Abstract

Particulate matter (PM) exposure can reduce heart rate variability (HRV), a cardiovascular health marker. This study examines PM1.0 (aerodynamic diameters <1 μm), PM2.5 (≥1 μm and <2.5 μm), and PM10 (≥2.5 μm and <10 μm) effects on HRV in patients with environmental diseases as chronic disease groups and vulnerable populations as control groups. PM levels were measured indoors and outdoors for five days in 97 participants, with 24-h HRV monitoring via wearable devices. PM exposure was assessed by categorizing daily cumulative PM concentrations into higher and lower exposure days, while daily average PM concentrations were used for analysis. Results showed significant negative associations between exposure to single and mixtures of different PM metrics and HRV across all groups, particularly in chronic airway disease and higher air pollution exposed groups. These findings highlight that even lower PM levels may reduce HRV, suggesting a need for stricter standards to protect sensitive individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Environmental pollutants are known to have adverse effects on health, and air pollution, such as particulate matter (PM), is a serious global issue due to its negative impact on human health. Numerous studies have emphasized the effects of PM on mortality and morbidity related to cardiovascular diseases (CVD)1,2,3,4. Short- and long-term exposure to PM can have various effects on cardiovascular health, with greater risks observed in vulnerable and susceptible populations, such as patients with CVD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and older people1,3,5.

The proposed mechanisms to explain the association between PM inhalation and CVD include oxidative stress, systemic inflammation6,7, insulin resistance8, epigenetic modifications9, and alterations in cardiac autonomic function and the autonomic nervous system1,8. Notably, the impact on the autonomic nervous system forms the basis of the link between PM and CVD, with heart rate variability (HRV) serving as a useful non-invasive measure for assessing the autonomic regulation of heart rhythm. HRV can be recorded over short (typically 5–15 min) or long-term (24-h) periods10. Reduced HRV is a significant prognostic tool for various CVD, and long-term HRV assessments are more accurate indicators for evaluating cardiovascular conditions than short-term HRV10,11,12,13. Epidemiological evidence suggests that short-term PM exposure is associated with a reduction in most long-term HRV indices, particularly in sensitive groups such as older people14,15, patients with CVD16,17, COPD patients18, those with occupational exposure19,20, or individuals with hypertension or diabetes5,15.

There is consistent evidence that the association between the reduction in HRV and exposure to PM depends on the particle size and subject population. In the general healthy population, occupational exposure, and cardiovascular patients, exposure to PM1.0 has been linked to a reduction in HRV21,22. In cardiovascular patients, patients with COPD, and older people, exposure to PM2.5, has been associated with HRV reduction14,16,23, while PM10 exposure has been linked to decreased HRV in patients with COPD18. The type of particles and the magnitude of their association with HRV reduction may vary depending on the subject population and specific pollutants involved.

Most previous studies have evaluated exposure using environmental pollution monitoring devices located in various districts. There is a lack of research exploring the relationship between environmental pollutant exposure in personal living spaces and HRV using both indoor and outdoor measurement devices. Unlike outdoor air, indoor air quality can be altered at an individual level24; therefore, both indoor and outdoor air should be considered when assessing PM exposure25. Additionally, because individuals are not exposed to environmental pollutants in isolation but rather to a mixture of various substances, an analysis of complex exposure is also necessary. Some complex exposure analyses have utilized combinations of PM components26,27; however, the measurements did not fully reflect the overall personal living environment and were not evaluated according to particle size.

Our study addresses these gaps by employing a comprehensive approach that simultaneously examines indoor and outdoor air quality, while also considering the mixed exposure to different PM sizes (PM1.0, PM2.5, and PM10) in real time. Furthermore, the application of a Bayesian kernel machine regression model (BKMR)28 allows us to more accurately model the nonlinear and potentially synergistic effects of mixed-substance exposures on HRV, particularly in vulnerable populations. This novel approach not only fills a critical void in existing research but also provides a more nuanced understanding of the health risks posed by PM in diverse living environments. Therefore, this study specifically aimed to investigate the relationship between short-term exposure to PM (PM1.0, PM2.5, and PM10) and 24-h real-time HRV measurements in patients with environmental diseases (patients with arrhythmia, chronic airway disease, and stroke) and vulnerable populations (residents of an industrial complex area, older people), using equipment capable of measuring both indoor and outdoor environments. The study will take into account individual sensitive characteristics (medical history, age, gender, disease) and personal living spaces and will examine both single-substance and mixture-substance exposures.

Results

Description of living lab participants

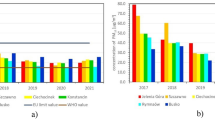

Table 1 presents the basic descriptive statistics for each of the labs. The total number of study participants was 97, including 19 patients with arrhythmia, 20 with chronic airway disease, 19 with stroke in the chronic disease group, 19 residents in higher air pollution exposed persons, and 19 older people individuals. There were more males than females, and the average age was 65.52 (12.04) years, with the older people group having the highest average age of 71.42 years. The average concentrations of PM1.0, PM2.5, and PM10 were 9.89 (9.78), 10.46 (10.36), and 10.53 (10.44) µg/m3, respectively, with higher air pollution exposed persons having the highest average concentrations of PM1.0, PM2.5, and PM10. The standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals (SDNN) was 138.96 (63.06), the standard deviation of the average NN intervals for each 5-min segment of a 24-h HRV recording (SDANN) was 98.25 (39.26), the mean of the standard deviations of all NN intervals for each 5-min segment of a 24-h HRV recording (SDNNI) was 68.01 (41.11), and the root mean square of successive RR interval differences (RMSSD) was 77.37 (66.07). Among these, 24-h SDNN, SDANN, and SDNNI were the lowest in patients with arrhythmia, whereas RMSSD was the lowest in patients with chronic airway diseases.

