Abstract

We investigate the connection between teacher subjective well-being (TSWB) and the learning achievement of public-school students in Peru. Leveraging data from the National Teacher Survey and the Census Student Assessment, we identify that TSWB consists of three invariant dimensions: satisfaction with school relationships, living conditions, and working conditions. Our regression models suggest that the relationship between school-level TSWB and mathematics and reading scores follows an inverted U-shape, consistent with the presence of the “too-much-of-a-good-thing” effect. This suggests diminishing returns, with an optimal threshold beyond which further TSWB increases are associated with lower pupil scores.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Teachers have a critical role in the quality of educational systems (Hanushek and Rivkin, 2006). Their influence is undeniable in the classroom, but also extends beyond it, impacting pupils’ outcomes even into adulthood (Chetty et al., 2014). Despite their pivotal role in society, several countries report serious concerns about recruiting and retaining good quality teachers (OECD, 2005), principally due to teacher shortages and deteriorating working conditions (Flores, 2023; See et al., 2020).

Behavioral science research offers potential solutions to these challenges. Enhancing subjective well-being may not only attract and retain talent but also improve job performance and productivity (DiMaria et al., 2020). Indeed, positive experiences and emotions foster motivation, creativity, and workplace interactions (Tenney et al., 2016). However, the evidence specifically related to the teaching profession remains inconclusive. It is unclear whether higher levels of teacher subjective well-being, or related constructs, lead to improvements in student achievement.

The complexity of this issue has become increasingly evident in recent literature. For instance, Hoque et al.’s (2023) review demonstrates that teachers’ levels of job satisfaction, whether low or high, can coexist with both low and high levels of student achievement, depending on the country. The meta-analysis performed by Maricuțoiu et al. (2023) reveals stable, weak correlations between teacher’s subjective well-being and student achievement. Similarly, Wartenberg et al. (2023) in their meta-analysis and systematic review, report a small to moderate relationship between teachers’ job satisfaction and student achievement, suggesting that this may be due to achievement being the most distal outcome in the causal chain under consideration.

This work examines the relationship between teachers’ subjective well-being and student learning outcomes in Peru, offering an alternative explanation for the mixed findings in recent literature. We present new evidence suggesting that the association between teacher subjective well-being and student achievement is characterized by an inverted U-shaped pattern. This relationship would be driven by the “too-much-of-a-good-thing” effect (TMGT effect) (Pierce and Aguinis, 2013), which is consistent with the fact that high levels of happiness do not always have positive effects on individuals (Britton, 2019; Gruber et al., 2011). Indeed, high levels of satisfaction can reduce motivation to seek change, pursue new goals, and engage in self-improvement, as individuals tend to prioritize maintaining their current state of happiness (Grant and Schwartz, 2011; Oishi et al., 2007).

Examining the Peruvian case within this research question provides valuable insights for testing previous findings in a developing context. Peru’s notable challenges, such as disparities in educational resources, infrastructure, and socioeconomic inequalities, significantly impact both TSWB and student achievement. These characteristics are shared by many developing countries worldwide, creating a unique context for exploring the relationship between TSWB and student outcomes. This analysis may reveal patterns that diverge from the predominantly developed-country-focused research literature.

This study provides four advancements to current literature. First, it delineates the subjective well-being structure of public sector teachers using a nation-wide representative sample. Studies in this topic have usually analyzed non-representative data, based on small samples, often selected through convenience and purposive sampling (Hascher and Waber, 2021). Second, instead of narrowly focusing on one aspect of well-being, such as the conventional job satisfaction (Hoque et al., 2023; Zieger et al., 2019), we provide a comprehensive examination of different TSWB dimensions. Our data set contains questions about teachers’ satisfaction with different aspects of their life and work, providing a better picture of their well-being. Third, it pioneers exploring how different aspects of TSWB relate to students’ academic outcomes in developing contexts, expanding beyond the prevalent focus of existing literature on developed countries. Lastly, this study employs a flexible specification to capture potential non-linearities in the TSWB–student learning relationship, recognizing that patterns may vary across well-being levels and offering a new perspective on their association.

To tackle our objective accordingly, the empirical strategy relies on the National Teacher Survey (ENDO) 2016 and 2018, carried out by the Peruvian Ministry of Education. Our study leverages the untapped potential of this resource, which, despite its richness and distinctiveness within the context of developing countries, has been largely overlooked and underutilized in academic research. For our purposes, ENDO provides mainly the school average TSWB score. We match these data with school test scores in mathematics and reading, obtained from the Census Student Assessments. We complement this information with data from the School Census to obtain school characteristics, and the Poverty Map for monetary poverty rates at the district level.

Our findings unveil a portrait of TSWB, comprising three pivotal dimensions: satisfaction with school relationships, living conditions, and working conditions. The multigroup confirmatory factor analysis reveals the robustness of this structure over time (2016–2018), across educational levels, geographical locations, and rural settings. Furthermore, the study illuminates noteworthy disparities in TSWB levels between primary and secondary education, among teachers motivated by vocation, and those contemplating a change in their school district. Interestingly, TSWB exhibits an inverted U-shaped relationship with students’ learning achievement, suggesting an optimal threshold beyond which higher TSWB correlates with negative returns. Finally, among the TSWB dimensions, school relationships emerge as the most influential in shaping TSWB dynamics.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. First, we present the related literature and institutional setting (section “Background”). Then, we describe the data (section “Data”) and the empirical strategy (section “Methodology”), followed by a presentation of the main results (section “Results and Discussion”). The conclusions and policy implications close the document (section “Conclusions”).

Background

Related literature

While research on teacher well-being and student learning in Latin America, particularly Peru, remains scarce, international studies provide valuable insights into this relationship. This section incorporates findings from various contexts to build a broader theoretical framework while acknowledging potential differences in educational systems and socio-economic conditions.

