Abstract

The optimal treatment for esophageal cancer (EC) invading the muscularis mucosa (T1a-M3) or submucosa (T1b) remains debated. This study analyzed patients with stage T1a-M3/T1b EC from the SEER database (cycle 2004–2017). Cancer-specific survival (CSS) and overall survival (OS) were compared across five groups. Primary analysis used stable inverse probability treatment weighting (sIPTW), while sensitivity analysis applied propensity score matching (PSM) and external datasets. After sIPTW adjustment, endoscopic therapy showed significantly better CSS and OS than chemoradiotherapy (CRT) (both P < 0.0001). Compared to radical resection, endoscopic treatment had superior CSS (P = 0.038) without observed significant difference in OS (P = 0.50). Four variable selection methods built the optimal predictive model, validated internally and externally. Internal AUC values at 1, 3, and 5 years were 0.730, 0.743, and 0.769, respectively; external AUC values were 0.765, 0.731, and 0.785.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Esophageal cancer (EC) is a major contributor to the global cancer burden due to its high incidence and mortality rates1,2. As per the guidelines of the Japanese Esophageal Society, for patients diagnosed with EC that is confined to the superficial layers, endoscopic intervention is proposed as a definitive treatment. In particular, this applies to the epithelium (T1a-M1) or lamina propria (T1a-M2). Conversely, when EC invades deeper tissues such as the muscularis mucosae (T1a-M3) or submucosa (T1b), endoscopic therapy is not yet standardized due to concerns about an elevated risk of lymph node metastasis3,4. The risk associated with conventional esophagectomy, including complications, recurrence, and mortality, remains significant. Its impact on patients’ quality of life cannot be overlooked5,6,7. As an additional option for organ preservation, chemotherapy is associated with a significant local failure rate and dose-escalation-related side effects that are hard to overlook. Furthermore, there exists a notable risk of disease recurrence8,9,10,11. The most appropriate treatment for patients with T1a-M3/T1b EC has not been defined.

Given the gravity of EC disease, an increasing number of individuals are investigating the prognosis associated with various treatment modalities. McCarty et al.12 performed a stratified analysis of the outcomes for stage I EC patients using data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Database covering the period from 2004 to 2015. According to Min et al.13, for patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) lacking endoscopic evidence of obvious submucosal invasion, Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) can offer long-term outcomes similar to those of esophagectomy.

Numerous models have been developed for the prognosis or adjuvant treatment of EC. Jia et al.14 created a model for predicting the survival for early-stage EC. However, the article lacks external validation and thus appears to lack some conviction. Moreover, the cancer stage of the model developed by the general article lacks specificity15,16,17,18. There are also some studies focusing on the evaluation of the risk of lymphatic metastasis and chemotherapy-related death19,20,21,22. At present, in this field, there is a deficiency of comprehensive models which are able to integrate clinical factors in a systematic way.

The SEER database was utilized in this research to assess the survival results of patients having T1a-M3/T1b EC and receiving various treatment methods. After that, a user-friendly web-based platform was developed with the aim of predicting the survival of those diagnosed with stage T1a-M3/T1b EC.

Results

Patient characteristics

The research encompassed 1199 patients who were diagnosed with T1a-M3/T1bWC. The characteristics of these patients were outlined according to their treatment methods and the extent of tumor invasion (Table 1 and Tables S1–S3). These observed variations were consistent with the distinct epidemiological features of the region.

Comparative analysis of survival outcomes before adjustment

The research divided participants into five groups based on treatment methods. Table S4 details the 5-year OS and CSS rates. Compared to CRT, endoscopic therapy, esophagectomy, esophagectomy with CRT, and endoscopic therapy with CRT showed significant survival benefits. Specifically, endoscopic therapy (HR: 1.61; 95% CI, 1.46–1.79; P < 0.0001 for CSS; HR: 1.33; 95% CI, 1.24–1.43; P < 0.0001 for OS), esophagectomy (HR: 2.20; 95% CI, 1.89–2.56; P < 0.0001 for CSS; HR: 2.11; 95% CI, 1.86–2.39; P < 0.0001 for OS), esophagectomy with CRT (HR: 3.61; 95% CI, 2.18–5.99; P < 0.0001 for CSS; HR: 3.17; 95% CI, 2.12–4.75; P < 0.0001 for OS), and endoscopic therapy with CRT (HR: 1.38; 95% CI, 1.12–1.70; P = 0.0016 for CSS; HR: 1.18; 95% CI, 1.02–1.37; P = 0.024 for OS) all demonstrated better outcomes. Notably, no significant difference in CSS was found between endoscopic therapy and esophagectomy (HR: 1.18; 95% CI, 0.99–1.39; P = 0.059), but lower in OS (HR: 0.81; 95% CI, 0.73–0.90; P < 0.0001).

