Abstract

Climate change in the Middle East has intensified with rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, and more frequent extreme events. This study introduces the Stacking-EML framework, which merges five machine learning models three meta-learners to predict maximum temperature, minimum temperature, and precipitation using CMIP6 data under SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5. The results indicate that Stacking-EML not only significantly improves prediction accuracy compared to individual models and traditional CMIP6 outputs but also enhances climate projections by integrating multiple ML models, offering more reliable, regionally refined forecasts. Findings show R² improvements to 0.99 for maximum temperature, 0.98 for minimum temperature, and 0.82 for precipitation. Under SSP5-8.5, summer temperatures in southern regions are expected to exceed 45 °C, exacerbating drought conditions due to reduced rainfall. Spatial analysis reveals that Saudi Arabia, Oman, Yemen, and Iran face the greatest heat and drought impacts, while Turkey and northern Iran may experience increased precipitation and flood risks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Climate change has become a paramount concern in the 21st century, profoundly impacting ecological systems, economic structures, and societal frameworks1. In this context, temperature and precipitation fluctuations significantly impact agricultural productivity2,3, oceanic acidification2,3, and occurrences of severe droughts4,5,6 or inondations7,8. This challenge is especially pronounced in areas like the Middle East, with distinctive geographical and climatic attributes. Recent studies have emphasized that this region’s rising temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns may engender considerable challenges, including depleted water resources, heightened health risks, and agricultural instability9,10,11. However, accurately predicting these changes and their impacts remains a formidable challenge due to the complexities of the climate system and the inherent uncertainties of climate modeling12,13,14. In this context, initiatives like the sixth phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6), which explores future climate scenarios, are critically important, yet they still face limitations in delivering precise regional forecasts15.

The CMIP6 signifies a noteworthy progression in global climate simulation, offering a comprehensive array of simulations that have deepened our understanding of climate behavior and forecasts across diverse socio-economic scenarios. Although previous experiments (i.e., CMIP3 and CMIP5 data) have been utilized in several studies16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24, recent regional evaluations have demonstrated that CMIP6 outputs have significantly improved compared to the earlier phases25,26,27. These improvements include elevated spatial resolution, more intricate physical representations, and an expanded array of scenarios, notably the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) that encapsulate various future trajectories of greenhouse gas emissions28. Additionally, CMIP6 has made significant strides in modeling complex climate feedback, such as the interactions between the atmosphere, oceans, and cryosphere, which are crucial for understanding long-term climate dynamics29. These advancements have enabled more precise simulations of temperature and precipitation patterns, vital for elucidating regional climate repercussions30. Nonetheless, substantial obstacles persist, particularly in the regional application of these models, where inherent uncertainties in model outputs can result in considerable variability in climate predictions31,32. These regional uncertainties are often attributed to structural differences among models and the challenges in accurately representing localized physical processes, leading to divergent climate projections for the same region33.

Multi-Model Ensemble (MME) has gained significant traction in climate research to address these uncertainties. Ensemble modeling, which involves combining outputs from multiple climate models, offers a robust methodology for reducing the biases inherent in individual models and capturing a wider range of possible climate outcomes34,35. MMEs have also proven to be particularly effective in evaluating a range of climate scenarios, including the SSPs, by providing probabilistic estimates that help to quantify the uncertainties associated with different future emission trajectories Tebaldi and Knutti36. By integrating the diverse outputs of CMIP6 models, ensemble techniques enhance the reliability and robustness of climate projections, particularly by reducing the impact of outlier results and identifying consistent trends across different models37,38,39. This integration is critical for improving the accuracy and reliability of climate predictions, thereby supporting more effective adaptation and mitigation strategies in vulnerable regions. In the classification provided by Wang et al.40, MME is broadly categorized into two principal types: (1) the Simple Ensemble Mean (SEM), which involves the use of individual models combined through traditional statistical methods such as averaging and median techniques with equal weighting (Sillmann et al.41 Wang et al.40); and (2) the Weighted Ensemble Method (WEM), which employs more sophisticated weighting strategies like the independence weighted mean and multidimensional scaling to ensure spatiotemporal consistency42. Each of these methods offers distinct advantages and disadvantages. The SEM, recognized for its straightforwardness, is a widely used approach that generally yields superior performance compared to individual model members Lambert and Boer43. However, this approach has certain limitations. A key concern is that many models often share similar parameterizations and components, leading to potential interdependencies among different climate simulations44. If this interdependence is not properly addressed, it can result in a misleading consensus among models, diminished accuracy, and inaccurate uncertainty estimation45. Conversely, WEM provides the benefit of mitigating systematic biases in the outputs of individual ensemble members, thereby enhancing the ensemble’s overall predictive accuracy46.

In recent years, machine learning-based approaches have been developed to enhance and complement traditional ensemble methods, such as the SEM and WEM in climate modeling47,48,49,50. Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a vital tool in improving the performance of climate model ensembles by effectively handling the complexities and uncertainties inherent in climate projections51. Considering these developments, numerous studies have explored integrating ML algorithms into climate model ensembles, demonstrating significant advancements in prediction accuracy and uncertainty reduction. For instance, Bilbao-Barrenetxea et al.29 demonstrated that MME techniques, when combined with ML algorithms, can enhance the accuracy of precipitation projections and improve hydrological modeling in complex terrains like the Pyrenees. Similarly, Yılmaz et al.52 utilized CMIP6 ensembles and ML to project significant temperature increases and precipitation decreases in Türkiye’s Altınkaya Dam Basin by 2100, highlighting the critical role of ML in refining these projections. Shao et al.53 further explored enhancing climate projections using CMIP6 ensembles through Time Variability Correction and Ensemble Dependence Transformation (EDT), significantly improving model and ensemble statistics for more accurate predictions. In another study, Wang et al.54 combined CMIP6 ensemble models with ML algorithms, such as Random Forest and Gradient Boosting, to project future precipitation changes in the Hanjiang River Basin, outperforming individual methods. The effectiveness of ML-based ensemble predictions was also demonstrated in the Western Ghats of India, where methods like XGBoost and Random Forest (RF) showed superior performance in simulating interseasonal variability and predicting future climate changes32. In Australia, Grose et al.28 focused on developing a CMIP6-based multi-model downscaling ensemble for climate change services, indicating the potential for ML integration to enhance regional climate projections.

Furthermore, Zhang et al.55 applied ML to CMIP6 ensembles to quantify future climate change under different socio-economic pathways, showing that global warming thresholds could be reached by 2048 under the SSP5-8.5 scenario. Singh et al.56 used ML models, including Random Forest, to predict increased streamflow in the Sutlej River Basin under various emission scenarios, further demonstrating the utility of ML in refining climate projections. Finally, in Iran, Asadollah et al.50 employed a Gradient Boosting Regression Tree (GBRT) ensemble model with CMIP6 data to downscale and project climate variables, showing significant improvements in replicating the region’s climate.

Previous research has mainly focused on evaluating individual ML methods with a uniform structure, highlighting their unique strengths. However, considering the diverse range of factors that impact climatic elements and the various statistical behaviors they exhibit, a single structured ML model may not be sufficient to fully capture the complex relationships between these elements and their predictors across different climatic regions57. In recent years, ensemble learning techniques, which amalgamate multiple ML models, have increasingly demonstrated superior efficacy58. To build on this progress, three prominent ensemble methods, Bagging, Boosting, and Stacking have been widely adopted to address the limitations of individual ML models59. Among these methods, stacking is particularly favored for its capacity to integrate predictions from several base models via a meta-learner, enhancing overall model performance60,61,62.

Building on these ensemble learning advancements, recent studies highlight the substantial benefits of advanced ML-based frameworks for climate projections in arid and hyper-arid contexts. For instance, Aldosary et al.63 integrated multiple ML algorithms such as Random Forest, LightGBM, and XGBoost to predict specific humidity in Dammam, Saudi Arabia, achieving near-perfect accuracy and enabling effective early-warning insights for heat stress hazards. Similarly, Baig et al.64 examined monthly rainfall prediction in the hyper-arid United Arab Emirates, revealing that XGBoost, Long Short-Term Memory, and stacked ensembles can substantially outperform conventional models when additional meteorological factors (e.g., wind speed) are incorporated.

