Abstract

Arctic sea ice has undergone non-monotonic changes since the middle of the last century. Here, we investigate the cause of this behavior by isolating and quantifying the effects of anthropogenic aerosols, well-mixed greenhouse gases, and biomass burning on sea ice dynamics through climate model simulations. We find minimal changes in Arctic sea ice from 1956 to 1980, which largely reflect a balance between the warming effect of greenhouse gases and the cooling effect of aerosols. This balance, however, is disrupted in subsequent decades. Both sea ice area and volume exhibit marked declines between 1981 and 2005, owing primarily to intensified warming by greenhouse gases and a shift in aerosols’ role from mitigating to exacerbating sea ice loss. Our sea ice volume budget analysis demonstrates that sea ice changes since 1956 are mostly driven by thermodynamic processes: greenhouse gases significantly promote surface melting, whereas aerosols and biomass burning diminish surface melting by reducing surface shortwave radiation during boreal summer. From 1956–1980 to 1981–2005, the transitional effects of aerosols are associated with increased bottom ice melting and decreased bottom ice formation, which are primarily driven by changes in the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Arctic sea ice plays an essential role in Earth’s climate system, significantly influencing albedo, heat exchange, and both atmospheric and oceanic circulation patterns1,2,3,4,5,6. Earth’s climate has historically evolved under combined natural and anthropogenic forcings. To disentangle their relative contributions, Earth system model experiments—often termed single-forcing experiments—are conducted with selected forcings varied while others remain fixed7. Such experiments, especially when large ensembles are employed, form the basis for detection and attribution studies, including recent IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) conclusions of unequivocal human-induced warming8,9 and have been used extensively to attribute Arctic climate and sea ice changes to anthropogenic aerosols (AAER) and greenhouse gases (GHGs)10,11.

Since the late 1970s, satellite observations have documented a substantial decrease in the Arctic sea ice extent, with the most pronounced decline occurring in summer sea ice cover, particularly during September12,13,14. This decline is attributed mostly to rising well-mixed GHG emissions, which bring about intensified warming in the region10,15,16,17. Such amplified Arctic warming is not only a consequence but also a key driver of the observed sea ice retreat18,19. Historical reconstructions, however, show a contrasting trend, with sea ice extent increasing between the 1950s and the 1970s20,21,22. This earlier sea ice increase stems from the combined effects of increased AAER and natural climate variability, which temporarily counteracted GHGs warming through their cooling influences10,23,24. Since the 1980s, reductions in AAER emissions, especially in Europe and North America as a result of pollution control actions, are thought to have contributed to Arctic surface warming and accelerated sea ice loss25,26,27,28.

Unlike well-mixed GHGs, AAER exhibits pronounced temporal and spatial variability, which induces complex and regionally heterogeneous effects on Arctic sea ice29. Building on the historical influence of AAER on Arctic sea ice, understanding these effects is crucial, as further reductions in AAER in the coming decades are expected to profoundly alter Arctic sea ice30. In fact, AAER observation-constrained projections indicate that the probability of an ice-free Arctic could be moved forward by 10–35 years31. Biomass burning (BMB) emissions from forest fires, on the other hand, have also been suggested to have modified the rate of Arctic sea ice loss over recent decades32,33,34, adding another layer of complexity to the changes in the Arctic climate system. Nonetheless, the precise physical processes through which the aforementioned climate forcings affect Arctic sea ice are not yet fully understood. In this context, investigating the historical response of Arctic sea ice to various external forcing agents, along with the underlying physical mechanisms, is essential for improving future projections, and this forms the central focus of our study.

Results

Distinct effects of various climate forcings on Arctic sea ice

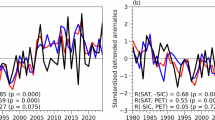

We leverage large ensemble historical all-forcing and single-forcing simulations (“Methods” section) with the Community Earth System Model version 1 (CESM1) and climate models in the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phases 5 and 6 (CMIP5&6), most of which include multiple ensemble members (see Table S1 for more details), to investigate the effects of various forcing agents on Arctic sea ice. We examine Arctic sea ice area and volume during two key periods, 1956–1980 and 1981–2005, which are influenced by climate forcings in distinct ways (Fig. 1)12,13,14,20,21,22. Between 1956 and 1980, the CESM1 historical all-forcing ensemble depicts minimal changes in total annual mean Arctic sea ice area and volume, consistent with observations (Fig. 1a, b), and also indicates an insignificant trend in either of them (see Tables S2, S3).

a Annual mean sea ice area (SIA) and b sea ice volume (SIV) anomalies (relative to 1920–1945) during 1920–2005 for CESM1 historical ensemble mean (HIST: black line), CMIP5 & CMIP6 multi-model mean (CMIP5 & 6 MMM; brown), and observations by Walsh et al.67 (yellow), and contributions from well-mixed greenhouse gases (GHGs: orange for CESM1 ensemble mean, red for CMIP5 & CMIP6 MMM), anthropogenic aerosols (AAER: blue for CESM1 ensemble mean, purple for CMIP5 & CMIP6 MMM), and biomass burning (BMB: green for CESM1 ensemble mean). Light-colored shading represents one standard deviation across ensemble members for each simulation. CMIP5 & CMIP6 MMM is derived from four CMIP5 and nine CMIP6 models (see Table S1 for more details).

In terms of forcing agents, GHGs cause a significant decrease in sea ice, while AAER brings about a significant increase. Our findings align with previous studies10,23,24, showing opposing effects of GHGs and AAER during 1956–1980 counterbalancing each other and leading to a minimal change in Arctic sea ice. BMB, meanwhile, also contributes to sea ice growth, albeit to a lesser extent than AAER does. The BMB-driven increase in sea ice area during this period is statistically insignificant, whereas the increase in sea ice volume is significant (see Tables S2, S3).

