Abstract

Reading and summarizing insights from Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) images is a routine yet time-consuming task that requires expensive time from experienced ophthalmologists. This paper introduces the Multi-label OCT Report Generation (MORG) model, a deep learning approach to assist in the interpretation of OCT images. MORG employs dual image encoders to extract features from OCT image pairs, fusing them through a multi-scale module with an attention mechanism, followed by a sentence decoder to produce reports. Trained and tested on 57,308 retinal OCT image pairs, MORG achieved high classification accuracy for 16 pathologies with 37 descriptive types. It also excelled in a blind grading test against general large language models and other state-of-the-art image captioning models, scoring 4.55 compared to ophthalmologists’ 4.63 out of a maximum of 5. Furthermore, MORG has the potential to reduce the report drafting time for ophthalmologists by 58.9%, significantly alleviating their workload.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, millions of people are suffering from various retinal diseases, including age-related macular degeneration1 and diabetic retinopathy2, which lead to significant visual impairment. The large number of patients affected by these retinal conditions places a substantial strain on healthcare systems and economies. Retinal optical coherence tomography (OCT)3, a non-invasive imaging modality, offers detailed cross-sectional views of the retina in vivo, becoming an indispensable tool in ophthalmology4. However, the precise analysis of OCT images necessitates the specialized knowledge and skill of seasoned ophthalmologists. Furthermore, ophthalmologists are confronted with the challenge of managing an escalating patient load and handling substantial volumes of data. The task of interpreting a large number of OCT images is particularly laborious and time-intensive, with the potential for subjective bias. The surge in patients with retinal diseases has led to a heavy workload for ophthalmologists, which may adversely affect the quality of health care. Additionally, the scarcity of experienced ophthalmologists in numerous primary hospitals and medical facilities exacerbates these challenges.

The rapid and successful evolution of deep learning within the realm of computer vision5 has led to important advancements in ophthalmic automated diagnosis and analysis. Numerous studies have illustrated that deep convolutional neural networks effectively extract intermediate and advanced features from retinal OCT images6, achieving remarkable success in disease classification7, image segmentation8, and lesion identification9. However, given the complexity of OCT imaging—where a single image may exhibit multiple types of lesions with varying degrees of severity and sizes—mere classification or lesion detection is insufficient to fully describe the detailed information of the OCT images. To furnish a more comprehensive understanding of the retinal diseases, a detailed description of these distinct features is necessary.

Image captioning is a comprehensive task that involves image recognition and comprehension, as well as the articulation of their content in human language. It combines computer vision and natural language processing techniques to understand images, that is much more challenging than image classification and segmentation technically. Image captioning requires not only objects recognition but also the capability to grasp the associations, properties, and activities. Conventionally, language processing models are employed to convert the captured semantic information into intelligible sentences. Applications of image captioning algorithms based on deep learning are currently on the rise, and many high-performing models have been described by illustrious research institutions such as Microsoft and Google10. For medical image analysis, image captioning is widely used for automatic report generation (ARG)11,12,13,14. An end-to-end semi-supervised multimodal data and knowledge linking framework between CT volumes and textual reports with attention mechanism was reported12. Generation of unified reports of lumbar spinal MRIs in the field of radiology by a weakly supervised framework can be automated that combines deep learning and symbolic program synthesis theory13. A domain-aware automatic chest X-ray radiology report generation system conditionally generated sentences corresponding to the predicted topics, and then could be fine-tuned using reinforcement learning to improve readability and clinical accuracy14. In ophthalmology, a program consisting of retinal disease identifier, clinical description generator, and visual explanation module for fundus images, improved conventional retinal disease treatment15. Medical reports could be generated through non-local attention-based multi-modal feature fusion approach by introducing expert-defined unordered keywords16. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no existing system that can automatically generate reports for retinal Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) images currently.

This study is the first attempt to address this gap, leveraging a large-scale dataset encompassing 57,308 OCT images paired with reports authored by ophthalmologists. We develop an efficient deep learning model named Multi-label OCT Report Generation (MORG), which integrates a multi-scale feature fusion network (MSFF) for encoding and a long short-term memory (LSTM) unit for decoding. This architecture fuses information from two representative OCT images per scan to generate timely and precise reports. Extensive experimentation has demonstrated that MORG surpasses other image captioning algorithms and large language models, achieving comparable results with those clinical reports authored by ophthalmologists, and significantly reducing the time required for drafting reports.

Results

Similarity metrics

We compared our method, MORG, with several state-of-the-art (SOTA) image captioning models, including NIC17, Progressive Transformer model18, SCA-CNN19, and Bottom-up-to-down20 in terms of the text-quality metrics focused on measuring the similarity between the generated report and those authored by ophthalmologists (see Table 1). Our proposed method outperformed the others, achieving scores of 0.6099 for BLEU-1, 0.5409 for BLEU-2, 0.4871 for BLEU-3, 0.4406 for BLEU-4, 0.6310 for ROUGE, and 3.4109 for CIDEr.

We conducted additional experiments to evaluate the performance of our proposed method by replacing the MSFF encoder with other popular backbones, including RETFound21, ResNet5022, VGG1923, Res2Net24, SeResNet25, and DenseNet26. The experimental results are presented in Table 2. It was found that our proposed MSFF encoder achieved the best performances in all the experiments, based on the evaluation metrics used in this study except BLEU-1 and BLEU-2.Footnote 1

Note that Transformer-based architectures (Progressive and RETFound) have not outperformed our approach. First, Transformers exhibit weaker inductive bias compared to CNNs and require extremely large datasets27 for training such as ImageNet with over 10 million images. Therefore, on 57,308 OCT images—the largest OCT dataset currently available for report generation—our CNN-LSTM-based method provides a distinct advantage. Second, although RETFound has been pretrained on over one million OCT images, demonstrating strong inductive bias capabilities, significant challenges remain in optimizing its integration with language decoders. Techniques such as feature fusion28 and knowledge distillation29 require further exploration, as direct embedding and fine-tuning of the encoder and decoder fail to produce satisfactory diagnostic reports.Footnote 2

