Abstract

Dietary modifications to overcome infertility have attracted attention; however, scientifically substantiated information on specific dietary components affecting fertility and their mechanisms is limited. Herein, we investigated diet-induced, reversible infertility in female mice lacking the heterodimer of ATP-binding cassette transporters G5 and G8 (ABCG5/G8), which functions as a lipid exporter in the intestine. We found that dietary phytosterols, especially β-sitosterol and brassicasterol, which are substrates of ABCG5/G8, have potent but reversible reproductive toxicities in mice. Mechanistically, these phytosterols inhibited ovarian folliculogenesis and reduced egg quality by enhancing polycomb repressive complex 2-mediated histone H3 trimethylation at lysine 27 in the ovary. Clinical analyses showed that serum phytosterol levels were significantly and negatively correlated with the blastocyst development rate of fertilized eggs in women undergoing in vitro fertilization, suggesting that phytosterols affect egg quality in both humans and mice. Thus, avoiding excessive intake of certain phytosterols would be beneficial for female reproductive health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Infertility, defined as the inability to have a child after more than a year of regular unprotected sexual intercourse, is a global health problem that affects millions of peoples of reproductive age1. More than 15% of couples have infertility2. Of these, approximately 5% have anatomical, immunological, genetic, or endocrine causes, while the remainder are thought to be caused by environmental factors. To overcome infertility, an increasing number of couples are undergoing treatment using assisted reproductive technology (ART) over the years3. However, although ART has progressed through accumulated studies and clinical experience, the success rate of conception remains low, at approximately 30%3. To increase the success rate of ART, it is necessary to understand the mechanisms underlying infertility, particularly the influence of environmental factors.

Among environmental factors, dietary habits are thought to affect reproductive function. Recently, diversity in dietary habits has been driven by several factors, such as lack of time, which leads to increased consumption of prepared and processed foods, and personal choices to avoid meat consumption for religious, health, or animal welfare reasons. Consequently, several distinct diets have gained popularity, such as Western diets characterized by an abundance of processed foods and plant-based (vegetarian) diets chosen by those who avoid meat and animal products. Several studies have reported an association between dietary habits and male and/or female fertility4,5,6,7. Western diets generally have negative effects on male and female fertility4,5,6,7. Although the effects of vegetarian diets on fertility remain controversial, some studies have warned that vegetarian diets negatively affect male and female fertility4,5. As each of these diets has a unique composition defined by the inclusion or exclusion of specific components, research exploring the specific dietary components that affect fertility and their mechanisms has attracted much attention4,5,6,7.

The heterodimer of the ATP-binding cassette transporters G5 and G8 (ABCG5/G8) is a sterol efflux transporter expressed in the intestine and has been identified as the causative gene for the hereditary disease sitosterolemia, of which the well-known phenotype is the abnormal accumulation of phytosterols8,9,10,11. Several studies using Abcg5/g8 knockout (KO) mice have indicated the (patho)physiological importance of ABCG5/G8. Among these, the Jackson Laboratory and Solca. et al. demonstrated that Abcg5/g8 KO mice had reduced female fertility, which was recovered by the administration of ezetimibe, an inhibitor of Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1 (NPC1L1), which is known to be a sterol uptake transporter in the intestine12,13,14,15. The infertility observed in Abcg5/g8 KO mice was also rescued by changing the diet from common laboratory chow diets to meatball diets12. These results suggest that dietary components that are substrates of ABCG5/G8 and NPC1L1 and that are rarely found in meat may hinder the reproductive functions of female mice. However, considering that there are various types of sterols in diets and recent findings that ABCG5/G8 and NPC1L1 are also involved in the membrane transport of several fat-soluble compounds other than sterols16,17,18,19,20, it was not uncovered which dietary components cause infertility, and their mechanisms were not elucidated.

The objectives of this study were to identify the dietary components that induce infertility in Abcg5/g8 KO mice, reveal the mechanisms involved, and assess whether our findings are applicable to humans. A series of in vivo experiments with Abcg5/g8 KO mice revealed that phytosterols, which are substrates of ABCG5/G8 and NPC1L1, particularly β-sitosterol and brassicasterol, exhibit potent but reversible reproductive toxicity in female mice. Regarding the mechanisms underlying phytosterol-induced infertility, we revealed phytosterol-dependent abnormalities in the maturation of ovarian follicles, which resulted in reduced egg quality, and decreased fertilization and blastocyst development rates in fertilized eggs. In addition, we demonstrated that the suppression of follicle maturation was likely due to the phytosterol-dependent enhancement of histone H3 trimethylation at lysine 27 (H3K27me3) by polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2). Consistent with mouse in vivo observations, studies with human serum specimens collected from women who underwent in vitro fertilization (IVF) demonstrated negative associations between serum concentrations of phytosterols and egg quality, as evaluated by blastocyst development rates. This is the first report on the relationship between dietary phytosterols, epigenomic regulation, and abnormalities in follicular maturation and egg quality, thus providing new insights into the regulation of reproductive health by common dietary components.

