Abstract

Synthetic proteoliposomes functionalized with disease-relevant surface markers offer a powerful platform for modeling biological vesicles such as lipid nanoparticles and extracellular vesicles. The simplified composition of proteoliposomes facilitates the design and interpretation of analytic approaches for classifying vesicles and characterizing their contents. Here, we present a library of synthetic proteoliposomes incorporating tumor-associated surface biomarkers—EGFR, α6β4, and αvβ5—and nucleic acid cargo, to mimic cancer-derived extracellular vesicle phenotypes. For molecular fingerprinting, we employed a custom-designed 2D-plasmonic nanocavity platform that enables high-resolution, label-free Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS). Integrated with supervised machine learning algorithms, including Random Forest Classifier (RFC) and Support Vector Machine (SVM), this system achieved robust classification of proteoliposome subtypes with test accuracies of 82% and 76%, respectively. Our results demonstrate the power of combining synthetic vesicle engineering with advanced optical sensing for capturing subtle biomolecular differences. This platform enables standardized, interpretable diagnostic readouts and offers a versatile tool for probing molecular interactions in lipid-based systems such as virus-like particles and nanotherapeutics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is growing interest in developing synthetic lipid vesicle systems for delivering molecular cargo and modelling endogenous vesicle carriers in biology. Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) have revolutionized drug delivery and vaccine development, most notably in the context of mRNA vaccines for SARS-CoV-21,2. LNPs are composed of lipid bilayers or monolayers that encapsulate therapeutic payloads (e.g., RNA, DNA, metabolites, lipids). The vesicles facilitate cellular uptake of their payloads via membrane fusion or endocytosis3,4, enable tissue-specific delivery through lipid engineering, and extend circulation half-life via protecting labile cargo from degradation. Beyond vaccines, LNPs are increasingly applied in gene editing, intracellular protein delivery, and immunotherapy5,6.

There is also significant interest in designing biomimetic platforms that emulate extracellular vesicles (EVs)—endogenous lipid-bound particles that mediate intercellular communication and contribute to key physiological processes such as immune modulation, cellular proliferation, and tissue repair7. EVs carry a rich molecular cargo including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. As this cargo reflects their cellular origin, including the presence of disease-associated biomarkers, EVs are attractive candidates for non-invasive diagnostics. For example, there is hope that EV-based liquid biopsy approaches can improve early detection of aggressive tumors like glioblastoma (GBM) and metastatic breast cancer8. However, clinical translation of EV-based diagnostics remains limited due to challenges such as vesicle heterogeneity, low abundance of disease-specific subtypes, and structural overlap with EVs from healthy tissues9.

Proteoliposomes—synthetic liposomes embedded with functional membrane proteins—represent a promising class of engineered LNPs that mimic the molecular architecture of EVs while offering precise control over their biochemical and biophysical properties10,11. By reconstituting membrane proteins into defined lipid bilayers, proteoliposomes provide a unique tool for investigating membrane-protein function, receptor-ligand interactions, and vesicle-based signaling in a controlled environment12. Moreover, by encapsulating nucleic acids such as plasmid DNA, these vesicles can emulate both the surface and luminal features of EVs, enabling their use as EV surrogates for mechanistic and diagnostic studies13.

Here, we present a proteoliposome platform embedding cancer-relevant biomarkers to model EV structure and cargo. We reconstituted epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and integrins α6β1 and αvβ5 into POPC vesicles and encapsulated pUC18 plasmid DNA. EGFR-enriched EVs are linked to oncogenic signaling, immune modulation, and therapy resistance14,15,16,17. Integrins guide organotropic metastasis via tissue-specific binding: α6β1 to lung stromal cells and αvβ5 to liver Kupffer cells18. POPC (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine) is a zwitterionic lipid with a biologically relevant structure that mimics the outer leaflet of cell membranes12. Its fluid bilayer supports stable incorporation of transmembrane proteins, making it well-suited for constructing EV-like proteoliposomes for biomarker detection.

To enable sensitive and specific molecular profiling of proteoliposome mimetics, we employed Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS), a powerful, label-free technique capable of resolving subtle biochemical differences at the single-vesicle level19,20. However, consistent SERS analysis of nanoscale vesicles remains challenging due to heterogeneity in vesicle populations, random spatial distribution, and signal variability. To address these limitations, we employed the previously developed plasmonic nanocavity platform (MoSERS), a microchip that combines periodic plasmonic nanocavity arrays with a monolayer molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂) substrate. This 2D–plasmonic hybrid design leverages the electromagnetic and electronic properties of MoS₂ to enhance local field confinement, improve signal uniformity, and facilitate reliable detection of nanoscale vesicles.

To support and validate these measurements, we used a custom-built pneumatic confinement device that traps individual vesicles under a flexible membrane for fluorescence co-localization analysis. By mechanically trapping individual vesicles within nanoscale cavities beneath a flexible membrane, the device allowed precise optical interrogation and spatial segregation of particles, minimizing ensemble averaging and improving single-noise ratio. In addition, vesicle properties were characterized via nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA), and we applied machine learning models for classification of complex SERS spectra.