Blind grading test by retinal subspecialists

We invited two retinal subspecialists to perform a blind grading test with a 5-point scale on reports written by ophthalmologists and different models on an independent set of 100 OCT cases, as shown in Fig. 1. The two-sided Friedman M test indicated that there is no significant difference between the reports by MORG and these written by ophthalmologists (4.55 ± 0.46 vs. 4.63 ± 0.41, adjusted p = 1.000), and both are significantly better than the reports generated by large language models (LLM) and other SOTA image captioning models (all adjusted p-values are <0.001). GPT-4 with instructions received a score of 2.95 ± 0.92, which is mildly better than GPT-4 without instructions (2.52 ± 0.67) while MiniGPT-4 received the lowest score of (1.12 ± 0.34). Other SOTA models scored only between (2.24 ± 0.11) and (3.11 ± 0.11). There is moderate agreement between the scores of these two retinal subspecialists (Linear weighted Kappa coefficient is 0.556 ± 0.018 as shown in Supplementary Table 1. In addition, no difference was found in the manual scores between the two OCT devices (two-sided Mann-Whitney U test, Z = -1.047, p = 0.295). Compared with 3D OCT-2000, Triton had overall clearer imaging with a higher average image quality score (median 50.5 vs 36.0), benefiting from its swept source advantage. However, no correlation was found between manual scores and image quality (Spearman Rank correlation, r = 0.184 in 3D OCT-2000 and 0.096 in Triton, p = 0.175 and 0.537, respectively). These results suggest that the device and image quality did not affect our model’s performance. Quantitative measures such as localization accuracy and semantic overlap were shown in Supplementary Table 2.

Classification metrics

We assessed the algorithm’s performance in classifying 16 unique pathological types, with the potential for further differentiation into 37 distinct descriptive categories. This evaluation was conducted using metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and the F1-score, with the outcomes presented in Table 3. The “external limiting membrane” was excluded from the analysis due to its inexistence in the testing set. The proposed method exhibits a detection F1-score exceeding 0.8 for 2 types of descriptions and surpasses 0.7 for eight types. Following an exhaustive analysis of disease characteristics, MORG more effectively identifies lesion categories with pronounced features or ample training samples, such as “Retinal edema and thickening” and “Neurosensory retinal detachment”, with all metrics consistently exceeding 0.8. However, in 4 categories with a limited number of cases or vague lesions, including “Vitreous opacification”, “IS/OS layer atrophy and thinning”, “Indistinct boundaries between neural epithelial layers”, and “Local absence of outer layer tissue”, the method demonstrates notable errors – a common challenge for big data-driven deep learning algorithms.

Time-Efficiency assessment and Human-AI comparison

The time for human expert to read the volumetric scans and select the appropriate horizontal and vertical meridian images to fed into MORG is 5.71 s on average. The two ophthalmologists spent an average of 38.36 and 51.21 s, respectively, writing a report manually. In contrast, when refining reports autogenerated by MORG, the average time spent are 13.47 and 24.08 s, respectively. These results demonstrate that MORG has the potential to reduce the report drafting time for ophthalmologists by an average of 58.9%, significantly alleviating their workload.

In Human-AI comparison, a total of 217 cases were analyzed, with detailed results presented in Supplementary Table 3. The ophthalmologist and MORG achieved overall accuracies of 0.86 and 0.75, respectively, with sensitivities of 0.72 and 0.59, and specificities of 0.77 and 0.72, respectively.

Qualitative analysis

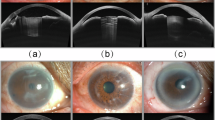

Figure 2 illustrates three examples of descriptive reports produced by various models as well as by ophthalmologists. Please note that the original reports, depicted in Supplementary Fig. 1, are in Chinese and have been translated into English. Both the ophthalmologists’ reports and those generated by MORG provide precise descriptions of the OCT image characteristics.

Manual scores by two retinal subspecialists are provided for clarity. “w/ ins. “ refers to “with instructions”, while “w/o ins. “ refers to “without instructions”. The reports were graded with a 5−point scale: 1: Very poor/unacceptable error. 2: Poor/minor potentially harmful error. 3: Medium/misinterpreted error. 4: Good/only minor harmless error. 5: Very good/no mistakes.

MiniGPT-4 primarily focuses on color and the overall shape of bands, failing to recognize detailed anatomical structures. It often generates content unrelated to retinal OCT imaging, such as cellular components and body tissues from other areas of the body. Furthermore, it frequently misses identifying abnormalities or lesions in OCT scans and instead uses unrelated terms like “rabbit”, “pus basin”, “radial light muscle”, and “black film”. MiniGPT-4 also erroneously diagnoses eye diseases such as “corneal cancer”, “dry eye”, and “conjunctival calculus”, conditions that cannot be detected through OCT images alone. Moreover, it mistakenly reports non-ophthalmic conditions like “cerebral hemorrhage” and “lymphadenopathy”. Additionally, MiniGPT-4 often produces fictitious disease names or phrases such as “anterior anxiety”, “wet eye”, and “age-related lumbar cerebrovascular disease”. Consequently, its reports are useless in practice, resulting in low scores in the blind grading test.

Without specific instructions, GPT-4 tends to describe anatomical structures vaguely, lacking specific information about important tissues and retinal layers. It frequently provides correct but trivial information, such as “the color is mainly blue and green, showing clear details” or “watch for disease progression or changes” resulting in clinically correct but ultimately useless reports. When provided with instructions and example reports written by ophthalmologists, GPT-4 can generate reports with accurate and informative descriptions of anatomical layers and pathological lesions in OCT images. However, there are still numerous inaccuracies, and it often misidentifies pathological conditions as normal, suggesting that GPT-4 does not truly interpret the images but instead generates illusions.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on effective and reliable automatic generation of descriptive reports using image captioning methods for retinal OCT images. Our MORG model outperformed state-of-the-art algorithms in similarity with the ground truths. It also achieved high classification accuracy for 16 pathologies and 37 types of descriptions. In the blind grading test of medical correctness conducted by two retinal subspecialists, MORG is comparable with the report written by ophthalmologists and superior to generalized LLMs and other SOTA image captioning models. In Time-Efficiency assessment, MORG has the potential to reduce the report writing time for ophthalmologists by 58.9%, significantly alleviating their workload.

