Abstract

The Arctic Oscillation (AO) is a dominant atmospheric mode in the Northern Hemisphere, influencing weather and climate. Its variations are driven by numerous factors, including Arctic sea ice, particularly autumn Barents-Kara Sea ice concentration (SIC), which can significantly impact the AO through planetary wave dynamics. However, the interdecadal stability of this relationship remains unclear. This study detected the weakened November Barents-Kara SIC-January AO connection after the mid-1990s. Observational and model analysis showed that from 1979 to 1994, their relationship was driven by the North Atlantic tripole (NAT) sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies, which influenced storm track activities over North Atlantic and Eurasia, thus inducing a wave train resembling the Scandinavian pattern. After the mid-1990s, weakened interannual variability of the NAT SST anomalies disrupted this mechanism. These findings highlight the critical role of mid-latitude ocean-atmosphere interactions in Arctic climate variability and emphasize the need for further research on long-term AO-SIC linkages.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Arctic Oscillation (AO) is one of the most dominant atmospheric modes in the Northern Hemisphere1,2. Its variations can exert notable impacts on weather, climate, and daily life3,4,5,6. Hence, it is important to study how the AO changes. The spatiotemporal variation of the AO can be influenced by various factors, such as the stratospheric polar vortex7,8. In addition, the negative phase of the AO can be triggered by changes of Eurasian snow cover in the preceding autumn9. Changes of Eurasian snow cover can induce the upward propagation of planetary waves and weaken the stratospheric polar vortex, triggering the negative phase of the AO in winter10. Previous studies have revealed that ocean-atmosphere interactions can also influence the AO. For instance, the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) can shift the atmospheric baroclinic zone and enhance the air temperature gradient over North Atlantic, resulting in a more pronounced AO in the subsequent winter by affecting transient eddy activities11,12. Besides, North Atlantic sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies play an important role in shaping the Arctic center of the AO13.

Arctic sea ice is also a crucial factor that affects the AO. Changes of the autumn Arctic sea ice concentration (SIC) exerts notable impacts on the winter AO14,15,16,17,18. Specifically, reduced SIC in autumn can alter surface albedo, which can further weaken the stratospheric polar vortex through upward propagation of planetary waves19. Weakened stratospheric polar vortex propagates downward to the lower troposphere in the subsequent winter, triggering a negative phase of the AO20,21,22. In recent decades, Arctic sea ice has been rapidly melting, with the most severe melting occurring over the Barents-Kara Sea23. Hence, reduced SIC over the Barents-Kara Sea can exert notable impacts on Eurasian climate. For example, reduced Barents-Kara SIC in November can shift the location of the Siberian storm track24. Changes in the Siberian storm track can affect cyclone activities in the downstream polar region and induce a negative phase of the AO in the subsequent winter25.

In recent decades, owing to rapid global warming and the melting of Arctic sea ice, the AO-Eurasian climate connection has become unstable15,26,27,28,29. The relationship between the AO and the East Asian winter monsoon strengthened after the 1980s, which may be attributed to the melting of the Barents-Kara SIC30,31. Additionally, Song et al.32 detected a weakened relationship between the November Barents-Kara SIC and the winter North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) after the mid-1990s. Because of the similarity between the NAO and the AO, the Arctic sea ice-AO connection may also undergo similar changes3,33, but it still remains unclear. Understanding changes of the Arctic sea ice-AO connection can help improve the prediction skill of the AO and the AO-related extreme weather events. Consequently, in this study, we aimed to investigate the interdecadal changes in the Arctic sea ice-AO relationship and explore the possible mechanisms for these changes.

Results

Changes in the relationship between autumn Arctic SIC and winter AO

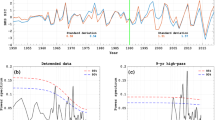

The positive phase of winter AO was preceded by a notable increase in autumn SIC over the Barents-Kara Sea (75°N-83°N, 15°E-90°E, Fig. 1a), which was consistent with previous studies21,34,35. Here, the normalized area-averaged SIC over the Barents-Kara Sea was defined as the Barents-Kara SIC index. The correlation coefficient between the autumn Barents-Kara SIC and the winter AO during the study period (1979–2015) was 0.41 (p < 0.05). However, according to the 21-year sliding correlation analysis, their relationship weakened from over 0.6 (p < 0.05) during 1979-1994 to approximately 0.3 (p > 0.1) after that (Fig. 1e). To investigate the weakened relationship between the autumn Barents-Kara SIC and winter AO after the mid-1990s, detailed analysis was performed. The relationship between January AO and Barents-Kara SIC in autumn was the most significant during the entire research period, with a correlation coefficient of 0.4 (p < 0.05). Meanwhile, the correlation coefficient between December (February) AO and the autumn Barents-Kara SIC was only 0.24 (0.28), which was insignificant and could be further verified by conducting regression and sliding correlation analysis (Figures S1, S2). A more detailed analysis revealed that January AO was notably correlated with the Barents-Kara SIC in the preceding November and October (Fig. 1b, c). The correlation coefficient between January AO and the November Barents-Kara SIC was 0.32 (p < 0.1) over the entire research period. However, their correlation coefficient decreased from nearly 0.6 (p < 0.05) during 1979-1994 to only 0.14 (p > 0.1) post-1994 (Fig. 1f). The correlation coefficient between January AO and the Barents-Kara SIC in October was 0.58 (p < 0.05) over the entire research period. Although their connection also weakened after the mid-1990s, they remained significantly correlated (0.37, p < 0.1) (Fig. 1g). The relationship between the January AO and September Barents-Kara SIC weakened after 1990. However, both the change in their relationship and their correlation coefficients were less significant than those between the November Barents-Kara SIC and January AO (Fig. 1d, h). In conclusion, the January AO-November Barents-Kara SIC relationship experienced the most robust change during the research period, reflecting the focus of this study.

a Regression of autumn Arctic SIC (%) onto the normalized winter AO index. Dotted areas denote the 90% confidence levels. Regressions of (b) November, (c) October, and (d) September Arctic SIC onto the normalized January AO index. Black boxes in (a–d) indicate the Barents-Kara Sea. The 21-year sliding correlation between the autumn Barents-Kara SIC index and the normalized winter AO index is shown in (e). Sliding correlation between the normalized January AO index and (f) November, (g) October, and (h) September Barents-Kara SIC index. Black solid (dashed) lines in (e−h) indicate the 95% (90%) confidence levels.

