Abstract

Since its emergence in 2022, Generative Artificial Intelligence (Generative AI) has rapidly gained widespread application in the field of academic English writing (EAW), triggering multifaceted transformations in EAW practices, particularly in the construction of authorial stance. Doctoral dissertations, due to their stringent demands for academic depth and originality, serve as an ideal subject for investigating the impact of Generative AI. EFL (English as a Foreign Language) doctoral students, often prone to language anxiety, are more likely to adopt passive writing strategies, which may undermine the expression of authorial stance. Therefore, this study, based on corpora from sub-disciplines within applied linguistics with high and low exposure to AI, employs a Difference-in-Differences (DiD) design to systematically examine the influence of Generative AI on stance construction in doctoral dissertations during two phases: the introduction period (2019–2021) and the diffusion period (2022–2024). The findings indicate that Generative AI is reshaping stance strategies in academic writing, driving a shift towards more deterministic and objective argumentation styles, while potentially weakening the explicit expression of authorial identity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Research background

The digital transformation of Academic English Writing (EAW) has evolved through three distinct phases: the initial phase, characterised by tool-assisted writing with digital libraries and collaborative platforms (Schcolnik, 2018; Strobl et al., 2019); the intermediate phase, marked by automated correction tools centred on grammar-checking software (Strobl et al., 2019); and the current phase, dominated by Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI) (e.g. GPT series), which focuses on semantic generation (Su et al., 2023). Generative AI encompasses a range of functionalities, from responding to queries to generating content (Dwivedi et al., 2023). It is capable of producing human-like text based on contextual cues (Van Dis et al., 2023) and demonstrates superior natural language understanding and higher efficiency in response compared to earlier AI systems (Zou and Huang, 2023). Additionally, it supports multilingual dialogue. However, it may undermine EAW practices by disseminating misinformation and encouraging plagiarism, thereby affecting the construction of authorial stance (Barrot, 2023).

In academic writing, stance refers to the author’s perspective in their discourse, encompassing their personal emotions, attitudes, and evaluations towards propositions (Conrad and Biber, 2000). As a core rhetorical strategy in academic discourse, its construction relies on the interplay of metadiscursive markers such as hedges and boosters (Hyland, 2005). Clear stance construction helps authors establish a coherent argumentative framework, making it easier for readers to grasp the core ideas and significance of the research, thereby providing a solid foundation for academic dialogue and further inquiry. While Generative AI can enhance writing efficiency and optimise expression, it also carries risks of stance ambiguity and academic dependency. These effects vary across different types of academic writing, particularly in doctoral dissertations, where the demands for academic depth and originality make such impacts especially noteworthy.

Doctoral students are often described as ‘advanced writers and apprentice scientists’ (Flowerdew and Li, 2007), yet this group is frequently overlooked within the writing community (Kessler, 2020). Existing research has primarily focused on areas such as Generative AI writing assessment (e.g. Guo and Wang 2023, Zhang and Hyland 2018), teachers’ use of Generative AI (e.g. Fleckenstein et al. 2024, Zhao 2024), and Generative AI-generated feedback (e.g. Kasneci et al. 2023, Lund et al. 2023). However, there is limited understanding of how Generative AI influences the textual production of doctoral theses. Furthermore, existing studies (Nañola et al., 2025) suggest that AI-generated texts align more closely with expert writing, while student-authored texts resemble novice writing. This raises the question of how Generative AI impacts the writing of experts (i.e. doctoral students). This study aims to deepen the understanding of Generative AI-empowered EAW and explore its potential implications for writing outcomes. By analysing doctoral theses before and after the widespread adoption of Generative AI, this study seeks to elucidate how Generative AI may influence the expression and construction of authorial stance, thereby assisting authors in using Generative AI effectively, ethically, and responsibly in EAW (UNESCO, 2023).

Literature review

Generative AI empowered EAW

Generative AI encompasses a broad spectrum of applications, with its earliest manifestation being DALL·E, a text-to-image model developed by OpenAI in January 2021. DALL·E demonstrated the ability to generate creative images based on textual descriptions. However, it was not until the advent of ChatGPT in 2022 that Generative AI was formally applied to EAW, beginning to reshape the practical landscape of this field. The impact of Generative AI on academic writing has sparked a dualistic debate characterised by ‘technological empowerment versus cognitive risks’ (Derakhshan and Ghiasvand, 2024). Proponents of technological empowerment highlight the positive contributions of AI tools in refining language use (Yang and Li, 2024), enhancing the quality of argumentation (Su et al., 2023), providing objective feedback (Dikli, 2006; Wang et al., 2012), enriching student learning experiences (Ghaleb Barabad and Bilal Anwar, 2024), freeing up teachers’ time (Warschauer and Grimes, 2008), and simplifying knowledge management (Ranalli, 2018). Conversely, advocates of cognitive risk theory caution against potential issues such as the homogenisation of stance construction (Song and Song, 2023) and the weakening of critical thinking (Mizumoto et al., 2024), which may undermine authorial identity construction and academic integrity (Crosthwaite and Baisa, 2023; Yan, 2023). Nevertheless, it is undeniable that Generative AI has become an indispensable part of EAW. As Warschauer (2023, p.5) stated, ‘even if we could ban it, we shouldn’t.’ Effective use of Generative AI as a supplementary tool in academic English writing requires a certain level of proficiency (Woo et al., 2023), particularly among advanced academic writers such as doctoral candidates.

