Abstract

In the pursuit of global sustainability, renewable energy innovation (REI) plays a pivotal role in mitigating climate change and reducing reliance on fossil fuels. However, the development of renewable energy technologies is fraught with significant challenges, such as high upfront capital costs and technical uncertainties. Intellectual Property Protection (IPP) emerges as a crucial mechanism in this context, promoting knowledge diffusion and incentivising innovation. This study investigates the nonlinear relationship between IPP and REI across 27 countries, which together account for over 90% of global REI, while also considering heterogeneity in resource rents and political stability. In addition, it explores the moderating role of urbanisation in this nonlinear nexus and investigates the threshold effect of financial development (FD). To achieve these objectives, this study employs a fixed effects model and a threshold effects model. Outcomes confirm the existence of an inverted U-shaped relationship. The heterogeneity analysis reveals that this nonlinear effect is present only in groups with above-average resource rent and political stability. Urbanisation strengthens the inverted U-shaped relationship, while FD serves as a threshold variable, with higher FD weakening the negative effects of IPP. Lastly, specific policy recommendations are proposed to enhance renewable energy innovation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to IEA (2021), an increasing number of nations are committing to achieve net-zero emissions in the coming decades; however, fully realising these commitments remains a challenge, particularly in reaching the 2050 net-zero target. Although attaining this target is still a long way off, renewable energy has made significant strides. For example, the capacity of renewable electricity hit historic highs in 2022 (Renewables - Energy System, 2023). A number of policies, such as China’s 14th Five-Year Plan and the United States’ Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), are being implemented to encourage the growth of renewable energy (Renewables - Energy System, 2023).

Since most renewable energy resources are heavily affected by climatic variability, certain projects carry substantial risks. Furthermore, green projects require substantial upfront capital and face considerable uncertainty (Lee & Zhong, 2015; Pfeiffer & Mulder, 2013). As argued in Lee & Zhong (2015), reaching the breakeven point often requires a considerable time horizon, limiting renewable energy from being widely adopted. However, advances in green energy can improve the output of renewable energy, providing opportunities to raise demand while lowering expenses and risks (Luo et al., 2023). As a result, prioritising renewable energy innovation has become a key focus for governments and researchers worldwide.

Intellectual property rights protection (IPP) can influence innovation. As a comprehensive legal framework, IPP safeguards knowledge against duplication and encourages knowledge creation (Papageorgiadis & Sofka, 2020). By allowing innovators to benefit from the commercial rewards of their inventions, strengthening IPP motivates local businesses to increase research and development (R&D) investment. However, overly stringent IPP can hinder further innovation by stifling competition and fostering complacency (Hou et al., 2023).

Innovation is a vital component of achieving sustainable development (Innovation Needs in the Sustainable Development Scenario – Clean Energy Innovation – Analysis, 2020). While there are significant upfront capital expenses and technical obstacles associated with renewable energy, these problems can be lessened with the advancement of technology. IPP promotes the spread of knowledge and offers a supportive platform for technological innovation. However, recent research has primarily focused on the linear impact of IPP (Hudson & Minea, 2013; Lerner, 2009) or its effect on overall innovation (Allred & Park, 2007; Chen & Puttitanun, 2005; Gangopadhyay & Mondal, 2012), leaving the nonlinear effects of IPP specifically on renewable energy innovation (REI) and its underlying mechanisms underexplored. Understanding the role of IPP in influencing REI is therefore crucial for evaluating its effectiveness in fostering technological progress, promoting green transitions, and advancing long-term sustainability.

Considering the above motivation, this study collected a balanced panel dataset of 27 countries between 1998 and 2017, based on data availability, and conducted the analysis using a fixed effects model. The nonlinear effect of IPP on REI was analysed by introducing the squared term of IPP. Then, heterogeneity analysis was carried out and the sample was categorised according to the median values of political stability and resource rent. Moreover, a moderating effect model was used to examine the mechanism behind the nonlinear effect. Finally, a threshold effect model was introduced to analyse the threshold effect of financial development (FD). The results reveal an inverted U-shaped relationship between IPP and REI, which persists in country groups characterised by above-average resource rents and political stability. Moreover, urbanisation is found to amplify this curvilinear relationship, while FD serves as a threshold factor in shaping the relationship between IPP and REI.

The proportion of REI from the sample countries relative to global REI exceeded 90% across all observation years according to the OECD statistical database (OECD, 2024), demonstrating the representativeness of the sample in terms of REI. Additionally, the development trends of REI in the top five and bottom five countries as ranked in 2017 are presented in Figs. 1 and 2. As shown, Korea, the United States, Germany, and China consistently ranked high across almost all observation years. Notably, 2011 marked a significant turning point, as REI began to decline, eventually exhibiting an overall downward trend. One possible explanation for this could be the persistently falling global crude oil prices, which peaked at over $100 per barrel between 2011 and 2013 before steadily declining with occasional spikes (Bp, Statistical, 2020). The induced-innovation effect (Herman & Xiang, 2019) indicates that the decline in fuel energy prices could have made renewable energy R&D less attractive, thereby reducing REI.

In comparison with previous research, this study presents several novelties. First, in terms of study content, previous studies on the relationship between IPP and innovation have mostly relied on a database developed by Park & Ginarte (1997), which offers quinquennial data from 1975 to 2000. However, the most recent database, published by Papageorgiadis et al. (2014) and Papageorgiadis & Sofka (2020), spanning the 20 years from 1998 to 2017, has not been widely used by academics. Furthermore, no prior research has generally had examined the effect of IPP on REI. In order to fill this knowledge gap, this work adds to the corpus of research on renewable energy by empirically examining the influence of IPP on REI. Second, although nonlinear effects have been documented in the contexts of IPP and innovation (Hudson & Minea, 2013), scientific output (Jia et al., 2025), entrepreneurship (Hou et al., 2023), and emissions (Cheng et al., 2024), the nonlinear nexus between IPP and REI remains unexplored. This study extends the existing literature by examining whether IPP exerts an inverted U-shaped effect on REI. Third, a quadratic moderating effect model was employed to explore the transformation mechanism of the inverted U-shaped effects of IPP in relation to urbanisation. This provides insights into optimising the role of IPP and understanding how IPP impacts REI, leading to favourable external situations. Lastly, the threshold effect of FD is examined in this study.

The subsequent sections are structured as follows: the literature review summarises relevant studies; the methods and data section describes the research design and data sources; the empirical results section presents and discusses the findings; and finally, the conclusion provides a summary along with recommendations.

Literature review

Theoretical background

IPP refers to the laws and regulations created to protect creators’ rights. IPP, which grants exclusive rights, guarantees that authors or owners may manage how their works are used, distributed, and marketed. This promotes innovation and creativity while guarding against infringement or unapproved usage. According to Papageorgiadis & Sofka (2020), IPP primarily involves imitation costs, such as servicing costs, property rights costs, and monitoring transaction costs. IPP fosters innovation by granting the opportunity to financially benefit from holding a monopoly position in commercialisation (Raiser et al., 2017; World Trade Organisation (WTO), 2014). Besides that, patent holders are often compelled to share their knowledge rather than keep it confidential, which further promotes innovation (Allred & Park, 2007). Therefore, information spillovers ought to encourage innovation.

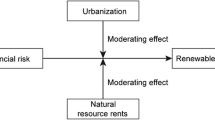

Two theoretical strands attempt to explain the depressed effect of IPP: one takes scale effects into account, while the other does not. Regarding the former, Furukawa (2007) explained the nexus with the scale effect, suggesting that higher levels of IPP contribute to monopolistic pricing, which in turn reduces industrial scale and accumulated experience. A decreased scale lessens the demand for goods, which decreases the motivation to innovate. In short, high IPP lowers the productivity of the final sector, reduces innovation, and hampers economic growth. In terms of the latter, Furukawa (2010) investigated the link between IPP and innovation by developing an endogenous growth model without scale effects. Strengthening IPP was found to reduce the production of non-monopolistic goods, leading to fewer opportunities for learning by doing. As a result, this hinders the accumulation of human capital. Figure 3 summarises the theoretical framework.

