Abstract

This study derives historical and future changes in extreme precipitation events (EPEs) across the Arabian Peninsula (AP) using data from CMIP6 models. Both the frequency and intensity of EPEs are lower in historical CMIP6 data compared to observations. Despite this bias, CMIP6 models offer valuable insights into future climate projections. Across all emission-scenarios, significant increases in EPEs frequency and intensity are expected over the AP. Under the high-emission scenario (SSP5-8.5), some regions may experience a doubling of EPEs by the end-of-the-21st-century. This rise is attributed to several climate change-driven factors, including the southward-shift and intensification of subtropical-westerly-jet, increased transient activity, enhanced dynamical lifting, and increased moisture transport from nearby seas. These factors suggest a future atmosphere that will be more dynamic and moisture-rich than today. While these CMIP6 insights are crucial for guiding adaptation and mitigation strategies, enhanced EPE modeling is essential for precise decision-making amid rising future risks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change is projected to increase the frequency and intensity of extreme precipitation events (EPEs), posing major concerns worldwide1. Flash floods are the most dangerous and economically damaging among all EPE-related hazards2,3. In 2023 alone, global floods caused more than $25 billion in damages and at least 5000 fatalities4,5. Tropical and semi-arid regions, which have experienced a sharp rise in EPEs, are particularly vulnerable3,6,7,8.

The Arabian Peninsula (AP), characterized by semi-arid and water scarcity, is especially susceptible to the impacts of climate change9,10. The region receives most of its annual rainfall during the wet season from November–April, although the southwest AP receives some rainfall in summer from June to September10,11,12,13,14,15,16. The AP has witnessed several devastating flash floods from EPEs in recent decades, including the recent notable events in the Jeddha in 2009 and United Arab Emirates in 202413,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. Studies based on past rainfall records have indicated an increase in frequency and/or intensity of EPEs that cause casualties and infrastructure damage across the AP16,17,21; moreover, an increase in heavy precipitation events over the AP is predicted in future8. Understanding the responses of EPEs over the AP to increasing anthropogenic emissions under various climate change scenarios is crucial for developing effective planning policies and flood-protection infrastructure. Thus far, the EPEs response to climate change has been insufficiently explored.

The large-scale atmospheric circulations driving rainfall over the AP exhibit seasonal changes. In summer, middle- and upper-level subsidence resulting from the Hadley circulation suppresses precipitation over the AP, except in the southwest region where some orographic rainfall occurs11,23,24. Conversely, the atmospheric conditions during the wet season are influenced by upper-level westerly winds, extratropical (or mid-latitude) storms, the Red Sea Trough (RST), and low-level subtropical anticyclones13,15,16,17,19,21,22. The RST (also called the inverted low-level trough or Sudan Low), which expands northward from the tropical low-pressure zone over equatorial Africa across the Red Sea, and the subtropical anticyclone over the AP and Arabian Sea at lower–middle tropospheric levels, are important for moisture and rainfall over the AP13,14,15,17,22.

According to EPE case studies based on reanalysis and numerical model simulations over the AP, EPEs can occur under specific conditions. For example, northwesterly and southwesterly winds from the northern and southern Red Sea, respectively, merge to form the Red Sea Convergence Zone in the central Red Sea, and interaction between the RST and extratropical storms favors the formation of strong mesoscale convective systems (MCS)13,17. Both events occasionally result in EPEs13,15,16,17,19,21,22,25. EPEs over the AP are also linked to meridionally trapped and zonally elongated low-frequency disturbances in the vicinity of the subtropical jet stream [also called the Circumglobal wave-train (CGT); Atif et al.26] and to mid-latitude storms14,27,28. However, the understanding of these synoptic and large-scale systems causing EPEs under global climate change has received little attention.

This study examines the impact of increasing anthropogenic emissions on EPEs over the AP and the associated synoptic and large-scale circulations. To this end, it conducts a composite anomaly analysis based on historical and future climate-model simulations with multiple climate variables. Section 2 presents and discusses the results, Section 3 concludes the paper, and Section 4 of this paper describes the data and methodology of the study.

Results

Historical and Future EPEs over the AP

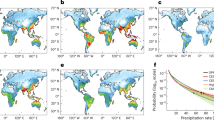

Figure 1 shows the cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) of precipitation over the AP during the 1985–2014 wet season, derived from the Red Sea Reanalysis (RSRA), Multi-source Weather (MSWX) data, and CMIP6 models. In both the RSRA and MSWX data, 70% of the rainfall records over the AP correspond to non-wet days. In the remaining 30% of the records attributed to wet days, the rainfall is usually below 10 mm (Fig. 1a). More specifically, the proportions of wet days with rainfalls of 1–5 mm, 5–10 mm, and >10 mm are 21%, 4.5%, and 4.5%, respectively (Fig. 1a). As the CDFs derived from the RSRA and MSWX datasets are very similar, the RSRA was adopted as the reference precipitation dataset in this study. On average, approximately 18% of the simulated rainfall records are wet (Fig. 1a), with 13%, 2.5%, and only 2% in the rainfall ranges of 1–5 mm, 5–10 mm, and >10 mm, respectively (Fig. 1a). Therefore, a drizzle-like bias exists in most CMIP6 models, as observed in previous CMIP phases29,30,31,32.

CDFs for (a) all precipitation records and (b) wet-day precipitation records across various precipitation bins (mm/day) over the AP during the historical wet season (1985–2014). In panel (a), the vertical dashed line marks the threshold for wet days. In panel (b), the vertical solid and dashed lines indicate the 99th percentile (R99p) and 95th percentile (R95p), respectively, for the CMIP6 multimodel mean (CMIP6–MMM; red), RS-R (also called RSRA in black), and MSWX (gray). The horizontal gray solid and dashed lines show the 99% and 95% CDFs, respectively. The colored curves represents the CDFs of individual models (as labeled on the right).

Based on the precipitation CDFs on wet days over the AP, the R95p and R99p thresholds of RSRA were determined as 18 and 36 mm, respectively (Fig. 1b). The occurrences of R95p EPEs from RSRA are highest along the coastal Red Sea and Arabian Gulf and over the southwest and interior AP, where approximately 30 events occurred in 30 years (Fig. 2a). In contrast, regions such as Rub’ al Khali and the northernmost AP experienced only around 6–8 EPEs in 30 years. These regions with high and low R95p EPE occurrences are associated with high and low wet-season rainfall, respectively (e.g., Abdullah and Almazroui11; De Vries et al.15,22; Dasari et al.14). The R95p EPEs from the CMIP6 multi-model mean (CMIP6–MMM) show a comparable pattern across the AP, with a correlation of 0.75 against the RSRA, but exhibit systematic biases, particularly over regions with relatively more frequent EPEs (Fig. 2b, c). These EPE biases are likely caused by the underestimation of heavy rainfall days in the CMIP6 models (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1).