Generative AI-empowered doctoral thesis writing

Even before the widespread adoption of Generative AI, discussions surrounding doctoral candidates’ EAW proficiency had already become a focal point in English education research (Caffarella and Barnett, 2000). The doctoral thesis, as a core vehicle for disciplinary socialisation (Paltridge and Starfield, 2019), serves a dual function in stance construction: its cognitive function reflects the researcher’s degree of commitment to knowledge claims (Hyland, 2005), while its social function constructs academic identity and secures recognition within the scholarly community (Swales, 1990). The integration of Generative AI is transforming this process, engaging in activities such as brainstorming and literature review during the initial stages of EAW (Dwivedi et al., 2023; Kishore et al., 2023). Research indicates that doctoral candidates exhibit two collaborative modes with AI: ‘surface-level transplantation’ (replicating AI output) and ‘deep reconstruction’ (critical integration) (Nguyen et al., 2024). However, English as a Foreign Language (EFL) doctoral candidates, due to language anxiety, are more prone to adopting passive writing strategies (e.g. Zou and Huang 2024), which may undermine authorial stance construction (e.g. Song and Song 2023). Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the impact of Generative AI on doctoral candidates’ stance construction, which can be achieved through textual analysis (e.g. Berber Sardinha 2024, Stapleton 2001). However, existing research predominantly focuses on surface-level linguistic features (e.g. lexical complexity), leaving a gap in understanding the systemic impact on cognitive stance frameworks.

Stance research

Research on academic stance construction in applied linguistics has undergone three major shifts. Early studies (1980–2000) were grounded in Chafe’s (1986) theory of evidentiality and Ochs and Schieffelin’s (1989) theory of affect, examining markers of knowledge sources and emotional intensity in academic writing, respectively. Subsequently, Biber and Finegan (1989) introduced ‘stance’ as an integrative concept, which Hyland (2005) further developed into a four-dimensional analytical framework: hedges, boosters, attitude markers, and self-mention. Hedges refer to linguistic devices that express uncertainty about a proposition or the author’s own claims, such as probably, it suggests, and may. Boosters are used to convey certainty and assertiveness, such as show, demonstrate, and must. Attitude markers express the author’s emotional stance, directly and explicitly conveying their position and eliciting reader empathy, such as interesting, important, and agree. Self-mention involves the use of first-person pronouns to assert authority and ownership of ideas. This framework transcends disciplinary boundaries and has been widely applied in cross-disciplinary (Charles, 2007; Hyland, 2015), cross-linguistic (Lee and Casal, 2014), and proficiency-level (Crosthwaite et al., 2017; Wu and Paltridge, 2021) studies. However, with the rise of Generative AI, research on academic stance construction has entered the ‘technologically mediated era’ (2022–present), giving rise to the concept of ‘technologically-mediated stance’ (Ou et al., 2024). Researchers are now exploring how Generative AI is reshaping academic rhetorical strategies.

However, the current literature predominantly focuses on chapters such as abstracts (Alghazo et al., 2021) and discussions (Cheng and Unsworth, 2016), with insufficient attention paid to the introduction section, which carries the declaration of research originality. The stance construction in this chapter is directly linked to knowledge innovation (Chen et al., 2022). Existing studies are largely conducted in educational environments with relatively high English proficiency, overlooking the additional challenges faced by EFL doctoral students, such as language anxiety when using technology. Moreover, research has primarily focused on general EAW, with limited exploration of variations within subfields of applied linguistics. Stance marker analysis often relies on synchronic corpus methods, making it difficult to capture the dynamic impact of technological intervention. Additionally, there is a lack of theoretical explanation regarding how AI reconstructs cognitive stance frameworks, with insufficient mechanistic insights.

In summary, since the emergence of Generative AI in 2022, its impact on the stance construction in the introduction chapters of English doctoral theses by Chinese EFL students remains underexplored. Furthermore, other factors, such as thesis topics and methodological differences, may also influence stance construction and must be considered. Therefore, this study proposes the following research questions:

-

1.

Before Technological Intervention (2019–2021), are there systematic differences in stance construction between high AI-exposure and low AI-exposure subfields within applied linguistics?

-

2.

Does Generative AI lead to significant changes in stance construction in high AI-exposure subfields? Which linguistic features are most significantly affected by Generative AI?

-

3.

How do thesis topics and methodologies moderate the impact of Generative AI on stance construction?

Research methodology

Data collection

This study aims to explore the impact of Generative AI on the stance construction in English doctoral theses by Chinese students, rather than comparing AI-generated texts with student-authored texts. Therefore, the corpus is divided into two periods: the technology introduction phase (2019–2021), during which Generative AI was not yet mature, and the texts reflect traditional academic writing patterns, and the technology diffusion phase (2022–2024), when Generative AI was increasingly applied in EAW, potentially leading to rapid changes in academic writing practices due to technological penetration. Although the time span is only 2 years, studies indicate that the adoption rate of Generative AI tools in higher education has grown exponentially (Jin et al., 2025).

To control for the influence of disciplinary backgrounds and trends in international journals on stance construction, this study refers to the Nature 2023 Discipline-Specific AI Adaptation Index. We select subfields within applied linguistics with high AI exposure (adaptation index≥7, e.g. computational linguistics, corpus linguistics) and low AI exposure (adaptation index≤3, e.g. sociolinguistics, language pedagogy). The corpus consists of doctoral theses from Chinese normal, comprehensive, science and engineering, and foreign language universities, focusing on applied linguistics, collected between 2019 and 2024. A stratified and random sampling method was used to construct the Corpus of Doctoral Theses, including 30 theses in computational linguistics and corpus linguistics (2019–2021), 30 theses in sociolinguistics and language pedagogy (2019–2021), 30 theses in computational linguistics and corpus linguistics (2022–2024), 30 theses in sociolinguistics and language pedagogy (2022–2024), totaling 120 theses.

