Abstract

Arctic amplification weakens the meridional temperature gradient (∂T/∂y), reducing the Northern Hemisphere winter daily temperature variability (Tstd). However, the extent to which Tstd recovers following CO₂ removal remains uncertain. We investigate the hysteresis and reversibility of Tstd under various CO₂ pathways using UKESM1-0-LL. The mid-latitude Tstd reduced during the ramp-up phase partially recovers following CO₂ removal, but its magnitude depends on the region and peak CO₂ concentration. In the low-concentration experiments, Tstd nearly returns to pre-industrial levels, whereas the high-concentration experiments show hysteresis and irreversibility in eastern Canada and northwestern Eurasia. These regional differences are primarily driven by changes in local temperature gradients. Specifically, the dominant factor for eastern Canada is the meridional temperature gradient, whereas for northwestern Eurasia, it is the zonal temperature gradient related to the land-sea thermal contrast. These results suggest that the response of Tstd to CO2 removal differs depending on the region and the peak concentration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Global warming has profoundly affected both human societies and ecosystems over the past several decades, primarily because of rising atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations, particularly carbon dioxide (CO₂)1. Arctic Amplification (AA) refers to a phenomenon in which the Arctic region warms at a much faster rate than the global average. This disproportionate warming results from the interplay of multiple feedback mechanisms, including sea ice-albedo feedback, increased ocean-atmosphere heat exchange, and enhanced longwave radiation due to stable atmospheric stratification2,3,4.

As Arctic sea ice retreats, the exposed dark ocean surface absorbs more solar radiation, accelerating warming through the well-known ice-albedo feedback2. During the cold season, the absence of insulating sea ice allows more heat to escape from the ocean to the atmosphere, enhancing near-surface temperature increases3. Moreover, the Arctic atmosphere’s strong surface-based temperature inversions trap heat efficiently, amplifying surface warming4. In addition, the intensified poleward heat and moisture transport under greenhouse forcing further contribute to the Arctic’s amplified response3. These mechanisms collectively lead to substantial weakening of the meridional temperature gradient (∂T/∂y, hereafter dT/dy for convenience), with critical implications for mid-latitude climate dynamics5,6,7,8,9,10,11.

Recent studies have increasingly recognized that Arctic climate variability, particularly sea ice and atmospheric circulation, can influence tropical climate systems through large-scale teleconnections. For example, the springtime Arctic Oscillation (AO) has been shown to influence subsequent El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) events by triggering westerly wind bursts over the equatorial Pacific12. Arctic sea ice anomalies in the Greenland–Barents Seas during the boreal winter can also affect the following winter ENSO through changes in air–sea coupling13. Moreover, winter sea ice conditions in the Barents–Greenland Seas have been found to serve as a precursor to Indian Ocean Dipole events in the following autumn, indicating a broader role of Arctic processes in shaping tropical ocean–atmosphere variability14.

Winter daily temperature variability in the mid-latitudes is closely linked to extreme weather events such as cold waves, severe cold air outbreaks, and abrupt temperature fluctuations. These variations affect various sectors, including energy consumption15, agricultural productivity16, and socioeconomic stability17. Recent high-impact extreme events18,19,20,21,22 suggest that temperature variability plays a crucial role beyond the simple trend of mean temperature changes. Some studies have proposed that a reduction in dT/dy due to AA could weaken westerly winds and lead to greater waviness in atmospheric circulation, potentially increasing extreme weather patterns in mid-latitudes23,24. However, observational studies3,25,26,27 and climate model simulations6,7,10,11,28,29 have indicated that a decrease in dT/dy generally suppresses daily temperature variability in winter. This indicates that the future winter climate will become less variable and extreme30.

Recent advancements in greenhouse gas mitigation and removal technologies have further intensified interest in conducting CO₂ removal climate simulations and assessing their impacts31,32. These experiments extend beyond simple analyses of warming pathways to address whether the climate system can return to its initial state after a period of high CO₂ forcing or irreversible changes occur33,34,35,36,37.

Under conditions where AA reduces mid-latitude winter temperature variability, it remains unclear whether CO₂ removal will restore the temperature variability to its previous state or cause irreversible changes. Existing studies have mainly focused on how increasing CO₂ levels and AA contribute to temperature variability, but there is a lack of studies investigating whether this variability recovers when CO₂ levels decline.

Moreover, recent studies have suggested that AA persists even when the CO₂ concentration decreases38,39,40, which could further complicate the recovery of temperature variability. Previous research41 demonstrated that AA could be even more pronounced during CO₂ reduction through climate model experiments across a wide range of CO₂ scenarios (from 1/8×CO₂ to 8×CO₂). This persistence of AA implies that winter daily temperature variability may not fully revert to its initial state during CO₂ ramp-down.

Daily temperature variability can be decomposed into contributions from the mean state and eddy components (see Methods). Among these, dT/dy plays a key role in shaping the mean state component and is strongly modulated by AA. Indeed, Previous research8 showed that changes in this gradient alone can explain more than half of the daily temperature variability in winter. This underscores the importance of understanding how large-scale thermodynamic structures respond to and recover from CO2 forcing.

This study analyzes the evolution and recovery of daily temperature variability under increasing and removing CO₂ concentrations to assess whether hysteresis effects emerge. Additionally, we evaluate the influence of the peak CO₂ concentration and CO₂ removal rates on the recovery of temperature variability. If complete recovery is not observed, we investigate the regional factors contributing to irreversibility. Our analysis focuses on the Northern Hemisphere winter (December–February, DJF), when AA is evident. The results of this study contribute to the assessment of the impact of CO₂ removal policies on winter temperature variability.

Results

This study investigates how DJF daily temperature variability (Tstd) responds to changes in atmospheric CO₂ concentrations using a series of ramp-up and ramp-down experiments with the UKESM1-0-LL model. The baseline High 1% (H1%) experiment involves a 1% annual increase in CO₂ from pre-industrial levels (287.16 ppm) for 140 years, followed by a symmetric 1% annual decrease over another 140 years, and a 150-year stabilization period. To assess more realistic CO₂ mitigation pathways, we additionally conduct Middle 1% (M1%) and Low 1% (L1%) experiments based on the two SSP scenarios (see Methods). In each experiment, CO₂ removal begins when the concentrations in the H1% experiment reach approximately 473.801 ppm (L1%) and 571.015 ppm (M1%).

