Abstract

This study comprehensively investigates the role of glycolysis in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) pathogenesis. Elevated glycolysis correlated significantly with poor prognosis. Bioinformatics identified HIF1A and MIF as key regulators and revealed two robust molecular subtypes: a high-glycolysis subtype (C1) associated with increased malignant cell proportion, activated oncogenic pathways, genomic instability, and inferior survival, and a low-glycolysis subtype (C2). These subtypes exhibited distinct drug sensitivities (C1 sensitive to panobinostat, MK-2206, 17-AAG; C2 sensitive to venetoclax) and predicted immunotherapy responses (C1 potentially benefiting more from anti-PD-1). An optimized 9-gene prognostic signature was developed using CoxBoost and StepCox algorithms, demonstrating accurate survival prediction across cohorts. Crucially, aberrant PKM2 overexpression was linked to imatinib (IM) resistance. A vivo-morpholino antisense oligomer (vMO) targeting the PKM exon 9-10 splice junction effectively converted PKM splicing from PKM2 to PKM1, inhibiting leukemia growth and reversing IM resistance in vitro and in vivo. To mitigate vMO toxicity, IL3-Lamp2b-engineered exosomes were developed, demonstrating efficient vMO loading, targeted delivery to leukemia cells, potent PKM splicing correction, significant IM resistance reversal, and minimal stromal cell toxicity. This work defines glycolysis-based AML subtypes with therapeutic implications and establishes engineered exosome-delivered vMO as a promising strategy to overcome drug resistance in hyper-glycolytic myeloid leukemia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is a hematological tumor that originates from hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells1. It is characterized by impaired differentiation and malignant proliferation of myeloid progenitor cells, resulting in anemia, infection, bleeding, and invasion of extramedullary organs2. AML is the most prevalent form of acute leukemia and has a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 30%3. The treatment options for AML include initial induction therapy, postremission therapy, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and immunotherapy4. Despite significant advancements in these treatment modalities, which have improved complete response rates and 5-year survival rates for AML patients, approximately three-quarters of those who achieve a complete response will eventually experience relapse because chemotherapy resistance is a key factor contributing to AML recurrence5,6. Therefore, exploring novel prognostic markers for AML and new targets for drug resistance therapy is highly valuable.

Many interacting factors contribute to the emergence of drug resistance, including the inhibition of apoptotic cell death, abnormal activation of intracellular survival signaling pathways, changes in miRNA expression associated with drug resistance, metabolic abnormalities, and alterations in multidrug resistance enzyme kinetics7,8. The malignant growth of tumor cells necessitates a rapid energy supply and significantly depends on glucose, along with enhanced glycolytic metabolic activity9. Even under aerobic conditions, this pathway remains active by converting glucose into lactic acid and ATP, a phenomenon known as the “Warburg effect”10. Increased glucose uptake and glycolytic activity are pivotal factors that contribute to the emergence and progression of malignant phenotypes in tumors11. Moreover, they play crucial roles in the development of drug resistance and tumor recurrence12. The close association between glucose metabolism and chemotherapy resistance has garnered increasing attention in leukemia research13. For example, targeting glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) can overcome cytarabine resistance in AML14, whereas inhibiting hexokinase 2 (HK2) can effectively inhibit adriamycin resistance15. Additionally, key glycolytic enzymes, such as phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK-1)16, pyruvate kinase (PK)17, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)18, have been implicated in leukemia drug resistance by enhancing glycolytic activity. Therefore, the inhibition of glycolysis may serve as an effective approach to inhibit chemotherapy resistance.

In this study, we first aimed to systematically define glycolysis-driven molecular subtypes in AML using multiomics data and machine learning, and to explore their distinct clinical, immune, and therapeutic features. We hypothesized that the aggressive glycolytic subtype would be characterized by specific key drivers. Our analysis indeed pinpointed PKM as a central player. This led to our second hypothesis: that targeted modulation of PKM splicing, shifting the balance from the pro-tumorigenic PKM2 isoform to the tumor-suppressive PKM1 isoform, could overcome drug resistance. To experimentally validate the functional role of PKM in a model that recapitulates the transition from a therapy-sensitive to a therapy-resistant, hyper-glycolytic state, we turned to chronic myeloid leukemia (CML). The progression of CML from the treatable chronic phase (CP) to the aggressive, therapy-resistant blast crisis (BC) is a classic paradigm of leukemic evolution. BC shares numerous clinical and molecular features with high-risk AML, including glycolytic reprogramming. We reasoned that the CP-CML and BC-CML states would respectively model the low-glycolysis (C2) and high-glycolysis (C1) AML subtypes we identified, providing a powerful isogenic system to test our hypothesis. Finally, to translate this strategy while mitigating potential toxicity, we proposed a novel therapeutic approach using IL3-receptor-targeted exosomes (IL3L-Exos) for the efficient and specific delivery of a PKM-splicing vivo-morpholino (vMO). This work establishes a comprehensive framework from glycolytic subtyping to a targeted nanotherapeutic intervention for drug-resistant myeloid leukemia.

Results

Myeloid leukemia is associated with increased glycolytic activity and potential regulatory mechanisms

We initially compared the glycolytic activity of diverse blood tumors and observed that the AML, CML, and MDS samples presented higher glycolytic scores than did the ALL and CLL samples through GSVA (Fig. 1A, B). tSNE analysis revealed that the expression of GRGs effectively distinguished five distinct types of blood tumors (Fig. 1C), highlighting the heterogeneity of glycolytic molecules across different blood tumor subtypes. Notably, clinical data were available for the AML and MDS samples. Subsequent survival analysis revealed a significantly worse prognosis for AML patients in the high-glycolysis score group than for those in the low-glycolysis score group, whereas no significant difference was observed in MDS patients (Fig. 1D, E). Consequently, our focus shifted toward the analysis of glycolytic characteristics, specifically in AML patients. The GSE116256 cohort included single-cell transcriptome sequencing data from 21 subtypes of AML patients, including six types of malignant cells: HSC-like, Prog-like, GMP-like, ProMono-like, Mono-like, and cDC-like cells (Fig. 1F, G). Compared with their normal counterparts, markedly elevated glycolytic scores were detected in HSC-like, GMP-like, and ProMono-like cells (Fig. 1H, I). Furthermore, all the malignant cell types presented higher overall glycolysis scores than did all the normal cells.

Heatmap (A) and boxplot (B) showing differences in glycolysis scores among the five hematologic tumors. C The tSNE algorithm distinguished five types of blood tumors on the basis of the expression of GRGs. D, E Prognostic analysis of the AML and MDS cohorts with different glycolysis score groups. F Cell classification characteristics observed in AML single-cell datasets. G The distribution of glycolysis scores across all types of cells is shown in the AML single-cell data. H Boxplot highlighting significant differences in glycolysis scores among various cell types. I Notable discrepancies exist in the distribution of glycolysis scores between malignant AML cells and normal cells.

To identify key GRGs, we discovered that 16 GRGs were aberrantly expressed on the basis of the results of differential expression analysis via single-cell sequencing (Fig. 2A). PGK1, ALDOA, ENO1, TPI1, PKM, LDHA, PGAM1, CITED2, VCAN, HSPA5, MIF, STMN1, TALDO1, TXN, and PPIA were significantly upregulated in AML cells, whereas CXCR4 was significantly downregulated (Fig. 2B). These findings suggest that the overexpression of these genes may contribute to the enhanced glycolytic activity observed in AML cells. Fig. 2C shows the chromosomal locations of the GRGs. To identify the potential transcription factors involved in regulating the expression of these key GRGs, we performed motif analysis via the i-cisTarget platform. Notably, the HIF-1α binding motif was highly enriched in these GRGs (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, HIF-1α expression was significantly elevated in malignant AML cells compared with normal cells (Fig. S1E). Correlation analysis revealed a significant positive correlation between HIF-1α and most key GRGs, suggesting that HIF-1α may serve as an important upstream regulator of glycolysis in AML (Fig. 2F and S1). Protein molecules associated with glycolysis may also play a role in the tumor microenvironment (TME). Through cell communication analysis, MIF-(CD74+CXCR4) and MIF-(CD74+CD44) were identified as the most active ligand‒receptor pairs (L‒R pairs) (Fig. 2G). Since MIF is a crucial gene involved in glycolysis, it might play an important role in TME regulation in AML. Among the various cell types, the GMP-like and Prog-like populations are considered the major sources of MIF signals and target other cell types (Fig. 2H–J). Notably, the possibility of a GMP-like population transmitting information through exocrine ligands is more evident (Fig. 2K), which is further supported by the significantly upregulated expression of MIF specifically observed in GMP-like cells (Fig. 2L).

