-Ning et al. 2022), and attachment to cultural communities significantly impacts the intention to revisit (Lee et al. 2014; Zhou and Pu 2022). Cultural attachment has an important impact on responsible environmental behavior, thereby enhancing sustainable tourism (Cheng and Chen 2022), and cultural participation and satisfaction are indicators of social sustainability (Buonincontri et al. 2017), while cultural attachment reflects inner participation and emotional connection to culture. In the context of cultural heritage tourism, whether or not the cultural attachment of tourists experiencing cultural heritage through VR technology impacts satisfaction, re-use intentions, and social sustainability requires further exploration. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H3a: Cultural attachment has a positive effect on satisfaction.

H3b: Cultural attachment has a positive effect on intention to reuse.

H3c: Cultural attachment has a positive effect on social sustainability.

Tourist satisfaction is the post-consumption evaluation of consumers after obtaining a particular product or service (Gundersen et al. 1996). Generally, Rust and Oliver (1993) believed that whether a person believes a product or service provides good utility depends on satisfaction; thus, satisfaction is regarded as a subjective feeling and experience to detect user behavior (Cole and Illum 2006). Moreover, innovative applications can increase client satisfaction, leading to higher reuse (Kim et al. 2020). Previous research has identified satisfaction as a substantial contributor to continuous intention (Han and Yang 2018) or continuance behaviors (Tom Dieck et al. 2024). Utilizing virtual technology in museums improves visitor experience and satisfaction, which in turn enhances the use of technology (Alam et al. 2024; Trunfio et al. 2022). Also, previous research confirmed a positive relationship between sustainability and satisfaction (Marín-García et al. 2022), and satisfaction can be regarded as one of the important assessment factors for college students’ social sustainability (Bikar Singh et al. 2022). Moreover, life satisfaction supports sustainable tourism development (Eslami et al. 2019). Tourist satisfaction with VR tourism implies the development of social sustainability (Akhtar et al. 2021; Talwar et al. 2022), as VR tourism is increasingly recognized as a means to support sustainability (El-Said and Aziz 2021). Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H4a: Satisfaction has a positive effect on intention to reuse.

H4b: Satisfaction has a positive effect on social sustainability.

Intention to re-use and social sustainability

Previous research confirmed that adopting virtual technology in tourism is used for various purposes and helps promote sustainable tourism development (Lu et al. 2022). There is an essential connection that using smart tourism technologies positively impacts sustainability (Phaosathianphan and Leelasantitham 2021). From a marketing perspective, virtual environment visits may be a potential tool for sustainable development (Go and Kang 2023). However, most research on the relationship between the use of VR technology and sustainability focuses on environmental sustainability, lacking more testing and empirical confirmation of social sustainability (Woosnam and Ribeiro 2023). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed in this study:

H5: Intention to reuse has a positive impact on social sustainability.

Methodology

The Cloud Tour Dunhuang applet was selected for this research, as its supporting institution is the Dunhuang Academy, a well-known first-class museum in China, containing world-class cultural heritage destinations such as the Mogao Grottoes. This selection was made due to its visibility, information exposure, and cultural attractiveness advantages.

Background of study

The Mogao grottoes in Dunhuang, China, are the crystallization of ancient civilization exchanges, possessing rich historical, artistic, technological, and social values. The Dunhuang Academy, in conjunction with China’s People’s Daily New Media and Tencent, launched the first WeChat app with a rich Dunhuang grotto art appreciation experience in 2020, called “Cloud Tour Dunhuang”. The applet uses virtual digital technology to reproduce the contents of the Dunhuang grottoes virtually and even integrates functions such as ticket reservation and traditional culture courses. Users can enter the virtual reproduction of the grottoes through the platform to understand the content of the mural paintings and learn the stories of the mural paintings, thus contributing to the protection of the cultural relics of Dunhuang and promoting the sustainable development of cultural heritage. This study focuses on the VR in-depth online roaming of Seeking Dunhuang in the cloud tour of Dunhuang, i.e., the Digital Dunhuang Immersion Exhibition, Cave 285 of Mogao Grottoes.

Measures

This research seeks to evaluate the user experience of the Cloud Tour Dunhuang application and its implications towards enhancing social sustainability within cultural heritage tourism. A key component of this evaluation lies in measuring various psychological constructs that influence the user experience. The variables and indicators included in this study have been primarily adapted from the literature. However, significant efforts have been expended to refine these measures per this research’s specific themes and objectives, ensuring they are relevant and applicable to the unique context of the examined virtual environment.

The scales were subjected to rigorous scrutiny and adaptation based on previous works to enhance the robustness and credibility of the measurements. Each construct was carefully selected and adapted to reflect the nuances of user interactions with the Cloud Tour Dunhuang application. This process highlights the authors’ contribution to the field by providing a validated framework for understanding the factors contributing to compelling immersive experiences, paving the way for future research endeavors.

All measurements were assessed using a five-point Likert scale, where 1 indicates strong disagreement and 5 indicates strong agreement with each statement (Table 1). This scale allows for nuanced responses, facilitating a better understanding of the varying degrees of user perception and experience. The questionnaire includes five demographic questions focusing on age, gender, education, occupation, and income. The demographic data will provide essential insights into the diversity of the sample and allow for analysis of how demographic factors influence the variables being studied.