Together, this integration of the plasmonic nanocavity platform, engineered EV mimetics, and machine learning data analysis provides a reproducible and customizable framework for label-free vesicle profiling, with strong potential for early cancer detection and longitudinal disease monitoring via liquid biopsy.

Results

Liposome synthesis and Protein biomarker incorporation

Lipid nanoparticles have garnered increasing interest in biomedical research due to their excellent biocompatibility and structural resemblance to natural extracellular vesicles (EVs). Leveraging these properties, we developed a biomimetic liposomal system composed of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) and different surface protein biomarkers for integration with surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) to enable sensitive and selective cancer biomarker detection (Fig. 1).

a Schematic representation of natural EVs circulating in a blood vessel. b Illustration of a proteoliposome functionalized with a protein biomarker. c Photograph of the in-house fabricated plasmonic nanocavity platform (MoSERS microchip) used for the plasmonic enhancement of Raman signal. d Confocal Raman microscopy setup with 532 nm laser illumination. e Machine learning-assisted identification and classification of liposomes based on their surface biomarkers.

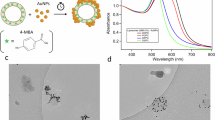

Figure 2a shows the detailed step-wise synthesis of liposome and proteoliposomes particles. Liposomes were synthesized via thin-film hydration method followed by extrusion. POPC lipid was dissolved in chloroform-methanol (2:1 v/v) and mixed with rhodamine-labeled DHPE. The mixture was then dried into a uniform thin film around the bottom of glass tube and hydrated in 10 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.4). The amphipathic nature of phospholipids—featuring hydrophilic head groups and hydrophobic tails drives the spontaneous self-assembly of lipid particle formation during hydration in aqueous buffer21. However, particles produced during hydration are highly heterogeneous in size. In order to achieve homogeneity and reduce particle size, the suspension was extruded through a polycarbonate membrane (100–200 nm pore size), yielding unilamellar vesicles with controlled size.

a Schematic illustration of the liposome/proteoliposome synthesis protocol. b Hydrodynamic size distribution of liposomes and proteoliposomes at varying protein-to-lipid molar ratios. c Hydrodynamic size comparison of liposomes and proteoliposomes functionalized with different biomarkers. d Zeta potential measurements of liposomes and proteoliposomes, showing surface charge variation depending on the biomarker. e Fluorescence microscopy images of liposomes labeled with rhodamine-DHPE (green channel, excitation at 555 nm) and His-tagged proteins labeled with Atto647 NTA-Ni (red channel, excitation at 640 nm). f Intensity distribution histograms of individual particles in the lipid (green) and protein (red) fluorescence channels.

To functionalize these liposome particles with membrane-associated proteins, the preformed liposomes were subjected to a detergent-assisted reconstitution process; this enables stable integration of biomarkers into the lipid bilayer. The addition of 1% Triton X-100 induced partial bilayer solubilization, promoting the formation of lipid-detergent-protein mixed micelles22,23. The mixture was incubated at room temperature for 2 h with brief sonication (2–5 sec) to ensure uniform distribution and avoid clustering. The detergent was removed in two steps consisting of initial incubation of samples with 15 mg Bio-Beads at 4 °C overnight and followed by a second incubation with 30 mg fresh Bio-Beads to ensure complete detergent extraction. This gradual sequestration of detergent molecules induced a thermodynamically favorable micelle-to-bilayer transition, resulting in the self-assembly of proteoliposomes with membrane proteins stably embedded in their native conformation24,25. To assess the efficiency of detergent removal, we prepared samples with varying detergent concentrations and performed dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis. Figure S1a–d presents the changes in particle size and surface charge as a function of detergent concentration. The results indicate that 10 µL of 1% detergent can be nearly completely adsorbed after overnight incubation with 15 mg of BioBeads. In contrast, 20 µL of detergent typically exceeds the adsorption capacity. A sample without detergent and BioBeads was included as a control. Bio-Beads SM-2 enabled precise control over detergent removal by adjusting bead quantity and facilitating near-complete extraction.

To evaluate the physicochemical properties of the synthesized liposomes and proteoliposomes, we employed nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA). As compared to bulk analysis such as DLS, NTA is widely used single-molecule method to measure the size of EV-like particles, particle concentration and zeta-potential. In Fig. 2b, NTA measurements revealed that lipid–protein complexes prepared with varying lipid-to-protein ratios (ranging from 1:0 to 1000:1) consistently exhibited a mean hydrodynamic diameter of approximately 130 nm, indicating uniform vesicle formation across all conditions. Notably, increasing protein concentration did not lead to significant changes in particle size, suggesting that embedded proteins are tightly integrated into the lipid bilayer without contributing substantially to the overall vesicle dimensions. This could also reflect the relatively low number of incorporated proteins per particle, especially in comparison to natural EVs, which typically exhibit higher protein content as measured by antibody-based ELISA quantification26. In addition, we observed that increasing protein concentrations beyond this ratio led to particle clustering (data not shown), a phenomenon consistent with observations reported in previous studies27. For the subsequent experiments, a lipid-to-protein ratio of 500:1 was used. Furthermore, the particle concentration of samples was measured using NTA (Fig. S2a, b), which demonstrated that all samples exhibited comparable particle numbers, with no evidence of clustering, and were therefore suitable for further analysis.