Subjective well-being comprises the individuals’ appraisals about their whole life or certain aspects of their experience such as job, marriage, etc. (Diener et al., 2018). Extensive literature suggests that subjective well-being has an important relationship with the performance of workers and organizations (Oswald et al., 2015; Salgado and Moscoso, 2022). As workers have positive evaluations about their job and life experiences, they increase their self-regulation, motivation, creativity, positive relationships, among other aspects, which in turn contribute to the performance of organizations (Tenney et al., 2016). Recently, the interest to understand teachers’ subjective well-being and its relationship to students’ learning have increased (Hoque et al., 2023; Maricuțoiu et al., 2023; Wartenberg et al., 2023). Examining these academic concerns offers opportunities to enhance teacher policies and students’ educational experiences.

Current literature on the structure of TSWB has mainly focused on job-related aspects. For instance, the TSWB scale developed by Renshaw et al. (2015) assesses specific psychological features of teachers within their workplace. In the same vein, other scholars have investigated the invariance of job satisfaction of teachers across countries that participated in the Teaching and Learning International Survey (Katsantonis, 2020; Zakariya et al., 2020; Zieger et al., 2019). These studies highlighted the differences between countries in this job attitude. Nevertheless, the well-being of workers is also significantly influenced by their satisfaction with life and its various domains (Erdogan et al., 2012). This holds true for teachers as well (Demirel, 2014). Thus, it is critical to consider these aspects in TSWB measures. We propose a holistic approach to study TSWB, defining it as the teachers’ judgments about their living and working experiences. Fitch et al. (2017) advanced in this line with a non-representative sample of 183 Mexican teachers. However, a literature gap persists in the testing of such measures with representative samples in developing contexts.

Studies on the relationship between TSWB and student learning present mixed results. Maricuțoiu et al. (2023) performed a meta-analysis of 26 studies finding that eudaimonic well-being is weakly related to students’ learning achievements (r = 0.065). Wartenberg et al. (2023) find similar results in their meta-analysis of 105 studies on teacher job satisfaction and students’ achievements (r = 0.10). A third meta-analysis reveals varied associations between teacher job satisfaction and student achievement, including high satisfaction with low achievement, and vice versa (Hoque et al., 2023). We argue that the “too-much-of-a-good-thing” effect (TMGT effect) can explain this puzzle of mixed results found in the literature. Indeed, the TMGT effect states that something positive, when presented in excess, can have the opposite result than expected (Pierce and Aguinis, 2013). This concept is somewhat related to the “dark side” of happiness (Gruber et al., 2011).

In this context, the present research aims to explore TSWB focusing on its structural dimensions and its link with student learning achievement. Drawing on the literature cited above and the ENDO survey, we anticipate uncovering three TSWB dimensions. First, satisfaction with living conditions, including health, self-esteem, and family concerns (Cumming, 2017; E. S. Lee and Shin, 2017; Milfont et al., 2008; Yamamoto, 2017; Yamamoto et al., 2008, 2022). Second, school relationships, encompassing interactions with colleagues, superiors, students, and parents (Hascher and Waber, 2021). Third, working conditions, encompassing factors such as teachers’ salaries, which have been related to their well-being (Song et al., 2020) and it is a critical concern in Peruvian educational policy (Vargas and Cuenca, 2018). Finally, we do not expect a linear relationship between TSWB and student learning achievement due to the TMGT effect.

Institutional setting

Peru’s basic public education system serves over 6 million students across three levels: preschool (ages 3–5), primary (ages 6–11), and secondary (ages 12–16). School attendance rates are high, with ~99% of primary-age children enrolled and ~90% attending pre-primary and secondary levels (INEI, 2024). Despite significant improvements in coverage, structural challenges persist, particularly in terms of inequality (Rentería, 2023a). Educational quality varies considerably between urban and rural areas (Arteaga and Glewwe, 2019; Guadalupe, 2024), with remote regions facing severe infrastructure deficiencies (Guadalupe et al., 2017). Public investment in education remains low at 3.8% of GDP. At the same time, the expansion of privatization presents challenges, particularly the poor quality of low-cost private schools (Minedu, 2018; Rentería, 2023b).

Peru’s public education system employs nearly 400,000 teachers. The 2012 Teacher Reform Law introduced a merit-based career structure with eight progression levels. However, major challenges persist, including low salaries—among the lowest in Latin America even after recent increases (Mizala and Ñopo, 2016)—and stark disparities in working conditions between urban and rural schools (Castro and Guadalupe, 2021). These factors shape the teaching profession and influence teacher well-being.

International comparisons help contextualize these challenges. OECD countries typically invest over 5% of their GDP in education and provide more structured teacher support systems (OECD, 2024). These differences in investment, working conditions, and professional development contribute to gaps in teacher well-being and student outcomes between Peru and higher-income countries. Reflecting these disparities, PISA assessments consistently show that students in OECD countries outperform their Peruvian counterparts in mathematics, reading, and science (Minedu, 2022).

While this study focuses exclusively on public schools in Peru, its findings contribute to broader discussions on teacher well-being in developing countries with similar structural constraints. Understanding these challenges is essential for designing policies that support teachers and improve educational outcomes.

Data

This study uses pooled data from the 2016 and 2018 editions of the National Teacher Survey (ENDO), conducted by the Peruvian Ministry of Education.Footnote 1 ENDO offers national data on regular basic education teachers across both public and private sectors. The ENDO survey follows a probabilistic, stratified, two-stage sampling design, conducted independently within each of the country’s 25 departments (first-level administrative divisions). The stratification criteria include department, educational level (initial, primary, secondary), type of management (public, private), and geographic area (urban, rural). In the first stage, educational institutions were selected using systematic sampling with probability proportional to size. In the second stage, teachers were selected systematically with a random start, based on lists obtained during fieldwork. The 2016 sample included roughly 9800 teachers from 3000 schools, while 2018 encompassed 15,000 teachers from 4500 schools. We restrict the analysis to public sector primary and secondary schools.Footnote 2

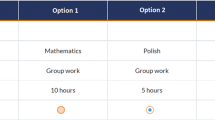

For the purposes of this paper, ENDO provided mainly the questions dealing with teachers’ subjective well-being. These questions are of the form: “Taking all things together, would you say you are…? (i) Not at all satisfied, (ii) A little satisfied, (iii) Satisfied, (iv) Very much satisfied”. Table 1 shows the dimensions included in ENDO’s questionnaire.Footnote 3

The main analysis of this paper builds on aggregated data at the school level. However, to obtain school TSWB measures we must first work at the teacher level. The sample for obtaining TSWB measures at the school level was made up of 12,661 teachers, almost equally distributed between primary and secondary school levels (Supplementary Table A1). Likewise, the teachers working in urban schools tended to be older and to have permanent positions. These patterns are similar to those shown by other authors (Díaz and Ñopo, 2016; Guadalupe et al., 2017).