To examine the sensitivity to the CO₂ removal rate, we perform additional simulations in which the ramp-down rate is doubled (H2%, M2%, and L2%). However, M2% and L2% cases show minimal deviation from their 1% counterparts and are excluded from further analysis. The CO₂ trajectories for all analyzed experiments are shown in Fig. 1 (see Fig. S1 for individual profiles).

Changes in Tstd and its relationship with AA

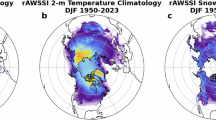

We assess the spatiotemporal evolution of Tstd by analyzing the zonal mean Tstd and DJF mean temperatures under various CO2 pathways (Fig. 2a–d; see Fig. S2a for the results over the entire integration period). Tstd is defined as the seasonal mean of the monthly standard deviations of the daily temperature anomalies (see Methods).

Changes in the mean winter temperature (contours) and Tstd (shading) relative to the mean of the piControl (CTL) run for (a) L1%, b M1%, c H1%, and d H2% experiments (Unit: K). The horizontal lines for each experiment indicate the time of peak CO2 concentration (violet) and the end of the ramp-down (blue). 45˚-65˚N is defined as the mid-latitude of the Northern Hemisphere (red dashed box). The stabilization period is defined as 150 years after the ramp-down period, after which it is masked. The results for the full integration period are presented in Fig. S2; e Time series of the standard deviation of the daily mean temperature (Tstd; green) in winter over 45˚-65˚N and the Arctic Amplification strength (AAF; blue) during the CO2 pathway (Unit: K). They are smoothed using a 15-year running mean.

In all experiments, increased CO₂ concentrations lead to pronounced Arctic warming and a substantial reduction in mid- and high latitude Tstd (peak year, violet line). This reduction is larger and more spatially extensive in high-concentration experiments. Following CO₂ removal, Tstd gradually recovers as the Arctic temperature decrease. In the L1% and M1% experiments, Tstd anomalies in the mid-latitude (45°-65°N, red boxes) are still negative (-0.4 K to -0.2 K) at the end of the ramp-down phase (blue line), but return to near-piControl (CTL) levels by the end of the stabilization period. In contrast, the H1% experiment exhibits a warming of ~5 K and a Tstd reduction of ~1 K by the end of the ramp-down phase, with anomalies persisting (+2 K in mean temperature, −0.4 to −0.2 K in Tstd) even after stabilization. The H2% experiment, despite faster tropical cooling, shows similar Tstd behavior to H1% at mid- and high latitudes.

Previous studies have reported strong links between AA and reduced mid-latitude Tstd6,11,42. The strong negative correlations between the AA strength factor (AAF) and Tstd (r < −0.96 across all simulations) reinforce this interpretation (Fig. 2e and S3). Here, AAF is determined as the difference between the Arctic and global mean temperatures (see Methods). In the M1% experiment, higher AAF and lower Tstd are observed compared to L1%, but both eventually return to near-CTL levels during stabilization. In contrast, the H1% and H2% experiments result in the strongest AA and greatest Tstd reductions, recovering incompletely after the stabilization process with an AA anomaly of about +1.5 K and a Tstd anomaly of −0.1 K.

Although our main focus is on DJF, Tstd is also important in other seasons43. The results of this experiment show that boreal spring (March–May, MAM) and boreal autumn (September-November, SON) have mean temperature and Tstd change patterns similar to those of DJF, although the magnitude of the change is smaller (Fig. S2b–d). However, in boreal summer (June-August, JJA), the reduction in Tstd is more pronounced in the Southern Hemisphere than in the Northern Hemisphere. This hemispheric contrast arises because summer warming in the Northern Hemisphere is concentrated at subpolar latitudes (60°–80°N) rather than at the pole. Ultimately, in the mid-latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere, dT/dy is less weakened, and Tstd is less reduced. Taken together, these seasonal results highlight that the strongest Tstd reductions occur during the cold season in each hemisphere.

Hysteresis response of Tstd to CO2 pathways

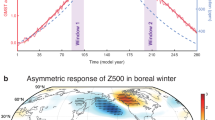

In all experiments, Tstd is consistently lower during the ramp-down phase than during the ramp-up phase at the same CO₂ concentration (Fig. 3a). For instance, the initial Tstd (~5.14 K) decreases to 4.87 K (L1%), 4.79 K (M1%), and 4.55 K (H1%) after ramp-down, corresponding to a 5-12% decline. The L1% and M1% experiments recover to their previous conditions during stabilization, but the H1% experiment exhibits incomplete recovery with a -0.22 K anomaly. The hysteresis areas (Methods) increase from 50 K∙ppm (L1%) and 87 K∙ppm (M1%) to 309 K∙ppm (H1%). The H2% experiment provides a similar value (342 K∙ppm) to H1%, suggesting that the degree of hysteresis or irreversibility of Tstd is more sensitive to the peak CO2 levels than to the removal rate.

Changes in (a) Tstd over the mid-latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere and b AAF as a function of CO2 concentration for each experiment (Unit: K). The ramp-up (RU; violet), ramp-down (RD; green), and stabilization (ST; yellow) periods are denoted by different colors. Individual ensembles and their means (XX_ENS) are denoted in light and dark dots, respectively; c Sensitivity of Tstd (left) and AAF (right) to CO2 concentration during the ramp-up and ramp-down periods for each experiment.

In contrast, AAF are higher during the ramp-down phase compared to the ramp-up at equal CO₂ levels (Fig. 3b). AAF increases by up to +2.46 K (L1%), +3.38 K (M1%), and +4.62 K (H1%) relative to the initial value (−0.14 K). While the AAF returns to baseline during stabilization in the L1% and M1% experiments, the H1% and H2% experiments maintain positive anomalies (+1.95 K and +1.84 K, respectively). Additionally, there is a strong negative correlation (r = −0.97; Figure. S4) between Tstd and AAF hysteresis response (early stabilization – CTL).

When normalized by the total CO₂ change, the Tstd response (ΔTstd/ΔCO₂) for the ramp-up phase is approximately −0.003 K·ppm⁻¹ in the L1% and M1% experiments and −0.002 K·ppm⁻¹ in the H1% experiment (Fig. 3c), indicating reduced sensitivity at higher CO2 levels. This nonlinearity likely reflects the saturation of AA as sea ice loss approaches its minimum. Supporting this interpretation, the AAF per unit CO₂ forcing (ΔAAF/ΔCO₂) is 0.026 K·ppm⁻¹ in the L1% and M1% experiments, but decreases to 0.017 K·ppm⁻¹ in H1%, indicating a plateau in the strength of AA, which limits its ability to further suppress Tstd. Additionally, the Tstd response for the ramp-down phase is weaker than that for the ramp-up phase, reinforcing the hysteresis response.