Figure 2c, d further illustrate the size distribution and zeta potential of liposomes and proteoliposomes functionalized with different cancer biomarkers. While the hydrodynamic diameters remained centered around ~160 nm for all formulations (Fig. S2c), the zeta potential values exhibited biomarker-dependent variations. Zeta potential reflects the surface electrochemical potential and provides insights into the surface chemistry and charge characteristics of the particles. Interestingly, EGFR-functionalized liposomes exhibited a significantly more negative zeta potential, consistent with a highly glycosylated extracellular domain and net negative surface charge28. In contrast, α6β4 integrin, which possesses an unusually long cytoplasmic β4 tail likely retained internally during reconstitution, showed zeta potential values similar to unmodified POPC liposomes29. The second integrin (αvβ5) caused only a modest shift in surface charge, possibly due to its compact extracellular domain and limited glycosylation, resulting in near-neutral surface characteristics30. The incorporation of these transmembrane proteins altered the vesicle surface charge, as evidenced by distinct zeta potential profiles, consistent with reported charge modulation upon protein insertion into lipid bilayers30. In addition, the incorporation of pUC18 plasmid DNA in the presence of Triton X-100 led to a significant drop in zeta potential, indicating strong electrostatic loading or surface adsorption of the highly charged DNA onto POPC liposomes. The detergent likely facilitated temporary membrane destabilization, enabling DNA–lipid association.

In order to confirm the colocalization of liposome with incorporated protein, we used dual fluorescence in which lipids were labeled with rhodamine-red, and the His-tagged protein was conjugated with Atto647. To facilitate this analysis we used a custom-built, adjustable confinement device described in Capaldi et al. 31. The device consists of a borosilicate glass substrate that incorporates two intersecting nanoslits for sample loading and an array of circular cavities (with radius 1000 nm and depth of 300 nm) embedded at the intersection of the microchannels. Above the cavities, there is a flexible nitride free-standing membrane (200 nm thick) acting as a lid. When pneumatic pressure is applied the membrane deflects, resulting in trapping of individual particles in the embedded cavities32,33. At sufficient applied pressure, the membrane is fully deflected and the nanocavities are sealed, isolating captured single liposome or proteoliposome particles. The protein channel was excited at 640 nm, while the lipid (rhodamine-red) channel was excited at 550 nm with excitation power optimized to reduce the crosstalk significantly. Each cavity was observed to contain a single vesicle, with multiple occupancy suppressed by electrostatic forces between like-charged particles. Colocalization was indicated by the presence of signals in both channels within the same cavity. A total of 447 particles were analyzed, among which 155 exhibited a protein signal, indicating that approximately 34% of liposomes were associated with proteins. Figure 2e show representative fluorescence images from the lipid, protein channels and merged images, respectively, averaged over 30 frames. Colocalized particles, visible in both channels, are circled with dotted lines, and each particle is confined within a distinct cavity. The intensity of each individual particle detected in separate channels was recorded to generate intensity histograms presented in Fig. 2f. The lipid intensity distribution shows a single peak, whereas the protein channel displays additional peaks, potentially corresponding to the variation in the numbers of protein per liposome.

