Abstract

Long-lasting La Niña events (including double-year and triple-year La Niña events) have become more frequent in recent years. How the multi-year La Niña events affect tropical cyclone (TC) activities in the western North Pacific (WNP) and whether they differ from single-year La Niña events are unknown. Here we show that TCs are more active over the far-WNP (FWNP, 110°–150°E), leading to marked high risks at China coasts during the second decaying summer of double-year La Niña events. The anomalous TC activities are directly related to the enhanced cyclonic anomaly over the FWNP, possibly a result of large-scale remote forcing initiated by the tropical North Atlantic (TNA) cooling. The persistent TNA cooling from the decaying winter to summer of double-year La Niña events drives westerlies over the Indo-western Pacific through Kelvin waves, which induce the cooling over the north Indian Ocean via the wind-evaporation-sea surface temperature effect, favoring the asymmetric heat distribution pattern and stimulating an anomalous vertical circulation over the eastern Indian Ocean to FWNP. The cooling over the north Indian Ocean also excites Gill responses, magnifying the TNA-induced westerlies and boosting the anomalous vertical circulation, and thus gives rise to the strong cyclonic circulation anomaly over the FWNP in summer. We suggest that the key point of the process is the strong TNA cooling related to the persistent negative Pacific-North American pattern (PNA) and positive North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) while double-year La Niña events decay, distinct from the rapid decline of PNA and NAO during single-year La Niña events. The work provides a unique perspective on understanding TC activities over the WNP related to the El Niño-Southern Oscillation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As one of the most destructive weather events in coastal areas, tropical cyclone (TC) activity is attracting increasing attention among climate and socioeconomic scientists. The western North Pacific (WNP) is the most active region for TC geneses, with about half or more of WNP TCs making landfall along the East Asia coast1.TC activities over the WNP, including genesis, intensity, and landfalls, are strongly modulated by El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO)2,3,4,5,6,7, which typically recurs every 2-7 years and lasts around 1-2 years8. ENSO can be categorized into single-year and multi-year (including double-year or triple-year so far) El Niño/La Niña according to its persistence9,10. Multi-year ENSO events are distinct from single-year events in terms of onset and decay11,12,13, as well as contributions to extreme weather events14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21, including severe cold winter in the northwestern North America14, heavy drought in the southern United States15,20, active hurricanes in the North Atlantic16 and unprecedented heatwaves in the Yangtze River Valley17.

Moreover, the previous studies about the duration of ENSO events22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29 primarily focused on the potential mechanisms leading to the different evolution of ENSO events. However, there remains a paucity of research examining the response of extreme weather events to multi-year ENSO events. ENSO events are often treated as separated single-year events regarding their influence on TC activities30,31,32,33. Latest findings show that multi-year La Niña events have become prominent in recent decades29 and may occur more frequently in the future34. With more TCs formed over the northwestern quadrant of the WNP during La Niña events due to the enhanced Walker circulation2,6, the risks of TC hazards along the South China coast have escalated35. Previous studies about the atmospheric response to sea surface temperature (SST) anomaly during multi-year La Niña events are mainly related to the anomalies in precipitations20,36,37 and air temperature18,21,38. To the best of our knowledge, the impact of multi-year La Niña events on the WNP TC activities has not been investigated before. Therefore, comprehensive studies about the influence of multi-year La Niña events on the WNP TCs become pressing, including how TCs change and what physical mechanisms are involved in during multi-year La Niña events.

Here we use observations and numerical model to analyze the TC activities over the WNP during single- and multi-year La Niña events. Our results reveal that the coasts of China are exposed to more risks of WNP TCs during the decaying summer of multi-year La Niña events, especially in double-year La Niña events, compared to that during single-year La Niña events (Fig. 1). Why are TC activities unusual during the decaying summer of double-year La Niña events? What environmental factors play a key role in the significant differences? And what are the fundamental reasons? Addressing these questions can enhance our understanding of the effects of ENSO on the TC activities.

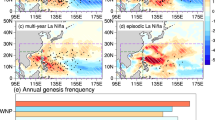

The difference of western North Pacific (WNP) TC track density (shading) and steering flow anomaly (vector; units: m/s) in decaying summer between single- and double-year La Niña events (double-year decaying summer [JJA(2)] minus single-year decaying summer [JJA(1)]). Red (black) contour line indicates the 5870 geopotential meter in the decaying summer of double-year (single-year) La Niña events, respectively. Black crosses and green vectors represent respectively the TC track density anomaly and steering flow anomalies being above the 95% confidence level based on Student’s t test.

Results

More TC activities along the China coasts during the second decaying summer of double-year La Niña events

There are 16 La Niña events during 1950–2023, including 7 single-year La Niña events and 9 multi-year La Niña events (5 double-year and 4 triple-year La Niña events; Supplementary Figs. 1, 2, and Supplementary Table 1). The year after the onset of a La Niña event is denoted as the decaying year. For example, a double-year La Niña event has two decaying years. In this study, we investigate TC activities over the WNP during the last decaying year of La Niña events (hereafter referred to as the decaying year/seasons, unless otherwise specified).

Among the single-, double- and triple-year La Niña events, the anomalous TC activities over the WNP are more prominent in the decaying summer (June-July-August, JJA) of double-year La Niña events (Fig. 1, Supplementary Figs. 3–5 and Supplementary Table 2). Compared to that during single-year La Niña events, WNP TC activities (represented by TC track density) during the decaying summer of double-year La Niñas feature a significant dipole structure over the far-WNP (FWNP, 110°–150°E), i.e., active over the region of 18°–40°N and 110°–130°E and inactive over the area south to 18°N and 110°–150°E during the decaying summer of double-year La Niñas.