Sampling and data collection

A survey was conducted from February to May 2024 for data collection. The target population consisted of Chinese individuals who possess WeChat but have not used the “Cloud Tour Dunhuang”. Only respondents unfamiliar with the Cloud Tour Dunhuang experience were eligible to participate to ensure that participants approached the questionnaire with a fresh perspective. A purposive sampling method was employed in this study. The quantitative approach was adopted, with the primary mode of data collection being an online questionnaire. A total of 409 valid responses were compiled for analysis after excluding 12 deemed unusable. Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) analysis typically suggests a sample size of at least 200 respondents for robust results (Hair et al. 2009). This substantial sample size enhances the reliability of the statistical analyses conducted in this study.

First, the proposed content and objectives of this research were introduced on the cover page of the questionnaire to emphasize the importance of confidentiality. The first question of the questionnaire distinguished and clarified the objectives of this study, and asked whether or not the participants had used and browsed the Cloud Tour Dunhuang’s Seeking Dunhuang Virtual Reality Online Exhibition, if the answer is yes, then the participants are asked to stop answering the questionnaire, if the answer is no, they can continue to the next section, which is a link to the Cloud Tour Dunhuang. This gives the respondent enough time to use and experience the Cloud Tour Dunhuang application before completing the questionnaire. The online survey is completed immediately, minimizing time bias and cognitive dissonance (Wattanacharoensil and La-ornual 2019). The participants were informed of the confidentiality of the survey, and the data collected was used exclusively for academic research and analysis. The visit was conducted using low-immersive VR, where virtual content was displayed on a device such as a mobile device or laptop (Pleyers and Poncin 2020). Therefore, the survey requires that respondents be allowed to experience this application, with no time limitation. However, based on the survey’s indication, the average time is about 5 min per person.

The questionnaire was then divided into two parts, the first being demographic characteristics and the second being 23 indicators consisting of 6 different constructs related to the structure of the study.

Analysis method

This study employs Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) to construct and validate a theoretical framework. SEM is a widely used statistical technique that excels at analyzing complex causal relationships between variables by combining factor loading analysis with multiple regression analysis. It is particularly effective for assessing the interactions of multiple variables, making it ideal for theory construction and validation (Ringle and Sarstedt 2016). As a PLS-SEM, SmartPLS simplifies the specification of relationships and modeling complexity by making relationships between variables and indicators explicit through path models (Hair et al. 2017). This study used SmartPLS version 4.0, and the partial least squares structural equation modeling was employed. In previous studies, empirical research on tourism frequently used PLS-SEM as a data analysis methodology since the technique is suitable for research programs that validate statistical models containing direct and indirect interrelationships by assessing multi-item variables. Therefore, utilizing PLS-SEM analysis is suitable for this study.

Findings

Respondents’ profile

As shown in Table 2, the gender distribution of the participants showed that 57.9% are male and 42.1% are female. The age distribution ranged between 18 and 60 years old, with participants in the 26–30 age group dominating at 42%. Regarding educational background, most participants had a bachelor’s degree at 71.7%, followed by college at 10.5%. Occupational backgrounds are diverse, encompassing students, corporate employees, government and agency employees, self-employed, and retirees, with corporate employees accounting for the highest percentage at 39.2%. Monthly incomes are widely distributed, ranging from less than 3000 RMB to more than 15,000 RMB, with 5000–8000 RMB accounting for 25.4%.

Common method bias

In Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), assessing common method bias is an important step in ensuring the validity of the results. The variance inflation factor (VIF) is commonly used to evaluate multicollinearity among constructs and indicates common method bias. While the standard threshold for VIF values is a maximum of 5 (Hair et al. 2009), more stringent criteria suggest that VIF values remain below 3.3 to indicate the absence of common method bias (Hair et al. 2011; Kock 2017).

In this study, VIF values were carefully analyzed to ensure robustness. As presented in Table 3, all VIF values were below the critical threshold of 3.3, suggesting that common method bias is absent in the collected data.

While the use of VIF is a valid approach, it should be pointed out that other methods, such as Harman’s single-factor test or Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), are also widely used for assessing common method bias. Harman’s single-factor test evaluates whether a single factor accounts for a substantial portion of the covariance among the items, while CFA can provide insights into the fit of the measurement model.

Future research could consider employing these alternative methods alongside VIF to enhance analytical rigor. However, in this study, the decision to use VIF was based on its established applicability in the context of PLS-SEM, and the results indicate low multicollinearity, effectively supporting the absence of common method bias.

Measurement model test

In this study, the assessment of common method bias was initially conducted using outer variance inflation factor (VIF) values. While outer VIF values can provide insights into multicollinearity, utilizing inner VIF values from SMARTPLS for reflective measurement models is recommended. Inner VIF values assess the relationships between constructs in the structural model, aligning more appropriately with the reflective nature of the scales employed. In research, including outer and inner VIF analyses to comprehensively evaluate common method bias and multicollinearity would be beneficial.

As shown in Table 3, while outer VIF values were assessed and all values were within acceptable thresholds, including inner VIF values strengthens the analysis further and ensures alignment with recommended practices in PLS-SEM. This dual approach can enhance the robustness of the model evaluation by thoroughly examining potential multicollinearity across the model’s measurement and structural components.

The normality test is an important test for identifying data distribution. Further analysis can only be performed if it has the criteria of conformity to normality; generally, the absolute value of kurtosis is less than 10 and the absolute value of skewness is less than 3, which implies that there is no serious violation of the normal distribution (Kline 2019). Table 3 shows that the requirement of normality is satisfied.

