Abstract

Previous studies using an emergent constraint have suggested that climate models underestimate the winter jet stream response to sea ice loss, casting doubt on the quality of mid-latitude climate projections. However, the robustness of this emergent constraint has been questioned. Here, we propose a more robust emergent constraint based on lower stratospheric winds. Using coordinated sea ice loss experiments with bespoke versions of two state-of-the-art climate models along with a multi-model archive, we identify a strong relationship between these winds and the jet stream response. The new emergent constraint reduces the uncertainty in the response by 62% and indicates that the real-world response closely matches the multi-model mean—suggesting no systematic underestimation, in contrast to earlier studies. Our results underscore the importance of reducing lower stratospheric wind biases and increase confidence in climate model projections of a future poleward shift of the jet stream in response to global warming.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Regional variations in climate change are shaped by changes in the large-scale atmospheric circulation. The position and strength of the mid-latitude jet stream not only determine how surface temperature and precipitation patterns change on average1,2,3, but also impact extreme weather events through their impact on the location and intensity of the storm tracks4,5,6, atmospheric rivers7,8 and atmospheric blocks9, which drive heat, cold, wind and precipitation extremes10,11,12. Obtaining robust projections of the mid-latitude circulation response to climate change is therefore essential for effective efforts to adapt to the impacts of global warming.

It has become evident that the future strength and position of the jet streams are governed by changes in meridional (equator-to-pole) temperature gradients13. Arctic sea ice loss is accompanied by enhanced warming in the Arctic (often referred to as Arctic Amplification), reducing the equator-to-pole temperature gradient and generally contributing to an equatorward shift of the jet streams2,3,13,14,15,16,17,18. At the same time, enhanced upper tropospheric warming in the tropics, another notable consequence of global warming, increases the equator-to-pole temperature gradient and contributes to stronger, more poleward jet streams13,18,19. The competition between these two opposing drivers is often referred to as a ‘tug-of-war’. The relative strength of the two drivers determines the sign of the net response to global warming20,21,22,23,24,25. In the zonal-mean, climate models tend to project a small net poleward shift of the mid-latitude jet stream in response to global warming, especially for the higher emissions scenarios (ref. 26, Figure 4.30a), consistent with an emerging poleward shift in observations27 and suggesting that the impacts of the tropical upper-tropospheric warming will exceed that of Arctic Amplification. It should be noted though, that regionally, the response is more complicated than a simple shift, with the winter North Atlantic jet projected to narrow6,28,29, which could be the result of opposing shifts in different parts of the winter season30.

Recent studies have questioned the accuracy of these climate projections, and in particular the part of the response that is driven by Arctic sea ice loss. A previous study17 developed an emergent constraint, a relationship across models between an observable aspect of the climate system (the ‘predictor’) and its response to climate change (the ‘predictand’)31,32. Using a coordinated set of sea ice loss experiments33, they identified a positive correlation across models between the strength of the simulated eddy-feedback (a measure of how large scale atmospheric waves impact the zonal-mean flow) and the jet response to sea ice loss. Since the eddy-feedback was found to be 1.2 to 3 times too weak in the models compared to observation-based products, they suggested that the real-world jet response to sea ice loss is systematically underestimated by climate models. This finding is consistent with other evidence that climate models tend to underestimate the predictable fraction of North Atlantic Oscillation, which has been referred to as the ‘signal-to-noise paradox’34. Another recent paper18 proposed a method for correcting the systematic underestimation in response to sea ice loss, and found that after correction the (equatorward) jet shift in response to sea ice loss, exceeds the (poleward) jet shift in response to increasing greenhouse gases. Hence, they suggested that after the correction the net response of the jet to global warming would be an equatorward shift, in contrast to the raw (uncorrected) climate projections. This has potentially large implications as climate impact studies are based on climate models that project a zonal-mean poleward shift of the jet stream.

However, a recent study found that there are large uncertainties in the eddy-feedback parameter (EFP), the predictor used in these studies to constrain the response to sea ice loss35. They showed that after accounting for sampling and multidecadal variability, the diagnosed EFP in the current generation of climate models is generally not inconsistent with observation-based products. This challenges the notion that climate models systematically underestimate EFP and, through the EFP-based emergent constraint, the jet stream response to sea ice loss. It also highlights the need to explore whether a more robust emergent constraint with smaller uncertainty in the predictor can be identified.

The findings of ref. 3 (hereafter SS24) suggest a potential basis for such an alternative emergent constraint. Their study demonstrated with controlled perturbation experiments with the Canadian Earth System Model version 5 (CanESM5) that the magnitude of the jet stream response to sea ice loss critically depends on the present-day zonal wind climatology and proposed a mechanism to explain this sensitivity. In addition, ref. 36 provided evidence that the stratospheric response to sea ice loss is sensitive to the present-day climatology. These studies raise the question whether the differences in the present-day zonal wind climatology could explain the large differences in the response across models. In the current study, we first establish the robustness of the SS24 findings by repeating the perturbation experiments with a second, independent state-of-the-art Earth System Model. We will then combine these simulations with the large archive of coordinated sea ice loss experiments that contributed to the Polar Amplification Model Intercomparison Project (PAMIP)33, and show that across the 15 models, there is a robust relationship between the zonal wind climatology and the jet stream and surface climate response to future sea ice loss. Finally, we will exploit this relationship to reduce the uncertainty in the climate response to sea ice loss through an emergent constraint.

