Abstract

Project-based learning (PBL) as an instructional method has been adopted across various academic disciplines, including foreign language education. While existing research has demonstrated the significant efficacy of PBL in enhancing students’ foreign language acquisition, investigations into its implementation and effectiveness within rural education settings remain notably scarce. This study adopted a mixed method design to conduct an 8-week pedagogical intervention, analyzing the effectiveness of PBL on EFL learners’ learning motivation and academic performance in a Chinese rural junior middle school. The quantitative results showed that the projected-based language learning (PBLL) enhanced EFL learners’ learning motivation, whereas its impact on academic achievement tests yielded limited effects. The qualitative data indicated that EFL learners showed greater interest in PBLL instruction. The findings suggest that PBLL can serve as an effective pedagogical approach to enhance rural EFL learners’ learning motivation, contextual writing skills, and alignment between instruction and standardized assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Learning motivation is universally recognized by educators and researchers as a pivotal element that impacts the pace and achievement in second and foreign language learning (Dörnyei, 1998; Renandya, 2013). Students with higher levels of Learning motivation are generally more capable of overcoming unfavorable learning conditions and achieving better academic outcomes (Lasagabaster, 2011), whereas low learning motivation may result in stagnant or even declining academic performance (Cabanillas, 2023).

However, in rural areas, EFL learners tend to exhibit generally low levels of learning motivation (Li, 2022; Castañeda and Jackeline, 2014). Rural students often encounter challenges such as monotonous instructional methods, and a disconnect between learning content and real-life experiences, all of which gradually diminish their interest and learning motivation in English learning (Zheng, 2022). The weakening of students’ learning motivation often leads to disengagement from learning tasks, which in turn negatively affects their academic outcomes, especially in exam-oriented contexts (Ozer and Badem, 2022).

In response to rural students’ lack of learning motivation and poor academic achievement, project-based language learning (PBLL) has gained increasing attention as an innovative instructional approach to the integrated acquisition of language, content, and skills (Yang and Diao). Prior studies have demonstrated PBLL’s positive effects on improving EFL learners’ learning motivation (Li, 2022; Park and Lee, 2019), language proficiency (Yang and Ding, 2023), and core competencies (Ma, 2025), with notable advantages in fostering communicative language abilities.

Nevertheless, existing research predominantly focuses on urban or resource-rich educational settings (Li, 2022; Shafaei and Rahim, 2015) with limited attention to under-resourced rural contexts, which may potentially further widen the educational gap between urban and rural areas. In addition, in terms of research participants, most studies were conducted at tertiary level (Ye et al. 2019; Amorati and Hajek, 2021; Shin, 2018; Zheng et al. 2022), followed by high school learners (Ma, 2025; Yuliani and Lengkanawati, 2017). By contrast, research on junior secondary learners remains limited (Astawa et al. 2017; Artini et al. 2018), and empirical investigations into the implementation of PBLL in rural junior middle schools are particularly scarce.

In an exam-driven English learning environment, traditional teaching methods focus heavily on fragmented language knowledge, which hinders the development of comprehensive language skills. The new educational reform in China calls for enhancing students’ core English literacy by balancing the learning of language form and function, which is especially crucial in resource-poor rural areas, where the traditional exam-oriented model remains dominant, neglecting the cultivation of comprehensive language abilities. Moreover, due to constraints in teacher competence and technological resources, implementing PBLL in rural schools presents greater challenges compared to urban settings (Zhang and Su, 2021). Hence, effectively implementing PBLL in rural areas, remains a significant challenge in English education. Therefore, exploring and validating the effectiveness of PBLL in rural middle school English teaching is of considerable educational and practical value.

Literature review

Project-based learning

Project-based learning (PBL) is a student-centered instructional approach that is problem-driven and grounded in authentic contexts, aiming to cultivate students’ core competencies and enhance their diverse capabilities (Zhang and Su, 2021; Krajcik and Blumenfeld, 2005). Rooted in John Dewey’s “learning by doing” philosophy, PBL emphasizes that learners acquire knowledge through meaningful activities rather than passively receiving information. The theoretical foundation of PBL lies in social constructivism, which posits that knowledge is actively constructed through learners’ interactions with peers, instructors, and the surrounding environment (Vygotsky, 1978). Within this framework, learning is viewed as a dynamic social process in which students deepen their conceptual understanding through collaboration, inquiry, and practical application.

Additionally, PBL draws on situated learning theory, which asserts that meaningful learning occurs in authentic contexts (Lave and Wenger, 1991), and is further informed by the theory of cognitive tools, which highlights the importance of external scaffolding instruction in fostering deeper cognitive engagement and problem-solving skills development (Jonassen and Rohrer-Murphy, 1999). Hence, PBL integrates the principles of authentic problem-solving, knowledge construction, social interaction, cognitive tool support, and outcome orientation. It not only enriches students’ academic learning but also promotes the development of essential skills needed to navigate both school and life beyond the classroom (Larmer and Mergendoller, 2015).

Although there is no precise definition of PBL and clear instruction on how to conduct PBL in the classroom, scholars do share similar visions on the design principles and instructional suggestions (Thomas, 2000; Larmer and Mergendoller, 2015; Thomas (2000) identified five hallmark features of PBL, such as centrality, driving question, constructive inquiry, student autonomy, and authenticity. Similarly, Krajcik and Blumenfeld (2005) proposed five essential design elements: a driving question, exploration of the question through expert performances, collaborative activities, scaffolding learning tasks, and the creation of tangible artifacts. Other researchers also have contributed to refining PBL design by emphasizing sustained inquiry (Larmer and Mergendoller, 2015), interdisciplinary integration (Cabanillas, 2023), and critical reflection to ensure high-quality, practice-oriented implementation.

These contributions serve to bridge the gap between theory and classroom practice, providing clearer guidance for effective teaching and learning. Furthermore, the Buck Institute for PBL has developed a set of Gold Standard criteria to support high-quality implementation, aimed at enhancing students’ acquisition of key knowledge, conceptual understanding, and future-ready success skills.

PBLL and language learners’ learning motivation

PBLL is an instructional approach that applies the principles of PBL to language education (Yang and Diao, 2024). A growing body of empirical research has systematically evaluated the learners’ learning motivations with PBLL instruction. Landron et al. (2018) investigated the impact of PBLL on gifted students in second language learning. By implementing both authenticity-driven interdisciplinary projects and student-designed thematic projects, the study found significant improvements in middle school students’ learning motivation and Spanish language proficiency. In addition, Amorati and Hajek (2021) employed a mixed-methods approach to explore how a product-oriented PBLL task impacted university students’ learning motivation in Italian language learning. The research findings indicated that despite challenges such as time management and creative ideation, students’ intrinsic motivation increased significantly.