The value of Cronbach’s Alpha is measured to examine the internal consistency and reliability. According to (Hair et al. 2011), values of less than 0.7 are unacceptable, while values greater than 0.8 are preferred. The value of Cronbach’s Alpha in this study ranges from 0.741 to 0.913, indicating that all items are within the acceptable range. Composite reliability (CR) is used to detect internal consistency, and the CR of this study is 0.836–0.935, which meets the CR criterion of greater than 0.7; therefore, this study’s results indicate reliability, per Table 3.

Factor loadings are used to estimate the convergent validity. Hair et al. (2017) argued that the factor loadings should not be lower than the recommended minimum of 0.7. The factor loadings of all items in this study ranged from 0.714 to 0.924, which were all higher than 0.7, implying that the factor loadings of the items were all acceptable. The average variance extracted (AVE) is another way to explore the convergent validity; if the AVE value is greater than 0.5, the latent variable has a high convergent validity. The AVE in this study ranges from 0.562 to 0.782, indicating that the measurement model has good convergent validity, per Table 3.

To confirm discriminant validity, this study required the square root of the AVE for each construct to exceed the corresponding correlation coefficient with the other constructs (Fornell and Larcker 1981). The Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio of Correlations (HTMT) analysis showed excellent discriminant validity in this study, indicating that each variable was discriminatory compared to the others. All HTMT values were below 0.85, which is in line with the required HTMT (<0.85), indicating good distinctiveness between the constructs (Tables 4 and 5). Thus, the measurement model showed satisfactory reliability as well as discriminant validity.

Structural model test

After validating and determining the confidence of the measurement model, the next step involves the evaluation of the structural model, including examining the relationships between paths. Among them, R2 is 0–1, reflecting the model’s explanatory power. Q2 predicts its relevance. When Q2 > 0, it indicates that the structural model has predictive relevance to the endogenous constructs. When Q2 < 0, it indicates that the structural model does not have predictive relevance to the endogenous constructs in Table 6.

According to Table 7, a path coefficient test was conducted on 5000 subsamples; Existential authenticity had a positive effect on Immersion (β = 0.161, p < 0.01**), Cultural attachment (β = 0.373, p < 0.001***), and Satisfaction (β = 0.307, p < 0.001***). Therefore, H1a, H1b and H1c are supported. Immersion has a positive effect on Cultural attachment (β = 0.139, p < 0.001***) and is accepted for H2a; however, it is not supported for H2b, which means there is no positive effect on Satisfaction (0.069, p = 0.123). Cultural attachment has a significant effect on Satisfaction (β = 0.318, p < 0.001***), Intention to reuse (β = 0.352, p < 0.001***), and Social sustainability (β = 0.325, p < 0.001**). **) has a significant effect, implying that H3a, H3b, H3c are all supported. Furthermore, Satisfaction has a positive effect on Intention to reuse (β = 0.351, p < 0.001***) and Social sustainability (β = 0.272, p < 0.001***), implying that H4a and H4b are accepted. In addition, the Intention to reuse (β = 0.189, p < 0.001***) positively affects Social sustainability, and H5 is accepted.

Discussion and conclusion

Discussion

This discussion evaluates the results and explores their broader implications for immersive cultural tourism due to the lack of synthesizing VR tourism technology and social sustainability in contemporary research. This study focuses on the process of using and experiencing the VR online exhibition of the Cloud Tour Dunhuang applet and the impact on social sustainability based on the SOR theory and introduces an integrated model to assess the relationship between the existential authenticity, immersion, cultural attachment, satisfaction, intention to reuse, and social sustainability. The findings of this study address the research questions posed, providing empirical evidence within a previously unexplored context.

First, RO1 was addressed, and the positive effect of existential authenticity on immersion, cultural attachment, and satisfaction reveals the importance of the subjective perception of authenticity within the user in virtual exhibition design. Users’ perception of the authenticity of VR content during the experience can facilitate a deeper immersion experience while enhancing cultural attachment and satisfaction. Past research has demonstrated the important value of existential authenticity in cultural heritage tourism (Uslu et al. 2023), and this study emphasizes the important role of existential authenticity in cultural heritage VR scenarios, which is significant for cultural education and transmission, suggesting that subjective perceptions of authenticity and the state of being of the user in virtual environments can be effective in stimulating users’ emotions and identification.

The positive impact of immersion, a core component of user experience, on cultural attachment reveals how the depth of user experience in virtual environments promotes identification with and attachment to cultural values. This effect suggests that when users experience a high level of immersion in a VR exhibition, they are more likely to become emotionally connected to the cultural content on display, thereby deepening their understanding and appreciation of cultural heritage. However, it should be pointed out that, contrary to most research, immersion appeared to have a non-significant effect on satisfaction in the current study. Although most findings proved a positive impact between immersion and satisfaction, findings stipulate that a low-immersion VR experience alone may not be sufficient to ensure overall user satisfaction (Bujic and Hamari 2020; Omlor et al. 2022). This may be related to users’ expectations of other factors such as technology, content quality, and interaction design, because in the current technological environment, users have become accustomed to the high-quality immersive experience provided by advanced VR, and their expectations are relatively high. Low-immersion technology has limited interactive elements and cannot evoke a high-immersion emotional experience, making users feel that it lacks details, so it is unlikely to be satisfactory. This is particularly relevant considering that the current study utilized low-immersion virtual technology; it suggests that higher levels of immersion, as experienced with VR headsets, may lead to greater satisfaction in virtual environments (McLean and Barhorst 2022). Therefore, designers of virtual exhibitions for mobile devices need to consider several factors to provide a holistic, high-quality experience to satisfy users who expect more and more from the rapidly updating state-of-the-art.