Meanwhile, Najafi and Kuchak65 developed a monthly-to-seasonal precipitation forecasting system for Iran using downscaled global model outputs, reporting notable performance gains across diverse climatic zones. Expanding on these regional applications, Al-Saeedi et al.66 improved precipitation estimation in Jordan by integrating machine learning and geostatistical techniques, enhancing accuracy for drought assessment and water resource management. Similarly, Asadollah et al.50 applied ML-based downscaling in Iran, demonstrating how GBRT enhances CMIP6-based temperature and precipitation projections. Their findings indicate significant warming (+8 °C in highlands) and major precipitation shifts, emphasizing the need for localized ML downscaling in arid regions. Beyond these region-specific applications, ensemble learning methods have been widely adopted in broader climate modeling contexts, demonstrating their ability to enhance predictive accuracy across diverse environments. For instance, Tuysuzoglu et al.67 further reinforced the efficacy of ensemble approaches with their ensemble-based K-stars model for rainfall classification in Australia, underscoring how probability-based aggregating (pagging) significantly enhances predictive reliability. Similarly, Jaiswal et al.68 developed a stacking ensemble model that combined RF, XGBoost, and Support Vector Machine (SVM) to predict rainfall in India, achieving a notable accuracy of 81.2%. Similarly, Shetty et al.32 also demonstrated the effectiveness of stacking in improving the reliability of climate predictions. Additionally, Li et al.69 employed a stacking ensemble technique to integrate SVM, RF, Elastic Net Regression, and XGBoost for mid-term streamflow forecasting. Collectively, these studies underscore that ensemble learning especially stacking can effectively mitigate modeling uncertainties, capture a full range of climate extremes, and offer valuable guidance for adaptation strategies in data-scarce regions.

Despite the potential of ML stacking techniques, research that has applied these methods to enhance the accuracy and robustness of climate model predictions has remained limited. Recognizing that the goal of stacking is to leverage the strengths of base algorithms to build a more reliable framework than individual models70, this research aimed on developing a stacking ensemble model for predicting precipitation and maximum and minimum temperatures using multiple regressors of ML. The proposed method was structured in two levels: base models and a meta-model. At the first level, five ML models, including RF, XGBoost, LightGBM (LGBM), SVM, and CatBoost, were employed as base learners to model the climate elements of the Middle East. In the second level, the outputs from the base models were used to construct a meta-model by comparing three different models, including Artificial Neural Networks (ANN), Multiple Linear Regression (MLR), and Lasso (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) across two scenarios. After determining the most effective regressor for the meta-model, the Stacking-EML model was proposed under three scenarios (SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP5-8.5). The novelty of this study lies in developing a more reliable stacked model for improving the prediction of precipitation and temperature extremes in the Middle East.

Results

Performances of the individual ML models

The performance of five ML models in predicting maximum temperature, minimum temperature, and precipitation was evaluated using RMSE, R², MAE, NSE, and MBE metrics (Table 1). The results indicate that the differences between models are statistically significant (p < 0.05), highlighting that certain models provide superior predictive accuracy. According to the results, the LGBM and RF models consistently outperform the others. LGBM demonstrates the best overall performance, achieving the lowest RMSE and the highest R² values and favorable MAE, NSE, and near-zero MBE across all variables. RF followed closely, particularly excelling in temperature predictions.

In contrast, SVM, XGBoost, and CatBoost displayed comparatively lower accuracy, with CatBoost yielding the least favorable outcomes. Due to their superior performance, LGBM and RF are selected as the top models for integration into the meta-model, designed to enhance predictive capabilities by leveraging their strengths. The other models, including SVM, XGBoost, and CatBoost, showed lower accuracy, with CatBoost performing the worst overall. The decision to select LGBM and RF for meta-modeling is based on their proven ability to minimize errors and effectively capture the variability in climate data, making them suitable for developing robust climate projections for the study area. Consistent with our findings71, reported that the RF model demonstrates strong potential in precipitation prediction. Our experience here was also similar to the conclusions achieved by ref. 72, who emphasize that RF outperformed traditional ensemble methods, suggesting that ML techniques like RF and LGBM can significantly enhance the accuracy of climate predictions compared to conventional models. The LGBM model is also noted for its efficiency and accuracy in handling large datasets, which is essential for climate modeling73.

Performances of the Stacking Ensemble Models

The selection of the meta-model plays a crucial role in determining the final fit when stacking models. In this study, two scenarios were considered for the meta-modeling process. As outlined in Table 1, the RF and LGBM models were chosen as the base ML algorithms for the stacking approach. Three regressors, including ANN, MLR, and LASSO, were used to develop the final meta-model under two scenarios. The results indicate that ANN is the most effective regressor for both scenarios, particularly when additional geographic and topographic variables are included, as in SC2 (Table 2). This performance justifies the selection of ANN for constructing the final meta-model, while MLR and LASSO could serve as supplementary models, given their competitive performance. A review of previous studies reveals that, so far, geographical variables have not been utilized to enhance the accuracy of meta-models. However, current findings show that incorporating these variables significantly improves the performance of all models, underscoring the importance of using diverse data sources for robust climate modeling in the study area. Therefore, it is recommended that future research consider including geographical variables to advance the accuracy and reliability of meta-model construction.

To further assess the performance of the models and the influence of geographic variables on prediction accuracy, a Taylor diagram analysis was conducted for three climatic elements: maximum temperature, minimum temperature, and precipitation (Fig. 1). The analysis demonstrated that ML-based stacking models, particularly the stacking model incorporating an ANN in the SC2, outperformed other models, including traditional CMIP6 models such as AWI-CM-1-1-MR, MIROC6, and MRI-ESM2-0. These stacking models exhibited high correlation coefficients (above 0.95 for all variables) and standard deviations closely aligned with the observed data (ERA5 reanalysis dataset), indicating a superior ability to capture complex climatic patterns. Specifically, the stacking model with ANN in SC2 achieved the best performance among all models, with correlation coefficients of 0.99 for maximum temperature, 0.98 for minimum temperature, and 0.82 for precipitation. In contrast, the CMIP6 models, particularly MIROC6, displayed higher standard deviations (15 for maximum temperature, 10 for minimum temperature, and 1.25 for precipitation) and lower correlation coefficients, highlighting their limitations in reproducing climate variability.

Model skill is assessed for a maximum temperature, b minimum temperature, and c precipitation based on correlation coefficient, standard deviation, and centered root mean square error. The diagrams contrast traditional CMIP6 models (AWI-CM-1-1-MR, MIROC6, MRI-ESM2-0) with stacking ensemble models using ANN, MLR, and LASSO meta-learners under two scenarios (SC1 and SC2), with ERA5 reanalysis data serving as the observational benchmark.

Historical simulation assessment and bias analysis of climate variables

Figure 2a–i illustrates the spatial distribution of annual maximum temperature, minimum temperature, and precipitation for both observed and simulated data and the local R2 maps that evaluate model accuracy across the Middle East. According to Fig. 2a, southern regions, such as the Arabian Peninsula and North Africa, experience higher temperatures, a phenomenon attributable to their proximity to desert areas and the influence of hot, dry winds74. These areas are depicted in darker red shades on the map. In contrast, northern regions like Turkey and parts of Iran, characterized by higher elevations or proximity to the Mediterranean and Caspian Seas, exhibit lower temperatures. This variation is primarily due to differences in latitude, elevation, and environmental influences, such as the proximity to water bodies and local climatic conditions, especially the effects of deserts and prevailing wind directions in the region75. The climate model employed in this study has successfully reproduced these observed patterns, showing a high correlation between simulated and observed temperatures (Fig. 2b). Figure 2d illustrates the spatial distribution of minimum temperatures across the region. Lower temperatures are noted in the northern areas, such as Turkey and the mountainous regions of Iran, while higher temperatures prevail in the southern areas, including the Arabian Peninsula and North Africa. This spatial distribution reflects the influence of geographical and climatic factors like elevation, latitude, and proximity to deserts. The simulated model closely reproduces the general pattern of observed minimum temperatures, capturing the key features of the region’s minimum climate (Fig. 2e). The observed precipitation map (Fig. 2g) provides a clear depiction of rainfall distribution in the Middle East, highlighting higher precipitation levels in the northern and mountainous areas, particularly in northern Turkey, western Iran, and the mountainous regions of Lebanon and Syria. These areas experience elevated rainfall due to specific topographical conditions and the influence of moist air currents. Conversely, the southern and central parts of the Arabian Peninsula and parts of North Africa display the lowest precipitation levels, marked by orange and red shades on the map. The simulated precipitation map (Fig. 2h) aligns closely with the observed distribution, with the discrepancies largely minor and within the acceptable uncertainties of climate models.

