Abstract

Anal squamous cell carcinoma (aSCC) is a rare, predominantly HPV-driven cancer with limited treatment options. This study aimed to define its genomic landscape, identify actionable targets (AT), and highlight the clinical value of molecular profiling—especially liquid biopsy (LB)—based on Gustave Roussy’s (GR) experience. In this retrospective analysis, 1844 patients from the U.S. and France underwent tissue biopsy (TB, n = 1733) and/or LB (n = 140), analyzed using the FoundationOne®CDx or FoundationOne® Liquid CDx assays both comprehensive genomic profiling assays for solid tumors covering ~324 genes. Twenty-nine patients had paired TB/LB, and 44 LB patients formed the clinically annotated GR subgroup. HPV was detected in 86.6% of cases, predominantly HPV-16 (75.6%). High tumor mutational burden (≥10 mut/Mb) was found in 17.1% of patients; microsatellite instability was rare (1.7%). Frequent mutations included PIK3CA (34.5%), KMT2D (18.0%), PTEN (13.1%), FBXW7 (12.9%), and TP53 (12.0%). ATs were identified in BRCA1/2, FGFR2/3, EGFR, KRAS, BRAF, and NRAS. Mutation patterns varied by HPV subtype. LB showed high concordance with TB, including HPV detection. At GR, LB informed treatment decisions in 18.2% of cases. Four clinical examples illustrated LB-guided therapies. This largest-to-date aSCC cohort reinforces molecular profiling—especially LB—as a key tool for guiding personalized therapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anal cancer is a rare malignancy, that accounts for less than 3% of all digestive cancers1. Although relatively uncommon, its incidence and mortality are rising, with global projections estimating 65,500 new cases and 26,900 deaths by 20302.

Anal squamous cell carcinoma (aSCC) is the predominant subtype, with 80–85% of cases linked to Human Papillomavirus Virus (HPV) infection, particularly HPV types 16 and 183.

Despite the availability of HPV vaccines, their impact on aSCC incidence remains limited, likely due to the slow global implementation of vaccination programs, poor adherence to vaccination recommendations, and exceptionally low vaccine coverage in the male population (only 4% in 2019)4,5,6.

Although chemoradiotherapy is effective in treating anal cancer, 10–40% of patients will experience a relapse. Of those, only about 20% are eligible for salvage therapy, while the remainder will receive systemic treatment as for metastatic disease7. Additionally, approximately 10–20% of patients either present with metastatic disease or develop distant relapses, both of which are associated with a poor prognosis and a 5-year survival rate of just 36%8. For many years, palliative chemotherapy has been the primary treatment option, with limited evidence from retrospective studies8. However, the “InterAAct” phase 2 trial established the paclitaxel-carboplatin regimen as the standard first-line therapy for locally advanced or metastatic aSCC9. More recently, two phase 3 trials—POD1UM-303/InterAACT-210 and ECOG-ACRIN 217611—investigated the combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) with chemotherapy as first-line treatment, showing promising results12, though final OS data are still pending. In the second line setting, many patients remain eligible for further treatment13, but options are still limited, with most recommendations derived from small retrospective studies. Common regimens, such as mitomycin C plus 5-FU, irinotecan, cetuximab, or taxanes, offer modest PFS benefits of 3-5 months14. According to NCCN and ESMO guidelines, ICIs could be considered in the second or third line for patients not exposed to them in the first line. However, their availability in daily practice remains limited in most cases3,15.

Recent advances in cancer genomic profiling have identified potential biomarkers, such as PD-L1 expression and tumor mutational burden (TMB), which may predict the efficacy of ICIs in aSCC16. Although precision medicine has yet to significantly impact aSCC owing to its rarity, there is a growing need for studies that explore molecular alterations to enable more personalized treatment strategies3,15.

The largest published study on aSCC included 311 patients17. When combined with smaller studies, it may be possible to estimate genetic alterations in only a few hundred patients profiled exclusively using tissue samples. However, the use of different platforms across studies complicates the data aggregation and analysis. Overall, these studies identified PIK3CA as the most frequently mutated gene, followed by FBXW7 and KMT2D in HPV-positive cases, and CDKN2A and TP53 in HPV-negative cases.

The objective of this study was to investigate the molecular characteristics of aSCC using tissue and liquid biopsies from a large cohort of 1844 patients. Specifically, we evaluated the role of molecular profiling, including cell-free DNA (cfDNA), in guiding treatment decisions. As the largest cohort of aSCC patients studied to date, our findings will help pave the way for precision medicine for this challenging and rare cancer.

Results

Clinical characteristics of the overall cohort

The overall cohort comprised 1844 patients with histologically confirmed aSCC. Of these, 1733 patients underwent tissue profiling, while 140 underwent liquid profiling. Among the 1844 patients, 29 were analyzed using both profiling methods. Additionally, among the 140 patients who underwent liquid profiling, 44 were from Gustave Roussy, constituting the clinically annotated cohort (Fig. 1A).

A Schematic representation of the entire cohort. A total of 1844 patients were included in the study. Of these, 1733 patients underwent tissue biopsy analysis, forming the tissue biopsy cohort. Additionally, 140 patients had liquid biopsy analysis, making up the liquid biopsy cohort. For 29 patients, both tissue and liquid biopsies were available. Finally, 44 patients with liquid biopsy data, who were treated at Gustave Roussy, constituted the clinical cohort. This figure was created with BioRender.com. B Sunburst chart depicting the organ of origin for the analyzed tissue samples. C Pie chart showing the distribution of the different HPV genotypes. D Bar plot showing the distribution of males and females based on HPV status and genotype.

The tissue biopsy cohort consisted of 1733 patients, with a median age of 61 years (IQR: 54–69). Among them, 1201 patients (69.3%) were female (Supplementary Table 2). Of the 1733 tissue samples, 734 (42.4%) were from localized tumors and 858 (49.5%) were from metastatic sites, with 141 (8.1%) having an unclear origin. Among the 858 patients with metastases profiled, the liver was the most common metastatic site (325 patients, 37.9%) as described previously18, followed by lymph nodes (218 patients, 25.4%), lungs (113 patients, 13.2%), skin (41 patients, 4.8%), pelvis (38 patients, 4.4%), vagina (21 patients, 2.4%), bone (12 patients, 1.4%), and other sites (90 patients, 10.5%) (Fig. 1B).

Of the 1733 patients with tissue specimens, 1500 (86.6%) were HPV-positive, similar to the findings of a meta-analysis19. As expected, HPV-16 was the most common subtype (1315 patients, 75.9%), followed by HPV-18 (62 patients, 3.6%), HPV-45 (22 patients, 1.3%), and HPV-33 (21 patients, 1.2%) (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Table 3). Low-risk HPV-6, which is not commonly associated with the development of aSCC, was identified in 33 patients (1.9%). HPV status varied significantly between males and females. Of the 532 males, 400 (75.2%) were HPV-positive, compared to 1100 (91.6%) of 1201 females (p < 0.001). HPV-16 was more prevalent in females (986, 82.1%) than males (329, 61.8%) (p < 0.001). Conversely, HPV-45 and HPV-6 were more common in males: 12 males (3.0%) tested HPV-45 positive, compared to 10 females (0.9%) (p = 0.004), and 21 males (5.3%) tested HPV-6 positive, compared to 12 females (1.0%) (p < 0.001). No significant sex differences were observed for the other HPV types (Fig. 1D and Supplementary Table 4).