The concentrations of environmental pollutants and 24-h HRV were compared based on the days with the higher and lower cumulative PM concentrations (Table 2). The daily average concentrations of PM1.0, PM2.5, and PM10 were significantly higher on days with high cumulative concentrations. Although there was no statistically significant difference in 24-h HRV between the days with higher and lower cumulative concentrations, the values were lower on the days with higher cumulative concentrations; SDNN was 137.60 (57.98), SDANN was 97.34 (37.31), SDNNI was 66.67 (39.14), and RMSSD was 76.85 (63.52), compared to the days with lower cumulative concentrations.

Association between exposure to single and mixtures of PM metrics and HRV

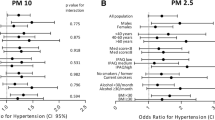

Figure 1 shows the results of the regression analysis stratified by days with higher and lower cumulative concentrations of each environmental pollutant using age, sex, BMI, respiration rate, smoking, alcohol consumption, METs, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, TVOC, humidity, and temperature as adjustment variables. On both the high and low cumulative concentration days, each daily average PM substance showed a negative trend with 24-h HRV. Notably, on the days with higher cumulative concentrations, PM1.0 (\(\beta\)=−1.34, 95% CI = −2.45, −0.23), PM2.5 (\(\beta\)=−1.28, 95% CI = −2.33, −0.23), PM10 (\(\beta\)=−1.28, 95% CI = −2.32, −0.24) exhibited a significant negative correlation with SDNN.

Linear regressions were adjusted for age, sex, BMI, respiration rate, smoking, alcohol consumption, METs, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, TVOC, humidity, and temperature. Boldface means significant results. β, regression coefficient; CI, confidence interval; PM, particulate matter; SDNN, standard deviation of NN intervals; SDNNI, mean of the standard deviations of all the NN intervals for each 5 min segment of a 24 h HRV recording; SDANN, standard deviation of the average NN intervals for each 5 min segment of a 24 h HRV recording; NN, normal-to-normal; RMSSD, root mean square of successive RR interval differences; RR, the time between successive R waves in an electrocardiogram (ECG), representing one cardiac cycle.

The overall effects exerted by the three daily average PMs (PM1.0, PM2.5, and PM10) were estimated using the BKMR method and stratified by days with higher and lower PM cumulative concentrations (Fig. 2). This regression model was adjusted for covariates including age, sex, BMI, respiration rate, smoking, alcohol consumption, METs, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, TVOC, humidity, and temperature on both the higher cumulative concentration day (Fig. 2a) and the lower cumulative concentration day (Fig. 2b). HRV (SDNN, SDANN, SDNNI, RMSSD) showed a negative trend as the degree of complex exposure increased. On days with higher cumulative concentrations, SDNN and the three daily average PMs showed a significantly negative association from the 70th to the 90th percentile compared with the 50th percentile of exposure levels. Significance was observed at the 90th percentile when the dependent variables were SDANN and SDNNI. Furthermore, when examining the exposure-response relationship on days with higher and lower cumulative concentrations, it was confirmed that an increase in the exposure levels of the three PMs was associated with a decrease in SDNN, SDANN, SDNNI, and RMSSD, demonstrating a negative trend (Supplementary Fig. 1).

The overall effect of the mixture (95% CI) is defined as the difference in the response when all of the exposures are fixed at a specific quantile (ranging from 0.10 to 0.90), as compared to when all of the exposures are fixed at their median value. a The day with the higher cumulative concentration of particulate matter. b The day with the lower cumulative concentration of particulate matter. Models were adjusted for age, sex, BMI, respiration rate, smoking, alcohol consumption, METs, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, TVOC, humidity, and temperature. CI, confidence interval; PM, particulate matter; SDNN, standard deviation of NN intervals; SDNNI, mean of the standard deviations of all the NN intervals for each 5 min segment of a 24 h HRV recording; SDANN, standard deviation of the average NN intervals for each 5 min segment of a 24 h HRV recording; NN, normal-to-normal; RMSSD, root mean square of successive RR interval differences; RR, the time between successive R waves in an electrocardiogram (ECG), representing one cardiac cycle.

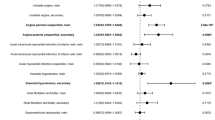

Table 3 presents the results of the subgroup analysis based on the chronic disease group (arrhythmia, chronic airway disease, stroke) and control group (higher air pollution exposed persons and older people). On days with higher cumulative concentrations, regression analysis was performed on the HRV for each environmental pollutant within each living labs, using age, sex, BMI, respiration rate, smoking, alcohol consumption, METs, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, TVOC, humidity, and temperature as adjustment variables. In both the chronic disease and control groups, each substance generally showed a negative correlation with HRV. In the chronic disease group, chronic airway disease showed a negative correlation with all HRV indices for daily average PM1.0, PM2.5, and PM10. In the control group, a negative association was observed between daily average PM1.0, PM2.5, and PM10 when the outcome was SDNN; higher air pollution exposed persons showed a significant negative correlation when SDNN was the outcome variable. On days with lower cumulative concentrations, exposure to PM substances generally demonstrated a negative trend with 24-h HRV, this was not statistically significant (Supplementary Table 3).

