Abstract

Despite growing attention to gender disparities in innovation, little is known about how gender shapes the characteristics and outcomes of patented inventions. This study analyzes 3.7 million U.S. utility patents, covering 1.8 million distinct inventors and over 200,000 organizations, to investigate the gendered patterns of inventorship. While women’s participation in patenting has increased over time, they remain significantly underrepresented, and patents involving female inventors consistently receive fewer citations than those by all-male teams. However, women-participated patents are more likely to exhibit novelty, originality, and technological generality, particularly when produced by mixed-gender teams, which tend to generate the most disruptive inventions. Female inventors also draw more heavily on scientific literature and public support, especially in green technology and academic settings. Organizational and domain-level differences are pronounced: universities involve women at higher rates than corporations, and fields such as biotechnology and civil engineering demonstrate distinct gendered patterns in patent quality and disruption. These results suggest that women make important yet often overlooked contributions to innovation and that structural barriers may suppress their full inventive potential. Addressing these disparities can enhance innovation diversity, expand the societal relevance of patented technologies, and better support the next generation of inventors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Inventions drive technological advances and economic development. Society benefits from an inventor population with a variety of backgrounds that can create diverse and valuable inventions. Despite this, there is a lack of diversity in inventors worldwide. In particular, women are significantly underrepresented. Female inventors and patents filed by women are substantially fewer than men. Compared to men, women are less likely to engage in inventive activities, file for patents, receive patent grants, appeal, or maintain granted patent rights (Huang et al., 2022; Jensen et al., 2018; Schuster et al., 2020).

While gender disparity in the quantity of patents is well-documented, whether such disparity extends to the characteristics of patents remains under-explored. Understanding gender differences in the characteristics of inventions can shed light on the underlying nature of gender gaps and indicate potential approaches to encouraging gender diversity in innovation. As the world’s largest economy (World Bank, 2025) and a major contributor to global technological innovation, the United States plays a central role in the global patent landscape. According to data from the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), the U.S. ranks among the top patent-filing countries globally (WIPO, 2024).Footnote 1 However, while the U.S. leads in the number and influence of patents in high-value sectors such as pharmaceuticals, software, and artificial intelligence, it also reflects many of the gendered patterns seen worldwide. Therefore, studying gender disparities in U.S. patenting not only offers insight into the national innovation system but also informs broader global conversations about equity and participation in knowledge economies.

This study compares women- and men-invented patents’ characteristics using several patent indicators, including impact, novelty, scope, reliance on public-supported research, and reliance on scientific knowledge. To conduct this analysis, we compiled a dataset comprising 3.7 million U.S. utility patents and 1.8 million distinct inventors with inferred gender information. This dataset is further enriched with three specialized sources that provide indicators of a patent’s disruption to existing technologies, its reliance on publicly funded research, and its references to scientific literature.

This study expands the current literature by examining gender disparities across a wide range of patent characteristics and institutional contexts. While we find that the number of female inventors has steadily increased over time, significant disparities persist. Women-invented patents tend to be cited less often, suggesting lower conventional impact. Yet, we also uncover evidence that female inventors contribute meaningfully to innovation through greater novelty, broader technological scope, and more disruptive inventions in certain domains. Despite societal and institutional barriers, women continue to advance the frontier of invention, often in distinct and underappreciated ways.

Literature review

Historical records show a large gender disparity in patenting. In the U.S., about 375,000 patents were granted to men in the 50 years from 1836 to 1888 (Schuster et al. 2020). By comparison, only about 3000 women inventors are identified during the first hundred years of the U.S. patent system (Pursell, 1981).

Since the 20th century, gender disparity in patenting has improved but still exists. Data from the WIPO shows that from 2000 to 2022, the percentage of female inventors worldwide who filed through the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) increased from 9.9% to 17.1%. Over the same period, the percentage of international patent applications that have at least one women inventor increased from 18.6% to 34.7% (WIPO, 2023). The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) also reported that the percentage of women inventors in the U.S. increased from 3% in 1976 to 12.8% in 2019 (Toole et al. 2020a). In particular, women’s participation in emerging scientific fields such as biotechnology and artificial intelligence (AI) remains notably low, despite evidence that their involvement adds significant value (Giczy et al., 2024).

Gender disparity exists not only in the number of inventors and patents but also in patents’ content, quality, and legal processes. For example, female applicants are more likely to be rejected, and upon rejection, they are less likely to appeal (Huang et al., 2022; Schuster and Goodman, 2025). Women are allowed to have a smaller fraction of their claims, and more texts are added to their claims during prosecution, which typically reduces patents’ value. Patents filed by women are less likely to be maintained (Jensen et al. 2018). Patents created by women tend to have fewer claims and lower technological impact compared to those filed by men (Sugimoto et al., 2015), and women are more likely to appear as co-inventors rather than lead inventors on patent documents (Whittington and Smith-Doerr, 2005). In addition, inventors’ genders impact the motive and purposes of the inventions and who benefits from the inventions. For instance, women engage in less commercial patenting and are more likely to discover female-focused ideas, such as biomedical devices focusing on women’s health (Koning et al. 2020).

Despite this disparity, women have created great inventions and have contributed significantly to science and technology (Comedy and Dougherty, 2018). For example, Anna Connelly invented the first outdoor fire escape (Uhl, 2018), and Hedy Lamarr invented a communication system that paved the way for wi-fi (Rhodes, 2012). It is worth acknowledging the substantial but often overlooked contributions of nearly 200,000 women in the U.S. who have played a vital role in creating over 600,000 patents in the past half-century, despite their names not receiving widespread recognition.

Potential reasons for gender gaps in inventing

Studies show that gender gaps in inventing may be rooted in social, cultural, economic, and political factors. Patents are primarily created within fields related to STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics), in which women are less likely to work. U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) reported that only 35% of the U.S. STEM workforce in 2021 are women (National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES), 2023). Even with similar educational backgrounds and previous career paths, women are less likely to apply for patents than men (Whittington and Smith-Doerr, 2008).

Previous studies found that government funding is increasingly fueling innovation in the U.S., demonstrated by the increased percentage of patents relying on research funded by the government (Fleming et al., 2019a). Organizations and inventors can benefit from patenting with knowledge created by government research, especially with constrained resources. Nevertheless, gender disparity may arise within this context. Researchers found that women are less likely to obtain research grants than men, and funding awarded to women tends to be lower than to men (Head et al., 2013; RissleR et al., 2020).

Some scholars have argued that the institutional and cultural structures of invention and commercialization have created barriers to women’s full participation (Lai, 2020). For example, female academics are often disproportionately burdened with non-research tasks, such as service or advising and counseling students (Ding et al., 2006). Women’s contributions to inventions are often undervalued and they are less likely to be acknowledged as inventors, even when their contributions are comparable to their male counterparts (Ross et al., 2022). This reduces women’s opportunities and success rates in research-related work, such as applying for funding, publishing articles, and filing for patents (Ceci and Williams, 2010). Therefore, systematic reform may be necessary to help protect women’s innovation products, such as an addition to the existing patent legal regime to acknowledge and protect unregistered patent rights (Marcowitz-Bitton et al., 2020).

Gender disparity in patenting may lead to profound consequences. The inventive potential of women and the value of their ideas and inventions may be under-recognized. Funding and other resources may be inadequate to help women invent and commercialize their inventions. This can lead to a loss of potential inventions, harming economic growth. In addition, the absence of women’s participation in inventing can result in a lack of diversity in innovative products. Because women are more likely to invent for other women (Koning et al., 2020, 2021), the shortage of women inventors may lead to fewer inventions that benefit women, fulfill women’s needs, and align with women’s values.

