Abstract

Colonoscopic withdrawal time is crucial for achieving a high adenoma detection rate (ADR) and reducing post-colonoscopy colorectal cancer risk. Enhanced qualified mucosal observation improves ADR, but manual quantification of qualified mucosal observation time (QMOT) in routine is challenging. We developed an artificial intelligence (AI) system, QAMaster, for automatic QMOT calculation during colonoscopy withdrawal. QAMaster comprises two models: Model I for image quality analysis (trained with 57,235 images from 64 patients) and Model II for anatomical landmark identification (trained with 7712 images from 3013 patients). Patients were stratified by QMOT, and ADR was compared. The areas under the curve (AUC) of Model I were 0.980–0.991, and Model II were 0.977–0.997. Among 482 patients, ADR was 36.54% (57/156) vs. 19.94% (65/326) in high-QMOT group (≥90 s) vs. low-QMOT group (<90 s) (adjusted OR 2.02; 95% CI 1.23–3.33). QAMaster provides a promising tool for assessing colonoscopy withdrawal quality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality globally1. Early detection and removal of precancerous adenomas via colonoscopy are crucial for reducing CRC incidence and mortality2. Despite the proven effectiveness of colonoscopy in CRC prevention, 26% of adenomas and 9% of advanced adenomas are missed during colonoscopy, largely due to the substantial variability in colonoscopy inspection quality3. Missed lesions may promote the development of post-colonoscopy CRC (PCCRC)4. Therefore, various quality indicators for colonoscopy, such as withdrawal time, bowel preparation quality, and cecal intubation rate, have been established to increase the adenoma detection rate (ADR) and reduce the risk of PCCRC5,6,7.

Colonoscopy withdrawal time is defined as the period spent withdrawing the colonoscope while inspecting the colonic mucosa from the cecum to the anus in the absence of an intervention6. Current guidelines recommend a minimum withdrawal time of 6 min to ensure thorough mucosal observation and enhance ADR8,9,10,11. According to recent studies, increasing the withdrawal time to 8–13 min could further improve the ADR, as it allows for a more meticulous examination of the colonic mucosa12,13,14,15,16. However, withdrawal time contains various components, including time spent on non-informative and defective observations, handling of foreign bodies, and qualified mucosal observation17. Enhancing the qualified mucosal observation is more effective in increasing the ADR than simply prolonging the withdrawal time18. Moreover, improving the qualified mucosal exposure can significantly reduce the total inspection time without compromising lesion detection19,20. These findings underscore the importance of focusing on qualified mucosal observation time (QMOT) rather than on the total withdrawal time. However, manual quantification of QMOT during routine practice demands substantial human resources and is prone to interobserver variability.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into medical imaging has shown great promise for enhancing diagnostic accuracy and procedural quality21,22,23. In colonoscopy, AI has primarily focused on real-time polyp or adenoma detection and characterization, demonstrating its potential in standardizing quality of colonoscopy and reducing interobserver variability24,25,26. However, limited researches have investigated the use of AI in the measurement of QMOT and validated this tool as a quality control metric for colonoscopy.

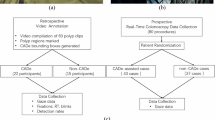

This study aimed to develop and validate the accuracy and effectiveness of an AI system, named the quality assessment master (QAMaster), for the automatic calculation of QMOT during colonoscopy withdrawal by leveraging advanced Vision Transformer (ViT) models (Fig. 1)27. By conducting a comprehensive validation, our study demonstrated that the QAMaster is a potential practical tool for assessing colonoscopy quality.

Data of the colonoscopic withdrawal images were collected and annotated. QAMaster, which consists of two models—Model I for image quality assessment and Model II for anatomical landmark identification—was then trained. Afterward, QAMaster was validated using both internal and external testing datasets. The qualified mucosal observation time (QMOT) was automatically calculated using QAMaster, with a threshold of QMOT ≥ 90 s set as the cut-off, corresponding to an adenoma detection rate (ADR) of 26.05%. Finally, the clinical value of QMOT was assessed using a prospective cohort study.

Results

QAMaster development and evaluation

Four methods, namely ViT, ResNet-50, DenseNet-121, and EfficientNet-b2, were used to develop QAMaster. Compared to convolutional neural network architectures, ViT-based models demonstrated a slight advantage in performance, achieving the highest macro-AUC of 0.980 and micro-AUC of 0.983 in image quality assessment (Supplementary Table 1). For cecum identification, the ViT-based models showed better performance than the others, with the highest AUC of 0.992 and an accuracy of 0.975 (Supplementary Table 2).