A Intersection analysis of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and glycolysis-related genes (GRGs) in AML malignant cells compared with normal cells. B Expression profiles of 16 differentially expressed GRGs in a single-cell dataset. C Chromosomal locations of the 16 differentially expressed GRGs. D Identification of 16 transcription factors that exhibit differential enrichment of GRG binding sites. The i-cisTarget motif platform was utilized to analyze normalized enrichment scores (NESs). E Comparison of HIF1A expression between malignant and normal cells in AML single-cell datasets. F Correlation analysis between HIF1A and the expression levels of the 16 GRGs. G Visualization of intercellular ligand‒receptor pairs in single-cell data, with color indicating the likelihood and magnitude representing the significance of cell communication. H–J Communication network depicting MIF signaling interactions among distinct cell groups. The color consistency between lines and squares indicates source‒target relationships, where squares represent source cells, while line ends indicate target cells. K Heatmap displaying the dominant senders, receivers, mediators, and influencers involved in MIF signaling inferred from network centrality scores within the tumor context. L Expression characteristics of molecules within the MIF pathway across different cell groups.

Molecular characterization of key GRGs and identification of glycolytic molecular subtypes

We further analyzed the molecular characteristics of the key GRGs via multiomics data analysis. The frequency of somatic mutations in GRGs was relatively low, with only one out of 134 AML patients exhibiting simultaneous mutations in PKM, TPI1, and VCAN (Fig. S2A). Among the GRGs, only VCAN presented a copy number deletion frequency of approximately 2%, whereas the other GRGs presented lower frequencies of copy number variations (Fig. S2B). These findings suggest that genomic changes have minimal effects on GRG expression and that their regulation by transcription factors, such as HIF-1α, may be the primary reason for this phenomenon. We subsequently investigated the correlation between GRG expression and prognosis via data from the TCGA dataset. Our analysis revealed a significant positive correlation between the expression of different GRGs, indicating potential synergistic effects (Fig. S2C). Moreover, most GRGs were identified as poor prognostic factors for AML (hazard ratio >1), particularly PGK1, ALDOA, ENO1, TPI1, PKM, PGAM1, and TALDO1, which exhibited significant correlations (P < 0.05) (Fig. S2D). These prognostic GRGs may play crucial roles in the development of AML.

Molecular typing plays a vital role in personalized disease treatment strategies. On the basis of these prognostic GRGs, we performed consensus cluster analysis and identified two distinct glycolytic subtypes (Clusters C1 and C2) (Fig. S2E). PCA confirmed the reliability of the clustering results (Fig. S2F). Interestingly, the expression levels of the GRGs were significantly greater in the C1 subtype than in the C2 subtype (Fig. S2G). Additionally, survival analysis demonstrated that patients with the C1 subtype had a significantly worse prognosis than those with the C2 subtype did (Fig. S3H). Furthermore, the glycolytic activity score was significantly greater in the C1 subtype (Fig. S3A). These findings suggest that an increase in glycolytic activity may aggravate the malignant progression of C1 subtype tumors, thereby resulting in poor patient prognosis.

There were significant differences in the immune microenvironment and biological characteristics between glycolysis subtypes

We further assessed the disparities in immune and molecular biological characteristics between molecular subtypes. Through deconvolution, we computed the relative proportion of AML blood cells in each sample of the TCGA-LAML cohort. Differential analysis revealed a significantly greater proportion of malignant AML cells in the C1 subtype than in the C2 subtype (Fig. S3B). Additionally, the C2 subtype exhibited a greater abundance of immune effector cells, such as T and B cells, which may contribute to a more favorable prognosis (Fig. S3C). However, a higher TIDE score in the C2 subtype could be associated with elevated levels of immune evasion by tumor cells, leading to impaired immune cell functionality and an inability to halt cancer progression (Fig. S3D). Immunomodulators (IMs), including numerous IM agonists and antagonists currently undergoing clinical oncology evaluation, play crucial roles in cancer immunotherapy. Understanding their expression patterns across different molecular subtypes is valuable for comprehensively assessing the immune characteristics of patients (Fig. S3E). Notably, the most significant variation in expression between subtypes was observed in the antigen-presenting gene family, all of which presented higher levels of expression in the C1 subtype, along with ITGB2, TLR4, and C10orf54 (Fig. S3F). Moreover, DNA methylation levels were inversely correlated with the expression levels of various IM genes, such as HLA-DPA1, TNF, and HAVCR2 (Fig. S3F), indicating epigenetic silencing effects. Enrichment analysis also revealed increased activity scores for most cancer-related pathways, such as metabolism, proliferation, and signaling, within the C1 subtype (Fig. S3G). We conducted somatic mutation and copy number variation analyses to explore genomic trait discrepancies between the two MSs. Gene copy number variation was observed in nearly all chromosomes in both MSs. The frequency of copy number deletions on chromosomes 5 and 12 was significantly greater in the C1 subtype than in the C2 subtype (Fig. S3H). Somatic mutation analysis revealed that the tumor mutation burden was significantly greater in the C2 subtype, whereas the C1 subtype exhibited a greater proportion of samples with alterations, particularly a significantly elevated occurrence of NPM1 mutations characterized by frameshift insertion mutations (Fig. S3I–K). On the basis of these genomic changes, it can be speculated that the unfavorable prognosis associated with the C1 subtype may be influenced by genomic alterations.

Validation of molecular subtypes and determination at the single-cell level

We conducted a comprehensive analysis of the disparities in gene expression between the two molecular subtypes, leading to the identification of 336 differentially expressed genes (DEGs). Most of these DEGs were upregulated in subtype C1 (logFC > 1, adjusted P < 0.05), with PKM and PGAM1 displaying particularly significant differences, indicating their potential involvement in driving the aggressive phenotype associated with this subtype (Fig. S4A). Subsequent GO annotation analysis revealed that these DEGs were predominantly enriched in immune regulatory processes, such as cell activation involved in the immune response and positive regulation of cytokine production; cellular components, including the secretory granule membrane and endocytic vesicle; and molecular functions associated with immune receptor activity (Fig. S4B). The GSEA results revealed significant enrichment of immune pathways, including Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis, necroptosis, neutrophil extracellular trap formation, the NOD-like receptor signaling pathway, and the Toll-like receptor signaling pathway, in the C1 subtype (Fig. S4C). Through consensus cluster analysis of these DEGs, we identified two distinct gene subtypes, namely geneCluster A and geneCluster B (Fig. S4D). Notably, geneCluster A presented a significantly higher glycolysis score than did geneCluster B (Fig. S4E). Prognostic analysis further revealed that patients belonging to genCluster A had a worse prognosis (Fig. S4F). In terms of clinical characteristics, patients in geneCluster A presented with increased age and peripheral white blood cell (WBC) counts (Fig. S4G). Interestingly, subtype C1 predominantly resides within the confines of geneCluster A and has a relatively high mortality rate, whereas subtype C2 is associated primarily with geneCluster B and has a relatively high survival rate (Fig. S4H). Considering the consistent disparities in glycolysis scores observed between these subtypes, it is reasonable to assert that two distinct molecular subtypes related to glycolysis exist in AML patients.

To integrate the scRNA-seq and bulk data, 35 samples from the GSE116256 scRNA-seq dataset were integrated into bulk data on the basis of the average gene expression values. Through cluster analysis, these patients were further classified into two distinct molecular subtypes (Fig. S4I). The C1 subtype exhibited significant upregulation of both the glycolysis score and GRG expression (Fig. S4J, K). Additionally, we observed that all six types of AML malignant cells accounted for a greater proportion of the C1 subtype, whereas the C2 subtype contained significantly more T cells (Fig. S4L, M). These findings provide an additional characterization of glycolysis-related molecular subtypes at the single-cell level.

Prediction of the sensitivity of different molecular subtypes to chemotherapy and immunotherapy

We further assessed the sensitivity of distinct molecular subtypes to chemotherapy and immunotherapy. The Beat AML cohort provided data on patients’ isolated AML cell response to drug therapy; thus, our analysis focused on this cohort. Consensus clustering also stratified the Beat AML cohort into two distinct molecular subtypes (Fig. S5A), which is consistent with other cohorts in which C1 patients presented significantly higher GRG expression levels and glycolysis scores than C2 patients did (Fig. S5B, C). On the basis of a significance level of P < 0.001, we identified a group of drugs that displayed significant sensitivity differences between the C1 and C2 subtypes; specifically, C1 showed greater sensitivity toward panobinostat, MK-2206, 17-AAG (tanespimycin), and cediranib (AZD2171) (Fig. S5D), whereas the C2 subtype demonstrated increased sensitivity toward venetoclax, NF-kB activation inhibitors, GSK-1838705A, PHA-665752, lapatinib, neratinib (HKI-272), and NVP-TAE684 (Fig. S5E). With respect to immunotherapy response prediction, both the TCGA cohort and the Beat AML cohort indicated that patients with the C1 subtype exhibited better therapeutic responses to PD-1 therapy, with a greater proportion of responders (Fig. S5F, G). These findings provide valuable insights into personalized treatment strategies targeting different glycolytic subtypes of AML.