Research gap

Despite growing attention to the underrepresentation of women in patenting, most existing research has primarily focused on the quantity of patents filed by women, paying limited attention to potential disparities in the quality, characteristics, and types of inventions they produce. Studies that do compare patent characteristics by gender often concentrate on a single technological domain, such as the life sciences, or examine only a narrow set of metrics, typically citation counts or patent scope. Few have conducted a systematic, large-scale investigation of how gender differences manifest across a comprehensive set of patent indicators, including resource utilization, knowledge characteristics, and various dimensions of impact.

This study addresses these gaps by offering a comprehensive, multi-dimensional, longitudinal analysis of U.S. utility patents, shedding new light on how gender intersects with the nature, influence, and institutional environments of technological innovation.

Research questions

While prior studies have documented women’s underrepresentation in securing public funding for research and development (R&D) in certain domains (Holliday et al., 2014; Ley and Hamilton, 2008), it remains unclear whether and how this disparity extends to the context of commercial patenting. Moreover, no prior research has examined whether women and men differ in citing scientific publications in patent documents, despite such citations often being associated with the depth and quality of technological innovation. These two aspects can serve as indicators of inventors’ access to and engagement with key resources. Thus, we ask:

-

RQ1: How do inventor teams involving women utilize resources differently in the creation of patents (specifically, public support and scientific knowledge) compared to teams composed solely of male inventors?

Investigating this question will help illuminate gender disparities in the utilization of both financial and intellectual resources in the innovation process.

Second, gender differences in the content and knowledge characteristics of patents remain underexplored. These features, often referred to as ex-ante characteristics, capture the nature of the invention prior to its market impact or citation performance. Few studies have systematically examined these characteristics from a gender perspective. Therefore, we ask:

-

RQ2: How do patents by teams with different gender compositions differ in their knowledge-related characteristics, such as technological scope, combinatorial novelty, and originality?

Investigating this question contributes to our understanding of how gender relates to the substantive content and knowledge diversity of patented inventions.

Third, previous studies have shown that women-authored papers and patents tend to receive fewer citations than those authored by men. However, technological impact extends beyond simple citation counts. It also encompasses the breadth and nature of citations, for example, whether a patent is cited across diverse technological fields or whether it disrupts existing knowledge trajectories by being cited more than the prior art it builds upon. These aspects provide a richer understanding of an invention’s influence on technological development. Therefore, we ask:

-

RQ3: Do patents created by teams with different gender compositions exert different types and levels of technological impact?

Answering this question contributes new knowledge about how gender differences manifest in the nature of impact of patents.

Fourth, previous studies have demonstrated gender disparities in specific scientific and technological fields, particularly in life sciences and engineering (Ding et al., 2006; Whittington and Smith-Doerr, 2005). While examining gender disparity within a single domain is informative, comparing disparities across a broader set of major sectors can yield deeper insights into how institutional and disciplinary contexts shape inventorship.

In this study, we focus on five domains of high economic and strategic importance, and ask:

-

RQ4: How do gender disparities in patenting vary across fields, especially in strategically significant areas such as artificial intelligence, nanotechnology, biotechnology, civil engineering, and green technology?

Investigating this research question not only expands our understanding of gender disparity in underexplored domains, such as AI and green technology, but also helps identify which fields exhibit greater gender diversity and where women inventors thrive. Such comparative insights may reveal institutional practices or cultural factors from these fields that could inform policies aimed at reducing gender gaps in other areas.

Organizations play a critical role in shaping inventors’ opportunities and access to resources. Prior research has suggested that structural features of universities (such as flexible research environments and collaborative cultures) may support women’s innovation more than hierarchical corporate settings. However, few studies have systematically compared gender disparities across different types of organizations involved in patenting, such as corporations, academic institutions, and government agencies. To address this gap, we ask:

-

RQ5: Which organizational types (e.g., firms, universities, government agencies) are associated with greater participation by women inventors?

Exploring this question helps illuminate the institutional contexts in which women are more likely to contribute as inventors. By identifying organizational environments that foster gender diversity in innovation, our findings may inform organizational and policy-level interventions to support women’s participation in patenting across sectors.

Data

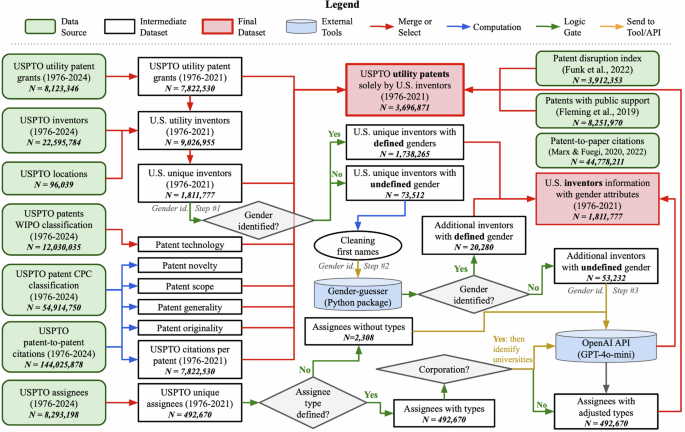

Patents created by U.S. inventors

We collected data on granted patents, inventors, assignees, locations, patent-to-patent citations, and technology classifications from the PatentsViewFootnote 2 open data platform (an initiative supported by the USPTO) in December 2024 (Toole et al., 2021). The process of data collection, cleaning, merging, and final construction is illustrated in the flowchart in Fig. 1.

There are three types of patents granted in the United States: utility patents, design patents, and plant patents. Among these, utility patents, also known as “patents for invention,” are the most common and are widely used in research as a proxy for overall inventive activity in the U.S. (Griliches, 1990; Sampat, 2018; Seymore, 2013; Wang and Lobo, 2024; Youn et al., 2015).Footnote 3 Accordingly, we focus exclusively on utility patents for this study. Also, the dataset includes two types of technology classifications. The first is the Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) system. The second is the sector and field classification scheme developed by the WIPO.Footnote 4

The initial dataset includes all utility patents filed between 1976 and September 30, 2024.Footnote 5 For our main analyses, we selected utility patents filed from 1976 through 2021. This subset includes 7,822,530 granted utility patents, 20,228,153 inventor-patent instances, and 3,834,487 unique inventors. Utility patents filed after 2021 are used only to compute forward-looking metrics such as citations, which require several years of data accumulation post-grant.

The USPTO routinely receives applications from foreign inventors (WIPO, 2021). Because this study focuses on U.S.-based inventors, we further restricted our dataset to 4,052,122 patents (51.8%) that were invented exclusively by U.S. inventors, excluding patents involving any non-U.S. inventors.Footnote 6 This selection was made possible by the inclusion of inventor country information in the dataset; we retained only those inventors whose country designation was listed as “US.” Footnote 7

Of the 3,834,487 distinct inventors in the full dataset, 1,856,323 (48.4%) are located in the United States. Among them, 1,811,777 contributed to patents created exclusively by U.S. inventors, resulting in 3,753,689 utility patents. This number was further reduced to 3,696,871 in our final dataset (highlighted by the red box in the upper middle of Fig. 1) after excluding patents involving inventors with unknown or missing gender information. This exclusion affected approximately 1.5% of the data, a proportion considered acceptable given the scope of our study.

To supplement our analyses with information not provided by the USPTO, we incorporated three additional datasets:

-

a patent-to-paper citation dataset (Marx, 2024; Marx and Fuegi, 2020, 2022), which links U.S. patents to scientific publications indexed in academic databases;

-

a dataset identifying patents that rely on public funding (Fleming et al., 2019a, b); and

-

a dataset containing the disruption index for U.S. patents (Funk et al., 2022; Park et al., 2023).

The procedures for merging and processing these datasets are detailed in Fig. 1.

