Abstract

Hailstorms are analyzed across the United States using explicit hailstone size calculations from convection-permitting regional climate simulations for historical, mid-century, and end of twenty-first-century epochs. Near-surface hailstones <4 cm are found to decrease in frequency by an average of 25%, whereas the largest stones are found to increase by 15–75% depending on the greenhouse gas emissions pathway. Decreases in the frequency of near-surface severe hail days are expected across the U.S. High Plains, with 2–4 fewer days projected—primarily in summer. Column-maximum severe hail days are projected to increase robustly in most locations outside of the southern Plains, a distribution that closely mimics projections of thunderstorm days. Primary mechanisms for the changes in hailstone size are linked to future environments supportive of greater instability opposed by thicker melting layers. This results in a future hailstone size dichotomy, whereby stronger updrafts promote more of the largest hailstones, but significant decreases occur for a majority of smaller diameters due to increased melting.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hail—frozen hydrometeors originating from convection exceeding 5 mm in any dimension—is a common phenomenon found in many regions of the world1. Most frequent across the Great Plains of North America, damaging hail occurs an average of 158 days per year in the United States2, which translates to roughly $10B of insured losses annually before accounting for agricultural losses. Losses due to hail and other severe convective storms have quintupled in the United States since 20083, raising questions from scientists, industry, and members of the public about the roles of a warming climate and changing socioeconomic exposure4. Despite this interest, the potential impacts of anthropogenic climate change on hailstorm frequency and intensity are relatively unknown, owing to the coarse horizontal grid spacing (≈100 km) that current general circulation models (GCMs) simulate relative to the scale of hail-producing thunderstorms (≈1–10 km). Understanding how hailstorms may change in the future is critical for estimating societal impacts for a variety of stakeholders.

Most research focusing on future hail potential has used an environmental proxy approach from GCMs, whereby an ingredients-based approach5 is used to assess hail occurrence in future climate regimes (i.e., the likelihood of future hail events is implicitly determined by changes in the fundamental variables known to be associated with hailstorms). The consensus from this work suggests that a warming climate will increase the number of days with favorable severe convective storm ingredients, driven primarily by updraft strength associated with increases in convective instability6,7,8,9. While these works are generalizable to severe convective storms broadly, they lack the ability to project changes in hail characteristics specifically due to the large variability in atmospheric environments that support hailstorms10,11,12,13,14. A notable exception to this generality was a study15 using environmental profiles from three regional climate models (RCMs) as input to a 1-D hail growth model16 to predict maximum surface hailstone sizes over North America during the 2041–2070 study period. A decrease in the frequency of small hail and an increase in the frequency of large hail was noted; the former was due to a greater melting depth, and the latter to increases in updraft strength. While these approaches are informative, they lack the ability to explicitly simulate hail-producing storms and their microphysical characteristics in future climates. Simply, hailstorm-supportive environments are an important—but not sufficient—consideration for hailstorm occurrence.

As an alternative to the implicit environmental approaches, a few recent studies have explored the use of a pseudo-global warming (PGW) approach as a means to explicitly simulate the impact of anthropogenic climate change on severe convective storms17,18,19. The PGW method applies a mean thermodynamic (and occasionally kinematic) delta from a suite of GCM output to the initial and lateral boundary state fields of reanalysis cases that are then fed into a convection-permitting numerical model. The most recent of these works20 analyzed historical hailstorm cases under control and PGW-modified conditions, finding stronger updrafts for all cases, but hailstone size distributions dependent on season and location in the atmospheric vertical profile (i.e., surface versus aloft). Emblematic of many PGW case studies, this work is also limited by a small sample size of seven events. While not comprehensive, these works do offer insight into a process-based understanding of potential changes and are relatively inexpensive from a computational perspective.

In the last decade, research into how climate change is affecting severe convective storms has increasingly employed a dynamical downscaling approach21,22. Dynamical downscaling here refers to the use of relatively coarse resolution model output incapable of resolving thunderstorms (e.g., GCM output fields) as initial and lateral boundary conditions to force convection-permitting (i.e., model horizontal grid spacing Δx ≤ 4 km23) simulations capable of explicitly examining meso-γ processes associated with hailstorms. This is similar to the limited area model approach used in day-to-day operational numerical weather prediction. This methodology has proven valuable for the assessment of historical and future convective storm populations24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33, but is computationally expensive (both in terms of processing and storage requirements) due to the horizontal grid spacing required to simulate without a cumulus parameterization scheme34. Overall, these works suggest notable changes in the frequency, spatial location, intensity, and variability of severe convective storms by the end of the 21st century that are seasonally and emissions pathway-dependent. Despite these valuable insights, most research using dynamical downscaling has focused on the aggregate response of severe convective storms to anthropogenic forcing and not specifically on the hazard of hail. In fact, a recent Nature Reviews article35 focusing on the effects of climate change on hailstorms suggests that, “more high-resolution numerical model simulations are required to better resolve hailstorm processes and to investigate expected future changes around the globe.”