Results

Single model sensitivity experiments

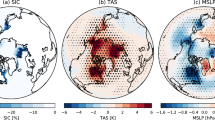

We begin by examining the robustness of the SS24 results by conducting experiments with a second model, the Community Earth System Model version 2 (CESM2; see Methods). Similar to the approach taken with CanESM5 in SS24, we conduct identical sea ice loss experiments using two versions of CESM2. These two versions are identical except for a parameter in the orographic gravity wave scheme37 (see Methods), which, as in the two versions of CanESM5, resulted in a modification of their present-day climatology: CESM2-G1 has strong climatological winds in the neck region (between the subtropical jet and polar vortex) and the polar vortex, akin to CanESM5, while CESM2-G2 has weaker winds in these regions, with a smaller bias compared to observations, similar to CanESM5-G (see contours in Fig. 1 and see Supplementary Fig. 1).

December-February (DJF) zonal-mean zonal wind (contours) present day climatology and (shading) response to future sea ice loss in a CESM2-G1, b CESM2-G2 and c their difference and d CanESM5, e CanESM5-G and f their difference. The contour interval is 10 m s-1 in a, b, d, e and 5 m s-1 in c and f, with dashed contours representing negative values and the thick line the 0 m s-1 contour. Black dots denote statistically significant responses at a more than 95% confidence level according to a Student’s t test.

In response to future Arctic sea ice loss, CESM2-G1, with its stronger present-day neck region winds, exhibits a pronounced stratospheric pathway38,39,40,41. This includes a weakening of the stratospheric polar vortex, leading to a significant equatorward shift of the jet in the troposphere (Fig. 1a). This winter-mean response closely resembles that of CanESM5 with strong neck region winds (Fig. 1d). The seasonal cycle of the CESM2-G1 response (Supplementary Fig. 2), shows that the stratospheric pathway occurs 1-2 months earlier than in CanESM5 (SS24, Fig. 4). Notably, altering the present-day zonal wind climatology in CESM2-G2 suppresses the stratospheric pathway and results in a much weaker tropospheric response, similar to CanESM5-G (compare Fig. 1b, e). This significantly alters the surface climate response (Supplementary Fig. 3), akin to findings for CanESM5 in SS24.

The mechanism behind this substantial modification of the response is similar to that reported for CanESM5 in SS24: as in CanESM5-G, the reduced neck region winds in CESM2-G2 result in a region with a negative refractive index (see orange contours in Supplementary Fig. 4, and in Fig. 5c,d of SS24), which acts as a barrier to planetary wave propagation out of the polar vortex region. An Eliassen-Palm flux budget analysis (Supplementary Fig. 4 and SS24, Fig. 5c,d) shows that these differences can explain differences in where anomalous planetary wave activity in response to sea ice changes is deposited and slows down the mean flow. This mechanism, described in more detail in SS24, explains why the basic state in CanESM5 and CESM2-G1 allows for a stratospheric pathway to occur, leading to a significant equatorward shift of the jet in the troposphere, and why the basic state in CanESM5-G and CESM2-G2 acts to suppress a stratospheric pathway, leading to a very small tropospheric response. In conclusion, these findings validate the SS24 conclusions using an independent model and demonstrate that in controlled single-model experiments, perturbing the climatological neck region winds leads to a markedly different response to sea ice loss.

PAMIP multi-model analysis

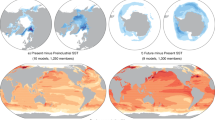

We next examine if these relationships between present-day neck region winds and the response to sea ice loss across two versions of the same model are also valid across the spread between multiple (independent) models, by considering the PAMIP multi-model archive. We supplement these 12-model PAMIP simulations with the corresponding experiments from CanESM5-G, CESM2-G1 and CESM2-G2, for a total of 15 models, but note that very similar results are obtained when we limit the analysis to the 12 models from the PAMIP archive. Figure 2a shows that the multi-model mean response features a slight weakening of the stratospheric polar vortex and equatorward shift of the tropospheric jet stream17. While the tropospheric jet consistently shifts equatorward in the models, previous studies17,18 showed that despite identical lower boundary forcings (i.e., prescribed sea surface temperature and sea ice), the magnitude of the tropospheric zonal wind response varies significantly – by up to a factor of four (see also Fig. 4). Furthermore, the sign of the stratospheric response is not consistent across models.

