Abstract

Therapeutic toxicity, which can be life-threatening, presents a major challenge in treating patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML). Medical digital twins, which are virtual representations of patient disease, have the potential to forecast disease progression and simulate potential treatments. Using neutrophil counts and blast percentages, we developed mechanistic models to predict toxicity (neutropenia) in AML patients receiving combination venetoclax and azacitidine treatment. We identified a best-fitting model, though patient-specific accuracy was highly variable. To address this variability, we investigated subsets of patients based on their accordance with model assumptions, and were able to identify features predictive of model fit. In addition, we found that continuous updating over time improves model accuracy. The model evaluated in this study could be further validated in a larger clinical setting and may support a digital twin for decision making in forecasting therapeutic toxicity of venetoclax and azacitidine treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a hematological malignancy with high molecular heterogeneity and varied responses to treatment1,2. Resistance to current standard therapeutic regimens and toxicity is an obstacle for the successful treatment of patients with AML3,4,5, who have a low 5-year overall survival rate (32.9% in the US from 2015–2021)6. Common adverse events (toxicity) in AML treatment include neutropenia and thrombocytopenia7. Neutropenia is often accompanied by recurrent infections, which may cause physicians to modify or discontinue treatment. Neutropenia, which is the main focus of this work, can be caused by AML, due to the disruption of healthy bone marrow function, as well as by AML treatment8. Severe neutropenia is defined as a circulating neutrophil count of less than 0.5 * 109 cells per liter9. Recently, the combination of the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax with the hypomethylating agent azacitidine has become the standard of care for AML patients unfit for intensive chemotherapy. However, the incidence of febrile neutropenia is higher in patients treated with venetoclax-azacitidine compared to those receiving azacitidine monotherapy7. Prolonged neutropenia often necessitates modifications or discontinuation of the treatment7. To improve treatment outcomes, enhanced disease monitoring and adjustable treatment schedules are needed.

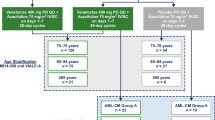

A clinical trial (VenEx, NCT04267081)10,11 has been carried out by the Finnish AML Group with comprehensive molecular and clinical data generated for patients treated with venetoclax and azacitidine. This trial includes two groups of patients: patients with de novo AML who were ineligible for standard chemotherapy, and patients with previously treated secondary AML or recurrent or relapsed AML. A key feature of this clinical study is that beyond the measurement of genetic information at diagnosis, the clinical study provides longitudinal measurements of clinical features such as blast percentages, leukocyte and neutrophil counts, along with corresponding treatment schedules and drug dosages. This dataset offers a unique opportunity to develop and fit patient-specific mathematical models, and to incorporate patient response and adverse events over time, providing a rich resource to develop prototypes for AML digital twins.

The core components of a digital twin system are a set of predictive mathematical models that are virtual representations of the structure, context, and behavior of a natural, engineered, or social systems12,13. A digital twin model is continuously updated with data from its physical twin, and has a predictive capability and the ability to inform decision-making12,13. As applied to medicine, the digital twin is a virtual representation of a patient’s disease that is updated using new patient data, for example from wearables, medical devices, diagnostic tests, and electronic health records, to adjust treatment, monitor response, and track lifestyle modifications14,15. This enables the prediction of disease progression, optimization of care delivery, and improvement of outcomes16. Digital twin examples from the healthcare domain include an artificial pancreas capable of forecasting hypo- and hyperglycemic events17,18, a chronic wound management system19 and a predictor for neurocardiac modulation20. Many other examples are provided in review papers21.

When constructing disease digital twins, key decisions include the choice of virtual representation, model construction, and the method of model update with new patient-specific data. Patient-specific models are a key potential benefit of medical digital twins for diseases such as cancer, where significant patient to patient heterogeneity can confound treatment selection. In the context of AML, blast percentages and neutrophil counts are critical clinical measurements to estimate the disease progression and treatment toxicity, and thus models that incorporate these measurements are advantageous as components in digital twins for AML patients for the goal of predicting toxicity or disease progression. Many AML models have been developed, such as the models of Stiehl et al. describing the growth of healthy hematopoietic stem cells and leukemic stem cells22,23, the models of Jost et al. for the effects of cytarabine in AML treatment on white blood cell levels24,25, and the models for AML treatment and progression from Banck et al.26 and Hoffmann et al.27 These models are semi-mechanistic and employ ordinary differential equations (ODEs). They are a good choice for the digital twin system, as they can incorporate known mechanisms in AML, can be readily adapted to the current context (blast percentage, neutrophil counts and patient-specific modeling), are able to make predictions beyond the data acquisition timeframe, and have computational runtimes that are compatible with use in a clinical setting. Other models in the literature involve hematopoiesis, leukemia, and chemotherapy dynamics and are described by stochastic systems, partial differential equations, or delay differential equations28,29,30.

In this work, we implemented ODE-based dynamical models as part of an AML digital twin system to monitor and predict the toxicity (in terms of neutropenia) resulting from treatment with venetoclax and azacitidine and from AML progression. The dynamic models were fitted on longitudinal measurements (both neutrophil counts and blast percentages) from the VenEx clinical trial. The models showed utility in both representing patterns present in the neutrophil/blast trajectories and in predicting future trajectories for neutrophil counts during the course of venetoclax/azacitidine treatment. In addition, we identify the clinical features that are most predictive of the ability of models to fit the data. These models provide key elements for a future AML digital twin system.