The accuracy of Model I in the internal testing dataset (20 patients, 19,467 images) ranged from 0.911 to 0.999 for the six types of images (in vitro, non-informative, foreign body, intervention, defective, and qualified), and the macro-AUC was 0.980 (range, 0.962–0.999). In the external testing dataset (20 patients, 19,328 images), the accuracy ranged from 0.961 to 0.995 and the macro-AUC was 0.990 (range, 0.981–0.996). In the prospective testing dataset (20 patients, 24,568 images), the accuracy ranged from 0.954 to 0.990, and the macro-AUC was 0.991 (range, 0.985–0.999) (Fig. 2a–i and Supplementary Tables 3–5). Representative predicted images are shown in Supplementary Fig. 1a–f, and classification of the images collected from a representative patient into six types is shown in Fig. 2j. In the 10 videos, the proportion of each label identified by Model I was comparable to that of the endoscopist’s annotations (Fig. 2k).

a Accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of Model I on the internal testing dataset. b Confusion matrix of Model I on the internal testing dataset. c AUC performance for classifying multiclass labels of Model I on the internal testing dataset. d Accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of Model I on the external testing dataset. e Confusion matrix of Model I on the external testing dataset. f AUC performance for classifying multiclass labels of Model I on the external testing dataset. g Accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of Model I on the prospective testing dataset. h Confusion matrix of Model I on the prospective testing dataset. i AUC performance for classifying multiclass labels of Model I on the prospective testing dataset. j Distribution of Model I in recognizing each classification in a representative withdrawal video. k Comparison between Model I and expert endoscopists in recognition of each classification in the 10 withdrawal videos. AUC area under the curve.

The accuracy of Model II in identifying the cecum in the internal testing dataset (20 patients, 1751 images) was 0.963, with the AUC 0.997. In the external testing dataset (20 patients, 1657 images), the accuracy was 0.947 and the AUC was 0.996. In the prospective testing dataset (20 patients, 1552 images), accuracy was 0.958 and the AUC was 0.977 (Fig. 3a–i and Supplementary Table 6). Typical visualizations of Model II in recognizing the cecum and other sites are shown in the Supplementary Fig. 2a, b. Identification of the cecum images collected from a representative patient is shown in Fig. 3j. Notably, the withdrawal time predicted by QAMaster was highly correlated with the time determined by the endoscopists (Pearson correlation coefficient 0.991, P < 0.001, Fig. 3k).

a Accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of Model II on the internal testing dataset. b Confusion matrix of Model II on the internal testing dataset. c AUC performance for classifying landmarks of Model II on the internal testing dataset. d Accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of Model II on the external testing dataset. e Confusion matrix of Model II on the external testing dataset. f AUC performance for classifying landmarks of Model II on the external testing dataset. g Accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity of Model II on the prospective testing dataset. h Confusion matrix of Model II on the prospective testing dataset. i AUC performance for classifying landmarks of Model II on the prospective testing dataset. j Distribution of Model II in recognizing each classification in a representative withdrawal video. k Correlation between the predicted withdrawal time of QAMaster and endoscopists in 100 withdrawal videos. AUC area under the curve, PCC Pearson correlation coefficient.

Clinical effectiveness of QMOT in prospective cohort

The prospective cohort included 482 patients who were enrolled in the analysis (Supplementary Fig. 3). The baseline characteristics are shown in the Supplementary Table 7. The mean QMOT was 78.93 s, and the mean withdrawal time was 365.48 s.

To simplify the utilization of QMOT, the actual QMOT calculated by QAMaster was converted into categorical variables at 30-s intervals. A significant positive correlation was observed between QMOT and ADR, with a Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient of 0.999 (Fig. 4a, P < 0.001). ADR was 8.33% in patients with <30-s QMOT (n = 24), 16.25% in patients with 30–60-s QMOT (n = 160), 26.05% in patients with 60–90-s QMOT (n = 142), 32.98% in patients with 90–120-s QMOT (n = 94), 37.84% in patients with 120–150-s QMOT (n = 37), and 48.00% in patients with ≥180-s QMOT (n = 25). To achieve an ADR of at least 25%, QMOT ≥90 s was set as the cut-off (the ADR being 26.05%) (Fig. 4a).

a Correlation between ADR and QMOT classification was conducted using Spearman’s rank correlation. The dotted lines represent an ADR of 25%, and the latest ADR of 26.05% on the curve was used as the optimal time point for QMOT (90 s). b Comparison of ADR between low-QMOT and high-QMOT groups using chi-squared test. c Comparison of ADR across groups with different total withdrawal times (between ≥6 min and <6 min) in high-QMOT group. d Association between risk factors and ADR using a multivariate logistic regression analysis. Data are presented as the ORs, 95% CIs, and P values. ADR adenoma detection rate, SCC Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, QMOT qualified mucosal observation time.

