Abstract

Reanalysis and satellite data indicate a decreasing precipitation area in recent decades, affecting local water resources and precipitation intensities. We have used CMIP6 simulations to test the hypothesis of a shrinking precipitation area in a warming climate. Our analyses reveal that SSP5-8.5 projections show a robust decrease in the precipitation area between 50 °S and 50 °N, and globally in 75% of the simulations. The new findings support the observed relationship, although to a lesser extent than earlier found in reanalysis and satellite data. We find a poleward shift of precipitation, increasing the daily precipitation area in the Arctic from 18% to 28%. At lower latitudes the precipitation area is reduced due to a decreasing occurrence of precipitation. These changes are related to the expansion of low relative humidity zones in the lower-to-mid troposphere, specifically at the poleward edges of the subtropics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Traditionally, there have been only few climate indicators that describe the state of the global hydrological cycle1. Such indicators need to assess the movement of water within the whole planetary system, subject to global constraints such as evaporation and precipitation. They are thus limited by the extent of global observational networks. However, the maturation of satellite-borne observations after decades of operation, as well as state-of-the-art global reanalyses such as ERA52, NCEP13 and ERA-20C4, have made it possible to address new questions about our global climate system, and to formulate new indicators describing the state of the global hydrological cycle, such as i) the total daily mass of precipitation falling on Earth’s surface, ii) the global surface area receiving precipitation each day, and iii) the global mean daily precipitation intensity1.

The three indicators are directly interrelated, as the global mean daily precipitation intensity can be calculated as the ratio of the total daily precipitation mass to the daily precipitation area. The intensity can thus increase either due to an increased global precipitation mass or a reduced precipitation area. The 6th assessment report5 (AR6) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) states a virtually certain increase in global precipitation and high confidence in increasing precipitation intensities for most areas under global warming. Although the number of wet-days is shown to decrease over many land areas from the tropics to the mid-latitudes and to increase at higher latitudes5, the complete surface area (land+ocean) receiving precipitation on a daily basis has not been given much consideration in literature.

One analysis6 based on satellite data from the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission7 has suggested that the fraction of Earth’s surface receiving daily rainfall between 50 °S and 50 °N has decreased by 7% over the period 1998–2016, while at the same time the total precipitation amount and the precipitation intensity have increased. A more recent study8 based on reanalysis data has estimated that increases in the global mean precipitation intensity in ERA5 are to 48.5% due to an increased total mass of precipitation and to 51.5% due to a decreased surface area on which it falls.

The contribution of a reduced precipitation occurrence to intensified precipitation aligns with other findings9 reporting that if the atmospheric concentration of water vapor increases by 7% per degree of warming, while global precipitation increases by approximately 2% per degree10,11, the average speed of the circulation moving water vapor must decrease and the atmospheric residence time increase12. Similar observations were made in a recent review study13, highlighting the impact of climate change on atmospheric circulations with respect to water resources. The study identified key issues such as the global circulation slowdown, changes in planetary circulations (including Hadley and Walker cells), and the development of anomalous regional circulations. Additionally, it critically assessed the commonly used assertion that “wet areas will become wetter and dry areas will become drier,” concluding that while this pattern holds more accurately over oceans, it should not be universally applied to land. Instead, it is more accurate to state that the wet seasons are likely to become wetter and dry seasons drier under the influence of greenhouse gas (GHG) warming. This differential intensification of seasonal precipitation has been corroborated by multiple studies14,15,16,17, showing the most significant increases in already wet regions18 and attributing these changes to enhanced water vapor transport into precipitation zones during seasons predisposed to convergence.

Such changes will have profound implications for nature and society, since a reduced precipitation area leads not only to more dry regions on average but also, assuming an increase in the total amount, to more intense precipitation in places it actually falls, and hence potentially more floods. A trend towards a diminishing global area of precipitation combined with an increased total amount is therefore a serious concern when it comes to global warming.

There is a caveat with the analysis of temporal trends in satellite data. With different missions and instruments introduced at different times, they have limitations concerning long-term temporal consistency. Although decreases have been found in the ERA5, NOAA 20CRv3, ERA20C and NCEP1 reanalysis data as well1, the precipitation patterns simulated by these modelling systems may also be affected by changes in the amount of data assimilated into the systems. This is especially true when the amount of data is significantly changing throughout the simulation period, as it is the case with satellite data in the ERA5 and NCEP1 reanalysis. Hence, there is some uncertainty as to whether long-term changes indicated in these datasets reflect real changes in Earth’s global hydrological cycle or whether they are artifacts from the synthesis of changing data sources19.