Analytical procedure

First, based on prior evidence that applied disciplines such as engineering, business, information and computing sciences, and biomedical and clinical sciences show higher levels of AI knowledge, usage and ChatGPT-related activity than pure disciplines and arts / humanities (e.g., Qu et al., 2024; Raman, 2023), theses were categorised into high- and low-AI exposure groups. The introduction sections of the theses were tokenised using the NLTK toolkit, followed by the removal of stop words from the corpus. The stop words list included common academic high-frequency terms (e.g. ‘however’, ‘therefore’) to avoid excessive filtering of stance markers. Subsequently, in collaboration with a doctoral student in applied linguistics, the core themes (e.g. ‘corpus linguistics’, ‘second language acquisition’) were extracted based on keywords. For instance, papers containing keywords such as ‘BERT’ or ‘neural networks’ were labelled as ‘computational linguistics’, while those featuring terms like ‘classroom discourse’ or ‘teacher identity’ were categorised as ‘sociolinguistics’. The research methodology types (empirical, theoretical, mixed) were also annotated. Discrepancies, such as whether ‘may suggest’ should be classified as a hedge, were resolved through discussion, resulting in a final inter-annotator agreement of Kappa = 0.92, which exceeds the 0.75 threshold recommended by Cohen (1960).

Subsequently, based on Hyland’s (2005) framework for stance analysis in academic writing, the corpus analysis software AntConc is used to search for stance markers. Given the context-dependent and multifunctional nature of stance (Hyland, 2005), each entry is manually reviewed to exclude irrelevant terms, and the collocations of stance markers are carefully examined. To ensure the reliability of manual screening, 30% of the cases are self-annotated and reviewed by an expert in applied linguistics. After resolving discrepancies and establishing annotation guidelines, the author independently annotates the entire corpus. A month later, the corpus is re-coded, with a Kappa coefficient of 0.96 (calculated using SPSS 26.0), indicating high inter-rater reliability. Finally, the frequency counts of each stance marker are normalised to per thousand words to eliminate the influence of text length.

For Q1, paired-sample t-tests are conducted using SPSS 26.0 to examine whether there are significant differences in the four stance features (hedges, boosters, attitude markers, and self-mention) between the high AI-exposure and low AI-exposure subfields during the pre-technological intervention period (2019–2021). To control for intra-disciplinary heterogeneity, regression models are employed, incorporating topic distribution (e.g. weight of ‘corpus linguistics’ topics) and research methods (empirical, theoretical, mixed) as covariates. This ensures that any observed differences in stance construction are not confounded by variations in topic focus or methodological approaches.

For Q2, the following regression model is applied using SPSS 26.0: ΔStance construction=β0+β1(High-AI Subfield)+ β2(Post2022)+ β3(High-AI×Post2022)+ γX+ε. ΔStance construction represents the change in stance construction; β₀ is the intercept; β₁ captures the baseline difference between high and low AI-exposure subfields; β₂ accounts for the general temporal effect post-2022; β₃ is the core parameter, representing the net effect of Generative AI on high AI-exposure subfields; X is a matrix of control variables (e.g. topic, methodology); γ represents the coefficients of the control variables; ε is the error term. If β₃ is statistically significant and the control variables (γ) are not, this indicates that the net effect of Generative AI on stance construction is independent of topic and methodological influences. If the control variables are significant, further analysis of interaction effects is required to disentangle the moderating role of these factors.

For Q3, the study investigates whether Generative AI influences stance construction through topic-methodological alignment. By combining the distribution of thesis topics and methodologies, the analysis aims to reveal the mechanisms through which Generative AI affects stance construction in subfields with varying levels of AI exposure. Specifically, the study examines how topic selection (e.g. computational linguistics vs. sociolinguistics) moderates the impact of Generative AI on stance construction and whether methodological approaches (empirical, theoretical, mixed) influence the extent to which Generative AI reshapes stance strategies.

Finally, to complement the macro-level trends identified through quantitative analysis, this study selected representative papers from high- and low-AI exposure subfields for in-depth textual comparison, aiming to uncover the micro-level mechanisms through which Generative AI influences stance expression in academic writing.

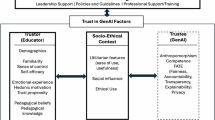

Identification of linguistic features

This study focuses on the analysis of stance construction through four core linguistic features: hedges, boosters, attitude markers, and self-mentions. These features play a crucial role in conveying the author’s stance, attitude, and identity in academic writing. Below, the classification framework and identification criteria for each feature are elaborated.

Classification and identification of hedges and boosters

Existing literature categorises hedges and boosters primarily along two dimensions: function and form.

From a functional perspective, Hyland and Zou (2021) classify hedges into four distinct categories: Downtoners, which weaken the strength of a statement (e.g. ‘largely,’ ‘fairly’); Rounders, which express approximation (e.g. ‘about,’ ‘around’); and Plausibility Hedges, which mark the plausibility of an assumption (e.g. ‘could,’ ‘probably’). They also categorise Boosters into three types: Intensity Boosters, which intensify the strength of a statement (e.g. ‘actually,’ ‘truly’); Extremity Boosters, which mark extremity (e.g. ‘most,’ ‘always’); and Certainty Boosters, which reflect the author’s certainty (e.g. ‘definitely,’ ‘evidently’).

Hu and Cao (2011) adopt a part-of-speech perspective to classify hedges into modal verbs (e.g. ‘might,’ ‘could’), cognitive verbs (e.g. ‘seem,’ ‘suggest’), cognitive adjectives or adverbs (e.g. ‘perhaps,’ ‘likely’), and other forms (e.g. ‘in general,’ ‘assumption’). Their classification of Boosters includes modal verbs (e.g. ‘must,’ ‘will’), cognitive verbs (e.g. ‘demonstrate,’ ‘find’), cognitive adjectives or adverbs (e.g. ‘actually,’ ‘clearly’), and other forms (e.g. ‘it is well known,’ ‘the fact that’). These classifications provide a comprehensive framework for understanding how linguistic devices can modulate the expression of certainty, approximation, and intensity in academic writing.