Spatial maps of total extreme events during the wet season (1985–2014) based on the R95p threshold for (a) RSRA (RS-R) and (b) CMIP6–MMM. Panel (c) shows the bias in total extreme events between CMIP6–MMM and RSRA. Panels (d–f) and (g–i) show projected percentage changes in extreme events for the near-future (2021–2050) and far-future (2070–2099), respectively, under three climate scenarios (SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5). A backward slash \((\backslash )\) indicates significant changes/biases at the 95% confidence level based on a two-tailed Student’s t-test. A forward slash \((/)\) indicates that at least 60% of the CMIP6 models agree on the sign of the changes/biases. Hatches marks area where both conditions (backward and forward slash) are met, indicating robust change/bias regions.

Assuming that biases in the CMIP6 model will persist in future climate simulations, we estimated the projected changes in the R95p EPEs for CMIP6-MMM under three shared socioeconomic pathway (SSP) scenarios (SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5) during the near-future (2021–2050) and far-future (2070–2099) (Fig. 2d–i). Although all SSPs predicted increasing/decreasing EPE patterns in the near-future, the higher emission scenarios predicted a wider area of increasing patterns than the other scenarios (Fig. 2d–f). The R95p EPEs over the AP are projected to decrease up to 20% from their current level in some patches while increasing by 20–50% (depending on emissions level) over a wider area. The area of increased EPEs is expected to further expand in the far future, reaching 70% over the northwest AP and Rub’ al Khali (SSP2-4.5) and 100% over the northwest, southeast and southwest AP (SSP5-8.5) (Fig. 2g–i). Notably, the changes reported for CMIP6-MMM align closely with those obtained from the multi-model mean of the NASA Earth Exchange Global Daily Statistically Downscaled CMIP6 Projections33 (NEX-GDDP-MMM), supporting CMIP6-MMM changes. NEX-GDDP-MMM indicates a ~50% increase in EPEs during the near future and an over 100% increase in the far future under SSP5-8.5 (Fig. 3). Aside from small pockets along the coastal Red Sea and the northern AP exhibiting minor decreases, the rest of the region shows more substantial increases compared to CMIP6-MMM (Fig. 2d-f and Fig. 3d-f). These patterns persist across all scenarios, with SSP5-8.5 showing the highest increases, while the other scenarios display similar trends but with slightly lower magnitudes than SSP5-8.5. A recent observational study reported a decreasing trend in frequency but an increasing trend in the intensity of EPEs over Jeddah, located on the Red Sea coast17. This change is potentially linked to urbanization in the area18.

Spatial maps of total extreme events during the wet season (1985–2014) based on the R95p threshold for (a) RSRA (RS-R) and (b) NEX-GDDP–MMM. Panel (c) shows the bias in total extreme events between NEX-GDDP–MMM and RSRA. Panels (d–f) and (g–i) show projected percentage changes in extreme events for the near-future (2021–2050) and far-future (2070–2099), respectively, under three climate scenarios (SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5). A backward slash \(({\rm{\backslash }})\) indicates significant changes/biases at the 95% confidence level based on a two-tailed Student’s t-test. A forward slash \((/)\) indicates that at least 60% of the NEX-GDDP models agree on the sign of the changes/biases. Hatches marks area where both conditions (backward and forward slash) are met, indicating robust change/bias regions.

Rarer events (i.e., R99p EPEs) exhibited a similar pattern to R95p EPEs, with occurring four events over most of the AP and approximately 10–20 events over the coastal Red Sea and Arabian Gulf regions over 30 years (Supplementary Fig. 2). Like R95p, the spatial patterns of the R99p EPEs in the CMIP6–MMM are comparable to those of RSRA (correlation = 0.60), showing a bias in the order of the mean. Future projections indicate a higher increase rate of R99p EPEs, potentially exceeding the current level by more than 200% in SSP5-8.5. This finding is in line with previous research suggesting that increasing anthropogenic emissions will increase the frequency of rare events in future (e.g., Masson-Delmotte et al.1; Gründemann et al.34).

To better interpret these changes in the context of warming, we normalized the projected changes in EPEs by the surface air temperature increases during the same period. For R95p extremes, we found a ~ 20% increase per oC rise in surface temperature by the end of the century, while for R99p extremes, the increase was ~50% per oC under SSP5-8.5 (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4). To put it in perspective, the Clausius–Clapeyron (CC) scaling hypothesis posits that rising temperatures enhance the atmosphere’s moisture-holding capacity, leading to more intense precipitation events35,36. The projected 20% to 50% per oC increase in the intensity of future extreme events (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4) actually exceeds the CC-scaling, and is consistent with the proposed super-CC relationship37,38,39. The concept of super-CC scaling suggests that the dynamic feedback between enhanced updrafts, latent heat release, and low-level moisture convergence plays a paramount role in generating precipitation rates that surpass those predicted by CC scaling. The broader applicability and limitations of CC and super-CC scaling for extremes over AP will be examined in a separate study due to their complexity.

Time-series Changes in EPE Frequency and Precipitation Contribution

Figure 4 shows the CMIP6–MMM historical and projected yearly changes in EPEs over the AP and its sub-regions under the highest-emission scenario (SSP5-8.5), relative to the historical mean of 1985–2014. The AP sub-regions (Fig. 4a) classified using wet-season rainfall variability and spatial rainfall autocorrelation-based clustering (e.g., Saikranthi et al.40), align with the identified homogenous regions in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA)41. Over time, both the R95p and R99p EPEs gradually increased over the whole AP, including the KSA and the six sub-regions (Fig. 4b, c). The CMIP6-simulated historical variation of EPE changes over the AP resembles that of the RSRA, inspiring confidence in the projected trend (Supplementary Fig. 5). However, the models deviate from the RSRA trends in specific periods, likely reflecting internal variabilities42.