Subgroup and sensitivity analysis of the association between exposure to PM and HRV

A subgroup analysis was conducted on the complex exposure assessment for each living lab (Fig. 3). On days with higher cumulative concentrations, the three daily average PMs and SDNN showed a negative correlation at the 90th percentile of exposure compared with when all exposures were fixed at the 50th percentile in both the chronic disease and control groups. Additionally, in the chronic disease group, particularly among patients with chronic airway disease, SDNN significantly decreased when exposed to 3PMs at the 70th, 80th, and 90th percentiles compared to when all exposures were fixed at the 50th percentile. Similarly, in the control group, particularly among higher air pollution exposed persons, SDNN significantly decreased when exposed to 3PMs at the 70th, 80th, and 90th percentiles. On days with lower cumulative concentrations, complex exposure generally showed a negative trend with 24-h HRV; this was not statistically significant (Supplementary Fig. 2). The results of the sensitivity analysis demonstrate the robustness of the findings from the primary analysis. The LMM analysis evaluated the data without stratification and accounted for repeated measures, confirming that there was no temporal variability among participants or within the living lab groups (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5). The results from the regression (Supplementary Fig. 3, Supplementary Tables 6 and 7) and BKMR analyses (Supplementary Figs. 4, 5, and 6), which excluded potential confounders such as age, sex, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus, were consistent with the trends observed in the main analysis.

The overall effect of the mixture (95% CI) is defined as the difference in the response when all of the exposures are fixed at a specific quantile (ranging from 0.10 to 0.90), as compared to when all of the exposures are fixed at their median value. Models were adjusted for age, sex, BMI, respiration rate, smoking, alcohol consumption, METs, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, TVOC, humidity, and temperature. CI, confidence interval; PM, particulate matter.

Discussion

Vulnerable and susceptible individuals were recruited to evaluate the association between PM exposure and HRV. During the five-day measurement period, we differentiated between days with higher and lower cumulative concentrations to compare the associations between single-substance and complex-substance exposures. On days with lower cumulative concentrations of PM, we observed a negative trend without statistical significance; however, we observed a significant negative association on days with higher cumulative concentrations. In the overall study population, both single- and complex-substance exposure to daily average PM1.0, PM2.5, and PM10 presented a negative association with SDNN, consistent with previous studies that found that increased exposure to PM was associated with decreased HRV18,19. In the subgroup analysis by living labs, different associations were observed depending on the group. In the chronic disease group, PM exposure was associated with a decrease in SDNN among patients with chronic airway disease18, whereas in the control group, higher air pollution exposed persons showed an association between increased PM exposure and decreased SDNN19,20. However, unlike previous studies, we did not find an association between reduced HRV and PM exposure in patients with arrhythmia, stroke, or older people14,15,16,17. This discrepancy may be due to differences in population characteristics, study design, or environmental conditions. Additionally, the limited sample size and inherent variability within the small sample may have reduced the statistical power to detect a significant association, potentially contributing to the observed lack of association.

In this study, we highlight the importance of PM exposure in susceptible and vulnerable populations by building on previously explored aspects. First, most previous studies evaluated exposure using equipment located in urban areas, which cannot accurately reflect individual-specific information. We used equipment capable of measuring environmental pollutants, both indoors and outdoors, to assess personalized exposure levels in sensitive and vulnerable populations. At the same time, ECG signals were measured in real-time using devices that could monitor participants during the same period when environmental pollutants were being measured. This allowed for an accurate assessment of exposure levels based on the participants’ residential areas, indoor and outdoor environments, and lifestyle habits24. Beyond PM measurement, our equipment also recorded TVOC, temperature, and humidity, while the ECG monitoring devices provided data on respiration rate and metabolic equivalents (METs). This comprehensive data collection enabled us to control for individual characteristics as adjustment variables, thereby enhancing the precision and relevance of our findings29,30.

Second, after categorizing the exposure levels to environmental pollutants based on daily cumulative concentrations, we analyzed the data by comparing days with higher and lower cumulative concentrations. Interestingly, we found that the exposure levels on both higher and lower concentration days were still within the ‘good’ or ‘moderate’ categories as defined by the WHO31, the U.S. AQI32, and the Korean Ministry of Environment33 for daily average PM exposure (see Supplementary Table 2). Nevertheless, our findings clearly demonstrate that even lower PM levels of exposure significantly reduce HRV34 in higher-risk groups (chronic disease patients and industrial complex residents). Furthermore, we observed a stronger association with decreased HRV as the PM particle size decreased18,35. These findings underscore the necessity for more stringent, particle size-specific air quality standards for vulnerable individuals, compared to those for the general population.

Third, we assessed the impact of exposure to complex mixtures of PM, in addition to single substances, on HRV. This analysis revealed that the combination of PM particles of varying sizes had a more pronounced impact on HRV than single-substance exposures alone. In the overall study population, only SDNN was associated with single substance exposure; however, in the case of complex substance exposure, significant associations were observed not only with SDNN but also with SDANN and SDNNI. Notably, a negative association with SDNN was observed in both the overall chronic disease and control groups, with statistically significant associations generally observed at the 90th percentile of exposure. Although the daily average PM levels for both indoor and outdoor environments were within the globally recommended ‘good’ and ‘moderate’ categories31,32,33, our results suggest that individuals with sensitive characteristics may be more strongly affected by decreased HRV when exposed to a complex mixture of particles of varying sizes. These findings were made possible by the application of BKMR, a sophisticated statistical approach that allows for the modeling of high-dimensional and complex exposure-response relationships28. BKMR enabled us to simultaneously assess the effects of multiple pollutants, accounting for potential interactions between different PM sizes. This approach provided a more nuanced understanding of how combinations of pollutants, rather than individual substances alone, contribute to reductions in HRV. By capturing the non-linear and potentially synergistic effects of mixed-substance exposures, BKMR enhanced the accuracy and interpretability of our results, particularly in identifying the heightened vulnerability of certain populations to complex pollutant mixtures.