When comparing CSS in endoscopic therapy versus esophagectomy combined with CRT, superior long-term survival benefits were observed (HR: 1.24; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.48; P = 0.012), while OS was similar (HR: 0.97; 95% CI, 0.86 to 1.10; P = 0.63). Endoscopic therapy combined with CRT showed lower long-term survival in compared to endoscopic therapy (HR: 2.59; 95% CI, 1.36 to 4.94; P = 0.0028 for CSS; HR: 1.95; 95% CI, 1.29–2.96; P = 0.0014for OS) and esophagectomy (HR: 0.53; 95% CI, 0.30 to 0.96; P = 0.032; HR: 0.36; 95% CI, 0.24–0.53; P < 0.0001 for OS). There was no significant difference in CSS between endoscopic therapy combined with CRT and esophagectomy combined with CRT (HR: 0.81; 95% CI, 0.57 to 1.17; P = 0.27), but OS was significantly better for the former (HR: 0.68; 95% CI, 0.52 to 0.88; P = 0.0027). Lastly, no significant difference in CSS or OS was found between esophagectomy and esophagectomy combined with CRT. All Kaplan-Meier curves illustrating these CSS and OS results are shown in Figs. S1–2.

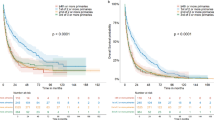

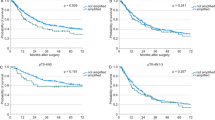

Comparative analysis of survival outcomes based on sIPTW adjustment

After sIPTW adjustment, the CSS and OS results for endoscopic therapy, esophagectomy and esophagectomy compared with CRT remained consistent with unadjusted results. Notably, endoscopic therapy plus CRT showed a significant CSS benefit over CRT alone (HR: 2.96; 95% CI, 1.41–6.21; P = 0.0036), but OS was similar (HR: 1.54; 95% CI, 0.95–2.49; P = 0.80). Adjusted CSS results indicated that endoscopic therapy had a statistically significant survival advantage over esophagectomy and esophagectomy combined with CRT (HR: 0.60; 95% CI, 0.36–1.00; P = 0.038 and HR: 2.55; 95% CI, 1.31–5.00; P = 0.0068), while OS remained comparable (HR: 1.11; 95% CI, 0.82–1.50; P = 0.50 and HR: 1.07; 95% CI, 0.63–1.80; P = 0.80).

When comparing CSS between endoscopic therapy combined with CRT and esophagectomy, no significant differences were found (HR: 1.15; 95% CI, 0.44 to 3.00; P = 0.78). However, esophagectomy showed a significant advantage in OS (HR: 2.46; 95% CI, 1.37 to 4.42; P = 0.001). There were no notable differences in CSS or OS between endoscopic therapy alone vs. combined with CRT, or esophagectomy alone vs. combined with CRT. Comparing CSS and OS between endoscopic therapy combined with CRT and esophagectomy combined with CRT yielded the same results as before. These findings are summarized in Figs. 1 and 2, with covariate balance data in Tables S5–14.

Survival outcomes of different treatments: endoscopic therapy and esophagectomy (a), endoscopic therapy and CRT (b), endoscopic therapy and endoscopic therapy combined with CRT (c), endoscopic therapy and esophagectomy combined with CRT (d), endoscopic therapy combined with CRT and esophagectomy (e), endoscopic therapy combined with CRT and esophagectomy combined with CRT (f), endoscopic therapy combined with CRT and CRT (g), esophagectomy and CRT (h), esophagectomy and esophagectomy combined with CRT (i), and esophagectomy combined with CRT and CRT (j). sIPTW stabilized inverse probability of treatment weighting, CSS cancer-specific survival, CRT chemoradiotherapy.

Survival outcomes of different treatments: endoscopic therapy and esophagectomy (a), endoscopic therapy and CRT (b), endoscopic therapy and endoscopic therapy combined with CRT (c), endoscopic therapy and esophagectomy combined with CRT (d), endoscopic therapy combined with CRT and esophagectomy (e), endoscopic therapy combined with CRT and esophagectomy combined with CRT (f), endoscopic therapy combined with CRT and CRT (g), esophagectomy and CRT (h), esophagectomy and esophagectomy combined with CRT (i), and esophagectomy combined with CRT and CRT (j). sIPTW stabilized inverse probability of treatment weighting, OS overall survival, CRT chemoradiotherapy.

Comparative analysis of survival outcomes based on PSM

In this study, PSM serves as an auxiliary sensitivity analysis method, effectively balancing covariates between groups (Tables S15–S24). The CSS results from the PSM analysis were largely in agreement with those obtained through sIPTW, thereby reinforcing the reliability of our analytical methods. The Kaplan–Meier survival curves for both CSS and OS following PSM adjustment are illustrated in Figs. S3 and S4.