Gender attributes

Identifying inventors genders

We employed a three-step approach to identify the gender of each inventor. This process builds upon the pre-generated gender codes developed by Toole et al. (2019), supplemented by an AI-assisted method, as described in this section.Footnote 8

Step #1: Pre-Generated Gender Code Using Name Databases

Because the USPTO does not collect gender information during the patent filing process, we rely on a pre-processed dataset developed by Toole et al. (2019), which uses probabilistic name-gender matching across two large databases: (1) IBM’s Global Name Recognition (GNR) system and (2) WIPO’s Worldwide Gender-Name Dictionary (WGND). The method applies a multi-step classification procedure based on first-name probabilities and inferred country-of-origin information. Full details are provided in Appendix A.

In our dataset, this baseline method successfully assigned a gender to 1,738,265 of the 1,811,777 (95.9%) distinct U.S.-based inventors. Among those identified, 1,509,486 (86.8%) were classified as male and 228,779 (13.2%) as female. The remaining 73,512 inventors either received an undefined label or were missing gender data entirely.

Step #2: Gender-Guesser Python Package

To address the 73,512 inventors with undefined gender information, we implemented two additional steps. The first involved using the GENDER-GUESSER (Pérez, 2016), a Python package for gender inference based on first names. This package draws on data from the “gender” program developed by Jörg Michael, which contains gender information for approximately 40,000 first names across multiple languages and cultures (Gecko, 2009).

The package produces one of six possible outputs for each name: male, mostly_male, female, mostly_female, andy (androgynous),Footnote 9 and unknown.Footnote 10 For the purposes of this study, we grouped male and mostly_male into a single “male” category, and female and mostly_female into a single “female” category. Names classified as andy or unknown were grouped into an “undefined” category. Applying this method to the 73,512 gender-undefined inventors, we were able to classify 15,624 as male and 4656 as female. The remaining 53,232 names remained undefined.

Step #3: LLM-Assisted Gender Classification

For the remaining 53,232 inventors whose gender could not be identified using the previous two steps, we employed a large language model (LLM) to infer gender. LLMs are a form of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) capable of contextual text analysis, reasoning, and content generation. In recent social science research, LLMs have been increasingly adopted for tasks such as data annotation, text generation, information extraction, and analysis, ranging from sentiment analysis (Miah et al., 2024), identification of political affiliations in social media posts (Törnberg, 2024), simulation of social behavior (Kim et al., 2025; Manning et al., 2024), and occupational task analysis (Eloundou et al., 2024; Wang et al., 2025). While concerns about transparency and replicability in using LLMs for research persist (Lin and Zhang, 2025), we argue that gender inference from names is a particularly suitable use case for LLMs, given their training on vast textual corpora that include culturally contextualized names.

For this task, we used GPT-4o-mini,Footnote 11 a cost-effective LLM developed by OpenAI, accessed via API. Prior to deployment, we engaged in iterative prompt engineering using randomly sampled names in OpenAI’s Playground environment.Footnote 12 To enhance the model’s contextual understanding, we constructed a dataset that included each inventor’s full name,Footnote 13 location (city, county, state, if available), patent titles, assignee information (including organizational name and location), and other relevant metadata associated with their patent filings.

In our final prompt (see Appendix B), we instructed GPT-4o-mini to infer the inventor’s gender using all contextual information provided. The model was asked to return JSON objects including gender code—“M” for male, “F” for female, and “U” for undefined, along with a brief explanation and a confidence score ranging from 0.0 to 1.0. For example, for the first name “Michael,” GPT-4o-mini responded: “Michael is a common male name” with a confidence score of 0.9. For the name Cuiyu Zhang, it responded: “Cuiyu Zhang is likely female based on the name’s structure, which is more common for female names in Chinese culture,” with a confidence score of 0.7.

To evaluate the validity of this LLM-assisted approach, we conducted a manual validation using 100 randomly-selected names for which gender had already been assigned by the USPTO (Toole et al., 2019) (Step #1). These names are considered high-confidence cases, as the USPTO approach is more likely to classify names with strong gender associations. We queried the gender of these 100 names using our LLM-assisted method and observed a 94% agreement between GPT-4o-mini and the USPTO-assigned gender codes.Footnote 14 Therefore, we concluded that GPT-4o-mini, when used with our prompt and contextual data, offers a level of accuracy comparable to the USPTO method, demonstrating that the LLM-assisted approach can, to a reasonable degree of accuracy, infer gender based on inventor names and accompanying metadata.

Applying this approach to the remaining 53,232 inventors, GPT-4o-mini initially classified 33,940 as male (63.7%), 3470 as female (6.5%), and 15,822 (29.7%) as undefined. Given that many names are genuinely gender-neutral or culturally ambiguous, and recognizing the impossibility of perfect classification, our goal was not to label every inventor but to do so with reasonable confidence. To that end, we retained only those gender inferences with a confidence score of 0.7 or higher, and assigned all others to the “undefined” category ("U”).

After this filtering step, the revised gender composition of the 53,232 previously unclassified inventors was as follows: 33,432 male (62.8%), 3425 female (6.4%), and 16,375 undefined (30.7%). A detailed breakdown of the number of inventors identified at each step is provided in Table 1.

Gender characteristics at the patent level

To enable patent-level analyses, we aggregated inventor gender information to the level of individual patents. We first removed 56,818 patents that included at least one inventor with an undefined gender, as the gender composition of these teams could not be accurately determined. These gender-unidentifiable patents represent only 1.5% of the entire dataset, a level of missingness that is widely considered acceptable in quantitative research. While this missingness is not completely random, it is attributable to systematic limitations in gender identification tools and does not pose a significant risk of bias to our analysis.Footnote 15

For the remaining 3,696,871 patents, we assigned the following three sets of gender-related attributes:

-

To examine whether the presence of women on a team influences invention characteristics, we created a binary variable, “with_women,” which takes the value 1 if at least one inventor is female, and 0 otherwise.

-

To study gender collaboration patterns, we constructed a categorical variable, “gender_collab_type,” indicating the gender composition of the inventor team. This variable takes one of three values: all-women team, all-men team, or mixed-gender team.

-

We also counted the number of male and female inventors on each patent. If no female inventors were present, the count of female inventors was set to 0.

Assignee types

Identifying organizational assignee types

An assignee refers to the individual or organization that holds the legal ownership rights to a patent. To investigate differences in gender composition and disparities across organizational types, we classified organizational assignees into three categories: government, universities, and private companies.

We began with 8,293,198 patent-assignee pairs (see Fig. 1), involving 492,670 unique assignees. From this pool, we selected 216,149 unique assignees associated with patents granted between 1976 and 2021 that were invented exclusively by U.S.-based inventors.Footnote 16

To classify these assignee organizations, we used a multi-step process combining structured data from the PatentsView dataset with an LLM assistance. First, we utilized pre-assigned assignee type codes to group entities into corporations, governments, and individuals. Next, for assignees without a valid type code, we applied GPT-4o-mini to classify organizations based on their name, patenting activity, and geographic information. Finally, because the USPTO often classifies universities under the broader category of corporations, we implemented an additional LLM-assisted step to identify universities within this group and distinguish them from private companies. The detailed classification procedure is provided in Appendix C.

After consolidating the results from all three steps, our final classification includes 924 (0.4%) government assignees, 2595 (1.2%) universities, 212,396 (98.3%) corporations, 175 individuals, and 59 unidentifiable assignees.

Classifying patents by assignee type

A single patent may have multiple assignees, potentially spanning different assignee types. Since our analysis focuses on whether patents owned by governments and universities differ from those owned by corporations in terms of gender composition and patent quality, we prioritized identifying government and university ownership.