The local R2 maps comprehensively evaluate the model’s accuracy in simulating the climatic variables across the Middle East. For maximum temperature, the R2 values range from 0.62 to 0.98 (Fig. 2c). The highest R2 values (close to 0.98) are found in the northern parts of the Middle East, including Turkey, western Iran, and parts of northern Iraq. This indicates that the model has a strong performance in capturing the maximum temperature patterns in these areas. In contrast, lower R2 values (around 0.62) are mainly observed in the central regions of the Arabian Peninsula, parts of Egypt, and central Iran. These spatial differences may result from complex local geographical features, such as deserts, variations in elevation, and diverse climatic conditions that pose challenges to accurate model simulations.

Similarly, the R2 map for minimum temperature displays a spatial distribution akin to that of maximum temperature, with values ranging from 0.62 to 0.99 (Fig. 2f). However, more regions with lower R2 values are observed, suggesting that the model encounters greater challenges in simulating minimum temperatures. The model performs better in predicting minimum temperatures in northern areas of the Middle East, including Turkey, northern Iran, and northern Iraq. In contrast, regions in the south, particularly the central parts of the Arabian Peninsula, sections of Egypt, and Yemen, exhibit lower R2 values. This discrepancy may be due to the complex interactions of geographical and climatic factors in these areas, such as daily and seasonal temperature fluctuations, desert influences, and regional atmospheric dynamics. The R2 map for precipitation reveals a broader range of values, from 0.23 to 0.98, highlighting the intrinsic complexities of precipitation modeling in the Middle East (Fig. 2i). Higher R2 values (close to 0.98) are primarily observed in the northern parts of the Middle East, including Turkey and northwestern Iran. Notably, these regions correspond with areas that experience higher precipitation, indicating that the model effectively captures precipitation patterns where rainfall is more abundant. On the other hand, lower R2 values are evident in the central and southern parts of the Arabian Peninsula, sections of Egypt, and other drier regions. This is likely due to the significant variability in precipitation and the influence of localized geographical and atmospheric conditions, which complicate accurate model simulations.

Spatial analysis of climate hotspots and cold spots in base year (2015)

The following analysis focuses on identifying significant hotspots and cold spots for maximum temperature, minimum temperature, and precipitation in the base year (2015) across the Middle East (Fig. 3). These hotspot maps utilize the Getis-Ord Gi* statistic in ArcGIS Pro V3.3.0 to identify areas with clusters of high or low values, highlighting significant spatial patterns of climate variability. By understanding the spatial distribution of these hotspots, we can better assess baseline climate risks and identify regions likely to experience the most significant impacts of climate change in future scenarios. The spatial distribution of maximum temperatures (Tmax) exhibits clear regional disparities (Fig. 3a). Hotspots characterized by higher maximum temperatures are most prominent in southern Iran, Saudi Arabia, the east of Egypt, and most of Oman. These areas display confidence levels between 90% and 99%, signifying a high degree of statistical confidence that these regions experienced significantly elevated Tmax values in 2015. In contrast, northern Turkey and northwestern Iran present cold spots with confidence levels of 95% and 99%, suggesting significantly lower maximum temperatures in these regions compared to the surrounding areas. These findings underscore the region’s thermal heterogeneity, with extreme heat and cooler zones coexisting within relatively close geographic proximity. The minimum temperature (Tmin) map (Fig. 3b) reflects a pattern broadly consistent with the Tmax results.

Maps show the spatial clustering of a maximum temperature (Tmax), b minimum temperature (Tmin), and c precipitation based on Getis-Ord Gi* statistics. Hotspots represent statistically significant clusters of high values, and cold spots represent significant clusters of low values at 90%, 95%, and 99% confidence levels. Areas not meeting statistical significance are labeled as Not Significant. These maps highlight spatial extremes and heterogeneity in baseline climate conditions.

Hotspots are observed in southwestern Saudi Arabia and along the southern coastline of Iran, where regions exhibit confidence levels from 90% to 99%, indicating areas of significantly higher minimum temperatures. This suggests that these areas experienced relatively higher minimum temperatures in 2015. Conversely, northern Turkey again emerges as a cold spot, showing 95% and 99% confidence levels for lower Tmin values. The consistency of cold spot identification in both Tmax and Tmin data suggests that northern Turkey may have been a region of notable thermal anomaly during this period. The spatial distribution of precipitation in 2015 presents a clear divide between the northern and southern parts of the Middle East (Fig. 3c). Northern Turkey, parts of northern Iraq, and areas along the Zagros Mountains in western Iran appear as prominent hotspots, with confidence levels of 95%. These regions received significantly higher precipitation levels than their surroundings, marking them as key zones of concentrated rainfall. The concentration of hotspots in these northern regions indicates that these areas experienced an unusually wet year in 2015, with precipitation levels significantly above the regional average.

On the other hand, southern Egypt, much of Saudi Arabia, and southwestern Yemen emerge as notable cold spots, reflecting areas of very low precipitation. These regions, particularly in southwestern Saudi Arabia, display confidence levels between 95% and 99%, highlighting a significant reduction in rainfall compared to other parts of the Middle East. The spatial clustering of cold spots in these southern areas emphasizes the persistently dry conditions that characterized these regions in 2015, with extremely low precipitation exacerbating the arid climate. The central regions, including much of Iraq, Syria, and central Iran, are classified as “Not Significant,” indicating that precipitation levels did not deviate significantly from the regional norm in 2015. However, the sharp contrast between the wet conditions in the northern hotspots and the dry, cold spots in the south underscores the regional precipitation pattern imbalance.

Projected climate variability and future trends using Stacking-EML

Under various climate scenarios, two analytical methods were employed to assess the projected changes in maximum temperature, minimum temperature, and precipitation in the Middle East from 2015 to 2099. First, we utilized monthly pixel-based data averaged across the entire region to provide a comprehensive overview of temporal patterns in these climatic variables. This approach facilitated the illustration of overall trends over time. Figure 4 presents the variation patterns of maximum temperature, minimum temperature, and precipitation under the SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5 scenarios. Analysis indicates a significant upward trend in maximum temperatures across all scenarios, particularly during summer. Under the SSP1-2.6 scenario, representing a relatively optimistic pathway, summer maximum temperatures gradually rise to ~35–40 °C, while winter temperatures remain relatively cool between 15 and 20 °C, suggesting a stable seasonal temperature pattern. In the SSP2-4.5 scenario, the increase is more pronounced, with summer temperatures frequently exceeding 40 °C and winter temperatures rising to about 20–25 °C. This scenario exhibits greater warming during spring and autumn, indicating more noticeable temperature fluctuations. The SSP5-8.5 scenario, representing high greenhouse gas emissions, projects extreme temperature increases, with summer maximum temperatures surpassing 45°C and winter temperatures exceeding 25 °C. This scenario indicates a substantial loss of seasonal temperature balance, with intense and persistent heat throughout the year. Projections for minimum temperatures indicate a pronounced upward trend, particularly under the more pessimistic climate scenarios. Under SSP1-2.6, minimum temperatures during summer months gradually increase to around 20 °C, while winter months maintain their relative coolness.