In the present study, we address this question by examining state-of-the-art global climate and Earth system model (GCM) simulations under scenarios of increasing GHG concentration. To find robust signals, we analyse a multi-model ensemble from the latest World Climate Research Programme’s Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP)20,21 simulations, CMIP6. These model simulations provide daily global precipitation patterns without the use of data assimilation and are thus independent of changes in the observational system. A potential lack of a robust response within the multi-model ensemble would be a strong indication that the trends found in satellite1 and reanalysis data6 are artifacts, whereas a clear common signal would suggest that the reduction in the precipitation area is indeed a consequence of increased GHG concentrations.

We further investigate how vertical distributions of atmospheric relative humidity (RH) in the ERA5 reanalysis and CMIP6 models are related to changes in the global precipitation area. For CMIP5 model projections, it has been shown22 that changes in the atmospheric RH are associated with a Hadley Cell expansion under global warming and are leading to a drying of the surface at (sub-)tropical latitudes. The IPCC AR65 states a likely poleward expansion of the Hadley Cells in recent decades. Such an atmospheric (relative) drying may be a cause for a reduction in the global precipitation area.

Results

Precipitation area

We have calculated the surface fraction with daily precipitation of more than 1 mm from an ensemble of global climate and Earth system models (GCMs) and the ERA5, ERA-20C and NCEP1 reanalyses. Figure 1 presents time-series of the annually aggregated fractions between 50 °S and 50 °N from 27 CMIP6 model runs and the reanalyses.

The precipitation area is shown for 27 CMIP6 models following SSP5-8.5, the ERA5, ERA-20C and NCEP1 reanalysis. The CMIP6 models have been sorted by increasing mean zonal resolution, where blue denotes the lowest and red the highest spatial resolution. The numbers to the right of the coloured lines refer to the single models where the ordinate indicates the precipitation area in the last year of the corresponding simulation. a shows the precipitation area and (b) the 30-year running mean deviations (in percentage points) from the models' precipitation area in the reference period (1991–2020, 1981–2010 for ERA-20C). The box-plot on the right in (b) shows the inter-quartile (box) and 0.05–0.95 quantile range (dotted line) of the CMIP6 model deviations for the period 2071-2100.

The ERA5 and NCEP1 reanalyses show a step-wise decrease in the precipitation area in the 20th century and a continuing decrease since the beginning of the 21st century (Fig. 1a). ERA-20C, which does not involve the assimilation of satellite data, suggested little changes over time with only a slight increase at the beginning and a small decrease at the end of the 20th century. The numbers and changes shown here are in agreement with what is shown and discussed in earlier studies1,19, revealing some uncertainty in the changes proposed by the different reanalyses datasets, and stresses the importance of caution when studying trends in them.

Looking at the GCM time-series, there is a substantial spread among the GCMs for the current climate, roughly within the range of 35%–55%. Models with low resolution tend to show a larger precipitation area than models with higher resolution, but there are several exceptions. For instance the FGOALS-g3 and NESM3 models show a relatively low precipitation area compared to other models of similar resolution. A scatter plot of precipitation area against model resolution (Fig. S1) supports the general tendency but does not show a statistically significant linear relation. In agreement with the ERA5 data, a decrease in the precipitation area is also apparent for the GCMs during the 21st century, with the exception of FGOALS-g3. However, the drop in ERA5 from about 44% to 42% during the period 1940–2020 is not reproduced in the GCM data.

A clearer comparison between the models is given in Fig. 1b after subtracting the precipitation area for the reference period (1991–2020) from each model and calculating 30-year running means. A striking observation is a grouping of 18 GCMs showing decreases between 1.25 and 2.25 percentage points (pp). The only model showing an increase (FGOALS-g3) stands out even more clearly. Five of the remaining GCMs (models 2, 8, 9, 10 and 19) indicate a weaker, but still negative change while three more models (1, 24 and 25) show a decrease of about 1 pp and are close to the dominating group of 18 GCMs. The resulting median of the precipitation area anomaly at the end of the simulations is clearly negative with −1.5 pp and the inter-quartile-range (IQR) spans from −1.1 to −2 pp. The estimated 90% confidence interval from the 27 simulations ranges from −0.2 to −2.3 pp, i.e. there is a large agreement among the models on a decreasing precipitation area. For ERA5, the 30-year running mean precipitation area at the beginning of the dataset (1940–1969) is 2.4 pp higher than in the period 1991-2020.

