Abstract

The fine-grained dynamic sparsity in biological synapses is an important element in the energy efficiency of the human brain. Emulating such sparsity in an artificial system requires off-chip memory indexing, which has a considerable energy and latency overhead. Here, we report an in-memory sparsity architecture in which index memory is moved next to individual synapses, creating a sparse neural network without external memory indexing. We use a compact building block consisting of two non-volatile ferroelectric field-effect transistors acting as a digital sparsity and an analogue weight. The network is formulated as the Hadamard product of the sparsity and weight matrices, and the hardware, which is comprised of 900 ferroelectric field-effect transistors, is based on wafer-scale chemical-vapour-deposited molybdenum disulfide integrated through back-end-of-line processes. With the system, we demonstrate key synaptic processes—including pruning, weight update and regrowth—in an unstructured and fine-grained manner. We also develop a vectorial approximate update algorithm and optimize training scheduling. Through this software–hardware co-optimization, we achieve 98.4% accuracy in an EMNIST letter recognition task under 75% sparsity. Simulations on large neural networks show a tenfold reduction in latency and a ninefold reduction in energy consumption when compared with a dense network of the same performance.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Source data are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27284259.v1 (ref. 52).

Code availability

The codes used for sparse training, scheduling and simulations are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Shoham, S., O’Connor, D. H. & Segev, R. How silent is the brain: is there a ‘dark matter’ problem in neuroscience? J. Comp. Physiol. A 192, 777–784 (2006).

Shore, R. Rethinking the Brain: New Insights into Early Development (Families and Work Institute, 1997).

Huttenlocher, P. R., De Courten, C., Garey, L. J. & Van der Loos, H. Synaptogenesis in human visual cortex—evidence for synapse elimination during normal development. Neurosci. Lett. 33, 247–252 (1982).

Holmgren, C., Harkany, T., Svennenfors, B. & Zilberter, Y. Pyramidal cell communication within local networks in layer 2/3 of rat neocortex. J. Physiol. 551, 139–153 (2003).

Bullmore, E. & Sporns, O. Complex brain networks: graph theoretical analysis of structural and functional systems. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 10, 186–198 (2009).

McCulloch, W. S. & Pitts, W. A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity. Bull. Math. Biophys. 5, 115–133 (1943).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

Faust, T. E., Gunner, G. & Schafer, D. P. Mechanisms governing activity-dependent synaptic pruning in the developing mammalian CNS. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 22, 657–673 (2021).

LeCun, Y., Denker, J. S. & Solla, S. A. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 2 (ed. Touretzky, D.) 598–605 (Morgan Kaufmann, 1990).

Torsten, H., Dan, A., Tal, B.-N., Nikoli, D. & Alexandra, P. Sparsity in deep learning: pruning and growth for efficient inference and training in neural networks. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 22, 10882–11005 (2021).

Deng, L., Li, G., Han, S., Shi, L. & Xie, Y. Model compression and hardware acceleration for neural networks: a comprehensive survey. Proc. IEEE 108, 485–532 (2020).

Han, S., Pool, J., Tran, J. & Dally, W. J. Learning both weights and connections for efficient neural networks. In Proc. 28th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 1 (eds Cortes, C. et al.) 1135–1143 (MIT Press, 2015).

Mao, H. et al. Exploring the granularity of sparsity in convolutional neural networks. In 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW) 1927–1934 (IEEE, 2017).

Mocanu, D. C. et al. Scalable training of artificial neural networks with adaptive sparse connectivity inspired by network science. Nat. Commun. 9, 2383 (2018).

Lim, D.-H. et al. Spontaneous sparse learning for PCM-based memristor neural networks. Nat. Commun. 12, 319 (2021).

Sheridan, P. et al. Sparse coding with memristor networks. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 784–789 (2017).

Mohanty, A. et al. Random sparse adaptation for accurate inference with inaccurate multi-level RRAM arrays. In 2017 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 6.3.1–6.3.4 (IEEE, 2017).

Wang, P. et al. SNrram: an efficient sparse neural network computation architecture based on resistive random-access memory. In 2018 Proceedings of the 55th Annual Design Automation Conference (DAC ‘18) 1–6 (IEEE, 2018).

Wong, H. S. & Salahuddin, S. Memory leads the way to better computing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 191–194 (2015).

Khan, A. I., Keshavarzi, A. & Datta, S. The future of ferroelectric field-effect transistor technology. Nat. Electron. 3, 588–597 (2020).