In contrast, the SSP2-4.5 scenario shows minimum temperatures exceeding 25 °C during summer, with winter minimum temperatures rising to 10–15 °C. The SSP5-8.5 scenario projects minimum summer temperatures above 30 °C and significant warming during winter to 15–20 °C. Precipitation projections suggest substantial variations and reductions, particularly during the summer months. Under SSP1-2.6, the precipitation pattern remains relatively stable, with marked reductions during summer indicative of seasonal droughts, while winter and spring months experience moderate rainfall. The SSP2-4.5 scenario continues to exhibit dry summer periods but with an increased frequency of heavy rainfall events in certain years and months, implying heightened variability and extreme precipitation events. Winter months in this scenario experience less rainfall compared to SSP1-2.6. The SSP5-8.5 scenario projects the most severe changes, with intensified summer droughts and a near absence of rainfall from June to September. Furthermore, sporadic occurrences of severe and irregular precipitation events during spring and winter reflect a significant reduction in annual precipitation and heightened climatic variability.

Projected spatial changes in climate parameters using Stacking-EML

Analyzing maximum temperature, minimum temperature, and precipitation at a general level lacks the spatial resolution to capture detailed regional changes in the Middle East. To address this, the Hotspot Analysis Comparison tool in ArcGIS Pro V3.3.0 with Fuzzy weights as a similar weighting method was employed to identify areas with significant changes, hot spots, and cold spots across different climate scenarios. This approach examines spatial variations and highlights regions sensitive to climate change. The analysis projects how these climatic elements will evolve under three emissions scenarios, SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5, over the periods 2015–2045, 2045–2075, and 2075-2099, offering insights into regional vulnerabilities.

Figure 5 presents the projected hotspots of maximum temperature changes in the Middle East across the SSP scenarios for the specified timeframes. Under the low-emission SSP1-2.6 scenario, the figure reveals limited but noticeable warming, particularly in the southern regions (Fig. 5a). Red areas shift to “Not significant to Hot,” mainly in central Saudi Arabia, parts of Yemen, and eastern Egypt. In Turkey and northern Iran, cooler regions maintain their “cold to cold” status. Between 2045 and 2075, the warming continues with less intensity; severe warming is controlled, and northern areas retain their cool status, though slight warming is observable (Fig. 5b). By 2099, significant temperature increases are prevented; while red areas slightly expand in Saudi Arabia and southern Iran, severe heat impact remains limited, and northern regions maintain cooler climates (Fig. 5c). In the moderate-emission SSP2-4.5 scenario, more significant warming occurs. Hot areas expand in central Saudi Arabia, the Red Sea coasts, and southern Iran, highlighting notable increases in maximum temperatures (Fig. 5d). By 2075, these areas will intensify and extend into southern Iraq, Oman, and western Yemen, indicating a shift toward extreme heat conditions (Fig. 5e). In the north, cooler areas remain stable, but initial signs of warming emerge, with some regions shifting to “cold to Not significant.” By 2099, a distinct north-south division emerges, with the southern regions engulfed in red zones, signaling persistent extreme heat, while the northern areas show a more widespread warming trend (Fig. 5f).

a, d, g 2015–2045, b, e, h 2045–2075, and c, f, i 2075–2099. The maps display hotspot and cold spot transitions based on the Getis-Ord Gi* statistic using Fuzzy weights. Color coding highlights statistically significant shifts in maximum temperature: deep red (Hot to Hot), pale red (Not Sig to Hot), and light red (Hot to Not Sig) indicate warming trends, while blue shades represent cooling (Cold to Cold, Cold to Not Sig, Not Sig to Cold).

Under SSP5-8.5, the most severe warming is projected. By 2045, vast sections of the southern Middle East, including southern Saudi Arabia, the Gulf countries, and parts of Iran, will be engulfed in red zones, indicating substantial increases in maximum temperatures (Fig. 5g). Between 2045 and 2075, the southern half of the Middle East remains dominated by these red areas, with prolonged and intense heat affecting Saudi Arabia, Oman, Yemen, and Egypt. In the northern regions, blue areas gradually diminish, transitioning toward neutral conditions (Fig. 5h). As the century draws to a close, severe warming peaks; red zones spread across the southern regions, leaving few areas in the north untouched. This scenario highlights the grave consequences of high emissions, potentially resulting in uninhabitable conditions (Fig. 5i).

For minimum temperatures (Fig. 6), the SSP1-2.6 scenario indicates moderate changes between 2015 and 2045. Blue areas (“cold to cold”) are widespread in northern regions, particularly in Turkey and northern Iran, signifying stable cooler temperatures (Fig. 6a). This stability reflects the success of emission reduction efforts in preserving cooler climates in these areas. Meanwhile, southern regions like Yemen, southern Iran, and Saudi Arabia fall within red zones (“Hot to Hot”), pointing to persistently high minimum temperatures. From 2045 to 2075, the red areas in the south expand slightly (Fig. 6b), though emission control efforts effectively limit severe warming. Northern regions remain largely unchanged, except for a slight decrease in blue areas in Iran, suggesting a mild warming trend. By 2099, the overall patterns show little change (Fig. 6c), with the north maintaining its status while the south continues to experience higher temperatures. These mild changes highlight the positive impact of strong climate actions in mitigating severe shifts in minimum temperatures. Under the SSP2-4.5 scenario, more noticeable changes in minimum temperatures occur. In the period from 2015 to 2045, southern regions, particularly Saudi Arabia, southern Iraq, and western Iran, transitioned to red areas (“Not significant to Hot”), indicating an increase in minimum temperatures (Fig. 6d). Northern regions remain cool with blue areas, though this stability appears increasingly threatened. By 2075, red zones in the south expand further, with significant warming observed in Saudi Arabia and southern Iraq (Fig. 6e). This trend suggests growing pressure on water resources, agriculture, and the environment. Although the north maintains cool temperatures, some blue areas gradually shift to neutral zones. By 2099, red areas dominate the southern Middle East (Fig. 6f), indicating severe warming. While northern regions mostly retain cool temperatures, signs of warming emerge, creating a clear North-South divide. The SSP5-8.5 scenario presents the most drastic changes in minimum temperatures. Between 2015 and 2045, red areas became prominent across the Arabian Peninsula and northern Yemen (Fig. 6g), where regions previously experiencing moderate temperatures now face significant warming. While northern regions initially remain within blue zones, some areas shift to “Not significant to cold.” By 2075, warming intensifies, with red areas spreading across most of the southern Middle East (Fig. 6h). Northern regions lose their blue areas, indicating a gradual warming trend. By 2099, severe warming is evident as red zones engulf much of Saudi Arabia, Oman, Yemen, and Iran (Fig. 6i). The northern regions lose most of their blue areas, transitioning to warmer categories, underscoring the grave consequences of continued high emissions. The SSP5-8.5 scenario presents the most drastic changes in minimum temperatures. From 2015 to 2045, red areas became prominent across the Arabian Peninsula and northern Yemen (Fig. 6g), where regions previously experiencing moderate temperatures now face significant warming. Although northern regions initially remain within blue zones, some areas shift to “Not significant to cold.” As we move into 2075, warming intensifies, with red areas spreading across most of the southern Middle East (Fig. 6h). In the north, blue areas begin to disappear, indicating a gradual warming trend. By the end of the century, severe warming is evident as red zones engulf much of Saudi Arabia, Oman, Yemen, and Iran (Fig. 6i). Most northern regions lose their blue areas, transitioning to warmer categories, highlighting the grave consequences of continued high emissions.

a, d, g 2015–2045, b, e, h 2045–2075, and c, f, i 2075–2099. This hotspot analysis is based on the Getis-Ord Gi* statistic using fuzzy spatial weights. Red shades indicate significant warming trends, with dark red representing consistent hot spots (Hot to Hot) and pale red showing newly emerging hot areas (Not Sig to Hot). Blue tones reflect areas of relative cooling (Cold to Cold, Not Sig to Cold), while gray zones indicate no significant change.

