Abstract

In utero hematopoietic cell transplantation (IUHCT) utilizes fetal immune tolerance to achieve durable chimerism without conditioning or immunosuppression during a unique window in fetal development. Though donor cells have been observed within the nervous system following in utero injection, the timeline and distribution of cellular trafficking across the blood-brain barrier following IUHCT is not well understood. We injected 20 × 106 adult bone marrow mononuclear cells intravenously at gestational age (GA) 12–17 days and found that donor cells were maximally concentrated in the brain with treatment between GA 13–14. Donor cell engraftment persisted within the brain at every timepoint analyzed and concentrated within the hindbrain with significantly more grafted cells than in the forebrain. Additionally, transplanted cells terminally differentiated into various nervous system cellular morphologies and also populated the enteric nervous system. This study is the first to document the timeline and distribution of donor cell trafficking into the immune-protected nervous system and serves as a foundation for the application of IUHCT to treat neurogenetic diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In utero hematopoietic cell transplantation (IUHCT) draws upon current clinical techniques of fetal intervention, exploiting the normal sequence of hematopoietic development to facilitate donor cell engraftment prior to the development of the fetal immune system without myeloablative conditioning or immunosuppression and with minimal risk of rejection1,2. Transplantation of blood cells before birth is a potential method for treatment of a wide variety of congenital disorders but has been primarily explored as a potential therapy for hematopoietic disease, including hemoglobinopathies and immune deficiencies3. Early bone marrow transplantation (BMT) is an important component of treatment for neurogenetic diseases such as lysosomal storage diseases (LSD). Recent work has identified promising combination therapies, in which BMT is a key component4,5,6. However, the toxicity associated with early postnatal BMT not only limits clinical applicability, but also constrains the timing of other important parts of this therapeutic approach, including gene therapy and enzyme replacement therapy (ERT). Donor cells have previously been shown to engraft successfully into fetal liver, spleen, and other abdominal viscera following IUHCT7,8. However, there has been no study to systematically evaluate trafficking of cells across the blood-brain barrier (BBB). While it is known that the murine BBB is functional by E15.5 to some degree9, it is unknown whether IUCHT can deliver cells into the central nervous system (CNS) after this gestational time point. While several previous studies have demonstrated amelioration of disease, we sought to systematically evaluate CNS engraftment patterns and determine the most appropriate timing for CNS-directed cell therapy in utero10,11. Though other studies have attempted IUHCT in LSD animal models using intrahepatic injection, ours is the first to systematically examine trafficking of donor cells across the BBB in a time-dependent fashion and to use the more efficient intravascular route of delivery which would be required for clinical translation7,12.

We have therefore sought to (1) characterize trafficking across the BBB over a range of gestational ages, (2) determine the fate of engrafted cells within the nervous system and (3) evaluate the optimal timing for introduction of cells into the nervous system, providing comprehensive understanding regarding the therapeutic potential of this approach for a wide range of LSD and/or neurodegenerative diseases. This study is the first to evaluate CNS engraftment in a time-dependent fashion during the period of gestation throughout which IUHCT would be feasible and to systematically analyze donor cell morphology within the CNS. Additionally, this is study is also unique in its use of volumetric analysis to quantify levels of engraftment in the brain after IUHCT. The ability to engraft adult marrow-derived stem cells within the CNS via IUHCT alone would have a transformative effect on the treatment of LSDs and other congenital neurodegenerative conditions, the possibility that such cells could terminally differentiate into neurons or glial cells offers groundbreaking potential to drive adult-derived stem cells down this pathway.

Results

Identification of donor-derived cells and their morphology within the CNS

Previous studies have documented the engraftment of donor-derived cells in multiple tissues as a result of early neonatal or in utero transplantation13. However, only one other study has demonstrated donor-derived cells within the CNS, using donor cells of fetal liver origin to demonstrate long-term engraftment of microglia following intrahepatic injection at E14.512. Given this limited information regarding the presence of transplanted cells within the brain following fetal injection at a single gestational age, we sought to investigate whether delivery of donor cells in utero could yield a more robust long-term presence of engrafted cells in the CNS throughout a wider treatment window.

We performed time-dated mating of BALB/cJ mice for 24 h, followed by injection of adult bone marrow (BM) between GA 13 and 15 (E13 and E15). The use of E13 to E15 was chosen to evaluate an initial window for the introduction of cells into the CNS while the BBB is decreasing in permeability14. Fetuses were injected via the vitelline vein with 20 × 106 bone marrow mononuclear cells (BM-MNC) harvested from at least 8-week-old C57BL/6-Tg(UBC-GFP)30Scha/J (B6-GFP) mice7 (Fig. 1). In these initial experiments, we found peripheral blood chimerism ranging from 0.86–98.7% and fetal survival among these litters was 31.1%.

Mice underwent time-dated mating for 24 h, were then injected with 20×106 LDMC of BM form adult B6-GFP mice at gestational ages 12–17, analyzed for peripheral blood chimerism at wean, then terminally harvested and brain analysis performed at ages 1, 3, 6, 9, or 12 months of age. Image created in BioRender®.

The use of green fluorescent protein (GFP) expressing mice as a donor source allowed for post-injection tracking of transplanted cells into a non-GFP expressing recipient. Brain tissue was harvested after saline perfusion and analyzed with fluorescent stereomicroscopy (Fig. 2), revealing an intense GFP signal. This initial analysis was limited to the evaluation of the parenchymal surface, and demonstrated diffuse engraftment of donor cells.

Inferior cerebellar views of brains in GFP (488 nm excitation) channel a un-injected control mouse (×25); b E13-treated mouse harvested at 9 months of age demonstrates intense GFP signal in sulci and meninges (×50); c E13 brain harvested at 3 months of age demonstrates more distinct cellular components (×50). d Increased magnification (×138) reveals superficial parenchymal GFP signal, as well as significant meningeal engraftment at all gestational ages studied.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining of the brains for GFP using an immunoperoxidase method revealed donor-derived structures with several different morphologies, including those resembling Purkinje cells (Fig. 3a, b), microglia (Fig. 3c), astrocytes (Fig. 3d) as well as morphologically undifferentiated cells (Fig. 3e). There was a predominance of GFP+ cells within the hindbrain, where Purkinje and glial morphologies were observed, as well as a high concentration of GFP+ cells along the ventricles and meninges. However, the most predominant cell type was a large round, intraparenchymal cell that was not associated with blood vessels, ventricle, nor meninges (Fig. 3e).