We first classified a patent as government-owned if at least one of its assignees was identified as a government entity. Among the remaining patents, we then classified those with at least one university assignee as university-owned. The rest were classified based on their assignee type: corporation, individual, unidentified, or null (indicating missing assignee information).

This process resulted in 40,595 (1.1%) government-owned patents, 145,698 (3.9%) university-owned patents, 2,950,992 (79.8%) corporation-owned patents, 170 patents assigned to individuals, 61 unidentified patents, and 559,355 patents with null assignee information.Footnote 17

Ex-ante patent characteristics

To examine differences in the characteristics of patents produced by inventor teams with varying gender compositions, we compiled a set of widely used patent indicators. These indicators are divided into two categories: (1) ex-ante patent characteristics, described in this section, which capture attributes known at the time of patent filing or reflect the nature of the knowledge embedded in the patent; and (2) ex-post patent characteristics (Section “Ex-post patent characteristics”), which represent outcomes or impacts observed after the patent has been granted.

Patent scope

Patent scope refers to the breadth of technological domains an invention spans, typically measured by the number of distinct classification codes assigned to a patent. Broader scope often reflects greater technological complexity and integration across multiple knowledge areas, and has been associated with increased firm value and innovation performance (Barbieri et al. 2020; Lerner, 1994; Novelli, 2015; Wang et al. 2024). Historical trends also suggest a rise in scope over time, especially since the mid-20th century (Youn et al. 2015).

To measure patent scope, we use the Cooperative Patent Classification (CPC) system adopted by the USPTO. Each patent is assigned one or more CPC codes, which represent the non-trivial technical components disclosed in the invention (USPTO, 2015).Footnote 18 Following prior literature (Barbieri et al. 2020; Strumsky et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2024; Youn et al. 2015), we define the technological scope of a patent as the number of unique 4-digit CPC subclass codes it receives. Each subclass code corresponds to a distinct technical fields.Footnote 19

While our main focus is on 4-digit CPC codes, we also counted the number of full-digit subgroup codes as a control variable to account for the level of technical granularity.Footnote 20

To account for variation in team size, we also compute per-inventor scope by dividing the number of 4-digit CPC codes by the number of inventors listed on each patent.

Originality

To assess the diversity of knowledge sources incorporated into an invention, we computed the originality index, a widely adopted metric in patent studies (Breitzman and Thomas, 2015a; Hall et al., 2001; Hasan et al., 2009; Jaffe and Trajtenberg, 2002; Squicciarini et al., 2013; Su, 2022). This index measures the extent to which a patent builds upon prior inventions from different technological fields, based on its backward citations.

The originality score for a given patent p, denoted as Op, is calculated as:

where spt represents the share of backward citations made by patent p that fall under CPC 4-digit code t, and Np is the number of distinct 4-digit CPC codes among all cited patents. A higher Op value indicates that the cited prior art spans a broader range of technical fields, suggesting greater originality. In contrast, if a patent cites only prior work from a single field, the originality score Op equals zero.

Combinatorial novelty

Inventions are often conceptualized as novel combinations of existing technologies (Arthur, 2009; Schumpeter, 1934; Wagner and Rosen, 2014; Youn et al., 2015). Although novelty is a formal requirement for patentability (35 U.S. Code § 102), its evaluation by patent examiners is inherently subjective and context-dependent, making it difficult to quantify systematically. To address this challenge, researchers have developed empirical methods to measure the novelty of knowledge recombinations in patents and scientific publications, demonstrating their predictive value for future impact (Kim et al., 2016; Mukherjee et al., 2016; Uzzi et al., 2013; Youn et al., 2015).

We adopt a classification-based method developed by Strumsky and Lobo (2015) to assess the combinatorial novelty of patents. This approach categorizes patents according to whether they introduce new technological components (defined using full-digit CPC codes) and/or novel combinations of those components. The taxonomy includes four categories: (1) Origination, where all assigned components are new to the patent system; (2) Novel Combination, which mixes new and existing components; (3) Combination, which uses only previously known components but forms new pairwise combinations; and (4) Refinement, in which both the components and their combinations have appeared in prior patents.

Strumsky and Lobo (2015) reported a steady decline in Origination and Novel Combination patents, with each comprising less than 1% of all patents after 1990. The majority of novel activity in recent decades arises from new combinations of existing components, rather than from entirely new technologies. To reflect this reality and avoid highly imbalanced categories, many studies have adopted a binary definition of novelty, classifying patents as novel if they introduce at least one new pairwise combination of components, regardless of whether the components themselves are new (Verhoeven et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2024). Under this approach, the first three categories defined by Strumsky and Lobo (2015)—Origination, Novel Combination, and Combination—are grouped together as “novel,” while only the Refinement category is considered “non-novel.”

Following this logic, we define a binary indicator of combinatorial novelty, assigning a value of 1 to patents that introduce new components or new combinations (i.e., non-Refinement patents), and 0 to those that introduce neither (i.e., Refinement patents). Using this classification, we identified 1,806,610 patents (48.9%) in our dataset as novel, and 1,890,261 patents (51.1%) as Refinements.Footnote 21

Patents relying on public support

To examine how inventors of different genders rely on publicly funded research, we utilized a dataset of government-supported patents compiled by Fleming et al. (2019b).Footnote 22 This dataset classifies a patent as relying on public research if it meets at least one of the following criteria: (1) the patent is owned by the government, (2) the patent explicitly acknowledges government funding, or (3) the patent cites a prior patent or publication that satisfies either of the first two criteria or is authored by an individual affiliated with a U.S. government institution (Fleming et al., 2019a).

The first two types are considered direct public support, as they reflect formal and financial backing from government sources. The third type captures indirect public support, representing the knowledge spillover effects of publicly funded research. In our analysis, we group both direct and indirect support under a single category (Relying on Public Support) to capture any reliance on knowledge created with public funding, support, or resource.

Using this classification, we identified 654,878 patents (17.7%) as relying on public support, while the remaining 82.3% did not show any such dependence.

Patents relying on science

Scientific research and discovery have long served as key sources of inspiration for inventions and technological advancement. One common method of mapping the flow of knowledge from science to technology is through analyzing patent citations to scientific publications (Jaffe et al., 1993, 2000; Meyer, 2000; Narin and Noma, 1985; Tussen et al., 2000).

In this study, we used an open-access dataset developed by Marx and Fuegi (2020), which links patents granted worldwide to scientific articles published since the 1800s (Marx and Fuegi, 2020, 2022). This dataset identifies approximately 22 million patent citations to science (PCS), constructed through high-precision matching of the non-patent literature (NPL) section in patent documents to entries in bibliographic databases such as MEDLINE, Web of Science, and CrossRef. The authors employed a combination of rule-based parsing, metadata alignment, and manual validation to ensure accuracy and global coverage.

Using this dataset, we examine whether the gender composition of inventor teams influences the extent to which patents rely on scientific knowledge. We focus on two key measures: (1) the number of scientific publications cited in a patent, which reflects the overall degree of reliance on science; and (2) the number of citations per inventor, which adjusts for team size and approximates individual-level engagement with scientific research.

Ex-post patent characteristics

Ex-post patent characteristics are attributes that become observable only after a patent is granted, often reflecting its technological or commercial impact. In this study, we use three widely adopted ex-post measures to assess the realized influence of patents across different inventor team gender compositions: forward citations, the generality index, and the disruption index. These capture, respectively, the extent of a patent’s influence on subsequent inventions, the breadth of that influence across fields, and whether the patent disrupts or consolidates existing citation structures.

Forward citations

Forward citations made by subsequent patents to a focal patent are a widely used proxy for a patent’s technological impact and knowledge diffusion (Barbieri et al., 2020; Fleming and Sorenson, 2004; Hall et al., 2001; Trajtenberg and Jaffe, 2002). Higher forward citation counts generally signal greater influence on future innovations and broader spillover effects (Jaffe et al., 2000).