Comparative analysis of survival outcomes based on histological stratification

In the subgroups categorized by EA and ESCC, the key pathological characteristics are summarized in Tables S25–26. Among 199 patients with squamous cell carcinomas, after adjustment using sIPTW analysis, no significant differences were observed in CSS and OS between endoscopic therapy and esophagectomy (HR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.23 to 1.93; P = 0.43 and HR: 1.12; 95% CI: 0.58 to 2.17; P = 0.8). Endoscopic therapy showed a notable survival benefit in CSS compared to CRT (HR: 4.11; 95% CI: 1.22 to 13.84; P = 0.049), whereas OS remained comparable (HR: 1.74; 95% CI: 0.85 to 3.56; P = 0.19).

For the 999 patients with adenocarcinoma, both CSS and OS were significantly higher in the endoscopic therapy group compared to the CRT group (HR: 8.72; 95% CI: 4.90 to 15.52; P < 0.0001 for CSS and HR: 4.49; 95% CI: 2.86 to 7.05; P < 0.0001 for OS). The CSS analysis indicated that endoscopic therapy provided a survival advantage over esophagectomy (HR: 0.57; 95% CI: 0.36 to 0.91; P = 0.045), while OS did not differ significantly (HR: 1.14; 95% CI: 0.83 to 1.57; P = 0.42). All Kaplan-Meier survival curves and corresponding tables for CSS and OS are presented in Figs. S5–S8 and Tables S27–S46.

Comparative analysis of survival outcomes based on time and surgical procedures

Based on the development tendency of therapeutic strategy for ER at different phases, we completed subgroup analysis stratified with three intervals (cycle 2004–2008, cycle 2009–2013, and cycle 2014–2017) to interpret the dynamics, providing survival evaluation of the same treatment paradigm across subsequent eras and verified the advantages of endoscopic therapy (Table S47).

According to different risks of postoperative complications and mortality among patients caused by varying degrees of organ preservation, we categorized esophagectomy into three subgroups: code A300 (partial esophagectomy) as the first category; code A400 (total esophagectomy) as the second; and codes A500–A550 along with code A800 (esophagectomy combined with resection of other organs). Subgroup analyses was performed to further clarify the consistence among different approaches of esophagectomy (Table S48–49).

Comparative analysis of survival outcomes from an external database

We gathered data from 121 patients diagnosed with T1a-M3/T1b EC who were treated at our hospital between 2015 and 2019, forming an external validation cohort. The baseline characteristics of this external dataset are summarized in Tables S50–51. Endoscopic therapy demonstrated superior outcomes in both CSS and overall OS compared to CRT (HR: 2.55; 95% CI: 1.71 to 3.81; P < 0.0001 for CSS, and HR: 2.19; 95% CI: 1.59 to 3.00; P < 0.0001 for OS). In comparison with esophagectomy, endoscopic therapy provided a significant survival advantage in CSS (HR: 3.92; 95% CI: 0.97 to 15.79; P = 0.038), while no statistically significant differences were observed in OS (HR :1.28; 95% CI: 0.46 to 3.55; P = 0.63). These findings are illustrated in Figs. S9–10.

Prediction model development

The training cohort comprised 959 patients with EC identified from the total data set was randomly divided into 80%, the internal validation cohort was 20%, a total of 240 patients. While validation cohort 2 encompassed 121 patients exclusively treated at our hospital. These cohorts collectively represented a diverse population of EC patients.

Univariate Cox regression analysis was employed to identify risk factors for variable screening (Table S52), with six relevant variables selected: age, therapy, MHI, sex, grade, and histology. BSR was then utilized to optimize the maximum R2 value and determine the best combination of variables, resulting in the selection of age, therapy, grade, histology, MHI, DTTT, and race (Fig. S11A). LASSO regression combined with cross-validation was applied to determine the variable combination corresponding to the smallest mean square error (MSE), as depicted in Fig. S11B, C, three variables were retained: MHI, age, and histology (Table S53). The variables ascertained via the aforementioned three methodologies were integrated into the multivariate Cox regression analysis and construct models. The ultimate determination of variables for constructing the model relied upon stepwise backward by using the function “step”, employing the minimized value of the Akaike information criterion (AIC). After excluding sex from consideration, a further reduction in AIC value occurred—from 6115.59 to 6113.69 in the Cox group. The AIC value in BSR decreased from 6122.13 to 6113.69 after excluding DTTT and race. The variables selected by LASSO regression were not excluded, and the AIC value was 6162.74. we incorporated an additional Boruta to identify the candidate variables: age, therapy, histology, grade, race and DTTT. Following AIC comparison (6124.04 vs. 6116.87), the final model was refined to include age, therapy, histology and grade (Fig. S11D).

Subsequently, we selected variables that were consistently identified across multiple screening approaches and exhibited clinical relevance with verified prognostic significance in reported literature. As the result, gender and treatment interval were comprised. Meanwhile, it is important to note that race was excluded from the final model due to its limited generalizability and inability to be validated in external cohorts.