Extending the calculation of the precipitation area to the whole globe does not change the general picture (Fig. S2). Although globally more models project a small increase or no clear change, the median (−0.6 pp) and IQR (−0.03 to −0.9 pp) are still below zero, showing an agreement on a decrease in the precipitation area also on the global scale. Further, the group of 18 GCMs that show similar decreases in the precipitation area between 50 °S and 50 °N (Fig. 1) also agree on a decrease in the global precipitation area and the FGOALS-g3 remains an outlier with a marked increase (Fig. S1).

The agreement of all analysed GCMs (except the FGOALS-g3 model) on a decreasing precipitation area between 50 °S and 50 °N in the 21st century (Fig. 1) is convincing. To our knowledge, this behaviour has not been reported before. However, the contrast between ERA5’s step-like temporal response and the GCM’s smoother temporal trend, as well as the distinctly different behaviour of the FGOALS-g3, model are intriguing and suggest a more detailed analysis of possible reasons.

Some further insights can be gained by analysing how the precipitation area is distributed on Earth’s surface along different latitudes. Figure 2 shows the zonal precipitation area climatologies and their changes in time for the multi-model median (MMM) of the 27 CMIP6 simulations, the FGOALS-g3 model (to highlight the outlier) and ERA5. In all three datasets the zonal precipitation area shows a double peak in the tropics, a poleward decline until 20°–25°, an increase thereafter until 60° and another decline afterwards towards the poles. These latitudes are roughly reflecting the position of the inter-tropical convergence zone (ITCZ), the tropics, the subtropics and mid-latitudes, and the high latitudes. We note that in the FGOALS-g3 model the extension of the tropics is slightly narrowed. The latitudinal band with the largest areal fraction receiving precipitation on an average day is located at around 55 °S in the MMM and FGOALS-g3 with a fraction of about 70%. ERA5 shows the same peak at 55 °S, but has its overall maximum at 5 °N which is significantly larger than the MMM value at the same location. Note that these numbers are fractions of Earth’s circumference at the specific latitudes. At 55° this is about 0.6 times the circumference at the equator. Thus, the largest absolute zonal area receiving precipitation on an average day is located at about 5 °N for all datasets.

The fraction of a zonal sector of Earth which is receiving more than 1 mm precipitation per day. Colours refer to different time periods and line types indicate different data sources (MMM=multi-model median). The light green lines show past changes from 1941–1970 (light blue) to 1991–2020 (dark blue). Dark green lines show future changes between the GCM reference period 1991–2020 (dark blue) and the far future period 2071–2100 (red).

Changes in the zonal precipitation area (Fig. 2) show that the area is mostly decreasing in a band between 5° and 50° on both hemispheres. The decreases are more clear and pronounced in the Southern Hemisphere, where the strongest decrease can be seen around 35 °S in the MMM. Close to the Equator, there is a slight increase in the MMM, a more pronounced increase in FGOALS-g3 and a decrease in ERA5. A common agreement among all three datasets is an increase polewards of 55°, especially in the Arctic. Although less pronounced, ERA5 and the MMM already show this increase when comparing the recent climate (1991–2020) to an earlier period (1941–1970). The increase is continuing in the GCM future projections and the MMM shows an increase in the average daily precipitation area in the Arctic from about 18% in the current climate to about 28% in the projected future climate. The actual size of this area is relatively small (due to its high latitude) and the regional increase has only little impact on the overall global precipitation area. Nevertheless, it can explain the small difference in the changes of the global precipitation area and changes between 50 °S to 50 °N noted above. Compared to the MMM, the FGOALS-g3 model shows small or almost no decreases between 10° and 50° on both hemispheres. Together with the more pronounced increase in FGOALS-g3 around the Equator, this yields an overall increase in the global precipitation area. Another outstanding difference is a decrease between about 5 °S and 30 °N in ERA5 which is not apparent in the GCM projections.

While only the MMM and the FGOALS-g3 model are shown in Fig. 2, the latitudinal patterns of the precipitation area and its changes are qualitatively similar for all other GCMs (Fig. S3). The large agreement among the GCMs on the changes between 50 °S and 50 °N explains the robustness of the shrinking precipitation area simulated in this region (Fig. 1) and the differences shown for ERA5 and FGOALS-g3 can explain their deviations. The partly less robust decrease for the global precipitation area is caused by larger variations over the polar regions among the GCMs, especially for the Arctic (Fig. S3), as the magnitude and extent of the increases in the single models in this region can counteract the common decrease at lower latitudes.