Jerry, M. et al. Ferroelectric FET analog synapse for acceleration of deep neural network training. In 2017 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 6.2.1–6.1.4 (IEEE, 2017).

Chen, W.-C. et al. 4 bits/cell hybrid 1F1R for high density embedded non-volatile memory and its application for compute in memory. In 2022 IEEE Symposium on VLSI Technology and Circuits (VLSI) 244–245 (IEEE, 2022).

Ni, K. et al. Ferroelectric ternary content-addressable memory for one-shot learning. Nat. Electron. 2, 521–529 (2019).

Luo, Y.-C. et al. Experimental demonstration of non-volatile capacitive crossbar array for in-memory computing. In 2021 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 1–4 (IEEE, 2021).

Lee, T.-E. et al. High-endurance MoS2 FeFET with operating voltage less than 1 V for eNVM in scaled CMOS technologies. In 2023 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 11.1.1–11.1.4 (IEEE, 2023).

Cheema, S. S. et al. Enhanced ferroelectricity in ultrathin films grown directly on silicon. Nature 580, 478–482 (2020).

Cheema, S. S. et al. Ultrathin ferroic HfO2–ZrO2 superlattice gate stack for advanced transistors. Nature 604, 65–71 (2022).

Wang, Y. et al. A stable rhombohedral phase in ferroelectric Hf(Zr)1+xO2 capacitor with ultralow coercive field. Science 381, 558–563 (2023).

Cao, W. et al. The future transistors. Nature 620, 501–515 (2023).

Li, M.-Y., Su, S.-K., Wong, H.-S. P. & Li, L.-J. How 2D semiconductors could extend Moore’s law. Nature 567, 169–170 (2019).

Qiu, H. et al. Two-dimensional materials for future information technology: status and prospects. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 67, 160400 (2024).

Akinwande, D. et al. Graphene and two-dimensional materials for silicon technology. Nature 573, 507–518 (2019).

Lemme, M. C. et al. 2D materials for future heterogeneous electronics. Nat. Commun. 13, 1392 (2022).

Peng, Z. et al. Two-dimensional materials-based integrated hardware. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 66, 160401 (2023).

Hus, S. M. et al. Observation of single-defect memristor in an MoS2 atomic sheet. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 58–62 (2021).

Huang, J.-K. et al. High-κ perovskite membranes as insulators for two-dimensional transistors. Nature 605, 262–267 (2022).

Ning, H. et al. From lab to fab: path forward for 2D material electronics. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 66, 160411 (2023).

Liu, C. et al. Two-dimensional materials for next-generation computing technologies. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 545–557 (2020).

Ning, H. et al. An in-memory computing architecture based on a duplex two-dimensional material structure for in situ machine learning. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 493–500 (2023).

Yang, R. et al. Ternary content-addressable memory with MoS2 transistors for massively parallel data search. Nat. Electron. 2, 108–114 (2019).

Migliato, M. G. et al. Logic-in-memory based on an atomically thin semiconductor. Nature 587, 72–77 (2020).

Migliato, M. G. et al. A large-scale integrated vector–matrix multiplication processor based on monolayer molybdenum disulfide memories. Nat. Electron. 6, 991–998 (2023).

Li, T. et al. Epitaxial growth of wafer-scale molybdenum disulfide semiconductor single crystals on sapphire. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 1201–1207 (2021).

Lecun, Y., Bottou, L., Bengio, Y. & Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 86, 2278–2324 (1998).

Cohen, G., Afshar, S., Tapson, J. & van Schaik, A. EMNIST: Extending MNIST to handwritten letters. In 2017 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN) 2921–2926 (IEEE, 2017).

Peng, X., Huang, S., Jiang, H., Lu, A. & Yu, S. DNN+NeuroSim V2.0: an end-to-end benchmarking framework for compute-in-memory accelerators for on-chip training. IEEE Trans. Comput.-Aided Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 40, 2306–2319 (2021).

Ghaffari, A. et al. in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems Vol. 35 (eds Koyejo, S. et al.) 27402–27413 (Curran, 2022).

Wang, M. et al. NITI: training integer neural networks using integer-only arithmetic. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 33, 3249–3261 (2022).

Jacob, B. et al. Quantization and training of neural networks for efficient integer-arithmetic-only inference. In Proc. IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition 2704–2713 (IEEE, 2018).

Schiffmann, W., Joost, M. & Werner, R. Optimization of the Backpropagation Algorithm for Training Multilayer Perceptrons Technical Report (University of Koblenz, 1994).