The enrolled patients were divided into two groups, namely low-QMOT with QMOT <90 s and high-QMOT with QMOT ≥90 s. The distribution of baseline information of patients and endoscopists in the low- and high-QMOT groups was collected (Supplementary Table 8). Compared to that in the low-QMOT group, colonoscopies in the high-QMOT group were more often performed in the early session of the half-day (73.08% vs. 60.43%, P = 0.009), by female endoscopists (60.26% vs. 47.24%, P = 0.010) and by physicians with ≥4000 colonoscopy cases (81.41% vs. 71.47%, P = 0.025) (Supplementary Tables 8 and 9). The ADR in the high-QMOT group was significantly higher than that in the low-QMOT group (36.54% vs. 19.94%, P < 0.001; Fig. 4b). Multivariate logistic regression showed that high QMOT was an independent risk factor for adenoma (odds ratio (OR), 2.02; 95% CI, 1.23–3.33) and polyp detection (OR, 2.21; 95% CI, 1.41–3.48, Table 1). Notably, high QMOT was significantly correlated with the detection of diminutive (OR, 3.93; 95% CI, 2.09–7.39) and small adenomas (OR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.02–3.03, Table 1). The association between high QMOT and ADR was consistent across the right, transverse, and left colon (Table 1). Subgroup analyses showed that the ADR in the high-QMOT group was remarkably higher than that in the low-QMOT group across different ages, patient sex, examination time for colonoscopy, endoscopist sex, endoscopist experience, and withdrawal time (Supplementary Tables 10–21 and Supplementary Figs. 4a–f and 5). Notably, the ADR of the high-QMOT group was significantly higher than that of the low-QMOT group in the subgroup of withdrawal time ≥6 min (41.91% vs. 22.09%, P = 0.006, Supplementary Table 21). We further investigated the difference of ADR within subgroups of different total withdrawal time (<6-min and ≥ 6-min groups) in the high-QMOT group. Results showed that the ADR for total withdrawal time ≥ 6 min was higher than that for total withdrawal time <6 min (41.91% vs. 25.49%, P = 0.069) although the difference was not statistically significant (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Table 22). The results suggested that with this threshold, QMOT may be used as an effective quality indicator for colonoscopy.

Risk factors for adenoma detection

Finally, we conducted a logistic regression analysis to determine the variables related to adenoma detection. The results of the univariate logistic regression were as follows: age ≥50 years (OR, 4.36; 95% CI, 2.51–7.59), male patients (OR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.27–2.96), QMOT ≥90 s (OR, 2.31; 95% CI, 1.51–3.53), total withdrawal time ≥6 min (OR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.28–2.93), and endoscopists with experience of ≥4000 cases (OR, 1.88; 95% CI, 1.11–3.17, Supplementary Table 23) were risk factors of adenoma detection. The results of the multivariate logistic regression revealed the following independent risk factors of adenoma detection: age ≥50 years (OR, 4.39; 95% CI, 2.48–7.78), male patients (OR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.29–3.16), and QMOT of ≥90 s (OR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.23–3.33) (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Table 23).

Discussion

In this study, we developed and evaluated the accuracy and effectiveness of the QAMaster for colonoscopic examinations. QAMaster leveraged the ViT models to provide real-time image quality assessment and landmark identification, thereby automatically calculating QMOT. ADR in the high-QMOT group was significantly higher than that in the low-QMOT group. Multivariate logistic regression analysis indicated that QMOT was a potentially more effective quality control indicator than the total withdrawal time.

Quality control during colonoscopy plays a crucial role in increasing the incidence of ADR while reducing that of PCCRC5,6. Researches indicate that a more prolonged colonoscopy withdrawal time (8–13 min) allows for a higher ADR12,13,14,15,16. However, even during a colonoscopy with more prolonged withdrawal time, enough QMOT may not be possible19,20. Calculating QMOT typically requires significant human resources, is challenging to implement broadly12,28, and can introduce high variability and inconsistencies. Our QAMaster based on AI algorithms automated the calculation of QMOT, and demonstrated that the system performs accurately and consistently across multiple still images and video datasets, allowing for a mucosal observation of high quality during withdrawal.

Previous studies have used AI algorithms to record QMOT. For instance, Lux et al. developed an AI model to automatically calculate QMOT, and found the AI-predicted time to have smaller absolute differences with the measured time than the human-reported time29. Similarly, Lui et al. developed an AI model to record QMOT by excluding the time of inadequate view (including water absorption, significant redness, incomplete inflation, light reflection, excrement blocking, and air bubble blocking), identifying four quintiles of QMOT, and demonstrating a positive correlation between adenoma detection and higher quintiles30. Compared to previous studies, our image quality assessment model classified images in more detail, ensuring homogeneity across different categories, and enhancing the model’s effectiveness. We applied six distinct labels in this study, including in vitro, non-informative, foreign body, intervention, defective, and qualified with predefined visual criteria. Although all the images were annotated through majority agreement by three experienced endoscopists, the distinction between labels may vary slightly depending on human interpretation, which can influence the final QMOT measurement. In future work, we will further refine and standardize annotation protocols, possibly incorporating semi-automated labeling tools and multi-institutional validation to improve reproducibility and generalizability. Despite this subjectivity, QAMaster demonstrated consistently high performance across both internal and external validation datasets, suggesting that the current annotation framework is sufficiently robust for a generalizable and effective QMOT assessment system.