Future changes in EPEs (%) relative to the historical mean (1985–2014) across the Arabian Peninsula (AP), the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), and six sub-regions (panel (a)) under the SSP5-8.5 scenario. The graphs display EPE changes in the CMIP6 models and RSRA (RS-R) at the thresholds of (b) R95p and (c) R99p. The sub-regions are defined based on wet-season rainfall variability and spatial rainfall autocorrelation, closely aligning with homogeneous regions in the KSA identified by Almazroui et al.41 using a principal component analysis with multiple variables. The six subregions of the AP are as follows: Northern (NTH), Interior (INT), Southwest (SW), Central South (CSTH), Empty Quarter (EMQ), and Eastern (EST). The curves in panels (b) and (c) represent the multi-model means of projected changes from the historical average (1985–2014), smoothed using a 10-year running average. The shaded area around each curve indicates the likely range (half deviation) of projected changes in the corresponding CMIP6 model. The black dashed line shows the historical change in RSRA.

The rare events (R99p EPEs) are increasing at a faster yearly rate than the less intense rainfall events (R95p EPEs) (Fig. 4c). By the end of the 21st century, the R95 EPEs are projected to increase by approximately 50% over most AP regions while the R99p EPEs will increase by over 100%, reaching up to 200% in some regions. The most substantial trends are projected in the southwest, empty quarter, and central south, where the R95p EPEs and R99p EPEs are expected to increase by 50–100% and 100–200%, respectively (Fig. 4b, c). Although they follow the CMIP6–MMM changes, the CMIP6 models show a wide range of inter-model uncertainty in the R95p and R99p EPE projections, which increase over time. This inter-model spread in the simulated precipitation highlights the need for further enhancement of the models (e.g., Almazroui et al.43; Masson-Delmotte et al.1; Pathak et al.44).

Figure 5 shows the contribution of EPEs to the wet-season rainfall under the SSP5-8.5 scenario. During the historical period, the CMIP6–MMM overestimated the contribution of low rainfall events and underestimated the contribution of intense rainfall events from those of RSRA. In CMIP6–MMM and RSRA, rainfall events below 5 mm contributed 40% and 50%, respectively, those between 10 and 20 mm contributed 22% and 17%, respectively, and those between 20 and 40 mm contributed 14% and 8%, respectively. Rainfall events between 5 and 10 mm contributed 20% in both models. Extreme events (rainfall above 40 mm) contributed 5% in RSRA but only 2% in CMIP6–MMM (Fig. 5b). That is, CMIP6 models tend to overestimate and underestimate low and heavy rainfall events, respectively, as also reflected in their probability distribution function over the AP. SSP5-8.5 predicts that in the far future, the EPE contributions from 20–40 mm and >40 mm intense-rainfall events over the AP will increase by approximately 30% and 125%, respectively, from their current levels. Conversely, contributions from low-rainfall events are projected to decrease by approximately 12%. Significant increases in the contributions of intense rainfall events are also expected in regions. The projected increases of events with over 40 mm of rainfall are 150% in the southwest, 125% in the north, and 100% in the central southern AP (Fig. 5c). In the far future, the contributions of 20–40 mm events will increase by 25–50% across various regions, whereas those of low-rainfall events are projected to decrease by 10–20% from their current levels in these regions (Fig. 5c). Specifically, in the KSA (which accounts for 80% of the AP area), the expected increases of >40 mm and 20–40 mm events are 85% and 30%, respectively, while low rainfall events (<5 mm) will likely decrease by 12%. The likely ranges of these changes, indicated by inter-model uncertainty, are also large, especially for higher extremes (Fig. 4c). However, compared to the historical period, the uncertainty in projections for heavy rainfall events (>40 mm) decreases in the far future. In particular, for smaller events (<20 mm), the ratio of inter-model uncertainty to the mean remains around 10% across different periods. While for heavier events (>40 mm), this ratio decreases from approximately 45% in the historical period to 30% in the far-future SSP5-8.5 scenario, suggesting for most models to consistently project more frequent and intense EPEs under future warming (Supplementary Fig. 6).

a Intensity variations of different rainfall percentiles during the historical wet season (1985–2014) over the AP, as observed in RSRA (OBS-HIST) and CMIP6–MMM. This include projections for the near-future (2021–2050) and far-future (2070–2099) periods. b Historical and future variations in extreme rainfall contributions across different rainfall bins, relative to the total wet-season rainfall over the AP, as obtained by RSRA and CMIP6–MMM. c Projected far-future changes in rainfall contributions across different rainfall bins, relative to the total wet season rainfall, for the Whole AP, the KSA, and six sub-regions.

Besides increasing in frequency and percentage contribution, EPEs are expected to increase in intensity (Fig. 5a). The EPEs at thresholds of R95p, R99p, and R99.9p are projected to intensify by 20–30% in the far future, with higher intensity changes at higher percentiles (Fig. 5a). The increases in frequency and intensity of EPEs are projected to substantially contribute to the 50–60% expected increase in mean annual rainfall under the SSP5-8.5 scenario by the end of the 21st century43.

Historical Mean Large-scale Circulation Characteristics

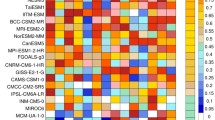

To investigate the dominant large-scale circulations causing EPEs over the AP and the responses of these circulations to precipitation changes, we first analyzed the historical mean wet-season circulations, then performed historical and far-future composite analyses of the R95p EPEs under the high-emission scenario. The MRI-ESM2-0 model, which best simulated the EPEs and precipitation seasonality over the AP (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 7–10), was employed in this analysis. The MRI-ESM2-0 model adequately reproduces the historical circulation patterns of ERA5 and aligns well with those from CMIP6–MMM (Supplementary Fig. 11, 12). Consequently, the model is well suited for revealing both the historical and future circulation patterns during EPEs. This analysis focuses on the wet-season EPEs over the interior of the AP (IAP), which receives over 90% of the annual precipitation over the whole AP (Supplementary Fig. 10). The number of EPEs in the IAP is surpassed only in the southwest region, which receives both EPEs and substantial rainfall during the summer season, in addition to the wet season (Fig. 2). This region will be the focus of further investigation in subsequent studies.