In the English as a foreign language (EFL) context, research has primarily focused on changes in learning motivation. While findings generally support PBLL’s positive effect on student engagement and learning motivation, results remain mixed.

On one hand, numerous studies reported that PBLL enhances EFL learners’ learning motivation. Aubrey (2022), using a multi-case study, analyzed three university students’ learning trajectories in a PBLL task. Through a multimodal evaluation, PBLL was found to boost learner engagement and foster proactive communication. The integration of public presentations for international audiences reinforced students’ intrinsic motivation. Similarly, Zheng et al. (2022) conducted a longitudinal case study with five college students and revealed dynamic engagement patterns and motivational mechanisms in collaborative PBLL writing tasks. Li (2022) found that problem-driven PBLL effectively stimulated middle school students’ interest in English. Furthermore, Shin (2018) adopted a quasi-experimental design to examine the impact of technology-integrated PBLL on 79 South Korean university students’ English learning motivation and self-efficacy. Grounded in Keller’s ARCS model, the study showed that the PBLL approach significantly improved learners’ learning motivation as measured by a modified self-efficacy scale.

On the other hand, some studies found that PBLL did not significantly enhance EFL learners’ learning motivation. Cabanillas (2023), in a quasi-experimental study on interdisciplinary PBLL with fifth-grade students, reported no significant motivational differences between experimental and CG. The researcher stated that learning adaptation, uneven English proficiency, and group dynamics may have limited PBLL’s effectiveness in this context.

PBLL and language learners’ academic performance

Despite the ongoing debates regarding PBLL’s motivational outcomes in EFL teaching, substantial research supports its effectiveness in improving students’ language skills, particularly in speaking, writing, and integrated language use.

In terms of oral proficiency, Cabanillas (2023) noted that interdisciplinary PBLL provided rich opportunities for interaction and authentic communication, leading to significant gains in EFL learners’ speaking abilities. A quasi-experimental study by Astawa et al. (2017) echoed these findings: Indonesian middle school students participating in PBLL tasks showed significant improvements in both speaking (monologues and dialogs) and writing skills. Regarding vocabulary and foundational language skills, Shafaei and Rahim (2015) found that Iranian high school EFL learners in a PBLL group significantly outperformed those in a traditional instruction group in vocabulary retention and mastery of complex terms. Zhao (2024), applying technology-enhanced PBLL in postgraduate English courses, reported simultaneous improvement in language use and technological literacy. Virtual environments and data interaction further strengthened knowledge transfer. Similarly, recent findings by Benlaghrissi and Meriem (2024) demonstrated that integrating MALL with PBL significantly enhanced EFL learners’ speaking proficiency, highlighting the pedagogical potential of mobile-assisted PBLL instruction.

PBLL has also shown promise in enhancing writing skills and English core competencies. Ye et al. (2019) demonstrated that project-based academic writing activities improved college students’ logical expression and international communication, aligning motivation with career aspirations. Ma (2025) conducted a case study showing how PBLL’s “inquiry–presentation” process addressed the mechanical nature of traditional writing instruction, enabling senior high students to produce autonomous thematic writing and develop core competencies. Andargie et al. (2025) found that PBLL significantly improved EFL undergraduate students’ writing performance and highlighted PBLL’s role in enhancing idea generation, organization, and collaboration through real-world tasks.

The current research suggests that PBLL enhances learners’ learning motivation through authentic tasks, collaborative inquiry, and public presentations (Aubrey, 2022; Zheng, 2022). However, Cabanillas (2023) indicated that PBLL does not universally improve their learning motivation, highlighting the influence of learner characteristics, learning environments, and implementation fidelity. Moreover, while PBLL is widely recognized for advancing speaking, writing, and integrated language skills (Astawa et al. 2017; Shafaei and Rahim, 2015; Artini et al. 2018), most studies focus on urban schools or higher education contexts (Andargie et al. 2025). The academic performance of rural students remains understudied. Although PBLL varies in form, such as task-based, technology-enhanced, and interdisciplinary PBL, existing research has not sufficiently demonstrated differences in learning outcomes across types. Some studies (Holmes and Hwang, 2016; Tomaszewski et al. 2020) argued that the effectiveness of PBLL depends more on teacher facilitation learner autonomy, and technological support. Thus, whether PBLL can effectively improve learning motivation and academic achievement in under-resourced rural schools still requires systematic investigation.

PBLL in EFL rural area

Existing research on PBLL in rural EFL contexts primarily focuses on the effectiveness of EFL rural learners’ learning outcomes and the challenges associated with its implementation, along with corresponding coping strategies.

Studies have shown that PBLL, through contextualized tasks and authentic language use, can effectively enhance rural students’ vocabulary acquisition, oral expression, and intercultural competence. For instance, in a case study conducted in rural Colombia, Castañeda and Jackeline (2014) found that 17 eighth-grade EFL learners who participated in a culturally themed mini-PBLL project demonstrated improved vocabulary retention and teacher-student interaction, although no significant improvement was observed in grammatical accuracy. The study suggested that the contextual nature of PBLL tasks reduced learners’ language anxiety and boosted their learning motivation, highlighting the need to balance fluency and accuracy in oral production. Similarly, Samaranayake (2016) reported that “micro-projects,” such as market role-plays, enhanced classroom interaction in rural Sri Lanka, providing students with more opportunities for autonomous questioning and authentic communication, which in turn improved their speaking skills.

However, implementing PBLL in rural areas also presents notable challenges. Santhi et al. (2019) investigated a technology-enhanced PBLL initiative involving 35 Indonesian high school students who created YouTube video projects. While most students felt the project fostered creativity and increased their confidence in language use, many also reported difficulties due to limited access to digital devices. Furthermore, teacher facilitation and classroom interaction patterns remain significant obstacles in PBLL implementation. In a quasi-experimental study, Carrabba and Farmer (2018) found that students in the PBLL group exhibited higher learning motivation and more frequent teacher-student interactions. However, only a small proportion of learners produced higher-order thinking questions. The researchers argued that while open-ended PBLL tasks encouraged participation, the lack of teacher-initiated, inquiry-based questioning hindered the development of higher-order thinking skills.