Generation of automatic report typically relies on natural image captioning technologies. However, in contrast to generic image captioning, medical image captioning emphasizes the relationships between image objects and clinical findings, rendering it a particularly challenging task11. With the advancement of deep learning and graphic processing unit (GPU) computing, recent research in image captioning has significantly benefited from deep neural networks, especially the encoder-decoder model. This model usually combines convolutional neural network (CNN) with recurrent neural network (RNN) or LSTM model to extract image features using the CNN structure in the encoder and generate a description for the image using an RNN/LSTM network in the decoder. However, the original encoder-decoder model17 has a limitation that the semantic encoding vector for each decoding step was the same, while each word should depend on different image regions. To address this limitation, attention mechanisms were introduced into the encoder-decoder structure, as shown in Xu et al.‘s work30, where image features were weighted to align the semantic information with image features. In our MORG model, we proposed an innovative multi-scale module with an attention mechanism to effectively fuse features from different levels in the image encoders. We extracted features from two retinal OCT images taken with different perspectives and fused them at different stages of the network. Based on the multi-scale feature fusion method, we processed the fused features to form a feature weight map that guided the shallow network to focus on regions of interest in the images. This may explain why our method outperforms SOTA approaches on OCT images.

Recently, large language models (LLMs) such as ChatGPT have attracted considerable attention and gained global popularity due to their high capability and easy accessibility through a chatbot interface31. Wang et al.32 proposed an interactive Computer-Aided Diagnosis system based on ChatGPT (ChatCAD) for medical image applications. However, the system only performs statistical analysis on classification or segmentation results obtained from deep learning models, rather than conducting image analysis or disease diagnosis. Antaki et al.33 demonstrated that Gemini Pro, a general vision-language model, can only achieve a 10.7% F1-score on 50 OCT scans in identifying macular diseases. GPT-431 and MiniGPT-434 are not open-source and cannot be fine-tuned directly. Although we provided instructions and sample reports written by ophthalmologists to enhance their performances, creating the instruction set is time-consuming, and the performances of the enhanced models remain limited. For example, reports generated by MiniGPT-4 and GPT-4 could have serious issues, like confusing normal conditions with pathological ones. If employed clinically, these models could pose significant risks.

Besides, fine-tuning LLMs for specific tasks remains a complex and systemic engineering challenge, particularly for vision large language models, where the process is significantly more intricate than that of standalone language models35. From fine-tuning to clinical deployment, LLMs encounter the following challenges: (1) Dataset Creation: Constructing medical image-dialog datasets is highly challenging. Moreover, due to the immense number of parameters in LLMs, fine-tuning them still demands an ample volume of high-quality data. (2)Trade-offs in Fine-Tuning: Existing fine-tuning techniques often introduce inference latency36,37 by extending model depth or reduce the model’s usable sequence length38,39,40,41, posing challenges in balancing efficiency and model quality. (3) Resource Constraints: The fine-tuning and inference of LLMs require substantial computational resources, hindering offline clinical deployment. Moreover, the slow inference speed of vision large language models further limits their clinical applicability. In contrast, our proposed MORG framework offers advantages in efficient dataset creation, end-to-end training, and a compact, practical design.

The clinical significance of this study lies in its ability to address challenges faced by ophthalmologists in managing an escalating patient load and the vast data associated with retinal imaging, potentially revolutionizing eye care. The introduction of our MORG, a deep learning-based approach, offers a transformative solution for generating reports directly from retinal OCT images. Traditional automated diagnosis methods of retinal diseases are mostly just a simple classification for OCT images. In contrast, our MORG model stands out by automatically generating diagnostic reports for OCT images with the same level of quality as those written by professional ophthalmologists. By delivering standardized and referable diagnostic reports, our MORG model significantly expedites diagnostic procedures for ophthalmologists, enhancing accuracy particularly in time-sensitive situations. Moreover, the application of our approach could play a pivotal role in narrowing the gap in medical services in remote areas with limited access to ophthalmic resources, thereby promoting equitable distribution of medical expertise and resources to improve healthcare outcomes. Our method can assist ophthalmologists in diagnosis and further improve medical services, especially in remote areas with limited ophthalmic medical resources. Our model can be easily extended to other languages by either translating the generated reports to the language or by translating our ground truth training dataset and retraining our model. This is one of our planned future tasks.