The multi-model ensemble mean (i.e., averaged over each model’s ensemble-mean trend) of 4 CMIP5 and 9 CMIP6 models (“Methods” section) supports the CESM1 result, with more than half of the models presenting insignificant trends in historical Arctic sea ice area and volume. This further underscores the opposing effects of changing GHGs and AAER on Arctic sea ice (Fig. 1a, b). Note that these CMIP5 and CMIP6 ensembles do not include BMB-only experiments.

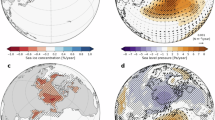

The spatial pattern of annual mean linear trends of sea ice concentration from 1956 to 1980 in CESM1 reveals compensation between GHG-induced decreases and AAER-induced increases in the Beaufort, Chukchi, East Siberian, and Kara–Barents Seas, as well as the marginal seas in the North Pacific (Fig. 2b, c). Such cancellation explains the small changes in these areas when all climate forcings are included (Fig. 2a). Over the Greenland Sea, however, the AAER forcing produces a substantially larger sea ice increase than the GHGs-induced decrease, implying that additional processes also influence the net HIST response. The annual mean linear trends of sea ice thickness show a similar pattern of strongly compensating effects from GHGs and AAER in the Beaufort, Chukchi, and East Siberian Seas, and are particularly pronounced over the central Arctic Ocean (Fig. 2f, g). By comparing trends in both concentration and thickness, we capture the differing sensitivities of the marginal ice zone and the interior ice pack to external forcings. Notably, annual mean linear trends of surface air temperature indicate warming by GHGs in regions experiencing large sea ice decline and cooling by AAER in regions with marked sea ice increase (Fig. S1b, c). These temperature changes not only reflect the effects of the forcing agents but also likely contribute to further sea ice change via ice-albedo feedback, amplifying sea ice loss under GHGs-induced warming17,18 and promoting ice retention under AAER-induced cooling.

Linear trends from 1956 to 1980 of annual and ensemble mean a–d sea ice concentration (shading in % decade−1) and e–h sea ice thickness (shading in m decade−1) in the Arctic, a, e under historical climate forcings (HIST), only driven by (b, f) well-mixed greenhouse gases (GHGs), c, g anthropogenic aerosols (AAER), or d, h biomass burning (BMB).

In contrast, linear trends during the period 1981–2005 are strongly negative in the CESM1 all-forcing ensemble for both Arctic sea ice area and volume, which is consistent with the CMIP5&6 multi-model mean, as well as observations from the perspective of sea ice area (Fig. 1a, b; Tables S2, S3). Both GHGs and AAER account for this decline: GHGs induce a significant decrease, while AAER leads to a smaller but still significant decrease. BMB elicits a relatively minor but significant increase for both Arctic sea ice area and volume. The CMIP5&6 multi-model mean evinces similar effects from GHGs and AAER as in CESM1, but with weaker trends in sea ice area and volume, likely due to the strong influence of internal climate variability16.

Spatially, GHGs and AAER both lead to large reductions in sea ice concentration during 1981–2005 across the Arctic, including the Beaufort, Chukchi, East Siberian, Laptev, and Kara–Barents Seas, as well as the marginal seas in the North Pacific (Fig. 3b, c). Some of these GHGs- and AAER-induced sea ice declines are partially offset by BMB-induced sea ice increases (Fig. 3d). Likewise, trends in sea ice thickness show a significant decline near the East Siberian Sea due to a combined effect of GHGs and AAER, while BMB contributes to a modest increase around the Beaufort Sea (Fig. 3e–h). It is noteworthy that the annual mean linear trends of surface air temperature during this period manifest not only the direct effects of the forcing agents but also the amplifying role of ice-albedo feedback, as in the previous period. The strong GHG-induced surface warming (Fig. S1f), combined with a positive ice-albedo feedback, accelerates the sea ice loss over the Arctic. On the other hand, a transition from cooling to a warming effect by AAER (Fig. S1g) likely comes from reduced AAER emissions, along with a warming influence that triggers a positive ice-albedo feedback. Meanwhile, a general cooling over the Arctic associated with BMB (Fig. S1h) promotes sea ice formation.

Linear trends from 1981 to 2005 of annual and ensemble mean a–d sea ice concentration (shading in % decade−1) and e–h sea ice thickness (shading in m decade−1) in the Arctic (a, e) under historical climate forcings (HIST), b, f only driven by well-mixed greenhouse gases (GHGs), c, g anthropogenic aerosols (AAER), or d, h biomass burning (BMB).

Physical mechanisms

To investigate the physical processes by which climate forcings drive changes in Arctic sea ice, we look into a sea ice volume budget, taking into account both dynamic and thermodynamic terms (Figs. 4, 5; “Methods” section). The dynamic term (dvidtd) accounts for sea ice volume changes induced by divergence/convergence and sea ice drift, while the thermodynamic term (dvidtt) reflects changes due to ice formation and melting processes. The thermodynamic term can be further decomposed into six components: ice formation over open ocean areas (frazil) and at the base (congel), conversion of snow to ice (snoice), ice melting at the top (meltt) and base (meltb), as well as lateral edge melting (meltl)35,36.

a Left: integrated annual and ensemble mean Arctic sea ice volume tendency terms for the period 1956–1980, with the left y-axis representing values under historical climate forcings (HIST: black bars) and the right y-axis showing the relative contributions from well-mixed greenhouse gases (GHGs: orange bars), anthropogenic aerosols (AAER: blue bars), and biomass burning (BMB: green bars). Note that values on the right y-axis are scaled down by a factor of 10 compared to the left y-axis. Right: the net sea ice volume tendency under HIST (black), GHGs (orange), AAER (blue), and BMB (green) forcings. Annual and ensemble mean net sea ice volume tendencies (shading in 10−2 km3 month−1) caused by b HIST, c GHGs, d AAER, and e BMB forcings.