(colors) December-February (DJF) response to sea ice loss: a the multi-model mean, b the multi-model spread, as quantified by the difference between the three models with the strongest and the three models with the weakest tropospheric wind response, c the across-model correlation with the present-day neck region winds (uneck,pd), d the mean of the three models with the strongest uneck,pd, e the mean of the three models with the weakest uneck,pd, and f its difference. Contours in a show the present-day multi-model mean zonal-wind (contour interval: 10 m s-1), and in c and f the multi-model mean response (identical to the shading in a, contour interval: 0.2 m s-1). Black dots in c denote statistically significant correlations at a more than 95% confidence level. The black box in a (between 40 and 60°N and between 100 and 50 hPa) marks the region of the neck region winds, and the black boxes in b (between 600 and 150 hPa, and between 30 and 39°N for the low latitude and between 54 and 63°N for the high latitude box) mark the regions over which the tropospheric zonal wind response is calculated.

This substantial model spread is highlighted in Fig. 2b, which shows the difference in the zonal-mean zonal wind response between the three models with the strongest tropospheric zonal wind response (following ref. 17 defined as the response of the zonal wind averaged over the high minus low latitude box in Fig. 2b) and the three with the weakest response. Notably, the magnitude of this response difference exceeds that of the multi-model mean response (Fig. 2a), reflecting the fact that some models exhibit very weak responses, while others show responses that are two to three times larger than the multi-model mean response. The question we explore next is whether this large spread in the response can be explained by the spread in the present-day neck region winds.

To investigate this, we present correlations between the strength of the present-day neck region winds (defined here as the climatological zonal-mean zonal wind averaged over the box in Fig. 2a and hereafter referred to as uneck,pd) and the zonal-mean zonal wind response to sea ice loss at each latitude and pressure level. The CanESM5 and CESM2 simulations in which the present-day climatology was perturbed (Fig. 1) predict that in response to sea ice loss models with a stronger uneck,pd would tend to exhibit a stronger weakening of the stratospheric polar vortex and a stronger equatorward shift of the tropospheric jet stream. This is confirmed by the correlation analysis shown in Fig. 2c, which reveals negative correlations between uneck,pd and the stratospheric polar vortex response to sea ice loss, and a dipole of positive and negative correlations between uneck,pd and the tropospheric zonal-mean zonal wind response around 40°N and around 65°N, respectively. An important finding of this study is that across PAMIP models, the strength of uneck,pd is a good predictor of the atmospheric circulation response to sea ice loss, as hypothesized by SS24. This conclusion is further reinforced by composites of the zonal-mean zonal wind response, which reveal a strong response in the three models with the strongest uneck,pd (Fig. 2d) and a much weaker response in the three models with the weakest uneck,pd (Fig. 2e). The difference between these composites closely resembles the PAMIP model spread (compare Fig. 2f, b).

We now extend the correlation and composite analysis to other aspects of the climate response to sea ice loss. Figure 3a shows the multi-model mean lower tropospheric zonal wind response. The equatorward jet shift appears to be primarily confined to the North Atlantic. While a similar dipole in zonal wind response is found over the Pacific, a comparison with the present-day climatology (indicated by the contours) shows that, rather than a jet shift, the response is characterized by an eastward extension of the Pacific jet toward North America42. Both the correlation analysis (Fig. 3b) and composite analysis (Fig. 3c) show that the magnitude of both the Atlantic jet shift (and in particular the part that extends to Europe) and the eastward extension of the Pacific jet toward North America depends on uneck,pd. This, in turn, influences the mid-latitude surface temperature response to sea ice loss, which in the multi-model mean is characterized by warming (Fig. 3d). Figures 3e and f show that in models with a stronger uneck,pd the magnitude of the warming is stronger over western North America–driven by a larger eastward extension of the Pacific jet, which transports relatively mild ocean air inland. Similarly, the stronger Atlantic jet shift in models with a strong uneck,pd causes increased warming over Greenland and decreased warming over northern Eurasia.

DJF a–c Zonal wind at 850 hPa and d–f surface temperature response to future sea ice loss: a, d multi-model mean, b, e the across-model correlation with the uneck,pd and c,f the difference between the three models with the strongest and the three models with the weakest uneck,pd. The grey contour in a indicates the 9 m s-1 contour of the multi-model mean present-day zonal wind at 850 hPa and the dots in b and e denote statistically significant correlations at a more than 95% confidence level.