All images at ×20: a, b cells within the cerebellum with the characteristic morphology of Purkinje cells, c occasional cells of a different glial morphology, likely microglia, d cells with an astrocyte morphology, e more prominent within the brainstem are small clusters of undifferentiated donor-derived cells, and f intense GFP staining is also evident within the brain meninges.

To further investigate this, the treatment window was widened to E12-17, and brain tissue was stained immunofluorescently for GFP (Fig. 1). Mice treated with IUHCT were perfused with saline at the time of harvest at months 1, 3, 6, 9, or 12 months of age, fixed with 4% PFA for 24–48 h, cryopreserved with 30% sucrose containing 0.05% azide, separated into forebrain and hindbrain, then sectioned on a freezing microtome at 40 µm.

Primary staining with rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP antibody revealed multiple CNS cellular subtype morphologies. Donor-derived brain GFP+ cells are demonstrated in Fig. 4. GFP+ cells with the characteristic Purkinje neuron appearance of dendrites were evident in multiple specimens of cerebellum (Fig. 4a, b). Figure 4c, d demonstrates cells with bipolar neuron features. However, the most evident cell subtype was a round undifferentiated morphology (Fig. 4e, f), as was previously shown in immunoperoxidase staining. Additionally, there was significant staining outside of the brain parenchyma along the meninges and ventricles (Fig. 4g, h). Similarly, there were many GFP+ cells of microglial and astrocytic morphologies evident throughout multiple specimens (Fig. 4i–l).

Characterization of cell fates of donor-derived cells within the CNS

Having verified that GFP+ cells existed within the CNS with multiple cellular morphologies, by staining in a non-overlapping red (546 nm excitation) channel, we shifted the immunostaining strategy to stain for GFP in the green channel (488 nm), and sequentially co-stained for specific markers of cellular phenotype in the 546 nm channel to look for potential colocalization with GFP (antibody list in Supplementary Methods).

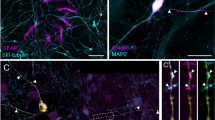

Co-localization of GFP immunoreactivity with a wide variety of CNS-specific markers confirmed the cellular identities of GFP+ cells as being donor-derived microglia, meningeal macrophages, as well as astrocytes (Fig. 5a–d). The majority of the glial cells existed in and around the meninges, ventricles, and blood vessels. Intraparenchymal engraftment was demonstrated in multiple locations, in multiple samples, across all gestational ages studied (E12-E17). Each of the co-stains in Fig. 5 was performed in at least three separate animals. Purkinje neurons were by far the most prevalent donor-derived neuronal cell sub-type with cellular bodies and numerous dendrites visible (Fig. 5e, f). With both cell body and projections expressing donor-derived protein, the potential for cross-correction to surrounding cells is high. Although the engraftment had an apparent concentration within the hindbrain, donor-derived neurons were seen within the cortex as well. Cortical neurons stained positively with Neu-N, with their cell bodies showing strong co-localization with GFP (Fig. 5g). The undifferentiated cell previously described demonstrated co-expression of SOX-2 (Fig. 5h). SOX-2 expression indicates progenitor cells within the CNS with progression to neuronal differentiation15. The significance of these progenitor cells is strengthened by the multitude of other cellular morphologies.

a Iba-1-positive microglial cell within the distal brain stem; b highly engrafted Iba-1-positive meningeal macrophages; c GFAP-positive possible radial glial cell; d GFAP-positive astrocytes adjacent to a blood vessel with nearby glial appearing cell right inferiolateral plane; e, f multiple calbindin-positive Purkinje neurons with both cell body and dendritic trees; g ×40 magnification of engrafted neuron demonstrates co-staining with Neu-N-positive neurons; h ×20 magnification shows several of the previously demonstrated round undifferentiated cells as SOX-2-positive progenitor cells.

Donor-derived cells terminally differentiate into post-mitotic neurons in CNS

The presence of GFP+ cells in the CNS could potentially be the result of donor cells fusing with host cells, rather than the differentiation of donor cells into neurons or other cell types. To investigate whether donor hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) are truly capable of differentiating into cells outside of the hematopoietic lineage, we utilized an all-male bone marrow donor source with analysis of a female recipient with 14.6% chimerism at one month of age. The brain was stained with RNAScope® probes (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Newark, CA, USA) for GFP, Sex-determining Region Y (SRY), and RNA Binding Fox-1 Homolog 3 (RBFOX3). SRY is an intranuclear gene that is unlikely to be expressed as the result of cellular fusion, but rather a cell whose nucleus contains the DNA of the male donor16. RBFOX3 produces the neuronal nuclei (NeuN) antigen that has been widely used as a marker for post-mitotic neurons17.

Multiple cells within the CNS were found to co-express GFP, Sex-determining region Y (SRY) and RNA Binding Fox-1 Homolog 3 (RBFOX3) (Fig. 6). RBFOX3-expressing cells containing nuclei from the male donor provide strong evidence that donor cells trafficked across the BBB are indeed capable of differentiation into neuronal subtypes within the CNS17. RNA-scope analysis demonstrated co-expression of GFP, SRY, and RBFOX3 in the cortex and cerebellum. The co-expression of these intranuclear cellular markers indicates donor-derived neuronal fate mapping, rather than cellular fusion.

Donor-derived cells differentiate into neurons within the ENS

The enteric nervous system (ENS) forms as the result of neural crest-derived cell migration in a craniocaudal direction18. By E14, murine neural crest migration has completed, resulting in neuronal population of the ENS19. Previous studies have demonstrated re-population of rectal ganglia where aganglionosis was previously present20, with other work utilizing isogenic transplants21. Within this study, three mice were injected with 20 × 106 LDMC at E14 with chimerism ranging from 38–94%. Terminal analysis at 1 month of age was performed with saline perfusion before harvest of the bowel from pylorus to distal rectum. Muscularis and mucosa sections of duodenum, ileum, and colon22 were stained for HuC/HuD23, Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP)24, and GFP in order to evaluate neurons, glia, and donor-derived cells, respectively.