To our knowledge, only two studies have explicitly investigated the future of hail across the U.S. using a dynamical downscaling framework at the thunderstorm scale. The first was a simulation using 1-km horizontal grid spacing over a limited domain covering Colorado during Jun–Aug and showed an increase in hail mass aloft but an increased melting level, which eliminated nearly all hail at the ground36. This work was limited by domain size and a select handful of event days during the warm season and is, thus, unable to characterize broad changes in hailstone populations. The other, and most parallel to the work herein, used dynamical downscaling of the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory Climate Model version 3 output to determine future changes in hail size frequency31. This work examined hail occurrence by using simulated hourly maximum column-integrated graupel (GRPLmax; kg m−2), which represents a vertically integrated mixing ratio of the rimed ice category (hail occurrence was derived ad hoc from limited auxiliary simulations using correlation to HAILCAST37). Broad spatial increases in GRPLmax values correlated to hail ≥3.5 cm in diameter were found over the U.S. for all seasons, whereas increases in GRPLmax correlated to ≥5 cm diameter hail were confined to the central U.S. during boreal spring and summer. While correlation does exist with surface hail size, the column-integrated nature of GRPLmax introduces notable caveats when trying to capture surface hail size for a wide spectrum of environmental regimes, mainly related to the influences of melting.

We approach the climate change and hail question by evaluating convection-permitting (Δx = 3.75 km) dynamically downscaled regional climate simulations (WRF-BCC; see Methods)38 across the U.S. using GCM output from the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) Community Earth System Model39. We present explicit hail size and frequency projections calculated from the model’s inline spectral bulk microphysics scheme for historical (HIST; 1990–2005), mid-century (MID; 2040–2055), and end of century (END; 2085–2100) experiments. This work marks the first comprehensive investigation of explicitly simulated hail size and frequency using both intermediate and pessimistic anthropogenic emissions pathways.

Results

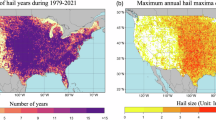

Comparison of hail day climatologies

We begin with comparison of mean annual and seasonal WRF-BCC near-surface severe hail days from the HIST epoch with two independent hail climatologies derived from GridRad (Doppler radar) and observed reports (Supplementary Fig. A1). While a one-to-one comparison should be performed with caution due to the differences in approaches and thresholds (see Online Methods), the purpose of this analysis was to gauge whether WRF-BCC could replicate the aggregate climatological attributes of severe hail. Overall, WRF-BCC reasonably reproduces the frequency, magnitude, timing, and location of severe hail days, though not without bias. Mean annual severe hail days from HIST (Supplementary Fig. A1a) suggest the highest frequencies in the central High Plains, which is corroborated by GridRad (Supplementary Fig. A1b) and observed reports (Supplementary Fig. A1c). Two notable areas of bias were found, the first located in the northern High Plains, where WRF-BCC simulated a higher number of JJA severe hail days versus both GridRad and reports. The second was a low bias in most areas east of the Mississippi River, a majority of which occurred in MAM. These biases could be reduced by using regionally dependent diameter thresholds, but such a topic is extraneous to this discussion (e.g., the WRF-BCC high bias in the northern High Plains may be due to a lack of observed reports). More importantly, WRF-BCC is able to simulate the known seasonal progression of severe hail day frequency climatology (Supplementary Fig. A1d–g) as shown by reports (Supplementary Fig. A1l–o), with differences comparable to GridRad (Supplementary Fig. A1h–k).

Projections of hail size

Daily-maximum (1200–1200 UTC) values of near-surface and column-maximum hail diameters were extracted at each native WRF-BCC grid point in the analysis domain and binned in 0.5 cm increments for each climate epoch to analyze size distributions (Fig. 1). Statistically significant broad decreases were found for near-surface maximum hail diameters between 1.5 and 3.5 cm for all future epochs, whereas for sizes ≥4.5 cm, increases were noted (Fig. 1a). This inflection point between 4 and 4.5 cm suggests a varying response of near-surface hail diameter to climate change—one that favors increases in the largest hail sizes and a more sweeping decrease in frequency at smaller diameters. Relative changes for each projected epoch were sensitive to the emissions pathway and the selected time horizon (e.g., the largest frequency decreases and increases relative to HIST were in the END85 experiment).

Column-maximum hail size distribution changes were negligible for diameters ≤3.5 cm, but a robust increase (statistically significant at all sizes ≥4 cm for all epochs) occurred with the largest WRF-BCC hailstones (Fig. 1b). This includes a >25% increase in the frequency of ≥4.5 cm diameter hailstones for all future epochs and a >75% increase 5+ cm diameter hailstones for the END experiments relative to HIST.

Spatial changes

Widespread decreases of 2–4 days per year in near-surface severe hailstone diameter are projected across a majority of the Great Plains (Fig. 2a–e). These changes are emissions pathway-dependent, with a greater magnitude of decrease found when using RCP 8.5 experiments. East of the Mississippi River, projected changes in near-surface severe hail days were marginally increasing for most regions, though not in a statistically significant manner (Supplementary Fig. A2). Looking at severe hail days through the lens of column-maximum hail diameter shows quite different results, with robust increases of ≥5 days over the Midwest, Ohio Valley, and Northeast U.S. for all experiments (Fig. 2f–j). Decreases in the southern Great Plains and along the Gulf Coast were spatially similar for all future experiments, but were most prevalent in RCP 8.5 simulations. Broadly speaking, the spatial projections in column-maximum severe hail days—perhaps unsurprisingly—mirror those found in previous work examining thunderstorm days from WRF-BCC32.

Mean annual HIST a near-surface (top row) and f column-maximum (bottom row) severe hail days. b–e and g–j represent the change in mean annual days for each experiment from the respective HIST values. Statistical significance and percent relative change are shown in Supplementary Fig. A2.