Emergent Constraint

Having established strong statistical relationships between uneck,pd and various aspects of the climate response to sea ice loss, we next attempt to exploit these relationships to reduce the uncertainty in the response through a neck region wind-based emergent constraint. Such emergent constraints are presented for the sea ice loss-induced response of the stratospheric polar vortex (Fig. 4a, defined here as the zonal-mean zonal wind at 10 hPa averaged between 60 and 75°N as in ref. 43), the tropospheric zonal wind (Fig. 4b) and the near surface jet latitude (Fig. 4c, calculated here at 850 hPa following the calculation in ref. 16). Consistent with Figs. 2c, 3b, and 4 shows that these three metrics of the response all significantly correlate with uneck,pd, with a correlation coefficient of -0.71 (p < 0.01) for the stratospheric polar vortex, and -0.53 (p = 0.02) for the tropospheric zonal wind and near-surface jet latitude responses. The emergent constraint response is the value of the linear fit evaluated at the observed value of the present-day neck region winds. Importantly, since the observed value of the present-day region winds is virtually identical to the multi-model mean value, the constrained responses (depicted by the big green dots in Fig. 4) are virtually identical to the multi-model mean responses (depicted by the big red dots in Fig. 4). Hence, the key finding of this study is that the emergent constraint based on present-day neck region winds suggests that on average, climate models accurately simulate the response to sea ice loss.

Relationship across models between the DJF present-day neck region winds (uneck,pd), and the DJF response to future sea ice loss of a the stratospheric polar vortex, b the tropospheric zonal wind and c the 850hPa jet latitude. The small red dots and pink error bars represent model values and their corresponding 5-95% confidence interval. The black line is the linear fit (with the correlation coefficient r and its p-value shown on the bottom left), the dark shading the corresponding 5–95% confidence interval and the light gray shading the 5–95% confidence interval accounting for the uncertainty in model values. The big red dot and error bar show the (unconstrained) multi-model mean and 5-95% uncertainty. The vertical green line and shading show the observed value and 5–95% confidence interval. The big green dot and error bar show the emergent constrained value and the corresponding 5–95% uncertainty. See main text and Methods for details.

Finally, we assess the strength of the emergent constraint by comparing the uncertainty in the unconstrained and constrained responses. For the unconstrained model response, uncertainty is quantified by bootstrapping ensemble-mean responses, generating 10,000 resamples per model to derive 5–95% confidence intervals (shown by the small pink error bars in Fig. 4). The overall uncertainty is defined by the envelope of these intervals across all models (large pink error bars in Fig. 4; see Methods). For example, the unconstrained stratospheric polar vortex response has a 5–95% confidence interval of –3.1 m/s to +2.0 m/s, corresponding to a total uncertainty of 5.1 m/s. The uncertainty in the constrained model response arises from three sources: (i) the linear regression between predictor and predictand, (ii) the internal variability of ensemble-mean model values, and (iii) the uncertainty in the observed wind used to apply the constraint32. These three contributions are combined to produce the overall 5–95% confidence interval for the emergent constraint response (large green error bar in Fig. 4, see Methods). For the stratospheric polar vortex, this interval is –1.4 m/s to +0.5 m/s, giving a total uncertainty of 1.9 m/s—63% smaller than in the unconstrained case. This demonstrates the strength of the neck-region-wind-based emergent constraint in reducing uncertainty in the response to sea ice loss. Very similar reductions are found for the tropospheric zonal wind and the near-surface jet latitude response (62%).

Discussion

In summary, our controlled single-model experiments and analysis across climate models have revealed that the strength of the present-day neck region winds is a good predictor of the atmospheric circulation response to sea ice loss. Leveraging this relationship we have proposed a new, robust emergent constraint, which reduces the uncertainty in the jet stream response by 62% and indicates that the multi-model mean response is close to the real-world response. This reduction in uncertainty is attributed not only to the strong linear relationship between predictor and predictand but also to the relatively low uncertainty in the predictor—the strength of the neck region winds. This is a notable advantage of the newly proposed emergent constraint over a previously proposed one, for which the predictor’s amplitude was highly uncertain17,35. Future research should examine if our emergent constraint survives an out-of-sample test, which is a requirement for a proposed emergent constraint to be verified31,32. This would require identical sea ice loss experiments to be performed with a new generation of climate models.

These results have important implications for model developers, as they demonstrate that an accurate simulation of neck region winds is crucial for accurately simulating the response to future sea ice loss. The importance of accurate neck region winds has also been identified regarding the climate response to CO2 doubling19 and the stratospheric polar vortex response to climate change43. How can this be accomplished? In our CanESM5 and CESM2 perturbation experiments, the present-day neck region winds were perturbed by changing parameters in the orographic gravity wave drag (OGWD) scheme. To investigate the impact of OGWD on neck region winds across models we turn to historical experiments in the CMIP6 archive (see Methods). The multi-model mean OGWD is characterized by large OGWD just above the subtropical jet extending poleward and upward (Fig. 5a). The pattern of the composite difference in OGWD between models with weak and strong neck region winds (Fig. 5b) is very similar to that of the multi-model mean climatology. This suggests that the OGWD patterns is similar in all models, but that the amplitude, which in OGWD schemes is determined by a scaling parameter37,44, determines the strength of the neck region winds. In conclusion, these results highlight the importance of proper tuning of the OGWD scheme for accurate climate projections.