Results

Overview of the mathematical models

The models were primarily adapted from the mathematical models developed by Jost et al.24,25, which were in turn adapted from a model developed by Friberg et al. in 200231. The Jost et al. models investigated individualized prediction of white blood cell (WBC) count dynamics during treatment with cytarabine in AML24,25. In this work, we modified and extended these models to predict blast percentage and neutrophil counts during the treatment of venetoclax and azacitidine using time course measurements for AML patients in the VenEx clinical trial (NCT04267081)10,11. This trial includes two groups of patients: patients with de novo AML who were ineligible for intensive chemotherapy, and patients who had recurrent, relapsed, or previously treated secondary AML. Data from this trial include treatment schedules for the administration of venetoclax and azacitidine, and longitudinal neutrophil and bone marrow blast measurements.

We explored a set of models which varied in three ways: (1) how drug effects are represented, (2) what affects neutrophil populations, and (3) how blast growth is modeled (see columns in Table 1). Figure 1a illustrates the model components and interactions in the models. These are semi-mechanistic models that aim to simulate the effect of venetoclax and azacitidine on the percentage of blast cells in the bone marrow and neutrophil counts in circulating blood. The key assumption of all of the models is that venetoclax/azacitidine treatment inhibits the production of neutrophils by inhibiting the proliferation of healthy hematopoietic cells. Another assumption shared by some of the models is that blasts in the bone marrow also inhibit the proliferation and differentiation of healthy hematopoietic cells. The three components of the models are described below.

a A simplified overview schematic of the ODE toxicity models. Each dotted line box represents a compartment; black arrows represent growth or transitions, while red square-ended arrows represent repression. The labels (1), (2), and (3) indicate the drug effect, healthy neutrophil, and blast components, respectively (described in the main text). b An example of the results of fitting Model 2c (M2c) on the data for one patient. The blue curves represent the model simulation, while the blue points represent measurements. Green and Yellow colors represent azacitidine and venetoclax treatment cycles, respectively. This example has a FVU (fraction of variance unexplained) of about 0.23. c The distributions of FVU values for different models after fitting to 71 AML patients. d FDR-corrected p values for differences in FVU between models, calculated using a one-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test, testing for the row being less than the column in FVU.

Drug effects were modeled using two different approaches. The first approach involves a simple proportional effect during venetoclax and/or azacitidine treatment cycles. For venetoclax, the drug effect is constant during the treatment cycle and proportional to the drug dosage, and zero outside the treatment cycle. For azacitidine, the drug effect is activated and proportional to the dosage for a portion of each day during the treatment cycle to represent the subcutaneous injection and rapid decay, and zero outside the treatment cycle. The second approach involves pharmacokinetic models of both drugs. The venetoclax component was based on the three-compartment model of Dave et al.32, with the parameters set to the population medians from this model. Drug administration is modeled with a single oral dose per day of the treatment cycle. The azacitidine component is a one-compartment model based on the parameters of Macbeth et al.33.

For the neutrophil component, we started with the model of Jost et al.24, which has three compartments representing stages of hematopoiesis—healthy proliferating cells, transitional cells, and white blood cells in circulating blood. We used neutrophils in place of circulating white blood cells. The first compartment contains proliferating cells in the bone marrow (that is, cells capable of self-renewal, including hematopoietic stem cells and granulocyte progenitor cells, the latter of which are known to be negatively affected by venetoclax34). Transitional cells represent precursor cells committed to neutrophil fate. In some models, we also added components to represent inhibitory effects of leukemic blasts on neutrophil production—either a direct inhibition effect where high blast counts inhibit transition through the neutrophil lineage, or a carrying capacity effect where there is an inhibition effect dependent on the sum of healthy proliferating cells and blasts (based on the model of Stiehl et al.18). We included these components after observing a negative correlation between neutrophil count and blast percentage in most patients. Previous experimental results also indicate that leukemic blasts can inhibit healthy hematopoiesis28.

The blast component is based on another model of Jost et al.25, which was in turn based on the “cytokine-dependent” model of Stiehl et al.22. This component has two compartments, blasts in the bone marrow and blasts in circulating blood. We also implemented a blast component with a carrying capacity based on the sum of healthy proliferating cells and leukemic blasts, as well as a more explicit logistic growth model.

Table 1 lists all the models that have been implemented and their main characteristics. A detailed description of the models including their mathematical formulation can be found in the “Methods” section.

In order to establish a baseline comparison to our ODE-based dynamical models, we also implemented a linear regression model for predicting the neutrophil count at the next time point given the measurements at the current time point. This model takes into account the same basic assumptions as the ODE models, that both venetoclax treatment and blast levels have an effect on neutrophil counts. Details about the regression model and its variables are described in the “Methods” section.

Model fitting results

First, we selected all patients with at least three treatment cycles for modeling, resulting in 71 patients (see "Methods" for patient selection). For each model, we attempted to fit the model to each patient’s neutrophil counts and blast percentages. Models were fit using a maximum a posteriori approach in order to find the parameter estimates with the greatest log-likelihood of the observed data. More details on model fitting are described in the “Methods” section. An illustration of fitted results from one AML patient is shown in Fig. 1b.

To compare the results across different models and patients, we used two metrics: the fraction of variance unexplained (FVU), which is calculated as \(1-{R}^{2}\), where \({R}^{2}\) is the coefficient of determination between the model prediction and the observed data, and the root mean square error (RMSE), which is calculated as the square root of the sum of squared differences between the model prediction and the observed data (see the “Statistical analysis” subsection in “Methods” for more details). Because patients have different ranges for their neutrophil counts, FVU can be a better control compared to using RMSE when making comparisons across patients.

