Abstract

The larvae of the greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella, are gaining prominence as a versatile nonmammalian in vivo model to study host–pathogen interactions. Their ability to be maintained at 37 °C, coupled with a broad susceptibility to human pathogens and a distinct melanization response that serves as a visual indicator for larval health, positions G. mellonella as a powerful resource for infection research. Despite these advantages, the lack of genetic tools, such as those available for zebrafish and Drosophila melanogaster, has hindered development of the full potential of G. mellonella as a model organism. Here we describe a robust methodology for generating transgenic G. mellonella using the PiggyBac transposon system and for precise gene knockouts via CRISPR–Cas9 technology. These advances significantly enhance the utility of G. mellonella in molecular research, paving the way for its widespread use as an inexpensive and ethically compatible animal model in infection biology and beyond.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

The larval stage of the greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella, is increasingly recognized as a valuable in vivo mammalian replacement model, particularly in the fields of infection, immunology and inflammation1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9. They undergo melanization in response to immune challenges and have broad susceptibility to a range of medically important microbes (reviewed in refs. 1,2,3,5,10,11). Their capacity to be maintained at 37 °C confers a considerable advantage over other model systems such as fruit flies or zebrafish, particularly for studies involving human pathogens. Moreover, unlike vertebrate models, G. mellonella larvae are not subject to stringent regulatory or licensing requirements. Finally, recent discoveries, such as their unique ability to metabolize polyethylene and polystyrene, independent of their microbiota12,13,14,15, could yield advances in our understanding of plastic degradation and solutions to plastic waste, underscoring the potential for broad application of G. mellonella larvae in research settings.

The availability of multiple G. mellonella genomes, first published in 201813,16,17,18, have resulted in an expanded set of molecular and cellular tools, alongside transcriptomic and proteomic datasets19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. These resources have considerably increased the potential of G. mellonella to be developed as an alternative to mammalian infection models. However, the absence of robust genetic manipulation techniques—critical for the insertion, deletion and engineering of genes—remains a limiting factor. Although such techniques have been widely applied to other insects, transgenic and genetically modified approaches in G. mellonella have not yet been developed.

Among the most widely adopted tools for genetic modification are the PiggyBac transposase system and CRISPR–Cas9, both of which offer powerful, complementary means of creating transgenic organisms and targeted gene knockouts. The PiggyBac transposase system, isolated from Trichoplusia ni29, enables the seamless integration of genetic material into TTAA nucleotide sequences across a wide array of animal species, facilitated by a separately provided transposase enzyme30,31. The ability of this method to insert large genetic cargos32 without the need for specific landing sites, while advantageous, also poses challenges, including variable integration efficiency33 and the potential for disruption of endogenous gene function if the insertion occurs within a coding region. CRISPR–Cas9-mediated mutagenesis has rapidly become the gold standard for targeted genetic modification, surpassing other techniques such as zinc finger nucleases and transcription activator-like effector nucleases34,35,36. This technique uses a bipartite type II CRISPR system to direct a CRISPR-associated nuclease (Cas) to specific genomic loci via an RNA guide with a complementary base sequence37,38,39. The resultant double-strand breaks are repaired with varying fidelity by different DNA repair pathways, enabling either the disruption of endogenous gene function or the insertion of exogenous genetic sequences40.

In this study, we successfully apply both the PiggyBac and CRISPR–Cas9 systems to G. mellonella, demonstrating their efficacy in generating transgenic lines and gene knockouts. These advances considerably enhance the genetic tractability of G. mellonella, establishing a foundation for its broader application across diverse research domains.

Results

Embryonic development timings indicate a 6-h window for microinjection

Galleria mellonella were reared at 30 °C and embryos were deposited on egg papers, followed by manual collection and subsequent fixation. Imaging of early embryos, stained for DNA, revealed developmental timings post oviposition (PO). In embryos aged 1.25–2.75 h PO, sperm nuclei could be observed in transit toward the ova nucleus, with polar bodies migrating toward the boundary of the embryo (Fig. 1a–c). A small proportion of embryos in this time window were also observed to have undergone their first mitotic division, with some beginning their second.

a–c, In the first 1.25–2.75 h PO, the sperm nuclei (purple circle) can be seen moving toward the ovum nuclei (yellow circle) (a); and nuclei resembling polar bodies gather toward the periphery of the embryo (white arrows) (b). This timeframe appears to cover up to the second mitotic division (c). d,e, From 2.5 h to 5.5 h PO, energids migrate toward the periphery with a bias to the anterior pole (d); and by 4.5–5.5 h PO, the first ones have just reached the periphery (e). Nuclei are dividing synchronously at this point as they share a common cytoplasm. f, All energids have reached the periphery by 6.25 h and are still dividing together. g,h, However, synchronicity begins to be lost from 6 h to 8 h, potentially indicating the onset of cellularization. In g, all nuclei appear to be coming out of telophase; however, in h, nuclei appear in metaphase, telophase and interphase, with some showing decondensed chromatin.