In addition, several studies underscored the need to consider cultural factors when implementing PBLL in rural areas. Zheng (2022) found that a culturally responsive PBLL design, such as English-language guided tours of the Dragon Boat Festival, helped improve students’ collaborative and reflective abilities. However, many students were reluctant to publicly present their project outcomes. The study recommended adopting low-risk presentation formats (e.g., in-class sharing sessions) to alleviate students’ anxiety to increase student engagement and cultural identity.

To sum, existing studies on PBLL in rural contexts have provided initial insights into its effects on language learning outcomes, technological integration, classroom interaction, and cultural relevance. Nonetheless, several research gaps remain.

First, while PBLL appears to enhance students’ interest in learning, its specific impact on academic performance has not been thoroughly validated. Second, under conditions of limited resources and insufficient teacher training in PBLL, it is still unclear how to optimize its implementation to effectively improve student learning motivation. Therefore, the present study aims to examine the practical application of English PBLL in rural areas, with a particular focus on:

RQ1: Can PBL as an innovative instruction improve EFL learners’ learning motivation in a rural middle school?

RQ2: Can PBL improve EFL learners’ academic performance in a rural middle school?

Methods

Participants

This study was conducted in a rural boarding middle school in W City, Hainan Province, involving two intact seventh-grade classes. The students, aged 13 to 14, were randomly assigned by class to one of two conditions to avoid disruption to existing instructional arrangements: the experimental group (EG) (n = 45) and the CG (n = 47). The two classes are comparable in terms of age (t (90) = −0.958, p = 0.341) or gender (χ2 (1) = 0.027, p = 0.670). In the most recent district-wide English examination, students in both classes scored an average of around 50 out of a total of 120, while the overall English average for their grade level ranked the lowest in the entire district.

All participants were enrolled in a compulsory English course lasting 20 weeks, with six 45 min lessons per week. Both classes were taught by the same teacher (Teacher Z). Each classroom was equipped with a Seewo interactive whiteboard. However, students had no access to personal digital learning devices. As the school operated under a full boarding system and most students were left-behind children whose parents worked away from home, access to out-of-class English learning support was extremely limited. As a result, students’ English learning was highly dependent on classroom instruction (Appendix 1).

In the current study, the instructional content was the same for both EG and CG (Modules 1 and 2). The difference was the instructional approach. The CG followed a traditional lecture-based, teacher-centered method, with a primary focus on the acquisition of language forms. In contrast, the EG experienced the PBLL approach with an aim to accomplish two projects. Since EFL learners in EG have never experienced PBLL, direct instruction was also incorporated to support students’ language learning and understanding of the project tasks. However, this direct instruction was context-embedded and driven by real-world problem-solving needs, rather than being isolated from authentic communicative situations as in traditional didactic teaching.

Instruments

Academic performance test

In this study, academic performance refers to students’ learning outcomes, including linguistic knowledge learning and thematic writing. Academic achievement was assessed through standardized test scores, consisting of a pre-test and a post-test, each with a total score of 120 points. Of these, 105 points were allocated to basic language knowledge and 15 points to thematic writing.

The test was designed in alignment with the English Curriculum Standards for Compulsory Education (2022) and with reference to the regional standardized English examination requirements for junior secondary schools. It consisted of two main sections: (1) objective items, including tasks on writing the correct form of the uppercase and lowercase forms of the 26 letters, multiple-choice questions on phonics, vocabulary, and grammar, as well as sentence completion tasks; and (2) a subjective item, which was a thematic situational writing task. The evaluation for the objective part of the test is straightforward, with each question being scored as correct or incorrect. While the evaluation for the subjective part is more nuanced and is based on the following aspects: content, grammar, syntax and word count.

First, EFL teachers from Grade 8 design the test including the test format, content, and evaluation criteria based on curriculum standards and district-level examination requirements. Recognizing that test difficulty may impact students’ standardized scores, this study applied the Classical Test Theory to assess the difficulty levels of both groups. The results revealed that the difficulty index of the pre-test was 0.50, while the post-test had a difficulty index of 0.48, indicating a comparable level of difficulty between the two tests and ensuring measurement consistency (Spearman, 1987).

The sealed pre-test and post-test papers were graded by two eighth-grade English teachers. The grading process was supported by two trained research assistants, who were responsible for recording, organizing, and supervising the scores. In cases of significant discrepancies in scoring, the research assistants promptly provided feedback to the graders and the head of the teaching research group for re-evaluation, ensuring the accuracy of the scores. Furthermore, the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) was employed to assess the consistency of the grading between the two raters. The ICC values for the pre-test and post-test scores were 0.814 and 0.828, respectively, demonstrating a high level of consistency between the two graders (Shrout and Fleiss, 1979).

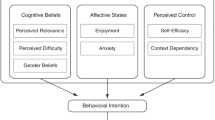

Learning motivation questionnaire

The learning motivation questionnaire was adapted from a large-scale survey conducted by Han and Xu (2010), which involved 4774 Chinese middle school students, consisting of two dimensions: intrinsic motivation (two items) and extrinsic motivation (four items). The adapted questionnaire (Appendix 2) demonstrated a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.79 (>0.7), indicating acceptable reliability (Nunnally, 1978). Moreover, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin value was 0.65, meeting the minimum threshold for factor analysis (Kaiser, 1974), suggesting that the questionnaire has adequate construct validity. Thus, this questionnaire is appropriate for measuring students’ learning motivation in EFL contexts.

Interview protocol

Two rounds of student interviews were conducted to capture both phase-specific reflections and overall perceptions of the PBLL experience. The first round took place after the completion of Project 1, including questions like, “How did you feel about the PBLL experience?” and “In what ways was learning English through the ‘Making English Class Roster’ project different from your previous English learning?” to gather students’ initial feelings of PBLL. The findings from this round provided useful feedback for refining the design of Project 2. The second round was conducted after both projects were completed, aiming for a more comprehensive understanding of students’ overall satisfaction and long-term acceptance of PBLL. It explored whether PBLL had sustained students’ interest in learning English and whether they would be willing to continue learning English through PBLL in the future. Questions included: “Would you like to continue learning English through PBLL in the future? Why or why not?”

Teacher interviews were conducted after the completion of both projects, aiming to gain insights into the effects of PBLL on students’ learning motivation and English proficiency. Only two teachers implemented the PBLL (Teacher Z and L). Three guiding questions were interviewed: (1) “In your opinion, how has PBLL influenced students’ learning motivation? Please provide specific examples from classroom observations.” (2) “Compared with traditional teaching methods, what are the strengths and limitations of PBLL in enhancing students’ English proficiency?”.