Precipitation frequency and relative humidity

While most GCMs and the ERA5 reanalysis show a decrease in the global precipitation area, a decrease between 5 °S and 25 °N is only apparent in ERA5. This suggests that different processes lead to the reductions in ERA5 and the GCMs. Likewise, the significantly different behaviour of the FGOALS-g3 model requires an explanation. One possible explanation is suppressed precipitation related to changes in the tropospheric relative humidity (RH) due to modifications in the Hadley Circulation22.

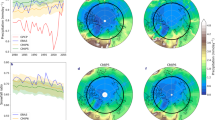

Figures 3a and b show a latitude-vertical cross-section of zonal average RH changes from the MMM for the past (1941–1970 to 1991–2020) and the future (1991–2020 to 2071–2100), respectively. A strong increase in RH is apparent near the top of the troposphere. An increase is also present in the lower troposphere in the proximity of the Poles, as well as in the lower and middle troposphere around the Equator. Decreases in RH are happening throughout most of the troposphere from about 25°–55° and around the Equator in the upper troposphere, expanding areas of already relatively low RH values. Further, there is a narrowing and upward expansion of the zone with relatively high RH amounts just around the equator. The change patterns in the past and in the future period highly resemble each other, but the future changes are about four times as large as the past changes.

The coloured areas show relative humidity (RH) changes (in percentage points) from the reference state which is given as contours. In (a) and (d), the reference period is 1941–1970 and changes are shown for the period 1991–2020, i.e. the past. Note the different colour scale used in (a). In (b) and (c), the reference period is 1991–2020 and changes are shown for the future period 2071–2100 following the SSP5-8.5 scenario. The dotted lines mark an area where the RH averages show a high temporal correlation with the MMM and ERA5 precipitation area, respectively.

The future RH changes from the different GCMs show some variations, but the general pattern is similar (Fig. S4). They resemble changes for CMIP522 and CMIP323 GCMs, indicating a robust model response to global warming not only within but also over different CMIP generations. However, for the FGOALS-g3 model, the pattern of RH changes differs substantially (Fig. 3c). While a weak drying is also apparent in the mid-to-lower troposphere around 25 °S, no drying is detectable in the Northern Hemisphere with the exception of a small near-surface area in the Arctic. Most strikingly, and contrary to the MMM and all the other GCMs, the FGOALS-g3 model shows an increase of RH throughout the whole troposphere around the Equator. This area is locally coinciding with the anomalously large increase in the FGOALS-g3 zonal precipitation area (Fig. 2).

A decrease around 25 °S, an increase in the polar regions, as well as at the top of the troposphere around the equator are also present in the ERA5 data (Fig. 3d). However, in ERA5 a decrease in RH in the lower troposphere is visible from 5 °S to about 30 °N. Again, this area corresponds well to the area where ERA5 shows an outstanding decrease in the zonal precipitation area not detectable in the GCMs (Fig. 2).

The results above show that the latitudinal positions and the sign of RH changes in the lower-to-mid troposphere correspond to the changes in the zonal precipitation area. This is true for the MMM, ERA5 and also the FGOALS-g3 model, indicating that these RH changes are directly connected to the precipitation area. This connection can also be found in time-series of RH averaged over an area showing high temporal correlations with time-series of the precipitation area (Fig. 4). From the time-series it becomes clear that not only the climatological changes in RH and the precipitation area are related, but also the temporal development of RH and the precipitation area (Fig. 1) throughout the simulation periods are similar in all models, i.e. showing a general decrease in the GCMs, an increase in FGOALS-g3 and a step change in ERA5.

The lines correspond to the annual mean relative humidity averaged over the areas shown in Fig. 3. Note that the ERA5 region is different from the GCM region as the regions reflect the area of the most pronounced RH changes in the corresponding data. Therefore, the RH values in ERA5 have a different magnitude than the GCM values.

The smooth changes in the GCM projections of RH (Fig. 4) align with gradual changes associated with GHG warming, which are evident both in GCM projections22 and in recent historical data24. However, the abrupt decline in ERA5 in the precipitation area (Fig. 1) and RH (Fig. 4) during the 1980s is challenging to explain through physical processes, and the discrepancy between the GCMs and ERA5 is striking.