The analysis of projected precipitation changes under the SSP1-2.6 scenario reveals varying patterns between the northern and southern regions of the Middle East. From 2015 to 2045, northern areas, including Turkey and Iran, experienced a relative increase in precipitation (“Not significant to Hot”), as shown in Fig. 7a, while southern regions like Saudi Arabia faced decreased rainfall. From 2045 to 2075, precipitation patterns in the north remain stable. However, some areas in Iran shift towards unstable conditions (“Hot to Not significant”), as depicted in Fig. 7b. Regions with low precipitation extend to higher latitudes, affecting central Middle Eastern areas. By 2099, the SSP1-2.6 scenario prevents more severe changes; northern regions maintain stability, while southern areas continue to suffer from aridity (Fig. 7c). Under the SSP2-4.5 scenario, more significant changes occur. Between 2015 and 2045, northern regions continue to receive increased rainfall (Fig. 7d), whereas southern regions, especially Saudi Arabia and Yemen, encounter significant decreases. In 2075, central and western Iran transformed into “Hot to Hot” areas (Fig. 7e), indicating increased precipitation. In contrast, southern regions move towards severe aridity (“cold to cold”). By the end of the century, red areas dominate the southern Middle East (Fig. 7f), signifying severe aridity, while northern regions show signs of instability. The SSP5-8.5 scenario predicts the most severe precipitation changes. During the period from 2015 to 2045, southern Saudi Arabia, Yemen, and Oman shifted from “cold to Not significant” (Fig. 7g), although vast areas remain “cold to cold.” Western Iran experiences decreased precipitation, changing from “Hot to Not significant.” Between 2045 and 2075, precipitation increased in southern and western Iran (Fig. 7h), but Saudi Arabia, Oman, and Egypt changed to “cold”, signaling intensified aridity. Severe drought conditions dominate towards the end of the century (Fig. 7i), with “cold to cold” areas prevalent in southern regions, while northern areas exhibit widespread instability, even in previously stable rainfall zones.

a, d, g 2015–2045, b, e, h 2045–2075, and c, f, i 2075–2099. This analysis utilizes the Getis-Ord Gi* statistic with fuzzy spatial weighting to identify significant changes in precipitation patterns across the region. Red areas indicate zones of statistically significant increases in precipitation (e.g., “Hot to Hot”), while blue shades show areas of drying (e.g., “Cold to Cold”). The gray category represents areas with no significant change.

Discussion

In the Middle East, the climate crisis has become a primary concern for the region’s countries76,77. Food shortages, exacerbated by high birth and consumption rates and migration from unbearably hot areas to cooler regions, threaten the agricultural sector, which still employs 40% of the Middle Eastern population78. These factors illustrate the significant challenges the climate crisis poses for the region. This development not only endangers regional stability but also threatens global security. This study was designed to develop a stacking model to improve climate projections’ accuracy for key climatic elements in the Middle East. One of the key findings is the superior performance of the “Stacking-EML” framework compared to traditional methods, particularly in the second scenario where geographical factors, including longitude, latitude, elevation, slope, and aspect, were incorporated into the model estimations. These results underscore that ML approaches, especially stacking models based on ANN, can significantly enhance the accuracy of climate predictions. By combining the capabilities of multiple models and leveraging their complementary features, these approaches improve predictive performance for complex climatic variables. This advancement provides a more reliable foundation for policymakers to formulate strategies addressing the climate crisis in the region.

Our study’s findings reveal that the expected rise in temperatures, especially under the SSP5-8.5 scenario, could exacerbate these issues, leading to even more profound environmental and societal consequences. The substantial rise in temperatures, especially under the SSP5-8.5 scenario, indicates a severe warming trend, which could lead to profound environmental and societal consequences79,80. For instance, it is projected that summer daytime temperatures will exceed 45 °C, which creates hazardous heat conditions, puts immense strain on energy systems required for cooling, and exacerbates water scarcity81. Additionally, the findings indicate a projected increase in minimum temperatures in the coming years. Higher winter temperatures will disrupt the seasonal balance, shortening the cooler periods vital for agricultural cycles, natural ecosystems, and public health25. The loss of this seasonal equilibrium is expected to trigger significant changes in natural cycles and agricultural patterns across the region29. These findings underscore the urgent need for climate adaptation strategies, water resource management, and greenhouse gas emission reduction to mitigate the growing impacts of climate change. Rising minimum temperatures also present serious challenges for climate adaptation in the region. Increasing minimum temperatures, particularly under the SSP5-8.5 scenario, exacerbate climate anomalies by disrupting seasonal cycles and intensifying extreme climate events, such as more frequent warm nights and shorter cooler periods28. This trend leads to heightened energy consumption additional stress on water and energy infrastructures, and poses significant risks to public health through prolonged heatwaves and warm nights, severely impacting human health and ecosystems82,83,84. Long-term climate policies, particularly in response to the SSP5-8.5 scenario, must become a regional priority to address these emerging challenges. Additionally, as highlighted by ref. 85, integrating the prediction of heatwave-related mortality into climate models can improve the forecasting of extreme temperature impacts on public health. This method further supports the need for adaptive management in vulnerable regions like the Middle East, where rising temperatures could substantially increase mortality rates due to heat stress.

The analysis of precipitation patterns under different climate scenarios further emphasizes the critical risks facing the Middle East. A significant reduction in rainfall, especially under the SSP5-8.5 scenario, suggests an intensification of seasonal droughts and greater variability in precipitation, leading to severe challenges such as water resource depletion, reduced agricultural productivity, and increased environmental hazards79. Long-term projections, such as those by ref. 86, support these concerns, showing that the region’s arid and semi-arid areas will significantly reduce precipitation and soil moisture, further straining water resources. Moreover, the increased variability and frequency of extreme precipitation events under this scenario highlight the need for comprehensive water resource management and climate adaptation planning87. Even under the SSP2-4.5 scenario, notable changes in precipitation patterns raise concerns about heightened risks of flash floods and other climate-induced challenges. For example, Kassaye et al.88 concluded that under the SSP2-4.5 scenario, studies project a general increase in streamflow magnitude, with yearly flow expected to rise by 4.8% during the mid-term (2041–2070). These trends make it clear that urgent climate action and targeted water management strategies are essential to mitigate the long-term impacts of climate change across various scenarios, particularly the pessimistic SSP5-8.582.

Given the significant impacts of climate change in the Middle East, identifying the most vulnerable areas is crucial for targeted adaptation and resource management. Initially, a trend analysis using the Mann-Kendall test was conducted to identify these critical areas. However, after calculating the trends, it became clear that under the SSP5-8.5 scenario, the entire Middle East exhibits consistent upward trends in minimum and maximum temperatures and a downward trend in precipitation, making it impossible to distinguish specific vulnerable areas based solely on trend analysis. Therefore, one of the most effective techniques in this context, Hotspot comparison analysis, was applied89. This method identifies “hot” and “cold” spots and tracks their shifts over time. In this study, these areas were found to be statistically significant at the 99% confidence level, with at least two intersecting climatic elements, helping policymakers prioritize regions where the impacts of climate change are likely to be most severe. The spatial distribution of sensitive areas in the Middle East under various climate scenarios (SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5) projected for 2099 offers critical insights into the future climate risks faced by the region. Analysis of these projections reveals five categories of risk areas: (1) regions with high maximum and minimum temperatures alongside low precipitation, (2) regions exposed to high maximum and minimum temperatures, (3) areas vulnerable due to high maximum temperatures combined with reduced precipitation, (4) regions at risk from high minimum temperatures coupled with low precipitation, and (5) regions projected to experience increased precipitation. Under the SSP1-2.6 scenario (Fig. 8a), southern Saudi Arabia, UAE, Yemen, and Oman regions are high-risk, particularly concerning the highest maximum and minimum temperatures. This suggests that, even under a low-emission scenario, these areas will face elevated temperatures, potentially exacerbating heat stress, agricultural challenges, and water scarcity90. These findings align with projections by Mora et al.81 and Lima et al.91, which indicate an increase in both the frequency and intensity of heatwaves in the Middle East, even under low-emission scenarios. The most critical areas are concentrated in southeastern Saudi Arabia, northern Oman, and eastern Yemen, where all three climatic variables reach their most extreme levels.