Our sample of teachers is distributed among 3719 clusters (school-year), as shown in Supplementary Table A2.Footnote 4 In the majority of clusters (almost 6 out of 10), between one and three teachers were surveyed. As stated above, the objective was to work at the school level, since we had no identifier to match students’ test scores to particular teachers, only to schools. In this sense, the characteristics of the sample of schools are presented in Supplementary Table A3.

The second database is the Census Student Assessment (ECE), which is a national standardized test administered by the Ministry of Education. Depending on the year, the ECE is administered to second or fourth-grade primary students, and also to second-grade secondary students. Although it has evolved to greater diversity of subjects in secondary education, here, for the sake of comparability, we restricted the analysis to the results of mathematics and reading tests. Likewise, we considered only the population in regular basic education in 2016 and 2018.

Using ECE, we calculated the pupils’ mean scores in mathematics and reading tests for each school-year. Then we transformed them into z-scores (at the school level) and assigned these scores to each of the schools surveyed by ENDO. Finally, we used the School Census 2016 and 2018 (Ministry of Education) to obtain characteristics at the school level (numbers of pupils and teachers, geographical location, among others), as well as the poverty maps for 2013 and 2018 (National Bureau of Statistics) to assign to each school the average poverty rate of its district in monetary terms.

Methodology

To obtain a measure of TSWB, we proceed as follows after splitting the sample of teachers surveyed by ENDO into two random subsamples. First, we performed an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) with subsample 1, as a preliminary step to observing if the proposed latent variables emerged among ENDO’s items (Goretzko et al., 2021).Footnote 5 Second, to test our theoretical three-dimension solution, we performed a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) with subsample 2. We employed standard criteria for the fit indices assessing our CFA models, namely CFI > 0.900, RMSEA < 0.080, and SRMR < 0.080 (Hooper et al., 2008; Hu and Bentler, 1999). Third, to ensure that our factor solution has the same configuration, meaning, and is comparable across groups (by year, teaching level, rurality, and geographical region), we performed a Multi-Group Confirmatory Factor Analysis (MGCFA). We took a bottom-up approach (Steenkamp and Baumgartner, 1998), testing progressively configural (same loading pattern), metric (same factor loadings), and scalar (same intercepts) levels of invariance (Nießen et al., 2020). The same fit indices used for CFA were also used to test configural invariance. For metric and scalar invariance, we followed Chen (2007) recommendations to consider that the model has not been undermined: ΔCFI ≤ −0.010 and ΔRMSEA ≥ 0.015 or ΔSRMR ≥ 0.010. Finally, we tested the external validity of these dimensions by analyzing the relationship between the scores obtained in each of these latent variables (based on CFA) with other indicators also present in ENDO, using the whole sample (Table 2). This complied with two conditions: (i) being also related to subjective well-being, and (ii) not having been included in the previous steps. This kind of test is a common practice for validating psychometric constructs (Renshaw et al., 2015).

Next, to assess the association between teacher subjective well-being and student academic performance, we performed an OLS regression of the following form, at the school level:

For each school s: Ys is the average students’ test z-score in school s, TSWBfs is the school s’s score in the teacher subjective well-being factor f. We incorporate control variables to mitigate potential omitted variable bias and isolate the partial correlation between TSWB and student learning from confounding elements at the school and district levels. The vector As includes the following school-level characteristics that can influence both the teaching environment and student outcomes: number of teachers, female teacher ratio, fixed-term teacher ratio, student-teacher ratio, and number of educational areas. The number of teachers reflects school size, while the female teacher ratio may capture gender dynamics in the teaching environment. The fixed-term teacher ratio accounts for employment stability, influencing staff turnover. The student-teacher ratio serves as a proxy for class size and instructional quality. Lastly, the number of educational areas, representing the number of rooms, reflects the school’s infrastructure capacity. These variables help control for school-level heterogeneity. The vector Bd includes district-level characteristics that may shape both school resources and educational conditions: poverty rate, rural status, and geographic domain. The poverty rate captures the economic context, which can influence school funding, student preparedness, and access to educational resources. The rural status distinguishes schools in less populated areas, often associated with limited infrastructure and teacher availability. The geographic domain accounts for broader regional differences that may affect policy implementation and educational opportunities. These variables help control for district-level heterogeneity in the analysis. The terms δt and δg capture survey year and student assessment grade fixed-effects. Finally, εs is the usual error term. The coefficients of interest are β1 and β2. A positive value for the former and a negative value for the latter would provide empirical support for a nonlinear relationship. To confirm this, we formally test for an inverted U-shaped relationship using the test proposed by Lind and Mehlum (2010). This test verifies whether the estimated relationship is concave within the observed range of the independent variable by assessing whether the slope of the regression function is significantly positive at lower values and significantly negative at higher values. Following their approach, we estimate a quadratic specification and compute confidence intervals for the extreme point to ensure that it falls within the range of the data. In our context, this method provides a rigorous statistical test for the TMGT hypothesis.

Results and discussion

The structure of teachers’ subjective well-being

The results from EFA support the initial hypothesis that teachers’ subjective well-being is configured by three factors of satisfaction with acceptable internal consistency (Supplementary Table B1): satisfaction with school relationships (hereafter, F1), satisfaction with living conditions (hereafter, F2), and satisfaction with working conditions (hereafter, F3). Using this solution, the results from CFA align with those of EFA, suggesting that the structure of three TSWB dimensions is acceptable (χ2 = 1964.31/df = 99, CFI = 0.917, RMSEA = 0.055, SRMR = 0.038).

