Abstract

Gait impairments are among the most prevalent and disabling symptoms in Parkinson’s Disease (PD), featuring complex and highly heterogeneous manifestations. Here, we propose a deep learning-based framework to assess gait impairments using smartphone-recorded videos. This framework demonstrated high proficiency in predicting PD severity, with a micro-average area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) of 0.87 and an F1 score of 0.806, comparable to the average performance of three clinical specialists. Additionally, it effectively discerned the comprehensive efficacy of medications on gait impairments with a precision of 73.68%. In particular, it demonstrated the ability to discriminate medication-induced fine-granular gait changes beyond the resolution of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS). Furthermore, our interpretable framework enabled the extraction of traditional clinically used motion markers and the discovery of novel digital biomarkers sensitive to disease progression and medication response. The findings underscore its great potential for efficiently assessing disease progression in both clinical and home settings, as well as evaluating disease-modifying effects in clinical trials to promote personalized therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most prevalent progressive neurodegenerative disorder, affecting more than 10 million people worldwide, and its incidence increases significantly as the global population ages1. Gait impairments are among the most common and disabling symptoms in PD, characterized by intricate underlying mechanisms and substantial individual variation in clinical manifestations2. Current interventions, including pharmacological3, non-pharmacological4, and neuromodulatory therapies5, still yield inconsistent effects on gait impairments across patients with PD and disease stages2. Precise and routine assessment of PD-induced gait impairments is crucial for elucidating underlying mechanisms, understanding disease progression, developing personalized intervention strategies, and ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Leveraging objective gait parameters to assess the PD progression and effectiveness of different interventions has been an emerging trend and a considerable challenge in clinical practice6,7. Although clinical rating scales, like the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS), are still commonly used for PD diagnosis, their low sensitivity, inherent subjectivity, and dependency on clinical specialists limit their utility in routinely assessing gait impairments for monitoring disease progression and evaluating treatment responses8 Recent clinical studies have employed a few easily calculable gait parameters, such as gait speed and step length, to assess PD severity9,10,11,12,13. However, relying on single or limited gait features fails to comprehensively portray the severity of gait impairments or evaluate the treatment efficacy. Because PD-induced gait impairments display complex and diverse spatiotemporal motion characteristics, such as slow gait speed, shortened step length, reduced amplitude of arm swing, reduced smoothness of locomotion, increased interlimb asymmetry, increased gait variability, and impaired rhythmicity2. While motion capture systems can accurately measure various gait features14,15, their high costs and professional operation requirements hinder their acceptance as tools for routine assessment. Consequently, there is a substantial need for objective and precise routine assessment methods that are able to thoroughly reflect the severity of gait impairments and illuminate the complex relationships between various gait parameters and individual disease progression, alongside their responsiveness to interventions, which remain poorly understood16.

Machine learning combined with sensing devices has been a promising modality for PD assessment17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. Most existing methods primarily focused on quantifying PD symptoms with specific and distinct characteristics of movement disorders, such as tremors and bradykinesia17,22,24, particularly in the upper extremities. A small body of studies has developed systems to assess gait impairments using a single wearable device embodied with an inertia measurement sensor, such as a smartwatch17,23 and smartphone21, or fixed radio sensors at home25 for longitudinal monitoring. Despite these advances, such approaches are restricted to monitoring limited gait features linked to specific body parts and cannot track detailed movements across all PD-affected regions. Conversely, video-based approaches can overcome this limitation by leveraging their inherent capability to capture diverse body movements comprehensively22,26,27,28,29. Nonetheless, current video-based methods for assessing gait impairment severity struggle to achieve clinician-level accuracy, whether employing RGB or depth cameras30,31,32. Furthermore, existing methods face considerable challenges in 1) high-resolution evaluations of gait impairments beyond clinical rating scales for accurately assessing treatment efficacy; 2) efficient identification of various motion markers for elucidating the evolutions of different gait parameters with disease progression and their interactions with treatments2. Moreover, existing video-based approaches often require multiple fixed cameras to simultaneously capture gait features to avoid the influence of body part occlusions30,31, impeding their regular application.

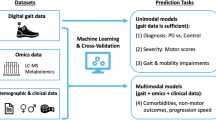

In this study, we propose a deep learning-based framework that can efficiently extract precise spatiotemporal motion characteristics of the entire body joints from gait videos recorded with a single smartphone to accurately assess PD-induced gait impairments (MDS-UPDRS Part III-Gait item) (Fig 1). By developing a novel Siamese contrastive architecture, our framework can imitate clinician’s assessment to fuse gait videos recorded from both left and right lateral perspectives during shuttle walks, ensuring accurate identification of lateral motion characteristics and comparative analysis of whole-body movements. Unlike existing methods that directly extract traditional clinical gait parameters, our interpretable framework analyzes personalized joint impacts on gait impairment severity over walking time. This approach allows us to not only extract traditional gait parameters but also discover novel digital biomarkers.

We applied this framework to a dataset with a well-balanced distribution of PD severities to highlight the model’s proficiency in accurately assessing disease severity. We effectively extracted digital biomarkers most sensitive to disease progression by correlating them with disease severity. Additionally, we demonstrated the framework’s validity in discriminating medication-induced changes in gait impairments, particularly subtle responses undetectable by the UPDRS. Furthermore, we showed the model’s capability of identifying digital biomarkers exhibiting high responsiveness to medication across patients with PD and pinpointed the body joints with associated motion biomarkers showing the highest medication responsiveness. These findings enable us to quantitatively assess the progression of PD based on smartphone videos and use the model outputs as potential outcomes in disease-modifying clinical trials, promoting personalized therapies.

The proposed smartphone video-based framework can efficiently enable home-based, objective, routine assessments of gait impairments in PD. Our results also benefit in developing objective and personalized therapies for other neurological disorders2, such as stroke33 and Alzheimer’s disease34, with similar motor symptoms and complexities as PD.

Results

Model development and evaluation

We developed and evaluated the deep learning model for assessing gait impairments based on smartphone-recorded videos from 118 participants, including 87 patients with PD and 31 healthy elderly controls (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The evaluation of the model performance consists of two phases: 1) predicting the severity of gait impairments and extracting motion markers that are sensitive to disease progression; 2) discriminating comprehensive changes in gait impairments in response to medication and identifying individualized motion markers with high responsiveness to medication interventions. The severity of gait impairments for each patient with PD was rated according to the consensus of three clinical experts based on the MDS-UPDRS Part III-Gait scales (Supplementary Fig. 3). When there is no consensus among all three experts, the agreement of two experts (i.e., the majority vote) was selected as the ground truth. In our study, there are no cases where a consensus of at least two experts was not reached. We trained the model using 558 videos from 93 participants and tested it with an independent dataset of 25 participants (Fig. 1a). Compared to assessing the severity of PD, the evaluation of the effect of medication on gait impairments is more challenging in clinical practice due to the complicated representations of gait impairments and patient-specific responses to medication. To further evaluate the validity of the model, we performed a medication response assessment with 19 patients with PD in the test dataset (Fig. 1d). The gold standard was also established through expert consensus, where three clinical specialists evaluated patients’ changes in gait impairments during off- and on-medication states, according to the UPDRS, alongside a refined three-level sub-UPDRS scoring approach. These evaluations highlight the model’s capability to perform a clinician-level accurate assessment of PD severity while also serving as an effective assessment tool for tailoring personalized treatments.

a The participants performed the shuttle walk three times over a 5-meter distance (i.e., six repetitions), and we used a smartphone to film their whole-body movements from the lateral perspective. Three clinical specialists independently rated the severity of gait impairments for each participant according to the MDS-UPDRS Part III-Gait exams. We randomly selected the gait videos from 93 participants (6 video segments per participant) to train the model and used the remaining ones from 25 participants for testing. b We developed an online assessment system for clinical and home-based assessments of gait impairments based on smartphone-recorded gait videos. c We designed a Siamese contrastive deep-learning network framework for predicting the UPDRS scores and extracting digital biomarkers. The recorded videos were automatically segmented into six parts, corresponding to six walking repetitions. The model was trained using the UPDRS scores rated by clinicians and augmented skeleton data extracted from the video segments with spatial augmentation. Skeleton data from videos recorded from both left and right perspectives were inputs for the two identical backbone networks. d We evaluated the model’s capabilities to 1) predict gait impairment severity, 2) discriminate medication effect on gait impairments, 3) extract motion markers correlated with disease progression, and 4) identify motion markers with high response (i.e., high correlation coefficients (CC)) to medication.

