Abstract

Virtual reality (VR) is increasingly being used to promote altruistic behavior, yet its mechanisms for enhancing altruistic behavior remain underexplored. This study investigates how cognitive absorption in VR enhances behavioral empathy, drawing on cognitive absorption theory and the empathy-altruism model. Three studies were conducted using modified Delphi (m-Delphi), Fuzzy Decision Making and Trial Evaluation Laboratory (F-DEMATEL), structural equation modelling (SEM), and artificial neural networks (ANN), and data was collected from Taiwanese participants. The findings reveal that cognitive absorption increases cognitive and emotional engagement, which enhance cognitive and emotional empathy, leading to greater behavioral empathy. Serial mediation effects were confirmed, and guilt moderated the emotional empathy-behavioral empathy link. ANN analysis identified emotional empathy and focused attention as top predictors. The findings of this research provide theoretical and practical insights for designing VR-based tools to foster sustained prosocial behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Virtual reality (VR) is a three-dimensional technology that enables users to interact with computer-generated content in a hyper-realistic manner. It has over 170 million users globally and a projected penetration rate of 55.9% by 2028 (Jayaraman, 2024). Due to its ability to simulate realistic simulations and give users control, VR helps communicate complex issues (such as prosocial actions, which tend to be context specific) more effectively than traditional media (such as radios or television). Moreover, its ability to evoke presence and affective responses may lead to altruistic behaviors, VR has been dubbed the ultimate empathy machine (Herrera et al., 2018; Kang et al., 2021; Spinrad & Gal, 2018). Renowned organizations such as Global Citizen, Amnesty International, and UNICEF are using it to promote positive social change (Kandaurova & Lee, 2019; UNICEF, 2023). Despite its growing adoption, research on how VR can effectively foster altruistic behavior in social marketing is limited. Specifically, there is a lack of evidence on whether VR can elicit behavioral empathy, an outcome that signals deep-seated and sustained concern for others (Herrera et al., 2018; Spinrad & Gal, 2018). Given the increasing use of VR for altruistic communication and its potential to foster empathy-driven behavior, it is important to investigate its impact on behavioral empathy.

Empathy is an important motivator of altruistic behaviors (Lu et al., 2024; Shin, 2019). According to the empathy-altruism theory, empathy comprises cognitive (understanding another’s perspective), emotional (feeling another’s emotions), and behavioral (responding with supportive actions) dimensions (Abramson et al., 2020, Batson et al., 1991). Cognitive and emotional empathy have received more attention in altruism research due to their direct link with compassionate actions (Abramson et al., 2020; Lu et al., 2024). However, limited research has examined their links with behavioral empathy, a behavioral manifestation of empathy. Although both compassionate actions and behavioral empathy involve helping behaviors, behavioral empathy represents deeper and potentially more sustainable altruistic actions rooted in genuine concern rather than superficial motivations (Abramson et al., 2020; Lu et al., 2024). Building on prior knowledge that cognitive and affective responses to stimuli shape behavioral reactions (Pachankis, 2007; Shin, 2019; Ventura et al., 2020), this study explores how VR-stimulated cognitive and emotional empathy leads to behavioral empathy.

This research also examines the mechanisms by which VR arouses behavioral empathy. Engagement is necessary for users to absorb information from digital media (Yang, 2016). In the context of VR, engagement refers to a user’s active investment in a virtual environment (Kang et al., 2021). It comprises cognitive (mental investment in understanding the VR content) and emotional (emotional responses elicited by the VR experience) aspects (Balakrishna & Dwivedi, 2021; Yang, 2016). Engagement in technology usage helps users connect with content and internalize it, foster concern for others and potentially promote altruistic behaviors (Anthony et al., 2021). This research thus proposes that cognitive and emotional engagement enhance cognitive and emotional empathy, which in turn foster behavioral empathy. In addition, cognitive absorption (the state of deep involvement with technology) ensures effective communication (Jumaan et al., 2020) as it ensures that users are more fully present and active in the digital environment (Kang et al., 2021). Given that cognitive absorption involves active participation, this research explores its impact on engagement, which in turn affects cognitive, emotional, and behavioral empathy. Thus, this study illustrates the indirect mechanisms through which cognitive absorption affects behavioral empathy.

Failure to help others can cause moral discomfort and guilt (Kandaurova & Lee, 2019). This guilt can increase helping behavior (De Luca et al., 2016). Extant research on the role of guilt in helping behavior has focused on offline contexts (Shipley & van Riper, 2022; De Luca et al., 2016). Unlike offline environments, where guilt is reinforced through direct social feedback, and visible accountability, in virtual contexts, human behavior dynamics differ due to reduced interpersonal cues (Kang et al., 2021; Shipley & van Riper, 2022). On the other hand, VR’s immersive qualities can also heighten emotional responses by making experiences feel immediate and embodied (De Luca et al., 2016). These differences can make guilt in virtual contexts distinct from guilt in physical settings. Studying guilt in virtual contexts is essential for understanding how ethical behavior can be fostered through virtual experiences (Kandaurova & Lee, 2019). Thus, this research also examines the moderating role of guilt in the effects of cognitive and emotional empathy on behavioral empathy in VR contexts.

This research addresses the following questions: (1) Can the use of VR for communicating altruism enhance behavioral empathy? (2) Do cognitive and emotional engagement in VR enhance users’ empathy? (3) Does cognitive absorption enhance cognitive and emotional engagement in VR and behavioral empathy? (4) Does guilt moderate the effects of cognitive absorption, cognitive empathy, and emotional empathy on behavioral empathy?

To address these research questions, this research implemented three studies. Given that communication involves both information senders and receivers, data were collected from senders and recipients who had experience using VR for altruistic content. The senders were engaged through M-Delphi and F-DEMATEL methods, while SEM and ANN were used to analyze data obtained from receivers. The findings supported our theorization that cognitive absorption enhances behavioral empathy directly and indirectly. The moderating effects of guilt were also confirmed. The rest of the paper is structured as follows: the introduction is followed by a literature review, methodology, presentation of results, and discussion of the results.

Literature review

The empathy-altruism model and guilt in the VR context

The empathy-altruism model explains the mechanisms behind altruistic behavior. Central to this model is the concept of empathy. Empathy refers to the comprehension and sharing others’ emotional experiences (Shin, 2018). The model proposes that individuals tend to be altruistic when they experience strong empathy for those in need (Batson et al., 1991). This involves cognitive empathy, which consists of understanding another person’s perspective, thoughts, and feelings, and emotional empathy, which is the affective sharing of another individual’s emotions (Abramson et al., 2020; Cummins & Cui, 2014). Behavioral empathy manifests as actions directed towards helping others (Shin, 2018). In the empathy-altruism model, cognition shapes emotional responses and prepares individuals to understand the needs of others (Jeon et al., 2024). The combination of cognitive and emotional empathy leads to helping behavior, whereby understanding and emotional resonance are translated into actions aimed at alleviating the distress of others (Davis et al., 1987). Behavioral empathy, therefore, represents the altruistic outcomes driven by cognitive and emotional processes (Davis et al., 1987).

Given empathy’s important role in promoting altruism, previous research has extensively explored its antecedents from multiple perspectives, including neurological, social, and individual dimensions. Neurologically, empathy development has been linked to brain structures and executive functions critical for perspective-taking. Decety and Holvoet (2021) argued that cognitive empathy depends significantly on the maturation of executive functions in the brain, particularly emphasizing the medial prefrontal cortex’s centrality during tasks requiring perspective-taking (Decety & Michalska, 2020, Paradiso et al., 2021). Thus, neurological maturation provides the foundational capacity to understand and resonate emotionally with others.

While neurological research highlights the biological underpinnings of empathy, social research emphasizes external influences, particularly early familial socialization. Abramson et al. (2020) and Spinrad et al. (2018) established that parents play a vital role in shaping empathy by modeling and reinforcing prosocial behaviors. Through such practices, children develop moral identity and learn empathetic behaviors by observing, imitating, and internalizing prosocial norms and actions demonstrated by significant others (Morgan & Fowers, 2022). Thus, while biology sets the initial potential, social environments actively mold how empathy manifests and is reinforced behaviorally, emphasizing the critical role of social context and familial interactions.