Seasonal distributions of near-surface and column-maximum severe hail days were also analyzed (Figs. 3 and 4, respectively). For near-surface severe hail days, DJF was characterized broadly by decreases in portions of Texas and Oklahoma and mixed potential for change along the eastern and northeastern gradient of the maximum frequency shown in HIST. The largest decreases (and increases) were found in the spring and summer, with MAM showing more variability in the projections dependent on emissions pathway and time period. JJA exhibited the most significant across-epoch decreases in mean near-surface severe hail days, with the greatest change projected in the southern, central, and northern High Plains. All four experiments, but especially MID85, also portrayed increases in JJA hail days for a majority of locations east of the Mississippi River. Changes were less notable in SON, but all experiments recorded a spatial mean decrease of <0.5 days.

For projections of mean seasonal column-maximum severe hail days, DJF exhibited spatial changes similar (albeit different magnitudes) to that for near-surface (Fig. 4e, i, m, q). Greatest decreases were, again, found across the southern Great Plains, with changes similar for both RCPs and time epochs. The largest increases in DJF column-maximum severe hail days were found across the eastern third of the CONUS, especially for both END experiments. Changes in MAM days were more simulation-dependent, with increases projected in mean days for most areas in the Midwest and Mid-South (Fig. 4f, j, n, r). Simulated changes in the summer displayed a more latitudinal dipole structure, with decreases in mean JJA days across the Gulf Coast and southern United States, and the most consistent regional increases across the northeast United States. However, JJA did have the largest inter-experiment variability, which is showcased by focusing on individual states (Fig. 4g, k, o, s). Changes across the analysis domain for SON column-maximum severe hail days revealed an increasing pattern ranging from a spatial mean of three more days for MID45 to seven more days for END85 (Fig. 4h, l, p, t). Similar to the projected annual changes, the seasonal breakdown is similar to that found for thunderstorm days from previous research using WRF-BCC32.

As in Fig. 3, but for mean annual column max severe hail days.

Mechanisms for change

Explanations of the projected changes in hail size from WRF-BCC were explored by analyzing the underlying environmental mechanisms derived from the parent GCM. While we acknowledge that specific storm-scale details (e.g., updraft width, mesocyclone strength40) are important for determining maximum hail size, this discussion is focused on the broader environmental projections of melting level, 700–500 hPa lapse rate, parcel water vapor mixing ratio, deep-layer wind shear, and a composite of favorable atmospheric ingredients for significant hail (i.e., the significant hail parameter; SHIP).

Melting level has increased since 197941 and is projected to further increase across the domain regardless of the experiment (Supplementary Fig. A3). By MID, both emissions pathways suggest an annual mean increase ≈300 m. Divergence in melting level height projections occur toward the end of MID, with RCP 8.5 simulating an additional mean increase of 450 m by END, whereas additional increases in the RCP 4.5 scenario were <150m. For near-surface hail size and occurrence, any such increases in melting level height are likely to have the greatest influence on smaller hailstones prone to significant melting during their fall trajectories. We posit that a majority of the future decreases found in WRF-BCC smaller near-surface hail diameters (i.e., ≤4 cm) are due to increases in melting level height (Fig. 1a). This hypothesis is strongly supported by a 25-year sample of hailpad observations from southern France42 and a 29-year sample of hailpad observations from northeast Italy43.

Another important aspect of vertical thermodynamic structure for hailstorms is the mid-level lapse rate (Γ), measured here between 700 and 500 hPa (°C km−1), which serves as a proxy for layer static stability. Lapse rates that approach dry adiabatic (i.e., dθ/dz ≈ 0) in this layer typically suggest the presence of an elevated mixed-layer (EML), which has been trending stronger and more frequent across the High Plains in recent decades44. This has opposing implications for hailstorms, as steeper lapse rates favor large hail, but air that is too warm and dry at the base of the EML can inhibit convection initiation and sustenance (i.e., convective inhibition; CIN). Annual mean days with steep (i.e., ≥7.5 °C km−1) mid-level lapse rates are projected to increase by MID across a large swath of the central United States. (Supplementary Fig. A4a–e). The projected increase in days has greater dependence on the emissions pathway versus the time horizon. The Southeast, Mid-Atlantic, and Northeast U.S. portrayed either no change or slight decreases in steep lapse rate days depending on time horizon and emissions pathway. While regional change was evident, the domain-averaged annual mean mid-level lapse rate shows a only a slight decreasing trend (Supplementary Fig. A4f). A mean domain-averaged increase of 3 J kg−1 of the most unstable (MU) CIN is projected by END (not shown).

Next, we analyze water vapor mixing ratio (w; g kg−1), which is the primary source of energy (via latent heat release) for hailstorms. We examine w for a MU parcel as this measurement is also used in the calculation of SHIP. As expected due to increasing temperatures, widespread increases in w are noted, with both emissions scenarios averaging close to a 0.6 g kg−1 increase by MID (Supplementary Fig. A5a–e). Divergence also occurs for w projections by the end of the MID period, with nearly a 2 g kg−1 increase expected by the END period relative to HIST for the RCP 8.5 pathway (Supplementary Fig. A5f). One area of interest is in the central High Plains, where projected increases in w display a relative minimum. This suggests rising aridity given the expected increases in local temperatures, which is a relatively well-studied aspect of U.S. regional climate45,46,47. A related analysis (not shown) to diagnose changes in potential energy for convection using MU convective available potential energy showed similar results to w.