Model performance in predicting gait impairment severity

We evaluated the performance of the model on a test dataset comprising 150 video segments from 25 participants (six video segments per participant) (Fig. 1a). The model demonstrated a highly accurate prediction of the severity of gait impairments, with a precision of 0.804, a recall of 0.811, a specificity of 0.898 and an F1 score of 0.806 (Table 2). These values are comparable to the average results achieved by three clinical specialists (Table 2 and Supplementary Table I). The model correctly predicted 86% cases with a score of 0, 70% with a score of 1, and 88% with a score of 2 (Fig. 2a). The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve demonstrated robust model performance in various UPDRS categories (Fig. 2b). The model achieved an area under the ROC curve (AUC) of 0.93 for the UPDRS score of 0, 0.78 for the score of 1, and 0.92 for the score of 2, with a micro-average AUC of 0.87. These high AUC values further highlighted the model’s effectiveness in accurately predicting the severity of gait impairments. Furthermore, we assessed the model’s performance on the validation dataset through a 5-fold cross-validation procedure, wherein the model achieved an enhanced F1 score of 0.82 and an elevated micro-average AUC of 0.92 (Fig. 3).

a Confusion matrix of the UPDRS score prediction on the test dataset. b The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for each severity category. The model achieved a high area under the ROC curve (AUC) with a micro-average AUC of 0.87. c–f Agreements between the ground truth scores and those rated by the AI model and three experts for the test dataset. Within the large squares, each small square represents a participant as depicted in the top right corner of (c). Blue, yellow and red squares indicate perfect agreements, one-score discrepancy, and two-score discrepancies, respectively. g–i Agreements between the scores predicted by the AI model and the ones rated by the three experts. j The error rates of predicted UPDRS scores of the experts and the AI model, compared to the ground truth. AVG represents the average error rate of three experts. The error rate of the AI model is close to the average one of three experts (0.2 vs 0.19).

a The confusion matrix of the UPDRS score prediction. b The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for each severity category, as well as the area under the ROC curve (AUC) and the micro-average AUC. c Performance metrics including macro precision, recall, specificity, F1 score and AUC. Except for recall, which remained constant, all other performance metrics exhibited slight improvements compared to those with the test dataset (Table 2 and Fig. 2). Notably, the AUC increased by 0.05.

Model alignment with scores rated by clinical experts

We analyzed the alignments among the UPDRS scores rated by the AI model and the three experts and the ground truth scores for the participants in the test dataset (Fig. 2). The performance of the model closely resembled those of the experts, with the model having five mismatched scores compared to Expert 1 with three, Expert 2 with eight and Expert 3 with three (Fig. 2c–f). Notably, the deviations of all model’s mismatched scores were limited to one point, matching the experts’ performances. Although we trained the model based on the consensus of three experts rather than their individualized scores, interestingly, four of the five mismatched scores for the model were also not correctly rated by at least one expert. These comparisons demonstrated that the model performance is on par with the average performance of the experts (Error rates: 0.20 vs 0.19, Fig. 2j), indicating the effectiveness and reliability of the model. In addition, the results reveal the difficulties in assessing gait impairments, particularly in patients with inconsistent ratings among experts. Moreover, we observed that the scoring approach of the model is different from any of the three experts (Fig. 2g–i), although most of the rated scores of the model are the same as those of each expert. These findings underscore the model’s robust capacity to align with expert assessments, illustrating its great potential as an independent tool in accurately assessing disease severity in clinical evaluations.

Extraction of motion markers sensitive to disease progression

We first identified individualized joint contributions to the prediction of disease severity of our model for participants in both training and test datasets using a dual maximum gradient-weighted class activation mapping (DMGrad-CAM) method in conjunction with correlation analysis (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 2). Across different levels of disease severity, the foot, wrist, knee, and elbow were ranked as the primary body parts affected by the disease (Fig. 4b). This finding was consistent with typical gait characteristics observed in the clinical assessment of gait impairments, such as the reduced amplitude of arm swing, gait speed and step length as well as the diminished range of motion of the knee and ankle2. Based on the joint contributions, we first extracted the clinical commonly used biomarkers2 of gait impairments, including arm swing amplitude, gait speed, and step length (Fig. 4c–e). Arm swing amplitude demonstrated a significant correlation with disease severity, yielding a correlation coefficient of −0.64. Notably, there were significant differences (Kruskal–Wallis test: p < 0.05) in arm swing amplitudes among participants with varying UPDRS scores (Fig. 4c). In addition, lower walking speeds and shorter step lengths were significantly observed (Kruskal–Wallis test: p < 0.05) in patients with a UPDRS score of 2 compared to those with UPDRS scores of 0 and 1 (Fig. 4d, e). These results align with the PD progression of Parkinson’s disease, where a reduced amplitude of arm swing appears in the slight stage and worsens further in the mild state; slow speed and shortened step length become common in the early stage2. Since increased cadence usually appears in the moderate stage, we didn’t observe this manifestation in the patients with early-stage PD in our study (Supplementary Fig. 4). In addition to these traditional motion markers, we further discovered richer motion features consisting of the linear velocities and accelerations of the skeletal joints and the joint angles (Fig. 4a). We finally selected two types of indicators that are sensitive to disease progression: the mean of each motion feature and the variances in the means for six walking periods during three-time shuttle walk tests (Supplementary Fig. 5). The correlation analysis with the UPDRS score revealed that the mean linear velocities of the foot and knee, the variances of the velocities of the wrist, elbow and shoulder, the mean and the variances of the accelerations of the wrist and elbow can especially serve as effective digital biomarkers to reflect disease progression. In particular, the average linear velocity of the ankle, a newly identified digital marker, showed a higher correlation with the gait impairment severity (ρ = −0.66) than all three traditional motion markers. These body parts are also the ones with higher joint contributions across different disease stages, compared to the other parts (Fig. 4b). Moreover, the relatively high correlation between the variances of average velocities of the upper limbs across six walking periods and the severity of the disease aligns with clinical characteristics of gait impairments, i.e., increased gait variability2. The model, combined with interpretable joint contributions and extracted skeletal data, offers a promising approach for efficiently identifying motion markers sensitive to individualized disease progression.

a The four joints with the highest Spearman correlations to UPDRS scores among all 20 joints for each type of extracted spatiotemporal biomarkers (additional information on the remaining joints are shown in Supplementary Fig. 6). The ranges of the p-values of the Spearman correlations for each joint are displayed on the corresponding bars. We selected the largest correlation coefficients between the left and right joints for bilaterally symmetrical joints. b Joint contributions to predict the severity of gait impairment cross all UPDRS scores and each score. The joint contributions were normalized to represent the relative contribution ratios among joints for severity prediction, indicated through points with different sizes and colors. Larger and red points indicate greater normalized contributions, whereas smaller and blue joints denote lesser normalized contributions. A contribution value of 0 means the lowest contribution ratio within the analyzed joints rather than the absence of contribution. c–e The Spearman correlations between the UPDRS scores and the extracted motion markers, along with the significant differences in these markers across three disease severity categories. Spearman correlation coefficients and their p-values are displayed at the bottom of each graph. We used the Kruskal–Wallis test to analyze the statistical significance. p-values of the significance analyses between different groups are presented at the top of each graph.