Consequently, a final prediction model with seven variables (age, grade, histological, MHI, therapy, sex and DTTT) was constructed to forecast OS at 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year intervals, as depicted in Fig. S11E.

Predictive performance of the model

We incorporated selected factors to conduct our predictive prognostic model with AUC scores of 0.715, 0.726, and 0.746 for predicting outcomes at 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year intervals (Fig. 3a). In this study, the model was internally validated through a 10-fold cross-validation method repeated 200 times (Fig. S12). The validation yielded demonstrated AUC scores of 0.704, 0.698, and 0.719 at 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year intervals, respectively. Furthermore, the C-index values were recorded as 0.690, 0.675, and 0.674 for these time points. In the internal validation group, the AUC values for 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year predictions were 0.730, 0.743, and 0.769, while in the external validation group, they were 0.765, 0.731, and 0.785 (refer to Fig. 3b, c). The calibration curves for the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year predictions showed minimal variations across all training and validation datasets (Fig. 3d–l), suggesting a strong alignment between the predicted and observed outcomes.

ROC curves showing the predictive performances of the model in the internal training group (a), internal validation group (b), and external validation group (c), respectively. Calibration chart depicting the 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year OS rates of T1a-M3/T1b esophageal cancer patient model. In the training group (d–f), validation 1 group (g–i), and validation 2 group (j–l). OS overall survival, ROC receiver operating characteristic, OS overall survival.

Dynamic model website

The webpage functions as an advanced instrument for forecasting the long-term survival outcomes of patients with stage T1a-M3/T1b EC, utilizing a sophisticated prediction model. Users can access interactive visualizations at https://ziqichen1.shinyapps.io/dynnomapp/. Additionally, the algorithm underlying the model can be refined and updated dynamically in response to feedback gathered from its ongoing applications.

Discussion

Our study showed a significant survival advantage with endoscopic therapy compared to esophagectomy and CRT for T1a-M3/T1b EC patients after sIPTW adjustment. These results were confirmed in the PSM-adjusted cohort, systematic subgroup analysis and external validation, reinforcing our conclusions.

The incidence of T1a-M3 lymph node metastasis and invasion observed in surgical specimens significantly varies from that detected in endoscopic specimens23,24, with markedly higher rates reported among surgically treated cases23,25. The role of endoscopic in estimating depth of invasion of T1-M3-SM1 or deeper remains uncertain26. This disparity likely stems from differences in histopathological diagnostic methods between surgical and endoscopic specimens. Surgical specimens, being larger, may lead to mistakes in diagnosing T1a-M3 cases as T1b4,27,28. The depth of invasion beyond T1a-M3 was identified as an important predictor for lymph node metastasis with an equivalent risk of metastasis to that observed in cases with T1b-SM123,25,29,30, introducing rationality to integrating both groups together as our target population.

Our findings aligned with majority of prior studies regarding the long-term survival outcomes of various treatment approaches31,32,33,34. Katy A Marino et al.35 found that the postoperative survival rate showed comparability between the endoscopic treatment group and the esophagectomy group in patients with T1a adenocarcinoma (P = 0.003). In a recent analysis, patients with T1a or T1b ESCC who underwent ESD showed no significant difference in OS, cancer recurrence, or metastasis compared to those treated with esophagectomy36. Our study included a larger cohort of patients undergoing various treatments compared to previous studies. By using sIPTW and PSM methods to assess datasets while considering EC’s relative indication range, our research provided more clinically practical and reliable results.

It is worth noting that, considering the variations in various subgroups, we performed systematic subgroup analyses with specific emphasis on histological stratification, time and surgical procedures. Results in divided cohorts adjusted by sIPTW method indicated the stability of our findings. Furthermore, when applied across diverse regions, the model’s internal and external validation cohorts demonstrated favorable performance. These observations further emphasized the robustness and highlight the extensive potential applicability of our study.

In a prospective study conducted by Keiko et al.37 from 2006 to 2012, the endoscopic therapy combined with selective CRT suggested comparable results to surgery in 176 T1b (SM1–SM2) ESCC patients. Kenji Yamauchi et al.38 designed a retrospective analysis and concluded that ESD alone or combined with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy may be considered viable treatment options for M3 and SM1 ESCC patients. Through the comparison between the CSS of endoscopic therapy and CRT or esophagectomy in our study, we further validated above results in previous studies and highlighted the value of endoscopic treatment. Despite of the conclusion obtained in a recent randomized controlled parallel-group ESORES trial which verified the therapeutic efficacy of CRT, we noted that heterogeneity in the applicable population39, potential micrometastases and completion rates of the strategy might introduce the contradiction, ER is an initial diagnostic tool and a potential curative method, characterized with relatively low costs and high accessibility in more medical settings. Meanwhile, ESD is preferred for its superior curative resection and reduced local recurrence rate compared with CRT, especially for lesions >15 mm. Though it is widely accepted that ER alone is inadequate for patients with deep submucosal invasion), lymphovascular invasion, or poor differentiation, we find difficultly evaluating the depth of the tumor before ER in clinical practice.

