Abstract

Real-time prediction of short-term mortality risk in the intensive care unit (ICU) is often hampered by missing medical data. To address this, we developed RealMIP, an end-to-end framework leveraging generative model for the dynamic imputation of missing values and continuous mortality risk assessment. The model was trained on data from 188 centers in the eICU Collaborative Research Database (eICU-CRD), and internally validated on 20 held-out centers. External validation was performed using the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV) and Salzburg Intensive Care Database (SICdb). RealMIP’s predictive performance was compared with nine established approaches. RealMIP achieved robust predictive performance, with AUCs of 0.957 (95% CI, 0.956–0.957) internally, 0.968 (95% CI, 0.968–0.968) in MIMIC-IV, and 0.932 (95% CI, 0.932–0.933) in SICdb, outperforming comparator models (p < 0.05). RealMIP unlocks the potential of real-time ICU mortality prediction by effectively handling missing data and delivering continuous, interpretable risk assessments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Accurate prediction of mortality risk in the intensive care unit (ICU) is vital for informed clinical decision-making and effective resource allocation1,2,3,4. Traditional illness severity scores and prediction models primarily rely on static data collected within the first 24 h of admission, failing to capture the dynamic physiological changes that critically ill patients experience5,6,7. Recent advances in real-time clinical decision support systems in ICUs offer the promise of more timely and precise risk assessment, enabling prompt interventions and better-informed decisions, such as those required in organ transplantation8,9,10,11.

However, the effectiveness of real-time prediction models depends on the immediate availability of a comprehensive set of patient variables. In practice, it is rarely feasible to obtain all relevant data points at every moment due to factors such as laboratory processing delays, infrequent examinations, and clinical workflow constraints9,12,13. Consequently, only a subset of variables is typically available at any given time, resulting in pervasive missing data and presenting a significant challenge for real-time prognostic modeling.

To address missingness and irregular measurement times, many existing models aggregate physiological variables into hourly means or variances8,13,14. While this approach simplifies the data and mitigates some missingness, it sacrifices true temporal resolution, limiting the model’s ability to detect rapid physiological changes. Alternatively, conventional imputation techniques, such as forward filling, are commonly used to address missing values9,11,12,13,15,16. However, these methods often ignore the complex temporal and inter-variable dependencies characteristic of ICU data, thereby compromising prediction accuracy.

To overcome these challenges, we propose a novel end-to-end framework that enables timely and accurate mortality risk prediction whenever at least one new clinical examination is conducted. At each such time point, our method utilizes all available historical patient data and employs a generative model to automatically impute missing values, considering both temporal trends and the relationships among clinical variables. This integrated approach allows for real-time risk assessment, ensuring that predictions are always based on the most comprehensive and up-to-date information for each patient, even when the medical examination information is irregular and incomplete in the ICU.

Results

Study cohorts

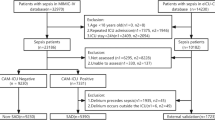

A total of 154,882 admissions (12,594,515 samples) from 188 centers from the eICU Collaborative Research Database (eICU-CRD v2.0)17 were used for model training, while 11,576 admissions (1,006,745 samples) from 20 other centers from the eICU-CRD, 69,111 admissions (8,725,961 samples) from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care Database (MIMIC-IV v2.2)18 and 27,137 admissions (2,478,003 samples) from the Salzburg Intensive Care Database (SICdb v1.0.8)19 served as internal test cohort, independent external validation cohort 1 and independent external validation cohort 2, respectively. During their stay in the ICU, 3645 admissions (2.4%) from the training cohort, 271 admissions (2.4%) from the internal test dataset, 4238 admissions (6.5%) from the MIMIC-IV, and 976 admissions (3.7%) from the SICdb died. Baseline characteristics and mean and standard deviation of input variables are shown in Table 1, according to the cohort and event group. A detailed inclusion and exclusion flow is shown in Fig. 1. The study design, encompassing data collection, preprocessing, model development, validation, and explanation, is illustrated in Fig. 2.

a Data extraction and pre-processing steps performed in this study. b The proposed end-to-end model automatically performs real-time imputation of missing values and predicts patient mortality risk each time a new measurement is obtained. c Compared with traditional imputation methods, our approach more effectively captures temporal dependencies and interactions among features. d The modelling performance was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), calibration curve, decision curve analysis (DCA), and temporal alert efficiency curve. e The SHapley Additive exPlanations algorithm was used to interpret the real-time individualized prediction results after missing values were imputed, and the SHAP risk scores were visualized. eICU-CRD eICU Collaborative Research Database, MIMIC Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care, SICdb Salzburg Intensive Care Database, AUC area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, DCA decision curve analysis, HR heart rate, RR respiratory rat, SBP systolic blood pressure, ALT alanine aminotransferase, WBC white blood cell. Some elements in the figure were drawn by Figdraw.