In batches of embryos collected within the next 3.5 h (2.75–6.25 h PO), increased numbers of nuclei, migrating toward the periphery of the embryo, were observed (Fig. 1d–f). The nuclei within an individual embryo seemed to be at the same cell cycle stage, as determined by chromosome condensation, alignment and segregation, indicating that, at this time point, they still share a common cytoplasm (Fig. 1d–f). This synchronicity was lost, however, in batches of embryos fixed and imaged 8 h PO, indicating that cellularization occurs between 6.25 h and 8.00 h (Fig. 1g,h). As embryos developed further, a difference in nuclei spacing became noticeable, with the future embryonic tissue being more densely nucleated by 14 h (Supplementary Fig. 1). Together, this analysis provides a time window for injection to generate stable germline transformants within 0–6 h of development following oviposition at 30 °C.

pBmhsp90:hyPBase is suitable as a donor plasmid for PiggyBac mutagenesis in G. mellonella

To inject exogenous material definitively before cellularization, we performed manipulations on 0–2-h-old dechorionated embryos (Methods). Perhaps unsurprisingly, injection with piggyBac DNA plasmids caused substantial mortality (Table 1), with only 6–19% of injected embryos from the five different experiments surviving to pupation. Hatch rates were much lower for injection with piggyBac DNA plasmids than injections with only injection buffer (27.2% for plasmid DNA versus 69.0% for injection buffer only)41. However, given the large number of embryos that can be collected and injected within a few hours, we proceeded with this methodology to screen for transformants.

Initially, we injected a 200:200 ng/μl plasmid mix consisting of pBmhsp90:GFP/3xP3:DsRed donor and pHA3PIG (Bombyx mori actin-3 driven) helper, as used by Tsubota et al.42. This plasmid was expected to drive green fluorescent protein (GFP) ubiquitously (under the control of the hsp90 promoter) and dsRed in the developing eye (under the control of the P3 promoter). However, we did not observe any GFP or dsRed fluorescence in any G0 larvae or G1 G. mellonella, despite the large number of embryonic injections (N = 4,692) and G1 broods screened (N > 600) (Table 1). This finding indicated either that this helper plasmid had very low activity in G. mellonella, due to inactivity of the unmodified transposase or incompatibility of the B. mori actin-3 promoter, or (in what was considered a less likely scenario) that both reporter constructs within the donor expression cassette were unable to efficiently drive fluorescent protein expression.

To address this issue, we investigated whether an alternative promoter–transposase helper construct could increase transformation efficiency sufficiently to generate a transgenic line. Two sets of injections were performed with the same donor plasmid, pBmhsp90:GFP/3xP3:DsRed, but at a higher concentration (400 ng/μl), either with 200 ng/μl of the original pHA3PIG helper or with a different helper plasmid, pBmhsp90:hyPBase, which encodes a hyperactive PiggyBac transposase mutant, driven by the same Bombyx hsp90 upstream sequence as used in the donor42 (Fig. 2a). Although the hyperactive transposase used was codon optimized for expression in mammalian rather than insect systems, Eckermann and colleagues had previously found no significant difference in transformation efficiency between insect and mammalian codon-optimized hyperactive transposases in multiple insect species43. Mosaic green fluorescence was observed in several G0 larvae from the pBmhsp90:hyPBase injection group, while none was observed in the pHA3:PIG group (Table 1). From the pBmhsp90:hyPBase group, eGFP- and DsRed-positive transgenic larvae were recovered from the brood of a single G0 adult–wild-type (WT) cross (Table 1). Although the promoters differed and direct comparisons cannot be drawn, the pBmhsp90:hyPBase plasmid might be a more suitable helper in this species.

a, The helper and donor constructs used to develop the Bmhsp90:GFP/3xP3:DsRed transgenic strain are represented. b, Both eGFP and DsRed expression can be observed in the late embryo (top row; G4 animals), first instar larvae (middle row; G2 animals) and fourth instar larvae (bottom row; G4 animals). eGFP expression is very bright within the unmelanized tissues, while DsRed expression is limited to neural tissue including the brain, optic nerves and stemmata. c, The transgenic cassette appears to be inserted within an inorganic phosphate cotransporter gene cluster on chromosome 12 in the intergenic space between LOC113515287 and LOC113512789, adjacent to a small cluster of putative (put.) odorant-like receptors.

The B. mori hsp90 promoter sequence drives strong but not constitutive activity in G. mellonella, while the 3xP3 promoter might be neural specific

In larvae transformed with pBmhsp90:GFP/3xP3:DsRed, bright eGFP expression could be observed in larval, pupal and adult stages. However, instead of ubiquitous expression, eGFP expression in embryos appeared to be limited to the vitellophages and was absent both from the germ band and developing nascent larva until just before eclosion (Fig. 2b). In larvae, eGFP expression was strongest in the muscle, fat body and Malpighian tubules with weaker expression seen in the gut, silk glands and epidermis.

As expected, DsRed expression was observed to be present in, and solely within, neural tissue, with the strongest expression in the eyes, optic nerves, brain and segmental ganglia (Fig. 2b). It was first observed at around day 5 of embryonic development at 30 °C, at the anterior and in a segmented pattern within the embryo, perhaps corresponding to the developing eyes and segmental neural centers.

To map the insertion site in one of these transformants, inverse polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was undertaken. The flanking regions of the Bmhsp90:GFP/3xP3:DsRed expression cassette were found to correspond to the proximal end of chromosome 12, within an intergenic region between LOC1131515287 and LOC1131512719, in a cluster of putative inorganic phosphate cotransporters (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 2). Visual monitoring of outward health and developmental timings for this transgenic line, across multiple generations, showed no difference to WT, suggesting that transgene expression at this locus is not deleterious to the organism.