While zonal-mean diagnostics provide a general overview of Tstd evolution, regional characteristics can be strongly modulated by ocean-atmosphere interactions, land-sea contrast, and topography, which require spatially explicit analysis. Figure 4 presents the spatial distribution of changes during the ramp-up and ramp-down phases and post-stabilization differences compared to the CTL mean (see Methods; Fig. S1b–e). The H2% experiment shows a spatial pattern almost identical to H1%, with negligible differences (Fig. S5).

The first row presents the climatological mean from the CTL experiment, while the second to fourth rows show the results from the L1%, M1%, and H1% experiments, respectively. The results of the H2% experiments are shown in Fig. S5. Each row consists of four columns: the first column represents changes during the ramp-up period; the second column shows changes during the ramp-down period; the third column indicates the hysteresis; and the fourth column displays changes in the late stabilization period relative to the CTL mean. The ramp-up change is defined as the difference between the CO₂ peak period and the CTL average, while the ramp-down change is defined as the difference between the early stabilization period and the CO2 peak period. Dotted values indicate statistical significance at 95% confidence level (two-tailed t-test). The black boxes outline the areas used to define Tstd in eastern Canada (45°-65°N, 270°-300°E) and northwestern Eurasia (45°-65°N, 0°-60°E).

During the ramp-up phase, all CO2 experiments exhibit widespread reductions in Tstd, particularly over high-latitude oceans such as the Barents Sea. Although partial recovery is observed during the ramp-down phase, this recovery is spatially heterogeneous and strongly dependent on the peak CO2 level. In the L1% experiment, the hysteresis response remains mostly confined to the oceanic regions. In contrast, the M1% and H1% experiments show persistent Tstd deficits extending into continental mid-latitudes, notably over northern Eurasia and eastern Canada.

In the late stabilization period, Tstd returns to CTL levels in most areas in the L1% and M1% experiments, but substantial residual anomalies remain at H1%, particularly over the high-latitude oceans and parts of Eurasia. These regional anomalies largely account for the lack of recovery observed in the H1% and H2% experiments (Fig. 3a). However, irreversible changes are not limited to these areas. Even when regions with statistically significant hysteresis responses (dotted areas in Fig. 4) are excluded, mid-latitude Tstd still fails to fully return to CTL levels (Fig. S6).

Mechanisms for regional hysteresis in Tstd

In eastern Canada, surface warming is stronger at higher latitudes than in the southern regions, particularly under H1% experiments (Fig. 5). This pronounced meridional contrast is associated with persistent sea surface temperature (SST) anomalies in Hudson Bay (Fig. 6). These SST anomalies weaken the local dT/dy, leading to suppressed Tstd. Previous research10 also emphasized that sea-ice loss and the associated flattening of the temperature gradient drive reduced Tstd over North America.

White boxes represent the regions used to calculate the temperature gradients for Tstd in eastern Canada and northwestern Eurasia. Specifically, for eastern Canada, the meridional gradient is defined as the northern area (55˚-65˚N, 270˚-300˚E) minus the southern area (45˚-55˚N, 270˚-300˚E). For northwestern Eurasia, the meridional gradient is defined as the northern area (55˚-65˚N, 0˚-60˚E) minus the southern area (45˚-55˚N, 0˚-60˚E), and the zonal gradient is defined as the eastern area (45˚-65˚N, 0˚-30˚E) minus the western area (45˚-65˚N, 330˚-360˚E).

Similar to Fig. 5, but for SST (Unit: K).

The inverse relationship between Tstd and local dT/dy is evident in their temporal evolution, with a correlation coefficient of -0.96 (Fig. 7a; see Fig. S7a for the full period results). During the peak period (pink shading), higher peak CO₂ concentrations induce greater deviations from the initial state. Even after CO₂ removal (blue shading), experiments with higher peak CO₂ concentrations retain larger deviations, mainly due to the persistent SST hysteresis in Hudson Bay. Although SST anomalies gradually recover in L1% and M1%, they remain anomalously warm until the late stabilization period (yellow shading) in the H1% (+0.29 K) and H2% (+0.20 K) experiments. This delayed SST recovery limits the restoration of dT/dy and, consequently, Tstd in eastern Canada. The inter-experiment correlation between SST and Tstd hysteresis is statistically significant (r = –0.70; Fig. S8a), emphasizing the critical role of the delayed SST adjustment in driving regional Tstd hysteresis.

Time series of Tstd (black; box in Fig. 4) and temperature gradients in (a) eastern Canada and (b) northwestern Eurasia along the CO2 pathway for each experiment (Unit: K). Black lines show Tstd for each region, and green and violet lines show dT/dy and dT/dx, respectively, with the post-stabilization period masked. The regions defining the temperature gradients are shown in Fig. 5 and their captions. This study uses three periods labeled as follows: the red lines and shading indicate the years of peak CO2 concentration and peak period; the blue lines and shading represent the end of the ramp-down phase and early stabilization period; the yellow line and shading indicate the end of the stabilization phase and late stabilization period. The numbers in the upper corner show the correlation coefficients for the meridional (green; left) and zonal (violet; right) temperature gradients with Tstd. The results for the full integration period are presented in Fig. S7.

In northwestern Eurasia, however, the persistent negative Tstd anomalies cannot be explained solely by dT/dy. The incomplete cooling of the Barents Sea fails to offset prior warming, ultimately contributing to a weakened dT/dy (Figs. 5, 6). Although dT/dy weakens during the ramp-up phase, it recovers to similar levels (≈-7.5 K) across all experiments during stabilization (yellow and blue shading in Fig. 7b). However, Tstd remains suppressed in the H1% and H2% experiments, suggesting the involvement of additional processes. Consistent with this, the correlation between dT/dy and Tstd in this region is relatively weaker than in eastern Canada.