The liquid biopsy cohort included 140 patients, with a median age of 63 years (IQR: 55–69). Of these, 95 (67.9%) were female (Supplementary Table 2).

From the liquid biopsy cohort, 44 patients with histologically confirmed aSCC at Gustave Roussy formed the clinical cohort. The median age at diagnosis was 58 years (IQR: 54–63), with 29 (65.9%) being female. Of these, 40 (90.9%) had locally advanced or metastatic disease. The most common metastatic sites were lymph nodes (29 patients, 65.9%), liver (21 patients, 47.7%), and lungs (15 patients, 34.1%). The median overall survival (mOS) from diagnosis was 32.0 months (95% CI: 21.8–42.2 months). Patients received a median of one line of therapy (range, 0–7) before genomic profiling.

Genomic landscape of the aSCC tissue cohort

Out of the 1733 patients with tissue samples analyzed, 1620 (93.5%) had at least one molecular alteration. The median TMB was 4.8 mutations per megabase (mut/Mb), with 296 patients (17.1%) exhibiting a high TMB (≥10 mut/Mb). However, as previously described20 no association was observed between high TMB and high MSI, as only 28 patients (1.7%) were MSI-high, and 96 patients (5.5%) had unknown MSI status. The majority, 1609 patients (92.8%), were microsatellite stable (Fig. 2A).

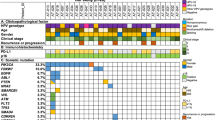

A Oncoplot showing the distribution of the 12 most frequently altered genes in aSCC within the tissue biopsy cohort. Genes and their corresponding frequencies are listed on the left. HPV subtype (HPV), tumor mutational burden (TMB), and microsatellite instability status (MSI) are overlaid for each patient. Each sample is color-coded based on the type of gene alteration detected. B Pie chart illustrating the distribution of the 705 PIK3CA alterations identified in the tissue biopsy cohort. C Prevalence of chromosomal copy number losses (light blue) and gains (yellow) in aSCC within the tissue biopsy cohort. Key genes are indicated for select chromosome arms. D Heatmap showing the correlation between HPV status and molecular alterations in the tissue biopsy cohort. Intense red indicates a correlation observed in more than 50% of the samples, while dark blue represents a correlation close to 0%.

As expected21, PIK3CA was the most altered gene, affecting 34.5% of the patients. Of the 705 PIK3CA alterations, SNVs in exon 10 were most common, with E545K and E542K in the helical domain representing 37.9% and 18.6% of the alterations, respectively. PIK3CA amplifications accounted for 18.9% of alterations. Other rarer alterations, including E726K, H1047R, E543K, E545Q, E81K, C420R, and M1043I, accounted for 12.3% of PIK3CA alterations (Fig. 2B).

Epigenetic modifiers such as KMT2D and EP300 were altered in 18.0% and 7.2% of the patients, respectively. Tumor suppressor genes like PTEN, FBXW7, TP53, and CDKN2A were also frequently altered. PTEN and CDKN2A were inactivated in 13.1% and 6.9% of the patients, respectively, mainly due to homozygous deletions in 53.7% and 48.7% of the cases. FBXW7 was altered in 12.9% of patients, primarily by missense variants (96.9%). TP53 alterations were seen in 12.0% of patients, while TERT promoter alterations were found in 7.3% of patients (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Fig. 1, and Supplementary Table 5).

At the chromosome level, the most common alteration was the gain of chromosome arm 3q, affecting 67.2% of patients, containing genes like PIK3CA, SOX2, FGF12, TERC, and PRKCI. This was followed by gains in arms 8q (41.3%), 1q (32.4%), and 5p (29.4%), containing TERT. The most frequent chromosomal loss occurred in arm 11q (49.6%), followed by losses in arms 3p (39.4%), 16q (28.2%), 4p (26.8%), 8p (26.1%), and 17p (21.3%), which contains TP53 (Fig. 2C and Supplementary Table 6).

Notably, after false discovery rate correction, no specific features (molecular or clinical) were enriched in metastatic disease compared to local biopsies (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Variations in pathogenic alterations in HPV-positive and HPV-negative tissue aSCC cases

The frequency of pathogenic alterations in aSCC differed between HPV-negative and HPV-positive cases. Among the 233 HPV-negative cases, 229 (98.3%) had at least one alteration, a higher proportion than the 92.7% (1391 out of 1,500) of HPV-positive cases (p = 0.002) (Supplementary Table 7).

The altered genes also varied significantly between HPV-positive and HPV-negative cases, and across HPV genotypes (Fig. 2D). Notably, HPV-negative and HPV-6-positive cases had more frequent alterations in TP53, TERT promoter, and CDKN2A compared to other genotypes. The most common HPV genotype, HPV-16, exhibited a distinct mutational profile, with a high prevalence of PIK3CA alterations, detected in 39.0% of patients. These alterations were less common in other HPV genotypes and HPV-negative cases (Supplementary Table 8).

Among rarer HPV subtypes, 22 HPV-45-associated aSCC patients had frequent alterations in PIK3CA, STK11, and FBXW7 (13.6%, 13.6%, and 9.1%, respectively). In 21 HPV-33-associated aSCC cases, PIK3CA, FBXW7, and PTEN were most commonly mutated (23.8%, 23.8%, and 19.0%, respectively). These rarer HPV subtypes showed a mutational profile more similar to HPV-16 than to HPV-negative or HPV-6-associated cases, supporting their classification as high-risk subtypes.

Novel recurrent potentially actionable events in a tissue aSCC cohort

We identified targetable alterations in additional genes. While each gene was altered in less than 10% of the patients when considered individually, together they represented a significant proportion of the total cases. These genes included known tyrosine kinase receptors (Fig. 3A), effectors of intracellular signaling (Fig. 3B), and proteins implicated in DNA repair (Fig. 3C).

Pie chart and lollipop plot illustrating the distribution of alterations in potentially actionable genes identified within the tissue biopsy cohort. Part of this figure was created with BioRender.com. A Alterations occurring in tyrosine kinase receptors. B Alterations occurring in effectors of intracellular signaling. C Alterations occurring in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 genes.