Results

Abcg5/g8 knockout mice exhibited phytosterol-induced infertility

The fertility of female mice was evaluated by crossing them with fertile male mice for three weeks per cycle and monitoring the presence of a vaginal plug (a marker of successful mating), body weight change, and parturition for up to three cycles (Fig. 1a). Unlike wild-type (WT) mice, Abcg5/g8 KO mice fed a control chow diet (CD) showed no clear signs of pregnancy throughout the three cycles, as judged by weight gain or delivery, although a vaginal plug was observed after mating (Fig. 1b, c). Table 1 summarizes the pregnancy and parturition rates in each mouse group in terms of the number of mice (Table 1a) and the number of successful crosses with a vaginal plug (Table 1b), demonstrating that CD-fed Abcg5/g8 KO mice were completely infertile. Consistent with previous reports12, infertility in Abcg5/g8 KO mice was cured by the administration of ezetimibe, an inhibitor of NPC1L1-mediated sterol absorption13,14,15 (Table 1 and Fig. 1d). In addition, given previous observations that meatball diets cured infertility in Abcg5/g8 KO mice12, a vegetable oil-free diet (VOFD) was prepared (Supplementary Table 1) and fed to Abcg5/g8 KO mice. Notably, Abcg5/g8 KO mice fed VOFD were as fertile as WT and ezetimibe-administered Abcg5/g8 KO mice (Table 1 and Fig. 1e). In addition, we observed that even Abcg5/g8 KO mice that were determined to be infertile under CD feeding conditions became pregnant and gave birth after switching the diet from CD to VOFD (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Conversely, Abcg5/g8 KO mice that experienced pregnancy and delivery under VOFD feeding conditions became infertile when their diet was changed to CD, although Abcg5/g8 KO mice were capable of multiple pregnancies and deliveries when VOFD feeding was continued (Supplementary Fig. 1b). These results indicate that vegetable components, which are substrates of both ABCG5/G8 and NPC1L1, are potent and reversible inducers of infertility in female mice.

a Schematic illustration of the mouse fertility assessment. Representative body weight (BW) changes after observing a vaginal plug in control diet (CD)-fed female wild-type (WT) mice (b), CD-fed female Abcg5/g8 knockout (KO) mice (c), CD-fed and ezetimibe (Eze)-administered female KO mice (d), and vegetable oil-free diet (VOFD)-fed female KO mice (e). f Plasma phytosterol concentration in each mouse group [CD-fed WT (n = 5); CD-fed KO (n = 6); CD-fed and Eze-administered KO (n = 3); VOFD-fed KO (n = 3)]. Bar graphs represent the mean ± S.D. The dots on the bar graphs represent individual data points. **p < 0.01, significantly different using Sidak’s multiple comparisons test compared with CD-fed KO mice. Representative patterns of pregnancy progression monitored by BW changes and parturition after observing a vaginal plug in KO mice fed with VOFD supplemented with phytosterol mix (PS mix: β-sitosterol, campesterol, stigmasterol, and brassicasterol) (g) or individual β-sitosterol (h), campesterol (i), stigmasterol (j), or brassicasterol (k).

To identify the vegetable components in the diet that could induce reversible female infertility in Abcg5/g8 KO mice, untargeted serum metabolomics analyses were conducted. Of the approximately 10,000 peaks detected, six peaks were more than 10-fold higher in infertile Abcg5/g8 KO mice than in fertile WT mice, and these peaks were lowered to levels similar to those in WT mice by ezetimibe administration or by changing the diet from CD to VOFD (Supplementary Fig. 2a). From the information obtained on the exact mass and retention time of the six peaks, candidate compounds corresponding to the peaks were searched using an online database (Human Metabolome Database: https://hmdb.ca). Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analyses using standard compounds identified four of the six peaks as β-sitosterol, campesterol, stigmasterol, and brassicasterol (Supplementary Fig. 2b and Fig. 1f). These phytosterols have been reported to be substrates of NPC1L1 and ABCG5/G8 in vitro and in vivo15,21,22. In addition, food composition analyses revealed that the phytosterol content was much lower in VOFD than in CD (Supplementary Fig. 3). To evaluate the effects of these phytosterols on fertility, we fed Abcg5/g8 KO mice a VOFD containing a mixture of the four phytosterols at a level comparable to that of CD (Supplementary Fig. 3) and found that the animals became infertile, similarly to KO animals fed CD (Table 1 and Fig. 1g). Furthermore, mice fed VOFD containing each individual phytosterol revealed that β-sitosterol and brassicasterol strongly induced infertility, campesterol partially induced infertility, and stigmasterol had a low effect on fertility (Table 1 and Fig. 1h–k). These results indicate that phytosterols, particularly β-sitosterol and brassicasterol, are the primary constituents that strongly induce infertility in mice.

Phytosterol exacerbated folliculogenesis and egg quality in mice

We explored the mechanisms underlying phytosterol-induced infertility in Abcg5/g8 KO mice. First, because fertility and sex hormones are closely related, we analyzed the serum concentrations of female hormones in each mouse group. However, the levels of most hormones, except progesterone, were not significantly different between the groups (Supplementary Fig. 4a). Next, we analyzed ovarian function and egg quality in each mouse group, and IVF was conducted. After superovulation, the number of ovulated eggs was significantly lower in the infertile CD-fed Abcg5/g8 KO mice than in the fertile WT mice (Fig. 2a). In addition, fertilization rates (Fig. 2b) were significantly lower in eggs ovulated from CD-fed Abcg5/g8 KO mice than in eggs ovulated from WT mice. Furthermore, although there was no significant difference between the fertile and infertile mouse groups in the cleavage rates of fertilized eggs up to the 2-cell stage, a decrease in the rate was observed in infertile Abcg5/g8 KO mice as the egg-splitting stages progressed, resulting in a significantly lower development rate of fertilized eggs to blastocysts (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Fig. 2c). As a consequence of the entire process from fertilization, we observed reduced blastocyst development in ovulated eggs from CD-fed Abcg5/g8 KO mice compared to WT mice (Fig. 2d). These reductions in Abcg5/g8 KO mice were rescued by changing the diet from CD to VOFD (Fig. 2a–d and Supplementary Fig. 5). Histological analyses of the ovaries revealed that the growth (maturation) of follicles, which are functional units of the ovary that play a key role in egg development and maturation, was significantly suppressed in infertile Abcg5/g8 KO mice compared to fertile WT and VOFD-fed Abcg5/g8 KO mice (Fig. 2e). Indeed, the number (Fig. 2f) and the ratio (Fig. 2g) of antral follicles were significantly lower in the ovaries of infertile Abcg5/g8 KO mice than in those of fertile mice. Meanwhile, the number and ratio of primordial follicles in the ovaries of infertile Abcg5/g8 KO mice were higher than those in fertile mice.