Moreover, none of the previous studies identified a suitable QMOT or investigated its clinical significance in real-world clinical settings. Our study addressed this gap by identifying a reasonable QMOT that provides a significant improvement over those from previous methods. We found that QMOT ≥90 s was positively correlated with adenoma detection (OR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.23–3.33) through multivariate logistic regression. Subgroup analyses demonstrated the stability of the association between QMOT ≥90 s and ADR across different ages, patient sexes, examination time for colonoscopy, endoscopist sexes, endoscopists’ experience, and withdrawal time. There were several advantages of our established QMOT. On one hand, the ADR of high QMOT was significantly higher than that of low QMOT, and QMOT ≥90 s was an independent risk factor for ADR. When total withdrawal time, colonoscopy experience, and QMOT were included in the regression model, only QMOT ≥90 s remained significantly positively associated with ADR, despite being positively correlated with ADR in univariate analyses. This suggested that the QWT could be more important for quality control during colonoscopy. On the other hand, in the group with withdrawal time ≥6 min, the ADR was significantly higher in the high-QMOT subgroup than in the low-QMOT subgroup. This further highlighted the importance of QMOT over total withdrawal time in improving ADR. Our current definition of QMOT is intentionally strict, as it was designed to capture only frames with stable, clear, and informative mucosal visualization while excluding frames affected by camera movement, non-informative content, foreign bodies, or transitional views. This conservative approach ensures high quality of frames and consistency but may lead to relatively low QMOT values, as observed in our results. In future work, we will explore more flexible and dynamic criteria, such as those can tolerate slight movements or incorporate a continuous quality score, to better align the QMOT metric with practical endoscopic performance while maintaining its objectivity and reliability. Due to the strict definition of QMOT, endoscopists are required to maintain a relatively stable withdrawal or adopt a “withdrawal–stop to inspect–withdrawal” approach during the procedure to enable real-time application of QAMaster.

The AI architecture employed in QAMaster offered various advantages over traditional methods. In particular, the ViT models utilized in our system excelled at processing complex visual data, enabling precise real-time assessment of image quality and landmark identification. The models significantly enhanced the accuracy and robustness of the system, ensuring reliable performance across diverse clinical settings compared to several deep convolutional neural networks. The heat maps generated by QAMaster suggested that its remarkable performance can be attributed to the ability of ViT models to capture global information across the entire image27. This integration of AI into colonoscopy represented a notable advancement, promoting a higher ADR and more comprehensive mucosal inspections, ultimately improving CRC screening and prevention.

Our study had certain limitations. One limitation of our current approach is that the exclusion of frames containing foreign bodies or defects may lead to underestimation of potentially informative images, as such frames can still contribute to lesion detection in real-world clinical practice. In future work, we plan to quantify the proportion of the visual field obscured by foreign matter or defects and explore threshold values that do not compromise diagnostic accuracy. Moreover, our current model does not distinguish between standard-view and magnified-view modes, which may affect the granularity of time measurement for lesion search versus detailed inspection. We will incorporate view mode differentiation in subsequent model iterations like previously reported view mode to further refine the assessment of effective mucosal observation time30. Another limitation was that the system’s performance was based on data from Olympus endoscopes. Considering the widespread market share of Olympus endoscopes and the homogeneity of endoscopic images, QAMaster may be adapted to other endoscopes through transfer learning, thus ensuring broader applicability. Furthermore, while QAMaster has demonstrated potential in improving ADR, its effect on the detection of high-risk precancerous lesions and long-term clinical outcomes remains to be validated with regard to cost-effectiveness31. We plan to conduct randomized controlled trials to comprehensively assess its impact on high-risk lesion detection and to further establish its clinical value in enhancing the quality and effectiveness of colonoscopy.

In conclusion, we proposed the QAMaster system, which would offer a more precise and effective method for colonoscopy quality control through automatic calculation of QMOT. The system addressed the limitations of total withdrawal time metrics and could provide a robust tool for enhancing the effectiveness of colonoscopic examinations. Future research should focus on broadening the validation of QAMaster across diverse clinical settings and exploring its long-term impact on patient outcomes.

Methods

Study design and datasets

A stepwise AI validation study was conducted in two hospitals, namely Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital (NJDTH) and Nanjing Gaochun People’s Hospital (GCPH) in China. QAMaster consisted of two models, namely Model I for image quality assessment and Model II for anatomical landmark identification. First, we retrospectively collected 93,726 images from NJDTH, which were randomly divided into a training dataset with 57,235 images (61.07%) from 64 patients, a validation dataset with 17,024 images (18.16%) from 16 patients, and an internal testing dataset with 19,467 images (20.77%) from 20 patients to develop and validate Model I. Similarly, 11,167 images from NJDTH were randomly split into a training dataset with 7712 images (69.06%) from 3013 patients, a validation dataset with 1704 images (15.26%) from 755 patients, and an internal testing dataset with 1751 images (15.68%) from 20 patients to develop and validate Model II. The inclusion criteria for the retrospective datasets were as follows: (1) colonoscopy examinations conducted at one of the two institutions between January 2021 and June 2021; (2) availability of clinical information, images, and videos at the time of diagnosis; and (3) all endoscopic procedures performed with the Olympus 290 series system (Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan). The exclusion criteria were: (1) inflammatory bowel disease, (2) familial polyposis syndrome, and (3) history of colorectal surgery.