In this study, we capture forward citation impact using two measures: (1) a count variable representing the number of forward citations a patent receives within five years of its grant date, and (2) a binary variable indicating whether the patent is a “top-cited” or “hit” patent, defined as being in the top 10% of forward citations among all patents granted in the same year. The inclusion of the binary variable accounts for the highly skewed and potentially uneven distribution of citations across patents, which may obscure differences between inventor teams of different gender compositions. This approach follows prior studies by Uzzi et al. (2013) and Mukherjee et al. (2016).

Generality

The generality index captures the extent to which a patent influences a broad range of technological domains (Barbieri et al., 2020; Trajtenberg and Jaffe, 2002). A higher generality score indicates that a patent is cited by subsequent patents from a wider variety of fields, reflecting its cross-domain applicability.

In this study, we adopt a modified version of the generality index proposed by Squicciarini et al. (2013), calculated over a five-year citation window. Let Yp represent the set of patents that cite focal patent p within five years of its grant date. For each citing patent y ∈ Yp, let My be the set of full-digit CPC codes, and Ny be the corresponding 4-digit CPC codes.

The union of all 4-digit CPC codes across citing patents is denoted as:

The generality index Gp for patent p is computed as:

where βyn represents the share of full-digit CPC codes in y that fall under the 4-digit code n, calculated as:

Here, Tyn is the number of full-digit codes in y that map to a 4-digit code n, and ∣My∣ is the total number of full-digit codes in y.

This index ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating that the citing patents span a more diverse set of technological classes, suggesting broader generality of the cited patent.

Disruption

While forward citations measure the volume of a patent’s subsequent influence, and generality captures the breadth of its impact across fields, neither metric reflects how a patent affects the direction of future innovation. Specifically, they do not indicate whether a patent reinforces existing technological trajectories or breaks away from them to establish new paths. Therefore, we incorporate the Consolidating-or-Disruptive index (CD index), a measure that captures how much a patent destabilizes the existing knowledge structure by redirecting the flow of citations (Funk and Owen-Smith, 2017).

The CD index ranges from −1 to 1, with positive values indicating greater disruption. A patent is considered disruptive if future patents tend to cite it but not its predecessors, suggesting that it redirects the flow of knowledge and introduces a novel technological direction. In contrast, a consolidating patent is one that is frequently co-cited with its prior art, reinforcing existing knowledge structures and extending established technological trajectories without initiating a new path (Park et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2019).

Formally, the CD index at time t is computed as:

where fi indicates whether a later patent i cites the focal patent, bi indicates whether it cites one of the focal patent’s predecessors, and nt is the number of patents citing either the focal patent or its predecessors as of time t (Park et al., 2023).

We use a pre-computed dataset of CD indices for patents granted between 1976 and 2010 (Funk et al., 2022), which includes three time horizons: five-year, ten-year, and cumulative as of 2017.Footnote 23 To maintain consistency with our forward citation and generality analyses, we focus on the five-year CD index (CD5).

In addition to using the continuous CD index, we construct a binary “disruption hit” or “top disruptive” indicator that equals 1 if a patent’s CD5 score falls within the top 10% of its grant-year cohort, and 0 otherwise. This binary measure captures the distributional skewness of disruption and allows us to examine whether certain inventor team characteristics are associated with an increased likelihood of producing highly disruptive patents (Mukherjee et al., 2016).

Descriptive statistics for variables discussed in Section “Data” are presented in Table 2.

Methods

Regression models

To address RQs 1–4, we estimate a set of linear regression models to examine whether the presence or absence of female inventors is associated with differences in patent characteristics and outcomes. All models use patent-level indicators as dependent variables (denoted as \(Indi{c}_{p}^{A}\)) and are estimated with and without field-level fixed effects based on WIPO technology classifications.

Model #1: Baseline model: with vs. without women

Model #1-1: Baseline model without field controls

This model (Equation (6)) uses a binary indicator variable \(With.Wome{n}_{p}^{0,1}\) as the independent variable, which equals 1 if a patent includes at least one female inventor, and 0 otherwise. No field fixed effects are included.

Model #1-2: Baseline model with WIPO field controls

This model (Equation (7)) includes the same independent variables as Model #1-1, with the addition of field-level fixed effects (\(Fiel{d}_{p}^{0,1}\)) based on WIPO technology categories.Footnote 24 Field fixed effects are included to account for systematic differences across technological domains, such as variation in patenting practices, team composition norms, or citation behaviors, that may confound the relationship between gender composition and patent outcomes. Controlling for field-specific characteristics helps isolate the effect of gender composition from underlying differences across technology areas.

Model #2: Gender collaboration types

Model #2-1: Gender collaboration types, without field controls

Recognizing that patents involving women can reflect different team structures—either all-female teams or mixed-gender teams—we define \(Gender.Collab.Typ{e}_{p}^{0,1}\) as a categorical variable capturing the type of gender composition.Footnote 25 This model (Equation (8)) assesses whether gender collaboration type explains variation in patent outcomes.

Model #2-2: Gender collaboration types, with field controls

This model (Equation (9)) extends Model #2-1 by controlling for field-level differences using WIPO field indicators.Footnote 26

All models in Model #1 and Model #2 are controled for filing year (Filing. Yearp). In all these models, control variables (Controlsp) differ slightly depending on the indicator, but all models include four common controls: the number of backward citations, the number of claims, team size, and technological maturity. Backward citations capture how many prior patents are cited by the focal patent, serving as a proxy for the depth of prior knowledge integration and often correlating with patent value and significance (Harhoff et al., 2003; Thompson, 2016).Footnote 27 The number of claims can reflect the invention’s potential commercial value, and has been linked to technological breadth and firm performance (Lanjouw and Schankerman, 2004; Novelli, 2015; Tong and Frame, 1994). Team size, defined by the number of inventors, is associated with patent quality and scope, as larger teams tend to generate more influential patents (Breitzman and Thomas, 2015b; Wu et al., 2019).

Technological maturity is measured as the natural logarithm of the cumulative number of patents filed in the primary full-digit CPC subclass up to the filing year, indicating the developmental stage of the technology domain (Barbieri et al., 2020). More mature fields typically offer a broader landscape of prior technologies to build upon. To address potential issues with taking the logarithm of zero, one is added to the cumulative count prior to transformation (Feng et al., 2014).

In addition to these common controls, models for the scope, scientific papers cited, and novelty include the number of full-digit CPC codes to account for variation in technical component size and complexity. For the generality and disruption indicators, we also control for forward citations within 5 years windows to adjust for differences in exposure and citation opportunity.

Model #3: assignee type and gender disparity

To address RQ5, we estimate regression models where the dependent variable is a binary indicator of whether a patent includes at least one woman inventor, and the key independent variable is the assignee type (see Section “Assignee types”). We estimate two versions of the model: one without field-level controls (Model #3-1) and one with field-level fixed effects based on WIPO technology classifications (Model #3-2), as specified in Eqs. (10) and (11), respectively.

In both models, we control for filing year, team size, number of claims, number of full-digit CPC codes, and backward citations.

Model selection

The selection of regression models was guided by the data type and distribution of each patent indicator. Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression was used for continuous indicators, such as originality, generality, and disruption. Binary indicators, such as novelty and public support, were analyzed using logistic regression. For count-based indicators, we distinguished between two cases. Poisson regression was applied to count variables without zero values, such as scope. In contrast, for indicators that include zero counts, such as forward citations and the number of scientific papers cited, we employed negative binomial regression to account for overdispersion.Footnote 28

Sampling strategy

For Model #3, we estimate regression models only on the full dataset. For Models #1 and #2, we supplement full-sample regressions with an undersampling approach to address the significant class imbalance between patents with and without women inventors. Given that patents without women account for 82.4% of the data, this imbalance may introduce bias and reduce the sensitivity of models to detect patterns associated with underrepresented groups. Undersampling the majority class (patents without women) helps balance the sample, potentially improving both model interpretability and predictive performance (Spelmen and Porkodi, 2018; Yang et al., 2021). Specifically, we randomly sample a subset of patents without women to match the number of patents with women and re-estimate the regression models on the balanced dataset. To assess the robustness of our findings, we repeat this sampling process ten times using different random seeds, generating distinct subsets and running the same regression model on each.