a Number of ovulations, b fertilization rate, c blastocyst development rate of fertilized eggs, and d blastocyst development rate of ovulated eggs after insemination in control diet (CD)-fed wild-type (WT) mice (n = 4), CD-fed Abcg5/g8 knockout (KO) mice (n = 5), and vegetable oil-free diet (VOFD)-fed KO mice (n = 4). e Representative photographs of ovarian sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) in each mouse group. Arrowheads indicate antral follicles. Scale bar indicates 500 µm. Number (f) and percent (g) of follicles at different stages per section in the ovary of each mouse at 48 h after pregnant mare serum gonadotropin (PMSG) treatment. Nine sections from three different mice in each group were analyzed. h Ovarian phytosterol concentration in each group [CD-fed WT (n = 3); CD-fed KO (n = 3); VOFD-fed KO (n = 5)]. Bar graphs in a–d, f–h represent the mean ± S.D. The dots represent individual data points. **p < 0.01, significantly different using Sidak’s multiple comparisons test compared with CD-fed WT mice. N.S. not significantly different. i Schematic illustration of the method for in vitro culture of follicles isolated from WT mice. Representative photographs (j) and fold changes in the size (k) of follicles (n = 41–47: integrated data from at least two independent experiments using 10–25 follicles per group) from baseline (Day 0) to 10 days (Day 10) after starting incubation with the vehicle (n = 43), cholesterol (n = 45), phytosterol mix (PS mix) (n = 47), and each individual phytosterol [β-sitosterol (n = 41); campesterol (n = 45); stigmasterol (n = 46); brassicasterol (n = 46)]. Close-up images of the representative follicle surrounded by squares are shown below each photograph in (j). The scale bar in j indicates 500 µm. Horizontal lines and error bars in k show the mean ± S.D. The dots represent individual data points. **p < 0.01 significantly different using Sidak’s multiple comparisons test compared with vehicle control. N.S. not significantly different.

Given the serum phytosterol and hormone levels (Fig. 1f and Supplementary Fig. 4a), we measured the ovarian phytosterol and progesterone levels in each mouse group. Ovarian phytosterol levels were markedly higher in infertile Abcg5/g8 KO mice than in fertile WT and VOFD-fed Abcg5/g8 KO mice, which corresponded to impaired folliculogenesis (Fig. 2h). Meanwhile, ovarian progesterone levels did not show a pattern that could explain folliculogenesis failure (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Therefore, further analyses should focus on the activity of phytosterols rather than that of progesterone. To test whether phytosterols affect folliculogenesis, in vitro follicle growth assays were performed (Fig. 2i). We confirmed that our experimental conditions allowed preantral (primary and early secondary) follicles to grow in vitro and that cholesterol treatment (negative control for phytosterol treatment) hardly affected the follicle growth (Fig. 2j, k). In contrast to cholesterol, phytosterols, particularly β-sitosterol and brassicasterol, which showed strong infertility effects in vivo (Table 1 and Fig. 1h, k), significantly inhibited the follicle growth (Fig. 2j, k). Our findings suggest that phytosterol accumulation in the ovaries inhibits folliculogenesis, likely resulting in reduced ovulation and poor egg quality.

Phytosterol accumulation reduced ovarian follicular fluid-meiosis-activating sterol (FF-MAS)

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms of phytosterol-dependent ovarian dysfunction (impaired folliculogenesis), we conducted RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analyses and found that the expression levels of 70 and 27 molecules were significantly reduced to less than 67% and increased to more than 150%, respectively, in the ovaries of infertile Abcg5/g8 KO mice compared with those of fertile WT mice and VOFD-fed Abcg5/g8 KO mice (Fig. 3a). Mammalian phenotype enrichment analyses revealed that unlike the upregulated genes, the downregulated genes were enriched in genes affecting the reproductive system (Fig. 3b). Indeed, 20 of the 70 downregulated genes were reported to be involved in the regulation of reproduction and embryonic development, according to the Mouse Genome Informatics database (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Table 2). Based on these observations, we focused on the downregulated genes for further analysis.