Fourth, we conducted analyses by separating the participants into groups based on specific diseases and vulnerable group characteristics. This approach demonstrated that the association between PM exposure and HRV can vary depending on factors such as medical history, age, and region of residence. Notably, patients with chronic airway disease and higher air pollution exposed persons demonstrated a strong negative association with SDNN in both single and mixed PM substance exposures. In particular, patients with chronic airway disease showed prominent associations across all HRV indices, indicating a heightened sensitivity to PM exposure in this group. These two groups were measured during the COVID-19 pandemic, when wearing masks was recommended outdoors, potentially resulting in lower outdoor exposure levels, with most measurements being taken indoors (Supplementary Table 2). These results may have influenced the observed associations, as reduced outdoor exposure could have altered the overall exposure, emphasizing the importance of indoor air quality. While this study did not specifically explore the mechanisms underlying the observed decrease in HRV due to PM exposure in these groups, it is plausible that higher air pollution exposed persons experience accumulated exposure due to their living environment. Similarly, patients with chronic airway disease who suffer from a progressive disease characterized by lung damage and inflammation due to particle and gas exposure may experience heightened inflammation during respiration, making PM exposure more impactful18. These findings suggest that targeted interventions, especially those aimed at reducing indoor PM exposure, may be necessary for individuals or groups with sensitive characteristics25,36.

Despite the advances reported in this study, several limitations must be addressed. First, the participants evaluated the HRV and PM exposures using electrocardiography (ECG) monitoring devices and a portable PM measurement device. Issues such as device compliance or discomfort during use can lead to errors in data measurements37. Supplementary Table 1 presents the range of missing rates for PM substances and ECG signals for study participants and excluded participants in each living lab. Over 90% of the missing data was due to participants’ unfamiliarity with using the devices or discomfort during use, resulting in an inability to measure. The remaining proportion was due to transmission errors when data from both devices were simultaneously uploaded to the server. The highest missing rates were observed in the higher air pollution exposed group and the older people group, which had the highest average ages. For PM substances, the environmental pollutant missing rate for most participants was less than 1%, but among the older people, the missing rate for environmental pollutants was up to 4.65% on higher cumulative concentration days and 9.44% on lower cumulative concentration days. The high missing rates on both higher and lower cumulative concentration days were from one participant, and excluding this participant, the maximum missing rate for other participants was below 3%. These missing values were replaced using the moving average method. For ECG signals, the missing rate for most participants was below 10%, although some participants in the higher air pollution exposed group and the older people group had higher missing rates. Efforts were made to correct these errors through interpolation and the removal of outliers. For participants with a missing rate between 5% and 10%, missing values were replaced using interpolation. For those with a slightly higher missing rate of 10% to 16.88%, data segments with severe missing rates were removed, outliers were eliminated, and then HRV was calculated. HRV for three participants with a missing rate exceeding 20% was excluded from the study because replacing missing values using various methods could compromise the reliability of the results. Despite preprocessing steps based on the degree of missingness, HRV values may still be overestimated compared to known HRV indices. Secondly, each living lab participant was evaluated at different time points. Specifically, higher air pollution exposed persons, arrhythmia patients, and patients with chronic airway disease were assessed during the COVID-19 pandemic. As mask-wearing was recommended both indoors and outdoors during this period, the inhalation of environmental pollutants may have been reduced38. As a result, unlike previous studies, we only observed a trend of decreased HRV with PM exposure in patients with arrhythmia, without statistically significant results16,17. Third, our evaluation of 24-h HRV based on daily exposure likely integrated various physiological responses occurring under different conditions throughout the day. Although this averaging approach stratified the data by days of higher and lower cumulative exposure, the use of daily average values may have obscured the precise effects of indoor and outdoor exposure from the exposure variable perspective, as well as the differences in HRV between resting and active periods from the outcome variable perspective. Fourth, our study had limitations related to the small sample size and sample size variability. Statistically, a limited sample size can decrease the power to detect significant associations, increasing the likelihood of type II errors. This means that even if a true association exists between PM exposure and reduced HRV, the small sample may have rendered us less able to observe this effect reliably. Moreover, the variability in exposure measurements and individual physiological responses may have contributed to the absence of statistically significant findings among patients with arrhythmia, stroke, and older people. These variations could have masked potential associations between PM exposure and HRV in these vulnerable subgroups. Our study analyzed data continuously measured in a small group, stratified by higher and lower cumulative concentrations. We recognize that presenting results based on stratified analyses over five days could be seen as failing to account for between-subject variability and temporal variability. To address, at least in part, the challenges posed by the small sample size and its variability, we additionally performed an LMM analysis (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5), which presented no significant temporal variability, justifying our approach of stratifying by cumulative exposure days without separate repeated-measures adjustments. Importantly, this analysis confirmed that the significant associations observed for PM exposure and HRV in our primary regression and BKMR analyses were consistent even after accounting for repeated measures. However, the lack of significant findings among patients with arrhythmia, stroke, and older people remained unchanged in the LMM analysis. Notably, for the older people, PM exposure showed associations with SDNN that approached statistical significance, suggesting that the impact of PM on HRV in this group may warrant further investigation. Therefore, future studies with larger sample sizes or datasets designed to better account for repeated measures are necessary to confirm these findings and explore the potential subtle effects of PM exposure in vulnerable populations.

With these limitations in mind, future research should focus on disentangling the variables influencing HRV by separately analyzing responses to indoor and outdoor PM exposures and examining HRV variations during activity and rest. This would provide a clearer understanding of how environmental contexts and daily routines impact HRV, enabling more targeted interventions. Additionally, exploring the biological mechanisms underlying the significant associations found in vulnerable groups is crucial for understanding the long-term health implications of PM exposure. Moreover, longitudinal studies incorporating repeated measurements over extended periods are essential to move beyond mere associations and toward causal inference. By capturing the chronic impacts of PM exposure on HRV over time, such studies would enhance our understanding of the enduring effects of air pollution on cardiovascular health, ultimately supporting the development of more effective public health policies and interventions.