Beyond neurological and social factors, research has also emphasised the role of individual-level variations, particularly personality traits, in shaping empathy. Traits such as agreeableness, openness and emotional stability consistently correlate with higher empathy levels (Abramson et al., 2020, Airagnes et al., 2021; Di Fabio & Kenny, 2021). Specifically, individuals high in agreeableness typically exhibit cooperative, compassionate, and supportive behaviors, which naturally predispose them to empathize with others (Abramson et al., 2020). Individuals who are high on openness to experience tend to show intellectual curiosity and appreciation of diverse perspectives. This enhances their cognitive capacity to understand varied emotional experiences (Airagnes et al., 2021). Emotional stability, on the other hand, allows individuals to manage their emotions effectively, preventing personal distress from overshadowing their capacity to empathically engage with others’ emotional states (Di Fabio & Kenny, 2021). Thus, these personality attributes determine the depth and consistency of empathy across various contexts and relationships.

Building on this understanding, the current study explores how empathy is shaped in VR contexts. VR provides unique opportunities for fostering empathy by cognitively immersing individuals in realistic, perspective-taking scenarios and emotionally engaging them through vividly simulated emotional experiences (Shin, 2018; Kandaurova & Lee, 2019). Specifically, this study examines cognitive absorption as a critical determinant enhancing empathy through VR’s immersive qualities. Extant research has shown that when users are cognitively absorbed, they invest heightened cognitive resources, and this facilitates deeper processing of information, emotions, and perspectives presented within the virtual scenario, which can potentially lead to the development of empathy (Jennett et al., 2008; Slater & Sanchez-Vives, 2016)

While empathy involves comprehending and resonating with others’ emotional states, translating empathy into concrete altruistic behaviors may depend on additional emotional mechanisms. One particularly influential emotional state is guilt, which is the moral discomfort that arises from awareness of having caused harm or failed to help others in distress (Tangney & Dearing, 2002). Prior research has demonstrated that guilt is a powerful motivation of behavior in altruistic contexts, as individuals who experience it often attempt to reduce their discomfort by engaging in prosocial behaviors (De Luca et al., 2016; Shipley & van Riper, 2022). Consequently, guilt can intensify the empathic response by adding an affective and moral urgency that prompts individuals to act upon their empathetic feelings.

In VR contexts, guilt may hold unique significance due to VR’s ability to vividly portray scenarios where individuals witness others’ distress but may feel limited or unable to intervene effectively, thus amplifying the emotional impact of guilt (Kandaurova & Lee, 2019). Experiencing vivid virtual scenarios can elicit stronger feelings of personal accountability and guilt when failing to respond to others’ needs, compared to more traditional media forms such as radio and television (Shipley & van Riper, 2022; Ventura et al., 2020). Against this background, the current research examines guilt as a boundary condition for the effects of cognitive and emotional empathy on behavioral empathy.

Cognitive absorption and virtual reality

The cognitive absorption theory explains how individuals become deeply engrossed in tasks (Leong, 2011). The theory is based on the concept of “flow,” which is a psychological state characterized by focus and enjoyment of a task (Balakrishnan & Dwivedi, 2021). Cognitive absorption entails intense concentration and motivation to perform a task. It has six dimensions, namely temporal dissociation (losing track of time and an altered perception of time’s passage) (Lunardo & Ponsignon, 2020), focused immersion (high levels of concentration, ignoring irrelevant stimuli (Balakrishnan & Dwivedi, 2021)), heightened enjoyment (the pleasure and satisfaction derived from immersive experiences (Reychav & Wu, 2015), control (perceived mastery over the activity and technology, with optimal absorption occurring when the task’s challenge aligns with one’s skills (Oh & Sundar, 2015)) and curiosity (ability to explore and understand the technology (Balakrishnan & Dwivedi, 2021)).

Research on cognitive absorption in VR reveals various cognitive and physiological outcomes. Higher cognitive absorption in VR enhances attention, memory, learning, and cognitive processing (Léger et al., 2014). Educational studies show that deeply engaged individuals in VR experiences exhibit high cognitive abilities and improved learning outcomes (Leong, 2011). Physiological research also confirms that cognitive absorption in VR positively affects physiological arousal, evidenced by changes in heart rate and conductance (Bolinski et al., 2021). In therapeutic contexts, cognitive absorption during VR exposure therapy sessions correlates with greater reductions in phobic symptoms, highlighting its importance for therapeutic efficacy (Kealy et al., 2019). Cognitive absorption significantly influences user experiences and behavioral intentions in VR. Virtual shopping enhances user satisfaction and revisits intentions (Talukdar & Yu, 2021). Additionally, it mediates the relationship between presence and enjoyment in VR environments (Skarbez et al., 2017).

Moreover, VR’s immersive qualities foster perspective-taking and reduce distractions, thereby supporting empathy development by enabling users to simulate others’ experiences and emotions (Ventura et al., 2020). Its capacity for behavioral modeling also makes it useful for cultivating social skills (Kang et al., 2021). Drawing on these findings from VR shopping, therapy, and social interaction contexts, this research proposes that cognitive absorption in VR facilitates empathy and altruistic behavior. Specifically, the observed enhancements in perspective-taking, social skill development, and emotional engagement across these applications suggest that cognitive absorption creates a psychological state conducive to empathetic understanding and prosocial action. These effects may be even more pronounced in the VR context because VR offers sensory immersion, interactivity, and perspective-taking opportunities that increase emotional and cognitive engagement (Ventura et al., 2020). The multisensory stimulation and embodied experiences unique to VR can intensify feelings of presence and empathy and thus enhance the emotional impact of simulated situations strongly than in traditional media (Herrera et al., 2018). As such, we build on the evidence from the shopping, therapy and social interaction contexts to argue that cognitive absorption in VR is a key mechanism driving empathy and altruistic responses in virtual environments.

In the context of VR, cognitive absorption may be conceptually likened to presence. Cognitive absorption refers to a deep state of engagement where users are intensely focused and lose track of time and external surroundings due to their immersion in the task or environment (Balakrishnan & Dwivedi, 2021). Thus, it involves cognitive and emotional involvement, where individuals feel fully absorbed by the activity they are engaged in and often leads to a flow-like experience (Lunardo & Ponsignon, 2020; Reychav & Wu, 2015). In contrast, presence in VR refers to the subjective feeling of “being there” in the virtual environment (Herrera et al., 2018). It is the psychological state where users perceive the virtual world as real, often blurring the boundaries between the physical and digital realms (Skarbez et al., 2017). While cognitive absorption focuses more on the internal, subjective experience of engagement and attention, presence emphasizes the external perception of virtual space and how convincingly it replicates reality. Although both are important in enhancing the overall VR experience, cognitive absorption is more about the mental state of immersion, whereas presence deals with the sensory and perceptual aspects of feeling physically situated in a virtual world.

Hypothesis development

The effect of cognitive absorption on engagement

Cognitive absorption is when an individual becomes deeply engaged and completely focused in VR (Bolinski et al., 2021). This intense focus enables individuals to explore tasks thoroughly, enhancing cognitive processing and engagement with the content (Léger et al., 2014). When cognitively absorbed, a person’s attention is concentrated, minimizing distractions and increasing mental involvement (Oh & Sundar, 2015). This efficient allocation of cognitive resources leads to better understanding, retention, and problem-solving abilities (Leong, 2011). As such, cognitive absorption positively influences cognitive engagement, fostering deep concentration and mental involvement, which improves learning, performance, and overall cognitive functioning (Léger et al., 2014).

Moreover, individuals deeply absorbed in an activity often experience enjoyment, fulfillment, and emotional resonance (Léger et al., 2014). This stems from the immersive nature of cognitive absorption, providing pleasure and satisfaction from heightened focus (Reychav & Wu, 2015; Leong, 2011). Deep absorption can lead to flow, which is characterized by complete immersion and enjoyment in VR usage (Shin, 2018). Flow is also accompanied by positive emotions, such as happiness, which can enhance emotional engagement (Oh & Sundar, 2015). Accomplishment and mastery during absorption also boost self-efficacy and emotional well-being (Frost et al., 2022).

Furthermore, VR can simulate diverse social situations, allowing users to understand different perspectives (Kandaurova & Lee, 2019). VR scenarios depicting social issues can evoke strong empathic responses by enabling users to experience others’ struggles (Yoo & Drumwright, 2018). As individuals observe and comprehend others’ struggles through VR, the moral elevation that results can lead them to execute behaviors that alleviate the suffering of others (Kang et al., 2021). The following hypotheses are proposed:

H1: Cognitive absorption positively affects (a) cognitive engagement, (b) emotional engagement (c) behavioral empathy.