Li, H. et al. Visualizing the loss landscape of neural nets. In 2018 Proc. 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NIPS) (eds Bengio, S. et al.) 6391–6401 (Curran, 2018).

Ning, H. et al. Source_Data_Ning_et_al. Figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27284259.v1 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (grant numbers 2022YFB4400100 (X.W.), 2023YFF1500500 (X.W.), 2021YFA1202904 (L.G.), 2022YFA1402500 (W.L.), 2021YFA0715600 (W.L.), 2023YFB2806802 (Y.F.), 2021YFB3600104 (Y.F.)), the Leading-edge Technology Program of Jiangsu Natural Science Foundation (grant numbers BK20232024 (X.W.), BK20232001 (Y.S.)), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant numbers T2221003 (X.W.), 61927808 (X.W.), T2322014 (Y.Z.), 62204124 (Y.Z.), 62322408 (T.L.), 62204113 (T.L.), 62104098 (Y.F.), U21B2032 (L.L), 62304101 (W.L.)), Jiangsu Funding Program for Excellent Postdoctoral Talent (grant number 20220ZB63 (W.L.)), the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (grant number BK20220773 (T.L.), BK20230776 (W.L.), BK20210178 (Y.F.)), the Jiangsu Province Key R&D Program (BE2023009-3 (W.L.)), the Key Laboratory of Advanced Photonic and Electronic Materials, Collaborative Innovation Center of Solid-State Lighting and Energy-Saving Electronics, and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, China. We express our gratitude to the Interdisciplinary Research Center for Future Intelligent Chips (Chip-X) and Yachen Foundation for their invaluable support. X.W. acknowledges the support by the New Cornerstone Science Foundation through the XPLORER PRIZE.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Y. and X.W. supervised the project. H.N., Z.Y. and X.W. conceived the idea and designed the experiments. H.W. fabricated the array with assistance from H.N., Z.Y., W.L., X.L. and L.G. H.N. designed the software and hardware measurement system. H.W. performed the array measurement with assistance from H.N. and X.L. Y.M., Y.F., Y.S., Q.Z. and L. Li carried out the training algorithm, simulation and benchmarks. X.Z., L. Liu, S.Z. and T.L. synthesized the CVD MoS2. H.N., Z.Y. and X.W. co-wrote the manuscript with input from all authors. All authors contributed to the interpretation of data and discussion.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Electronics thanks Hongsik Jeong and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Trade-off dilemma of granularity in sparse training.

a, Illustration of process of sparsification and the granularity of sparse neural network (SPNN), layer-wise (the most coarse-grained), block-wise, vector-wise, and element-wise (the most fine-grained). b, The accuracy-efficiency trade-off dilemma of four granularities in sparse training. The data comes from the NeuroSim simulation of VGG8-Net on CIFAR-10 dataset, trained with IMC hardware (See more details in Methods and Extended Data Fig. 9).

Extended Data Fig. 2 Design and statistics of weight device and sparsity device.

a-b, The 3D schematic of the structure of weight device (a) and sparsity device (b). c-f, Distribution and spatial heatmap of memory window (c, d) and Ion/Ioff ratio (e, f) for all 450 weight devices in the index-free IMC array. The red lines are fitted curves by the normal distribution. g, Statistics of 16-state characteristics from 100 weight devices. On each box, the central mark indicates the median of conductance of these 100 devices on a certain weight, and the bottom and top edges of the box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The whiskers extend to the most extreme data points not considered outliers. h, Collected 8-state retention curves in 100 s from 50 weight devices (The shadow are dense lines of raw data rather than any error bands).

Extended Data Fig. 3 High temperature stability of index-free hardware.

a, transfer curves of sparsity and weight- FeFETs under 25 °C, 85 °C and 125 °C. b–c, 1000s retention of sparsity (b) and weight- FeFETs (c) can projected to 10 years. d-f, 128 states with sparsity- FeFETs on or off under 25 °C (d), 85 °C (e) and 125 °C (f). g-i, output curves of potentiation process with sparsity- FeFETs on under 25 °C (g), 85 °C (h) and 125 °C (i).

Extended Data Fig. 4 Test set-up.

a, The software and hardware structure of test system. b, Program chart of auto-test of index-free IMC array. c, the picture of test system. Inset 1 (yellow border): a zoom-in of probed array in the probe station. Inset 2 (blue border): a zoom-in of the cables and probe cards inside the probe station.