SERS Analysis and MoSERS Microchip Characterization

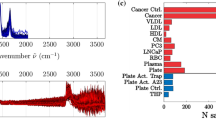

The MoSERS microchip is a nano plasmonic platform fabricated in-house using the procedure described in Jalali et al.34. Figure 3a illustrates the stepwise fabrication process along with corresponding SEM images: (i) a monolayer of MoS2 deposited on a Si/SiO2 substrate; (ii) the substrate is spin-coated with a SurPass 3000 priming layer followed by a ~ 650–700 nm-thick layer of negative e-beam resist (ma-N 2403); (iii) after electron beam lithography and development, 80 nm of TiO₂ are deposited followed by 60 nm Ag; (iv) finally liftoff of the remaining resist leaves behind a patterned array of open nanocavities. Figure 3b shows a schematic of the MoSERS microchip chip with sample incubated and 532 nm laser illumination. The cavities are equally spaced with a 3 μm pitch in a rectangular pattern to ensure each cavity is scanned independently during the Raman imaging. This cavity design combines localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) from Ag/TiO₂ nanocavities with the excitonic and electronic properties of monolayer MoS₂, resulting in enhanced electromagnetic field confinement and improved SERS performance. Plasmon–exciton coupling at the nanocavity edges creates hybridized states that intensify and homogenize local fields, while charge transfer between MoS₂ and analytes contributes to chemical enhancement. As previously demonstrated (Jalali et al.)35, molecular dynamics simulations revealed that monolayer MoS₂ preferentially interacts with phospholipid bilayer membranes at its edge sites, facilitating stable entrapment and biomarker localization. These interactions are thermodynamically favorable and support the platform’s high sensitivity and specificity in biomolecule detection with phospholipid bilayer structure. To evaluate the SERS enhancement of the MoSERS microchip, we used Rhodamine 6 G (R6G) as a standard Raman active analyte. Nanocavities were incubated with 1 μM R6G solution and laser scanned. Figure 3c shows the SERS spectra collected from the nanocavity (Cyan) and from adjacent flat (grey) region. The signal exhibited from cavity region is over 54-fold higher than those recorded from adjacent flat regions, which is due to the free electrons in the Ag thin film coated cavities resulting in an enhanced localized electromagnetic field confinement in the vicinity of the nanocavities. In Fig. 3d, SERS spectra for R6G were recorded, and the intensity of key Raman bands such as 1362 cm−1, 1510 cm−1, and 1650 cm−1 were evaluated. To benchmark the plasmonic performance of the MoSERS microchip, we calibrated the electromagnetic field enhancement factor (EFEF) by integrating the band areas of the SERS spectra. The EFEF scales with the fourth power of the local field enhancement \({\left(\frac{\left|\left.E\left(\omega \right)\right|\right.}{\left|\left.{E}_{0}\left(\omega \right)\right|\right.}\right)}^{4}\). To further quantify the sensing performance, we calculated the SERS enhancement factor, \({EF}=\,\left(\frac{{I}_{{SERS}}}{{N}_{{SERS}}}\right)/\left(\frac{{I}_{{Raman}}}{{N}_{{Raman}}}\right)\) and the limit of detection (LOD). Based on intensity measurements at a characteristic Raman peak (1650 cm-1), the EF was determined to be 54.45, comparing signals from nanocavity regions to flat silver surfaces. Using the calibration curve of Raman intensity versus R6G concentration, the slope was estimated to be 0.65 (Intensity × 10³ a.u./μM) with an R² of 0.97 (Fig. 3e). The LOD was calculated using the standard formula (LOD = 3σ/S), a detection limit of 0.23 μM was observed. These results demonstrate the high sensitivity, reproducibility, and plasmonic enhancement capabilities of the MoSERS microchip.

a Fabrication steps of the MoSERS microchip: (i) monolayer MoS₂ on Si/SiO₂ substrate (SEM image shows triangular monolayer MoS₂ domains; (ii) patterning using negative e-beam lithography with Man-2403 resist, followed by exposure and development; (iii) deposition of a TiO₂ as a back-reflector and a silver (Ag) layer (SEM image highlights the resist posts); and (iv) final hot liftoff step removes remaining resist, creating nanocavities (SEM image shown). b Schematic illustration of the MoSERS microchip during sample incubation and 532 nm laser illumination. c SERS intensity map of Rhodamine 6 G (R6G), comparing signals from flat regions (gray) and nanocavities (blue). d Comparison of average SERS peak intensities at 1650 cm−1, 1510 cm−1, and 1362 cm−1 for R6G collected from nanocavities (blue) and flat silver thin film areas (gray). e Sensitivity analysis of R6G on MoSERS substrate shows a linear detection range from 0.01 to 200 µM with an R² value of 0.97. f–j Representative SERS spectra for proteoliposome complexes including: (f) liposome only, (g) +egfr, (h) +αvβ5, (i) + DNA, and (j) α6β4-functional-zed proteoliposomes. k Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plot showing separation of classes along PC1 and PC2.

Prior to machine learning analysis, all collected SERS data were preprocessed including base line correction, smoothing and normalization (Fig. S3). A total of 75-85 SERS spectra for each sample were collected with wavenumbers ranging from 100–3000 cm−1 (number of spectra for each sample is shown in Table S1). Figure 3f–j represents the five representative spectra from each sample. While each spectrum exhibits unique intensity and Raman peaks, all share prominent bands around 1200–1600 cm−1 reflecting intrinsic biochemical similarities among the proteoliposome compositions. To evaluate the potential for unsupervised dimensionality reduction and clustering, principal component analysis (PCA) was initially applied to the preprocessed spectra. As shown in Fig. 3k, the PCA scores for the first two principal components (PC1 vs. PC2) revealed partial clustering among the different liposomal groups. However, notable overlaps were also observed, indicating that PCA alone was insufficient for full discrimination due to the spectral resemblance of the biomarkers. Interestingly, the sample with DNA as a biomarker showed significant clustering compared to protein samples which could be due to the presence of much higher concentration of nucleic acids (~2.6 kb plasmid DNA) within the lipid bilayer36. It also correlates with the increase in net surface charge as reflected in the higher zeta-potential value for DNA sample.

Machine learning assisted classification

Machine learning methods such as random forest classifier (RFC) and support vector machine (SVM) are commonly used to effectively capture subtle spectral differences in higher-dimensional SERS data37,38. To classify the spectral data, we employed both RFC and SVM as supervised machine learning algorithms. RFC is an ensemble method that constructs multiple decision trees on randomized subsets of the data and aggregates their outputs, offering robustness to overfitting and high interpretability through feature importance analysis. In contrast, SVM aims to identify an optimal hyperplane that maximally separates data points of different classes, with the flexibility to model nonlinear boundaries using kernel functions. Together, these methods provide complementary approaches for accurate and reliable classification of complex Raman spectral patterns39.