The drop in ERA5 happens around the assimilation of the first satellite microwave imager data in 19872. While a detailed investigation into the causes of this is beyond the scope of the present study, additional analyses of hourly RH data from ERA5 (Fig. 5) show that the major RH drops start to appear in the year 1987 at the beginning of each data assimilation window (09:00 and 21:00 UTC). Although the RH is gradually increasing during the 12 hours of assimilation in the period 1991–2020, it is continuously reset to a lower level (approx. 62% to 63%) by new assimilation cycles starting every 12 hours.

Mean diurnal cycle of relative humidity at 850 hPa between 50 °S and 50 °N from ERA5 for the time periods 1941–1970 (light blue) and 1991-2020 (dark blue). The grey boxes indicate the start of new data assimilation windows at 09:00 and 21:00 UTC. Initial states for the subsequent forecasts at 18:00 and 06:00 UTC are indicated with a cross.

Nine hours into the 09:00 assimilation cycle (i.e. at 18:00 UTC) in the 1991–2020 period, RH remains noticeably lower than at the end of the previous assimilation cycle (Fig. 5). This drier state is then used to initialize the subsequent forecast, starting at 18:00 UTC, followed by a drop in the hourly precipitation area during the first forecast hour (Fig. S5). In other words, the decrease in the precipitation area follows one hour after the humidity reduction at initialization.

Regional implications

The temporarily averaged zonal mean precipitation areas shown in Fig. 2 are equivalent to the zonal mean wet-day frequencies for the same time periods (see Methods). Thus, maps of wet-day frequency changes can reveal how different regions are affected by the expansion of the dry regions in the mid-latitudes and the poleward shift of precipitation.

Figure 6a shows the spatial distribution of changes in the number of wet-days per year from the reference period 1991–2020 to the future period 2071–2100 based on the multi-model median (MMM). The wet-day frequency decreases in large areas between 50 °S and 50 °N, especially in the Southern Hemisphere, as can be expected from Fig. 2. The GCMs highly agree on a decrease in the Southern Hemisphere between 5° and 50° and on an increase at latitudes above 50° to 60° on both hemispheres. Regionally, the number of wet-days shows the largest increase in the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean and the Eurasian part of the Arctic Ocean. Smaller increases are shown in eastern equatorial Africa, India, north-eastern Russia, northern America, Greenland and Antarctica. Decreases in the number of wet-days are most pronounced in Central America, including the Amazon, and over the south-east Indian Ocean. Slightly weaker decrease can be seen for most of Europe (except the Nordic and Baltic countries) and many ocean basins, including the Mediterranean, North Atlantic and south-east Pacific. Maps showing the number of wet-days per year for the reference period and relative changes are provided as supplementary information (Fig. S6), highlighting large relative increases in the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean and over Antarctica.

Changes from the reference to the future period 2071–2100 following SSP5-8.5 for (a) the annual number of wet-days, (b) daily precipitation intensities and (c) the annual precipitation amounts. The changes are shown for the ensemble median and only where more than 75% of the models agree on the sign of change.

While wet-day frequency and intensity are generally positively correlated25, changes in dynamics and thermodynamics due to global warming may alter these correlations. Figure 6b shows the relative changes in daily precipitation intensities in the MMM. Maps for the reference period and absolute changes are provided as supplementary information (Fig. S7). There is an increase in wet-day intensities for most areas in agreement with a faster hydrological cycle in a warming climate. The largest increase is (again) found in the eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean. Decreases are limited to regions over the south-eastern parts of the Pacific, the Indian and Atlantic Ocean, as well as a band from the Caribbean extending across the Atlantic towards the Canary Islands. Notably, these are regions with very few wet-days in the current climate (Fig. S6). Further, Fig. 6 reveals areas showing a decreasing frequency but increased intensity, i.e. fewer but more intense precipitation events on average, namely the Mediterranean, south-eastern Africa and the north Atlantic Ocean.

Relative precipitation changes from the reference period 1991–2020 to the future period 2071–2100 are shown in Fig. 6c. Maps for the reference period and absolute changes are provided as supplementary information (Fig. S8). The largest decreases are found in the eastern parts of the oceans in the Southern Hemisphere, as well as a band from Central America across the Atlantic and into the Mediterranean region. Generally, the change patterns in total precipitation are similar to the frequency changes but with smaller areas of decrease as a result of the decreasing frequency being compensated by an increasing intensity.

Figure 6 shows that more total precipitation is related to more intense precipitation almost everywhere. This can either be less frequent precipitation, projected mostly over ocean areas around 50° (S and N), or, much more commonly, more frequent precipitation, as for instance in the polar regions. Less total precipitation, on the other hand, is related to less frequent precipitation. Over a few ocean areas (west of Chile, South-Africa and Australia and south of the Gulf Stream) less precipitation is accompanied by less intense mean precipitation, but mostly it goes along with more intense average precipitation, as for instance in the Mediterranean region.