We acknowledge some limitations in the current study. First, our proposed approach used two cross-sectional images which is a common protocol in OCT, but not other medical image modalities. Therefore, our method is applicable to OCT only, and cannot be generalized to other medical imaging modalities at this stage. Second, objectively evaluating image captioning systems presents a challenge. We employed text-quality metrics such as BLEU, ROUGE, and CIDEr to evaluate our model’s performance. However, our comparative analysis of human experts and MORG on a random sample of cases revealed significant potential for enhancing sensitivity and specificity when clinical reports serve as the benchmark, as detailed in Supplementary Table 3. This shortfall could stem from three primary factors: (1) Clinical reports may include details that extend beyond the two selected slices, and secondly. (2) Minor difference and subtle lesions are not clinically significant (Supplementary Fig. 2). (3) Our method is designed to generate diagnostic reports from OCT images, with the output consisting of descriptive text rather than mere classification outcomes. As previous research has indicated, commonly used classification metrics like precision and recall may not be the best indicators of a system’s performance in the context of image captioning and report generation42. The complexity of medical reports goes beyond simple classification; it entails grasping context, severity, and a spectrum of conditions, aspects that traditional metrics like precision and recall may not fully encapsulate. Therefore, it necessitates a medical expert assessment, like the blinding grading by human experts using the Likert Scale. This qualitative analysis provides a more comprehensive understanding of how our system’s output aligns with clinical standards and expectations. Third, there may be some subjective bias. Ophthalmologists refine their diagnostic acumen over time, potentially leading to variations in their reporting styles, and there can be inconsistencies across reports from different practitioners due to subjective factors or linguistic norms. Selection of two cross-sectional images from 3D scan is based on the selection of the clinicians. Usually, the horizontal and vertical meridian images are automatically selected by the OCT inbuilt algorithm, unless the ophthalmologists found there is an anomaly elsewhere that requires documentation. This standardized approach minimizes the need for subjective selection. Fourth, our model, which is end-to-end trained, currently lacks interpretive capabilities. Specifically, while the diversity of anatomical features and descriptive elements in our outputs introduces a level of complexity that heatmaps struggle to capture in a clear and effective manner, some key words—such as “macular” in Supplementary Fig. 3 (a), “serous” in (b), and “edema” and “cystic cavities” in (c) —still correspond to specific image regions to a certain extent. However, given intricate relationships between OCT images and diagnostic content, further research is still required to develop more effective interpretability methods. However, the limitations of heatmaps in conveying the nuanced interpretability of our model within the unique context of our study highlight the need for improvement. Therefore, seeking alternative methods to enhance our model’s interpretive capability is a priority for future research. Fifth, the performance of our methods may deteriorate when applied to different OCT models due to domain shift. In the next step, we will expand our training dataset to include data from various imaging devices and centers, which will help the model generalize better across different domains. Sixth, our method cannot recognize the anomalies or pathologies that were not adequately covered in the training data. We have included 57,308 retinal OCT image pairs in the current study, but there may still some rare anomalies not included. In our previous study, we developed the UIOS model for uncertainty estimation in the classification of fundus photography, which has provided us with valuable experience in this area43. We will enhance the MORG model with robust uncertainty estimation capabilities in further study. Seventh, although our model has demonstrated promising performance on the current dataset, it is important to acknowledge that the evaluation has primarily relied on images with predefined benchmarks. This approach, while valuable for initial validation, may not fully capture the model’s robustness and clinical applicability in real-world scenarios, where benchmarks are often not available. Future work will focus on testing the model on images without predefined benchmarks to better understand its performance in more diverse and uncontrolled settings. This will provide a more comprehensive assessment of the model’s ability to generalize and adapt to new, unseen data, thereby enhancing its clinical relevance and practical utility. Eighth, we excluded images with extremely low quality due to severe media opacity, as even experienced doctors struggle to extract useful information from such images. Therefore, the current version of MORG cannot be applied to these images. This limitation applies not only to our model but is also a common challenge in OCT-based diagnostics. Future work will explore methods to enhance the model’s robustness against such artifacts. This may include the development of advanced preprocessing techniques to mitigate the effects of artifacts or the incorporation of artifact-affected images into the training process with appropriate annotations.

In summary, we propose a novel report generation model for retinal OCT images based on large scale data. Our model could effectively generate interpretative reports with a level of quality equivalent to those written by professional ophthalmologists and superior to other imaging caption models and large language models. Our method is poised to enhance the diagnosis level of retinal diseases, alleviate the workload of ophthalmologists, and overcome the challenge of limited medical resources in remote areas.

Methods

Overview of flowchart

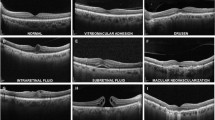

Image captioning models typically followed the encoder-decoder framework, which was first proposed by Vinyals et al.17. Figure 3 shows the diagram of the proposed model in this study. The encoder module extracted semantic features in OCT images, while the decoder module translated these features into corresponding descriptions. To tackle the situation where multiple lesions scattered in various slices in an OCT volume, two representative images \({X}_{v1}\) and \({X}_{v2}\) from different angles in each case were selected by trained ophthalmologists, which have included most of abnormalities. These two images in pair then go through feature extraction and multi-scale feature fusion with attention to form effective semantic features for report generation as described below.

Encoder

We utilized the Densenet121 architecture26 without the fully connected layers as the backbone for the encoder as shown in Fig. 4. Densenet121 is a deep convolutional neural network with four dense convolution blocks to alleviate the gradient vanishing problem while make full use of shallow features. However, it was still challenging to efficiently integrate features from images with different views in our experiment. To tackle this obstacle, we proposed a novel multi-view feature learning strategy based on weight sharing backbone network, MSFF, to fuse semantic features. Weights were shared by the two encoders for feature extraction, ensuring effective feature fusion and avoiding over-fitting.

Feature extraction

Recent studies indicate that integration of features from different levels in deep models can significantly improve model performances44,45,46, where features extracted at different layers correspond to different levels of abstraction for the input image47. For instance, shallow features contain rich local spatial information but lack global context awareness, while high-level features have rich global semantic information but lack local spatial details. By integrating these features from different levels, we can effectively locate local salient features, infer global relationships among objects, highlight target regions and dilute out background. Therefore, we applied an innovative feature fusion strategy in this study to improve our method.

We first performed element-wise addition of the features extracted from images \({X}_{v1}\) and \({X}_{v2}\) in each of the four “Dense Blocks” as shown in Fig. 4. We then utilized a convolutional layer with a kernel size of 3 × 3 followed by a batch normalization (BN) layer and a ReLU layer to enlarge the receptive field and enhance global information of the features as,

where \({X}_{v1}^{{Di}}\) and \({X}_{v2}^{{Di}}\) (i = 1, 2, 3, 4) represent features extracted by the i th “Dense Block” from the image \({X}_{v1}\) and \({X}_{v2}\), respectively, and \({F}_{{ff}}^{i}\) (i = 1, 2, 3, 4) denote the fused features in the i th dense block that were subsequently processed by the multi-scale feature fusion module. B, C, H and W denote the batch size, number of channels, height and width of the feature map, respectively.

Multi-scale feature fusion

Addition and concatenation are the most common methods for feature fusion. However, as the features extracted by the four dense blocks had different scales and resolutions, we proposed an attention-based multi-scale feature fusion module to effectively integrate these features for report generation.