The preprocessed SERS data were randomly split into training (80%) and testing (20%) sets (Fig. 4a). Hyperparameters for both models were optimized using a grid search strategy combined with stratified 5-fold cross-validation. Details of the optimized hyper-parameters are reported in Table S2. Each model’s performance was evaluated using precision, recall, and f1-score generated over five different training and testing sets (Fig. S4), providing a comprehensive assessment of classification robustness. A comparative analysis of true versus predicted biomarker labels for quaternary classification is presented as a confusion matrix. The RFC model achieved an overall test accuracy of 82%, with class-wise accuracies of 73% (DNA), 93% (α6β4), 80% (αvβ5), and 81% (EGFR) (Fig. 4b). The SVM model yielded a slightly lower overall accuracy of 75%, with class-wise accuracies of 81% (DNA), 64% (α6β4), 80% (αvβ5), and 81% (EGFR) (Fig. 4c). These results highlight the models’ sensitivity to biomarker-specific spectral variations in proteoliposomes.

a Schematic representation of the ML pipeline used for SERS data analysis. b, c Normalized confusion matrices showing classification performance for different proteoliposome complexes using Random Forest Classifier (RFC) and Support Vector Machine (SVM), respectively. d, e Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves for each proteoliposome class generated by RFC and SVM, respectively. f, g Average classification accuracy across five independent train/test splits for RFC and SVM models, respectively, demonstrating model generalizability; note that training accuracy remained at 100%.

To further evaluate classifier performance, we conducted receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis using a one-vs-rest approach. Both models yielded high area under the curve (AUC) values (~0.97–0.98; Fig. 4d, e), indicating strong discriminative capability across all biomarker classes. Importantly, both RFC and SVM demonstrated the ability to resolve subtle, biomarker-specific spectral features, underscoring the molecular-level sensitivity of our MoSERS platform.

As shown in the boxplot comparison (Fig. 4f, g), RFC exhibited consistently higher mean test accuracy and lower variance compared to SVM across five training–testing splits. While both models achieved perfect accuracy on the training sets, RFC maintained tighter performance bounds on unseen testing data, reflecting better generalization and robustness. This performance stability is particularly valuable for moderate-sized spectral datasets, where overfitting risks are elevated. Furthermore, the low dispersion in RFC outcomes aligns with its ensemble nature mitigates sensitivity to feature noise and sample distribution shifts. In contrast, SVM showed greater variability between runs, potentially reflecting its dependence on support vector boundary selection in high-dimensional Raman data.

The unique ability of our MoSERS nanocavity platform to isolate and trap individual vesicles highlights its potential for single-vesicle SERS measurements, enabling the resolution of fine molecular distinctions34. By applying the RFC classifier to MoSERS data, we achieved high-resolution (82%) classification accuracy of proteoliposomes functionalized with distinct biomarkers. Together, these findings highlight the potential of integrating machine learning with SERS spectral data to enable accurate, label-free classification of cancer-related liposomal biomarkers, even in cases of strong spectral similarity.

Discussion

In this study, surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) was employed as the principal analytical tool for high-resolution, label-free molecular profiling of synthetic proteoliposomes functionalized with cancer-relevant biomarkers. This builds on the previous work (Jalali et al.), where the plasmonic nanocavity platform successfully profiled glioblastoma (GBM)-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) with 97% single-vesicle confinement in <10 μL of fluid35. Here, we demonstrate the platform’s molecular discrimination capabilities and sensitivity to resolve subtle spectral differences among vesicles carrying DNA, EGFR, αvβ5, and α6β4. To decode the complex SERS spectral signatures, we implemented supervised machine learning approaches. Random forest classification (RFC) achieved an overall accuracy of 82%, outperforming support vector machines (SVMs), which yielded ~75% accuracy. High area under the curve (AUC) values approaching unity further confirmed the models’ ability to distinguish between vesicles bearing highly similar membrane protein signatures. Together, the synergistic use of 2D-material-based SERS enhancement and engineered proteoliposomes establishes a versatile framework for advanced molecular sensing with broad relevance to biomedical diagnostics and single-particle analysis.

Methods

Materials

Lipids such as 16:0–18:1 PC were purchased from Avanti Lipids, and Rhodamine-DHPE was sourced from Biotium. His-tag proteins such as recombinant human EGFR were purchased from R&D system. Integrin alpha 6 beta 4 and alpha V beta 5 protein were purchased from MCE. HIS Lite™ iFluor 647 Tris NTA-Ni complex, Rhodamine-6G, and Triton™ X-100 were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Bio-Beads SM-2 adsorbents were purchased from Bio-Rad. Proteins were labeled according to the instructions provided by Sigma-Aldrich and aliquoted for storage at −20 °C.