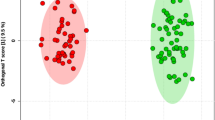

a RNA-seq analysis of ovaries collected from control diet (CD)-fed wild-type (WT) (n = 2), CD-fed Abcg5/g8 knockout (KO) (n = 3), and vegetable oil-free diet (VOFD)-fed KO mice (n = 2) were conducted. Venn diagrams show the number of genes whose expression levels were significantly lower than two-thirds (left diagrams) or higher than 1.5-fold (right diagrams) in the ovaries of CD-fed KO mice compared with the ovaries of CD-fed WT mice and VOFD-fed KO mice. b Phenotype enrichment analyses of the downregulated (top) and the upregulated (bottom) transcripts in CD-fed KO mice compared with CD-fed WT and VOFD-fed KO mice. The top five enriched phenotypes are listed. c Volcano plot of RNA-seq data showing log2 (fold change, FC) against −log10 (p value) of transcripts identified using RNA-seq analysis of ovaries from fertile mice [n = 4: CD-fed WT mice (n = 2) and VOFD-fed KO mice (n = 2)] vs. infertile CD-fed KO mice (n = 3). The red and blue dots represent upregulated and downregulated genes in infertile KO mice compared with the fertile mice group, respectively. The larger blue dots represent genes whose disruption impaired reproductive systems, based on the Mouse Genome Informatics database (https://www.informatcs.jax.org). d Gene ontology (GO) analysis of transcripts with reduced expression in the ovaries of infertile CD-fed KO mice compared with those of fertile CD-fed WT and VOFD-fed KO mice according to the values in the enrichment score under the theme of biological processes. The top five enriched processes are listed. e Selected list of differentially expressed transcripts involved in sterol biosynthetic processes in the ovaries of CD-fed WT and CD- or VOFD-fed KO mice. f Metabolic processes from squalene to FF-MAS and their associated enzymes. Representative photographs (g) and fold changes in size (h) of follicles (n = 40–50: integrated data from two independent experiments with 16–26 follicles per group) from baseline (Day 0) to 10 days (Day 10) after incubation in the absence (−) or presence (+) of the phytosterol mix (PS mix) and 1 µM FF-MAS [PS (−), FF-MAS (−) (n = 40); PS (+), FF-MAS (−) (n = 50); PS (+), FF-MAS (+) (n = 47)]. Close-up images of the representative follicle surrounded by squares are shown below each photograph in (g). The scale bar in g indicates 500 µm. Horizontal lines and error bars in h show the mean ± S.D. The dots represent individual data points. **p < 0.01, significantly different using Sidak’s multiple comparisons test compared with PS mix (−) and FF-MAS (−). N.S. not significantly different. Relative mRNA levels of Sqle, Lss, and Cyp51 analyzed using quantitative real-time PCR (i) and concentrations of FF-MAS (j) in the ovaries of CD-fed WT mice (n = 4 for analyzing Sqle, n = 8 for analyzing Lss and Cyp51, and n = 6 for analyzing FF-MAS), CD-fed KO mice (n = 4 for analyzing Sqle, n = 8 for analyzing Lss and Cyp51, and n = 6 for analyzing FF-MAS), and VOFD-fed KO mice (n = 4 for analyzing Sqle, n = 8 for analyzing Lss and Cypr51, and n = 5 for analyzing FF-MAS). Bar graphs represent mean ± S.D. The dots represent individual data points. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, significantly different using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test compared with CD-fed WT mice. N.S. not significantly different.

Gene ontology analysis revealed that the downregulated genes were also associated with sterol biosynthesis (Fig. 3d). RNA-seq analysis revealed that many genes associated with sterol biosynthesis were downregulated in the ovaries of infertile Abcg5/g8 KO mice (Fig. 3e). Among these genes, we particularly focused on squalene epoxidase (Sqle), lanosterol synthase (Lss), and cytochrome P450 family 51 (Cyp51), which are involved in the production of FF-MAS (Fig. 3f)23, because FF-MAS has been reported to improve egg quality24,25, and we found that phytosterol-induced suppression of follicle growth could be rescued by FF-MAS treatment in vitro (Fig. 3g, h). Consistent with the results of the RNA-seq analyses, quantitative PCR (qPCR) assays showed that the mRNA levels of Sqle, Lss, and Cyp51 were significantly lower in the ovaries of infertile Abcg5/g8 KO mice than in those of fertile WT and VOFD-fed Abcg5/g8 KO mice (Fig. 3i). We then quantified the ovarian concentration of FF-MAS and found that FF-MAS was significantly reduced in infertile Abcg5/g8 KO mice compared to fertile WT and VOFD-fed Abcg5/g8 KO mice (Fig. 3j), which may account for the phytosterol-dependent suppression of follicle growth (folliculogenesis) and the deterioration in egg quality.

Polycomb repressive complex 2 was activated in the ovary in phytosterol-dependent manner

Since multiple genes potentially involved in the reproductive system and embryogenesis, in addition to those involved in sterol biosynthesis, were downregulated in a dietary phytosterol-dependent manner, we speculated that there may be some common genome-binding factors that regulate the expression of these genes. We searched for such factors using ChIP-seq database (ChIP-Atlas: http://chip-atlas.org/) and components of polycomb repressive complexes (PRCs), especially PRC2 components such as Jumonji/ARID domain-containing protein 2 (Jarid2), Metal regulatory transcription factor 2 (Mtf2), Suppressor of zeste 12 protein homolog (Suz12), and enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (Ezh2), emerged as top candidates (Fig. 4a, b). PRC2 exhibits histone methyltransferase activity and plays a key role in histone H3 trimethylation at lysine 27 (H3K27me3), which is responsible for repressing the transcription of downstream genes involved in early embryonic development26. In addition, a recent study indicated that PRC2 can downregulate sterol regulatory element binding protein 1a (Srebp1a), a major transcriptional regulator of genes involved in sterol biosynthesis, in cooperation with the estrogen receptor β27. Therefore, we analyzed ovarian H3K27me3 levels in each mouse group and found that they were significantly higher in infertile Abcg5/g8 KO mice than in fertile WT and VOFD-fed Abcg5/g8 KO mice (Fig. 4c). We also observed that the mRNA levels of Srebp family members, including Srebp1a, decreased in a dietary phytosterol-dependent manner in the ovaries of Abcg5/g8 KO mice (Supplementary Fig. 6). Our results suggested that PRC2 was activated in the phytosterol-accumulated ovary; therefore, its downstream genes, including sterol biosynthesis-related genes, were downregulated (Fig. 4d).