Model performance in discriminating medication effect on gait impairments

To evaluate the ability of the model to discriminate changes in gait impairments caused by pharmacological interventions, we experimented with collecting gait videos from 19 patients with PD during off- and on-medication states (Table 1). According to the consensus of the three clinical specialists, the UPDRS scores (Part III-Gait scales) of seven patients changed by one score on-medication (SwC cohort), with six patients’ scores decreased and one increased, while the scores of the others remained the same (SwoC cohort). For the last cohort, the three experts further conducted a more granular sub-score comparison with three outcomes, i.e. improvement, no change, and deterioration, to differentiate changes in gait impairments of each patient between off- and on-medication states. This granular rating scale reflected subtle gait alterations after medication that cannot be indicated by a change in the UPDRS score. This comparison was repeated three times. First, we only randomly provided the gait videos of each patient recorded during off- and on-medication states to the experts without giving them the patient’s medication states. Secondly, videos aligned with corresponding medication states were provided, as well as the patient’s other medical information (Table 1). Lastly, experts were also provided with the gait characteristics extracted from the skeleton data, including stride length, gait speed, and arm swing amplitude2. This staged evaluation benchmarks our model against clinicians by comparing the model’s video-only performance to that of experts receiving progressively more data, demonstrating its ability to achieve a comparable or superior assessment with more parsimonious data inputs. In addition, this graded approach can avoid preconceptions caused by awareness of the state of the medication for clinicians. For the SwoC cohort, the consensus rating, determined by the agreement of at least two experts in the final evaluation, served as the gold standard for each patient. In instances where consensus was not achieved (i.e., the three experts gave three different ratings), a “no-change” classification was assigned, which occurred only once in our study. For the SwC cohort, the consensus was still based on changes in UPDRS scores, which were further mapped to “improvement,” “no change,” or “deterioration.” In addition, a non-expert clinician, certified in assessing PD symptoms but possessing less clinical experience than the experts, conducted the same evaluations for all 19 patients.

We introduced a comprehensive index based on the predicted scores along with their confidence levels, as generated by the model, to identify changes in gait impairments between off- and on-medication states for both the SwC and SwoC cohorts. The model demonstrated a strong capability in discriminating the effects of medications on gait impairments with an accuracy of 73.68%. This matches the best performance of the three rounds of evaluations of two experts and the non-expert clinician and only falls short by 10.53% (two patients) compared to the highest expert performance (Fig. 5a). Compared to the rating results of the three experts in the first-round evaluation based on only gait videos, the model’s accuracy was even slightly higher than their average accuracy (70.17%). For the SwC cohort, all experts exhibited a notable decrease in discrimination accuracy, indicating greater challenges in distinguishing medication-induced changes in gait impairments using UPDRS scores as opposed to merely assessing the severity of gait impairments (Fig. 5c and Table 2). However, the comprehensive index derived from our model significantly mitigated this issue, achieving a discrimination accuracy of 85.71%, thereby surpassing all experts. For the SwoC cohort, all clinicians achieved their highest performance in the third evaluation when receiving not only gait videos but also patient medication states and quantitative gait characteristics. The discrimination accuracy of the model is less than the best performance of the experts in the three-round evaluations; however, it matched the best performance of the non-expert, with a discrimination accuracy of 66.67% (Fig. 5c). In other words, the model outperformed the experts in distinguishing relatively significant changes in gait impairments (with a change in the UPDRS score) caused by medication based on UPDRS scores and ensured the same level as the non-expert in distinguishing insignificant gait changes (without a change in the UPDRS score). It is important to note that the clinical commonly-used gait characteristics, including arm swing amplitude, step length, velocity, and their combination, cannot effectively differentiate gait changes between off- and on-medication based on their significance analysis in gait changes, giving a precision ≤42.11% (Fig. 6a). Interestingly, the correlations between the outcomes of the medication in gait impairments determined by the model, the clinicians, and the gait characteristics revealed that the model’s performance had more explicit relationships with the gait characteristics compared to the clinicians’ discrimination (Fig. 5b). These findings demonstrate that our model can efficiently extract representations of skeletal data that reflect medication-induced gait changes; meanwhile, it can significantly outperform these traditional gait biomarkers to perform expert-level discrimination of changes in gait impairments caused by medication. This highlights its potential as a valuable tool for evaluating the effectiveness of medical therapies.

a The accuracies in discriminating the patient outcomes by three expert clinicians, a non-expert clinician, the AI model, and the significant changes in the traditional clinical motion markers. For the sub-UPDRS score assessment, three experts performed three rounds of independent assessments of the patient outcomes with different sets of information: 1) solely gait videos, 2) gait videos accompanied by medication status and disease details (Table 1), 3) gait videos with medication status and disease details, supplemented by values of traditional motion markers measured in both off and on medication states (Fig. 4). b The Spearman correlation coefficients (ρ) between the patient outcomes discriminated by clinicians, AI model, and the clinical motion markers, with thicker chords indicating stronger correlations. c Discrimination accuracies of the three experts, the non-expert clinician, and the AI model for different cohorts: 1) 7 patients with changed UPDRS scores after medication (SwC cohort), 2) 12 patients without changed UPDRS scores after medication (SwoC cohort). Note that for assessing the medication’s effect on gait impairments in the SwC cohort, the non-expert clinician used a granular three-level sub-score rating approach. The three experts' ratings were still derived from changes in the standard UPDRS scale.

a Percentages of patients with PD (N = 19) with significant changes (PwSC) (p < 0.05) in different motion markers between off- and on-medication states. Meanwhile, we only considered those with significant changes that agree with the medication efficacy rated by clinical specialists. For each type of newly extracted spatiotemporal digital biomarker, we present the top three joint points with the highest percentage of patients. The Top-4 indicates the total percentage of patients with significant changes in at least one of the top four spatiotemporal markers. In contrast, the WHA represents those for the combined traditional clinical motion markers. A voting was used when the markers displayed inconsistent significant changes. b Proportions of patients with PD (N = 19) exhibiting significant changes (p < 0.05) in one or multiple markers among the Top-4 spatiotemporal and WHA traditional markers. c Percentages of patients (N = 19) showing significant changes (p < 0.05) in motion markers associated with different joints (the motion markers' changes should be consistent with the rated medication outcomes).

Identification of digital biomarkers with high responsiveness to medication

In addition to comprehensively determining the outcomes of pharmacological interventions using our model, we identified motion markers with high responsiveness to medication across patients with PD. We used the percentage of patients (N = 19) showing significant changes (p < 0.05) in different motion markers between off- and on-medication states to highlight the markers and the corresponding body joints sensitive to medication. We only considered the cases in which significant changes in the motion markers aligned with the consensus on medication efficacy rated by three clinical specialists.