Changes in the Barents-Kara SIC-related circulation anomalies

To explore the possible mechanisms that could explain the weakened relationship between the November Barents-Kara SIC and January AO after the mid-1990s, the research period was divided into two subperiods: 1979-1994 (P1) and 1995-2015 (P2). It should be noted that the sign-reversed Barents-Kara SIC index was applied in the regression and correlation analysis afterwards. The reduced November Barents-Kara SIC during P1 was accompanied by a significant wave train extending from the mid-latitude North Atlantic to the polar region at 200 hPa (Fig. 2a). This wave train reflected the Scandinavian (SCA) pattern with a spatial correlation coefficient of 0.71 (p < 0.1, figure not shown). Such wave train propagated north-eastward and caused an anticyclonic anomaly over the Ural region (50°N-80°N, 10°E-70°E) (Fig. 2a). It should be noted that the SCA-like wave train exhibited an equivalent barotropic structure throughout the troposphere (Figure S3). Meanwhile, downward turbulent heat flux (the sum of sensible turbulent heat flux and latent turbulent heat flux) occurred over the southern Barents sea (Fig. 2c). The anomalous anticyclone over the Ural region could transport warm and moist air from subtropical North Atlantic to the Arctic region, which warmed the sea surface through downward turbulent heat flux and resulted in reduced Barents-Kara SIC as a consequence. Reduced Barents-Kara SIC induced a south-eastward propagating wave train and formed a cyclonic anomaly over East Asia (30°N-60°N, 70°E-120°E) (Fig. 2a). Additionally, upward turbulent heat flux occurred over the northern Barents-Kara sea (Fig. 2c). This indicated that reduced Barents-Kara SIC increased the amount of open water and the atmosphere above the northern Barents-Kara sea became warmer and moister because of the heat and mass transport from the open water. This process has been verified by previous studies36,37. Hence, notable water vapor flux (WVF) convergence occurred over the Barents-Kara sea (Fig. 2e). Then the water vapor was transported south-eastward due to the anticyclonic anomaly over the Ural region, causing WVF divergence south of the Ural region and convergence over East Asia. Anomalous WVF convergence (divergence) led to more (less) total column snow water (TCSW) (Fig. 2g). Hence, a snow cover zonal dipolar structure was formed over Eurasia, with snow cover increasing over East Asia and decreasing south of the Ural region (Fig. 2i). Reduced Barents-Kara SIC and Eurasian snow cover anomalies can exert impacts on the atmospheric circulation through troposphere-stratosphere coupling9,38,39,40,41. To better understand this process, the Eliassen-Palm (E-P) flux was calculated and regressed onto the sign-reversed Barents-Kara SIC index. Reduced Barents-Kara SIC in P1 was accompanied by upward propagation of planetary waves around 50°-60°N (Figure S4a). Interestingly, the most significant upward propagation occurred over the region where the Eurasian snow cover zonal dipolar structure occurred. This indicated the joint effort of the reduced Barents-Kara SIC and the Eurasian snow cover zonal dipolar structure on the troposphere-stratosphere coupling (Figure S4a). What’s more, we used time-height evolution diagram of polar cap height to further verify the upward propagation of planetary waves. Here, composite analysis was applied according to the Barents-Kara SIC index. During P1, positive geopotential height anomalies propagated upward to approximately 20 hPa in November when the Barents-Kara SIC was reduced, indicating that the stratospheric polar vortex was weakened (Fig. 3e). Previous study also showed that the eastern Siberian pole of the snow cover zonal dipolar structure mainly caused the weakened stratospheric polar vortex in December and January9, which highlighted the effect of regional snow cover changes on stratospheric circulation. Here, the eastern Siberian pole is formed through the joint effort of the reduced Barents-Kara SIC and the anticyclonic anomaly over the Ural region. This reflects the importance of reduced Barents-Kara SIC and the associated atmospheric circulation in the formation of the Eurasian snow cover zonal dipolar structure. During P2, However, the SCA-like wave train disappeared (Fig. 2b), characterizing as a north-eastward shift of the anticyclonic anomaly over the Ural region. Although the atmospheric circulation anomalies could still result in decreased Barents-Kara SIC through downward turbulent heat flux (Fig. 2d), the different atmospheric circulation conditions led to WVF convergence and increased TCSW over the Ural region (Fig. 2f, h). Hence, the Eurasian snow cover zonal dipolar structure disappeared in P2 (Fig. 2j), which eventually led to weakened troposphere-stratosphere coupling (Figure S4d, Fig. 3f).

Regressions of November (a) 200 hPa geopotential height (shaded, unit: 10−2 gpm) and WAF (vectors, unit: m2·s−2), (c) turbulent heat flux (thf, positive upwards, unit: 10−6 W·m−2), (e) WVF (vectors, unit: kg·m−1·s−1) and its divergence (shaded, unit: 10−6 kg·m−2·s−1), (g) TCSW (unit: kg·m−2) and (i) snow cover (unit: %) onto the sign-reversed November Barents-Kara SIC index during P1. b, d, f, h, j are as in (a, c, e, g, i), respectively, but for P2. Black boxes in (e–j) denote the key areas used to define the Eurasian snow cover zonal dipole structure index. Green contours indicate the 90% confidence levels.

Regressions of (a) December 200 hPa geopotential height (shaded, unit:10−2 gpm) and WAF (vectors, unit: m2·s−2) and (c) January 200 hPa geopotential height onto the sign-reversed November Barents-Kara SIC index during P1. e Shows the time-height evolution diagram of polar cap height. Shadings represent differences of geopotential height between low Barents-Kara SIC years and high Barents-Kara SIC years in P1. (b, d, f) are as in (a, c, e), respectively, but for P2. Green contours denote the 90% confidence levels.