The IPP-REI nexus

While outlining the theoretical background may be straightforward, empirical research is needed to determine the impact of IPP on REI. Existing scholars have focused on the impact of IPP on innovation but have not specifically examined its effects on REI. Moreover, there was no consensus regarding the impact of IPP on innovation due to differences in samples and econometric methods.

Some scholars have argued that IPP increases innovation. For example, Sweet & Maggio (2015) proposed that the Economic Complexity Index (ECI) reflects the potential for innovation in relation to economic growth and the efficient manufacture and export of novel goods. As such, this index captures innovations embedded in the expansion of the product frontier. They concluded that IPP increased ECI, and this was significant only in developed countries when conducting subsample analysis. Using annual patent grant volume as a proxy for IPP, Xu et al. (2022) concluded that IPP enhanced the impact of subsidies on firms’ ability to innovate in China. Legal protection was found to encourage firms to develop and invest in new areas without expecting immediate returns.

Using a quasi-natural experiment, Gao & Zhao (2023) examined how IPP policy affected Chinese firm-level creativity and discovered that IPP fostered innovation. This was achieved by lessening funding restrictions and lowering R&D spillover losses. Similarly, Qayyum et al. (2022) employed provincial data from China to explore the nexus between IPP and innovation. IPP was measured by the ratio of property rights transactions to GDP, while innovation was represented by invention patent grants. The study found that a one-unit increase in IPP led to a 3.83% rise in innovation. This occurred because higher IPP enabled regional businesses to benefit from the commercial rents of innovation, thereby prompting them to drive up R&D spending. A similar positive effect of IPP on innovation was also observed in sub-Saharan Africa (Amankwah-Amoah & Medase, 2024), Saudi Arabia (Sarabdeen & Ishak, 2024), China (Cao et al., 2023) and Yangtze River Delta Region (Gao et al., 2020).

Conversely, past studies have also documented a negative relationship. Lerner (2009) analysed the IPP-innovation nexus using data from the top 60 GDP-ranked countries and found that stronger IPP actually reduced innovation, as represented by patent applications from residents. Strengthening IPP also did not lead to an increase in innovation. The researchers attributed this to the use of patent applications by residents as an inaccurate proxy for innovation, as well as the limited time frame of the study.

A U-shaped link has also been frequently reported in extant studies. Hudson & Minea (2013) investigated the connection between IPP and innovation and concluded that IPPs that were more stringent had a negative impact on innovation. The connection took a U shape when the squared term of IPP was introduced. Stricter IPPs had the main effect of hindering innovation. Furthermore, the U-shaped relationship may be influenced by GDP per capita. Allred & Park (2007) discovered a U-shaped relationship between IPP and innovation, proxied by domestic patenting. This occurred because, under weak IPP, imitation was restricted, while under strong IPP, appropriability was enhanced, encouraging knowledge disclosure and further innovation. Chen & Puttitanun (2005) employed the database developed by Park & Ginarte (1997) as the proxy of IPP and examined the nexus between economic growth, IPP, and innovation for 64 developing countries. They came to the conclusion that when the economy expanded, the IPP level first declined but then rose upon reaching a tipping point. Moreover, IPP refuted the prevailing wisdom by fostering indigenous innovation in developing nations. Jia et al. (2025) discovered an inverted U-shaped nexus between IPP and scientific output. While excessive IPP may monopolise resources and limit knowledge exchange, which would impede scientific advancement, moderate IPP can encourage more scientific engagement. Hou et al. (2023) argued for a U shape between IPP and entrepreneurship: IPP can encourage entrepreneurship in its early stages, but as it gets stricter, the cost of gaining expertise will unavoidably rise. As a result, there are fewer chances to generate new information, limiting the diffusion of existing knowledge and ultimately curbing entrepreneurial potential. Cheng et al. (2024) observed an inverted U-shaped nexus between IPP and emissions. Initially, IPP promotes investment in manufacturing processes and technologies characterised by high emissions. However, as IPP strengthens and environmental awareness increases, it increasingly supports the development and dissemination of low-carbon products and technologies.

In more advanced economies, the effects of IPP appear to be more pronounced. Apart from promoting innovation, IPP is essential to the establishment of a functional market system. Papageorgiadis & Sharma (2016) combined IPR regulation strength (Park & Ginarte, 1997) and enforcement (Papageorgiadis et al., 2014) to provide a more comprehensive impact of IPP. They contended that there was a U-shaped link between innovation and IPP, with more patents produced in response to stronger IPP. Gangopadhyay & Mondal (2012) introduced an economic theoretical model and ultimately analysed the results, demonstrating the existence of an inverted U-shaped relationship between IPP and innovation. On one hand, stronger IPP was found to increase the anticipated benefits from developments; on the other hand, it reduced knowledge spillover, thereby constraining innovation.

The Urbanisation-REI nexus

The influence of institutional contexts has produced a range of results in extant literature due to variations in study periods, sampling countries, and proxies for innovation. For instance, Bertinelli & Black (2004) introduced the urban economics framework and emphasised the importance of urbanisation for development. Population movement to urban regions entailed the accumulation of human capital, thereby driving technological advancements in the process. Wang et al. (2024) examined the impact of urbanisation on REI in 60 countries and concluded that urbanisation was beneficial for REI. As urbanisation rose, human capital and economic growth congregated, further stimulating the development of new technology. Chen et al. (2020) argued that urbanisation spurred regional innovation in Chinese provinces.

Urbanisation can facilitate the convergence of key production factors, such as venture capital, creative talent, and skilled labour, leading to a technological spillover effect for green innovation. The growth of urbanisation facilitates knowledge diffusion, reducing barriers to communication and education and encouraging the emergence of novel practices (Rosenthal & Strange, 2004). Based on the Chinese sixth national census, Lyu et al. (2019) showed that urbanisation aided in the knowledge economy’s growth. Urbanisation, which is characterised by the movement of talent and cultural variety, has greatly aided in the advancement of city innovation. In particular, cultural diversity can enhance creativity by attracting and concentrating human resources within cities. A similar positive sign between urbanisation and REI was also documented in 87 economies by Zheng et al. (2021). However, Li & Shao (2021) reported a negative nexus between urbanisation and REI in a subcategory analysis for OECD countries.

Literature on FD and REI

Innovation in renewable energy, in contrast to conventional fuels, has been found to face significant financial limitations (Wen et al., 2022). Levine et al. (2017) examined the impact of FD on innovation across 94 economies and concluded that FD increased innovation. By removing credit barriers that prevent capital from flowing to more profitable projects, FD can encourage R&D financing while also facilitating innovation activities (Hsu et al., 2014). However, some studies have reported a negative impact. Zhu et al. (2020) examined the impact of FD on innovation based on 50 countries and concluded that FD impeded innovation. Excessive financial operations have the potential to divert resources towards the financial sector rather than productive activities, thereby inhibiting innovation (Tobin, 1984). Besides that, higher financial activities lure employees—particularly skilled workers—into low-productivity sectors offering high salaries (Boustanifar et al., 2018), which in turn slows down innovation.