For the newly extracted spatiotemporal digital biomarkers, the linear accelerations of the neck and head, and the standard deviations of the elbow and neck joint angles, demonstrated relatively high inter-patient response to medication outcomes (Fig. 6a). Notably, 42.11% of patients showed significant changes in these four digital biomarkers consistent with medication outcomes rated by clinical experts. The inter-patient medication responsiveness for these digital biomarkers was higher than that of traditional clinical motion markers (31.58%), such as arm swing amplitude, walking speed, and step length (Fig. 6a). For any single spatiotemporal marker or traditional motion marker, the percentage of patients with significant changes was relatively low (any spatiotemporal marker: ≤42.11%; any traditional motion marker: ≤31.58%) In contrast, combining changes in several key motion markers can more accurately reflect medication effects on gait impairments across a broader patient group. It was shown that 63.16% of patients exhibited significant changes in at least one of the four newly extracted spatiotemporal markers matching their rated medication outcomes, compared to just 42.11% with substantial changes in the traditional markers (Fig. 6a). Here, we used voting results to verify alignment with patient medication outcomes if these markers displayed inconsistent significant changes. These results highlight the challenge of identifying a universal digital biomarker for indicating medication efficacy and underscore the importance of developing personalized treatments based on comprehensive changes in multiple key motion markers, especially the extracted spatiotemporal markers. Fig. 6b detailed the proportions of patients with PD exhibiting significant changes (p < 0.05) in one or multiple markers among the Top-4 spatiotemporal and Top-3 traditional markers. Only 15.79% and 21.05% of patients showed significant changes in all Top-3 traditional and Top-4 spatiotemporal markers, respectively. However, these percentages are still remarkably higher than those exhibiting significant changes in 1–2 traditional or 1–3 spatiotemporal markers (≤ 10.53%), respectively. These results further demonstrate the clinical heterogeneity of PD, indicating that medications have varying effects on different motor symptoms across individuals.

Furthermore, we analyzed the effects of medication on motor abilities of different body parts, taking into account both the Top-4 spatiotemporal and Top-3 traditional markers. Our findings indicated that motion markers associated with the neck, head, elbow, knee, hip showed higher inter patient medication responsiveness (with 57.86%, 52.63%, 43.37%, 42.11%, 42.11% patients, respectively), compared to other joints (Fig. 6c). Notably, the average linear velocities and accelerations of the head and neck serve as key motion markers with high response to medication across patients. The results also demonstrate the capability of the proposed framework for identifying different medication effects on various body parts. Detailed changes in these motion markers for all nineteen patients between off- and on-medication states are presented in Supplementary Figs. 7–10.

Discussion

We proposed a deep learning model using smartphone videos to quantitatively assess PD-induced gait impairments and discriminate the effect of pharmaceutical intervention on gait impairments. Based on the proposed model, we further extracted motion markers with explicit responsiveness to disease progression and medical treatment. The model was trained on a dataset with 93 participants that are classified into three categories according to the disease severity. To reduce the influence of subjectivity and inter-rater variability (IRV), the consensus of three clinical experts was used to label the severity of the disease for each participant according to the MDS-UPDRS Part III-Gait scales and to evaluate gait impairment alterations between off- and on-medication states according to UPDRS scores along with a specialized assessment score that offers greater resolution than UPDRS. The ground truths (i.e., labeled UPDRS scores) of the dataset demonstrated an excellent inter-rater reliability, with an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.8019,22. The model exhibited expert-level performance in predicting the UPDRS scores of an independent test dataset with 25 participants and extracted various motion markers whose changes are consistent with the clinical manifestations of PD disease at different severity stages. The model also performed an effective identification of the patient’s response on gait impairments to medical treatment, with the same discrimination precision (73.68%) as that of two of three experts (Fig. 5a). In particular, the model demonstrated the ability to distinguish more granular changes in gait impairment that cannot be indicated using the UPDRS score with the same precision as that of the non-expert clinician who used the fine-grained rating method. For the SwC cohort, our model achieved 85.71% accuracy, matching that of the non-expert clinician and outperforming the three experts (accuracies of 57.14–71.43%) who rated based on the UPDRS scale. For the SwoC cohort, although the experts performed at a higher level of accuracy using the granular three-level criterion, with scores ranging from 83.3% to 91.67% (the best performance), the model’s accuracy (66.67%) remained comparable to that of the non-expert (66.67%). These findings underscore the great potential of the model in precisely tracking disease progression and response to treatments over time, enhancing understanding of the fundamental mechanisms of gait impairments, and paving the way for the development of personalized therapies. In addition, we developed an online assessment system based on the model to allow home-based routine assessment of gait impairments, efficiently addressing the challenges in routine quantitative evaluation caused by the complicated representations of gait impairments35.

Our model achieved an accurate and robust assessment of the severity of gait impairment, which mainly lies in the design of the novel contrastive network architecture and a weight-sharing mechanism, enabling our model to extract gait spatiotemporal features from videos recorded from left and right perspectives simultaneously. Despite advancements in sensing techniques for assessing gait impairment severity, existing methods29,30,31,32,36 continue to face challenges in enhancing assessment accuracy. The best-reported performances across studies are constrained with an F1 score of 0.77, a precision of 0.782, or an AUC of 0.83, while our model improved the F1 score, accuracy, and AUC to 0.806, 0.811, and 0.93, respectively. For instance, a recent well-structured model26,37 was developed to predict the 4-level severities (i.e., UPDRS scores of 0, 1, 2, 3) of gait impairments using a 3D skeleton extracted from videos recorded from a frontal perspective. That model, evaluated with a dataset consisting of 31 patients with PD and 23 controls without PD, reported an AUC of 0.8 and an F1 score of 0.76 during a leave-one-out cross-validation. Given the inclusion of only four patients with a UPDRS score of 3 in that study, we compared our model to that model. In contrast, our model demonstrated superior performance, achieving a 0.12 boost in AUC and a 0.06 increase in F1 score during a 5-fold cross-validation on a substantially larger dataset comprising 93 participants (Fig. 3). These findings demonstrated the improved precision, efficiency and robustness of our model over existing ones in assessing the severity of PD. To the best of our knowledge, we are the first to demonstrate that a video-based model can achieve an assessment accuracy comparable to that of clinical experts, highlighting its potential as an independent tool for gait impairment diagnosis in clinical and home-based settings. The robustness of the model was further emphasized by verifying it on a relatively large dataset with well-balanced categories compared to those used in current methods25,30,32,38.

The proposed quantification approach utilizing smartphone-recorded videos efficiently balances two critical requirements for routine assessment of gait impairment severity: capturing more motion features to enhance accuracy while minimizing sensors used to improve acceptance and usability. Our approach can be effectively used for longitudinal monitoring of gait impairments and analyzing the impact of significant daily events, such as on-off medication. In addition, our model, based on the analysis of joint contributions to disease severity, is capable of extracting not only highly correlated traditional motion markers but also a broad spectrum of digital biomarkers to reflect disease stages, such as linear accelerations of wrist and elbow, linear velocities of foot and knee, variances of linear velocities of elbow, wrist and shoulder. The extracted traditional motion markers of disease progression are consistent with the findings of recent studies using wearable devices17,23 or radio waves25. For example, our analysis revealed significant negative correlations between disease severity and arm swing amplitude (Spearman: ρ = −0.64, p < 0.001), gait speed (Spearman: ρ = −0.62, p < 0.001), and step length (Spearman: ρ = −0.59, p < 0.001). These findings align with previous work, which also reported significant correlations between disease severity and arm swing amplitude (Pearson: r = −0.31, p = 0.008)39, step length (Pearson: r = −0.519, p < 0.001), and gait speed (Pearson: r = −0.433, p = 0.001)40. The new digital motion markers can provide deeper insights into personalized gait impairments associated with disease progression and clinical treatments2. For instance, the wrist acceleration biomarker identified in our study aligns with recent findings from a study on a large dataset (UK Biobank), which demonstrated that wrist acceleration measured using a wrist-worn triaxial accelerometer, when analyzed with a machine learning model, can better distinguish clinically diagnosed PD (with a Area Under Precision Recall Curve (AUPRC) = 0.14 ± 0.04) and prodromal PD up to seven years pre-diagnosis (AUPRC = 0.07 ± 0.03) from the general population, compared to traditional biomarkers, such as genetics (AUPRC = 0 .01 ± 0 .00) and blood biochemistry (AUPRC = 0.01 ± 0.00)23. Similarly, the correlation between wrist acceleration and gait impairment severity was also observed in another study, which found a correlation of ρ = −0.46 between arm swing acceleration and clinical gait scores using a wrist-worn wearable device17. Compared to these methods, our model, leveraging smartphone-recorded videos, successfully addresses the limitations of wearable-sensor-based methods by enabling the comprehensive capture of motion features across diverse body regions while ensuring patient acceptability.