Overall, we found that increased exposure to PM was associated with decreased HRV, and this relationship varied depending on the sensitive characteristics of the individuals. The data with the integration of indoor and outdoor personalized exposure assessments with 24-h ECG monitoring has enhanced our understanding of the complex interactions between PM and health. Furthermore, by demonstrating that even lower levels of PM exposure, as defined by global standards, can have detrimental effects on HRV, our findings suggest that existing thresholds may not adequately protect sensitive individuals. This underscores the need for more stringent, particle size-specific standards tailored to these at-risk groups.

Methods

Study participants

This study established living labs to assess personalized exposure in patients with environmental diseases and vulnerable populations. The living lab participants were recruited from a pre-established cohort. The environmental disease cohort includes cardiovascular, respiratory, and neurological disease groups, while the vulnerable population cohort includes industrial complex residents and older individuals. The cardiovascular disease cohort contains patients who have visited hospitals as acute stroke patients since 2016 (N = 350), the respiratory cohort contains patients who have visited for COPD, asthma, or bronchiectasis since 2018 (N = 500), and the neurological cohort includes patients with atrial fibrillation or implanted cardiac devices since 2016 (N = 300). In the vulnerable population cohort, the industrial complex resident cohort includes individuals who have lived in industrial areas since 2014 (N = 150) and individuals who have lived near thermal power plants since March 2021 (N = 500). The elderly cohort comprises individuals aged 60 years or older without severe chronic diseases (N = 1310). Living lab participants were recruited from five established cohorts, with 20 individuals from each cohort who voluntarily consented to participate in managing their health through exposure to environmental pollutants and digital biomarker measurements.

In this study, patients with environmental diseases are designated as the chronic disease group (arrhythmia, chronic airway disease, stroke), and the vulnerable populations are referred to as the control group (higher air pollution exposed persons, older people) in five living lab groups. The study was conducted from April 2021 to July 2023. Participants for the living labs were recruited from the start of the study, and measurements of environmental pollutants and biosignals were taken for each living lab once recruitment was complete. Therefore, the measurement periods varied across the different living labs. The living labs for the higher air pollution exposed persons were conducted from December 2021 to February 2022; from June to August 2022 for the arrhythmia group; from October to November 2022 for the chronic airway disease group; in June 2023 for the older people group; and in July 2023 for stroke group. The arrhythmia group consisted of patients aged 20 years or older who visited the cardiology department at Kyung Hee University Hospital in Seoul and were diagnosed with atrial fibrillation using International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10 codes) I48.0, I48.1, or I48.2. These patients had either atrial fibrillation or those with implanted cardiac electrical devices (such as permanent pacemakers or implantable defibrillators) (N = 20). The chronic airway disease group included patients who visited the pulmonology department at Severance Hospital in Seoul and Wonju Severance Christian Hospital in Wonju. Patients diagnosed with COPD, asthma, or bronchiectasis using ICD-10 codes J44 or J45 (N = 20). COPD patients were clinically consistent with COPD and met diagnostic criteria based on pulmonary function (FEV1/FVC < 0.7, FEV1 < 80% of predicted value). Asthma patients were individuals clinically diagnosed with asthma who were using inhaled medications, and bronchiectasis patients had one or more lobes with bronchiectasis confirmed by chest CT. The stroke group consisted of patients aged 20 years or older who visited the neurology at Gachon University Medical Center in Incheon and were diagnosed with ischemic stroke using ICD-10 code I63. These were acute stroke patients who were admitted to the hospital within seven days of symptom onset (N = 20). The old people group included individuals aged 60 years or older, residing in Seoul or Incheon, without severe chronic diseases or cognitive impairments (N = 20). The higher air pollution exposed persons group were individuals without severe chronic diseases or neurological conditions such as dementia or stroke, residing in industrial areas (N = 20). The higher air pollution exposed person group lived within a 5–15 km radius of the Namdong Industrial Complex in Incheon or thermal power plants in Gyeongsangnam-do (Fig. 4). A total of 100 individuals were recruited from sensitive and vulnerable living laboratories. Due to device compliance issues, three participants with high missing rates were excluded from the analysis, resulting in the analysis of data from 97 participants (Supplementary Table 1). This study was approved by the Clinical Trial Review Committee of the Yonsei University Wonju Severance Christian Hospital (approval number: CR321068). To use the data from the recruited participants, approvals were obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Severance Hospital (4-2021-0550, 4-2021-0852), Kyung Hee University Hospital (KNUH 2021-07-074-001), Gachon University Gil Medical Center (GIRB-2021-351), and Gyeongsang National University (GIRB-A21-Y-0053).

Details of recruitment and measurement locations for living lab participants are displayed on a map of South Korea, marked with red and blue points. Red points indicate living labs for the chronic disease group, and blue points represent living labs for the control group. The recruitment criteria for each living lab participant are described within the box for each respective living lab.

