Abstract

In the intelligent era, technology-supported collaboration has emerged as a vital educational approach, widely implemented in educational practice. However, the extent to which technology-supported collaboration enhances students’ learning outcomes remains uncertain. This paper employs meta-analysis methods to quantitatively analyze 48 empirical articles published over the past decade. The aim is to determine the effectiveness of technology-supported collaboration in improving students’ learning outcomes and the extent of its impact. The findings indicate that: (1) Technology-supported collaboration can enhance student learning outcomes to a certain extent, with an overall effect size at the upper-middle significant level (ES = 0.71, z = 14.36, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.61, 0.80]); (2) Regarding learning outcome dimensions, technology-supported collaboration significantly impacts students’ academic achievement (ES = 0.80, z = 11.34, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.66, 0.94]), while its impact on learning participation (ES = 0.67, Z = 6.82, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.48, 0.87]) and learning attitude (ES = 0.52, z = 5.86, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.35, 0.69]) is moderate; and (3) Group size (Chi2 = 14.07, P < 0.05), intervention duration (Chi2 = 13.83, P < 0.01), and subject area (Chi2 = 25.43, P < 0.05) all positively influence learning outcomes and are significant moderating factors. Based on these findings, recommendations for future academic research and teaching practice are provided to better enhance students’ learning outcomes within the context of technology-supported collaboration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Learning involves not only the acquisition of new knowledge by learners but also the integration into the knowledge community and the construction of meaning through social interaction (Chen et al., 2023). Collaboration is considered an effective learning strategy in socially constructive learning environments, as it can trigger and resolve cognitive conflicts, foster high-quality debates, and thereby achieve deeper understanding and consensus, significantly enhancing learning efficiency (Luo & Zheng, 2024; Xu et al., 2023). However, without appropriate technical support, collaborative interactions in socially constructed learning environments can lead to confusion and unsatisfactory outcomes for students (Liu et al., 2024). Although extensive research has highlighted the theoretical benefits of collaborative learning (Sung & Hwang, 2013; Li & Wang, 2022), and technology-supported advancements have clearly improved the efficiency and quality of group interactions (Sung et al., 2017; Chatterjee et al., 2025), there is insufficient research that connects these improvements directly to measurable learning outcomes—particularly in the context of technology-supported collaboration on students’ learning outcomes. In addition, in terms of theoretical research, many studies focus on the benefits of collaborative learning in the abstract, without examining how various technological tools or platforms influence the dimensions of learning outcomes (e.g., academic achievement, learning attitude, and learning participation). In terms of empirical research, the existing empirical studies often provide broad insights without reaching a consistent conclusion or even reached contradictory conclusions about whether and to what extent technology support collaboration can improve or reduce student learning outcomes (Jiang et al., 2018; Lin, 2020). For example, Liu et al. (2024) proposed a series of pieces of evidence that collaboration supported by technology can enhance learners’ participation, reflection, and dialogue, thereby significantly improving learning outcomes, and Kuo et al. (2012) found that technology-supported collaboration enables students to discuss, explain, question, and reflect on different experiences and ideas in real-life problem situations and develop their meta-cognitive and learning innovation abilities in the process, thereby improving their learning attitudes and knowledge achievements. However, some studies have suggested that technology-supported collaboration does not improve learning outcomes. For instance, Dan and Dong (2022) conducted a quasi experimental study on project-based collaborative learning activities in the English course “Interaction Design” at a university in Nanjing, and pointed out that technology can distract students’ attention during collaboration, thereby increasing their cognitive burden, and Persky and Pollack (2010) studied the learning effectiveness of CSCL in university courses and found that there was no significant difference in academic achievement between technology-supported collaborative learning and traditional classroom learning. Furthermore, several studies have shown that just a few aspects of learning outcomes are positively impacted by technology-supported collaboration. For example, Wang et al. (2022) integrated collaborative cognitive load theory with intelligent technological methods to study online collaborative learning processes and collaborative learning outcomes. They found that technology-supported collaboration positively impacts interactions among learners and increases their interest and motivation in learning, but it does not have a positive effect on their academic performance.

Therefore, there remains a critical gap in understanding the specific impact of technology-supported collaboration on student learning outcomes. This gap is particularly significant because the integration of technology into collaborative learning environments is not a panacea. Technology can introduce new challenges, such as information overload, disengagement, or disjointed communication (Liu et al., 2024; Dan & Dong, 2022), which may undermine the potential benefits of collaboration. Thus, it is crucial to conduct comprehensive and reliable holistic research to provide more robust explanations and determine whether and to what extent technology-supported collaboration can lead to improved or reduced students’ learning outcomes. Of course, the impact of technology-supported collaboration on students’ learning outcomes is just one of the several factors that affect these learning outcomes; other factors that may affect research results are variations in the experimental design itself implemented in various empirical literature (e.g., participants’ cognitive levels, sample size, subject areas, intervention duration, etc). Considering the factors of the experimental design, this study explores the factors that appear in the experimental design as moderating variables and longitudinally compares the impact of technology-supported collaboration on student learning outcomes under the influence of these moderating variables to determine which ones are more significant. By doing so, this study aims to address the following research questions:

Question1: What is the overall effect size of technology support collaboration on students’ learning outcomes, and how does it affect the three dimensions of learning outcomes (i.e., academic achievement, learning attitude, and learning participation)?

Question2: Are there significant differences in the impact effects obtained from the different experimental designs (are the effect sizes heterogeneous)? If there is heterogeneity in the effect size, what factors can explain the differences between research conclusions—that is, how different moderating variables affect the learning outcomes?

Addressing these research questions will not only advance theoretical understanding of collaborative learning in technology-supported environments but also provide practical insights for educators and instructional designers looking to optimize the use of technology in fostering meaningful, outcome-driven collaboration among students.

Literature review

Technology-supported collaboration

Technology-supported collaboration is a core research area in computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL). Its central essence is to place learners at the heart of the learning process, focusing on how technology can create new learning opportunities, including remote collaboration, cross-cultural communication, exploration of personalized learning paths, and enhancing interdependence and individual responsibility among team members (Xu, 2023; Sung & Hwang, 2013). Existing literature has made significant contributions to studying technology-supported collaboration by focusing on two main aspects: the types of supporting technologies and the evaluation methods for their effectiveness. Li and Wang (2022) categorized supporting technologies into three types based on the interaction between technology and learning: “learning space technology,” “enabling technology,” and “learning analytics technology.” Ma et al. (2021), based on the types of technologies used in the collaborative learning process, divided supporting technologies into five dimensions: “network communication technology,” “dynamic presentation technology,” “sharing and co-construction technology,” “digital learning platforms,” and “hardware technology”. These studies tend to view technology as a transformative tool for improving students’ learning outcomes, placing excessive emphasis on its role in the collaborative learning process. This often overlooks the social contexts and instructional factors that influence the effectiveness of collaborative learning, resulting in an oversimplification of the complexities involved in the collaborative learning process. On the other hand, researchers emphasize diverse evaluation perspectives, rich evaluation methods, and the involvement of multiple evaluators when assessing the effectiveness of technology-supported collaborative learning. Methods such as evaluation scales, surveys, and interviews are employed to provide a comprehensive, objective, and accurate assessment of the effectiveness of technology-supported collaborative learning for students (Liu, 2024; Jeong et al., 2019; Fredericks et al., 2016; He et al., 2021). Among these, learning engagement, as a crucial factor reflecting students’ learning process, serves as a measure of learning activities and the degree of student subjectivity, and is an important indicator for evaluating students’ learning effectiveness. It encompasses three dimensions: cognitive engagement, emotional engagement, and behavioral engagement (Xu,2023; Gong et al., 2018). Academic achievement, as a key factor reflecting students’ learning outcomes, is one of the most commonly used indicators for evaluating learning effectiveness and can be measured at multiple levels, such as the quality of artifacts, knowledge tests, research papers, experimental reports, and problem-solving design schemes (Xu et al., 2023; Li & Wang, 2022). Moreover, experimental design in empirical literature can also affect the effectiveness of technology-supported collaborative learning. For instance, differences in participants’ cognitive levels can affect experimental results. Research has shown that lower-grade students have a stronger interest in technology-supported collaboration learning, and their learning outcomes are more significant (Leng & Lu, 2020). The sample size of collaborative groups could influence how well students collaborate when studying using technology tools. Groups with two to four individuals are most suitable for collaborative learning, and small groups cannot outperform large groups in terms of interaction and performance if the size of the group surpasses seven (Schellens & Valcke, 2006; Xu et al., 2023). Different subject areas can also affect learners’ acceptance of technology-supported collaboration. Students with scientific literacy will actively seek technology support to carry out collaborative learning to debate and explain the rationality of problem solving when faced with challenges or unreasonable structures (Kyndt et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2023). The intervention duration of teaching experiments is positively correlated with learning outcomes (Xu et al., 2023).