Interestingly, the CSS was significant for endoscopic therapy over esophagectomy but not the OS. This might be explained by competing mortality in patients with EC especially those undergoing endoscopic therapy. Patients with superficial esophageal cancer, especially those suitable for endoscopic treatment, are typically elderly and often have multiple comorbidities. In this group, the risk of death from cardiovascular or respiratory disease, other cancers, or non-esophageal cancer-related causes may be as high as, or higher than, the risk from esophageal cancer itself. Endoscopic treatment, being minimally invasive, greatly reduces the risk of perioperative death and severe treatment-related complications, thereby lowering early cancer-specific mortality. This is the main reason for the significant improvement in CSS. In contrast, esophagectomy is a highly invasive procedure with significant perioperative mortality and morbidity. Most of these deaths were directly linked to cancer treatment, which greatly reduced early CSS in the esophagectomy group. In our analysis, we clarified that influence of the treatment methods’ on CSS was associated with the threshold value at 65 years old (Table S54). Ultimately, younger age and fewer comorbidities were associated with better overall survival.

The variables commonly used as significant prognostic indicators in numerous studies include histology, grade, age, and therapy15,40,41,42. Calvin et al.43 found that lower median household income was associated with higher cancer-specific mortality and lower endoscopic resection rates in T1aN0M0 esophageal adenocarcinoma. Our aticle also suggested that MHI served as a significant predictor within the model. Specifically, we found that higher-income individuals were less likely to receive chemoradiotherapy in healthcare systems where patients bear the cost of treatment (Table S55). This finding indicates that economic factors represent a significant barrier to treatment selection within specific healthcare financing models.

There exists obvious inconsistencies in the selection criteria for therapeutic approaches of T1a-M3/T1b EC patients among different countries’ treatment guidelines. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend endoscopic resection for superficial ESCC confined to the mucosa (T1a), and esophagectomy in cases with submucosal invasion44. Differently, the Japan Esophageal Society defined mucosal cancer limited to the lamina propria as an absolute indication for endoscopic resection on account of its low potential for lymph node metastasis45. And the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy suggested lamina propria invasion without evidence of lymph node metastasis as an absolute indication for endoscopic treatment similarly46. Based on our comprehensive analyses and subsequent discussion, endoscopic treatment will be reasonably recommended as both an initial diagnostic modality and a potential therapeutic approach for patients with T1a-M3/T1b EC on account of the lower lymph node metastasis rate in this population, the current limitations of non-invasive preoperative staging, reduced procedural risk, fewer complications, broader availability across healthcare settings, and cost-effectiveness. In the United States, the utilization of endoscopic treatment for T1b EC increased significantly from 6.6% in 2004 to 20.9% in 201047. This upward trend reflected growing clinical acceptance driven by advances in endoscopic imaging and resection techniques, as well as the centralisation of endoscopic treatments—factors that collectively contributed to improved survival outcomes. Our study, validated through both internal and external cohorts, provided significant evidence for the selection of diagnostic and therapeutic strategies for superficial EC. Nevertheless, further multicenter, large-sample prospective studies are warranted to confirm these findings and refine strategic criteria.

Our study possesses several distinctive features: (1) We conducted a comprehensive analysis of treatment outcomes for the controversial stage T1a-M3/T1b, incorporating a detailed treatment classification that was not present in previous studies. (2) The collected clinical variables encompass not only conventional patient data but also socioeconomic factors. This integration enables our model to incorporate both clinical and social realities, thereby providing tailored prognoses for patients with diverse social circumstances. (3) For the first time, we have created a range of intuitive web-based prediction tools designed for endoscopic procedures, surgical applications, and comprehensive global patient care. Despite the patient data used for developing and validating the model being restricted to two specific regions, no significant regional variations were noted in the diagnostic and therapeutic approaches for EC across various locations. This suggests that our model exhibits wide-ranging applicability. Additionally, visual interfaces improve patients’ understanding of their condition’s severity and foster more effective doctor-patient communication and collaborative care.

This research acknowledges several inherent limitations. First, we must acknowledge that the SEER database has limitations, including gaps in sociodemographic information, data on metastasis, and data on lymphovascular invasion, which limit the scope of some analyses. Second, the relatively small size of the external validation cohort might affect the evaluation of model performance on independent datasets. Considering the variability in clinical data across different healthcare settings, developing a robust predictive model that can be effectively generalized to multiple centers poses a significant challenge.

In summary, this study developed a predictive model for T1a-M3/T1b EC patients validated its exceptional predictive performance, and established a dedicated webpage. The results of our study indicate that endoscopic therapy exhibits superior long-term survival outcomes in comparison to CRT and is comparable to esophagectomy.