Overall, the total global amount of precipitation in the MMM is increasing from 1407 Gt/d to 1488 Gt/d, i.e. showing an increase of about 6%. The precipitation area in the MMM is decreasing from 39.3% to 38.8% of Earth’s surface at the same time (1.3% decrease), resulting in a global mean wet-day intensity increase from 7 mm/d to 7.5 mm/d. In other words, the intensity increase in the MMM (by about 7%) is to 82% due to an increase in the total precipitation mass and to 18% due to a decrease in the precipitation area. These numbers significantly differ from the more equal numbers found for ERA5 (48.5% and 51.5%, respectively) but still indicate a substantial contribution of a shrinking precipitation area to the increasing wet-day intensity.

Discussion

First of all, our results confirm an earlier study1 showing that the daily precipitation area estimated from ERA5 drops abruptly between 1980 and 1990 and continues to decrease afterwards. However, the decreases apparent in ERA5 may be a spurious feature due to a changing observation system being assimilated into the reanalysis system1,19. Thus, we have repeated the analysis with data from GCM projections under global warming, as these are not affected by changing observational inputs or data assimilation. Our results reveal a decrease in the global precipitation area in the GCM projections as well, although of a smaller magnitude than in ERA5. This suggests that the ERA5 reanalysis indeed shows a spurious artificial trend in the daily precipitation area. However, on top of this, there is possibly an emerging shrinking effect of a warming climate on the global precipitation area which, to our knowledge, has not been reported before. A shrinking of the global precipitation area would be relevant both in terms of regionally reducing water resources, and increasing precipitation intensities due to precipitation falling on a smaller area.

Our further analyses have shown that the precipitation area changes in the GCMs are a result of a poleward shift of precipitation events. On both hemispheres we have found a robust decrease in the precipitation area from about 5° to 50°, as well as increases at high latitudes and around the Equator. The latitudinal positions of the precipitation area changes match closely the positions of changes in relative humidity (RH) in the lower-to-mid troposphere. This is valid for the ERA5 reanalysis and the GCMs, but also for the FGOALS-g3 model which shows an unusual increase in the precipitation area together with an uncommon RH change pattern, highlighting the linkage between RH and precipitation occurrence. The RH changes in GCMs (other than FGOALS-g3) are similar to changes in CMIP5 models22. They have previously been related to changes in the Hadley Circulation together with an increase in dynamic convergence at the equator and an increase in subsiding dry air poleward of the subtropics22. This is well known to lead to a widening of the zones with low RH located in the subtropics5, and the so-called “deep-tropics squeeze”22 to a moistening in the core of the ITCZ5. Our results additionally reveal that the expansion of the low RH zones are associated with local decreases in the precipitation frequency, a behaviour also shown for climate model simulations over the Mediterranean region26.

The correlation between atmospheric RH and the precipitation area does not imply that RH is the driving factor; it could be a consequence of the later, or both could stem from a common driver (e.g. changes in low-level moisture convergence). However, the correlation highlights the value of analyzing atmospheric RH fields to differentiate and better understand how changes in temperature, general circulation, and moisture transport influence precipitation, its intensity and the precipitation area. Additionally, while the mechanisms in ERA5 and the GCMs that lead to the reduced precipitation area may differ, the analysis of hourly ERA5 data have revealed that the areal reduction follows a decrease in RH in the lower atmosphere. Notably, the RH is not directly affected by the sudden decrease in the precipitation area but rather by the initiation of data assimilation. This shows that, at least in ERA5, the reduced RH in the lower atmosphere is not caused by decreased precipitation.

Based on our results we conclude that the gradual and steady decline in the precipitation area in the GCMs, and underlying in the reanalysis data, is caused by GHG warming. The more abrupt reductions observed in ERA5 are linked to the introduction of satellite data assimilation. Note that a recent study19 came to similar conclusions regarding the shift of ERA5 precipitation towards smaller scales, stating that “assimilation of satellite data looks like the most convincing explanation.”