The effect of engagement on empathy

VR creates immersive experiences that evoke strong emotional responses and connections with virtual characters or situations, laying the foundation for empathic understanding (Bolinski et al., 2021). As users explore VR and encounter characters expressing emotions such as sadness, they are prompted to empathize, mirror, and understand these feelings (Ventura et al., 2020). This emotional resonance enhances users’ mental connection with the virtual characters’ experiences, facilitating cognitive understanding (Jeon et al., 2024). Emotional engagement in VR motivates users to mentally simulate the perspectives of the characters, fostering cognitive empathy (Jeon et al., 2024). By empathizing with the emotions portrayed, users infer the underlying reasons and motivations, enhancing their understanding of the characters’ situations and perspectives (Jeon et al., 2024). This empathic inference process helps users grasp the complexities of human emotions and behavior, leading to greater cognitive empathy (Han et al., 2024).

Furthermore, emotional engagement in VR reinforces cognitive empathy by enhancing users’ understanding of the relationship between emotions and perspectives. By forming emotional connections with virtual characters and observing how decisions and actions influence these characters’ emotions, users gain valuable insights into the social cues and dynamics that foster empathic understanding (Abramson et al., 2020; Tsang, 2018). This iterative process of emotional engagement and cognitive inference in VR strengthens both emotional and cognitive empathy, creating a more comprehensive empathic experience that goes beyond mere cognitive understanding. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2: Cognitive engagement positively affects (a) cognitive empathy and (b) emotional empathy.

H3: Emotional engagement positively affects (a) cognitive empathy and (b) emotional empathy.

The effects of cognitive empathy and emotional empathy on behavioral empathy

In virtual settings, cognitive empathy enables individuals to understand and interpret the emotions and perspectives of others (Jeon et al., 2024). This understanding forms the foundation of helping behavior by guiding individuals to recognize when and how to respond empathetically (Han et al., 2024). By grasping others’ feelings or thoughts, people can adjust their behavior to be empathetic and supportive (Tsang, 2018). Cognitive empathy also aids in navigating social situations effectively, fostering empathy-driven behaviors (Jeon et al., 2024). Understanding social norms, cultural differences, and individual preferences through VR interactions enables individuals to interact considerately, use appropriate language, respect boundaries, and appreciate diverse perspectives (Lu et al., 2024).

Emotional empathy from VR experiences fosters emotional empathy (Lu et al., 2024). This emotional resonance drives behaviors demonstrating care, compassion, and support (Abramson et al., 2020; Cummins & Cui, 2014). Emotional empathy prompts a visceral response to others’ emotions, leading to actions to alleviate their suffering (Frost et al., 2022). Additionally, emotional empathy fosters a sense of interconnectedness and shared humanity, promoting pro-social behaviors and altruism (Tsang, 2018; Cummins & Cui, 2014). Recognizing one’s emotional responses in others highlights the commonality of human experiences, cultivating empathy-driven actions. This empathy inspires acts of kindness, generosity, and compassion towards those in need (Ventura et al., 2020). The following hypotheses are proposed:

H4: Cognitive empathy positively affects behavioral empathy.

H5: Emotional empathy positively affects behavioral empathy.

The mediating roles of engagement and empathy

Cognitive empathy helps individuals understand others’ perspectives and guides their actions to be more supportive (Lu et al., 2024). Emotional empathy, on the other hand, fosters a deep emotional connection, motivating compassionate actions (Abramson et al., 2020). Together, cognitive and emotional empathy drive behaviors that consider the needs of others (Lu et al., 2024). In addition, VR simulations prompt users to consider characters’ thoughts and motivations, fostering cognitive empathy (Kang et al., 2021). Navigating virtual environments and making impactful decisions deepen understanding of different perspectives (Tsang, 2018). Cognitive engagement in VR can also evoke emotional empathy as users emotionally invest in the characters and narratives presented (Kang et al., 2021). As individuals interact with and witness the emotional struggles and triumphs of virtual characters, they develop a heightened sensitivity to others’ feelings, fostering emotional empathy (Lu et al., 2024; Ventura et al., 2020). Thus, VR’s combination of cognitive engagement and emotional immersion cultivates both cognitive and emotional empathy.

Emotional engagement in VR fosters cognitive and emotional empathy by immersing users in simulations that evoke deep emotional responses (Jeon et al., 2024). This immersion prompts users to experience others’ emotions vicariously, enhancing emotional empathy (Han et al., 2024). Interactive VR experiences also challenge users to consider different perspectives, enhancing cognitive empathy (Abramson et al., 2020). This blend of emotional and cognitive responses in VR fosters a nuanced understanding of others’ experiences, promoting empathy and compassion in real-world interactions. Furthermore, cognitive absorption in VR enhances engagement by fully immersing users in virtual experiences. This intense focus facilitates better cognitive processing, understanding complex scenarios, and considering diverse perspectives, in addition to creating a sense of presence and emotional connection with virtual characters and narratives (Balakrishnan & Dwivedi, 2021). By maximizing cognitive and emotional engagement, VR serves as a powerful platform for fostering empathy and deepening understanding (Anthony et al., 2021). Given these interrelationships, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H6a: Cognitive engagement and cognitive empathy serially mediate the effect of cognitive absorption on behavioral empathy.

H6b: Cognitive engagement and emotional empathy serially mediate the effect of cognitive absorption on behavioral empathy.

H6c: Emotional engagement and cognitive empathy serially mediate the effect of cognitive absorption on behavioral empathy.

H6d: Emotional engagement and emotional empathy serially mediate the effect of cognitive absorption on behavioral empathy.

The moderating role of guilt

Guilt in altruism serves as both a motivator and a moral compass that drives individuals to perform acts of kindness, as it helps create a moral balance in the individual (Lee et al., 2023). It arises from a moral obligation towards others that emanates from an awareness of one’s privilege, opportunities to help, or past failures to help. It compels individuals to address their perceived moral shortcomings through altruistic actions and reinforces moral values that push individuals to fulfill their duty towards others (Kandaurova & Lee, 2019; De Luca et al., 2016).

Cognitive empathy enables individuals to understand and appreciate others’ perspectives (Lu et al., 2024), potentially leading to altruistic actions. On the other hand, emotional empathy allows individuals to share and resonate with the emotions portrayed, prompting compassionate responses (Shin, 2019). Guilt can amplify these effects, especially when individuals perceive suffering in the VR content, because it drives individuals to take actions that align with their moral obligations (Shipley & van Riper, 2022). Witnessing acts of kindness in VR can evoke guilt in those who feel they have not been sufficiently altruistic, prompting them to engage in altruistic behaviors to alleviate guilt and align their actions with their values (Shipley & van Riper, 2022). Thus, guilt strengthens the impact of cognitive and emotional empathy on behavioral empathy, hence the following hypotheses:

H7a: Guilt moderates the effect of cognitive empathy on behavioral empathy.

H7b: Guilt moderates the effect of emotional empathy on behavioral empathy.

The research model and hypotheses are shown in Fig. 1. The model represents hypothesized relationships between variables, highlighting latent constructs and observed indicators.

Methodology

This study used M-Delphi, F-DEMATEL, SEM, and ANN approaches to analyze its data.

Modified Delphi (m-Delphi)

This research applied the 9 predictor variables (temporal dissociation, focused immersion, heightened enjoyment, control, curiosity, cognitive engagement, emotional engagement, cognitive empathy and emotional empathy) in the first round of the M-Delphi study. 21 experts with more than 5 years of experience in the VR communication context (especially altruistic communication) were invited to rate how these variables affected information quality, with each variable receiving a combined rating above 80%, exceeding the 75% threshold. At the beginning of the survey, a screening question “have you ever used VR to spread altruistic content” was asked, and only those who responded “yes” were allowed to take part in the research. The questionnaire was administered in person, but the participants were kept anonymous – they did not know who their fellow participants were. The participants were asked to rate, on a scale of 1 to 7, the extent to which they believed each of the proposed factors influenced behavioral empathy. After the first round, experts proposed adding focused attention and amusement as factors. These were included in the second round. All factors, except amusement, rated above 80%; amusement initially rated at 69.52% but rose above the 75.24% threshold by the third round. The m-Delphi process confirmed that all eleven factors influenced behavioral empathy, and they were included in the F-DEMATEL procedure. Table S1 in the supplementary files presents the proposed determinants of behavioral empathy identified through the M-Delphi process, which were subsequently evaluated using the F-DEMATEL method.