Sufficient deep-layer wind shear is necessary for organized convection to form, favoring morphologies that promote hail formation48. We examine this important ingredient by using the HIST climatology and future projections of days with deep-layer (0–6 km) bulk wind shear ≥18 m s−1 following previous work49. These can be thought of as adequate deep-layer wind shear days for organized convection, such as supercells33. In general, a median grid point decrease between 10 and 15 days was projected for MID45, MID85, and END45 (Supplementary Fig. A6a–d). END85 was a notable departure from the other three experiments, with a median decrease across the domain of ≈21 days (Supplementary Fig. A6e). MID85 was unique in that a more regional increase in days was found across the western Great Lakes and mid-upper Mississippi Valley (Supplementary Fig. A6c). The greater inter-experiment variability for deep-layer bulk shear is not surprising given its sensitivity to the synoptic circulation patterns. Overall, the broader picture foretells a reduction in mean annual deep-layer wind shear across the domain by 1–2 m s−1 by end of century (Supplementary Fig. A6f).

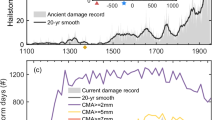

We conclude by examining the significant hail parameter (SHIP;50), a dimensionless composite parameter that measures juxtaposition of hail-favorable environmental ingredients51,52. A HIST climatology of SHIP ≥1 days (value of 1 is ≈ the HIST 90th percentile) shows the well-known distribution (and biases) of significant hail environments across the U.S. (Fig. 5a). Projected changes in SHIP ≥1 days reveals the importance of examining all ingredients together (Fig. 5b–e). For example, increases in moisture, convective instability, and mid-level lapse rate are not sufficient to offset decreases in deep-layer vertical wind shear and increased melting levels in most areas across the High Plains. This leads to a regional 2–5 day decrease in SHIP ≥1 days in all four experiments. Conversely, in areas like the Mid-South, decreases in both mid-level lapse rate and deep-layer vertical wind shear are opposed by increases in water vapor mixing ratio and convective instability, leading to an increase in days. A seasonal breakdown (not shown) indicates that the largest decreases in SHIP ≥1 days occur during JJA, with the largest increases recorded in MAM. This result is consistent with expected summary changes in severe convective storm environments as determined by the implicit environmental approaches21,22,53,54,55,56 and helps explain the spatial distributions we find in WRF-BCC.

WRF-BCC parent GCM representation of a HIST annual mean days with a SHIP value ≥1. b–e show the projected departure in days for each experiment. f is calculated using the domain-averaged annual accumulation of daily max SHIP. Years corresponding to WRF-BCC simulations are shaded in gray. Bold lines indicate the 10-year running mean.

Discussion

We find decreases in near-surface severe hail days over large swaths of the Great Plains, with most of the change projected during summer. These decreases were most notable for the end-of-century simulation under the most aggressive emissions pathway (RCP 8.5). Spatial changes in column-maximum severe hail days showed a more latitudinal response, with decreases along the Gulf Coast and Texas, and increases in the Mid-South, Midwest, and Northeast.

Study limitations include the use of only one pair of GCM/RCM members and a rather limited number of simulation years for each epoch due to computational expense. Ideally, a large ensemble of simulations should be examined with varying initial and lateral boundary conditions from a suite of GCMs forcing a multi-physics convection-permitting ensemble of RCMs for 30-year experiment periods. Finally, more realistic hail size climatologies (especially at the largest sizes) could be achieved by incorporating a more sophisticated microphysics scheme or physically-based hail forecast model (e.g., HAILCAST37).

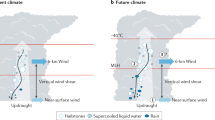

We conclude by summarizing the expected impacts of climate change on hailstorms from our experiments using a simple illustration (Fig. 6). A warmer future climate leads to an increased water vapor mixing ratio over most regions and subsequent energy for thunderstorm updrafts. Temperature decreases through the mid-level of the atmosphere steepen in the most hail-prone areas of the United States, a feature that favors stronger updrafts; however, this can also inhibit the development, as well as sustenance, of deep convection if the base of the EML becomes too warm. If deep convection does develop, mean updraft speeds are greater, and the largest stones are more frequent. As hailstones fall toward the surface, a greater depth of air >0 °C promotes increased melting and distributional shifts that favor larger hailstones. This has significant implications for impacts on lives and property. Finally, the authors remind readers that, regardless of the changes in hail size and frequency due to climatic shifts, we should expect to see continued increases in the societal impacts and losses associated with hailstorms due to increases in the footprint of the human-built environment4,57.

Schematic summary of a current and b future hailstorms. Red and blue arrows indicate the thunderstorm’s updraft and downdraft, respectively. b a warmer climate leads to (1) increased vapor mixing ratio, which serves as energy for thunderstorms. This leads to stronger updrafts (2), on average, and more large hailstones aloft. As hailstones begin their downward trajectory, they encounter a melting level height (3) that is expected to increase by at least 500 m by the end of the century. These processes ultimately result in fewer small hailstones reaching the surface, with a favored distribution toward larger hail sizes. A thunderstorm producing 5 cm hail near Roswell, New Mexico on 7 June 2014 is shown in the background photograph.

Methods

RCM experiments

Convection-permitting (Δx = 3.75 km; 51 vertical η levels; no cumulus parameterization) historical and future RCM simulations were created using the Advanced Research core of the Weather Research and Forecasting (WRF) Model version 4.1.258. Initial and lateral boundary conditions of atmospheric and oceanic state variables for WRF originate from 6-hourly interval output from the Community Earth System Model (CESM59) provided by NCAR that participated as a GCM in phase 5 of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP560). Herein, we use a version of these GCM data that are regridded and bias-corrected using 1981–2005 ERA-Interim reanalysis61 following previous work62. Bias correction of GCM data prior to input into a RCM improves overall simulation performance, especially for extremes63,64,65,66, and represented a critical element in the authors’ choice of GCM data for input into the RCM.