The western Pacific subtropical high during double-year La Niña events is more eastward than that during single-year La Niña events, suggesting less suppression on the convection over the FWNP (Fig. 1). Weaker vertical wind shear, stronger upward motion, positive 850 hPa relative vorticity anomaly and moist middle-level atmosphere over the FWNP during the decaying summer of double-year La Niña events all favor TC activities in the area (Fig. 2). Consequently, WNP TC geneses are located more northwestward than that during single-year La Niñas, contributing to a dipole pattern of the TC track density anomaly (Supplementary Text). Moreover, predominant TC track direction also plays an important role in the anomalous TC track density pattern. Steering flow is the key factor controlling the movement of TCs and the most important reference for the TC landfall location39. In contrast to the conditions observed during single-year La Niña events, steering flow (vertically integrated horizontal wind from 850 hPa to 300 hPa) during the decaying summer of double-year La Niña events exhibits an anomalous cyclonic circulation over the FWNP (Fig. 1), with easterly anomaly at its north, which favors TCs moving westward and influencing both the eastern and southern China coasts. As a result, coastal regions of China (~200 km in the ocean) face higher risks from TC influences (Fig. 1). Observation records indicate that 60.5% (46/76: ratio of the number of TCs affecting China to the number of total TCs in the WNP) of the WNP TCs affect China coasts during the decaying summer of double-year La Niña events, 15% higher than that during single-year La Niñas (around 45.5%; 50/110). To sum up, the pronounced difference in WNP TC activities between double- and single-year La Niña events is mainly located over the FWNP.

The composite difference of (a) vertical wind shear (units: m/s), (b) 500 hPa omega (negative value represents upward motion; units: Pa/s), (c) 850 hPa relative vorticity (units: s−1), and (d) 600 hPa relative humidity (units: %) between single- and double-year La Niña events. Gray dots indicate the difference above the 95% confidence level based on Student’s t test.

Local sea surface temperature effect

Local air-sea interaction is generally regarded as a key process affecting TC activities by modulating local convection through direct SST heating/cooling of the atmosphere above. Here we show the prominent atmospheric circulation anomaly during the decaying summer of double-year La Niña events and illustrate that the anomalous cyclonic circulation over the FWNP is unlikely caused by local SST effects.

The evolution of SST anomaly and 850 hPa horizontal wind anomaly displays that the strong meridional SST anomaly gradient over the tropical oceans and the atmospheric circulation anomalies, including the North Pacific High, the westerly anomaly over the tropical FWNP and easterly over the eastern tropical Pacific, during the peak of La Niña events, gradually weakens after January-February-March [JFM(2)] for double-year (Fig. 3a–c)/[JFM(1)] for single-year (Supplementary Fig. 6). Hereafter, (1) and (2) refer to the decaying year of single and double-year La Niñas, respectively (see Methods). Compared to that during single-year La Niña events, the anomalous North Pacific High during double-year La Niña events is more southeastward, inducing a wider cooling band from north subtropic to tropic via wind-evaporation-SST (WES) feedback40,41. Meanwhile, westerly wind anomalies emerge from the eastern Indian Ocean (EIO) to FWNP, converging with the easterly anomaly that occurs from the equatorial central Pacific (Fig. 3). As a result, a weak cyclonic circulation and surface warming anomaly form over the Philippine Sea. With the double-year La Niña events further decaying, both the westerly anomaly from the EIO to FWNP and the warming over the Philippine Sea gradually diminish till March-April-May [MAM(2)]. Different from the continuous weakening of the SST anomaly gradient and atmospheric circulation anomalies over the mid-latitude Pacific during the decaying year of the single-year La Niña events (Supplementary Fig. 6d–e), the westerly anomaly at the tropical FWNP and the cyclonic anomaly to the north reinforces again with enhanced cooling from the EIO to FWNP since April-May-June [AMJ(2)] of the double-year La Niña events (Fig. 3d–e). As the SST cooling over the FWNP reaches its peak in JJA(2), the anomalous cyclonic circulation also gains its maximum intensity (Fig. 3f). Because SST cooling tends to increase atmospheric stability and inhibit low-level convergence, it is unlikely that this enhanced cyclonic anomaly over the FWNP during JJA(2) is attributed to local SST feedback (Fig. 3f). Positive convection phase of intraseasonal oscillation can also increase local cyclonic circulation, however, we find that it plays an insignificant role in the formation of the cyclonic circulation over the FWNP (Supplementary Fig. 7).

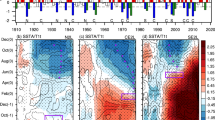

(a–f) The evolution of SST anomaly (units: oC) and 850hPa horizontal wind anomaly (units: m/s) from the winter (JFM(2), January-February-March) to summer [JJA(2)] of double-year La Niña events. g The evolution of NAO, PNA and SSTA over the TNA (tropical North Atlantic, 60°W–0°, 0°–25°N) from MJJ (May-June-July) in the first decaying year [MJJ(1)] to JAS (July-August-September) in the second decaying year [JAS(2)] of double-year La Niña events. Gray dots and black vectors in (a)–(f) indicate the anomaly above the 95% confidence level based on Student’s t test. The wind anomaly less than 0.5 m/s is omitted. The blue and red dotted lines in (g) represent the double standard deviation of 3-month running-mean filtered NAO and PNA index, respectively.