Literature gap

Although scholars have made substantial progress in examining IPP and REI, several gaps remain. First, while previous research has examined how IPP affects innovation, little attention has been given to its specific impact on REI, especially when proxied by patent applications in renewable energy technologies. This omission is important, as REI plays a central role in promoting green technological progress and advancing sustainable development. Moreover, existing studies have predominantly assumed a linear relationship, overlooking the possibility that IPP may exert nonlinear influences on REI. Second, the moderating role of urbanisation in the nonlinear relationship between IPP and REI remains under-researched. Lastly, little discussion has addressed the threshold effect of FD in shaping the influence of IPP on REI.

Therefore, the following hypotheses were proposed:

Hypothesis 1: There exists an inverted U-shape link between IPP and REI.

Hypothesis 2: Urbanisation can steepen the inverted U-shape link between IPP and REI.

Hypothesis 3: FD acts as a threshold variable in the nexus between IPP and REI.

Methods and data

The empirical model

To find out the impact of IPP on REI, this study adopted Model (1) to explore the nexus between IPP and REI by referring to Chen et al. (2022) and Lee & Ho (2022). If the parameter of α1 is positive, it can be inferred that a positive link exists between the explanatory and explained variables, and vice versa.

where REI is the explained variable, capturing the degree of REI. IPP is the explanatory variable, reflecting the level of intellectual property protection. CC is a set of control variables including FDI, Fiscal, and Trade. i, t is country and years, respectively. Vi refers to the fixed effects, and εi,t denotes the error term. As per Lee et al. (2024a, 2024b), this model incorporates only individual fixed effects. Furthermore, year dummies can sometimes exacerbate multicollinearity and undermine the reliability of coefficient estimates, according to Lee et al. (2024a).

By incorporating the squared term of IPP, Model (2) was established. If the parameter of α2 was positive and statistically significant, this would indicate a U-shaped link. Conversely, if α2 was negative and significant, it would suggest an inverted U-shaped link. If the computed parameter α2 was significantly positive, then hypothesis 1 would be validated. Model (2) is presented below.

where IPP2 is the squared term of IPP while other variables are in line with model (1).

Data

The empirical sample consisted of 27 countries ranging from 1998 to 2017, constrained by data availability. The REI data was constructed from the OECD statistical database (OECD, 2024) while IPP data was sourced from (Papageorgiadis et al. (2014) and Papageorgiadis & Sofka (2020). Control variables were obtained from the World Development Indicators (WDI). Merging these datasets and ensuring a balanced panel dataset resulted in a database comprising 27 countries over 20 years, yielding 540 observations.

Explained variable

Innovation is often measured by R&D expenditures, the number of patents (Chen & Puttitanun, 2005), publication-based indicators. Publications capture research activities; however, their linkage to real-world applications is often insufficient (Zhang et al., 2025). Besides, cross-country differences in financing efficiency may substantially influence the extent to which R&D spending translates into innovation (Zhang et al., 2025). Moreover, most developing countries do not have data on R&D expenditures, patents can be used as a cross-national proxy for innovation (Chen & Puttitanun, 2005). While patents do not capture all types of innovation and not all patent signify a true technological breakthrough, they nonetheless provide publicly available information about new technologies, methods, or products. This information is valuable for tracking technological development trends and assessing the scope and depth of innovation. Moreover, patent applications are preferred as a proxy for REI over awarded patents, since the granting process of the latter is often lengthy and differs across countries (Bhuiyan et al., 2025). For REI, this study employed the number of patent applications related to renewable energy, following the approach of Wang et al. (2024). The data was sourced from the OECD statistical database (OECD, 2024), and log(1 + data) was used as the REI measure.

The development of the number of patent applications for renewable energy for the years 1998 and 2017 is depicted in Figs. 4 and 5. A larger number of patents indicates higher REI; the lowest range was 0–10, and the highest was 400–900. There had been a notable improvement in REI from 1998 and 2017, as evident from the comparison between Figs. 4 and 5.

Explanatory variable

The explanatory variable was the strength of IPP, which referred to imitation costs. Taking into account the reliability and credibility of the data, this study employed the IPR index released by (Papageorgiadis et al. (2014) and Papageorgiadis & Sofka (2020) and referring to Viglioni et al. (2024). Incorporating new proxies from diverse information sources, this index encompassed a wide range of property rights protection costs, or “transaction costs”, arising from the patent system of a specific nation. This index ranged from 0 to 10, with higher values indicating greater imitation costs, such as servicing costs, property rights costs, and monitoring transaction costs (Papageorgiadis & Sofka, 2020).

Control variable

In accordance with previous literature, this study controlled for a certain set of country-level factors.

-

(1)

FDI was proxied by FDI net inflows as a percentage of GDP. FDI could impose a significant impact on REI. FDI accelerates the transition to sustainable technologies and makes innovation activities more environmentally-friendly through technology transfer and knowledge sharing (Luo et al., 2021; Raihan et al., 2025a; Riaz et al., 2025; Yin et al., 2022). Besides that, FDI has been documented to aid in the promotion of innovation in geothermal energy (Li & Shao, 2021).

-

(2)

Fiscal was denoted by general government consumption expenditure as a share of GDP. According to the externality theory, government funding is expected to encourage private businesses to increase their innovation activities (Li et al., 2021).

-

(3)

Trade was proxied by the ratio of trade activities to GDP. Trade liberalisation makes it easier for components to move across international boundaries, thereby reducing costs for renewable energy projects (Hussain et al., 2021; Mandelman & Waddle, 2020). Besides that, the movement of goods across borders promotes the acquisition of green technologies and the flow of green raw materials—all of which help bring forth new green inventions (Zhang et al., 2022).

The variable descriptions and descriptive statistics are displayed in Table 1. The mean value of REI was 3.518, while IPP had a mean value of 7.065. The IPP maximum and minimum values were 2.6 and 9.7, respectively, indicating considerable variation in the level of IPP across countries.

Empirical results

Pre-benchmark tests

Table 2 displays the correlation diagnostics results. The table indicates that IPP and REI may have a positive association. The maximal VIF value of 1.44, together with the low correlation coefficients, indicates a minimal risk of multicollinearity. Furthermore, as the results of the slope heterogeneity (SH) test included in Table 3 were significant at the 1% level, they corroborated the existence of heterogeneity. Additionally, in order to examine the existence of cross-sectional dependence (CD), this study adopted the Pesaran CD, Pesaran scaled LM, and Breusch-Pagan LM tests (Breusch & Pagan, 1980; Pesaran, 2004, 2004). The significant outcomes presented in Table 4 suggest that there was CD among the variables. The stationarity of variables was tested using the unit root test developed by Pesaran (2007). REI, IPP, and FDI were found to be stationary at the level, while Fiscal and Trade became stationary at the first difference, as indicated by the significance levels presented in Table 5.

Baseline model

In this section, Model (2) was empirically tested to analyse the impact of IPP on REI. Table 6 displays the baseline model results in columns (1) through (3), where control variables were progressively added. The indications of IPP and IPP2, with IPP being positive and IPP2 being negative, remained significant when comparing the model without control variables to the one including all controls. Column (3) of Table 6 represents the final outcomes.

It can be observed that the parameters for IPP and IPP2 were 0.927 and −0.099, respectively, both significant at the 1% level. Therefore, hypothesis 1 was validated. The inverted U-shaped association between IPP and REI was provisionally validated by this parameter. Before reaching the inflection point, IPP was beneficial to the REI; once past it, the opposite was true. Figure 6 shows an inverted U-shaped fitting curve to further support this link. The nonlinear fitted curves were shown to be more effective in explaining the relationship between IPP and REI. In line with (Lee & Yan, 2024), this study conducted a U-shaped test and the outcomes are presented in Table 7.

According to the results, the upper bound and lower bound slopes were −0.988 and 0.413, both significant at the 1% level. Additionally, the overall test, significant at 1%, confirmed the existence of curvilinear relationship. The turning point of 4.693 fell within the observed range of IPP, allowing for the observation of a complete inverted U-shaped curve. In addition, Table 8 presents the time points when countries crossed the turning point.