F-DEMATEL

DEMATEL refers to multicriteria decision methods used to understand interdependencies and interactions among factors in complex decision settings. The external factors that come into play in communication render it an uncertain endeavor. In addition, DEMATEL ratings are based on experience, which could lead to subjectivity (Shieh et al., 2010). Applying the fuzzy theory to DEMATEL reduces subjectivity and ensures representative reliability (Liao, 2020). Several studies have demonstrated the applicability of the F-DEMATEL contexts, such as supply chain management (Paul et al., 2021) and health communication (Liao, 2020). The computational steps involved in F-DEMATEL are explained below.

Step 1: Determination of the influencing factors in the system

A literature review is conducted to determine the factors affecting the outcome variable.

Step 2: Designing the fuzzy linguistic scale

The degrees of influence applied in the F-DEMATEL method are usually in five levels: (see Table S2 in the supplementary file). Participants use the semantic scale to make ratings about causal relationships among factors in the system.

Step 3: Computing the initial direct relation fuzzy matrix

Every respondent’s initial direct relation matrix \({Z}^{k}\) comprises ratings denoted by \({Z}_{{ij}}^{k}\). Every direct relation matrix \({X}_{{ij}}^{k}\) comprises three sub-matrices L, M and U.

where \({Z}_{{ij}}^{k}=({L}_{{ij}}^{k}\,,\,{M}_{{ij}}^{k}\,,\,{U}_{{ij}}^{k})\), n = p

The combined average direct relation matrix for all respondents is obtained as follows:

\({\rm{where}}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{k=1}^{P}{Z}^{k}=\,\mathop{\sum}\limits_{k=1}^{P}{L}^{k},\,\mathop{\sum}\limits_{k=1}^{P}{M}^{k},\,\mathop{\sum}\limits_{k=1}^{P}{U}^{k}\).

Step 4: Normalizing the direct-relation fuzzy matrix

The largest values element in the initial direct relation matrix is obtained as

Thereafter each element of the average direct relation matrix is divided by (\({r}^{k}\)) to obtain the normalized direct relation fuzzy matrix as follows:

where \({X}_{{ij}}^{k}=\left({L}_{{ij}}^{k}\,,\,{M}_{{ij}}^{k}\,,\,{U}_{{ij}}^{k}\right)\,=\,\left(\frac{{Z}_{{ij}}^{k}}{{r}^{k}}\right)=\,\left(\frac{{L}_{{ij}}^{k}}{{r}^{k}}^{\prime} \frac{{M}_{{ij}}^{k}}{{r}^{k}}^{\prime} \frac{{U}_{{ij}}^{k}}{{r}^{k}}\right)\).

Step 5: Obtaining the fuzzy total relation matrix

To compute the fuzzy total relation matrix, \(\mathop{\mathrm{lim}}\limits_{w\to \infty }{X}^{w}\) must first be obtained. \({X}^{w}\) represents the triangular fuzzy matrix, which can be expressed as:

\({X}^{w}=\,\left[\begin{array}{cccc}0 & {x}_{12}^{w} & \cdots & {x}_{1n}^{w}\\ {x}_{21}^{w} & 0 & \cdots & {x}_{2n}^{w}\\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ {x}_{n1}^{w} & {x}_{n2}^{w} & \cdots & 0\end{array}\right]\), where \({x}_{{ij}}^{w}=\left({L}_{{ij}}^{w}\,,\,{M}_{{ij}}^{w}\,,\,{U}_{{ij}}^{w}\right)\) and

\({L}_{{ij}}^{w}=\left[\begin{array}{cccc}0 & {L}_{12}^{w} & \cdots & {L}_{1n}^{w}\\ {L}_{21}^{w} & 0 & \cdots & {L}_{2n}^{w}\\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ {L}_{n1}^{w} & {L}_{n2}^{w} & \cdots & 0\end{array}\right]\)’\(\,{M}_{{ij}}^{w}=\left[\begin{array}{cccc}0 & {M}_{12}^{w} & \cdots & {M}_{1n}^{w}\\ {M}_{21}^{w} & 0 & \cdots & {M}_{2n}^{w}\\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ {M}_{n1}^{w} & {M}_{n2}^{w} & \cdots & 0\end{array}\right]\) and \({U}_{{ij}}^{w}=\left[\begin{array}{cccc}0 & {U}_{12}^{w} & \cdots & {U}_{1n}^{w}\\ {U}_{21}^{w} & 0 & \cdots & {U}_{2n}^{w}\\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ {U}_{n1}^{w} & {U}_{n2}^{w} & \cdots & 0\end{array}\right]\)

These three matrices can be ordered as \({L}_{{ij}}^{w}=\,{X}_{L}^{w},\,{M}_{{ij}}^{w}={X}_{M}^{w},\,{U}_{U}^{w}={X}_{U}^{w}\). If \(\mathop{\mathrm{lim}}\limits_{w\to \infty }{X}^{w}\,\)= 0 and \(\mathop{\mathrm{lim}}\limits_{w\to \infty }{(1+X+X}^{2}+\ldots +{X}^{k})\) = \((1-{X)}^{-1}\) where 0 is the zero matrix and I is the identity matrix, the total relation matrix can be expressed as T =\(\,\mathop{\mathrm{lim}}\limits_{w\to \infty }{(X+X}^{2}+\ldots +{X}^{k})\) = \((1-{X)}^{-1}\). Because the \({X}^{w}\) matrix comprises matrices \({L}_{{ij}}^{w}\,,\,{M}_{{ij}}^{w}\,,\,{U}_{{ij}}^{w}\), the fuzzy total relation matrix for the three sub-matrices is obtained as:

Step 6: Obtaining the sum of rows and columns

The sums of rows and columns are plotted as vectors \({D}_{i}\) and \({R}_{i}\). Prominence, the x axis vector (\({D}_{i}+{R}_{i}\)), is obtained by summing the rows and columns for each factor at each of the three levels. Relation (\({D}_{i}-{R}_{i}\)), the y axis vector, is obtained by subtracting the columns from rows for each factor. The \({D}_{i}\) and \({R}_{i}\) values have three levels, (\({D}_{i}^{L}\), \({D}_{i}^{M}\), \({D}_{i}^{U}\,\) and \({R}_{i}^{L}\), \({R}_{i}^{M}\) and \({R}_{i}^{U}\)).

To obtain single values from triangular values, the mean of the triangular values is obtained, as follows:

The criteria are then classified into cause (\({D}_{i}+{R}_{i} > 0\)) and effect (\({D}_{i}+{R}_{i} < 0\)) groups. The causal model is obtained by graphing the values of \({D}_{i}+{R}_{i}\) and \({D}_{i}-{R}_{i}\).

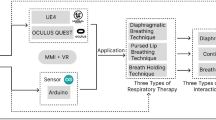

Figure 2 illustrates the research framework incorporating the M-Delphi and F-DEMATEL approach. The figure outlines the sequential methodology combining the M-Delphi method for expert consensus building and the Fuzzy DEMATEL approach for analyzing complex causal relationships.

Sampling

The F-DEMATEL method emphasizes collecting data from experts with knowledge and experience in the given field. As such, this study invited experts from Tzu Chi Foundation, a Taiwanese non-profit organization involved in health promotion. Individuals with more than 10 years’ experience in VR communication were invited. Eligible participants needed to have worked in VR communication for more than ten years. At the beginning of the survey, a screening question “have you ever used VR to spread altruistic content” was asked, and only those who responded “yes” were allowed to take part in the research. 20 participants took part in the study, and they were asked to rate the extent to which they believed the factors affected behavioral empathy using the semantic rating scale in Table S2 of the supplementary file. The participants were asked, “please rate, the extent to which each of the following items lead to behavioral empathy in virtual reality (N=No influence, VL=Very low influence, L=Low influence, HI=High influence, VH=Very high influence.” The participants were distinct from those invited in the M-Delphi study to enhance the validity of the collected data and to reduce bias which would have resulted had the data been collected from the same respondents twice.