Importantly, during the historical period, the low-level wind patterns at 850 hPa show two anticyclonic circulations: one over the Africa and another over the AP adjoining the Arabian Sea (Fig. 6a). The northwesterly and southwesterly winds merge to form the RST, a low-pressure zone between the two anticyclonic circulations that converges over the central Red Sea and the adjoining AP (Fig. 6a). As shown in the upper-level wind patterns at 200 hPa, the SWJ traverses the AP at approximately 45 m/s (Fig. 6b, c). Acting as a waveguide of westerly disturbances, the STJ is a crucial precipitation generator in the region14,28,45,46. Its position is identified by extracting the maximum zonal wind velocity between 10°N and 40° N at all longitudes from 20°E to 70°E. The low-level vertical wind at 850 hPa shows subsidence over most desert areas and patches of ascent over the interior, southwest, and western mountainous regions of the AP (Fig. 6b).

b Vertical wind at 850 hPa overlaid with 200 hPa horizontal wind vectors. c The 200 hPa zonal wind component, with the black line indicating the core position of the subtropical jet (STJ). Panels (d–f) show composite anomalies during historical extreme events, while (g–i) depict anomalies during far-future extreme events (2070–2099). The STJ position was determined by extracting the maximum wind velocity between latitude bands 10°N and 40°N at all longitudes from 0°E to 80°E (see Attada et al.45). The black, blue, and purple lines in panels (c), (f), and (i) indicate the core STJ positions during the historical mean wet period, historical extreme precipitation event (EPE) days, and far-future EPE days, respectively.

Historical EPE Composites

The composite anomalies of low-level wind (Fig. 6d) show an anomalous cyclonic circulation over the AP (Fig. 6d) that advects moisture from nearby water bodies into the AP (Fig. 7b, h). This cyclonic circulation coincides with an area of anomalously low SLP extending the RST from the southwest to northeast AP (Fig. 6d). Together with the anomalous cyclonic circulation, the SLP draws warm moist air from the Red Sea, the Arabian Sea, the Arabian Gulf, and the eastern Mediterranean Sea during an EPE21,22,26,27.

(a–c) Contours of total precipitable water from surface to 400 hPa, overlaid with wind patterns at 1000 hPa: (a) climatological mean conditions during the wet season, (b) composite anomalies of historical EPEs, and (c) composite anomalies of far-future EPEs. The second row (d–f) presents results from meridional wind at 200 hPa; third row (g–i) shows integrated moisture convergence from 1000 to 400 hPa; and the fourth row (j–l) depicts potential vorticity. In the moisture convergence plots (g–i), contours are overlaid with wind vectors illustrating integrated horizontal moisture advection.

These dynamic mechanisms are strongly complemented by thermodynamic factors, which paly a critical role in enhancing upward motion during EPEs47. The composite anomalies of moist static energy (MSE) in historical EPEs show positive value over the AP, primarily confined to the lower troposphere (Supplementary Fig. 13). This localized increase in MSE corresponds to a favorable environment for instability and convection, driving upward motion. Specific humidity anomalies further enhance this effect, with positive anomalies over the AP and surrounding water bodies supplying abundant moisture (Supplementary Fig. 14). This moisture fuels latent heat release during convection, which directly reinforces upward motion (Supplementary Fig. 15). The composite anomaly of low-level vertical velocity highlight these effects, showing upward motion extending to mid-tropospheric levels (Fig. 6e). The thermodynamic contributions of increased MSE, humidity, and relatively more warmed mid-troposphere amplify this dynamical lifting, making it important for generating extreme precipitation45.

The composite anomalies of upper-level wind indicate a southward shift of the STJ from its normal position during an EPE (Fig. 6f). This southward shift induces baroclinicity and increases the frequency of transient passages and hence the moisture flux entering the IAP from adjacent seas, leading to extreme rainfall14,27. The number of transient activity occurrences over the IAP also increases during EPEs (Supplementary Fig. 16, 17). The STJ shift can generate a vorticity source for Rossby wave formation, forming a low-level local vorticity46 that assists the uplift of high-moisture flux from the surrounding seas48. The low-level cyclonic circulation anomaly during EPEs in the IAP features an upper-level cyclonic anomaly with a slightly westward-shifted center from that of the low level (Fig. 6d, e). In addition, a wave-like pattern in the meridional wind composite anomaly at 200 hPa in the mid-latitude region (Fig. 7e), which is recognized as a CGT, extends eastward from the North Atlantic Ocean toward Europe and South Asia, where it likely affects the regional precipitation49,50. The CGT pattern can modulate mid-latitude storms51 and brings cold air in the upper troposphere over the AP during the wet season, facilitating upper air divergence through the jet stream and helping to develop the MCSs, as discussed by Branstator49.

The vertically integrated moisture transport (VIMT) composite-anomaly analysis of the historical EPEs reveals that moisture flux is primarily transported from the Red Sea and Arabian Sea (Fig. 7h). The Arabian Anticyclone transfers moisture from these water bodies to the IAP. Meanwhile, westerly winds transport substantial amounts of moisture from the eastern Mediterranean to the north–central AP. Past studies have associated upper-level cyclonic circulation and anticyclonic circulation with enhanced and suppressed potential vorticity, respectively23,52,53,54. The strong flow induced by the synoptic-scale upper-level potential vorticity can generate cyclonic circulation at lower levels. During EPEs, the 300-hPa potential vorticity composite shows an equatorward intrusion of higher potential vorticity air (>1 potential vorticity unit or 1 × 10−6 km2/kg/s) from northern latitudes toward the AP, promoting moist convection development (Fig. 7k). Such high PV intrusions are tied to Rossby wave-breaking activities15,46. The southward intrusion of high potential vorticity reduces the atmospheric static stability, inducing further convection55 that favors EPE occurrences. The RST is accompanied by an upper tropospheric trough that destabilizes the atmosphere, leading to MCS development over the region15,17,22. The development of such a system is evidenced by the strong negative OLR anomalies (Supplementary Fig. 18b) and positive total cloud fraction anomalies (Supplementary Fig. 18e) over the IAP. These mechanisms drive EPEs over the IAP, causing an average rainfall of approximately 10 mm across most of the AP with maxima centered over the IAP (Supplementary Fig. 18h).