In P1, the SCA-like wave train in November developed into a hemispheric zonal wave train in December with an equivalent barotropic structure (Fig. 3a, Figure S5), which further weakened the stratospheric polar vortex through upward propagating E-P flux (Figure S4b)42. In addition, weakened stratospheric polar vortex began to propagate downward in December as well, characterizing as downward propagating E-P flux over the Arctic region and notable downward propagation of positive geopotential height anomalies over the polar region in late December (Figure S4b, Fig. 3e). The downward propagation of planetary waves peaked in January. Not only did downward propagating E-P flux occur over mid-to-high latitude Eurasia (Figure S4c), but the positive geopotential height anomalies over the polar region propagated downward to the lower troposphere (Fig. 3e). Consequently, a negative phase of the AO was established (Fig. 3c). These results were consistent with previous studies, which demonstrated that the SCA pattern in boreal autumn can weaken the stratospheric polar vortex and result in the downward propagation of planetary waves one month later, triggering the negative phase of the AO9,38,43,44,45. During P2, however, with the disappearance of the SCA-like wave train, vertical propagation of planetary waves became less robust in December and January (Fig. 3f, Figures S4d, f). Such atmospheric conditions were unfavorable for the formation of the negative phase of the AO in January. Accordingly, the anomalous anticyclone over the polar region in P1 weakened and shifted to the Atlantic sector in P2, whereas the anomalous cyclone over the mid-latitude Pacific in P1 shifted northeastward toward the Bering Strait in P2 (Fig. 3d).

From the above, the reduced November Barents-Kara SIC during P1 was accompanied by an SCA-like wave train extending from the mid-latitude North Atlantic to the polar region. This equivalent barotropic wave train formed an anomalous anticyclone over the Ural region and facilitated reduced Barents-Kara SIC through downward turbulent heat flux. Then massive amount of open water occurred over the Barents-Kara sea because of the reduced Barents-Kara SIC. Consequently, the air above the Barents-Kara sea became warmer and moister through upward turbulent heat flux from the open water. Additionally, reduced Barents-Kara SIC triggered a south-eastward propagating wave train that formed a cyclonic anomaly over East Asia. The aforementioned atmospheric circulation anomalies led to anomalous WVF convergence over East Asia and divergence south of the Ural region. The WVF anomalies caused by the reduced Barents-Kara SIC and the anomalous anticyclone over the Ural region favored the formation of the Eurasian snow cover zonal dipolar structure, which, together with the reduced Barents-Kara SIC, induced upward propagation of planetary waves and weakened the stratospheric polar vortex in November and December. The weakened stratospheric polar vortex triggered downward propagation of planetary waves in late December and January, which formed the negative phase of the AO. Nevertheless, both the SCA-like wave train and the Eurasian snow cover zonal dipolar structure disappeared after the mid-1990s. Hence, upward propagation of planetary waves was insignificant and the atmospheric conditions were unfavourable for the formation of negative phase of AO in January. To further verify these findings, the Eurasian snow cover zonal dipolar structure index (SCE index) was defined as the normalized area-averaged November snow cover over (40°N-55°N, 70°E-120°E) minus that over (50°N-60°N, 25°E-55°E). The correlation coefficient between the sign-reversed Barents-Kara SIC and the SCE index in P1 was 0.62 (p < 0.01). However, their correlation coefficient became insignificant (0.31, p > 0.1) after the mid-1990s (Figure S6). In addition, although the November SCA and January AO remained significantly correlated after the mid-1990s, the November Barents-Kara SIC-November SCA and December SCA-January AO relationships weakened after the mid-1990s, which was consistent with the change in the relationship between the November Barents-Kara SIC and January AO (Figure S6). The relationship between the SCE index and January AO (November SCA) remained stable after the mid-1990s, with a correlation coefficient of -0.35 (0.46). These results indicated that the disappearance of the SCA-like wave train might be able to explain the weakened relationship between the November Barents-Kara SIC and January AO after the mid-1990s.

Modulation by the North Atlantic SST anomalies

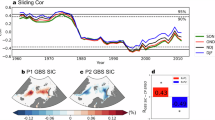

Because the SCA-like wave train during P1 originated in the North Atlantic (Fig. 2a), the disappearance of the SCA-like wave train after the mid-1990s may be related to the SST anomalies therein. In P1, the reduced November Barents-Kara SIC was accompanied by a robust North Atlantic tripole (NAT) SST anomaly (Fig. 4a). The spatial structure of this SST anomaly pattern was similar to the results of previous studies46,47,48. However, the NAT SST anomalies associated with reduced Barents-Kara SIC weakened after the mid-1990s (Fig. 4b). This indicated that the NAT SST anomalies may be able to modulate the November Barents-Kara SIC-January AO connection. To verify this hypothesis, an index was proposed to quantitatively depict the NAT SST anomalies. We projected the SST anomaly field shown in Fig. 4a to the November SST field in the entire research period and defined the normalized time series obtained from the spatial projection as the NAT index. The correlation coefficient between the NAT index and the sign_reversed Barents-Kara SIC index decreased from 0.67 (p < 0.01) in P1 to 0.32 (p > 0.1) in P2, which verified their weakened relationship after the mid-1990s (Figure S6). Detailed analysis were then conducted to investigate what caused the weakened relationship between the NAT SST anomalies and November Barents-Kara SIC after the mid-1990s. During P1, the SST anomaly associated with the NAT index exhibited a notable tripolar structure, similar to that regressed onto the November Barents-Kara SIC index (Fig. 4a, c). This induced a weakened meridional SST gradient over the subtropical North Atlantic and strengthened the meridional SST gradient east of Newfoundland (Fig. 4e). Changes in the meridional SST gradient can affect the low-level meridional air temperature gradient and thus the low-level atmospheric baroclinicity49,50. Hence, the meridional air temperature gradient at 850 hPa increased east of Newfoundland but decreased over subtropical North Atlantic (Fig. 4g), which strengthened (weakened) the storm track activities over western Europe (subtropical North Atlantic) (Fig. 5a). Transient eddy forcing, associated with changes in storm track activity, is one of the most important processes that mid-latitude SST anomalies exert on atmospheric circulation51. To better understand how the NAT SST anomalies influenced atmospheric circulation, the geopotential height tendency induced by synoptic-scale transient eddy forcing was calculated at 200 hPa using the quasi-geostrophic potential vorticity equation52:

where \(f\) denotes the Coriolis parameter, \(S\) represents the static stability parameter, \(g\) is the acceleration of gravity, \(\Theta\) is the potential temperature of the background field. \({{\rm{v}}}^{{\prime} }\), \({{\rm{\zeta }}}^{{\prime} }\), and \({\theta }^{{\prime} }\) represent the eddy velocity, vorticity, and potential temperature, respectively. During P1, changes in storm track activities associated with the NAT SST anomalies led to a positive geopotential tendency over the subtropical North Atlantic (Fig. 5c), where the storm track activities weakened (Fig. 5a). Meanwhile, a negative geopotential tendency occurred over Western Europe (Fig. 5c). Such conditions were favorable for the formation of SCA-like wave train, as mentioned previously (Fig. 2a). Consequently, a zonal wave train resembling the SCA pattern was established in P1, which propagated northeastward and caused an anticyclonic anomaly over the Ural region (Fig. 5e). A detailed analysis revealed that the positive geopotential tendency over the northwestern Atlantic and the negative geopotential height tendency over western Europe were mainly driven by eddy vorticity flux forcing (Figure S7a). In contrast, the positive geopotential height tendency over the Ural region was mainly attributed to eddy heat flux forcing (Figure S7c). In P2, although the SST anomalies associated with the NAT index was still characterized as a tripolar structure, all three SST centers were less robust than P1, indicating a weakened NAT SST anomalies (Fig. 4d). This caused the meridional SST gradient to weaken as well (Fig. 4f). These changes were accompanied by similar changes in the low-level meridional air temperature gradient but with a notably weakened negative low-level meridional air temperature gradient at approximately 40°N (Fig. 4h). Hence, the weakened (strengthened) storm track activities over subtropical North Atlantic and northeastern Europe (western Europe) during P1 became insignificant in P2 (Fig. 5b). Meanwhile, storm track activities notably strengthened south of Greenland owing to the positive low-level meridional air temperature gradient over the east coast of North America (Figs. 4h, 5b). Changes in storm track activities led to negative geopotential tendency over the Ural region and northwestern Atlantic through transient eddy forcing (Fig. 5d), which was nearly the opposite of that during P1. Therefore, the SCA-like wave train disappeared after the mid-1990s (Fig. 5e).

Regression of SST (unit: °C) onto the sign-reversed November Barents-Kara SIC index in (a) P1 and (b) P2. c–h Show regression of SST (c, d), meridional SST gradient (e, f, unit: °C/102 km) and meridional air temperature gradient at 850 hPa (g,h, unit: °C/102 km) onto the normalized NAT index. c, e, g Show the results for P1, whereas (d, f, h) show the results for P2. Green contours indicate the 90% confidence levels.

Regressions of (a) storm track activity (unit: gpm), (c) geopotential height tendency (unit: gpm∙day−1), and (e) geopotential height (shaded, unit:10-3 gpm) and WAF (vectors, unit:m2·s−2) at 200 hPa onto the normalized NAT index during P1. b, d, f are as in (a, c, e), respectively, but for P2. Regression of 200 hPa geopotential height, derived from the ensemble mean of 5 AMIP models, onto the NAT index calculated using the models’ SST input datasets during (g) P1 and (h) P2. Green contours denote the 90% confidence levels.

To conclude, the November NAT SST anomalies played a crucial role in modulating the relationship between the November Barents-Kara SIC and January AO by impacting the SCA-like wave train. However, these effects disappeared after the mid-1990s due to the weakening of the NAT SST anomalies. According to the sliding correlation analysis, the relationship between the November SCA index and NAT SST anomalies weakened after the mid-1990s Their correlation coefficient decreased from 0.49 (p < 0.1) during P1 to 0.09 (p > 0.1) during P2 (Figure S6). This indicated that the NAT SST anomalies affected the SCA-like wave train, which further exerted impacts on the Barents-Kara SIC and eventually the January AO through the aforementioned physical processes. To further support this conclusion, we calculated the 15-year moving standard deviation of the NAT index. As is shown in Figure S8, the interannual variability in the NAT SST anomalies weakened after the mid-1990s. Detailed analysis showed that the weakened variability of the NAT SST anomalies after the mid-1990s could be mainly attributed to the weakened variability of the warm SST anomaly center around 40°N (Fig. 4a, Figure S8), which might be related to the weakened Gulf Stream. As part of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), the Gulf Stream notably weakened after the end of the 20th century53,54. Recent researches revealed that the weakened Gulf Stream was mainly caused by rapid sea ice melting associated with human-induced global warming. Sea ice melting led to decreased sea surface salinity over subpolar Atlantic, thus weakening the AMOC55. Additionally, the geopotential height outputs of the chosen Atmospheric Model Intercomparison Project (AMIP) models were analyzed as well. Through regressing the geopotential height outputs of the models onto the NAT index derived from their SST input datasets, more than half of the chosen models could reproduce the zonal wave train shown in Fig. 5e and achieve a Taylor score of higher than 0.5 (Figures S9, S10). What’s more, we chose the best five models (EC-Earth3 (0.9), HadGEM-GC31- MM (0.58), MRI-ESM2-0 (0.66), CNRM-CM6-1-HR (0.88) and TaiESM1 (0.68)) according to their Taylor scores and calculated the best multimodel ensemble mean (BMME). Results show that BMME could better reproduce the SCA-like wave train than most of the models, with a Taylor score of 0.71 (Fig. 5g). Moreover, both the chosen AMIP models and the BMME simulated the disappearance of the SCA-like wave train during P2 (Fig. 5h). However, the simulation results of the models in P2 differed notably from those obtained from the reanalysis datasets (Fig. 5f, h). This indicated that changes in atmospheric circulation in P2 can be attributed to forcings other than the NAT SST anomalies. To investigate this phenomenon, we calculated the climatology of SST in P1 and P2 and their differences after removing the long-term linear trend. Results showed that the SST climatology notably changed after the mid-1990s (Figures S11a, b). Previous research concluded that changes of SST background state can adjust the atmospheric mean flow and modulate the ocean-atmosphere interactions56. Although the NAT SST anomalies showed similar spatial distribution in P1 and P2, the different SST background state could result in changes of the intensity of ocean-atmosphere interactions. Hence, the effect of NAT SST anomalies on the atmospheric circulation weakened after the mid-1990s because of the change of SST background state, characterizing as SST warming south of the Greenland and cooling over the Gulf Stream (Figure S11c). It should be noted that the change of SST background state could be explained by the phase shift of the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO) around the mid-1990s57. Phase change of the AMO could alter the atmospheric circulation, which might be capable of explaining the phenomenon mentioned above58.