a The top 10 upstream binding factors enriched in downregulated transcripts in ovaries from infertile Abcg5/g8 knockout mice are listed. ChIP-Atlas was used for enrichment analysis. The bar charts indicate the p value for enrichment, with the colors indicating polycomb repressive components (red: PRC2 component; blue: PRC1 component) or not (white). b Protein-protein interaction networks based on the STRING database (https://string-db.org) for the top 10 upstream binding factors listed in (a). c H3K27me3 levels standardized to the total histone H3 levels in the ovaries of each mouse group [CD-fed WT (n = 4); CD-fed KO (n = 5); VOFD-fed KO (n = 7)]. Bar graphs represent the mean ± S.D. The dots on the bar graphs represent each individual data point. *p < 0.05, significantly different using Sidak’s multiple comparisons test compared with CD-fed WT mice. N.S. not significantly different. d Schematic illustration of the putative mechanisms of phytosterol (PS)-mediated follicle growth suppression and egg quality reduction.

PRC2 inhibitors could rescue the phytosterol-induced suppression of follicle growth and infertility

We examined whether inhibition of PRC2 could rescue the phytosterol-induced suppression of follicle growth. In vitro follicle growth assays demonstrated that all PRC2 inhibitors tested counteracted the negative effects of phytosterols (Fig. 5a, b). In addition, metformin, a clinically used drug for type II diabetes, has been reported to reduce H3K27me3 levels by suppressing PRC2 activity28 and/or decreasing the expression of PRCs components29,30 and was able to restore phytosterol-induced suppression of follicle growth, similar to other PRC2 inhibitors (Fig. 5a, b). Furthermore, consistent with in vivo observations (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Fig. 3i), in vitro follicle growth assays also confirmed that phytosterols suppressed the mRNA expression of Srebp family members and sterol biosynthesis-related genes, and this suppression was restored by metformin treatment (Supplementary Fig. 7 and Fig. 5c).

Representative photographs (a) and fold changes in the size (b) of follicles (n = 30–34: integrative data from at least two independent experiments with 10–24 follicles per group) from baseline (Day 0) to 10 days (Day 10) after incubation with vehicle control, 50 nM GSK343 (GSK), 125 nM EPZ005687 (EPZ), 25 nM tazemetostat (Taz), or 1 µM metformin (Met) in the absence (−) or presence (+) of the phytosterol mix (PS mix) [PS (–), Vehicle (n = 31); PS (+), Vehicle (n = 30); PS (+), GSK (n = 32); PS (+), EPZ (n = 34); PS (+), Taz (n = 34); PS (+), Met (n = 33)]. Close-up images of the representative follicle surrounded by squares are shown below each photograph in (a). The scale bar in a indicates 500 µm. Horizontal lines and error bars in b show the mean ± S.D. The dots represent individual data points. **p < 0.01, significantly different using Sidak’s multiple comparisons test compared with vehicle control in the absence of the PS mix. N.S. not significantly different. c Relative mRNA levels of Sqle, Lss, and Cyp51 analyzed using quantitative real-time PCR in follicles 10 days after incubation with vehicle control or 1 µM metformin in the absence (–) or presence (+) of the PS mix [PS (–), Vehicle (n = 3); PS (+), Vehicle (n = 4); PS (+), Metformin (n = 3)]. Bar graphs represent the mean ± S.D. The dots represent individual data points. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, significantly different using Sidak’s multiple comparisons test. N.S. not significantly different.

We then addressed whether the suppression of PRC2 could rescue phytosterol-induced infertility in vivo. For this purpose, we used metformin, which has well-established safety and pharmacokinetic profiles in mice31. First, we confirmed that metformin administration (Fig. 6a) reversed the increase in ovarian H3K27me3 levels in CD-fed Abcg5/g8 KO mice (Fig. 6b), although phytosterol accumulation in the ovaries was maintained (Fig. 6c). In addition, consistent with in vitro results (Supplementary Fig. 7 and Fig. 5c), the reduction in the mRNA expression of the Srebp family members, Sqle, Lss, and Cyp51, was restored by metformin administration in CD-fed Abcg5/g8 KO mice (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Fig. 6d), resulting in the recovery of ovarian FF-MAS levels (Fig. 6e). Consistent with these results, follicle growth suppression was rescued in metformin-treated CD-fed Abcg5/g8 KO mice (Fig. 6f–h). Furthermore, the number of ovulations, fertilization rate, and blastocyst development rate were (partially) restored in the metformin-treated CD-fed Abcg5/g8 KO mice (Fig. 6i–k). In accordance with the restoration of follicular development and egg quality, a proportion of the metformin-treated CD-fed Abcg5/g8 KO mice recovered their fertility (Table 1 and Fig. 6l). These results suggest that PRC2 inhibition may reverse the phytosterol-induced deterioration of follicular development and egg quality, thereby promoting fertility in mice.