Collectively, our bioinformatic analyses established two robust glycolytic subtypes of AML with profound differences in prognosis, tumor microenvironment, and therapeutic vulnerabilities. The consistent identification of PKM as a top differentially expressed gene in the poor-prognosis C1 subtype, coupled with its well-established role in cancer metabolism, led us to functionally investigate its role in leukemia drug resistance.

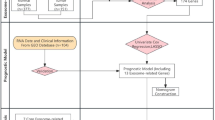

Development and predictive value analysis of glycolysis-related signatures

We used all the GRGs to construct a glycolysis-related signature and elucidate its prognostic value. Univariate Cox regression analysis was used to identify 16 prognostic GRGs, followed by the construction of prognostic risk score models on the basis of 118 combinations of 10 machine learning algorithms (Fig. S6A). The C-index of each model was calculated in ten AML cohorts to evaluate its prognostic ability. Among all the validation cohorts, we selected the model combination with the highest average C-index, namely, the algorithm composed of CoxBoost and StepCox (forward), which consisted of nine GRGs (Fig. S6B). Risk scores were computed for each sample across all cohorts, and patients were categorized into high- and low-risk groups using optimal cutoff values (Fig. S6C). In the analytical cohort (TCGA), a significantly greater number of patients in the high-risk group died (Fig. S6D), and the overall prognosis of these individuals was worse (Fig. S6E). ROC curve analysis demonstrated that in the analytical cohort, the risk score model accurately predicted survival rates at 1-, 3-, and 5-year intervals, with AUC values of 0.770, 0.786, and 0.847, respectively (Fig. S6F). Independent prognostic analysis revealed that this risk score model possessed significant independent prognostic value according to both univariate and multivariate Cox analyses (P < 0.001) (Fig. S6G, H). In two major international cohorts (Beat AML and HOVON), outcomes were notably poorer among individuals classified as high risk by our scoring system (Fig. S6I, J), and ROC curve analysis and independent prognostic analysis further confirmed its predictive accuracy as an independent prognosticator (Figs. S6K, L and S7A). Similar findings were observed across seven additional cohorts, in which patients with high-risk scores consistently exhibited worse clinical outcomes (Fig. S7B–I).

Finally, we integrated clinicopathological factors that demonstrated significant associations with the prognosis of AML patients via univariate Cox analysis to develop a nomogram for predicting overall survival (OS) in AML patients (Fig. S7J). The accuracy of the nomogram’s predictions was validated through calibration curves generated from data from the TCGA, HOVON, and Beat AML cohorts (Fig. S7K).

Targeted regulation of PKM alternative splicing represents a potentially effective therapeutic strategy for addressing drug resistance in myeloid leukemia

In the above studies, we observed a significant association between PKM and poor prognosis in patients with AML. Additionally, we found that the C1 subtype exhibited the most significant upregulation of this gene. To functionally investigate the role of PKM in a disease context mirroring the progression from our low-glycolysis C2 subtype to the high-glycolysis, drug-resistant C1 subtype, we utilized a model of CML. We analyzed clinical samples and employed the imatinib-sensitive K562 cell line (modeling CML-CP) and its isogenic, imatinib-resistant counterpart K562/G01 (modeling CML-BC). We hypothesized that the resistant, BC-like state would be associated with a PKM2-dominant profile, analogous to our C1 AML subtype. Therefore, our focus shifted toward investigating its role in CML progression. PKM consists of 12 exons and gives rise to two splice products: PKM1 and PKM2. Notably, these splice variants are mutually exclusive, with exon 9 being present only in PKM1, whereas exon 10 is exclusively included in PKM219. Clinical sample analysis revealed that the mRNA and protein expression levels of PKM1 in samples from IM-resistant patients were lower than those in the normal control group and the sensitive group, while the expression level of PKM2 was significantly elevated (Fig. 3A, B). Further immunohistochemical detection of bone marrow smears from CML patients revealed that the protein expression level of PKM2 in resistant patients was significantly greater than that in sensitive patients (Fig. 3C). The multicolor tissue immunofluorescence results confirmed that PKM was expressed mainly as PKM2 in CML-resistant patients, whereas PKM1 was expressed mainly in sensitive patients (Fig. 3D). In CML and AML cell lines, RT‒qPCR revealed that the expression level of PKM2 was the highest in the IM-resistant CML cell line K562/G01 (Fig. 3E). Western blot analysis of the CML IM-sensitive cell lines KCL-22 and K562 and the IM-resistant cell line K562/G01 revealed that the expression level of PKM2 was the highest in K562/G01 cells (Fig. 3F), suggesting that PKM2 may play an important role in CML resistance. PKM2 is a crucial glycolytic enzyme that confers metabolic advantages for tumor progression20. Suppression of PKM2 induced apoptosis both in vivo and in vitro21. Moreover, PKM1 exhibits tumor suppressor activity22, and substituting PKM2 with PKM1 in cancer cells inhibits cell proliferation and retards xenograft tumor formation in nude mice23. These findings suggest that the downregulation of PKM2 and upregulation of PKM1 may represent a particularly effective therapeutic strategy for cancer treatment.

A RT‒qPCR was used to detect the expression of PKM1 and PKM2 mRNAs in PBMCs from normal individuals, CML IM-sensitive patients, and CML IM-resistant patients. B Western blotting was used to detect the expression of PKM2 in PBMCs from CML IM-sensitive patients and CML IM-resistant patients. C Immunohistochemistry was used to detect the expression of PKM in bone marrow sections from CML patients. D Tissue immunofluorescence was used to detect the expression of PKM1 and PKM2 in bone marrow sections from CML patients; red fluorescence represents the PKM1 protein, and green fluorescence represents the PKM2 protein. E Expression of PKM2 mRNA in CML and AML cell lines. F Expression of the PKM2 protein in CML cell lines. G A diagram depicting alternative splicing of the PKM gene and the binding location of vMO. H Transfection efficiency was assessed by flow cytometry after treating K562/G01 cells with various concentrations (2, 4, 6, 8, 10, or 12 μmol/l) of vMO for 48 h. I Flow cytometry was used to detect the fluorescence intensity in K562/G01 cells treated with 10 μmol/l vMO for 48 h. J, K After treatment with a concentration of 10 μmol/l vMO, RT‒qPCR was used for mRNA expression analysis to reveal changes in PKM2 levels, while western blotting was used for protein expression analysis to assess alterations in both PKM1 and PKM2 levels. L, M Effect of vMO on the imatinib resistance of K562/G01 cells. RS-vMO: random sequence vMO.

We developed a targeted PKM splicing strategy using vMO to convert PKM2 into PKM1 (Fig. 3G). Flow cytometry analysis revealed that the fluorescence intensity in vMO-transfected K562/G01 cells was the highest at 48 h posttransfection (Fig. 3H). Different concentrations of vMO were transfected into K562/G01 cells for 48 h, and among the concentrations ranging from 2 to 12 μmol/L, the transfection efficiency was the highest at 10 μmol/L after 48 h (Fig. 3I). Compared with the random sequence vMO (RS-vMO) group and the untreated control group, treatment with 10 μmol/l vMO significantly reduced PKM2 expression while increasing PKM1 expression (Fig. 3J, K). Notably, vMO effectively reduced the IC50 value of IM in K562/G01 cells. (Fig. 3L, M).

vMO inhibits the growth of myeloid leukemia cells and reduces drug resistance

To further elucidate the potential of vMO in augmenting the cytotoxic effects of IM on K562 and K562/G01 cells, both cell lines were cocultured with IM, vMO, or IM+vMO for 48 h. Notably, treatment with IM+vMO effectively downregulated PKM2 expression and upregulated PKM1 expression in both K562 and K562/G01 cells (Fig. 4A, F). Furthermore, compared with the other experimental groups, the combined treatment with IM and vMO resulted in a significantly greater ability to induce G1 phase arrest in the cell cycle (Fig. 4B, C, G, H). Notably, vMO alone had an apoptotic effect; however, when vMO was combined with IM, this proapoptotic effect was further enhanced (Fig. 4D, E, I, J). Combined treatment also effectively suppressed the activity of both K562 and K562/G01 cells (Fig. 4K, L). Consequently, these findings collectively validate the growth-inhibitory properties of vMO against myeloid leukemia cells while concurrently reducing drug resistance.

A–E Expression levels of the PKM1 and PKM2 proteins (A), the cell cycle (B, C), apoptosis rates (D, E), and cell activity (K) were evaluated in K562 cells following transfection with IM (0.2 μmol/l), vMO (10 μmol/l), or a combination of both drugs. F–J Expression levels of the PKM1 and PKM2 proteins (F), the cell cycle (G, H), apoptosis rates (I, J), and cell activity (L) were assessed in K562/G01 cells after transfection with IM (2 μmol/l), vMO (10 μmol/l), or a combination of both drugs.