a Left: integrated annual and ensemble mean Arctic sea ice volume tendency terms for the period 1981–2005, with the left y-axis representing values under historical climate forcings (HIST: black bars) and the right y-axis showing the relative contributions from well-mixed greenhouse gases (GHGs: orange bars), anthropogenic aerosols (AAER: blue bars), and biomass burning (BMB: green bars). Note that values on the right y-axis are scaled down by a factor of 10 compared to the left y-axis. Right: the net sea ice volume tendency under HIST, GHGs, AAER, and BMB forcings. Colors and y-axis scales follow those in the left panel. Annual and ensemble mean net sea ice volume tendencies (shading in 10−2 km3 month−1) caused by b HIST, c GHGs, d AAER, and e BMB forcings.

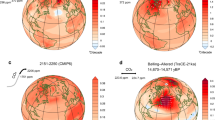

We first assess the integrated annual mean tendency of Arctic sea ice volume. From 1956 to 1980, the CESM1 all-forcing simulation displays a positive tendency, indicating a net increase in Arctic sea ice volume, due in part to compensation between the strong increase from AAER and the weaker decrease from GHGs (Fig. 4a). Further decomposition of the thermodynamic terms reveals that the effects of both changing GHGs and AAER primarily operate through alterations in the melting processes at the top surface of the ice, with GHGs leading to enhanced melting and AAER to diminished melting (Fig. 4a). These processes predominantly occur during boreal summer (Fig. S2). The increase in sea ice attributed to AAER is partially offset by reduced ice formation at the ice base (Fig. 4a), which occurs in boreal fall and winter (Fig. S2e).

Seen from spatial patterns, AAER produces an overall positive sea ice volume tendency in the Arctic basin, with stronger increases in the Chukchi and East Siberian Seas (Fig. 4d). GHGs, on the other hand, produce a negative sea ice volume tendency in the Arctic basin, with more pronounced declines in the Beaufort, Chukchi, and East Siberian Seas (Fig. 4c). Compared with the other two forcings, BMB generates much smaller sea ice volume tendencies with complex spatial patterns (Fig. 4e). As a result, the CESM1 all-forcing ensemble witnesses a net increase in sea ice volume in the Arctic basin, especially over the Chukchi Sea (Fig. 4b). These net tendencies result from a compensation between thermodynamic and dynamic contributions. The thermodynamic processes dominate the dynamic processes in the Arctic basin, whereas dynamic processes associated with ice convergence and divergence play a leading role around the Bering Strait and over the marginal seas in both the North Atlantic and Pacific (Fig. S4).

Between 1981 and 2005, CESM1 simulates a negative tendency in Arctic sea ice volume owing to either GHGs or AAER, with a slight offset from the moderate increase due to BMB (Fig. 5b–e). Both GHGs and AAER promote negative sea ice volume tendencies generally over the Arctic basin, with more conspicuous declines in the East Siberian Sea (Fig. 5c, d). On the contrary, BMB induces positive tendencies in the Beaufort and East Siberian Seas but negative tendencies in the Chukchi Sea (Fig. 5e). During this period, interactions between thermodynamic and dynamic contributions are more complex. In the Arctic basin, the thermodynamic contribution slightly outweighs the dynamic term for GHGs and BMB (Fig. S5b, d, f, h), whilst the dynamic contribution plays a more significant role for AAER (Fig. S5c, g). The pronounced dynamic effect under AAER forcing largely stems from thicker, more consolidated ice being advected by a strengthened East Greenland Current, which contributes to a sea ice accumulation southeast of Greenland (Figs. S5c, S6c). Consequently, in the historical all-forcing simulation, the dynamic contribution dominates over this region (Fig. S5a, e). Such an outcome may also reflect additional factors or nonlinear interactions among forcings that are not fully captured by the separate single-forcing simulations. Meanwhile, dynamic processes continue to dominate the net tendencies over the marginal seas in both the North Atlantic and Pacific (Fig. S5).

Our decomposition of the thermodynamic term indicates that, over 1981–2005, the GHGs' effect on sea ice volume is mainly through enhanced ice melting at the top-surface and is partly compensated by reduced ice melting at the base. AAER reduces ice melting at the top-surface and base during summer (Figs. 5a and S3e). However, AAER’s influence, which abates ice formation and promotes melting at the base during non-summer months, results in an overall negative impact on sea ice, occurring throughout most of the year. On the other hand, the BMB effect on sea ice volume manifests as reduced ice melting processes at the top-surface during summer (Figs. 5a and S3f).

We further probe the net sea ice volume tendencies at both the ice top-surface and base, combining this analysis with surface heat fluxes and ocean heat budgets to identify the physical processes by which various forcing agents drive Arctic sea ice change. During boreal summer (June–July–August, JJA), when solar radiation dominates the surface energy budget, the CESM1 historical all-forcing simulation depicts a net ice loss (negative top-surface sea ice volume tendencies) from 1956 to 1980 over the Beaufort, Chukchi, East Siberian, and Kara Seas (Fig. 6a). Over these regions, the net top-surface sea ice volume tendencies are weakly negative under GHGs forcing and are accompanied by a moderate increase in net surface shortwave radiation, which is largely due to reduced upward shortwave radiation from declining surface albedo (Fig. 6b, f). Concurrently, downward longwave radiation increases modestly, supplying additional heat to the surface and further reinforcing ice melting (Fig. S7f). Conversely, the net top-surface sea ice volume tendencies are positive under AAER forcing, along with a substantial reduction in net surface shortwave radiation due to the direct aerosol effect, which scatters the incoming shortwave radiation and cools the surface atmosphere35,37 (Fig. 6c, g). Meanwhile, AAER enlarges low-level cloud fraction over the Arctic, trapping additional longwave radiation and causing a net positive longwave anomaly (Fig. S9c and Fig. S7c, o) that slightly offsets the AAER-induced shortwave cooling.