As shown in Fig. 5, we applied pooling with different sub-sampling rates and convolution operation with a kernel of 3×3 to \({F}_{{ff}}^{1},\,{F}_{{ff}}^{2}\) and \({F}_{{ff}}^{3}\), respectively, so that their sizes were the same of \({F}_{{ff}}^{4}\). We then fused all the four feature maps by element-wise concatenation to obtain global semantic information as,

Based on the feature fusion methods in ref. 40, we proposed an attention module to fuse these high- and low-level features to help the model focus on relevant contexts in the input images for report generation. First, we fed the fused feature map \({F}_{c{onc}}\) three convolutional kernels of size 1×1 followed by a Sigmoid layer to generate three attention maps \({F}_{w}(i)\), i = 1, 2, 3, as shown in Fig. 5 and Eq. 3. With the semantic information in the high-level features, these attention maps can help guide the low-level features to focus on relevant areas in the images. We then applied element-wise multiplication to the three attention maps with the corresponding low level features, as shown in Eq. 4. Finally, we concatenated the weighted feature maps \({F}_{w1},\,{F}_{w2}\) and \({F}_{w3}\) and \({F}_{{ff}}^{4}\) element-wise followed by a convolution kernel of size 1×1 to reduce number of channels, as shown in Eq. 5.

Decoder

The decoder module is responsible for generating a report based on the image features extracted by the encoder. We used the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network as the backbone for the decoder. Inspired by the visual attention mechanism described in ref. 30, the output of the LSTM at the current time step enhanced the weights of the image features, allowing the network to focus on different regions in the images at different moments. Figure 6 shows the architecture of the decoder. We fused the enhanced feature weights \({z}_{t}\) with the word embedding vector \({e}_{t}\) to form the next input to the LSTM model. The output \({h}_{t}\) of the LSTM at time step \(t\) was then mapped to the word vector space and normalized to obtain the probability map \({y}_{t}\) for each word in the vocabulary, as shown in Eq. 6. Finally, we selected the word with the highest probability as the predicted word at the current time step. As demonstrated in Fig. 6, the red box in OCT images highlights the area of “Local Cystoid Edema”. Utilizing fused features and the “macular” output from the previous LSTM sequence, the decoder predicts the term “Cystoid Edema” at the subsequent step as,

A report in Chinese was automatically generated by the decoder based on the image features extracted by the encoder. The red box in OCT images highlights the area of “Local Cystoid Edema”. LSTM fused features from the image with the feature from the previous LSTM sequence of “macular”, the decoder then predicted the term “Cystoid Edema” at the subsequent step.

Dataset

In this study, we collected retinal OCT image pairs at the Joint Shantou International Eye Center between 2016 and 2020. Data were excluded according to the following criteria: scans not centered in the macular region, scan modes other than macular cube or radial scan, use of OCT angiography, and image quality scores below 30/100. After applying these criteria, we established a dataset of 57,308 image pairs from 57,308 OCT volumes, derived from 34,100 patients and 50,436 eyes (disease distribution is listed in Supplementary Table 4). The distributions of pathologies and descriptions are listed in Table 3 as well as in Supplementary Fig. 4, comprising pseudo-color OCT images in pair. The OCT images were captured using either 3D-OCT 2000 or DRI OCT Triton (Topcon, Japan). Two common scanning protocols were used to obtain OCT images: the 3D macular cube and the radial scan. And the OCT reports include two selected 2D images for each exam. In the 3D macular cube protocol, one is a horizontal B-scan, and the other is a reconstructed vertical section. The 3D OCT-2000 device captures images with 512 A-scans per slice and a total of 128 slices, covering an area of 6*6 mm2. In contrast, the DRI OCT Triton captures images with 512 A-scans per slice and a total of 256 slices, covering a slightly larger area of 7*7 mm2. There is no averaging in the 3D macular cube protocol. In the radial scan protocol, 12 radial slices with varying scanning angles are obtained, each consisting of 1024 A-scans and covering a circular area with a diameter of 12 mm in both devices. The number of B scans averaged is 4 scans in 3D-OCT 2000 and 16 in DRI OCT Triton. The horizontal and vertical meridian images are usually automatically selected by the OCT inbuilt algorithm (Supplementary Fig. 5), unless the ophthalmologists found there is an anomaly elsewhere that requires documentation. The images were in pseudocolor as it is the default format and is automatically processed by the built-in algorithms in Topcon OCT-2000 and Triton (Supplementary Fig. 6). These paired images were used to develop our MORG model. On the same day as the patient’s visit, each received a descriptive report in Chinese, written by the same ophthalmologists who performed the examination (A.Z. and S.C.). These reports served as the ground truth for training and evaluating the proposed method. Examples of the reports can be found in Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Joint Shantou International Eye Center (JSIEC) and adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Additionally, the requirement for informed consent was waived by the Institutional Review Board at JSIEC, and the approval number for this waiver is EC 20190911(4)-16. This decision due to the retrospective nature of this study, which involved the analysis of de-identified retinal OCT images and corresponding reports that were collected as part of routine clinical care. The waiver was granted because there was no interaction or intervention with the patients, and the data used in our study were desensitized and could not be linked back to any individual patient, ensuring their anonymity and privacy.

We had reviewed the ophthalmologist-authored descriptive reports from our patients and eliminated certain redundant statements not derivable from the OCT images, such as remarks on patient cooperation during the examination. Subsequently, we distilled and categorized the retinal characteristics documented in the reports into 16 broad categories, including conditions like macular hole, retinoschisis, macular structure, epiretinal membrane, vitreous body, internal limiting membrane, external limiting membrane, photoreceptor layer, inner segment/outer segment (IS/OS), neurosensory retina (NSR) detachment, NSR reflectivity, NSR structure, retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) detachment, RPE reflectivity, RPE structure, and choroid, as outlined in Table 3. Building upon this foundation, these 16 categories can be further detailed into 37 specific descriptions. For example, within the NSR reflectivity category, our reports encompass descriptions of the varied locations of abnormal reflective signals. Similarly, the NSR structure category includes information about the absence of certain tissue layers and their morphological attributes. Specifically, regarding the description of “Disruption of the continuity of the IS/OS layer”, the Chinese reports offer a spectrum of qualitative descriptions, such as discontinuity, interrupted continuity, local absence, and large area absence. Although these descriptions are qualitative and difficult to quantify, they are semantically analogous, and thus, they have been collectively classified under the “Disruption of the continuity of the IS/OS layer” category. Finally, the Jieba word segmentation tool (https://github.com/fxsjy/jieba) was used to segment each descriptive report into its corresponding category. As a result, a total of 323 Chinese phrases were added into our vocabulary which can be further translated into labels in respective categories.