Research procedures

The entire research cycle spanned eight weeks, with the specific process outlined as follows (Fig. 1):

This figure illustrates the overall eight-week research procedure, including the pre-test, intervention, and post-test phases. Both the experimental group (EG) and control group (CG) participated in academic performance and motivation tests in Weeks 1 and 8. The EG received PBLL training followed by two modules of project-based language learning activities. Meanwhile, the CG received traditional teaching across the same period.

Phase 1: PBLL training and pre-test administration (Weeks 1–2)

In week 1, pre-tests on academic performance and learning motivation were administered to both groups. This ensured that baseline equivalence between the two groups could be established prior to the teaching intervention. In addition, this phase focused on EFL teacher PBLL training and the administration of pre-tests to assess students’ academic performance and learning motivation. In Week 1, EFL teachers were introduced to the research objectives through workshops. Meanwhile, pre-tests were administered to both the EG and CG groups. In Week 2, the project design phase commenced. Project 1 (Appendix 3) was adapted from Module 1 My Classmates, which focuses on fostering interpersonal relationships through self-introduction and peer introduction. The final product is an English class roster.

Phase 2: PBLL implementation (Weeks 3–7)

In Week 3, Project 1 was implemented over six sessions. The experimental group teacher (Z) participated as a teaching assistant to support collaborative teaching and classroom management. While the CG followed a traditional lecture-based approach, with both groups covering the same content from Module 1 of the textbook. In Week 4, PBLL teaching reflections were conducted. In Week 5, a collective lesson planning session was held to prepare for project 2.

Project 2 (Appendix 4) was adapted from Module 2: My Family with a focus on introducing your family to others. The final product is an English family picture tree book. Project 2 was then implemented in Weeks 6 and 7.

Phase 3: post-test data collection and project reflection (Week 8)

In Week 8, post-tests on academic performance and learning motivation were administered to both groups. Interviews were also conducted in the EG. Additionally, two EFL teachers participated in the semi-structured interviews.

Data collection and analysis

The data set included three parts:

The first dataset consists of students’ responses to the learning motivation questionnaire. The questionnaire was administered in paper-and-pencil format due to the lack of access to digital devices. A total of 45 pre-test and post-test responses were collected from the EG and 38 responses from the CG. Due to the lack of an online survey platform at the experimental school, research assistants printed and distributed the questionnaires in batches during the scheduled evening self-study sessions, and were responsible for collecting and logging the responses. Although efforts were made to ensure anonymous completion during school hours, some data were missing due to student absenteeism. To maintain the scientific rigor of the data analysis, only samples with valid data for both pre- and post-tests were included in the ANCOVA analysis. Before the analysis, Levene’s test for equality of variances was conducted. The results indicated that the assumption of homogeneity of variance was met: intrinsic motivation (p = 0.477), and extrinsic motivation (p = 0.855). The results indicated that the variances were equal, which justifies the use of ANCOVA for subsequent analyses. Meanwhile, the homogeneity of regression assumptions remained intact, as evidenced by (p = 0.448 > 0.05) for intrinsic motivation and (p = 0.087 > 0.05) for extrinsic motivation. These results affirmed the appropriateness of employing ANCOVA in analyzing participants’ English learning motivation.

The second dataset consists of students’ academic performance test scores, with a total of 92 valid responses collected. To ensure the assumptions of the T-test were met, the normality of the score was assessed using skewness and kurtosis. According to Roever and Phakiti (2017), skewness and kurtosis values falling between −1 and +1 are generally considered acceptable indicators of normality, particularly for small sample sizes (N < 50) (Cohen, 1988). The skewness (−0.448) and kurtosis (−0.650) of the pre-test scores, as well as the skewness (0.432) and kurtosis (−0.647) of the post-test scores for the English language knowledge test, fell within this acceptable range, indicating that the data were normally distributed. Similarly, the pre-test skewness (0.609) and kurtosis (0.197), along with the post-test skewness (0.951) and kurtosis (−0.213) for the thematic writing scores, also met the criteria for normal distribution. In addition, Levene’s test was conducted in terms of participants’ English knowledge test score in the pre-test. The result of Levene’ s test (F = 3.54, p = 0.741 > 0.05) indicated that there was no significant difference in the variances between the groups (Field, 2013). Further, the result of Levene’s test (F = 0.359, p = 0.550 > 0.05) on participants’ thematic writing scores also suggested that the variances between the groups were homogeneous. The data were further analyzed using independent samples t-tests and paired samples t-tests in SPSS software.

The third dataset comes from interviews with teachers and students. Given that most first-year students tend to be more introverted, the student interviews were conducted in written question-and-answer format. A total of 43 feedback questionnaires were collected in Week 4, and 40 were collected in Week 8. The teacher interviews were primarily semi-structured, supplemented by informal conversations. The transcribed text from the semi-structured interviews totaled 15,000 words. Since only two teachers were interviewed only once, the data were analyzed using interpretive descriptive analysis.

Results

The impact of PBL on EFL learners’ learning motivation

As illustrated in Table 1, the ANCOVA findings indicated a significant impact of PBLL on the post-test motivation scores of participants’ intrinsic motivation (p = 0.001 < 0.01). and extrinsic motivation (p = 0.001 < 0.01). Additionally, according to the standards proposed by Cohen (1998), the effect size (η2) in the ANCOVA result, indicating the influence of different instructions on participants’ intrinsic motivation, was found to be medium (η2 = 0.12 < 0.14). The effect size for PBLL’s impact on participants’ extrinsic motivation was also medium (η2 = 0.13 < 0.14). Hence, PBLL instruction has the potential to enhance participants’ learning motivation, especially intrinsic motivation.

To further examine the effects of time (pre-test vs. post-test) and group (EG vs. CG) on students’ learning motivation, a multivariate ANCOVAs was conducted.

For the intrinsic motivation, as the sphericity assumption was violated (p < 0.05), a multivariate test was employed (Table 2). The main effect of time was not significant (p = 0.06 > 0.05), indicating that there were no significant changes in intrinsic motivation from pre-test to post-test for both groups. The interaction effect between time and group was also not significant (p = 0.45 > 0.05), indicating that there was no significant difference in the change in intrinsic motivation between two groups from the pre-test to the post-test. However, the main effect of group was significant (p < 0.001), suggesting that the EG maintained a higher level of intrinsic motivation throughout the intervention compared to the CG. Further, The η2 (0.175) suggests a large effect size, meaning that the group variable accounted for 17.5% of the total variation in intrinsic motivation.