Extended Data Fig. 5 The VAU.

a, Two steps (by column vectors or rows vectors) of training process with VAU. b, The mean square error (MSE) of VAU as a function of sparsity, derived from 50 runs of VAU. Errors are generated by comparing the delta weights from VAU and the accurate ones from the cell-by-cell method. On each box, the central mark indicates the median of MSE for 50 runs, and the bottom and top edges of the box indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively. The outliers are plotted individually using the ‘o’ marker symbol outside the bounds of maximum and minimum. c, The training accuracy of sparse neural network (SPNN) with conventional cell-by-cell method and VAU (with 10% write noise and 4.25% read noise introduced), derived from 20 runs of corresponding algorithms. Here, only the maximums and minimums are plotted in this box plot. See more details in Methods.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Explanation of fundamental scenarios based on a column of index-free unit cells during sparse training.

Sparsity and weight values are displayed in the purple box and blue box, respectively. The changes in specific values are colored in yellow and bolded. Cells to prune are remarked with a red dashed border, and cells to regrowth are with green ones. Active cells are colored in gray and pruned cells are colored in a much lighter gray without border. The horizontal lines across cell boxes are paths of updating (bit lines in yellow) or inference (data input lines in blue), the vertical lines across the sparsity boxes are paths of pruning/regrowth (sparsity lines in purple), and the vertical lines across the weight boxes are the paths of summarizing currents (data output lines in gray).

Extended Data Fig. 7 The array-level hardware operations and data details.

a, Array-level data flow of MSNet training. b, Synchronous output current sequence read from array made of 4000 points cut from whole data. c, Comparison between ideal current output and real current output (whole data).

Extended Data Fig. 8 Experimental results and simulation for the MSNet demonstration.

a, Accuracy and Loss curves from experiment (darker red and blue) and simulation (lighter red and blue), respectively. b, Measured and simulated weight maps of critical epochs (10, 16, 22, 28, 37, and 57). c, Inference result with representative inputs of six letters. This figure shows an example of, from left to right, written words ‘s–p–a–r–s–e’, features of conv1 layer, conv2 layer and maxpooling layer, classification output of FC layer, and finally the result of recognized words.

Extended Data Fig. 9 The Simulation platform and results.

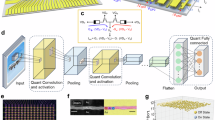

a, The modified version of hierarchical chip architecture in NeuroSim for SPNN. b, Size definition of a tile, a PE, and an array. c, Hardware-level definition of granularity. d, Accuracy curves of training process for five cases: No pruning, Block-wise, Vector-wise, Element-wise, and Index-free. e, Size, mapping and sparsity parameters of sparsified VGG-8 Net. Panel a adapted with permission from ref. 46, IEEE.

Extended Data Fig. 10 Simulation with non-idealities and differential pairs.

a-c, Extraction of non-idealities for NeuroSim simulations including a typical multistate curve providing the nonlinearity (a), device to device variation of nonlinearity (b) and cycle to cycle variation of delta weight during updating (c). d, Training process with non-idealities for three cases: No pruning, Element-wise, and Index-free. e, Accuracy, latency and energy enhancement of index-free hardware w/o and w/ non-idealities, compared with traditional SPNN. f, The mapping schematics of weight map and sparsity map, and the structure inside the unit cell when deploying differential pairs. g, Sparse training of VGG-8 Net based on single device w/o noise, w/ noise, and differential pair w/ noise. h, Accuracy, latency and energy enhancement of index-free hardware w/o and w/ differential pairs, compared with traditional SPNN.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Video 1

The whole process of sparse training on hardware. The key components include the sparsity map and weight map (in the top left corner), an instance of input data and output images (in the bottom left corner) and the training curves of accuracy, loss and sparsity (on the right) for all epochs.

Supplementary Video 2

Visualization of 3D loss landscape of all epochs during the whole sparse training. The position of the viewport ‘camera’ is defined by an elevation of 15° and an azimuth of −60°. Of note, the axes α and β are randomly generated direction vectors to visualize the high-dimensional loss space (refer to Methods for more details).

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Ning, H., Wen, H., Meng, Y. et al. An index-free sparse neural network using two-dimensional semiconductor ferroelectric field-effect transistors. Nat Electron 8, 222–234 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-024-01328-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-024-01328-4

This article is cited by

-

Adaptive spatial-temporal information processing based on in-memory attention-inspired devices

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Mutual promotion of triboelectric nanogenerators and field-effect transistors towards the IoT

Nature Reviews Electrical Engineering (2025)