Implementation details

The final dataset consisted of 57,308 sets of OCT scans with corresponding descriptive reports. Each patient was assigned a unique identifier, and the dataset was divided into training, validation, and test sets based on these patient identifiers, with a ratio of 0.6 for the training set, 0.2 for the validation set, and 0.2 for the test set. Therefore, the scans of the same eye are not used for both training and testing. The OCT scans were resized to (448,448) before being inputted to the encoder. We set the number of units in the hidden layers of LSTM to 512, the dimension of the word embedding vector to 512, and the final number of feature channels generated by the encoder to 1024. The “early stop” mechanism was used during training, which stopped the training when the BLEU metric did not improve after 20 epochs. The proposed model was implemented on the Pytorch platform and was trained with an NVIDIA 2080Ti graphics card with 12 G memory. We used the Adam optimizer with an initial learning rate of 0.0001 and set the batch size to 8.

Similarity metrics

We adopted the widely used Bilingual Evaluation Understudy (BLEU)48, Recall-Oriented Understudy for Gisting Evaluation (ROUGE)49, and Consensus-based Image Description Evaluation (CIDEr)50 to evaluate the performance of our developed model.

The BLEU metric was originally proposed for machine translation evaluation, measuring the accuracy of the prediction of N-grams in sentences. It has the advantages of long-distance matching and efficient computation. Let \({c}_{i}\) denote the sentence generated by the model and \({S}_{i}\) represent the target sentence, which consists of N tuples such that \({S}_{i}=\{{s}_{i1},{s}_{i2},\ldots ,{s}_{{im}}\}\). The BLEU metric can be expressed as follows,

where \({P}_{n}\) is the modified precision for N-gram, \({h}_{k}({c}_{i})\) and \({h}_{k}({s}_{{ij}})\) indicate the number of times the \({i}^{{th}}\) N-gram appears in the generated sentence and the target sentence, respectively. \({l}_{s}\) and \({l}_{p}\) indicate the length of the predicted texts and the effective reference corpus length, and θ denotes brevity penalty. BLEU has some drawbacks, including its inability to consider the position of N-grams in the predicted texts, its disregard for grammatical accuracy, and its inability to accurately judge the importance of words.

ROUGE is a metric designed to evaluate the quality of a summary or an abstract. The basic concept is to use the longest common subsequence between the predicted text and the target text as a baseline for calculating the similarity between the two by F1-score. The formula for calculating ROUGE can be written as,

where \({c}_{i}\) denotes the sentence generated by the model, \({S}_{i}\) represents the target sentence, \({LCS}({c}_{i},{S}_{i})\) denotes the longest common subsequence between the \({c}_{i}\) and \({S}_{i}\), f denotes the length of the target sentence and g the length of the predicted sentence, β is generally set to a very big number, such as 8, in the Document Understanding Conference (DUC)51.

CIDEr was designed to evaluate the performances of image captioning systems, measuring the Cosine Angle of the term frequency–inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) vectors of a predicted sentence and the target sentence. IDF was used to reduce N-grams that occur frequently in all sentences, while TF is proportional to the frequency of N-grams occurring in the target sentence. The CIDEr metric is calculated as,

where \({g}^{n}({c}_{i})\) is a vector that corresponds to all N-grams of length n, and ‖\({g}^{n}({c}_{i})\) ‖ is the magnitude of the vector \({g}^{n}({c}_{i})\). The same holds true for \({g}^{n}({s}_{{ij}})\). The above three metrics all focus on measuring the similarity between a generated sentence and the target sentence.

Blind grading test by retinal subspecialists

We compared the reports generated by our model with those produced by recent large language models (namely GPT-431 and MiniGPT-434) and other SOTA image captioning models (NIC, Progressive Model, SCA-CNN and Bottom-up-top-down), using an evaluation dataset comprising 56 images collected by 3D-OCT 2000 and 44 images by DRI-OCT Triton in 2021. These images were inputted into our model, MiniGPT-4, GPT-4 with instructions, GPT-4 without instructions and other SOTA models, respectively, to generate diagnosis reports for each OCT image. To assess the performance of different models, two retinal subspecialists (H.C. and D.F.) independently and blindly graded these reports in random order using a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (very poor with unacceptable errors) to 5 (very good without any errors). The agreement between the two graders was evaluated using the linear weighted Kappa coefficient, and the grading of different reports was compared using the Friedman test to identify potential significant differences. Reports written by ophthalmologists for the 100 cases in the evaluation dataset were also blindly graded for comparison.

Classification metrics

Furthermore, additional experiments were conducted to evaluate the algorithm’s efficacy in pathology classification, utilizing accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. We had systematically categorized 16 distinct anatomical types, which can be further divided into 37 pathological descriptions. The reports, whether generated by our proposed method (MORG) or authored by ophthalmologists, had been classified in accordance with these descriptions. We awarded a score of 1 for reports where the semantics closely match the original clinical descriptions, and a score of 0 for those that deviate or are lacking, followed by a comprehensive computation of multi-label classification metrics, as outlined in Table 3.

Time-Efficiency assessment and Human-AI comparison

In the Time-Efficiency assessment, we invited two experienced ophthalmologists (H.C. and D.F.) to independently write or review 100 reports and record the time taken. Specifically, they were provided with 100 cases, each consisting of two representative OCT slices as like the inputs of MORG, and asked to draft reports independently, with the total time spent being recorded. After a 1-week washout period to eliminate recall bias, these 100 cases were paired with reports generated by MORG, randomized, and then presented to the same ophthalmologists again for proofreading and correction, with the total time spent once more being recorded.