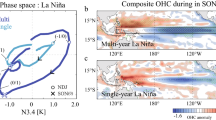

Importantly, Fig. 3 shows that the tropical North Atlantic (TNA) SST cools during the decaying year of double-year La Niña events, which is consistent with previous studies20,36. The cold SST anomalies over the TNA develop along the west coast of Africa during JFM(2), peak in MAM(2), and persist till JJA(2), which is distinctive from single-year La Niña events (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 6). Meanwhile, anomalous Azores High dominates the TNA, contributing to ocean cooling by enhancing the northeasterly trade wind through WES feedback. Large-scale SST cooling over the Pacific to Atlantic alters the vertical atmospheric circulation, shifting the upward branch eastward to the western Pacific and the downward branch to the Atlantic-Indian Ocean (Fig. 4a–c). The high-level convergence (represented by 200 hPa velocity potential anomaly) continuously enhances over the tropical Indian Ocean since MAM(2). Correspondingly, the high-level divergence over the western-central Pacific re-intensifies (Fig. 4). The high-level convergence (divergence) over the EIO (the FWNP) reaches its maximum in JJA(2), forming a large velocity potential gradient around 120°E, with reduced (increased) precipitation anomaly over the EIO (the FWNP) (Fig. 4). For the single-year La Niña events, the enhanced Azores High is absent throughout the decaying phase (Supplementary Fig. 6), accounting for the insignificant SST anomaly over the TNA. The area from the Indian Ocean to WNP is also dominated by the divergence anomalies but with much weaker strength in JJA(1) of the single-year La Niña events (Supplementary Fig. 8).

(a–f) The 200 hPa velocity potential anomaly (contours, unit: 105 m2/s) and precipitation anomaly (shading, unit: mm) from JFM(2) to JJA(2) of double-year La Niña events. Gray dots indicate the precipitation anomaly above the 95% confidence level based on Student’s t test. Blue dashed line and brown line represent respectively negative and positive 200 hPa velocity potential anomaly during the decaying year of double-year La Niña events. Negative velocity potential indicates low-level convergence.

In addition, composite analyses of 17 double-year La Niña events identified from 200-year pre-industrial simulations of the Community Earth System Model Version 2 (CESM2) confirm the formation of the cyclonic circulation anomaly over the FWNP and persistent SST cooling over the TNA during the decaying summer of double-year La Niña events (Supplementary Fig. 9). Despite the vast distance between the Atlantic and FWNP, the Altantic SST anomalies have been considered as a key factor affecting the atmospheric circulation anomalies over the Indo-western Pacific42,43. In the next section, we present how the persistent TNA cooling plays a key role in modulating the anomalous circulation over the FWNP during the decaying year of double-year La Niña events.

Remote forcing from the Atlantic Ocean

As mentioned above, the anomalous Azores High and its resulting ocean surface cooling over the TNA persist as the double-year La Niña events decay. Meanwhile, the North Pacific High gradually weakens and shifts westward (Fig. 3). TNA cooling exhibits the most significant and persistent SST anomaly over the global oceans during the decaying year of double-year La Niña events, which excites a Gill response and influences the Indo-Pacific climate42,44,45,46,47. After removing the influence of ENSO effects, regression results of TNA SST anomaly against 850 hPa wind and mean tropospheric temperature (850–200 hPa) show that the anomalous westerly prevails from the EIO to tropical central Pacific and cold tropospheric temperature wedge extends eastward, suggesting the atmospheric response to the TNA cooling as Kelvin waves response46,48 (Supplementary Fig. 10a). The westerly anomaly induced by the Kelvin waves can propagate to the International Date Line42. As the response of the Rossby waves to the TNA cooling, a pair of anomalous low-level anticyclones (corresponding to cold tropospheric temperature anomaly centers) appear at each side of the equator, with the easterly anomaly along the equator over the eastern tropical Pacific to Atlantic (Supplementary Fig. 10a).

Furthermore, the westerly anomaly induced by the TNA cooling plays a significant role in the formation of the cyclonic anomaly in the FWNP49. The climatological southwesterly winds prevail the north Indian Ocean (NIO) during AMJ. Consequently, the remote-induced westerly anomaly in this region serves to enhance the local wind, thereby increasing the upward surface latent heat flux and amplifying the initial SST cooling in this area (Supplementary Fig. 11 and Supplementary Table 3a). The substantial cooling over the NIO since AMJ(2) can also excite westerly anomaly at its east and easterly at west. The two processes together lead to enhanced westerly anomalies over the tropical WNP. Westerly anomaly over the WNP weakens the northeasterly trades resulting in downward surface latent heat flux anomaly, which suppresses surface cooling over the tropical WNP (Supplementary Fig. 11). Besides, the low-level westerly anomaly and upper-level easterly anomaly over the EIO–FWNP induced by the TNA cooling magnify the initial anomalous vertical circulation over the EIO to FWNP. As a result, the velocity potential gradient between the EIO and FWNP also strengthens (Fig. 4), which is directly related to the heat distribution over the EIO to the FWNP. With the development of anomalous vertical circulation, heat continuously accumulates over the FWNP and decreases over the EIO, forming an asymmetric heat pattern, with heat source over the FWNP while heat sink over the EIO (Fig. 5). As the positive feedback develops further, convection over the FWNP is enhanced with strong cyclonic circulation and increased precipitation over the FWNP, while the descending motion at the west leads to the dryer climate over the EIO (Fig. 4). After removing the impact of ENSO, regression of SST anomaly over the TNA with 200 hPa wind and precipitation anomaly in JJA show the anomalous circulation pattern over the Indo-western Pacific (Supplementary Fig. 10b), which confirms the reliability of this physical mechanism. In summary, the negative SST anomaly over the TNA can induce a response in the atmospheric circulation over the Indo-WNP, leading to the anomalous cyclonic circulation over the FWNP.