Subsequently, we collected three independent datasets for further validation of Model I (retrospective external testing dataset 1:19,328 images of 20 patients from GCPH; prospective testing dataset 1:24,568 images of 20 patients from NJDTH; and video testing dataset 1:10 videos of 10 patients from NJDTH) and Model II (retrospective external testing dataset 2:1657 images of 20 patients from GCPH; prospective testing dataset 2:1552 images of 20 patients from NJDTH; and video testing dataset 2:100 videos of 100 patients from NJDTH) (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 24). The training, validation, and testing datasets were divided at the patient level to ensure the independence of the datasets. Finally, a prospective observational study was conducted to evaluate the clinical significance of QMOT in real-world clinical scenarios.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital (no. 2023-175-02). Written informed consent was obtained from all the prospectively recruited patients. For retrospectively collected data, the ethics committee waived the requirement for informed consent since only de-identified information was used. All procedures adhered to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Training and testing datasets

To generate the training and testing datasets, both still images and videos from the enrolled patients were utilized. All videos, except those designated for video testing, were firstly converted into frames, followed by cropping the irrelevant borders to retain the internal view of the colon. Then, OpenCV’s Perceptual Hash (pHash) algorithm was employed to identify and eliminate duplicate images, thereby reducing redundancy.

For the training and testing of Model I, the following datasets were used (Supplementary Fig. 6):

-

(1)

Training dataset: 3926 in vitro images, 20,439 non-informative images, 11,207 foreign body images, 3396 intervention images, 13,644 defective images, and 4623 qualified images from 64 patients at Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital (NJDTH).

-

(2)

Validation dataset: 731 in vitro images, 6595 non-informative images, 2846 foreign body images, 1366 intervention images, 4186 defective images, and 1300 qualified images from 16 patients at NJDTH.

-

(3)

Internal testing dataset: 1191 in vitro images, 7000 non-informative images, 4144 foreign body images, 1257 intervention images, 4511 defective images, and 1364 qualified images from 20 patients at NJDTH.

-

(4)

External testing dataset: 688 in vitro images, 5736 non-informative images, 3931 foreign body images, 1735 intervention images, 4451 defective images, and 2788 qualified images from 20 patients at Gaochun People’s Hospital (GCPH).

-

(5)

Prospective testing dataset: 4451 in vitro images, 7803 non-informative images, 4444 foreign body images, 848 intervention images, 4001 defective images, and 2921 qualified images from 20 patients at NJDTH.

-

(6)

Video testing dataset: 10 videos from 10 patients, randomly selected from the prospective testing dataset at NJDTH, were used to evaluate the consistency between Model I and endoscopists in the real-time recognition of each label.

For the training and testing of Model II, the following datasets were used:

-

(1)

The training dataset: 4668 cecum images and 4748 other sites images of 3768 patients at NJDTH.

-

(2)

The internal testing dataset: 763 cecum images and 988 other sites images of 20 patients at NJDTH.

-

(3)

The external testing dataset: 644 cecum images and 1013 other sites images of 20 patients at GCPH.

-

(4)

The prospective testing dataset: 599 cecum images and 953 other sites images of 20 patients at NJDTH.

-

(5)

The video testing dataset: 100 videos from 100 patients, randomly selected from the dataset established in the prospective observational study, were used to evaluate the correlation between the predicted withdrawal time by QAMaster and that determined by endoscopists.

The training and testing datasets were divided at patient level to ensure the independence of the training and testing datasets.