The results showed a curvilinear link between IPP and REI, suggesting that the protection level would affect how IPP impacts innovation. Specifically, a low level of IPP was found to positively impact REI, while a higher level of IPP had a negative influence. Before the tipping point, IPP promoted REI by providing companies with a secure environment to protect their ideas and recover R&D investments.

As discussed in Section 2.1, IPP holders benefit financially from monopolising commercialisation efforts (Raiser et al., 2017; World Trade Organisation (WTO), 2014). This incentivises innovators to invest in renewable technologies without fear of imitation. However, once IPP is strengthened beyond the tipping point, its positive effects would diminish. Excessive IP protection may slow innovation, restricting the diffusion of new technologies, curbing the commercialisation of inventions, and stifling competition (Hou et al., 2023), as firms become less motivated to innovate after securing a dominant market position. Furthermore, strong IPP can deter new entrants, particularly smaller firms, due to the high costs of acquiring or licensing patents (Acs & Sanders, 2012; Reed et al., 2012). In industries like renewable energy, where firms often work on similar technologies, elevated IP barriers can stifle the exploration of new ideas. This inverted U-shaped relationship aligns with the findings of Jia et al. (2025), who identified such a nexus between IPP and scientific output, and Cheng et al. (2024), who reported a similar relationship between IPP and emissions.

Trade was positively connected with REI. By supplying low-pollution intermediaries and enabling the dissemination of cutting-edge technology, international trade can promote the development of novel renewable energy sources (Wang et al., 2021). Greater trade openness can promote domestic REI if the local economy is capable of absorbing the possible benefits of commerce (Canh et al., 2019). A similar positive sign was documented in Qayyum et al. (2022) for China.

Fiscal was found to increase REI in the sample countries. According to Carley et al. (2017), Rasheed et al. (2025) and Shen & Luo (2015), grants from governments stimulate renewable energy projects by lowering upfront expenditures. Tax incentives lower the cost of financing, thereby boosting equity investors’ profits (Shen & Luo, 2015) and increasing investors’ interest in green projects. Hassett & Metcalf (1995) further showed that the likelihood of investing in the renewable sector might rise by 24% with a 10% increase in tax policy. The positive nexus between Fiscal and REI is consistent with the findings of Marques & Fuinhas (2012) for European countries and Bird et al. (2005) for United States.

FDI was found to be negatively correlated with REI, though the relationship was insignificant, indicating that FDI did not contribute to an increase in REI. This outcome is consistent with research conducted by Zhang et al. (2022) for China. This could be explained by the pollution haven effect; when multinational corporations invest across borders to evade costly environmental legislation and abatement measures in their own countries, this prevents the spread of green knowledge (Ahmed et al., 2025; Fu et al., 2020; Rasheed et al., 2024; Shen et al., 2020).

Robust test

Omit control variable

Good governance was found to be beneficial for REI. Benavides-Franco et al. (2023) concluded that good governance fosters renewable energy in Project Finance. They clarified that securing abundant financing requires a high degree of transparency regarding the project’s specific characteristics, while good governance is essential for gaining investors’ trust. Islam et al. (2022) and Wang et al. (2024) argued that bad governance damages ecological sustainability and suppresses REI. Bad governance shifts resources to address violent episodes. Therefore, this study constructed an IQ index by averaging five indicators from ICRG: (1) law and order, (2) corruption control, (3) democratic accountability, (4) bureaucratic quality, and (5) government stability, following Luo & Sun (2024). This new control variable was included in the model, and the results are reported in column (1) of Table 9. The parameter of IPP and IPP2 were positive and negative, further validating Hypothesis 1.

Other estimate technique

The Dynamic Common Correlated Effects Model (DCCE) proposed by Ditzen (2019) can address issues related to cross-sectional dependence and slope heterogeneity, as noted by Hondroyiannis et al. (2022). Taking into account the possible heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation problems, this study adopted feasible generalised least squares (FGLS) for the robustness test, in line with the research conducted by Liu et al. (2023). In line with Aslan et al. (2024) and Voumik et al. (2024), this study also adopted Driscoll and Kraay’s (DK) standard errors (Driscoll & Kraay, 1998) technique. Data with cross-sectional “spatial” and temporal dependence may yield more robust outcomes with DK standard errors. The outcomes reported in columns (2)– (4) of Table 9 indicated that the parameter of IPP was significantly positive, while that of IPP2 was significantly negative. Therefore, the basic outcomes were robust.

Exclude outlier

According to Oyekola et al. (2024), the influence of outlier samples may have an impact on the robustness of the outcomes. The OECD statistical database (OECD, 2024) provides data on renewable related patent applications, where China and the US recently scored highly. Data from EIA (2022) also showed that energy production from renewable sources in the U.S. and China amounted to 16.368 and 14.734 quadrillion Btu, respectively, while France, in third place, produced 3.417 quadrillion Btu. This highlights the crucial role that the U.S. and China play in renewable energy production. This section excluded these two countries to check the existence of an inverted U-shaped relationship in the remaining sample. The outcomes reported in columns (5) of Table 9 show a positive coefficient for IPP and a negative coefficient for IPP2, confirming the existence of an inverted U-shaped link.

Heterogeneity test

Natural resource endowments, extraction costs, market accessibility, economic structures, and government stability vary significantly across countries. These differences result in varying levels of natural resource rents and governance quality, which make these issues important to take into account. This study further conducted a heterogeneity analysis to examine regional differences in the IPP-REI link. Based on whether the sample was above or below the median, the samples were divided into groups of high and low natural resource rents, as well as high and low government stability.

The heterogeneity test results for natural resources are presented in columns (1) and (2) of Table 10. The results show that the coefficients for IPP2 and IPP were −0.163 and 1.788, respectively, significant at the 1% level, within high-natural resource rent regions. Nevertheless, these factors were not statistically significant in low-natural resource rent groups. The results of this test indicate that the curvilinear relationship in the IPP-REI holds only in high-nature resource contexts. A possible explanation is that an abundance of natural resources could function as a “blessing”, facilitating the establishment and development of the local economy (Nawaz et al., 2019). High-natural resource rent groups typically experience higher levels of economic growth and FD. Significant financial resources generated from natural resource rents could be directed toward a variety of industries, including the finance sector. Nations with substantial resource rents have the opportunity to establish sovereign wealth funds and accumulate large amounts of capital (Okolo et al., 2024). Moreover, an abundance of resources generates foreign exchange earnings and increases exports, which in turn stimulates economic growth (Okolo et al., 2024). In contrast, low-natural resource rent groups lack these advantages, which results in an insignificant impact.

The heterogeneity test outcomes for government stability are presented in columns (3) and (4) of Table 10. Similar to the previous heterogeneity test, the curvilinear relationship was found to exist only for high-government stability groups. According to the institution-based concept, innovation activities cannot occur without sound governance (He & Tian, 2020). As argued by Crain & Crain (2006), elements contributing to instability, such terrorist attacks, are negative to economic activities because they create psychological capital loss and discourage foreign investment. The uncertainty associated with an unstable environment hinders green innovation technologies advancement (Zheng et al., 2021) and delays investment (Julio & Yook, 2012), especially in capital-intensive sectors like renewable energy.