RCM output were generated for one historical (HIST; 1990–2005), two mid-century (MID; 2040–2055), and two end of century (END; 2085–2100) 15-year periods for a domain encompassing the conterminous U.S. For the MID and END epochs, Representative Concentration Pathway (RCP67) 8.5 and 4.5 were chosen to represent a pessimistic and intermediate anthropogenic emissions scenario, respectively. For each experiment epoch, 15 simulations (representing each year in the respective period, for a total 75 simulations) were continuously integrated across an entire hydrologic year (1 Oct–30 Sep), with a new initialization occurring every 1 Oct. This represents a middle ground approach between more frequent (i.e., daily) reinitialization28,31 and a continuous integration of the convection-permitting RCM over the 15-year period29 from previous work. In general, less frequent initialization is preferred in RCM applications to recreate conditions that require hydrologic memory68,69 due to their development over multiple days or months70. Our approach aimed to balance this consideration with the equally important issue of computational resources/efficiency (e.g., processing multiple years from a period in parallel). We direct readers to previous work that contains additional details of the RCM configuration, including verification results of the HIST period against observations38. These simulations are generically referred to as WRF-BCC (WRF-Bias-Corrected CESM) throughout this study. The five simulation experiments are labeled as HIST, MID45, MID85, END45, and END85.

Representation of hail in WRF-BCC

To assess changes in hail, we examined WRF-BCC output of the lowest model level maximum diameter hail diagnostic (hail_maxk1) and the column-maximum diameter hail diagnostic (hail_max2d) calculated at run-time from the Thompson microphysics scheme71,72. Hourly maximum values of hail_maxk1 and hail_max2d were captured at the top of each simulation hour for analysis, which represents the maximum value over the last hour of numerical integration (20 s interval). To ensure simulated hail values were originating from updrafts associated with convection, hail_maxk1 and hail_max2d were masked if the gridpoint did not also record a maximum vertical velocity value of 6 m s−1 over the same hour. We also restrict all analyses to areas east of the U.S. Rocky Mountains at WRF-BCC grid points with elevations ≤1830 m (≈6000 ft).

For this work, WRF simulated the maximum hail diameter using a modified gamma distribution of the Thompson scheme’s graupel class:

where N is the number of hailstones of diameter D. The intercept (No) and slope (λ) are predicted by representation of the underlying physical mechanisms causing increases or decreases in the hailstone sizes (e.g., melting, accretion). The shape parameter is held constant (μ = 1) and a spherical hailstone shape is assumed. Due to the continuous and potentially infinite nature of the gamma equation, hailstone diameters for this version of WRF are constrained to 50 bins related to physically observable hail sizes73. The maximum hailstone diameter is set to the upper limit bin size where the number concentration of hailstones last reaches a prescribed minimum threshold of 5 × 10−4 m−3, which translates to roughly one hailstone of that size per 160 m2. This threshold is corroborated by in-situ, high-density observations of hail74. The largest of the 50 spectral bulk bin sizes in WRF is constrained to 7.5 cm, which intrinsically caps the maximum size of WRF-BCC hail diameters. Thus, it should not be expected that simulated maximum hail diameters approach the largest values occasionally observed (e.g., 10+ cm75). Future simulations of this type may benefit, especially with respect to the largest hailstone sizes, from double-moment hail class microphysics scheme or an inline 1-D physically-based hail size forecasting module (e.g., HAILCAST37), both of which were determined to be too computationally expensive during generation of WRF-BCC.

Comparison to observations

It is challenging to fully assess the ability of WRF-BCC to capture the observed climatology of hail in the U.S. due to known issues with the official U.S. hail-reporting database76 and caveats associated with remotely sensing hail from active and passive remote sensing platforms77,78. While a comprehensive verification—akin to that performed for WRF-BCC temperature and precipitation38—is particularly difficult for hail, we attempt this important exercise by comparing WRF-BCC hail_maxk1 to observed reports and Doppler-radar detections of hail.

For observed hail reports, we follow previous work79 and use an archive maintained by NOAA’s National Weather Service Storm Prediction Center. The database includes reports of “severe" hail, which is defined in the U.S. as hail with a 2.54 cm or larger maximum dimension. Doppler-radar detections of hail stem from GridRad v3.180, which is a high-resolution, 3-D gridded radar dataset covering much of the contiguous U.S. derived from the National Weather Service’s Next Generation Weather Radar (NEXRAD) system. Specifically, we use GridRad’s 95th pecentile maximum estimated size of hail variable (MESH95).

1995–2017 (i.e., temporal coverage of GridRad v3.1) hail reports ≥2.54 cm (1 in), GridRad MESH95 detections calibrated to the “severe" threshold (≥6.33 cm; 2.49 in)78, and WRF-BCC hail_maxk1 ≥3.18 cm (1.25 in) from the HIST epoch were resampled in space and time to create gridded climatologies of 1200–1200 UTC hail days78 on a similar ≈1° × 1° latitude-longitude grid for comparison. We say similar grid because there are some slight differences in the WRF-BCC grid (both GridRad and reports were aggregated to an exact 1° × 1° latitude-longitude grid) due to its native 3.75 km horizontal grid spacing using a Lambert conformal conic projection. We used a 30× upscale regrid on the WRF-BCC for comparison, resulting in a 112.5 km (30 × 3.75 km) grid spacing, which is slightly larger than 1° × 1° across our domain. We chose a 1° × 1° grid for this analysis due to previous work that compared GridRad MESH95 to hail reports78, but the overall results were not sensitive to grid size (only the expected changes to magnitude values). HIST hail_maxk1 ≥3.18 cm was chosen as a threshold for defining “severe" hail days from WRF-BCC because it demonstrated the lowest gridpoint-to-closest-gridpoint root-mean-square error of those thresholds tested (1.91, 2.54, 3.18, 3.81 cm ∣ 0.75, 1.0, 1.25, 1.5 in) against severe (≥2.54 cm) hail days from reports. This is similar to the calibration analysis and threshold chosen for GridRad “severe" detections (MESH95 ≥6.33 cm) in previous work78.