F-DEMATEL results

The computation process of the F-DEMATEL is shown in the supplementary file. The initial direct relation fuzzy matrix (Table S3) was developed by computing the average of all direct relation matrices. Thereafter, the initial direct relation matrix (Table S4) was normalized by dividing its elements by the highest value of the sum of rows and columns for the initial direct relation matrix. Thereafter the fuzzy total relation matrix (Table S5) was computed by multiplying the normalized direct relation matrix by the inverse of the difference between the identity matrix and the normalized direct relation matrix. Then, the best non-fuzzy performance method was used to de-fuzzy the total relation matrix (Table S6). The cause-and-effect values (Table S7) were obtained by summing the rows and columns of the de-fuzzified matrix.

The results of the F-DEMATEL analysis indicated that all the factors were significant elements of the cause-and-effect system, given that their D + R values were all higher than the critical threshold of 0.195 (the mean of the de-fuzzified total relation matrix). Four factors were causal factors: focused immersion (D–R = 1.447), control (D–R = 1.291), focused attention (D–R = 1.027), heightened enjoyment (D–R = 0.933) and curiosity (D–R = 0.822). On the other hand, six effect factors were established: cognitive engagement (D–R = −1.183), emotional empathy (D–R = −1.183), cognitive empathy (D–R = −1.151), emotional engagement (D–R = −0.856), temporal dissociation (D–R = −0.589) and amusement (D–R = −0.558).

Discussion of F-DEMATEL results

The study finds that focused immersion, control, focused attention, heightened enjoyment, and curiosity are significant causal factors. These findings align with previous research, which showed that deep immersion in VR enhances concentration and internalization of content (Jeon et al., 2024; Zha et al., 2018), potentially triggering behavioral changes. When individuals perceive control over VR interactions, their sense of agency, presence, and engagement increase (Kang et al., 2021). This leads to better comprehension and internalization of VR content, enhancing the likelihood of acting in accordance with their VR experiences (Kang et al., 2021). Focused attention is also a significant causal factor, consistent with prior studies (Shin, 2018). Focused attention filters out distractions, enhances content internalization and shapes users’ behaviors. Enjoyment from immersive experiences also lead to positive behavioral outcomes, as it ensures continued engagement with VR and aids information internalization (Tsang, 2018). Additionally, curiosity is identified as a significant causal factor. It motivates exploration and learning, encouraging users to engage more deeply with VR content, leading to positive behavioral outcomes. The study also identifies six effect factors: cognitive engagement, emotional empathy, cognitive empathy, emotional engagement, temporal dissociation, and amusement. Cognitive engagement, emotional engagement, empathy and amusement, are influenced by temporal dissociation, focused immersion, heightened engagement, control, curiosity, and focused attention. Focused attention itself is shaped by temporal dissociation, focused immersion, heightened enjoyment, control, and curiosity. This supports that cognitive absorption in technology enhances engagement and empathy, particularly for prosocial topics (Pimentel & Kalyanaraman, 2024). Temporal dissociation is affected by all system factors. When users are engaged in VR, empathize with characters, maintain focused attention, and find content amusing, they experience temporal dissociation. This deepens their immersion, potentially leading to behavioral changes.

Study 2: structural equation modelling study

Measurement and sampling

The study adapted measurement instruments from existing studies (see Appendix) and collected data from individuals in Taiwan with VR usage experience, specifically those who had used VR to view altruism-inducing content. Items were translated into Mandarin Chinese using back-translation and validated through a pretest with 60 participants in ten rounds. Following the pretest, a pilot study with 200 participants refined the model. Data was collected using SurveyMonkey, an online data collection platform. It was analyzed using SmartPLS 3, and it satisfied all criteria for discriminant validity, convergent validity, reliability, and multicollinearity. The formal survey collected data from 1203 Taiwanese individuals who also had experience viewing altruism-inducing content in VR. To ensure that the participants indeed had experience viewing altruistic content in VR, they were asked to give brief explanations of the content that they had viewed. These explanations were evaluated by research assistants, and samples of participants whose experiences were deemed not to be altruism-inducing were excluded from the analysis. After excluding incomplete and irrelevant samples, 923 valid responses remained (632 females, 570 aged 18–25, 648 with a bachelor’s degree and 134 employed), reflecting a 76.73% validity rate.

Common method bias (CMB)

The prevention CMB, construct names were concealed, items were randomized, and participant identities were hidden (Podsakoff et al., 2003). In addition, Harman’s single factor test showed that the principal factor explained 20.448% of the variance, lower than the 50% threshold (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Therefore, CMB was not a problem in this study.

Results

Measurement model

The measurement model was analyzed using SmartPLS 3.0. Convergent validity was assessed through factor loadings and the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct. Factor loadings surpassed 0.7, and the AVE for every construct exceeded 0.5, indicating convergent validity (Hair Jr et al., 2014). Discriminant validity was evaluated based on Fornell and Larcker (1981) criterion as well as heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratios. According to Fornell and Larcker’s guideline, the square root of the AVE for each construct exceeded its correlation with any other construct. Additionally, HTMT ratios for all constructs remained below the 0.90 threshold (Hair Jr et al., 2014), affirming discriminant validity and demonstrating that the constructs were distinct. Moreover, the composite reliability of all constructs surpassed 0.7, confirming their internal consistency (Hair Jr et al., 2014). Detailed results can be found in Tables 1, 2 and S7 of the supplementary file.

Hypothesis testing

SmartPLS structural equation modelling with bootstrapping was used to test for the hypotheses. The results indicated significant positive effects of cognitive absorption on cognitive engagement (β = 0.633, p < 0.001), emotional engagement (β = 0.199, p < 0.001) and behavioral engagement (β = 0.100, p < 0.01). Thus, H1a, H1b and H1c were supported. The effect of cognitive engagement on cognitive empathy (β = 0.242, p < 0.001) and emotional empathy (β = 0.175, p < 0.001) were also significant, supporting H2a and H2b. Furthermore, the effect of emotional engagement on emotional empathy was significant (β = 0.579, p < 0.001), whereas the effect of emotional engagement on cognitive empathy (β = 0.005, p = 0.966) was not significant. Thus, H3a was supported, whereas H3b was not supported. The effects of cognitive empathy (β = 0.100, p < 0.01) and emotional empathy (β = 0.400, p < 0.001) on behavioral empathy were also significant, supporting H4 and H5.

The mediating effects were examined using the bootstrapping technique with 5000 samples in SmartPLS. The results showed that cognitive engagement and cognitive empathy serially mediated the effect of cognitive absorption on behavioral engagement (β = 0.012, p < 0.01, CI = [0.004, 0.020]), supporting H6a. The serial mediating effect of cognitive engagement and emotional empathy in the relationship between cognitive absorption and behavioral engagement was also significant (β = 0.044, p < 0.001, CI = [0.032, 0.059]), supporting H6b. However, the indirect effect of cognitive absorption on behavioral empathy through emotional engagement and cognitive empathy was also significant (β = 0.001, p = 0.970, CI = [−0.001, 0.001]). As such, H6c was not supported. The indirect effect of cognitive absorption on behavioral empathy through emotional engagement and emotional empathy was significant (β = 0.046, p < 0.001, CI = [0.029, 0.065]). Thus, H6d was supported. Moderation was also examined using bootstrapping with 5000 samples, with mean centering. Although the moderating effect of guilt on the effect of cognitive empathy on behavioral engagement was significant (β = −0.086, p < 0.001, CI = [−0.128, −0.043]), it was negative. Therefore, H7a was not supported. However, the moderating effect of guilt on the relationship between emotional empathy and behavioral engagement was significant and positive (β = 0.085, p < 0.001, CI = [0.042, 0.133]), supporting H7b. The SEM results are shown in Tables 3 and 4.

Artificial neural network (ANN)

Although PLS-SEM is robust against non-normal data, it is limited to capturing only linear relationships and is thus insufficient for modeling non-linear relationships. In contrast, ANN can handle both linear and non-linear models, making it suitable for ranking factors based on their significance. ANN operates by using interconnected artificial neurons that receive input, adjust their internal states (activations) based on the input (a process known as learning), and generate outputs accordingly (Leong, 2011). However, due to its “black box” nature, ANN is not ideal for hypothesis testing (Leong, 2011), as the internal processes and weight adjustments within the model are often opaque and difficult to interpret. This lack of transparency limits researchers’ ability to clearly trace causal relationships or derive theoretical insights, making ANN more suitable for prediction tasks than for explicating underlying mechanisms or validating conceptual frameworks. Figure 3 illustrates the ANN model utilized in this study. This figure presents the architecture of the developed ANN model, showing input, hidden, and output layers. Nodes represent processing units, and connecting lines denote weighted inputs. The model is used to predict outcomes based on trained datasets.