Mechanism test

Moderating effect

The direct effects of IPP on the REI were examined in the previous model to analyse the moderating role of urbanisation. Following this, this study introduced Model (3) as below.

where the meanings of the other variables remained the same as previously mentioned. Here, Urban was the moderator variable, representing the level of urbanisation. This moderating analysis primarily focused on the curvature of the U-shaped relationship, the presence of any reversal, and the shifting of the turning point within a quadratic term moderation model. According to Haans et al. (2016), the sign of α4 determines whether the initial U-shaped relationship is steepened or flattened. A negative sign would steepen the inverted U-shaped relationship, while a positive sign would flatten it or result in an inverted slope. The shift of the knee point is determined by the value of α1α4-α2α3. If the value is positive, the knee point would move to the right; otherwise, it would move to the left (Du & Lin, 2022; Lee & Yan, 2024; Liu et al., 2024).

The outcomes presented in column (5) of Table 10 show that the parameter of α4 was significantly negative at the 1% level and α1α4-α2α3 was not significant. The conclusion that could be drawn is that the moderator steepened the curve. Therefore, hypothesis 2 was validated. Figure 7 further illustrates that, as the value of Urban increased, the inverted U-shaped relationship between IPP and REI steepened and a higher level of REI could be observed with higher Urban.

Urbanisation plays a critical role in fostering technological advancements and innovation through the concentration of labour, knowledge, industries and resources. On the one hand, urbanisation that results from rural labourers moving to cities leads to advancements in technology and increases in productivity (Brunt & García-Peñalosa, 2022). Kwilinski et al. (2023) also contended that urbanisation promotes the spread of cutting-edge technology and knowledge, closing inequalities in living standards and lowering the cost of services. The city’s growth and spatial concentration create lively atmosphere that has gotten better when it comes to interpersonal relationships. People communicate more, and cities become hubs of information. In addition, urbanisation generates knowledge externalities, further promoting innovation (Raihan et al., 2025b; Tappeiner et al., 2008). On the other hand, urbanisation growth encourages the spatial clustering of industries, resulting in the externalisation of technology and increasing innovation (Fujita et al., 1999). Urban places are more efficient at converting creative ideas into workable solutions because they have access to trained labour and cash. In urban settings, moderate levels of IP protection might already produce higher REI compared to less urbanised areas because of the richer innovation ecosystem. The research conducted by Lin & Zhu (2021) and Wang et al. (2021) also supports the positive impact of urbanisation on innovation. Cities with higher industrial concentrations may experience increased company competition (Glaeser et al., 1992), particularly in knowledge-intensive sectors where access to intellectual property is crucial. However, under stringent IPP, this heightened competition does not necessarily foster innovation. Instead, smaller or latecomer firms may be compelled to divert substantial resources to licensing, legal disputes, or defensive patenting strategies, thereby crowding out productive R&D investments. Furthermore, the market dominance of leading companies with sizable patent portfolios tends to be reinforced by the concentration of firms in urban areas. This strengthens monopolistic power, enabling established firms to impose higher technology costs and limit the spread of information.

Threshold effect

One of the most important factors influencing how IPP influences innovation in renewable energy is a healthy financial market. The rise in IPP levels stimulates the demand for a well-developed financial market. For instance, FD facilitates innovation financing and reduces entry barriers related to IP protection. The challenges to REI—such as capital requirements, lengthy R&D cycles, and enhanced hazards—make it increasingly difficult to obtain financing for innovation operations (Allred & Park, 2007; Luan & Lin, 2022). Where FD is high, firms find it easier to access the financing needed for innovation, particularly for expensive and high-risk renewable energy initiatives. Innovation can overcome possible barriers created by IPP when they have access to a wide range of funding options, including loans, green bonds, and venture capital, thanks to a robust financial system.

This study referred to the threshold model proposed by Hansen (1999) to test the threshold effect of FD. FD was proxied by the Financial Development Index from IMF (2024), which captures the depth, access, and efficiency of both financial institutions and financial markets. To check for the presence of single, double, and triple thresholds, a threshold effect test was conducted using Stata. The outcomes reported in Table 11 reveal that the single and double thresholds were significant, while the third threshold was not. Therefore, the impact of IPP on RNI had a double threshold effect.

Additionally, threshold values estimated in Table 12 indicated that the corresponding threshold values were 0.427 and 0.7705. Furthermore, in accordance with the threshold effect’s criteria, the threshold value was represented by the matching γ value as the LR value got closer to zero (Liu et al., 2024). The LR diagram depicted in Fig. 8 further confirmed these two threshold values.

Therefore, the threshold Model (4) below was established.

where I (⋅) was the index function. γ was the various threshold value. These two threshold values divided the range into three intervals. By examining the threshold effect, the parameter of IPP could be determined within each interval. According to the outcomes presented in Table 13, when FD exceeded 0.7705, the parameter of IPP was −0.352, which was significant at the 5% level. When FD lay between 0.427 and 0.7705, the coefficient was −0.463, significant at the 1% level. For FD values below 0.427, the estimated coefficient was −0.804, also significantly negative at the 1% level. Therefore, hypothesis 3 was validated.

Based on the results, the lower the FD, the more significant the effect of IPP on REI. This phenomenon can be explained by the following. It is well-established that entry barriers are driven by the significant capital requirements and the ease of access to low-cost financing (Bain, 1956). Low financial development conditions make it difficult for businesses to obtain outside funding for innovation, and they mostly rely on IPP to guarantee returns on investment. The monopolistic effects of IPP become more pronounced in these situations, limiting other companies’ ability to enter the market and reducing industry-wide innovation. But as FD advances, innovators can use a variety of funding options to support research, even in the face of formidable intellectual property obstacles.

Besides that, small and medium-sized businesses’ (SMEs) ability to access the market is enhanced by FD, even in the face of robust IPP. SMEs can overcome obstacles like patent fees and legal expenditures when they have access to adequate finance through a well-developed financial system. This enables them to bypass IP-related barriers and join the market. Therefore, enterprises can use financial market assistance to engage in innovative activities even with strong IPP, lessening the inhibitory effect of IPP on innovation.

Conclusion and Policy recommendations

Conclusion

REI is essential for the transition to sustainable energy systems, reducing greenhouse gas emissions and mitigating the impacts of climate change. Its advancement is essential to maintaining long-term economic and environmental resilience, particularly in light of the world’s energy concerns. IPP serves as a stimulus for REI in the meantime. This study examines the link between IPP and REI using data from 27 distinct countries, and the empirical analysis yields the following findings.

First, there is an inverted U-shaped relationship between IPP and REI, where the direction of IPP’s influence on REI depends on the relative strength of its positive and negative effects. The commercialisation incentives and information diffusion that IPP promotes are the main causes of its beneficial effects. Conversely, the adverse impact stems from two factors. The first is the obstacles IPP places on late market entrants due to the high costs of obtaining or licensing patents. Secondly is the reduced incentive for innovation that arises from the monopolistic positions granted by IPP. The detrimental impacts of IPP outweigh its advantages after the inflection point is crossed. Second, this curvilinear relationship holds for countries with above-average level resource rents or government stability. Third, the curvilinear relationship between IPP and REI is steepened by urbanisation. Lastly, threshold effects imply that the adverse effect of IPP on REI is mitigated by more advanced financial markets.

Policy implications

First, governments should create a flexible IPP framework that includes differentiated mechanisms for renewable technologies. For example, rather than uniformly extending protection, governments could experiment with shorter patent durations combined with complementary mechanisms like patent pools, which allow firms to share critical technologies under standardised licensing agreements. Such mechanisms reduce duplication costs and speed diffusion. In parallel, formal incentives—such as tax credits or competitive grants—could be provided to firms and research institutions that adopt open-source innovation models or actively participate in informal knowledge-sharing networks. The IPP rules should then be periodically reviewed to ensure that protection is adequate to reward early innovators while avoiding excessive barriers to entry and knowledge dissemination.