Predictive performance

RealMIP significantly outperformed all nine comparator models across both internal and external test cohorts (p < 0.05). Specifically, the model achieved an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.957 (95% CI, 0.956–0.957) in the internal test dataset, 0.968 (95% CI, 0.968–0.968) in the MIMIC-IV, and 0.932 (95% CI, 0.932–0.933) in the SICdb, as illustrated in Fig. 3a–c. Additional evaluation metrics, including balanced accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and F1 score, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and false alarm count per 100 patient-days (FAC/100 pt-days), expected calibration errors (ECE), and Brier score, are detailed in Table S1 and S2. The calibration curves demonstrated excellent concordance between predicted and observed probabilities, with the RealMIP model’s curves closely aligning with the 45° line and exhibiting the lowest ECE (Fig. 3d–f). Furthermore, DCA indicated that RealMIP offers clinical benefits across both internal and external test cohorts (Fig. 3g–i). To further validate the effectiveness of our end-to-end training strategy, we conducted ablation experiments. As shown in Table S3, removing the joint optimization of imputation and prediction components led to a noticeable decline in model performance. This highlights the importance of the integrated, end-to-end approach in enabling the RealMIP model to fully leverage imputed data for accurate and robust real-time mortality prediction. To assess robustness against varying degrees of missing data, we calculated the missingness proportion at the patient level, defined as the fraction of missing feature values across the entire time series for each patient. Patients were then ranked by their missingness proportion and split at the median into two groups (high vs. low missingness, equal sample sizes). Model performance (AUC) was compared across these two strata. As shown in Table S4, RealMIP retained strong predictive performance in both groups, suggesting robustness across different levels of data incompleteness.

a–c Display the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) for the internal test cohort (eICU-CRD), and for the external test cohorts (MIMIC and SICdb), respectively. d–f Present the calibration curves for the same cohorts. Panels (g–i) show the decision curve analysis (DCA) results for the internal and two external cohorts, respectively. eICU-CRD eICU Collaborative Research Database, MIMIC Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care, SICdb Salzburg Intensive Care Database, AUC area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, DCA decision curve analysis, NEWS National Early Warning Score, MEWS Modified Early Warning Score, SOFA sequential organ failure assessment, APACHE acute physiology and chronic health evaluation.

We also assessed the temporal changes in RealMIP’s predictive power relative to the time after ICU admission and before death. This dual perspective provides a comprehensive temporal view of RealMIP’s predictive capability, demonstrating both early detection potential and deterioration sensitivity (Fig. 4).

a Performance trajectories aligned forward from ICU admission. b Backcasting analysis of performance trajectories aligned backward from the time of death. eICU-CRD eICU Collaborative Research Database, MIMIC Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care, SICdb Salzburg Intensive Care Database, AUC area under the receiver operating characteristic curve.

Temporal analysis of actionable lead time and false alarm count

We assessed the clinical applicability of RealMIP through a temporal analysis of both actionable lead time and FAC/100 pt-days (Fig. 5). Specifically, we analyzed the proportion of high-risk patients correctly identified at different intervals prior to death. A patient was considered identified if their predicted probability of death exceeded a predefined threshold at least once before a given time point. In addition, we evaluated the temporal trend of the FAC/100 pt-days, offering complementary insights into model performance.

a Proportion of deaths detected as a function of time before death, where detection is defined as at least one prediction exceeding the predefined threshold within the corresponding time window. b False alarm count per 100 patient-days as a function of time before death. eICU-CRD eICU Collaborative Research Database, MIMIC Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care, SICdb Salzburg Intensive Care Database.