Significance testing

Where indicated throughout the manuscript, statistical significance was calculated for annual distributions using a Mann–Whitney U test for the medians at the 95% significance level (p values ≤ 0.05). For Fig. A2, additional restriction of the p values was performed by implementing a field significance false discovery rate of α = 0.1.

Data availability

Hail report data are available for download via NOAA’s National Weather Service Storm Prediction Center (https://www.spc.noaa.gov/wcm/#data). GridRad data are available for download via NCAR’s Research Data Archive (https://rda.ucar.edu/datasets/ds841.1/). Bias-corrected CESM data used to force WRF-BCC are also available for download via NCAR’s Research Data Archive (https://rda.ucar.edu/datasets/ds316.1/). WRF-BCC data are currently being stored courtesy of Argonne National Laboratory. Interested collaborators should contact the corresponding author for access details.

References

Allen, J. T. et al. Understanding hail in the earth system. Rev. Geophys. 58, e2019RG000665 (2020).

Changnon, S. A. Increasing major hail losses in the us. Clim. Change 96, 161–166 (2009).

Smith, A. B. Us Billion-dollar weather and climate disasters, 1980-present. https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/billions/events.pdf (2024).

Ashley, W. S., Strader, S., Rosencrants, T. & Krmenec, A. J. Spatiotemporal changes in tornado hazard exposure: the case of the expanding bull’s-eye effect in Chicago, Illinois. Weather Clim. Soc. 6, 175–193 (2014).

Doswell, C. A., Brooks, H. E. & Maddox, R. A. Flash flood forecasting: an ingredients-based methodology. Weather Forecast. 11, 560–581 (1996).

Diffenbaugh, N. S., Scherer, M. & Trapp, R. J. Robust increases in severe thunderstorm environments in response to greenhouse forcing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 110, 16361–16366 (2013).

Gensini, V. A., Ramseyer, C. & Mote, T. L. Future convective environments using NARCCAP. Int. J. Climatol. 34, 1699–1705 (2014).

Seeley, J. T. & Romps, D. M. The effect of global warming on severe thunderstorms in the United States. J. Clim. 28, 2443–2458 (2015).

Lepore, C., Abernathey, R., Henderson, N., Allen, J. T. & Tippett, M. K. Future global convective environments in CMIP6 models. Earth’s. Future 9, e2021EF002277 (2021).

Edwards, R. & Thompson, R. L. Nationwide comparisons of hail size with wsr-88d vertically integrated liquid water and derived thermodynamic sounding data. Weather Forecast. 13, 277–285 (1998).

Johnson, A. W. & Sugden, K. E. Evaluation of sounding-derived thermodynamic and wind-related parameters associated with large hail events. E-J. Sev. Storms Meteorol. 9, 1–42 (2014).

Brimelow, J. C. & Reuter, G. W. Explicit forecasts of hail occurrence and expected hail size using the GEM–HAILCAST system with a rainfall filter. Weather Forecast. 24, 935–945 (2009).

Jewell, R. & Brimelow, J. Evaluation of Alberta hail growth model using severe hail proximity soundings from the United States. Weather Forecast. 24, 1592–1609 (2009).

Gensini, V. A., Converse, C., Ashley, W. S. & Taszarek, M. Machine learning classification of significant tornadoes and hail in the United States using ERA5 proximity soundings. Weather Forecast. 36, 2143–2160 (2021).

Brimelow, J. C., Burrows, W. R. & Hanesiak, J. M. The changing hail threat over north america in response to anthropogenic climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 516–522 (2017).

Brimelow, J. C., Reuter, G. W. & Poolman, E. R. Modeling maximum hail size in Alberta thunderstorms. Weather Forecast. 17, 1048–1062 (2002).

Trapp, R. J. & Hoogewind, K. A. The realization of extreme tornadic storm events under future anthropogenic climate change. J. Clim. 29, 5251–5265 (2016).

Lasher-Trapp, S., Orendorf, S. A. & Trapp, R. J. Investigating a derecho in a future warmer climate. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 104, E1831–E1852 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Potential weakening of the June 2012 North American derecho under future warming conditions. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 128, e2022JD037494 (2023).

Mallinson, H., Lasher-Trapp, S., Trapp, J., Woods, M. & Orendorf, S. Hailfall in a possible future climate using a pseudo–global warming approach: Hail characteristics and mesoscale influences. J. Clim. 37, 527–549 (2024).

Allen, J. T. Climate change and severe thunderstorms. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228620.013.62 (2018).

Gensini, V. V. A. Severe convective storms in a changing climate. 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-822700-8.00007-X (2021).

Weisman, M. L., Skamarock, W. C. & Klemp, J. B. The resolution dependence of explicitly modeled convective systems. Mon. Weather Rev. 125, 527–548 (1997).

Trapp, R. J., Robinson, E. D., Baldwin, M. E., Diffenbaugh, N. S. & Schwedler, B. R. Regional climate of hazardous convective weather through high-resolution dynamical downscaling. Clim. Dyn. 37, 677–688 (2011).

Robinson, E. D., Trapp, R. J. & Baldwin, M. E. The geospatial and temporal distributions of severe thunderstorms from high-resolution dynamical downscaling. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 52, 2147–2161 (2013).