One output neuron (behavioral empathy) and multiple input neurons (cognitive absorption, cognitive engagement, emotional engagement, cognitive empathy, emotional empathy, guilt, focused attention, and amusement) were added. To improve model performance, the values of the input and output neurons were set within the range of 0 and 1. For the training and testing data, a tenfold cross-validation method was employed with a ratio of 70:30. To measure the goodness of fit of the ANN model, the root mean square errors were computed, yielding values of 0.144 for the training model and 0.164 for the testing model, resulting in an accuracy percentage of 83.6% for predicting behavioral empathy. The normalized importance values were calculated using sensitivity analysis, with relative importance divided by the highest value and presented as a percentage. As shown in Table 5, emotional empathy (100%) emerged as the most important predictor, followed by focused attention (77.9%), amusement (31.3%), cognitive empathy (21.5%), cognitive absorption (18.4%), and guilt (9.2%).

Discussion of SEM results

The SEM results confirmed that cognitive absorption significantly influenced engagement, empathy, and behavioral empathy through multiple direct, mediating, and moderating pathways. Specifically, the findings showed that cognitive absorption positively impacts cognitive and emotional engagement, consistent with prior research that cognitive absorption enhances mental activity and affective processing in technology use (Pimentel & Kalyanaraman, 2024). Immersed users focus entirely on the VR experience, improving mental involvement and cognitive function. Active user engagement leads to heightened cognitive activity and attention to altruistic content, enhancing emotional resonance and enjoyment. The study also confirms that cognitive engagement boosts cognitive and emotional empathy. Cognitive engagement facilitates mental activity and helps users understand the altruistic content and empathize with virtual characters, thereby improving both cognitive and emotional empathy (Pimentel & Kalyanaraman, 2024). These findings support that, compared to traditional media where engagement may remain passive or constrained by a lack of interactivity, VR’s immersive and interactive nature fosters deeper cognitive processing and sustained attention. This enables users to mentally simulate others’ experiences with greater clarity and vividness.

The study confirms that emotional engagement positively affects emotional empathy, supporting prior research that emotional engagement enhances resonance with emotional content (Lu et al., 2024). When individuals are emotionally engaged, they are more attuned to their own and others’ affective responses (Yang et al., 2023), making them more receptive to others’ emotional states. However, the effect of emotional engagement on cognitive empathy is not significant, indicating that emotional connection alone does not enhance understanding of others’ thoughts and perspectives. Emotional engagement aids in sharing emotions, but cognitive empathy requires skills like perspective-taking (Oh & Sundar, 2015). Thus, while emotional engagement boosts emotional connection, it does not automatically improve understanding of others’ mental states. This also explains why the serial mediating effect of emotional engagement and cognitive empathy is not significant. Although emotional engagement fosters affective resonance, it does not provide the cognitive resources necessary for perspective-taking or mentalizing, limiting its ability to channel emotional engagement into cognitive empathy (Oh & Sundar, 2015). Therefore, emotional engagement may follow an affective rather than cognitive pathway in shaping empathy-related outcomes. Importantly, VR’s ability to evoke stronger affective engagement than traditional text or video media lies in its multisensory stimulation and embodiment, which allows users to feel present within the scenario rather than remaining detached observers, thereby intensifying emotional empathy.

The results show that cognitive empathy, emotional empathy, and cognitive absorption positively affect behavioral empathy. These findings align with existing studies, which suggest that when individuals identify with the thoughts and feelings of those in need and are mentally absorbed in technology, they are more willing to help (Frost et al., 2022; Kandaurova & Lee, 2019; Han et al., 2024). Viewing altruistic content in VR allows users to interact with virtual characters representing various perspectives, enhancing their understanding of others’ thoughts and feelings. The realistic portrayal of emotions and immersive nature of VR environments can elicit stronger emotional responses, fostering empathy for others’ feelings and leading to observable behavioral changes, such as increased compassion and support. This effect is likely amplified in VR compared to traditional media, as VR’s experiential learning enables users to feel empathy for others through embodied simulations, which surpass the perspective-taking achieved through reading or passive viewing alone. Furthermore, cognitive absorption in VR enables users to engage in interactive simulations of real-world scenarios, directly experiencing different perspectives and emotions. This experiential learning process can translate into behavioral empathy as users apply their newfound understanding to real-world interactions.

The findings also confirm the serial mediating effects of cognitive engagement, cognitive empathy, emotional engagement, and emotional empathy in the relationship between cognitive absorption and behavioral empathy. Specifically, cognitive engagement and cognitive empathy sequentially mediate the effect of cognitive absorption and behavioral empathy. This relationship is also serially mediated by cognitive engagement and emotional empathy and emotional engagement and emotional empathy. This finding explains the sequential process through which cognitive absorption during virtual reality experiences shapes behavioral empathy. By fostering active engagement and deepening individuals, understanding of others’ perspectives, virtual reality technology has the potential to promote empathetic behaviors and contribute to more empathetic interactions among people. Unlike traditional media, which often rely on narrative or visual prompts to encourage empathy, VR’s active participation and first-person perspective uniquely position it to engage both cognitive and emotional empathy in an integrated manner. This can bridge the gap between understanding and feeling, further enhancing the behavioral outcomes.

The findings also indicate that guilt moderates the effect of emotional empathy on behavioral engagement, supporting prior research on the significance of guilt in shaping altruistic behaviors (Shipley & van Riper, 2022). When individuals experience guilt can heighten their sensitivity to others’ emotions and increase their motivation to alleviate their perceived distress. In this context, emotional empathy may act as a more potent driver of behavioral empathy, as individuals become more inclined to take action to mitigate their feelings of guilt by helping others. However, the moderating effect of guilt is not observed for the effect of cognitive empathy on behavioral empathy. This could be because cognitive empathy may operate through cognitive processes less sensitive to variations in emotional experiences such as guilt. Thus, cognitive empathy may exert its influence on behavioral empathy independent of mechanisms related to emotional elevation.

Theoretical implications

This study makes several contributions to the literature on virtual reality communication. First, it provides empirical evidence on how virtual reality can be leveraged to enhance altruistic communication. Previous research has not extensively examined how virtual reality can enhance communication within virtual environments (Leong, 2011; Reychav & Wu, 2015). Given that charity organizations across the globe are increasingly utilizing virtual reality to raise awareness about social issues and inspire charitable actions to address these issues, it is of paramount importance to develop an understanding of the mechanisms by which virtual reality can inspire helping behavior. The findings of this study indicate that cognitive absorption enhances behavioral empathy as it enhances cognitive engagement, cognitive empathy, emotional engagement, and emotional empathy. These, in turn, enhance behavioral empathy.

Secondly, drawing upon the cognitive absorption theory and the empathy-altruism theory, this research demonstrates the indirect effect of cognitive absorption through engagement and empathy in shaping VR-mediated altruistic communication. It shows that, triggered by cognitive absorption, engagement can shape empathy. Despite the prominence of cognitive absorption in VR and the primacy of empathy in altruism, extant research had not done much to examine the interplay of cognitive absorption, engagement and empathy in virtual reality-mediated altruistic communication. Noteworthy is the finding that cognitive engagement affects emotional empathy, whereas emotional empathy does not significantly impact cognitive engagement. This finding supports prior research, which found that cognitive perceptions of stimuli affect emotional responses, which in turn shape behavioral responses (Pachankis, 2007).

Thirdly, this study shows the important role of guilt in shaping altruism driven by motivators from virtual environments. Prior research had largely examined the role of guilt in shaping helping behavior in offline contexts, where individuals come into direct contact with the situations arousing their altruistic behaviors (De Luca et al., 2016; Shipley & van Riper, 2022). This study demonstrates that although virtual environments often reduce accountability due to the emphasis on user anonymity, the content users encounter can evoke feelings of guilt, enhancing their behavioral empathy, particularly for those who experience emotional empathy. The findings also indicate that while users experiencing cognitive empathy may feel guilt, they are less likely to engage in altruistic behaviors than those experiencing emotional empathy.