Generation of G. mellonella α-tubulin and histone cellular reporter lines

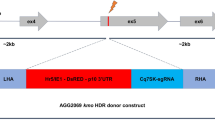

To investigate whether a G. mellonella hsp90 promoter might drive constitutive expression, and whether PiggyBac would be suitable for creating reporters of cellular and subcellular dynamics, two DNA constructs were generated. In the first construct (Gmhsp90:GFP-αtub1b), the G. mellonella α-tubulin 1b gene—one of several α tubulin genes in the G. mellonella genome—was N-terminally tagged with eGFP and placed downstream of a 2-kb region corresponding to the G. mellonella hsp90 promoter (Fig. 3a). In the second construct, a 2-kb region corresponding to the B. mori hsp90 promoter was placed upstream of the G. mellonella monocistronic histone 2A variant, with a C-terminal mCherry tag (Bmhsp90:his2av-mCh) (Fig. 3a).

a, Constructs used to generate transgenic lines Gmhsp90:GFP-αtub1b and Bmhsp90:his2av-mCh. b, Gmhsp90:GFP-αtub1b larvae (top left) with fat body tissue fixed and stained with an anti-GFP antibody (top right); and Bmhsp90:his2av-mCh (bottom left) larvae with fat body and dorsal neural ganglion imaged live (bottom right). Zoomed panels are not images from the same larvae. Expected cytoskeletal distribution of eGFP was observed, corresponding with expected localization of tubulin, while a nuclear localization was observed for mCherry. c, Brightfield (BF), mCherry and eGFP tissue expression patterns in a strain with both Bmhsp90:his2av-mCh/Gmhsp90:GFP-αtub1b expression cassettes. Strong fat body expression was observed for both fluorophores, with the G. mellonella hsp90 promoter that seemed to drive strongest expression in gut and silk gland, while the B. mori hsp90 promoter was stronger in epidermal and muscle tissue (not shown), but very weak in silk glands and Malpighian tubules.

Hatch rates for injected embryos were similar for both constructs, at around 26% survival (Table 1). However, while 20% of the 1,450 Gmhsp90:GFP-αtub1b injected embryos reached pupation, only 6% of the 1,280 embryos injected with Bmhsp90:his2av-mCh reached this stage (Table 1). This result may indicate additional toxicity associated with the integration of the histone expression cassette, either due to overexpression of this histone variant or the specific insertion locus.

Transgenic lines for both constructs were obtained. Although inverse PCR failed to locate the insertion locus for either line, fluorescence corresponding to microtubules and nuclei, respectively, could be observed in embryos (not shown) and larvae (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, we found differences between the expression pattern of the B. mori and G. mellonella hsp90-integrated lines. Strong eGFP expression for the G. mellonella hsp90-GFP-αtub1b construct was observed in the fat body, hindgut, midgut and silk glands, with somewhat weaker expression in the Malpighian tubules (Fig. 3c), as well as the muscle and epidermis (not shown). By contrast, the B. mori hsp90 promoter drove strong expression of mCherry-His2Av in the fat body, weaker expression in the gut, and appeared absent or present at very low levels in the silk glands and Malpighian tubules (Fig. 3c). This finding is in contrast with results previously observed for eGFP expression in the Bmhsp90:GFP/3xP3:DsRed strain, where very strong and moderate expression was observed in Malpighian tubules and silk gland, respectively, suggesting either insertion-specific differences or selective suppression of His2av expression in those tissues. Embryonic expression was weak for both promoters, although some germline activity could be observed for the G. mellonella hsp90 promoter, in contrast to the vitellophages in the B. mori hsp90 line (not shown).

CRISPR–Cas9-mediated mutagenesis in G. mellonella

Although PiggyBac transgenesis is a useful tool, we sought to further extend the molecular engineering capabilities of G. mellonella by testing the efficacy of CRISPR–Cas9, with respect to gene knockouts. An injection mix consisting of a KCl-buffered ribonucleoprotein complex of single sgRNA (in molar excess) targeting the eGFP sequence44 and mCherry-tagged Cas9 was injected into embryos homozygous for the Bmhsp90:GFP/3xP3:DsRed transgenic cassette. A hatch rate of 31% was observed, similar to that observed for PiggyBac injections, yet survival to pupation was low at only 7% (Table 1).

Among the developing G0 larval offspring, a range of eGFP knockout phenotypes was observed, ranging from minor fluorescence mosaicism to an almost complete absence of GFP fluorescence in somatic tissues (not shown). All G0 adults were outcrossed to WT mates, and the resulting broods were screened for eGFP-negative G1 larvae that were positive for DsRed expression in their stemmata (Fig. 4a). A total of 50% (14/28) of broods contained such knockout larvae, including offspring from G0 parents that had shown no, or very minor, loss of GFP expression. Analysis of the resulting CRISPR mutants via Sanger sequencing revealed a combination of small indels and larger deletions around the guide target site (Fig. 4b). Off-target effects were not screened for; instead, potential crispants (CRISPR-modified G0s individuals) and their progeny were outcrossed to WT strains for three generations before creating a stable line, thus minimizing accumulated mutations.

a, Bmhsp90:GFP/3xP3:DsRed G0 larva I–V have an expression cassette inserted into their genome resulting in the expression of eGFP visible in somatic unmelanized tissue and the expression of dsRed in both eye (solid arrow) and neural (dashed arrow) tissue. Larva I is the G1 offspring of individuals of the same transgenic line as larvae II–V, but injected with a Cas9/sgRNA ribonucleoprotein targeting the eGFP gene, causing a heritable loss of function in the eGFP gene, but retaining the eye-specific dsRed expression. Larvae II–V are of the parent strain and were not injected with Cas9/sgRNA. b, Mutations within the coding sequences of 12 different GFP-negative G1 individuals. The G1 larvae are offspring from individuals crosses of Bmhsp90:GFP/3xP3:DsRed G0s injected with an sgRNA targeting the N terminus of the eGFP sequence and crossed to WT mates. The top line is the native eGFP sequence, with the sequence complementary to the sgRNA highlighted in green and the PAM sequence highlighted in red.