Among the 1733 patients, FGFR3 alterations were found in 63 (3.6%), with 10 patients (15.9%) harboring FGFR3 rearrangements, TACC3 being the primary fusion partner in eight cases. In 52 cases (82.5%), FGFR3 mutations were detected, affecting 11 amino acids. Consistent with previous reports in other cancer types22, the most prevalent mutation was FGFR3 S249C, identified in 33 patients (52.4%), promoting ligand-independent dimerization and increasing the basal phosphorylation of the receptor23. The second most frequent mutation, R248C, was present in 10 patients (15.9%) and also drives receptor dimerization and ligand-independent phosphorylation24. Other mutations identified in the cohort included: G370C, Y373C, G380R, K650E, and K650N. Additionally, three different mutations (9.1%) in the stop codon extended the open reading frame by 101 amino acids, a known pathogenic alteration in thanatophoric dysplasia25, potentially actionable in aSCC. Finally, one FGFR3 amplification was observed.

FGFR2 was altered in nine patients (0.5%), including two amplifications and various missense mutations, including S252W, S320C, N549K, V564L, and K659N. Additionally, a Q778* truncating mutation in the last exon was observed. This mutation, causing the transcription of a truncated FGFR2 protein, should be considered actionable26.

EGFR alterations occurred in 43 patients (2.5%), with amplifications in 25 cases (58.1%). Additionally, 15 patients (34.9%) had missense mutations, each affecting a different residue: E114K, A289T, T415M, S492R, G598V, S645C, L703V, E709_T710 > F, V742I, V765M, V769M, D770H, V774M, T790M, and R831H. Additionally, three patients harbored EGFR rearrangements (7.0%). These findings confirm that EGFR amplifications can be assessed using NGS, alongside fluorescence in situ hybridization27.

Members of the MAPK pathway were also recurrently altered (Fig. 3B). For instance, KRAS alterations were identified in 41 patients (2.4%). Among these, 38 patients (92.7%) had missense mutations, while three others (7.3%) exhibited amplifications. Specifically, 12 patients (29.3%) harbored G12D mutations, four patients had either G12V or G13D mutations (9.8% each), and three patients presented with G12C or G12A mutations (7.3% each).

Similarly, 12 NRAS mutations were identified (0.7%), with the most common being Q61K in three patients (25.0%). G12D and Q61R mutations were each found in two patients (16.7%).

BRAF alterations were observed in 18 patients (1.0%). Based on a previously published classification28, a class I V600E alteration was identified in one patient (5.6%). Class II alterations were found in six patients (33.3%), including G469A, G464V, G464R mutations, and a BRAF fusion. Lastly, class III alterations, such as D594N, D594G, and G466E, were observed in four patients (22.2%).

Besides PIK3CA and PTEN, AKT1, another member of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, was altered in 35 patients (2.0%), mainly by the missense mutation E17K observed in 23 patients (65.7%), further emphasizing the critical role of this pathway, as demonstrated by previous studies21.

Recurrent alterations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes were notably identified (Fig. 3C). Pathogenic BRCA1 alterations were found in 53 patients (3.1%). Among them, 18 patients (34.0%) had a nonsense mutation, 14 (26.4%) had a rearrangement, 10 (18.9%) had a frameshift mutation, six (11.3%) had a splice site mutation, three (5.7%) had a missense mutation, and two (3.8%) had a homozygous deletion. Germline origin was suspected in seven patients (13.2%). BRCA2 alterations were found in 45 patients (2.6%). Of these, 20 had frameshift mutations (44.4%), 15 had nonsense mutations (33.3%), four had missense mutations (8.9%), three had splice site mutations (6.7%), and one patient each exhibited a rearrangement, an in-frame deletion, or a homozygous deletion. Germline origin was suspected in 10 patients (22.2%).

Actionality of molecular targets identified in tissue samples using ESCAT and OncoKB

We categorized the molecular alterations using an adapted ESCAT classification and OncoKB. Of the 2120 alterations identified in tissue samples, 407 (19.2%) were ESCAT 1C, 960 (45.3%) ESCAT 3A, 139 (6.6%) ESCAT 3B, and 614 (29.0%) ESCAT 4. Of note, ESCAT 1 C alterations represent alterations whose clinical inhibition should be considered standard of care based on evidence generated in basket trials, regardless of the tissue of origin. These included, among others, TMB-high, MSI-high, and mutations in FGFR2/3 or BRAF V600E (Fig. 4A). According to OncoKB, 320 (15.1%) alterations were classified as Level 1, 32 (1.5%) as Level 3A, 595 (28.1%) as Level 3B, and 1173 (55.3%) as Level 4 (Supplementary Table 9). The most prevalent alterations were PIK3CA E545K, PIK3CA E542K, TP53, PTEN, and TMB-high (Fig. 4B).

Liquid biopsy reveals concordant genomic alterations, actionable targets, and HPV detection in aSCC patients

After excluding genes associated with clonal hematopoiesis—such as ASXL1, ATM, CHEK2, DNMT3A, TET2, JAK2, MPL, U2AF1, and SF3B1—molecular profiling of 140 plasma samples revealed results consistent with tissue samples. PIK3CA mutations were found in 35.0% of liquid samples vs 34.5% of tissue samples (p = 0.98), and FBXW7 mutations were present in 12.9% of both (p = 1). However, TP53 mutations were significantly more frequent in liquid biopsies (35.7% vs 12.0%, p < 0.001), likely due to TP53’s involvement in clonal hematopoiesis29,30. Liquid biopsies also showed higher mutation rates for KMT2D (30.0% vs 18.0%, p < 0.001) and PTEN (30.0% vs 13.1%, p < 0.001), potentially due to better detection of subclonal mutations (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 10).

As previously reported by our group31 copy number alterations were less frequently detected in plasma, likely influenced by the level of ctDNA shedding. Specifically, there were fewer gains observed in FGF12 (3.6% vs 8.1%, p = 0.0479), SOX2 (1.4% vs 8.9%, p = 0.002), TERC (0% vs 7.8%, p < 0.001), and PRKCI (1.4% vs 7.2%, p = 0.009). Fewer homozygous deletions were found for CDKN2A in plasma (1.4% vs 6.9%, p = 0.01283) (Fig. 5A).

A Butterfly chart depicting the prevalence of the 11 most frequently altered genes in the tissue biopsy cohort (orange) and the liquid biopsy cohort (dark blue). B Pie chart showing the proportion of the different ESCAT types among the 263 alterations identified. C Bar plot showing the prevalence of the 25 most common alterations classified according to the ESCAT classification. D Heatmap showing the correlation between HPV status and molecular alterations in the liquid biopsy cohort. Intense red indicates a correlation observed in more than 50% of the samples, while dark blue represents a correlation close to 0%. E Heatmap illustrating the concordance of the 12 most frequently altered genes in the 29 patients with both tissue and liquid biopsy samples. Orange squares indicate alterations found in both liquid and tissue biopsies, light blue squares represent alterations identified only in the liquid biopsy, and dark blue squares represent alterations exclusive to the tissue biopsy.