Preparation of liposomes and proteoliposomes

Liposomes were prepared by the thin-film hydration method followed by extrusion. We used 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) lipid dissolved in chloroform-methanol (2:1 v/v) to a final concentration of 10 mg/ml. Fluorescently labelled lipid N-(Lissamine rhodamine B sulfonyl)-1,2-dihexadecanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospheoethanolamine, triethylammonium salt (Rhodamine-DHPE) (Biotium, Inc.) was dissolved in chloroform to a final concentration of 5 mg/ml. Rhodamine labelled lipid DHPE (1%) was added to the mixture followed by the drying with a high-pressure air stream. The lipid mixture was rehydrated with 10 mM Tris buffer to a final concentration of 1 mg/ml followed by extrusion through 100–200 nm using Mini extruder (Avanti lipids) resulting ~1012 particles/ml. The preformed liposomes were used for protein and DNA incorporation by mixing the protein or DNA in detergent (1% Triton X-100) followed by brief sonication (2 s) and incubation at room temperature for 2 h. After the incubation 15 mg SM beads were added and incubated over night at 4 °C followed by second addition of 30 mg SM beads to remove the detergent efficiently.

Fabrication of the MoSERS Microchip

The detailed fabrication protocol is described in Jalali et al. 34. The MoS2 monolayer on SiO₂/Si substrates used in this study was purchased from 2D Semiconductors, USA (SKU: CVD-MoS2-ML-S, size 1 cm x 1 cm). The electron beam resist ma-N 2403 was obtained from micro resist technology GmbH (Berlin, Germany) and used as a negative-tone resist for patterning the nanocavity structures. The top-down negative e-beam lithography technique was used to fabricate a silver plasmonic nanohole array using a Reith ebeam writer. The direct-write capability of e-beam lithography enabled the creation of plasmonic nanostructures with high patterning resolution, precise placement accuracy, and extensive design flexibility. A square array of circular nanocavities with diameters approximately 600 nm was defined in a 650–700 nm thick maN resist layer. After pattern development, 80 nm of TiO2 was deposited as a back reflector, and for improved adhesion to the plasmonic layer formed by thermal evaporation of silver (Ag) with a thickness of 60 nm. The thickness of the Ag layer was optimized to support localized surface plasmon resonance within the nanocavity structure. The thickness was confirmed using a quartz crystal microbalance during deposition. This was followed by 3–6 h lift-off process in 1165 remover. Finally, the samples were washed with IPA followed by copious amount of dH2O wash.

Nanoparticle tracking analysis

Concentration, size distribution and zeta potential of suspended particles for each sample were obtained via a ZetaVIEW PMX-120 nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) instrument (Particle Metrix GmbH, Inning am Ammersee, GER). As per instrument requirements, samples were first diluted to 50-250 particles per frame by serial dilution before 1 mL of unlabeled sample was loaded into the ZetaVIEW. Samples were measured using the 488 nm laser at an instrument sensitivity of 70-80 and processed with ZetaVIEW software (version 8.5.16.1007) to evaluate concentration and median size range of the suspended particles.

Fluorescence microscopy

A homemade adjustable confinement device was fabricated as described in Capaldi et al. 31. The device was secured to a 3D printed chuck and mounted on a Nikon Ti Eclipse inverted microscope with a Nikon Plan Apo VC 60x water objective, a highly sensitive 95 PRISM 20MM camera, and a multi-wavelength light source (Lumencor). The imaging system is controlled by NIS elements software from Nikon and the pneumatic pressure is modulated by a benchtop pressure controller, which communicates with the computer via a NI DAQ board using software.

The samples were diluted to 1000x before manually loading them with a syringe pump and the inlets/outlets are connected directly to the atmosphere when the membrane is actuated. A constant 300–350 mbar pressure is applied to ensure the membrane is completely deflected, and videos are captured in real-time40. The particle detection was performed on an average of 30 frame movies (100 ms/frame) using Detection of Molecules (DOM) plugin for ImageJ41.

Raman spectroscopy

Surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) capabilities of the MoSERs microchip were assessed using widely used Raman active Rhodamine-6G applied to platform surfaces with varying concentrations. SERS spectra were collected using a Renishaw InVia Raman microscope (Renishaw plc, Wotton-under-Edge, UK) in backscattering geometry. The instrument was equipped with a 532 nm HeNe laser (Melles-Griot, Voisins Le Bretonneux, France), delivering 15 mW of 1% laser power, and the laser polarization was aligned along the x-axis. Samples were mounted on a ProScan II motorized stage (Prior, Cambridge, UK) under the microscope, with a Leica 50x objective lens (NA 0.55) focusing the laser beam of spot size ~1.6 µm onto the sample surface. An 1800 lines/mm grating provided a spectral resolution of ~754 cm⁻¹, and a thermoelectrically cooled CCD camera was used for signal detection. A standard silicon substrate (520 cm−1) was used for the spectrograph calibration. SERS spectra were acquired with a 10 s exposure at 0.5% laser intensity. A Wire 5.1 (Renishaw) system in synchro mode was used to collect each spectrum from 100 cm−1 to 3200 cm−¹ range. SERS measurements were performed by interrogating ~80 nanocavities on MoSERS microchip to ensure reproducibility and spatial uniformity.