Discussion

The development of advanced genetic tools for model organisms such as rodents, Drosophila melanogaster and zebrafish has revolutionized our ability to understand and interrogate their biology, shedding light on fundamental processes such as development, physiology and their response to environmental perturbations. Moreover, the capacity to genetically engineer these organisms to mimic human disease phenotypes has provided invaluable insights into the modes of action and potential efficacy of new therapeutic interventions. In this context, the establishment of methods for genetic modification of G. mellonella represents a transformative advancement with potentially profound implications for biomedical research.

Here, we have demonstrated the feasibility of both PiggyBac-mediated transformation for gene tagging and expression, as well as gene knockout using CRISPR–Cas9 technology. Both techniques rely on the injection of exogenous nucleic acid into G. mellonella embryos during the initial syncytial stage of development. Analysis of G0 pupae from multiple experiments using different PiggyBac constructs demonstrates that the proportions of embryos hatching, progressing to pupation and reaching eclosion vary between experiments and constructs, highlighting areas for potential improvement.

As it currently stands, PiggyBac transformation efficiencies remain low compared with those seen in other insects; in Lepidoptera, Tamura et al.45 reported efficiencies of 1.5% and 2.0%, versus the maximum of 0.1% efficiency that we were able to achieve (number of G1-positive broods versus number of injected eggs). We have also observed that different promoter–transposase constructs can have large effects on the transposition frequency. It is likely that further optimization of our injection methodology and helper constructs will result in increased rates of transformation. Notably, further direct comparisons between both promoters and transposases are needed to elucidate the extent to which either element is hindering integration efficiency. Exploration of DNA constructs with higher maternal or embryonic promoter activity, G. mellonella-specific codon optimization or the co-injection of transposase mRNA could boost integration at an earlier stage, resulting in increased transmission to the G. mellonella germline. In addition, the spherical nature of G. mellonella embryos and the absence of phenotypic markers for the anterior–posterior axis precludes targeted microinjection to the germline precursor/pole cell region, an approach that has proved valuable in enhancing transgenesis efficiency in insects such as B. mori45. Generating a transgenic G. mellonella line where the anterior–posterior pole of fertilized oocytes is highlighted (for example, through fluorescently tagged determinants, such as Nanos) could overcome this limitation, although a Nanos promoter/terminator construct described by Heryanto et al.46 did not localize mScarlet to the presumptive germ region47. Nonetheless, the PiggyBac donor integration rate using the methodology described here is generally at, or above, ~1 % (Table 1), making the technique as it currently stands useful to researchers seeking to adopt genetically modified G. mellonella as a model. The use of inverse PCR failed to generate distinct products for sequencing; as such, we were unable to identify two of the three PiggyBac insertion sites. This could potentially be due to issues with priming in the reactions or large numbers of products produced due to the regularity of HpaII sites. Alternative methods such as splinkerette PCR or whole-genome sequencing approaches could produce more reliable results in the future.

The application of CRISPR–Cas9-mediated mutagenesis, now established in various insect species, represents another substantial advancement. CRISPR–Cas9 offers a robust alternative to RNA interference, which has been shown to work in G. mellonella48,49, but with variable efficiency in other lepidopterans, possibly due to compensatory gene upregulation50,51,52. Again, although our current efficiencies are low, with further optimization of ribonucleoprotein concentrations and injection timing, survival rates and mutagenesis efficacy in G. mellonella could potentially reach levels comparable to those reported in D. melanogaster, Tribolium castaneum, B. mori and other Lepidoptera.

Given that G. mellonella is predominantly used as a model to understand microbial infection and host–pathogen interactions, the methods described in this study have the potential to considerably enhance its utility and adoption. While this work focuses on the generation of reporter lines to visualize subcellular structures (the microtubule cytoskeleton and nuclei), future applications could include reporters of larval health status. Examples include reporters driving fluorescence throughout the larvae, or in particular cell subtypes, upon infection by particular pathogens or upon systemic release of antimicrobial peptides. Such ‘sensor’ moth larvae would provide a quantifiable readout of health, complementary to current observation of melanisation. The ability to use CRISPR–Cas9 to knock out individual genes or entire gene families, or replace them with humanized disease variants, could also provide a bank of knockout lines that more accurately represent phenotypic traits found in human diseases, facilitating the screening of new therapeutics or interventions. Moreover, the ability to engineer G. mellonella not only broadens the scope of research and versatility of this model but also aligns with the principles of the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction and Refinement). By offering a viable alternative or complementary system to rodent models, uptake of G. mellonella could lead to a reduction in the use of mammalian models in infection research and beyond, thus positively addressing both ethical and cost considerations of robust scientific animal research.