Of all the models that we compared, including the linear regression model, M2c had the best performance across all patients for the prediction of neutrophil counts based on the FVU (Fig. 1c), with a median FVU of about 0.46. This model had a simplified (on-off) drug component, a neutrophil component that included direct inhibition from blasts, and a simplified blast model with logistic growth. M2b_w had a similar overall performance as model M2c, with a non-significant difference in performance. The other models had higher errors, with the median FVU around 0.7–0.8. To compare performance across models, we used a one-sided pairwise Wilcoxon signed-rank test of FVUs for all patients with each pair of models followed by a false discovery rate correction (Benjamini–Hochberg procedure). The results showed that models M2c and M2b_w had significantly lower FVUs compared to all other models (Fig. 1d). Results for RMSE comparisons are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1. In terms of RMSE, we found that M2c, M2b_w, and M1b_w had similar performances, and were significantly better compared to other models. Comparing M2c with the linear regression model, we found that M2c had significantly lower FVU and RMSE (Supplementary Fig. 2). We used M2c for further analyses in this paper. We expect that the M2c model could serve as part of an AML patient digital twin, helping to forecast therapeutic toxicity.

Patient characteristics affect model goodness of fit

Although the M2c model shows the highest accuracy among all the models we investigated, the performance of the model varies greatly across patients (Supplementary Fig. 3). In order to better understand why certain patients had better model fit and to stratify patients who could be better represented using different models, we investigated a number of clinical factors and model assumptions, and built additional statistical models to predict ahead of time whether or not our model would be a good fit for a given patient.

One of the most important assumptions behind the ODE models for toxicity is what we call Assumption 1, which is that treatment with venetoclax and azacitidine causes neutrophil count to decrease during treatment, while neutrophil counts will recover after the end of a treatment cycle. For some of the models, another key assumption is Assumption 2, which is that leukemic blasts have an inhibitory effect on the production of neutrophils. This assumption is rooted in the fact that AML is known to cause neutropenia, with inhibition by blasts being one potential mechanism35. Since some of these assumptions are not necessarily true for all patients, we tested whether these hypotheses are true for individual patients, and compared model accuracy for groups of patients stratified by the hypotheses.

For Assumption 1, operationalizing this hypothesis on the data, we say that Assumption 1 is true for a given patient if there is a positive correlation between the time since the end of the last treatment cycle and the neutrophil count. Looking at patients with enough data for ODE modeling (71 patients), we see that 73% of the patients have a positive correlation between time-since-treatment and neutrophil count, with the average correlation coefficient being 0.19 and the median being 0.21 (Fig. 2a). Using a two-sided binomial test, this percentage of patients is significant with p < 0.01.

a Assumption 1 (A1)—this shows the correlation between time elapsed since the end of the last treatment cycle and the neutrophil counts, among the 71 patients used for modeling. b Assumption 2 (A2)—correlation between interpolated bone marrow blast percentage and neutrophil counts for the same 71 patients. c Fraction of variance unexplained for all models, separated into patients for whom A1 is true and patients for whom A1 is false. d Same as previous, but for Assumption 2. e The actual FVU vs. predicted FVU for M2c, where the predicted FVU was calculated using a LASSO linear regression model based on the clinical and genomic features upon patient intake. f The top positive and negative coefficients for the previous LASSO model. Positive coefficients indicate that a variable is predictive of a high FVU, while negative coefficients are the opposite.

For Assumption 2, we stratify patients depending on whether there is a negative correlation between the bone marrow blast percentage and the contemporaneous neutrophil count for a given patient. Where data was not available, we used PCHIP interpolation to impute blast percentages. Because of the potential noise introduced by interpolation, we also calculated this correlation solely using matched neutrophil and bone marrow blast measurements that were taken within a fixed time window of each other (2, 5, or 10 days). For the interpolated data, we see that 73% of patients have a negative correlation between bone marrow blast percentage and neutrophil count (Fig. 2b). With a two-sided binomial test, again, this percentage of patients is significant with p < 0.01. For the non-interpolated data, the number of matched measurements per patient was much smaller, impeding the ability to calculate correlations. Among the patients with more than 5 matched measurements, 67–70% of such patients (depending on matching window) have a negative correlation between bone marrow blast percentage and neutrophil count, with p < 0.05 with a two-sided binomial test. Results with different matching windows are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4.

We expected that for all models, the FVU would be lower if Assumption 1 were true, and that the FVU would be lower if Assumption 2 were true only for the models that implement a direct inhibition component. Figure 2c shows the FVU for each model grouped by whether Assumption 1 is true for each patient. This shows that the median FVU is lower when Assumption 1 is true for almost every model, with a particularly pronounced effect for M2c, the overall best-performing model. This is what we expected based on the model structure and the data. However, as Fig. 2d shows, the FVU of almost every model seems to be higher in the cases where Assumption 2 is true, including the models with a direct inhibition component (M1b-c, M2b-d). This could indicate that for these patients, the relationship between blasts and neutrophils contain sources of variation that are not adequately captured by the model structures.

Since the hypotheses are not fully adequate in predicting the goodness of model fit, we constructed a LASSO regression model for predicting ahead of time the goodness of fit with features that are available upon patient intake, such as demographics, initial blood counts, and genomic/mutation features. These results are shown in Fig. 2e, f. Our predictive model shows it is possible to predict the model fit goodness using only the genomic and clinical features (Fig. 2e). The key predictive features include the mutation status of frequently mutated genes in AML such as NRAS, DNMT3A and NF1, and chromosomal aberrations such as complex karyotype and deletion of chromosome 5q (Fig. 2f).

We also compared the model goodness of fit to various clinical features, such as progression-free and overall survival time, and survival status at the end of the trial. We found that patients with longer survival times tend to have somewhat worse model fit (Supplementary Fig. 5b, c). This suggests that in surviving patients, there are significant factors affecting neutrophil levels that are currently unmodeled.