Augmenting clinical scoring systems with RealMIP imputation

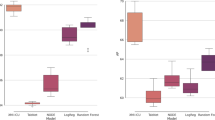

We further explored whether the predictive performance of commonly used real-time clinical scoring systems could be improved by imputing missing data using RealMIP (Fig. 6). The results indicate that data imputed with RealMIP significantly improve the predictive capability of the NEWS and MEWS compared to forward imputation (p < 0.05). In the test set, the AUC for NEWS with forward imputation ranged from 0.742 to 0.808, whereas RealMIP improved it to a range of 0.767 to 0.845. Similarly, the AUC for MEWS with forward imputation was between 0.728 and 0.811, while RealMIP imputation increased this range from 0.755 to 0.838.

In both the internal (eICU-CRD) and external (MIMIC and SICdb) test cohorts, the AUCs of NEWS (a) and MEWS (b) are significantly higher when missing values are imputed with RealMIP compared to forward imputation. Statistical comparisons were performed using DeLong’s test. eICU-CRD eICU Collaborative Research Database, MIMIC Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care, SICdb Salzburg Intensive Care Database, AUC area under the receiver operating characteristic curve, NEWS National Early Warning Score, MEWS Modified Early Warning Score.

Feature importance

The relative importance of the top 20 features contributing to the RealMIP model, as determined by the SHAP algorithm, is presented in Fig.7. Fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2), the Glasgow comma scale (GCS), systolic blood pressure (SBP), age, and saturation of peripheral oxygen (SpO2) play significant roles in the model’s predictive performance. Figure8 provides an analysis of feature importance over time, illustrating the top 10 features based on the absolute sum of the Shapley values. Notably, FiO2 and the GCS-verbal score had substantial impacts on prediction as patients approached death. In contrast, in the survival group, most features contributed to decreasing prediction scores over time, with FiO2 and SBP being particularly influential.

a Top 20 most important features in the internal test set (eICU-CRD), b Top 20 most important features in the external test set (MIMIC), and (c) Top 20 most important features in the external test set (SICdb). eICU-CRD eICU Collaborative Research Database, MIMIC Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care, SICdb Salzburg Intensive Care Database.

Initially, Shapley values were averaged hourly for each admission, and subsequently, these values were averaged across all admissions. The black line indicates the average prediction score. The average Shapley values are added to this prediction score for clarity. a Illustrates data from event admissions, for which we collected values 24 h prior to the time of death. b Depicts data from normal admissions, where we gathered values 24 h before randomly selected time points to mitigate selection bias.

Dynamic imputation and interpretable risk assessment at the individual level

RealMIP enables both the dynamic imputation of missing values and real-time, visual, interpretable risk assessment for individual patients. Figure 9 illustrates a representative case from the external test cohort (MIMIC). The patient, an 89-year-old male, died 48.6 h after ICU admission. We analyzed the temporal dynamics of the ten most important features and their influence on high-risk predictions during the 24 h preceding death. Data were recorded at 45 time points within this period, with solid symbols denoting new measurements and hollow symbols indicating imputed values. RealMIP not only provides real-time mortality risk predictions but also imputes missing values to visualize each feature’s temporal changes and their impact on prediction outcomes. Figure 9b highlights the influence of specific features at a given time point, with lower GCS scores, reduced oxygen saturation, and older age being associated with increased mortality risk, whereas normal heart rate and sodium levels correlated with reduced risk.

a Visualization of the 10 most important features for predicting patient mortality risk at each time point where at least one feature has a new measurement. Solid symbols represent new measurements, while hollow symbols indicate missing values imputed by the RealMIP. The red triangle marks the model’s predicted probability of mortality. The left axis shows the Z-score of each feature, and the right axis displays the predicted mortality probability. b Contribution of each feature to the risk prediction within a specific time point. Features in red increase the predicted risk of mortality (non-survival), while features in blue decrease it (survival).

Discussion

In this multicenter retrospective study, we developed and validated RealMIP, a novel end-to-end framework that enables real-time mortality prediction for critically ill patients by leveraging generative modeling to impute missing values. Unlike previous approaches that utilize static or two-stage real-time models, RealMIP is specifically designed to handle the irregular and incomplete nature of ICU data. It can automatically impute missing values by utilizing the entire patient history information and modeling inter-variable relationships. By integrating real-time imputation with dynamic risk assessment, RealMIP provides timely, accurate, and interpretable predictions that adapt to each patient’s changing clinical status. Validation on both US and European cohorts supports the potential of this approach to advance clinical decision support in critical care.