To identify these additional drivers, we examine the zonal temperature gradient (∂T/∂x; hereafter dT/dx) between the North Atlantic Ocean and Eurasian continent. Previous studies8,44 have reported that a reduced dT/dx due to a weakened land-sea contrast leads to suppressed Tstd in Europe. In line with this view, our results show that cooling (or minimal warming) in the North Atlantic, combined with strong continental warming, weakens dT/dx and contributes to the reduction in Tstd in the H1% and H2% experiments after CO2 removal (blue shading in Fig. 7b). This SST response is related to weakened Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) under warming45,46,47,48. Across all experiments, the AMOC strength remains below the initial level after CO2 removal (blue shading in Fig. S9).

The correlation of Tstd with dT/dx (r = –0.99 to −0.98) is stronger than that with dT/dy, and the hysteresis in Tstd significantly correlates with the dT/dx hysteresis across experiments (r = –0.50; Fig. S8b). These results suggest that, in this region, incomplete Tstd recovery is mainly governed by dT/dx rather than dT/dy. Taken together, these findings suggest that regional differences in the recovery of meridional or zonal gradients can lead to a delayed or incomplete recovery of Tstd.

Temperature variability is influenced not only by large-scale mean state temperature gradients but also by diabatic processes and eddy heat flux convergence. To clarify their relative contributions, we diagnose the principal terms of the temperature variance tendency equation (see Methods).

Our results indicate that the mean temperature gradient terms provide the most coherent explanation for regional hysteresis and partial irreversibility of Tstd. In eastern Canada, the zonal gradient-related term (first term of equation) exhibits a smaller hysteresis area and largely returns to its initial level, whereas the meridional gradient-related term (second term) fails to recover, especially in the H experiment (Fig. 8). In northwestern Eurasia, both gradient-related terms tend to recover in the L1% and M1% experiments, but the zonal gradient term displays a more pronounced irreversible change in the H experiments (Fig. 9). These regionally distinct behaviors align with the earlier inference that meridional and zonal gradients dominate the eastern Canadian and northwestern Eurasian responses, respectively.

a Mean zonal gradient-related term (\(-\bar{{u}^{{\prime} }{T}^{{\prime} }}{\partial }_{x}\bar{T}\)), b mean meridional gradient-related term (\(-\bar{{v}^{{\prime} }{T}^{{\prime} }}{\partial }_{y}\bar{T}\)) and c diabatic heating term (\(\bar{{Q}^{{\prime} }{T}^{{\prime} }}\)). The first to fourth rows correspond to the L1%, M1%, H1%, and H2% experiments, respectively. Ramp-up (RU; violet), ramp-down (RD; green), and stabilization (ST; yellow) phases are indicated by different colors. Light dots denote individual ensemble members, while dark dots represent the ensemble means (XX_ENS).

Same as Fig. 8, but for northwestern Eurasia.

In contrast, the diabatic covariance term (third term) is large in magnitude but lacks a consistent, experiment-dependent pattern that aligns with regional Tstd hysteresis (Figs. 8 and 9). Furthermore, the Tstd advection terms (fourth and fifth terms) show smaller amplitudes than the aforementioned terms and exhibit a nearly linear response to CO2 concentration, largely returning to its initial value during the stabilization period (Fig. S10). The eddy heat flux convergence terms (sixth and seventh terms) are much weaker in magnitude and highly sensitive to sampling uncertainty (Fig. S11). Except for northwestern Eurasia in the H experiment, the eddy contributions generally revert to their initial states during the stabilization period.

Overall, these diagnostics support the conclusion that large-scale mean temperature gradients are the dominant control on the spatially coherent and persistent changes in surface temperature variability identified here: meridional gradient weakening drives the eastern Canadian response, whereas zonal gradient changes govern the northwestern Eurasian response. Although diabatic and eddy processes can exert transient local influences, they cannot explain the coherent region-scale hysteresis patterns and irreversible changes observed across CO₂ ramp-up and ramp-down experiments.

Model dependence of Tstd hysteresis response

To examine the model dependence of the Tstd hysteresis identified in UKESM1-0-LL, we additionally analyze a large ensemble simulation based on the Community Earth System Model version 1 (CESM1), comprising 28 members under CO₂ ramp-up and ramp-down scenarios analogous to H1% (see Methods). Compared to most carbon dioxide removal model intercomparison project (CDRMIP) models, which provide only a single ensemble member, this dataset offers a broader statistical basis for evaluating the magnitude and spatial characteristics of Tstd hysteresis.

Despite minor differences in the initial CO₂ concentrations, the CESM1 results show qualitatively similar features to those from UKESM1-0-LL. In the mid-latitudes, Tstd during the ramp-down phase is lower than during the ramp-up phase, indicating a hysteresis response (Fig. 10a). Even after a 150-year stabilization period, Tstd stays about 0.15 K below its pre-ramp-up level. The spatial distribution also mirrors the UKESM1-0-LL results (H1% in Fig. 4), with widespread reductions over high-latitude regions during the ramp-up, followed by partial and spatially heterogeneous recovery during the ramp-down (Fig. 10b–e). However, CESM1 also shows significant hysteresis over western Canada, in addition to the two key regions identified in UKESM1-0-LL (Fig. 10d). These differences between the two models can be a result of differences in physical processes, such as ocean–atmosphere coupling and cryospheric feedback.

Overall, both CESM1 and UKESM1-0-LL consistently indicate that the DJF Tstd response to CO₂ removal is spatially heterogeneous and that hysteresis persists in several mid-latitude regions. This agreement across distinct modeling frameworks reinforces that the hysteresis response is robust and not an artifact of a single model.

Discussion

The variance budget analysis demonstrates that large-scale mean temperature gradients are the dominant factor controlling the hysteresis and irreversibility of Tstd, while diabatic and eddy heat flux convergence terms exert secondary and often noisy influences. In particular, the eddy heat flux convergence terms are small in magnitude and highly sensitive to sampling variability, which limits their ability to explain the robust, region-scale hysteresis patterns. This suggests that although transient eddies are meteorologically important, seasonal mean eddy flux diagnostics cannot adequately capture their influence on Tstd.

Motivated by this limitation, we extend our analysis to eddy kinetic energy (EKE), which provides a more direct measure of storm track activity and transient eddy intensity (see Methods). Unlike eddy flux convergence, which is highly sensitive to averaging and cancellation effects, EKE reflects the overall vigor of synoptic disturbances and thus offers a complementary diagnostic tool for assessing the role of eddy dynamics in Tstd. Previous study49 emphasized the importance of storm-track changes under global warming for mid-latitude variability.