Data from multiple cycles improve predictions of toxicity

In a clinical setting, the utility of a digital twin model is in predicting future patient trajectories with dynamic updating of model parameters. In order to test how the model would work in a digital twin setting, we fit the model on some “training” cycles and tested it on the following “test” cycles. We tested the model with between one and five training cycles, and two test cycles, with all following cycles being considered as “additional” cycles. There were a total of 33 patients who had sufficient data (7 treatment cycles) for the train-test split. The clinical characteristics for these patients are shown in Table 2. They tended to have substantially longer survival and better drug responses than the overall set of patients. Moreover, most of these patients go into a remission period and some experience relapse (Table 2).

We divided the “test” cycles into short and long-term tests. Short-term tests were defined as the next two cycles after the training cycles, while long-term tests were defined as all cycles after the two cycles immediately following the training cycles. This corresponds to a categorization of future events based on a specific time horizon (short term vs. long term).

Figure 3 shows the results of model predictions for different numbers of training/treatment cycles. These results were obtained using model M2c which generated the best fit as described in the previous sections. Figure 3a shows the RMSE between the neutrophil counts generated by model M2c and observations from patients. We observe that as the number of training cycles increases, the training error increases, while the short-term testing error significantly declines (with a Pearson correlation coefficient of −0.28 and p = 0.0021, Fig. 3b). The variance in the RMSE also declines substantially. A similar behavior is observed for long-term testing; however the RMSE and its variance are always larger than the short-term testing. Figure 3c–e illustrates the model fitting with different training treatment cycles for a particular patient. These figures illustrate that accuracy increases with additional treatment cycles used for training.

a Distribution of RMSE (33 patients) between the neutrophil counts obtained from model simulations and those observed from patient data, for different numbers of treatment cycles for training. Short-term indicates the next two cycles after the training cycles, while long-term indicates all of the cycles after the training and short-term test cycles. b Pearson Correlation between the number of cycles used for training and the RMSE for the short-term test from the neutrophil count prediction. The solid line shows the relationship between the number of treatment cycles used for training and the RMSE from the short-term test. c–e Examples of the neutrophil count predictions for a single patient with one, three, and five training cycles, respectively.

These results highlight one key characteristic of digital twin models, which is the ability to recalibrate with the addition of data points. With added data from further cycles, the digital twin models will have optimized model parameters, allowing them to make predictions more accurately.

Discussion

In a digital twin system, digital twin models are intended to faithfully mirror crucial aspects of their physical twin. Over time, as additional data is collected, the twin models are also updated and continuously compared to the state of the physical twin. In the current study, we aimed to develop digital twin component models for AML patients to reflect the toxicity effects with drug treatment. The models are tested using the VenEx clinical trial data (see “Methods”).

Overall, the best models were able to recapitulate the neutrophil counts for AML patients during the treatment of venetoclax and azacitidine relatively well, despite the data being relatively sparse. The best performing model, M2c, had a median fraction of variance unexplained of about 0.46 across all patients. We observed that the simplified models, with only a proportional description for the drug effect, performed as well or better, than the models with complex pharmacokinetics. Comparing the model performance against the model assumptions, we see that patients whose data was in accordance with Assumption 1 (venetoclax/azacitidine effect on neutropenia) have better model fit than those who do not, while patients whose data was in accordance with Assumption 2 (blast effect on neutropenia) do not have a lower model error. This seems to suggest that our models are better at capturing toxicity due to the drug effect than toxicity due to AML itself, and suggests that more exploration should be done to better understand the mechanisms by which leukemic blasts cause neutropenia.

The best-performing models showed significant variation in performance across patients, with many longer-surviving patients having worse fit (Supplementary Fig. 4). This could indicate that there are additional sources of variation in longer-surviving patients that our present models fail to capture, which would be an interesting topic for further study. Alternatively, the model could simply be overfitting in the cases where the patient has few data points. It is also possible that measurements of neutrophil counts show increasing stochasticity or noise for the longer-surviving patients.

In addition to fitting the model on patient-specific data, we were also able to test the models using an individualized train-test approach, in a manner akin to what would be seen in a clinical “digital twin” setting, where the predictions of a digital twin model should improve with newly collected patient data. We found that as more cycles were used for training, the testing error on the following cycles declined. These results suggest that observations from multiple treatment cycles of venetoclax and azacytidine are needed after diagnosis to obtain predictions of neutrophil counts with a good level of accuracy, and according to our results, 5 cycles are needed after diagnosis to obtain good accuracy.

Although the level of accuracy obtained by the best performing model is comparable to previous studies, such as Jost et al.24,25, we observed a high inter-patient error variability of the model output. One potential source of the this variability is the frequency of the longitudinal data in the VenEx trial; compared to the previously published models of Jost et al., we had substantially sparser data to train and test our models, with typically just a few neutrophil measurements per cycle. More densely sampled data, with multiple neutrophil measurements during treatment cycles, would be of great utility in further developing models for future medical digital twins.

A future goal would be to test our models on new sets of patients, including patients who were not part of this clinical trial. The model itself is generic, and can be applied to AML patients treated with venetoclax/azacitidine in different disease settings. However, the data used for our model fitting and testing is from a specific cohort, which includes patients who were either not eligible for traditional AML chemotherapy, or had recurrent/relapsed AML. This may affect the model accuracy if it is applied to another cohort where the clinical characteristics are different. Additional datasets that include time-course treatment and cell count data should be considered in the future to evaluate model generalizability.