Methods

Patients

The SEER database, which gathers comprehensive registry data from 18 U.S. cancer registries, was the source of the data used in this study. The criteria for choosing the participants were as shown below: (1) patients with a diagnosis of T1a-M3/T1b EC, having no regional lymph node involvement or distant metastasis between 2004 to 2017;(2) individuals who underwent endoscopic therapy, esophagectomy, or CRT, but did not receive preoperative neoadjuvant treatment; (3) availability of clinical details such as treatment type, tumor location, and survival duration; (4) existence of follow-up documentation; (5) diagnosis verified by autopsy or death certificate. The approval from the Ethics Committee (2024ZDSYLL281-P01) confirmed that this research follows the ethical standards set out in the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent revisions, as this was a retrospective study, the ethics committee waived the requirement for informed consent. Meanwhile, we registered and gained access to the SEER database, and no additional ethical statements were required for the use of publicly available data.

Variables

In the SEER database, the codes for the depth of invasion categorized as T1a-M3/T1b are 120, 160, and 165. These codes correspond to invasions of the muscularis mucosae, submucosa, and T1b classification without further extension details, respectively. For endoscopic therapy, the surgical codes fall within the ranges of A100-A140 and A200-A270. Codes A100 through 14 stands for local tumor destruction processes in which no specimens were sent for pathological examination, like photodynamic therapy, electrocautery, cryotherapy and laser ablation. Codes A200 to A270 are used to represent local tumor excision operations in which samples were dispatched for pathological examination. A300 to A800 indicated surgical procedure methods for esophagectomy: A300 Partial esophagectomy; A400 Total esophagectomy, NOS; A500 Esophagectomy, NOS WITH laryngectomy and/or gastrectomy, NOS; A510 WITH laryngectomy; A520 WITH gastrectomy, NOS; A530 Partial gastrectomy; A540 Total gastrectomy; A550 Combination of A510 WITH any of A520–A540; A800 Esophagectomy, NOS.

The clinical factors obtained from the SEER database comprised the patient’s age at diagnosis, racial background, marital status, radiotherapy administration, chemotherapy administration, median household income (MHI), and the interval from diagnosis to treatment initiation (DTTT). Tumor features were categorized based on tumor size (>2 cm versus ≤2 cm) and tumor grade (including well-differentiated [Grade I], moderately differentiated [Grade II], poorly differentiated [Grade III], undifferentiated [Grade IV], and those with unknown differentiation). Utilizing the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology, Third Edition (ICD-O-3), histological types were classified into three groups: adenocarcinoma (EA), characterized by specific codes (8140-8145,8210,8211,8255,8260,8261,8263,8310,8480,8481,8490, and 8574); esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC), identified through codes (8050-8052,8070-8076,8083, and 8084); and other unspecified types. Primary tumor locations were divided into eight categories. Details regarding survival status, survival length, and causes of death were included in the follow-up data. The two main outcomes for the survival analysis were 5-year cancer-specific survival (CSS) and 5-year overall survival (OS).

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented in terms of mean and standard deviation or median along with inter - quartile range (IQR) for the reporting of findings. For categorical variables, frequencies and percentages are used for description. The Mann-Whitney U test was employed to analyze continuous data. For categorical data, Fisher’s exact test was used for examination. In order to check the long-term impacts on OS and CSS. The K-M survival curves were made use of. Survival differences among groups were assessed through the log-rank test. This retrospective study utilized three analytical approaches for comparative analysis: unadjusted analysis, propensity score matching (PSM), and stabilized inverse probability treatment weighting (sIPTW). Sensitivity analyses were carried out using the PSM (1:1 ratio) method and the hospital cohort. Given its capacity to control confounding factors, keep the sample size consistent and minimize false positives, the sIPTW method has been selected as the main analytical method,

Univariate Cox regression, best subset selection (BSR), Borut algorithm and cross-validated LASSO regression were utilized for the initial variable screening. Model selection was based on AUC evaluation. Then, multivariate Cox regression was utilized to refine the prediction model according to Akaike information criterion (AIC) values. To conduct internal verification, 10-fold cross-validation with 200 repetitions was utilized. The C-index, ROC, and calibration curves in both training and validation datasets were used to assess the model performance at 1, 3, and 5 years. A two-sided significance level of 0.05 was set for all statistical analyses. The analysis process flowchart is presented in Fig. 4.

Data availability

The dataset, code, algorithm files, and anonymized results utilized in this study are not publicly accessible. Nevertheless, these materials can be made available upon reasonable request to the corresponding authors. All data acquisition was completed by 2024.

References

Lagergren, J., Smyth, E., Cunningham, D. & Lagergren, P. Oesophageal cancer. Lancet 390, 2383–2396 (2017).