Regarding extrinsic motivation, the assumption of sphericity was also violated (p < 0.05). Therefore, multivariate tests were conducted to examine the impact of PBLL on students’ extrinsic motivation. The results (Table 3) showed that the main effect of time was not significant (p = 0.313 > 0.05), indicating that there was no overall change in extrinsic motivation for both group in pre-post-tests. However, the interaction effect between time and group was significant (p = 0.007 < 0.05), suggesting that the pattern of change in extrinsic motivation differed between two groups. Specifically, the mean score of EG decreased slightly from 3.97 in the pre-test to 3.75 in the post-test, while the CG’s mean score increased significantly from 2.68 to 3.16. This opposing trend indicates that while PBLL may have reduced students’ reliance on external incentives, traditional instruction may have reinforced extrinsic motivation through external pressures or performance-driven tasks.

In addition, the main effect of the group was also significant (p < 0.001), suggesting that the CG maintained a significantly higher level of extrinsic motivation than the EG throughout the intervention. The large effect size (η2 = 0.500) indicates that the group accounted for a substantial proportion of the variance in extrinsic motivation.

The impact of PBLL on EFL learners’ academic performance

The measurement of academic performance was divided into three aspects: overall performance on academic tests, performance in foundational English language knowledge, and performance in thematic writing. Table 4 presents the results of the independent samples t-tests.

EFL learners’ academic performance with PBLL intervention

Before the PBL intervention, the difference in the mean value of the EG and CG was not statistically significant (p = 0.078 > 0.05). However, after the PBL intervention, the mean value of the EG was lower than that of the CG. And the mean difference was statistically significant (p = 0.006 < 0.05). To further confirm the impact of PBL intervention, a paired sample T-test was conducted (Table 5). It was clear that after the PBL intervention, the mean value of the EG decreased from 56.51 to 52.73 and this change was statistically significant. Since before the PBL intervention, the equality of the variance was ensured, the research findings in Tables 4 and 5 indicated that PBL intervention had a less favorable effect on EFL learners’ academic performance.

EFL learners’ English knowledge performance with PBLL intervention

With the PBLL intervention, the English knowledge test score of the EG significantly lower than the that of the CG (Table 4). However, the results (Table 5) revealed a significant decline in the mean value of the EG (p = 0.01 < 0.05), suggesting that the PBLL intervention did not enhance students’ English knowledge performance; instead, a significant decline was observed in the EG after the intervention under the assumption of homogeneity of variance.

EFL learners’ thematic writing with PBLL intervention

As shown in Table 4, there was no significant difference between the EG and the CG in the pre-test scores (p = 0.508 > 0.05), indicating comparable writing proficiency prior to the intervention. However, in the post-test, the EG significantly outperformed the CG, with the difference reaching statistical significance (p < 0.001). This suggests that the intervention had a positive effect on students’ thematic writing performance. The paired sample T-test in Table 5 further confirmed the result. Moreover, according to Cohen (1998), the effect size for the paired sample T-test of PBLL intervention in writing was big (Cohen’s d = 0.82 > 0.5).

Participants’ perception of PBLL instruction

From the analysis of qualitative data from the experimental group students, two main themes emerged: (a) PBLL and students’ intrinsic motivation, and (b) PBLL and students’ learning autonomy.

PBLL stimulated students’ interest in learning English and enhanced their enjoyment of learning

Students think PBLL made learning more enjoyable, fun, and boosted their confidence. For example, some students mentioned, “English class (PBLL) is really fun,” “I feel happy and joyful in English class,” and “I feel really happy”. PBLL allowed students to leverage their strengths, fostering a sense of accomplishment that contributed to increased intrinsic motivation.

PBLL enhanced students' learning autonomy

Students gained more autonomy and a sense of participation in PBLL teaching. One student said, “In the past, the class roster was made by the teacher. But now, we make it ourselves. We vote for the cover of the roster. We work on it as a group. We moved the tables together when making the cover.” Another student wrote, “I can draw in English class, something I never did before. I love drawing.” These statements show that students gained more autonomy in PBLL and developed a stronger sense of collaboration.

An analysis of the interview transcripts with the participating teachers revealed that both focused on students’ intrinsic motivation and academic performance.

Firstly, PBLL played a central role in stimulating students’ intrinsic motivation. As Teacher Z observed, “I found their level of engagement exceeded my expectations. The whole class participated very actively. In fact, the students were not interested in English, especially those from township areas who usually show very low motivation to learn the language.” Similarly, Teacher L noted, “They didn’t have much interest in English before, but through doing projects, they seemed to realize that English is useful and can be spoken, not just about doing exercises.”Teacher L further elaborated, “At the beginning, they were not very engaged in the projects, but gradually they started to design on their own and actively sought help from teachers and peers. Eventually, they became deeply involved.” These insights align with students’ reflections that PBLL made learning more enjoyable, and also corroborate the quantitative findings.

Secondly, PBLL contributed to the improvement of students’ writing abilities. As Teacher Z pointed out, “I think their writing has improved, especially when supported by tasks (such as creating storybooks). Some students were even able to express themselves in complete sentences.” She added, “Throughout the PBLL process, they did a lot of writing.” Teacher L also commented, “After completing the projects, I assigned them a related writing task, and their performance was noticeably better than before.”

The qualitative data suggested that PBLL had a positive impact on enhancing rural students’ intrinsic motivation which reinforces the quantitative results.

Discussion

In the current study, PBL instruction as an innovative teaching method was carried out in a rural school in an EFL context for eight weeks to examine its impact on EFL learners’ learning motivation and academic performance. Two projects were designed and conducted. The empirical findings revealed that, compared with traditional direct instruction, PBLL did enhance students’ learning motivation. However, standardized test results indicated that PBLL did not improve students’ English knowledge performance. Notably, PBLL led to a substantial improvement in students’ thematic writing skills.

Firstly, PBL enhanced EFL learners’ learning motivation with a particularly pronounced effect on intrinsic motivation. This result aligns with other studies conducted in collectivistic cultures, where the emphasis on group harmony and collaboration often fosters intrinsic motivation when learners engage in cooperative tasks (Tran, 2019). This favorable outcome could also be attributed to the potential benefits of PBL instruction which encouraged students’ autonomy, self-efficacy, and relatedness with peers, teachers, and the real world. These research findings also aligned with the findings of Amorati and Hajek (2021), who carried out the PBLL intervention to enhance Italian L2 language learners’ learning motivation. Although their implementation faced certain challenges like difficulty managing multiple components of the project, the time-consuming nature of the project and challenges in being creative, the study still reported favorable effects on students’ intrinsic motivation and highlighted the value of PBLL in providing meaningful learning opportunities and real-world connections. Additionally, Yuliani and Lengkanawati (2017) employed PBLL to promote EFL learners’ autonomy. Their research findings indicated that PBL enhanced learners’ autonomy. As Deci and Ryan (1985) stated, autonomy was a significant factor in intrinsic motivation, and the meet of the need for autonomy increased learners’ learning motivation. Qualitative interview data, such as “Because the desks were arranged together, there was more communication and discussion among the students. When I have doubts, I can turn to others for help” and “Group work makes me more willing to express myself,” further support the findings.