Building on these two classification dimensions (function and form), this study further refines the categories from a semantic-functional perspective, focusing on the role and intent of linguistic units within sentences. This approach is designed to adapt to the dynamic analysis of stance construction empowered by Generative AI. The specific classifications are in Table 1 and Table 2.

Classification and identification of attitude markers

The classification of attitude markers is primarily based on Hyland’s (2005) metadiscourse theory and Martin and White’s (2005) Appraisal Theory, which focus on how authors express emotions, judgements, and evaluations through language. The specific classification is in Table 3.

Classification and identification of self-mentions

The classification of self-mentions is based on Hyland’s (2001) theory of authorial identity construction and Ivanic’s (1998) framework of academic identity, emphasising how authors construct academic authority and engagement through linguistic choices. The specific classification is in Table 4.

Results

Overall characteristics of doctoral students’ stance markers (RQ1)

The analysis of systematic differences in stance construction between high AI-exposure and low AI-exposure subfields in applied linguistics during the pre-technological intervention period (2019–2021) revealed the following (see Table 5).

Hedges: No significant overall difference was observed (t = –1.07, p = 0.30). However, significant differences were found in the subcategories of possibility expression (t = –8.12, p < 0.001) and conditional expression (11.4 ± 0.4; t = 20.00, p < 0.001). This indicates that the high AI group was more cautious in hypothetical statements and more frequent in logical conditional expressions.

Boosters (t = 0.29, p = 0.77), attitude markers (t = 0.20, p = 0.84), and self-mentions (t = 0.28, p = 0.78) showed no significant differences between the two groups, satisfying the parallel trends assumption and making them suitable for subsequent difference-in-differences (DiD) analysis.

However, independent sample t-tests revealed that while there was no significant overall difference in hedges during the baseline period (p = 0.30), significant differences existed in the subcategories of possibility expression and conditional expression (p < 0.001), which could affect the reliability of subsequent DiD analysis. To address this, the study introduced baseline values as control variables in the DiD model to adjust for the initial differences in possibility and conditional expression between the high and low AI groups.

The impact of generative AI on stance construction and disciplinary heterogeneity (2022–2024) (RQ2)

After the diffusion of technology (2022–2024), the changes in stance construction in high AI-exposure subfields significantly differed from those in low AI-exposure subfields (see Table 6). After controlling for baseline differences, the DiD model results showed that Generative AI significantly reduced the use of hedges in the high AI group (β₃ = –1.20, p = 0.02), particularly in possibility expression (β₃ = –0.60, p = 0.05) and speculative expression (β₃ = –0.35, p = 0.10). This indicates that Generative AI significantly reduced caution in hypothetical statements.

At the same time, the use of boosters in the high AI group showed a marginally significant increase (β₃ = +0.93, p = 0.08), with conclusive expression significantly increasing (β₃ = +0.78, p = 0.02), reflecting the strengthening effect of Generative AI on argumentative force. Additionally, attitude markers overall decreased (β₃ = –0.67, p = 0.02), but evaluative expression significantly increased (β₃ = +0.67, p = 0.02), suggesting that Generative AI tends to promote objective expression rather than emotional or stance-based expression.

Regarding self-mentions, the use of authorial identity markers in the high AI group significantly increased (β₃ = +0.62, p = 0.01), while changes in first-person singular and plural were not significant (p > 0.05). This suggests that Generative AI favours implicit identity construction (e.g. ‘this study’ instead of ‘I argue’).

Cross-group comparisons further reveal the heterogeneity of the high/low AI groups’ responses to the technology (see Table 7). The high AI group’s use of hedges significantly decreased by 14.8%, while the low AI group only saw a 1.0% decrease, resulting in an inter-group difference of –13.8% (p < 0.01). In terms of boosters, the high AI group’s usage increased by 11.2%, significantly higher than the low AI group’s 2.5% increase (inter-group difference: +8.7%, p = 0.08). The use of attitude markers decreased by 10.8% in the high AI group, significantly higher than the low AI group’s 1.7% decrease (inter-group difference: –9.1%, p = 0.02). However, there was no significant difference in the change of self-referential expressions between the high/low AI groups (inter-group difference: +6.3%, p = 0.34), although the high AI group’s author identity markers significantly increased (β3 = + 0.62, p = 0.01).

The moderating mechanisms of topics and methodology (RQ3)

The extended DiD model results (see Table 8) show that, in the core effect, Generative AI significantly reduced the use of hedges in the high AI group (β3 = –1.75, p < 0.01), especially in theses related to corpus linguistics, where the reduction in hedges was more pronounced (interaction term β = –0.43, p < 0.05). This indicates that Generative AI tends to optimise the argumentative logic of technical topics. Additionally, the reduction trend of attitude markers was more evident in papers employing empirical research methods (β = +0.17, p > 0.05), suggesting that Generative AI may promote objective expression through standardised writing processes.

Meanwhile, the impact of Generative AI on boosters did not reach a significant level (β3 = +0.85, p > 0.05), but the increase in conclusive expressions (β3 =+0.78, p = 0.02) was significant, indicating that Generative AI may enhance argumentative strength by reinforcing conclusive statements. For self-referential expressions, the impact of Generative AI did not reach a significant level (β3 = +0.18, p > 0.05), but the increase in author identity markers was significant (β3 = +0.62, p = 0.01), suggesting that Generative AI tends to build implicit author identities.

In summary, the impact of Generative AI on stance construction in high AI exposure subfields is significantly different from that of the low AI group. This is mainly reflected in the reduction of hedges, the increase in boosters and evaluative expressions, and the strengthening of author identity markers. These heterogeneous changes reflect the influence of Generative AI on the academic writing style of high AI groups, especially in optimising argumentative logic and objectivity.