Next, the MGCFA compared our factor solution across the eight geographic regions considered in the survey: the North, Central and South Coast; the North, Central and South Andes; the Amazonian Rainforest, and the Capital City - Lima. Configural invariance did not reach an acceptable CFI (χ2 = 4849.40/df = 696, CFI = 0.899, RMSEA = 0.062. SRMR = 0.046). We also did not obtain good fit indicators for the metric (χ2 = 5055.20/df = 780, CFI = 0.897, RMSEA = 0.059. SRMR = 0.050) and scalar (χ2 = 5478.35/df = 864, CFI = 0.889, RMSEA = 0.058. SRMR = 0.050) level of invariance with that configuration. Therefore, we run factor analyses on each of these geographical groups to identify problematic items (Schneider, 2017). The factor loadings for social recognition, student achievement, school location, and pedagogical activity exhibited significant disparities between the groups studied. Thus, we proceed to run the MGCFA without these items, obtaining acceptable fit indices for configural, metric, and scalar invariance across the eight geographic regions, the two survey years (2016 and 2018), the teaching level (primary and secondary), and rural (vs. urban) setting (cf. Table 3).

Finally, we run a CFA with this last model with the whole sample, getting good fit indices (χ2 = 2369.25/df = 41, CFI = 0.918, RMSEA = 0.067. SRMR = 0.038).

In the light of these results, the subjective well-being of Peruvian teachers may be summarized under three broad headings (dimensions), as depicted in Fig. 1. The results confirm that, in the case of teachers, the relationships with the school community, with students’ parents, and with students themselves are relevant to their subjective well-being, in addition to the predictable relationships with peers and superiors (factor 1). In the case of Peruvian teachers, who are on average 45 years old and have generally formed their own families, aspects such as children’s education or family relationships are part of the evaluation of their satisfaction with life (factor 2). This suggests a different approach to understanding subjective well-being, because most of these measures traditionally have individualistic indicators that do not necessarily consider family concerns (Krys et al., 2021). Finally, working conditions such as salary or retirement are important aspects of a teacher’s well-being (factor 3). Moreover, these dimensions are closely interrelated.

Teacher subjective well-being: Confirmatory Factor Analysis path diagram. This confirmatory factor analysis model depicts three latent constructs (represented by ovals) operationalized through multiple observed satisfaction indicators (rectangular boxes): F1 = “Satisfaction with school relationships”, F2 = “Satisfaction with living conditions”, and F3 = “Satisfaction with working conditions”. Double-headed arrows indicate correlational relationships between latent variables, while unidirectional arrows represent standardized factor loadings. Circles denote measurement error terms associated with each observed variable. Goodness-of-fit indices are reported: Chi-square test (Chi2), Degrees of Freedom (df), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR).

Having confirmed the structural form of TSWB, we can predict, for each teacher, her score for each TSWB factor and study their main features. Larger values indicate higher levels of subjective well-being in the corresponding factor. By construction, they all have a mean virtually equal to zero. However, the TSWB factor 3 has the lowest variance (sd = 0.22), while factor 1 has the highest (sd = 0.31).

The results from external validation show that the three identified dimensions are associated with other indicators of teachers’ subjective well-being. Teachers satisfied with their school relationships, living conditions, and working conditions are more inclined to express support for their children pursuing a teaching career, exhibit a higher likelihood of choosing the teaching profession again, experience greater happiness in their school job, and report overall satisfaction with life and job (Table 4). The associations between TSWB dimensions and satisfaction with life and job exhibit considerable strength, implying a coherent alignment between TSWB dimensions and these job-related attitudes. The TSWB dimensions display weak or moderate correlations (Gignac and Szodorai, 2016) with the remaining measures in Table 4, indicating, however, that our well-being dimensions are also associated with affective or behavioral outcomes. Consequently, we can assert that the three dimensions serve as valid measures of TSWB.

In this context, we explore the associations between TSWB factor levels and various teacher and school characteristics, as well as teachers’ perceptions, by estimating linear regression models (cf. Supplementary Table C1). Figure 2 illustrates the coefficients for factor 1.Footnote 6 Descriptive graphs of key variables are provided in Supplementary Figs. E1–E4.

Among the variables under consideration, those in the model related to teachers’ perceptions are particularly relevant. For example, more satisfaction with household income is associated with a higher score in TSWB factor 1. In the same way, those teachers who chose their profession based on vocation (rather than pragmatic reasons) show higher TSWB scores. With respect to school characteristics, dissatisfaction with the location of the school is associated with lower TSWB levels. Likewise, teachers in secondary education exhibit lower scores in factor 1 compared to those in primary education. This suggests that primary and secondary levels pose different challenges to teachers, which is consistent, for instance, with evidence from the UK that secondary teachers have lower subjective indicators of well-being than primary teachers (Scanlan and Savill-Smith, 2021).

TSWB and student achievement: The TMGT effect

As a first descriptive approximation, Fig. 3 presents non-parametric conditional expectation functions regarding the relationship between students’ learning achievement and the TSWB factors. The curves show an inverted-U shaped pattern, meaning that there is a nonlinear relationship between our variables of interest. Students’ z-scores increase with TSWB, but only up to a threshold beyond which they start to decrease. This kind of relationship is not uncommon when studying subjective well-being or related topics: it is often the case that having only a little or having a great deal of something is not beneficial (Grant and Schwartz, 2011).Footnote 7 Speaking more generally, this issue could be related to the meta-theoretical principle called the “too-much-of-a-good-thing” effect (Pierce and Aguinis, 2013), which occurs when “an initially positive relation between an antecedent and a desirable outcome variable turns negative when the underlying ordinarily beneficial antecedent is taken too far, such that the overall relation becomes nonmonotonic” (Busse et al., 2016, p. 131).

Students’ learning achievement and teachers’ subjective well-being factors. This figure shows non-parametric conditional expectation functions at the school level. Panel (a) plots mathematics z-scores and panel (b) reading z-scores on the y-axis, against school-level teacher subjective well-being (TSWB) factor scores on the x-axis. Each panel includes three plots: Factor 1 “Satisfaction with school relationships” (top), Factor 2 “Satisfaction with living conditions” (middle), and Factor 3 “Satisfaction with working conditions” (bottom).