In the Human-AI comparison, an independent and experienced ophthalmologist (A.L.) was invited to participate in a direct competition with our MORG system. A random selection of 217 OCT cases from 2021 was included in the study. The ophthalmologists were provided with two representative OCT slices from each case and asked to write reports based on these images, which would serve as a control to compare with the reports generated by MORG. Clinical reports, which served as the gold standard, were used to categorize and summarize the descriptions as shown in Supplementary Table 3. Several examples were shown in Supplementary Fig. 2. Each report was evaluated based on semantic consistency, with a value of 1 assigned for consistency and 0 for inconsistency or missing descriptions. Subsequently, we tallied the true positives, false positives, true negatives, and false negatives, and calculated the accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of both the human reader and our MORG system.

Reports generation using MiniGPT-4 and GPT-4

GPT-4 and MiniGPT-4 were not fine-tuned on OCT images. The MiniGPT-4 model is not open source, hence we implemented it on a local server using the publicly available code from Deyao Zhu’s team34. Then we directly input images for questioning, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 7. On the other hand, we purchased a GPT-4 premium membership and conducted experiments via API service. The following prompts were given to GPT-4 and MiniGPT-4, along with 100 OCT images: “These are a pair of cross-sectional images from a retinal optical coherence tomography scan. Please answer the following three questions in Chinese: 1. Describe its structure and form. 2. Indicate any abnormalities or lesions that may be present. 3. Give the most likely diagnosis of eye disease.” To enhance the performance of GPT-4, we strategically employed prompt engineering, fine-tuning it with specific instructions and sample data52,53. Before tasking GPT-4 with generating reports from a patient’s OCT images, we curated a subset of 4–10 OCT image pairs, along with their corresponding ophthalmologist-authored reports from our training data, to educate the model. Given the constraints on GPT-4’s input capacity, we were unable to load further training data for its learning process. To overcome this, we introduced an additional prompt urging GPT-4 to leverage the insights gained from the sample reports, stating, “Please apply the knowledge you’ve acquired from these exemplar reports.”

Data availability

The whole dataset supporting the findings of the current study are not publicly available due to the confidentiality policy of the National Health Commission of China and institutional patient privacy regulation. We will release 100 paired of OCT images, together with the reports written by ophthalmologists, generated by MORG and LLMs, and their scores graded by two retinal specialists. This data is available at (https://github.com/Poizon1213/Retinal_OCT_Report_Automatic_Generation/tree/master/data/100crop).

Code availability

All experiments were conducted using Python 3.9.17, with PyTorch 2.0.1 (compiled with CUDA 11.8) for GPU acceleration. NumPy 1.22.4 was used for data preprocessing, and the system was run on a machine with CUDA 12.2 installed. The source code for model training and evaluation, along with the specific software versions, is available at (https://github.com/Poizon1213/Retinal_OCT_Report_Automatic_Generation).

Notes

The bold values indicate the highest values for the respective metrics.

The bold values indicate the highest values for the respective metrics.

References

Fleckenstein, M., Schmitz-Valckenberg, S. & Chakravarthy, U. Age-related macular degeneration: a review. JAMA 331, 147–157 (2024).

Zhang, G., Chen, H., Chen, W. & Zhang, M. Prevalence and risk factors for diabetic retinopathy in china: a multi-hospital- based cross-sectional study. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 101, 1591–1595 (2017).

Huang, D. et al. Optical coherence tomography. Science 254, 1178–1181 (1991).

Lin, A. et al. Research trends and hotspots of retinal optical coherence tomography: a 31 year bibliometric analysis. J. Clin. Med. 11, 5604 (2022).

Khan, A., Sohail, A., Zahoora, U. & Qureshi, A. S. A survey of the recent architectures of deep convolutional neural networks. Artif. Intell. Rev. 53, 5455–5516 (2020).

Barua, P. D. et al. Multilevel deep feature generation framework for automated detection of retinal abnormalities using oct images. Entropy 23, 1651 (2021).

Shen, E. et al. DRFNet: a deep radiomic fusion network for nAMD/PCV differentiation in oct images. Phys. Medicine Biol. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6560/ad2ca0 (2024).

Wang, M. et al. Self-guided optimization semi-supervised method for joint segmentation of macular hole and cystoid macular edema in retinal oct images. In IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering, 70 (2023).

Huang, H. et al. Algorithm for detection and quantification of hyperreflective dots on optical coherence tomography in diabetic macular edema. Front. Med. 8, 688986 (2021).

Bai, S. & An, S. A survey on automatic image caption generation. Neurocomputing 311, 291–304 (2018).

Beddiar, D.-R., Oussalah, M. & Seppänen, T. Automatic captioning for medical imaging (mic): a rapid review of literature. Artif. Intell. Rev. 56, 4019–4076 (2023).

Tian, J., Li, C., Shi, Z. & Xu, F. A diagnostic report generator from CT volumes on liver tumor with semi-supervised attention mechanism. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2018. MICCAI 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, (eds. Frangi, A., Schnabel, J., Davatzikos, C., Alberola-López, C., Fichtinger, G.) 11071 (Springer, 2018).

Han, Z., Wei, B., Leung, S., Chung, J. & Li, S. Towards automatic report generation in spine radiology using weakly supervised framework. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2018. MICCAI 2018. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, (eds. Frangi, A., Schnabel, J., Davatzikos, C., Alberola-López, C., Fichtinger, G.) 11073 (Springer, 2018).

Liu, G. et al. Clinically accurate chest x-ray report generation. In Machine Learning for Healthcare Conference, 249–269 (PMLR, 2019).

Huang, J.-H. et al. Deepopht: Medical report generation for retinal images via deep models and visual explanation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), 2442–2452 (IEEE, 2021).

Huang, J.-H. et al. Non-local attention improves description generation for retinal images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), 1606–1615 (2022).

Vinyals, O., Toshev, A., Bengio, S. & Erhan, D. Show and tell: a neural image caption generator. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 3156–3164 (2015).

Nooralahzadeh, F., Gonzalez, N. P., Frauenfelder, T., Fujimoto, K. & Krauthammer, M. Progressive transformer-based generation of radiology reports. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2102.09777 (2021).

Chen, L. et al. Sca-cnn: Spatial and channel-wise attention in convolutional networks for image captioning. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 5659–5667 (IEEE, 2017).