The therapeutic efficacy and resistance-reversing potential of vMO were validated in a xenograft model

To assess the therapeutic effects of vMO in vivo and its potential to enhance IM activity, a K562/G01 cell xenograft model was established. Following successful cell inoculation, the mice were treated with saline, IM, vMO, or a combination of both drugs. Compared with those receiving low-dose IM, mice receiving high-dose IM presented smaller tumor volumes (Fig. 5A, B), indicating that IM can inhibit tumor growth in a dose-dependent manner. Interestingly, compared with RS-vMO treatment, treatment with vMO alone also significantly reduced the tumor volume (Fig. 5A, B). Notably, when the vMO was combined with the IM, either intratumoral or intravenous injection of the vMO resulted in a further reduction in tumor volume (Fig. 5A, B). Hematoxylin‒eosin (HE) staining revealed a loose distribution of tumor cells and increased necrotic areas after combined treatment with IM and vMO, confirming the superior efficacy of this drug combination (Fig. 5C). Additionally, the Ki-67 signal intensity was weak after treatment (Fig. 5D), suggesting slower proliferation of the cells. Consistent with the findings from the cell experiments, the PKM2 expression levels were significantly decreased following the combined treatment (Fig. 5E, F). Notably, at moderate concentrations (100 μmol/l) of IM, intravenous injection of vMO had inhibitory effects similar to those of intratumoral injection (Fig. S8A–C). In conclusion, our study demonstrated that leukemia xenograft models are more responsive to IM treatment in the presence of vMO.

A, B Tumor volume was measured in CML xenograft models for each treatment group, with four mice per group. C Hematoxylin‒eosin staining of tumor sections revealed distinct local features among the treatment groups. D Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated variations in Ki-67 levels across the different treatment groups. E, F The protein expression levels of PKM1 and PKM2, as well as their ratios, were assessed within each treatment group. IV: intravenous administration.

Construction and identification of engineered exosomes

To better verify the biosafety of vMO, we found that the cell viability of both the RS-vMO group and the PKM2-vMO group was severely impaired after adding vMO to HS-5 bone marrow stromal cells (Fig. 6A). This finding indicates that if vMO is directly added to the blood microenvironment without targeting, it is likely to affect the physiological functions of normal cells. Therefore, identifying a method that can transport vMO, target CML cells, and effectively encapsulate it to reduce its toxicity is highly important for the application of vMO and the treatment of CML.

A The effect of vMO on the viability of HS-5 cells. B Schematic diagram of the Pinco plasmid containing IL3-Lamp2b. C Fluorescence image of HEK-293T cells after lentivirus transfection. D RT-qPCR detection of Lamp2b mRNA expression in HEK-293T cells after lentivirus transfection. E Western blot detection of 6*HIS tag protein expression in HEK-293T cells after lentivirus transfection. F Electron microscopy analysis of NC-Exos and IL3L-Exos. G Nanoparticle tracking analysis of NC-Exos and IL3L-Exos. H Western blot detection of exosome-positive markers, negative markers, and 6*HIS tag protein expression. I, J Confocal microscopy observation of fluorescence in K562/G01 cells treated with 20 µg/ml HEK-293T-derived exosomes for 12 h.

Exosomes are novel nanoscale gene delivery vectors that are safe and efficient, can penetrate biological barriers, and have good biocompatibility24. They have great application potential in the delivery of nucleic acid drugs25. Exosomes have a nanoscale membrane vesicle structure derived from the fusion of intracellular multivesicular bodies with the plasma membrane and are secreted outside the cell. This nanoscale membrane vesicle structure exhibits a phospholipid bilayer-coated sac-like morphology, which can effectively combine with vMO, thereby enabling its effective loading. In addition, the interleukin-3 receptor (IL3-R) is overexpressed in CML and AML cells but is expressed at low levels or not at all in normal hematopoietic stem cells26,27,28. These findings indicate that IL3-R can be used as a receptor target for certain targeted drugs. Daniele Bellavia et al. demonstrated that engineered exosomes expressing interleukin-3 and lysosome-associated membrane protein 2b fusion protein (IL3-Lamp2b, IL3L) can load imatinib or BCR-ABL siRNA and target CML cells in vitro and in vivo, inhibiting the malignant proliferation of CML cells29. Therefore, we constructed a lentivirus expressing IL3L and used it for the preparation of engineered exosomes. Moreover, we attempted to load PKM2-vMO into exosomes with an IL3L membrane protein via an exosome nucleic acid loading kit to verify its feasibility and functional effect.

We constructed a plasmid containing the recombinant human Lamp2b gene and the human interleukin-3 gene fragment fusion. A 6*HIS tag was subsequently added to the C-terminus of the protein (Fig. 6B). Fluorescence confirmed the successful transfection of the lentivirus into HEK-293T cells (Fig. 6C). RT‒qPCR and Western blot verification confirmed the increased expression of the Lamp2b gene (Fig. 6D, E); the 6*HIS tag as a tag protein was expressed in cells transfected with the IL3L lentivirus but not in cells transfected with the blank control virus or wild-type cells, indicating that the IL3‒Lamp2b fusion gene was successfully transferred and expressed in the cells. We successfully constructed tool cells, that is, engineered HEK-293T cells expressing IL3L.

The engineered exosomes expressing IL3L (IL3L-Exos) and control exosomes (NC-Exos) secreted by HEK-293T cells were extracted through a multistep ultracentrifugation method. The extracted exosomes were analyzed and identified via electron microscopy. As shown in Fig. 6F, both groups of exosomes presented a typical cup-shaped/disk-shaped morphology, had a complete lipid bilayer membrane structure, the particle size distribution was within the range of 30–200 nm, and gene modification did not cause significant morphological changes. As shown in Fig. 6G, nanoparticle size analysis further confirmed that the average particle size of the NC-Exo group was 148.8 nm, with a concentration of 1.8 × 1011 particles/mL; the average particle size of the IL3L-Exo group was 147.9 nm, with a concentration of 2.8 × 1011 particles/mL, and the particle size distributions of the two groups were basically consistent. Western blot analysis (Fig. 6H) revealed that exosome marker proteins such as Alix, TSG101, and CD81 were stably expressed in the exosomes from both groups, whereas the endoplasmic reticulum protein CALNEXI, a negative marker for exosomes, was not expressed on the exosomes. This confirmed that engineering modification did not affect the basic biological characteristics of exosomes; in addition, exosomes expressing IL3L were also capable of expressing 6*HIS tag-labeled proteins.

Exosome uptake experiments and targeting verification

To determine whether the exosomes produced by the HEK-293T cells (either expressing IL3L or not expressing IL3L) were taken up by the K562/G01 cells, the exosomes labeled with the lipophilic dye PKH26 were cocultured with the K562/G01 cells at a concentration of 20 µg/ml in a 37 °C, 5% CO2 incubator for 12 h Confocal microscopy images revealed that the exosomes were successfully taken up by the cells (Fig. 6I, J); compared with cells treated with NC-Exos, cells treated with IL3L-Exos presented significantly greater fluorescence intensity, indicating that the cells treated with exosomes took up more exosomes within the same time period, and the difference was significant.

To confirm that engineered exosomes with targeting ability could effectively target leukemia cells within a unit of time, K562/G01 cells, HS-5 cells, and BT-549 breast cancer cells were cocultured with 20 µg/ml lipophilic dye PKH26-labeled exosomes at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 6, 12, or 24 h; one group of K562/G01 cells was cocultured with NC-Exos; and the other three groups of K562/G01 cells, HS-5 cells, and BT-549 cells were cocultured with IL3L-Exos. As shown in Fig. S9A, B, compared with K562/G01 cells treated with NC-Exos, K562/G01 cells treated with IL3L-Exos presented significantly greater fluorescence intensity at 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h, indicating that they took up more exosomes; at the same time, compared with HS-5 cells and BT-549 cells treated with IL3L-Exos, K562/G01 cells treated with IL3L-Exos, owing to their specific IL3-R, also took up more exosomes at 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h, showing significantly greater fluorescence intensity.

vMO-loaded engineered IL3-Lamp2b exosomes

First, we coincubated 2 µl, 4 µl, 8 µl, and 10 µl of vMO at a concentration of 1 mM with engineered exosomes via the ExoLoad® nucleic acid loading kit from Enzogenetix to obtain vMO-loaded engineered exosomes. These solutions were then added to K562/G01 cells and coincubated at 37 °C with 5% CO2 in saturated humidity for 48 h. RT‒qPCR and Western blotting verified that the engineered exosomes loaded with 10 µl of vMO (1 mM) were the most effective at splicing the PKM gene (Fig. 7A, B), promoting the generation of PKM1 and inhibiting the generation of PKM2. Therefore, we used 10 µl of vMO (1 mM) for subsequent experiments. Flow cytometry was used to detect the fluorescence intensity of the cells. The percentages of positive control exosomes loaded with RS-vMO, IL3L exosomes loaded with RS-vMO, and IL3L exosomes loaded with PKM2-vMO after cellular uptake were 95.5%, 95.2%, and 97.7%, respectively (Fig. 7C). Confocal microscopy confirmed that the IL3L-engineered exosomes loaded with PKM2-vMO were successfully taken up by K562/G01 cells, with overlapping green fluorescence from vMO-FITC and red fluorescence from PKH26-labeled exosome membranes observed intracellularly (Fig. 7D).