Timely and accurate clinical decision support is crucial in the ICU for optimizing resource allocation, guiding interventions, and prioritizing candidates for organ transplantation20. However, most existing risk scores and predictive models are static, providing only a single mortality estimate at a fixed time point (such as 24 h after admission)21,22,23. This approach fails to capture the dynamic evolution of patients’ clinical status and, as a result, cannot provide real-time, actionable support for patient management. While some recent efforts have developed real-time prediction models, these have often been limited to the initial 24 h after admission or have focused on long-term outcomes, restricting their practical utility for ongoing ICU care13. In addition, many of these models extract summary statistics—such as hourly means, variances, or other aggregated features—from patient data streams, and then generate predictions at set intervals (e.g., every hour)8,9,13. While this approach smooths over data irregularities, it fails to capture the true dynamics of a patient’s evolving condition, as it does not fully utilize the latest information. In contrast, RealMIP provides an updated prediction each time any clinical variable is measured, thereby maximizing the real-time responsiveness of risk assessment. However, making predictions at every variable update introduces a new challenge: the resulting data points often contain substantial missingness, since few features are measured simultaneously. This represents a significant barrier to achieving truly real-time clinical prediction, which previous research has not adequately addressed.

Robust imputation methods are essential to address the pervasive issue of missing data in real-time ICU settings. Traditional approaches such as forward filling, mean or median imputation, and even some basic machine learning techniques often fail to capture the complex temporal and inter-variable dependencies in clinical data, potentially resulting in biased or suboptimal predictions. To overcome these limitations, we introduced diffusion models—a new class of deep generative models that have recently demonstrated superior performance compared to generative adversarial networks and variational autoencoders in domains such as image generation, natural language processing, and structured data synthesis24,25,26. Their strong capacity to model complex data distributions and generate realistic samples makes them particularly advantageous for imputing missing values in highly sparse and irregular ICU datasets. Notably, our findings demonstrate that, when used for missing data imputation, the diffusion-based approach in RealMIP leads to a significant improvement in the predictive performance of commonly used early warning scores such as NEWS and MEWS, compared to conventional forward imputation. This underscores the potential of advanced generative models to enhance the accuracy and reliability of real-time clinical risk prediction in critical care settings.

Another key feature of our framework is the adoption of an end-to-end training strategy, which allows the imputation and prediction networks to be optimized jointly within a unified architecture27. This approach enables the model to learn imputation patterns that are most beneficial for downstream mortality prediction, rather than merely reconstructing missing values in isolation. To validate this design choice, we conducted ablation studies comparing the end-to-end approach with a conventional two-stage pipeline, in which imputation and prediction are trained separately. The results, confirmed by DeLong statistical tests, demonstrate that the end-to-end framework consistently achieves superior predictive performance. This highlights the advantage of integrated optimization in aligning the imputation process more closely with the ultimate clinical prediction objectives28,29.

Model interpretability plays a crucial role in fostering clinical trust and facilitating the translation of machine learning models to real-world critical care environments30,31,32. By incorporating SHAP algorithm, our framework provides both global and individualized insights into the key factors driving mortality risk predictions. The identification of physiologically plausible variables—such as FiO2, GCS, SBP, age, and SpO2—as primary contributors to risk aligns our findings with established clinical knowledge, further enhancing the model’s credibility33,34. Moreover, the ability to visualize dynamic changes in feature importance over time, as patients approach critical events, offers valuable transparency into the evolution of patient risk profiles. At the individual level, RealMIP not only delivers interpretable real-time risk assessments but also enables clinicians to trace how imputed and observed variables affect predictions at each time point. This level of interpretability is particularly beneficial for clinical decision support, as it allows healthcare professionals to understand and trust model outputs, identify possible interventions, and monitor the impact of therapeutic strategies over time.

The applicability of a predictive model in clinical practice is as important as the predictive performance. The data used by RealMIP are routinely measured vital signs and laboratory tests in the ICU, and the real-time update of each new value is exploited, so it has a good potential to use real-time data for automated mortality prediction. RealMIP is used to predict short-term mortality in real time, and the prediction performance of the model improves as death approaches, both on internal and external data sets, which reflects the real-time prediction ability of the model. Furthermore, the real-time interpretability of the model, including interpretation of both existing and imputed data, suggests its potential application as a clinical decision support tool in clinical practice.