Boreal summer (JJA) ensemble mean of (a–d) net sea ice volume tendencies at the top (frazil + meltt, shading in 10−1 km3 month−1) and e–h surface net shortwave radiation fluxes (positive downward, shading in W m−2) for the period 1956–1980 under (a, e) historical climate forcings (HIST), only driven by (b, f) well-mixed greenhouse gases (GHGs), c, g anthropogenic aerosols (AAER), or d, h biomass burning (BMB).

In addition, these net tendencies are not solely determined by direct radiative effects of the forcing agents. Changes in the physical state of ice further modulate its response through key feedback mechanisms15,38,39. Under GHG forcing, thinner ice and retreating margins intensify the ice-albedo feedback, driving further melting. GHG-induced increase in downward longwave radiation compounds this effect, leaving ice exceptionally thin. In contrast, AAER forcing tends to preserve thicker ice cover, insulating the ocean and slowing both surface and basal melting. Although AAER-driven cloud brightening produces strong negative shortwave-cloud effects over mid-to-subpolar latitudes, they are minimal within the Arctic basin (Fig. S7k). Together, these feedbacks magnify the divergent impacts of the forcing agents on Arctic sea ice.

Between 1981 and 2005, CESM1 simulates similar annual mean net top-surface sea ice tendencies during boreal summer to those in the previous period but with a different magnitude. GHGs forcing now drives a larger net top-surface ice loss as surface albedo reduction intensifies (Fig. 7b, f), while the increase in downward longwave radiation is more pronounced (Fig. S8f), further boosting ice melting. Reduced AAER emissions diminish the direct scattering of shortwave radiation so that the reduction in net surface shortwave radiation becomes smaller (Fig. 7g). The slight positive longwave anomaly in the central Arctic seen in 1956–1980—attributable to aerosol-driven longwave-cloud effects—weakens and becomes near zero with a dimmer longwave-cloud effect (Fig. S8c, o and Fig. S9g), together diminishing net ice growth (Fig. 7c). Thus, under intensified GHGs forcing, the ice-albedo feedback becomes even more effective at driving ice loss, whilst the insulating effect of thicker ice under AAER forcing weakens, undermining its ability to offset melting. In the meantime, BMB yields slightly positive net top-surface sea ice volume tendencies over the Chukchi and East Siberian Seas, consistent with a relatively smaller reduction in net surface shortwave radiation (Fig. 7d, h).

Boreal summer (JJA) ensemble mean of (a–d) net sea ice volume tendencies at the top (frazil + meltt, shading in 10−1 km3 month−1) and e–h surface net shortwave radiation fluxes (positive downward, shading in W m−2) for the period 1981–2005 under (a, e) historical climate forcings (HIST), only driven by (b, f) well-mixed greenhouse gases (GHGs), c, g anthropogenic aerosols (AAER), or d, h biomass burning (BMB).

The CESM1 all-forcing simulation, on the other hand, depicts relatively weak positive annual mean net sea ice volume tendencies at the ice base over the Arctic basin from 1956 to 1980, but much stronger negative tendencies in marginal ice zones, such as the Bering, Barents, and Labrador Seas, as well as the area to the south of Greenland (Fig. 8a). These negative sea ice volume tendencies are mostly associated with oceanic heat convergence induced by ocean circulation, and warming tendencies (Fig. 8e) in both the Atlantic and Pacific sectors (Fig. 8a, e).

Annual and ensemble mean of (a–d) net sea ice volume tendencies at the bottom (congel + meltb, shading in 10−1 km3 month−1) and e–h whole-depth ocean temperature tendencies induced by advection and diffusion processes (shading in 10−3 cm °C s−1) for the period 1956–1980 under a, e historical climate forcings (HIST), only driven by b, f well-mixed greenhouse gases (GHGs), c, g anthropogenic aerosols (AAER), or d, h biomass burning (BMB).

Sea ice tendencies in the above regions may also be affected by dynamic ice processes through ice convergence and divergence (Fig. S4a, e). GHGs prompt negative sea ice volume tendencies over the central Arctic and positive tendencies in the marginal seas, accompanied by cooling tendencies in ocean temperatures in the Atlantic sector. The oceanic cooling primarily results from a GHG-induced slowdown of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation (AMOC)40,41 (Fig. S10). Such an AMOC-induced “cold patch” is intimately linked to the Gulf Stream pathway41,42,43. In CESM1 with a nominal 1° ocean (“Methods” section), the magnitude of oceanic cooling and its impact on sea ice may differ in a high-resolution model, given that model resolution has been suggested to play a critical role in shaping the Gulf Stream pathway44,45.

In contrast to GHGs, AAER engenders strong positive sea ice volume tendencies over the Beaufort and Kara–Barents Seas but negative tendencies in marginal ice zones of both the Pacific and Atlantic sectors (Fig. 8c). Such a pattern corresponds to warming in ocean temperature in the subpolar Atlantic caused by AAER-induced AMOC strengthening46,47 (Figs. 8g and S10), a mechanism evident across models and resolutions, and aligned with analyses of multidecadal internal variability44. Another note is that the CESM1 simulations are driven by CMIP5 external climate forcings, whilst CMIP5 and CMIP6 prescribe different historical forcing reconstructions48, especially in AAER. Thereupon, the simulated AMOC change41,49 and AMOC fingerprint50 may differ across model generations49.