Two hundred sixty-three actionable alterations were found in liquid biopsies. These included 50 (19.0%) ESCAT 1C, 104 (39.5%) ESCAT 3A, 19 (7.2%) ESCAT 3B, and 90 (34.2%) ESCAT 4. No significant differences were observed in actionable targets between liquid and tissue biopsies. Using the OncoKB scale, 47 (17.9%) alterations were Level 1, 8 (3.0%) Level 3A, 65 (24.7%) Level 3B, and 143 (54.4%) Level 4 (Supplementary Table 11). Similarly, no significant differences were observed compared to tissue analysis (Fig. 5B). The most recurrent actionable alterations included PIK3CA E545K, PIK3CA E542K, TMB-high, and PTEN (Fig. 5C). Targetable alterations in tyrosine kinase receptors, effectors of intracellular signaling, and proteins implicated in DNA were found as well.

Liquid biopsy not only enables the detection of genomic alterations in a manner concordant with tissue analysis but also allows for the detection of HPV reads. In line with findings from tissue samples, 44.8% of patients with HPV-negative aSCC harbored a TP53 alteration, while 48.4% of those with HPV-16-positive aSCC harbored a PIK3CA alteration. These liquid biopsy results closely mirrored those from tissue analysis, where TP53 alterations were found in 53.2% of HPV-negative aSCC cases, and PIK3CA alterations were observed in 39.0% of HPV-16-positive aSCC cases (Fig. 5D).

For 29 patients with both tissue and liquid biopsies, 33 alterations were identified in the 12 most frequently altered genes. Of these, 15 (45.4%) were unique to liquid samples, potentially linked to clonal hematopoiesis in the case of TP53 variants. Clonal hematopoiesis refers to the age-related expansion of hematopoietic stem cell clones that acquire somatic mutations, often in genes like TP53, without evidence of hematologic malignancy. These mutations can be detected in cfDNA and may not reflect tumor-derived alterations, potentially confounding interpretation of liquid biopsy results32. Twelve alterations (36.4%) were concordant between tissue and liquid, and six (18.2%) were unique to tissue. Liquid biopsy provided unique molecular information for nine patients (31.0%) with no informative tissue results (Fig. 5E).

Real-world utility of molecular profiling on liquid biopsy in aSCC

The clinically annotated cohort comprised 44 patients with aSCC who were treated at Gustave Roussy, all of whom had at least one liquid biopsy analyzed. An actionable genetic aberration was identified in 24 patients (54.5%). Based on these findings, the molecular tumor board (MTB) recommended a matched therapy for 17 patients (38.6%). For 7 patients (15.9%), no therapeutic guidance was provided by the MTB, despite the presence of an actionable target, primarily due to the lack of available clinical trials targeting those specific alterations at the time. A total of 8 patients (18.2%) received ctDNA-matched therapy, with 7 of them enrolled in clinical trials and 1 receiving compassionate use treatment. In terms of treatment response, 1 patient (12.5%) experienced a partial response, 4 patients (50.0%) had stable disease, and 3 patients (37.5%) showed progressive disease (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 12).

Through the presentation of four clinical cases of patients treated at Gustave Roussy using molecular profiling, we highlight the clinical utility of this approach, particularly in the context of liquid biopsy. A more detailed description of these cases can be found in the Supplementary Data and Supplementary Fig. 5.

Case 1 (Fig. 6A) (Supplementary Fig. 5A–C): a female patient in her 60 s had been under our care for aSCC since 2009. After experiencing multiple lymph node relapses 96 months later, the patient underwent local treatments and chemotherapy for 48 months. Molecular profiling from a liquid biopsy revealed a bTMB of 15 mut/Mb, along with KIT K558N and two PIK3CA mutations (E726K and E542K). Given her high bTMB, she enrolled in a clinical trial for anti-PD-L1 and anti-CTLA-4 therapies. After completing 23 months of treatment, she achieved a partial response with a 72% reduction in tumor size according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST), a standardized method for objectively assessing changes in tumor size in adult and pediatric solid tumor clinical trials33. According to the immune-related Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (iRECIST)34, the reduction was 92%. She also demonstrated a partial metabolic response and remains disease-free.

A Case 1—High TMB & immunotherapy. Liquid biopsy in May 2021 revealed high TMB (15 mut/Mb) together with KIT, PIK3CA, CDK12, DNMT3A, KMT2D, and TP53 alterations after prior chemotherapy. The patient was enrolled in a trial of anti-PD1 plus anti-CTLA4 with inguinal radiotherapy, achieving a durable partial response and no detectable disease on the latest PET scan. B Case 2—RAD51C mutation & PARP inhibition. Liquid biopsy in July 2021 identified a RAD51C A354fs*34 mutation (high VAF) along with EGFR, KMT2D, NFE2L2, and PBRM1 alterations. The patient was treated in a trial combining anti-PD1 therapy with a PARP inhibitor, achieving a transient partial response before subsequent radiological progression. C Case 3—FGFR2 K659N & FGFR inhibitor. Following multiple metastatic relapses after chemoradiotherapy and systemic treatment, liquid biopsy in June 2023 detected FGFR2 K659N as well as NF1, PTEN, TP53, DNMT3A, FGF6, KMT2D, and NBN mutations. The patient initiated FGFR-targeted therapy in a clinical trial, with early disease stability followed by progression. D Case 4—PIK3CA E453K & PI3K pathway inhibition. After recurrent metastatic progression despite multiple systemic treatments and surgery, liquid biopsy in May 2024 revealed PIK3CA E453K together with TP53 E294* and BCL2L1 amplification. The patient was enrolled in a PIK3CA-inhibitor clinical trial, showing stable disease on first follow-up CT imaging.

Case 2 (Fig. 6B) (Supplementary Fig. 5D–G): a 59-year-old female with no cancer history was referred to our hospital in January 2021 for progressive liver relapse from aSCC. Molecular profiling on liquid biopsy revealed a germline RAD51C A354fs*34 mutation, EGFR V765M mutation, and a bTMB of 9 mut/Mb. Based on the RAD51C mutation, she was enrolled in a clinical trial with PARP inhibitors and ICIs, achieving six months of PFS and stable disease (−21%).

Case 3 (Fig. 6C) (Supplementary Fig. 5H, I): a 62-year-old female diagnosed with locally advanced aSCC in 2019 initially received chemoradiotherapy. After four months, the patient developed a distant lymph node relapse and underwent chemotherapy. After disease progression, molecular profiling on liquid biopsy identified a FGFR2 K659N mutation, leading to enrollment in a phase 1 clinical trial for an FGFR inhibitor (FGFRi). Unfortunately, stable disease (SD) was the best objective response, and a PFS of four months was achieved with the FGFRi, labeling the disease as primary resistant. The co-occurrence of NF1 and PTEN mutations, detected in the same sample documenting the FGFR2 alteration, was likely in cause of the lack of response and short PFS.