One limitation of our model fitting process is that currently, identifying patient-specific model parameters requires some longitudinal observations for that patient; our results suggest at least data of 5 cycles are needed to predict neutropenia. Ideally, for new patients, patient-specific model parameters should be estimated using (1) patient data available at diagnosis, including genomic and clinical data and (2) model parameters and data from previously characterized patients. This would require additional patients for whom we are able to get time courses, genomic data, and clinical data.

To summarize, a key component of a digital twin system is the crosstalk between the digital twin and the physical system (i.e. the AML patient). In this work, we updated the model with additional data corresponding to a new treatment cycle and then made short- and long-term predictions of neutrophil counts and blast percentages. This exercise demonstrated that after 5 cycles, the model can be continuously updated with additional data to generate predictions with a good level of accuracy, comparable to the training errors. These predictions can be used to design new individualized treatment schedules for AML that reduce the occurrence of neutropenia while maintaining the same level of inhibition of leukemic blasts. Moreover it is possible to test different patient-specific treatment schedules and drug dosage, and select one that minimizes side effects for a particular patient. In a future medical digital twin these predictions could be used by a doctor to support informed decisions about patient treatment.

Methods

Clinical and cellular data

All data used in this study originated from the VenEx trial11. This trial includes two groups of patients: patients with de novo AML who were ineligible for standard chemotherapy, and patients with previously treated secondary AML or recurrent or relapsed AML. Clinical data was available for 92 patients treated with venetoclax/azacitidine treatment. The characteristics of these patients are shown in Table 2.

Among these patients, there were 71 patients with enough data for model fitting (as shown in Fig. 1), and 33 patients with enough data for train/test splitting across treatment cycles (as shown in Fig. 3). The characteristics of all of these subgroups of patients are described in Table 2. For the train/test patients, a much greater proportion of patients had a good response to venetoclax/azacitidine treatment, and generally had higher survival.

Implementation

The ODE models were implemented in Python using the Tellurium library36. After implementing the ODE models, we used them with the PyMC library for Bayesian parameter estimation37. We considered using both truncated Gaussian priors and uniform priors for the parameters; most of the presented results are using uniform priors, as truncated Gaussian priors resulted in worse performance in some experiments. The likelihood functions were defined as Gaussian distributions centered around the observed values for neutrophils and blasts.

Model personalization

In order to find the optimal model parameters for specific patients, we used a Bayesian approach based on finding the maximum a posteriori estimate for the parameters (the set of parameter values with the highest likelihood given the data). The find_MAP function in PyMC was used to estimate the parameters that maximize the posterior likelihood. Uniform distributions were used as priors, using the parameter ranges shown in Table S2. The find_MAP function is capable of using custom optimization functions for finding the maximum a posteriori parameters; the optimization method used here is Py-BOBYQA, used with global optimization38,39.

Parameter update

We implemented a computational model tailored to individual patient data using a multi-cycle learning approach. The ODE-based model was developed in Python (version 3.10.6), leveraging the Tellurium (version 2.2.8) and PyMC (version 5.10.3) libraries for model construction and Bayesian parameter estimation, respectively. For our analysis we focused on patients with at least six treatment cycles and at least one blast measurement within the first cycle reducing our patient pool to 33 patients.

We systematically evaluated the model’s performance by splitting patient data into training and testing sets across varying treatment cycles: starting with 1 training + 2 testing cycles, then 2 training + 2 testing cycles, and so forth, up to 5 training + 2 testing cycles. For patients with more than 7 treatment cycles or those with blast values beyond the 7th cycle, we calculated an RMSE value that evaluates the model’s predictive accuracy at these extended time points without additional training. This approach tests the model’s robustness in predicting patient outcomes beyond the initial set of treatment cycles, serving as a measure of how well the model generalizes to future, unseen data.

Statistical analysis

We conducted statistical analyses in Python, using the numpy (version 1.26.2), pandas (version 2.2.3), scipy (version 1.11.2), and statsmodels (version 0.14.0) packages. The pairwise Wilcoxon tests for the model comparisons used the scipy.stats.wilcoxon function. For the false discovery rate correction, we used the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure as implemented in scipy.stats.false_discovery_control.

For interpolating blast percentages (as with the M1b_w and M2b_w models and for testing Assumption 2 in the data), we used scipy.interpolation.PchipInterpolator. In order to assess the accuracy of the bone marrow blast interpolation, we performed a direct comparison of interpolated bone marrow blast percentages and true bone marrow blast measurements by artificially setting some bone marrow blast measurements as hidden. For every patient, we withheld one bone marrow blast measurement at a time (not including the first or last measurements) and computed a PCHIP interpolation using every remaining bone marrow blast measurement. We then compared the interpolated value to the actual value. Doing this resulted in a mean absolute error (MAE) of 5.8% between the interpolated blast measurements and actual blast measurements. This suggests that the interpolation method provides reasonable estimations of missing blast measurements.

For the FVU calculations, Pearson correlation coefficients (R) were calculated using the np.corrcoef function, while the scipy.stats.pearsonr function if a p value was calculated (as in the comparison of errors across training cycles). Regression analyses (as in predicting patient goodness of fit) were done using the OLS module from statsmodels. Multiple ways of calculating fraction of variance unexplained were explored, including mean squared error divided by the data variance as well as \(1-{R}^{2}\). Ultimately, \(1-{R}^{2}\) was used because the range would be between 0 and 1, making comparisons easier. In these calculations, we set the \({R}^{2}\) to 0 if the model-data correlation was negative. The overall ranking of methods did not change depending on how the model goodness of fit was calculated (including RMSE and the two different methods of calculating FVU). For the train-test analysis, we used RMSE instead of FVU; there were often too few test data points to calculate a meaningful variance.