Data collection

Demographic and clinical data of the participants, including age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, and medical history, were obtained at the time of participant registration. Each participant visited their respective hospital once a year over three years. The chronic disease group (arrhythmia, chronic airway disease, stroke) was monitored at the hospitals the participants visited, and the control group (higher air pollution-exposed individuals, older people) was followed up by the departments of preventive medicine at Gyeongsang National University and Yonsei University. During each visit, the participants were assessed for personal health examination information, hospital visit history, and other relevant data. A personalized exposure assessment was conducted to measure the exposure levels of environmental pollutants and digital biomarkers in various microenvironments where the participants spent time tailored to their daily living patterns (Supplementary Table 2). The total measurement period was five days. The research participants met in person on the first day of the measurement, and the necessary measuring equipment was provided. Participants carried the equipment during their daily activities. The research team visited the participants daily to check the equipment status to ensure consistency in the measurements. A daily activity log was provided to the participants at the initial meeting to record their daily living patterns, and they were instructed to fill it out each day. The quality of the daily activity logs was reviewed during the daily visits. If the quality was found to be low, participants were interviewed about their activities from the previous day to make necessary corrections. Because physical activity intensity can act as a moderating variable affecting the level of PM exposure, an accelerometer was provided to measure the metabolic equivalent of task (MET) with the participants’ consent, excluding periods of showering and sleeping. Digital biomarkers were measured using ECG monitoring during the same period as environmental pollutants were measured, and the participants wore the device continuously unless a device malfunction occurred. The researchers continuously monitored the environmental pollutant data and physiological signals, and they managed the situation by contacting the participants by phone if data were not received. Demographic and clinical data information was defined as follows: Smoking status was based on a lifetime history of smoking at least five packs (100 cigarettes) (yes/ex-smoker/no). Alcohol consumption was defined by frequency over the past year (less than once a month/once a month/2–3 times a month/once a week/2–3 times a week/4 times a week/never). Hypertension and diabetes mellitus were based on past diagnoses (yes/no).

Assessment of exposures

Environmental pollutant data were measured using a lightweight portable device, AIR HEART-P21 (manufactured by ZINIDE, South Korea), which allows for real-time measurements every minute using a light scattering method. The PM sensor has a measurement range of 5–200 µg/m³ (minimum unit: 1 µg/m³), with repeatability over 80% in chamber tests, accuracy above 80%, and precision above 80% in field tests. This device is certified as the highest grade by the Korean Ministry of Environment. The device measured PM1.0 (aerodynamic diameters <1 μm), PM2.5 (aerodynamic diameter ≥1 μm and <2.5 μm), PM10 (aerodynamic diameter ≥2.5 μm and <10 μm), TVOC (total volatile organic compounds), temperature, and humidity. In cases where missing values occurred in the measured data, a moving average was used to maintain the temporal continuity of the data and reflect its variability patterns. The moving average method fills in missing values using the average of surrounding data, which helps maintain relatively smooth changes even when the data has high variability39. The data collected over five days, based on individual daily activity patterns, were compared with 24-h HRV associated with short-term exposure. To compare with 24-h HRV, PM concentrations measured per 1-min were converted into 24-h values, and the concentrations of PM were calculated as 24-h cumulative values and 24-h averages. While average concentrations can be used to distinguish between the highest and lowest concentration days, averaging daily concentrations may dilute the impact of short-term high exposure levels, potentially leading to incorrect data classification. Considering these points, we used the 24-h cumulative concentration to identify the days with the higher and lower cumulative PM concentrations. The start and end times of the measurements varied although data were collected over five days for each individual. Consequently, the first and last days, when the measurement durations were shorter, fell under the days with the lowest PM concentrations. To address this, the values from the first and last days were excluded and only data from the three middle days were used to differentiate between days with higher and lower cumulative PM concentrations. On the other hand, the 24-h average PM concentrations were used for analysis. Using cumulative PM concentrations for analysis can complicate the interpretation of results and may be sensitive to outliers. Therefore, for intuitive interpretation and statistical robustness, we used the 24-h average PM concentrations for data analysis.

ECG monitoring

Physiological signals were measured using the HiCardi SmartPatch (SW 1.101), a two-electrode patch manufactured by Mezoo Co. Ltd (RM.808 200, Gieopdosi-ro, Jijeong-myeon, Wonju-si, Gangwon-do, Republic of Korea)40. The HiCardi device records 15,000 data points per minute at a frequency of 250 Hz. This wearable device can monitor and record various parameters related to cardiac signals, such as single-lead ECG, heart rate, respiration, skin surface temperature, and activity. It is equipped with specifications to provide accurate health monitoring data. This device is certified by the Korea Food and Drug Safety Agency and captures ECG signals at a sampling frequency of 250 Hz, with a resolution of 14 bits. The heart rate (HR) range of the device is from 0 to 300 beats per minute (bpm), with a precision of ±2 bpm or ±2%, whichever is greater. The temperature monitoring range is from 32 °C to 43 °C, with an accuracy of ±0.3%. It also provides respiration rate measurements ranging from 5 to 60 breaths per minute or up to 120 breaths per minute, maintaining an accuracy of ±2 bpm or ±2%. All collected data were then forwarded to a cloud-based monitoring server through the mobile gateway. After obtaining informed consent from all participants, the wearable patch was affixed to the left sternal border, and continuous recording of ECG signals and other data ensued. However, segments in which measurements were not possible due to poor contact or out-of-range Bluetooth communication were excluded. Among the various methods for defining HRV, we excluded frequency-domain segments that could not be synchronized with the PM data. We evaluated HRV using the standard deviation of normal-to-normal intervals (SDNN), standard deviation of the average NN intervals for each 5-min segment of a 24-h HRV recording (SDANN), mean of the standard deviations of all NN intervals for each 5-minute segment of a 24-h HRV recording (SDNNI), and root mean square of successive RR interval differences (RMSSD)41. As the cumulative concentration of PM was evaluated daily, HRV was calculated over 24 h, and three preprocessing steps were required to derive HRV from the ECG signals. First, outliers corresponding to extreme values due to device compliance or measurement errors were removed. Second, noise in the signal, which would obscure the identification of the R-peaks necessary for calculating the HRV, was removed using a bandpass filter42. Third, missing values are replaced using interpolation methods43.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are described as totals and percentages. Continuous variables are summarized as means and standard deviations or medians with minimum and maximum values. The independent t-test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test was used to compare the baseline characteristics of PM based on the cumulative concentration and HRV. We used two models to investigate the association between PM exposure and HRV. Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to examine the effects of single-substance exposure and PM particle size on HRV. Daily average PM1.0, PM2.5, and PM10 were the primary exposure variables, and age, sex, BMI, daily average respiration rate, smoking, alcohol consumption, METs, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, daily average TVOC, humidity, and temperature were used as adjustment variables.