Maps of wet-day frequency, intensity and total precipitation changes show that mean intensities increase nearly everywhere. However, the total precipitation may be reduced due to fewer precipitation days. The geographical patterns of these changes are similar to those from simulations used in the IPCC 4th assessment report27. Interestingly, the changes in wet-day frequency also resemble changes in the dynamic contribution and vertical velocities for annual maximum precipitation28, indicating that wet-day frequency may be used as a relatively easy to derive proxy for changes in atmospheric dynamics. Although we only show changes in mean values here, we note that the patterns are similar to changes in annual maximum precipitation and precipitation extremes scaling28. Thus, there seems to be a linkage between changes in the mean wet-day frequency, intensity and local heavy precipitation that may also be used to statistically derive robust estimates of the latter8.

All results shown in this study represent the whole year and do not resolve different seasons, which potentially would change the results in different directions or to different degrees. The main objective here was 1) to show to what extent reductions in daily precipitation areas found earlier in satellite observations and reanalyses, are apparent in GCM simulations and 2) to provide possible reasons for the changes and their differences. The GCM simulations we have used are following the SSP5-8.5 scenario. Time-series for other scenarios (SSP3-7.0, SSP2-4.5, RCP8.5 and RCP4.5) and from a larger ensemble of SSP5-8.5 simulations are provided in the supplementary information (Figs. S9–S13) and support our main findings on a shrinking daily precipitation area in a warming climate with increasing GHG concentrations.

We have found no clear effect of any model specification or components on the simulated precipitation area, apart from a partial relation to the horizontal spatial resolution. A preliminary analysis (not shown) indicates that the specification of the atmosphere top and aerosol components may have a weak effect on the trends, but the model sample was not sufficiently large to yield statistically significant results. A more detailed factorial regression analysis based on the GCM metadata is out of the scope of this study and left to future work.

As a last point, we want to mention that the calculation of wet-day frequencies and intensities from ERA5 and CMIP6 runs requires the handling of relatively large daily, in case of ERA5 even hourly, precipitation data sets. To reduce the data transfer amount, we have used server-side data processing facilities. Nevertheless, a significant computational effort was required to process the data. Our results show that an analysis of wet-day frequency and intensity can provide more detailed insights than merely looking at mean precipitation. Thus, it would be desirable to provide (monthly) wet-day frequency and intensity as a standard output variable in reanalyses and GCM simulations. The calculation of wet-day frequencies (typically above 1 mm) could even be implemented as a counting variable in the code of the models, making a subsequent calculation unnecessary.

Methods

Rain area calculation

The global and 50 °S to 50 °N precipitation area has been calculated from daily fields of precipitation on a regular latitude-longitude grid. At a specific latitude j, the zonal mean precipitation fraction over the longitudes i = 1, …, i = ni at time t is given by

Averaging the zonal mean precipitation fraction in time, e.g., over the 30 years reference period, the equation becomes

This is equivalent to the zonal mean of the wet-day frequencies for the same time period

Thus, temporal means of the precipitation area can be derived from wet-day frequencies for the same time period. To calculate the global precipitation area (or fraction), the zonal means need to be weighted with the cosine of the corresponding latitude to take into account the shrinking grid cell size towards the poles, i.e.

Data availability

The analysed ERA5 data is available in the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Data Store (CDS) repositories. Precipitation is available in ERA5 hourly data on single levels from 1940 to present, https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.adbb2d47. Relative humidity is hosted in the ERA5 monthly averaged data on pressure levels from 1940 to present repository, https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.6860a573. Daily precipitation and monthly relative humidity from CMIP5 and CMIP6 GCMs analysed in this study are available from https://esgf-data.dkrz.de/search/cmip5-dkrz/or https://esgf-data.dkrz.de/search/cmip6-dkrz/. For a subset of 27 CMIP6 models (see Table S1), pre-calculated annual wet-day precipitation, intensity and frequency data is available in the Climate extreme indices and heat stress indicators derived from CMIP6 global climate projections C3S CDS repository, https://doi.org/10.24381/cds.776e08bd. Our main results are based on these 27 models to facilitate the reproduction of our results by omitting the necessity to recalculate the indices for the complete ensemble.

References

Benestad, R. E. et al. Global hydro-climatological indicators and changes in the global hydrological cycle and rainfall patterns. PLOS Clim. 1, 0000029 (2022).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorolog. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Kalnay, E. et al. The NCEP/NCAR 40-year reanalysis project. Bull. Am. Meteorolog. Soc. 77, 437–471 (1996).

Poli, P. et al. ERA-20C: An atmospheric reanalysis of the twentieth century. J. Clim. 29, 4083–4097 (2016).

Douville, H. et al. Water cycle changes. In: Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. (eds.) Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 1055–1210). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.010 (2021). Chap. 8.