It is noteworthy that this study validates the bidirectional regulatory effect of PBLL on extrinsic motivation in resource-scarce rural EFL contexts. While extrinsic motivation in the experimental group showed a slight decline, and the CG experienced a significant increase due to external pressures from traditional teaching, the interaction effect between time and group was significant. This suggests that PBLL may facilitate a shift in learners’ learning motivation from external regulation (e.g., teacher evaluation, exam pressure) to intrinsic drive. This finding resonates with the gradual process of “motivation internalization” described in Self-Determination Theory (Deci and Ryan, 1985), where PBLL reduces reliance on external rewards and punishments, encouraging students to integrate learning goals with their personal value systems. However, the significant increase in extrinsic motivation in the CG highlights the ongoing reliance on institutional pressures in traditional teaching methods in rural educational settings, revealing a persistent dilemma. This observation aligns with Holmes and Hwang (2016), who noted the limitations of teaching strategies in resource-poor regions.

Additionally, the study expands the discussion on the cross-cultural applicability of PBLL. While Amorati and Hajek (2021) and Yuliani and Lengkanawati (2017) validated the effect of PBLL on autonomy and intrinsic motivation in Western and urban contexts, this study observed comparable effects (e.g., sustained high levels of intrinsic motivation in the experimental group) among rural students with lower English proficiency and limited teaching resources. This provides critical evidence for the feasibility of PBLL in less-than-ideal educational environments.

Secondly, PBLL did not enhance EFL learners’ academic performance in general as well as in basic English knowledge. This research finding was inconsistent with the previous studies (Pichailuck and Luksaneeyanawin, 2017; Demir and Onal, 2021). Pichailuck and Luksaneeyanawin (2017) evaluated the effectiveness of PBL in young rural EFL learners’ academic performance. They claimed that all grade six EFL learners accustomed to PBL achieved a higher average score in the national standardized achievement test after one semester of PBL learning. Moreover, the ten sample participants involved in the in-depth interview also achieved a higher academic score. Similarly, Demir and Onal (2021) also stated that compared with technology-assisted learning, participants with PBL attained a higher level in the academic achievement test.

However, our research findings were supported by Holmes and Hwang (2016), who argued that students’ academic performance was similar when measured by the standard test in their two-year-long math instruction. Castañeda and Jackeline (2014) also reported that PBLL did not improve grammatical accuracy among EFL learners. Still, Halvorsen et al (2012) conducted PBL intervention in social studies with 62 second-grade students and found no statistically significant differences after PBL intervention in the academic test.

In this study, the experimental group’s scores in basic English language knowledge dropped significantly. This finding echoes the results of Holmes and Hwang (2016), who argued that when academic achievement relies on standardized tests (such as grammar choices and vocabulary filling), PBLL’s innate contextual characteristic may compete for resources with students’ need to consolidate discrete knowledge points. Specifically, rural students, who have long relied on teacher-led repetitive training models (Zhang and Su, 2021), often lack metacognitive strategies. As a result, they tend to prioritize integrated tasks in PBLL, neglecting systematic revision of basic knowledge such as vocabulary and grammar. Moreover, traditional tests, which emphasize rote memorization, conflict with the contextual application of knowledge emphasized in PBLL. Bell (2010) noted that when assessment tools misalign with instructional goals, the potential benefits of PBLL may be obscured by standardized tests.

However, the significant improvement of PBLL in enhancing EFL learners’ contextualized writing ability highlights its irreplaceability in developing complex English language skills.

The advancement in writing skills can be attributed to three mechanisms: task authenticity, meaning-driven learning and iterative writing training. The two projects, Making an English Class Roster and Creating an English Family Tree Picture Book, were closely tied to students’ school and family life. They fulfilled students’ need for relevance and prompted a shift from test-oriented writing to meaningful writing. As Boardman et al. (2024) stated, students in PBL classrooms reported experiencing more meaningful and personally relevant learning. Meanwhile, the experimental group students experienced the iterative process of writing when completing the information page for the English Class Roster and the family photo & information page for the English Family Tree Picture Book. As one of the interviewed teachers mentioned, “I feel they wrote a lot in these two projects.” In addition, the writing focus of the experimental group shifted from grammatical accuracy to content (e.g., in creating the family tree picture book, students needed to understand the English names, ages, and professions of family members). As a result, both the quantity and quality of writing in the experimental group improved. This aligns with Yuliani and Lengkanawati (2017), who emphasized that PBLL stimulates awareness of self-revision.

It is important to note that the moderating effect of the rural educational context amplified the differentiation effect mentioned above. In the short term, PBLL struggles to shake the deeply entrenched score-first culture, as mentioned by two interviewed teachers, “Although the projects are good, the final exam still focuses on knowledge points”. However, breakthroughs in thematic writing abilities provide a key entry point for reforming rural EFL education. By reconstructing the assessment system and optimizing PBLL evaluation methods, the collaborative enhancement of both foundational English knowledge and advanced skills can be achieved, thereby avoiding the “either-or” assessment dilemma in traditional teaching.

Conclusion and pedagogical implications

In an exam-driven English education environment, traditional teaching methods excessively focus on basic knowledge, neglecting the development of students’ overall competencies, which exacerbates the teaching challenges, particularly in resource-poor rural areas. PBLL offers a potential solution to overcome the limitations of traditional teaching in rural areas to balance exam requirements with the cultivation of comprehensive skills. The results of this study show that PBLL significantly enhanced EFL learners’ learning motivation, particularly intrinsic motivation. Although PBLL did not significantly improve learners’ academic performance, it demonstrated a positive impact on improving thematic writing skills. Additionally, qualitative data revealed that EFL learners showed high interest in PBLL, further validating its potential to foster students’ overall language abilities and intrinsic motivation.

Based on the research findings and discussion, several pedagogical implications were addressed:

Firstly, given that learning motivation is recognized as a pivotal factor in EFL academic success, and intrinsic motivation exerts a particularly potent positive influence on EFL learning outcomes (Lasagabaster, 2011; Ozer and Badem, 2022), EFL practitioners may adopt PBL instruction as an effective motivational strategy in enhancing EFL learners’ motivation in rural area, especially in Asian countries. As Lu et al. (2023) stated, in developing countries in Asia, where existing educational ideologies and teaching methods are relatively outdated, PBL as an advanced instructional model, can help achieve more prominent effects.