Let us now consider the OLS results from Eq. (1). Tables 5 and 6 present the TSWB factors and their squared terms for mathematics and reading tests, respectively, while progressively controlling for the covariates outlined in section 4 (in addition, heterogeneity analyses are reported in Supplementary Tables F1 to F6.).Footnote 8 As expected, the coefficient magnitudes change with the inclusion of controls, reflecting TSWB’s correlation with school and district characteristics. However, the sign remains consistent in most cases. Incorporating controls helps mitigate omitted variable bias, providing a clearer estimate of its independent association with learning achievement. Focusing on columns (3), (6), and (9), the linear coefficients related to TSWB factors display the expected sign with schools’ average scores in both mathematics and reading. That is, the greater the TSWB component, the higher the test score. In contrast, the squared TSWB factors’ term displays negative values, suggesting diminishing associations, aligning with the initial descriptive patterns presented in Fig. 3. It is worth noting that the three TSWB factors show statistical significance simultaneously for both the linear and the squared terms, except for factor 3 in reading.

The formal test of the U-shaped pattern is detailed in Supplementary Table D1. The results suggest an inverted U-shaped relationship between the three TSWB factors and academic achievement, with the only exception being factor 1 in reading, which falls just short of statistical significance at the 10% level. The conclusion is based on the verification of a negative second derivative and the extremum point being sufficiently distant from the data boundaries. While the underlying relationship for the latter factor may be convex but monotonic, it remains consistent with the presence of diminishing marginal returns.

Additionally, Table 7 reports the predicted change in student test scores across TSWB deciles. For all three TSWB factors, a substantial improvement is observed as TSWB increases from low to mid levels. However, the marginal gains decrease as TSWB rises, with predicted changes approaching zero or even becoming negative by the 80th or 90th deciles.

Regarding TSWB factor 1, it is plausible to argue that, at moderate levels, having good school relationships means that a teacher maintains harmonious interactions with colleagues, superiors, and other members of the educational staff. These positive relationships may promote a collaborative work environment, where teachers share resources, ideas, and strategies, and mutually support each other in challenges. Such dynamics can contribute to a healthy work atmosphere, enhance job satisfaction, and improve effectiveness (Tran et al., 2018). However, for sufficiently high values of TSWB factor 1, further increases may no longer yield gains in student achievement. Indeed, an excessive focus on maintaining positive work relationships may entail drawbacks (Pillemer and Rothbard, 2018). For instance, a teacher might avoid necessary confrontations or refrain from giving constructive feedback for fear of harming relationships. This aversion to conflict could lead to the perpetuation of ineffective educational practices or failing to address significant issues in the classroom or institution. Ultimately, extreme closeness between colleagues might also hinder the necessary objectivity in certain pedagogical or administrative decisions, where it is essential to maintain a degree of professionalism and distance (Pillemer and Rothbard, 2018).

Similarly, the rationale extends to TSWB factor 2. Previous studies suggest that individuals highly satisfied with their circumstances are less likely to be motivated to pursue changes on them (Oishi et al., 2007). Thus, teachers largely satisfied with their living conditions might potentially face challenges such as complacency, reduced motivation, or a lack of resilience in the face of professional difficulties. Also, they may prioritize personal commitments over their professional responsibilities. Consequently, this could lead to a plateau or decline in their effectiveness as educators, with potential repercussions on student achievement.

Regarding TSWB factor 3, focusing on working conditions and student achievement, we argue that a similar logic operates (Oishi et al., 2007). When teachers face high levels of satisfaction with working conditions, this is not necessarily related to improvements in their performance. However, these results need careful consideration as data does not fit well with the model and more studies are required. Specifically, the bottom panel of Fig. 3 revealed that a quadratic function may not be the optimal choice for capturing the relationship between TSWB factor 3 and student achievement in our dataset, given the strong positive skewness of the distribution. While alternative functions might be more suitable, they often entail a trade-off with increased complexity in interpretation. In essence, the presence of the TMGT effect is also suggestive with factor 3.

In sum, our findings contribute to the literature by highlighting the counterintuitive effect of excessive teacher well-being on student achievement. This aligns with the TMGT effect, where high satisfaction levels may reduce motivation to seek change, pursue new goals, and engage in self-improvement, as individuals prioritize maintaining their current state of happiness (Grant and Schwartz, 2011; Oishi et al., 2007). This diminished drive could translate into less adaptive teaching practices, ultimately affecting student outcomes.

Conclusions

This study first proposed a structure for TSWB based on items from the National Teacher Survey, using a representative sample of public basic education teachers. The structure considered three dimensions that were validated by exploratory, confirmatory, and multi-group factor analyses: (i) school relationships, (ii) living conditions, and (iii) working conditions. Our results expand the current literature by establishing that the well-being of teachers involves not only certain facets of their workplace but also aspects of their personal life (Fitch et al., 2017; Song et al., 2020). Furthermore, our results indicate interconnectedness between the working and living aspects of TSWB. Future studies should move beyond narrow job-focused conceptions and integrate life domain aspects for a comprehensive understanding of TSWB.

Next, based on an analysis at the school level, OLS regressions show that TSWB is associated with students’ mathematics and reading scores in an inverted U-shaped pattern, resembling diminishing marginal returns, where the association turns negative beyond a certain threshold.

We argue that this result can be explained by the presence of the “too-much-of-a-good-thing” effect. This phenomenon has been observed in the association between well-being and workplace outcomes (Lam et al., 2014), specifically concerning aspects like personal traits (Zhang et al., 2021) and leadership styles (S. Lee et al., 2017). High satisfaction with living and working conditions may reduce the motivation to seek improvements in these areas. Thus, excessive happiness does not necessarily ensure optimal psychological functioning (Gruber et al., 2011). Additionally, high satisfaction with working relationships may contribute to these effects, as excessive happiness and sociability have been linked to negative career outcomes (Grant and Schwartz, 2011). Our findings support the idea that moderate well-being levels are more beneficial (Oishi et al., 2007).