To bridge the gap between the high demand for accessible and comprehensive analyses of the effectiveness of pharmaceutical interventions on gait impairments and the critical paucity of relevant assessment methods, we developed an approach to discriminate changes in gait impairments caused by medication, leveraging the model and confidence values of its outputs, without retraining it. As the low sensitivity of the UPDRS score limits its ability to capture all the nuances of gait metrics and their abnormalities8, it cannot be used to adequately reflect changes in gait impairments41, particularly medication-induced changes in gait8. On the other hand, an expert clinician can often perceive fine-grained improvements in movement quality that are not significant enough to change a UPDRS score42,43. Hence, we introduced a refined three-level sub-UPDRS scoring approach. In our study, the UPDRS scores of 12 out of 19 patients did not change after medication, while only one patient’s score was still rated ’no change’ when clinicians used a higher resolution assessment method. So far, few motion markers (normally the speed) have been used to evaluate the effect of interventions25. A major constraint behind this is the lack of easily accessible means to perform a quantitative and comprehensive assessment. Our framework demonstrated a capability to accurately identify changes in gait impairment in patients with PD after medication with a precision of 73.68%, which slightly surpasses the average proficiency of the clinical experts based on only gait videos and matches the precision of two of them when supplemented with information on medication states and gait characteristics. The comprehensive index, derived from our model, demonstrated an accuracy of 85.71% in identifying medication-induced outcomes on gait impairments as indicated by the changes of UPDRS scores, remarkably exceeding the average accuracy of clinical experts, which was 61.9%. Furthermore, it accurately identified gait changes undetectable by UPDRS scores, reaching the accuracy level of a non-expert clinician with a fine-granular assessment method. Since UPDRS is limited by its subjective, coarse and semi-quantitative nature44,45, it is insensitive to subtle but potentially significant motor fluctuations2, particularly in response to treatment46,47. Our fine-grained assessment method has the potential to equip clinicians with the ability to monitor fluctuations in the clinical status of a patient more objectively21, which in turn supports timely adjustments to patient management and individualized treatment strategies44,46,47.

Utilizing motion markers derived from our model, we discerned personalized medication responses in patients with PD. Notably, four digital biomarkers, including linear accelerations of the neck and head and standard deviations of the elbow and neck joint angles, exhibited relatively high inter-patient responsiveness to medication, with 63.16% of patients showing significant changes in at least one marker that aligned with the patient’s medication outcomes during the medication response test. These newly extracted spatiotemporal biomarkers demonstrated higher inter-patient medication responsiveness than traditional motion markers used in clinical studies, such as arm swing amplitude, gait speed, and step length. Furthermore, motion markers associated with the head, neck, elbow, knee, and hip showed higher inter-patient responsiveness than those linked to other joints. So far, only a few studies have used quantitative gait measures to analyze the medication response of patients with PD, mainly demonstrating that the gait speed11,25 and step length11 are sensitive to medication. Our model demonstrates the ability to identify more digital biomarkers of medication response, which can further benefit disease-modifying clinical studies and customized treatments.

There are some limitations to this study. The quality of the skeleton data, which is the direct input to our model, significantly impacts the accuracy of the assessment. Since the skeleton data come from deep learning extraction models, their accuracy directly affects the final assessment. In our study, all gait videos were captured under indoor lighting conditions. During indoor experiments, we found that subjects’ clothing affects keypoint extraction48. Loose clothing or pure black wear that obscures limb movements can cause assessment failures. Patients are suggested not to wear this kind of clothing during the assessment. We recorded the videos using smartphones with a resolution of at least 720p. These conditions are suitable for the underlying DWPose pose estimation model, indicating that factors such as poor lighting, phone type, or low resolution were not main sources of error in our study. To ensure the generalizability of the model, we implemented an assessment on a completely independent test set with 25 participants as well as a five-fold cross-validation scheme. In addition, we evaluated the performance of the model in discriminating the response of medication to gait impairments in 19 patients with PD selected from the independent test set, which means that their data were never used for training. Although the sample for this specific evaluation is not as large as that for disease severity assessment, promising preliminary results demonstrate the model’s ability to discern medication effects and highlight its significant potential for future clinical applications.

The confusion matrices for both the 5-fold cross-validation and the independent test demonstrate that the model achieved a higher accuracy for classifying UPDRS scores of 0 and 2 than classifying UPDRS scores of 1 (see Figs. 2a and 3a), suggesting that the model encounters greater challenges in distinguishing gait impairment severity with a UPDRS score of 1. This difficulty reflects an inherent challenge in the clinical assessment itself, as the distinction between these mild severity levels (score of 1) is clinically subtle, creating a blurry boundary that is challenging even for clinicians to delineate consistently. There are no significant differences in sex (Fisher’s Exact Test, test/training set: p = 0.3217/0.4219), age (Mann–Whitney U test, test/training set: p = 0.3755/0.9960) and height (Mann–Whitney U test, test/training set: p = 0.4131/0.2914) between the correctly predicted group and the mismatched group. With the test dataset, the model accurately classified all cases with identical rated UPDRS scores among the three experts and nine of the fourteen instances without a unanimous rated score (see Fig. 2), demonstrating a robust capability to handle the IRV. On the other hand, the results showed that four of the five mismatched scores (one-point difference) for the model on the test set were also incorrectly rated in the same way by at least one expert and the model error was significantly linked to the expert disagreement (Fisher’s Exact Test, test/training set: p = 0.0464/0.0022), indicating that the model faces similar challenges in assessing gait impairments in complex cases with inconsistent ratings among experts.

In our study, all data were from the same hospital and consisted exclusively of patients of one ethnicity (Asian Chinese) with a mean age of 62.9 years (±7.4 years), which may not fully reflect the diverse gait characteristics of patients with PD. In the future, we will expand the dataset by recruiting participants from different medical centers with a wider range of races, ages and disease severity. We recorded gait videos under normal indoor lighting conditions, and the use of smartphones allowed for a minimum video resolution of 720p. We will also include gait videos recorded with various types of smartphones under different indoor and outdoor environments to further improve the model’s generalization before its widespread clinical use. In addition, the model mainly focuses on assessing walking, allowing convenient application in the home setting. In the future, the model will be further expanded to assess additional tasks, such as turning, Timed Up and Go, balance, and freezing of gait, to obtain a more comprehensive diagnosis of the disease severity. Moreover, the proposed video-based model can be further integrated with other modal data from wearable sensors, such as kinematic data from inertial measurement units (IMUs)49,50and muscle activities from electromyography (EMG) sensors51, to provide more comprehensive assessment of PD symptoms related to features of specific body parts (e.g., tremor and speech) and the whole body (e.g., gait, freezing of gait, balance). Such an integration can also enable a deep insight into the relationships among different symptoms and their complex responses to the same interventions. In addition, integrating the gait videos with neuroimaging data, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and functional MRI (fMRI)26, can help further understand the mechanisms underlying gait impairments. This multidimensional assessment will provide more comprehensive guidance on Parkinson’s disease progression and the effectiveness of therapeutic interventions.

In conclusion, we developed a smartphone video-based deep learning model that accurately assessed the severity of PD-induced gait impairments (MDS-UPDRS Part III-Gait item) and discriminated the effectiveness of pharmaceutical interventions on gait impairments, including those that UPDRS scores failed to detect due to its low resolution. In addition, the interpretability of the model enabled the extraction of valuable digital biomarkers, which provide insights into disease progression and medication effects on gait impairments.