Discussion

In this study, interdecadal changes in the relationship between the November Barents-Kara SIC and January AO after the mid-1990s were investigated. The November Barents-Kara SIC- January AO relationship weakened from significantly positive during 1979-1994 to insignificant after the mid-1990s. This change may be attributed to the modulation by the November NAT SST anomalies. In P1, the reduced November Barents-Kara SIC was accompanied by a notable NAT SST anomalies. However, the NAT SST anomalies notably weakened after the mid-1990s. In P1, the NAT SST anomalies weakened (strengthened) meridional SST and air temperature gradients over the subtropical North Atlantic (east of Newfoundland), which further generated variations in storm track activities over northeastern Europe and the mid-latitude North Atlantic. Changes of storm track activities induced a wave train closely resembling the SCA pattern through transient eddy forcing. The SCA-like wave train formed an anomalous anticyclone over the Ural region, causing a reduced Barents-Kara SIC through downward turbulent heat flux. Reduced Barents-Kara SIC not only triggered a south-eastward propagating wave train and formed a cyclonic anomaly over East Asia, but also exerted impacts on water vapor transport and induced a Eurasian snow cover zonal dipolar structure together with the anticyclonic anomaly over the Ural region. In December, the SCA-like wave train developed into a hemispheric zonal wave train with an anomalous anticyclone over the North Pacific. Meanwhile, the reduced Barents-Kara SIC and Eurasian snow cover zonal dipolar structure in November triggered the upward propagation of planetary waves and consequently weakened the stratospheric polar vortex. This led to downward propagation of planetary waves to the lower troposphere in the subsequent January, which triggered the negative phase of the AO. However, after the mid-1990s, the SCA-like wave train vanished because of the weakened interannual variability of the NAT SST anomalies, which could be attributed to the weakening of the Gulf Stream and changes of SST background state. Hence, the Eurasian snow cover zonal dipolar structure disappeared, which was unfavorable for troposphere-stratosphere coupling and caused a weakened negative AO phase in the subsequent January. The causal chain of the mechanism mentioned above are summarized in Fig. 6.

During 1979–1994, the NAT SST anomalies in November triggered an atmospheric zonal wave train that propagated north-eastward and caused an anticyclonic anomaly over the Ural region. The anticyclonic anomaly over the Ural region led to reduced Barents-Kara SIC through downward turbulent heat flux. Reduced Barents-Kara SIC triggered a wave train and formed a cyclonic anomaly over East Asia. In addition, it also affected water vapor transport through upward heat exchange from the open water and caused a snow cover zonal dipolar structure over Eurasia together with the anticyclonic anomaly over the Ural region. The joint effort of reduced Barents-Kara SIC and the Eurasian snow cover zonal dipolar structure enhanced troposphere-stratosphere coupling and weakened the stratospheric polar vortex in December and January. Consequently, planetary waves propagated downward in the subsequent January, triggering the negative phase of AO. During 1995–2015, the NAT SST anomalies associated with the reduced November Barents-Kara SIC weakened, resulting in the disappearance of the atmospheric zonal wave train and the snow cover zonal dipolar structure over Eurasia. These changes weakened the troposphere-stratosphere coupling and were unfavorable for the formation of the negative phase of the AO in January. Dark Blue, light blue, and red arrows indicate mechanisms occurring in November, December and January, respectively.

This study revealed the role of the NAT SST anomalies in modulating the relationship between November Barents-Kara SIC and January AO. Nevertheless, limitations still exist. For instance, the conclusion of this research was mainly drawn by conducting statistical analysis with a sample size of 37 years. It is still unclear whether the relationship between November Barents-Kara SIC and January AO will undergo another interdecadal variation. This should be verified in the future with long-term coupled model experiments, including models from Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6). In addition, the physical mechanism in this research includes multi-timescale interactions in the atmosphere. Although previous researches have highlighted the role of synoptic-scale transient eddies in modulating mid-to-high-latitude atmospheric circulation40,49,50, its effect is sensitive to changes of the atmospheric mean state. For instance, in this research, change of atmospheric mean state after the mid-1990s due to the phase shift of the AMO led to different transient eddy feedback processes. Consequently, future researches should pay more attention to the atmospheric mean state before studying the effect of transient eddies on adjusting atmospheric circulation.

Another point that should be included in this discussion section is the similarity that AO shares with the NAO. Previous researches demonstrated that NAO is closely related to mid-latitude storminess59, reversal of winter surface air temperature over Eurasia60 and air-sea coupling over Atlantic61. However, AO is a dominant mode throughout the entire Northern Hemisphere and can be related to polar-midlatitude interactions at larger spatiotemporal scales compared to NAO3,6. Hence, studying AO and its linkages with Arctic sea ice and mid-latitude atmospheric circulation can help better understand the hemispheric air-ice-ocean coupling between mid-latitude and the Arctic region. Finally, the Arctic sea ice has rapidly melted owing to global warming. Researchers have estimated that an ice-free Arctic is likely to occur before the mid-21st century62. Under these circumstances, it is unclear if the relationship between Arctic sea ice and climate change in the Northern Hemisphere will persist in the future and if mid-latitude ocean-atmosphere interactions can modulate their relationships. These uncertainties require further investigations.