To address RQ4, which examines whether gender disparities persist across different domains, we selected five representative fields and applied the same set of regression models to field-specific subsets of patents. The selected fields are (1) civil engineering, (2) artificial intelligence (AI), (3) nanotechnology, (4) biotechnology, and (5) green technology (or climate change mitigation and adaptation technology, CCMA technology). These fields were chosen to capture variation in disciplinary culture and gender representation. Civil engineering is a traditionally male-dominated field (Manesh et al., 2020);Footnote 29 AI is an emerging domain with rapidly evolving inventor demographics (Huang et al., 2023);Footnote 30 nanotechnology has received considerable policy and scholarly attention regarding its development (Hulla et al., 2015);Footnote 31 and biotechnology is known for relatively higher female participation compared to other STEM fields (McMillan, 2009).Footnote 32 Green technology is included due to its growing importance in addressing climate change and its increasing visibility in sustainability-focused innovation policy. Given the strong policy incentives and societal relevance (Wang et al. 2024), this field may attract a more diverse pool of inventors and provide insight into whether gender disparities persist even in areas aligned with global sustainability goals.Footnote 33

In total, we conducted 64 sets of regression analyses across the four main models. Each model was estimated in 16 different settings: one using the full dataset, ten using undersampled data to address class imbalance, and five applied to the five selected technology domains. Within each setting, we ran separate regressions for each of the 12 dependent variables described in Sections “Ex-ante patent characteristics” and “Ex-post patent characteristics”.

Results

Descriptive statistics

Our results show that patenting in the U.S. is overwhelmingly dominated by men. It is estimated that approximately 51% of the U.S. population is female,Footnote 34 and women account for 47% of the U.S. workforce (U.S. Census Bureau, 2023).Footnote 35 However, within the 1.78 million distinct U.S. inventors, only 232,534 (13.1%) are women. Among the 3.7 million U.S. patents in our dataset, only 651,327 (17.6%) are filed with at least one female inventor. In these 651,327 patents, most of them are created with both women and men (551,785, 84.7%), and only 99,542 are created by only women, accounting for 2.7% of the patents in our dataset.

The summarty statistics of numerical variables conditioned on gender collaboration is shown in Table 3,Footnote 36 and the time series of patents’ characteristics are presented in Fig. 3. The simplified regression results of Models #1 and #2 are presented in Table 4, with full results available in Appendices E and F. An illustrative visualization of the main findings from these two models is shown in Fig. 6. The results of Model #3 are reported in Table 6. Additionally, we provide an alternative specification as a robustness check in Appendix G.

Women inventors are growing, but still underrepresented

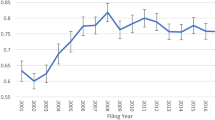

Undeniably, women’s participation in patenting has increased over the past four decades. The share of patents filed with at least one female inventor rose from 4.4% in 1976 to 25.8% in 2021 (blue line in Fig. 2). This growth has been driven primarily by mixed-gender collaborations—patents involving both male and female inventors—reaching 22.8% in 2021. In contrast, patents produced solely by all-women teams remain rare and have even declined during the period under analysis, consistently fluctuating below 3% and showing a noticeable drop in the 2000s (orange line in Fig. 2).

Time series of women’s participation in U.S. patenting, 1976-2021. The blue line shows the percentage of patents with at least one female inventor. The orange line shows the percentage of patents invented exclusively by all-women teams. The green line indicates the percentage of inventor-patent pairs in which the inventor is a woman. The red line reflects the share of distinct inventors who are women.

The overall percentage of female inventors has also grown over time (green line in Fig. 2). In 1976, less than 2% of inventors were women. By 2021, this figure had risen to over 12%. Despite this progress, the gender gap remains substantial. Moreover, the pace of change appears to have slowed in recent decades: while the share of women inventors more than doubled from 3.5% in 1980 to 9.1% in 2000, it increased only modestly from 9.1% to 11.8% between 2000 and 2020.

Mixed-gender teams cite more science and better leverage public support

In response to RQ1, our findings demonstrate that the gender composition of inventor teams significantly influences their use of scientific knowledge and public support. Descriptive statistics in Table 3 and time series patterns in Fig. 3D, F, and G offer preliminary insights, while Table 4 summarizes the regression results from Models #1 and #2.Footnote 37

Time series panels of 16 selected characteristics of U.S. patents, grouped by gender composition of inventor teams. Blue lines represent patents by all-female teams, green lines by all-male teams, red lines by mixed-gender teams, and orange lines by patents with at least one female inventor. Note that the orange category includes both the blue and red groups.

Reliance on science

Specifically, patents filed by all-male teams cite an average of 4.3 scientific papers. In contrast, all-female teams cite 6.2 papers on average (~44% more), and mixed-gender teams cite as many as 13.2 papers. The regression results from Model #1 confirm this pattern (Table 4). The coefficient for the variable With. Women is positive and statistically significant in the full sample and across five representative domains, with p < 0.001 in all but two fields (AI and nanotechnology). This suggests that the presence of women is consistently associated with increased use of scientific knowledge in the inventive process. Specifically, patents with at least one female inventor cite 99.5% more scientific papers than those without, holding all else constant. When controlling for technical fields, the increase remains statistically significant at 9.9%. Among the five focal domains, green technology exhibits the most substantial effect, with patents by teams including women citing 136.3% more scientific papers.

Results of Model #2, which distinguishes among all-male, all-female, and mixed-gender teams, reveals a more nuanced gradient. Mixed-gender teams consistently cite the most scientific papers, even after accounting for team size. All-female teams follow, and all-male teams cite the fewest. Without field controls, all-male teams cite 51.4% fewer papers than mixed-gender teams, and all-female teams cite 21.5% fewer. This ranking remains stable across all five technical domains.

Reliance on public support

When it comes to the use of public support, a more complex picture emerges. Mixed-gender teams are most likely to rely on public funding—30.8% of their patents reference government-sponsored research or benefit from direct government support. In comparison, only 21.9% of all-male and 18.1% of all-female patents do so.

Previous studies have documented a general rise in U.S. patents relying on federally funded science (Fleming et al., 2019a). Our data supports this trend. As shown in Fig. 3D, the proportion of gender-collaborative patents relying on public support rose from 16.4% in 1980 to 31.5% in 2012. In the same year, 25.3% of male-invented patents and 20.3% of female-invented patents were linked to public support.Footnote 38

Model #1 shows that, without controlling for field, the presence of women in the inventor team increases the odds of public support utilization by 13.3%. However, when technical fields are controlled, the effect slightly reverses: women’s presence is associated with a 1.8% reduction in the odds. Model #2 indicates that both all-female and all-male teams are less likely than mixed-gender teams to utilize public support, with reductions of 29.2% and 16.9%, respectively.Footnote 39 This suggests that mixed-gender collaboration is particularly conducive to drawing on publicly supported science.Footnote 40

Finally, we find that women inventors in universities are significantly more likely to utilize publicly supported research than their counterparts in corporate settings. Overall, 19.3% of patents associated with public support include at least one female inventor. However, in corporate-owned patents, only 18.6% of those involving public support include women, whereas in university-owned patents, this number rises to 31.9%.Footnote 41 Looking from another angle, when women are on the inventor team, only 25.8% of corporate patents use public support, while in universities, as high as 73.7% of women-participated patents are public-supported. This suggests that women in academia are significantly more likely to engage with publicly funded research in their inventive activity—nearly three times more than women in industry, and even more so than their male colleagues in academia.