Scattered donor-derived cells that co-localized with HuC/HuD+ neurons were present throughout the bowel of all mice analyzed following IUHCT at E14, albeit not densely distributed (Fig. 7a–c). Among the surveyed samples there were not observable examples of engrafted glial cells (Fig. 7d). In comparison to the CNS, donor-derived neuronal cells within the ENS were less common. However, their potential to cross correct adjacent diseased cells makes their potential translational ability potentially important25,26.

a Proximal small bowel (duodenum) demonstrates rare co-localization with HuC/HuD+ neurons (white arrows) within the ENS; b colonic sample from another mouse shows several HuC/HuD+ neurons that are engrafted); c colon sample from another mouse also demonstrates a few donor-derived neurons that co-express GFP and HuC/HuD; d additional stains of distal small bowel (ileum) show a glial network (GFAP) that is not donor-derived.

Quantification of donor-derived cells in the CNS across gestational ages

After demonstrating that IUHCT allows multi-lineage donor cell engraftment within both the central and enteric nervous systems, we next sought to identify the ideal timing of injection to optimize CNS engraftment. Mice were treated with IV IUHCT across gestational ages 12–17 with terminal harvest of tissues at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months to study effects of both gestational age and longitudinal degradation/expansion of engrafted cells within the CNS, as depicted schematically in Fig. 3. Survival in the extremes of this treatment window was significantly decreased, thus sample sizes were smaller in E12 and E17, as shown in Table 1. Mice were bled at the time of wean and monthly thereafter to determine peripheral blood (PB) chimerism by flow cytometry using CD45 APC7.

GFP+ cell count was normalized to a cubic millimeter by use of a Cavalieri volume estimator to objectively compare engraftment across gestational ages and regions of the brain27,28. Regions were defined as forebrain and hindbrain by separation of analyzed tissue at the cerebellopontine angle (Supplementary Fig. 3). Anatomically, this allowed for comparison of the cortex (forebrain) and cerebellum (hindbrain)29. Though this experiment was not powered to detect statistical significance between gestational ages, the peak total cellular concentration reached in our experiments with treatment at E13 and E14 (Table 2 and Fig. 8a). Injection at E12 and E17 yielded the lowest concentrations of cells within the CNS. The anatomic pattern of donor cell engraftment was consistent across all injection timepoints, with cells concentrated within the hindbrain as compared to the forebrain (paired t-test, p < 0.0001) in a ratio of 1.83 (95% CI = 1.33–2.51) (Fig. 8b, c).

a Violin plot of total CNS GFP+ cells/mm3 as compared to the gestational age at the time of injection. Peak cell concentrations reached in E13–E14 b FB and HB concentrations for each gestational age (mean with SD), with E13–E14 once again being the peak gestational age concentration; c GFP+ cellular concentrations were much higher within the HB as compared to FB (all samples across all gestational ages, paired t test, p < 0.0001, plotted as mean with SD); d–f there was no relationship between either the lifetime average PB chimerism or the chimerism at the time of harvest with regard to the cell concentration, without trend when analyzed by gestational age at the time of injection. g Analysis of cell concentration over time showed the highest level of cells present at 12 months of age (Kruskal–Wallis one way ANOVA, p = 0.0236 as compared to nadir at 6 months, plotted as mean with SEM); h PB chimerism decreased over time (mean with SEM). Linear trend ANOVA revealed a decrease of 1.85% each month. i There was a marked increase in peripheral blood chimerism with later gestation treatment, which reached statistical significance in each group (paired one-way ANOVA, plotted as mean with SEM). FB forebrain, HB hindbrain, PB peripheral blood. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. All source data for (a–c, g) can be found in Supplemental Data 1. All source data for (d–f, h, i) can be found in Supplemental Data 2.

Surprisingly, there was no relation between the peripheral blood chimerism of the mouse and its CNS cellular concentration. Regardless of average lifetime chimerism or chimerism at the time of harvest, donor cell concentration within the CNS remained within a relatively narrow range in both hindbrain and forebrain (Fig. 8d–f), suggesting that the underlying mechanism for transport of cells into the CNS reached a saturation point: regardless of the level of chimerism, only a limited number of cells could be trafficked across the BBB. Alternatively, CNS chimerism is not subject to variation in the non-progenitor cell population seen in peripheral blood, which results in marked variation in chimerism.

Analysis of cellular concentration with regard to harvest time point revealed a peak concentration of cells when mice were harvested at 12 months of age. An ANOVA was performed comparing each group, with the only statistically significant finding being the nadir of GFP+ cellular concentration at 6 months as compared to the peak at 12 months of age (Fig. 8g). Between these two points, there is a clear trend toward increased CNS chimerism with increasing age, suggesting that engrafted donor cells undergo measurable expansion during this period, despite the decay in peripheral blood chimerism at a rate of 1.85% each month (ANOVA linear trend analysis, p = 0.0005) (Fig. 8h). Moreover, this trend of initial decay may indicate the presence of cells within the CNS that undergo cell death, leaving only progenitor cells as the durable cell population.

Assuming that the blood-brain barrier is indeed mature after birth in these otherwise healthy and non-conditioned hosts9,30, the increase in donor-derived cells within the CNS through postnatal life suggests that donor progenitor cells continue to expand within the CNS after initial engraftment.

Last, the peripheral blood chimerism levels increased with injection at later gestational ages (Fig. 8i). This increase was statistically significant by paired, one-way ANOVA (P < 0.05 for all groups), though the concentration of GFP+ cells within the CNS did not correlate with increased gestational age. This was most likely due to opposing trends of increasing chimerism with increasing gestational age with decreasing BBB permeability over time9,31 (Supplementary Fig. 5). The crossover point that allows for sufficient trafficking of cells across the BBB while also reaching saturation of the underlying transport mechanism appears to be between E13–E14.

Discussion

This study is the first to systematically evaluate cellular trafficking of donor-derived cells across the blood-brain barrier following IUHCT and confirms not only the engraftment but also the differentiation and expansion of these donor stem cells. Our findings provide compelling evidence of IUHCT’s potential for the treatment of neurogenetic diseases and can serve as the basis for further investigation into the mechanism by which an easily obtainable adult donor hematopoietic stem cell may be induced to differentiate into neuronal cell types that are otherwise highly resistant to regeneration32,33. The cellular delivery techniques utilized within this study are within the realm of current clinical practice, with human clinical trials underway for IUHCT34,35, resulting in tremendous translational potential for these findings. The treatment window utilized in this study represents a feasible treatment window in humans: murine gestational age E12–E17 most closely correlates with early to mid-gestation (12–15 weeks) in humans36.