DJF climatology of the zonal wind tendency due to orographic gravity waves (OGWD): a multi-model mean and b the difference between the three models with the weakest and the three models with the strongest uneck,pd. Based on 1950–2014 climatologies of historical runs from 12 CMIP6 models (see Methods for details). The contours in b represent the multi-model mean (repeated from a).

Our results also have important implications for future climate projections. While a previous study has suggested that a correction for a systematic underestimation of the impact of sea ice loss on the atmospheric circulation results in a response that is opposite to the raw model projections18, our new, more robust emergent constraint suggests that such a correction is not needed. Hence, our results enhance the confidence in the climate model projections that the tropics will win the ‘tug-of-war’ and that the zonal-mean jet stream will shift poleward in response to future warming.

Methods

Models

CanESM5 is a state-of-the-art Earth system model developed at the Canadian Centre for Climate Modelling and Analysis (CCCma)45. Its atmospheric component is run at T63 spectral resolution, corresponding to approximately 2.8o in both latitude and longitude, and employs 49 vertical levels with a model lid near 1 hPa. Although CanESM5 is classified as a “low-top” model with a lower frequency of sudden stratospheric warmings than observed46,47, it has been shown to be among the best-performing models in reproducing stratosphere–troposphere coupling48.

CESM2 is the latest Earth system model developed by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR)49. Its atmospheric component, the Community Atmosphere Model version 6 (CAM6), employs the finite volume (FV) dynamical core. The CESM2 sensitivity experiments are conducted at a horizontal resolution of 2.5° in longitude and 1.92° in latitude, in contrast to the default 1.25° × 0.94° grid used in the regular CESM2 model simulations submitted to PAMIP50. The model top is located at 2.26 hPa, classifying it as a “low-top” model. CESM2 ranks among the top 10% of CMIP6 models in representing key aspects of tropospheric circulation51.

Perturbation of climatological winds

Both CanESM5 and CESM2 use an anisotropic orographic gravity wave drag scheme37, which allows for parameter adjustments to perturb the climatological winds. In CanESM5, two free parameters are modified to enhance the gravity wave drag, producing a variant called “CanESM5-G”47. The increased gravity wave drag in CanESM5-G results in a weaker stratospheric polar vortex and reduced neck winds compared to the default CanESM5. Unlike many other low-top models, CanESM5-G slightly overestimates the frequency of sudden stratospheric warmings47. Two CESM2 variants with similar zonal wind climatologies as CanESM5 and CanESM5-G are obtained by applying similar adjustments. In particular, the gravity wave drag efficiency parameter named “effgw_rdg_beta” is reduced from the default value of 1.0 to 0.4 to obtain a zonal wind climatology with relatively strong neck region winds in CESM2-G1, while CESM2-G2 features weaker neck regions winds through the increase of this parameter to 2.5.

Model Simulations

For each model configuration, we follow the PAMIP protocol to conduct two experiments: pdSST-pdSIC and pdSST-futArcSIC, representing the present-day sea-surface temperature combined with either observed or future Arctic sea ice conditions, respectively33. The radiative forcing is fixed at year-2000 levels. Each simulation is run from April 1, 2000, to May 31, 2001. For CanESM5 and CanESM5-G, 300 ensemble members are generated using 10 distinct initial states, each with 30 perturbations to cloud physics introduced by varying the seed in the random number generator. A similar approach is used for CESM2, except that the number of initial states is doubled, resulting in 600 ensemble members. The CanESM5 and CanESM5-G simulations are described in detail in SS24.

Multi-model CMIP6 PAMIP simulations

We consider all PAMIP models available at the Earth System Grid Federation (ESGF) system with at least 100 ensemble members, where ensemble members are selected only if all considered variables (zonal wind, temperature, surface temperature and sea level pressure) for both pdSST-pdSIC and pdSST-futArcSIC experiments are available. These 12 models are AWI-CM-1-1-MR (100), CanESM5 (300), CESM1-WACCM-SC (299), CESM2 (200), CNRM-CM6-1 (499), E3SM-1-0 (200), EC-Earth3 (169), FGOALS-f3-L (100), HadGEM3-GC31-MM (300), IPSL-CM6A-LR (200), MIROC6 (100), NorESM2-LM (200), with the number in brackets denoting the number of available ensemble members. We supplement these simulations with CanESM5-G (300), CESM2-G1 (600) and CESM2-G2 (600), for a total of 15 models.