Since individuals are exposed to a mixture of substances rather than a single one, we used the BKMR model to assess the effects of mixed-substance exposure. BKMR is a flexible statistical method that allows the assessment of individual and joint effects of exposure mixtures. It also accounts for the exposure-response relationships for each component of the mixture, while identifying potential interactions using kernel functions28. The BKMR was used to assess the combined effect of multiple PM pollutants. Daily average PM1.0, PM2.5, and PM10 were included as nonlinear terms within the kernel function h(Z) to examine their joint effects. Age, sex, BMI, daily average respiration rate, smoking, alcohol consumption, METs, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, daily average TVOC, humidity, and temperature, having a confirmed linear relationship with HRV, were treated as linear terms and included as adjustment variables in the model. All air pollution variables were standardized to z-scores. All BKMR models were run with the Markov Chain Monte-Carlo (MCMC) sampler for 10,000 iterations after a burn-in of 2000–5000. A sufficient number of iterations is required to ensure that the MCMC samples adequately represent the characteristics of the distribution. We used trace plots to check for convergence and ensure the stability of the estimates. To investigate the overall effect, BKMR compares the HRV from all PM mixtures set to a specific percentile with the HRV when all PM exposures are fixed at their median value. The individual effects of substances are visualized through the exposure-response relationship, presenting the univariate relationship between each PM exposure and the HRV, when all the other exposures are fixed at their median values. We conducted three analyses using both statistical analysis methods. First, a stratified analysis was conducted across all study participants based on days with higher and lower cumulative PM concentrations. Second, a subgroup analysis was performed within the five living labs, divided into the chronic disease group (arrhythmia, chronic airway disease, stroke) and the control group (higher air pollution-exposed persons, older people). Third, a sensitivity analysis was performed to ensure the reliability of the results.

We conducted sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of our findings. First, we performed regression and BKMR analyses using data collected continuously over five days. Since the data for each participant was measured continuously over this period, repeated measures needed to be accounted for. Nevertheless, because we stratified the data by day with higher and lower cumulative concentrations, we needed to explain why repeated measures were not considered in the main analyses. To address this, we conducted a linear mixed effect model (LMM) analysis. The LMM included each PM concentration and time stratified by high and low cumulative PM days as fixed effects, with participants included as random effects to account for within-subject correlation. The analysis was performed separately for the total population, the chronic disease group, the control group, and each living lab, similar to the other two analysis methods. Second, we reperformed the regression and BKMR analyses by excluding potential confounders, including age, sex, BMI, smoking status, alcohol consumption, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus. The impact of these exclusions on the results was assessed by comparing the direction and significance of the associations between PM exposure and HRV metrics. We preprocessed ECG signals using the SciPy library with Python (version 3.8.13), conducted summary statistics, regression, and LMM analysis with SAS (version 9.4; SAS, Cary, NC, USA), and used R (version 4.03; Institute for Statistics and Mathematics, Vienna, Austria; http://cran.rproject.org) with the bkmr package to implement the BKMR model.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article [and its supplementary information files].

Code availability

The underlying code for this study is not publicly available but may be made available to qualified researchers on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Brook, R. D. et al. Particulate matter air pollution and cardiovascular disease: an update to the scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 121, 2331–2378 (2010).

Gold, D. R. & Mittleman, M. A. New insights into pollution and the cardiovascular system: 2010 to 2012. Circulation 127, 1903–1913 (2013).

Pope III, C. A. et al. Cardiovascular mortality and long-term exposure to particulate air pollution: epidemiological evidence of general pathophysiological pathways of disease. Circulation 109, 71–77 (2004).

Taneepanichskul, N. et al. Short-term effects of particulate matter exposure on daily mortality in Thailand: a case-crossover study. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 11, 639–647 (2018).

Pieters, N. et al. An epidemiological appraisal of the association between heart rate variability and particulate air pollution: a meta-analysis. Heart 98, 1127–1135 (2012).

Araujo, J. A. Particulate air pollution, systemic oxidative stress, inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 4, 79–93 (2011).

Brook, R. D. et al. Air pollution and cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the Expert Panel on Population and Prevention Science of the American Heart Association. Circulation 109, 2655–2671 (2004).

Rajagopalan, S. & Brook, R. D. Air pollution and type 2 diabetes: mechanistic insights. Diabetes 61, 3037–3045 (2012).

Peng, C. et al. Particulate air pollution and fasting blood glucose in nondiabetic individuals: associations and epigenetic mediation in the normative aging study, 2000–2011. Environ. Health Perspect. 124, 1715–1721 (2016).

Electrophysiology, Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology the North American Society of Pacing. Heart rate variability: standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clinical use. Circulation 93(5), 1043–1065.

Kleiger, R. E., Miller, J. P., Bigger Jr, J. T. & Moss, A. J. Decreased heart rate variability and its association with increased mortality after acute myocardial infarction. Am. J. Cardiol. 59, 256–262 (1987).

Bigger Jr, J. T. et al. Frequency domain measures of heart period variability and mortality after myocardial infarction. Circulation 85, 164–171 (1992).

Tsuji, H. et al. Impact of reduced heart rate variability on risk for cardiac events: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 94, 2850–2855 (1996).

Creason, J. et al. Particulate matter and heart rate variability among elderly retirees: the Baltimore 1998 PM study. J. Exposure Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 11, 116–122 (2001).