Far-Future EPE Composites

The projected far-future EPE composite anomalies show notable changes, and circulation shifts from those of the historical EPEs. The STJ, a crucial driver of precipitation in the region, is projected to shift slightly further southward and strengthen over the AP (Fig. 6i). This strengthening is consistent with Hunt (2024), who reported that STJ intensification would increase the westerly disturbances. As the STJ strengthens, the baroclinicity increases and transient passages become more frequent, enhancing the moisture flux into the IAP from adjacent seas and intensifying the rainfall (Fig. 7c, i). Future transient activity over the AP, including the IAP, is projected to increase from that of historical EPEs (Supplementary Fig. 16). The CGT pattern that modulates mid-latitude storms is weakening in the Atlantic Ocean but strengthening over Europe and the Middle East, also consistent with faster transient-activity passages and the southward-shifted and strengthened STJ27.

The far-future vertical wind ascent covers a larger area than in the historical period (Fig. 6h), indicating that the extent of dynamical lifting and amount of potential instability will increase in future26,45. This is evident from relatively large increases in MSE (Supplementary Fig. 13), humidity, and steepened lapse rate in the troposphere (Supplementary Fig. 14, 15), enhancing vertical ascent and causing increased convective activities and more frequent EPEs. A slight strengthening of the upper-level cyclonic anomaly is also expected (Fig. 6h), but the low-level cyclonic anomaly should remain similar to the historical anomaly apart from a low-pressure enhancement over the western Arabian Sea and RST (Fig. 6g). An enhanced high-pressure anomaly and anticyclonic circulation wind anomaly are projected over a larger area on the northern side of the AP, covering Europe to central Asia. This anticyclonic circulation wind anomaly is an extension of the Arabian and African Anticyclone, which moves northward and merge. The enhanced low SLP anomaly and the increased north–south SLP gradient will probably enhance the moisture transport from the Red Sea and Arabian Sea into the AP, and from the Mediterranean Sea through the northwesterly wind (Figs. 5g, h and 6c, i). The far-future VIMT composite indicates a substantial increase in moisture convergence over the IAP, with increased moisture transport from the Red Sea, Arabian Gulf, and eastern Mediterranean (Fig. 6i).

Furthermore, the negative OLR composite anomalies over the IAP in the historical EPEs are projected to expand in the far-future, suggesting heightened instability and a strengthened MCS (Supplementary Fig. 18c). The increased instability coincides with the projected widespread anomalous precipitation over the AP from EPEs (Supplementary Fig. 18i), which is maximized near the Arabian Gulf. A substantial increase in precipitable water is expected in the far future EPEs, potentially doubling from that in the historical EPEs (Fig. 7c). This increase suggests a higher atmospheric moisture content driven by increased local convection in a warmer world.

Overall, the atmosphere of the AP will likely become more dynamic and moisture-laden in the far-future, leading to more intense and widespread EPEs over the AP, particularly in the IAP region.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study examined the historical and future projections of EPEs across the AP, explaining the complex relationship between the atmospheric dynamics and climate change. Historical data indicate that 15CMIP6 models exhibit spatiotemporal EPE patterns comparable to observations/reanalysis, making them useful for projecting future trends. Notably, the CMIP6–MMM and MRI-ESM2-0 model well simulated the EPEs and precipitation seasonality over the AP.

Future projections indicate that increasing anthropogenic emissions will significantly increase both the frequency and intensity of EPEs across the AP. Under the SSP5-8.5 scenario, the EPE frequency in certain regions of the AP is expected to rise to 100% from its current levels. These projected changes are closely linked to shifts in atmospheric circulations driven by increasing global temperatures.

The STJ is projected to strengthen and shift southward, increasing the transient activity and moisture flux into the AP and thereby enhancing the baroclinicity and promoting extreme rainfall. The low-pressure anomaly over the Red Sea and Arabian Sea is projected to further increase, drawing additional moisture into the AP. Meanwhile, a low-level anticyclonic anomaly associated with a large positive SLP anomaly, extending from Europe to central Asia, is expected to be positioned northward to the northern AP in the far future. This anomaly would enhance moisture transport from the Mediterranean Sea and increase precipitation over the AP. Supporting the increased likelihood of convective activities and EPEs, the projected expansion of the vertical wind ascent regions implies more extensive dynamical lifting and potential instability than at present. The frequency of future EPEs is expected to be further favored by increases in horizontal moisture advection from the Red Sea, Arabian Sea and Arabian Gulf, which will increase moisture convergence over the AP, particularly in the interior region. Meanwhile, strengthened upper-level cyclonic anomalies over the AP will facilitate the development of MCSs, contributing to more intense and widespread EPE effects.

Overall, this study sheds light on the complex dynamics driving EPEs over the AP and the consequences of climate change on regional precipitation patterns. Further research is essential to deepen our understanding of these mechanisms and enhance the reliability of future projections, ultimately supporting effective climate adaptation and mitigation strategies in response to increasing precipitation extremes in the AP.

Data and Methods

Data

This study uses the daily precipitation datasets of the Multi-Source Weather (MSWX Beck et al. 56) and Red Sea reanalysis (RSRA; Dasari et al.57,58) over the historical period 1985–2014. MSWX provides high-resolution (0.1°) bias-corrected European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts Reanalysis version 5 (ERA5) data56, whereas RSRA is generated using a high-resolution (5 km) assimilative configuration of the Weather Research and Forecasting model. Importantly, the MSWX data are highly correlated with the averages of all available global rainfall datasets (see Pathak et al.44) and the RSRA data are highly correlated with local observations57,58. Additional daily historical fields such as the horizontal wind, mean sea level pressure (SLP), outgoing longwave radiation (OLR), geopotential heights, temperature, and specific humidity at 0.5° resolution, are also available from ERA5 data59.

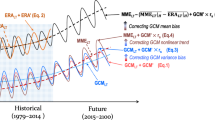

To determine the impact of climate change on EPEs over the AP, we analyzed the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6; Eyring et al.60) datasets over the historical (1985–2014) and future (2015–2100) periods under three emissions scenarios: a high-emissions/business-as-usual scenario (Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) 5-8.5), a medium-level emissions scenario (SSP2-4.5), and a low-emissions/sustainability scenario (SSP1-2.6). The design of the emission scenarios in future climate model simulations is detailed in O’Neill et al.61. Before employing the CMIP6 datasets, we compared the performances of 37 CMIP6 models for 27 climate variables (see Supplementary Material and Supplementary Fig. 19). Based on the relative performance and model independence ranks (see Pathak et al.44,62), we selected the 15 CMIP6 (15CMIP6) models for EPE analysis (Table 1). All 15CMIP6 models, RSRA and MSWX outputs are regridded to a common 0.5° in latitude and longitude using bilinear interpolation.