This study has several limitations. First, studies are retrospective and may be biased, requiring prospective validation. Second, while RealMIP can accurately predict in-hospital mortality when available data are limited, the model-generated data cannot fully replace real patient data, which remain essential for optimal accuracy in prediction. Third, although the SHAP algorithm was used to provide explanations for the model’s predictions, it is important to note that the influence of features on predictions does not necessarily correspond to causal relationships. Further investigation into causal relationships is needed. Finally, there is a potential risk of overreliance on imputed variables in life-critical decision-making. In the ICU, where rapid physiological changes often drive urgent interventions, imputed values should be interpreted as complementary information rather than substitutes for real measurements. Future applications should highlight the distinction between observed and imputed data to ensure safe clinical use.

This study introduces RealMIP, a novel end-to-end framework for real-time mortality prediction in critically ill patients. By leveraging generative modeling for missing value imputation and integrating dynamic risk assessment, RealMIP effectively addresses the challenges posed by incomplete and irregular ICU data. This enables the generation of timely and interpretable predictions that accurately reflect patients’ evolving clinical conditions. Our multicenter evaluation demonstrates the robust and generalizable performance of RealMIP, as well as its potential to enhance traditional early warning systems. In the future, prospective studies will be conducted to further validate the clinical utility of RealMIP and assess its impact on patient outcomes.

Methods

Study population

This retrospective study analyzed data from patients admitted to the ICU on three different cohorts: eICU-CRD17, MIMIC-IV18, and SICdb19. The eICU-CRD includes data associated with over 200,000 admissions to ICUs across 208 United States hospitals, from 2014 to 2015. The MIMIC-IV database encompasses 431,231 admissions treated in the ICU or emergency department at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) from 2008 to 2019. The SICdb offers insights into over 27,000 ICU admissions between 2013 and 2021 from four different intensive care units at the University Hospital Salzburg.

Admissions were excluded if patients were younger than 18 years, had a “do not resuscitate” order, had an ICU stay longer than 60 days, or were missing all variables required for modeling.

Ethical approval

The MIMIC-IV is publicly available after Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval by the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, MA, USA, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, MA, USA. The eICU-CRD is publicly available with appropriate IRB approval from 208 hospitals in the USA. The SICdb is publicly available with appropriate IRB approval from the local ethical commission of the Land Salzburg, Austria. All databases contain anonymized patient information, eliminating the need for individual informed consent. The principal investigator, P.X., obtained data access after completing the required National Institutes of Health courses and passing the associated assessments (Record ID: 51524821). This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki35.

Data extraction and preprocessing

Building on prior research and the clinical expertise of specialists, we identified 34 variables, including age, sex, vital signs, and laboratory results, that are readily available in most hospital settings11,14,16. Samples were generated at each time point where at least one variable was available. Consequently, any variables not documented at that specific time point were considered missing. Values outside the predefined range are treated as missing data. The predefined ranges and proportion of missing values are shown in Table S5.

To ensure a fair comparison between RealMIP and all comparator models, we applied the same preprocessing steps across cohorts and methods. These steps included standardized variable extraction, clinically plausible range filtering, normalization, and the construction of two temporal features: (i) time since the last available vital sign measurement, and (ii) time since the last available laboratory test.

The only methodological difference lay in the treatment of missing data. Comparator machine learning models were provided with explicit masking indicators for missingness, together with a two-stage imputation strategy consisting of (i) median imputation based on the training set distribution, followed by (ii) forward filling using the most recent observed value. By contrast, RealMIP does not rely on explicit missing-value indicators or predefined imputation rules. Instead, it integrates imputation and prediction in a fully end-to-end manner, implicitly capturing patterns of missingness within its generative process. This design allowed RealMIP to exploit correlations among variables and temporal dynamics while avoiding limitations of rule-based filling methods that are disconnected from the prediction task, which are typically used in conventional ICU risk models.

The clinical outcome of interest was all-cause in-hospital mortality in the ICU. For patients who died in the ICU, samples were collected within 24 h prior to death. Conversely, for patients who survived their ICU stay, samples were drawn throughout their entire ICU admission period.

Training and testing data sets

For model training, we randomly selected patients from 188 centers within the multicenter eICU-CRD dataset. Patients from an additional 20 centers comprised the internal test set. Optimal hyperparameters for the model were determined through five-fold cross-validation conducted on the training set. The MIMIC-IV and SICdb datasets served as external test cohorts.