Between 1981 and 2005, GHGs further enhanced the oceanic heat divergence and cooling in ocean temperature over the subpolar Atlantic (Fig. 9f) and thus promoted the positive sea ice volume tendencies in the region. Meanwhile, AAER slightly amplifies the negative sea ice volume tendencies in the subpolar Atlantic (Fig. 9c) by increasing ocean heat convergence there (Fig. 9g). Note that while the strength of the AMOC shows a declining trend due to AAER reduction during this period, its average strength remains higher than the average of the previous period (Fig. S10). This finding aligns with prior work47 identifying 1970 as a transition point in AAER’s influence on the AMOC, with the AAER-induced strengthening persisting into the early decades of the twenty-first century. Compared to GHGs and AAER, BMB has the least impact on sea ice volume trends at the ice base from 1956 to 2005 (Figs. 8d and 9d). Besides thermodynamics, regional sea ice volume tendencies during this period can also be notably influenced by dynamic processes (Fig. S5).

Annual and ensemble mean of a–d net sea ice volume tendencies at the bottom (congel + meltb, shading in 10−1 km3 month−1) and e–h whole-depth ocean temperature tendencies induced by advection and diffusion processes (shading in 10−3 cm °C s−1) for the period 1981–2005 under (a, e) historical climate forcings (HIST), only driven by (b, f) well-mixed greenhouse gases (GHGs), c, g anthropogenic aerosols (AAER), or d, h biomass burning (BMB).

To elucidate the mechanisms for seasonal sea ice change, we look into ocean heat budgets for boreal summer (JJA) and winter (December–January–February, DJF), respectively. We find that AAER-induced AMOC strengthening leads to year-round enhanced ocean heat convergence over the subpolar Atlantic (Figs. S11c, S12c), which becomes even stronger during 1981–2005 due to delayed oceanic adjustments (Figs. S10, S13c, S14c). In summer, this enhanced convergence is offset by substantial upward heat flux to the atmosphere (Fig. S11g), yielding a net cooling tendency in ocean temperatures north of 60°N that favors sea ice growth (Fig. S11k). While in winter, weaker surface heat loss allows continued ocean heat convergence to warm the interior ocean water (Fig. S12c, g, k), resulting in reduced basal ice formation and even promoting basal melting (Figs. S2c, S3c). Under GHG forcing, the AMOC weakening brings about a year-round ocean heat divergence, enhancing summer ocean warming by absorbing more heat from the atmosphere and intensifying ice melting, while amplifying wintertime ocean cooling, thus favoring increased basal ice formation despite an annual ice-thinning trend (Figs. S2, 3, S11–14, and 2, 3). These results clearly demonstrate that the non-local ocean effect by ocean circulation change, rather than the direct local radiative effect, predominantly governs the seasonal Arctic sea ice variations under AAER and GHGs forcings.

Discussion

In this study, we investigate the distinct roles of different forcing agents in shaping Arctic sea ice dynamics using the CESM1 all-forcing and single-forcing large ensemble historical simulations. We discover that Arctic sea ice remains relatively stable from 1956 to 1980, owing primarily to a balance of opposing effects from GHGs and AAER. This balance is upset in subsequent decades, resulting in a rapid decline in sea ice over 1981–2005. This shift can be attributed to the enhanced warming effects of GHGs and the decline in AAER emissions from 1981 to 2005, which elicits a transition in the role of AAER from mitigating to exacerbating sea ice loss. We further identify that all climate forcings significantly influence ice melting processes at the top-surface during boreal summer. GHGs strongly promote sea ice melt at the top surface, whereas both AAER and BMB reduce it. The shifting role of AAER between 1981 and 2005 is attributed to its growing negative impacts on both the melting and formation processes at the ice base, which could be linked to the strengthened AMOC and persistent ocean warming in the subpolar North Atlantic. Additionally, the reduction in AAER emissions during this period increases the incoming shortwave radiation over the Arctic basin, also promoting ice melting at the surface. Our findings suggest that Arctic sea ice responses to external forcings involve both fast adjustments through surface radiative fluxes and longer-term impacts via changes in ocean circulation.

Aside from AAER, BMB, and well-mixed GHGs, other factors included within the CESM1 all-forcing simulations—such as natural climate variability10,24, anthropogenic changes in atmospheric ozone51,52,53, and ozone-depleting substances51,52,53—can modulate Arctic sea ice, although their effects are generally weaker than those of AAER and GHGs23,24,51. In particular, solar cyclic variability can affect Arctic sea ice throughout the winter months54.

One may notice that the strength and spatial pattern of AAER forcing in the Arctic strongly depend on aerosol lifetimes during long-range transport, which are controlled by dry deposition rates of aerosol precursors (e.g., sulfur dioxide) over snow and ice. Uncertainties in dry deposition can therefore substantially alter Arctic aerosol loads and cooling efficacy55,56. In addition, the deposition of black carbon onto Arctic snow and ice can significantly reduce surface albedo, enhancing solar absorption and surface warming57. Previous research has suggested that this mechanism can produce Arctic warming effects comparable in magnitude to those driven by carbon dioxide58. As CESM1 does not explicitly simulate the radiative impacts of black carbon deposition, the warming influence identified in our simulations may be conservative59. Moreover, the various climate forcings may have a complex and nonlinear interplay60,61. Understanding the nuanced interactions among climate forcings and their physical processes, including critical feedback mechanisms and polar amplification, is of central importance in governing sea ice dynamics. As the Arctic continues to change, ongoing monitoring and modeling efforts will be critical for accurately predicting future sea ice conditions.