Second, governments should implement renewable-energy–specific policy mechanisms that directly mitigate political and market risks. For instance, they could implement feed-in tariff schemes supported by legally binding long-term contracts, thereby guaranteeing price stability for renewable electricity producers. In resource-dependent economies, a portion of natural resource rents could be earmarked for competitive green innovation funds. These funds should be allocated through transparent calls for proposals, with evaluation criteria explicitly linked to carbon-reduction potential and technological scalability. Such targeted measures reduce investor uncertainty, improve the efficiency of rent allocation, and create concrete incentives for private actors to commit to long-term renewable energy projects. In economies with low resource rents, governments might instead employ innovation-friendly tax schemes or shorten patent durations for renewable technologies, rather than applying uniform protection, thereby lowering entry barriers, accelerating knowledge diffusion, and offsetting the limited resource-based incentives for renewable investment. In politically unstable contexts where IPP alone is insufficient to drive renewable innovation, reforms could be paired with mandatory knowledge-transfer requirements in foreign direct investment contracts. For example, companies benefiting from patent rights might be obliged to form joint ventures with local research institutions, embedding innovation outcomes more firmly in domestic capabilities and reducing susceptibility to instability.

Third, governments should enhance urban infrastructure, such as transportation and communication networks, to facilitate the effective flow of ideas and commerce. These improvements can foster innovation and collaboration among firms. Additionally, creating forums for companies, academics, and policymakers to collaborate and exchange knowledge in urban areas can help disseminate cutting-edge concepts and best practices for renewable energy.

Finally, governments might implement specific green finance mechanisms that specifically address the limitations brought about by strong IPP, rather than fostering the growth of financial markets generally. Examples include the establishment of renewable technology venture funds co-financed by public and private investors, or the issuance of green bonds earmarked for renewable energy start-ups. Financial institutions employing these instruments might also be granted specific tax incentives, such as lower capital requirements for banks financing patent-intensive renewable energy projects. By channelling financial resources to innovative firms that might otherwise face barriers to entry under stringent IPP regimes, such measures would enhance competition and stimulate innovation.

Future directions

There are still some limitations. First, this paper examines REI only at the country level, lacking micro-level analysis of firm-specific REI. Second, due to data availability, this study is restricted to 27 countries, most of which are developed nations. Third, the sample period ends in 2017, which prevents the analysis from capturing the potential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Future research could explore other proxies of IPP and REI, covering countries with diverse levels of economic and technological development and longer period to draw more generalisable conclusions. Moreover, the specific channels through which the inverted U-shaped effect of IPP on REI operates remain underexplored. Although estimation biases were mitigated using DKSE, FGLS, and DCCE models in the robust test, future studies could employ more robust techniques, such as machine learning algorithm approaches (Ali et al., 2025) and Lewbel technique, to further strengthen the outcomes.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Acs ZJ, Sanders M (2012) Patents, knowledge spillovers, and entrepreneurship. Small Bus Econ 39:801–817

Ahmed Z, Rasheed MQ, Pinzon S (2025) Analyzing the effects of wind energy and transportation on the ecological footprint: A pathway to sustainable development in leading economies. Environ Dev Sustain, 1–27

Ali MDI, Rahaman MDA, Ali MJ, Rahman MDF (2025) The growth–environment nexus amid geopolitical risks: Cointegration and machine learning algorithm approaches. Discov Sustain 6(1):78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43621-025-00872-z

Allred BB, Park WG (2007) Patent rights and innovative activity: Evidence from national and firm-level data. J Int Bus Stud 38:878–900. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400306

Amankwah-Amoah J, Medase SK (2024) Extracting innovation value from intellectual property: Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa. J Knowl Econ 15(2):8933–8967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-023-01225-9

Aslan A, Ilhan O, Usama A-M, Savranlar B, Polat MA, Metawa N, Raboshuk A (2024) Effect of economic policy uncertainty on CO2 with the discrimination of renewable and non renewable energy consumption. Energy 291:130382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2024.130382

Bain JS (1956) Barriers to new competition: Their character and consequences in manufacturing industries. Harvard University Press

Benavides-Franco J, Gómez JM, Pérez-Uribe MA (2023) Determinants of Project Finance success for renewable energy. Renew Energy 211:188–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2023.04.031

Bertinelli L, Black D (2004) Urbanization and growth. J Urban Econ 56(1):80–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2004.03.003

Bhuiyan MRU, Dutta A, Uddin GS, Ahmed A (2025) Readiness, riskiness and renewables: Country-level readiness and innovation in renewable energy under macroeconomic uncertainty. Sustain Futures 10:101158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sftr.2025.101158

Bird L, Bolinger M, Gagliano T, Wiser R, Brown M, Parsons B (2005) Policies and market factors driving wind power development in the United States. Energy Policy 33(11):1397–1407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2003.12.018

Boustanifar H, Grant E, Reshef A (2018) Wages and human capital in finance: International evidence, 1970–2011. Rev Financ 22(2):699–745. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfx011

Bp Statistical (2020) Review of World Energy 2020. Bp Global. https://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/energy-economics.html

Breusch TS, Pagan AR (1980) The Lagrange multiplier test and its applications to model specification in econometrics. Rev Econ Stud 47(1):239–253. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297111

Brunt L, García-Peñalosa C (2022) Urbanisation and the onset of modern economic growth. Econ J 132(642):512–545. https://doi.org/10.1093/ej/ueab050

Canh NP, Schinckus C, Thanh SD (2019) Do economic openness and institutional quality influence patents? Evidence from GMM systems estimates. Int Econ 157:134–169

Cao Y, Elahi E, Khalid Z, Li P, Sun P (2023) How do intellectual property rights affect green technological innovation? Empirical evidence from China. Sustainability 15(10):7762. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15107762

Carley S, Baldwin E, MacLean LM, Brass JN (2017) Global expansion of renewable energy generation: An analysis of policy instruments. Environ Resour Econ 68:397–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10640-016-0025-3

Chen J, Wang L, Li Y (2020) Natural resources, urbanization and regional innovation capabilities. Resour Policy 66:101643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2020.101643

Chen Y, Cheng L, Lee C-C (2022) How does the use of industrial robots affect the ecological footprint? International evidence. Ecol Econ 198:107483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2022.107483

Chen Y, Puttitanun T (2005) Intellectual property rights and innovation in developing countries. J Dev Econ 78(2):474–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2004.11.005

Cheng P, Wang Y, Wang M (2024) Does intellectual property rights protection help reduce carbon emissions? Hum Soc Sci Commun 11(1):1233. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03746-3

Crain NV, Crain WM (2006) Terrorized economies. Public Choice 128:317–349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-006-9056-6

Ditzen J (2019) Estimating long run effects in models with cross-sectional dependence using xtdcce2. Centre for Energy Economics Research and Policy (CEERP) Working Paper No, 7

Driscoll JC, Kraay AC (1998) Consistent covariance matrix estimation with spatially dependent panel data. Rev Econ Stat 80(4):549–560. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465398557825

Du L, Lin W (2022) Does the application of industrial robots overcome the Solow paradox? Evidence from China. Technol Soc 68:101932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.101932

EIA (2022) International—U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). https://www.eia.gov/international/data/world/total-energy/total-energy-production?pd=44&p=000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000100o&u=2&f=A&v=mapbubble&a=-&i=none&vo=value&t=C&g=00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000001&l=249-ruvvvvvfvtvnvv1vrvvvvfvvvvvvfvvvou20evvvvvvvvvvnvvvs0008&s=315532800000&e=1640995200000&

Fu Q, Chen YE, Jang C-L, Chang C-P (2020) The impact of international sanctions on environmental performance. Sci Total Environ 745:141007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141007

Fujita M, Krugman P, Mori T (1999) On the evolution of hierarchical urban systems. Eur Econ Rev 43(2):209–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0014-2921(98)00066-X