By delineating two separate timelines for BBB permeability and cellular trafficking, a window for intervention becomes evident, allowing cells to be introduced into the CNS for disease prevention, rather than palliation. IUHCT precedes any other form of treatment by weeks, if not months, in humans. Many neurogenetic diseases cannot be treated, if at all, until the early postnatal period, with treatment usually consisting of a bone marrow transplant and its obligatory myelosuppression. With earlier treatment, as well as prevention of disease, IUHCT could allow for a more effective therapy for a multitude of neurogenetic diseases before the development of the fetal immune system. By allowing for early introduction of transplant, adjuncts for subsequent treatment become possible in the form of booster transplant or gene therapy postnatally, as these treatment modalities also show promise37. This allows for a cadre of therapies to treat a previously untreatable and terminal disease, with pairing of treatments possible in the form of ex vivo modified injectate38. Such an approach would allow for maternal donor source modification of progenitor cells that could over-express otherwise deficient enzyme in order to rescue deficient cells prior to damage.

The timing of IUHCT has previously been standardized to E14 in most studies7,12. Peak engraftment of donor cells within the CNS was seen following E13–E14 injection, but engrafted cells were also seen in the CNS before and after this gestational point (E12–17). The drop-off in CNS cell concentration after E14 fits with the known patterns of BBB permeability functionality at E15.59, if not even earlier at E14.531. Our results also suggest that cells do not merely diffuse across an immature BBB, but rather that transport mechanisms may be required to traffic cells into the CNS. Saturation of these mechanisms would explain the observed consistency of CNS engraftment across a wide range of PB chimerism. Subsequent work to delineate mechanistic aspects of this transport mechanism has the potential to unlock a multitude of applications for neuro-regenerative medicine, as our results demonstrate terminal differentiation of multilineage CNS populations within a fetal brain as the result of transplant of adult bone marrow.

IUHCT consistently delivers cells to the meninges and ventricles, which should provide significant production of enzyme within the cerebrospinal fluid for treatment of lysosomal storage disorders, as many soluble proteins can be taken up by the mannose-6-phosphate receptors and trafficked to the lysosome by a process called “cross-correction”11,39. Moreover, the presence of various cellular morphologies within the CNS suggests that donor-derived cells would function in their usual respective roles. These cellular subtypes were confirmed with co-staining for cell-specific markers. Most notably, the presence of stem cells within the CNS, even late in life suggests ongoing replication, as SOX-2+ progenitor cells have the capacity to self-renew or terminally differentiate into various cell types40,41. This capacity for self-renewal is further evidenced by our observation that cellular concentrations of GFP+ CNS cells were highest at the late life harvest time point of 12 months, suggesting that progenitor cells present within brain begin to expand despite declining peripheral blood chimerism.

SOX-2 has been well described as a marker of pluripotency42,43, and the observed expansion of SOX-2-expressing adult stem cell-derived structures within the CNS following IUHCT provides hope for translation in neurogenetic disease and beyond. Our data demonstrate that donor HSC are effectively trafficked across the BBB following IUHCT. Though the undifferentiated round cells seen most predominantly within the brain parenchyma will not necessarily adopt exclusively neuronal fates, the expression of various other cellular markers by these cells denotes their broad ability to terminally differentiate. This fate mapping is likely related to SOX-2 expression, which is linked to the donor-derived cell’s capability for cellular expansion. Donor cell expansion within the CNS increased with advancing age, independent of and discordant from peripheral blood chimerism. Bone marrow engraftment and CNS integration appear to evolve separately over time, suggesting that the HSC-derived populations within the BM and the CNS are fundamentally different and lending support to the observed evidence of neuronal differentiation. Additional work to elucidate these differences could increase transplant efficiency and promote development of postnatal therapies for neurodegenerative diseases. Subsequent projects could reveal these pathways using single cell analysis to clarify the signaling pathways and gene expression involved in fate mapping44. By understanding the signaling involved in neuronal differentiation of this transplant modality, further applications of transplant could be utilized outside of the fetal context to promote neuro-regeneration. The reverse engineering of the engraftment phenomenon illustrates the potential for translation beyond in utero transplant by utilizing growth factors to steer a transplant toward an end target.

Furthermore, co-expression of GFP, SRY, and RBFOX3 in the cortex and cerebellum provides strong evidence for the differentiation of presumably committed HSCs into post-mitotic neurons. Given the transplant model utilized, these structures are the result of a male donor HSC which has terminally differentiated into a neuronal cell in the brain of the female transplant recipient.

Terminal differentiation into neurons has not been demonstrated from the use of an adult donor source in utero, potentially providing a novel mechanism for the regeneration of pathologic cell populations. Given that cellular gene expression changes based on the setting in which the cell exists, growth factors could be altered to steer a transplant to a desired effect.

Given the known reliance of microglial distribution on the circulatory system45, it is perhaps unsurprising that an IV delivery of BM would yield a wide distribution of cells. Though prior studies have demonstrated the presence of donor-derived microglia using a fetal donor cell source, the ontologic origins of microglia are distinct from other cells within the CNS46. Our results not only confirm the findings of microglial engraftment following IUHCT, but do so using an adult BM-derived donor inoculum and an intravascular injection technique which are readily translatable into clinical application. Moreover, this study is the first to demonstrate donor-derived neurons, Purkinje cells, and astrocytes, suggesting not only that donor cells can traffic across the BBB at a wider range of gestational ages than predicted based upon prior understanding of BBB permeability47, but also that these adult-derived donor HSCs can differentiate into multiple lineages and cell types in the fetal CNS environment. Purkinje neurons expressed high levels of GFP both within the cell body, as well as their abundant dendritic projections. These findings, paired with the co-expression of SRY and RBFOX3, support that intranuclear expression of the protein in donor-derived cells would allow for durable and definitive engraftment following IUHCT. The unique potential of in utero transplantation is further evidenced by the presence of donor-derived cells within the enteric nervous system, another immunoprotected niche otherwise unreachable with bone marrow transplantation.