Qualitative textual analysis

To complement the macro-level trends identified through quantitative analysis, this study selected representative papers from high- and low-AI exposure subfields for in-depth textual comparison, aiming to uncover the micro-level mechanisms through which Generative AI influences stance expression in academic writing. The following examples, drawn from the introduction sections of doctoral theses published in 2023 (AI diffusion period) and 2019 (pre-AI adoption period), illustrate specific patterns of linguistic evolution:

Example 1: Transformation of Stance Expression in a High-AI Exposure Subfield (Computational Linguistics)

2023 Thesis (AI Diffusion Period)

‘The proposed neural architecture clearly demonstrates superior performance in syntactic parsing tasks (F1 = 0.92), which conclusively validates our hypothesis. It is noteworthy that previous approaches (e.g. rule-based systems) failed to achieve comparable accuracy under the same experimental conditions. ’

2019 Thesis (Pre-AI Adoption Period)

‘Our preliminary results suggest that the hybrid model may potentially improve parsing accuracy, though further validation is required. We tentatively argue that traditional rule-based systems might have limitations in handling complex syntactic variations. ’

In the 2023 text, the frequency of boosters (e.g. ‘clearly demonstrates,’ ‘conclusively validates’) increased significantly by 15.6% compared to 2019, replacing hedges such as ‘may potentially’ and ‘tentatively argue.’ ‘This shift reflects an emphasis on conclusiveness but may undermine the ‘rhetorical prudence’ emphasised by Hyland (2005). Simultaneously, a trend towards depersonalisation is more pronounced in the 2023 text. Unlike the frequent use of first-person plural (e.g. ‘We argue’) to construct a collective authorial identity in the 2019 text, the 2023 text predominantly employs passive constructions (e.g. ‘It is noteworthy that…’) and possessive pronouns (e.g. ‘our hypothesis’) to diminish the researcher’s agency.

This stylistic transformation may be attributed to disciplinary motivations. In computational linguistics, the pursuit of technical efficacy encourages authors to leverage AI tools to enhance the certainty of conclusions, leading to a preference for boosters and depersonalised expressions. Furthermore, critical expressions are intensified in the 2023 text. Unlike the 2019 text, which employed mitigating strategies (e.g. ‘might have limitations’) to evaluate prior research, the 2023 text favours direct negation, such as ‘failed to achieve.’ While this approach conveys decisiveness, it may also overlook the respect and understanding traditionally accorded to previous studies, further reflecting the discipline’s prioritisation of technical efficiency and conclusive findings.

Example 2: Stability of Stance Expression in a Low-AI Exposure Subfield (Sociolinguistics)

2023 Thesis (AI Diffusion Period)

‘We cautiously propose that teacher identity construction in multilingual classrooms could be mediated by institutional power dynamics, as tentatively illustrated in our interview excerpts. This interpretation might not fully capture the complexity of situated interactions.’

2019 Thesis (Pre-AI Adoption Period)

‘Our analysis suggests that teacher agency is likely constrained by macro-level language policies, though alternative explanations exist. We acknowledge that the small sample size limits the generalisability of our findings.’

Both texts exhibit a high frequency of hedges, such as ‘cautiously propose,’ ‘might not fully capture,’ and ‘likely constrained.’ Even in the 2023 text, the use of such hedges decreased by only 2.1%, demonstrating that the cautious attitude of qualitative research in the face of uncertainty remains largely unchanged despite technological advancements. Simultaneously, the first-person plural (e.g. ‘We propose,’ ‘Our analysis’) continues to play a significant role in academic writing in the AI era. It is not only used to construct an academic persona but also serves the dual function of claiming responsibility for research findings. This expression has not shifted towards ‘institutionalised discourse,’ as observed in some high-exposure fields, but instead continues to emphasise the researcher’s agency and accountability for the results.

In terms of critical expression, the 2023 text employs modal verbs (e.g. ‘could be’) and conditional adverbials (e.g. ‘as tentatively illustrated’) to achieve implicit critique. This approach aligns with the sociolinguistic tradition of valuing a ‘negotiated stance,’ which prioritises openness and flexibility in academic dialogue rather than directly negating or criticising prior research.

Example 3: Evolution of Co-occurrence Patterns of Stance Markers Across Subfields

2022 Computational Linguistics Thesis (AI Diffusion Period)

‘The experimental results definitively prove that transformer-based models significantly outperform previous architectures. This finding undoubtedly challenges the long-standing assumption that rule-based systems are irreplaceable in grammatical annotation tasks. ’

2023 Sociolinguistics Thesis (AI Diffusion Period)

‘We tentatively interpret these discourse patterns as possibly reflecting covert language ideologies, while recognising that our coding framework may not exhaustively account for all contextual variables. ’

In the high-AI exposure field of computational linguistics, boosters (e.g. ‘definitively prove,’ ‘undoubtedly challenges’) and attitude markers (e.g. ‘significantly outperform’) frequently co-occur. This linguistic pattern reflects a ‘techno-authoritative stance,’ emphasising the certainty and superiority of technological advancements, which aligns with the field’s prioritisation of technical efficacy and its high reliance on and active adoption of AI tools.

In contrast, the sociolinguistics text constructs a ‘reflective-negotiative stance’ through the use of hedges (e.g. ‘tentatively interpret,’ ‘possibly reflecting’) and self-mentions (e.g. ‘We recognise’). This stance underscores the cautiousness and context-sensitivity of the research, demonstrating the field’s resistance to the assimilation of AI tools. Sociolinguistics, with its focus on context, pragmatics, and researcher subjectivity, tends to favour hedges and self-mentions to express the researcher’s reflexivity and cautious attitude towards research findings.