(a–c) The anomaly of Q1(units: W m−2) and 850 hPa horizontal wind (units: m/s;) for AMJ (April-May-June), MJJ, and JJA in the second decaying year of double-year La Niña events, (d–f) as (a–c), but for Q2 and 200 hPa horizontal wind. Gray dots and green vectors indicate the anomalies above the 95% confidence level based on Student’s t test for Q1 and Q2, and for the winds, respectively.

To further confirm the mechanism of TNA cooling as a trigger to the westerly anomalies over the WNP, the Community Atmosphere Model (version 5, CAM5) is used to test the sensitivity of atmospheric response to the TNA SST anomaly (Supplementary Table 3b; see Methods). Adding observational SST anomaly over the TNA (−0.42 °C in MAM and −0.15 °C in JJA) to lower boundary condition (details can be seen in Supplementary Fig. 12), the CAM5 simulated atmospheric response is qualitatively consistent with observations, especially the westerly anomaly over the FWNP (Supplementary Fig. 13a, b). A continuous TNA cooling from MAM to JJA can ensure the persistent and strong westerly anomaly at the FWNP and an anomalous cyclonic circulation over the WNP (Supplementary Fig. 13c). By adding the cooling over the NIO during JJA (averaged SST anomaly over the NIO is −0.21 °C) in the prior experiment can evidently boost the westerly anomaly and cyclonic circulation over the WNP (Supplementary Fig. 13d).

What causes the SST cooling over the TNA?

It is evident that TNA cooling can influence the circulation anomaly over the FWNP during double-year La Niña events. However, what triggers this strong and enduring cold SST anomaly over the TNA? Is it a merely coincidence, or is it linked to a specific forcing mechanism? The cold SST anomaly over the TNA arises from a northeasterly anomaly associated with the intensified Azores High through the WES feedback. The variations in the strength of Azores High are strongly modulated by the teleconnection pattern, including the Pacific-North American pattern (PNA) and North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO)50. PNA and NAO are the important atmospheric patterns over the Northern Hemisphere, which prominently influence the large-scale circulation over the North Pacific, North America, and North Atlantic51,52. These two teleconncection pattern are closely related to ENSO53.

During La Niña winter, the Aleutian low usually weakens,which contributes to the negative phase of PNA54,55. Less transient eddies from the Pacific to the Atlantic, enhanced baroclinicity and strong stratospheric vortex under La Niña conditions all possibly lead to the positive phase of NAO55. Moreover, the NAO pattern may also vary with the types of La Niña events56,57. Both NAO and PNA show marked differences between single-year and double-year La Niña events, with strong negative PNA and positive NAO for double-year La Niña events but weak negative PNA and negative NAO for single-year La Niña events (Fig. 3g and Supplementary Fig. 6g). PNA is one of the most important atmospheric bridges that modulate the SST anomaly over the TNA during ENSO58. There is a strong correlation between NAO and TNA cooling, whereas the positive NAO phase leads the TNA cooling for at least 4 months during the decaying year of double-year La Niña events (Supplementary Fig. 14). Therefore, persistent negative PNA and positive NAO patterns maintain the anticyclonic circulation over the North Atlantic thus enhancing the Azores High, with strengthened northeasterly at its southeast cooling ocean surface over the TNA via the WES feedback (Fig. 3).

What is the underlying reason for the abnormally strong PNA and NAO patterns during the decaying year of double-year La Niña events? Compared to single-year La Niña events, the subtropical North Pacific is notably colder in the decaying year of double-year La Niña events (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 6). According to previous studies, SST anomaly over the subtropical North Pacific has been considered one of the most important causes for the occurrences of the multi-year ENSO events13,59. Atmospheric circulation may be more sensitive to broad tropical Pacific SST anomaly than that limited to the equator20. By comparing the regression results of SST cooling over the equatorial Pacific and subtropical North Pacific (Supplementary Fig. 15), we find that the subtropical North Pacific cooling is highly related to the anticyclonic circulation over the mid-latitude North Pacific and eastern North America. Combined with the influence of La Niña, the extended SST cooling over the Pacific can enhance the anticyclonic circulation anomalies over the North Pacific and North Atlantic thus strengthening the PNA and NAO pattern. Therefore, we suggest the active PNA and NAO pattern, as well as the TNA cooling most likely appear in double-year La Niña events rather than in single-year La Niña events.

Summaries and discussions

Figure 6 summarizes the findings of this study. There is a strong SST cooling over the subtropical North Pacific in double-year La Niña events, which favors the persistence of La Niña events13 and excites strong interaction between tropic and subtropics, resulting in the abnormal anticyclonic circulation over the North Pacific and Atlantic, thus enhancing negative PNA and positive NAO (Supplementary Fig. 15). This abnormal anticyclonic circulation over the North Atlantic leads to significant and enduring TNA cooling. Subsequently, it induces an eastward-propagating Kelvin wave in the tropical Indo-Pacific Ocean, which generates the westerly anomaly and strengthens the cyclonic circulation over the FWNP. Concurrently, the westerly anomaly associated with the Kelvin wave also cools the NIO, setting off an eastward Kelvin wave that moves towards the WNP. These two Kelvin wave related processes work together to intensify the westerly anomalies over the tropical FWNP, which drives the anomalous vertical circulation over the EIO–FWNP, leading to the strong cyclonic circulation anomaly over the FWNP. Finally, the risks of TCs along the coasts of China increase in response to the anomalous circulation pattern along with other favorable environmental conditions, such as mid-level humidity and vertical wind shear during the decaying summer of double-year La Niña events.