Model development

Samples were obtained at any time point where at least one variable was present, maximizing data utilization for accurate real-time prediction. However, this approach also introduced numerous missing values. To address this challenge, we propose RealMIP: an end-to-end model designed for real-time missing data imputation and mortality prediction. As shown in Fig.2c, RealMIP differentiates itself from traditional missing data filling methods in the real-time mortality prediction of ICU patients. Traditional methods often employ median or mean imputation for initial missing values and use forward imputation for other missing values. A significant limitation of this approach is its assumption that a patient’s measurements remain constant until new data is available, thereby neglecting trends over time and inter-variable correlations. This oversight can impede accurate real-time assessment of patient conditions and prognostic predictions. Moreover, the traditional imputation method operates as a two-stage process, lacking integration with the downstream prediction model and potentially resulting in suboptimal subsequent predictive performance. RealMIP addresses these issues by employing a diffusion model for missing data imputation, which has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance in various fields such as image and text generation25,26,36. RealMIP enhances prediction accuracy by capturing the temporal patterns of variables and their correlation structures, while simultaneously optimizing both the data imputation and prediction network.

The experiments were conducted on a system equipped with a 3.50 GHz 13th Gen Intel(R) Core (TM) i5-13600KF CPU and an NVIDIA RTX A6000 GPU (48 GB memory). RealMIP was trained using the AdamW optimizer with a weight decay of 0.0001, β1 of 0.9, and β2 of 0.999. The learning rate was set to 0.0001, the batch size to 8, and training was performed for a maximum of 200 epochs. The RealMIP model is lightweight (4.10 MB) and achieves efficient inference, processing an average of 392.5 samples per second on the RTX A6000 GPU and 23.2 samples per second on the i5‑13600KF CPU.

Comparative models

RealMIP’s performance was benchmarked against nine established approaches, including traditional early warning scores designed for real-time monitoring (NEWS and MEWS), widely used clinical severity scoring systems (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment [SOFA] and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II [APACHE-II])37,38. Additionally, we included a linear model, Logistic Regression (LR), as well as several tree-based machine learning models like Random Forest (RF)39, eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost)40, and Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM)41. For deep learning approaches, we examined the Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) model, which is commonly employed for time series prediction tasks42. The hyperparameters for each model were optimized using five-fold cross-validation within the training set to ensure robust and reliable evaluations.

Model evaluation

For RealMIP and other comparative methods, the classification cutoff threshold was determined using the Youden index during the cross-validation process on the training cohort, and this threshold was applied consistently to the internal and external test cohort for evaluation. However, to facilitate comparison in the typical ICU setting where scoring systems are used for assessing the real-time severity of a patient’s condition, the NEWS and MEWS models adopted their commonly accepted thresholds: NEWS at ≥5 and ≥7, and MEWS at ≥4 and ≥5. This approach ensures a meaningful comparison under standard ICU practices. In addition to AUC, we assessed the models using 7 performance metrics: balanced accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, F1 score, PPV, NPV, and FAC/100 pt-days. Confidence intervals (CIs) for these estimates were derived using 1000 bootstrap samples to ensure statistical robustness.

To examine the reliability of the models’ probability estimates, we utilized calibration curves alongside ECE and Brier scores. Furthermore, we conducted DCA to appraise the clinical utility of the models in practice. DCA was performed by quantifying net benefit (NB) across a range of threshold probabilities. The net benefit at a given threshold \({p}_{t}\) is defined as:

where TP and FP denote the number of true positive and false positive predictions, respectively, and N is the total number of patients. This formulation incorporates both discrimination and clinical consequences by weighting false positives according to the relative harm of unnecessary interventions versus missed events. The threshold probability range was set to 0.01 to 0.99 in increments of 0.01, consistent with prior methodological guidance. This range reflects the probability thresholds at which a clinician might reasonably intervene, balancing overtreatment and undertreatment risks in critically ill patients. Because our dataset included longitudinal measurements (multiple time points per ICU admission), analysis was conducted at the patient level rather than per sample, to avoid double-counting events. Specifically, all predicted probabilities from the same admission were aggregated into a single patient-level probability by taking the arithmetic mean. This approach yields a stable estimate of the patient’s overall risk burden during ICU stay, while preventing inflation of net benefit due to repeated measurements.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. To assess differences in predictive power between models, we employed the DeLong test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

Model explanation

To interpret the model’s predictions, we utilized the Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) algorithm, which supports both global and local feature importance analysis43,44. To manage computational demands, we randomly selected a subset of 200 admissions that survived and 200 deceased admissions from the test set. This approach allowed us to evaluate overall feature importance, examine the temporal variation in feature importance, and produce interpretable, individualized real-time prediction results.