Second, RO2 was answered by the effect of cultural attachment on satisfaction, re-use intention, and social sustainability, further emphasizing the central role of cultural factors in the virtual exhibition experience. Users’ emotional attachment to cultural content enhances their satisfaction and stimulates their intention to reuse the virtual exhibition at Cloud Tour Dunhuang, which may positively impact the promotion of social sustainability. This suggests that promoting and transmitting culture through virtual exhibitions and the significant positive impact of cultural attachment on environmentally responsible behaviors (Cheng and Chen 2022) may also effectively promote social value sustainability in the context of cultural heritage.

The effect of satisfaction on reuse intentions and social sustainability further confirms user satisfaction’s critical role in forming behavioral intentions. High satisfaction levels enhance users’ reuse intentions (Alam et al. 2024; Trunfio et al. 2022), which is crucial for the long-term success of virtual exhibitions. Simultaneously, this increase in satisfaction is also consistent with the goal of social sustainability, suggesting that enhancing social well-being and people’s happiness through increased user satisfaction implies realizing social sustainability.

Finally, RO3 was empirically illustrated by the significant positive impact of reuse intention on social sustainability, with impacts suggesting that continued user engagement has the potential to contribute to the achievement of social sustainability goals (Akhtar et al. 2021; Talwar et al. 2022), reflecting the fact that the virtual exhibition of the Cloud Tour Dunhuang’s intention to reuse contributes in enhancing social well-being, preserving and transmitting culture, education and knowledge dissemination, and shaping social and cultural identity.

Theoretical implications

This study empirically investigates the VR online exhibition experience of the Cloud Tour Dunhuang applet by extending the SOR (Stimulus-Organism-Response) model, significantly enhancing its applicability in diverse contexts. The findings validated the positive impacts of existential authenticity, immersion, and cultural attachment on user satisfaction and reuse intentions. It was also revealed how these factors indirectly contribute to social sustainability, thereby addressing a notable gap in the literature on VR tourism technology and its implications for social sustainability.

First, this research emphasizes the importance of subjective experiences of realism in fostering immersion and cultural attachment within the design of virtual exhibitions. By highlighting the nuanced relationship between the perceived realism of VR experiences and users’ cognitive and emotional responses, this research provides new perspectives on how digital presentations of cultural heritage can be optimized (Atzeni et al. 2022). These insights underscore the need for designers and stakeholders in the cultural heritage sector to prioritize user engagement through realistic representations that resonate with visitors’ expectations and cultural values.

The findings confirm the positive relationship between immersion and cultural attachment, corroborating previous research that indicates immersive experiences can deepen users’ identification with cultural values (Chang and Chiang 2022). Although it was observed that immersion did not have a statistically significant effect on overall user satisfaction in this study, this finding highlights the complexity of user experiences in VR contexts. It suggests future research needs to explore a wider array of influencing factors. Variables such as the degree of immersion, the quality and relevance of content, and the esthetic and interactive aspects of design should be systematically studied to comprehensively understand user satisfaction in immersive environments.

The significant effects of cultural attachment on satisfaction, intentions to reuse, and social sustainability further underscore the central role that cultural factors play in shaping virtual exhibition experiences. This empirical evidence highlights the importance of fostering cultural connections through VR experiences, which can support the sustainability of cultural heritage and reinforce social values. By integrating cultural narratives and promoting cultural education through immersive technologies, practitioners can enhance cultural heritage’s relevance, facilitating enjoyment and a deeper understanding of social contexts and histories.

Finally, the findings reveal a compelling relationship between the intention to reuse these immersive experiences and social sustainability, suggesting that sustained user engagement can promote significant social outcomes. This connection provides a theoretical basis for initiatives that leverage VR technologies for socially responsible goals, encompassing cultural preservation, education, and knowledge dissemination. By engaging users repeatedly with cultural content through immersive experiences, stakeholders can contribute to the perpetuation of social well-being, foster cultural understanding, and shape social and cultural identities in a rapidly changing digital landscape.

Practical implications

The results of this study elicit several managerial perspectives that provide valuable insights for cultural heritage managers and destination marketers attempting to utilize advanced technologies to improve the effectiveness of heritage marketing and promotion. First, by revealing the positive impact of presence authenticity on immersion, cultural attachment, and satisfaction, this study emphasizes the importance of valuing users’ subjective perceptions of authenticity in virtual exhibit design. This provides managers and VR designers with strategies to enhance user satisfaction by increasing the authenticity of the user experience. In particular, the positive impact of immersion on cultural attachment implies that VR designers should focus on the realistic reproduction of VR scenes of cultural heritage to enhance the immersive effect, for example, the more exquisite the production and the more delicate and realistic the performance, the more it can inspire users to identify with and take pride in their culture.

Second, this study points out the non-significant effect of immersion on satisfaction and emphasizes that when designing a VR experience, managers should consider factors such as VR equipment, content, and interaction design at various levels of immersion, in addition to immersion itself. Nowadays, in the era of rapid technological development, users seem unsatisfied with the immersive experience of low-immersion VR equipment. The results help managers optimize the allocation of resources and understand the attitude of users to use, highlight the problem and targeted correction, such as to strengthen the development and promotion of investment in the medium, full immersion VR technology, and provide a higher quality of the overall experience.