The impact of technology-supported collaboration on learning outcomes

Technology-supported collaboration has been widely applied in classroom instruction, and several studies have systematically reviewed and meta-analyzed empirical literature on the learning effectiveness of technology-supported environments from various perspectives. Chen et al. (2019) designed a technology-supported teaching interaction strategy based on an analysis of classroom teaching interaction, knowledge types, cognitive goals, and tool support. This strategy includes five types of teaching interaction strategies: technology-supported questioning, problem-solving, peer evaluation, discussion, and collaborative knowledge construction. However, their research did not determine the usefulness of technology-supported collaboration in terms of student learning outcomes, nor did it reveal significant differences in student learning outcomes between different factors affecting technology-supported collaboration. Zhou and Deng (2023) examined the effects of technology-supported teaching interventions on students’ learning outcomes in programming instruction by meta-analyzing 37 empirical research articles published between 2006 and 2022. This study found that technology-supported teaching interventions have a moderate and significant positive impact on students’ learning outcomes, but the technology support in their research was limited to graphical programming tools and game-based programming tools in programming instruction and has not been confirmed in non-programming disciplines. Meanwhile, it is suggested that future research can focus on a specific teaching model (such as project-based teaching or collaborative learning) to explore the promotion effect of technology support on students’ learning outcomes. Ma et al. (2021) explored the effects of CSCL on students’ learning effects in terms of “learning cognition, learning emotion, and learning process” in STEM education by meta-analyzing 142 relevant experimental and quasi-experimental research published in international journals from 2009 to 2019. They found that the application of CSCL in STEM education as a whole helps to improve students’ learning effects, with the most notable benefit being cognitive learning effects. After reviewing the literature, their research proposed a learning effect that includes three dimensions: “learning cognition, learning emotion, and learning process,” and summarized five technology support tools including “communication technology (such as embedded communication, voice communication, etc.), dynamic presentation technology (such as simulation technology, virtual games, augmented reality technology, etc.), sharing and co-construction technology (such as knowledge forums, resource sharing tools, etc.), learning platforms (such as intelligent learning systems, integrated learning environments, etc.), and hardware technology (such as interactive whiteboards, etc.) from 142 relevant experimental and quasi-experimental research results. This provides a research perspective for using CSCL to improve students’ learning effects in subsequent classroom teaching practice. However, its research only focuses on the single perspective of STEM and proposes several strategies for technology support, but it still fails to confirm the effect of collaborating with technology support tools on student learning outcomes.

The above research indicates that although a large body of literature has studied technology-supported collaboration, there is ambiguity and inconsistency regarding its impact on student learning outcomes. Furthermore, there is a lack of empirical data to explain whether and to what extent technology-supported collaboration can improve student learning outcomes. This has led to many teachers being unable to effectively implement technology-supported collaboration to enhance student learning outcomes. Therefore, it is crucial to conduct comprehensive and reliable holistic research to provide more robust explanations and determine whether and to what extent technology-supported collaboration can lead to improved or reduced students’ learning outcomes.

Methods

Meta-analysis is a research method that comprehensively analyzes the empirical data of multiple independent studies on the same research topic as a whole and characterizes its impact effect using the average effect size (ES) of multiple empirical research data. It can also deeply analyze the influence of moderating variables involved in the experimental design on the main effect, providing us with a more comprehensive and in-depth interpretation (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). Additionally, this method allows for the identification of gaps in existing research and provides direction for future studies (Cooper, 2010). This method is particularly suitable for addressing the research questions because it allows for the integration of findings from a large number of studies, providing a more robust and comprehensive understanding of the relationship between technology-supported collaboration and learning outcomes. In this study, we find that the existing empirical studies often provide broad insights without reaching a consistent conclusion or even reached contradictory conclusions about whether and to what extent technology support collaboration can improve or reduce student learning outcomes. Accordingly, this article uses meta-analysis to systematically quantify relevant empirical literature in international journals to determine the effectiveness of technology-supported collaboration in promoting students’ learning outcomes, thereby contributing to academic research and teaching practice.

This study adhered to the rigorous guidelines (such as database searches, identification, screening, eligibility, merging, duplicate removal, and analysis of included studies) of Cooper’s (2010) proposed meta-analysis approach for analyzing quantitative data from several independent studies. Using Rev-Man 5.4, a meta-analysis was conducted on pertinent empirical research that was published in global educational publications in the past decade. Then, Cohen’s kappa coefficients were used to perform consistency tests on the data extracted by the two researchers, and publication bias and heterogeneity tests were performed on the sample data to determine the quality of this meta-analysis.

Data sources and search strategies

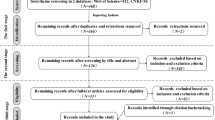

The number of articles included and removed during the selection process based on the statement and research eligibility criteria is displayed in Fig. 1 (See Fig. 1), which illustrates the three stages of the data gathering procedure for this meta-analysis.

Firstly, the Chinese Core source journal, the Web of Science Core Collection journal papers, and the Chinese Social Science Citation Index (CSSCI) source journal papers included in CNKI were the databases that were utilized to methodically search for relevant papers. The reason for choosing these databases is that they are core collection databases published in international and Chinese journals. At the same time, they are also well-known online resources offering scholarly, peer-reviewed content, sophisticated search capabilities, and pertinent literature from reputable scholars and specialists on our topic. The Boolean operators used in Web of Science search strings are “TS = (“learning effect” or “study effect” or “learning outcomes” or “study outcomes” and “pre test” or “post test”) or (“learning effect” or “study effect” or “learning outcomes” or “study outcomes” and “control group” or “quasi experiment” or “experiment”) and (“collaborative” or “collaborative learning” or “cooperative” or “cooperative learning” or “group learning” or “computer-supported collaborative learning” or “CSCL”) and (“technical support” or “technology” or “computer” or “mobile” or “smartphones” or “iPad” or “digital” or “online”).” The research field is “Education and Education Research,” and the search period is from January 1, 2010, to May 20, 2024. A total of 132 papers were obtained. The Boolean operators used in CNKI search strings are “SU = (‘Learning Effect’ * ‘Collaboration’ + ‘Learning Effect’ * ‘Collaborative Learning’ + ‘Learning Effect’ * ‘CSCL’ + ‘Learning Effect’ * ‘Technology’ + ‘Learning Effect’ * ‘Technical Support’ + ‘Learning Effect’ * ‘Based on Technical Support’ + ‘Collaborative Learning’ * ‘Technical Support’ + ‘Collaborative Learning’ * ‘Technical Environment’) and FT = (‘Experiment’ + ‘Quasi Experiment’ + ‘Pre Test’ + ‘Post Test’ + ‘Empirical Research’)” (translated in Chinese during search). During the search period from January 1, 2010, to May 20, 2024, a total of 256 studies were found. Before exporting references to Endnote (a program for managing bibliographic references), all duplicates and retractions were removed from the database. A total of 387 studies were discovered.