He, S., Xu, J., Liu, X. & Zhen, Y. Advances and challenges in the treatment of esophageal cancer. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 11, 3379–3392 (2021).

Kitagawa, Y. et al. Esophageal cancer practice guidelines 2017 edited by the Japan Esophageal Society: part 1. Esophagus 16, 1–24 (2019).

Kitagawa, Y. et al. Esophageal cancer practice guidelines 2017 edited by the Japan esophageal society: part 2. Esophagus 16, 25–43 (2019).

Kanie, Y. et al. Additional treatment following noncurative endoscopic resection for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a comparison of outcomes between esophagectomy and chemoradiotherapy. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 28, 8428–8435 (2021).

Baba, Y. et al. Prognostic impact of postoperative complications in 502 patients with surgically resected esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective single-institution study. Ann. Surg. 264, 305–311 (2016).

Mönig, S. et al. Early esophageal cancer: the significance of surgery, endoscopy, and chemoradiation. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1434, 115–123 (2018).

Hisano, O. et al. Additional radiotherapy following endoscopic submucosal dissection for T1a-MM/T1b-SM esophageal squamous cell carcinoma improves locoregional control. Radiat. Oncol. 13, 14 (2018).

Kawamoto, T., Shikama, N., Mine, S. & Sasai, K. Comparison of recurrence patterns and salvage treatments after definitive radiotherapy for cT1a and cT1bN0M0 esophageal cancer. Front. Oncol. 12, 857881 (2022).

Lyu, B. et al. Long-term clinical outcomes and safety analysis of superficial esophageal cancer patients treated with definitive or adjuvant radiotherapy. Cancers (Basel) https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14143423 (2022).

Matsuda, S. et al. Clinical significance of endoscopic response evaluation to predict the distribution of residual tumor after neoadjuvant chemotherapy for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 29, 2673–2680 (2022).

McCarty, J. C. et al. A retrospective cohort study of endoscopic therapy and esophagectomy for stage 1 esophageal cancer: less is more. Gastrointest. Endosc. 92, 23–30 (2020).

Min, Y. W. et al. Comparison of endoscopic submucosal dissection and surgery for superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a propensity score-matched analysis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 88, 624–633 (2018).

Jia, R., Xiao, W., Zhang, H. & Yu, Z. Comparative study of treatment options and construction nomograms to predict survival for early-stage esophageal cancer: a population-based study. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 56, 635–646 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. Construction and verification of prognostic nomogram for early-onset esophageal cancer. Bosn. J. Basic Med Sci. 21, 760–772 (2021).

Shi, M., Tang, J. W. & Cao, Z. R. Nomograms for predicting survival in early-onset esophageal cancer. Expert Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 15, 437–446 (2021).

Kunzmann, A. T. et al. Model for Identifying Individuals at risk for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16, 1229–1236.e1224 (2018).

Sun, W., Zhang, X. & Qiu, Z. Survival trends and conditional survival in primary non-metastatic esophageal cancer: a SEER population-based study and external validation. Transl. Cancer Res. 12, 2693–2705 (2023).

Chen, H. et al. Clinical models to predict lymph nodes metastasis and distant metastasis in newly diagnosed early esophageal cancer patients: a population-based study. Cancer Med. 12, 5275–5292 (2023).

Lv, X. et al. Development and validation of a nomogram model for the risk of cardiac death in patients treated with chemotherapy for esophageal cancer. Cardiovasc. Toxicol. 23, 377–387 (2023).

Ding, M. et al. Integrating preoperative computed tomography and clinical factors for lymph node metastasis prediction in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by feature-wise attentional graph neural network. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 116, 676–689 (2023).

Li, X. et al. Impact of chemotherapy and radiotherapy on the survival of elderly esophageal cancer patients undergoing surgery: a SEER database analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 21, 430 (2021).

Akutsu, Y. et al. The overall prevalence of metastasis in T1 esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective analysis of 295 patients. Ann. Surg. 257, 1032–1038 (2013).

Katada, C. et al. Clinical outcome after endoscopic mucosal resection for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma invading the muscularis mucosae-a multicenter retrospective cohort study. Endoscopy 39, 779–783 (2007).

Eguchi, T. et al. Histopathological criteria for additional treatment after endoscopic mucosal resection for esophageal cancer: analysis of 464 surgically resected cases. Mod. Pathol. 19, 475–480, https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.3800557 (2006).

Pimentel-Nunes, P. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial gastrointestinal lesions: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline - Update 2022. Endoscopy 54, 591–622 (2022).

Oesophago-Gastric Anastomotic Audit (OGAA) Collaborative: Writing Committee; Steering Committee; National Leads; Site Leads; Collaborators. Mortality from esophagectomy for esophageal cancer across low, middle, and high-incomecountries: An international cohort study. Eur J Surg Oncol 47, 1481−1488 (2021).