Case 4 (Fig. 6D and Supplementary Fig. 5J, K): a 63-year-old female with metastatic aSCC, including lymph node and liver involvement, has been under follow-up since 2018, with multiple treatments. After declining further chemotherapy, she was referred for molecular profiling. A liquid biopsy revealed a PIK3CA E453K mutation, and she was enrolled in a PIK3CA inhibitor trial. Two months later, her CT scan showed SD, with excellent tolerance. She remains on treatment.

Discussion

In this study, we present the molecular profiling of the largest cohort of aSCC tumors to date, comprising 1844 patients. This extensive analysis provides a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the disease. We were able to explore clinical features, gender differences, and HPV status, identifying genomic alterations linked to rare HPV subtypes. We also report recurrent actionable targets, suggesting novel therapeutic opportunities. Notably, we demonstrate the clinical concordance between liquid and tissue biopsies in aSCC, highlighting liquid biopsy as a minimally invasive tool for identifying targets and predicting outcomes.

Our large cohort allowed us to further refine the clinical features of aSCC. Notably, we observed significant sex differences in HPV status, with females showing higher HPV positivity (91.6% vs 75.2%, p < 0.001). This trend is consistent with the findings of previous studies35. One possible explanation for this difference is the concurrent presence of cervical HPV infection in females, known to increase the risk of concurrent anal HPV infection by more than threefold36. Shift in sexual practices over recent decades may also contribute to these trends, with a notable rise in the prevalence of anal intercourse (performed or received) among both women and men—from 23.4% to 38.9% in women and from 29.6% in 1992 to 57.4% in men between 1992 and 202337. Delving into HPV-subtypes, we showed that HPV-45 and HPV-6 are more prevalent in males.

Over the past 10–15 years, oncology has entered a new era of precision medicine, driven by clinical trials38 improving patient prognoses and guiding new therapeutic avenues. However, aSCC’s rarity limits data on molecular alterations, and patients are often excluded from clinical trials. Our findings suggest that targetable molecular alterations are prevalent, supporting the use of targeted therapies for alterations where a drug has already shown clinical benefit in clinical trials across various tumor types (ESCAT 1C). For other recurrent ESCAT alterations, our results underscore the importance of including aSCC patients in clinical trials to evaluate the potential efficacy of these targeted therapies.

We identified 72 patients with either an FGFR2 or FGFR3 alteration. FGFRi has already shown promise in other cancers and should also benefit aSCC patients. A case report has demonstrated an excellent response to pemigatinib in an aSCC patient with FGFR1 overexpression39. Here, we report a patient who experienced SD with an FGFRi targeting an FGFR2 mutation, achieving a PFS of 4 months. We attributed this primary resistance to alterations in NF1 and PTEN, detected in the very sample that allowed the patient’s inclusion in the FGFRi clinical trial.

We also identified recurrent pathogenic DNA repair gene alterations that are associated with PARP inhibitor sensitivity in various cancers (including pancreatic, ovarian, and prostate cancers), leading to the FDA approval of these therapies40. We reported the case of a patient with a RAD51C mutation who showed six months of PFS with a PARP inhibitor, suggesting potential for PARP inhibitors in this population. Given that nearly 6% of aSCC patients have DNA repair gene alterations, further studies evaluating these drugs are needed.

As previously published17,21,41, PIK3CA alterations are among the most common in aSCC. HPV16 oncogenes and activating PIK3CA mutations contribute to the acceleration and promotion of anal carcinogenesis, suggesting that PIK3CA mutations may serve as potential therapeutic targets42. These mutations are commonly found in various solid tumors, but targeted therapies have shown the greatest success in breast cancer. Alpelisib, inavolisib, and capivasertib are now FDA-approved for the treatment of PIK3CA-mutated breast cancer43,44,45. Our description of a case of SD after treatment with a PIK3CA inhibitor provides hope for ongoing clinical trials evaluating this approach46.

We also identify recurrent alterations in the KRAS gene in 2.6% of the patients. G12C inhibitors have now been FDA-approved for NSCLC and colorectal cancer, and our findings suggest that these inhibitors should also be evaluated for aSCC47,48. Additionally, new pan-KRAS inhibitors are currently in development, and aSCC should be included in clinical trials assessing these novel therapies49.

Overall, these examples highlight the abundance of molecular targets in aSCC, underscoring the critical need to include these patients in clinical trials. However, as of the beginning of 2025, there are no clinical trials specifically focused on evaluating targeted therapies for aSCC that are currently recruiting participants.

In addition to targeted therapies, ICIs are now a therapeutic option for aSCC. High TMB has been associated with increased efficacy of ICIs in several solid tumors50, such as lung cancer and melanoma51, and given the immunogenicity of HPV, ICIs were initially thought to be effective in patients with aSCC52. Yet, clinical trial results have shown modest objective response rates, PFS, and OS, indicating that only a subset of patients respond to ICIs. Translational research from the CARACAS16 study identified a positive correlation between high TMB and improved OS and PFS, suggesting that TMB could serve as a biomarker for treatment selection. In our study, we demonstrate that 17.1% of aSCC patients exhibit high TMB (≥10 mut/Mb), potentially identifying a group that could benefit from ICIs.

Our study underscores the concordance between liquid and tissue biopsies in identifying genomic alterations in aSCC. Previously, our team demonstrated the value of ctDNA in matching patients to clinical trials within a pan-cancer cohort53. Similar findings in gastrointestinal cancer have shown that liquid biopsy significantly improves trial enrollment rates and reduces screening duration54. In our experience, liquid biopsy enabled 8 out of 44 aSCC patients (18.2%) to access a new line of treatment based on the identified molecular alterations. This study is the first to demonstrate the value of liquid biopsy in detecting genomic alterations in aSCC, providing new therapeutic options for these patients.

A limitation of our study is that it was limited to >300 genes targeted in the assays. Additionally, the absence of RNA and protein expression data limits insights into the functional implications of the identified genetic alterations. The lack of clinical data for the tissue cohort can also be considered a limitation of the study.

Another limitation of this study is the absence of detailed clinical and behavioral data, including sexual orientation, HIV status, antiretroviral therapy (ART) use, and immunosuppression. These factors are known to significantly impact the risk and progression of aSCC. HIV-positive individuals, particularly men who have sex with men (MSM), have markedly higher rates of aSCC, with adjusted rate ratios of approximately 27 for HIV-positive men and up to 80 for HIV-positive MSM compared to HIV-negative men55. While ART improves immune function and reduces high-risk HPV prevalence by 35% compared to ART-naive individuals, its impact on anal cancer incidence appears limited when adjusted for duration of HIV infection56. Additionally, HPV genotype distribution differs in HIV-positive individuals, with a lower prevalence of HPV16 (59.6% vs 76.1%) and higher prevalence of other high-risk types such as HPV18 (15.4% vs 4.3%)57. The lack of these data in our cohort limits the interpretation of the observed genotype patterns and molecular alterations. Future studies should include detailed clinical and behavioral variables to better elucidate their role in aSCC pathogenesis.