Secondly, incorporate PBLL in EFL writing. Given that PBLL enhanced EFL learners’ writing skills in rural areas, EFL teachers should consider integrating PBLL into English writing. Projects can include works such as creating essays, reports, or digital stories, which encourage EFL learners to practice and refine their writing in a meaningful context. PBLL typically integrates real-life contexts, helping students connect their English knowledge accumulation with real-world problem-solving (Buck Institute for Education, 2003). Thus, teachers should design writing projects that are relevant to students’ lives and interests, enabling them to experience the practical applications of English learning, thereby enhancing their learning outcomes.

Thirdly, EFL practitioners are suggested to integrate PBLL instruction with high-stakes academic tests to match what was taught and evaluated. In the current research, the effectiveness of PBLL intervention on EFL learners’ English knowledge was evaluated by the test focused on discrete English knowledge points, which creates a structural misalignment with the integrative language application emphasized by PBLL. Therefore, there was a mismatch between the test content and the target practicing language skills emphasized in the PBLL activities. To bridge this gap, English teachers and standardized test developers should design project tasks that promote the comprehensive development of language skills while also aligning with standardized exam requirements. For example, the project evaluations in PBLL could incorporate assessment tasks related to foundational language knowledge such as phonetics, vocabulary, and grammar, ensuring that students not only engage in authentic language use but also effectively prepare for exam content. Additionally, test developers should reform exam design based on the characteristics of PBL, ensuring that the exam content reflects the integrative language skills students acquire through PBLL, enabling the integration of teaching, learning and evaluation.

Lastly, the study’s qualitative findings were limited by the small number of participating teachers and their limited experience with PBLL, which may have affected the depth and representativeness of the interview data. Future research should involve a larger pool of trained teachers and adopt more in-depth interview methods to enhance the reliability and generalizability of the findings.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the following reasons: The regulation released by the Ministry of Education in China, was announced at a press conference on June 1, 2021. It emphasizes the protection of students’ privacy and self-esteem. In order to release the fierce competition, avoid discrimination, and alleviate the testing pressure, the examination results should not be ranked or publicly announced. In addition, with the participant's school’s permission, the exam results can be used for research only. Yet, they also state that the results can not be publicly announced.

References

Amorati R, Hajek J (2021) Fostering motivation and creativity through self-publishing as project-based learning in the Italian L2 classroom. For Lang Ann 54(4):1003–1026. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12568

Andargie A, Amogne D, Tefera E (2025) Effects of project-based learning on EFL learners’ writing performance. PLoS ONE 20(1):e0317518. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0317518

Artini LP, Ratminingsih NM, Padmadewi NN (2018) 10.Project based learning in EFL classes: Material development and impact of implementation. Dutch J Appl Linguist 7(1):26–44. https://doi.org/10.1075/dujal.17014.art

Astawa NLPNSP, Artini LP, Nitiasih PK (2017) 11.Project-based learning activities and EFL students’ productive skills in English. J Lang Teach Res 8(6):1147. https://doi.org/10.17507/jltr.0806.16

Aubrey S (2022) Enhancing long-term learner engagement through project-based learning. ELT J 76(4):441–451. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccab032

Bell S (2010) Project-based learning for the 21st century: skills for the future. Clearing House: A J Educ Strateg, Issues Ideas 83(2):39–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098650903505415

Benlaghrissi H, Meriem O (2024) The impact of mobile-assisted project-based learning on developing EFL students’ speaking skills. Smart Learn Environ 11(1):18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-024-00303-y

Boardman AG, Polman JL, Scornavacco K, Potvin AS, Garcia A, Dalton B, Stamatis K, Guggenheim A, Alzen JL (2024) Examining enactments of project-based learning in secondary English language arts. AERA Open 10:23328584241269829. https://doi.org/10.1177/23328584241269829

Buck Institute for Education. (2003). A guide to project-based learning handbook for middle and high school teachers (R Wei, Trans.). Beijing, Education, and Science Press

Cabanillas H,E (2023) The impact of interdisciplinary project based learning on young learners’ speaking results. Porta Linguarum 39:129–145. https://doi.org/10.30827/portalin.vi39.22864

Carrabba C, Farmer A (2018) The impact of project-based learning and direct instruction on the motivation and engagement of middle school students. Lang Teach Educ Res 1(2):163–174

Castañeda P, Jackeline R (2014) English teaching through project based learning method, in rural area. Cuad de Lingüística Hispánica 23:151–170

Cohen J (1998) Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates

Deci EL, Ryan RM (1985) The general causality orientations scale: self-determination in personality. J Res Personal 19(2):109–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092-6566(85)90023-6

Demir CG, Onal N (2021) The effect of technology-assisted and project-based learning approaches on students’ attitudes towards mathematics and their academic achievement. Educ Inf Technol 26(3):3375–3397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10398-8

Dörnyei Z (1998) Motivation in second and foreign language learning. Lang Teach 31(3):117–135

Field, A (2013). Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics (4th ed.). Sage Publications

Halvorsen AL, Duke NK, Brugar KA, Block MK, Strachan SL, Berka MB, Brown JM (2012) Narrowing the achievement gap in second-grade social studies and content area literacy: The promise of a project-based approach. Theory Res Soc Educ 40(3):198–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2012.705954

Han B, Xu H (2010) Analysis of the reliability and validity of a questionnaire on attitudes and motivation towards english learning among secondary school students. J Hebei Norm Univ (Educ Sci Ed) 12(10):69–74. https://doi.org/10.13763/j.cnki.jhebnu.ese.2010.10.012

Holmes VL, Hwang Y (2016) Exploring the effects of project-based learning in secondary mathematics education. J Educ Res 109(5):449–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2014.979911

Jonassen DH, Rohrer-Murphy L (1999) Activity theory as a framework for designing constructivist learning environments. Educ Technol Res Dev 47(1):61–79

Kaiser HF (1974) An index of factorial simplicity. psychometrika 39(1):31–36

Krajcik, JS and Blumenfeld, PC (2005). Project-Based Learning in Sawyer, RK (ed.) The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Landron, LM, Agreda Montoro, M, & Colmenero Ruiz, MJ (2018). The effect of project-based learning in gifted students of a second language. Revista de Educación, (380). https://doi.org/10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2017-380-378