Model of venetoclax and azacitidine effect

To model the effect of venetoclax and azacitidine we used two strategies. First we developed a Pharmacokinetic (PK) model for both drugs, and second we developed a simplified model that assumed a direct effect of venetoclax and azacitidine on the differentiation of neutrophils.

For the pharmacokinetic model, we used a three-compartment PK model for oral administration of venetoclax and a two-compartment PK model for subcutaneous administration of azacitidine. The PK model for venetoclax is based on the model found in Dave et al.32. The PK model for azacitidine is based on the PK parameters found in MacBeth et al.33. Equations (1)–(5) define the dynamics of venetoclax and azacitidine concentrations.

Where \({X}_{{ven},{depo}}\), \({X}_{{ven},{central}}\), and \({X}_{{ven},{peripheral}}\) represents the concentration of deposited venetoclax, the concentration of venetoclax in the central compartment (typically the location of direct drug interaction), and the concentration of venetoclax in the peripheral compartment. Similarly, \({X}_{{aza},{depo}}\) and \({X}_{{aza},{central}}\) represent the concentration of deposited azacitidine and concentration of azacitidine in the central systems. The parameter values used in these equations are specified in Supplementary Table 1.

The effect of the two drugs on neutrophils is then characterized by the following equations:

The effect of the two drugs on blast cells is characterized by:

The simplified direct drug effect model is implemented in the M2 models (M2a, M2b, M2b_w, and M2c). For the simplified model, the effect of the two drugs on neutrophils are characterized by two variables:

Where \({slop}{e}_{{ven},{wbc}}\) and \({slop}{e}_{{aza},{wbc}}\) are proportional parameters and \({I}_{{ven}}\) and \({I}_{{aza}}\) are the doses of venetoclax and azacitidine respectively, and are set to 0 during the times in which the patient is not undergoing treatment with venetoclax or azacitidine. It is worth noting that \({slop}{e}_{{ven},{wbc}}\) and \({slop}{e}_{{aza},{wbc}}\) are fitted parameters that we estimated for each patient. The effect of the two drugs on cancer cells are modeled similarly \({E}_{{ven},{blast}}:={I}_{{ven}}{slop}{e}_{{ven},{blast}}\) and \({E}_{{aza},{blast}}:={I}_{{aza}}{slop}{e}_{{aza},{blast}}.\)

We also tested a simplified model (M2d) which only includes the effect of venetoclax, and assumes that venetoclax has the same effects on blasts and healthy cells (\({E}_{{ven},{wbc}}={E}_{{ven},{blast}}\)).

Neutrophil differentiation

We implemented three models of neutrophil dynamics. The first was adapted from a model developed by Jost et al.24,25. The second model includes a carrying capacity of blast and neutrophils to model competition of space between these two cell populations, and the third model includes a direct inhibition of neutrophil production by blast cells. The following equations describe the dynamics of neutrophil differentiation that is composed of three compartments—proliferating cells in bone marrow (including stem and granulocyte-monocyte progenitor cells) (\({X}_{{pr}}\)), transition cells (\({X}_{{tr}}\)) and mature neutrophils (\({X}_{{wbc}}\)), in the blood :

Where \(F\), \(G\), and \({d}_{c}\) are functions that take specific forms for the three models. \(F\) represents the proliferation rate, \(G\) represents the differentiation rate, and \({d}_{c}\) represents the rate of cell death due to the effects of leukemic blasts. The list of parameters and their values are specified in Supplementary Table 1, while the fitted parameters are in Supplementary Table 2. The specific assumptions for \(F\), \(G\), and \({d}_{c}\) and the resulting models are as follows.

The baseline drug effect model was our first model of drug effects on neutrophils. In this model the effects of venetoclax and azacitidine on the proliferating cells are included with an overall multiplier (based on the model of Jost et al.24) that includes \({X}_{{pr}}\) and \({X}_{{wbc}}\). Here, increased levels of venetoclax and azacitidine have the effect of increasing proliferating cells’ death rates. \({(B/{X}_{{wbc}})}^{\gamma }\) represents a feedback term by which lower levels of mature neutrophils (\({X}_{{wbc}}\)) lead to higher proliferation. This is shown in Eqs. (15)–(17):

The carrying capacity model also implements a carrying capacity mechanism to model an indirect competitive interaction between cancer and healthy stem cells by adding a functional form for \({d}_{c}\), the carrying capacity, that includes dependence on \({X}_{{pr}}\) as follows:

The last function implies that \({X}_{{pr}}\) will diminish if the combination of \({X}_{{pr}}\) and \({X}_{l1}\)(bone marrow blasts, see below) exceed a threshold value (proportional to the equilibrium number of proliferating cells).

The direct inhibition model additionally includes an inhibition mechanism in which the differentiation rate is decreased by the population of observed blast cells. The main difference between this model and the baseline drug effect model is setting in the function \(G\) to be a function of observed blasts in the bone marrow \({X}_{{blast},{obs}}\). This is shown in Eqs. (21)–(23):

Blast populations

We adopt three models of cancer cells, with two compartments \({X}_{l1}\) and \({X}_{l2}\) which represent leukemic blasts in the bone marrow and blasts in the blood, respectively.

The models, described below, use a parameter klc:

that amounts to suppressive influence from neutrophils and blast24 in the blood, a signaling effect that may be conveyed by cytokines22.

The baseline model for blasts is described in Eqs. (25) and (26). This is similar to the model developed by Jost et al.25

The carrying capacity model additionally includes an indirect competitive interaction through a carrying capacity in the bone marrow. The following are the equations that describe this model.

In the logistic growth model, an extra term is added to the baseline model for leukemic cells25 to model a logistic growth kind of population dynamics for cancer cells.