Methods

Animals and rearing

Ethical approval was sought and approved by the University of Exeter ethics review panel, and project approval was granted by the genetically modified organisms project panel. A completed ARRIVE guidelines checklist is included online (Supplementary Data 1).

An inbred WT G. mellonella colony at the Galleria mellonella Research Centre (GMRC) was reared on an artificial honey diet (Diet 353) at 30 °C, constant darkness. Originally derived from commercially bred UK larvae, the GMRC colony has been continuously bred at the University of Exeter as an isolated colony since 2016. A more detailed rearing protocol is described in ref. 41.

Transgenic strains were reared at 30 °C on the same diet in large polypropylene fly vials (10 cm × 5 cm, Darwin Biological) with foam bungs to prevent L1 larval escape. At the late larval wandering stage, larvae were transferred to Petri dishes containing diet and allowed to pupate. Pupae were transferred to small polyethylene terephthalate jars with 5-μm wire mesh lids, and the adults were allowed to oviposit on egg papers.

Fixation and immunostaining

Jars of WT adults were kept at 30 °C in constant darkness and allowed to lay on egg papers overnight. The egg papers were removed, and the embryos discarded before replacing the clean egg papers into the jars. The moths were allowed to oviposit undisturbed for 1 h in darkness, before the papers were again removed and the embryos collected and labeled as 0–1 h old. Embryos were allowed to develop for set time periods before dechorionating with agitation for 2 min in a diluted solution of thin bleach (1.25% active chlorine) and 0.05% Triton X-100.

Aged embryos were transferred into a 1.5-ml Eppendorf tube containing 500 μl of heptane and 500 μl of methanol, inverted several times until the majority of the embryos at the interphase of the two solutions dropped into the methanol. The heptane and any embryos remaining at the interphase were removed using a Pasteur pipette, before washing twice in fresh methanol. Embryos were stored at 4 °C for no more than a week, until use.

Embryos were rehydrated sequentially for 15 min each in 75:25 and 50:50 methanol:PBS + 0.01 % Triton X-100 (PBST), before further 15-min rehydration in PBST. They were stained with 0.5 mg/ml Hoechst 33258 in PBST for 20 min at room temperature, followed by three 5‑min washes in PBST.

Larval tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS + 0.1% Tween for 1 h, stained overnight with a rabbit anti-GFP polyclonal antibody (Abcam 6556) and labeled using an appropriate Alexa Fluor 488 secondary dye (Molecular Probes).

Imaging

Embryos were mounted on microscope slides between two stacked ring binder reinforcement stickers in Vectashield mounting medium (VectorLabs) and imaged using a Nikon TE-2000U inverted microscope. Larvae were anesthetized using CO2 and imaged under a Leica MZ10F fluorescence stereomicroscope with a GXCAM HiChrom-HR4 HiSens camera. Fixed larval tissues were imaged using a Leica SP-8 confocal microscope.

RNA/DNA extraction and PCR

Galleria mellonella tissue samples were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in Eppendorf tubes using disposable microcentrifuge pestles (DWK Life Sciences), then stored on ice until use.

Total RNA was extracted from homogenates of 0–6 h embryos and the posterior third of larvae (larval end segment) using a TRIzol reagent/chloroform extraction according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and ethanol-precipitated before either immediate use or storage at –80 °C. cDNA was generated using a High-Capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems) using the manufacturer’s protocol.

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole or partial tissue samples, depending on the size, using the New England Biolabs (NEB) gDNA extraction kit with NEB’s insect tissue protocol.

DNA fragments for diagnostic purposes were amplified using a GoTaq Hot Start mastermix (Promega). For all other purposes (including sequencing), fragments were amplified using a KOD Hot Start polymerase kit (Toboyo), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Plasmids

Plasmids pHA3PIG54 and pBAChsp90GFP-3xP3DsRed42 were a kind gift from Professor Hideki Sezutsu. Henceforth, we will refer to pBAChsp90GFP-3xP3DsRed as pBmhsp90:GFP/3xP3:DsRed to differentiate between the different G. mellonella and B. mori hsp90 promoters. All plasmids were assembled using Gibson assembly.

pBmhsp90:hyPB was generated by inserting the B. mori hsp90 2.9-kb fragment from pBmhsp90:GFP/3xP3:DsRed and the hyper-active Piggybac transposase from SPB-DNA (Hera Biolabs) upstream of WT PiggyBac transposase 3′ untranslated region from pHA3PIG in the digested backbone of pHA3PIG.

pGmhsp90:GFP-αtub1b was generated by creation of an expression cassette consisting of the 2-kb upstream region of G. mellonella hsp83 (hsp90) placed directly upstream of an N-terminal eGFP-tagged G. mellonella α-tubulin 1b cDNA sequence (LOC113521067) and SV40 polyA terminator, which was inserted between the two PiggyBac inverted terminal repeats of the digested pBmhsp90:GFP/3xP3:DsRed backbone.

pBmhsp90:histone2av-mCh/3xP3:DsRed was generated by digesting the pBmhsp90:GFP/3xP3:DsRed plasmid with PmlI and AscI and inserting a synthesized fragment consisting of the G. mellonella Histone 2AV sequence (LOC113518755) connected to mCherry, via a short linker with a SV40 polyA terminator.