Data processing and analysis

SERS data was preprocessed including baseline correction, normalization (0,1) and smoothing (steps described in Fig. S3). Fluorescence images were analysed with ImageJ. Unsupervised clustering such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and supervised classification such as Random Forest classifier (RFC) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) were performed with custom-built python scripts.

Data availability

The raw data is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hou, X., Zaks, T., Langer, R. & Dong, Y. Lipid Nanoparticles for mRNA Delivery. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 1078–1094 (2021).

Sahin, U. et al. COVID-19 Vaccine BNT162b1 Elicits Human Antibody and TH1 T Cell Responses. Nature 586, 594–599 (2020).

Kulkarni, J. A., Witzigmann, D., Leung, J., Tam, Y. Y. C. & Cullis, P. R. On the Role of Helper Lipids in Lipid Nanoparticle Formulations of siRNA. Nanoscale 11, 21733–21739 (2019).

Buschmann, M. D. et al. Nanomaterial Delivery Systems for mRNA Vaccines. Vaccines 9, 65 (2021).

Xiao, W. et al. Advance in peptide-based drug development: delivery platforms, therapeutics and vaccines. Sig Transduct. Target Ther. 10, 74 (2025).

Wang, H.-X. et al. Nonviral Gene Editing via CRISPR/Cas9 Delivery by Membrane-Disruptive and Endosomolytic Helical Polypeptide. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. Usa. 115, 4903–4908 (2018).

van Niel, G., D’Angelo, G. & Raposo, G. Shedding Light on the Cell Biology of Extracellular Vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 213–228 (2018).

Alix-Panabières, C. & Pantel, K. Liquid Biopsy: From Discovery to Clinical Application. Cancer Discov. 11, 858–873 (2021).

Li, P., Kaslan, M., Lee, S. H., Yao, J. & Gao, Z. Progress in Exosome Isolation Techniques. Theranostics 7, 789–804 (2017).

Akbarzadeh, A. et al. Liposome: Classification, Preparation, and Applications. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 8, 102 (2013).

Pattni, B. S., Chupin, V. V. & Torchilin, V. P. New Developments in Liposomal Drug Delivery. Chem. Rev. 115, 10938–10966 (2015).

Rigaud, J.-L. & Lévy, D. Reconstitution of Membrane Proteins into Liposomes. Methods Enzymol. 372, 65–86 (2003).

Denisov, I. G. & Sligar, S. G. Nanodiscs for Structural and Functional Studies of Membrane Proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 23, 481–486 (2016).

Levantini, E., Maroni, G., Del Re, M. & Tenen, D. G. EGFR Signaling Pathway as Therapeutic Target in Human Cancers. Semin. Cancer Biol. 85, 253–275 (2022).

Makinoshima, H. et al. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) Signaling Regulates Global Metabolic Pathways in EGFR-Mutated Lung Adenocarcinoma *. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 20813–20823 (2014).

Sasabe, E. et al. Epidermal Growth Factor/Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Signaling Blockage Inhibits Tumor Cell-Derived Exosome Uptake by Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma through Macropinocytosis. Cancer Sci. 113, 609–621 (2022).

Yokoi, A. et al. Integrated Extracellular microRNA Profiling for Ovarian Cancer Screening. Nat. Commun. 9, 4319 (2018).

Hoshino, A. et al. Tumour Exosome Integrins Determine Organotropic Metastasis. Nature 527, 329–335 (2015).

Guerrini, L., Krpetić, Ž, van Lierop, D., Alvarez-Puebla, R. A. & Graham, D. Direct Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Analysis of DNA Duplexes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 54, 1144–1148 (2015).

Jalali, M. et al. Plasmonic Nanobowtiefluidic Device for Sensitive Detection of Glioma Extracellular Vesicles by Raman Spectrometry. Lab. Chip 21, 855–866 (2021).

Saak, C.-M., Dreier, L. B., Machel, K., Bonn, M., & Backus, E. HG. Biological Lipid Hydration: Distinct Mechanisms of Interfacial Water Alignment and Charge Screening for Model Lipid Membranes. (2024). https://doi.org/10.1039/D3FD00117B.

Shen, H.-H., Lithgow, T. & Martin, L. L. Reconstitution of Membrane Proteins into Model Membranes: Seeking Better Ways to Retain Protein Activities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 1589–1607 (2013).

Veit, S., Paweletz, L. C. & Pomorski, T. G. Determination of Membrane Protein Orientation upon Liposomal Reconstitution down to the Single Vesicle Level. Biol. Chem. 404, 647–661 (2023).

Johnson, Z. L. & Lee, S.-Y. Chapter Seventeen - Liposome Reconstitution and Transport Assay for Recombinant Transporters. In Methods in Enzymology; Shukla, A. K., Ed.; Membrane Proteins—Production and Functional Characterization; Academic Press, 2015; Vol. 556, pp 373–383.

Rigaud, J.-L. & Lévy, D. Reconstitution of Membrane Proteins into Liposomes. In Methods in Enzymology; Liposomes, Part B; Academic Press, 2003; Vol. 372, pp 65–86.

Logozzi, M., Di Raimo, R., Mizzoni, D. & Fais, S. Immunocapture-Based ELISA to Characterize and Quantify Exosomes in Both Cell Culture Supernatants and Body Fluids. Methods Enzymol. 645, 155–180 (2020).