Data availability

The datasets from MIMIC-IV, eICU-CRD, and SICdb presented in this study can be found in online repositories: https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/2.2/, https://eicu-crd.mit.edu/about/eicu/ and https://physionet.org/content/sicdb/1.0.8/, respectively.

Code availability

The code will be made available upon acceptance of the manuscript at https://github.com/PuguangXie/RealMIP.

References

Sinuff, T. et al. Mortality predictions in the intensive care unit: comparing physicians with scoring systems. Crit. care Med. 34, 878–885 (2006).

Subudhi, S. et al. Comparing machine learning algorithms for predicting ICU admission and mortality in COVID-19. npj Digital Med. 4, 87 (2021).

van de Sande, D., van Genderen, M. E., Huiskens, J., Gommers, D. & van Bommel, J. Moving from bytes to bedside: a systematic review on the use of artificial intelligence in the intensive care unit. Intensive care Med. 47, 750–760 (2021).

Smit, J. et al. Demystifying machine learning for mortality prediction. Crit. Care 25, 447 (2021).

Koozi, H., Lidestam, A., Lengquist, M., Johnsson, P. & Frigyesi, A. A simple mortality prediction model for sepsis patients in intensive care. J. Intensive Care Soc. 24, 372–378 (2023).

Beigmohammadi, M. T. et al. Mortality predictive value of APACHE II and SOFA scores in COVID-19 patients in the intensive care unit. Can. Respir. J. 2022, 5129314 (2022).

Mumtaz, H. et al. APACHE scoring as an indicator of mortality rate in ICU patients: a cohort study. Ann. Med. Surg. 85, 416–421 (2023).

Huo, Z. et al. Dynamic mortality prediction in critically Ill children during interhospital transports to PICUs using explainable AI. npj Digital Med. 8, 108 (2025).

Meyer, A. et al. Machine learning for real-time prediction of complications in critical care: a retrospective study. Lancet Respiratory Med. 6, 905–914 (2018).

Kim, S. Y. et al. A deep learning model for real-time mortality prediction in critically ill children. Crit. care 23, 1–10 (2019).

Lim, L. et al. Real-time machine learning model to predict short-term mortality in critically ill patients: development and international validation. Crit. Care 28, 76 (2024).

Lim, L. et al. Multicenter validation of a machine learning model to predict intensive care unit readmission within 48 h after discharge. eClinicalMed. 81, 103112 (2025).

Thorsen-Meyer, H.-C. et al. Dynamic and explainable machine learning prediction of mortality in patients in the intensive care unit: a retrospective study of high-frequency data in electronic patient records. Lancet Digital Health 2, e179–e191 (2020).

Olang, O. et al. Artificial intelligence-based models for prediction of mortality in ICU patients: a scoping review. J. Intens. Care Med. 40, 08850666241277134 (2024).

Yang, M. et al. An explainable artificial intelligence predictor for early detection of sepsis. Crit. care Med. 48, e1091–e1096 (2020).

Nitski, O. et al. Long-term mortality risk stratification of liver transplant recipients: real-time application of deep learning algorithms on longitudinal data. Lancet Digital Health 3, e295–e305 (2021).

Pollard, T. J. et al. The eICU Collaborative Research Database, a freely available multi-center database for critical care research. Sci. Data 5, 1–13 (2018).

Johnson, A. E. et al. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci. Data 10, 1 (2023).

Rodemund, N., Wernly, B., Jung, C., Cozowicz, C. & Koköfer, A. The Salzburg Intensive Care database (SICdb): an openly available critical care dataset. Intensive care Med. 49, 700–702 (2023).

Zhang, Z. & Ni, H. Critical care studies using large language models based on electronic healthcare records: A technical note. J. Intensive Med. 5, 137–150 (2025).

Pang, K., Li, L., Ouyang, W., Liu, X. & Tang, Y. Establishment of ICU mortality risk prediction models with machine learning algorithm using MIMIC-IV database. Diagnostics 12, 1068 (2022).

Chia, A. H. T. et al. Explainable machine learning prediction of ICU mortality. Inf. Med. Unlocked 25, 100674 (2021).

Safaei, N. et al. E-CatBoost: An efficient machine learning framework for predicting ICU mortality using the eICU Collaborative Research Database. PLoS One 17, e0262895 (2022).