Consistent with previous studies37,50,51,52,53,54,55, our results reveal a general reduction in storm activity across the Northern Hemisphere under increased CO₂ levels, with only partial recovery following CO2 removal (Fig. S12). This suppression is particularly pronounced in the North Pacific, likely due to the persistently weakened SST gradient. However, the inter-experimental differences in EKE remain relatively minor outside the North Pacific, and the relationship between EKE and Tstd hysteresis in eastern Canada and northwestern Eurasia is weak or statistically insignificant (Fig. S8c, d). Even when explicitly examining storm track intensity through EKE, we do not find evidence that eddy dynamics can account for the regional asymmetry or incomplete recovery of Tstd across CO₂ pathways.

Taken together, our findings indicate that the spatially heterogeneous and hysteretic responses of Tstd are primarily governed by the evolution of background temperature gradients, especially dT/dy in eastern Canada and dT/dx in northwestern Eurasia, rather than by storm-track–related eddy variability. While temperature gradients alone cannot fully explain Tstd changes, their evolution exerts the most coherent and persistent control in our simulations. Thus, the dominant mechanisms behind the Tstd hysteresis and irreversibility appear to be thermodynamic rather than dynamic in the regions of interest.

Methods

Model experiments

The UKESM1-0-LL model is a successor to the HadGEM2-ES model developed by the UK Met Office and NERC56; a detailed description can be found in a previous study57. This model is based on the low-resolution version of HadGEM3-GC3.1-LL with additional Earth system components. The model incorporated the Unified Model GA7.1 for the atmosphere, with N96 resolution (~135 km) and 85 vertical levels58, and the NEMO ocean model at 1° resolution with 75 vertical levels59,60. Additionally, it employs the CICE sea ice model61 and JULES land surface model58 for earth system simulation. Furthermore, the UKESM1 model demonstrated a high capacity for performance across a range of variables and components of the North Atlantic climate system, when evaluated against observational data62.

We also refer to the SSP1-2.6 and SSP5-3.4-OS scenarios for more realistic CO₂ reduction experiments. In these scenarios, net-zero conditions are reached around 2064 and 2062 with CO₂ concentrations of approximately 473.801 ppm and 571.015 ppm, respectively (see Fig. S1a). Based on these scenarios, we designed L1% and M1% experiments, in which CO₂ removal begins when concentrations in the H1% experiment reach these levels (51 and 70 years after the start of integration, respectively). Each experiment is conducted with three ensemble members, each initialized from the distinct initial conditions of a 1100-year CTL run. Unless otherwise specified, the results are analyzed based on the ensemble mean. The L and M experiments are integrated for 340 years, while the H experiment is run for 450 years; however, for consistency, the stabilization period is set to 150 years after the completion of ramp-down across all experiments. The results for the full integration period for all the experiments are provided in the supplementary material.

To validate the results, we additionally utilize a series of 28 ensemble simulations based on the Community Earth System Model (CESM1)63. This modeling framework has been widely used to explore various aspects of climate dynamics under CDR scenarios, including changes in large-scale circulation systems such as the AMOC48, ENSO64, and monsoon systems65,66,67.

CESM1 combines several component models: the Community Atmosphere Model (CAM5)68 with 30 vertical layers and a horizontal resolution of approximately 0.94° × 1.25°, the Parallel Ocean Program (POP2)69, the Community Land Model (CLM4)70,71 with interacting carbon and nitrogen cycles, and the Community Ice Code (CICE4)72.

The design of the experiment incorporates an idealized CO₂ pathway, beginning at pre-industrial levels of 367 ppm and increasing by 1% annually for 140 years, ultimately reaching a peak of 1468 ppm. Subsequently, it decreases symmetrically at the same rate for 140 years, returning to its original concentration. This is followed by a stabilization phase in which the CO₂ level is maintained at a constant value. Ultimately, our experiment is similar to the H1% experiment, differing only in the starting level.

Daily temperature variability

In this study, Tstd is defined as the seasonal mean of the monthly standard deviations of daily 2-meter air temperature anomalies. Anomalies are obtained by subtracting the climatological seasonal cycle of the CTL run from the daily temperature in each experiment. This definition effectively captures high-frequency temperature variability and has been widely adopted in previous studies10,28,29.

To investigate the physical processes governing the Tstd response, we diagnose the temperature variance budget following previous study73. The prognostic equation for temperature variance can be expressed as \(\frac{\partial \overline{{T}^{{\prime} 2}}}{\partial t}=-\overline{{u}^{{\prime} }{T}^{{\prime} }}\frac{\partial \overline{T}}{\partial x}-\overline{{v}^{{\prime} }{T}^{{\prime} }}\frac{\partial \overline{T}}{\partial y}+\overline{{Q}^{{\prime} }{T}^{{\prime} }}-\overline{u}\frac{\partial \left(\overline{{T}^{{\prime} 2}}\right)}{\partial x}-\overline{v}\frac{\partial \left(\overline{{T}^{{\prime} 2}}\right)}{\partial y}-\overline{{T}^{{\prime} }\frac{\partial \left({u}^{{\prime} }{T}^{{\prime} }\right)}{\partial x}}-\overline{{T}^{{\prime} }\frac{\partial ({v}^{{\prime} }{T}^{{\prime} })}{\partial y}}+{\rm{\varepsilon }}\), where overbars denote the seasonal mean and primes indicate deviations of daily values from the corresponding monthly mean. The winds are taken at 850hPa, the lowest available pressure level, and all terms are expressed in units of K2 s⁻1. The first (\(-\overline{{u}^{{\prime} }{T}^{{\prime} }}{\partial }_{x}\overline{T}\)) and second (\(-\overline{{v}^{{\prime} }{T}^{{\prime} }}{\partial }_{y}\overline{T}\)) terms represent the transport of temperature variance by eddies along the large-scale zonal and meridional temperature gradients, respectively. The vertical advection term is neglected, as horizontal advection and surface fluxes dominate near-surface (2-meter) temperature variability. The third term (\(\overline{{Q}^{{\prime} }{T}^{{\prime} }}\)) quantifies the covariance between temperature anomalies and diabatic heating (\({Q}^{{\prime} }\); units: K s⁻1). In practice, this term is approximated using surface sensible and latent heat fluxes (units: W m⁻2), which are converted to temperature units (K s⁻1) via the surface heat capacity. Radiative components are not included due to data unavailability, but are expected to contribute secondarily to daily near-surface variability. The fourth (\(-\overline{u}{\partial }_{x}\overline{{T}^{{\prime} 2}}\)) and fifth (\(-\overline{v}{\partial }_{y}\overline{{T}^{{\prime} 2}}\)) terms describe the advection of Tstd by the mean flow, reflecting its redistribution by the large-scale circulation. Finally, the sixth (\(-\overline{{T}^{{\prime} }{\partial }_{x}({u}^{{\prime} }{T}^{{\prime} })}\)) and seventh (\(-\overline{{T}^{{\prime} }{\partial }_{y}({v}^{{\prime} }{T}^{{\prime} })}\)) terms represent the zonal and meridional convergence of eddy heat fluxes, accounting for the production or dissipation of temperature variance through mesoscale eddy transport. The residual term (ε) includes contributions from unresolved processes and any errors arising from the approximations described above.