a Timeline of metformin administration studies using Abcg5/g8 knockout mice. Metformin (2 mg/mL) dissolved in drinking water was administered to control diet (CD)-fed Abcg5/g8 knockout mice from 8 weeks of age. Four weeks after the start of metformin administration, monitoring pregnancy and parturition, tissue sampling, or IVF experiments were performed. H3K27me3 levels standardized to histone H3 levels (b) and phytosterol levels (c) in the ovaries of control diet (CD)-fed wild-type mice [WT (CD)] (n = 3), CD-fed Abcg5/g8 knockout mice [KO (CD)] (n = 5 for analyzing H3K27me3 levels and n = 3 for analyzing phytosterol levels), and metformin-administered CD-fed KO mice [KO (CD + Met)] (n = 5 for analyzing H3K27me3 levels and n = 3 for analyzing phytosterol levels). Bar graphs represent the mean ± S.D. The dots represent individual data points. **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, significantly different using Sidak’s multiple comparisons test compared with CD-fed WT mice (b) or CD-fed KO mice (c). N.S. not significantly different. Relative mRNA levels of Sqle, Lss, and Cyp51 analyzed using quantitative real-time PCR (d) and concentrations of FF-MAS (e) in the ovaries of each mouse group [WT (CD) (n = 4 for analyzing Sqle, n = 8 for analyzing Lss and Cyp51, and n = 6 for analyzing FF-MAS); KO (CD) (n = 4 for analyzing Sqle, n = 8 for analyzing Lss and Cyp51, and n = 6 for analyzing FF-MAS); KO (CD + Met) (n = 4)]. Bar graphs represent the mean ± S.D. The dots represent individual data points. Data sets of CD-fed WT mice and CD-fed KO mice are the same as those in Fig. 3i, j. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, significantly different using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post hoc test compared with CD-fed WT mice. N.S. not significantly different. f Representative photographs of ovarian sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) in the indicated mouse groups. Arrowheads indicate antral follicles. Scale bar indicates 500 µm. Number (g) and percent (h) of follicles at different stages per section in the ovary of each mouse group at 48 h after PMSG treatment. Nine sections from three different mice in each group were analyzed. i Number of ovulations, j fertilization rate, and k blastocyst development rate of ovulated eggs after insemination in CD-fed WT mice (n = 4), CD-fed KO mice (n = 4), and metformin-administered CD-fed KO mice (n = 3). Bar graphs in g–k represent the mean ± S.D. The dots represent individual data points. **p < 0.01, significantly different using Sidak’s multiple comparisons test compared with CD-fed WT mice. N.S. not significantly different. l A representative pattern of pregnancy progression monitored by body weight (BW) changes and parturition in metformin-administered CD-fed KO mice after observing a vaginal plug.

Serum phytosterol levels were negatively correlated with the blastocyst development rate of fertilized eggs in humans

Finally, to evaluate the clinical significance of phytosterols on egg quality, serum concentrations of phytosterols were measured in women who underwent IVF. A summary of the IVF patients in this study is presented in Supplementary Table 3. Serum concentrations of any of the four phytosterols tested did not correlate significantly with the number of eggs available for IVF or the successful fertilization rate of the eggs. However, the serum concentrations of β-sitosterol, campesterol, and brassicasterol were significantly and negatively correlated with the blastocyst development rate of the fertilized eggs (Fig. 7a). In contrast, serum concentrations of stigmasterol, which has lower reproductive toxicity in mice, showed no significant correlation with blastocyst development rate in our analysis. In addition, intergroup comparisons demonstrated that women with a low blastocyst development rate (≦33.3% of fertilized eggs) had significantly higher serum concentrations of β-sitosterol and brassicasterol than other groups with a higher blastocyst development rate (33.4–66.6% and ≧66.7% of fertilized eggs), while there were no significant differences in serum concentrations of campesterol and stigmasterol between groups (Fig. 7b). These results suggest that phytosterols that are reproductively toxic to mice would also have negative effects on egg quality in humans, particularly in terms of the normal developmental rate of fertilized eggs to blastocysts.

a Correlations of blastocyst development rate of fertilized eggs with serum concentrations of phytosterols (β-sitosterol, campesterol, stigmasterol, and brassicasterol) in women that underwent in vitro fertilization (n = 21). Correlation analyses were performed using Pearson’s method. R-value represents the Pearson’s correlation coefficient. b Subjects were divided into three groups based on the blastocyst development rate of the fertilized eggs [High group: ≧66.7% (n = 5); Medium group: 33.4–66.6% (n = 9); Low group: ≦33.3% (n = 7)] and compared serum phytosterol levels between groups. Box and whiskers plots represent median (line in box center), first and third quartile (lower and upper box border, respectively), and minimum and maximum values (whiskers). *p < 0.05, significantly different using Sidak’s multiple comparisons test compared with the Low group. N.S. not significantly different.

Discussion

A typical human diet provides approximately 200–300 mg of phytosterols per day32. To date, more than 250 phytosterols have been found and identified33. Among them, β-sitosterol, campesterol, stigmasterol, and brassicasterol have been reported to account for more than 90% of dietary phytosterols we consume34. β-sitosterol, campesterol and stigmasterol are found in a wide-variety of plant-based foods including nuts, seeds, and vegetable oils. Brassicasterol is particularly abundant in seaweeds and canola oil. These phytosterols have long been used as food additives35. Among the four major phytosterols, we found that β-sitosterol and brassicasterol were particularly associated with infertility, while stigmasterol showed lower toxicity on female reproductive systems in mice (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Interestingly, despite their minor structural differences, the phytosterols exhibited distinct effects. Although phytosterols are often treated as a single class, our findings, along with previous studies showing variations in physiological activities—such as anti-inflammatory effects and inhibition of Srebp processing to its active form—highlight the importance of evaluating individual phytosterols to better understand their specific physiological impacts36,37.