Methods

Datasets and climate indices

Monthly SIC and SST data were obtained from the Hadley Center Sea Ice and SST datasets of the UK Met Office63, which are gridded with a spatial resolution of 1° × 1°. Daily and monthly atmospheric reanalysis datasets were derived from the fifth-generation atmospheric reanalysis dataset of the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts64, including geopotential height, sea level pressure, zonal and meridional wind, air temperature, specific humidity, TCSW, snow cover and surface sensible and latent heat flux. The AO and SCA indices were derived from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Data were obtained in Autumn (September-November) and Winter (December-February) from 1979 to 2015. All of the aforementioned data were interpolated to a spatial resolution of 1° × 1° before analysis.

Atmospheric Model Intercomparison Project model outputs

The Atmospheric Model Intercomparison Project (AMIP) is a baseline experiment in the Diagnostic, Evaluation, and Characterization of Klima (DECK) experiments, CMIP665. By simulating atmospheric conditions from 1979 to 2015, based on observational SST and SIC datasets, AMIP models were used to evaluate the atmospheric components of the climate system65,66. The AMIP models were driven by the Hadley optimum interpolation-merged observational SST and SIC datasets67. These datasets were included in the Input Datasets for Model Intercomparison Project (input4MIP) of the Program for Climate Model Diagnosis and Intercomparison68,69. Here, the geopotential height outputs of 10 AMIP models from their first ensemble members were utilized. The details of the chosen models are listed in Table 1. The input4MIP SST data were also utilized. The AMIP model outputs used in this study were interpolated to a 1° × 1° grid before the analysis.

Dynamic diagnosis methods

To understand the effects of atmospheric planetary waves, T-N wave activity flux (WAF) was calculated using the following equation70:

where \(p\) is usually scaled by 1000 hPa, \(\left|U\right|\) is the velocity of horizontal wind, \({\psi }^{{\prime} }\) is the perturbation of stream function, and \(\varphi\) denotes latitude. U and V represent the zonal and meridional components of basic flow, respectively. Additionally, following Lyu et al.37 (see their Eqs. (2) and (3)), the Eliassen-Palm flux was also calculated to verify the vertical propagation of planetary waves. The synoptic-scale variance in the 200 hPa geopotential height (ZZ200) was used to characterize the storm track activity71.

Statistical analysis

In order to qualitatively evaluate the chosen AMIP models’ performance, we calculated the Taylor score by using the following equation72:

where R is the spatial correlation between the model and reanalysis data, \({\sigma }_{f}\) denotes the ratio between the standard deviation of model result and that of reanalysis data. Here, \({R}_{0}\) equals to 1. S has a range between 0 and 1. Larger S indicates better model performance. Low-frequency signals longer than nine years in the chosen datasets were eliminated by applying a Fourier high-pass filter to emphasize the interannual variability. The two-tailed Student’s t test was applied to determine statistical significance, with the effective degree of freedom calculated due to high-pass filtering73.

Data availability

The monthly SIC and SST data from the Hadley Center Sea Ice and SST dataset of the UK Met Office (https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/hadobs/hadisst/). The daily and monthly atmospheric reanalysis datasets from the fifth-generation atmospheric reanalysis dataset of the European Center for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/datasets/). The AO and Scandinavian pattern (SCA index) (https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/). The AMIP model outputs and the input4MIP SST data (https://aims2.llnl.gov/).

Code availability

The python codes used for the analysis of this manuscript are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hurrell, J. W. Decadal trends in the North Atlantic Oscillation: Regional temperatures and precipitation. Science 269, 676–679 (1995).

Thompson, D. W. J. & Wallace, J. M. The Arctic Oscillation signature in the wintertime geopotential height and temperature fields. Geophys. Res. Lett. 25, 1297–1300 (1998).

He, S. P., Gao, Y. Q., Li, F., Wang, H. J. & He, Y. C. Impact of Arctic Oscillation on the East Asian climate: A review. Earth Sci. Rev. 164, 48–62 (2017).

Li, L., Li, C. Y. & Song, J. Arctic Oscillation anomaly in winter 2009/2010 and its impacts on weather and climate. Sci. China Earth Sci. 55, 567–579 (2012).

Liu, Y. S., Sun, C., Gong, Z. Q., Li, J. P. & Shi, Z. Multidecadal seesaw in cold wave frequency between central Eurasia and Greenland and its relation to the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation. Clim. Dyn. 58, 1403–1418 (2022).

Wang, L., Gong, H. N. & Lan, X. Q. Interdecadal variation of the Arctic Oscillation and its influence on climate. Trans. Atmos. Sci. 44, 50–60 (2020).

Bushra, N. & Rohli, R. V. Relationship between atmospheric teleconnections and the Northern Hemisphere’s circumpolar vortex. Earth Space Sci. 8, e2021EA001802 (2021).

Sun, J. & Tan, B. Mechanism of the wintertime Aleutian Low–Icelandic Low seesaw. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 4103–4108 (2013).

Gastineau, G., García-Serrano, J. & Frankignoul, C. The influence of autumnal Eurasian snow cover on climate and its link with Arctic sea ice cover. J. Clim. 30, 7599–7619 (2017).

Cohen, J., Furtado, J. C., Barlow, M. A., Alexeev, V. A. & Cherry, J. E. Arctic warming, increasing snow cover and widespread boreal winter cooling. Environ. Res. Lett. 7, 014007 (2012).

Peings, Y. & Magnusdottir, G. Forcing of the wintertime atmospheric circulation by the multidecadal fluctuations of the North Atlantic ocean. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 034018 (2014).

Gong, H. et al. Structural fluctuations of the Arctic Oscillation tied to the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 260 (2024).

Fang, Z., Sun, X., Yang, X.-Q. & Zhu, Z. Interdecadal variations in the spatial pattern of the Arctic Oscillation Arctic center in wintertime. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL111380 (2024).