Although the observed concentration of engrafted cells was relatively low, multiple studies have shown that a low level of engraftment can provide translational benefit through tolerance of an otherwise absent enzyme, as well as rescue of soluble enzyme-deficient cells12,48,49. Though the most prominent cell type observed was an undifferentiated cell which may not have neuronal capacity, these cells would still be expected to produce and secrete enzyme. Because of the cross-correction observed in many LSDs, these undifferentiated cells would therefore possess excellent therapeutic potential, in coordination with the specific donor-derived neuronal cells observed. If, in fact, these undifferentiated cells could be induced to terminally differentiate, their therapeutic potential might be further amplified. In this study, which is the first to demonstrate multilineage donor-derived cells and progenitors within the CNS, the fetal milieu likely encouraged such neuronal differentiation. Not only might subsequent identification of the specific factors leading to this fate mapping further expand potential applications for IUHCT, but it could also have paradigm-changing implications in the field of neuronal regeneration.

Methods

Data availability statement

All data regarding chimerism and CNS engraftment are retained within a database secured by the Washington University in St. Louis School of Medicine. Numerical source data for graphs and figures within the manuscript can be found in Supplemental Data 1 and 2 files. All histologic images, in addition to others not within the manuscript, are available upon request.

Mice

All experimental mice are derived from breeding colonies maintained within our animal housing facility. BALB/cJ and C57BL/6-Tg(UBC-GFP)30Scha/J (B6-GFP) colonies both originated from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Approval for the use of these mice was obtained from the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (Institutional protocols 20170217 and 20170236).

Injection technique

For all experiments, bone marrow is transplanted prior to birth in a competitive system without conditioning. In preparation for IUHCT, male BALB/cJ mice were singly housed and paired with female BALB/cJ mice for a 24-hour period in order to achieve time-dated mating. Donor bone marrow (BM) was harvested from the humeri, femora, and tibiae of adult B6-GFP mice of both sexes, unless otherwise noted. The presence of GFP allows for post-injection cell tracking. The cellular layers are separated using Ficoll Paque (GE Healthcare BioSciences, Marlborough, MA), then washed twice with phosphate buffered saline (PBS) to obtain bone marrow mononuclear cells (BM-MNC). Harvest and injection take place on the same day.

At gestational time points between 12 and 17 days (E12–E17), dams found to be pregnant on examination underwent anesthetic induction with isoflurane, then subsequent maternal laparotomy, followed by exteriorization of the uterine horns and a one-time intravenous (IV) injection of GFP+ donor BM-MNC into the vitelline vein (Supplementary Fig. 1). Injections are performed with a pulled glass needle of ~80–90 microns in diameter, using a Narishige IM300 nitrogen-driven micro-injector (Amityville, NY) under visualization with a dissecting microscope. To maximize potential engraftment, 20 × 106 donor cells are administered to each fetus in 20 µL of PBS, which has been shown to be a safe and feasible volume7. The fetuses are then returned to the maternal abdomen until delivery at term, after which pups are placed with a foster mother (BALB-cJ mice) within 24 h of delivery to prevent transfer of donor-specific maternal antibodies through breastmilk50.

Chimerism

Chimerism was defined as the percentage of cells that were CD45+/GFP+(Supplementary Data 2) To determine this percentage, flow cytometry was used either monthly or at time of terminal harvest. For monthly chimerism checks, mice underwent submandibular “cheek” bleeds. Blood was collected in 3 mL of PBS (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA, USA) + EDTA (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). Samples were centrifuged for 5 min, and the supernatant discarded. Remaining plasma and red blood cells (RBC) were lysed for 5 min with RBC lysis buffer (G-Biosciences, St. Louis, MO, USA). The lysis reaction was stopped by the addition of ice-cold PBS + EDTA. Samples were centrifuged again for 5 min. The pellet was re-suspended in 100 µL of FACS staining buffer (Rockland Immunochemicals, Limerick, PA, USA) and stained with APC rat anti-mouse CD45 (BD Pharmingen, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) for 30 min. Cells were washed with PBS, centrifuged for 5 min and resuspended in 500 µL of PBS. Samples were analyzed in conjunction with unstained BALB/cJ, CD45 APC stained BALB/cJ, and B6-GFP control specimens on a FACSCalibur3 (Becton-Dickson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). Using FlowJo software (FlowJo, LLC, Ashland, OR, USA), gating was performed around leukocytes, and the percentage of cells that were both CD45 and GFP positive was used to determine the percentage chimerism (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Tissue sectioning

When treated animals reached the appropriate timepoints for harvest, they were terminally harvested. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, then cardiac puncture was done after sternotomy in order to collect peripheral blood samples. Mice were then perfused with 10–20 mL of PBS until the liver paled in color. The brain was then dissected out and placed in 4% para-formaldehyde (PFA) fixative (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) in PBS, which was made prior to harvest. After 24–36 h of fixation, the specimens were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) with 0.05% sodium azide (Sigma–Aldrich) for 48 h. Specimens were sectioned once the sample was no longer buoyant in the sucrose solution. The brains were divided at the cerebellopontine angle to separate forebrain from hindbrain (Supplementary Fig. 3). They were then serially sectioned in the coronal plane at 40 µm on a Microm HM430 freezing microtome (Microm International, Germany) and placed in an antifreeze cryoprotectant solution (Tris-buffered saline/30% ethylene glycol/15% sucrose/0.05% sodium azide) solution for long-term storage prior to their respective staining.

Tissue staining

Initial immunohistochemical staining against GFP was completed according to previously described protocols51. Endogenous peroxidase was inhibited by blocking sections with 1% H2O2 in TBS for 30 min. Sections were then rinsed three times with TBS, after which they were blocked with 15% normal goat serum (NGS) (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Sections were then rinsed again with TBS three times and subsequentially incubated with rabbit anti-mouse GFP at 1:10,000 in a 10% NGS in 2% TBS-T solution for 2 h. Before proceeding, sections were rinsed in TBS again. They were then incubated for 2 h in a 1:1000 solution of avidin-biotin complex kit (ABC, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Prior to the last staining step, sections were rinsed in TBS again. They were then incubated in 3,3’-diaminobenzidine (DAB) solution at 0.05% concentration with 0.01% H2O2 for roughly 10 min52. The DAB reaction was stopped with the addition of ice-cold TBS, after which the sections were rinsed and mounted onto chrome-gelatine-coated Superfrost Plus slides (VWR, Poole, UK) and air dried overnight. They were then dehydrated in ascending concentrations of ethanol (70–100%), cleared with xylene before finally cover-slipping with DPX mounting media (VWR). All tissue was stained with Balb/cJ as the negative control and B6-GFP as the positive control.