We observed that β-sitosterol and brassicasterol negatively affected ovarian folliculogenesis (Fig. 2j, k). Since we observed that follicular development (Fig. 2e–g), and ovulated egg quality (Fig. 2b–d) were well matched in each mouse group, we considered that impaired folliculogenesis by phytosterols was the primary cause of reduced egg quality. However, because our study provides no direct evidence that defects in folliculogenesis result in poor egg quality in infertile Abcg5/g8 KO mice, it is possible that impaired folliculogenesis and poor egg quality are two independent adverse effects of phytosterol accumulation. Among the major female hormones regulating folliculogenesis and egg quality, only serum progesterone levels were significantly increased in infertile Abcg5/g8 KO mice compared to fertile mice (Supplementary Fig. 4a). However, given that poor ovarian function is commonly associated with low rather than high serum progesterone levels38, and that our findings showed that ovarian progesterone levels did not show a pattern that could explain folliculogenesis failure (Supplementary Fig. 4b), elevated progesterone levels in infertile KO mice are unlikely to be the cause of abnormal follicle development or poor egg quality. These results suggest that phytosterol accumulation is a risk factor for infertility, independent of female hormone status.

We demonstrated that ovarian FF-MAS levels were significantly lower in infertile Abcg5/g8 KO mice than in fertile mice, which is consistent with the reduced expression levels of sterol biosynthesis-related enzymes (Fig. 3e, i). To date, several studies have been conducted on the physiological functions of FF-MAS. For instance, previous in vitro studies using ovulated eggs have shown that the addition of FF-MAS to the culture media can accelerate egg maturation (promotion of meiosis resumption) and improve the blastocyst development rate25, although it is controversial whether the meiotic progression effect is physiologically observed in vivo39. In the present study, we found that infertile Abcg5/g8 KO mice with reduced ovarian FF-MAS levels exhibited impaired folliculogenesis (Figs. 2e–g and 3j), and that the inhibition of follicle growth by phytosterols could be rescued by FF-MAS in vitro (Fig. 3g, h). Considering that the FF-MAS concentration (1 µM) we used in vitro was at physiological levels in the ovary of mice (Fig. 3j) and humans (approximately 1.6 µM)24, our results suggest that FF-MAS plays an important role not only in eggs (meiotic progression) but also in follicles (follicle maturation) under physiological conditions. Unfortunately, the molecular mechanisms underlying the FF-MAS-mediated folliculogenesis remain unclear. However, several mechanisms have been proposed for the action of FF-MAS on eggs, including involvement of activation of G protein-coupled receptors40 and Liver X receptor α41. Future studies investigating whether these molecules are also involved in the effects of FF-MAS on follicles will deepen our understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying the physiological functions of FF-MAS.

Recently, Ragazzini et al. reported that homozygous knockout of Ezh1/2 inhibitory protein (Ezhip) impaired fertility in female mice, although male mouse fertility was hardly affected42. They also demonstrated that increased H3K27me3 levels in the follicles and eggs were responsible for the reduced fertility of female Ezhip-knockout mice. Collectively, these findings and our results suggest that PRC2 hyperactivity leads to female infertility. One limitation of this study is that it is unclear how phytosterols enhance PRC2 activity. RNA-seq analyses indicated that the mRNA levels of the central components of PRC2, such as Ezh2, Suz12, Jarid2, and Eed, and Ezhip mRNA levels in infertile KO mice were almost the same as those in the fertile mouse groups (data not shown), and it is unlikely that phytosterols regulate the transcription of PRC2 components or Ezhip. It has been revealed that the activity of PRC2, including genomic targeting and catalytic activities, is controlled by several factors, such as cis chromatin features, PRC2 facultative subunits, and post-transcriptional modifications of PRC2 subunits43. Interestingly, a previous plant-based study showed that brassinosteroids, which have chemical structures similar to phytosterols, control PRC2 function and that several key factors that may also operate in mammalian tissues have been implicated in their regulation44. Further studies to clarify the effects of phytosterols on these factors would be helpful for understanding the molecular basis of phytosterol-mediated PRC2 activation.

We demonstrated that metformin administration in infertile Abcg5/g8 KO mice suppressed PRC2 activation in the ovaries (Fig. 6b) and improved phytosterol-induced infertility (Table 1 and Fig. 6f–l). Metformin is a drug used in the treatment of insulin resistance in diabetes mellitus, but it has also been reported in the field of obstetrics and gynecology to improve ovulation disorders in polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS)45 and metformin therapy for PCOS is covered by insurance in some countries. However, the mechanisms underlying the effects of metformin on PCOS remain unclear. Since there have been cases in which metformin treatment was effective in patients with PCOS without insulin resistance, it is considered that metformin exerts its therapeutic effect on PCOS independently of the improvement of insulin resistance46. Although the ovarian histology of Abcg5/g8 KO mice (Fig. 2e–g) did not necessarily match the typical features of patients with PCOS or PCOS model mice47, PRC2 inhibition may be one of the mechanisms by which metformin ameliorates ovulation disorders in PCOS, as observed in Abcg5/g8 KO mice. Recently, it was revealed that chromobox homolog 2, which recognizes H3K27me3 and mediates gene silencing, regulates the expression of several genes associated with PCOS48,49. Together with our results showing that metformin inhibits PRC2-mediated H3K27 trimethylation in the ovary (Fig. 6b), it is possible that the inhibition of PRC2 activity is involved in the pharmacological effects of metformin on PCOS. Further analyses of H3K27me3 levels in the ovaries (follicles) of patients with PCOS will help to better understand the mechanism of action of metformin in PCOS. Among the diverse pharmacological actions of metformin, the results of this study bring us closer to elucidating the key pharmacological mechanisms and discovering new benefits of metformin in infertility treatment.