Northeasterly anomaly generated by enhanced Azores High since MAM (March-April-May) cools the TNA, which triggers Kelvin waves propagating eastward with westerlies penetrating in the western North Pacific (WNP). The enhanced westerlies intensify the upward latent heat flux over the eastern Indian Ocean, resulting in local cooling via WES feedback and downward latent heat flux over the FWNP (110°–150°E), favoring the asymmetric heat distribution pattern. Increased heat source over the FWNP and heat sink over the tropical Indian Ocean drives an anomalous vertical circulation. The cooling over the north Indian Ocean also excites a Gill response, magnifying the TNA-induced westerlies, which boosts anomalous vertical circulation and gives rise to a strong cyclonic circulation anomaly over the FWNP in JJA.

It is also worth mentioning that TC activity over the FWNP during the first decaying summer of double-year La Niña events is less active than the second decaying summer (Supplementary Fig. 3b). In the first decaying year, no anomalous cyclonic circulation forms over the FWNP, and the TNA cooling is much weaker (Figure not shown). More importantly, the Walker circulation is stronger in the first decaying summer with strong easterly anomaly over the equatorial western Pacific, which could suppress the westerly anomaly caused by the weak TNA cooling (Supplementary Fig. 16a). While in the second decaying year, the Walker circulation and related easterly anomaly weaken significantly (Supplementary Fig. 16b). As a result, the westerly winds related to the TNA cooling dominate at this stage, which drives the cyclonic circulation anomaly over the FWNP via the asymmetric heat distribution, leading to more landfalling TCs along the coasts of China. The difference in the Walker circulation anomaly between the first and second decaying summer of double-year La Niña events is well captured by the climate models (Supplementary Fig. 16c, d).

The influence of double-year El Niño events shows an insignificant difference in the WNP TCs compared to that during single-year El Niño events (Supplementary Fig. 17), and the atmospheric environmental factors overall unfavor TC activities over the FWNP during double-year El Niño events (Supplementary Fig. 18). Besides, the pattern of WNP TC activities during the decaying summer of triple-year La Niña is also different from that during double-year La Niña events (Supplementary Fig. 3a). The underlying mechanism related to the differences may involve the asymmetric response of atmospheric circulation to the El Niño and La Niña events and their different decaying ways. Previous studies also noticed that there is anomalous SST over the tropical Atlantic during the decaying year of La Niña events60 and suggested that it play an important role in the transition of ENSO phases61,62. Further investigation is needed to understand the role of the SST anomaly pattern over the tropical Atlantic in influencing atmospheric circulation changes over the WNP. This will contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the key factors that control TC activities during various phases of ENSO events.

As global climate warms, the frequency of extreme La Niña events is expected to increase15. Furthermore, the northward expansion of easterly anomalies over the subtropical North Pacific, driven by warming in the equatorial eastern Pacific, could lead to more frequent occurrences of multi-year La Niña events in the future34, This can result in significant changes in TC activities. Therefore, high-resolution climate models incorporating future scenarios are essential to investigate the relationship between WNP TC activities and multi-year ENSO events. This study could contribute to enhancing the prediction of WNP TC activities and the associated threats to coastal regions.

Methods

The observational datasets

The best-track dataset from the China Meteorological Administration tropical cyclone database (CMA)63,64 is used in this study. The TC dataset includes 6-hourly TC positions (including UTC 00, 06, 12, 18), maximum wind speed, and minimum center pressure from 1949–2023. TCs with 2-min maximum sustained speed above 10.8 m/s and lifetime above 48 h are considered in this study. Monthly atmospheric and oceanic data with a horizontal resolution of 1° × 1° are downloaded directly from the official website of the fifth-generation European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) Re-Analysis (ERA5)65,66, including horizontal wind, relative humidity, vertical velocity, geopotential height, temperature, and surface latent heat flux. Hourly averaged potential temperature, horizontal wind, vertical velocity, and special humidity with a horizontal resolution of 1° × 1° are from the ERA5 dataset67. The global monthly precipitation anomaly data is derived from the Precipitation Reconstruction (PREC) at the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The anomalies of atmospheric and oceanic variables in the study are derived by removing the climatological mean (average during the period of 1951 to 2010) from the original data after linearly detrended. The Niño3.4 index, PNA index, and NAO index during 1950–2023 are obtained from the NOAA Climate Prediction Center (CPC).

The definition of multi-year and single-year La Niña events

Before distinguishing the multi-year and single-year La Niña events, the Niño 3.4 index is linearly detrended and smoothed with a 3-month running-mean filter similar to previous studies9,23. The first year/season when La Niña develops was denoted as year/season (0), and the following year/season as year/season (1), year/season (2), and so on. La Niña event begins to develop when the 3-month running-mean filtered Niño 3.4 index is smaller than −0.5 standard deviations in any month during November (0) to January (1). The standard deviations are calculated for each month during November to January. A multi-year La Niña event occurs if the Niño 3.4 index remains negative and smaller than −0.5 standard deviations for any month during November (1) to January (2). According to these criteria, there are 9 multi-year La Niña events and 7 single-year La Niña events. To carefully analyze the impact of the duration of La Niña events to the TC activities, the La Niña events during 1950–2023 are categorized into single-year, double-year and triple-year La Niña events based on the duration.

The TC activities

The track density of TCs over the WNP is interpolated by horizontal resolution of 2° × 2° and smoothed using the following method: D(x, y)= (D(x, y)+D(x−1, y)+D(x + 1, y)+D(x, y + 1) + D(x, y−1) + D(x−1, y−1) + D(x−1, y + 1) + D(x + 1, y−1) + D(x + 1, y + 1))/9, the subscripts x and y represent the longitude and latitude, respectively. The steering flow is defined by the vertical integral of horizontal wind from 850 hPa to 300 hPa.