In addition, the impact of cultural attachment on satisfaction, reuse intentions, and social sustainability emphasizes the centrality of cultural elements in cultural heritage virtual exhibitions. Managers can utilize these findings to develop more culturally engaging content that enhances users’ emotional attachment and reuse intentions, such as increasing the interactivity of cultural quizzes or incorporating gameplay rewards and collection mechanisms, thereby advancing social sustainability goals.

Finally, the impact of intention to reuse on social sustainability suggests that continued user participation is critical to social well-being and cultural heritage, and directly illustrates the critical contribution of VR technology use to social sustainability in the context of cultural heritage. This provides a series of insights for managers that incentivizing sustained user engagement contributes to disseminating cultural education, awareness of cultural preservation, and increased participation. In this context, heritage site managers should work with VR designers and producers, policy makers, destination marketers, and tour operators to develop promotional and marketing strategies contributing to tourism sustainability.

Limitations and future research directions

Along with theoretical contributions and managerial implications, this study faced some limitations. First, from a conceptual perspective, this study only focused on existential authenticity; other authenticities (objective authenticity and constructed authenticity) were excluded, and perceived value could be added to explore its mediating role. Second, future research can increase the diversity of the study population, such as exploring foreign users or increasing the proportion of middle-aged and elderly respondents. It can focus on teenagers using VR for learning to explore its educational role. Moreover, the two applets, Cloud Tour Dunhuang and Cloud Tour Palace, can be explored for a comparative study. Since this study targets online VR exhibitions, offline VR equipment can also be used to study the full-immersive experience and a comparative study between online and offline. In order to enhance the integration of both VR and gaming, research can be done specifically to explore cultural heritage-related gaming experiences through MDA (mechanics-dynamics-esthetics), as well as through the Octalysis framework to explore the core drivers of gaming. Finally, apart from social sustainability, future research could explore the role of VR technologies on sustainability in three dimensions: environmental, economic, and social.

Data availability

Data is provided in the supplementary information files.

References

Adachi R, Cramer EM, Song H (2020) Using virtual reality for tourism marketing: A mediating role of self-presence. Soc Sci J 1:14. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0150508

Ahmed ZA, Qaed FAlmurbati N (2020) Enhancing museums’ sustainability through digitalization. In: 2020 Second International Sustainability and Resilience Conference: Technology and Innovation in Building Designs. IEEE, pp. 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEEECONF51154.2020.9319977

Ahuja AS, Polascik BW, Doddapaneni D, Byrnes ES, Sridhar J (2023) The digital metaverse: Applications in artificial intelligence, medical education, and integrative health. Integr Med Res 12(1):100917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.imr.2022.100917

Akhtar N, Khan N, Mahroof Khan M, Ashraf S, Hashmi MS, Khan MM, Hishan SS (2021) Post-COVID 19 tourism: Will digital tourism replace mass tourism? Sustainability 13(10):5352. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13105352

Alam MN, Turi JA, Bhuiyan AB, Kharusi SA, Oyenuga M, Zulkifli N, Iqbal J (2024) Factors influencing intention for reusing virtual reality (VR) at theme parks: the mediating role of visitors satisfaction. Cogent Soc Sci 10(1):2298898. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2023.2298898

Alcañiz M, Bigné E, Guixeres J (2019) Virtual reality in marketing: a framework, review, and research agenda. Front Psychol 10:1530. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01530

Alfaro L, Rivera C, Luna-Urquizo J, Zuniga JC, Portocarrero A, Raposo AB (2019) Immersive technologies in marketing: state of the art and a software architecture proposal. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl 10(10):482–490. https://doi.org/10.14569/IJACSA.2019.0101064

Anand K, Arya V, Suresh S, Sharma A (2022) Quality dimensions of augmented reality-based mobile apps for smart-tourism and its impact on customer satisfaction & reuse intention. Tour Plan Dev 20:236–259. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568316.2022.2137577

Ardolino M, Rapaccini M, Saccani N, Gaiardelli P, Crespi G, Ruggeri C (2018) The role of digital technologies for the service transformation of industrial companies. Int J Prod Res 56(6):2116–2132. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2017.1324224

Arya V, Verma H, Sethi D, Agarwal R (2019) Brand authenticity and brand attachment: how online communities built on social networking vehicles moderate the consumers’ brand attachment. IIM Kozhikode Soc. Manag Rev 8(2):87–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/2277975219825508

Asyraff MA, Hanafiah MH, Aminuddin N, Mahdzar M (2023) Adoption of the Stimulus-Organism-Response (SOR) model in hospitality and tourism research: systematic literature review and future research directions. https://fslmjournals.taylors.edu.my/wp-content/uploads/APJIHT/APJIHT-2023-12-1/APJIHT-121_P2.pdf

Atzeni M, Del Chiappa G, Mei Pung J (2022) Enhancing visit intention in heritage tourism: The role of object‐based and existential authenticity in non‐immersive virtual reality heritage experiences. Int J Tour Res 24(2):240–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2497

Bafadhal AS, Hendrawan MR (2019) Exploring the immersion and telepresence in gamified virtual tourism experience toward tourist’s behaviour. In: Annual International Conference of Business and Public Administration. AICoBPA, pp. 53–56. https://doi.org/10.2991/aicobpa-18.2019.12