Model design and training

QAMaster is consisted of two deep learning models, and both models were based on ViT27. QAMaster initiates its preprocessing by first resizing the images, followed by normalization. An RGB image is cropped and split into a batch of 16*16 nonoverlapping patches before being fed into the ViTs architecture. To retain the maximum amount of visual information, all colonoscopy images were preserved in their original three-channel RGB format throughout the entire preprocessing and training pipeline. No conversion to grayscale or other color spaces was performed. This decision was motivated by the fact that color cues can be clinically relevant in endoscopic imaging and may contribute to improved feature extraction by the neural network, particularly in differentiating mucosal texture, vascular patterns, and artifacts. Once normalized, the images are partitioned into distinct, non-overlapping windows. Subsequently, the content of these windows is converted into token embeddings. To enhance their spatial context, these embeddings are complemented with positional embeddings32. We employed standard learnable 1D positional embeddings, consistent with the original ViT design. In particular, each patch embedding was augmented with a positional embedding of the same dimensionality as that of patch embedding before being fed into the Transformer encoder. These positional embeddings were initialized as trainable parameters and added element-wisely to the sequence of patch embeddings. This design allows the model to capture spatial information across image patches, which is critical for accurate visual representation and downstream classification. This refined data then proceeds to the deeper layers of the model, enabling sophisticated visual analysis. All our model parameters have been pretrained on ImageNet before being fine-tuned on our collected dataset. Finally, to enhance the model’s robustness, we utilized mixup augmentation during the training process33. To improve the efficiency of training process, an increasing number of training images were used to obtain an optimal sample size of training datasets. An early stopping strategy was used to prevent overfitting. In particular, after each epoch, the model’s performance on the validation set was evaluated. If no improvement in validation accuracy was observed for five consecutive epochs, training was terminated. The model weights from the epoch with the highest validation accuracy were retained for final evaluation on the test set. This strategy ensured robust generalization while avoiding unnecessary over-training. The stability of the models was evaluated with 5-fold cross-validation and using different random seeds. The specific training details are shown in Supplementary Note 1, Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8, and Supplementary Tables 25–28. Our models were both trained and evaluated using four GeForce RTX 2080TI graphics processing units (NVIDIA Corporation, Santa Clara, California, USA). The optimal hyperparameters were selected using validation datasets.

Evaluation of QAMaster performance

The performance of Model I was assessed on the internal, external, and prospective testing datasets. For each classification on the datasets, multi-label classification was evaluated with confusion matrix, accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, and F1-score at binary decision thresholds. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis with area under the curve (AUC) calculation was performed. macro-AUC, and micro-AUC were used to assess the aggregate performance of multi-label classification. Five-fold cross validation and different random seeds were also used to evaluate the performance of Model I. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and precision were computed with Clopper–Pearson method, and the 95% CIs of AUC and F1-score were calculated using bootstrapping with 1000 resamples.

The Model II was tested on the internal, external, and prospective testing datasets. The performance of Model II was evaluated with confusion matrix, AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, precision, and F1-score with 95% CIs.

The metrics were calculating using the following formulas:

Procedures

To establish Model I for image quality assessment, colonoscopy images were annotated with the following six labels: (1) in vitro: images captured outside of the body; (2) non-informative: images captured too close to the colon wall, those out of focus, containing numerous artifacts, or with over- or under-exposure; (3) foreign body: images containing bubbles, fluid, and fecal materials; (4) intervention: images showing flushing, chromoendoscopy, biopsy, or any other instruments; (5) defective: images with a small number of artifacts, slightly blurry areas, or mild overexposure but still showing part of the mucosa; (6) qualified: images with clearly visible mucosa or vessels, moderate lighting, and no artifact17. For Model II (for anatomical landmark identification), images were annotated as showing either the cecum (ileocecal valve, appendiceal orifice, and cecal caput) or other sites6. All images were annotated by three experienced endoscopists with >10 years of experience in colonoscopy, and only the images for which at least two endoscopists reached a consensus were included.

To test QAMaster, images from the internal, external, and prospective testing datasets were first adopted to evaluate the classification performance of Models I and II. Subsequently, videos from video-testing dataset 1 were used to analyze the accuracy of Model I in calculating the duration of different labels in real-time. Videos from video-testing dataset 2 were used to assess the performance of QAMaster in calculating the withdrawal time (Supplementary Movies 1 and 2).

QMOT was calculated using QAMaster, as follows: Model II identified the cecum frame for the first time to determine the start time of colonoscopy withdrawal, and Model I recognized the in-vitro frames to determine the end time of the withdrawal. The total number of withdrawal and qualified frames in the withdrawal procedure were calculated using Model I.

\({\rm{The\; total\; withdrawal\; time}}={\rm{the\; end\; time\; of\; withdrawal}}-{\rm{the\; start\; time\; of\; withdrawal}}-{\rm{time\; of\; the\; intervention}}\) (6)

To facilitate the utilization of the qualified withdrawal time, every 30 s of QMOT was treated as a class (i.e., 0–30 s corresponded to a QMOT category of 30 s, 30–60 s corresponded to a QMOT category of 60 s, etc.).

To evaluate the clinical value of QMOT, we conducted a single-center prospective cohort study in NJDTH. We recruited consecutive patients aged between 18 and 75 years who provided informed consent to undergo colonoscopy between July 1 and October 15, 2023. The exclusion criteria were inflammatory bowel disease, family polyposis syndrome, history of colorectal surgery, known or suspected bowel obstruction or perforation, and pregnancy or lactation.