The partial regression

Partial regression is employed to remove possible influences of ENSO on the relationship between SST anomaly over the TNA (60°W–0°, 0°–25°N) and atmospheric circulation. First, we calculate the linear relationship between the Niño 3.4 index and other variables, such as TNA SST and atmospheric wind anomalies. Subsequently, we remove the associated coherent variances from the original variables. The residual TNA SST anomaly and atmospheric anomalies are then linearly regressed to reveal the relationship between TNA SST and atmospheric circulation without ENSO effects involved. Details about this technique can be found in Cai et al. (2011)68.

Apparent heat source and apparent moisture sink

According to Yanai et al., (1973; 1992)69,70, the apparent heat source Q1 and the apparent moisture sink Q2 are defined by the following equations:

In the aforementioned equations, \(\theta\) is the potential temperature, \(q\) is the mixing ratio of water vapor, \(V\) is the horizontal wind, \(\omega\) is the vertical velocity, \(p\) is the pressure, \({p}_{0}\) = 1000 hPa, \({C}_{p}\) is the specific heat at a constant pressure of dry air, R is the gas constant, \(\kappa =R/{C}_{p}\), \(L\) is the latent heat of condensation. \(\nabla\) is the isobaric gradient operator and \(t\) is temporal resolution. Integrating Q1 and Q2 from tropopause pressure (100 hPa, \({P}_{T}\)) to surface pressure (\({P}_{s}\)), we can obtain \(\left\langle {Q}_{1}\right\rangle\) and \(\left\langle {Q}_{2}\right\rangle\).

Where \({Q}_{R}\) is the radiative heating rate per unit mass of air. P, S, and E are the precipitation rate, the sensible heat flux, and the evaporation rate per unit area at the surface, respectively. Angle brackets represent the integrated result from tropopause pressure (100 hPa,\(\,{P}_{T}\)) to surface pressure (\({P}_{s})\).

Sensitive experiments of CAM5

We use the Community Atmosphere Model version 5.0 (CAM5)71 to examine the impact of SST anomaly on anomalous atmospheric circulation over the FWNP. CAM5 is the atmospheric component of the National Center for Atmospheric Research Community Earth System Model, which has a horizontal resolution of 1.25° × 0.9° and 26 vertical levels. In the control run, the climatological (1982–2001) monthly SST data from the Hadley Centre Sea Ice and Sea Surface Temperature data set (HadISST)72 (the resolution is 1° × 1°) is used as the lower boundary condition to drive the model run. Then, we add SST anomaly over the TNA and the NIO (60°−100°E, 10°–25°N) to examine the response of atmospheric circulation (details about sensitivity experiments are shown in Supplementary Information).

The 200-yr pre-industrial simulations of the CESM2

The long-term (200-yr) pre-industrial simulated atmospheric and oceanic variables from the Community Earth System Model Version 2 (CESM2)73 are used for expanding the sample size of multi-year La Niña events. The Niño3.4 index is calculated by normalized SST anomaly averaged over the equatorial central-eastern Pacific (170°W–120°W, 5°S–5°N).

Data availability

The authors acknowledge the following data providers: CMA TC dataset (https://tcdata.typhoon.org.cn), ERA5 (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/cdsapp#!/dataset/reanalysis-era5-pressure-levels?tab=overview), PREC (https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.prec.html). CPC (https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/monitoring_and_data/oadata.shtml). CESM2 (https://data.ceda.ac.uk/badc/cmip6/data/CMIP6/CMIP/NCAR/CESM2/piControl/r1i1p1f1). HadISST (https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadisst/).

Code availability

All the codes used for the analysis are available from X.L. upon request (email: luoxi920@126.com).

References

Chan, J. C. L. Frequency and intensity of landfalling tropical cyclones in East Asia: past variations and future projections. Meteorology 2, 171–190 (2023).

Chan, J. C. L. Tropical cyclone activity over the Western North Pacific associated with El Niño and La Niña Events. J. Clim. 13, 2960–2972 (2000).

Camargo, S. J., Emanuel, K. A. & Sobel, A. H. Use of a genesis potential index to diagnose ENSO effects on tropical cyclone genesis. J. Clim. 20, 4819–4834 (2007).

Camargo, S. J., Robertson, A. W., Gaffney, S. J., Smyth, P. & Ghil, M. Cluster analysis of typhoon tracks. Part II: large-scale circulation and ENSO. J. Clim. 20, 3654–3676 (2007).

Camargo, S. J. & Sobel, A. H. Western North Pacific tropical cyclone intensity and ENSO. J. Clim. 18, 2996–3006 (2005).

Wang, B. & Chan, J. C. L. How strong ENSO events affect tropical storm activity over the Western North Pacific. J. Clim. 15, 1643–1658 (2002).

Wang, X., Zhou, W., Li, C. & Wang, D. Comparison of the impact of two types of El Niño on tropical cyclone genesis over the South China Sea: comparison of impact of two types of El Niño on tropical cyclone. Int. J. Climatol. 34, 2651–2660 (2014).

McPhaden, M. J., Zebiak, S. E. & Glantz, M. H. ENSO as an integrating concept in Earth science. Science 314, 1740–1745 (2006).

Wu, X., Okumura, Y. M. & DiNezio, P. N. What controls the duration of El Niño and La Niña events? J. Clim. 32, 5941–5965 (2019).

Okumura, Y. M. & Deser, C. Asymmetry in the duration of El Niño and La Niña. J. Clim. 23, 5826–5843 (2010).

Hu, Z.-Z., Kumar, A., Xue, Y. & Jha, B. Why were some La Niñas followed by another La Niña? Clim. Dyn. 42, 1029–1042 (2014).

Iwakiri, T. & Watanabe, M. Mechanisms linking multi-year La Niña with preceding strong El Niño. Sci. Rep. 11, 17465 (2021).