Gensini, V. A. & Mote, T. L. Estimations of hazardous convective weather in the United States using dynamical downscaling. J. Clim. 27, 6581–6589 (2014).

Gensini, V. A. & Mote, T. L. Downscaled estimates of late 21st century severe weather from CCSM3. Clim. Change 129, 307–321 (2015).

Hoogewind, K. A., Baldwin, M. E. & Trapp, R. J. The impact of climate change on hazardous convective weather in the United States: Insight from high-resolution dynamical downscaling. J. Clim. 30, 10081–10100 (2017).

Liu, C. et al. Continental-scale convection-permitting modeling of the current and future climate of North America. Clim. Dyn. 49, 71–95 (2017).

Prein, A. F. et al. Increased rainfall volume from future convective storms in the US. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 880–884 (2017).

Trapp, R. J., Hoogewind, K. A. & Lasher-Trapp, S. Future changes in hail occurrence in the united states determined through convection-permitting dynamical downscaling. J. Clim. 32, 5493–5509 (2019).

Haberlie, A. M., Ashley, W. S., Battisto, C. M. & Gensini, V. A. Thunderstorm activity under intermediate and extreme climate change scenarios. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL098779 (2022).

Ashley, W. S., Haberlie, A. M. & Gensini, V. A. The future of supercells in the United States. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 104, E1–E21 (2023).

Prein, A. F. et al. A review on regional convection-permitting climate modeling: demonstrations, prospects, and challenges. Rev. Geophys. 53, 323–361 (2015).

Raupach, T. H. et al. The effects of climate change on hailstorms. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 213–226 (2021).

Mahoney, K., Alexander, M., Scott, J. D. & Barsugli, J. High-resolution downscaled simulations of warm-season extreme precipitation events in the Colorado front range under past and future climates. J. Clim. 26, 8671–8689 (2013).

Adams-Selin, R. D. & Ziegler, C. L. Forecasting hail using a one-dimensional hail growth model within WRF. Mon. Weather Rev. 144, 4919–4939 (2016).

Gensini, V. A., Haberlie, A. M. & Ashley, W. S. Convection-permitting simulations of historical and possible future climate over the contiguous United States. Clim. Dyn. 60, 109–126 (2023).

Monaghan, A., Steinhoff, D., Bruyere, C. & Yates, D. NCAR CESM global bias-corrected CMIP5 output to support WRF/MPAS research. https://data.ucar.edu/dataset/ncar-cesm-global-bias-corrected-cmip5-output-to-support-wrf-mpas-research (2014).

Kumjian, M. R., Lombardo, K. & Loeffler, S. The evolution of hail production in simulated supercell storms. J. Atmos. Sci. 78, 3417–3440 (2021).

Prein, A. F. & Heymsfield, A. J. Increased melting level height impacts surface precipitation phase and intensity. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 771–776 (2020).

Dessens, J., Berthet, C. & Sanchez, J. Change in hailstone size distributions with an increase in the melting level height. Atmos. Res. 158, 245–253 (2015).

Manzato, A., Cicogna, A., Centore, M., Battistutta, P. & Trevisan, M. Hailstone characteristics in northeast italy from 29 years of hailpad data. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 61, 1779–1795 (2022).

Andrews, M. S. et al. Climatology of the elevated mixed layer over the contiguous United States and northern Mexico using ERA5: 1979–2021. J. Clim. 37, 1833–1851 (2024).

Hufkens, K. et al. Productivity of North American grasslands is increased under future climate scenarios despite rising aridity. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 710–714 (2016).

Modala, N. R. et al. Climate change projections for the Texas high plains and rolling plains. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 129, 263–280 (2017).

Seager, R. et al. Whither the 100th meridian? The once and future physical and human geography of America’s arid–humid divide. Part I: the story so far. Earth Interact. 22, 1–22 (2018).

Kumjian, M. R. & Lombardo, K. A hail growth trajectory model for exploring the environmental controls on hail size: Model physics and idealized tests. J. Atmos. Sci. 77, 2765–2791 (2020).

Gensini, V. A. & Ashley, W. S. Climatology of potentially severe convective environments from the North American regional reanalysis. E-J. Sev. Storms Meteorol. 6, 1–40 (2011).

Tang, B. H., Gensini, V. A. & Homeyer, C. R. Trends in United States large hail environments and observations. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2, 45 (2019).

Púčik, T. et al. Future changes in european severe convection environments in a regional climate model ensemble. J. Clim. 30, 6771–6794 (2017).

Rädler, A. T., Groenemeijer, P., Faust, E. & Sausen, R. Detecting severe weather trends using an additive regressive convective hazard model (ar-chamo). J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 57, 569–587 (2018).

Brooks, H. E. Severe thunderstorms and climate change. Atmos. Res. 123, 129–138 (2013).

Tippett, M. K., Allen, J. T., Gensini, V. A. & Brooks, H. E. Climate and hazardous convective weather. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 1, 60–73 (2015).

Rädler, A. T., Groenemeijer, P. H., Faust, E., Sausen, R. & Púčik, T. Frequency of severe thunderstorms across europe expected to increase in the 21st century due to rising instability. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2, 30 (2019).

Battaglioli, F. et al. Modeled multidecadal trends of lightning and (very) large hail in Europe and North America (1950–2021). J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 62, 1627–1653 (2023).

Childs, S. J., Schumacher, R. S. & Strader, S. M. Projecting end-of-century human exposure from tornadoes and severe hailstorms in eastern Colorado: meteorological and population perspectives. Weather Clim. Soc. 12, 575–595 (2020).