Benestad, R. E. Implications of a decrease in the precipitation area for the past and the future. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 044022 (2018).

Simpson, J., Adler, R. F. & North, G. R. A proposed tropical rainfall measuring mission (TRMM) satellite. Bull. Am. Meteorolog. Soc. 69, 278–295 (1988).

Benestad, R. E., Lussana, C. & Dobler, A. A link between the global surface area receiving daily precipitation, wet-day frequency and probability of extreme rainfall. Discov. Water 4, 10 (2024).

Allan, R. P. et al. Advances in understanding large-scale responses of the water cycle to climate change. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1472, 49–75 (2020).

Held, I. M. & Soden, B. J. Robust responses of the hydrological cycle to global warming. J. Clim. 19, 5686–5699 (2006).

Collins, M. et al. Long-term Climate Change: Projections, Commitments and Irreversibility. In: Stocker, T.F. et al. (eds.) Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (pp. 1029–1136). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.024 (2013).

Hodnebrog, Ø. et al. Water vapour adjustments and responses differ between climate drivers. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 19, 12887–12899 (2019).

Zaitchik, B. F., Rodell, M., Biasutti, M. & Seneviratne, S. I. Wetting and drying trends under climate change. Nat. Water 1, 502–513 (2023).

Liu, C. & Allan, R. P. Observed and simulated precipitation responses in wet and dry regions 1850–2100. Environ. Res. Lett. 8, 034002 (2013).

Dunning, C. M., Black, E. & Allan, R. P. Later wet seasons with more intense rainfall over Africa under future climate change. J. Clim. 31, 9719–9738 (2018).

Lan, C.-W., Lo, M.-H., Chen, C.-A. & Yu, J.-Y. The mechanisms behind changes in the seasonality of global precipitation found in reanalysis products and CMIP5 simulations. Clim. Dyn. 53, 4173–4187 (2019).

Zhang, Y. & Fueglistaler, S. Mechanism for increasing tropical rainfall unevenness with global warming. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 14836–14843 (2019).

Konapala, G., Mishra, A. K., Wada, Y. & Mann, M. E. Climate change will affect global water availability through compounding changes in seasonal precipitation and evaporation. Nat. Commun. 11, 3044 (2020).

Buschow, S. Tropical convection in ERA5 has partly shifted from parameterized to resolved. Q. J. R. Meteorolog. Soc. 150, 436–446 (2023).

Meehl, G. A. et al. THE WCRP CMIP3 multimodel dataset: a new era in climate change research. Bull. Am. Meteorolog. Soc. 88, 1383–1394 (2007).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Lau, W. K. M. & Kim, K.-M. Robust Hadley Circulation changes and increasing global dryness due to CO2 warming from CMIP5 model projections. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 112, 3630–3635 (2015).

Sherwood, S.C. et al. Relative humidity changes in a warmer climate. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmosph. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009jd012585 (2010).

Lau, W. K. M. & Tao, W. Precipitation-radiation-circulation feedback processes associated with structural changes of the itcz in a warming climate during 1980–2014: An observational portrayal. J. Clim. 33, 8737–8749 (2020).

McErlich, C. et al. Positive correlation between wet-day frequency and intensity linked to universal precipitation drivers. Nat. Geosci. 16, 410–415 (2023).

Brogli, R., Sørland, S. L., Kröner, N. & Schär, C. Causes of future Mediterranean precipitation decline depend on the season. Environ. Res. Lett. 14, 114017 (2019).

Sun, Y., Solomon, S., Dai, A. & Portmann, R. W. How often will it rain? J. Clim. 20, 4801–4818 (2007).

Pfahl, S., O’Gorman, P. A. & Fischer, E. M. Understanding the regional pattern of projected future changes in extreme precipitation. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 423–427 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the CMIP6 community for providing the climate model data, retained and globally distributed in the framework of the Earth System Grid Federation (ESGF). The CMIP6 data and server-side computing resources for this study were made available by the German Climate Computing Centre (DKRZ) under project ID 1088. The results contain modified Copernicus Climate Change Service information 2024. Neither the European Commission nor ECMWF is responsible for any use that may be made of the Copernicus information or data it contains.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AD, REB and CL conceptualized the study. AD and REB performed the data analysis. AD created the figures with inputs from all co-authors. All authors contributed to the writing and revision of the manuscript, the scientific discussion and interpretation of the results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dobler, A., Benestad, R.E., Lussana, C. et al. CMIP6 models project a shrinking precipitation area. npj Clim Atmos Sci 7, 239 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00794-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-024-00794-z