Discussion

This study employed a DiD design to investigate the complex effects of GenAI on the evolution of stance markers in applied linguistics doctoral dissertations. Findings reveal that, moderated by disciplinary technocultural contexts, GenAI influences manifest as multi-layered processes of deconstruction and reconstruction. Our findings not only corroborate Generative AI’s role in enhancing students’ communicative performance and individual language development (Ou et al., 2024) but also extend this understanding by offering a more nuanced perspective on how AI reshapes the academic rhetorical ecosystem.

Our core finding—a significant 14.8% overall decline in ambiguous qualifiers, primarily driven by reductions in expressions of possibility (β3 = –0.60) and conjecture (β3 = –0.35)—validates Hyland’s (2024) contention that AI technologies are fundamentally restructuring academic discourse. This decline indicates that AI’s semantic prediction and logical optimisation capabilities are steering writing towards greater certainty, thereby diminishing expressions of cognitive uncertainty that have long served as hallmarks of cautious academic rhetoric. This finding resonates with observations in broader scientific literature (e.g. Qu et al., 2024) reporting the rapid adoption of AI tools in data-intensive fields.

Conversely, at the reconfiguration level, the marked increase in conclusive expressions within augmented utterances (β₃ = +0.78, p = 0.02) and the systematic rise in author identity markers (β₃ = +0.62, p = 0.01) reveal a new rhetorical equilibrium. This forms an intriguing dialogue with Schenck (2024)’s finding that AI tools may diminish individual rhetorical awareness. Our research further indicates that AI does not merely diminish author presence but prompts a shift in identity construction from personalised expressions (e.g. ‘I believe’) towards institutionalised ones (e.g. ‘this study contends’). This transition aligns with the long-term trend of ‘depersonalisation’ in academic style observed by Biber and Gray (2016), suggesting GenAI may be accelerating this process.

Moreover, a significant contribution of this study lies in providing micro-linguistic evidence of disciplinary differentiation, offering robust empirical support for Farber’s (2025) recently proposed theory of the ‘Disciplinary AI Adaptation Index’. Data reveal that the reduction in ambiguous restrictives is particularly pronounced in highly AI-adapted subfields such as corpus linguistics (interaction term β = –0.43, p < 0.05), aligning with this subfield’s data-driven nature and pursuit of explicit conclusions. Conversely, in subfields dominated by qualitative methods such as empirical research, the decline in attitude markers is negligible (β = +0.17, p > 0.05). This corroborates Curry and Lillis’ (2010) assertion that humanities-oriented research relies heavily on researchers’ subjective expression and exhibits relative resistance to technological change. These intra-disciplinary variations indicate that Generative AI’s influence is far from homogeneous, instead being profoundly intertwined with each subfield’s research paradigms and cultural traditions. However, other studies suggest that Generative AI’s stance expression in philosophy fails to conform to human writing conventions (Mo and Crosthwaite, 2025), a finding warranting future investigation.

Finally, this study reveals a cognitive shift: when processing texts, Generative AI tends to preserve the rigour of conditional logical connections while substantially reducing uncertainty in expressing cognitive stances (e.g. expressions of possibility). This indirectly corroborates Crosthwaite’s (2025) conclusion that Generative AI employs a narrower, more repetitive range of stance and interactional features. Similarly, Generative AI alters academic persuasion patterns by amplifying objective, conclusive arguments while diminishing subjective attitude markers. This finding provides cross-disciplinary evidence for Darwin (2025)’s argument regarding the critical importance of digital literacy in academic English writing. It underscores that in the AI era, scholars and students alike must develop a new competency: critically evaluating and utilising AI-generated content. This enables harnessing its efficiency advantages while safeguarding the nuance and critical thinking essential to scholarly argumentation.

Conclusions

Employing a DiD design, this study reveals Generative AI’s profound impact on stance expression in academic writing within applied linguistics. Key findings are as follows: Firstly, Generative AI is not a neutral tool; it catalyses a transformation in academic rhetorical practice, manifested through reduced use of qualifying language (particularly uncertainty markers) and increased use of intensifiers (especially conclusive expressions), resulting in a more direct and assertive writing style. Secondly, AI is reshaping authorial identity construction, driving a shift from institutionalised expressions of the ‘author’s voice’ towards the ‘text’s voice’. Finally, its impact exhibits significant variation across disciplinary subfields, confirming the pivotal role of disciplinary culture and technological adaptability in moderating AI’s influence.

The present study’s sample focuses on applied linguistics, which allows for in-depth revelation of this discipline’s characteristics but limits the generalisability of conclusions to other fields (such as natural language processing or second language acquisition). Future research could extend to disciplines with high AI exposure (e.g. computer science) and those with low exposure (e.g. philosophy) to validate and contrast these findings. Moreover, the current data only covers the initial phase of technological diffusion (2022–2024). While providing a valuable baseline for ‘early responses to technological disruption,’ it may not fully capture the long-term evolutionary impact of this technology. Longitudinal tracking studies are therefore crucial.

In summary, this research demonstrates that the introduction of Generative AI is reshaping the landscape of academic expression. It brings not merely efficiency gains, but challenges to established academic discourses, authorship conventions, and disciplinary methodological diversity. The scholarly community must respond to this transformation with both prudence and proactivity. By innovating teaching practices, reinforcing academic ethics, and cultivating critical digital literacy, we can ensure that technology serves the construction of scholarly knowledge without undermining the critical, creative, and humanistic core upon which it depends.

Data availability

The data supporting this study are subject to confidentiality restrictions imposed by Jilin University. Due to legal and contractual obligations, the raw data cannot be made publicly available. Requests for limited access may be directed to the corresponding author and will require written approval from all stakeholders.