All plasmids were propagated in NEB 10β cells and midi-prepped using a Nucleobond Xtra midi kit (Macherey-Nagel). They were ethanol precipitated before reconstituting in either nuclease-free water or filter-sterilized 5 mM phosphate/5 mM KCl injection buffer, pH 7.4. Annotated plasmid sequences and maps are available in Supplementary Datasets 1–7 and Supplementary Figs. 3–9.

Embryo microinjection

The injection protocol is described in detail in ref. 41. In brief, embryos were collected from communal adult jars containing 75 adults of mixed sex and allowed to age for 1–2 h at 30 °C, before being dechorionated with a diluted bleach solution, aligned along the edge of coverslips and glued to glass slides.

Injection mixes were made by adding plasmids, guides or proteins sequentially to the injection buffer and checking total concentration using a Nanodrop. Before use, injection mixes were spun at 16,000g for 1 min, before gently aspirating off the upper 90% and transferring it to a fresh Eppendorf tube. The spun mixes were then stored on ice until use.

Embryos were injected using an Eppendorf Injectman 4 microinjection system mounted to a Nikon Eclipse TE2000-U inverted microscope with a small volume of injection mix, equal to a droplet roughly 1/5 diameter of the embryo. For Piggybac-mediated mutagenesis, embryos were injected between 3 h and 5 h PO, and the injection droplet was placed on the side of the embryo relative to the putative anterior–posterior poles. For CRISPR–Cas9, embryos were injected at 2.0–3.5 h PO and injection droplets were placed in the center of the embryo.

Post-injection rearing and screening

After injection, embryos were reared as described in ref. 41. Late-stage G0 larvae larvae were removed from the diet and screened for visible changes in somatic fluorescence using a fluorescence stereomicroscope (Leica MZ10F or Olympus SZX-16). Those demonstrating mosaic fluorescence were separated into fresh diet. Once pupated, putative transformants were sexed based on genital morphology visible in the terminal segments, and G0 adults were mated either to a mixture of siblings and WTs (for PiggyBac-injected G0s) or WTs only (for CRISPR–Cas9-injected G0s). Embryos were collected from each cross, and the progeny were screened for visible changes in somatic fluorescence at both embryonic and larval stages. Stable transgenic lines were generated by selecting the G1 generation with the brightest phenotype and outcrossing for two to three further generations, before sibling mating and screening for the brightest offspring. These were then sibling mated and screened for consistent phenotype over multiple generations.

Guide RNA synthesis and Cas9

An anti-eGFP sgRNA previously described by Jao et al.44 was synthesized in vitro, as described in Burger et al.55. A DNA template for the sgRNA was generated by PCR amplification using two primers (sgRNA-EGFP forward and a PAGE-purified sgRNA reverse), followed by purification of the PCR product (Promega). In vitro transcription was performed overnight at 37 °C using a T6 RNA polymerase (Roche), followed by DNase treatment, RNA cleanup and validation for size and presence of a single band on a denaturing MOPS–formaldehyde gel. The sgRNA was stored at −80 °C until use.

The Cas9 protein used was a kind gift from Professor Christian Mosimann and is a modified version of S. pyogenes Cas9 fused in frame with an additional C-terminal HA tag, a bipartite nuclear location sequence, an mCherry polypeptide sequence and an additional monopartite nuclear location sequence at the C terminus after the mCherry sequence55.

Mutation analysis and sequencing

Piggybac insertion sites were verified via inverse PCR. gDNA from G1 transgenic larvae was digested for 2 h using HpaII, followed by heat inactivation. Genomic fragments were then self-ligated using T4 DNA ligase at 4 °C overnight, followed by ethanol precipitating. The genomic regions surrounding the Piggybac entry sites were amplified through PCR using two sets of primers specific to the 5′ and 3′ Piggybac inverted tandem repeats (ITRs) (iPCR 5′ F & R and iPCR 3′ F & R), before sequencing using a commercial short read service (Eurofins). Mutations in the GFP coding region were amplified using primers for GFP (GFPF and GFPR) and sequenced using a commercial short read service (Eurofins). All primers all listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Raw data were generated at the University of Exeter Sequencing service and the University of Exeter Bioimaging Facility. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors on request.

References

Asai, M., Li, Y., Newton, S. M., Robertson, B. D. & Langford, P. R. Galleria mellonella—intracellular bacteria pathogen infection models: the ins and outs. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 47, fuad011 (2023).

Ménard, G., Rouillon, A., Cattoir, V. & Donnio, P. Y. Galleria mellonella as a suitable model of bacterial infection: past, present and future. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 11, 782733 (2021).

Giammarino, A., Bellucci, N. & Angiolella, L. Galleria mellonella as a model for the study of fungal pathogens: advantages and disadvantages. Pathogens 13, 233 (2024).

Piatek, M., Sheehan, G. & Kavanagh, K. Galleria mellonella: the versatile host for drug discovery, in vivo toxicity testing and characterising host–pathogen interactions. Antibiotics 10, 1545 (2021).

Kavanagh, K. & Fallon, J. P. Galleria mellonella larvae as models for studying fungal virulence. Fungal Biol. Rev. 24, 79–83 (2010).

Smith, D. F. Q. & Casadevall, A. Fungal immunity and pathogenesis in mammals versus the invertebrate model organism Galleria mellonella. Pathog. Dis. 79, ftab013 (2021).

Pereira, T. C. et al. Recent advances in the use of Galleria mellonella model to study immune responses against human pathogens. J. Fungi 4, 128 (2018).