Method for Defining the EPEs

EPEs have been variously defined using percentiles, fixed thresholds, and standardized anomalies (e.g., Peterson et al.63; WMO64; Donat et al.65; Luong et al.17,18,19; Atif et al.26; Attada et al.45). However, a universal definition of EPEs in arid/semi-arid regions such as the AP is currently lacking.

In this study, we define EPEs in terms of percentile-based thresholds determined from the wet/day precipitation distributions. The 95th percentile threshold is set for very wet days (R95p EPE) and the 99th percentile for extremely wet days (R99p EPE). Days on which the rainfall reaches at least 1 mm are classified as wet days65. This methodology, recommended by the Expert Team on Climate Change Detection and Indices of the World Climate Research Programme63, has been widely employed in several climate extreme studies (e.g., Donat et al.65; AlSarmi and Washington66). To find the R95p and R99p thresholds at all grid points over the AP, we adopted a similar approach to that of Atif et al.26. Specifically, we binned the historical daily wet-day precipitation data at each grid point and combined the frequencies in each bin size. Subsequently, the percentage of precipitation events in each bin was calculated relative to the total precipitation events in all bins (Fig. 1). The threshold defining an EPE over the AP was then determined based on the R95p and R99p (Fig.1). To standardize the threshold across various CMIP6 models, the EPEs in the individual models were also determined from the R95p and R99p thresholds of the RSRA data (Fig. 1).

Method for Composite Analysis

To investigate the synoptic and large-scale atmospheric conditions during EPEs over the AP, we conducted a composite analysis with various climate variables: meridional wind (V) and zonal wind (U) in the low-level (850 hPa) and upper-level (200 hPa) atmosphere, the geopotential heights at 500 and 200 hPa, mean SLP, outgoing longwave radiation (OLR), vertically integrated precipitable water, and vertically integrated moisture transport (VIMT). The EPE composites were averaged over all EPE days, whereas the EPE composite anomalies were determined as the difference between the averages of the EPE days and all days over the considered period, as follows:

Here, n represent the total number of EPE days, m denotes the total number of days during the considered period, and X signifies the variable of interest. All computed composite anomalies in this study, for both historical and future EPEs, were compared with respect to the historical mean pattern (i.e., over all historical days).

Method for Estimating Moisture Transport

The anomalous distribution of precipitation is significantly influenced by the VIMT67,68. According to Zolina et al.68, the interannual variability in the VIMT from the Red Sea affects the precipitation pattern over the AP and surrounding African regions. Convective and frontal activities are also strongly associated with the VIMT69. Given these associations, we estimated the VIMT as follows:

where VIMT represents the horizontal moisture flux integrated from the surface to 400 hPa, \({\nabla }_{p}\) denotes the horizontal divergence in pressure cordinates, \({\boldsymbol{u}}=(u,v)\) represents the horizontal wind vector, and \(q\) signifies the specific humidity. \({{VIMT}}_{u}\) and \({{VIMT}}_{v}\) are the vertically integrated zonal and meridional moisture fluxes, respectively. Positive and negative VIMT values indicate positive and negative precipitation, respectively.

Association With Large-scale Forcing

As demonstrated in numerous studies, upper-tropospheric circulation anomalies significantly influence the winter precipitation over the AP13,14,15,17,19,45. These anomalies are linked to the subtropical westerly jet (SWJ), which intensifies during frequent mid-latitude transient passages over the region, thereby increasing precipitation over the AP14,27. Here, we analyzed the upper-level circulation patterns during the wet season. The transient activity during the wet season was calculated in terms of the root-mean-squared (RMS) synoptic transients (2–8-day filtered 200-hPa geopotential height, e.g., Kang et al.27; Dasari et al.14). In addition, we assessed the persistence of the upper-atmospheric large-scale CGT using the meridional wind composites (see Atif et al.26).

Statistical Analysis

We used a two-tailed Student’s t-test at a 95% confidence level. Significant changes are denoted by a backward slash (\) in the figures, indicating areas where mean changes between the projected and historical model data are statistically significant. Additionally, we evaluate biases during the historical period by comparing model outputs with observational data using the same t-test methodology, also represented by a backward slash.

We quantify model agreement by analyzing the sign of the projected changes, where a forward slash (/) indicates that at least 60% of the CMIP6 models concur on the direction of change. Areas marked with hatches signify regions where both statistical significance (backward slash) and model agreement (forward slash) conditions are met, highlighting robust change regions.

This comprehensive dual-criteria approach enhances confidence in the identified changes and provides critical insights into the impacts of climate change on EPEs in the AP. Our methodology aligns with the findings of Masson-Delmotte et al.1 and Almazroui et al.43, which emphasize the necessity of utilizing rigorous statistical analyses and model consensus to derive reliable climate projections.

Data availability

In this study, the climate model datasets used are publicly accessible through the Center for Environmental Data Analysis at https://data.ceda.ac.uk/badc. Detailed insights into the outputs of these climate models can be found in Eyring et al.34. Additionally, various reanalysis/observational datasets used in this study are available at the ECMWF Copernicus Climate Change Service website: https://www.ecmwf.int/en/forecasts/dataset/ecmwf-reanalysis-v5 and Red Sea Reanalysis at KAUST Climate Change Center website: https://assimilation.kaust.edu.sa/. NASA Earth Exchange Global Daily Downscaled Projections (NEX-GDDP), are publicly available at https://www.nccs.nasa.gov/services/data-collections/land-based-products/nex-gddp-cmip6. Additional information regarding the data related to this paper can be obtained from the corresponding author.

Code availability

The code used to generate the figures and compute statistics in this study is available upon request. Interested individuals can obtain access by contacting Ibrahim Hoteit at ibrahim.hoteit@kaust.edu.sa.

References

Masson-Delmotte, V. et al. Summary for Policymakers. Climate Change 2021—The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2021a).

Min, S.-K. et al. Human contribution to more-intense precipitation extremes. Nature 470, 378–381 (2011).

Westra, S., Alexander, L. V. & Zwiers, F. W. Global increasing trends in annual maximum daily precipitation. J. Clim. 26, 3904–3918 (2013).

Oduoye, M. O. et al. Flooding in Libya amid an economic crisis: what went wrong? IJS Glob. Health 7, e0401 (2024).

Sharma, A. & Lekhi, R. Record monsoon rains kill more than 100 people in northern India. The Los Angeles Times, 13 July 2023. Retrieved 17 August 2023.