Further, our results indicate that school relationships have the strongest link to student achievement, highlighting their role in teacher well-being and educational outcomes. This is not unexpected, given the inherently social nature of the teaching profession. In this setting, optimal workplace relationships, characterized by harmonious interactions, promote collaboration and enhance educational effectiveness among teachers (Harter et al., 2003). However, an overemphasis can deter constructive feedback, perpetuate ineffective practices, and divert focus from core responsibilities like lesson planning. Excessive closeness can also compromise objectivity in pedagogical decision-making, potentially encouraging favoritism and hindering the application of sanctions. This underscores the necessity of maintaining a balanced approach to professional relationships within educational settings. Previous studies in organizational psychology could support these hypotheses suggesting that close workplace relationships can erode organizational environments (Pillemer and Rothbard, 2018).

This paper contributes to understanding the ambiguous or inconclusive results of previous research on the relationship between TWSB and learning outcomes (Hascher and Waber, 2021; Hoque et al., 2023; Maricuțoiu et al., 2023). It underscores that the salience of this relationship extends beyond the realm of workplace aspects of teachers’ well-being. A thorough understanding of teachers is essential for analyzing their performance and its implications for learning outcomes. Furthermore, the introduction of the TMGT effect, an element hitherto overlooked in the literature, accentuates that heightened well-being levels may not uniformly translate to enhanced outcomes, even within educational contexts.

Our findings support the idea that TSWB may be for policymakers a variable with a high potential to exert influence. Recognizing the link between TSWB and student success enriches the traditional education production function, giving a wider scope for effective educational policies. Positive interventions for improving current teachers’ relationships, including personal and professional development, and managerial skills for school principals, could be considered to improve teachers’ subjective well-being and thereby boost their effectiveness in the short term. In policy terms, this paper introduced a psychometric tool for assessing TSWB, which has been validated in a substantial and representative sample. Employing this questionnaire with diverse teacher populations may pinpoint areas of dissatisfaction, enabling policymakers to tailor interventions addressing specific concerns. Furthermore, the findings highlight the importance of interpersonal relationships in schools for both teacher well-being and student learning, underscoring the need for policies that foster positive school relationships.

This study has two main limitations. First, the analysis is restricted to the survey’s predefined dimensions of teacher well-being, which future qualitative research could expand. Second, while we examine the relationship between teacher well-being and student learning, this study does not establish causality due to data limitations. Notably, since individual students could not be matched with their respective teachers, the analysis was conducted at the aggregated school level.

Finally, promising avenues for further exploration include causal analysis, the role of mediating and moderating variables, and the potential impacts of student achievement on teachers’ well-being at the organizational level, even though previous evidence at the individual level suggests that this reverse causality may not hold (Kidger et al., 2016).

Data availability

The datasets used in this study are publicly available from the Peruvian Ministry of Education repository, accessible upon request through their online system at https://esinad.minedu.gob.pe/sisolai/FrmSolicitud.aspx.

Notes

While ENDO has five available editions, we excluded 2020 and 2021 because the methodology shifted to phone surveys with reduced questions. Likewise, 2014 was also excluded due to variations in items and well-being scales, featuring six Likert-type options, in contrast to the four options in 2016 and 2018. Consequently, our analysis focuses on the data from these two specific years.

Similar items have already been used to measure subjective well-being in Peruvian psychological research (Yamamoto, 2017; Yamamoto et al., 2008). The distribution of the eighteen items that inquire about the level of teachers’ satisfaction with different aspects of their life and work are presented in Supplementary Table A4.

Given our pooled data, the same school may appear in different years. To address this, we define clusters by “school-year”, treating each combination as a distinct unit. Clustered standard errors are used in the regression analysis to account for this structure.

We closely followed the modern evidence-based best practice procedures compiled by Watkins (2022).

Here we discuss only the results for factor 1, since the conclusions are similar for the other factors.

For instance, “whereas having too little time is indeed linked to lower subjective well-being caused by stress, having more time does not continually translate to greater subjective well-being. Having an abundance of discretionary time is sometimes even linked to lower subjective well-being because of a lacking sense of productivity” (Sharif et al., 2021, p. 1).

Our sample includes 3675 schools present in both ECE and ENDO. Missing data are minimal, with 69 schools lacking TSWB variables and 60 missing the number of classrooms from the School Census, representing less than 2% of the sample. Our analyses show no evidence of bias. Listwise deletion provides unbiased and consistent estimates under the Missing Completely at Random assumption. A means comparison test on school characteristics found no significant differences between excluded and retained schools, supporting the validity of our approach.

References

Arteaga I, Glewwe P (2019) Do community factors matter? An analysis of the achievement gap between indigenous and non-indigenous children in Peru. Int J Educ Dev 65:80–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2017.08.003

Britton WB (2019) Can mindfulness be too much of a good thing? The value of a middle way. Curr Opin Psychol 28:159–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.12.011

Busse C, Mahlendorf MD, Bode C (2016) The ABC for studying the too-much-of-a-good-thing effect: a competitive mediation framework linking antecedents, benefits, and costs. Organ Res Methods 19(1):131–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428115579699

Castro MP, Guadalupe C (2021) Una mirada a la posición social del docente peruano: Remuneraciones, jornada laboral y situación de los hogares. In: En C Guadalupe (ed.) La educación peruana más allá del Bicentenario. pp 327–345. Universidad del Pacífico. https://fondoeditorial.up.edu.pe/producto/la-educacion-peruana-mas-alla-del-bicentenario-nuevos-rumbos-ebook/

Chen FF (2007) Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Struct Equ Modeling: A Multidiscip J 14(3):464–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

Chetty R, Friedman JN, Rockoff JE (2014) Measuring the impacts of teachers II: teacher value-added and student outcomes in adulthood. Am Econ Rev 104(9):2633–2679. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.9.2633

Cumming T (2017) Early childhood educators’ well-being: an updated review of the literature. Early Child Educ J 45(5):583–593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-016-0818-6

Demirel H (2014) An investigation of the relationship between job and life satisfaction among teachers. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 116:4925–4931. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.1051