Bader, J. et al. A review on Northern Hemisphere sea-ice, storminess and the North Atlantic Oscillation: Observations and projected changes. Atmos. Res. 101, 809–834 (2011).

Francis, J. A., Chan, W., Leathers, D. J., Miller, J. R. & Veron, D. E. Winter Northern Hemisphere weather patterns remember summer Arctic sea ice extent. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L07503 (2009).

Gao, Y. Q. et al. Arctic sea ice and Eurasian climate: a review. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 32, 92–114 (2015).

Wu, Q. G. & Zhang, X. D. Observed forcing-feedback processes between northern hemisphere atmospheric circulation and Arctic sea-ice coverage. J. Geophys. Res. 115, D14199 (2010).

Liang, Y. et al. Impacts of Arctic Sea Ice on Cold Season Atmospheric Variability and Trends Estimated from Observations and a Multimodel Large Ensemble. J. Clim. 34, 8419–8443 (2023).

Jaiser, R., Dethloff, K., Handorf, D., Rinke, A. & Cohen, J. Impact of sea ice cover changes on the northern hemisphere atmospheric winter circulation. Tellus Ser. A Dyn. Meteorol. Oceanogr. 64, 11595 (2012).

Dunstone, N. et al. Skilful predictions of the winter North Atlantic Oscillation one year ahead. Nat. Geosci. 9, 809–814 (2016).

Kim, B. M. et al. Weakening of the stratospheric polar vortex by Arctic Sea-ice loss. Nat. Commun. 5, 4646 (2014).

Vihma, T. Effects of Arctic Sea ice decline on weather and climate: A review. Surv. Geophysics 35, 1175–1214 (2014).

Chen, Y. N., Luo, D. H., Zhong, L. H. & Yao, Y. Effects of Barents–Kara Seas ice and North Atlantic tripole patterns on Siberian cold anomalies. Weather Clim. Extremes 34, 100385 (2021).

Petoukhov, V. & Semenov, V. A. A link between reduced Barents-Kara Sea ice and cold winter extremes over northern continents. J. Geophys. Res. 115, D21111 (2010).

Inoue, J., Masatake, E. H. & Koutarou, T. The role of Barents Sea ice in the wintertime cyclone track and emergence of a warm-Arctic cold-Siberian anomaly. J. Clim. 25, 2561–2568 (2012).

Miles, M. W. et al. A signal of persistent Atlantic multidecadal variability in Arctic sea ice. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41, 463–469 (2014).

Stroeve, J. C. et al. The Arctic’s rapidly shrinking sea ice cover: A research synthesis. Climatic Change 110, 1005–1027 (2012).

Hansen, J., Ruedy, R., Sato, M. & Lo, K. Global surface temperature change. Rev. Geophys. 48, RG4004 (2010).

Li, F. & Wang, H. Autumn Sea Ice Cover, Winter Northern Hemisphere Annular Mode, and Winter Precipitation in Eurasia. J. Clim. 26, 3968–3981 (2012).

Li, F. & Wang, H. J. Autumn Eurasian snow depth, autumn Arctic sea ice cover and East Asian winter monsoon. Int. J. Climatol. 34, 3616–3625 (2014).

Li, F., Wang, H. J. & Gao, Y. Q. On the strengthened relationship between East Asian winter monsoon and Arctic Oscillation: A comparison of 1950–1970 and 1983–2012. J. Clim. 27, 5075–5091 (2014).

Song, Z. Y., Zhou, B. T., Xu, X. P. & Yin, Z. C. Interdecadal change in the response of winter North Atlantic Oscillation to the preceding autumn sea ice in the Barents-Kara Seas around the early 1990s. Atmos. Res. 297, 107123 (2024).

Thompson, D. W., Wallace, J. M. & Hegerl, G. C. Annular modes in the extratropical circulation. Part II: trends. J. Clim. 13, 1018–1036 (2000).

Honda, M., Inoue, J. & Yamane, S. Influence of low Arctic sea ice minima on anomalously cold Eurasian winters. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36, L08707 (2009).

Nakamura, T. et al. A negative phase shift of the winter AO/NAO due to the recent Arctic sea-ice reduction in late autumn. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 120, 3209–3227 (2015).

Sorokina, S. A., Li, C., Wettstein, J. J. & Kvamstø, N. G. Observed atmospheric coupling between Barents Sea ice and the warm-Arctic cold-Siberian anomaly pattern. J. Clim. 29, 495–511 (2016).

Lyu, Z. Z., Gao, H. & Li, H. X. The cooperative effects of November Arctic sea ice and Eurasian snow cover on the Eurasian surface air temperature in January–February. Int. J. Clim. 44, 4863–4885 (2024).

Cohen, J., Barlow, M., Kushner, P. J. & Saito, K. Stratosphere–troposphere coupling and links with Eurasian land surface variability. J. Clim. 20, 5335–5343 (2007).

Allen, R. J. & Zender, C. S. Effects of continental‐scale snow albedo anomalies on the wintertime Arctic oscillation. J. Geophys. Res. 115, D23105 (2010).

Siew, P. Y. F., Li, C., Sobolowski, S. P. & King, M. P. Intermittency of Arctic–mid-latitude teleconnections: stratospheric pathway between autumn sea ice and the winter North Atlantic Oscillation. Wea. Clim. Dyn. 1, 261–275 (2020).

Sheng, Z. et al. Dynamics, chemistry, and modelling studies in the aviation and aerospace transition zones. Innovation https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xinn.2025.101012 (2025).

Wang, M. & Tan, B. Two Types of the Scandinavian Pattern: Their Formation Mechanisms and Climate Impacts. J. Clim. 33, 2645–2661 (2020).

He, S. P. & Wang, H. J. Linkage between the East Asian January temperature extremes and the preceding Arctic Oscillation. Int. J. Climatol. 26, 1026–1032 (2016).

Kuroda, Y. & Kodera, K. Role of planetary waves in the stratosphere–troposphere coupled variability in the Northern Hemisphere winter. Geophys. Res. Lett. 26, 2375–2378 (1999).