Methods

Participants and dataset

The study initially recruited 130 participants, including 99 patients with PD and 31 healthy age-matched adults as controls. Each participant was instructed to perform the shuttle walk test three times, covering a minimum distance of 10 m for each test. Meanwhile, we filmed the participants walking from the lateral perspective using a single smartphone placed at a fixed point, capturing their full body motions. This perspective is more effective for extracting key gait features, such as step length, arm swing amplitude, and gait speed, compared to frontal views26. Twelve participants were excluded from the study due to needing walking assistance (N = 3), non-compliance with the experimental protocol by raising their arms during walking (N = 2), and failure in identifying parts of the skeletons from the videos caused by the influence of loose black clothing (N = 7). Consequently, the final cohort of participants consisted of 87 patients with PD and 31 healthy controls (118 in total).

Gait videos from 118 participants, recorded during off-medication states, were independently assessed and rated by three clinical experts according to the MDS-UPDRS Part III-Gait exams. The consensus derived from the agreement of at least two experts was established as the ground truth for each participant. In instances where consensus was not reached, the average UPDRS scores of the three experts were used as the ground truth; however, no such cases occurred in our study. We constructed a balanced dataset with a distribution of UPDRS categories as follows: 38 participants with a score of 0, 39 with a score of 1, and 41 with a score of 2 (Table 1). Note that patients with a UPDRS of 4 cannot walk independently and those with a score of 3 require assistance devices. The cohort also ensured a rough gender balance with 63 males and 55 females (p > 0.05; Chi-Squared Test). Detailed demographic information of the participants is presented in Table 1.

We divided the dataset randomly into two groups: a training dataset consisting of 558 video segments from 93 participants and a test dataset comprising gait videos from 25 participants (Fig. 1a). All data splitting was performed at the participant level. This process ensures that all video segments from a single participant were contained entirely within one partition (i.e., the training set or the test set), thereby preventing data leakage. The model was trained using the training dataset, and its performance was evaluated using the independent test dataset. Initially, we assessed the model’s effectiveness in predicting the severity of gait impairments and compared it to the assessments made by individual clinical experts. Subsequently, we calculated the personalized joint contributions to the prediction of disease severity for each participant in the training and test datasets. By analyzing the average joint contributions across all participants, we evaluated the model’s ability to extract both conventionally used clinical motion markers and novel digital biomarkers that are sensitive to disease progression, based on their correlations with the UPDRS scores.

We evaluated the model’s performance in distinguishing comprehensive gait impairment outcomes in response to medication based on gait videos from the 19 patients with PD during both off- and on-medication states in the test dataset. This evaluation was accomplished by integrating the UPDRS scores predicted by the model, along with their confidence levels. To accurately evaluate the effectiveness of pharmacological interventions (Table 1) on gait impairments, we developed a fine-granular assessment approach with a higher resolution than UPDRS scores. Three clinical experts assessed the gait videos of 19 patients with PD in the test dataset (Fig. 1), recorded in both off- and on-medication states, according to the UPDRS and the fine-granular approach. Regarding medication regimens during the medication response test, sixteen patients were treated with Madopar alone, one patient received a combination of Madopar and Sifrol, and two patients were administered Madopar and Benzgexol. First, the UPDRS scores of the 19 patients were independently rated by three experts. According to the consensus of experts, changes in UPDRS scores after the medication were used to indicate alterations in gait impairments caused by the medication. For those whose UPDRS scores remained unchanged, three experts further identified changes in gait impairments using a more granular three-level sub-score criterion (i.e., improvement, no change, and deterioration). To capture the nuances in patients’ gaits with higher resolution, we asked the three specialists to independently compare all gait metrics of the same patient based on the videos recorded during off and on medication states to identify the differences between them as much as possible, then leading to one of three categories: improvement, no change, and deterioration. To avoid preconceptions caused by medication state awareness, clinicians first evaluated randomly sorted gait videos without associated medication states. Afterwards, they assessed the videos with the patient’s medication states and medical history, with a new sorted sequence. Finally, we provided them with the gait characteristics derived from the modified skeleton data, including stride length, gait speed, and arm swing amplitude2 in addition to the videos and previous information with a new order. The consensus rating, determined by the agreement of at least two experts in the final evaluation, served as the gold standard for each patient. In instances where consensus was not achieved, a “no-change" classification was assigned, which occurred only once in our study. Moreover, a non-expert clinician conducted the three rounds of fine-granular evaluations for all 19 patients. Apart from discriminating the comprehensive changes in gait impairments, we further identified individualized motion markers with high responsiveness to medication interventions by analyzing their significant changes between off and on-medication states.

Ethics declaration

Participants were recruited from Tianjin Huanhu Hospital in Tianjin, China. They were screened for Parkinson’s disease, and their clinical tests were assessed by expert neurologists specializing in movement disorders. The inclusion criterion for the patient group was a confirmed diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease and the capability to walk without assistance. Healthy controls, matched by age, were also included in the study. All participants were fully informed of the experimental procedures and provided their written consent to participate in this study. All ethical and experimental procedures and protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tianjin Huanhu Hospital, Tianjin, China, under Approval No. ChiCTR1900025372.

Data preprocessing

We developed an automated video segmenting approach to segment long shuttle walking videos into short clips that only capture directional walking to enable simultaneous analysis of left- and right-side motion characteristics. This approach works by identifying the segmentation locations via detecting peaks and valleys in the horizontal profiles of the neck keypoint and analyzing their magnitudes and the horizontal distances between them. Each gait video was automatically split into six segments of unidirectional movement (left-to-right or right-to-left), ensuring that only walking segments were included. This segmentation was consistently applied to model training, inference, and feature extraction.

We extracted the body skeleton from smartphone videos using DWPose52, considering its superior effectiveness and precision compared to the commonly used OpenPose53. Although the accuracy and robustness the DWPose have been verified on a large-scale public dataset (COCO-WholeBody54), we further verify its accuracy in extracting human skeletons in the setting of our study (see Fig. 1). We conducted a comparison experiment using a motion capture system (Vicon, UK) as the ground truth. Two healthy young subjects were asked to perform a five-meter shuttle walk test five times. We compared the key points extracted using DWPose and Vicon without considering the depth information of Vicon along the frontal axis since DWPose provides only 2D skeleton data. To align the pixel coordinate system of DWPose with the world coordinate system of Vicon, we performed a perspective transformation using a nonlinear fitting with a quadratic function. In addition, time scale alignment55 was performed to ensure synchronization between the key points extracted from both systems. We calculated the Spearman correlation coefficients for each joint’s 2D trajectories estimated by DWPose and Vicon across 16 video segments for the two subjects. The results showed a high correlation between their estimated joint’s trajectories, with a ρ ≥ 0.85 ± 0.06 in the sagittal plane and a ρ in between 0.67 ± 0.07 and 0.99 ± 0.01 in the transverse plane (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Skeleton extraction models such as DWPose and OpenPose face intrinsic challenges in precisely identifying keypoints for each leg in videos recorded in lateral perspective when the legs alternate between front and back positions, stemming from their current technological limitations. Misidentification of leg keypoints can result in significant errors in feature extraction and consequently cause incorrect UPDRS classification. To address this, we developed a modification algorithm to correct misdetections of leg keypoints for each video segment. This algorithm analyzes the trajectory of the horizontal distance between the left and right ankles, as estimated by the skeleton extraction model, to correct keypoints. To eliminate potential errors arising from confusion between the left and right ankle keypoints during foot alternation, our algorithm implemented iterative adjustments to the curve trend on a per-frame basis. For each video frame, it evaluates two scenarios: one in which the model directly identifies the keypoints and another in which they are swapped. By selecting the scenario that maintains a smoother and more consistent motion trajectory based on the predicted curve and the second-order and third-order differences of the predicted curves, the algorithm can efficiently identify and rectify incorrect swaps. This algorithm iteratively updated the distance between the left and right ankles across all video frames to correct the confusion between them. This approach largely reduced the number of incorrect identifications of left and right ankles and refined motion trajectories in video frames. Consequently, it provided a more accurate representation of the ankle joint motion curve. Supplementary Fig. 1 demonstrates the algorithm’s effectiveness in improving the reliability of tracking key points. Furthermore, the detected keypoints for the occluded arms are unreliable when using DWPose or OpenPose, as they rely on statistical estimates when the limbs are occluded. These estimates are often similar to those of healthy individuals rather than patients with PD, leading to classification errors. To mitigate this, we set the unreliable keypoints for the occluded arms to zero in our model, focusing primarily on the motion of the arm nearest to the smartphone side.