CMIP6 historical simulations

To investigate the importance of orographic gravity wave drag for present-day neck region winds, we consider all CMIP6 models available at the ESGF system with at least one ensemble member of the historical simulation for which both the zonal wind and the zonal wind tendency due to orographic gravity wave drag (utendogw) is available. These 12 models are: CanESM5 (r1i1p2f1), CESM2 (r1i1p1f1), CESM2-FV2 (r1i1p1f1), CESM2-WACCM (r1i1p1f1), CESM2-WACCM-FV2 (r1i1p1f1), GFDL-ESM4 (r1i1p1f1), HadGEM3-GC31-LL (r1i1p1f3), HadGEM3-GC31-MM (r1i1p1f3), IPSL-CM6A-LR (r1i1p1f1), MPI-ESM1-2-LR (r11i1p1f1), MRI-ESM2-0 (r1i1p1f1) and UKESM1-0-LL (r1i1p1f2), with the label in the brackets denoting the ensemble member selected for this study. Note that we did not consider the PAMIP simulations (pdSST-pdSIC) for this analysis as only a few PAMIP models provided utendogw data.

Observed value of the neck regions winds, and its uncertainty

The observed present-day (1981-2014) neck region wind is the average of three reanalysis products: ERA552, MERRA-253 and JRA-5554. To quantify uncertainty, we apply bootstrapping: the 1981–2014 data from all three products are pooled, 34 years are randomly resampled with replacement, and the mean wind is calculated. This procedure is repeated 10,000 times to derive the 5–95% confidence interval.

Uncertainty in the unconstrained model response

For each model, bootstrapping was used to quantify uncertainty due to internal variability in (i) the ensemble-mean neck regions winds (the predictor) and (ii) the ensemble-mean response to future sea ice loss (the predictand). Specifically, for each variable 10,000 resampled ensemble means were generated to form a bootstrap distribution, from which 5–95% confidence intervals were calculated (shown as pink error bars in Fig. 4). The total uncertainty in the unconstrained model response is defined as the full range of these error bars across all models: the lower bound corresponds to the minimum of the model-specific 5% confidence levels, and the upper bound corresponds to the maximum of the model-specific 95% confidence levels.

Uncertainty in the emergent constraint model response

The uncertainty in the emergent constraint arises from three sources: (1) uncertainty in the predictor–predictand relationship (i.e., the regression fit), (2) uncertainty in the ensemble-mean model values due to internal variability, and (3) uncertainty in the observational value used to apply the constraint. These are treated as follows.

First, we calculate the uncertainty in the regression fit using the 5–95% confidence interval based on the raw (non-bootstrapped) ensemble mean model values, using the Python routine scipy.stats.linregress, which estimates uncertainty intervals from an ordinary least squares regression under the assumption of normally distributed residuals. This interval is shown as the dark gray shading in Fig. 4.

Next, we combine this regression uncertainty with the uncertainty in the model ensemble means by repeating the regression analysis 10,000 times, each time drawing model ensemble means from their bootstrap distributions. This yields bootstrap distributions of the lower (5%) and upper (95%) regression confidence limits. The overall 5–95% confidence interval is then defined by the 5th percentile of the lower-limit distribution and the 95th percentile of the upper-limit distribution and is shown by light gray shading in Fig. 4.

Finally, we incorporate the uncertainty in the observed value by evaluating the emergent constraint not only at the best-estimate observed wind value, but also at its 5% and 95% confidence levels. The intersections of the light grey shading (representing the model uncertainty) with the green shading (representing the observational range) define the range of uncertainty in the emergent constraint response. Specifically, the 5% and 95% observational values are applied to the upper and lower regression confidence limits obtained in the previous step, producing a range of constrained responses. The overall 5% confidence level of the emergent constraint response is taken as the lowest of these values, and 95% confidence level as the highest.

Data availability

PAMIP simulations from CanESM5-G, CESM2-G1 and CESM2-G2 are available at https://crd-data-donnees-rdc.ec.gc.ca/CCCMA/publications/2025_Sigmond_Sun, and CMIP6 PAMIP and historical simulations are available from the Earth System Grid Federation portal at https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/. Observations of zonal-mean zonal wind were obtained from https://www.jamstec.go.jp/ridinfo/.

Code availability

Analysis scripts used for this study are available at https://gitlab.com/michael.sigmond/pamip_cmip6.

References

McKenna, C. M. & Maycock, A. C. The Role of the North Atlantic Oscillation for Projections of Winter Mean Precipitation in Europe. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL099083 (2022).

Ye, K., Woollings, T. & Screen, J. A. European Winter Climate Response to Projected Arctic Sea-Ice Loss Strongly Shaped by Change in the North Atlantic Jet. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2022GL102005 (2023).

Sigmond, M. & Sun, L. The role of the basic state in the climate response to future Arctic sea ice loss. Environ. Res.: Clim. 3, 031002 (2024).

Harvey, B. J., Shaffrey, L. C. & Woollings, T. J. Equator-to-pole temperature differences and the extra-tropical storm track responses of the CMIP5 climate models. Clim. Dyn. 43, 1171–1182 (2014).

Shaw, T. A. et al. Storm track processes and the opposing influences of climate change. Nat. Geosci. 9, 656–664 (2016).

Harvey, B. J., Cook, P., Shaffrey, L. C. & Schiemann, R. The Response of the Northern Hemisphere Storm Tracks and Jet Streams to Climate Change in the CMIP3, CMIP5, and CMIP6 Climate Models. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 125, 1–10 (2020).