Methods

Climate model and simulation

To isolate and quantify the responses of Arctic sea ice to various forcing agents, we employed CESM1 large ensemble all-forcing historical (HIST)62 and accompanying single-forcing simulations7 (Table S1). The fully coupled CESM1 consists of Community Atmosphere Model version 5 (CAM5), Parallel Ocean Program version 2 (POP2), Community Land Model version 4 (CLM4), and Los Alamos Sea Ice Model (CICE) as described in detail in Hurrell et al.63, configured at nominal ~1° horizontal resolution (CAM5 on ~0.9° × 1.25° for atmosphere; POP2/CICE on a nominal ~1° grid), and the single-forcing simulations follow the same grid. The all-forcing ensemble consists of 40 ensemble members62, each of which is subject to the same historical forcing protocol but begins from slightly different initial conditions on 1st January 192062. The single-forcing ensembles use an “all but” approach in which the forcing agent of interest is fixed at its 1920 level, while all other forcings vary over time7. There are three single-forcing ensembles: the fixed AAER forcing simulation (xAER) with 20 ensemble members, the fixed GHGs forcing simulation (xGHG) with 20 ensemble members, and the fixed BMB forcing simulation (xBMB) with 15 ensemble members. Following the methodology outlined in ref. 7, we calculate the difference between the ensemble mean of the all-forcing and single-forcing simulations to quantify the effects of AAER (HIST minus xAER), GHGs (HIST minus xGHG), and BMB (HIST minus xBMB). Note here, these climate forcings may interact in a complex and nonlinear manner60,61.

We also harness available CMIP5 and CMIP6 historical, GHG-only, and AAER-only simulations64,65 (Table S1). Differences in historical forcings between CMIP5 and CMIP6 can lead to different effective radiative forcing, ocean, and sea ice responses41,48,49,50,66. These CMIP5 and CMIP6 models adopt the “only” approach for single-forcing simulations, in which only the specific forcing (i.e., well-mixed GHGs or AAER) evolves over time during the historical period. Despite the difference in approaches between CMIP5&6 models and CESM1, we discover that their results are fairly consistent.

We include both CMIP5 and CMIP6 models to evaluate the robustness of Arctic sea ice responses across generations of climate models. The use of CESM1 rather than CESM2 is motivated by recent studies34,60 showing that CESM2 exhibits greater sensitivity and nonlinear responses to external forcings—particularly in the Arctic—due to its higher climate sensitivity and differing initial sea ice states. The large ensemble size of CESM1, meanwhile, helps to reduce internal variability, which is particularly influential in the Arctic, and supports the identification of externally forced signals.

Observation

We utilize the Arctic sea ice area products that integrate various historical observations, including ship reports, compilations from naval oceanographers, analyses conducted by national ice services, and satellite passive microwave data, among other sources67. The data are provided as monthly sea ice concentration on a 0.25° × 0.25° longitude and latitude grid poleward of 30°N. Although the dataset extends back to 1850, our analysis focuses on the period from 1920 to 2005, aligning with the timeframe of the CESM1 simulations employed in this research.

Sea ice volume budget

We examine the sea ice volume budget that is based on the continuity equation:

where h denotes the mean ice thickness over a grid cell and \(\vec{u}\) denotes sea ice velocity. \({\Gamma }_{h}\) is the thermodynamic source term, and \(-\nabla \left(\vec{u}h\right)\) is the dynamic term, i.e., sea ice redistribution due to dynamic processes68. The thermodynamic source term \({\Gamma }_{h}\) can be further decomposed into six terms: basal growth (congel), frazil growth (frazil), snow-ice conversion (snoice), basal melt (meltb), top melt (meltt), and lateral melt (meltl)35. Integrated over the Northern Hemisphere, the dynamic term equals zero, meaning that sea ice redistribution makes a zero net contribution to the total Arctic sea ice volume in the hemisphere.

The AMOC and associated oceanic processes

We define AMOC strength as the maximum of the annual mean meridional overturning stream-function below 500 m in the North Atlantic. Changes in the AMOC can affect ocean temperatures in the North Atlantic through advection and diffusion processes. This is represented by \({{tendency}}_{{adv}+{diff}}\), which is the vertically integrated ocean temperature advection and diffusion tendency per unit area.

Significance test

The linear trend r is tested with Student t-distribution with n-2 degrees of freedom:

where n represents the number of years (n = 25 in this study).

Data availability

The observational sea ice data is available at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (https://nsidc.org/data/g10010/versions/2). The CESM1 Large Ensemble simulations used in this study are available from https://www.cesm.ucar.edu/working-groups/climate/simulations/cesm1-single-forcing-le and https://www.cesm.ucar.edu/community-projects/lens. The CMIP5 and 6 datasets are available at the Earth System Grid Federation portal (https://aims2.llnl.gov/search).

References

Cohen, J. et al. Recent Arctic amplification and extreme mid-latitude weather. Nat. Geosci. 7, 627–637 (2014).

Serreze, M. C. & Barry, R. G. The Arctic Climate System (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014).

Curry, J. A., Schramm, J. L. & Ebert, E. E. Sea ice-albedo climate feedback mechanism. J. Clim. 8, 240–247 (1995).

Deser, C., Tomas, R. A. & Sun, L. The role of ocean–atmosphere coupling in the zonal-mean atmospheric response to Arctic sea ice loss. J. Clim. 28, 2168–2186 (2015).

Vihma, T. Effects of Arctic sea ice decline on weather and climate: a review. Surv. Geophy.s 35, 1175–1214 (2014).

Liu, W., Fedorov, A. & Sévellec, F. The mechanisms of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation slowdown induced by Arctic sea ice decline. J. Clim. 32, 977–996 (2019).