Secondly, two researchers reviewed the titles and abstracts of all the articles they had collected, selecting 171 studies in total that fit the meta-analysis’s inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Finally, two researchers carefully went over the whole text of each included article, making sure it met all the inclusion and exclusion criteria. To guarantee comprehensive coverage of the papers, a snowball search was conducted utilizing the listed articles’ references and citations. 48 pieces were retained in the end.

This entire process was carried out by two researchers working together, and following discussion and negotiation to elucidate any growing disagreements. If a consensus could not be reached initially, a third senior researcher was consulted to provide an independent assessment and facilitate resolution. This structured approach led to a consensus rate of ~94.7%, ensuring the reliability and consistency of the study selection process.

Eligibility criteria

The following eligibility criteria were created for both inclusion and exclusion because not all of the retrieved papers satisfied the criteria required for this meta-analysis:

-

(1)

The included studies’ publishing languages were restricted to English and Chinese, and the complete text was available. Excluded from consideration were articles not published between 2010 and 2024 and those that did not adhere to the publication language.

-

(2)

The included papers’ research designs must be quantitative, empirical, and able to evaluate how technology support collaboration affects learning outcomes. Review and theoretical publications were excluded because they were unable to assess the effect of technology support collaboration on learning outcomes.

-

(3)

The included studies’ research methods must contain a quasi-experiment, a natural experiment, or a randomized control experiment with high internal validity and a strong experimental design and be able to provide reasonable evidence to prove the causal relationship between technology support collaboration and learning outcomes. Articles using only observational research methods or non-experimental research methods were not included.

-

(4)

The research topic must focus on the impact of technology-supported collaboration on learning outcomes; in other words, a particular technology tool must be employed to encourage collaborative learning outcomes or include collaborative elements in the experimental process.

-

(5)

The included papers’ research results must offer specific indicators (such as sample size, mean value, or standard deviation) that can be used to measure the learning outcomes. The articles that were unable to determine the effect size or lacked particular measurement indicators for learning outcomes were eliminated.

Data coding design

Meta-analysis requires extracting key information from literature and encoding its features to convert descriptive data into quantitative data. Using the experimental variables included in the 48 meta-analysis literature, this study builds a literature feature value coding table (see Table 1) with 15 coding fields, including “descriptive information, variable information, and data information,” based on the CSCL meta-analysis coding framework put forth by Jeong et al. (2019).

The descriptive information contained the following basic details about the papers: the author, serial number, publishing year, and paper title.

The variable information mainly records three variables within the experimental design, including independent variables (intervention strategy), dependent variables (learning outcomes), and moderating variables (learning stage, group size, intervention duration, collaborative field, technical tool, and subject area). Due to the focus of this study on determining whether and to what extent technology-supported collaboration can affect student learning outcomes, intervention strategies are used as independent variables in this study and encoded as technology-supported collaboration and non-technology-supported collaboration. Using learning outcomes as the dependent variable in this study and referring to the research findings of Jeong et al. (2019) and Xu (2023), learning outcomes were coded into three dimensions: academic achievement, learning attitude, and learning participation. Among them, academic achievement refers to the cognitive level of understanding, analyzing, and applying knowledge primarily through testing or artificial products; learning attitude refers to the non-cognitive level of learning motivation, self-efficacy, perceived satisfaction, and usefulness evaluated subjectively; and learning participation refers to the behavioral interaction level of interactive participation and perception among members evaluated through behavioral interaction. The connection between the independent and dependent variables will be influenced by the moderating variables to some degree. As a result, the experimental design variables found in the 48 papers were categorized and combined into 6 moderating variables (see Table 1), where learning stages were encoded as primary school or lower, middle school, high school, and university or above; group sizes were coded as follows: 2–3 people, 4–6 people, 7–10 people, and more than 10 people; intervention duration was encoded as 0–1 weeks, 1–4 weeks, 4–12 weeks, and more than 12 weeks; The collaborative fields were encoded as formal environments (such as school classrooms) and informal environments (such as outdoor or museum environments); Technical tools were classified based on the specific technical tools used in the literature and coded into five dimensions: network communication technology, dynamic presentation technology, shared and co-built technology, digital learning platforms, and hardware technology. The subject areas were coded based on the specific discipline used in the literature.

The data information includes three indicators that can measure learning effectiveness: sample size, mean, and variance (see Supplementary Table S1). This indicator is mainly used to calculate the magnitude of the effect value, which is the standardized mean difference (SMD) between the pre-post tests of a single-group experiment or the comparison groups of a two-group experiment. This study used the SMD calculation formula proposed by Morris (2008):

Among them, \(\bar{{x}_{1}}\) and \(\bar{{x}_{2}}\) respectively represent the mean of the pre-test or comparison group, \({s}_{1}\) and \({s}_{2}\) respectively represent the standard deviation of the pre-test or comparison group, \({n}_{1}\) and \({n}_{2}\) respectively represent the sample size of the pre-test or comparison group.

Procedure for extracting and coding data

Two researchers extracted information from the papers according to the data encoding table (see Table 1) and recorded it in Excel (see Supplementary Table S1). Each study’s results were extracted independently if the same outcome variable was measured differently in a study or if an article included many studies. For instance, Watson et al. (2020) used three cognitive testing tools to measure academic achievement, and the various measurement values of academic achievement were considered as three independent studies; Balestrini et al. (2014) included two outcome variables, “academic achievement and learning attitude,” which are also considered two separate studies. After the data extraction was done, the consistency test coefficient of the two researchers was 94.7%, and a consensus was established through debate and negotiation. If a consensus could not be reached initially, a third senior researcher was consulted to provide an independent assessment and facilitate resolution. Supplementary Table S2 provides a detailed list of the key features of 48 included articles with 125 effect sizes, including descriptive information (such as publication year, author, serial number, and paper title), variable information (such as independent, dependent, and moderating variables), and data information (such as mean, standard deviation, and sample size). Data analysis was then carried out based on the results of testing the sample data’s heterogeneity and publication bias using the RevMan 5.4 tool.

Publication bias test

If the sample literature studied cannot represent the entire research in the field, it is considered that there is publication bias in the study, which will limit the accuracy and reliability of the meta-analysis. Thus, it is especially crucial to perform publication bias testing in advance of meta-analysis (Stewart et al., 2006; Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). A common instrument for testing publication bias is funnel plots, which use the effect value as the x-axis and the standard error of the effect value as the y-axis. It can clearly and intuitively show whether the sample data is concentrated in the upper region and equally dispersed on both sides of the average effect value. If so, the possibility of publication bias is extremely low. The data in this study’s funnel plot, which is displayed in Fig. 2 (See Fig. 2), is uniformly distributed within the upper effective region, demonstrating the validity of the meta-analysis samples and a low probability of publication bias.