Payne, A. E. et al. Responses and impacts of atmospheric rivers to climate change. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 143–157 (2020).

Zhang, L., Zhao, Y., Cheng, T. F. & Lu, M. Future changes in global atmospheric rivers projected by CMIP6 Models. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 129, e2023JD039359 (2024).

Woollings, T. et al. Blocking and its Response to Climate Change. Curr. Clim. Change Rep. 4, 287–300 (2018).

Screen, J. A. & Simmonds, I. Amplified mid-latitude planetary waves favour particular regional weather extremes. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 704–709 (2014).

Pfahl, S. & Wernli, H. Quantifying the relevance of atmospheric blocking for co-located temperature extremes in the Northern Hemisphere on (sub-)daily time scales. Geophysical Research Letters 39, (2012).

Waliser, D. & Guan, B. Extreme winds and precipitation during landfall of atmospheric rivers. Nat. Geosci. 10, 179–183 (2017).

Butler, A. H., Thompson, D. W. J. & Heikes, R. The Steady-State Atmospheric Circulation Response to Climate Change–like Thermal Forcings in a Simple General Circulation Model. https://doi.org/10.1175/2010JCLI3228.1 (2010).

Ye, K., Woollings, T., Sparrow, S. N., Watson, P. A. G. & Screen, J. A. Response of winter climate and extreme weather to projected Arctic sea-ice loss in very large-ensemble climate model simulations. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 1–16 (2024).

Screen, J. A., Deser, C., Smith, D. M. & Zhang, X. Consistency and discrepancy in the atmospheric response to Arctic sea ice loss across climate models. Nature Geoscience 1–29 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-018-0059-y (2018).

Zappa, G., Pithan, F. & Shepherd, T. G. Multimodel Evidence for an Atmospheric Circulation Response to Arctic Sea Ice Loss in the CMIP5 Future Projections. Geophys. Res. Lett. 45, 1011–1019 (2018).

Smith, D. M. et al. Robust but weak winter atmospheric circulation response to future Arctic sea ice loss. Nat. Commun. 13, 727 (2022).

Screen, J. A., Eade, R., Smith, D. M., Thomson, S. & Yu, H. Net equatorward shift of the jet streams when the contribution from sea-ice loss is constrained by observed eddy feedback. Geophys. Res. Lett. 49, e2022GL100523 (2022).

Sigmond, M. & Scinocca, J. F. The Influence of the Basic State on the Northern Hemisphere Circulation Response to Climate Change. J. Clim. 23, 1434–1446 (2010).

Deser, C. & Tomas, R. a. & Sun, L. The role of ocean-atmosphere coupling in the zonal mean atmospheric response to Arctic sea ice loss. J. Clim. 3, 141231092609003 (2014).

Blackport, R. & Kushner, P. J. Isolating the atmospheric circulation response to arctic sea ice loss in the coupled climate system. J. Clim. 30, 2163–2185 (2017).

Oudar, T. et al. Respective roles of direct GHG radiative forcing and induced Arctic sea ice loss on the Northern Hemisphere atmospheric circulation. Clim. Dyn. 0, 1–21 (2017).

Zappa, G. & Shepherd, T. G. Storylines of atmospheric circulation change for European regional climate impact assessment. J. Clim. 30, 6561–6577 (2017).

Hay, S. et al. Separating the Influences of Low-Latitude Warming and Sea Ice Loss on Northern Hemisphere Climate Change. J. Clim. 35, 2327–2349 (2022).

Yu, H., Screen, J. A., Xu, M., Hay, S. & Catto, J. L. Comparing the Atmospheric Responses to Reduced Arctic Sea Ice, a Warmer Ocean, and Increased CO2 and Their Contributions to Projected Change at 2°C Global Warming. J. Clim. 37, 6367–6380 (2024).

Lee, J.-Y. et al. Future Global Climate: Scenario-Based Projections and Near-Term Information. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 553–672 https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009157896.006 (2021).

Woollings, T., Drouard, M., O’Reilly, C. H., Sexton, D. M. H. & McSweeney, C. Trends in the atmospheric jet streams are emerging in observations and could be linked to tropical warming. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 1–8 (2023).

Peings, Y., Cattiaux, J., Vavrus, S. J. & Magnusdottir, G. Projected squeezing of the wintertime North-Atlantic jet. Environ. Res. Lett. 13, 074016 (2018).

Oudar, T., Cattiaux, J. & Douville, H. Drivers of the Northern Extratropical Eddy-Driven Jet Change in CMIP5 and CMIP6 Models. Geophys. Res. Lett. 47, 1–9 (2020).

García-Burgos, M., Ayarzagüena, B., Barriopedro, D., Woollings, T. & García-Herrera, R. Intraseasonal shift in the wintertime North Atlantic jet structure projected by CMIP6 models. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 1–11 (2024).