Kim, J.-W. & Yu, J.-Y. Single- and multi-year ENSO events controlled by pantropical climate interactions. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 5, 88 (2022).

Nishihira, G. & Sugimoto, S. Severe cold winters in East Asia linked to first winter of La Niña Events and in North America linked to second winter. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2021GL095334 (2022).

Cai, W. et al. Increased frequency of extreme La Niña events under greenhouse warming. Nat. Clim. Change 5, 132–137 (2015).

Lawrimore, J. H. et al. Climate assessment for 2000. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 82, S1–S56 (2001).

Tang, S. et al. Linkages of unprecedented 2022 Yangtze River Valley heatwaves to Pakistan flood and triple-dip La Niña. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 44 (2023).

Iwakiri, T. & Watanabe, M. Multiyear La Niña impact on summer temperature over Japan. J. Meteorological Soc. Jpn. 98, 1245–1260 (2020).

Zhong, W. et al. Heavy Southern China Spring Rainfall promoted by multi‐year El Niño events. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL102346 (2023).

Okumura, Y. M., DiNezio, P. & Deser, C. Evolving impacts of multiyear La Ni¤a events on atmospheric circulation and U.S. drought. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 11614–11623 (2017).

Yeo, S.-R. & Kim, S. T. Summer climate variability over Korea in association with diverse features of ENSO evolution. Clim. Dyn. 56, 2823–2838 (2021).

Liu, F. et al. New insights into multiyear La Niña dynamics from the perspective of a near-annual ocean process. J. Clim. 36, 7435–7450 (2023).

Ding, R. et al. Multi-year El Niño events tied to the North Pacific Oscillation. Nat. Commun. 13, 3871 (2022).

Zhou, S. & Liu, F. Southern Hemisphere volcanism triggered multi-year La Niñas during the last millennium. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 41, 587–592 (2023).

DiNezio, P. N. & Deser, C. Nonlinear controls on the persistence of La Niña. J. Clim. 27, 7335–7355 (2014).

DiNezio, P. N. et al. A 2 year forecast for a 60–80% chance of La Niña in 2017–2018. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 11624–11635 (2017).

Kim, J.-W., Yu, J.-Y. & Tian, B. Overemphasized role of preceding strong El Niño in generating multi-year La Niña events. Nat. Commun. 14, 6790 (2023).

Park, J. et al. Mid-latitude leading double-dip La Niñas. Int. J. Climatol. 41, E1353–E1370 (2021).

Wang, B. et al. Understanding the recent increase in multiyear La Niñas. Nat. Clim. Change. 13, 1075–1081 (2023).

Kim, H.-M., Webster, P. J. & Curry, J. A. Modulation of North Pacific tropical cyclone activity by three phases of ENSO. J. Clim. 24, 1839–1849 (2011).

Ha, Y. & Zhong, Z. Contrast of tropical cyclone frequency in the western North Pacific between two types of La Niña events. Sci. China Earth Sci. 56, 397–407 (2013).

Guo, Y.-P. & Tan, Z.-M. Westward migration of tropical cyclone rapid-intensification over the Northwestern Pacific during short duration El Niño. Nat. Commun. 9, 1507 (2018).

Chen, X., Guo, Y.-P., Tan, Z.-M. & Zhao, J. Influence of different types of ENSO events on the tropical cyclone rainfall over the western North Pacific. Clim. Dyn. 60, 3969–3982 (2023).

Geng, T. et al. Increased occurrences of consecutive La Niña events under global warming. Nature 619, 774–781 (2023).

Liu, K. S. & Chan, J. C. L. Climatological characteristics and seasonal forecasting of tropical cyclones making landfall along the South China Coast. Mon. Wea. Rev. 131, 1650–1662 (2003).

Raj Deepak, S. N. et al. Impact of multiyear La Niña events on the South and East Asian summer monsoon rainfall in observations and CMIP5 models. Clim. Dyn. 52, 6989–7011 (2019).

Singh, P., Chowdary, J. S. & Gnanaseelan, C. Impact of prolonged La Niña events on the Indian Ocean with a special emphasis on southwest Tropical Indian Ocean SST. Glob. Planet. Change 100, 28–37 (2013).

Zhu, T. & Yu, J.-Y. Distinguishing Impacts on Winter Temperatures in Northern Mid–High-Latitude Continents during Multiyear and Single-Year La Niña Events: A Modeling Study. J. Clim. 37, 3943–3958 (2024).

Chan, J. C. L. The physics of tropical cyclone motion. Annu. Rev. Fluid Mech. 37, 99–128 (2005).

Xie, S.-P. & Philander, S. G. H. A coupled ocean-atmosphere model of relevance to the ITCZ in the eastern Pacific. Tellus A 46, 340–350 (1994).

Xie, S.-P. & Tanimoto, Y. A pan-Atlantic decadal climate oscillation. Geophys. Res. Lett. 25, 2185–2188 (1998).

Li, X., Xie, S.-P., Gille, S. T. & Yoo, C. Atlantic-induced pan-tropical climate change over the past three decades. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 275–279 (2016).

Lu, R. Impact of Atlantic sea surface temperature anomalies on the summer climate in the western North Pacific during 1997–1998. J. Geophys. Res. 110, D16102 (2005).

Gill, A. E. Some simple solutions for heat-induced tropical circulation. Q. J. R. Met. Soc. 106, 447–462 (1980).

Kucharski, F. et al. A Gill-Matsuno-type mechanism explains the tropical Atlantic influence on African and Indian monsoon rainfall: gill response to tropical Atlantic SST forcing. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 135, 569–579 (2009).

Yao, S., Zhou, W., Jin, F. & Zheng, F. North Atlantic as a trigger for Pacific‐wide decadal climate change. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094719 (2021).