Díaz JJ, Ñopo H (2016) La carrera docente en el Perú. En Investigación para el desarrollo en el Perú: Once balances. Grupo de Análisis para el Desarrollo. pp 353–402

Diener E, Oishi S, Tay L (2018) Advances in subjective well-being research. Nat Hum Behav 2(4):4. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0307-6

DiMaria CH, Peroni C, Sarracino F (2020) Happiness matters: productivity gains from subjective well-being. J Happiness Stud 21(1):139–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00074-1

Erdogan B, Bauer TN, Truxillo DM, Mansfield LR (2012) Whistle while you work: a review of the life satisfaction literature. J Manag 38(4):1038–1083. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311429379

Fitch RIG, Pedraza YTC, Sánchez M, del CRS, Basurto MGC (2017) Measuring the subjective well-being of teachers. J Educ Health Community Psychol 6(3):3. https://doi.org/10.12928/jehcp.v6i3.8316. Article

Flores MA (2023) Teacher education in times of crisis: enhancing or deprofessionalising the teaching profession? Eur J Teach Educ 46(2):199–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2023.2210410

Gignac GE, Szodorai ET (2016) Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personal Individ Differ 102:74–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.069

Goretzko D, Pham TTH, Bühner M (2021) Exploratory factor analysis: current use, methodological developments and recommendations for good practice. Curr Psychol 40(7):3510–3521. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12144-019-00300-2

Grant AM, Schwartz B (2011) Too much of a good thing: the challenge and opportunity of the inverted U. Perspect Psychol Sci 6(1):61–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610393523

Gruber J, Mauss IB, Tamir M (2011) A dark side of happiness? How, when, and why happiness is not always good. Perspect Psychol Sci 6(3):222–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691611406927

Guadalupe C (2024) Desempeños diferenciados en una evaluación de matemáticas en Perú: Entorno local y abstracción en escuelas rurales. Rev Peru de Investigación Educativa 16(21):21. https://doi.org/10.34236/rpie.v16i21.487

Guadalupe C, León J, Rodríguez JS, Vargas S (2017) Estado de la educación en el Perú: Análisis y perspectivas de la educación básica. GRADE. https://repositorio.minedu.gob.pe/handle/20.500.12799/5692

Hanushek EA, Rivkin SG (2006) Teacher Quality. En Handbook of the Economics of Education, pp 1050–1078 https://doi.org/10.1016/S1574-0692(06)02018-6

Harter JK, Schmidt FL, Keyes CLM (2003) Well-being in the workplace and its relationship to business outcomes: a review of the Gallup studies. En Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived, pp 205–224. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10594-009

Hascher T, Waber J (2021) Teacher well-being: a systematic review of the research literature from the year 2000–2019. Educ Res Rev 34:100411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2021.100411

Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen MR (2008) Structural equation modelling: guidelines for determining model fit. Electron J Bus Res Methods 6(1):1

Hoque KE, Wang X, Qi Y, Norzan N (2023) The factors associated with teachers’ job satisfaction and their impacts on students’ achievement: a review (2010–2021). Human Soc Sci Commun 10(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01645-7

Hu L, Bentler PM (1999) Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ modeling 6(1):1–55

INEI (2024) Condiciones de vida en el Perú. Informe Técnico. Trimestre: Julio-Agosto-Setiembre 2024. Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. https://m.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/boletines/boletin_condiciones_vida_3t24.pdf

Katsantonis IG (2020) Investigation of the impact of school climate and teachers’ self-efficacy on job satisfaction: a cross-cultural approach. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ 10(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe10010011. Article

Kidger J, Stone T, Tilling K, Brockman R, Campbell R, Ford T, Hollingworth W, King M, Araya R, Gunnell D (2016) A pilot cluster randomised controlled trial of a support and training intervention to improve the mental health of secondary school teachers and students – the WISE (Wellbeing in Secondary Education) study. BMC Public Health 16(1):1060. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3737-y

Krys K, Capaldi CA, Zelenski JM, Park J, Nader M, Kocimska-Zych A, Kwiatkowska A, Michalski P, Uchida Y (2021) Family well-being is valued more than personal well-being: a four-country study. Curr Psychol 40(7):3332–3343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00249-2

Lam CF, Spreitzer G, Fritz C (2014) Too much of a good thing: curvilinear effect of positive affect on proactive behaviors. J Organ Behav 35(4):530–546. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1906

Lee ES, Shin Y-J (2017) Social cognitive predictors of Korean secondary school teachers’ job and life satisfaction. J Vocation Behav 102:139–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.07.008

Lee S, Cheong M, Kim M, Yun S (2017) Never too much? The curvilinear relationship between empowering leadership and task performance. Group Organ Manag 42(1):11–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601116646474

Lind JT, Mehlum H (2010) With or Without U? The appropriate test for a U-shaped relationship. Oxf Bull Econ Stat 72(1):109–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.2009.00569.x

Maricuțoiu LP, Pap Z, Ștefancu E, Mladenovici V, Valache DG, Popescu BD, Ilie M, Vîrgă D (2023) Is Teachers’ Well-being associated with students’ school experience? A meta-analysis of cross-sectional evidence. Educ Psychol Rev 35(1):1. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-023-09721-9

Milfont TL, Denny S, Ameratunga S, Robinson E, Merry S (2008) Burnout and wellbeing: testing the Copenhagen burnout inventory in New Zealand teachers. Soc Indic Res 89(1):169–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9229-9

Minedu (2018) Tipología y caracterización de las escuelas privadas en el Perú. Ministerio de Educación, Oficina de Medición de la Calidad de los Aprendizajes

Minedu (2022) El Perú en PISA 2018. Informa nacional de resultados. Ministerio de Educación. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12799/7725

Mizala A, Ñopo H (2016) Measuring the relative pay of school teachers in Latin America 1997–2007. Int J Educ Dev 47:20–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2015.11.014

Nießen D, Groskurth K, Bluemke M, Schmidt I (2020) ZIS Publication Guide (Version 2.1)—Guideline for Documenting Instruments in the Open Access Repository for Measurement Instruments (ZIS). https://doi.org/10.6102/PUBGUIDE2.1.ENGLISH