Furukawa Y (2007) The protection of intellectual property rights and endogenous growth: Is stronger always better? J Econ Dyn Control 31(11):3644–3670. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jedc.2007.01.011

Furukawa Y (2010) Intellectual property protection and innovation: An inverted-U relationship. Econ Lett 109(2):99–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2010.09.004

Gangopadhyay K, Mondal D (2012) Does stronger protection of intellectual property stimulate innovation? Econ Lett 116(1):80–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2012.01.006

Gao X, Cao M, Yang T, Basiri A (2020) Transport development, intellectual property rights protection and innovation: The case of the Yangtze River Delta Region, China. Res Transp Bus Manag 37:100563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rtbm.2020.100563

Gao X, Zhao Y (2023) Does intellectual property protection promote green innovation in firms? A perspective on R&D spillovers and financing constraints. Plos One 18(11):e0288315. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288315

Glaeser EL, Kallal HD, Scheinkman JA, Shleifer A (1992) Growth in cities. J Politi Econ 100(6):1126–1152. https://doi.org/10.1086/261856

Haans RF, Pieters C, He Z-L (2016) Thinking about U: Theorizing and testing U‐and inverted U‐shaped relationships in strategy research. Strateg Manag J 37(7):1177–1195. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2399

Hansen BE (1999) Threshold effects in non-dynamic panels: Estimation, testing, and inference. J Econ 93(2):345–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-4076(99)00025-1

Hassett KA, Metcalf GE (1995) Energy tax credits and residential conservation investment: Evidence from panel data. J Public Econ 57(2):201–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2727(94)01452-T

He J, Tian X (2020) Institutions and innovation. Annu Rev Financ Econ 12(1):377–398. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-financial-032820-083433

Herman KS, Xiang J (2019) Induced innovation in clean energy technologies from foreign environmental policy stringency? Technol Forecast Soc Change 147:198–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.07.006

Hondroyiannis G, Papapetrou E, Tsalaporta P (2022) New insights on the contribution of human capital to environmental degradation: Evidence from heterogeneous and cross-correlated countries. Energy Econ 116:106416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2022.106416

Hou B, Zhang Y, Hong J, Shi X, Yang Y (2023) New knowledge and regional entrepreneurship: The role of intellectual property protection in China. Knowl Manag Res Pract 21(3):471–485. https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2021.1997655

Hsu P-H, Tian X, Xu Y (2014) Financial development and innovation: Cross-country evidence. J Financ Econ 112(1):116–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2013.12.002

Hudson J, Minea A (2013) Innovation, intellectual property rights, and economic development: A unified empirical investigation. World Dev 46:66–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.01.023

Hussain J, Zhou K, Muhammad F, Khan D, Khan A, Ali N, Akhtar R (2021) Renewable energy investment and governance in countries along the belt & Road Initiative: Does trade openness matter? Renew Energy 180:1278–1289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2021.09.020

IEA (2021) Net Zero by 2050 – Analysis—IEA. https://www.iea.org/reports/net-zero-by-2050

IMF (2024) The Financial Development Index. https://data.imf.org/?sk=F8032E80-B36C-43B1-AC26-493C5B1CD33B

Innovation needs in the Sustainable Development Scenario – Clean Energy Innovation – Analysis (2020) IEA. https://www.iea.org/reports/clean-energy-innovation/innovation-needs-in-the-sustainable-development-scenario

Islam MDM, Ali MDI, Ceh B, Singh S, Khan MK, Dagar V (2022) Renewable and non-renewable energy consumption driven sustainable development in ASEAN countries: Do financial development and institutional quality matter? Environ Sci Pollut Res 29(23):34231–34247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-021-18488-x

Jia P, Xie W, Tian W, Wang X (2025) The impact of IP protection on scientific output: Evidence from the plant variety sector. Scientometrics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-025-05408-w

Julio B, Yook Y (2012) Political uncertainty and corporate investment cycles. J Financ 67(1):45–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2011.01707.x

Kwilinski A, Lyulyov O, Pimonenko T (2023) The effects of urbanisation on green growth within sustainable development goals. Land 12(2):511. https://doi.org/10.3390/land12020511

Lee CW, Zhong J (2015) Financing and risk management of renewable energy projects with a hybrid bond. Renew Energy 75:779–787. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2014.10.052

Lee C-C, Li J, Wang F (2024a) The role of green finance in the construction of new energy system: Evidence from China. Energy Econ, 107878. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2024.107878

Lee C-C, Fang Y, Quan S, Li X (2024b) Leveraging the power of artificial intelligence toward the energy transition: The key role of the digital economy. Energy Econ 135:107654. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2024.107654

Lee C-C, Ho S-J (2022) Impacts of export diversification on energy intensity, renewable energy, and waste energy in 121 countries: Do environmental regulations matter? Renew Energy 199:1510–1522. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2022.09.079

Lee C-C, Yan J (2024) Will artificial intelligence make energy cleaner? Evidence of nonlinearity. Appl Energy 363:123081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.123081

Lerner J (2009) The empirical impact of intellectual property rights on innovation: Puzzles and clues. Am Econ Rev 99(2):343–348. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.99.2.343

Levine R, Lin C, Wei L (2017) Insider trading and innovation. J Law Econ 60(4):749–800. https://doi.org/10.1086/696384

Li Q, Wang M, Xiangli L (2021) Do government subsidies promote new-energy firms’ innovation? Evidence from dynamic and threshold models. J Clean Prod 286:124992. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124992

Li S, Shao Q (2021) Exploring the determinants of renewable energy innovation considering the institutional factors: A negative binomial analysis. Technol Soc 67:101680. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101680

Lin B, Zhu J (2021) Impact of China’s new-type urbanization on energy intensity: A city-level analysis. Energy Econ 99:105292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105292

Liu B, Yang X, Zhang J (2024) Nonlinear effect of industrial robot applications on carbon emissions: Evidence from China. Environ Impact Assess Rev 104:107297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2023.107297

Liu Y, Dong K, Jiang Q (2023) Assessing energy vulnerability and its impact on carbon emissions: A global case. Energy Econ 119:106557. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2023.106557

Luan R, Lin B (2022) Positive or negative? Study on the impact of government subsidy on the business performance of China’s solar photovoltaic industry. Renew Energy 189:1145–1153

Luo H, Sun Y (2024) The impact of energy efficiency on ecological footprint in the presence of EKC: Evidence from G20 countries. Energy 304:132081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2024.132081

Luo S, Yimamu N, Li Y, Wu H, Irfan M, Hao Y (2023) Digitalization and sustainable development: How could digital economy development improve green innovation in China? Bus Strategy Environ 32(4):1847–1871. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3223

Luo Y, Salman M, Lu Z (2021) Heterogeneous impacts of environmental regulations and foreign direct investment on green innovation across different regions in China. Sci Total Environ 759:143744. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143744

Lyu L, Sun F, Huang R (2019) Innovation-based urbanization: Evidence from 270 cities at the prefecture level or above in China. J Geogr Sci 29:1283–1299

Mandelman FS, Waddle A (2020) Intellectual property, tariffs, and international trade dynamics. J Monet Econ 109:86–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmoneco.2019.10.013

Marques AC, Fuinhas JA (2012) Are public policies towards renewables successful? Evidence from European countries. Renew Energy 44:109–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2012.01.007

Nawaz K, Lahiani A, Roubaud D (2019) Natural resources as blessings and finance-growth nexus: A bootstrap ARDL approach in an emerging economy. Resour Policy 60:277–287. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resourpol.2019.01.007

OECD (2024) OECD Data Explorer • Patents—Technology development. https://data-explorer.oecd.org/