Heterogeneity test

Heterogeneity refers to the degree of variation among all the study samples included in a meta-analysis (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). In practical research, heterogeneity can arise from factors such as differences in study design (e.g., quasi-experiments, randomized controlled trials, etc.), the diversity of supporting technologies (e.g., different types of educational software or platforms), as well as cultural backgrounds and sample differences (e.g., variations in grade levels, geographic regions, etc.). While some studies have standardized their measurement indicators, others have used non-standardized assessments, which can affect the magnitude of observed effect sizes within the same topic. Therefore, in meta-analysis, the I² value is commonly used to judge the degree of sample heterogeneity. It is generally believed that when I² ≥ 50%, a random effects model should be used for moderate to high heterogeneity; otherwise, a fixed effects model should be applied (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). Although the random effects model provides a more robust correction by addressing heterogeneity, the various factors contributing to heterogeneity suggest that the results of the analysis may not be fully generalizable across all contexts. Therefore, subgroup analyses are needed to identify the specific sources of heterogeneity and to further deepen the interpretation of this variation. The heterogeneity test results of the sample effect size can be used for research to choose an appropriate effect model. The study’s heterogeneity test results indicated (See Table 2) that I2 = 73% and that there was considerable heterogeneity (p < 0.001); therefore, to guarantee the scientific and trustworthy analysis results, the total effect size should be calculated using a random effects model. At the same time, to better explain the impact of technology-supported collaboration on student learning outcomes, further subgroup analysis of variables that may generate heterogeneity in the 48 meta-analysis articles is still needed.

Results

The results of the whole effect size analysis

This meta-analysis selected the random effect model to examine 125 effect sizes from 48 studies based on the heterogeneity test results and obtained the overall effect size forest plot (See Fig. 3). In accordance with Cohen’s (1992) effect size rating standard (effect sizes greater than or equal to 0.8 are significant effects, between 0.2 and 0.8 are moderate effects, and below 0.2 are mild effects), the results of this meta-analysis indicate that the combined effect size of technology-supported collaboration on students’ learning outcomes is 0.71 and has a significant level of upper-middle (z = 14.36, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.61, 0.80]), providing data support for the conclusion that technology-supported collaboration is an effective factor in promoting student learning.

Furthermore, this study also examined three different dimensions that affect learning outcomes in order to better understand the specific impact of technology-supported collaboration on student learning outcomes. The results showed that (See Table 3): technology-supported collaboration has a positive impact on different dimensions of learning outcomes (ES is greater than 0), which improves students’ academic achievement (ES = 0.80), learning attitude (ES = 0.52), and learning participation (ES = 0.67) to a certain extent, but there is no significant difference between groups (chi2 = 6.08, P > 0.05). Although there is no significant difference in the degree of influence of technology-supported collaboration on different types of learning outcomes, the data from this study indicate that its impact on learning achievement is at a moderate to high level of significant influence (ES = 0.80, z = 11.34, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.66, 0.94]), while its impact on learning participation (ES = 0.67, z = 6.82, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.48, 0.87]) and learning attitude (ES = 0.52, z = 5.86, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.35, 0.69]) is only at a moderate level of influence.

The results of the moderator effect size analysis

The two-tailed test of 125 effect quantities revealed substantial heterogeneity in the overall forest plot (I2 = 79%, z = 14.36, p < 0.001), indicating the presence of moderating variables that may be related to factors other than sampling error that influence learning outcomes. To further explore the key factors that affect learning outcomes, this meta-analysis conducted subgroup analyses on the six moderating variables included in the experimental design of the 48 included articles, including “learning stage, group size, intervention duration, collaborative field, technical tool, and disciplinary fields.” The overall forest plot showed that there was significant heterogeneity in the two-tailed test of 125 effect sizes (I2 = 79%, z = 14.36, p < 0.001), indicating that there are moderating variables that can be attributed to factors other than sampling error that affect learning outcomes. To further explore the key factors that affect learning outcomes, this meta-analysis conducted subgroup analyses on the six moderating variables included in the experimental design of the 48 included articles, including “learning stage, group size, intervention duration, collaborative field, technical tool, and disciplinary fields.” The results showed that (See Table 4): different moderating variables can positively affect students’ learning outcomes, among which group size (Chi2 = 14.07, P < 0.01), intervention duration (Chi2 = 13.83, P < 0.01), and subject area (Chi2 = 25.43, P < 0.01) have significant differences in inter-group effects and can all be considered key moderating factors that affect learning outcomes in a technology-supported collaborative learning environment. However, there was no significant difference in the inter-group effects of learning stage (Chi2 = 6.68, P = 0.08 > 0.05), technical tool (Chi2 = 3.14, P = 0.07 > 0.05), and collaborative field (Chi2 = 3.17, P = 0.06 > 0.05). Therefore, we are unable to clearly explain the significance of these three elements for promoting students’ learning outcomes in the context of technology-supported collaboration. These are the specific results, which are as follows:

-

(1)

Different learning stages have a positive impact on the collaborative learning effect of technology support, and there is no significant difference in inter-group effects (Chi2 = 6.68, P = 0.08 > 0.05). The order of effect size values is university or above (ES = 0.79, P < 0.01), primary school or lower (ES = 0.62, P < 0.01), high school (ES = 0.46, P < 0.01), and middle school (ES = 0.36, P < 0.01). These findings indicate that, even if the learning stage has a positive impact on learners’ learning outcomes, we are unable to explain why it is crucial for fostering learners’ learning outcomes in the context of technology-supported collaboration. Furthermore, university or above accounts for 64.8% of all empirical studies conducted by researchers; all things considered, university or above has the largest comprehensive effect size, suggesting that this may be the ideal learning stage for cultivating learning outcomes in the context of technology-supported collaboration.

-

(2)

Different group sizes have a positive impact on the collaborative learning effect of technology support, with significant differences in inter-group effects (Chi2 = 14.07, P < 0.05). In this case, the 2–3 person group had the largest overall effect size (ES = 0.79, P < 0.01), followed by the 7–10 person group (ES = 0.66, P < 0.01) and the 4–6 person group (ES = 0.59, P < 0.01), all of whom had medium-to-higher levels of impact. When the group size exceeded 10, learning outcomes improved at a lower-middle level (ES = 0.37, P < 0.01). These findings indicate that group size has a negative relationship with the influence on learning outcomes and that the impact decreases with group size.

-

(3)

Different intervention durations have a positive impact on the collaborative learning effect of technology support, with significant differences in inter-group effects (Chi2 = 13.83, P < 0.01). With an increase in intervention duration, the effect sizes corresponding to this factor showed an upward trend. Learning outcomes improved to an upper-middle level (ES = 0.67, P < 0.01) following an intervention duration lasting more than 13 weeks. Based on this finding, the effect of learning outcomes is positively connected with the length of the intervention duration; that is, the longer the intervention duration, the greater the effect size.