A, B RT-qPCR and Western blot detection of PKM1 and PKM2 mRNA and protein expression in K562/G01 cells cocultured with engineered exosomes loaded with different concentrations of vMO. C Flow cytometry verification of fluorescence expression after the uptake of engineered exosomes loaded with vMO by K562/G01 cells. D Confocal microscopy observation of the uptake of engineered exosomes loaded with vMO by K562/G01 cells.

The engineered exosomes loaded with 10 µl of 1 mM vMO were subsequently cocultured with K562/G01 cells, and the results were compared with those of the other groups. As shown in Fig. 8A, B, both the exosome group loaded with PKM2-vMO (PKM2-vMO Exos) and the direct PKM2-vMO treatment group effectively increased the expression of PKM1 and decreased the expression of PKM2 through selective splicing. However, the IL3L-engineered exosome group loaded with PKM2-vMO (IL3L-PKM2-vMO Exos) was more effective at influencing the expression of PKM than the PKM2-vMO Exos group was; that is, it most effectively increased the expression of PKM1 and decreased the expression of PKM2. Moreover, the protein expression of the proapoptotic gene BAX in the IL3L-PKM2-vMO Exos group increased the most significantly, whereas the protein expression of the antiapoptotic gene BCL-2 decreased the most significantly. This finding also indicates that the addition of IL3L-engineered exosomes loaded with PKM2-vMO to K562/G01 cells can most effectively promote the apoptosis of drug-resistant cells.

A, B RT-qPCR and Western blot detection of changes in PKM1 and PKM2 mRNA and protein expression in K562/G01 cells cocultured with engineered exosomes loaded with vMO. Effects of engineered exosomes loaded with PKM2-vMO on imatinib resistance (C, D) and apoptosis (E, F) in K562/G01 cells and the viability of HS-5 cells (G).

vMO-engineered exosomes loaded with exosomes inhibited the malignant biological phenotypes of CML cells

K562/G01 cells were cocultured with exosomes from each group for 48 h, and the IC50 values of IM in the different treatment groups were detected. The results revealed that the IC50 of the blank control group was 3.735 µM; after pretreatment with 2 µM IM and culture with K562/G01 cells, the IC50 values of the blank control group and the RS-vMO Exos control group were 3.788 µM and 3.804 µM, respectively, with no significant change in the IC50 value; the IC50 value of the PKM2-vMO experimental group was 2.262 µM; the IC50 value of the PKM2-vMO Exos experimental group was 2.202 µM; and the IC50 value of the IL3L-PKM2-vMO Exos experimental group was 1.771 µM (Fig. 8C, D). The results indicated that in the drug-resistant CML cell line, the IC50 of the PKM2-vMO Exos experimental group decreased and was similar to that of the PKM2-vMO experimental group, and the sensitivity of cells to IM significantly increased. Compared with the other two groups, the IL3L-PKM2-vMO Exos experimental group more effectively increased the sensitivity of cells to IM and reversed the drug resistance of K562/G01 cells to IM.

Flow cytometry was used to detect cell apoptosis. The results revealed that pretreatment with 2 µM IM induced partial apoptosis of K562/G01 cells, and the apoptosis rate increased in the blank control group and the RS-vMO Exos control group. On this basis, the percentage of apoptotic cells in the PKM2-vMO experimental group and the PKM2-vMO Exos experimental group was greater than that in the control group. The IL3L-PKM2-vMO Exos in the experimental group most significantly promoted cell apoptosis, increasing the apoptosis rate (Fig. 8E, F). This trend was consistent with the IC50 results of the different treatment groups on K562/G01 cells mentioned above.

We also detected that after bone marrow stromal HS-5 cells were treated with exosomes from each group loaded with vMO, the cell viability remained essentially unchanged, with no significant difference (Fig. 8G). This finding indicated that the vMO-loaded exosomes had no toxic effect on bone marrow stromal cells, demonstrating their ability to target drug-resistant cells and potential biological safety.

Discussion

The Warburg effect and glycolytic reprogramming are established hallmarks of cancer30,31, and their association with poor prognosis and drug resistance in AML has been observed32,33. However, a systematic framework that translates glycolytic heterogeneity into actionable therapeutic strategies has been lacking. Our study moves beyond correlation to establish a comprehensive pipeline from computational discovery to therapeutic intervention. We first defined robust glycolytic molecular subtypes, identified a key mechanistic driver (PKM) linking aggressive subtyping to resistance, and ultimately developed and validated a novel, targeted nanotherapeutic strategy to reverse this resistance.

Myeloid leukemia has a high-glycolysis score and is associated with an unfavorable prognosis, indicating that glycolysis may play a crucial role in the initiation and progression of AML. Single-cell data provide compelling evidence that AML cells derived from hematopoietic stem cells, progenitor cells, and granulocyte‒monocyte progenitor cells exhibit significantly elevated glycolytic scores compared with their normal counterparts. We also attempted to elucidate the potential regulatory mechanism underlying AML glycolytic activity, revealing a significant positive correlation between HIF1A and GRG expression. Several experimental studies have confirmed that HIF1A promotes glycolysis in AML cells by regulating GRG expression34,35,36,37, further reinforcing the reliability of our bioinformatics analysis results. Additionally, MIF may modulate the function of TME cells through the secretion of proteins, thereby affecting the activities of CD74, CD44, and CXCR4. In leukemia, MIF/CD74 interactions play pivotal roles in tumor cell survival, tumor progression, and metastasis. For example, MIF binding to CD74 upregulates BCL-2 and CD84 expression38, inducing NF-κB activation and TAp63 upregulation, consequently leading to IL-8 secretion, which promotes cell survival39. Furthermore, CD74, along with its target genes TAp63 and VLA-4, facilitates CLL cell migration back into the bone marrow39. Therefore, GRGs have diverse biological functions, necessitating a comprehensive understanding of their molecular characteristics.

We subsequently confirmed the presence of the two subtypes of glycolytic molecules in multiple AML cohorts. The high-glycolytic score subtype is associated with a significantly worse prognosis, potentially because of an increased proportion of malignant cells, increased activity of cancer-related pathways, and a greater frequency of genomic variations. The precise identification of molecular subtypes also facilitates the establishment of personalized treatment programs. The isolated cells in the high-glycolysis score group presented increased sensitivity to panobinostat, MK-2206, tanespimycin, and cediranib, which exert antitumor effects by targeting HDAC inhibition, AKT suppression, HSP90 blockade, and VEGFR inhibition, respectively. Panobinostat, MK-2206, and tanespimycin promote apoptosis and enhance the cytotoxicity of cytarabine in AML cells40,41,42, and relevant clinical experiments have confirmed their value in vivo43. Additionally, we predicted that subtypes with high-glycolysis scores would be more responsive to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy, thus providing a new therapeutic basis for this group of patients. Among the glycolytic genes, PKM emerged as a prime candidate from our bioinformatic analysis due to its significant upregulation in the C1 subtype. To functionally validate its role, we leveraged the strong biological parallel between CML disease progression and our AML subtypes. We posited that the transition from the treatment-sensitive chronic phase (CP, modeling the C2 subtype) to the aggressive, therapy-resistant blast crisis (BC, modeling the C1 subtype) would be underpinned by a metabolic shift. Our findings confirmed this: a pronounced switch from PKM1 to PKM2 expression was evident in imatinib-resistant patients and in the isogenic K562/G01 CML-BC model. This positions PKM2 not merely as a glycolytic enzyme, but as a key executor of the “C1-like” resistant phenotype, directly bridging our computational finding with a tractable therapeutic mechanism. The designed vMO effectively modulated PKM splicing from PKM2 to PKM1, reversing imatinib resistance in vitro and in vivo. However, its non-specific cytotoxicity to bone marrow stromal cells highlighted the critical barrier of targeted delivery for therapeutic oligonucleotides. Our study provides a sophisticated solution: IL3-receptor-targeted exosomes (IL3L-Exos). This delivery system successfully addressed the dual challenges of (1) specificity, by efficiently delivering vMO to IL3-R-expressing leukemia cells while sparing non-target cells, and (2) safety, by shielding the cargo and significantly reducing off-target toxicity. The IL3L-Exos/vMO complex achieved the most potent PKM splicing correction and resistance reversal, effectively transforming a promising oligonucleotide into a targeted, clinically viable nanotherapeutic.

The 9-gene prognostic signature, developed through a rigorous multi-algorithmic approach and validated across ten independent cohorts, demonstrates remarkable generalizability. The predictive power of this model is underpinned by the strong biological rationale of its components, most of which are established players in glycolysis and leukemogenesis44,45,46. This fusion of computational robustness with biological credibility enhances the model’s potential clinical utility.