For immunofluorescent staining, tissue staining was completed as has been described by Nelvagal et al.53. In brief, sections were slide mounted and air dried on SuperFrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for 30 min. They were then blocked with 15% normal goat serum (NGS) in 4% TBS-T (pH = 7.6). They were then incubated in the primary antibodies (rabbit anti-mouse GFP antibody, ab290, abcam®, Waltham, MA, USA, Table 3) at 1:1000 in 10% NGS in 4% TBS-T for 2 h, washed three times with TBS, at which point they underwent incubation in appropriate secondary antibody (Alexa FluorTM Goat anti-Rat 488 and 546, goat anti-rabbit 546 or goat anti-human 546, Invitrogen) at 1:200 concentration. The secondary antibody channel was chosen in 546 nm to eliminate the possibility of inherent GFP fluorescence confounding staining results. Slides were washed again three times with TBS, then treated with TrueBlack 1:20 in 70% ethanol (Biotium, Fremont, CA) to eliminate any background and/or autofluorescence. Slides were rinsed with TBS three times and coverslipped with DAPI Fluoromount G (Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL, USA).

In situ hybridization (ISH) was completed with the use of RNAScope® probes and manuals54. All reagents were RNAScope-specific unless mentioned otherwise. A female mouse who received an all-male donor transplant was terminally harvested at 3 months. Harvest took place according to previously described technique, except that the mouse was perfused with PBS alone, rather than PBS + EDTA. Brain specimen was fixed in PFA overnight, then placed in increasing concentration sucrose solutions of 10, 20, and 30%. Solutions were exchanged when the specimen was no longer buoyant. After equilibration within the 30% sucrose solution, it was frozen in O.C.T. Compound (Sakura, Torrance, CA, USA) on dry ice before being placed in a −80 °C freezer for storage. After equilibration at −20 °C for 1 h, it was then sectioned to 6 µm with sections mounted on SuperFrost Plus slides (Fisher Scientific) and air dried at −20 °C for 1–2 h. Slides were washed with PBS, then placed in a 60 °C oven for 30 min before cooling to room temperature. Slides were fixed again with 4% PFA for 15 min before proceeding to dehydration with 50% and 70% ethanol for 5 min each, with two final rinses in 100% ethanol for 5 min each. Slides were then air dried for 5 min before being placed in a 40 °C oven for 30 min. H2O2 was added at room temperature for 10 min before washing with deionized water twice. RNAScope® Retrieval Reagent was added to the slides while in a steamer for 5 min before washing in DI water. Slides were then washed in 100% ethanol for 3 min and dried at 60 C for 5 min. A hydrophobic barrier was made around the sections before Protease III was added with incubation for 30 min at 40 °C. Slides were washed with DI water before addition of a premade, pre-warmed probe mixture (40 °C for 10 min before cooling to room temperature). Incubation with RNAScope® probes (Advanced Cell Diagnostics, Newark, CA, USA) for GFP, Sex-determining region Y (SRY), and RNA Binding Fox-1 Homolog 3 (RBFOX3), took place at 40 °C for 2 h. Slides were rinsed in buffer for 4 min before incubation with AMP1 at 40 °C for 30 min. The same process was repeated for AMP2 and again for AMP3 but incubated for only 15 min. The HRP-C1 channel was developed for 15 min at 40 °C before washing with buffer, then adding secondary antibody. This process was repeated for HRP-C2 and HRP-C3, with all secondary concentrations at 1:1500 in Fluoroscein, Cy3.5 and Cy5.5 channels. DAPI was added at room temperature for 30 s before removal, then coverslipping with ProLong Gold Antifade mountant media (ThermoFisher).

For enteric staining proximal small bowel, distal small bowel, and colon/rectum were harvested in 6 cm segments. The bowel was then split along the mesenteric border and splayed into a planar fashion in 2 cm segments using pins and Sylgard 184 (Sigma–Aldrich®, St. Louis, MO, USA) covered petri dishes (Supplementary Fig. 4). The tissue was then fixed with 4% PFA before the muscularis and mucosa were separated under a dissecting microscope22. Muscularis and mucosa sections of duodenum, ileum, and colon were stained using a free-floating immunofluorescence protocol55 for HuC/HuD, Glial Fibrillary Acidic Protein (GFAP), and GFP (Table 3) in order to evaluate neurons, glia, and donor-derived cells, respectively.

Microscopy

Stereomicroscopy was performed with a Leica M205FA stereoscope equipped with DFC7000T digital color camera. All image collection was performed using Leica LAS X software (Leica Microsystems, Buffalo Grove, IL, USA).

Widefield and fluorescence microscopy was performed with Zeiss Axioskop 2 MOT (Zeiss, Germany) with either a Zeiss Axiocam 506 color (Zeiss) or Hamamatsu ORCA-Flash fluorescence camera (Hamamatsu Photonics, Japan). Images were collected and analyzed with Stereo Investigator (MBF Bioscience, Williston, VT) and ImageJ (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

RNAScope-stained slides were imaged with Zeiss LSM 880 at 40X with images processed in Zen Lite (ZEISS Microscopy, Jena, Germany).

Analysis

For each gestational time point (E12-E17), mice were harvested at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months of age in order to have a roughly equivalent number of mice in each group. Survival in E12 and E17 was limited, thus those groups are smaller in sample size. Working in batches, ~12 brains were stained at one time, then analyzed before proceeding to the next batch. This allowed for consistent stain intensity. Brain samples were separated into forebrain and hindbrain sections with every 36th section of forebrain and every 24th section of hindbrain analyzed.

Sections were then analyzed utilizing the software Stereo Investigator® (MBF Bioscience), and GFP+ cells were counted (Supplementary Data 1). Cells were excluded if they were associated with meninges, ventricles, or blood vessels in order to identify cells that were truly associated with the CNS. Each analyzed section was outlined in Stereo Investigator and volumetric analysis was performed using a Cavalieri volume estimator to standardize GFP cell counts to volume27,52.