Goose, J. E. & Sansom, M. S. P. Reduced Lateral Mobility of Lipids and Proteins in Crowded Membranes. PLOS Comput. Biol. 9, e1003033 (2013).

Gamou, S. & Shimizu, N. Glycosylation of the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor and Its Relationship to Membrane Transport and Ligand Binding1. J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 104, 388–396 (1988).

Sonnenberg, A. et al. Integrin Alpha 6/Beta 4 Complex Is Located in Hemidesmosomes, Suggesting a Major Role in Epidermal Cell-Basement Membrane Adhesion. J. Cell Biol. 113, 907–917 (1991).

Cedervall, T. et al. Understanding the Nanoparticle–Protein Corona Using Methods to Quantify Exchange Rates and Affinities of Proteins for Nanoparticles. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 104, 2050–2055 (2007).

Capaldi, X. et al. Probing the Organization and Dynamics of Two DNA Chains Trapped in a Nanofluidic Cavity. Soft Matter 14, 8455–8465 (2018).

Hosseini, I. I. et al. Nanofluidics for Simultaneous Size and Charge Profiling of Extracellular Vesicles. Nano Lett. 21, 4895–4902 (2021).

Liu, Z. et al. Characterizing Interaction of Multiple Nanocavity Confined Plasmids in Presence of Large DNA Model Nucleoid. Soft Matter 19, 6545–6555 (2023).

Jalali, M. et al. MoS2-Plasmonic Nanocavities for Raman Spectra of Single Extracellular Vesicles Reveal Molecular Progression in Glioblastoma. ACS Nano 17, 12052–12071 (2023).

Jalali, M., Lu, Y., del Real Mata, C., Rak, J. & Mahshid, S. Nanoscopic Technologies toward Molecular Profiling of Single Extracellular Vesicles for Cancer Liquid Biopsy. Appl. Phys. Rev. 12, 011312 (2025).

Morzy, D. et al. Cations Regulate Membrane Attachment and Functionality of DNA Nanostructures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 7358–7367 (2021).

Ho, C.-S. et al. Rapid Identification of Pathogenic Bacteria Using Raman Spectroscopy and Deep Learning. Nat. Commun. 10, 4927 (2019).

Walter, A., März, A., Schumacher, W., Rösch, P. & Popp, J. Towards a Fast, High Specific and Reliable Discrimination of Bacteria on Strain Level by Means of SERS in a Microfluidic Device. Lab. Chip 11, 1013–1021 (2011).

Seifert, S. Application of Random Forest Based Approaches to Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Data. Sci. Rep. 10, 5436 (2020).

Hosseini, I. I. et al. Tunable Nanofluidic Device for Digital Nucleic Acid Analysis. Nanoscale 16, 9583–9592 (2024).

Katrukha, E., Teeuw, J., bmccloin; Braber, J. den. Ekatrukha/DoM_Utrecht: Detection of Molecules 1.2.5, 2022. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7326569.

Acknowledgements

Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI G24892), Charles Bruneau Foundation/ The Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre (RI-MUCH) 9094 (G259300). 265636 CIHR project grant. S.M. was supported by a Canada Research Chair (CRC) award. W.R. was supported by the Fonds de recherche du Québec – Nature et technologies (FRQNT, Grant PR-286442). J.R. received support from a Foundation Grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), the Cancer Research Society (CRS), a Genome Québec Operating Grant, the McGill Interdisciplinary Initiative in Infection and Immunity (MI4) Seed Grant, the Canada Foundation for Innovation (CFI), and the NET program sponsored by Fondation Charles-Bruneau (FCB). C.d.R.M. acknowledges the support from Fonds de Recherche du Québec - Nature et Technologies (FRQNT) doctoral fellowship and the Faculty of Engineering for the McGill Engineering Doctoral Award (MEDA).The authors also acknowledge the Laboratoire de microfabrication (LMF) at Polytechnique Montréal, the Centre for Applied Nanomedicine (CAN) at the Research Institute of the McGill University Health Centre (RI-MUHC) and the NanoQAM research facilities at the Université du Québec à Montréal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S. and Y.Z. performed experiments, sample preparation, Raman data collection, data analysis, and wrote the main manuscript. S.S. and C.R.D.M. fabricated the microchip and carried out the physical characterizations. M.J. developed the protocol for microfabrication. I.H. and Z.L. contributed to fabricating pneumatic device. J.M. and L.M. contribute to NTA analysis. S.S. conducted the machine learning analysis. J.R. provided scientific guidance throughout the project and contributed to manuscript review. S.V.H., Z.L., and M.A.S.P. supported the investigation. S.M. and W.R. supervised the project from conception to development, contributed to figure design, and were involved in manuscript writing and reviewing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shiekh, S., Zhou, Y., Real Mata, C.d. et al. Proteoliposomes on 2D-MoS₂ plasmonic nanocavities for enhanced Raman spectroscopy with machine learning-based identification and classification. npj 2D Mater Appl 9, 115 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00636-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41699-025-00636-3