OECD (2005) Teachers matter. Attracting, developing and retaining effective teachers. OECD Publishing

OECD (2024) Education at a Glance 2024: OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/c00cad36-en

Oishi S, Diener E, Lucas RE (2007) The optimum level of well-being: can people be too happy? Perspect Psychol Sci 2(4):346–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00048.x

Oswald AJ, Proto E, Sgroi D (2015) Happiness and productivity. J Labor Econ 33(4):789–822. https://doi.org/10.1086/681096

Pierce JR, Aguinis H (2013) The too-much-of-a-good-thing effect in management. J Manag 39(2):313–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311410060

Pillemer J, Rothbard NP (2018) Friends without benefits: understanding the dark sides of workplace friendship. Acad Manag Rev 43(4):635–660. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2016.0309

Renshaw TL, Long ACJ, Cook CR (2015) Assessing teachers’ positive psychological functioning at work: Development and validation of the Teacher Subjective Wellbeing Questionnaire. Sch Psychol Q 30(2):289–306. https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000112

Rentería JM (2023a) Inequality of opportunity and time-varying circumstances: longitudinal evidence from Peru. J Dev Stud 59(2):258–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2022.2113067

Rentería JM (2023b) The collateral effects of private school expansion in a deregulated market: Peru, 1996–2019. Int J Educ Dev 102:102855. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2023.102855

Salgado JF, Moscoso S (2022) Cross-cultural evidence of the relationship between subjective well-being and job performance: a meta-analysis. J Work Organ Psychol 38(1):27–42. https://doi.org/10.5093/jwop2022a3

Scanlan D, Savill-Smith C (2021) Teacher wellbeing index 2021. Education Support

Schneider I (2017) Can we trust measures of political trust? Assessing measurement equivalence in diverse regime types. Soc Indic Res 133(3):963–984. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1400-8

See BH, Morris R, Gorard S, El Soufi N (2020) What works in attracting and retaining teachers in challenging schools and areas? Oxf Rev Educ 46(6):678–697. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2020.1775566

Sharif MA, Mogilner C, Hershfield HE (2021) Having too little or too much time is linked to lower subjective well-being. J Personal Soc Psychol 121(4):933–947. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000391

Song H, Gu Q, Zhang Z (2020) An exploratory study of teachers’ subjective wellbeing: understanding the links between teachers’ income satisfaction, altruism, self-efficacy and work satisfaction. Teach Teach 26(1):3–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2020.1719059

Steenkamp J-BEM, Baumgartner H (1998) Assessing measurement invariance in cross-national consumer research. J Consum Res 25(1):78–90. https://doi.org/10.1086/209528

Tenney ER, Poole JM, Diener E (2016) Does positivity enhance work performance?: Why, when, and what we don’t know. Res Organ Behav 36:27–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2016.11.002

Tran KT, Nguyen PV, Dang TTU, Ton TNB (2018) The impacts of the high-quality workplace relationships on job performance: a perspective on staff nurses in Vietnam. Behav Sci 8(12):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs8120109

Vargas JC, Cuenca R (2018) Perú: El estado de políticas públicas docentes. Instituto de Estudios Peruanos. http://repositorio.iep.org.pe/handle/IEP/1121

Wartenberg G, Aldrup K, Grund S, Klusmann U (2023) Satisfied and high performing? A meta-analysis and systematic review of the correlates of teachers’ job satisfaction. Educ Psychol Rev 35(4):114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-023-09831-4

Watkins MW (2022) A step-by-step guide to exploratory factor analysis with Stata. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003149286

Yamamoto J (2017) Un modelo de bienestar subjetivo para Lima Metropolitana. https://tesis.pucp.edu.pe/repositorio//handle/20.500.12404/7682

Yamamoto J, Arevalo MV, Wendorff S (2022) Happiness, underdevelopment, and mental health in an andean indigenous community. En D Danto & M Zangeneh (eds.) Indigenous Knowledge and Mental Health. Springer International Publishing. pp 123–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-71346-1_8

Yamamoto J, Feijoo AR, Lazarte A (2008) Subjective wellbeing: an alternative approach. En Wellbeing and Development in Peru. Palgrave Macmillan. pp 61–101. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230616998_3

Zakariya YF, Bjørkestøl K, Nilsen HK (2020) Teacher job satisfaction across 38 countries and economies: an alignment optimization approach to a cross-cultural mean comparison. Int J Educ Res 101:101573. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101573

Zhang R, Li A, Gong Y (2021) Too much of a good thing: examining the curvilinear relationship between team-level proactive personality and team performance. Pers Psychol 74(2):295–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12413

Zieger L, Sims S, Jerrim J (2019) Comparing Teachers’ job satisfaction across countries: a multiple-pairwise measurement invariance approach. Educ Meas: Issues Pract 38(3):75–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/emip.12254

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Josselin Thuilliez for his close supervision of and interest in this research. We gratefully acknowledge helpful ideas and comments from Rémi Bazillier, Javier Herrera, Marta Menéndez, Gustavo Yamada, Juan Francisco Castro, César Guadalupe, Juan León, and Juan Manuel del Pozo. We also thank comments received at the University of Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne doctoral seminar (January 19, 2021), the Annual Congress of the Peruvian Economic Association (August 13, 2022), the National Seminar of the Peruvian Society for Educational Research (May 20, 2023), the Educational Research Seminar at PUCP (September 21, 2023), and the European Conference on Education (July 09, 2024). Jonatan Amaya provided excellent research assistance. This research was supported by the Economic and Social Research Consortium – CIES (grant N° PI EQU A1-PRI04).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.M.R.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing. D.S.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Data Analysis, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Correspondence to: J.M.R.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study did not require ethical approval because it involved only a secondary analysis of publicly available fully anonymized datasets from the Peruvian Ministry of Education. No new data were collected and no human participants were directly involved.

Informed consent

Informed consent was not applicable to this study, as the analysis was conducted on publicly accessible datasets from the Peruvian Ministry of Education with no identifiable personal information.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rentería, J.M., Solano, D. The parabolic path of teacher well-being and student learning achievement in Peru. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1391 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05736-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05736-5