Maps (a–c) illustrate the intersection of significant climatic stressors including maximum temperature, minimum temperature, and precipitation using Getis-Ord Gi* analysis. Colored zones represent areas where at least two extreme climatic variables coincide, identifying the regions at greatest risk from combined heat and moisture stress. Red and orange boundaries indicate compounding temperature extremes, blue.

Additionally, coastal vulnerability is observed in eastern Egypt, attributable to high maximum and minimum temperatures and a lack of precipitation. Conversely, northern Iran, parts of the Zagros Mountains, and eastern Turkey are projected to experience increased rainfall. In the SSP2-4.5 scenario (Fig. 8b), the expansion of high-risk areas becomes more pronounced, particularly in southern and central Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the UAE, Oman, western Yemen, Iran, and Egypt. The findings indicate that in this scenario, an intensification of extreme heat conditions and a further reduction in precipitation are expected, especially in southern regions. These findings corroborate research by Hamed et al.92, who reported that CMIP6 models project a decrease in precipitation, and by Malik et al.93, who noted a significant increase in temperature in arid and semi-arid regions under moderate-emission scenarios. Critical areas concerning maximum and minimum temperatures, previously limited to southern Iran, have expanded considerably in this case.

The most vulnerable regions are in western Yemen, where extreme temperatures coincide with diminished rainfall. As projected in the SSP1-2.6 scenario, most parts of the Middle East are expected to experience a decrease in precipitation. According to the research by Terink et al.94, most countries in the Middle East are expected to experience a reduction in annual precipitation. In particular, a 15–20% decrease in rainfall is projected during 2040–2050. Regions such as southern Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Syria, and eastern Iran are expected to face the most significant reductions in precipitation.

On the other hand, increased precipitation is expected for northern Iran, areas along the Caspian Sea, the Zagros Mountains, and eastern Turkey. This finding is consistent with previous research indicating a shift toward heavier rainfall events in these areas95,96,97. According to these studies, the western and northern parts of Iran are expected to encounter significant increases in precipitation. Abbaspour, Faramarzi, Ghasemi and Yang97 suggest that northern and western Iran will experience greater rainfall and a higher likelihood of large and severe floods in these regions under various climate change scenarios.

Similarly95, found that the number of days with heavy (R10mm) and heavy rainfall (R20mm) will significantly increase, particularly along the southern Caspian Sea coast and the Zagros Mountains. In alignment with these findings, our results also corroborate Sarış98, who highlighted the increased susceptibility of the Black Sea region to heavy precipitation. Furthermore, Majdi et al.99 reported a decrease in precipitation, ranging between 5 and 133 mm on average, across most parts of the Middle East and Mediterranean regions, based on an analysis of 23 GCMs. This variability across regions underscores climate change’s complex and multifaceted impacts on rainfall patterns in the broader region. Similarly, the SSP2-4.5 scenario also anticipates increased precipitation in some parts of Iran and Turkey. The potential for future increases in precipitation in certain areas of the Middle East may be explained by a theory put forward by Francis and Vavrus100, which links climate change to extreme weather patterns in mid-latitude regions. This theory suggests that weakened zonal winds, coupled with increased wave amplitude, contribute to the slower movement of Rossby waves, subsequently increasing the likelihood of extreme weather events101.

The SSP5-8.5 scenario (Fig. 8c) presents the most severe and widespread climate impacts. The southern Middle East, including Saudi Arabia, Oman, Yemen, Iraq, and Iran, is predominantly characterized by extreme heat, with substantial consequences for agriculture, water resources, and human habitability. In this scenario, regions experiencing critical maximum and minimum temperatures and precipitation reduction, which were previously confined to lower latitudes, now extend to Kuwait and southeastern Iraq. These findings align with previous research by Black et al.102, which projects a decrease in precipitation and an increase in temperatures in the southern Middle East under greenhouse gas emission scenarios. The study also predicts a shift toward polar storm tracks and the weakening of Mediterranean storm systems, potentially leading to reduced winter rainfall in the region. According to research conducted by Almazroui et al.103, it is projected that by the end of the 21st century, under the RCP8.5 scenario, temperatures in the central and southern regions of the Arabian Peninsula will increase by up to 6.4 °C. In contrast, the northern regions will experience a temperature rise of 5.2 °C. These projections further corroborate our findings, suggesting a significant rise in temperature in areas such as Kuwait and southeastern Iraq and highlighting the broader trend of increasing temperatures across the Arabian Peninsula. Similarly, Varela et al.104 concluded that the eastern Arabian Peninsula and North Africa will be among the most affected areas, with extreme temperatures occurring over 80% of days.

In summaty, this study presents a novel ensemble ML framework, Stacking-EML, aimed at enhancing climate forecasting for the Middle East by utilizing CMIP6 datasets. With its diverse climate and geography, the Middle East faces major ecological challenges due to climate change. These challenges include rising temperatures, changes in precipitation trends, and more frequent severe weather events. Accurately predicting and assessing these climate impacts is crucial for effective adaptation and mitigation strategies. Our methodology seeks to address this need by combining various ML algorithms to improve the accuracy and robustness of climate variable forecasts against varying input data and different climatic conditions. The Stacking-EML model was developed through a comprehensive, multi-phase framework. Initially, five distinct ML algorithms, including Random Forest, XGBoost, LGBM, SVM, and CatBoost, were trained using monthly datasets covering precipitation, maximum temperature, and minimum temperature from selected CMIP6 GCMs for 2015–2100. Among these, LGBM and RF showed superior performance, particularly in capturing the variability in climate data across the Middle East. These models were then combined into a meta-model using a stacking ensemble strategy, with an ANN acting as the most effective regressor in the final meta-model. The Stacking-EML framework significantly improved compared to individual models and traditional CMIP6 outputs. Evaluation criteria, including RMSE and R², showed enhanced predictive accuracy for precipitation and temperature extremes. Incorporating geographical and topographical factors, such as longitude, latitude, elevation, slope, and aspect, further optimized the model’s performance, highlighting the importance of integrating diverse data sources in climate modeling. Spatial analyses using Hotspot Analysis revealed critical insights into expected climate changes under different SSP scenarios. The model forecasts a considerable increase in maximum and minimum temperatures across the Middle East, particularly under the high-emission SSP5-8.5 scenario. This scenario predicts extreme temperature increases, with summer maximum temperatures exceeding 45 °C and a notable disruption of seasonal temperature balance. Precipitation trends are expected to show substantial variability and reductions, especially during summer, leading to intensified drought conditions and greater climate variability.Identifying vulnerable areas through hotspot and cold spot assessments highlights regions likely to experience the most severe impacts of climate change. Southern areas, including Saudi Arabia, Oman, Yemen, and parts of Iran and Egypt, are projected to face extreme heat scenarios and reduced precipitation, potentially exacerbating water scarcity, agricultural productivity, and public health issues. In contrast, northern regions such as Turkey and northern Iran may see increased precipitation, presenting distinct challenges such as flooding and ecosystem disruptions.