Allan, R. P. et al. Current changes in tropical precipitation. Environ. Res. Lett. 5, 025205 (2010).

Seneviratne, S. I. et al. Changes in climate extremes and their impacts on the natural physical environment. In: Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation [Field, C. B., V. Barros, T. F. Stocker, D. Qin, D. J. Dokken, K. L. Ebi, M. D. Mastrandrea, K. J. Mach, G.-K. Plattner, S. K. Allen, M. Tignor, and P. M. Midgley (eds.)]. A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, and New York, NY, USA, pp. 109-230 (2012).

Rao, K. K. et al. Future changes in the precipitation regime over the Arabian Peninsula with special emphasis on UAE: insights from NEX-GDDP CMIP6 model simulations. Sci. Rep. 14, 151 (2024).

Amin, M. T., Mahmoud, S. H. & Alazba, A. A. Observations, projections and impacts of climate change on water resources in Arabian Peninsula: current and future scenarios. Environ. Earth Sci. 75, 1–17 (2016).

Patlakas, P., Stathopoulos, C., Flocas, H., Kalogeri, C. & Kallos, G. Regional climatic features of the Arabian Peninsula. Atmosphere 10, 220 (2019).

Abdullah, M. A. & Al-Mazroui, M. A. Climatological study of the southwestern region of Saudi Arabia. I. Rainfall analysis. Clim. Res. 9, 213–223 (1998).

Hasanean, H. & Almazroui, M. Rainfall: features and variations over Saudi Arabia, a review. Climate 3, 578–626 (2015).

Dasari, H. P., Attada, R., Knio, O. & Hoteit, I. Analysis of a severe weather event over Mecca, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, using observations and high‐resolution modelling. Meteorological Appl. 24, 612–627 (2017).

Dasari, H. P. et al. Long-term changes in the Arabian Peninsula rainfall and their relationship with the ENSO signals in the tropical Indo-Pacific. Clim. Dyn. 59, 1–17 (2021).

De Vries, A. J. et al. Identification of tropical‐extratropical interactions and extreme precipitation events in the Middle East based on potential vorticity and moisture transport. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 123, 861–881 (2018).

Haggag, M., & El-Badry, H. Mesoscale numerical study of quasi-stationary convective system over Jeddah in November 2009. Atmospheric and Climate Sciences 3, (2013).

Luong, T. M., Dasari, H. P. & Hoteit, I. Extreme precipitation events are becoming less frequent but more intense over Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Are shifting weather regimes the cause? Atmos. Sci. Lett. 21, e981 (2020a).

Luong, T. M., Dasari, H. P. & Hoteit, I. Impact of urbanization on the simulation of extreme rainfall in the city of Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. J. Appl. Meteorol. Climatol. 59, 953–971 (2020b).

Luong, T. M., Dasari, H. P., Doan, Q., Alduwais, A. K., & Hoteit, I. Organized precipitation and associated large-scale circulation patterns over the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. International Journal of Climatology 44, (2024).

Mohamed, H. UAE witnesses largest rainfall in 75 years. https://www.wam.ae/en/article/13vbuq9-uae-witnesses-largest-rainfall-over-past-years (2024)

Almazroui, M., Raju, P. V. S., Yusef, A., Hussein, M. A. A. & Omar, M. Simulation of extreme rainfall event of November 2009 over Jeddah, Saudi Arabia: the explicit role of topography and surface heating. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 132, 89–101 (2018).

de Vries, A. J. et al. Extreme precipitation events in the Middle East: dynamics of the Active Red Sea Trough. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 118, 7087–7108 (2013).

Rodwell, M. J. & Hoskins, B. J. Monsoons and the dynamics of deserts. Q. J. R. Meteorological Soc. 122, 1385–1404 (1996).

Simpson, I. R., Seager, R., Shaw, T. A. & Ting, M. Mediterranean summer climate and the importance of Middle East topography. J. Clim. 28, 1977–1996 (2015).

Deng, L., McCabe, M. F., Stenchikov, G., Evans, J. P. & Kucera, P. A. Simulation of flash-flood-producing storm events in Saudi Arabia using the weather research and forecasting model. J. Hydrometeorol. 16, 615–630 (2015).

Atif, R. M. et al. Extreme precipitation events over Saudi Arabia during the wet season and their associated teleconnections. Atmos. Res. 231, 104655 (2020).

Kang, I. S., Rashid, I. U., Kucharski, F., Almazroui, M. & Alkhalaf, A. K. Multidecadal changes in the relationship between ENSO and wet-season precipitation in the Arabian Peninsula. J. Clim. 28, 4743–4752 (2015).

Hunt, K. M., Turner, A. G. & Shaffrey, L. C. The evolution, seasonality and impacts of western disturbances. Q. J. R. Meteorological Soc. 144, 278–290 (2018).

Mishra, S. K., Sahany, S., Salunke, P., Kang, I. S. & Jain, S. Fidelity of CMIP5 multi-model mean in assessing Indian monsoon simulations. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 1, 39 (2018).

Pathak, R., Sahany, S. & Mishra, S. K. Impact of stochastic entrainment in the NCAR CAM deep convection parameterization on the simulation of South Asian summer monsoon. Clim. Dyn. 57, 3365–3384 (2021).

Kumar, R., Pathak, R., Sahany, S. & Mishra, S. K. Indian summer monsoon simulations in successive generations of the NCAR Community Atmosphere Model. Theor. Appl. Climatol. 153, 977–992 (2023).

Chen, D., Dai, A. & Hall, A. The convective‐to‐total precipitation ratio and the “drizzling” bias in climate models. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 126, e2020JD034198 (2021).

Thrasher, B. et al. NASA Global Daily Downscaled Projections, CMIP6. Sci. Data 9, 262 (2022).

Gründemann, G. J., van de Giesen, N., Brunner, L. & van der Ent, R. Rarest rainfall events will see the greatest relative increase in magnitude under future climate change. Commun. Earth Environ. 3, 235 (2022).

Trenberth, K. E., Dai, A., Rasmussen, R. M. & Parsons, D. B. The changing character of precipitation. Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 84, 1205–1218 (2003).

Utsumi, N., Seto, S., Kanae, S., Maeda, E. E., & Oki, T. Does higher surface temperature intensify extreme precipitation? Geophysical research letters, 38 (2011).