In response to RQ1, our analysis shows that inventor teams with different gender compositions utilize resources in distinct ways: mixed-gender teams consistently cite the most scientific knowledge and are most likely to leverage public support. In contrast, all-female and all-male teams cite fewer scientific papers, with all-female teams generally citing more than all-male teams, while public support is least utilized by all-female teams in industry but most utilized by women in academia.

Gender composition shapes the scope, novelty, and originality of patents

Addressing RQ2, which examines how gender composition relates to the ex-ante knowledge characteristics of patents, we find systematic differences across three dimensions: scope, novelty, and originality.

Scope

Descriptive statistics suggest that patents from mixed-gender teams exhibit the broadest technological scope, as measured by both 4-digit and full-digit CPC codes (Table 3; Fig. 3H, J). All-male teams tend to have slightly broader scope than all-female teams overall.Footnote 42 Since a broader technological scope is often correlated with team size (larger teams typically bring more diverse expertise), it is important to control for this factor.Footnote 43 Mixed-gender teams, by definition, must include at least two inventors and often tend to be larger on average. After controlling for team size and other covariates in Model #1 and Model #2, we find that mixed-gender teams still exhibit slightly but significantly broader scope than same-gender teams. Specifically, patents from all-female teams have 3.9% fewer 4-digit CPC codes, and all-male teams have 3.1% fewer, compared to those from mixed-gender teams. However, this effect does not appear in certain technical fields, such as AI, biotechnology, nanotechnology, and green technology, where gender composition does not significantly affect scope.

Interestingly, when scope is normalized by team size (i.e., 4-digit CPC codes per inventor), Model #1 reveals that the inclusion of women is slightly negatively associated with per-inventor scope. However, this finding is clarified in Model #2, which shows that the lower per-inventor scope in mixed-gender teams drives this relationship. In fact, all-female teams exhibit the highest scope per inventor, followed by all-male teams, with mixed-gender teams showing the lowest. Specifically, on a balanced subset controlling for WIPO fields, all-female teams have 0.61 more 4-digit CPC codes per inventor than mixed-gender teams, while all-male teams have 0.29 more than mixed-gender teams. This trend holds consistently across the five representative domains. These findings suggest that while mixed-gender teams cover more ground collectively, all-female teams may contribute more technical breadth per individual.

Novelty

Our analysis indicates that women’s participation in inventor teams is associated with higher novelty in patents. Model #1 shows that, controlling for WIPO technical fields, including at least one female inventor increases the odds of a patent being novel by 8.7%. This effect is especially pronounced in civil engineering, where the odds increase by 15.5%.

Model #2 further reveals that while the effect of all-female teams on novelty is generally not statistically significant, all-male teams consistently reduce the likelihood of novelty. For instance, on a balanced subset of the data with WIPO field controls, patents from all-male teams are 8.8% less likely to be novel than those from mixed-gender teams. Again, this effect is strongest in civil engineering, where the reduction reaches 13.9%. These results suggest that including women in inventor teams—particularly in collaborative, mixed-gender settings—enhances the likelihood of producing novel inventions.

Originality

Originality, measured as the technological diversity of prior art cited, shows less variation across gender compositions. Figure 3K and descriptive statistics in Table 2 indicate that mixed-gender teams tend to have slightly higher originality scores (mean = 0.663), followed by all-male teams (mean = 0.650), and then all-female teams (mean = 0.642). Model #1 confirms a small but statistically significant effect: including women increases originality scores by approximately 0.005 points, with p < 0.001.

Model #2 shows that while mixed-gender teams have the highest average originality, the gap between all-male and all-female teams is minimal, with all-female teams slightly outperforming all-male teams. However, the pattern varies across technical domains. In civil engineering, including women increases originality, but the opposite is observed in AI, biotechnology, and green technology. In these latter fields, all-male teams tend to produce more original patents, though the differences are modest, and the p-values for nanotechnology are not statistically significant.

In sum, mixed-gender teams consistently produce patents with broader overall technological scope, greater novelty, and slightly higher originality than same-gender teams. However, when considering scope on a per-inventor basis, all-female teams outperform both mixed-gender and all-male teams. This indicates that while mixed-gender collaboration expands collective technical coverage, all-female teams may engage more deeply or broadly per contributor. Additionally, women’s participation, especially in collaborative or academic settings, enhances the likelihood of producing novel and original inventions, particularly in domains such as civil engineering.

Women-invented patents receive fewer citations but are more disruptive

Addressing RQ3, we examine how gender composition relates to the impact of patents, including forward citations, generality, and disruption. Our findings reveal important differences in how patents from teams with different gender compositions are recognized and influence subsequent innovation.

Forward citations

Our analysis shows that patents involving women inventors receive significantly fewer citations than those created by all-male teams. This difference is consistent over time (see Fig. 3L, O). On average, patents from all-male teams receive 3.17 citations within five years of filing, compared to only 2.08 citations for patents from all-female teams.

Regression results from Model #1 confirm this pattern (Table 4): including women in inventor teams is associated with a 10.7% reduction in forward citations. This effect is particularly pronounced in civil engineering and biotechnology, where citations decline by 14.6% and 22.2%, respectively, when women are included. However, including women slightly increases the likelihood of a patent being in the top 10% most cited patents by 0.8%. Model #2 further reveals that all-male teams receive 11.8% more citations than mixed-gender teams, while all-female teams receive 0.9% fewer citations than mixed-gender teams. Similarly, the probability of being among the top 10% cited patents is highest for all-male teams (1.3% higher than mixed-gender), and slightly lower for all-female teams, although the differences are small.

An exception to this general pattern is observed in green technology. In this domain, all-female teams produce the most cited patents, receiving 17.5% more citations than mixed-gender teams. All-male teams also perform better than mixed-gender teams in green technology, with a 9.8% citation advantage.

Generality

Generality (ranging from 0 to 1) captures the breadth of a patent’s impact across different technological fields (see Section “Generality”). Regression results from both Model #1 and Model #2 indicate that patents involving women are slightly more general, with an average increase of 0.0073. Among all team types, mixed-gender teams produce patents with the highest generality. When controlling for WIPO technology fields, all-female teams show slightly higher generality than all-male teams, though still lower than mixed-gender teams. These findings suggest that including women, particularly within gender-diverse teams, enhances the cross-domain influence of patented inventions.

Disruption

In terms of disruption (measured using the five-year disruption index, see Section “Disruption”), average values are 0.101 for all-male teams, 0.094 for all-female teams, and 0.065 for mixed-gender teams. Although the raw averages suggest that all-male teams produce slightly more disruptive patents, this relationship reverses when controlling for relevant variables. Model #1 results show that including women in inventor teams slightly increases the disruption score by 0.01. This effect is particularly evident in biotechnology and green technology, though not significant in the other three representative domains. Model #2 reveals that mixed-gender teams produce more disruptive patents than same-gender teams, even after accounting for field and team size. Among same-gender teams, all-female teams generate more disruptive patents than all-male teams.Footnote 44

Although including women slightly decreases the likelihood of a patent being in the top 10% of disruption scores (by 1.4%), all-female teams, surprisingly, have the highest odds of producing top-disruptive patents. On a balanced dataset with WIPO field controls, all-female teams are 8.7% more likely than mixed-gender teams to be in the top decile of disruption, while all-male teams are 8.1% less likely.