Methods

Study area

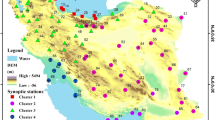

The Middle East (Fig. 9) is a geographically and climatically diverse region encompassing sixteen countries, including those of the Arabian Peninsula (Oman, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Yemen, and Qatar), as well as Jordan, Syria, Iran, Palestine, Iraq, Turkey, Egypt, and Lebanon105. It spans an area of over 69 million km2 and hosts a wide range of climatic conditions, from the extremely arid deserts of the Arabian Peninsula and parts of Egypt to the semi-arid or more temperate highlands of Turkey and the mountainous regions of Iran106. Average annual precipitation typically falls below 250 mm in vast portions of the region; however, areas adjacent to the Mediterranean and Caspian Seas and mountainous corridors such as the Zagros and Taurus ranges can receive substantially higher rainfall74,75,76,107. Temperature extremes are equally striking, with summer highs frequently surpassing 50 °C in the Arabian Peninsula and winter lows dropping below freezing in upland areas93. Such spatial heterogeneity and pronounced aridity pose major challenges for climate modeling, particularly given limited in-situ data coverage, complex topographical influences, and rapid demographic expansion in water-scarce zones77,106. This study’s focus on the Middle East is motivated by its acute vulnerability to climate-related stressors, including heatwaves, rainfall deficits, and water resource depletion, all of which are exacerbated by climate change76. The region’s significant temperature gradient from intensely hot and hyper-arid conditions along the southern Arabian coasts and deserts to cooler, more humid pockets in northern highlands creates an ideal testbed for evaluating ensemble machine learning approaches that aim to capture the complexity and extremes of regional climatic behaviors. By systematically incorporating both arid lowlands and relatively more temperate uplands, the present framework provides an opportunity to assess the robustness of our Stacking-EML methodology across a broad range of climate profiles.

Methodological framework

The comprehensive framework employed in this study is illustrated in Fig. 10. The methodology is structured into five phases: Phase I involves compiling the Model Dataset, Phase II, Base ML Model Development, entails training five machine learning algorithms, including RF, Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost), Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM), Support Vector Machine (SVM), and CatBoost. These models predict the input data in Phase III, Base Model Predictions. Phase IV, Stacking and Meta-Modeling, focuses on creating the Meta Model. Finally, Phase V emphasizes predicting input data using the Stacking-EML approach.

Phase I: Dataset compilation

Phase I involves compiling the Model Dataset, which includes monthly data on precipitation, maximum temperature, and minimum temperature from CMIP6, simulated by selected Global Climate Models (GCMs) for 2015–2100. Additionally, ERA5 reanalysis data (1995–2014) are employed for bias-correcting the historical portion of the GCM outputs and for validating model performance, while the digital elevation model (DEM) provides critical topographical features (elevation, slope, and aspect) that support both the co-Kriging downscaling step and the subsequent refinement of predictions in the meta-model. The datasets employed in this study are outlined as follows:

CMIP6

The monthly maximum temperature, minimum temperature, and precipitation data of CMIP6 simulated by some selected GCMs over 2015–2100 are obtained from the Earth System Grid data distribution portal (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/). CMIP6 uses future scenarios to examine how climate change might occur under different greenhouse gas emission scenarios108. SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5 climate scenarios represent future global climate change projections until 2100. SSP1-2.6 represents an optimistic scenario where global CO2 emissions drop to zero by 2050, aligning with the Paris Agreement’s goal to limit global warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels, with a radiative forcing of 2.6 W/m² and temperatures stabilizing at 1.4 °C by 210012. In contrast, SSP2-4.5 is a moderate scenario with intermediate climate mitigation and adaptation efforts, leading to a radiative forcing of 4.5 W/m² by 2100. It aligns somewhat with the Paris Agreement, predicting a warming of ~2.7 °C by the end of the century109. On the other hand, SSP5-8.5 outlines a high-emission scenario with significant climate change mitigation challenges and minimal adaptation issues, leading to a radiative forcing of 8.5 W/m² by 2100. Without additional climate policies, it predicts a 4 °C increase in global temperatures by the end of the century, updating the CMIP5 RCP8.5 scenario with socioeconomic factors110,111.

This study utilizes monthly outputs from three CMIP6 Global Climate Models (GCMs), namely AWI-CM-1-1-MR, MIROC6, and MRI-ESM2-0 for the period 2015–2100 under three Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) scenarios (SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, SSP5-8.5) (Table 3). These GCMs were selected based on four principal criteria: (i) spatial resolution (nominal 100–250 km), which balances computational efficiency with adequate representation of regional climate processes112, (ii) scenario availability for all three SSP pathways, essential in assessing a broad range of future emission trajectories, (iii) proven skill in precipitation simulation over arid and semi-arid domains, as demonstrated in prior regional studies52, and (iv) temporal coverage and consistency with a baseline observational period (1995–2014) to facilitate bias correction against ERA5 reanalysis data25.

The raw GCM outputs frequently exhibit systematic biases, particularly in topographically complex or data-sparse regions113. To address these discrepancies and reconcile the varying spatial resolutions (GCM nominal resolutions of 1.1°–1.4° vs. ERA5 at 0.1° and the high-resolution DEM), a co-Kriging downscaling approach was employed, and the GCM outputs were first spatially resampled to a consistent 0.5° × 0.5° grid. Specifically, a co-Kriging method was used for this spatial interpolation, leveraging topographical features (elevation, slope, and aspect) from the DEM as secondary variables. This approach improves upon ordinary Kriging by incorporating additional geographic information, thereby refining estimates in complex terrains and preserving local variance more effectively114. Moreover, Co-Kriging offers a significant advantage in regions with complex topography or sparse observational data by leveraging secondary topographical variables. This method refines spatial patterns in climate simulations by incorporating real-world geographical dependencies, reducing systematic interpolation errors that may arise in simpler spatial resampling methods. Co-Kriging is particularly advantageous for downscaling climate variables in mountainous or data-sparse areas, as it leverages correlations with secondary variables to achieve higher spatial accuracy115. Following the co-Kriging downscaling, a two-step bias correction (Linear Scaling and Quantile Mapping) was applied for bias correction116. The bias correction process reduces discrepancies between GCM outputs and observed data, facilitating alignment between modeled and observed distributions. While this process cannot eliminate structural uncertainties arising from the incomplete simulation of certain physical processes in climate models, its effectiveness in improving accuracy and consistency with real-world data has been demonstrated in various studies113. The combination of Co-Kriging and bias correction in this study provides a comprehensive and efficient approach to enhancing the accuracy of climate data. This method corrects systematic biases in GCM outputs and offers greater flexibility in downscaling data to more accurately represent regional climate variations. Previous research has shown that such an integrated approach significantly improves prediction accuracy and enhances the agreement between simulated and observed values117. Therefore, while uncertainties are an inherent part of climate modeling, adopting this combined approach effectively minimizes errors and improves the regional representation of climate data118. Prior validation studies confirm that AWI-CM-1-1-MR, MIROC6, and MRI-ESM2-0 exhibit robust skill in simulating temperature trends, precipitation variability, and key climatological extremes over the Middle East119,120,121. Comparative evaluations with broader CMIP6 ensembles suggest that these models effectively capture seasonal precipitation cycles, including winter rainfall peaks in northern Middle Eastern regions, and reproduce long-term warming trends consistent with multi-model assessments92. Furthermore, their skill in replicating historical drought frequencies and heatwave intensities has been established in prior regional assessments, reinforcing their credibility for future projections122. Despite these advantages, it is important to note that any downscaling procedure may introduce additional uncertainties, particularly in areas where observational data are sparse or topographic gradients are highly variable.

Reanalysis data

ERA5, the fifth generation of reanalysis products developed by the ECMWF, is employed to reanalyze global atmospheric changes using both models and observational data. Data from multiple sources, including satellites, meteorological stations, and aircraft, are combined with advanced physical models to produce high-precision spatiotemporal distributions of various meteorological variables on a global scale123. Significant improvements over its predecessor, ERA-Interim, include enhanced spatial resolution (0.25° compared to 0.75° for ERA-Interim), the incorporation of a substantially larger volume of observations for data assimilation, improved representation of radiative forcing (including sulphate aerosols from volcanic eruptions), a better global balance between precipitation and evaporation, and more accurate sea surface temperature and sea ice coverage124,125. For this study, ERA5 precipitation and temperature data from 1 January 1995 to 31 December 2014, with a spatial resolution of 0.1° × 0.1° and monthly temporal resolution, were obtained from the Copernicus Climate Data Store (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/).