Practical implications

This study provides several practical implications for practitioners in virtual reality communication. Non-profit organizations are often faced with challenges to promote the involvement of well-wishers in the social issues they advance. This study shows that on top of the usual media used by non-profit organizations to create an understanding of social issues, such as television, radio, social media, and posters, virtual reality is a powerful tool for educating people about altruism and stimulating behavioral action to alleviate the societal problems that they aim to alleviate. The findings also highlight the importance of engagement in ensuring the effectiveness of virtual reality communication. Engagement can enhance empathy, which is crucial for ensuring the success of altruism. Consequently, managers should create virtual reality experiences specifically designed to engage users both cognitively and emotionally. The findings indicate that cognitive absorption can boost user engagement in virtual reality. Therefore, virtual reality practitioners can implement strategies to enhance cognitive absorption, ensuring that users remain engaged throughout the virtual reality experience.

Although this research was conducted in the altruism context, its findings also provide valuable insights for implementing VR in other contexts such as educational and therapeutic settings, where altruism is increasingly being emphasised (Jeon et al., 2024; Bolinski et al., 2021). In education, VR offers a unique opportunity to foster empathy, social responsibility, and prosocial behavior by immersing students in emotionally and cognitively engaging simulations. Our findings suggest that, unlike traditional media, VR can enable students to actively experience others’ perspectives, such as historical figures, marginalized communities, or ethical dilemmas. This can enhance both cognitive and emotional empathy, which can drive behavioral change. Educators can design VR modules that stimulate focused attention, curiosity, and enjoyment to maximize engagement and encourage students to apply learned empathy in real-world actions, such as collaborative projects or community service. Additionally, the study’s finding that guilt amplifies the impact of emotional empathy on behavior suggests that carefully crafted VR scenarios portraying moral dilemmas may ethically harness mild feelings of guilt to motivate social action, though this must be balanced to avoid emotional overload.

In therapeutic contexts, VR can be a powerful tool for enhancing emotional and cognitive empathy in clients facing social, emotional, or behavioral challenges. Therapists can use immersive VR scenarios to help clients practice perspective-taking, emotional regulation, or reparative actions, especially in treatments for problems such as social anxiety or moral injury. By designing interactive and emotionally resonant VR experiences that promote cognitive absorption, therapists can strengthen clients’ capacity for empathy-driven behavioral change. Moreover, the ranking of predictors from the ANN analysis highlights emotional empathy, focused attention, and amusement as key drivers of behavioral empathy. This offers concrete design priorities for both educational and therapeutic VR applications. Practitioners should emphasize creating emotionally compelling, interactive, and curiosity-driven environments to ensure that VR interventions in such settings produce meaningful and sustained empathetic outcomes.

Limitations and directions for future research

This research has several limitations. First, it relied on cross-sectional data, thus it could not examine how behavioral empathy develops over time after exposure to VR content. In addition, prior research has argued that cross-sectional data can entail compromised centrality hypotheses, and results from such studies should be considered with cautiously (Veneziani et al., 2024). Future research should therefore consider examining this model using longitudinal approaches.

Secondly, this research’s Delphi and F-DEMATEL methods relied on data collected from individuals working for the same organization. This was so due to this organization’s prominence in altruistic communication in Taiwan, where the study was conducted. However, this could potentially increase homogeneity in the views of the respondents due to common positions, goals and organisational culture. This study attempted to reduce these biases by ensuring the anonymity of the participants. Future research could address this potential bias further by using data collected from experts working in different organizations.

Another limitation is the use of a large and complex model integrating multiple constructs and pathways. While this comprehensive approach allowed for a detailed examination of the mechanisms driving behavioral empathy, testing a large model increases the risk of overfitting and may reduce the generalizability of the findings (Bentler & Chou, 1987). Future research should consider testing more parsimonious models or using cross-validation techniques across different samples to confirm the robustness and stability of the observed relationships.

Fourth, this study used self-reported items to measure the constructs of the study. However, self-reported measures are susceptible to social desirability bias, potentially limiting the reliability of the results. Future studies could therefore use observational techniques to ensure more accurate measurement of the variables of interest. Another limitation concerns the use of structural equation modeling (SEM), which, while powerful for testing hypothesized relationships among variables, remains fundamentally correlational and cannot establish causality (Antonakis, et al., 2010; Bollen & Pearl, 2013). Although the proposed model was theoretically grounded and supported by prior empirical work, the observed associations between cognitive absorption, engagement, empathy, guilt, and behavioral empathy should be interpreted with caution, as SEM cannot definitively determine directional or causal effects. Future research could strengthen causal inferences by incorporating longitudinal or experimental designs, which would allow for clearer identification of temporal and causal pathways among these constructs. Finally, the data was collected from respondents based in one country, which is Taiwan. This could potentially limit the generalizability of findings, as technology usage dynamics differ depending on context. Future research could therefore examine the model using data collected from other contexts.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed in this study have been incorporatedinto both the manuscript and the supplementary files.

References

Abramson L, Uzefovsky F, Toccaceli V, Knafo-Noam A (2020) The genetic and environmental origins of emotional and cognitive empathy: review and meta-analyses of twin studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 114:113–133

Airagnes G, Du Vaure CB, Galam E, Bunge L, Hoertel N, Limosin F, Jaury P, Lemogne C (2021) Personality traits are associated with cognitive empathy in medical students but not with its evolution and interventions to improve it. J Psychosom Res 144:110410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110410

Anthony WL, Zhu Y, Nower L (2021) The relationship of interactive technology use for entertainment and school performance and engagement: Evidence from a longitudinal study in a nationally representative sample of middle school students in China. Comput Hum Behav 122:106846. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106846

Antonakis J, Bendahan S, Jacquart P, Lalive R (2010) On making causal claims: a review and recommendations. Leadersh Q 21(6):1086–1120

Balakrishnan J, Dwivedi YK (2021) Role of cognitive absorption in building user trust and experience. Psychol Market 38(4):643–668

Batson CD, Batson JG, Slingsby JK, Harrell KL, Peekna HM, Todd RM (1991) Empathic joy and the empathy-altruism hypothesis. J Personal Soc Psychol 61(3):413–426

Bentler PM, Chou CP (1987) Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociol Methods Res 16(1):78–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124187016001004

Bolinski F, Etzelmüller A, De Witte NAJ, van Beurden C, Debard G, Bonroy B, Cuijpers P, Riper H, Kleiboer A (2021) Physiological and self-reported arousal in virtual reality versus face-to-face emotional activation and cognitive restructuring in university students: a crossover experimental study using wearable monitoring. Behav Res Ther, 142:103877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2021.103877

Bollen KA, Pearl J (2013) Eight myths about causality and structural equation models. In Handbook of Causal Analysis for Social Research (pp. 301–328). Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands

Cummins RG, Cui B (2014) Reconceptualizing address in television programming: the effect of address and affective empathy on viewer experience of parasocial interaction. J Commun 64(4):723–742

Davis MH, Hull JG, Young RD, Warren GG (1987) Emotional reactions to dramatic film stimuli: the influence of cognitive and emotional empathy. J Personal Soc Psychol 52(1):126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.52.1.126

De Luca R, Ferreira M, Botelho D (2016) When guilt induces charity: the emotional side of philanthropy. Eur J Bus Soc Sci 5(02):44–58

Decety J, Holvoet C (2021) The emergence of empathy: a developmental neuroscience perspective. Dev Rev 62:100999. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2021.100999

Decety J, Michalska KJ (2020) Chapter 22—a developmental neuroscience perspective on empathy. In J Rubenstein, P Rakic, B Chen, & KY Kwan (Eds.), Neural Circuit and Cognitive Development (Second Edition) (pp. 485–503). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-814411-4.00022-6

Di Fabio A, Kenny ME (2021) Connectedness to nature, personality traits and empathy from a sustainability perspective. Curr Psychol 40(3):1095–1106

Han J, Cores-Sarría L, Zhou H (2024) In-person, video conference, or audio conference? Examining individual and dyadic information processing as a function of communication systems. J Commun 74(2):117–129

Hair Jr J, Sarstedt M, Hopkins L, Kuppelwieser VG (2014) Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): an emerging tool in business research. Eur Bus Rev 26(2):106–121