We acknowledge the limitations of our study. The prognostic model and subtype analyses, while validated in multiple retrospective cohorts, require confirmation in prospective clinical trials. Furthermore, although the CML-BC model is a highly relevant surrogate for aggressive AML, the efficacy of the IL3L-Exos/vMO strategy must be further validated in primary AML samples, particularly across different genetic subtypes. Finally, the translational path for this system necessitates addressing challenges related to scalable GMP production, comprehensive in vivo pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics, and long-term biosafety studies.

In conclusion, our work establishes a closed loop from systems-level discovery to targeted nanotherapy. We defined a clinically relevant glycolytic taxonomy of AML, identified and functionally validated PKM as a master regulator of the resistant subtype in a pertinent disease model, and engineered a novel exosome-based delivery platform to overcome the toxicity of this intervention. This integrated approach provides a robust foundation for targeting hyper-glycolytic, drug-resistant myeloid leukemia with precision and efficacy.

Methods

Data collection and preprocessing

Ten groups of AML samples were utilized in this study, encompassing a total of 2680 AML samples with available clinical information. These groups consisted of seven Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets: GSE10358-GPL570, GSE12417-GPL96, GSE12417-GPL570, GSE37642-GPL96, GSE37642-GPL570, and GSE71014-GPL10558. Additionally, 173 AML samples were obtained from the TCGA-LAML cohort from the UCSC Xena database (https://xena.ucsc.edu/). The HOVON group was obtained from the ArrayExpress database (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/biostudies/arrayexpress). The RNA-seq and matched clinical data for the Beat AML group were downloaded from the Vizome database (http://www.vizome.org/aml2/). The GSE13159-GPL570 cohort comprised 750 cases of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), 542 cases of AML, 448 cases of chronic lymphoblastic leukemia (CLL), 76 cases of chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), and 206 cases of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) to compare glycolytic activity in different blood tumors. To ensure consistency across platforms for GEO groups on the GPL96 and GPL570 chip platforms, we acquired the original “CEL” file and performed data normalization via the robust multiarray averaging (RMA) method. Standardized data files were downloaded from other GEO groups on different platforms. RNA sequencing data from the TCGA-LAML, GSE106291, and Beat AML groups were converted into transcripts per million (TPM) values. Data on methylation, somatic mutation, and gene copy number were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). Table S1 provides sample information for all the groups. All of the experiments were approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (No. review. [2018] No. (092)).

Single-cell RNA-seq data processing

We obtained AML single-cell sequencing data (GSE116256) for 21 different cell types from the GEO database. To ensure accuracy, we consulted the relevant literature on single cells47,48. R software was used to process the 10× scRNA-seq data following a standardized procedure. We filtered out genes that were not expressed in at least three single cells and removed cells with unique molecular identifier (UMI) counts of less than 200. Additionally, we included only cells that expressed between 1500 and 6000 genes. Cells with mitochondrial gene expression exceeding 20% were considered of low quality and were excluded from further analysis. Normalized counts were obtained by applying library size normalization to the original matrix, followed by identifying the top 2000 genes with high coefficients of variation via the “FindVariableFeatures” function. After z-score transformation, principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted on these highly variable genes. To visualize the clustering patterns, we employed the uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) algorithm. The cell types were annotated according to the van et al. annotation file49. We utilized the “CellChat” package to analyze intercellular communication networks within AML samples to identify potential regulatory roles.

Analysis of functional enrichment and estimation of the cellular composition of AML samples

The software package “clusterProfiler” was used for performing Gene Ontology (GO) annotation and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment analysis50. The pathway score was calculated via the gene set variation analysis (GSVA) algorithm to quantify the activity level of each pathway51. The CIBERSORT algorithm employs a support vector regression model to deconvolve bulk gene expression profiles into cell-type compositions, utilizing a reference matrix that contains gene expression signatures (GESs) specific to the desired cell types of interest. To construct the GES reference matrix for the 21 required cell types in CIBERSORT, we randomly sampled 200 instances of each cell type via AML scRNA-seq profiles. We subsequently estimated the relative proportions of these 21 AML cell types within the bulk gene expression dataset52, including hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), HSC-like progenitors (Prog), Prog-like, granulocyte–monocyte–progenitor (GMP), GMP-like, promonocyte (ProMono), ProMono-like, monocyte (Mono), Mono-like, conventional dendritic cell (cDC), cDC-like, plasmacytoid dendritic cell (pDC), early erythroid progenitor (earlyEry), late erythroid progenitor (lateEry), progenitor B-cell (proB), mature B-cell (B), plasma cell (plasma), naïve T-cell (T), cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL), and natural killer cell (NK) populations.

Identification of molecular subtypes

The AML samples were subjected to unsupervised clustering via the “ConsensusClusterPlus” package, and 1000 resampling iterations were conducted to ensure the reliability of the cluster analysis results.

Development of a prognostic model through the integration of machine learning approaches

Initially, we utilized univariate Cox regression analysis to identify glycolysis-related genes (GRGs) that were significantly associated with prognosis (P < 0.05) in at least four of the ten AML datasets while maintaining a consistent hazard ratio (HR) orientation. The TCGA-LAML dataset was designated the primary cohort for analysis, and the remaining datasets were used as the validation cohort. We employed 10 different machine learning algorithms, including CoxBoost, stepwise Cox, Lasso, Ridge, elastic net (Enet), survival support vector machines (survival-SVMs), generalized boosted regression models (GBMs), supervised principal components (SuperPCs), partial least Cox (plsRcox), and RSF. These algorithms were combined in 118 different ways within a 10-fold cross-validation framework, using the TCGA-LAML training cohort for variable selection and model construction. All the constructed models were evaluated in both the validation and analysis cohorts by calculating their C-index values. The predictive performance of each model was ranked on the basis of its average C-index within the validation cohort. Finally, we selected a combination of algorithms that demonstrated robust performance and clinical translational significance to develop a risk score model capable of predicting the prognosis of patients with AML. In this study, we specifically utilized the CoxBoost and StepCox (forward) algorithms to construct the risk-scoring model.

In the model gene, “i” represents the regression coefficient as “Coef,” and the expression value is “ExpGene” (Table S2). By applying an optimal cutoff value, all the AML cohorts were categorized into high- and low-risk groups for subsequent analysis.

Drug sensitivity analysis and immunotherapy response assessment

We analyzed the experimental data of drugs administered to isolated AML cells from the Beat AML cohort. We compared the AUC values of multiple drug treatments across different molecular subtypes, where a smaller AUC value indicated greater drug sensitivity. We used a significance level of P < 0.001 to identify drugs with significant differences in sensitivity. Additionally, we utilized the SubMap algorithm (https://cloud.genepattern.org/gp) to predict the response of various molecular subtypes to immunotherapy with anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA4 agents. Furthermore, to assess the degree of tumor immune evasion, we used the Tumor Immune Dysfunction and Exclusion (TIDE) website (http://tide.dfci.harvard.edu/) to calculate the TIDE score of the AML samples53.

Cell culture

The K562 and K562/G01 cell lines, obtained from the Institute of Hematology at the Chinese Academy of Medical Science in Tianjin, China, were maintained in RMPI 1640 medium (Bioind, Israel) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Bioind), 100 U/ml penicillin, and streptomycin. HEK-293T, HS-5, and BT-549 cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. The cells were then incubated at 37 °C with a CO2 concentration of 5% in a humidified incubator. IM was procured from Sigma‒Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), while IM-resistant K562/G01 cells were cultured as previously described54.

Morpholinos transfection

On the basis of the abnormal splicing pattern of PKM pre-mRNA, we developed and synthesized a specific vMO sequence labeled with fluorescein FAM (Gene Tools, USA). vMO (5′-CGC CAG GCG GCG GAG TTC CTC AAA TAA T-3′) was designed to target the splice junction between exons 9 and 10 of PKM pre-mRNA. An antisense oligonucleotide (5′-CCT CTT ACC TCA GTT ACA ATT TAT A-3′) was used as a control. The cocultured cells were washed with PBS until no fluorescence signal remained, and flow cytometry was used to measure the level of fluorescence activity. Endo-Porter is known for its unique delivery capabilities, and gene tools have minimal toxicity and optimal delivery when the recommended concentration of 6 μmol/l (equivalent to 6 μl/ml of media) is used for assessing antisense activity at 48 h. Gene tools suggest starting with a morpholino oligo concentration of 10 μmol/l and adjusting it on the basis of experimental outcomes. To further optimize the reaction conditions, K562 cells were coincubated with vMO concentrations ranging from 2 to 12 μmol/l (corresponding to volumes ranging from 2 to 12 μl per ml of media), allowing for comprehensive evaluation.