In conclusion, our findings strongly support the value of genomic profiling for aSCC using both tissue and liquid biopsies. Given the rarity of this cancer, we advocate for routine tumor profiling and the integration of clinical trial opportunities. International collaboration is essential to support and facilitate the enrollment of aSCC patients, ultimately driving progress in the field.

Methods

Solid and liquid biopsies profiling

Patients included in this retrospective work were diagnosed with aSCC.

Tumor specimens were obtained as part of routine clinical care from patients in the United States. The tissue biopsy diagnosis of aSCC was confirmed using routine hematoxylin and eosin staining, and DNA was extracted from samples with at least 20% tumor nuclei for targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) using a hybrid capture-based approach. Sequencing of all coding exons of 309 cancer-related genes plus select introns from 34 genes frequently rearranged in cancer was performed using the FoundationOne®CDx assay. Sequencing of captured libraries was performed using the Illumina sequencing platform to a mean exon coverage depth for targeted regions of >500×, and sequences were analyzed for genomic alterations, including short variant alterations (base substitutions, insertions, and deletions), copy number alterations (focal amplifications and homozygous deletions), and select gene fusions or rearrangements58,59. Germline variants documented in the dbSNP database (dbSNP142) (RRID:SCR_002338) with two or more counts in the ExAC database (RRID:SCR_004068), or recurrent variants of unknown significance that were predicted by an internally developed algorithm to be germline were removed, with the exception of known driver germline events (e.g., documented hereditary BRCA1/2 and deleterious TP53 mutations). Known confirmed somatic alterations deposited in the Catalog of Somatic Mutations in Cancer were highlighted as biologically significant60. All inactivating events (i.e., truncations and deletions) in known tumor suppressor genes were also called significant. To maximize mutation-detection accuracy (sensitivity and specificity) in impure clinical specimens, the test was previously optimized and validated to detect base substitutions at a ≥5% mutant allele frequency (MAF), indels with a ≥10% MAF with ≥99% accuracy, and fusions occurring within baited introns/exons with >99% sensitivity58. Mutational signature calling was performed as described in Huang et al.61 with a Python implementation as described in Franzese et al.62. Dominant signatures were called with a threshold of 0.4 in samples with 10 or more assessable alterations.

Liquid specimens were collected as part of routine clinical care from patients in the United States and from France. French patients were treated at Gustave Roussy and enrolled in the STING precision medicine study (NCT04932525) between 2021 and 2024. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Gustave Roussy. Liquid biopsies were analyzed using the FDA-approved FoundationOne®Liquid CDx NGS hybrid capture panel, which profiles circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) from blood to report various genomic alterations in 311 cancer-related genes. The panel also reports genomic signatures such as blood tumor mutational burden (bTMB), microsatellite instability (MSI), and ctDNA tumor fraction (TF), with bTMB determined on 0.8 megabases and MSI measured across 1800 loci63,64.

The list of analyzed genes is available in Supplementary Table 1.

Viral detection in tissue and liquid biopsies

A de novo assembly of off-target sequencing reads—those unmapped to the human reference genome following the hybrid capture-based approach - was performed as described previously65. These assembled contigs were then competitively aligned to the NCBI database of viral nucleotide sequences to detect HPV (RRID:SCR_013789). HPV genotypes were assigned based on the closest match to reference sequences.

Defining clinically actionable alterations

To evaluate the prevalence of actionable molecular alterations in both liquid and tissue analyses, we applied the OncoKB Therapeutic Level of Evidence V2 (RRID:SCR_014782)66,67. OncoKB is a comprehensive precision oncology knowledge base (available at https://www.oncokb.org/ that classifies molecular alterations based on levels of evidence, ranging from Level 1 (FDA-recognized biomarker) to level 4 (biological evidence).

We also applied an adapted version of the ESMO Scale for Clinical Actionability of molecular Targets (ESCAT) classification68, which ranks molecular alterations according to levels of evidence, from ESCAT I (alteration ready for routine clinical use) to ESCAT X (no evidence for clinical actionability). Although ESCAT criteria specific to aSCC have not yet been published and available data in the literature are limited, we aimed to categorize the molecular alterations identified in this cohort using the ESCAT framework. Only alterations classified as “oncogenic” or “likely oncogenic” were included in levels 1–4.

Ethics

Approval for this study, including a waiver of informed consent and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act waiver of authorization, was obtained from the Western Institutional Review Board (protocol 20152817).

Patients from Gustave Roussy were enrolled in the STING precision medicine study (NCT04932525), which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Gustave Roussy and adhered to the principles in the Guideline for Good Clinical Practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. Genomic results were reviewed and discussed at a weekly MTB. All patients provided written informed consent for participation in the genomic analyses.

Statistical analysis

The analyses were carried out using R Studio version 2023.12.1 + 402.

Data availability

The sequencing data generated in this study is derived from clinical samples. Because of HIPAA requirements, we are not permitted to share individualized patient genomic data, which contains potentially identifying or sensitive patient information. Foundation Medicine is committed to collaborative data analysis, and we have well-established and widely utilized mechanisms by which investigators can query our core genomic database of >800,000 deidentified sequenced cancers to obtain aggregated datasets. More information and mechanisms for data access can be obtained by contacting the corresponding authors or the Foundation Medicine Data Governance Council at data.governance.council@foundationmedicine.com. The clinical data for available patients were collected retrospectively from electronic files.

References

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Wagle, N. S. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J. Clin. 73, 17–48 (2023).

Cancer Tomorrow [Internet]. Available via https://gco.iarc.who.int/today/.

Rao, S. et al. Anal cancer: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up*. Ann. Oncol. 32, 1087–1100 (2021).

Rosado, C., Fernandes, ÂR., Rodrigues, A. G. & Lisboa, C. Impact of human papillomavirus vaccination on male disease: a systematic review. Vaccines 11, 1083 (2023).

Williamson, A. L. Recent developments in human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccinology. Viruses 15, 1440 (2023).

Bruni, L. et al. HPV vaccination introduction worldwide and WHO and UNICEF estimates of national HPV immunization coverage 2010–2019. Prev. Med. 144, 106399 (2021).

Schiller, D. E. et al. Outcomes of salvage surgery for squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 14, 2780–2789 (2007).

Eng, C. et al. The role of systemic chemotherapy and multidisciplinary management in improving the overall survival of patients with metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. Oncotarget 5, 11133–11142 (2014).

Rao, S. et al. International rare cancers initiative multicenter randomized phase II trial of cisplatin and fluorouracil versus carboplatin and paclitaxel in advanced anal cancer: InterAAct. J. Clin. Oncol. 38, 2510–2518 (2020).

Incyte Corporation. A Phase 3 Global, Multicenter, Double-Blind Randomized Study of Carboplatin-Paclitaxel With INCMGA00012 or Placebo in Participants With Inoperable Locally Recurrent or Metastatic Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Anal Canal Not Previously Treated With Systemic Chemotherapy (POD1UM-303/InterAACT 2). Report No.: NCT04472429. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04472429.