Data collection

Basic demographic characteristics of patients including age, sex, indication for colonoscopy, type of sedation, recruitment of patients, and time for colonoscopy were recorded before colonoscopy. Time for colonoscopy was divided into 2 groups according to the end time of procedure. The early group commenced in the early session per half day (8:00 AM to 10:59 AM or 1:00 PM to 3:29 PM), and the late group commenced in the late session per half day (11:00 AM to 12:59 PM or 3:30 PM to 5:29 PM). Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS) score was used to assess bowel preparation34. Information regarding endoscopist age, sex, year of practice, endoscopists experience, and colonoscopies per year were also obtained. The withdrawal time was defined as time from cecum to anus, exclusion the time of intervention including polyp resection, biopsy time, time of the mucosal cleaning, and observation time using chromoendoscopy, which was automatically computed by the QAMaster. After the colonoscopy, whole colonoscopy videos were collected for subsequent analysis. Two endoscopists rechecked the cecal intubation time and withdrawal time reported by the QAMaster.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes for the performance of QAMaster were AUC, accuracy, sensitivity, and specificity. For the prospective observational study, primary outcome was the ADR, defined as the proportion of patients with one or more histologically confirmed adenomas. Secondary outcomes included the ADR for adenomas of different sizes (diminutive ≤5 mm, small >5 to <10 mm, or large ≥10 mm) and locations (the right colon defined as the cecum to the ascending colon, the transverse colon as the hepatic flexure to the splenic flexure, and the left colon as the descending colon to the rectum), the polyp detection rate for polyps of different sizes and locations, advanced ADR, and sessile serrated lesion detection rate of patients above and below the determined QMOT threshold. Advanced adenomas were defined as those with a size of 10 mm, a villous component, or high-grade dysplasia. Polyps were diagnosed based on endoscopic diagnosis, and adenomas and sessile serrated lesions were diagnosed based on the World Health Organization criteria and the pathology reports from NJDTH.

Statistical analysis

We analyzed 250 patients recruited earlier (in the prospective study) to estimate the sample size. A sample size of 466 was required to meet a two-sided 95% CI with a width of 0.1 when the Spearman’s rank correlation of the 250 patients was 0.715 (PASS, version 15.0.5). Considering that approximately 5% of the patients may be excluded from the analysis, the target sample size was set to 492 cases. Variants were compared using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Student’s t test for continuous variables. We calculated the ADR of each QMOT class and performed correlation analysis using Spearman analysis. Logistic regression was used to evaluate the association between adenoma detection and QWT above and below the determined threshold, after adjusting for age, sex, indication for colonoscopy, use of analgesia, examination time for colonoscopy, bowel preparation, type of instrument, withdrawal time, age and sex of endoscopists, years of practice, experience as endoscopist, and colonoscopies per year. All statistical tests were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using the R software (version 4.3.3).

Data availability

Due to the requirements of Ethics Committee, all the deidentified data sets generated or analyzed in the present study are available from the corresponding author (Lei Wang, leiwang9631@nju.edu.cn) upon reasonable request with written data-sharing agreement signed.

Code availability

All the computations of this study (after data preprocessing) were performed in Python, and the corresponding codes are publicly available at https://cs.nju.edu.cn/lwj/code/QAMaster.zip.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 74, 229–263 (2024).

Kaminski, M. F. et al. Increased rate of adenoma detection associates with reduced risk of colorectal cancer and death. Gastroenterology 153, 98–105 (2017).

Zhao, S. et al. Magnitude, risk factors, and factors associated with adenoma miss rate of tandem colonoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology 156, 1661.e1–1674.e1 (2019).

Robertson, D. J. et al. Colorectal cancers soon after colonoscopy: a pooled multicohort analysis. Gut 63, 949–956 (2014).

Pilonis, N. D. et al. Long-term colorectal cancer incidence and mortality after a single negative screening colonoscopy. Ann. Intern. Med. 173, 81–91 (2020).

May, F. P. & Shaukat, A. State of the science on quality indicators for colonoscopy and how to achieve them. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 115, 1183–1190 (2020).

Rex, D. K. et al. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 119, 1754–1780 (2024).

Rees, C. J. et al. UK key performance indicators and quality assurance standards for colonoscopy. Gut 65, 1923–1929 (2016).

Saito, Y. et al. Colonoscopy screening and surveillance guidelines. Dig. Endosc. 33, 486–519 (2021).

Kaminski, M. F. et al. Performance measures for lower gastrointestinal endoscopy: a European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) quality improvement initiative. Endoscopy 49, 378–397 (2017).

Shaukat, A. et al. ACG clinical guidelines: colorectal cancer screening 2021. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 116, 458–479 (2021).

Vavricka, S. R. et al. Monitoring colonoscopy withdrawal time significantly improves the adenoma detection rate and the performance of endoscopists. Endoscopy 48, 256–262 (2016).

Shaukat, A., Holub, J., Greenwald, D., Eisen, G. & Schmitt, C. Variation over time and factors associated with detection rates of sessile serrated lesion across the United States: results form a national sample using the GIQuIC registry. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 116, 95–99 (2021).

Desai, M. et al. Impact of withdrawal time on adenoma detection rate: results from a prospective multicenter trial. Gastrointest. Endosc. 97, 537.e2–543.e2 (2023).

Zhao, S. et al. Impact of 9-minute withdrawal time on the adenoma detection rate: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 20, e168–e181 (2022).