Deser, C. et al. Isolating the evolving contributions of anthropogenic aerosols and greenhouse gases: a new CESM1 large ensemble community resource. J. Clim. 33, 7835–7858 (2020).

IPCC. Summary for policymakers. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis (ed. Masson-Delmotte, V.) 3–32 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2021).

Gillett, N. P. et al. Constraining human contributions to observed warming since the pre-industrial period. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 207–212 (2021).

Mueller, B. L., Gillett, N. P., Monahan, A. H. & Zwiers, F. W. Attribution of Arctic sea ice decline from 1953 to 2012 to influences from natural, greenhouse gas, and anthropogenic aerosol forcing. J. Clim. 31, 7771–7787 (2018).

England, M. R., Eisenman, I., Lutsko, N. J. & Wagner, T. J. W. The recent emergence of Arctic amplification. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094086 (2021).

Serreze, M. C., Holland, M. M. & Stroeve, J. Perspectives on the Arctic’s shrinking sea-ice cover. Science 315, 1533–1536 (2007).

Stroeve, J., Holland, M. M., Meier, W., Scambos, T. & Serreze, M. Arctic sea ice decline: Faster than forecast. Geophys. Res.Lett. 34, L09501 (2007).

Serreze, M. C. & Stroeve, J. Arctic sea ice trends, variability and implications for seasonal ice forecasting. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A: Math., Phys. Eng. Sci. 373, 20140159 (2015).

Holland, M. M., Bitz, C. M. & Tremblay, B. Future abrupt reductions in the summer Arctic sea ice. Geophys. Res. Lett. 33, L23503 (2006).

Stroeve, J. C. et al. Trends in Arctic sea ice extent from CMIP5, CMIP3 and observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L16502 (2012).

Notz, D. & Marotzke, J. Observations reveal external driver for Arctic sea-ice retreat. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L08502 (2012).

Screen, J. A. & Simmonds, I. The central role of diminishing sea ice in recent Arctic temperature amplification. Nature 464, 1334–1337 (2010).

Pithan, F. & Mauritsen, T. Arctic amplification dominated by temperature feedbacks in contemporary climate models. Nat. Geosci. 7, 181–184 (2014).

Meier, W. N., Stroeve, J. & Fetterer, F. Whither Arctic sea ice? A clear signal of decline regionally, seasonally and extending beyond the satellite record. Ann. Glaciol. 46, 428–434 (2007).

Mahoney, A. R., Barry, R. G., Smolyanitsky, V. & Fetterer, F. Observed sea ice extent in the Russian Arctic, 1933–2006. J.Geophys. Res. Oceans 113, C11005 (2008).

Semenov, V. A. & Latif, M. The early twentieth century warming and winter Arctic sea ice. Cryosphere 6, 1231–1237 (2012).

Kong, N. & Liu, W. Unraveling the Arctic sea ice change since the middle of the twentieth century. Geosciences 13, 58 (2023).

Gagné, M. -È, Fyfe, J. C., Gillett, N. P., Polyakov, I. V. & Flato, G. M. Aerosol-driven increase in Arctic sea ice over the middle of the twentieth century. Geophys. Res. Lett. 44, 7338–7346 (2017).

Shindell, D. & Faluvegi, G. Climate response to regional radiative forcing during the twentieth century. Nat. Geosci. 2, 294–300 (2009).

Acosta Navarro, J. C. et al. Amplification of Arctic warming by past air pollution reductions in Europe. Nat. Geosci. 9, 277–281 (2016).

Ren, L. et al. Source attribution of Arctic black carbon and sulfate aerosols and associated Arctic surface warming during 1980–2018. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 20, 9067–9085 (2020).

Breider, T. J. et al. Multidecadal trends in aerosol radiative forcing over the Arctic: contribution of changes in anthropogenic aerosol to Arctic warming since 1980. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 122, 3573–3594 (2017).

Wang, Y. et al. Elucidating the role of anthropogenic aerosols in Arctic sea ice variations. J. Clim. 31, 99–114 (2018).

Gagné, M. -È, Gillett, N. P. & Fyfe, J. C. Impact of aerosol emission controls on future Arctic sea ice cover. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 8481–8488 (2015).

Bonan, D. B., Schneider, T., Eisenman, I. & Wills, R. C. J. Constraining the date of a seasonally ice-free Arctic using a simple model. Geophys Res Lett. 48, e2021GL094309 (2021).

Schmeisser, L. et al. Seasonality of aerosol optical properties in the Arctic. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 18, 11599–11622 (2018).

Schmale, J., Zieger, P. & Ekman, A. M. L. Aerosols in current and future Arctic climate. Nat. Clim. Chang. 11, 95–105 (2021).

DeRepentigny, P. et al. Enhanced simulated early 21st century Arctic sea ice loss due to CMIP6 biomass burning emissions. Sci. Adv. 8, eabo2405 (2022).

Holland, M. M., Bailey, D. A., Briegleb, B. P., Light, B. & Hunke, E. Improved sea ice shortwave radiation physics in CCSM4: the impact of melt ponds and aerosols on Arctic sea ice*. J. Clim. 25, 1413–1430 (2012).

Lee, Y.-C. & Liu, W. The weakened Atlantic meridional overturning circulation diminishes recent Arctic sea ice loss. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL105929 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Scattering and absorbing aerosols in the climate system. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 363–379 (2022).

Massonnet, F. et al. Arctic Sea-ice change tied to its mean state through thermodynamic processes. Nat. Clim. Chang. 8, 599–603 (2018).

Bitz, C. M. & Roe, G. H. A mechanism for the high rate of sea ice thinning in the Arctic Ocean. J. Clim. 17, 3623–3632 (2004).