National Cancer Institute (NCI). A Randomized Phase III Study of Immune Checkpoint Inhibition With Chemotherapy in Treatment-Naive Metastatic Anal Cancer Patients [Internet]. Report No.: NCT04444921. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04444921.

Rao, S. et al. LBA2 POD1UM-303/InterAACT 2: phase III study of retifanlimab with carboplatin-paclitaxel (c-p) in patients (Pts) with inoperable locally recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal (SCAC) not previously treated with systemic chemotherapy (Chemo). Ann. Oncol. 35, S1217 (2024).

Stouvenot, M. et al. Second-line treatment after docetaxel, cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil in metastatic squamous cell carcinomas of the anus. Pooled analysis of prospective Epitopes-HPV01 and Epitopes-HPV02 studies. Eur. J. Cancer 162, 138–147 (2022).

Saint, A. et al. Mitomycin and 5-fluorouracil for second-line treatment of metastatic squamous cell carcinomas of the anal canal. Cancer Med. 8, 6853–6859 (2019).

Benson, A. B. et al. Anal carcinoma, version 2.2023, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J. Natl Compr. Cancer Netw. 21, 653–677 (2023).

Prete, A. A. et al. Extensive molecular profiling of squamous cell anal carcinoma in a phase 2 trial population: translational analyses of the “CARACAS” study. Eur. J. Cancer 182, 87–97 (2023).

Armstrong, S. A. et al. Molecular characterization of squamous cell carcinoma of the anal canal. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 12, 2423–2437 (2021).

Tanum, G., Tveit, K., Karlsen, K. O. & Hauer-Jensen, M. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy for anal carcinoma. Survival and late morbidity. Cancer 67, 2462–2466 (1991).

De Vuyst, H., Clifford, G. M., Nascimento, M. C., Madeleine, M. M. & Franceschi, S. Prevalence and type distribution of human papillomavirus in carcinoma and intraepithelial neoplasia of the vulva, vagina and anus: a meta-analysis. Int. J. Cancer 124, 1626–1636 (2009).

Luchini, C. et al. ESMO recommendations on microsatellite instability testing for immunotherapy in cancer, and its relationship with PD-1/PD-L1 expression and tumour mutational burden: a systematic review-based approach. Ann. Oncol. 30, 1232–1243 (2019).

Chung, J. H. et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of anal squamous cell carcinoma reveals distinct genomically defined classes. Ann. Oncol. 27, 1336–1341 (2016).

Helsten, T. et al. The FGFR landscape in cancer: analysis of 4,853 tumors by next-generation sequencing. Clin. Cancer Res. 22, 259–267 (2016).

Adar, R., Monsonego-Ornan, E., David, P. & Yayon, A. Differential activation of cysteine-substitution mutants of fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 is determined by cysteine localization. J. Bone Miner. Res. 17, 860–868 (2002).

Ascione, C. M. et al. Role of FGFR3 in bladder cancer: treatment landscape and future challenges. Cancer Treat. Rev. 115, 102530 (2023).

Soo-Kyeong, J. et al. Chylous ascites in an infant with thanatophoric dysplasia type I with FGFR3 mutation surviving five months. Fetal Pediatr. Pathol. 37, 363–371 (2018).

Zingg, D. et al. Truncated FGFR2 is a clinically actionable oncogene in multiple cancers. Nature 608, 609–617 (2022).

Alvarez, G., Perry, A., Tan, B. R. & Wang, H. L. Expression of epidermal growth factor receptor in squamous cell carcinomas of the anal canal is independent of gene amplification. Mod. Pathol. 19, 942–949 (2006).

Yao, Z. et al. Tumours with class 3 BRAF mutants are sensitive to the inhibition of activated RAS. Nature 548, 234–238 (2017).

Xie, M. et al. Age-related mutations associated with clonal hematopoietic expansion and malignancies. Nat. Med. 20, 1472–1478 (2014).

Vasseur, D. et al. Genomic landscape of liquid biopsy mutations in TP53 and DNA damage genes in cancer patients. npj Precis Onc. 8, 51 (2024).

Bayle, A. et al. Liquid versus tissue biopsy for detecting actionable alterations according to the ESMO scale for clinical actionability of molecular targets in patients with advanced cancer: a study from the French National Center for Precision Medicine (PRISM). Ann. Oncol. 33, 1328–1331 (2022).

Aldea, M. et al. Liquid biopsies for circulating tumor DNA detection may reveal occult hematologic malignancies in patients with solid tumors. JCO Precis. Oncol. 7, e2200583 (2023).

Eisenhauer, E. A. et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: Revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur. J. Cancer 45, 228–247 (2009).

Seymour, L. et al. iRECIST: guidelines for response criteria for use in trials testing immunotherapeutics. Lancet Oncol. 18, e143–e152 (2017).

Ito, T. et al. Comparison of clinicopathological and genomic profiles in anal squamous cell carcinoma between Japanese and Caucasian cohorts. Sci. Rep. 13, 3587 (2023).

Hernandez, B. Y. et al. Anal human papillomavirus infection in women and its relationship with cervical infection. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 14, 2550–2556 (2005).

EurekAlert! [Internet]. Contexts of sexualities in France. Available via https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/1064743.

Vasseur, D. et al. Deciphering resistance mechanisms in cancer: final report of MATCH-R study with a focus on molecular drivers and PDX development. Mol. Cancer 23, 221 (2024).

Miranda, K. W., Cimino, S. K. & Eng, C. Targeted fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) inhibition in recurrent, metastatic anal carcinoma: a case report. Clin. Colorectal Cancer 21, 272–275 (2022).

Rose, M., Burgess, J. T., O’Byrne, K., Richard, D. J. & Bolderson, E. PARP inhibitors: clinical relevance, mechanisms of action and tumor resistance. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 8, 564601 (2020).

Shin, M. K. et al. Activating mutations in Pik3ca contribute to anal carcinogenesis in the presence or absence of HPV-16 oncogenes. Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 1889–1900 (2019).

Dumbrava, E. E. et al. PIK3CA mutations in plasma circulating tumor DNA predict survival and treatment outcomes in patients with advanced cancers. ESMO Open 6, 100230 (2021).

US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves Inavolisib with Palbociclib and Fulvestrant for Endocrine-Resistant, PIK3CA-Mutated, HR-Positive, HER2-Negative, Advanced Breast Cancer (FDA, 2024); https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-inavolisib-palbociclib-and-fulvestrant-endocrine-resistant-pik3ca-mutated-hr-positive.

US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves Capivasertib with Fulvestrant for Breast Cancer (FDA, 2024); https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-capivasertib-fulvestrant-breast-cancer.

US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Approves Alpelisib for Metastatic Breast Cancer (FDA, 2024); https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-alpelisib-metastatic-breast-cancer.