Berg, P., Moseley, C. & Haerter, J. O. Strong increase in convective precipitation in response to higher temperatures. Nat. Geosci. 6, 181–185 (2013).

Neelin, J. D. et al Precipitation extremes and water vapor: relationships in current climate and implications for climate change. Current Climate Change Reports, 8, 17-33 (2022)

Varghese, S. J. et al. Precipitation scaling in extreme rainfall events and the implications for future Indian monsoon: Analysis of high‐resolution global climate model simulations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2023GL105680 (2024).

Saikranthi, K., Rao, T. N., Rajeevan, M. & Rao, S. V. B. Identification and validation of homogeneous rainfall zones in India using correlation analysis. J. Hydrometeorol. 14, 304–317 (2013).

Almazroui, M., Dambul, R., Islam, M. N. & Jones, P. D. Principal components‐based regionalization of the Saudi Arabian climate. Int. J. Climatol. 35, 2555–2573 (2015).

Deser, C., Phillips, A. S., Bourdette, V. & Teng, H. Uncertainty in climate change projections: The role of internal variability. Clim. Dyn. 38, 527–546 (2012).

Almazroui, M., Islam, M. N., Saeed, S., Saeed, F. & Ismail, M. Future changes in climate over the Arabian Peninsula based on CMIP6 multimodel simulations. Earth Syst. Environ. 4, 611–630 (2020).

Pathak, R., Dasari, H. P., Ashok, K. & Hoteit, I. Effects of multi-observations uncertainty and models similarity on climate change projections. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 144 (2023).

Attada, R. et al. Diagnostic evaluation of extreme winter rainfall events over the Arabian Peninsula using high‐resolution weather research and forecasting simulations. Meteorological Appl. 29, e2095 (2022).

Niranjan Kumar, K., Ouarda, T. B., Sandeep, S. & Ajayamohan, R. S. Wintertime precipitation variability over the Arabian Peninsula and its relationship with ENSO in the CAM4 simulations. Clim. Dyn. 47, 2443–2454 (2016).

Seager, R., Naik, N. & Vecchi, G. A. Thermodynamic and dynamic mechanisms for large-scale changes in the hydrological cycle in response to global warming. J. Clim. 23, 4651–4668 (2010).

Chakraborty, A., Behera, S. K., Mujumdar, M., Ohba, R. & Yamagata, T. Diagnosis of tropospheric moisture over Saudi Arabia and influences of IOD and ENSO. Monthly Weather Rev. 134, 598–617 (2006).

Branstator, G. Circumglobal teleconnections, the jet stream waveguide, and the North Atlantic Oscillation. J. Clim. 15, 1893–1910 (2002).

Watanabe, M. Asian jet waveguide and a downstream extension of the North Atlantic Oscillation. J. Clim. 17, 4674–4691 (2004).

Wang, S. Y., Davies, R. E. & Gillies, R. R. Identification of extreme precipitation threat across midlatitude regions based on short‐wave circulations. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 118, 11–059 (2013).

Horan, M. F. et al. Moisture sources for precipitation variability over the Arabian Peninsula. Clim. Dyn. 61, 4793–4807 (2023).

Wilks, D. S. Statistical Methods in the Atmospheric Sciences. Elsevier https://doi.org/10.1016/c2017-0-03921-6 (2019).

IPCC, Annex II: Models [Gutiérrez, J M., A.-M. Tréguier (eds.)]. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 2087–2138, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.016. (2021)

Juckes, M. & Smith, R. K. Convective destabilization by upper‐level troughs. Q. J. R. Meteorological Soc. 126, 111–123 (2000).

Beck, H. E. et al. MSWX: global 3-hourly 0.1 bias-corrected meteorological data including near-real-time updates and forecast ensembles. Bull. Am. Meteorological Soc. 103, E710–E732 (2022).

Dasari, H. P. et al. High‐resolution climate characteristics of the Arabian Gulf based on a validated regional reanalysis. Meteorological Appl. 29, e2102 (2022).

Dasari, H. P. et al. High-resolution assessment of solar energy resources over the Arabian Peninsula. Appl. Energy 248, 354–371 (2019).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorological Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

O’Neill, B. C. et al. The scenario model intercomparison project (ScenarioMIP) for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 3461–3482 (2016).

Pathak, R., Sahany, S., Mishra, S. K. & Dash, S. K. Precipitation biases in CMIP5 models over the South Asian region. Sci. Rep. 9, 9589 (2019).

Peterson, T. C. & Manton, M. J. Monitoring changes in climate extremes: a tale of international collaboration. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 89, 1266–1271 (2008).

WMO. Guidelines on analysis of extremes in a changing climate in support of informed decisions for adaptation. World Meteorological Organization, 1500, 72 (2009)

Donat, M. G. et al. Updated analyses of temperature and precipitation extreme indices since the beginning of the twentieth century: The HadEX2 dataset. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 118, 2098–2118 (2013).

AlSarmi, S. H. & Washington, R. Changes in climate extremes in the Arabian Peninsula: analysis of daily data. Int. J. Climatol. 34, 1329–1345 (2014).

Gimeno, L. et al. Major mechanisms of atmospheric moisture transport and their role in extreme precipitation events. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 41, 117–141 (2016).

Zolina, O., Dufour, A., Gulev, S. K. & Stenchikov, G. Regional hydrological cycle over the Red Sea in ERA-Interim. J. Hydrometeorol. 18, 65–83 (2017).

Banacos, P. C. & Schultz, D. M. The use of moisture flux convergence in forecasting convective initiation: Historical and operational perspectives. Weather Forecast. 20, 351–366 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Program for Climate Model Diagnosis and Intercomparison for providing public access to CMIP model data. We also thank the supercomputing facility at King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST) for supporting data storage, fast computation, and analysis. Data processing and visualization were carried out using NCAR-NCL and MATLAB software. This research was funded by the the KAUST Climate Change Center and the Saudi ARAMCO Marine Environmental Research Center.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.P., K.A., and I.H. originated the project. All the authors contributed to the ideas and design of the research. R.P. wrote the first draft of the manuscript with inputs from I.H., A.K., and H.P.D. All the authors contributed to subsequent drafts.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pathak, R., Dasari, H.P., Ashok, K. et al. Dynamics of intensification of extreme precipitation events over the Arabian Peninsula derived from CMIP6 simulations. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 126 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01016-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01016-w