Skamarock, W. C. et al. A description of the advanced research WRF version 4. NCAR tech. note ncar/tn-556+ str, 145 (2019).

Hurrell, J. W. et al. The community earth system model: a framework for collaborative research. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 94, 1339–1360 (2013).

Taylor, K. E., Stouffer, R. J. & Meehl, G. A. An overview of CMIP5 and the experiment design. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 93, 485–498 (2012).

Dee, D. P. et al. The ERA-Interim reanalysis: configuration and performance of the data assimilation system. Q.J.R. Meteorol. Soc. 137, 553–597 (2011).

Bruyère, C. L., Done, J. M., Holland, G. J. & Fredrick, S. Bias corrections of global models for regional climate simulations of high-impact weather. Clim. Dyn. 43, 1847–1856 (2014).

Wu, W., Lynch, A. H. & Rivers, A. Estimating the uncertainty in a regional climate model related to initial and lateral boundary conditions. J. Clim. 18, 917–933 (2005).

Ines, A. V. & Hansen, J. W. Bias correction of daily GCM rainfall for crop simulation studies. Agric. For. Meteorol. 138, 44–53 (2006).

Christensen, J. H., Boberg, F., Christensen, O. B. & Lucas-Picher, P. On the need for bias correction of regional climate change projections of temperature and precipitation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GL035694 (2008).

Kim, Y., Rocheta, E., Evans, J. P. & Sharma, A. Impact of bias correction of regional climate model boundary conditions on the simulation of precipitation extremes. Clim. Dyn. 55, 3507–3526 (2020).

Moss, R. H. et al. The next generation of scenarios for climate change research and assessment. Nature 463, 747–756 (2010).

Giorgi, F. & Mearns, L. O. Introduction to special section: regional climate modeling revisited. J. Geophys. Res. 104, 6335–6352 (1999).

Chen, J. & Kumar, P. Role of terrestrial hydrologic memory in modulating ENSO impacts in North America. J. Clim. 15, 3569–3585 (2002).

Christian, J., Christian, K. & Basara, J. B. Drought and pluvial dipole events within the Great Plains of the United States. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 54, 1886–1898 (2015).

Thompson, G., Field, P. R., Rasmussen, R. M. & Hall, W. D. Explicit forecasts of winter precipitation using an improved bulk microphysics scheme. Part II: implementation of a new snow parameterization. Mon.Weather Rev. 136, 5095–5115 (2008).

Thompson, G. & Eidhammer, T. A study of aerosol impacts on clouds and precipitation development in a large winter cyclone. J. Atmos. Sci. 71, 3636–3658 (2014).

Milbrandt, J. & Yau, M. A multimoment bulk microphysics parameterization. Part IV: sensitivity experiments. J. Atmos. Sci. 63, 3137–3159 (2006).

Blair, S. F. et al. High-resolution hail observations: implications for NWS warning operations. Weather Forecast. 32, 1101–1119 (2017).

Kumjian, M. R. et al. Gargantuan hail. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 102, 117–123 (2021).

Allen, J. T. & Tippett, M. K. The characteristics of United States hail reports: 1955-2014. E-J. Sev. Storms Meteorol. 10, 1–31 (2015).

Cecil, D. J. & Blankenship, C. B. Toward a global climatology of severe hailstorms as estimated by satellite passive microwave imagers. J. Clim. 25, 687–703 (2012).

Murillo, E. M., Homeyer, C. R. & Allen, J. T. A 23-year severe hail climatology using GridRad MESH observations. Mon. Weather Rev. 149, 945–958 (2021).

Gensini, V. A., Haberlie, A. M. & Marsh, P. T. Practically perfect hindcasts of severe convective storms. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 101, E1259–E1278 (2020).

Bowman, K. P. & Homeyer, C. R. Gridrad - three-dimensional gridded nexrad wsr-88d radar data. https://doi.org/10.5065/D6NK3CR7 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge high-performance computing support from Cheyenne (doi:10.5065/D6RX99HX) provided by NCAR’s Computational and Information Systems Laboratory, sponsored by the National Science Foundation. This research also used resources of the Argonne Leadership Computing Facility, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science user facility at Argonne National Laboratory, and is based on research supported by the U.S. DOE Office of Science-Advanced Scientific Computing Research Program, under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. MID simulations were performed using the Comet supercomputer, which is hosted by the San Diego Supercomputer Center at the University of California, San Diego. This computational resource was made available by the Atmospheric River Program (Phase 2 and 3), which is supported by the California Department of Water Resources (awards 4600013361 and 4600014294, respectively) and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Engineer Research and Development Center (award USACE W912HZ-15-2-0019). This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (award numbers 1637225, 1800582, 2048770, and 2203516).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

V.G. conceived the study, performed the analysis, created the figures, and led the initial draft of the manuscript. W.A. contributed to aspects of study design and helped lead the administration of the project. A.M. conducted WRF-BCC simulations for the MID epoch. A.H. helped process the data and contributed code for analysis. J.G. provided an early draft of the introduction for the manuscript. B.W. calculated the daily-maximum values from WRF-BCC. All authors contributed equally to reviewing and editing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gensini, V.A., Ashley, W.S., Michaelis, A.C. et al. Hailstone size dichotomy in a warming climate. npj Clim Atmos Sci 7, 185 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00728-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00728-9

This article is cited by

-

Contrasting trends in very large hail events and related economic losses across the globe

Nature Geoscience (2026)

-

Why do hailstones get so big? Scientists are chasing storms to find answers

Nature (2025)

-

On the relationship between monthly mean surface temperature and tornado days in the United States

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)