Women in universities are more likely to invent

Prior research has found that women in academia are more likely to engage in patenting activity than women in other sectors (Sugimoto et al., 2015). Addressing our RQ5, we extend this evidence through an updated analysis using patent data through 2021.

As shown in Table 5, corporate-owned patents—while making up 96.0% of all utility patents—have the lowest rate of women participation, with only 17.9% involving at least one female inventor. Government-owned patents show slightly higher participation at 19.8%. University-owned patents, however, exhibit substantially greater gender inclusion: 33.6% involve women inventors, nearly double the rate seen in corporate patents. This pattern is confirmed by the regression results in Model #3 (Table 6). Whether or not technological fields are controlled for, the relationship remains consistent: government-owned patents are 37.8% more likely to include women inventors, and university-owned patents are 112.3% more likely to do so, and both effects are statistically significant at p < 0.001.

Further supporting this pattern, Table 1 shows that only 13.1% of inventors in the overall dataset are women. This share drops to just 9.1% among inventors on corporate patents but rises to 16.0% for inventors on university-owned patents, representing a 76% increase relative to corporations.

This trend is also reflected at the individual organization level. On average, each university exhibits a higher rate of female inventors (14.1%) and a higher share of patents with at least one female contributor (26.7%), compared to corporations, where the corresponding averages are only 6.8% and 11.1%, respectively, less than half the levels observed in universities.

As discussed in Section “Women inventors are growing, but still underrepresented”, women’s participation in patenting has increased over time (Fig. 4), and this upward trend is evident across all types of organizations. However, the rate of growth is especially pronounced in universities, where participation is consistently higher than in corporations. As shown in Fig. 4, the percentage of academic patents involving women inventors rose from 8.3% in 1976 to over 40% in 2021. In contrast, only 26.2% of corporate-owned patents in 2021 included women inventors.

Nevertheless, some organizations stand out for their success in engaging women in the inventive process. We identified 15,257 organizations whose entire patent portfolios involve women inventors, examples include A.M. Surgical, CoAxia, Sakti3, and In2Bones, many of which are in the biotechnology or medical device sectors. Moreover, 5,101 organizations have inventor teams that are over 80% female. Among them are companies such as Chanel Parfums Beauté, Venus by Maria Tash, Hair Blast, Martha Stewart Living Omnimedia, and Lashify, many of which produce beauty, wellness, or women-oriented consumer products. This suggests that women inventors are not only participating in innovation but are particularly active in developing products that directly serve women consumers, consistent with previous findings by Koning et al. (2021).Footnote 45

Among universities, several institutions stand out for combining high patenting activity with high levels of women’s participation. For example, Hampton University leads with 84.6% (22 out of 26) of its patents involving women inventors, followed by Creighton University (52.5%), the University of North Carolina (49.0%), the University of Kansas (48.2%), and Boise State University (46.8%). Saint Louis University also stands out, with 45.2% of its patents involving women and a high female inventor rate of 32.3%. Other notable universities and research institutions with high levels of women participation include the Wistar Institute of Anatomy and Biology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Fox Chase Cancer Center, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, and Oregon Health & Science University.

The U.S. government agencies also exhibit strong women participation in certain cases. For instance, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has 54.4% of its patents involving women inventors. Similarly, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (50.6%), the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (50.1%), and the U.S. National Institutes of Health, Office of Technology Transfer (46.3%), all show relatively high levels of women's participation in patenting.

Gender disparity varies across technological domains

We found that while women’s participation in all fields has increased, the magnitude of growth varies significantly across domains (Fig. 5).Footnote 46 For instance, in the chemistry sector, women’s participation is relatively high and has grown substantially, particularly in biotechnology, organic fine chemistry, nanotechnology, and pharmaceuticals. By 2021, more than half (55.0%) of biotechnology patents involved at least one female inventor, which is a remarkable milestone.

Moreover, among the top patent-active companies with the highest rates of women participation, a substantial portion operate in biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, nanotechnology, and medical devices. Many of these firms focus on areas such as molecular diagnostics, gene therapy, advanced biomaterials, ultrasound imaging, or targeted therapeutics. Others are active in emerging technology sectors like nanotechnology, energy storage, consumer electronics, entertainment, or software. A number of companies also specialize in wellness, personal care, or protective equipment, domains often associated with caregiving or women’s health. This distribution reinforces the pattern that women inventors are especially active in fields with strong academic linkages and societal relevance, particularly those oriented-toward health, well-being, and inclusive technology.

On the other hand, certain fields continue to show persistently low levels of women’s participation, even after four decades of development. These include Mechanical Elements, Civil Engineering, Machine Tools, Engines, Pumps and Turbines, and Thermal Processes and Apparatus. For example, by 2021, only 9.1% of patents in the field of Mechanical Elements involved women inventors, nearly six times lower than in Biotechnology. Civil Engineering also remains low, with just 12.0% of patents including women contributors.

This pattern aligns with prior findings that women’s representation in science and technology varies across disciplines. For example, women make up a larger share of the workforce in biology and chemistry than in fields like engineering and computer science. According to the National Science Foundation, 46% of biological, agricultural, and life scientists are women, compared to just 16% of engineers (Cheryan et al., 2017). Our analysis suggests that these workforce imbalances are echoed in patenting outcomes: fields with more women professionals tend to produce more patents with female inventors. However, even in relatively gender-balanced fields, women patent at lower rates than men, pointing to persistent structural or institutional barriers.Footnote 47

Artificial Intelligence (purple line in Fig. 5), an important and rapidly emerging field with the potential to transform nearly every sector of the economy and society, exhibits a moderate level of women’s participation. While the share of AI patents with women inventors has grown from less than 5% in 1976 to 30.8% in 2021, this still lags considerably behind fields such as Biotechnology. This indicates that gender disparities persist even in newer, high-impact technological domains. Further underscoring this disparity, we manually inspected the top 100 inventors with the most AI patents and found that only four of them are women, just 4% of the list. This is particularly concerning given AI’s increasing role in shaping not only the future of technology and society, but also the very process of invention itself.Footnote 48

Beyond participation levels, gender disparities in patent characteristics also vary notably across technological domains. Figure 6d illustrates these differences for four representative fields: AI, green technology, biotechnology, and civil engineering.Footnote 49 A consistent pattern across all domains is that patents involving women tend to receive fewer forward citations. However, the nature and magnitude of gender-based differences in other patent characteristics vary by field. For example, in green technology, patents created by women-inventor teams are significantly more likely to draw on public support and cite scientific publications, suggesting higher engagement with public and academic resources, though their impact remains relatively limited. Biotechnology patents with female inventors tend to be more disruptive, indicating a stronger break from existing technological trajectories and greater potential to open new innovation pathways. However, these patents often have narrower technological scope and attract fewer citations. Civil engineering patents involving women, on the other hand, are significantly more original, drawing from a more diverse technological base, and tend to have broader subsequent impact across fields.

a Comparison between patents with female inventors and those without (gray). b Comparison between patents with female inventors and those without (gray) under four conditions. c Comparison among patents created by all-women teams, all-men teams, and mixed-gender teams. d Comparison of patents involving female inventors across four domains with those without female inventors. All values represent normalized regression coefficients (scaled between − 1 and 1) for illustrative comparison. Filled circles indicate statistically significant coefficients (p < 0.05), while unfilled circles indicate non-significant ones.

In summary, gender disparities in patent characteristics are not uniform across technological domains. While women-invented patents tend to receive fewer citations overall, they often exhibit unique strengths in specific fields, such as higher disruptiveness in biotechnology, greater originality and broader impact in civil engineering, and stronger engagement with public and academic resources in green technology. These domain-specific patterns underscore the importance of examining gender disparities beyond aggregate metrics, as women’s contributions to innovation may manifest differently depending on the technological and institutional context.

Discussion