Trevijano-Contador, N. & Zaragoza, O. Immune response of Galleria mellonella against human fungal pathogens. J. Fungi 5(1), 3 (2019).

Freitas, M. S. et al. Aspergillus fumigatus extracellular vesicles display increased galleria mellonella survival but partial pro-inflammatory response by macrophages. J. Fungi 9, 541 (2023).

Kavanagh, K. & Sheehan, G. The use of Galleria mellonella larvae to identify novel antimicrobial agents against fungal species of medical interest. J. Fungi 4, 113 (2018).

Tsai, C. J., Loh, J. M. & Proft, T. Galleria mellonella infection models for the study of bacterial diseases and for antimicrobial drug testing. Virulence 7, 214–229 (2016).

Bombelli, P., Howe, C. J. & Bertocchini, F. Polyethylene bio-degradation by caterpillars of the wax moth Galleria mellonella. Curr. Biol. 27, R292–R293 (2017).

Kong, H. G. et al. The Galleria mellonella hologenome supports microbiota-independent metabolism of long-chain hydrocarbon beeswax. Cell Rep. 26, 2451–2464 (2019).

Sanluis-Verdes, A. et al. Wax worm saliva and the enzymes therein are the key to polyethylene degradation by Galleria mellonella. Nat. Commun. 13, 5568 (2022).

Spínola-Amilibia, M. et al. Plastic degradation by insect hexamerins: near-atomic resolution structures of the polyethylene-degrading proteins from the wax worm saliva. Sci. Adv. 9, 38 (2023).

Lange, A. et al. Genome sequence of Galleria mellonella (greater wax moth). Genome Announc. 6, e01220-17 (2018).

Young, R. et al. Improved reference quality genome sequence of the plastic-degrading greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella. G3 14, jkae070 (2024).

Sterling, M. J., Barclay, M. V. L. & Lees, D. C. The genome sequence of the greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella Linnaeus, 1758. Wellcome Open Res. 9, 101 (2024).

Vogel, H., Altincicek, B., Glöckner, G. & Vilcinskas, A. A comprehensive transcriptome and immune-gene repertoire of the lepidopteran model host Galleria mellonella. BMC Genomics 12, 308 (2011).

Sheehan, G., Margalit, A., Sheehan, D. & Kavanagh, K. Proteomic profiling of bacterial and fungal induced immune priming in Galleria mellonella larvae. J. Insect Physiol. 131, 104213 (2021).

Sheehan, G. & Kavanagh, K. Proteomic analysis of the responses of Candida albicans during infection of Galleria mellonella larvae. J. Fungi 5, 7 (2019).

Sheehan, G. et al. Proteomic analysis of the processes leading to Madurella mycetomatis grain formation in Galleria mellonella larvae. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 14, 1–23 (2020).

Sheehan, G., Clarke, G. & Kavanagh, K. Characterisation of the cellular and proteomic response of Galleria mellonella larvae to the development of invasive aspergillosis. BMC Microbiol. 18, 63 (2018).

Asai, M. et al. Innate immune responses of Galleria mellonella to Mycobacterium bovis BCG challenge identified using proteomic and molecular approaches. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 11, 619981 (2021).

Zhao, H. X. et al. Candidate chemosensory genes identified from the greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella, through a transcriptomic analysis. Sci. Rep. 9, 10032 (2019).

Peydaei, A., Bagheri, H., Gurevich, L., de Jonge, N. & Nielsen, J. L. Impact of polyethylene on salivary glands proteome in Galleria melonella. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. D 34, 100678 (2020).

Campbell, J. S. et al. Characterising phagocytes and measuring phagocytosis from live Galleria mellonella larvae. Virulence 15, 2313413 (2024).

Moth, E., Messer, F., Chaudhary, S. & White-Cooper, H. Differential gene expression underpinning the production of distinct sperm morphs in the wax moth Galleria mellonella. Open Biol. https://doi.org/10.1098/RSOB.240002 (2024).

Cary, L. C. et al. Transposon mutagenesis of baculoviruses: analysis of Trichoplusia ni transposon IFP2 insertions within the FP-locus of nuclear polyhedrosis viruses. Virology 172, 156–169 (1989).

Yusa, K. PiggyBac transposons. Bioengineered 4, 181 (2013).

Woodard, L. E. & Wilson, M. H. piggyBac-ing models and new therapeutic strategies. Trends Biotechnol. 33, 525–533 (2015).

Li, R., Zhuang, Y., Han, M., Xu, T. & Wu, X. PiggyBac as a high-capacity transgenesis and gene-therapy vector in human cells and mice. Dis. Models Mech. 6, 828–833 (2013).

Gregory, M., Alphey, L., Morrison, N. I. & Shimeld, S. M. Insect transformation with piggyBac: getting the number of injections just right. Insect Mol. Biol. 25, 259–271 (2016).

Gaj, T., Gersbach, C. A. & Barbas, C. F. ZFN, TALEN and CRISPR/Cas-based methods for genome engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 31, 397 (2013).

Zhang, S., Chen, H. & Wang, J. Generate TALE/TALEN as easily and rapidly as generating CRISPR. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 13, 310 (2019).

Cui, Z. et al. The comparison of ZFNs, TALENs, and SpCas9 by GUIDE-seq in HPV-targeted gene therapy. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 26, 1466 (2021).