Deep learning-based model

To accurately extract motion characteristics from gait videos recorded from both left- and right-lateral perspectives and efficiently fuse them to perform a comprehensive assessment of gait impairments, we developed a novel Siamese contrastive network architecture (Fig. 7), inspired by the model in ref. 56. This architecture can concurrently extract features from videos recorded in left- and right-lateral perspectives. By using a weight-sharing mechanism in feature extraction and a feature fusion strategy, the proposed Siamese network can not only efficiently combine all joints’ features, but also reflect the asymmetry of joint movements in spatiotemporal domains, ensuring an accurate prediction of disease severity. Note that interlimb asymmetry is typically specific to PD and often appears in its early stage2. Instead of using the heavy Transformer-based MotionBERT network57,58, we utilized a lightweight spatial-temporal graph convolutional network (ST-GCN)59 as the backbone of the architecture to guarantee high efficiency. Unlike our previous model27, which required both gait energy images and a complex convolutional neural network, our present model uses only skeleton data and eliminates the need for complex convolutional neural networks, leading to a significant reduction in computational resources. This enables convenient home-based online prediction of disease severity.

Skeleton data extracted from gait videos recorded from the left and right perspectives are fed into two identical backbone networks, B1 and B2, which share the same weights. G represents the spatial topology of the data, capturing the spatial dependencies among nodes. These dependencies are propagated through the network via graph convolution operations. Each backbone network extracts feature vectors, denoted as f1 and f2, which are subsequently concatenated into a unified vector, f. This composite vector is then processed through fully connected layers followed by a softmax layer, yielding a probabilistic distribution across three distinct classes. The right part shows the structure of the spatial-temporal graph convolutional (ST-GCN) network.

The model was trained using 558 video segments from 93 participants (Fig. 1). In addition, we enhanced the robustness of the model by further performing data augmentation to expand the effective size of the dataset60,61. Spatial data augmentation was carried out by randomly scaling and rotating coordinate values of all joints to introduce data variability. We did not perform temporal data augmentation due to the constraint of the patients’ zero gait velocity at the beginning of walking. To prevent overfitting, a 5-fold cross-validation strategy was implemented. We selected the five-fold cross-validation procedure to ensure both an efficient model training and an effective evaluation of model performance. Note that we split the folds at the patient level, ensuring that all data from a single patient was contained entirely within one fold and a given patient’s data never appeared in both the training and validation sets simultaneously in any iteration. The data augmentation was restricted to the training phase to avoid data leakage, ensuring that no augmentation occurred during the validation or independent test phases, thus maintaining the integrity of the validation/test data with the original data.

To evaluate the model’s performance in predicting disease severity, we conducted tests using an independent dataset comprising 150 video segments from 25 participants (Fig. 1). For each participant, six gait video segments were randomly paired with counterparts recorded from the opposite side, generating a pair of dual-perspective video inputs for the model. We utilized five models derived from the five-fold training during the evaluation. For each video segment, the majority vote among the outputs of five models was selected as the predicted result. Similarly, the majority vote of the predicted results for six video segments was chosen as the final predicted result for each participant. Evaluation metrics were calculated based on these final results of all participants in the test dataset (Table 2 and Fig. 2). Additionally, to evaluate the performance in discriminating the effect of medication on gait impairments, we performed the same evaluation for videos recorded during off- and on-medication states. It is noteworthy that the same model trained with the training dataset was used for discriminating medication response in gaits rather than retraining a new model.

Digital biomarker extraction

Before extracting motion makers, we identified the participant’s body parts with spatiotemporal features strongly correlating with disease severity by examining each joint’s contribution to the prediction of UPDRS scores in our model. Since two side-view video segments were used to predict PD severity, we calculated the joint contributions based on both videos. We proposed a dual maximum gradient-weighted class activation mapping (DMGrad-CAM) method based on the traditional Grad-CAM62, tailored for our Siamese contrastive network architecture. This method allows us to observe and assess the gait features in PD from two perspectives. We used the final spatiotemporal graph convolutional network (ST-GCN) layer as the target for the DMGrad-CAM analysis. To generate the DMGrad-CAM heatmap, we applied Grad-CAM to the model’s final layer, producing a spatiotemporal heatmap that assigns an importance score to each joint for every frame. After generating the Grad-CAM heatmaps for videos recorded from both left and right perspectives, we selected the joints with the maximum Grad-CAM heatmap for the utility of videos on both sides. By comparing the results from both perspectives, we calculated the normalized contribution ratio for each joint in both perspectives. We further used a sliding average filter with a window size of w (w = 5) to process the heatmap matrix and selected the maximum value of the filtered heatmap for each joint. For each participant, the joint contributions were estimated based on all three pairs of video segments by taking the average across them. These contributions were then normalized and aggregated across categories to assess their correlations with different levels of PD severity.

We extracted two types of motion markers associated with joints that contribute most significantly: traditional clinical markers such as arm swing amplitude, gait speed, and step length, and novel digital biomarkers indicative of the joint’s spatiotemporal movements, including linear velocity, linear acceleration, joint angles, and the standard deviation of joint angles. We calculated the means of these gait parameters and their variances across six video segments, revealing not only the average gait performance but also the gait variability associated with PD, such as slower walking speed or shorter step length over walking time. To transform pixel coordinates into real-world measurements, the forearm length was assumed to constitute a proportion p = 0.1608 of the total body height, hreal, according to the anthropometric analysis63. Utilizing the median pixel length, \({L}_{i}^{{\rm{pix}}}\), in the i-th video frame, the pixel-to-real-world scaling factor, s, was determined as

where le(i) and lw(i) are the 2D pixel coordinates of the elbow and wrist joints in the i-th frame, respectively.

Then, the pixel data l(i) was scaled into real-world coordinates as

where j(i) is the real-world 2D coordinates in the i-th frame.

Based on the calibrated coordinates, we can easily calculate the spatiotemporal motion markers. For the traditional clinical gait features, step length was defined as the maximum horizontal distance between the ankles, and arm swing amplitude as the maximum horizontal displacement between the wrist and hip. An inter-quartile range (IQR64) filter was applied to the traditional features to remove outliers before determining the maximum value. Finally, the mean and variance of all features were calculated across the video segments to quantify overall gait performance and variability.

Discrimination of medication effectiveness on gait impairment

To effectively discriminate the effect of medical interventions in gait impairments, we proposed a novel fine-granular assessment score (FGAS) by integrating the UPDRS scores predicted by the model along with their associated confidence levels. Medication outcomes (MO) in gait impairments can be predicted as

with

where Sc represents the FGAS. S1, S2, S3 denote the confidence levels for the predicted UPDRS scores 0, 1, and 2, respectively. The superscripts post and pre indicate post- and pre-medication states, respectively. The weights assigned to each confidence level, α1, α2, and α3, were set at 1, 2, and 3, respectively. δ is the threshold to determine the significance of changes in the gait impairments, which was established at 0.02 to efficiently identify the medication outcomes.