Beck J, Rainoldi M, Egger R (2019) Virtual reality in tourism: a state-of-the-art review. Tour Rev 74(3):586–612. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-03-2017-0049

Bikar Singh SS, Kamaluddin MR, Yahaya A, Rahman Z, Mohamed N, Krishnan A, Rathakrishnan B (2022) Academic stress and life satisfaction as social sustainability among university students. Int J Eval Res Educ 1778–1786. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijere.v11i4.22682

Blumenthal V, Gjerald O (2022) ‘You just get sucked into it’: extending the immersion process model to virtual gameplay experiences in managed visitor attractions. Leis Stud 41(5):722–741. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2022.2049627

Bogicevic V, Seo S, Kandampully JA, Liu SQ, Rudd NA (2019) Virtual reality presence as a preamble of tourism experience: the role of mental imagery. Tour Manag 74:55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.02.009

Brown L (2013) Tourism: a catalyst for existential authenticity. Ann Tour Res 40:176–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.08.004

Buhalis D, Leung D, Lin M (2023) Metaverse as a disruptive technology revolutionising tourism management and marketing. Tour Manag 97:104724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2023.104724

Bujic M, Hamari J (2020) Satisfaction and willingness to consume immersive journalism: Experiment of differences between VR, 360 video, and article. In: Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Academic Mindtrek, 120–125. https://doi.org/10.1145/3377290.3377310

Buonincontri P, Marasco A, Ramkissoon H (2017) Visitors’ experience, place attachment and sustainable behaviour at cultural heritage sites: a conceptual framework. Sustainability 9(7). https://doi.org/10.3390/su9071112

Cadet LB, Chainay H (2020) Memory of virtual experiences: role of immersion, emotion and sense of presence. Int J Hum Comput Stud 144:102506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2020.102506

Caciora T, Herman GV, Ilieș A, Baias Ș, Ilieș DC, Josan I, Hodor N (2021) The use of virtual reality to promote sustainable tourism: a case study of wooden churches historical monuments from Romania. Remote Sens 13(9):1758. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs13091758

Carmigniani J, Furht B, Anisetti M, Ceravolo P, Damiani E, Ivkovic M (2011) Augmented reality technologies, systems and applications. Multimed Tools Appl 51(1):341–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11042-010-0660-6

Chang HH, Chiang CC (2022) Is virtual reality technology an effective tool for tourism destination marketing? A flow perspective. J Hospitality Tour Technol 13:427–440. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTT-03-2021-0076

Chen G, So KKF, Hu X, Poomchaisuwan M (2022) Travel for affection: a stimulus-organism-response model of honeymoon tourism experiences. J Hospitality Tour Res 46(6):1187–1219. https://doi.org/10.1177/10963480211011720

Cheng L-K, Huang H-L (2022) Virtual tourism atmospheres: the effects of pleasure, arousal, and dominance on the acceptance of virtual tourism. J Hospitality Tour Manag 53:143–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2022.10.002

Cheng Z, Chen X (2022) The effect of tourism experience on tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior at cultural heritage sites: the mediating role of cultural attachment. Sustainability 14(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/su14010565

Chin CH, Wong WPM, Kiu ALH, Thong JZ (2023) Intention to use virtual reality in sarawak tourism destinations: a test of stimulus-organism-response (SOR) model. Geoj Tour Geosites 47(2):551–562. https://doi.org/10.30892/gtg.47223-1055

Choi B, Kim J (2021) Changes and challenges in museum management after the COVID-19 pandemic. J Open Innov Technol Mark Complex 7(2):148. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7020148

Çiftçi ŞF, Çizel B (2024) Exploring relations among authentic tourism experience, experience quality, and tourist behaviours in phygital heritage with experimental design. J Destination Mark Manag 31:100848. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2023.100848

Cole ST, Illum SF (2006) Examining the mediating role of festival visitors’ satisfaction in the relationship between service quality and behavioral intentions. J Vacat Mark 12(2):160–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766706062156

Collin-Lachaud I, Passebois J (2008) Do immersive technologies add value to the museumgoing experience? An exploratory study conducted at France’s Paléosite. Int J Arts Manag 11:60–71. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41064975

Daassi M, Debbabi S (2021) Intention to reuse AR-based apps: the combined role of the sense of immersion, product presence and perceived realism. Inf Manag 58(4):103453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2021.103453

Dağ K, Çavuşoğlu S, Durmaz Y (2023) The effect of immersive experience, user engagement and perceived authenticity on place satisfaction in the context of augmented reality. Library Hi Tech. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHT-10-2022-0498

El-Said O, Aziz H (2021) Virtual tours a means to an end: an analysis of virtual tours’ role in tourism recovery post COVID-19. J Travel Res https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287521997567

Ercan F (2020) An examination on the use of immersive reality technologies in the travel and tourism industry. Bus Manag Stud Int J 8(2):2348–2383. https://doi.org/10.15295/bmij.v8i2.1510

Eslami S, Khalifah Z, Mardani A, Streimikiene D, Han H (2019) Community attachment, tourism impacts, quality of life and residents’ support for sustainable tourism development. J Travel Tour Mark 36(9):1061–1079. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2019.1689224

Fan X, Jiang X, Deng N (2022) Immersive technology: a meta-analysis of augmented/virtual reality applications and their impact on tourism experience. Tour Manag 91:104534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2022.104534