Park, S. K., O’Neill, M. S., Vokonas, P. S., Sparrow, D. & Schwartz, J. Effects of air pollution on heart rate variability: the VA normative aging study. Environ. Health Perspect. 113, 304–309 (2005).

Zanobetti, A. et al. Reduction in heart rate variability with traffic and air pollution in patients with coronary artery disease. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 324–330 (2010).

Huang, W. et al. Air pollution and autonomic and vascular dysfunction in patients with cardiovascular disease: interactions of systemic inflammation, overweight, and gender. Am. J. Epidemiol. 176, 117–126 (2012).

Pan, L. et al. The short-term effects of indoor size-fractioned particulate matter and black carbon on cardiac autonomic function in COPD patients. Environ. Int.112, 261–268 (2018).

Cavallari, J. M. et al. Time course of heart rate variability decline following particulate matter exposures in an occupational cohort. Inhal. Toxicol.20, 415–422 (2008).

Riediker, M. et al. Cardiovascular effects in patrol officers are associated with fine particulate matter from brake wear and engine emissions. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 1, 1–10 (2004).

Baig, N. A. et al. Association between traffic emissions mixed with resuspended dust and heart rate variability among healthy adults in Delhi. Air Qual. Atmos. Health 13, 371–378 (2020).

Chuang, K.-J., Chan, C.-C., Chen, N.-T., Su, T.-C. & Lin, L.-Y. Effects of particle size fractions on reducing heart rate variability in cardiac and hypertensive patients. Environ. Health Perspect. 113, 1693–1697 (2005).

Gold, D. R. et al. Ambient pollution and heart rate variability. Circulation 101, 1267–1273 (2000).

Klepeis, N. E. et al. The National Human Activity Pattern Survey (NHAPS): a resource for assessing exposure to environmental pollutants. J. Exposure Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 11, 231–252 (2001).

Hansel, N. N. et al. Randomized clinical trial of air cleaners to improve indoor air quality and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease health: results of the CLEAN AIR study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 205, 421–430 (2022).

Hu, J. et al. Fine particulate matter constituents and heart rate variability: a panel study in Shanghai, China. Sci. Total Environ. 747, 141199 (2020).

Peralta, A. A., Schwartz, J., Gold, D. R., Coull, B. & Koutrakis, P. Associations between PM2. 5 metal components and QT interval length in the Normative Aging Study. Environ. Res. 195, 110827 (2021).

Bobb, J. F. et al. Bayesian kernel machine regression for estimating the health effects of multi-pollutant mixtures. Biostatistics 16, 493–508 (2015).

Weis, B. K. et al. Personalized exposure assessment: promising approaches for human environmental health research. Environ. Health Perspect. 113, 840–848 (2005).

Choi, H. M. & Bell, M. L. Heat-mortality relationship in North Carolina: Comparison using different exposure methods. J. Exposure Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 33, 637–645 (2023).

World Health Organization. Air quality guidelines: global update 2005: particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, and sulfur dioxide. (World Health Organization, 2006).

Plaia, A. & Ruggieri, M. Air quality indices: a review. Rev. Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 10, 165–179 (2011).

Ministry of Environment. Annual Report of Ambient Air Quality in Korea. (Ministry of Environment Seoul, 2010).

Niu, Z. et al. Acute effect of ambient fine particulate matter on heart rate variability: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis of panel studies. Environ. Health Prevent. Med. 25, 1–15 (2020).

Huang, C. et al. Particulate matter air pollution and reduced heart rate variability: how the associations vary by particle size in Shanghai, China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 208, 111726 (2021).

Kim, H. et al. The impact of life behavior and environment on particulate matter in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Environ. Res. 198, 111265 (2021).

Kwon, S. et al. Validation of adhesive single-lead ECG device compared with holter monitoring among non-atrial fibrillation patients. Sensors 21, 3122 (2021).

Langrish, J. P. et al. Beneficial cardiovascular effects of reducing exposure to particulate air pollution with a simple facemask. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 6, 1–9 (2009).

Saeipourdizaj, P., Sarbakhsh, P. & Gholampour, A. Application of imputation methods for missing values of PM10 and O3 data: Interpolation, moving average and K-nearest neighbor methods. Environ. Health Eng. Manag. J. 8, 215–226 (2021).

Park, Y. et al. Development and validation of a real-time service model for noise removal and arrhythmia classification using electrocardiogram signals. Sensors 24, 5222 (2024).

Stein, P. K., Bosner, M. S., Kleiger, R. E. & Conger, B. M. Heart rate variability: a measure of cardiac autonomic tone. Am. Heart J. 127, 1376–1381 (1994).

Fischer, S. E., Wickline, S. A. & Lorenz, C. H. Novel real-time R-wave detection algorithm based on the vectorcardiogram for accurate gated magnetic resonance acquisitions. Magn. Reson. Med. 42, 361–370 (1999).

Ishaque, S., Khan, N. & Krishnan, S. Trends in heart-rate variability signal analysis. Front. Digital Health 3, 639444 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Korea Environment Industry & Technology Institute (KEITI) through the Digital Infrastructure Building Project for Monitoring, Surveying, and Evaluating Environmental Health funded by the Korea Ministry of Environment (MOE) (RS-2021-KE001338 and 2021003340002). Also, we would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.W.J. and D.R.K. designed the study. Y.L. and J.Y.J. collected data. Y.W.J. and Y.P. conducted data analyses. Y.W.J. and H.M.C. drafted the manuscript, with further development by J.Y.J. and D.R.K., J.Y.J. and D.R.K. supervised the study. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript and approval of the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jeong, Y.W., Choi, H.M., Park, Y. et al. Association between exposure to particulate matter and heart rate variability in vulnerable and susceptible individuals. npj Digit. Med. 8, 52 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01373-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-024-01373-5