Larmer J, Mergendoller JR (2015) Gold Standard PBL: Essential Project Design Elements. Buck Institute for Education

Lasagabaster D (2011) English achievement and student motivation in CLIL and EFL settings. Innov Lang Learn Teach 5(1):3–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2010.519030

Lave J, Wenger E (1991) Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press

Li R (2022) Design and reflection on project-based learning in junior high school English. Educ Sci Forum 13:13–17

Lu Y, Li J, Hu M, Xiao L (2023) Can project-based learning effectively improve academic performance? —a meta-analysis based on 44 experimental and quasi-experimental studies. J Educ Sci Hunan Norm Univ 22(3):105–113. https://doi.org/10.19503/j.cnki.1671-6124.2023.03.013

Ma, X (2025). An analysis of the application of project-based learning in high school English writing instruction. Overseas English, (3), 160–162

Nunnally, JC (1978). An overview of psychological measurement. Clinical diagnosis of mental disorders: A handbook, 97-146

Ozer, O, & Badem, N (2022). Student Motivation and Academic Achievement in Online EFL Classes at the Tertiary Level. LEARN Journal: Language Education and Acquisition Research Network, 15(1). https://so04.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/LEARN/article/view/256727

Park P, Lee E (2019) The impact of an arts project-based language program to enhance EFL learning. J Asia TEFL 16(4):1232–1250

Pichailuck, P, & Luksaneeyanawin, S (2017). Enhancing learner autonomy in rural young EFL Learners through project-based learning: an action research. ABAC Journal, 37(2)

Renandya W (2013) 1Essential factors affecting EFL learning outcomes. Engl Teach 68:23–41. https://doi.org/10.15858/engtea.68.4.201312.23

Roever C, Phakiti A (2017) Quantitative methods for second language research: A problem-solving approach. Routledge

Samaranayake SW (2016) Oral competency of ESL/EFL learners in Sri Lankan rural school context. Sage Open, 6(2):2158244016654202. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244016654202

Santhi, D, Suherdi, D and Musthafa, B (2019). ICT and project-based learning in a rural school: An EFL context. In Third International Conference on Sustainable Innovation 2019–Humanity, Education and Social Sciences (IcoSIHESS 2019), 29-35. Atlantis Press. https://doi.org/10.2991/icosihess-19.2019.5

Shafaei A, Rahim HA (2015) Does project-based learning enhance Iranian EFL learners’ vocabulary recall and retention? Iran J Lang Teach Res 3(2):83–99

Shin MH (2018) Effects of project-based learning on students’ motivation and self-efficacy. Engl Teach 73(1):95–114. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1312282

Shrout PE, Fleiss JL (1979) Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull 86(2):420–428. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.86.2.420

Spearman C (1987) The proof and measurement of association between two things. Am J Psychol 100(3/4):441–471

Thomas JW (2000) A Review of Research on Project-Based Learning. Autodesk Foundation

Tomaszewski W, Xiang N, Western M (2020) Student engagement as a mediator of the effects of socio-economic status on academic performance among secondary school students in Australia. Br Educ Res J 46(3):610–630. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3599

Tran VD (2019) Does cooperative learning increase students’ motivation in learning? Int J High Educ 8(5):12–20. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v8n5p12

Vygotsky, LS (1978). Mind in Society: The development of Higher Psychological Processes (Vol. 86). Harvard University Press

Yang L, Diao H (2024) Research on the application of project-based learning in foreign language teaching: A review and outlook. Foreign Lang Teach 45(1):69–75. https://doi.org/10.16362/j.cnki.cn61-1023/h.2024.01.006

Yang, Y, & Ding, H (2023). High school English reading and writing teaching design based on project-based learning. Overseas English, (22), 181–183, 196

Ye, Q, Wu, Q, Kong, X, & Chen, N (2019). Optimizing college English writing instruction based on the project-based learning model. China Higher Educ., (22), 41–42

Yuliani Y, Lengkanawati NS (2017) Project-based learning in promoting learner autonomy in an EFL classroom. Indonesian J Appl Linguist 7(2):47. https://doi.org/10.17509/ijal.v7i2.8131

Zhang W, Su R (2021) How rural small-scale schools implement project-based learning: a case analysis and insights under the concept of localized education. China Educ Technol 4:35–44

Zheng X (2022) The application of project-based learning in English teaching in vocational schools. Overseas Engl 8:238–240

Zheng Y, Yu S, Tong Z (2022) Understanding the dynamic of student engagement in project-based collaborative writing: insights from a longitudinal case study. Lang Teach Res https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688221115808

Zhao D (2024) Application of project-based learning in graduate public English under the empowerment of intelligent technology. J Jilin Institute of Chemical Technol 41(6):68–71. https://doi.org/10.16039/j.cnki.cn22-1249.2024.06.016

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Each author made substantial contributions to the research and manuscript preparation. Wenlan Zhang was responsible for the conceptualization of the study, including the research design and methodological framework. Panpan Yang and Sirui Chen jointly undertook data collection and analysis, contributed to the interpretation of findings, and discussed their implications. Panpan Yang drafted the manuscript, while Sirui Chen played a key role in revising the drafts and providing critical feedback to improve the final version. Panpan Yang and Sirui Chen contributed equally to this work. Jiawei Chen offered valuable suggestions, particularly in the qualitative data analysis stage. The combined efforts and expertise of all authors were essential to the successful completion of this study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Board (IEB) of Shaanxi Normal University under ethics approval number SNNU-ETH-2023-Ed0316, on September 10, 2023. The approval covered all stages of the research process, including participant recruitment, data collection, and data analysis. Ethical approval was obtained prior to data collection. All procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

The participants were seventh-grade students from rural middle schools in Hainan Province, most of whom were left-behind children. Informed consent was obtained in September 2023 by the researchers and classroom teachers. Given the rural setting and the difficulty of obtaining signed written consent from all legal guardians, the purpose, procedures, voluntary nature, and confidentiality of the study were verbally explained to the students during class meetings, using a standardized script approved by the ethics board. Some guardians participated remotely through phone or video conferencing. Participation was entirely voluntary, and students were informed that they could withdraw at any time without any consequences. This consent process was reviewed and approved by the IEB of Shaanxi Normal University as appropriate for the study context. While some basic demographic information (e.g., family background and parents’ occupations) was collected for research purposes, no personally identifiable information was obtained, and participants’ anonymity was strictly protected throughout the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, P., Chen, S., Zhang, W. et al. The impact of project-based learning on EFL learners’ learning motivation and academic performance: an empirical study in a Chinese rural school. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1132 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05519-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05519-y