Anderson, P. et al. Bottom-up and top-down attention for image captioning and visual question answering. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference On Computer Vision And Pattern Recognition, 6077–6086 (IEEE, 2018).

Zhou, Y. et al. A foundation model for generalizable disease detection from retinal images. Nature 622, 156–163 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Tian, Y., Kong, Y., Zhong, B. & Fu, Y. Residual dense network for image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference On Computer Vision And Pattern Recognition, 2472–2481 (IEEE, 2018).

Simonyan, K. & Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.1409.1556 (2014).

Gao, S.-H. et al. Res2net: A new multi-scale backbone architecture. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 43, 652–662 (2019).

Hu, J., Shen, L. & Sun, G. Squeeze-and-excitation networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference On Computer Vision And Pattern Recognition, 7132–7141 (IEEE, 2018).

Huang, G., Liu, Z., Van Der Maaten, L. & Weinberger, K. Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference On Computer Vision And Pattern Recognition, 4700–4708 (2017).

d’Ascoli, S. et al. Convit: Improving vision transformers with soft convolutional inductive biases. In International Conference on Machine Learning (PMLR, 2021).

Wang B. et al. Bridging the cross-modality semantic gap in visual question answering. In IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 4519−4531 (IEEE, 2024).

Song, J., Chen, Y., Ye, J. & Song, M. Spot-sdaptive knowledge distillation. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 31, 3359–3370 (2022).

Xu, K. et al. Show, attend and tell: neural image caption generation with visual attention. Comput. Sci. 2048, 2057 (2015).

Dai, H. et al. Auggpt: Leveraging chatgpt for text data augmentation. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.13007 (2023).

Wang, S., Zhao, Z., Ouyang, X., Liu, T., Wang, Q. & Shen, D. Interactive computer-aided diagnosis on medical image using large language models. Commun Eng. 3, 133 (2024).

Antaki, F., Chopra, R. & Keane, P. A. Vision-language models for feature detection of macular diseases on optical coherence tomography. JAMA Ophthalmol. 142, 573−576 (2024).

Zhu, D., Chen, J., Shen, X., Li, X. & Elhoseiny, M. Minigpt-4: Enhancing vision-language understanding with advanced large language models. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2304.10592 (2023).

Hu, E. J. et al. Lora: Low-rank adaptation of large language models. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2106.09685 (2021).

Houlsby, N. et al. Parameter-efficient transfer learning for NLP. In International Conference on Machine Learning, 2790−2799 (PMLR, 2019).

Rebuffi, S.-A., Bilen, H. & Vedaldi, A. Learning multiple visual domains with residual adapters. In Advances in neural Information Processing Systems 30, 506−516 (2017).

Li, X. L. & Liang, P. Prefix-tuning: Optimizing continuous prompts for generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2101.00190 (2021).

Lester, B., Al-Rfou, R. & Constant, N. The power of scale for parameter-efficient prompt tuning. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2104.08691 (2021).

Hambardzumyan, K., Khachatrian, H. & May, J. Warp: Word-level adversarial reprogramming. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2101.00190 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. GPT understands, too. AI Open 5, 208–215 (2024).

Pang, T., Li, P. & Zhao, L. A survey on automatic generation of medical imaging reports based on deep learning. Biomed. Eng. OnLine 22, 48 (2023).

Wang, M. et al. Uncertainty-inspired open set learning for retinal anomaly identification. Nat. Commun. 14, 6757 (2023).

Cai, Z., Fan, Q., Feris, R. S. & Vasconcelos, N. A unified multi-scale deep convolutional neural network for fast object detection. In European Conference on Computer Vision, 354–370 (Springer, 2016).

Qunli, Y., Xian, H. & Hong, L. Aircraft detection in remote sensing imagery with multi-scale feature fusion convolutional neural networks. Acta Geod. et. Cartogr. Sin. 48, 1266 (2019).

Qian, X., Fu, Y., Jiang, Y.-G., Xiang, T. & Xue, X. Multi-scale deep learning architectures for person re-identification. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, 5399–5408 (IEEE, 2017).

Wang, M. et al. Mstganet: Automatic drusen segmentation from retinal oct images. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 41, 394–406 (2021).

Papineni, K., Roukos, S., Ward, T. & Zhu, W.-J. Bleu: a method for automatic evaluation of machine translation. In Proceedings of the 40th annual meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 311–318 (IEEE, 2002).

Lin, C.-Y. Rouge: A package for automatic evaluation of summaries. In Text Summarization Branches Iut, 74–81 (2004).

Vedantam, R., Lawrence Zitnick, C. & Parikh, D. Cider: Consensus-based image description evaluation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 4566–4575 (IEEE, 2015).

Over, P. & Yen, J. Intrinsic Evaluation Of Generic News Text Summarization Systems. https://www.slideserve.com/oya/introduction-to-duc-2002-an-intrinsic-evaluation-of-generic-news-text-summarization-systems (2003).

White, J. et al. A prompt pattern catalog to enhance prompt engineering with chatgpt. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2302.11382 (2023).

Wang, J. et al. Prompt engineering for healthcare: Methodologies and applications. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2304.14670 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFA0701700), National Natural Science Foundation of China (U20A20170, 62371328, 61971298, 62271337, 62371326), Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province of China (BK20211308), Shantou Science and Technology Program (190917085269835), Department of Education of Guangdong Province (2024ZDZX2024), Agency for Science, Technology and Research (A*STAR) Career Development Fund (C222812010) and Central Research Fund (CRF). The funders played no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or the writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.C., H.F. and H.C. designed the research. H.C., T.L., A.Z., S.C., A.L., D.F., M.Z. and C.P.P. provided data. J.W., M.W., Q.C., C.L., T.W., C.G., Y.Z. and Y.P. implemented all the experiments. H.C., J.W., T.L., T.W., W.Z., F.S., D.X., and B.N. analyzed and discussed the experimental results. X.C., H.F., Z.C., J.W. and Y.Z. prepared the manuscript. All authors have commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Fu, H., Wang, J. et al. A deep learning based automatic report generator for retinal optical coherence tomography images. npj Digit. Med. 8, 618 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01988-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01988-2