Liu, W., Fedorov, A. V., Xie, S.-P. & Hu, S. Climate impacts of a weakened Atlantic meridional overturning circulation in a warming climate. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz4876 (2020).

Li, K.-Y. & Liu, W. Weakened Atlantic meridional overturning circulation causes the historical North Atlantic warming hole. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 416 (2025).

Caesar, L., Rahmstorf, S., Robinson, A., Feulner, G. & Saba, V. Observed fingerprint of a weakening Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation. Nature 556, 191–196 (2018).

Mimi, M. S. & Liu, W. Atlantic meridional overturning circulation slowdown modulates wind-driven circulations in a warmer climate. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 727 (2024).

Meccia, V. L. et al. Internal multi-centennial variability of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation simulated by EC-Earth3. Clim. Dyn. 60, 3695–3712 (2023).

Frigola, A. et al. The North Atlantic mean state in eddy-resolving coupled models: a multimodel study. EGUsphere 2025, 1–34 (2025).

Chen, D., Sun, Q. & Fu, M. Aerosol in the subarctic region impacts on Atlantic meridional overturning circulation under global warming. Clim. Dyn. 62, 9539–9548 (2024).

Allen, R. J., Vega, C., Yao, E. & Liu, W. Impact of industrial versus biomass burning aerosols on the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. NPJ Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 58 (2024).

Fyfe, J. C., Kharin, V. V., Santer, B. D., Cole, J. N. S. & Gillett, N. P. Significant impact of forcing uncertainty in a large ensemble of climate model simulations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2016549118 (2021).

Menary, M. B. et al. Aerosol-forced AMOC changes in CMIP6 historical simulations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, e2020GL088166 (2020).

Li, S., Liu, W., Allen, R. J., Shi, J.-R. & Li, L. Ocean heat uptake and interbasin redistribution driven by anthropogenic aerosols and greenhouse gases. Nat. Geosci. 16, 695–703 (2023).

Bushuk, M., Polvani, L. M. & England, M. R. Comparing the impacts of ozone-depleting substances and carbon dioxide on Arctic sea ice loss. Environ. Res. Clim. 2, 041001 (2023).

Sigmond, M. et al. Large contribution of ozone-depleting substances to global and Arctic warming in the late 20th century. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL100563 (2023).

Polvani, L. M., Previdi, M., England, M. R., Chiodo, G. & Smith, K. L. Substantial twentieth-century Arctic warming caused by ozone-depleting substances. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 130–133 (2020).

Roy, I. Solar cyclic variability can modulate winter Arctic climate. Sci. Rep. 8, 4864 (2018).

Hardacre, C. et al. Evaluation of SO_2, SO_4^2- and an updated SO_2 dry deposition parameterization in the United Kingdom Earth System Model. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 21, 18465–18497 (2021).

Mulcahy, J. P. et al. UKESM1.1: development and evaluation of an updated configuration of the UK Earth System Model. Geosci. Model Dev. 16, 1569–1600 (2023).

Flanner, M. G. et al. Springtime warming and reduced snow cover from carbonaceous particles. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 9, 2481–2497 (2009).

Hansen, J. & Nazarenko, L. Soot climate forcing via snow and ice albedos. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101, 423–428 (2004).

Dou, T.-F. & Xiao, C.-D. An overview of black carbon deposition and its radiative forcing over the Arctic. Adv. Clim. Chang. Res. 7, 115–122 (2016).

Simpson, I. R. et al. The CESM2 single-forcing large ensemble and comparison to CESM1: implications for experimental design. J. Clim. 36, 5687–5711 (2023).

Deng, J., Dai, A. & Xu, H. Nonlinear climate responses to increasing CO2 and anthropogenic aerosols simulated by CESM1. J. Clim. 33, 281–301 (2020).

Kay, J. E. et al. The Community Earth System Model (CESM) large ensemble project: a community resource for studying climate change in the presence of internal climate variability. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 96, 1333–1349 (2015).

Hurrell, J. W. et al. The Community Earth System Model: a framework for collaborative research. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 94, 1339–1360 (2013).

Ren, X., Liu, W., Allen, R. J. & Song, S.-Y. Distinct anthropogenic greenhouse gas and aerosol induced marine heatwaves. Environ. Res. Clim. 3, 015004 (2024).

Ren, X. & Liu, W. Distinct anthropogenic aerosol and greenhouse gas effects on El Niño/Southern Oscillation variability. Commun. Earth Environ. 6, 24 (2025).

Smith, C. J. & Forster, P. M. Suppressed late-20th century warming in CMIP6 models explained by forcing and feedbacks. Geophys Res Lett. 48, e2021GL094948 (2021).

Walsh, J. E., Chapman, W. L., Fetterer, F. & Stewart, J. S. Gridded monthly sea ice extent and concentration, 1850 onward. (G10010, Version 2). [Data Set]. Boulder, Colorado, USA. National Snow and Ice Data Center (2019).

Holland, M. M., Serreze, M. C. & Stroeve, J. The sea ice mass budget of the Arctic and its future change as simulated by coupled climate models. Clim. Dyn. 34, 185–200 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This study has been supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation (OCE-2123422, AGS-2053121, AGS-2237743, and AGS-2153486). The National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) is sponsored by the National Science Foundation under Cooperative Agreement 1852977.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.-C.L. performed the analysis and wrote the original draft of the paper. W.L. conceived the study. Y.-C.L., W.L., C.D., and M.H. contributed to interpreting the results and made improvements to the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, YC., Liu, W., Deser, C. et al. Distinct impacts of diverse forcing agents on Arctic sea ice since the mid-twentieth century. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 362 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01238-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01238-y