Jinek, M. et al. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337, 816–821 (2012). 1979.

Wiedenheft, B., Sternberg, S. H. & Doudna, J. A. RNA-guided genetic silencing systems in bacteria and archaea. Nature 482, 331–338 (2012).

Makarova, K. S. et al. Evolutionary classification of CRISPR–Cas systems: a burst of class 2 and derived variants. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 18, 67–83 (2019).

Ran, F. A. et al. Genome engineering using the CRISPR–Cas9 system. Nat. Protoc. 8, 2281–2308 (2013).

Pearce, J et al. A microinjection protocol for the greater waxworm moth, Galleria mellonella. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.09.17.613528 (2025).

Tsubota, T. et al. Identification of a novel strong and ubiquitous promoter/enhancer in the silkworm Bombyx mori. G3 4, 1347–1357 (2014).

Eckermann, K. N. et al. Hyperactive piggyBac transposase improves transformation efficiency in diverse insect species. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 98, 16–24 (2018).

Jao, L. E., Wente, S. R. & Chen, W. Efficient multiplex biallelic zebrafish genome editing using a CRISPR nuclease system. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 13904–13909 (2013).

Tamura, T., Kuwabara, N., Uchino, K., Kobayashi, I. & Kanda, T. An improved DNA injection method for silkworm eggs drastically increases the efficiency of producing transgenic silkworms. J. Insect Biotechnol. Sericol. 76, 3155–3159 (2007).

Heryanto, C., Mazo-Vargas, A. & Martin, A. Efficient hyperactive piggyBac transgenesis in Plodia pantry moths. Front. Genome Ed. 4, 1074888 (2022).

Nakao, H., Matsumoto, Ã. T., Oba, Y., Niimi, T. & Yaginuma, T. Germ cell specification and early embryonic patterning in Bombyx mori as revealed by nanos orthologues. Evol. Dev. 554, 546–554 (2008).

Grizanova, E. V., Coates, C. J., Butt, T. M. & Dubovskiy, I. M. RNAi-mediated suppression of insect metalloprotease inhibitor (IMPI) enhances Galleria mellonella susceptibility to fungal infection. Dev. Comp. Immunol. 122, 104126 (2021).

Dutta, T. K. et al. RNAi-mediated knockdown of gut receptor-like genes prohibitin and α-amylase altered the susceptibility of Galleria mellonella to Cry1AcF toxin. BMC Genomics 23, 601 (2022).

Terenius, O. et al. RNA interference in Lepidoptera: an overview of successful and unsuccessful studies and implications for experimental design. J. Insect Physiol. 57, 231–245 (2011).

Guan, R. B. et al. A nuclease specific to lepidopteran insects suppresses RNAi. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 6011 (2018).

Peng, Y. et al. Identification and characterization of multiple dsRNases from a lepidopteran insect, the tobacco cutworm, Spodoptera litura (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 162, 86–95 (2020).

Jorjão, A. L. et al. From moths to caterpillars: ideal conditions for Galleria mellonella rearing for in vivo microbiological studies. Virulence https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2017.1397871 (2017).

Tamura, T. et al. Germline transformation of the silkworm Bombyx mori L. using a piggyBac transposon-derived vector. Nat. Biotechnol. 18, 81–84 (2000).

Burger, A. et al. Maximizing mutagenesis with solubilized CRISPR–Cas9 ribonucleoprotein complexes. Development 143, 2025–2037 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We thank I. Canada Luna for his help in maintenance of the GMRC G. mellonella laboratory colony and for stimulating discussions. We also thank the Mosimann and Bopp labs of University of Colorado Anschutz medical campus and Universität Zürich, respectively, for their training in CRISPR–Cas9 methodologies, and O. Champion for coconceptualizing the generation of transgenic Galleria. This work was funded by a PhD studentship jointly funded between the University of Exeter and Dstl (J.C.P.), an NC3Rs Project Grant awarded to J.G.W. (NC/T001518/1), which supported J.S.C., and an NC3R Training Fellowship, awarded to J.C.P. (NC/W002388/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C.P.—conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, project administration, writing and funding acquisition (review and editing). J.S.C.—methodology, investigation and writing (editing). J.L.P.—supervision, writing (editing), funding acquisition. R.W.T.—conceptualization, resources, supervision, writing (editing). J.G.W.—conceptualization, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing (review and editing), funding acquisition.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Lab Animal thanks Daniel Brady, Yasuhiko Matsumoto and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figs. 1–9 and Table 1.

Supplementary Data 1

ARRIVE guidelines.

Supplementary Dataset 1

pHA3PIG.

Supplementary Dataset 2

pBmhsp90:hyPBase.

Supplementary Dataset 3

pBmhsp90:GFP/3xP3:DsRed.

Supplementary Dataset 4

pGmhsp90:GFP.

Supplementary Dataset 5

pGmhsp90:GFP-αtub1b.

Supplementary Dataset 6

pBmhsp90:histone2av-mCh/3xP3:DsRed.

Supplementary Dataset 7

Bmhsp90:GFP/3xP3:DsRed transposon insertion chr12 sequence.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pearce, J.C., Campbell, J.S., Prior, J.L. et al. PiggyBac-mediated transgenesis and CRISPR–Cas9 knockout in the greater wax moth, Galleria mellonella. Lab Anim (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41684-025-01665-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41684-025-01665-7