Scorpion Therapeutics, Inc. First-in-Human Study of STX-478, a Mutant-Selective PI3Kα Inhibitor as Monotherapy and in Combination With Other Antineoplastic Agents in Participants With Advanced Solid Tumors. Report No.: NCT05768139. https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05768139.

Nakajima, E. C. et al. FDA approval summary: sotorasib for KRAS G12C-mutated metastatic NSCLC. Clin. Cancer Res. 28, 1482–1486 (2022).

US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Grants Accelerated Approval to Adagrasib with Cetuximab for KRAS G12C-Mutated Colorectal Cancer (FDA, 2024); https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-adagrasib-cetuximab-kras-g12c-mutated-colorectal-cancer.

Kim, D. et al. Pan-KRAS inhibitor disables oncogenic signalling and tumour growth. Nature 619, 160–166 (2023).

Marabelle, A. et al. Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Lancet Oncol. 21, 1353–1365 (2020).

Van Allen, E. M. et al. Genomic correlates of response to CTLA-4 blockade in metastatic melanoma. Science 350, 207–211 (2015).

Dhawan, N., Afzal, M. Z. & Amin, M. Immunotherapy in anal cancer. Curr. Oncol. 30, 4538–4550 (2023).

Bayle, A. et al. Clinical utility of circulating tumor DNA sequencing with a large panel: a National Center for Precision Medicine (PRISM) study. Ann. Oncol. 34, 389–396 (2023).

Nakamura, Y. et al. Clinical utility of circulating tumor DNA sequencing in advanced gastrointestinal cancer: SCRUM-Japan GI-SCREEN and GOZILA studies. Nat. Med. 26, 1859–1864 (2020).

Silverberg, M. J. et al. Risk of anal cancer in HIV-infected and HIV-uninfected individuals in North America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 54, 1026–1034 (2012).

Kelly, H. et al. Association of antiretroviral therapy with anal high-risk human papillomavirus, anal intraepithelial neoplasia, and anal cancer in people living with HIV: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet HIV 7, e262–e278 (2020).

Abramowitz, L. et al. Human papillomavirus genotype distribution in anal cancer in France: the EDiTH V study. Int. J. Cancer 129, 433–439 (2011).

Frampton, G. M. et al. Development and validation of a clinical cancer genomic profiling test based on massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 1023–1031 (2013).

Chalmers, Z. R. et al. Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med. 9, 34 (2017).

Forbes, S. A. et al. COSMIC: mining complete cancer genomes in the catalogue of somatic mutations in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D945–D950 (2011).

Huang, X., Wojtowicz, D. & Przytycka, T. M. Detecting presence of mutational signatures in cancer with confidence. Bioinformatics 34, 330–337 (2018).

Franzese, N., Fan, J., Sharan, R. & Leiserson, M. D. M. ScalpelSig designs targeted genomic panels from data to detect activity of mutational signatures. J. Comput. Biol. 29, 56–73 (2022).

Woodhouse, R. et al. Clinical and analytical validation of FoundationOne Liquid CDx, a novel 324-Gene cfDNA-based comprehensive genomic profiling assay for cancers of solid tumor origin. PLoS One. 15, e0237802 (2020).

Vasseur, D. et al. Next-generation sequencing on circulating tumor DNA in advanced solid cancer: Swiss army knife for the molecular tumor board? A review of the literature focused on FDA approved test. Cells 11, 1901 (2022).

Knepper, T. C. et al. The genomic landscape of merkel cell carcinoma and clinicogenomic biomarkers of response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 25, 5961–5971 (2019).

Suehnholz, S. P. et al. Quantifying the expanding landscape of clinical actionability for patients with cancer. Cancer Discov. 14, 49–65 (2024).

Chakravarty, D. et al. OncoKB: a precision oncology knowledge base. JCO Precision Oncol. 2017, PO.17.00011 (2017).

Mateo, J. et al. A framework to rank genomic alterations as targets for cancer precision medicine: the ESMO scale for clinical actionability of molecular targets (ESCAT). Ann. Oncol. 29, 1895–1902 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The work of D. Vasseur is supported by the Institut Servier and by the Philippe Foundation. No funding supported this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.S., D.V., S.D.S., A.H., S.S., M.M., F.F., V.E., F.D.O., K.B., F.B., R.S., L.F., A.I., M.B., and P.D. contributed to writing the main manuscript and preparing the figures. C.S., A.H., V.B., A.B., M.V., I.S., A.B., M.A., J.E.R., M.G., A.T., T.P., R.B., A.F., L.B., E.F.S., S.P., G.B., C.M., K.B., C.M., M.D. were responsible for patient recruitment. C.S., S.D.S., S.S., R.S., and D.V. conceptualized the study. C.S., S.D.S., A.H., S.S., M.M., V.E., L.L., E.R., F.B., A.I., R.S., and D.V. conducted and interpreted the molecular analyses. C.S. and D.V. gathered the clinical data. S.D.S., S.S., M.M., and R.S. performed the bioinformatic analyses. S.D.S., S.S., M.M., and R.S. handled the statistical analysis. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

C.S.: institutional only: Abbvie, Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Astellas, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer–Ingelheim, Hoffmann–La Roche Ltd, Genentech, Loxo, Merck, MSD, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, and Servier. S.D.S.: is an employee of Foundation Medicine, Inc. and a stockholder of Roche Holding AG. AH: personal fees and nonfinancial support from Amgen, personal fees from Basilea, Bristol Myers and Squibb, Servier, Relay Therapeutics, Taiho, MSD, Seagen, grants and personal fees from Incyte, and nonfinancial support from Pierre Fabre outside the submitted work. S.S.: is an employee of Foundation Medicine, Inc. and a stockholder of Roche Holding AG. M.M.: is an employee of Foundation Medicine, Inc. and a stockholder of Roche Holding AG. V.B.: personal fees from Bayer, Ipsen, Amgen, BMS, MSD, and Roche, and nonfinancial support from AstraZeneca outside the submitted work. M.A.: expenses from Sandoz. L.F.: research funding from Debiopharm, Incyte, Relay Therapeutics, Sanofi, and Nuvalent. F.F.: speaker’s fee from Roche. F.B.: institutional only: Abbvie, ACEA, Amgen, Astra-Zeneca, Bayer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer–Ingelheim, Eisai, Eli Lilly Oncology, F. Hoffmann–La Roche Ltd, Genentech, Ipsen, Ignyta, Innate Pharma, Loxo, Novartis, Medimmune, Merck, MSD, Pierre Fabre, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Summit Therapeutics, and Takeda. R.S.: is an employee of Foundation Medicine, Inc. and a stockholder of Roche Holding AG. D.V.: Speaker’s fee from AstraZeneca and Roche. All remaining authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Smolenschi, C., Sisoudiya, S.D., Hollebecque, A. et al. Comprehensive molecular landscape of anal squamous cell carcinoma: analysis of tissue and liquid biopsies from 1844 patients. npj Precis. Onc. 9, 404 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01181-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41698-025-01181-4