RNA extraction and real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cells via TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time quantitative PCR (RT‒qPCR) analysis was conducted on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) using a TaqMan Probe qPCR SuperMix Kit (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). For PKM1 gene amplification, the following primers were used: forward primer, 5′-GCT GCC ATC TAC CAC TTG C-3′ and reverse primer, 5′-CCA GAC TTG GTG AGG ACG ATT-3′. Similarly, for PKM2 gene amplification, the forward primer 5′-GAA GAA CTT GTG CGA GCC T-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CGT CAG AAC TAT CAA AGC TGC-3′ were used. GAPDH gene amplification was performed via the following primers: forward primer, 5′-CAG CCT CAA GAT CAT CAG CA-3′ and reverse primer, 5′-TGT GGT CAT GAG TCC TTC CA-3′. The comparative threshold cycle (Ct) value was used for data analysis of each parameter. The changes in expression were calculated relative to those of the control group via the formula 2−ΔΔCt.

Western blot analysis

Total proteins were separated via 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Beyotime) and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, MA, USA). To block the PVDF membranes, they were incubated with 5% skim milk in PBS for 2 h. The membranes were subsequently incubated overnight with anti-PKM1/2 antibody (1:1000 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology, USA) and anti-β-actin antibody (1:1000 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology, USA). Following three washes with TBST buffer solution, the membranes were exposed to horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (1:10,000 dilution; Proteintech, Rosemont, IL, USA) at room temperature for 1 h. After washing again, the protein bands on the strips were visualized via a chemiluminescence reagent kit (Beyotime, China). The resulting images of the protein bands were captured via ChemiScope Series equipment (Clinx Science Instrument Co., China).

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay

Cell cytotoxicity was assessed via a CCK-8 assay (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China). K562 or K562/G01 cells were seeded at a density of 20,000 cells/well in 96-well plates. The IM group, fluorescent-labeled vMO group, combination of IM and vMO (IM+vMO), and untreated control groups were cocultured with the respective cell types. Different concentrations of IM were added to both cell types for 48 h. Subsequently, the CCK-8 reagent (10 μl/well) was added after IM treatment, and the mixture was incubated for 2 h. The absorbance at 450 nm was measured via an ELISA-format spectrophotometer. Each experiment was replicated three times, and the mean value represents the data obtained. The inhibition rate was calculated as follows: 1-(treated OD-blank OD)/(control OD-blank OD).

Flow cytometry for the cell apoptosis assay

Apoptotic cells were assessed via Annexin V-FITC/PI (for K562) or Annexin V PE/7-AAD (for K56/G01) apoptotic detection kits (Solarbio) following the manufacturer’s guidelines. The cells were plated at a density of 106 cells per well and incubated for 15 min at room temperature according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A Beckman Coulter CytoFLEX S flow cytometer was used to analyze the proportions of early apoptotic and late apoptotic/dead cells.

In vivo xenograft model of human CML in BALB/c-nu mice

The BALB/c-nu mice used in this study were obtained from Nanchang University. All experiments were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University (no. review. [2018] No. (092)). To induce local tumor formation, 1 × 107 K562 cells were subcutaneously injected into female BALB/c-nu mice aged 5–6 weeks (n = 4 per group). The mice were randomly divided into 10 groups. Two weeks after transplantation, an intratumoral injection of vMO (8.4 mg/kg) was administered every other day, whereas IM (50, 100, or 200 mg/kg/day) was administered orally once daily. Different concentrations of IM alone or in combination with vMO were administered for a duration of 2 weeks, with saline serving as the control treatment. Additionally, vMO was administered via tail vein injection every other day to female BALB/c-nu mice, whereas IM (100 mg/kg/day) was administered orally once daily. Tumor growth was monitored regularly and measured every other day via calipers to determine the tumor size. The tumor volume was calculated via the following formula: volume = 1/2 × length × width2. Paraffin-embedded tissue samples were prepared for immunohistochemical staining.

Construction of lentiviruses expressing the IL3-Lamp2b protein and cell lines stably expressing the IL3-Lamp2b protein

On the basis of the literature29, we constructed a plasmid containing the fusion gene of recombinant human Lamp2b and human interleukin-3. Then, a 6*XHIS tag was added to the C-terminus of the protein for verification of recombinant protein expression. GENEWIZ was used to construct a lentivirus expressing the IL3-Lamp2b fusion protein. Subsequently, well-grown HEK-293T cells were seeded into 6-well plates at a density of 1×10⁵ cells/well and cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO₂ for 16–24 h. When the cell confluence reached 20–30%, the calculated volume of lentivirus suspension was added at an MOI of 20, along with the corresponding concentration of transfection reagent. The final volume of each well was adjusted to 2 mL. After 16 h of virus infection, the medium was replaced with complete medium (if the cell condition was abnormal, the medium was replaced at 8 h). After 72 h of continuous culture, fluorescence was observed under a fluorescence microscope. When the cell condition was good and the fluorescence expression was obvious, puromycin at an appropriate concentration (usually 1–5 μg/mL) was added for screening culture. A stably transfected cell line was successfully obtained when more than 90% of the surviving cells showed stable fluorescence under a fluorescence microscope.

Exosome preparation

After the HEK-293T cells were gently washed three times with PBS at a confluence of 80–90%, they were cultured in serum-free DMEM for 48 h. After the culture, the supernatant was collected and subjected to gradient centrifugation: first, it was centrifuged at 500 × g for 10 min to remove the suspended cells; then, the supernatant was transferred to a new centrifuge tube, centrifuged at 2000 × g for 20 min to further remove the cell debris; and finally, it was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 20 min to remove the cell fragments and small particles, obtaining a clear conditioned medium. The supernatant was concentrated to an appropriate volume via a 100 kDa ultrafiltration tube (5000 × g, 5 min). The concentrated cell supernatant was collected, transferred to an ultracentrifuge tube, and centrifuged at 120,000 × g for 1 h and 30 min via ultracentrifugation. The supernatant was discarded, and the precipitate was collected as exosomes. The exosome precipitate was resuspended in an appropriate amount of PBS and stored at 4 °C for short-term preservation (≤3 days) or at −80 °C for long-term storage.

Electron microscopy observation

A total of 10 µL of the exosome sample was mixed with an equal volume of 4% paraformaldehyde solution for fixation; the fixed sample was added to the surface of a 200-mesh carbon support film copper grid (pore diameter of 2 nm) and allowed to stand at room temperature for 1 min for adsorption; the excess liquid from the edge of the copper grid was gently absorbed at a 45° angle with filter paper, and 10 µL of 2% uranyl acetate negative staining solution (pH 4.5) was immediately added for staining for 1 min; the staining solution was again absorbed with filter paper, and the copper grid was placed in a desiccator at room temperature and away from light for 30 min to dry. Finally, the samples were observed with a transmission electron microscope at an acceleration voltage of 100 kV and magnified to collect typical morphological images of the exosomes.

Particle size determination

Exosomes were appropriately diluted with 1× PBS. The size distribution and concentration of the exosomes were determined via NTA via a ZetaView particle size analyzer. The exosome mixture was illuminated with a 488 nm laser, and the movement of the nanoparticles caused by Brownian motion was recorded for 60 s at an average frame rate of 20 frames per second. The NTA values at multiple positions were recorded and analyzed via the corresponding software (ZetaView).

Exosome uptake experiment

One milliliter of diluent C buffer (from the Solarbio PKH26 kit) was added, 4 μL of PKH26 red fluorescent dye was added, and the mixture was mixed thoroughly and labeled as Tube A. Another 1 mL of diluent C buffer was added, and 20 μg of purified sEVs was added, which was labeled as Tube B. Tube A and Tube B were mixed in equal volumes and incubated at room temperature in the dark for 5 min to allow the dye to stably bind to the sEV membrane lipid bilayer. Then, 2 mL of fetal bovine serum was added to terminate the reaction, and the serum protein bound to the excess free dye molecules. The labeled mixture was transferred to an ultracentrifuge tube and centrifuged at 120,000 × g for 90 min at 4 °C to completely remove the unbound dye molecules. The supernatant was discarded, and the sEV precipitate was gently resuspended in 100 μL of precooled PBS and stored at 4 °C in the dark for later use. Next, the cells of each cell line were seeded at a density of 2 × 104 cells per well in 24-well plates with sterilized coverslips preplaced. After the cells stabilized (approximately 12 h), an equal amount of PKH26-labeled sEVs was added to each well. Three time points, 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h, were set, and the samples were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO₂ incubator. After reaching the predetermined time, different types of cells were treated differently: for the suspended K562/G01 cells, they were first collected via centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 5 min and then washed twice with PBS (1000 rpm × 3 min); for the adherent HS-5 and BT-549 cells, the culture medium was directly discarded, and the coverslips were gently rinsed with prewarmed PBS three times. The K562/G01 cells were resuspended, added to new coverslips, and incubated with coverslips containing adherent cells at room temperature for 5 min. All coverslips were fixed with 500 μL of 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 20 min and then washed three times with PBS on a horizontal shaker. To permeabilize the nuclear membrane, it was treated with 0.2% Triton X-100 at room temperature for 15 min and then washed three times with PBS. Next, 500 μL of DAPI working solution was added for nuclear staining for 20 min, and the samples were then washed three times thoroughly with PBS. Coverslips were sealed with anti-fluorescence quenching mounting medium. A confocal microscope with a 40× objective was used to collect images. Five fields of view were randomly selected for each sample, and the fluorescence intensity was quantitatively analyzed via ImageJ software.