Linear regression model

The linear regression model is intended to predict the neutrophil count at the next time point given the measurements at the current time point, and the treatment cycle between current and next time points. There are five independent variables: (1) current neutrophil count measurement, (2) time elapsed between the two measurements that are within venetoclax treatment, (3) time elapsed between the two measurements that are not in venetoclax treatment, (4) venetoclax dosage for the cycle between the current time point and next time point, and (5) interpolated bone marrow blast measurement at the current time point. There is also a constant term for the intercept. Results are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. As with the ODE models, the linear regression model was fitted for each patient separately, using all pairs of adjacent neutrophil measurements for the comparison in Supplementary Fig. 2a, b, and all pairs of adjacent neutrophil measurements in the first 5 cycles for the comparison in Supplementary Fig. 2c.

Data availability

The clinical trial data (clinical trial ID: NCT04267081) that support the findings of this study are available from University of Helsinki. Restrictions apply to the availability of the data, which was used under an agreement for the current study, and so is not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission. Requests should be directed to principal investigator M.K. (mika.kontro@helsinki.fi). The Github repository as shown in the “Code availability” section includes the subset of the data used in this work.

Code availability

The underlying code for this study is available in Github at https://github.com/AMLDT/Venex_Neutropenia_Models.

References

Qin, G. et al. Mutation patterns predict drug sensitivity in acute myeloid leukemia. Clin. Cancer Res. OF1–OF13 https://doi.org/10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-23-1674 (2024).

Bottomly, D. et al. Integrative analysis of drug response and clinical outcome in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell 40, 850–864.e9 (2022).

Pulte, D. et al. Survival in patients with acute myeloblastic leukemia in Germany and the United States: major differences in survival in young adults. Int. J. Cancer 139, 1289–1296 (2016).

Papaemmanuil, E. et al. Genomic classification and prognosis in acute myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 374, 2209–2221 (2016).

Peseski, A. M., McClean, M., Green, S. D., Beeler, C. & Konig, H. Management of fever and neutropenia in the adult patient with acute myeloid leukemia. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 19, 359–378 (2021).

Rout, P., Reynolds, S. B. & Zito, P. M. Neutropenia. in StatPearls (StatPearlsPublishing, Treasure Island (FL), 2025).

Jiménez-Vicente, C. et al. Clinical management of patients diagnosed with acute myeloid leukemia treated with venetoclax in combination with hypomethylating agents after achieving a response: a real-life study. Ann. Hematol. 103, 4033–4043 (2024).

Hansen, B.-A. et al. Febrile neutropenia in acute leukemia. Epidemiology, etiology, pathophysiology and treatment. Mediterr. J. Hematol. Infect. Dis. 12, e2020009 (2019).

Justiz Vaillant, A. A., Rout, P., Reynolds, S. B. & Zito, P. M. Neutropenia. In StatPearls [Internet] https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431128/ (StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024).

Kuusanmäki, H. et al. Ex vivo venetoclax sensitivity testing predicts treatment response in acute myeloid leukemia. Haematologica 108, 1768–1781 (2023).

Kytölä, S. et al. Ex vivo venetoclax sensitivity predicts clinical response in acute myeloid leukemia in the prospective VenEx trial. Blood 145, 409–421 (2025).

Committee on Foundational Research Gaps and Future Directions for Digital Twins et al. Foundational Research Gaps and Future Directions for Digital Twins 26894 (National Academies Press, 2024).

Emmert-Streib, F. & Yli-Harja, O. What is a digital twin? Experimental design for a data-centric machine learning perspective in health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 13149 (2022).

Hernandez-Boussard, T. et al. Digital twins for predictive oncology will be a paradigm shift for precision cancer care. Nat. Med. 27, 2065–2066 (2021).

Padoan, A. & Plebani, M. Dynamic mirroring: unveiling the role of digital twins, artificial intelligence and synthetic data for personalized medicine in laboratory medicine. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm-2024-0517 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. A framework towards digital twins for type 2 diabetes. Front. Digit. Health 6, 1336050 (2024).

Facchinetti, A., Sparacino, G. & Cobelli, C. Signal processing algorithms implementing the ‘smart sensor’ concept to improve continuous glucose monitoring in diabetes. J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 7, 1308–1318 (2013).

Facchinetti, A. et al. Real-time improvement of continuous glucose monitoring accuracy: the smart sensor concept. Diabetes Care 36, 793–800 (2013).

Sarp, S., Kuzlu, M., Zhao, Y. & Gueler, O. Digital twin in healthcare: a study for chronic wound management. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 27, 5634–5643 (2023).

Yang, P.-C. et al. A multiscale predictive digital twin for neurocardiac modulation. J. Physiol. 601, 3789–3812 (2023).

Sun, T., He, X. & Li, Z. Digital twin in healthcare: recent updates and challenges. Digit. Health 9, 20552076221149651 (2023).

Stiehl, T., Ho, A. D. & Marciniak-Czochra, A. Mathematical modeling of the impact of cytokine response of acute myeloid leukemia cells on patient prognosis. Sci. Rep. 8, 2809 (2018).

Stiehl, T., Wang, W., Lutz, C. & Marciniak-Czochra, A. Mathematical modeling provides evidence for niche competition in human AML and serves as a tool to improve risk stratification. Cancer Res. 80, 3983–3992 (2020).

Jost, F., Schalk, E., Rinke, K., Fischer, T. & Sager, S. Mathematical models for cytarabine-derived myelosuppression in acute myeloid leukaemia. PLoS ONE 14, e0204540 (2019).

Jost, F. et al. Model-based optimal AML consolidation treatment. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 67, 3296–3306 (2020).