Zhao, S. et al. Reduced adenoma miss rate with 9-minute vs 6-minute withdrawal times for screening colonoscopy: a multicenter randomized tandem trial. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 118, 802–811 (2023).

Yao, H., Stidham, R. W., Soroushmehr, R., Gryak, J. & Najarian, K. Automated detection of non-informative frames for colonoscopy through a combination of deep learning and feature extraction. In 2019 41st Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC) 2402–2406 (IEEE, 2019).

Vilmann, A. S. et al. Colonoscope retraction technique and predicting adenoma detection rate: a multicenter study. Gastrointesti. Endosc. 95, 1002–1010 (2022).

Bhattacharyya, R. et al. Endocuff-assisted vs. standard colonoscopy in the fecal occult blood test-based UK Bowel Cancer Screening Programme (E-cap study): a randomized trial. Endoscopy 49, 1043–1050 (2017).

Rex, D. K. et al. Endocuff Vision reduces inspection time without decreasing lesion detection: a clinical randomized trial. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 18, 158.e1–162.e1 (2020).

Repici, A. et al. Efficacy of real-time computer-aided detection of colorectal neoplasia in a randomized trial. Gastroenterology 159, 512–520.e517 (2020).

Gong, D. et al. Detection of colorectal adenomas with a real-time computer-aided system (ENDOANGEL): a randomised controlled study. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 5, 352–361 (2020).

Repici, A. et al. Artificial intelligence and colonoscopy experience: lessons from two randomised trials. Gut 71, 757–765 (2022).

Wang, P. et al. Development and validation of a deep-learning algorithm for the detection of polyps during colonoscopy. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2, 741–748 (2018).

Hassan, C. et al. Real-time computer-aided detection of colorectal neoplasia during colonoscopy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 176, 1209–1220 (2023).

Shaukat, A. et al. Computer-aided detection improves adenomas per colonoscopy for screening and surveillance colonoscopy: a randomized trial. Gastroenterology 163, 732–741 (2022).

Dosovitskiy, A. et al. An image is worth 16x16 words: transformers for image recognition at scale. In International Conference on Learning Representations (OpenReview.net, 2020).

Ishibashi, F. et al. Individual feedback and monitoring of endoscopist performance improves the adenoma detection rate in screening colonoscopy: a prospective case–control study. Surg. Endosc. 35, 2566–2575 (2021).

Lux, T. J. et al. Assisted documentation as a new focus for artificial intelligence in endoscopy: the precedent of reliable withdrawal time and image reporting. Endoscopy 55, 1118–1123 (2023).

Lui, T. K., Ko, M. K., Liu, J. J., Xiao, X. & Leung, W. K. Artificial intelligence–assisted real-time monitoring of effective withdrawal time during colonoscopy: a novel quality marker of colonoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 99, 419.e6–427.e6 (2024).

Mori, Y. et al. Artificial intelligence in gastrointestinal endoscopy: The Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society Position Statements. Dig. Endosc. https://doi.org/10.1111/den.15075 (2025).

Liu, Z. et al. Swin transformer: hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision 10012–10022 (2021).

Zhang, H., Cisse, M., Dauphin, Y. N. & Lopez-Paz, D. mixup: Beyond empirical risk minimization. In International Conference on Learning Representations (OpenReview.net, 2018).

Lai, E. J., Calderwood, A. H., Doros, G., Fix, O. K. & Jacobson, B. C. The Boston Bowel Preparation Scale: a valid and reliable instrument for colonoscopy-oriented research. Gastrointest. Endosc. 69, 620–625 (2009).

Acknowledgements

This project is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 62306136 and 62006113), Jiangsu Provincial Key Research and Development Program (grant nos. BE2023655 and BE2021601), Key Project of Medical Science and Technology Development of Nanjing Municipal Health Commission (grant no. ZKX21032), and fundings for Clinical Trials from the Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University (grant no. 2021-LCYJ-MS-06). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, data analyses, interpretation, or writing of the report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.W., W.-J.L., D.T., and X.Z. conceived the study design. W.-J.L. and J.-D.Z. designed the models and trained the models in their use. P.Y., M.N., L.Z., X.Z., Z.Z., N.G., Z.W.J., D.Z., C.P., H.Z., M.C., G.X., and D.T. acquired the data. D.T., P.Y., W.-J.L., and J.-D.Z. analyzed and interpreted the data. D.T., P.Y., and J.-D.Z. drafted the paper and the figures. L.W., W.-J.L., and D.T. substantially reviewed the paper and modified the paper. All authors had full access to the data, and L.W., W.-J.L., D.T., and X.Z. directly accessed and verified the data in the study. All authors accept the final responsibility to submit for publication and take responsibility for the contents of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, WJ., Yan, P., Ni, M. et al. An artificial intelligence system for qualified mucosal observation time during colonoscopic withdrawal. npj Digit. Med. 8, 685 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02067-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02067-2