Volumetric analysis

Using Stereo Investigator (MBF Bioscience), sections were outlined, and their respective intervals documented in the software. All sections were 40 µm, allowing for volumetric analysis. A Cavalieri estimator was utilized with a 200 µm grid spacing for all samples. The total number of GFP+ cells, in addition to the volume estimate for over-correction, was entered into an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). Given that the sections were only a sampling of the total specimen, the GFP+ cell count and volume were utilized in the below formulae to project an overall GFP+ cell concentration to volume, with a correction to mm3. Assuming that the evaluated sections encompass the anterior and posterior most portions of the brain, the section evaluation interval minus 1 was multiplied by the number of sections evaluated minus 1 in order to account for the first and last sections. This generated an assumed total number of sections which was then multiplied by the number of GFP+ cells yielded during manual counting. This result was the total number of GFP+ cells within the specimen. The Cavalieri volume estimator generated a volume corrected for OverProjection in order to account for errors in section outlining. This volume, in µm3, was converted to mm3 to bring numbers into a more easily manageable order of magnitude.

Statistical analysis

All data were statistically analyzed using GraphPad Prism for MacOS (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA). GFP+ cell concentrations were compared among gestational ages and among age at harvest using an unpaired, non-parametric ANOVA with Kruskal-Wallis multiple comparisons test. Forebrain and hindbrain concentrations were compared in a pooled fashion using paired parametric two-tailed t-test. Chimerism numbers were compared among gestational ages using a one-way ANOVA in an unpaired fashion. Chimerism numbers over time (months) were analyzed with a one-way ANOVA with linear trend test. Statistical significance was reached with p-value ≤ 0.05.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

References

Roybal, J. L., Laje, P., Vrecenak, J. D. & Flake, A. W. Use of manipulated stem cells for prenatal therapy. Methods Mol. Biol. 891, 169–181 (2012).

Antiel, R. M. et al. Acceptability of in utero hematopoietic cell transplantation for sickle cell disease. Med Decis. Mak. 37, 914–921 (2017).

Kreger, E. M. et al. Favorable outcomes after in utero transfusion in fetuses with alpha thalassemia major: a case series and review of the literature. Prenat. Diagn. 36, 1242–1249 (2016).

Hawkins-Salsbury, J. A., Reddy, A. S. & Sands, M. S. Combination therapies for lysosomal storage disease: is the whole greater than the sum of its parts? Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, R54–60, (2011).

Barker, J. E. et al. In utero fetal liver cell transplantation without toxic irradiation alleviates lysosomal storage in mice with mucopolysaccharidosis type VII. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 27, 861–873 (2001).

Massaro, G. et al. Fetal gene therapy for neurodegenerative disease of infants. Nat. Med. 24, 1317–1323 (2018).

Boelig, M. M. et al. The intravenous route of injection optimizes engraftment and survival in the murine model of in utero hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 22, 991–999 (2016).

Vrecenak, J. D. et al. Stable long-term mixed chimerism achieved in a canine model of allogeneic in utero hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood 124, 1987–1995 (2014).

Ben-Zvi, A. et al. Mfsd2a is critical for the formation and function of the blood-brain barrier. Nature 509, 507–511 (2014).

de Vasconcelos, P. & Lacerda, J. F. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for neurological disorders: a focus on inborn errors of metabolism. Front. Cell Neurosci. 16, 895511 (2022).

Gentner, B. et al. Hematopoietic stem- and progenitor-cell gene therapy for hurler syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 1929–1940 (2021).

Nguyen, Q. H. et al. Tolerance induction and microglial engraftment after fetal therapy without conditioning in mice with Mucopolysaccharidosis type VII. Sci. Transl. Med. 12, https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aay8980 (2020).

Bruscia, E. M. et al. Engraftment of donor-derived epithelial cells in multiple organs following bone marrow transplantation into newborn mice. Stem Cells 24, 2299–2308 (2006).

Blanchette, M. & Daneman, R. Formation and maintenance of the BBB. Mech. Dev. 138, 8–16 (2015).

Bylund, M., Andersson, E., Novitch, B. G. & Muhr, J. Vertebrate neurogenesis is counteracted by Sox1-3 activity. Nat. Neurosci. 6, 1162–1168 (2003).

Sinclair, A. H. et al. A gene from the human sex-determining region encodes a protein with homology to a conserved DNA-binding motif. Nature 346, 240–244 (1990).

Kim, K. K., Adelstein, R. S. & Kawamoto, S. Identification of neuronal nuclei (NeuN) as Fox-3, a new member of the Fox-1 gene family of splicing factors. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 31052–31061 (2009).

Lake, J. I. & Heuckeroth, R. O. Enteric nervous system development: migration, differentiation, and disease. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 305, G1–24, (2013).

Fu, M., Tam, P. K., Sham, M. H. & Lui, V. C. Embryonic development of the ganglion plexuses and the concentric layer structure of human gut: a topographical study. Anat. Embryol. 208, 33–41 (2004).

Liu, W., Wu, R. D., Dong, Y. L. & Gao, Y. M. Neuroepithelial stem cells differentiate into neuronal phenotypes and improve intestinal motility recovery after transplantation in the aganglionic colon of the rat. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 19, 1001–1009 (2007).

Hotta, R. et al. Isogenic enteric neural progenitor cells can replace missing neurons and glia in mice with Hirschsprung disease. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 28, 498–512 (2016).

Fu, M. et al. Retinoblastoma protein prevents enteric nervous system defects and intestinal pseudo-obstruction. J. Clin. Investig. 123, 5152–5164 (2013).

Phillips, R. J., Hargrave, S. L., Rhodes, B. S., Zopf, D. A. & Powley, T. L. Quantification of neurons in the myenteric plexus: an evaluation of putative pan-neuronal markers. J. Neurosci. Methods 133, 99–107 (2004).

Grundmann, D. et al. Enteric Glia: S100, GFAP, and beyond. Anat. Rec. (Hoboken) 302, 1333–1344 (2019).

Weinstock, N. I. et al. Macrophages expressing GALC improve peripheral Krabbe disease by a mechanism independent of cross-correction. Neuron 107, 65–81 e69 (2020).