Digital elevation model

In this study, the Digital Elevation Model (DEM) was employed to capture the topographical features of the study area, including elevation, slope, and aspect. The high-resolution SRTM15 + DEM, with a spatial resolution of 15 arc seconds (~500 m at the equator), was used to provide detailed bathymetry and topography data. This model integrates over 33.6 million measurements from sources such as the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency and Scripps Institution of Oceanography. Onshore topography data are primarily derived from SRTM-CGIAR V4.1, ArcticDEM above 60°N, and the Reference Elevation Model of Antarctica below 62°S126. These DEM-based variables were instrumental in the co-Kriging downscaling step and were introduced later in Phase IV to refine the meta-model’s predictive accuracy.

Phase II: Base model development

Phase II focuses on developing base models using various ML algorithms. This phase aims to create models that can accurately predict climate variables, such as maximum temperature, minimum temperature, and precipitation, based on historical data from different scenarios (SSP1-2.6, SSP2-4.5, and SSP5-8.5) derived from the CMIP6 climate models (AWI-CM-1-1-MR, MIROC6, MRI-ESM2-0). To ensure the reliability of training data, ERA5 reanalysis data was used as a reference for bias correction of the CMIP6 model outputs before being employed in ML model training. The reanalysis dataset provides high-resolution climate variables, reducing systematic biases in raw GCM simulations and ensuring that training data better represents observed climate conditions. ERA5-adjusted climate variables served as input features for training all base ML models, thereby improving model generalization. In this phase, various ML algorithms are employed to develop base models, each designed to effectively capture the complex relationships in climate data. These models were selected based on their proven ability to process nonlinear climate dynamics, handle high-dimensional datasets, and provide reliable predictions in climate modeling applications127. We adopted a structured feature selection approach to enhance the models’ predictive performance. RF and XGBoost were used to assess the importance of various predictors, given their proven ability to rank features effectively in complex environmental datasets128.

Based on these analyses, temperature, precipitation, elevation, slope, and aspect emerged as the most influential variables, ensuring spatial consistency and optimizing model outcomes. By contrast, initially considered a potential predictor, wind speed had a negligible impact on overall performance and was thus excluded from the final feature set. Focusing on these high-contribution predictors allowed a clearer understanding of how climate variables interact with geographic factors, ultimately improving forecast accuracy. Subsequently, we partitioned the dataset using an 80-20 split, with 80% of the data allocated for training and 20% reserved for validation. In addition, a stratified 5-fold cross-validation procedure was implemented to reduce predictive variance further and bolster model generalization. This method strikes a pragmatic balance between computational efficiency and dependable performance estimation in datasets of moderate size, where larger k-values often yield diminishing returns while substantially increasing computational overhead. Model hyperparameters were optimized using GridSearchCV, which systematically evaluates different parameter configurations to identify the best fit for each base algorithm. This tuning process was conducted independently for every model, ensuring that each algorithm performed optimally. Once trained, the base models produced predictive outputs covering key variables like temperature and precipitation that were consolidated into a structured dataset, ready for integration into the subsequent meta-modeling phase.

Base ML models

ML offers promising algorithms for analyzing complex environmental phenomena and climate studies129,130. Over recent decades, it has been extensively utilized for predicting and forecasting various climate parameters131,132,133,134,135. ML models’ superior performance and ability to handle large datasets make ML a popular and practical alternative to traditional statistical methods for predicting climatic and complex variables133,136. Considering the critical role of ML in enhancing the accuracy of climatic variable predictions, this research applied a range of advanced ML algorithms, including RF, XGBoost, LightGBM, SVM, and CatBoost. These models were chosen for their strong predictive capabilities and suitability in managing complex environmental datasets. Table 4 provides a comparative analysis of these ML models, outlining their strengths and weaknesses. Each algorithm was trained on a portion of the dataset to maximize predictive accuracy.

Random forest

Random forest is a sophisticated ML algorithm that combines tree-based classifiers and is known for its high accuracy in classification, prediction, and regression tasks137. This algorithm constructs an ensemble by averaging outputs from multiple trees, and each is created using bootstrap samples from the training data. At each node of the trees, a random selection of predictor variables is assessed, introducing diversity and reducing correlation among the trees. RF’s notable resistance to overfitting and its robustness in handling noisy data and irrelevant features make it particularly effective. This has resulted in its outperforming traditional ML models, especially in climate studies and environmental research, where it has found widespread application138,139,140,141.

XGBoost

XGBoost, an optimized version of Gradient Boosting (GB), is widely regarded for its use in optimal classification trees142. It effectively addresses overfitting by reducing model complexity, enhancing classification accuracy, and decreasing computation time through high-speed analysis143,144. Unlike traditional GB, which relies solely on decision trees, XGBoost incorporates classification trees and linear regression, making it highly effective in processing sparse data through parallel computing145,146.

LGBM

LGBM is a decision tree-based gradient boosting framework that utilizes boosting techniques147. Unlike XGBoost, LGBM employs a histogram-based algorithm, which accelerates training, reduces memory usage, and utilizes a leaf-wise growth strategy with depth constraints148,149. The histogram algorithm discretizes continuous floating-point values into bins, constructing a histogram without needing additional storage for pre-sorted data. This approach allows the model to reduce memory consumption significantly, ~1/8 of the original, without compromising accuracy.

SVM

Support Vector Machines (SVMs) extensively utilize supervised learning algorithms that employ linear statistical functions for regression and classification tasks150. High levels of accuracy are achieved by SVMs even when dealing with limited data, owing to their maximal-margin classification approach. Input vectors are mapped into an infinite-dimensional feature space, where nonlinear transformations are used to construct an optimal hyperplane that maximizes class separation151. The performance of SVMs is significantly influenced by the choice of kernel functions, which include polynomial, sigmoid, radial basis function (RBF), and linear kernels. The RBF kernel is commonly employed among these, particularly in flood vulnerability assessments152.

CatBoost

CatBoost is a gradient-boosting decision tree model known for its exceptional performance as an individual and a meta-model in ensemble methods153. It efficiently handles categorical features, reducing information loss and mitigating overfitting through a random permutation method for selecting tree structures154,155. This capability makes CatBoost highly suitable for real-world applications, such as predicting soil water content using multi-sensor data156.

Phase III: base model predictions

Phase III focuses on generating initial predictions by applying the trained base models from Phase II to the test data for forecasting climate variables. A stratified fivefold cross-validation approach was employed to ensure robust performance, facilitating model generalization and minimizing predictive variance. Hyperparameter optimization was conducted using GridSearchCV, systematically identifying the best configurations for each model. Details on data partitioning and validation methodology are provided in Section 3.2. Once trained, the base models produced predictive outputs for key climate variables, which were subsequently integrated into the meta-modeling phase. This technique reduces the prediction variance and helps prevent overfitting by validating the model across multiple data partitions157. After generating predictions, evaluation metrics such as the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), the coefficient of determination (R2), Nash-Sutcliffe Efficiency (NSE), and bias metrics like Mean Bias Error (MBE) are calculated to assess model performance. These results identify the best-performing models, which will be refined and combined in the next phase to create a more robust ensemble model. This approach leverages the strengths of each base model, enhancing overall predictive accuracy and robustness.

Phase IV: Stacking and meta-modeling

Phase IV enhances predictive accuracy by constructing a meta-model that integrates the predictions from the two best-performing base models identified in Phase III. This approach utilizes stacking, a well-known ensemble learning technique originally proposed by Wolpert158, which leverages the complementary strengths of multiple models to improve overall prediction accuracy. Stacking combines the outputs of several base models as input features for training a meta-model, which produces the final predictions for the target variable. The meta-model is trained to effectively integrate the base models’ predictions, enhancing overall performance and generalization capability159. In this phase, additional geographical and topographical features, including elevation, slope, aspect, longitude, and latitude, were introduced as supplementary predictors in the meta-model to improve spatial precision and ensure that predictions account for topographic influences on climate variables while preventing multicollinearity issues. The meta-learning model at this stage evaluates whether topographical factors significantly improve predictive performance, allowing for a more adaptive and dynamic modeling approach. The stacking framework consists of multiple base models performing classification or regression tasks on the training dataset, with a meta-learner refining these predictions to surpass the accuracy of any single model.