Banck, J. C. & Görlich, D. In-silico comparison of two induction regimens (7 + 3 vs 7 + 3 plus additional bone marrow evaluation) in acute myeloid leukemia treatment. BMC Syst. Biol. 13, 18 (2019).

Hoffmann, H., Thiede, C., Glauche, I., Bornhaeuser, M. & Roeder, I. Differential response to cytotoxic therapy explains treatment dynamics of acute myeloid leukaemia patients: insights from a mathematical modelling approach. J. R. Soc. Interface 17, 20200091 (2020).

Chulián, S., Martínez-Rubio, Á, Rosa, M. & Pérez-García, V. M. Mathematical models of leukaemia and its treatment: a review. SeMA J. 79, 441–486 (2022).

Craig, M. Towards quantitative systems pharmacology models of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia. CPT Pharmacomet. Syst. Pharmacol. 6, 293–304 (2017).

Pujo-Menjouet, L. Blood cell dynamics: half of a century of modelling. Math. Model. Nat. Phenom. 11, 92–115 (2016).

Friberg, L. E., Henningsson, A., Maas, H., Nguyen, L. & Karlsson, M. O. Model of chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression with parameter consistency across drugs. J. Clin. Oncol. 20, 4713–4721 (2002).

Dave, N., Gopalakrishnan, S., Mensing, S. & Salem, A. H. Model-informed dosing of venetoclax in healthy subjects: an exposure-response analysis. Clin. Transl. Sci. 12, 625–632 (2019).

MacBeth, K. J. et al. A comparative pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) evaluation of azacitidine following subcutaneous (SC) and oral administration in subjects with myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) or acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), results from a phase 1 study. Blood 114, 1772 (2009).

Di Pasqua, L. G., Abdallah, M. M., Feletti, F., Vairetti, M. & Ferrigno, A. Venetoclax-related neutropenia in leukemic patients: a comprehensive review of the underlying causes, risk factors, and management. Pharmaceuticals 17, 484 (2024).

Miraki-Moud, F. et al. Acute myeloid leukemia does not deplete normal hematopoietic stem cells but induces cytopenias by impeding their differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 13576–13581 (2013).

Choi, K. et al. Tellurium: an extensible python-based modeling environment for systems and synthetic biology. Biosystems 171, 74–79 (2018).

Patil, A., Huard, D. & Fonnesbeck, C. J. PyMC: Bayesian stochastic modelling in Python. J. Stat. Softw. 35, 1–81 (2010).

Cartis, C., Fiala, J., Marteau, B. & Roberts, L. Improving the flexibility and robustness of model-based derivative-free optimization solvers. ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 45, 32:1–32:41 (2019).

Cartis, C., Roberts, L. & Sheridan-Methven, O. Escaping local minima with local derivative-free methods: a numerical investigation. Optimization 71, 2343–2373 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Dr. Ilya Shmulevich, a pioneering figure in the advancement of cancer digital twin technology. Dr. Shmulevich, a professor at the Institute of Systems Biology, was renowned for his groundbreaking work with Probabilistic Boolean networks in the early 2000s. He played a key role in leading the Cancer Genome Atlas Program (TCGA) project from 2005 to 2018. In 2019, Dr. Shmulevich was diagnosed with Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML), a diagnosis that led him to explore AML from both a scientific and personal perspective. He spearheaded the development of a prototype digital twin system for AML, showcasing his commitment to advancing medical research and patient care. Dr. Shmulevich's legacy extends beyond his scientific achievements; he also exemplified a positive outlook on life that touched many. We would like to thank Dr. Elizabeth Krakow for her guidance and discussion on the treatment of patients diagnosed with AML. We thank all the patients, their families, and physicians for their participation in the clinical trial. This work is funded by the NCI grant R01CA270210 and a grant from the Research Council of Finland (352265). The VenEx trial received funding from Finnish Medical Foundation, Cancer Foundation Finland, Helsinki University Hospital Comprehensive Cancer Center, Helsinki University, iCAN—Digital Precision Medicine and FiCAN South. H.K. and M.K. are supported by the Foundation for the Finnish Cancer Institute. F.E.S. and A.F. are supported by grant 352266 from the Research Council of Finland. O.Y.H. and J.C. are supported by grant 352263 from the Research Council of Finland. C.H. is supported by grants 334781, 357686, and 320185 from the Research Council of Finland as well as the Sigrid Juselius Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Z.: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing; J.M.: formal analysis, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing; B.T.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, validation, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing; H.K.: data curation, investigation, resources, writing—review & editing; F.E.S.: funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, writing—review & editing; J.C.: software, writing—review & editing; A.F.: writing—review & editing; O.Y.H.: funding acquisition, methodology, writing—review & editing; C.H.: funding acquisition, resources, writing—review & editing; D.G.: funding acquisition, writing—review & editing; V.T.: funding acquisition, writing—review & editing; I.S.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, resources; M.K.: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, investigation, resources, writing—review & editing; G.Q.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, supervision, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing; B.A.: conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, investigation, supervision, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.K. reports personal fees (Astellas Pharma, AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Faron Pharmaceuticals, Novartis and Pfizer) and research funding (AbbVie, outside the submitted work). C.A.H. has received personal fees from Amgen and research funding from Kronos Bio, Novartis, Oncopeptides, WNTResearch, and Zentalis Pharmaceuticals for work outside of the submitted work. Y.Z., J.M., B.T., H.K., F.E.S., J.C., A.F., O.Y.H., D.G., V.T., I.S., G.Q., B.A. report no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Martinez, J., Tercan, B. et al. Digital twin models for predicting venetoclax and azacitidine-induced neutropenia in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. npj Digit. Med. 8, 596 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01978-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01978-4