Benchmarking the consensus of the three experts on the medication outcomes, we calculated the agreement rates of the predicted medication outcomes using our model and the assessment results of each expert, along with a non-expert clinician. For all experts, the changed UPDRS scores, rated before and after medication, were first selected as the medication outcome evaluation for participants who experienced a change in their UPDRS scores. Subsequently, for participants without a UPDRS score change, the FGAS sub-score evaluations were used as the medication outcomes in gait impairments.

We evaluated the ability of extracted motion markers to characterize personalized medication responses. We statistically analyzed all motion markers extracted from modified skeleton data from 19 patients with PD in the test dataset (Table 1). We assessed the normality of the distributions of the values of each marker across 19 patients using the Shapiro–Wilk test. The independent samples t-test and the Kruskal–Wallis test were employed to analyze the differences in values of motion markers obtained between the off- and on-medication states for those with and without normal distribution, respectively. We compared the significant changes (p < 0.05) in motion markers to the consensus of experts on the medication outcomes in gait impairments for each participant, selecting the top three joints with markers showing the highest agreement rates. Finally, we performed a statistical analysis on the differences in all associated motion markers of the top three joints between the off- and on-medication states for all 19 patients.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Python version 3.8 (Python Software Foundation). Boxplots are shown with a central mark at the median, bottom, and top edges of the boxes at the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively, and whiskers extending to the most extreme points within 1.5 times the interquartile range. To assess the inter-group in participant characteristics such as gender, age, height and time since diagnosis across three groups with different UPDRS scores, two-sided χ2 tests were performed for genders and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for age, height and time since diagnosis. The Kruskal–Wallis test was performed to calculate the statistical significance of extracted traditional clinical motion markers among participants with varying disease stages. A two-sided t-test was conducted to analyze the statistical significance in the extracted motion markers with a normal distribution between off- and on-medication states, while the Kruskal–Wallis test was employed for markers without a normal distribution. Shapiro–Wilk test was used to validate the distribution of each motion marker. Spearman correlation coefficients were calculated to evaluate the correlations between extracted motion markers and UPDRS scores, as well as to compare the medication outcomes rated by the clinicians, the model, and the clinical motion markers. To investigate the sources of model error reflected in the confusion matrices, Fisher’s Exact Test was utilized to examine sex differences between accurately predicted and mismatched groups, and the Mann–Whitney U test was employed to assess age and height variations. Additionally, Fisher’s Exact Test was also applied to determine whether model errors were significantly associated with discrepancies among expert ratings. The mean and standard deviation of the Spearman correlation coefficients between the coordinates of body joints measured using the Vicon and the DWPose are shown in Supplementary Fig. 11.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data associated with this study are presented in the paper or the supplementary materials (Supplementary Information and Data 1). We are unable to provide the original dataset (i.e., gait videos) due to the patient data privacy policy. We provide a toy dataset, including the gait features extracted from the skeleton data and the features extracted using DMGrad-CAM, which are available at the Code Ocean capsule associated with the article (capsule number 7700825), enabling the reproduction of results based on these features. Code availability: The code for data preprocessing, model training, validation, testing, DMGrad-CAM calculation, and joint feature extraction is available at Code Ocean (capsule number 7700825). The developed online assessment system, Fast Assessment of Gait Impairments in Parkinson’s Disease (FAGI-PD), is available at https://gaitanalysis.simplaj.fun. A demonstration of this online system is provided in Supplementary Movie 1.

Code availability

The code for data preprocessing, model training, validation, testing, DMGrad-CAM calculation, and joint feature extraction is available at Code Ocean (capsule number 7700825). The developed online assessment system (Fast Assessment of Gait Impairments in Parkinson’s Disease, FAGI-PD) is available at gaitanalysis.simplaj.fun. A demonstration of this online system is provided in Supplementary Movie 1.

References

Aarsland, D. et al. Parkinson disease-associated cognitive impairment. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 7, 47 (2021).

Mirelman, A. et al. Gait impairments in Parkinson’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 18, 697–708 (2019).

Armstrong, M. J. & Okun, M. S. Diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson disease: a review. JAMA 323, 548–560 (2020).

Forte, R., Tocci, N. & De Vito, G. The impact of exercise intervention with rhythmic auditory stimulation to improve gait and mobility in Parkinson Disease: an umbrella review. Brain Sci. 11, 685 (2021).

Mao, Z. et al. Comparison of efficacy of deep brain stimulation of different targets in Parkinson’s disease: a network meta-analysis. Front. Aging Neurosci. 11, 23 (2019).

Demrozi, F., Bacchin, R., Tamburin, S., Cristani, M. & Pravadelli, G. Toward a wearable system for predicting freezing of gait in people affected by Parkinson’s disease. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 24, 2444–2451 (2019).

Sabo, A., Mehdizadeh, S., Iaboni, A. & Taati, B. Estimating parkinsonism severity in natural gait videos of older adults with dementia. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 26, 2288–2298 (2022).

Bloem, B. R. et al. M easurement instruments to assess posture, gait, and balance in p arkinson’s disease: Critique and recommendations. Mov. Disord. 31, 1342–1355 (2016).

Baron, E. I., Miller Koop, M., Streicher, M. C., Rosenfeldt, A. B. & Alberts, J. L. Altered kinematics of arm swing in Parkinson’s disease patients indicates declines in gait under dual-task conditions. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 48, 61–67 (2018).

Rochester, L., Galna, B., Lord, S. & Burn, D. The nature of dual-task interference during gait in incident Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci 265, 83–94 (2014).

Curtze, C., Nutt, J. G., Carlson-Kuhta, P., Mancini, M. & Horak, F. B. Levodopa is a double-edged sword for balance and gait in people with Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 30, 1361–1370 (2015).

Samotus, O., Parrent, A. & Jog, M. Spinal cord stimulation therapy for gait dysfunction in advanced Parkinson’s disease patients. Mov. Disord. 33, 783–792 (2018).

Schlick, C. et al. Visual cues combined with treadmill training to improve gait performance in Parkinson’s disease: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin. Rehabil. 30, 463–471 (2016).

Roiz, Rd. M. et al. Gait analysis comparing Parkinson’s disease with healthy elderly subjects. Arq. Neuro Psiquiatr. 68, 81–86 (2010).

Pachoulakis, I. & Kourmoulis, K. Building a gait analysis framework for Parkinson’s disease patients: motion capture and skeleton 3d representation. In 2014 International Conference on Telecommunications and Multimedia (TEMU), 220–225 (IEEE, 2014).

Pistacchi, M. et al. Gait analysis and clinical correlations in early Parkinson’s disease. Funct. Neurol. 32, 28–34 (2017).

Burq, M. et al. Virtual exam for Parkinson’s disease enables frequent and reliable remote measurements of motor function. NPJ Digit. Med. 5, 65 (2022).

Elm, J. J. et al. Feasibility and utility of a clinician dashboard from wearable and mobile application Parkinson’s disease data. NPJ Digit. Med. 2, 95 (2019).

Islam, M. S. et al. Using ai to measure Parkinson’s disease severity at home. NPJ Digit. Med. 6, 156 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. Artificial intelligence-enabled detection and assessment of Parkinson’s disease using nocturnal breathing signals. Nat. Med. 28, 2207–2215 (2022).

Zhan, A. et al. Using smartphones and machine learning to quantify Parkinson Disease severity: the mobile Parkinson Disease score. JAMA Neurol. 75, 876–880 (2018).

Morinan, G. et al. Computer vision quantification of whole-body parkinsonian bradykinesia using a large multi-site population. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 9, 10 (2023).