Lewis, J. T., Wang, K. K. & Abraham, S. C. Muscularis mucosae duplication and the musculo-fibrous anomaly in endoscopic mucosal resections for barrett esophagus: implications for staging of adenocarcinoma. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 32, 566–571 (2008).

Kim, D. U. et al. Risk factors of lymph node metastasis in T1 esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 23, 619–625 (2008).

Choi, J. Y. et al. Feasibility of endoscopic resection in superficial esophageal squamous carcinoma. Gastrointest. Endosc. 73, 881–889 (2011). 889.e881-882.

Zhu, J. et al. Endoscopic therapy versus esophagectomy for T1bN0M0 esophageal cancer: a population-based study using propensity score matching. Heliyon 9, e22189 (2023).

Wirsching, A. et al. Endoscopic therapy and surveillance versus esophagectomy for early esophageal adenocarcinoma: a review of early outcomes and cost analysis. Am. J. Surg. 218, 164–169 (2019).

Otaki, F. et al. Outcomes of patients with submucosal (T1b) esophageal adenocarcinoma: a multicenter cohort study. Gastrointest. Endosc. 92, 31–-39.e31 (2020).

Noordzij, I. C., Hazen, M. L., Nieuwenhuijzen, G. A. P., Verhoeven, R. H. A. & Schoon, E. J. Endoscopic therapy replaces surgery for clinical T1 oesophageal cancer in the Netherlands: a nationwide population-based study. Surg. Endosc. 37, 4535–4544 (2023).

Marino, K. A., Sullivan, J. L. & Weksler, B. Esophagectomy versus endoscopic resection for patients with early-stage esophageal adenocarcinoma: a National Cancer Database propensity-matched study. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc Surg. 155, 2211–2218.e2211 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Outcomes of endoscopic submucosal dissection vs esophagectomy for T1 esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in a real-world cohort. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 17, 73–81.e73 (2019).

Minashi, K. et al. Efficacy of endoscopic resection and selective chemoradiotherapy for stage I esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Gastroenterology 157, 382–390.e383 (2019).

Yamauchi, K. et al. Long-term outcomes of endoscopic versus surgical resection for MM-SM1 esophageal squamous cell carcinoma using propensity score analysis. Esophagus 18, 72–80 (2021).

Weis, J. et al. Study protocol of a prospective multicenter study on patient participation for the clinical trial: surgery as needed versus surgery on principle in Post-Neoadjuvant Complete Tumor Response of Esophageal Cancer (ESORES). Front. Oncol. 11, 789155 (2021).

Qian, H. et al. Clinical characteristics, prognosis, and nomogram for esophageal cancer based on adenosquamous carcinoma: a SEER database analysis. Front. Oncol. 11, 603349 (2021).

Hu, B., Zhu, Y. & Wu, X. Comparison of prognostic factors of esophageal cancer between a Chinese cohort and the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database: a retrospective cohort study. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 13, 527–538 (2022).

Xia, L. et al. Comparison of long-term survival of neoadjuvant therapy plus surgery versus upfront surgery and the role of adjuvant therapy for T1b-2N0-1 esophageal cancer: a population study of the SEER database and Chinese cohort. Int. J. Surg. 111, 70−79 (2024).

Geng, C. X. et al. Socioeconomic disparities affect outcomes in early-stage esophageal adenocarcinoma: a SEER analysis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 21, 2797–2806.e2796 (2023).

Ajani, J. A. et al. Esophageal and esophagogastric junction cancers, version 1.2015. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 13, 194–227 (2015).

Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer, 11th Edition: part I. Esophagus 14, 1–36 (2017).

Pimentel-Nunes, P. et al. Endoscopic submucosal dissection: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline. Endoscopy 47, 829–854 (2015).

Merkow, R. P. et al. Treatment trends, risk of lymph node metastasis, and outcomes for localized esophageal cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/dju133 (2014).

Acknowledgements

This work were funded by Zhongda Hospital Affiliated to Southeast University, Jiangsu Province High-Level Hospital Construction Funds (2024GSPKY06), and Jiangsu Provincial Special Program of Medical Science (BE2019710).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Aijing Zhu: Formal analysis, Writing original draft, Review & Editing. Shu Huang: Formal analysis, Software, Writing original draft, Review & Editing. Shuaijing Huang: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing original draft. Yang Zhou, Yan Liang: Validation, Review & Editing, Supervision. Chunxiao Yue, Xiaoyu Bai: Resources, Data Curation. Jiawei Li: Formal analysis, Investigation, Resources. Yadong Feng: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Funding acquisition, Writing Review & Editing. All authors provided critical revisions of the manuscript and approved the final version of submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, A., Huang, S., Huang, S. et al. Therapeutic outcomes of different treatment approaches for T1a-M3/T1b esophageal cancer and development of a prognostic prediction model. npj Digit. Med. 8, 670 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02045-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02045-8