In this study, temperature variability is quantified as the standard deviation of daily temperature anomalies rather than directly from the prognostic variance tendency (\(\partial {T}^{{\prime} 2}/\partial t)\). As a result, the variance budget cannot be fully closed and the residual term cannot be explicitly diagnosed. Nevertheless, this framework effectively captures the leading dynamical and thermodynamic controls on near-surface temperature variability. By comparing the relative contributions of mean-gradient advection, eddy flux convergence, and diabatic processes, we assess the mechanisms governing Tstd changes under both CO₂ ramp-up and ramp-down scenarios.

Three key time periods

Three key periods are defined for each experiment. First, the peak period spans ±15 years from the year when the CO₂ concentration reaches its maximum, encompassing 30 DJF seasons (indicated by red shading in Fig. S1b–e). Second, the early stabilization period covers 31 years, immediately following the end of the ramp-down (blue shading). Third, the late stabilization period represents the last 31 years of the stabilization phase (yellow shading). The hysteresis response is defined as the change during the early stabilization period relative to the CTL, and all spatial patterns in the results are presented as deviations from the CTL mean.

AA strength factor

To quantitatively assess the AA strength across the experiments, we define the difference between the changes in the Arctic (60°–90°N) and the global mean near-surface air temperature (SAT) as the Arctic Amplification Factor (AAF) = Arctic [60°–90°N] SAT – global mean SAT. This approach has been used in previous studies to quantitatively express AA intensity74.

Hysteresis and irreversibility definition

In this study, hysteresis is defined as the deviation from the CTL run during the early stabilization period, and the degree of hysteresis in each experiment is quantitatively assessed by calculating the hysteresis area. Following previous research35, the area enclosed by the hysteresis loop (A) is defined as \({\rm{A}}={\int }_{{F}_{{present}}}^{{F}_{{peak}}}\left|{x}_{{up}}\left(F\right)-\,{x}_{{down}}\left(F\right)\right|{dF}\). Here, F is the atmospheric CO2 concentration, \({F}_{{present}}\) denotes the pre-industrial level, and \({F}_{{peak}}\) is the peak level for each experiment. Here, \({x}_{{up}}(F)\) and \({x}_{{down}}(F)\) represent the variable value (e.g., Tstd) during the ramp-up and ramp-down phase, respectively, at a given F.

In this study, irreversibility refers to the climate system’s failure to return to its initial state within the limited timeframe of the simulations35. This contrasts with the reversible behavior, which is characterized by a closed hysteresis loop indicating full recovery, whereas irreversible behavior is indicated by an open loop with a persistent deviation. It is important to note that irreversibility here implies limited recoverability on the experimental timescale and does not preclude the possibility of eventual full recovery over longer periods beyond the scope of this study.

Furthermore, our analysis focuses on dynamic hysteresis, which reflects the transient and time-dependent nature of the system’s response to CO₂ variations. Hysteresis can be broadly categorized into static and dynamic types75. Static hysteresis is rate-independent; the system’s state depends on the history of forcing, but not on the speed at which forcing changes. In contrast, dynamic hysteresis, which is the subject of this study, is rate-dependent, with the lag between forcing and response becoming more pronounced as the rate of change increases.

Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation index

We analyze the mean temperature, SST, and AMOC to investigate the irreversibility of the regional Tstd. The AMOC strength is calculated as \({AMOC}\left(y={avg}(20^\circ -40^\circ N)\right)={\int }_{-1000}^{0}{\int }_{{xW}}^{{xE}}{vdxdz}\).

Eddy kinetic energy

For storm track analysis, this study uses the vertically averaged EKE with mass weighting76,77,78. It is performed at three specific pressure levels (200 hPa, 500 hPa, and 850 hPa) representing the atmospheric layer of 1000–675 hPa, 675–350 hPa, and 350–0 hPa, in accordance with the approach of previous research37. To extract synoptic-scale variability, a 2–8 day bandpass filter is initially applied to both zonal and meridional wind components.

Data availability

UKESM1-0-LL and CESM1 simulation datasets supporting the results will be provided upon a reasonable request. The piControl simulation for UKESM1-0-LL used in this paper can be downloaded at https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/search/cmip6/.

Code availability

The code used in this study will be provided upon a reasonable request.

References

IPCC. Climate Change 2021 – The Physical Science Basis. Cambridge University (2023).

Serreze, M. C. & Barry, R. G. Processes and impacts of Arctic amplification: A research synthesis. Glob. Planet. Change 77, 85–96 (2011).

Screen, J. A. & Simmonds, I. The central role of diminishing sea ice in recent Arctic temperature amplification. Nature 464, 1334–1337 (2010).

Pithan, F. & Mauritsen, T. Arctic amplification dominated by temperature feedbacks in contemporary climate models. Nat. Geosci. 7, 181–184 (2014).

Stouffer, R. J. & Wetherald, R. T. Changes of variability in response to increasing greenhouse gases. Part I: temperature. J. Clim. 20, 5455–5467 (2007).

Screen, J. A. Arctic amplification decreases temperature variance in northern mid- to high-latitudes. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 577–582 (2014).

Ylhäisi, J. S. & Räisänen, J. Twenty-first century changes in daily temperature variability in CMIP3 climate models. Int. J. Climatol. 34, 1414–1428 (2014).

Holmes, C. R., Woollings, T., Hawkins, E. & De Vries, H. Robust future changes in temperature variability under greenhouse gas forcing and the relationship with thermal advection. J. Clim. 29, 2221–2236 (2016).