References

Alghazo S, Al Salem MN, Alrashdan I (2021) Stance and engagement in English and Arabic research article abstracts [J]. System 103:102681

Barrot JS (2023) Using ChatGPT for second language writing: Pitfalls and potentials [J]. Assess Writ 57:100745

Berber Sardinha T (2024) AI-generated vs human-authored texts: A multidimensional comparison [J]. Appl Corpus Linguist 4

Biber D, Finegan E (1989) Styles of stance in English: Lexical and grammatical marking of evidentiality and affect [J]. Text Talk 9:124–193

Biber D, Gray B (2016) Grammatical complexity in academic English: Linguistic change in writing [M]. Cambridge University Press

Caffarella R, Barnett B (2000) Teaching doctoral students to become scholarly writers: The importance of giving and receiving critiques [J]. Stud High Educ 25:39–52

Cohen J (1960) A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas 20:37–46

Chafe WL (1986) Evidentiality in English conversation and academic writing. In: Chafe WL, Nicholas J (eds) Evidentiality: The linguistic coding of epistemology (Advances in Discourse Processes, Vol. 20) [M]. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing Corporation

Charles M (2007) Argument or evidence? Disciplinary variation in the use of the Noun that pattern in stance construction [J]. Engl Specif Purp 26:203–218

Chen N, Lam P, Yung AM (2022) Cross-disciplinary perspectives on research article introductions: The case of reporting verbs [J]. East Asian Pragmat 7:1–21

Cheng F-W, Unsworth L (2016) Stance-taking as negotiating academic conflict in applied linguistics research article discussion sections [J]. J Engl Acad Purp 24:43–57

Conrad S, Biber D (2000) Adverbial Marking of Stance in Speech and Writing [M]. Oxford University Press

Crosthwaite P, Baisa V (2023) Generative AI and the end of corpus-assisted data-driven learning? Not so fast! [J]. Appl Corpus Linguist 3:100066

Crosthwaite P, Cheung L, Jiang F (2017) Writing with attitude: Stance expression in learner and professional dentistry research reports [J]. Engl Specif Purp 46:107–123

Curry M, Lillis T (2010) Academic writing in a global context: The politics and practices of publishing in English [M]. Abingdon: Routledge

Darvin R (2025) The need for critical digital literacies in Generative AI-mediated L2 writing [J]. J Second Lang Writ 67:101186

Derakhshan A, Ghiasvand F (2004) Is ChatGPT an evil or an angel for second language education and research? A phenomenographic study of research-active EFL teachers’ perceptions [J]. Int J Appl Linguist 34(4):1246–1264

Dikli S (2006) An overview of automated scoring of essays [J]. J Technol Learn Assess 5:1–35

Dwivedi YK, Kshetri N, Hughes L, Slade EL, Jeyaraj A, Kar AK, Baabdullah AM, Wright R (2023) Opinion Paper: “So what if ChatGPT wrote it?” Multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational AI for research, practice and policy [J]. Int J Inf Manag 71:102642

Farber S (2025) Enhancing academic decision-making: A pilot study of AI-supported journal selection in higher education [J]. Innov Higher Educ 50(5):1813–1831

Fleckenstein J, Meyer J, Jansen T, Keller SD, Köller O, Möller J (2024) Do teachers spot AI? Evaluating the detectability of AI-generated texts among student essays [J]. Computers Educ: Artif Intell 6:100209

Flowerdew J, Li Y (2007) Language re-use among Chinese apprentice scientists writing for publication [J]. Appl Linguist 28(3):440–465

Ghaleb Barabad M, Bilal Anwar M (2024) Exploring ChatGPT’s role in English learning for EFL students: Insights and experiences [J]. Int J Innov Sci Res Technol 9(9):755–766

Guo K, Wang D (2023) To resist it or to embrace it? Examining ChatGPT’s potential to support teacher feedback in EFL writing [J]. Educ Inf Technol 29:8435–8463

Hu G, Cao F (2011) Hedging and boosting in abstracts of applied linguistics articles: A comparative study of English- and Chinese-medium journals [J]. J Pragmat 43:2795–2809

Hyland K (2001) Humble servants of the discipline? Self-mention in research articles [J]. Engl Specif Purp 20:207–226

Hyland K (2005) Metadiscourse: Exploring interaction in writing [M]. London & New York: Continuum (now Bloomsbury)

Hyland K (2015) Genre, discipline and identity [J]. J Engl Acad Purp 19:32–43

Hyland K, Zou H (2021) “I believe the findings are fascinating”: Stance in three-minute theses [J]. J Engl Acad Purp 50:100973

Ivanic R (1998) Writing and identity: The discoursal construction of identity in academic writing [M]. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company

Jiang F, Hyland K (2024) Does ChatGPT argue like students? Bundles in argumentative essays [J]. Appl Linguist amae 46(3):375–391

Jin Y, Yan L, Echeverria V, Gašević D, Martinez-Maldonado R (2025) Generative AI in higher education: A global perspective of institutional adoption policies and guidelines [J]. Comput Educ: Artif Intell 8:100348

Kasneci E, Sessler K, Küchemann S, Bannert M, Dementieva D, Fischer F, Gasser U, Kasneci G (2023) ChatGPT for good? On opportunities and challenges of large language models for education [J]. Learn Individ Differ 103:102274

Kessler M (2020) Technology-mediated writing: Exploring incoming graduate students’ L2 writing strategies with activity theory [J]. Comput Compos 55:102542

Kishore S, Hong Y, Nguyen A, Qutab S (2023) Should ChatGPT be banned at schools? Organizing visions for generative artificial intelligence (AI) in education. In Rising like a Phoenix: Emerging from the Pandemic and Reshaping Human Endeavours with Digital Technologies. Proceedings of the 44th International Conference on Information Systems (ICIS 2023). Hyderabad, India: Association for Information Systems