Matsuno, T. Quasi-geostrophic motions in the equatorial area. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 44, 25–43 (1966).

Rong, X., Zhang, R. & Li, T. Impacts of Atlantic sea surface temperature anomalies on Indo-East Asian summer monsoon-ENSO relationship. Chin. Sci. Bull. 55, 2458–2468 (2010).

Yu, J., Li, T., Tan, Z. & Zhu, Z. Effects of tropical North Atlantic SST on tropical cyclone genesis in the western North Pacific. Clim. Dyn. 46, 865–877 (2016).

Cassou, C. & Terray, L. Oceanic forcing of the wintertime low-frequency atmospheric variability in the north atlantic european sector: a study with the ARPEGE model. J. Clim. 14, 4266–4291 (2001).

Wallace, J. M. & Gutzler, D. S. Teleconnections in the geopotential height field during the Northern Hemisphere Winter. Mon. Wea. Rev. 109, 784–812 (1981).

Song, J. & Klotzbach, P. J. Relationship between the Pacific‐North American pattern and the frequency of tropical cyclones over the Western North Pacific. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 6118–6127 (2019).

Müller, W. A. & Roeckner, E. ENSO impact on midlatitude circulation patterns in future climate change projections. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L05711 (2006).

Horel, J. D. & Wallace, J. M. Planetary-scale atmospheric phenomena associated with the Southern Oscillation. Mon. Wea. Rev. 109, 813–829 (1981).

Jiménez-Esteve, B. & Domeisen, D. I. V. The tropospheric pathway of the ENSO–North Atlantic teleconnection. J. Clim. 31, 4563–4584 (2018).

Zhang, W., Wang, L., Xiang, B., Qi, L. & He, J. Impacts of two types of La Niña on the NAO during boreal winter. Clim. Dyn. 44, 1351–1366 (2015).

Zhang, W. et al. Impact of ENSO longitudinal position on teleconnections to the NAO. Clim. Dyn. 52, 257–274 (2019).

Klein, S. A., Soden, B. J. & Lau, N.-C. Remote sea surface temperature variations during ENSO: evidence for a tropical atmospheric bridge. J. Clim. 12, 917–932 (1999).

Chen, J. et al. Tropical and subtropical Pacific sources of the asymmetric El Niño‐La Niña decay and their future changes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL097751 (2022).

Rodrigues, R. R. & McPhaden, M. J. Why did the 2011–2012 La Niña cause a severe drought in the Brazilian Northeast? Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 1012–1018 (2014).

Ham, Y.-G., Kug, J.-S., Park, J.-Y. & Jin, F.-F. Sea surface temperature in the north tropical Atlantic as a trigger for El Niño/Southern Oscillation events. Nat. Geosci. 6, 112–116 (2013).

Wang, X., Wang, C., Zhou, W., Wang, D. & Song, J. Teleconnected influence of North Atlantic sea surface temperature on the El Niño onset. Clim. Dyn. 37, 663–676 (2011).

Lu, X. et al. Western North Pacific Tropical Cyclone Database created by the China Meteorological Administration. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 38, 690–699 (2021).

Ying, M. et al. An overview of the China Meteorological Administration Tropical Cyclone Database. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 31, 287–301 (2014).

Hersbach, H. et al. ERA5 monthly averaged data on pressure levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS), https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.6860a573 (2023).

Hersbach, H. et al. ERA5 monthly averaged data on single levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS), https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.f17050d7 (2023).

Hersbach, H. et al. ERA5 hourly data on pressure levels from 1940 to present. Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS), https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.bd0915c6 (2023).

Cai, W., Van Rensch, P., Cowan, T. & Hendon, H. H. Teleconnection pathways of ENSO and the IOD and the mechanisms for impacts on Australian Rainfall. J. Clim. 24, 3910–3923 (2011).

Yanai, M., Esbensen, S. & Chu, J.-H. Determination of bulk properties of tropical cloud clusters from large-scale heat and moisture budgets. J. Atmos. Sci. 30, 611–627 (1973).

Yanai, M., Li, C. & Song, Z. Seasonal heating of the Tibetan plateau and its effects on the evolution of the Asian Summer Monsoon. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 70, 319–351 (1992).

Neale, R. B. et al. Description of the NCAR Community Atmosphere Model (CAM 5.0)., NCAR Tech. Note NCAR/TN-486+STR. Natl. Cent. for Atmos. Res, Boulder, Colo. 289 (2012).

Rayner, N. A. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. J. Geophys. Res. 108, 4407 (2003).

Danabasoglu, G. et al. The Community Earth System Model Version 2 (CESM2). J. Adv. Model Earth Syst. 12, e2019MS001916 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (92158204) and the second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research (STEP) program (Grant 2019QZKK010201-02). L.Y. is also supported by GuangDong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2022A1515010945); National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFE0203500); Science and Technology Program of Guangdong Province (2022B1212050003), and special fund of South China Sea Institute of Oceanology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (SCSIO2023QY01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Y. and X.L. contributed to the conception of this study and wrote the manuscript. X.L. conducted the data analyses and prepared Figures. S.C. conducted the numerical experiments. Johnny C.L. Chan, Q.H.P. and D.X.W. reviewed the manuscripts and contributed to the interpretation of the results. All authors discussed the results of the study and contributed to the manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, X., Yang, L., Chan, J.C.L. et al. China coasts facing more tropical cyclone risks during the second decaying summer of double-year La Niña events. npj Clim Atmos Sci 7, 198 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00729-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00729-8

This article is cited by

-

Unusual role of positive Indian Ocean Dipole in the record-low tropical cyclone genesis over the Western North Pacific in 2023

npj Climate and Atmospheric Science (2025)