Chen, J., Dai, A. & Zhang, Y. Projected changes in daily variability and seasonal cycle of near-surface air temperature over the globe during the twenty-first century. J. Clim. 32, 8537–8561 (2019).

Collow, T. W., Wang, W. & Kumar, A. Reduction in northern midlatitude 2-m temperature variability due to Arctic sea ice loss. J. Clim. 32, 5021–5035 (2019).

Tamarin-Brodsky, T., Hodges, K., Hoskins, B. J. & Shepherd, T. G. Changes in Northern Hemisphere temperature variability shaped by regional warming patterns. Nat. Geosci. 13, 414–421 (2020).

Chen, S. et al. Atlantic multidecadal variability controls Arctic-ENSO connection. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 8, 44 (2025).

Chen, S. et al. Interdecadal variation in the impact of Arctic Sea Ice on El Niño–Southern oscillation: the role of atmospheric mean flow. J. Clim. 37, 5483–5506 (2024).

Cheng, X. et al. Influence of Winter Arctic sea ice anomalies on the following autumn Indian Ocean dipole development. J. Clim. 38, 3109–3129 (2025).

Cawthorne, D., de Queiroz, A. R., Eshraghi, H., Sankarasubramanian, A. & DeCarolis, J. F. The role of temperature variability on seasonal electricity demand in the Southern US. Front. Sustain. Cities 3, 644789 (2021).

Zou, Z., Li, C., Wu, X., Meng, Z. & Cheng, C. The effect of day-to-day temperature variability on agricultural productivity. Environ. Res. Lett. 19, 124046 (2024).

Linsenmeier, M. Temperature variability and long-run economic development. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 121, 102840 (2023).

Schär, C. et al. The role of increasing temperature variability in European summer heatwaves. Nature 427, 332–336 (2004).

Barriopedro, D., Fischer, E. M., Luterbacher, J., Trigo, R. M. & García-Herrera, R. The hot summer of 2010: redrawing the temperature record map of Europe. Science 332, 220–224 (2011).

Doss-Gollin, J., Farnham, D. J., Lall, U. & Modi, V. How unprecedented was the February 2021 Texas cold snap?. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 064056 (2021).

Mckinnon, K. A., & Simpson, I. R. How Unexpected Was the 2021 Pacific Northwest Heatwave? Geophys. Res. Lett. 49 (2022).

White, R. H. et al. The unprecedented Pacific northwest heatwave of June 2021. Nat. Commun. 14, 727 (2023).

Francis, J. A., & Vavrus, S. J. Evidence linking Arctic amplification to extreme weather in mid-latitudes. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39 (2012).

Francis, J. A. & Vavrus, S. J. Evidence for a wavier jet stream in response to rapid Arctic warming. Environ. Res. Lett. 10, 014005 (2015).

Serreze, M. C., Barrett, A. P., Stroeve, J. C., Kindig, D. N. & Holland, M. M. The emergence of surface-based Arctic amplification. cryosphere 3, 11–19 (2009).

Cohen, J. et al. Recent Arctic amplification and extreme mid-latitude weather. Nat. Geosci. 7, 627–637 (2014).

Dai, A., Luo, D., Song, M. & Liu, J. Arctic amplification is caused by sea-ice loss under increasing CO2. Nat. Commun. 10, 121 (2019).

Blackport, R., Fyfe, J. C. & Screen, J. A. Decreasing subseasonal temperature variability in the northern extratropics attributed to human influence. Nat. Geosci. 14, 719–723 (2021).

Dai, A. & Deng, J. Arctic amplification weakens the variability of daily temperatures over northern middle-high latitudes. J. Clim. 34, 2591–2609 (2021).

Screen, J. A., Deser, C. & Sun, L. Reduced risk of North American cold extremes due to continued Arctic sea ice loss. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 96, 1489–1503 (2015).

Vaughan, N. E. & Lenton, T. M. A review of climate geoengineering proposals. Clim. Change 109, 745–790 (2011).

Keller, D. P. et al. The carbon dioxide removal model intercomparison project (CDRMIP): rationale and experimental protocol for CMIP6. Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 1133–1160 (2018).

Frölicher, T. L. & Joos, F. Reversible and irreversible impacts of greenhouse gas emissions in multi-century projections with the NCAR global coupled carbon cycle-climate model. Clim. Dyn. 35, 1439–1459 (2010).

Boucher, O. et al. Reversibility in an Earth System model in response to CO2 concentration changes. Environ. Res. Lett. 7, 024013 (2012).

Kim, S. K. et al. Widespread irreversible changes in surface temperature and precipitation in response to CO2 forcing. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 834–840 (2022).

Kug, J. S. et al. Hysteresis of the intertropical convergence zone to CO2 forcing. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 47–53 (2022).

Hwang, J. et al. Asymmetric hysteresis response of mid-latitude storm tracks to CO2 removal. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 496–503 (2024).

Deng, J., Dai, A. & Xu, H. Nonlinear climate responses to increasing CO2 and anthropogenic aerosols simulated by CESM1. J. Clim. 33, 281–301 (2020).

Jiang, Y. et al. Impacts of wildfire aerosols on global energy budget and climate: The role of climate feedbacks. J. Clim. 33, 3351–3366 (2020).

England, M. R., Eisenman, I., Lutsko, N. J. & Wagner, T. J. The recent emergence of Arctic amplification. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2021GL094086 (2021).

Zhou, S.-N., Liang, Y.-C., Mitevski, I. & Polvani, L. M. Stronger Arctic amplification produced by decreasing, not increasing, CO2 concentrations. Environ. Res.: Clim. 2, 045001 (2023).

Schneider, T., Bischoff, T. & Płotka, H. Physics of changes in synoptic midlatitude temperature variability. J. Clim. 28, 2312–2331 (2015).

Wang, L., Chen, S., Chen, W., Wu, R. & Wang, J. Interdecadal variation of springtime compound temperature-precipitation extreme events in China and its association with Atlantic multidecadal oscillation and interdecadal Pacific oscillation. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 130, e2024JD042503 (2025).

de Vries, H., Haarsma, R. J., & Hazeleger, W. Western European cold spells in current and future climate. Geophysical Research Letters, 39 (2012).

Zhang, R. et al. A review of the role of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation in Atlantic multidecadal variability and associated climate impacts. Rev. Geophys. 57, 316–375 (2019).