-

(4)

The collaborative field has a positive impact on the collaborative learning effect of technology support, and there is no significant difference in inter-group effects (Chi2 = 3.17, P = 0.06 > 0.05). The informal collaborative field had the highest effect size rating (ES = 0.86, P < 0.01), followed by the formal collaborative field (ES = 0.57, P < 0.01). This result shows that while the collaborative field improves learning outcomes, it cannot be considered the main factor influencing learning outcomes in the context of technology-supported collaboration. Additionally, researchers are more likely to conduct empirical studies in formal environments, such as classrooms (which account for 85.6% of all studies conducted); on the other hand, informal environments, such as outdoor spaces or museums, have the highest comprehensive effect sizes, suggesting that it is possible to appropriately carry out technology-supported collaborative learning in an informal collaborative field.

-

(5)

Different technological tools have a positive impact on learning outcomes without significant differences in inter-group effects (Chi2 = 3.14, P = 0.07 > 0.05). The dynamic presentation technology (ES = 1.01, P < 0.01) and shared and co-built technology (ES = 0.87, P < 0.01) demonstrated a high degree of significant effect; the digital learning platform (ES = 0.75, P < 0.01) achieved a medium-upper degree of impact; the network communication technology (ES = 0.52, P < 0.01) and the hardware technology (ES = 0.49, P < 0.01) were only connected to a lower-medium degree of effect. These findings indicate that, even if the technological tool has a positive impact on learners’ learning outcomes, we are unable to explain why it is crucial for fostering learners’ learning outcomes in the context of technology-supported collaboration. Furthermore, the dynamic presentation technology (e.g., simulation technology, virtual games, AR/VR, etc.) and the shared and co-built technology (e.g., knowledge forums, resource sharing tools, etc.) have the largest comprehensive effect size, suggesting that these may be the ideal technical tools for cultivating students’ learning outcomes in the context of technology-supported collaboration.

-

(6)

Different subject areas have a positive impact on the collaborative learning effect of technology support, with significant differences in inter-group effects (Chi2 = 25.43, P < 0.05). Education (especially in educational technology) had the greatest overall impact, achieving a significant level of effect (ES = 0.92, P < 0.01), followed by medical science (ES = 0.85, P < 0.01) and science (ES = 0.82, P < 0.01), both of which also achieved a significant level of effect. Other fields (such as language and art) were the least effective (ES = 0.33, P < 0.01), only having a medium-low degree of effect compared to English (ES = 0.60, P < 0.01), math (ES = 0.54, P < 0.01), computer (ES = 0.51, P < 0.01), and Chinese (ES = 0.47, P < 0.01). These results suggest that the technical disciplines fields (e.g., education technology, medical science, and science) may be the most effective subject areas for cultivating students’ learning outcomes in the context of technology-supported collaboration.

Discussion

Based on the results of the meta-analysis, this study has obtained quantitative evidence on the overall effects of computer-supported collaborative learning (CSCL) and its moderating factors. To ensure alignment with the research questions, the subsequent sections will provide an in-depth discussion centered around the Question 1 (the overall effects of CSCL on student learning outcomes and their three-dimensional differences) and Question 2 (whether experimental design variables contribute to effect size heterogeneity and their critical moderating roles). This discussion integrate existing theoretical frameworks to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and research limitations, thereby offering specific practical implications and recommendations.

The overall effectiveness of technical-supported collaboration on students’ learning outcomes proposed in Question 1

Technology-supported collaboration has become an important learning method in the intelligent era and is widely adopted in the field of education. Although there have been some studies on whether and to what extent technology-supported collaboration can improve or reduce students’ learning outcomes, there is no consistent research conclusion or even contradictory conclusions (e.g., Liu et al. 2024, Dan and Dong 2022, Persky and Pollack 2010), but the results of this meta-analysis further confirm the positive role of collaboration supported by technology in promoting students’ learning outcomes as a whole and also verify its enhancement effect on three specific learning outcomes, such as academic achievements, learning attitude, and learning participation. Previous studies have shown that providing personalized and timely feedback for learners’ collaborative learning through technology-supported methods in teaching practice can promote students’ participation and interaction quality, facilitate teachers’ presence and guidance feedback, and enhance the level of collaborative knowledge construction among groups (Li & Wang, 2022; Nokes et al., 2015; Luo & Zheng, 2024), thereby resolving conflicts among subjects in a socially constructed learning environment and leading to high-quality and deep-level learning outcomes (Stahl et al., 2006; Tsuei, 2011). This paper gives consistent statistical support for the research perspectives discussed above, confirming that “technology-supported collaboration” is an effective factor in boosting students’ learning outcomes. Therefore, the meta-analysis’s findings not only successfully respond to the initial research question about the overall impact of promoting learning outcomes and its effect on the three dimensions of learning outcomes (i.e., academic achievements, learning attitude, and learning participation) through the use of technology-supported collaboration approach but also boost our belief in promoting students’ learning outcomes by using technology-supported collaboration.

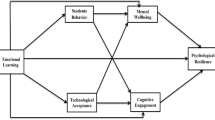

Additionally, while the concomitant increases in learning participation and attitude are only somewhat better, the associated improvements in academic achievements are substantially stronger. According to certain studies, academic achievements differ from learning attitudes and learning participation in school education. Academic achievement is regarded as an important criterion for students’ knowledge level and teachers’ teaching quality, and it receives special attention from teachers, students, and parents. The pursuit of academic achievement has become the most concerning teaching goal for both teachers and students (Xu et al., 2023; Huang, 2023; Wu et al., 2023). However, in the practice of collaborative learning supported by technology, due to the lack of design for learning attitude and learning participation activities, there are a large number of spurious collaborations in teaching activities, which to some extent affect students’ learning attitude and participation behavior (Xu, 2023; Strijbos et al., 2004; Lin, 2020). This finding is consistent with the research results of Jeong et al. (2019) and Ma et al. (2021), both of which found that there are differences in the impact of CSCL on students’ cognitive, emotional, and process learning effects and that the impact on emotional learning effects is the smallest. Therefore, we should strengthen the design of learning attitude and learning participation goals and activities in the collaborative learning process supported by technology so that students can release positive learning attitudes such as a sense of accomplishment and happiness during the activity experience, which in turn induces active participation in learning behavior, thus helping to achieve academic achievement goals (Wang et al., 2022; Liu et al., 2024). Effective collaboration with technology can reduce the cognitive burden of learners, thereby regulating their learning attitude and learning participation towards academic achievement in the context of technology-supported collaboration. Specifically, on the one hand, members of collaborative groups can actively participate in learning with the support of technology tools, which can enhance their self-efficacy in problem-solving, thereby releasing positive learning attitudes such as a sense of accomplishment and happiness, thus achieving high levels of academic achievement; on the other hand, members of collaborative groups can induce positive learning attitudes such as a sense of competition and accomplishment with the support of technology tools, and achieve positive learning participation behaviors through knowledge construction, collaborative argumentation, etc., thus achieving high levels of academic achievement; of course, high levels of academic achievement will stimulate students’ positive participation behavior and generate emotional experiences such as self-efficacy.

It is evident that technology-supported collaboration affects not only the learning outcomes as a whole but also their three specific dimensions, and this study illuminates the complex relationships that exist between academic achievements, learning attitude, and learning participation with regard to these three dimensions of learning outcomes. Future empirical studies should focus more on learning attitude and learning participation in order to completely develop students’ learning outcomes.

The moderating effects of technical-supported collaboration with regard to learning outcomes proposed in Question 2

As part of the meta-analysis, this study conducted subgroup analysis on the six types of moderating variables included in the experimental design of the 48 included papers to further investigate the critical elements influencing learning outcomes. The results showed that different moderating variables can positively affect students’ learning outcomes, with significant differences between groups in terms of group size, intervention duration, and subject area, all of which can be considered as key moderating factors affecting learning outcomes in a technology-supported collaborative learning environment. However, there were no significant differences in the effects between the groups of learning stage, technical tool, and collaborative field. As a result, we are unable to clearly explain the significance of these three elements for promoting students’ learning outcomes in the context of technology-supported collaboration.

Regarding the learning stage, different learning stages had an upper-middle-level effect on learning outcomes without a significant inter-group difference, indicating that we cannot adequately explain why it is essential to support the development of learning outcomes in the context of technology-supported collaboration. As stated in the study by Xu et al. (2023), “students’ cognitive characteristics vary depending on the learning stage, but this difference is reflected in the effectiveness of learning content and collaborative task design.” Therefore, the moderating variables of experimental design in each learning stage, such as group size, intervention period, and technical tools, may be more important for improving the effectiveness of technology-supported collaborative learning. On the other hand, in this meta-analysis, research in higher education accounts for 64.8% of all empirical studies included and has the highest overall effect value, indicating that researchers prefer to conduct technology-supported collaborative learning in universities. Future studies are necessary to fully understand this phenomenon, which could be associated with students’ cognitive growth.

In terms of group size, a collaborative group of 2–3 people has the best impact, which is consistent with earlier CSCL research findings that a group of three or four members is the most appropriate (Xu et al., 2023). However, the results of this meta-analysis did not reflect that “small groups can produce better interaction and performance than large groups” (Schellens & Valcke, 2006; Liu et al., 2024), which could be attributed to the fact that technology-supported collaboration is not limited by physical distance. Whether it is face-to-face collaboration or remote collaboration, the frequency and effectiveness of interaction among group members can be improved, and even a collaboration group with more members can increase the diversity of perspectives with the support of technology tools, which is helpful for improving overall learning effectiveness.

Regarding the intervention duration, different intervention durations have varying effects on learning outcomes, and the longer the intervention duration, the greater the effect size of the intervention duration. Thus, on the whole, the intervention duration has a positive correlation with learning outcomes. This is consistent with the findings of several studies, which state that “CSCL needs to last for more than 1 week or even several weeks to achieve beneficial learning outcomes” (Resta & Laferriere, 2007; Hu & Liu, 2015). An interesting finding in this meta-analysis is that when the intervention duration is less than one week, the effect size is the highest, indicating that due to the influence of technological novelty and peer novelty in the early stages of teaching experiments, there is a “Hawthorne effect” that overestimates the actual teaching effectiveness (Fox et al., 2008). In other words, a new technology is only loved and concerned about because it is new, but when the intervention time exceeds a certain range (such as one week), the degree of influence on learning outcomes is positively correlated with the intervention length. This result can also better explain the contradictions in the research results of Persky and Pollack (2010) and Liu (2024). Therefore, in long-term collaborative learning courses with technology support, appropriate technological updates and innovative teaching methods are needed to avoid the influence of the “Hawthorne effect” on learners’ real learning outcomes.

In terms of collaborative fields, different collaborative fields have a positive impact on learning outcomes without a significant inter-group difference, indicating that we cannot adequately explain why it is essential to support the development of learning outcomes in the context of technology-supported collaboration. Despite this, research on formal collaborative fields accounts for 85.6%, while research on informal fields such as outdoor and museums accounts for only 14.4%, but it has the highest effect on learning outcomes. As stated in the study by Uzunbylu et al. (2009), “The environment of informal fields that is not limited by time and location creates a sense of novelty for learners, which can better promote discussion and group exploration between students and peers, resulting in positive cognitive understanding and learning attitudes.” Therefore, although technology-supported collaboration occurs more in formal collaborative fields (such as classrooms), teachers should encourage or try to carry out immersive collaboration based on informal collaborative fields (such as museums and local projects) to stimulate learning motivation and interest.

Regarding the technical tools, all five types of supportive technical tools have a positive impact on the effectiveness of collaborative learning, which is consistent with the research conclusion that “technical tools can improve the learning effectiveness of CSCL” (Ma et al., 2021). It is worth noting that there are no variations in the inter-group effects; we cannot adequately explain why it is essential to support the development of learning outcomes in the context of technology-supported collaboration. Therefore, any tool that can enhance the interdependence among members of collaborative learning groups and promote high-level negotiation and construction can support students’ collaborative learning and influence the final learning outcome, which does not vary depending on the supporting technology. This result is consistent with Clark’s (1994) view that media and their attributes only affect the cost or speed of learning, whereas fundamentally different technology tools have no significant impact on learning outcomes.

In terms of subject area, education (especially educational technology), medicine, and science (including physics, chemistry, biology, and nature) have a greater impact on learning outcomes, which is consistent with the findings of Kyndt et al. (2013), who found that technology-supported collaboration has significant advantages in areas such as scientific inquiry. It can not only break through the limitations of traditional classrooms and achieve greater communication and dialogue but also bring scientists, parents, community members, and others outside the classroom into inquiry learning negotiation and communication activities, thereby improving the efficiency of negotiation and communication in the process of inquiry learning as well as the effectiveness of collaborative inquiry learning. Despite this, technology-supported collaboration has also had a positive impact in other subject areas, with significant differences between groups, indicating that technology has been widely applied and positively influenced in certain subject areas. Even though distinct subject areas may have different needs and purposes for technology, technology support can provide new tools and methods for certain subject areas, promote the dissemination and exchange of knowledge, and improve collaborative communication and problem-solving skills.

Limitations

This meta-analysis has some limitations, but they can be addressed in further studies. First, because only English and Chinese were allowed as search languages, it’s possible that relevant studies published in other languages were missed, leaving an insufficient number of papers for review. Second, some information supplied by the included studies is lacking, such as whether or not teachers and students received training on how to use technical tools and the variations in learning outcomes between students of different ages and genders. Third, this meta-analysis had a time limit since, as is common with review papers, more studies were published throughout the process of doing it. As pertinent information continues to emerge, more studies addressing these topics are important and extremely relevant.

Teaching suggestions for implementing technical-supported collaboration

According to this meta-analysis, technology-supported collaboration is an effective factor in promoting students’ learning outcomes. In order to more effectively enhance the learning outcomes of dimensions such as academic achievement, learning attitude, and learning participation, the following suggestions are offered in addition to what has been mentioned in the prior discussion:

-

(1)

Teachers should pay attention to the two core elements of “technology support and collaborative interaction” in carrying out teaching applications. Technical-supported collaboration can not only boost the efficiency and quality of learner interaction, promote teacher presence and guidance feedback, and facilitate in-depth explanation and timely correction among groups but are also crucial for resolving conflicts among subjects in a socially constructed learning environment and triggering high-quality and deep-level learning effects. Therefore, teachers must pay special attention to the two core elements of technology support and collaborative interactions, design collaborative problem-solving tasks that are directed towards real-world task situations with the support of technology, and encourage students to effectively engage in social collaboration such as discussion, negotiation, questioning, and debate using technology tools in the context of technology-supported collaboration. They can reach consensus on issues within the field and form solutions, thereby promoting learners’ mastery of domain knowledge and the development of thinking skills.

-

(2)

Teachers should establish collaborative fields with technology-support in real-world situations and carry out long-term teaching interventions. The purpose of learning is not to acquire knowledge but to solve problems in real-world learning situations. However, the knowledge students get in formal fields such as schools is often fragmented and disconnected from real-life situations, and it cannot be applied to solve problems in real and rich learning situations. In addition, learning outcomes, as a comprehensive key ability, are difficult to meaningfully improve in a short intervention period. On the contrary, it can be cultivated through ongoing instruction and the gradual accumulation of knowledge over time. Therefore, teachers should design complex and ill-structured problems based on real-life situations that involve multidisciplinary knowledge over the long term, and provide specific technological support scaffolds for extended teaching practices, in order to encourage students to engage in social collaboration through technology, discuss issues, share perspectives, and engage in critical debates.

-

(3)

Teachers should explore emerging technologies and enhance the design of technology-support collaborative learning environments. While emerging technologies such as generative artificial intelligence and virtual reality can create rich collaborative learning environments and provide new ways to enhance student interaction, engagement, and personalized learning experiences, they are not inherently designed for collaborative learning contexts. As prominent outcomes of artificial intelligence development, these technologies are often not specifically tailored to foster collaboration learning. Therefore, teachers should carefully consider the characteristics of the subject area and the type of knowledge being taught in their instructional practices, and design and present diverse collaborative interaction environments. These environments should offer multimodal interactive support that aligns with students’ emotional communication and knowledge learning needs. This approach will help students, with the support of emerging technologies, to clearly articulate social phenomena, knowledge concepts, and abstract logic, while also preventing learners from becoming overly immersed in the novelty effects of new technologies, which could lead them to neglect a focused engagement with the content knowledge.

Conclusions

This study focuses on two core research questions, aiming to address the issue of how well technology-supported collaboration promotes students’ learning outcomes, which has not received adequate attention in previous studies. The contribution of this study lies in its comprehensive quantitative analysis, systematically synthesizing 48 empirical articles published in international journals over the past decade, using meta-analysis methods, encompassing a total of 9449 samples and 125 effect sizes. The following conclusions can be drawn:

-

(1)

Regarding question 1, the meta-analysis results confirm that: Technology-supported collaboration can promote students’ learning outcomes to a certain extent, and the overall effect is at the upper-middle significant level, with a significant overall effect size (ES = 0.71, z = 14.36, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.61, 0.80]). With respect to the dimensions of learning outcomes, technology-supported collaboration has a positive impact on learning outcomes across different dimensions (ES > 0), but there is no significant difference between inter-groups (chi2 = 6.08, P > 0.05). It can significantly and effectively raise students’ academic achievement (ES = 0.80, z = 11.34, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.66, 0.94]) with a moderate to high level of significant impact, while the improvement of learning participation (ES = 0.67, Z = 6.82, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.48, 0.87]) and learning attitude (ES = 0.52, z = 5.86, P < 0.01, 95% CI [0.35, 0.69]) is only at a middle level of impact.

-

(2)

Regarding question 2, through subgroup analysis, it was found that: There are different degrees of positive effects on students’ learning outcomes from all six moderating variables, which were identified across 48 studies. The group size (Chi2 = 14.07, P < 0.05), the intervention duration (Chi2 = 13.83, P < 0.01), and the subject area (Chi2 = 25.43, P < 0.05) all positively affect learning outcomes and could be seen as significant moderating factors that influence the development of how well technology-supported collaboration promotes students’ learning outcomes in this context. However, the learning stage (Chi2 = 6.68, P = 0.08 > 0.05), the technological tools (Chi2 = 3.14, P = 0.07 > 0.05), and the collaborative field (Chi2 = 3.17, P = 0.06 > 0.05) did not show significant inter-group differences, making it unclear why these factors are important for achieving learning outcomes in the context of technology-supported collaboration.

In summary, this study systematically answered two research questions through meta-analysis, providing empirical evidence for optimizing technology-supported collaborative learning. The study not only confirms the positive impact of technology-supported collaborative learning on enhancing student learning outcomes but also specifically analyzes the variability of this influence across different dimensions, including academic achievement, learning attitude, and learning participation. Furthermore, it explores six moderating variables affecting learning outcomes (learning stage, group size, intervention duration, collaborative field, technical tools, and subject areas), identifying group size, intervention duration, and subject area as key moderators of student learning effectiveness. This research provides more targeted recommendations for educational practices in these areas, offering a new perspective for understanding and optimizing technology-supported collaborative learning environments.

Future research could continue to explore new methods provided by emerging technologies, such as generative artificial intelligence, to enhance collaborative interaction, engagement, and personalized learning experiences. Additionally, training programs for teachers and students on using technology to support and enhance learning outcomes should be developed, as this would help in understanding how technology-supported collaboration impacts students’ learning outcomes. Furthermore, longitudinal studies could be conducted to examine the long-term effects of technology-supported collaboration on student learning outcomes. Long-term data would provide deeper insights into how the sustained use of technology in collaborative learning environments influences students’ learning outcomes and skill development.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included within the article and its supplementary information files or contact the first author of this article to obtain the original data.

References

Balestrini M, Hernandez-Leo D, Nieves R (2014) Technology-supported orchestration matters: outperforming paper-based scripting in a jigsaw classroom. Learn Technol 01(07). https://doi.org/10.1109/TLT.2013.33

Chen BL, Zhang Y, Yang B, Fan FL, Guo Q, Zhou PH (2019) Teaching interaction strategies supported by technology promote in-depth research on interaction. China’s Electron Educ 391(08):99–107

Chen MH, Agrawal S, Lin SM, Liang WL (2023) Learning communities, social media, and learning performance: transactive memory system perspective. Comput. Educ 203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2023.104845

Chatterjee A, Barton J, Kuri A, Round J. (2025) Chat-GPT and collaborative learning: the propagation of misinformation?. Med Teacher 1-1. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2025.2458806

Clark RE (1994) Media will never influence learning. Educ Technol Res Dev 42(2):21–29. https://doi.org/10.2307/30218684

Cohen J (1992) Quantitative methods in psychology: a power primer. Psychol Bull 112(1):115–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155

Cooper H (2010) Research synthesis and meta-analysis: A step-by-step approach, 4th edn. London, England, Sage (2010)

Dan MX, Dong Y (2022) Research on the influencing factors of cognitive load in project-based collaborative learning. Modern Dist Educ 201(03):55–62. https://doi.org/10.13927/j.cnki.yuan.2022042.001

Fox N, Brennan J, Chasen S (2008) Clinical estimation of fetal weight and the Hawthorne effect. Eur J Obst Gynecol Reprod Biol. 141(2):111–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2008.07.023

Fredricks JA, Filsecker M, Lawson MA (2016) Student engagement, context, and adjustment: addressing definitional, measurement, and methodological issues. Learn Instruct 43:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.02.002

Gong CH, Li Q, Gong Y(2018) Research on learning engagement in smart learning environment Res Electr Educ 39(06):83–89. https://doi.org/10.13811/j.cnki.eer.June14.2018

He WT, Liang C, Pang XH, Lu L(2021) The dilemma and solution of designing collaborative learning activities. Res Electr Educ 42(03):103–110. https://doi.org/10.13811/j.cnki.eer.2021.03.015

Huang YS (2023) Heterogeneity research on the impact of learning motivation and self-confidence on academic achievement among urban and rural junior high school students. Shanghai Educ Res 02:43–50. https://doi.org/10.16194/j.cnki.31-1059/g4.2023.02.006

Hu WP, Liu J (2015) Cultivation of pupils’ thinking ability: a five-year follow-up study. Psychol Behav Res 13(05):648–654. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.16720628.2015.05.010

Jeong H, Hmelo-Silver CE, Jo K (2019) Ten years of computer-supported collaborative learning: a meta-analysis of CSCL in STEM education during 2005-2014. Educ Res Rev 28:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.100284

Jiang LF, Duan YS, Oswaldo M, Li WT, Gong Q, Zhou WG (2018) Research on cross-border online collaborative learning models. Modern Educ Manag 339(6):96–102

Kuo FR, Hwang GJ, Lee CC (2012) A hybrid approach to promoting students’ web-based problem-solving competence and learning attitude. Comput Educ 58(1):351–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.09.020

Kyndt E, Raes E, Lismont B, Timmers F, Cascallar E, Dochy F (2013) A meta-analysis of the effects of face-to-face cooperative learning. Do recent studies falsify or verify earlier findings? Educ Res Rev 10:133–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2013.02.002

Leng J, Lu XX (2020) Is critical thinking really teachable?—A meta-analysis based on 79 experimental or quasi experimental studies. Open Educ Res 26(06):110–118. https://doi.org/10.13966/j.cnki.kfjyyj.2020.06.011

Lipsey M, Wilson D (2001) Practical meta-analysis. International Educational and Professional, London, p 92–160

Lin GY (2020) Scripts and mastery goal orientation in face-to-face versus computer-mediated collaborative learning: Influence on performance, affective and motivational outcomes, and social ability. Comput Educ 143:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.03.002

Li HF, Wang W (2022) The 30 years of CSCL research: research orientation, core issues, and future challenges-key analysis based on the International Handbook of Computer Supported Collaborative Learning. Res Modern Dist Educ 34(05):101–112

Liu QT, Yang SH, Zheng XX, Chen L (2024) Research on the impact of cognitive group perception tools on the level of knowledge construction in online collaborative learning Res Electron Educ 45(10):49–57. https://doi.org/10.13811/j.cnki.eer.2022.10.007

Luo YC, Zheng YL (2024) An empirical study on the promotion of critical thinking development through blended collaborative learning Open Educ Res 30(02):109–119. https://doi.org/10.13966/j.cnki.kfjyyj.2024.02-012

Ma ZQ, Li HW, Wang WQ, Li YM (2021) Why interdisciplinary collaborative learning is effective - a meta analysis of the effect of CSCL application in STEM education. Res Modern Dist Educ 33(01):97–104

Morris SB (2008) Estimating effect size from the pretest-posttest-control design. Organ Res Methods 364–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428106291059

Nokes, Malach TJ, Richey JE, Gadgil S (2015) When is it better to learn together? Insights from research on collaborative learning. Educ Psychol Rev 27(4):645–656. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9312-8

Persky AM, Pollack GM (2010) Transforming a large-class lecture course to a smaller-group interactive course. Am J Pharm Educ 74(9):1–6. https://doi.org/10.5688/aj7409170

Resta Laferrière T (2007) Technology in support of collaborative learning. Educ Psychol Rev 19:65–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-007-9042-7

Schellens T, Valcke M (2006) Fostering knowledge construction in university students through asynchronous discussion groups. Comput Educ 46:347–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2006.03.004

Stahl G, Koschmann T, Suthers D (2006) Computer-supported collaborative learning: an historical perspective. Sawyer RK (ed) Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences. Cambridge University Press, p 479–500

Stewart L, Tierney J, Burdett S (2006) Do systematic reviews based on individual patient data offer a means of circumventing biases associated with trial publications? Publication bias in meta-analysis. John Wiley and Sons Inc, New York, p 261–286

Strijbos JW, Martens RL, Jochems WM (2004) Designing for interaction: Six steps to designing computer-supported group-based learning. Comput Educ 42:403–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2003.10.004

Sung YT, Yang JM, Lee HY (2017) The effects of mobile-computer-supported collaborative learning: meta-analysis and critical synthesis. Rev Educ Res 87(4):768–805. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654317704307

Sung HY, Hwang GJ (2013) A collaborative game-based learning approach to improving students’ learning performance in science courses. Comput Educ 63:43–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.11.019

Tsuei M (2011) Development of a peer-assisted learning strategy in computer-supported collaborative learning environments for ele-mentary school students. Br J Educ Technol 42(2):214–232. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2009.01006.x

Uzunboylu H, Cavus N, Ercag E (2009) Using mobile learning to increase environmental awareness. Comput Educ 52:381–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2008.09.008

Watson SW, Dubrovskiy AV, Peters ML (2020) Increasing chemistry students’ knowledge, confidence, and conceptual understanding of pH using a collaborative computer pH simulation. Chem Educ Res Pract, 21. https://doi.org/10.1039/c9rp00235a

Wang XZ, Tu YX, Zhang LJ, Huang QH (2022) Research on the efficiency enhancement mechanism of online collaborative learning from the perspective of cognitive burden. Res Electr Educ 43(09):45–52+72. https://doi.org/10.13811/j.cnki.eer.2022.09.006

Wu JH, Fu HL, Zhang YH (2023) Meta analysis of the relationship between perceived social support and student academic achievement: the mediating role of learning engagement. Progr Psychol Sci 31(04):552–569

Xu E, Wang W, Wang Q (2023) The effectiveness of collaborative problem solving in promoting students’ critical thinking: a meta-analysis based on empirical literature. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10:16. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-01508-1

Xu EW (2023) Research on the design and application of collaborative learning activities to promote deep learning (Thesis, Xinjiang Normal University) PhD. https://doi.org/10.27432/dcnki.gxsfu.2023.000010

Zhou Q, Deng Y (2023) The impact of technology-supported teaching interventions on the cultivation of students’ computational thinking: a meta-analysis based on 37 international empirical studies J Southwest Univ 45(06):44–56. https://doi.org/10.13718/j.cnki.xdzk.2023.06.005

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the 2025 Ministry of Education Humanities and Social Sciences Research Project named “Research on the Generation Mechanism and Advanced Path of Digital Literacy of Rural Teachers in Northwest Border Areas from the Perspective of Human Machine Collaboration”, and the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region Tianchi Talent Introduction Program and the Doctoral Research Foundation of Xinjiang Normal University named “Research on Innovative Models of Collaborative Deep Learning Empowered by Education Digitalization for Normal University Students” (No.: XJBSRW2024023), and the Research and Reform Project on Undergraduate Education and Teaching in Autonomous Region Universities in 2025 named “Teaching Practice Path Research on Human Computer Collaboration Empowering the Advanced Improvement of Numerical Intelligence Literacy of Undergraduate Students in Xinjiang Universities” (No.: XJGXXJGPTA-2025022), and the key project of the 2025 Xinjiang Normal University Think Tank Bidding Project named "Research on the Evaluation and Optimization Path of Digital Empowerment for High Quality Development of Rural Education in Xinjiang” (No.: ZK2025B11), and 2025 Planning Project of the Taofen Foundation named “Innovative Research on Content Creation and Publishing Using AI Technology” (TF2025023).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Enwei Xu, Li Zhou and Xuezhen Feng conducted the literature search and were involved in the analysis and interpretation of data as well as writing-review and editing; Kewe Ning and Yuan Wang conducted the literature search and were involved in the analysis and interpretation of data; Enwei Xu, Li Zhou and Huanhua Li drafted and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, E., Feng, X., Ning, K. et al. The effectiveness of technical-supported collaboration in promoting students’ learning outcomes: a meta-analysis based on empirical literature. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1505 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05766-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05766-z