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error: algebra and statistics. Sage Publications Sage CA, Los Angeles, CA. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800313

Gao BW, Zhu C, Song H, Dempsey IMB (2022) Interpreting the perceptions of authenticity in virtual reality tourism through postmodernist approach. Inf Technol Tour 24(1):31–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-022-00221-0

Genc V, Gulertekin Genc S (2023) The effect of perceived authenticity in cultural heritage sites on tourist satisfaction: the moderating role of aesthetic experience. J Hospitality Tour Insights 6(2):530–548. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHTI-08-2021-0218

Go H, Kang M (2023) Metaverse tourism for sustainable tourism development: tourism agenda 2030. Tour Rev 78(2):381–394. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-02-2022-0102

Gundersen MG, Heide M, Olsson UH (1996) Hotel guest satisfaction among business travelers: what are the important factors? Cornell Hotel Restaur Adm Q 37(2):72–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/001088049603700222

Han DID, Boerwinkel M, Haggis-Burridge M, Melissen F (2022) Deconstructing immersion in the experience economy framework for immersive dining experiences through mixed reality. Foods 11(23):3780. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods11233780

Hair JF, Black WC, Babin BJ, Anderson RE (2009) Multivariate Data Analysis. 7th Edition, Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River

Hair JF, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2011) PLS-SEM: Indeed a silver bullet. J Mark Theory Pr 19(2):139–152. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679190202

Hair J, Hollingsworth CL, Randolph AB, Chong AYL (2017) An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Ind Manag Data Syst 117(3):442–458. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-04-2016-0130

Han D-ID, Tom Dieck MC, Jung T (2019) Augmented Reality Smart Glasses (ARSG) visitor adoption in cultural tourism. Leis Stud 38(5):618–633. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2019.1604790

Han S, Yang H (2018) Understanding adoption of intelligent personal assistants: a parasocial relationship perspective. Ind Manag Data Syst 118(3):618–636. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-05-2017-0214

Handa M, Aul G, Bajaj S (2012) Immersive technology–uses, challenges and opportunities. Int J Comput Bus Res 6(2):1–11

Hansen AH, Mossberg L (2013) Consumer immersion: a key to extraordinary experiences. https://www.elgaronline.com/display/edcoll/9781781004210/9781781004210.00017.xml

Hansson P, Öhman J (2022) Museum education and sustainable development: a public pedagogy. Eur Educ Res J 21(3):469–483. https://doi.org/10.1177/14749041211056443

Haywood N, Cairns P (2005) Engagement with an interactive museum exhibit. In: Proceedings of HCI, Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-84628-249-7_8

Helgadóttir G, Einarsdóttir AV, Burns GL, Gunnarsdóttir GÞ, Matthíasdóttir JME (2019) Social sustainability of tourism in Iceland: a qualitative inquiry. Scand J Hospitality Tour 19(4–5):404–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2019.1696699

Higgins-Desbiolles F (2018) Sustainable tourism: sustaining tourism or something more? Tour Manag Perspect 25:157–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2017.11.017

Hincapie M, Cifuentes LM, Valencia-Arias A, Quiroz-Fabra J (2023) Geoheritage and immersive technologies: bibliometric analysis and literature review. Epis J Int Geosci 46(1):101–115. https://doi.org/10.18814/epiiugs/2022/022016

Hoang TDT, Brown G, Kim AKJ (2020) Measuring resident place attachment in a World Cultural Heritage tourism context: the case of Hoi An (Vietnam). Curr Issues Tour 23(16):2059–2075. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1751091

Hong Y, Fang Y, Yang Y, Phua DY (2013) Cultural attachment: a new theory and method to understand cross-cultural competence. J Cross Cultural Psychol 44(6):1024–1044. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022113480039

Hudson S, Matson-Barkat S, Pallamin N, Jegou G (2019) With or without you? Interaction and immersion in a virtual reality experience. J Bus Res 100:459–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.10.062

Jacoby J (2002) Stimulus‐organism‐response reconsidered: an evolutionary step in modeling (consumer) behavior. J Consum Psychol 12(1):51–57. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327663JCP1201_05

Jiang C, Phoong SW (2023) A ten-year review analysis of the impact of digitization on tourism development (2012–2022). Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10(1):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02150-7

Kim H, Kang S, Song C, Lee MJ (2020) How hotel smartphone applications affect guest satisfaction in applications and re-use intention? An experiential value approach. J Qual Assur Hospitality Tour 21(2):209–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2019.1653242

Kim MJ, Lee C-K, Jung T (2020) Exploring consumer behavior in virtual reality tourism using an extended stimulus-organism-response model. J Travel Res 59(1):69–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518818915

Kim M, Lee G (2022) The effect of servicescape on place attachment and experience evaluation: The importance of exoticism and authenticity in an ethnic restaurant. Int J Contemp Hospitality Manag 34(7):2664–2683. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-07-2021-0929

Kim S-E, Kim H, Jung S, Uysal M (2023) The determinants of continuance intention toward activity-based events using a virtual experience platform (VEP). Leis Sci 47:976–1001. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2023.2172116

Kline RB (2019) Becoming a behavioral science researcher: a guide to producing research that matters. Guilford Publications. https://books.google.com.my/books?id=zO6sDwAAQBAJ