Hall, A., Cox, P., Huntingford, C. & Klein, S. Progressing emergent constraints on future climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 269–278 (2019).

Simpson, I. R. et al. Emergent constraints on the large scale atmospheric circulation and regional hydroclimate: do they still work in CMIP6 and how much can they actually constrain the future? J. Clim. 1–62 https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-21-0055.1 (2021).

Smith, D. M. et al. The Polar Amplification Model Intercomparison Project (PAMIP) contribution to CMIP6: investigating the causes and consequences of polar amplification. Geoscientific Model Dev. 12, 1139–1164 (2019).

Scaife, A. A. & Smith, D. A signal-to-noise paradox in climate science. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 1, 28 (2018).

Saffin, L., McKenna, C. M., Bonnet, R. & Maycock, A. C. Large Uncertainties When Diagnosing the “Eddy Feedback Parameter” and Its Role in the Signal-To-Noise Paradox. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL108861 (2024).

Mudhar, R. et al. Exploring mechanisms for model-dependency of the stratospheric response to Arctic warming. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmosph. 129, e2023JD040416 (2024).

Scinocca, J. F. & McFarlane, N. A. The parametrization of drag induced by stratified flow over anisotropic orography. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 126, 2353–2393 (2000).

Sun, L., Deser, C. & Tomas, R. A. Mechanisms of stratospheric and tropospheric circulation response to projected Arctic sea ice loss. J. Clim. 28, 7824–7845 (2015).

Wu, Y. & Smith, K. L. Response of Northern Hemisphere Midlatitude Circulation to Arctic Amplification in a Simple Atmospheric General Circulation Model. J. Clim. 29, 2041–2058 (2016).

Nakamura, T. et al. The stratospheric pathway for Arctic impacts on midlatitude climate. Geophys. Res. Lett. 43, 3494–3501 (2016).

Xu, M. et al. Important role of stratosphere-troposphere coupling in the Arctic mid-to-upper tropospheric warming in response to sea-ice loss. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 6, 9 (2023).

Ronalds, B., Barnes, E. A., Eade, R., Peings, Y. & Sigmond, M. North Pacific zonal wind response to sea ice loss in the Polar Amplification Model Intercomparison Project and its downstream implications. Clim. Dyn. 55, 1779–1792 (2020).

Karpechko, A. Y. U. et al. Northern hemisphere stratosphere-troposphere circulation change in CMIP6 Models: 2. Mechanisms and Sources of the Spread. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 129, e2024JD040823 (2024).

Hájková, D. & Šácha, P. Parameterized orographic gravity wave drag and dynamical effects in CMIP6 models. Clim. Dyn. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-023-07021-0 (2023).

Swart, N. C. et al. The Canadian Earth System Model version 5 (CanESM5.0.3). Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 4823–4873 (2019).

Hall, R. J., Mitchell, D. M., Seviour, W. J. M. & Wright, C. J. Persistent Model Biases in the CMIP6 representation of stratospheric polar vortex variability. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmospheres 126, e2021JD034759 (2021).

Sigmond, M. et al. Improvements in the Canadian Earth System Model (CanESM) through systematic model analysis: CanESM5.0 and CanESM5.1. Geosci. Model Dev. 16, 6553–6591 (2023).

Butler, A. H., Karpechko, A., Yu & Garfinkel, C. I. Amplified decadal variability of extratropical surface temperatures by stratosphere-troposphere coupling. Geophys. Res. Lett. 50, e2023GL104607 (2023).

Danabasoglu, G. et al. The Community Earth System Model Version 2 (CESM2). J. Adv. Modeling Earth Syst. 12, e2019MS001916 (2020).

Sun, L., Deser, C., Simpson, I. & Sigmond, M. Uncertainty in the winter tropospheric response to arctic sea ice loss: the role of stratospheric polar vortex internal variability. J. Clim. 35, 3109–3130 (2022).

Simpson, I. R. et al. An evaluation of the large-scale atmospheric circulation and its variability in CESM2 and Other CMIP Models. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 125, (2020).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Gelaro, R. et al. The Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for Research and Applications, Version 2 (MERRA-2). https://doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-16-0758.1 (2017).

Kobayashi, S. et al. The JRA-55 reanalysis: general specifications and basic characteristics. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. 93, 5–48 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank Russell Blackport for helpful feedback on an earlier draft. L.S. was supported by NSF AGS-2300038.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.S. conceived the ideas, performed the CanESM5-G simulations, performed the analysis and wrote the manuscript. L.S. performed the CESM2-G1 and CESM2-G2 simulations, contributed to analysis and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sigmond, M., Sun, L. Jet stream response to future Arctic sea ice loss not underestimated by climate models. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 383 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01262-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01262-y

This article is cited by

-

Causes and consequences of Arctic amplification elucidated by coordinated multimodel experiments

Communications Earth & Environment (2025)