Zhao, W. et al. Multi-task oriented diffusion model for mortality prediction in shock patients with incomplete data. Inf. Fusion 105, 102207 (2024).

Croitoru, F.-A., Hondru, V., Ionescu, R. T. & Shah, M. Diffusion models in vision: A survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 45, 10850–10869 (2023).

Yang, L. et al. Diffusion models: A comprehensive survey of methods and applications. ACM Comput. Surv. 56, 1–39 (2023).

Tampuu, A., Matiisen, T., Semikin, M., Fishman, D. & Muhammad, N. A survey of end-to-end driving: Architectures and training methods. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 33, 1364–1384 (2020).

Dhariwal, P. & Nichol, A. Diffusion models beat gans on image synthesis. Adv. neural Inf. Process. Syst. 34, 8780–8794 (2021).

Kotelnikov, A., Baranchuk, D., Rubachev, I. & Babenko, A. in International Conference on Machine Learning. 17564–17579 (PMLR).

Liu, M. et al. A scoping review and evidence gap analysis of clinical AI fairness. npj Digital Med. 8, 1–14 (2025).

Jaiswal, N., Samsel, K. & Celi, L. A. Regulation of Artificial Intelligence in Health Care and Biomedicine. JAMA 333, 1003–1003 (2025).

Dapamede, T. et al. DICOM LUT is a Key Step in Medical Image Preprocessing Towards AI Generalizability. J. Imag. Info. Med. 38, 1–9 (2025).

Li, G. et al. Risk factors for mortality in patients admitted to intensive care units with pneumonia. Respiratory Res. 17, 1–9 (2016).

Mattison, M. L., Rudolph, J. L., Kiely, D. K. & Marcantonio, E. R. Nursing home patients in the intensive care unit: risk factors for mortality. Crit. care Med. 34, 2583–2587 (2006).

Carlson, R. V., Boyd, K. M. & Webb, D. J. The revision of the Declaration of Helsinki: past, present and future. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 57, 695–713 (2004).

Borisov, V. et al. Deep neural networks and tabular data: A survey.IEEE Trans Neural Networks Learn. Syst. 35, 7499–7519 (2022).

Ahn, J. H. et al. Predictive powers of the Modified Early Warning Score and the National Early Warning Score in general ward patients who activated the medical emergency team. PLoS One 15, e0233078 (2020).

Mitsunaga, T. et al. Comparison of the National Early Warning Score (NEWS) and the Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS) for predicting admission and in-hospital mortality in elderly patients in the pre-hospital setting and in the emergency department. PeerJ 7, e6947 (2019).

Breiman, L. Random forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Chen, T. & Guestrin, C. In Proceedings of the 22nd acm sigkdd international conference on knowledge discovery and data mining. 785–794.

Ke, G. et al. Lightgbm: A highly efficient gradient boosting decision tree. Adv. Neural Info. Proc. Syst. 30, 3149–3157 (2017).

Graves, A. & Graves, A. Long short-term memory. Supervised sequence labelling with recurrent neural networks, 37–45 (2012).

Xie, P. et al. Development and validation of an explainable deep learning model to predict in-hospital mortality for patients with acute myocardial infarction: algorithm development and validation study. J. Med. Internet Res. 26, e49848 (2024).

Xie, P. et al. An explainable machine learning model for predicting in-hospital amputation rate of patients with diabetic foot ulcer. Int. wound J. 19, 910–918 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The present study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NO. 62076247, NO. 61701506), the Graduate Research and Innovation Foundation of Chongqing, China (NO. CYB240046), and Joint Science and Health Medical Key Research of Chongqing (NO. 2025ZDXM009).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Scientific guarantor, Y.M., J.J.X.; study concepts or data acquisition or data analysis, all authors; manuscript drafting or manuscript revision for important intellectual content, all authors; approval of final version of submitted manuscript, all authors; agrees to ensure any questions related to the work are appropriately resolved, all authors; literature research, P.G.X., H.Y.; experimental studies, P.G.X., H.Y., J.L.; and manuscript editing, J.L., Y.M., J.J.X.; all authors have accessed and verified the study data.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, P., Hu, Y., Li, J. et al. Unlocking the potential of real-time ICU mortality prediction: redefining risk assessment with continuous data recovery. npj Digit. Med. 8, 733 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02114-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-02114-y