Klippel A, Zhao J, Jackson KL, La Femina P, Stubbs C, Wetzel R, Blair J, Wallgrün JO, Oprean D (2019) Transforming earth science education through immersive experiences: delivering on a long held promise. J Educ Comput Res 57(7):1745–1771. https://doi.org/10.1177/07356331198540

Kock N (2017) Common method bias: a full collinearity assessment method for PLS-SEM. In: Latan H, Noonan R (eds), Partial least squares path modeling: basic concepts, methodological issues and applications. Springer International Publishing. 245–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-64069-3_11

Kwok AO, Koh SG (2021) COVID-19 and extended reality (XR). Curr Issues Tour 24(14):1935–1940. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1798896

Kyrlitsias C, Christofi M, Michael-Grigoriou D, Banakou D, Ioannou A (2020) A virtual tour of a hardly accessible archaeological site: the effect of immersive virtual reality on user experience, learning and attitude change. Front Comput Sci 2:23. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomp.2020.00023

Lee IS, Lee TJ, Arcodia C (2014) The effect of community attachment on cultural festival visitors’ satisfaction and future intentions. Curr Issues Tour 17(9):800–812. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.770450

Li J, Peng X, Liu X, Tang H, Li W (2024) A study on shaping tourists’ conservational intentions towards cultural heritage in the digital era: exploring the effects of authenticity, cultural experience, and place attachment. J Asian Architecture Build Eng 1–20, https://doi.org/10.1080/13467581.2024.2321999

Li M, Sun X, Zhu Y, Qiu H (2024) Real in virtual: the influence mechanism of virtual reality on tourists’ perceptions of presence and authenticity in museum tourism. Int J Contemp Hospitality Manag 36:3651–3673. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-07-2023-0957

Li S, Zhu B, Yu Z (2024) The impact of cue-interaction stimulation on impulse buying intention on virtual reality tourism e-commerce platforms. J Travel Res 63(5):1256–1279. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875231183163

Li W, Xiao JX (2021) User experience in digital museums: a case study of the palace museum in Beijing. In: Culture and computing. Interactive cultural heritage and arts: 9th International Conference, C&C 2021, held as part of the 23rd HCI international conference, HCII 2021, 436–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-77411-0_28

Liberatore MJ, Wagner WP (2021) Virtual, mixed, and augmented reality: a systematic review for immersive systems research. Virtual Real 25(3):773–799. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-020-00492-0

Liu R, Wang L, Lei J, Wang Q, Ren Y (2020) Effects of an immersive virtual reality‐based classroom on students’ learning performance in science lessons. Br J Educ Technol 51(6):2034–2049. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13028

Liu Y, Hou Y, Hong Y (2023) The profiles, predictors, and intergroup outcomes of cultural attachment. Personal Soc Psychol Bullet. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672231190753

Loach K, Rowley J, Griffiths J (2017) Cultural sustainability as a strategy for the survival of museums and libraries. Int J Cultural Policy 23(2):186–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/10286632.2016.1184657

López MFB, Virto NR, Manzano JA, Miranda JG-M (2018) Residents’ attitude as determinant of tourism sustainability: The case of Trujillo. J Hospitality Tour Manag 35:36–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2018.02.002

Loureiro SMC, Guerreiro J, Ali F (2020) 20 years of research on virtual reality and augmented reality in tourism context: a text-mining approach. Tour Manag 77:104028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.104028

Lu J, Xiao X, Xu Z, Wang C, Zhang M, Zhou Y (2022) The potential of virtual tourism in the recovery of tourism industry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Issues Tour 25(3):441–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1959526

Lunardo R, Ponsignon F (2020) Achieving immersion in the tourism experience: the role of autonomy, temporal dissociation, and reactance. J Travel Res 59(7):1151–1167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519878509

Manchanda M, Deb M (2021) Effects of multisensory virtual reality on virtual and physical tourism during the COVID-19 pandemic. Curr Issues Tour 25:1748–1766. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1978953

Marín-García A, Gil-Saura I, Ruiz-Molina M-E (2022) Do innovation and sustainability influence customer satisfaction in retail? A question of gender. Econ Res 35(1):546–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2021.1924217

McGhie H (2020) Evolving climate change policy and museums. Mus Manag Curatorship 35(6):653–662. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2020.1844589

McLean G, Barhorst JB (2022) Living the experience before you go… But did it meet expectations? The role of virtual reality during hotel bookings. J Travel Res 61(6):1233–1251. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875211028313

Mehrabian A, Russell JA (1974) An approach to environmental psychology. The MIT Press

Melo M, Coelho H, Gonçalves G, Losada N, Jorge F, Teixeira MS, Bessa M (2022) Immersive multisensory virtual reality technologies for virtual tourism. Multimed Syst 28(3):1027–1037. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00530-022-00898-7

Mou Y, Fan J, Ding Z, Khan I (2024) Impact of virtual reality immersion on customer experience: Moderating effect of cross-sensory compensation and social interaction. Asia Pac J Mark Logist 36(1):26–47. https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-11-2022-0920

Mütterlein J (2018) The three pillars of virtual reality? Investigating the roles of immersion, presence, and interactivity. In: Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. https://doi.org/10.24251/HICSS.2018.174

Nam K, Dutt CS, Baker J (2022) Authenticity in objects and activities: determinants of satisfaction with virtual reality experiences of heritage and non-heritage tourism sites. Inf Syst Front 25:1219–1237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-022-10286-1