vMO load experiment

In this study, the ExoLoad® nucleic acid loading kit from Enzogenetix was used to encapsulate vMO effectively into the exosomes. The reagents were added in the following sequence and proportion: 10 µl of vMO (1 mM), 100 µg of exosomes, 20 µl of ETP, and a reaction mixture with a volume of 1/10 of the exosome volume. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C in the dark for 2 h, with continuous shaking at 150 rpm during the incubation. After incubation, the exosomes were transferred to a 100 kDa ultrafiltration tube and subjected to ultrafiltration centrifugation again to obtain vMO-loaded exosomes, and free small nucleic acids were removed. The vMO-loaded exosomes were cocultured with K562/G01 cells for 48 h, and gene expression and related phenotypes were detected.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed via R software. The Wilcoxon test was used to evaluate disparities between two groups, whereas the Kruskal‒Wallis test was used to compare differences among multiple groups. Data are presented as mean ± SD, a significance level of P < 0.05 was considered (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001).

Data availability

All data used in this work can be acquired from the Gene-Expression Omnibus (GEO; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) databases (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/).

Code availability

All custom code can be obtained from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Yamashita, M., Dellorusso, P. V., Olson, O. C. & Passegué, E. Dysregulated haematopoietic stem cell behaviour in myeloid leukaemogenesis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 20, 365–382 (2020).

Shimony, S., Stahl, M. & Stone, R. M. Acute myeloid leukemia: 2023 update on diagnosis, risk-stratification, and management. Am. J. Hematol. 98, 502–526 (2023).

Döhner, H., Weisdorf, D. J. & Bloomfield, C. D. Acute myeloid leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 1136–1152 (2015).

Short, N. J. et al. Advances in the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia: new drugs and new challenges. Cancer Discov. 10, 506–525 (2020).

Thol, F. & Ganser, A. Treatment of relapsed acute myeloid leukemia. Curr. Treat. options Oncol. 21, 66 (2020).

Marie, J. P. Drug resistance in hematologic malignancies. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 13, 463–469 (2001).

Stevens, B. M. et al. Fatty acid metabolism underlies venetoclax resistance in acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Nat. Cancer 1, 1176–1187 (2020).

Zhang, J., Gu, Y. & Chen, B. Mechanisms of drug resistance in acute myeloid leukemia. Onco Targets Ther. 12, 1937–1945 (2019).

Hanahan, D. & Weinberg, R. A. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 (2011).

Fukushi, A., Kim, H. D., Chang, Y. C. & Kim, C. H. Revisited metabolic control and reprogramming cancers by means of the Warburg effect in tumor cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms231710037 (2022).

Vaupel, P., Schmidberger, H. & Mayer, A. The Warburg effect: essential part of metabolic reprogramming and central contributor to cancer progression. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 95, 912–919 (2019).

Icard, P. et al. How the Warburg effect supports aggressiveness and drug resistance of cancer cells?. Drug Resist. Updates 38, 1–11 (2018).

Song, K. et al. Resistance to chemotherapy is associated with altered glucose metabolism in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncol. Lett. 12, 334–342 (2016).

Åbacka, H. et al. Targeting GLUT1 in acute myeloid leukemia to overcome cytarabine resistance. Haematologica 106, 1163–1166 (2021).

Zhang, Y., Liu, Y. & Xu, X. Knockdown of LncRNA-UCA1 suppresses chemoresistance of pediatric AML by inhibiting glycolysis through the microRNA-125a/hexokinase 2 pathway. J. Cell Biochem. 119, 6296–6308 (2018).

Chen, L., Hu, N., Wang, C. & Zhao, H. HOTAIRM1 knockdown enhances cytarabine-induced cytotoxicity by suppression of glycolysis through the Wnt/β-catenin/PFKP pathway in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 680, 108244 (2020).

Chen, L., Zhao, H., Wang, C. & Hu, N. TUG1 knockdown enhances adriamycin cytotoxicity by inhibiting glycolysis in adriamycin-resistant acute myeloid leukemia HL60/ADR cells. RSC Adv. 9, 10897–10904 (2019).

Mpakou, V. et al. Upregulated hypoxia inducible factor 1α signaling pathway in high risk myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia patients is associated with better response to 5-azacytidine-data from the Hellenic myelodysplastic syndrome study group. Hematol. Oncol. 39, 231–242 (2021).

Noguchi, T., Inoue, H. & Tanaka, T. The M1- and M2-type isozymes of rat pyruvate kinase are produced from the same gene by alternative RNA splicing. J. Biol. Chem. 261, 13807–13812 (1986).

Hitosugi, T. et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation inhibits PKM2 to promote the Warburg effect and tumor growth. Sci. Signal. 2, ra73 (2009).

Goldberg, M. S. & Sharp, P. A. Pyruvate kinase M2-specific siRNA induces apoptosis and tumor regression. J. Exp. Med. 209, 217–224 (2012).

Lunt, S. Y. et al. Pyruvate kinase isoform expression alters nucleotide synthesis to impact cell proliferation. Mol. Cell 57, 95–107 (2015).

Christofk, H. R. et al. The M2 splice isoform of pyruvate kinase is important for cancer metabolism and tumour growth. Nature 452, 230–233 (2008).

Xie, H., Yao, J., Wang, Y. & Ni, B. Exosome-transmitted circVMP1 facilitates the progression and cisplatin resistance of non-small cell lung cancer by targeting miR-524-5p-METTL3/SOX2 axis. Drug Deliv. 29, 1257–1271 (2022).

Zhang, M. et al. Engineered exosomes from different sources for cancer-targeted therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 8, 124 (2023).

Nievergall, E. et al. Monoclonal antibody targeting of IL-3 receptor α with CSL362 effectively depletes CML progenitor and stem cells. Blood 123, 1218–1228 (2014).

Testa, U. et al. Elevated expression of IL-3Ralpha in acute myelogenous leukemia is associated with enhanced blast proliferation, increased cellularity, and poor prognosis. Blood 100, 2980–2988 (2002).

Testa, U., Pelosi, E. & Frankel, A. CD 123 is a membrane biomarker and a therapeutic target in hematologic malignancies. Biomark. Res. 2, 4 (2014).

Bellavia, D. et al. Interleukin 3- receptor targeted exosomes inhibit in vitro and in vivo Chronic Myelogenous Leukemia cell growth. Theranostics 7, 1333–1345 (2017).

Paul, S., Ghosh, S. & Kumar, S. Tumor glycolysis, an essential sweet tooth of tumor cells. Semin Cancer Biol. 86, 1216–1230 (2022).

Chelakkot, C., Chelakkot, V. S., Shin, Y. & Song, K. Modulating glycolysis to improve cancer therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 24, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24032606 (2023).

Chen, W. L. et al. A distinct glucose metabolism signature of acute myeloid leukemia with prognostic value. Blood 124, 1645–1654 (2014).

Yang, Y., Pu, J. & Yang, Y. Glycolysis and chemoresistance in acute myeloid leukemia. Heliyon 10, e35721 (2024).

Zhou, H. et al. Therapeutic inhibition of PPARα-HIF1α-PGK1 signaling targets leukemia stem and progenitor cells in acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Lett. 554, 215997 (2023).

Zhu, Y. et al. PARP14 promotes the growth and glycolysis of acute myeloid leukemia cells by regulating HIF-1α expression. Clin. Immunol. 242, 109094 (2022).

Ma, P. et al. High PD‑L1 expression drives glycolysis via an Akt/mTOR/HIF‑1α axis in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncol. Rep. 43, 999–1009 (2020).

Zhao, F. et al. Imatinib resistance associated with BCR-ABL upregulation is dependent on HIF-1alpha-induced metabolic reprograming. Oncogene 29, 2962–2972 (2010).

Luo, Y., Wang, X., Shen, J. & Yao, J. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor in the pathogenesis of leukemia (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 59, https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2021.5242 (2021).

Shachar, I. & Haran, M. The secret second life of an innocent chaperone: the story of CD74 and B cell/chronic lymphocytic leukemia cell survival. Leuk. Lymphoma 52, 1446–1454 (2011).

Lu, J. W. et al. MK-2206 induces apoptosis of AML cells and enhances the cytotoxicity of cytarabine. Med. Oncol. 32, 206 (2015).

Mesa, R. A. et al. Heat shock protein 90 inhibition sensitizes acute myelogenous leukemia cells to cytarabine. Blood 106, 318–327 (2005).