Takaya, K. & Nakamura, H. Precursory changes in planetary wave activity for midwinter surface pressure anomalies over the Arctic. J. Meteor. Soc. Jpn. 86, 415–427 (2008).

Geng, Y., Ren, H., Ma, X., Zhao, S. & Nie, Y. Responses of East Asian climate to SST anomalies in the Kuroshio Extension region during boreal autumn. J. Clim. 35, 7007–7023 (2022).

Paeth, H., Latif, M. & Hense, A. Global SST influence on twentieth century NAO variability. Clim. Dyn. 21, 63–75 (2003).

Peng, S., Robinson, W. A. & Li, S. Mechanisms for the NAO Responses to the North Atlantic SST Tripole. J. Clim. 16, 1987–2004 (2003).

Fang, J. & Yang, X. Q. Structure and dynamics of decadal anomalies in the wintertime midlatitude North Pacific ocean-atmosphere system. Clim. Dyn. 47, 1989–2007 (2016).

Sampe, T., Nakamura, H., Goto, A. & Ohfuchi, W. Significance of a Midlatitude SST Frontal Zone in the Formation of a Storm Track and an Eddy-Driven Westerly Jet. J. Clim. 23, 1793–1814 (2010).

Xue, J. et al. Divergent Responses of Extratropical Atmospheric Circulation to Interhemispheric Dipolar SST Forcing over the Two Hemispheres in Boreal Winter. J. Clim. 31, 7599–7619 (2018).

Taguchi, B. et al. Seasonal Evolutions of Atmospheric Response to Decadal SST Anomalies in the North Pacific Subarctic Frontal Zone: Observations and a Coupled Model Simulation. J. Clim. 25, 111–139 (2012).

Piecuch, C. G. & Beal, L. M. Robust weakening of the Gulf Stream during the past four decades observed in the Florida Straits. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL105170 (2023).

Caesar, L. et al. Observed fingerprint of a weakening Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation. Nature 556, 191–196 (2018).

Chen, C., Wang, G., Xie, S. & Liu, W. Why Does Global Warming Weaken the Gulf Stream but Intensify the Kuroshio? J. Clim. 32, 7437–7451 (2019).

Chen, S. F. & Wu, R. G. Interdecadal Changes in the Relationship between Interannual Variations of Spring North Atlantic SST and Eurasian Surface Air Temperature. J. Clim. 30, 3771–3787 (2017).

Clement, A. et al. The Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation without a role for ocean circulation. Science 350, 320–324 (2015).

Sun, X. et al. Simulated Influence of the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation on Summer Eurasian Nonuniform Warming since the Mid-1990s. Adv. Atmos. Sci. 36, 811–822 (2019).

Seierstad, I. A. & Bader, J. Impact of a projected future Arctic Sea Ice reduction on extratropical storminess and the NAO. Clim. Dyn. 33, 937–943 (2009).

Song, X. L., Yin, Z. C. & Zhang, Y. J. Subseasonal reversals of winter surface air temperature in mid-latitude Asia and the roles of westward-shift NAO. Environ. Res. Lett. 18, 034018 (2023).

Song, X. L., Yin, Z. C. & Wang, H. J. Interdecadal Changes in the Links Between Late-winter NAO and North Atlantic Tripole SST and Possible Mechanism. Geophy. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL110138 (2024).

Shen, Z. et al. A frequent ice-free Arctic is likely to occur before the mid-21st century. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 103 (2023).

Rayner, N. A. et al. Global analyses of sea surface temperature, sea ice, and night marine air temperature since the late nineteenth century. Geophys. Res. 108, 4407 (2003).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. Roy. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Eyring, V. et al. Overview of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) experimental design and organization. Geosci. Model Dev. 9, 1937–1958 (2016).

Ackerley, D., Chadwick, R., Dommenget, D. & Petrelli, P. An ensemble of AMIP simulations with prescribed land surface temperatures. Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 3865–3881 (2018).

Peng, Y. et al. Tropical Cyclogenesis Bias over the Central North Pacific in CMIP6 Simulations. J. Clim. 37, 1231–1248 (2024).

Gates, W. L. et al. An overview of the results of the Atmospheric Model Intercomparison Project (AMIP I). Bull. Am. Meteor. Soc. 73, 1962–1970 (1999).

Taylor, K. E., Williamson, D. & Zwiers, F. The sea surface temperature and sea-ice concentration boundary conditions for AMIP II simulations, PCMDI Report No. 60, Program for Climate Model Diagnosis and Intercomparison, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Livermore, California, 25 pp. (2000).

Takaya, K. & Nakamura, H. A formulation of a phase-independent wave-activity flux for stationary and migratory quasigeostrophic eddies on a zonally varying basic flow. J. Atmos. Sci. 58, 608–627 (2001).

Yang, M. et al. The Siberian Storm Track Weakens the Warm Arctic–Cold Eurasia Pattern. J. Clim. 37, 673–688 (2023).

Taylor, K. E. Summarizing multiple aspects of model performance in a single diagram. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 106, 183–192 (2001).

Bretherton, C. S. et al. The effective numbers of spatial degrees of freedom of a time-varying field. J. Clim. 12, 1990–2009 (1999).

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely appreciate the editors and three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments that greatly improved the quality of this manuscript. In addition, the authors also thank Profs. Dachao Jin and Tingting Han for their helpful discussions. This study is jointly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 42105066, 42088101, 42205046), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2021M701754) and the Postdoctoral Research Funding of Jiangsu Province (2021K052A).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Z. and P.Y. conceived the study and wrote the initial paper. S.Z. conducted the analysis and prepared all figures. P.Y., B.S., H.W. and X.L. contributed to the interpretation of the results and the improvement of the manuscript. M. Y. and Y. L. provided critical feedback on the dynamic diagnosis and helped to revise the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, S., Yu, P., Sun, B. et al. Weakened relationship between November Barents-Kara sea ice and January Arctic Oscillation after the mid-1990s. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 294 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01186-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01186-7