Holley, R. J. et al. Macrophage enzyme and reduced inflammation drive brain correction of mucopolysaccharidosis IIIB by stem cell gene therapy. Brain 141, 99–116 (2018).

Garcia-Finana, M., Cruz-Orive, L. M., Mackay, C. E., Pakkenberg, B. & Roberts, N. Comparison of MR imaging against physical sectioning to estimate the volume of human cerebral compartments. Neuroimage 18, 505–516 (2003).

Kuhl, T. G., Dihanich, S., Wong, A. M. & Cooper, J. D. Regional brain atrophy in mouse models of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis: a new rostrocaudal perspective. J. Child Neurol. 28, 1117–1122 (2013).

Hannsjörg Schröder, N. M., Stefan Huggenberger. Neuroanatomy of the Mouse: An Introduction. 1st Edition: Springer International Publishing; 2020.

Saunders, N. R., Liddelow, S. A. & Dziegielewska, K. M. Barrier mechanisms in the developing brain. Front. Pharm. 3, 46 (2012).

Sohet, F. et al. LSR/angulin-1 is a tricellular tight junction protein involved in blood-brain barrier formation. J. Cell Biol. 208, 703–711 (2015).

Nagappan, P. G., Chen, H. & Wang, D. Y. Neuroregeneration and plasticity: a review of the physiological mechanisms for achieving functional recovery postinjury. Mil. Med. Res. 7, 30 (2020).

Cattaneo, E. & McKay, R. Identifying and manipulating neuronal stem cells. Trends Neurosci. 14, 338–340 (1991).

MacKenzie, T. C., David, A. L., Flake, A. W. & Almeida-Porada, G. Consensus statement from the first international conference for in utero stem cell transplantation and gene therapy. Front. Pharm. 6, 15 (2015).

Mackenzie, T. In utero hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for alpha-thalassemia major (ATM). ClinicalTrials.gov https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02986698 (2016).

Riley, J. S. et al. Regulatory T cells promote alloengraftment in a model of late-gestation in utero hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood Adv. 4, 1102–1114 (2020).

Rossidis, A. C. et al. In utero CRISPR-mediated therapeutic editing of metabolic genes. Nat. Med. 24, 1513–1518 (2018).

Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Society for maternal-fetal medicine special statement: beyond the scalpel: in utero fetal gene therapy and curative medicine. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 225, B9–B18 (2021).

Corado, C. R. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid and serum glycosphingolipid biomarkers in canine globoid cell leukodystrophy (Krabbe Disease). Mol. Cell Neurosci. 102, 103451 (2020).

Suh, H. et al. In vivo fate analysis reveals the multipotent and self-renewal capacities of Sox2+ neural stem cells in the adult hippocampus. Cell Stem Cell 1, 515–528 (2007).

Graham, V., Khudyakov, J., Ellis, P. & Pevny, L. SOX2 functions to maintain neural progenitor identity. Neuron 39, 749–765 (2003).

Zhang, S. & Cui, W. Sox2, a key factor in the regulation of pluripotency and neural differentiation. World J. Stem Cells 6, 305–311, (2014).

Shanak, S. & Helms, V. DNA methylation and the core pluripotency network. Dev. Biol. 464, 145–160 (2020).

Habib, N. et al. Div-Seq: single-nucleus RNA-Seq reveals dynamics of rare adult newborn neurons. Science 353, 925–928 (2016).

Ginhoux, F. et al. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science 330, 841–845 (2010).

Tay, T. L., Hagemeyer, N. & Prinz, M. The force awakens: insights into the origin and formation of microglia. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 39, 30–37 (2016).

Wu, Y. & Hirschi, K. K. Tissue-resident macrophage development and function. Front Cell Dev. Biol. 8, 617879 (2020).

Ihara, N. et al. Partial rescue of mucopolysaccharidosis type VII mice with a lifelong engraftment of allogeneic stem cells in utero. Congenit. Anom. 55, 55–64 (2015).

Donsante, A., Levy, B., Vogler, C. & Sands, M. S. Clinical response to persistent, low-level beta-glucuronidase expression in the murine model of mucopolysaccharidosis type VII. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 30, 227–238 (2007).

Merianos, D. J. et al. Maternal alloantibodies induce a postnatal immune response that limits engraftment following in utero hematopoietic cell transplantation in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 2590–2600 (2009).

Rahim, A. A. et al. In utero administration of Ad5 and AAV pseudotypes to the fetal brain leads to efficient, widespread and long-term gene expression. Gene Ther. 19, 936–946 (2012).

Cooper, J. D., Brooks, H. R. & Nelvagal, H. R. Quantifying storage material accumulation in tissue sections. Methods Cell Biol. 126, 349–356 (2015).

Nelvagal, H. R., Dearborn, J. T., Ostergaard, J. R., Sands, M. S. & Cooper, J. D. Spinal manifestations of CLN1 disease start during the early postnatal period. Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 47, 251–267 (2021).

Diagnostics, A. C. RNAScope(R) multiplex fluorescent reagent kit v2 assay. (2019). https://acdbio.com/system/files_force/USM-323100%20Multiplex%20Fluorescent%20v2%20User%20Manual_10282019_0.pdf?download=1.

Tu, L. et al. Free-floating immunostaining of mouse brains. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/62876 (2021).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the laboratory of Dr. Vanda Lennon, MD PhD for supplying the ANNA-1 antibody against HuC/HuD. Additionally, we would like the express our gratitude to Dr. Grant Kolar, MD, PhD and Caroline Murphy, BS for their assistance with the RNAScope staining. This work was funded by Children’s Discovery Institute Grant MI-II-2019-777 and the St. Louis Children’s Hospital Foundation PR 2017281.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.G. devised the research plan, carried out experiments, analyzed results, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed the manuscript. H.R.N. supervised experiments, devised the plan for analysis, and critically revised the manuscript. M.T., A.H., and K.S. carried out experiments. J.C. supervised experiments and critically revised the manuscript. J.V. devised the research plan, supervised experiments, analyzed results, and critically revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks John Stratigis, Adriana Seber and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Eirini Trompouki and Joao Valente. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grant, M.T., Nelvagal, H.R., Tecos, M. et al. Cellular trafficking and fate mapping of cells within the nervous system after in utero hematopoietic cell transplantation. Commun Biol 7, 1624 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06847-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-024-06847-6