Lee JJ, Casal JE (2024) Metadiscourse in results and discussion chapters: A cross-linguistic analysis of English and Spanish thesis writers in engineering [J]. System 46:39–54

Lund B, Wang T, Mannuru N R, Shimray S, Wang Z (2023) ChatGPT and a new academic reality: Artificial intelligence-written research papers and the ethics of the large language models in scholarly publishing [J]. J Assoc Inf Sci Technol 74(5):570–581

Martin J, White PRR (2005) The language of evaluation: Appraisal in English [M]. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan

Mizumoto A, Yasuda S, Tamura Y (2024) Identifying ChatGPT-generated texts in EFL students’ writing: Through comparative analysis of linguistic fingerprints [J]. Appl Corpus Linguist 4:100106

Mo Z, Crosthwaite P (2025) Exploring the affordances of Generative AI large language models for stance and engagement in academic writing [J]. J Engl Acad Purp 75:101499

Nañola EL, Arroyo RL, Hermosura NJT, Ragil M, Sabanal JNU, Mendoza HB (2025) Recognizing the artificial: A comparative voice analysis of AI-Generated and L2 undergraduate student-authored academic essays [J]. System 130:103611

Qu Y, Tan MXY, Wang J (2024) Disciplinary differences in undergraduate students’ engagement with generative artificial intelligence. Smart Learn Environ 11:51

Nguyen A, Hong Y, Dang B, Huang X (2024) Human-AI collaboration patterns in AI-assisted academic writing [J]. Stud High Educ 49:847–864

Ochs E, Schieffelin BB (1989) Language has a heart [J]. Text Talk 9:26–27

Ou AW, Stöhr C, Malmström H (2024) Academic communication with AI-powered language tools in higher education: From a post-humanist perspective [J]. System 121:103225

Paltridge B, Starfield S (2019) Thesis and dissertation writing in a second language: A handbook for students and their supervisors [M]. Routledge

Ranalli J (2018) Automated written corrective feedback: how well can students make use of it? [J]. Comput Assist Lang Learn 31:653–674

Raman R (2023) Transparency in research: An analysis of ChatGPT usage acknowledgment by authors across disciplines and geographies. Account Res 32:277–298

Schcolnik M (2018) Digital tools in academic writing? [J]. J Acad Writ 8(1):121–130

Schenck A (2024) ChatGPT is powerful, but does it have power distance? A study of culturally imbued discourse in AI-generated essays [J]. Int J Adult Educ Technol 15(1):1–17

Song C, Song Y (2023) Enhancing academic writing skills and motivation: assessing the efficacy of ChatGPT in AI-assisted language learning for EFL students [J]. Front Psychol 14:1260843

Stapleton P (2001) Assessing critical thinking in the writing of Japanese University students: Insights about assumptions and content familiarity [J]. Writ Commun 18:506–548

Strobl C, Ailhaud E, Benetos K, Devitt A, Kruse O, Proske A, Rapp C (2019) Digital support for academic writing: A review of technologies and pedagogies [J]. Comput Educ 131:33–48

Su Y, Lin Y, Lai C (2023) Collaborating with ChatGPT in argumentative writing classrooms [J]. Assess Writ 57:100752

Swales J (1990) Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings [M]. Cambridge University Press

Sabzalieva, E., & Valentini, A. (2023) ChatGPT and artificial intelligence in higher education: Quick start guide [R]. Paris: UNESCO

Van Dis E, a, Bollen M, Zuidema J, Van Rooij W, Bockting R (2023) ChatGPT: five priorities for research [J]. Nature 614:224–226

Wang Y-J, Shang H-F, Briody P (2012) Exploring the impact of using automated writing evaluation in English as a foreign language university students’ writing [J]. Comput Assist Lang Learn 26:1–24

Warschauer M, Grimes D (2008) Automated writing assessment in the classroom [J]. Pedagog Int J 3:22–36

Warschauer M, Tseng W, Yim S, Webster T, Jacob S, Du Q, Tate T (2023) The affordances and contradictions of AI-generated text for writers of english as a second or foreign language [J]. J Second Lang Writ 62:101071

Woo DJ, Susanto H, Yeung CH, Guo K, Fung AKY (2024) Exploring AI-Generated Text in Student Writing: How Does AI Help?[J]. Lang Learn Technol 28(2):183–209

Wu B, Paltridge B (2021) Stance expressions in academic writing: A corpus-based comparison of Chinese students’ MA dissertations and PhD theses [J]. Lingua 253:103071

Yan D (2023) Impact of ChatGPT on learners in a L2 writing practicum: An exploratory investigation [J]. Educ Inf Technol 28:13943–13967

Yang L, Li R (2024) ChatGPT for L2 learning: Current status and implications [J]. System 124:103351

Zhang Z, Hyland K (2018) Student engagement with teacher and automated feedback on L2 writing [J]. Assess Writ 36:90–102

Zhao W (2024) A study of the impact of the new digital divide on the ICT competences of rural and urban secondary school teachers in China [J]. Heliyon 10:e29186

Zou M, Huang L (2023) To use or not to use? Understanding doctoral students’ acceptance of ChatGPT in writing through technology acceptance model [J]. Front Psychol 14:1259531

Zou M, Huang L (2024) The impact of ChatGPT on L2 writing and expected responses: Voice from doctoral students [J]. Educ Inf Technol 29:13201–13219

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Wei Zhao wrote the main manuscript text, collected the corpora, prepared figures and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, W. Reconstructing stance in EFL doctoral thesis writing through generative artificial intelligence. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 12, 1963 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06249-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-06249-x