Chemke, R., Zanna, L. & Polvani, L. M. Identifying a human signal in the North Atlantic warming hole. Nat. Commun. 11, 1540 (2020).

Keil, P. et al. Multiple drivers of the North Atlantic warming hole. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 667–671 (2020).

An, S.-I. et al. Global cooling hiatus driven by an AMOC overshoot in a carbon dioxide removal scenario. Earth’s. Future 9, e2021EF002165 (2021).

Chemke, R. Persistent austral winter storm track weakening beyond doubling of CO2 concentrations. Nat. Commun. 16, 1935 (2025).

Chang, E. K., Guo, Y., & Xia, X. CMIP5 multimodel ensemble projection of storm track change under global warming. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos., 117 (2012).

Zappa, G., Shaffrey, L. C., Hodges, K. I., Sansom, P. G. & Stephenson, D. B. A multimodel assessment of future projections of North Atlantic and European extratropical cyclones in the CMIP5 climate models. J. Clim. 26, 5846–5862 (2013).

Lehmann, J., Coumou, D., Frieler, K., Eliseev, A. V. & Levermann, A. Future changes in extratropical storm tracks and baroclinicity under climate change. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 084002 (2014).

Tamarin-Brodsky, T. & Kaspi, Y. Enhanced poleward propagation of storms under climate change. Nat. Geosci. 10, 908–913 (2017).

Harvey, B. J., Cook, P., Shaffrey, L. C. & Schiemann, R. The response of the Northern Hemisphere storm tracks and jet streams to climate change in the CMIP3, CMIP5, and CMIP6 climate models. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmos. 125, e2020JD032701 (2020).

Priestley, M. D. K. & Catto, J. L. Future changes in the extratropical storm tracks and cyclone intensity, wind speed, and structure. Weather Clim. Dyn. 3, 337–360 (2022).

Collins, W. J. et al. Development and evaluation of an Earth-System model–HadGEM2. Geosci. Model Dev. 4, 1051–1075 (2011).

Sellar, A. A. et al. UKESM1: Description and evaluation of the UK Earth System Model. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 11, 4513–4558 (2019).

Walters, D. et al. The Met Office Unified Model global atmosphere 7.0/7.1 and JULES global land 7.0 configurations. Geosci. Model Dev. 12, 1909–1963 (2019).

Kuhlbrodt, T. et al. The low-resolution version of HadGEM3 GC3. 1: Development and evaluation for global climate. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 10, 2865–2888 (2018).

Storkey, D. et al. UK Global Ocean GO6 and GO7: A traceable hierarchy of model resolutions. Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 3187–3213 (2018).

Ridley, J. K. et al. The sea ice model component of HadGEM3-GC3. 1. Geosci. Model Dev. 11, 713–723 (2018).

Robson, J. et al. The evaluation of the North Atlantic climate system in UKESM1 historical simulations for CMIP6. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 12, e2020MS002126 (2020).

Hurrell, J. W. et al. The community earth system model: a framework for collaborative research. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 94, 1339–1360 (2013).

Liu, C. et al. Hysteresis of the El Niño–southern oscillation to CO2 forcing. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh8442 (2023).

Oh, H. et al. Contrasting hysteresis behaviors of Northern Hemisphere land monsoon precipitation to CO2 pathways. Earth’s. Future 10, e2021EF002623 (2022).

Paik, S., An, S. I., Min, S. K., King, A. D. & Shin, J. Hysteretic behavior of global to regional monsoon area under CO2 ramp-up and ramp-down. Earth’s. Future 11, e2022EF003434 (2023).

Paik, S. et al. Exploring causes of distinct regional and subseasonal Indian summer monsoon precipitation responses to CO2 removal. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 7, 305 (2024).

Neale, R. B. et al. Description of the NCAR Community Atmosphere Model (CAM 5.0). NCAR Technical Note NCAR/TN-486+STR, National Center for Atmospheric Research (2012).

Smith, R. et al. The Parallel Ocean Program (POP) reference manual: Ocean component of the Community Climate System Model (CCSM) and Community Earth System Model (CESM). LAUR-10-01853, Los Alamos National Laboratory (2010).

Oleson, K. W. et al. Technical Description of version 4.0 of the Community Land Model (CLM). NCAR Technical Note NCAR/TN-478+STR, National Center for Atmospheric Research (2010).

Lawrence, D. M. et al. Parameterization improvements and functional and structural advances in version 4 of the Community Land Model. J. Adv. Model. Earth Syst. 3 (2011).

Hunke, E. C. & Lipscomb, W. H. CICE: the Los Alamos Sea Ice Model Documentation and Software User’s Manual Version 4.1. LA-CC-06-012, Los Alamos National Laboratory (2010).

Peixoto, J. P., & Oort, A. H. Physics of climate. New York: American Institute of Physics (1992).

Yim, B. Y., Yeh, S. W. & Kug, J. S. Inter-model diversity of Arctic amplification caused by global warming and its relationship with the Inter-tropical Convergence Zone in CMIP5 climate models. Clim. Dyn. 48, 3799–3811 (2017).

Goldsztein, G.H. et al. Dynamical hysteresis without static hysteresis: scaling laws and asymptotic expansions. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 57, 1163–1187 (1997).

O’Gorman, P. A. Understanding the varied response of the extratropical storm tracks to climate change. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 19176–19180 (2010).

Shaw, T. A. et al. Storm track processes and the opposing influences of climate change. Nat. Geosci. 9, 656–664 (2016).

Chemke, R., Ming, Y. & Yuval, J. The intensification of winter mid-latitude storm tracks in the Southern Hemisphere. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 553–557 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean Government (MSIT) (NRF2021R1A2C3007366), Korea Meteorological Administration Research and Development Program under Grant RS-2025-02309058, and the Human Resource Program for Sustainable Environment in the 4th Industrial Revolution Society. Model simulation and data transfer are supported by the National Center for Meteorological Supercomputer of the Korea Meteorological Administration (KMA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.-K.M. and S.-H.K. designed the study and conducted the analysis. S.-I.A., M.-K.K., H.-S.P., J.-Y.P., D.-S.R.P. contributed to the interpretation of results. H.-M.S., Y.-H.B., and K.-O.B. performed model experiments. All authors contributed to writing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, SH., Min, SK., An, SI. et al. Hysteresis response of Northern Hemisphere winter temperature variability under different CO₂ removal pathways. npj Clim Atmos Sci 8, 388 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01277-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41612-025-01277-5