Herrera D, Retamal-Valdes B, Alonso B, Feres M (2018) Acute periodontal lesions (periodontal abscesses andnecrotizing periodontal diseases) and endo-periodontal lesions. J Periodontol 89(Suppl 1):S85–S102. https://doi.org/10.1002/JPER.16-0642

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J Mark Res (JMR) 18(1):39–50

Frost S, Kannis-Dymand L, Schaffer V, Millear P, Allen A, Stallman H, Mason J, Wood A, Atkinson-Nolte J (2022) Virtual immersion in nature and psychological well-being: a systematic literature review. J Environ Psychol 80:101765. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2022.101765

Jayaraman S (2024) 90+ powerful virtual reality statistics to know in 2024. Retrieved from https://www.g2.com/articles/virtual-reality-statistics. Accessed February 20, 2024

Jeon H, Jun Y, Laine TH, Kim E (2024) Immersive virtual reality game for cognitive-empathy education: Implementation and formative evaluation. Educ Inf Technol 29(2):1559–1590

Jennett C, Cox AL, Cairns P, Dhoparee S, Epps A, Tijs T, Walton A (2008) Measuring and defining the experience ofimmersion in games. Int J Hum Comput Stud 66(9):641–661. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2008.04.004

Jumaan IA, Hashim NH, Al-Ghazali BM (2020) The role of cognitive absorption in predicting mobile internet users’ continuance intention: an extension of the expectation-confirmation model. Technol Soc 63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101355

Kandaurova M, Lee SH (Mark) (2019) The effects of Virtual Reality (VR) on charitable giving: the role of empathy, guilt, responsibility, and social exclusion. J Bus Res 100:571–580

Kang S, Dove S, Ebright H, Morales S, Kim H (2021) Does virtual reality affect behavioral intention? Testing engagement processes in a K-Pop video on YouTube. Comput Hum Behav 123:106875. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106875

Kealy D, McCloskey KD, Cox DW, Ogrodniczuk JS, Joyce AS (2019) Getting absorbed in group therapy: absorption and cohesion in integrative group treatment. Counsell Psychother Res 19(3):286–293

Lee YH, Chen M, Guo J, Xu Q (2023) Moral balancing in video games: the moderating role of issue congruency. Commun Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/00936502231195106

Léger P-M, Davis FD, Cronan TP, Perret J (2014) Neurophysiological correlates of cognitive absorption in an enactive training context. Comput Hum Behav 34:273–283

Leong P (2011) Role of social presence and cognitive absorption in online learning environments. Distance Educ 32(1):5–28

Liao, C-H (2020) Evaluating the social marketing success criteria in health promotion: a F-DEMATEL approach. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17:6317. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176317

Lu AS, Green MC, Alon D (2024) The effect of animated Sci-Fi characters’ racial presentation on narrative engagement, wishful identification, and physical activity intention among children. J Commun 74(2):160–172

Lunardo R, Ponsignon F (2020) Achieving immersion in the tourism experience: the role of autonomy, temporal dissociation, and reactance. J Travel Res 59(7):1151–1167

Morgan B, Fowers B (2022) Empathy and authenticity online: the roles of moral identity, moral disengagement, and parenting style. J Personal 90(2):183–202

Oh J, Sundar SS (2015) How does interactivity persuade? An experimental test of interactivity on cognitive absorption, elaboration, and attitudes. J Commun 65(2):213–236

Pachankis JE (2007) The psychological implications of concealing a stigma: a cognitive-affective-behavioral model. Psychol Bull 133(2):328–345

Paradiso E, Gazzola V, Keysers C (2021) Neural mechanisms necessary for empathy-related phenomena across species. Curr Opin Neurobiol 68:107–115

Paul SK, Chowdhury P, Moktadir MA, Lau KH (2021) Supply chain recovery challenges in the wake of COVID-19 pandemic. J Bus Res 136:316–329

Pimentel D, Kalyanaraman S (2024) How cognitive absorption influences responses to immersive narratives of environmental threats. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 27(1):83–90

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88(5):879–903

Reychav I, Wu D (2015) Are your users actively involved? A cognitive absorption perspective in mobile training. Comput Hum Behav 44:335–346

Saadé R, Bahli B (2005) The impact of cognitive absorption on perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use in on-line learning: an extension of the technology acceptance model. Inf Manag 42(2):317–327

Shieh J-I, Wu H-H, Huang K-K (2010) A DEMATEL method in identifying key success factors of hospital service quality. Knowl-Based Syst 23(3):277–282

Shin D (2018) Empathy and embodied experience in virtual environment: to what extent can virtual reality stimulate empathy and embodied experience? Comput Hum Behav 78:64–73

Shin D (2019) How do users experience the interaction with an immersive screen? Comput Hum Behav 98:302–310

Shipley NJ, van Riper CJ (2022) Pride and guilt predict pro-environmental behavior: a meta-analysis of correlational and experimental evidence. J Environ Psychol 79:101753. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101753

Skarbez R, Brooks Jr FP, Whitton MC (2017) A survey of presence and related concepts. ACM Comput Surv 50(6):1–39

Slater M, Sanchez-Vives MV (2016) Enhancing Our Lives with Immersive Virtual Reality. Front Robot AI 3:74. https://doi.org/10.3389/frobt.2016.00074

Spinrad TL, Gal DE (2018) Fostering prosocial behavior and empathy in young children. Curr Opin Psychol 20:40–44

Talukdar N, Yu S (2021) Breaking the psychological distance: the effect of immersive virtual reality on perceived novelty and user satisfaction. J Strateg Market, https://doi.org/10.1080/0965254X.2021.1967428

Tangney JP, Dearing RL (2002) Shame and guilt. New York: Guilford Press. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412950664.n388

Tsang SJ (2018) Empathy and the hostile media phenomenon. J Commun 68(4):809–829

UNICEF (2023) Augmented Reality/Virtual Reality for Good | UNICEF Office of Innovation. Retrieved from https://www.unicef.org/innovation/XR. Accessed March 18, 2024

Veneziani G, Ciacchella C, Onorati P, Lai C (2024) Attachment theory 2.0: a network analysis of offline and online attachment dimensions, guilt, shame, and self-esteem and their differences between low and high internet users. Comput Hum Behav 156:108195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2024.108195

Ventura S, Badenes-Ribera L, Herrero R, Cebolla A, Galiana L, Baños R (2020) Virtual reality as a medium to elicit empathy: a meta-analysis. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 23(10):667–676

Yang C (2016) Instagram use, loneliness, and social comparison orientation: Interact and browse on social media, but don’t compare. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 19(12):703–708

Yang H, Cai M, Diao Y, Liu R, Liu L, Xiang Q (2023) How does interactive virtual reality enhance learning outcomes via emotional experiences? A structural equation modeling approach. Front Psychol 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1081372

Yoo S-C, Drumwright M (2018) Nonprofit fundraising with virtual reality. Nonprofit Manag Leadersh 29(1):11–27

Zha X, Yang H, Yan Y, Liu K, Huang C (2018) Exploring the effect of social media inform ation quality, source credibility and reputation on informational fit-to-task: moderating role of focused immersion. Comput Hum Behav 79:227–237

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CH-L wrote the main manuscript text and prepared all figures and tables.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval

In the announcement letter dated March 22, 2012 (Ref: MOHW Medical Letter No. 1010064538), the Ministry of Health and Welfare (Taiwan) provided a clarification regarding the “Human Research Act,” Article 4. It was stated that this article does not encompass “Social Behavioral Science research” (i.e., research on the interaction between individuals and the external social environment due to mutual influences between individuals) and “humanities research” (i.e., research that observes, analyzes, and critiques social phenomena and cultural arts). The research is characterized as non-human contact, non-anonymous, and non-intrusive, conducted in a public setting. This research unambiguously falls within the purview of these two exempted categories and may not necessitate ethics approval for research review.

Informed consent

In the announcement letter dated July 5, 2012 (Ref: MOHW Medical Letter No. 1010265083), the Ministry of Health and Welfare (Taiwan) stipulated that under specific conditions, the consent of the research subject may be exempted as follows: No. 3 The research presents minimal risk, with potential risks to the research subject not surpassing those of non-participants in the study, and the waiver of prior consent does not impinge upon the rights and interests of the research subject. This study aligns with and satisfies the specified conditions.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liao, CH. The role of virtual reality in enhancing behavioral empathy: exploring cognitive absorption, engagement, and emotional moderation using multivariate methods. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 995 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05334-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record: