Abstract

Using the land finance system to alleviate fiscal constraints on government spending in regional development was a promising strategy that was widely adopted. Unfortunately, the drawbacks of this system for facilitating high-quality regional economic integration (REI) became increasingly apparent, attracting significant attention from the international academic community. Even so, promoting the transformation of land finance and optimizing the financial structure of local governments remained underexplored. This study used data from 108 cities located within China’s Yangtze River Economic Belt from 2002 to 2020, employing baseline, spatial econometric, and machine learning models to investigate the role of land finance in urban-level REI. The results indicated that REI and land finance exhibited significant and similar evolutionary patterns across both spatial and temporal dimensions. Over time, the impact of land finance on REI shifted, showing a negative effect during the boom stage and a positive effect during the subsequent transitional stage. Additionally, the spatial diffusion effect of land finance on REI initially showed a positive trend, which later turned negative. Specifically, the positive spatial effect of the land transfer mode progressively intensified, while the negative spatial effect of the land investment mode gradually diminished. Furthermore, land finance exhibited nonlinear influences on urban sprawl within specific thresholds. The findings of this research provided significant policy implications for effectively supporting urban economic integration through precise governance of land finance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Amidst the backdrop of industrialization and globalization, the concept of regional economic integration (REI) has surfaced as a dominant strategy for cultivating high-caliber economic advancement (Onduko, 2013; Obasaju et al. 2021). This phenomenon transpires not solely on a global scale, but also within individual nations, encompassing diverse geographic areas (Van Oort et al. 2010). The former pertains to the integration of multiple economies, as demonstrated by entities such as the European Union and the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (Onduko, 2013). Conversely, the latter encompasses intra-REI spanning provinces and urban centers. Prevailing attributes of these regional integrations encompass geographical proximity and comparable levels of economic progression (Hjaltadóttir et al. 2020; Wang, 2015). Nevertheless, in practice, the trajectory of REI is not invariably smooth. Chinese policymakers have increasingly voiced apprehensions regarding cross-regional domestic integration, aimed at catalyzing collaborative regional advancement, particularly subsequent to embarking on a new developmental phase (Chen and Hu, 2008). During the era characterized by high-quality development, escalated risks have arisen concerning national competition. Consequently, China has devised and disseminated pivotal strategies for spatial development and liberal market policies to invigorate the growth of economic zones and urban agglomerations. Concurrently, the Chinese government has proffered the proposition of instituting an efficacious mechanism for regional coordination. Endowed with governmental political, economic, and financial backing, the circulation of labor and capital among Chinese provinces and cities has been facilitated. Consequently, levels of REI have escalated due to the removal of regional obstacles.

Land finance serves as a crucial instrument for reconciling the conflict between accelerated economic growth and harmonized regional development. It has the capacity to amass substantial capital to foster economic advancement and alleviate the government’s financial disparities, thus establishing a robust foundation for economic growth (Gandhi and Phatak, 2016; Gyourko et al. 2022; Miao et al. 2024). Nevertheless, as the scale of land finance expands, its detrimental impacts may surpass the benefits it offers as a financial supplement. According to incomplete statistics, the total land transfer fees amounted to CNY 5.956 trillion in 2000, and subsequently surged to CNY 59.827 trillion in 2020. While the notion of diminishing the financial attributes of land and real estate had progressively gained consensus, the substantial reliance on land finance had led to a range of persistent issues. These encompassed the depletion of extensive agricultural land, the formation of real estate bubbles, and unsustainable land utilization (Zheng et al. 2025; Miao et al., 2024). Particularly, local administrations frequently employ extensive land as collateral for debt repayment, thereby diminishing their capacity to service debt (Haila, 2007; Wu, 2022), and engendering enduring harm to REI over time. With the rise in frequency of regional exchanges and connections, the imperative of instructing urban planners and policymakers on crafting a land finance system that facilitates efficient and sustainable coordinated development of the regional economy and society has grown more pronounced than ever.

Previous research prominently concentrated on the correlation between land finance and regional economic development, tracing its origins back to two seminal theories: Marx’s theory of land rent and Perutz’s theory of growing polar (Perroux, 1950; Marx, 1959). Subsequently, a growing body of studies has delved into the correlation between land finance and regional development (Peterson, 2008; Wu et al. 2015). Chen et al. (2024) acknowledged that land finance played a pivotal role in influencing urban agglomeration integration. It tackled fiscal gaps confronted by local governments through augmenting transportation infrastructure supply capacity and fostering traditional manufacturing industries. This dynamic triggered urban sprawl and reduced traffic expenditure, culminating in the enlargement of urban clusters (Wei and Ewing, 2018). The cyclical nature inherent to land finance, with its economies and diseconomies of agglomeration activities within cities, impacted economic productivity and efficiency. Thus, urban economic theories suggested that the relationship between land finance and economic productivity/efficiency could exhibit nonlinearity. Controversial findings have been reported by Du and Peiser (2014) that centralized residential land supply diminishes urban economic connectivity, whereas commercial land transfer plays a constructive role. Furthermore, driven by the pursuit of economic growth and fiscal revenue, local authorities were motivated to foster a race-to-the-top rivalry in land finance, aiming to alleviate government debt burdens (Huang and Zhang, 2016). City-level competition could erode the trust between local administrations, thereby yielding negative repercussions for REI. Therefore, the competition effect and agglomeration effect stemming from land finance not only fostered REI within the immediate locale but also yielded a broader radiation effect on neighboring provinces or regions. However, REI constituted an intricate process that interwove diverse cities into a network, transcending the mere establishment of simple economic efficiency links between them. The direct exploration of the impacts exerted by cities’ land finance attributes has remained a relatively unexplored area in theoretical research.

Prevailing research methodologies, such as descriptive statistics analysis (Wu, 2022), ordinary least squares (OLS) (Zhang et al. 2025), and spatial econometric model (Chen et al. 2024), predominantly employed linear regression models to scrutinize the direct influence of land finance on factors related to regional economic development. These approaches exclusively estimated the effect of land finance on REI from a temporal perspective and disregarded the spatial and urban development periodization feature of this effect, leading to biased or invalid estimation outcomes. Additionally, within China, two prevalent land finance modes existed: the ‘land transfer-oriented mode’ (LTM) and the ‘land investment-oriented mode’ (LIM). These modes were tailored for diverse industry categories and produced distinct economic structures. Therefore, comprehending the influence of heterogeneity in land finance modes on changes in REI was imperative for the rational allocation of land resources. Regrettably, present research has failed to account for the distinct contributions of these two mode variables when assessing the impact of land finance on REI. Previous studies validated that diverse land finance scales might exert varying impacts on urban development (Guo and Shi, 2018), yet little attention has been paid to the scaling effects of land finance on REI.

Considering the limitations of previous research, how land finance influences REI across temporal variations, spatial spillovers and scaling disparities, while incorporating the inter-city’s associated features of REI. The paper presents the following creative points as well. From both theoretical and empirical perspectives, this study constructed a comprehensive theoretical framework to elucidate the impact of land finance on REI–a facet that earlier scholarly works have given limited consideration to. Earlier literature explored the drivers of land finance (Davig and Leeper, 2011; Ye and Wang, 2013) and its socioeconomic ramifications (Peterson, 2008; Wu, 2022), encompassing aspects like alterations in industrial structure (Wang et al. 2021), economic expansion (Chen et al. 2024), housing prices (Glaeser et al. 2017), and urbanization path (Liu et al. 2022). However, limited research existed concerning the direct correlation between land finance and REI. Also, the majority of studies disregarded the heterogeneity inherent to diverse land finance modes. Moreover, the combination utilization of OLS, spatial, and RF approaches avoided the neglect of multiple correlations between land financing and REI in previous studies, ensuring the acquisition of precise outcomes. From a managerial standpoint, this study generated novel insights into the establishment of a land trading mechanism that augments the efficiency of REI. Additionally, despite land finance being closely associated with Chinese economic and policy frameworks, the insights garnered from this study hold relevance for other nations that harness land value to bolster fiscal revenue. Consequently, the policy recommendations offered possess significant cross-national applicability.

Land finance in China

Fundamentally, the term “land finance” in China pertained to addressing the financial requirements of local governments through revenue generated from land sales and land taxes (Wang et al. 2021). This concept originated from the incongruity between the fiscal authority and administrative power of central and local governments following the reform of the tax-sharing system in 1994 (Zhang et al. 2025). To mitigate the fiscal disparity stemming from this incongruity, local administrations endeavored to augment “extra-budget revenue”, consequently rendering “earning revenue from land” a potent strategy for achieving economic growth and political enhancement. In contrast to tax receipts, local governments possessed greater autonomy in managing land-generated revenue. Consequently, within the context of Chinese scholarly discourse, the prevailing notion posited that land conveyance fees serve as a gauge of land finance (Wu et al. 2015). Similarly, the majority of English-language studies addressing land finance and its relation to Chinese urban development aligned with this viewpoint (Gandhi and Phatak, 2016). In practical terms, the evolution of China’s land finance could be categorized into three stages (Fig. 1): the initial stage (1998–2003), the boom stage (2004–2013), and the transitional stage (after 2014).

In particular, LTM and LIM are two distinctive land finance modes that have prevailed within China. In the former, the government assumed the role of profit-seeker and revenue generator, aiming to maximize revenue from land conveyance to bolster fiscal inflow, alleviate financial constraints, and concurrently manage urban development. The area of land transfer through bidding, auction, and listing is the determinant of land marketization revenue, which could represent the LTM mode in this study (Yan et al. 2013). In the LIM mode, the government functioned as a political entity driven by the desire to enhance political achievements. Frequently, achieving a lower price for industrial land—often through agreement-based land transfer—served as an immediate strategy to attract investments and expedite the advancement of leadership positions.

Literature overview and theorized mechanisms

Literature overview

The topic of land finance garnered significant attention within global academic circles, as prior literature delved into its determinants and effects on regions and cities (Peneder, 2003; Ye and Wang, 2013; Rithmire, 2017). Regarding the repercussions of land finance, critics contend that excessive reliance on this approach could result in farmland appropriation, intergenerational and regional disparities, potential real estate bubbles, corruption, fragmented urban planning, and societal instability (Ma et al. 2024; Huang and Chan, 2018). Conversely, other scholars posited that land finance offers an innovative avenue for promptly generating income, amassing requisite infrastructure investment, and fostering rapid capital accumulation with a high reinvestment rate (Lu et al. 2020). Ex-ante studies summarized the impact of land financial incentives on local government behavior, including land expropriation, infrastructure construction, and attracting investment (Fan and Zhang, 2020; Medda, 2012). Land finance exerted substantial spatial spillover effects on the behavior of regional economic development (Fan and Zhang, 2020). Governments endeavored to attain optimal economic and political competitive advantages, consequently reaping rewards within the context of the promotion tournament. In addition, capital entering land economic production showed substantial benefits for regional integration (Hjaltadóttir et al. 2020). Therefore, the Chinese government had prompted a series of strategies to promote regional integration. Central to the factors influencing regional integration are industrial relocation (Wang and Shao, 2025), economic advancement (Chen et al., 2023), and pertinent plans (Guo et al. 2025). Concerning land finance affecting REI, most studies were carried out indirectly, with numerous researchers incorporating additional dependent variables associated with REI in their empirical analyses. These variables encompassed urban sprawl (Liu et al. 2016), industrial structure (Wang et al. 2021), economic correlation intensity (Hu and Qian, 2017), and infrastructure connectivity (Garmendia et al. 2012).

Scholars have extensively investigated the influence of financial development on regional economic integration. Authorities often promote regional integration by enhancing infrastructure development, which requires substantial capital investment (Nawaz and Mangla, 2021). As a result, local revenue remains stable, while expenditures experience a significant increase in regional synergy. Fujita and Krugman (2004) examined the dynamic evolutionary changes in regional integration within Russia and investigated its potential determinants. They identified a strong negative correlation between internal economic integration and the degree of financial openness to international trade. Chen et al. (2023) discovered that the regional financial situation within urban agglomerations significantly affected China’s regional integration.

Concerning land finance affecting regional economic integration, the majority of studies have been carried out indirectly, with numerous researchers incorporating additional dependent variables associated with regional economic integration in their empirical analyses. These variables encompassed urban sprawl (Liu et al. 2016), industrial structure (Wang et al. 2021), economic correlation intensity, and infrastructure connectivity (Garmendia et al. 2012). Combes (2011) discovered that local governments tended to overallocate land resources to urban infrastructure construction, while providing an insufficient supply for human capital and public services. This imbalance contributed to the swift expansion of urban land. Simultaneously, land finance significantly boosts the supply capacity of transportation infrastructure through compensatory mechanisms, thereby facilitating the reduction of financial gaps. These pathways were anticipated to serve as conduits for fostering urban agglomerations. Land finance was likely to shorten the commuting time between two cities of urban agglomerations by improving urban transportation infrastructure, which has been substantiated by empirical studies (Chen et al. 2024; Zhang et al. 2025). Nevertheless, the connections between land finance and the development of urban agglomerations continued to be enigmatic. Some scholars have identified diverse patterns, encompassing U-type, inverted U-type, and inverted N-type configurations (Chen et al. 2023).

While the economic implications of land finance have gained substantial recognition among international scholars, a notable deficiency persisted in conducting exhaustive and precise research concerning its effects on regional economic integration that considered temporal, spatial, and scaling aspects. To understand the government’s measures and clarify the underlying logic of regional development, additional insights are needed into the relationship between these two variables.

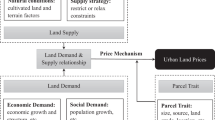

A theoretical framework of multiple roles of land finance on REI

As highlighted in the aforementioned insights, REI was driven by land finance through mechanisms of capital accumulation, efficiency circuits, and governance. Consequently, we propose a theoretical framework that examines the multiple roles of land finance on REI from temporal, spatial, and scaling perspectives (Fig. 2). Subsequent sections will provide a detailed elaboration of these effects.

Temporal effect

Land finance functioned as a pivotal source of extrabudgetary revenue, with its statistical attributes directly linked to the production efficiency of urban construction within cities (Graham, 2007; Chen et al. 2024). Empirical evidence indicated that during the initial stages of land finance, pressure incentives outweighed investment competition. During this period, the impact of land finance on REI was positive, manifesting in two primary ways. Firstly, through traditional territorial management, land finance emerged as a crucial method for bridging the growing fiscal gap resulting from REI efforts (Mittal, 2014). Secondly, significant changes in land finance altered production spaces and substantially increased land values in neighboring areas (El-Nagdy et al. 2018; Zhou and Lin, 2025). This led industries to concentrate in specific areas to reduce cross-regional communication costs. The concentration of production facilitated both horizontal and vertical labor division, resulting in economies of scale within economic agglomerations.

However, this process also introduced a paradox: while agglomeration economies initially offered benefits, they eventually led to agglomeration diseconomies due to spatial production competition. For example, the marginal benefits of infrastructure incentives on REI may have started to decline during the land finance boom, leading to disorderly urban expansion, industrial homogenization, and production competition (Ma et al. 2024; Glaeser et al. 2017). In 2014, China introduced the New-Type Urbanization Plan, which emphasized people-centered development and aimed to reduce local governments’ excessive reliance on land finance (Guo and Shi, 2018). Measures included constraining land supply quotas, curbing housing speculation, and limiting land use for collateral loans (Zhang, 2017; Zhang et al. 2025). This reduction in land finance increased the burden on local governments and decreased net revenue during the transitional phase (Tang et al. 2019; Gyourko et al. 2022), thereby altering the impact of land finance on REI. In summary, the effects of land finance on REI likely varied across different stages.

Spatial effect

The supply of urban land across different cities was interconnected, and the competitive strategies of local governments often led to spatial imitation or substitution effects in land finance approaches (Perez-Moreno, 2024). This interconnectedness highlighted how changes in land finance scales in neighboring cities could impact REI levels in a given city. Firstly, government authorities, driven by political motivations to enhance their standing (Wang and Hou, 2021; Guo et al. 2025), increased their intervention in high-value land transfers to secure financial and political advancement. This created a race-to-the-top competition, with traditional industries and urban infrastructure development becoming focal points for rapid wealth accumulation, particularly under intergovernmental competition (Chen et al. 2020; Zhang et al. 2025). Such competition significantly influenced REI. Local governments, aiming to boost fiscal revenue and address budget shortfalls, competed to raise land transfer prices (Brandt et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2025). Industries unable to afford high land costs relocated to neighboring cities with lower prices due to this competitive environment. The departure of low-value-added industries from original cities paved the way for the dominance of technology-intensive and strategically emerging industries, thereby accelerating industrial spatial transfer, technical information exchange, and overall industrial integration.

Secondly, motivated by economic ranking incentives, local governments adjusted land supply structures in response to investment competition (Peterson, 2008; Zheng et al. 2025). As competition intensified, local governments were more inclined to offer land at reduced prices to attract investment. This often led to aggressive competition over industrial land transfer prices and a spatial imitation effect in land investment strategies among cities (Mittal, 2014; Huang and Zhang, 2016). Conversely, a spatial substitution effect emerged due to the interaction between land and capital, impacting the relative economic advantages of cities and influencing REI. In conclusion, we posited that land finance could have a spatial impact on REI.

Scaling effect

Due to variations in political status, geographical location, resource endowment, and economic development, Chinese cities exhibited diverse scales, ranks, and magnitudes of land finance (Chen et al. 2023). High-ranking cities, endowed with abundant revenue streams and economic prowess, demonstrated a preference for efficient and intensive land utilization within their limited land resource quotas (Han and Lu, 2017). This approach allowed these cities to focus on advanced industrial development to achieve substantial economic gains, reducing their reliance on land finance while still supporting the advancement of REI.

In contrast, lower-ranked cities with less developed economic statuses faced limitations in financial revenue sources. These cities often struggled with local debt management and fund allocation efficiency, despite having relatively ample land supply. Consequently, they tended to employ inefficient and extensive land conversion strategies in their efforts to stimulate REI (Huang and Zhang, 2016; Mo, 2018). The complex debt structures and interconnected debt chains associated with land finance in these cities could potentially serve as conduits for the spread of regional financial risks, thereby impeding the development of regional economic linkages and integration processes. In summary, our proposition suggested that the impact of land finance on REI varies significantly across cities of different levels and scales.

Methods and data

Study areas

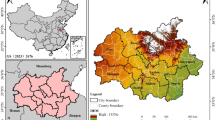

The evolving dynamics of diversified production, accelerated urbanization, and spatial restructuring driven by globalization have progressively emerged as new stimuli for economic growth (Obasaju et al. 2021). In response to this transformative trend, numerous countries have initiated a range of regional development strategies. For instance, the Regional Plan Association has meticulously devised the American 2050 Plan, outlining strategies for 11 megaregions. Similarly, the Chinese central government has unveiled multiple nationwide urban agglomeration development plans. The Yangtze River Economic Belt (YREB) strategy has long been introduced to foster synchronized regional development. Serving as a pivotal implementation domain for national strategies, the YREB encompasses nine provinces and two municipalities, spanning the upstream (Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, and Yunnan), midstream (Jiangxi, Hubei, and Hunan), and downstream (Shanghai, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Anhui) regions (Fig. 3), it collectively accommodates over 40% of the nation’s population, GDP, and water resources within ~21.4% of China’s land territory. Throughout its history, the YREB has placed significant emphasis on national REI strategies, resulting in notable accomplishments. However, the rapid economic growth and large-scale city construction incurred high costs, which in turn encouraged the rapid growth of land financing and caused real estate bubbles, farmland encroachment, and eco-environmental destruction. As China embarks on a new economic phase with limited land resources, the YREB faces the challenge of balancing the potential impacts of land finance on REI while addressing the tension between developmental goals and environmental protection. This paper aims to furnish policymakers with updated insights to avoid misguided policies that could undermine both land development and economic growth.

Methodology

The methodological framework of this paper, comprising four steps, is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Measuring land finance

As demonstrated in prior studies by Wu (2022) and Wang et al. (2021), land conveyance fees served as a proxy indicator for assessing the extent of land finance. Two key explanatory variables were selected to capture distinct modes of land finance. The LTM was represented by the area of land transferred through bidding, auction, and listing, following the methodology of Wu (2022). Conversely, the LIM was denoted by the area of land transfer based on agreements, as adopted by Yan et al. (2013), to address potential heteroscedasticity interference; the natural logarithm of land finance was introduced as an independent variable in the subsequent measurement model.

Measuring city-level REI

The essence of REI is to measure the intensity of interactions between economic activities across regions, which includes the exchange of industrial and agricultural products, technology and information, labor, and human resources (Wei and Ewing, 2018). This measurement is closely linked to the levels of economic development, population size, and the geographical distance between regions (Zhao et al. 2025). In this situation, the gravity mode:

serves as a widely employed tool for quantification (Zhao et al. 2025; Chen et al. 2025). In this model, Pi and Pj are the amount of population of city i and j, respectively. Vi and Vj are the amounts of GDP of city i and j respectively. Dij is the distance between city i and j. However, the spatial distance cannot truly reflect the linkage intensity between cities. In contrast, the urban flow intensity F (Gadepalli et al. 2024) is an important guideline that reflects the concentration and diffusion capacity of a city. Therefore, a modified gravity model is developed to measure the economic linkage between two cities:

In formula (2), \({F}_{i}={N}_{i}\times {E}_{i}=\sum {E}_{ij}\times {\rm {GD{P}}}_{i}/{G}_{i}\); exogenous function E depends on location entropy \({L}_{ij}={G}_{ij}-{G}_{i}\times ({G}_{j}/{G}_{i})\); when Lij < 1, E = 0. When Lij > 1, \({E}_{ij}={G}_{ij}-{G}_{i}\times ({G}_{ij}/G)\), and Gi indicates the employee number of city i, Gij indicates the total employee number of sector j in city i, Gj, indicates the employee number of sector j, and G indicates the sum of all employees.

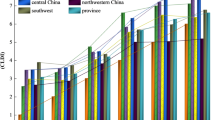

The descriptive statistics of the data included in this enriched REI measurement model is delineated as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Control variables

Numerous factors may have contributed to changes in REI. Key among these are economic development, government support, transportation conditions, and international communication, which significantly impact industrial development and REI. Therefore, following existing research (Ye and Wang, 2013; Herrmann-Pillath et al. 2014; Chen et al. 2024), surrogate indicators were selected to represent urbanization levels, industrial composition, governmental regulations, openness, transportation capacity, and technological innovation as control variables.

“Baseline-Spatial-RF” models

The study utilized a comprehensive methodology, employing OLS, spatial econometric regressions, and a Random Forest (RF) model to examine the various impacts of land finance on REI. The detailed construction of the models is illustrated in Fig. 8. Before proceeding with the analyses, Stata 14 and Python’s Sklearn software were utilized. To ensure the validity of the models, Pearson correlation coefficients (Corr.) and variance inflation factors (VIF) were calculated to evaluate multicollinearity. The results, shown in Fig. 6, revealed no statistically significant correlations or multicollinearity among the variables.

Datasets source

We focused on the period from 2003 to 2020, reflecting the three stages of land finance. During these years, we gathered relevant data, encompassing both geospatial and socioeconomic information: (1) Geospatial data: Administrative boundaries, city centers, and water bodies were obtained from the National Catalogue Service for Geographic Information. (2) Socioeconomic statistics: Data on control variables (such as urbanization, industrial composition, government regulation, transportation, openness, and technological innovation) and REI were sourced from the China Urban Construction Statistical Yearbooks (2003–2020), the China City Statistical Yearbooks (2002–2021), and various provincial or city statistical yearbooks. Land finance data was acquired from the China Land Market Website. Cities with significant missing data were excluded from the analysis, and some missing values were imputed using interpolation methods. Table 1 provides the statistical information for each variable.

Results

Descriptive results

Figure 7 illustrates notable variations in REI and land finance across both spatial and temporal dimensions. In terms of temporal dynamics, the average REI experienced an increase from 0.424 in 2003 to 2.925 in 2014 and further to 6.162 in 2020. During these two periods, the average annual growth rates stood at 34.67% and 6.51%, respectively. A parallel trend was observed for average land finance, which escalated from 8.979 in 2003 to 154.935 in 2012 and eventually to 399.983 in 2020. The calculated average annual growth rates for these stages indicated an initial intensification followed by a subsequent alleviation of the land finance trend.

In 2020, using the average land finance, the five scales of cities can be ranked from largest to smallest: supercities (2349.620), megacities (1895.14), large cities (669.016), medium cities (224.053), and small cities (131.415). Similarly, using the average land finance, the five scales of cities can be ranked from largest to smallest: supercities (44.839), megacities (31.857), large cities (10.213), medium cities (3.455), and small cities (1.446). Overall, REI and land finance exhibited congruent phased patterns between 2003 and 2020, which is similar to Gyourko et al. (2022) research. Moreover, the study’s samples were categorized into four regions: the Yangtze River Delta (YRD), the middle reach of the Yangtze River (MYR), Chengdu-Chongqing (CC), and non-urban agglomeration cities (NUA). The study presented the geographical evolution of REI and land finance during the year 2020. At the same year, the megacities, megalopolises, and large cities within YRD significantly reduced their dependency on land finance, concurrently displaying higher REI levels compared to other smaller and medium-sized cities. MYR is presently undergoing a phase of intensive land resource development and utilization, which is notably serving as a pivotal driver in advancing REI. Meanwhile, smaller and medium-sized cities exhibit a relatively greater reliance on land-based fiscal revenue compared to their larger counterparts. The mean REI level for CC remained notably modest, at 2.956. In the case of excessive reliance on land finance, it was inevitable to encounter problems such as weak financial development and prominent social contradictions in this region. The mean values for land finance and REI within the NUA stood at 273.57 and 2.695, respectively. Regarding spatial shifts, the REI levels in four sub-regions exhibited significant spatial heterogeneity and diffusion. In 2003, areas of high REI were primarily concentrated within the Yangtze River Delta region. By 2012, the count of high-value cities in terms of land finance had increased, with their distribution expanding further into the central region of YREB. This spatial trend persisted in 2020, with high-value REI cities displaying a sustained pattern of spatial dispersion. The spatial trajectory of land finance mirrored that of REI. Furthermore, the REI levels of small and medium-sized cities remained lower than those of large, mega, and super cities. A similar pattern was observed in land finance, varying in accordance with the urban scale over the study period.

OLS results

Table 2 presents the temporal evolution of the impact of land finance on REI. (1) Pre-2003: The coefficient for land finance had a positive value but was not statistically significant, indicating that land finance had a negligible impact on REI during this period. (2) 2004–2014: Land finance exhibited a negative effect on REI. Specifically, a 1% increase in land finance was associated with a 0.03% decrease in REI. This period, characterized by significant land finance expansion, has been shown to have had a notably detrimental impact. (3) 2015–2020: The effect of land finance on REI became positive. During this time, a 1% increase in land finance corresponded to a 0.287% increase in REI. This period marked a shift towards more beneficial outcomes from land finance.

This observation signified that the significance of land finance’s impact on REI was minimal during the initial stage, became significantly negative during the prosperous stage, and turned significantly positive during the transformative stage. As expected, factors such as urbanization, the level of openness, transportation, and technological innovation contributed to the progression of the REI process. Moreover, the results revealed that the directionalities of the coefficients for the LTM and LIM variables generally aligned with the baseline findings. Specifically, the influence of LTM on REI shifted from positive to negative and then reverted to negative, with statistical significance detected only during 2015–2020. In contrast, the influence of LIM on REI remained insignificant throughout the studied periods.

SDM results

Table 3 indicates that Moran’s I values were statistically significant throughout the study period from 2003 to 2020, suggesting the presence of spatial correlation in the relationship between land finance and REI. To address this spatial correlation, spatial regression models, including the spatial error model (SEM), Spatial lag model (SLM), and spatial Durbin model (SDM), were employed. Among these, the individual and time fixed SDM was selected based on results from the LM test, Hausman test, Wald test, and LR test for further empirical analysis.

In Table 4, before 2003, the regression coefficients of LF were both small and statistically insignificant, while the coefficient of W_LF exhibited a significant negative value. This observation indicated that the land finance of local cities had a detrimental impact on the REI of neighboring cities, aligning with theoretical expectations. The coefficients of l W_LF during 2004–2014 and during 2015–2020 were negative and positive, respectively, and both cleared the 5% significance threshold. This distribution implied that the land finance in neighboring cities could initially constrain and subsequently support local REI. Notably, different modes of land finance exhibited varying spatial effects on REI. The positive spatial effect of the land transfer mode gradually intensified, while the negative spatial effect of the land investment model gradually diminished.

For an in-depth analysis of the spatial interaction effects on REI, this study conducted partial differential decomposition to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the direct, indirect, and total impacts of various influencing factors on REI in Table 5. Before 2003, the indirect effects of land finance (LF) and its two applications were negative and not statistically significant. From 2004 to 2014, both the LF and land investment mode (LIM) had significant negative effects, while the land transfer mode (LTM) had a significant positive effect. From 2015 to 2020, LF shifted to having a significant positive effect. The findings suggest that the total effects of land finance on REI were initially negative and later positive. During 2015–2020, a 1 unit increase in land finance led to an average increase of 1.133 in REI. Overall, these outcomes underscore the robustness of both the baseline and SDM regressions.

RF results

Relative importance of influencing variables

This study employed the Inc Node Purity method to rank the relative importance of explanatory variables concerning REI (Fig. 8). The key findings from this analysis were summarized below: (1) Throughout 2002–2020, the relative importance ranking of land finance in relation to REI stood at fifth, fourth, and second, respectively. This pattern underscored the significant influence of the land finance factor in explaining the variances in REI. (2) The relative importance of land finance to REI exhibited an initial rapid increase followed by a gradual rise, with land finance playing a more substantial role in contributing to REI in 2020 than in 2002 and 2014. (3) Within the realm of control variables, technology emerged as the foremost contributor to the variations in REI, followed by industrial structure and government management. In contrast, urbanization demonstrated comparatively weaker explanatory prowess concerning REI variations. Among these factors, the relative importance levels of industrial structure, technology, and transportation exhibited a progressive increase, while the contributions of openness and urbanization displayed an upward trend. (4) When compared to the LTM factor, the LIM factor exhibited a higher average contribution to the variations in REI across the period spanning 2002–2020.

Scaling effects of influencing factors

The influence of explanatory variables’ scale effects was illustrated through partial dependency plots (PDP), as depicted in Fig. 9. Noteworthy findings encompassed the following: (1) In 2003, the PDP curves illustrating the impact of land finance on REI initially exhibited a steep decline followed by stabilization. By 2020, land finance demonstrated a positive influence on REI. These outcomes underscore the dual effects arising from the complexity of land finance. (2) A significant nonlinear effect of land finance on REI was evident. Overall, the PDP curves depicting the relationship between land finance and REI demonstrated a sharp initial decline, followed by an increase and a subsequent stabilization. (3) The nonlinear effects of the land finance factor were characterized by effective ranges and thresholds. Prior to 2003, land finance exerted a relatively limited impact on REI when its value was below 2.5 billion yuan. The threshold for land finance during 2004–2014 differed from that in 2002–2003. Once the value of land finance surpassed 40 billion yuan, its capacity to drive REI growth became negligible. Furthermore, the thresholds for the positive effects of land finance in 2015–2020 were identified as 50 and 105 billion yuan. In sum, land finance displayed a pronounced scale effect on REI. (4) In comparison to the LIM factor, LTM exhibited a more pronounced influence on the variations in REI across the period spanning 2002–2020.

Discussion

Temporal and spatial disparity of land finance and REI

This study emphasized the noteworthy temporal and spatial disparities observed in land finance and REI. The following key insights emerged: (1) Temporal Disparity: Since 2003, land finance has gradually emerged as a paramount concern within China’s financial system. Over the past two decades, the trajectory of land finance has experienced a steep upward trajectory, as corroborated by extant literature (Gyourko et al. 2022). Empirical evidence underscores this trend, revealing that the ratio of land finance to local public budget revenues surged from 27% in 2002 to 81.4% in 2020 (Fig. 1). Similarly, the proportion of land finance to the national government’s budget revenues escalated from 16.6% to 90% during the period spanning 2002–2020 (Fig. 1). Concurrently, the REI process witnessed a marked acceleration, with urban agglomerations gradually emerging as predominant forms of regional development (Obasaju et al. 2021; Chen et al. 2020). The REI levels were the highest in the YRD, followed by the MYR, CC, and NUA. As articulated by Davig and Leeper (2011), local expenditures grappled with formidable challenges related to upgrading urban infrastructure and promoting regional growth. Land finance assumed a pivotal role in catalyzing REI by offsetting financial shortfalls and furnishing essential public financial support (Storm, 2015). Nevertheless, following the proposition of the new urbanization concept, the pace of REI growth gradually decelerated. This trend aligns with the observations of Chen et al. (2023), who noted a reduction in regional integration momentum post-2010. The potential rationale underlying this phenomenon lies in the performance shortcomings of wealth generation through land, which can lead to resource depletion, severe pollution, infrastructure saturation, and cutthroat competition (Wang et al. 2021). Simultaneously, a congestion effect took root, accompanied by the emergence of overloaded industrial spatial configurations, which in turn exerted adverse effects on regional integration (Graham, 2007; Xu et al. 2025). (2) Spatial Disparity: Both land finance and REI exhibit a distinct spatial diffusion pattern, originating from the eastern region and subsequently extending to the central and western regions (Garmendia et al. 2012; Wang, 2015; Liu et al. 2024). The advantageous geographical positioning and economic dynamism of the eastern region constitute a sturdy foundation for the accumulation of land finance (Ye et al. 2013; Gandhi and Phatak, 2016). Heightened levels of economic development equip local governments with greater financial resources to enhance infrastructure and generate elevated land demand. This dynamic leads to augmented land prices, amplifies local government land revenues, and consequently fosters a reciprocal mechanism between land finance and economic growth (Wu, 2022). Such a mechanism emerges as a pivotal explanation for the pronounced regional spatial agglomeration effect in China’s land finance scale, accompanied by a trend of diminishing spatial dispersion across the eastern, central, and western regions (Gyourko et al. 2022). Scholarly investigations underscore that cities frequently spur regional integration by bolstering infrastructure construction that necessitates substantial land capital investment (Feng et al. 2023; Nawaz and Mangla, 2021). Fang et al. (2024) contend that certain central and western cities, constrained by limited resources, have established a multitude of industrial parks and economic development zones, specifically designed to facilitate the uptake of cross-regional factors and attract industrial investments. Particularly noteworthy is the marked enhancement of REI levels in Megacities and supercities (e.g. Wuhan, Chengdu, and Changsha), achieved through proactive pursuit of land finance and the establishment of industrial zones (Lu et al. 2020; Li et al. 2023). In stark contrast, coastal megacities and large cities such as Shanghai and Suzhou have ameliorated urban sprawl and elevated REI levels through successful land finance mode transformation (Rithmire, 2017; Hjaltadóttir et al. 2020).

Multiple roles of land finance on REI

This study further clarified the multiple and phased effects of land finance on REI. (1) Initial Stage: In the OLS model, the coefficients of LF, LTM, and LIM on REI were both small and statistically insignificant. The RF model revealed that the relative importance of land finance in relation to REI was relatively minor. This suggests that before 2003, land finance did not play a pivotal role in influencing REI. In the context of China’s ongoing infrastructure upgrades and regional development endeavors (Chen et al. 2024), coupled with heightened local expenditure, land finance had the potential to positively drive regional synergy by bridging financial gaps and providing public financial support (Rithmire, 2017). The limited positive impact during this phase could be attributed to the slow growth of land finance, which was constrained prior to the land marketization reform in 2003. Additionally, in the SDM model, the coefficients of LF and LIM were significantly negative. Governments displayed a preference for the LIM mode, enlarging the area of agreement-based land transfers at reduced land prices (Tang et al. 2019; Yu and Zhou, 2024). This approach inadvertently led to a crowding-out effect on the high-value-added service industry, impeding the high-quality development of REI. (2) Boom Stage: In the OLS model, the regression coefficient of LF on REI was significantly negative, while the relative importance of land finance to REI grew. This shift was likely linked to the surge in land finance dependence amid governments’ economic and political enthusiasm. As the scale of land finance expanded, government debt accumulation began to displace private investment, fostering debt risk contagion through tax, interest rate, and inflation channels (Gandhi and Phatak, 2016), which did not bode well for REI. Furthermore, both LF and LIM modes exhibited negative spatial effects on REI in SDM models. Competitive strategies among local governments could lead to spatial imitation or substitution effects in land finance approaches (Perez-Moreno, 2024). Consequently, land finance practices that involved selling state-owned land at lower agreement prices to attract industries resembled a “race to the bottom” (Mittal, 2014; Zhang et al. 2025). In such a scenario, economic competition fragmented economic markets in surrounding cities, inhibiting regional cooperation. Furthermore, the inhibitory effect of land finance on REI was evident when LF exceeded 105 billion yuan in the RF regression. This observation implied that cities with substantial land price advantages were inclined towards land supply, resulting in land finance competition and diminishing regional economic collaboration. Similarly, Chen et al. (2024) highlighted that excessive reliance on land fiscal revenue could impede regional integration due to fiscal gaps and investment impulses.

Policy implications

Based on our research findings, we proposed the following policy recommendations:

Firstly, there is a need to continuously promote the transformation of land finance. Since the tax-sharing reform in 1994, prefecture-level and county-level governments have faced increased fiscal pressure (Fan and Zhang, 2020; Wu et al. 2015). This has fueled their desire to reap benefits from land value appreciation. However, our research results, especially during the boom stage, demonstrate that excessive dependence on land finance can diminish its positive impact on REI. Thus, local governments should exercise caution in relying excessively on land finance. They should judiciously manage fiscal gaps at the county level and optimize the allocation of land-related income. One practical step could involve avoiding haphazard expansion of agreement-based land transfer areas and enhancing the efficient utilization of land resources. Local governments could establish price thresholds for agreement-based land transfers in investment projects to prevent unwarranted reliance on preferential policies. Additionally, the central government should provide support in diversifying investment mechanisms and reducing the proportion of locally generated tax revenue that is handed over. To bolster the REI process effectively, local governments should explore alternative revenue sources to substitute for land revenue. For instance, Shanghai introduced a pilot property tax system. Alongside developing a property tax structure centered on real estate tax (including property tax, urban land use tax, and deed tax), the possibility of introducing new tax types beneficial to local governments–such as environmental protection tax, urban infrastructure support fees, and urban construction and maintenance tax–could also be explored.

Secondly, it is crucial to fully consider the spatial spillover effects of land finance on REI. On the one hand, when formulating regional development strategies, local governments should account for both local conditions and the economic cooperation among cities of different scale levels. This approach enables surrounding medium and small areas to share the benefits of intensive land use and industrial development, thereby reducing regional development costs. Furthermore, the utilization of land finance within each city can impact the neighboring areas, given that governments are attuned to the land finance strategies of nearby cities. Thus, there is a need to enhance policies that alleviate passive inter-regional and intra-regional competition, along with guiding land finance utilization plans. Equally important is the prudent identification of sustainable land development strategies tailored to the distinctive economic development characteristics of various urban agglomerations and cities.

Thirdly, it is important to give greater attention to the threshold effect of land finance on REI. The research findings reveal that LF values below 2.5 or above 105 billion RMB were not conducive to REI. Thus, understanding how to capture more land value while maintaining an appropriate land finance scale is of paramount importance. Although spatial expansion played a significant role in REI, particularly in some small cities, a more targeted sprawl policy and a well-structured approach could enhance the efficiency of land revenue collection and facilitate coordinated REI development. Additionally, the development of both urban and rural stock land becomes necessary to meet the demands for fiscal revenue growth and China’s rural revitalization strategy. These measures empower local governments to promote efficient land resource utilization, bolster and diversify land funding sources, and enhance the positive impact of land finance on REI by allocating a larger portion of land conveyance revenue to lower-ranking cities. Additionally, it is feasible to allocate greater land development rights to high-performing cities (such as large cities in the YRD and supercities in the CC) that demonstrate enhanced productivity and returns. Actively promoting the market-oriented allocation of operational land is also recommended. Essential strategies encompass deepening the reform of the land management system, enhancing the construction land market framework, and piloting trading systems for land quotas spanning across provinces.

Conclusion

Conclusion

It was widely acknowledged that while land finance enhances agglomeration-based economic growth and the intensity of economic relations, excessive reliance on land finance can potentially result in efficiency-reducing effects. Striking a balance between land finance and the high-quality development of the regional economy has remained a pressing concern in the realm of urban economics. After uncovering the temporal, spatial, and scaling mechanisms through which land finance impacts REI, this study employed OLS, SDM models, and RF regression to comprehensively investigate the multi-dimensional effects of land finance on REI. The findings revealed a different impact of land finance on REI over time. The role of land finance increased during the boom stage but decreased during the transition stage. Additionally, the utilization of the LTC mode and the LIC mode yielded distinct REI development patterns. The spatial diffusion effect of land finance on REI displayed an initial positive trend followed by a negative trend. Specifically, the positive spatial effect of land transfer mode progressively intensified, while the negative spatial effect of the land investment model gradually diminished. Results from the RF regression highlighted the existence of effective ranges and thresholds in the nonlinear effects of land finance, land transfer mode, and land investment mode factors.

Contributions and limitations

The potential contributions of this research can be highlighted as follows: (1) This study has developed a reasonable concept and enhanced methodologies for measuring REI within the gravity model framework. This approach not only provides robust theoretical support but also enables the estimation of city-level REI by incorporating urban flow intensity factors. Additionally, it introduces a novel technique that can be extended to measure other types of regional integration efficiency, thereby deepening our comprehension of regional network structures. (2) A multidimensional theoretical framework was constructed to analyze the impact of land finance on REI. While previous studies established causal relationships using panel data modeling (Chen et al. 2024), our work represents a pioneering effort to comprehensively explore the effects of land finance on REI. By elucidating the temporal, spatial, and scaling effects, this study offers a novel perspective on understanding the various impacts. (3) To address issues of spatial spillover and nonlinear, spatial econometric models and machine learning algorithms were adopted. Traditional linear regression models may introduce bias into results by overlooking spatial non-stationarity. By confirming the spatial correlation of REI, this study demonstrated that the SDM model outperforms the OLS model in terms of goodness-of-fit. Furthermore, the study visualized the effective range of land finance’s impact on REI through visual interpretations of relative importance and partial dependency among variables.

Equally noteworthy, this study also had several acknowledged limitations. (1) The measurement indicators used to assess land finance could benefit from diversification. Different types of land transaction data should be applied for further analyses due to the increasing scarcity of land resources. (2) Land finance and its spillover impact will significantly affect REI. Future research on the topic can offer a more precise way to evaluate the spatio-temporal influence of REI on land finance. For example, constructing different spatial weight matrices could allow for the in-depth examination of effects considering geographical proximity and socioeconomic connectivity. (3) While this study selected certain factors affecting REI as control variables, it is worth noting that other unobservable factors (such as land spatial planning, policy control, and land quotas) remained unaccounted for due to limitations in data availability.

Data availability

Data will be made available upon reasonable request by contacting the corresponding author.

References

Brandt L, Van Biesebroeck J, Wang L, Zhang Y (2017) WTO accession and performance of Chinese manufacturing firms. Am Econ Rev 107(9):2784–2820

Chen D, Hu W, Li Y, Zhang C, Lu X, Cheng H (2023) Exploring the temporal and spatial effects of city size on regional economic integration: evidence from the Yangtze River Economic Belt in China. Land Use Policy 132:106770

Chen D, Li Y, Hu W, Lang Y, Zhang Y, Cheng C (2024) Uncovering the influence of land finance dependency on inter-city regional integration: an explanatory framework integrating time-nonlinear and spatial factors. Land Use Policy 144:107207

Chen J, Hu C (2008) The agglomeration effect of industrial agglomeration: a case study of the Yangtze River delta. Manag World 68–83

Chen K, Long H, Qin C (2020) The impacts of capital deepening on urban housing prices: empirical evidence from 285 prefecture-level or above cities in China. Habitat Int 99:102173

Chen W, He Y, Wang Y, Liu Y (2025) A dynamic-radius-based fusion gravity model for influential nodes identification. Inf Sci 719:122469

Combes PP (2011) The empirics of economic geography: how to draw policy implications? Rev World Econ 147(3):567–592

Davig T, Leeper EM (2011) Monetary-fiscal policy interactions and fiscal stimulus. Eur Econ Rev 55(2):211–227

Du J, Peiser RB (2014) Land supply, pricing and local governments’ land hoarding in China. Reg Sci Urban Econ 48:180–189

El-Nagdy M, El-borombaly H, Khodeir L (2018) Threats and root causes of using publicly-owned lands as assets for urban infrastructure financing. Alex Eng J 57(4):3907–3919

Fan Z, Zhang J (2020) Fiscal decentralization, intergovernmental transfer and market integration. Econ Res J (3), 53–64 (in Chinese)

Fang G, Gao T, Xu P (2024) Beyond the borders: estimating the effect of China’s Bonded Zones on innovation and its spillovers. China Econ Rev 83:102104

Feng Y, Lee CC, Peng D (2023) Does regional integration improve economic resilience? Evidence from urban agglomerations in China. Sustain Cities Soc 88:104273

Fujita M, Krugman P (2004) The new economic geography: past, present and the future. Papers Reg Sci 83(1):139--164

Gandhi S, Phatak VK (2016) Land-based financing in metropolitan cities in India: the case of Hyderabad and Mumbai. Urbanisation 1(1):31–52

Garmendia M, Romero V, Ureña JMde, Coronado JM, Vickerman R (2012) High-speed rail opportunities around metropolitan regions: Madrid and London. J Infrastruct Syst 18(4):305–313

Gadepalli R, Bansal P, Tiwari G, Bolia N (2024) A tactical planning framework to integrate paratransit with formal public transport systems. Transp Res Part D: Transp Environ 136:104438

Glaeser E, Huang W, Ma Y, Shleifer A (2017) A real estate boom with Chinese characteristics. J Econ Perspect 31(1):93–116

Graham DJ (2007) Agglomeration, productivity and transport investment. J Transp Econ Policy 41(3):317–343

Guo S, Shi Y (2018) Infrastructure investment in China: a model of local government choice under land financing. J Asian Econ 56:24–35

Guo L, Tang M, Wu Y, Bao S, Wu Q (2025) Government-led regional integration and economic growth: evidence from a quasi-natural experiment of urban agglomeration development planning policies in China. Cities 156:105482

Gyourko J, Shen Y, Wu J, Zhang R (2022) Land finance in China: analysis and review. China Econ Rev 76:101868

Han L, Lu M (2017) Housing prices and investment: an assessment of China’s inland-favoring land supply policies. J Asia Pac Econ 22(1):106–121

Haila A (2007) The market as the new emperor. Int J Urban Reg Res 31(1):3–20

Herrmann-Pillath C, Libman A, Yu X (2014) Economic integration in China: politics and culture. J Comp Econ 42(2):470–492

Hjaltadóttir RE, Makkonen T, Mitze T (2020) Inter-regional innovation cooperation and structural heterogeneity: does being a rural, or border region, or both, make a difference? J Rural Stud 74:257–270

Hu F, Qian J (2017) Land-based finance, fiscal autonomy and land supply for affordable housing in urban China: a prefecture-level analysis. Land Use Policy 69:454–460

Huang D, Chan RCK (2018) On ‘Land Finance’ in urban China: theory and practice. Habitat Int 75:96–104

Huang S, Zhang C (2016) The influences of the agglomeration of producer services on the urban productivity: from the perspective of industry heterogeneity. Urban Dev Stud 23(3):118–124

Li J, Jiao L, Li R, Zhu J, Zhang P, Guo Y, Lu X (2023) How does market-oriented allocation of industrial land affect carbon emissions? Evidence from China. J Environ Manag 342:118288

Liu Y, Gao H, Cai J, Lu Y, Fan Z (2022) Urbanization path, housing price and land finance: international experience and China’s facts. Land Use Policy 113:105886

Liu J, Huang B, Hu Y (2024) The influence of tax incentives on market segmentation in the context of a unified national market. Financ Res Lett 65:105591

Liu Y, Yue W, Fan P, Peng Y, Zhang Z (2016) Financing China’s suburbanization: capital accumulation through suburban land development in Hangzhou. Int J Urban Reg Res 40(6):1112–1133

Lu X, Chen D, Kuang B, Zhang C, Cheng C (2020) Is high-tech zone a policy trap or a growth drive? Insights from the perspective of urban land use efficiency. Land Use Policy 95:104583

Ma S, Wang G, Xu C, Zhang X, Zhao Y, Cai Y (2024) Does the optimal land use pattern for cross-regional cooperation change at different stages of urbanization? Evidence from the trade-off between urban growth scenarios and SDGs indicators. Appl Geogr 167:103294

Marx K (1959) Economic and philosophic manuscripts of 1844. Economica 26(104):379

Miao Y, Li Y, Wu Y (2024) Digital economy and economic competitive pressure on local governments: evidence from China. Econ Model. 140:106859

Medda F (2012) Land value capture finance for transport accessibility: a review. J Transp Geogr 25:154–161

Mittal J (2014) Self-financing land and urban development via land readjustment and value capture. Habitat Int 44:314–323

Mo J (2018) Land financing and economic growth: evidence from Chinese counties. China Econ Rev 50:218–239

Nawaz S, Mangla IU (2021) The economic geography of infrastructure in Asia: the role of institutions and regional integration. Res Transp Econ 101061

Obasaju BO, Olayiwola WK, Okodua H, Adediran OS, Lawal AI (2021) Regional economic integration and economic upgrading in global value chains: selected cases in Africa. Heliyon 7(2):e06112

Onduko EB (2013) Regional integration and professional labour mobility: a case of East African Community (EAC). University of Nairobi

Peneder M (2003) Industrial structure and aggregate growth. Struct Change Econ Dyn 14:427–448

Perez-Moreno O (2024) Urban inequality and the social function of land value capture: the credibility thesis, financing tools and planning in Latin America. Land Use Policy 146:107285

Perroux F (1950) Economic space: theory and application. Q J Econ 64:89–104

Peterson GE (2008) Unlocking land values to finance urban infrastructure. Trends and policy options; no. 7. World Bank, Washington, DC

Rithmire ME (2017) Land institutions and Chinese political economy: institutional complementarities and macroeconomic management. Polit Soc 45(1):123–153

Storm S (2015) Debate: structural change. Dev Change 46(4):666–699

Tang P, Shi X, Gao J, Feng S, Qu F (2019) Demystifying the key for intoxicating land finance in China: an empirical study through the lens of government expenditure. Land Use Policy 85:302–309

Van Oort F, Burger M, Raspe O (2010) On the economic foundation of the urban network paradigm: spatial integration, functional integration and economic complementarities within the Dutch Randstad. Urban Stud 47(4):725–748

Wang D, Ren C, Zhou T (2021) Understanding the impact of land finance on industrial structure change in China: insights from a spatial econometric analysis. Land Use Policy 103:105323

Wang R (2015) A critical review of regional economic integration in China. Turkish Econ Rev. 2(2):88–103

Wang R, Hou J (2021) Land finance, land attracting investment and housing price fluctuations in China. Int Rev Econ Financ 72:690–699

Wang L, Shao J (2025) How does regional integration policy affect urban energy efficiency? A quasi-natural experiment based on policy of national urban agglomeration. Energy 319:135003

Wei Y, Ewing R (2018) Urban expansion, sprawl and inequality. Landsc Urban Plan 177:259–265

Wu F (2022) Land financialisation and the financing of urban development in China. Land Use Policy 112:104412

Wu G, Feng Q, Li P (2015) Does local governments’ budget deficit push up housing prices in China? China Econ Rev 35:183–196

Xu D, Shi P, Wu C, Diao Y (2025) Does regional integration promote the improvement of the green production efficiency of tourism industry? Econ Anal Policy 85:94–110

Yan Y, Liu T, Man Y (2013) Local government land competition and urban economic growth in China. Urban Dev Stud 73–79

Ye F, Wang W (2013) Determinants of land finance in China: a study based on provincial-level panel data. Aust J Public Adm 72:293–303

Yu B, Zhou X (2024) Land finance and urban Sprawl: evidence from prefecture-level cities in China. Habitat Int 148:103074

Zhang Y, Liu Y, Yang Q, Yue W (2025) Assessing performance and disparities in China’s land finance transition: insights from neo-liberalism and neo-Marxism. Land Use Policy 146:107306

Zhang Z (2017) The mutual effects between the fiscal relations of central and local governments and economic growth in post-reform China. Evol Inst Econ Rev 14(1):101–121

Zhao Y, Cheng S, Gao S, Lu F (2025) A gravity-inspired model integrating geospatial and socioeconomic distances for truck origin–destination flows prediction. Int J Appl Earth Obs Geoinf 136:104328

Zheng Z, Zhu Y, Zhang Y, Yin P (2025) The impact of China’s regional economic integration strategy on the circular economy: policy effects and spatial spillovers. J Environ Manag 373:123669

Zhou Y, Lin B (2025) Helping hand or grabbing hand: the impact of land finance on the green economic development in China. Financ Res Lett 71:106471

Acknowledgements

This research is funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42101307); the Natural Science Basic Research Pragram of Shaanxi Province (2024JC-YBQN-0265); the Humanity and Social Science Research Funds of Ministry of Education of China (21YJC790006 and 24YJA630052); the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC3210000); the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities 2662025GGPY004; and the Philosophy and Social Science Research Funds of Department of Education of Hubei Province (24Q116).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chaozheng Zhang, Danling Chen, and Chenning Deng contributed to writing the original draft, reviewing and editing the manuscript, and provided financial support. Xinhai Lu and Qingsong were responsible for conceptualization, review, and editing of the manuscript. Xupeng Zhang and Jiao Hou conducted data curation and prepared the tables. Jia Li and Yizhen Yin performed data analysis and prepared the figures. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This study utilized publicly available secondary data, including city-level socioeconomic statistics and official policy documents. All procedures performed in this research adhered to the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and complied with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. As the study did not involve direct interaction with human participants or the collection of identifiable private information, formal ethical approval was not required.

Informed consent

Since this study analyzed aggregated and anonymized secondary data from public sources, obtaining informed consent from individuals was not applicable. The data sources used ensure confidentiality and do not contain any personal identifying information.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, C., Chen, D., Zhang, X. et al. Underestimated impacts: the multi-dimensional roles of land finance in driving regional economic integration. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1729 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06026-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06026-w