Okolo CV, Wen J, Susaeta A (2024) Maximizing natural resource rent economics: The role of human capital development, financial sector development, and open-trade economies in driving technological innovation. Environ Sci Pollut Res 31(3):4453–4477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-023-31373-z

Oyekola O, Emediegwu LE, Animashaun JO (2024) Commodity windfalls, political regimes, and environmental quality. Energy Econ, 107813. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2024.107813

Papageorgiadis N, Cross AR, Alexiou C (2014) International patent systems strength 1998–2011. J World Bus 49(4):586–597. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2013.12.011

Papageorgiadis N, Sharma A (2016) Intellectual property rights and innovation: A panel analysis. Econ Lett 141:70–72

Papageorgiadis N, Sofka W (2020) Patent enforcement across 51 countries–Patent enforcement index 1998–2017. J World Bus 55(4):101092. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2020.101092

Park WG, Ginarte JC (1997) Intellectual property rights and economic growth. Contemp Econ Policy 15(3):51–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7287.1997.tb00477.x

Pesaran MH (2004) General diagnostic tests for cross section dependence in panels. Available at SSRN 572504

Pesaran MH (2007) A simple panel unit root test in the presence of cross‐section dependence. J Appl Econ 22(2):265–312. https://doi.org/10.1002/jae.951

Pfeiffer B, Mulder P (2013) Explaining the diffusion of renewable energy technology in developing countries. Energy Econ 40:285–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2013.07.005

Qayyum M, Yu Y, Tu T, Nizamani MM, Ahmad A, Ali M (2022) Relationship between economic liberalization and intellectual property protection with regional innovation in China. A case study of Chinese provinces. Plos One 17(1):e0259170. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259170

Raihan A, Rahman SM, Ridwan M, Sarker T, Ben-Salha O, Rahman MM, Zimon G, Sahoo M, Dhar BK, Roshid MM (2025a) Dynamic influences of different energy sources, energy efficiency, technological innovation, population, and economic growth toward achieving net zero emissions in the United Kingdom. Innov Green Dev 4(4):100273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.igd.2025.100273

Raihan A, Rahman SM, Sarker T, Ridwan M, Sahoo M, Dhar BK, Roshid MM, Islam S, Zimon G, Bari AM (2025b) Tourism-energy-economy-environment nexus toward sustainable and green development in Malaysia. Innov Green Dev 4(4):100257

Raiser K, Naims H, Bruhn T (2017) Corporatization of the climate? Innovation, intellectual property rights, and patents for climate change mitigation. Energy Res Soc Sci 27:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2017.01.020

Rasheed MQ, Yuhuan Z, Haseeb A, Saud S (2024) Unpacking the stance of upgradation of industrial structure, technological trade, and sustainable development in top‐ten high‐income countries. Natural Resources Forum

Rasheed MQ, Yuhuan Z, Nazir M, Ahmed Z, Yu X (2025) How do semiconductors, artificial intelligence, geopolitical risk, and their moderating effects shape renewable energy production in leading semiconductor manufacturing countries? Technol Soc 80:102761. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2024.102761

Reed R, Storrud‐Barnes S, Jessup L (2012) How open innovation affects the drivers of competitive advantage: Trading the benefits of IP creation and ownership for free invention. Manag Decis 50(1):58–73

Renewables—Energy System (2023) IEA. https://www.iea.org/energy-system/renewables

Riaz MH, Islam S, Ahmed Z, Khan M, Roshid MM, Dhar BK, Uddin MS (2025) Nonlinear effects of ICT-trade openness on sustainable energy transition in Bangladesh. Energy Policy 206:114784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2025.114784

Rosenthal SS, Strange WC (2004) Evidence on the nature and sources of agglomeration economies. In Handbook of regional and urban economics (Vol. 4, pp. 2119–2171). Elsevier

Sarabdeen J, Ishak MMM (2024) Intellectual property law protection for energy-efficient innovation in Saudi Arabia. Heliyon, 10(9). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e29980

Shen C, Li S, Wang X, Liao Z (2020) The effect of environmental policy tools on regional green innovation: Evidence from China. J Clean Prod 254:120122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120122

Shen J, Luo C (2015) Overall review of renewable energy subsidy policies in China–Contradictions of intentions and effects. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 41:1478–1488. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2014.09.007

Sweet CM, Maggio DSE (2015) Do stronger intellectual property rights increase innovation? World Dev 66:665–677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.08.025

Tappeiner G, Hauser C, Walde J (2008) Regional knowledge spillovers: Fact or artifact? Res Policy 37(5):861–874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2007.07.013

Tobin J (1984) On the efficiency of the financial-system. Lloyds Bank Annu Rev 153:1–15

Viglioni MTD, Calegario CLL, Viglioni ACD, Bruhn NCP (2024) Foreign direct investment and environmental degradation: Can intellectual property rights help G20 countries achieve carbon neutrality? Technol Soc 77:102501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2024.102501

Voumik LC, Ghosh S, Rashid M, Das MK, Esquivias MA, Rojas O (2024) The effect of geopolitical risk and green technology on load capacity factors in BRICS. Uti Policy 88:101757. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jup.2024.101757

Wang J-Z, Feng G-F, Chang C-P (2024) How does political instability affect renewable energy innovation? Renewable Energy, 120800

Wang Q-J, Feng G-F, Wang H-J, Chang C-P (2021) The impacts of democracy on innovation: Revisited evidence. Technovation 108:102333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2021.102333

Wen J, Okolo CV, Ugwuoke IC, Kolani K (2022) Research on influencing factors of renewable energy, energy efficiency, on technological innovation. Does trade, investment and human capital development matter? Energy Policy 160:112718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2021.112718

World Trade Organisation (WTO) (2014) WTO | Intellectual Property (TRIPS)—What are intellectual property rights? https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/trips_e/intel1_e.htm

Xu X, Chen X, Xu Y, Wang T, Zhang Y (2022) Improving the innovative performance of renewable energy enterprises in China: Effects of subsidy policy and intellectual property legislation. Sustainability 14(13):8169. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14138169

Yin H-T, Wen J, Chang C-P (2022) Science-technology intermediary and innovation in China: Evidence from State Administration for Market Regulation, 2000–2019. Technol Soc 68:101864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2022.101864

Zhang D, Zheng M, Feng G-F, Chang C-P (2022) Does an environmental policy bring to green innovation in renewable energy? Renew Energy 195:1113–1124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2022.06.074

Zhang F, Wang Q, Li R (2025) How does clean energy reshape the nonlinear relationship between artificial intelligence and carbon emissions? Evidence from renewable and nuclear energy. Energy Econ, 108785. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2025.108785

Zheng M, Feng G-F, Jang C-L, Chang C-P (2021) Terrorism and green innovation in renewable energy. Energy Econ 104:105695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105695

Zhu X, Asimakopoulos S, Kim J (2020) Financial development and innovation-led growth: Is too much finance better? J Int Money Financ 100:102083. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jimonfin.2019.102083

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the RKAT of Universitas Sebelas Maret for the 2025 fiscal year through the INTERNATIONAL COLLABORATIVE RESEARCH (KI-UNS) scheme under Grant No. 369/UN27.22/PT.01.03/2025 and the Geran Putra Berimpak sponsored by Universiti Putra Malaysia under Grant No. GPB/2024/9811100.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HL: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, and visualization. LZ: conceptualization, methodology, resources, writing—review and editing. YS: conceptualization, methodology, supervision. FK: conceptualization, methodology, supervision. AS: conceptualization, methodology, supervision.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, H., Zhang, L., SUN, Y. et al. Nonlinear relationship between intellectual property protection and renewable energy innovation in 27 countries. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1802 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06185-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06185-w