In relation to the above findings regarding ovulation, we observed that ovulation defect in infertile Abcg5/g8 KO mice was not completely recovered upon metformin treatment (Fig. 6i), although follicular development was well restored (Fig. 6f–h). Given that ovarian phytosterol accumulation was maintained after metformin treatment (Fig. 6c), these results suggest that phytosterol accumulation in the ovary might affect ovulation in a metformin (and PRC2)-insensitive manner. The involvement of molecules other than PRC2 in phytosterol-induced ovulatory defects is an important topic for future research.

Similar to the results in mice (Fig. 1), the blood levels of phytosterols, such as β-sitosterol, campesterol, and brassicasterol, were negatively correlated with the blastocyst development rate of eggs after insemination in humans (Fig. 7a), suggesting that phytosterols may influence egg quality in humans. However, the blood levels of these three phytosterols correlated well with each other (β-sitosterol and campesterol: R = 0.85, p < 0.0001; β-sitosterol and brassicasterol: R = 0.88, p < 0.0001; campesterol and brassicasterol: R = 0.95, p < 0.0001). Some of the negative correlations between phytosterol levels and blastocyst development rates may be due to confounding factors. This may explain the contradictory results showing that campesterol, which is relatively less toxic to follicular growth in vitro (Fig. 2j, k), was negatively correlated with blastocyst development rate. In addition, considering that serum concentrations of β-sitosterol in humans were much lower than those in Abcg5/g8 KO mice, whereas serum brassicasterol concentrations were comparable between humans and Abcg5/g8 KO mice (Figs. 1f and 7), brassicasterol, rather than β-sitosterol, might have a strong impact on egg quality in humans.

It has previously been noted that vegetarian or vegan food intake before and during pregnancy can affect pregnancy progression, owing to the lack of nutrients essential for fetal and maternal health. Based on our findings, these extreme dietary patterns may require attention because of excessive phytosterol intake and nutritional deficiency. Additionally, particular attention should be paid to patients with impaired ABCG5/G8 function. Until recently, only 100 individuals with a loss-of-function mutation in ABCG5/G8 (sitosterolemia) had been reported, leading to the belief that it is a fairly rare genetic disorder50. However, a recent exome sequencing analysis reported that one in 220 individuals had a loss-of-function mutation in ABCG5 or ABCG850,51, suggesting that patients with sitosterolemia might be overlooked. Although the association between sitosterolemia and infertility has not yet been analyzed, it is important to appropriately identify (diagnose) previously overlooked patients with sitosterolemia and investigate their fertility.

In conclusion, using mice with impaired sterol excretion, we revealed for the first time that phytosterol (particularly β-sitosterol and brassicasterol) accumulation suppresses folliculogenesis and reduces egg quality via the abnormal enhancement of histone H3K27me3 by PRC2. In addition, our clinical analyses demonstrated a negative correlation between serum levels of reprotoxic phytosterols and the blastocyst development rate in humans. These results provide novel insights into the physiological activities and toxicities of phytosterols from the viewpoint of epigenomic modulation, and shed new light on the association between dietary phytosterols and reproductive health. Changing diets to avoid the excessive intake of certain phytosterols would be beneficial to female reproductive health and reduce the risk of infertility. Phytosterols are generally considered beneficial because they reduce intestinal cholesterol absorption and blood cholesterol levels52. However, phytosterols have also been reported to have toxic effects. Early onset atherosclerosis has been reported in patients with sitosterolemia53. Platelet abnormalities due to phytosterol accumulation have also been observed in Abcg5/g8 KO mice and patients with sitosterolemia54,55. These results, together with our current findings, indicate that phytosterols in the body are not necessarily beneficial, but toxic when accumulated, requiring more attention to their levels.

Materials and methods

Materials

β-Sitosterol, campesterol, and brassicasterol were purchased from Tama Biochemical (Tokyo, Japan). Stigmasterol and metformin hydrochloride were purchased from the Tokyo Chemical Industry (Tokyo, Japan). Cholesterol and ergosterol were purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation (Osaka, JAPN). 5α-Cholestan-3β-ol was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA). Follicular fluid meiosis-activating sterol (FF-MAS) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Birmingham, AL, USA). Paraffin fluid was purchased from Nacalai Tesque (Kyoto, Japan). FERTIUP sperm pre-culture medium, CARD MEDIUM, modified human tubal fluid (mHTF) medium, and potassium simplex optimized medium with amino acids (KSOM/AA) were purchased from Kyudo (Saga, Japan). Pregnant mares’ serum gonadotropin [PMSG (serotropin)] and human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) were purchased from ASKA Pharmaceuticals (Tokyo, Japan). GSK343, EPZ005687, and tazemetostat were purchased from Selleck (Houston, TX, USA). All other reagents used in this study are commercially available, and Supplementary Table 4 summarizes the suppliers’ names and catalog numbers for each reagent.

Experimental animals

Abcg5/g8 KO mice (B6; 129S6-Abcg5/Abcg8tm1 Hobb/J) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and backcrossed with WT C57BL/6J mice (Japan SLC, Inc, Shizuoka, Japan) before use16. The mice were housed in temperature- and humidity-controlled animal cages with a 12 h dark/light cycle and had free access to water and animal chow (FR-1, Funabashi-Farm, Chiba, Japan). All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the US National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and protocols (P12-089, P17-063, and P22-038), approved by the Animal Studies Committee of The University of Tokyo. All mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation. We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use.

Diet preparation

AIN-76A (powdered diet), used as a control chow diet (CD), was purchased from Research Diets, Inc. (New Jersey, USA). A 0.005% ezetimibe-containing diet was prepared by adding 5 mg of ezetimibe (Kemprotec, Carnforth, UK) to 100 g of AIN-76A and mixing well with a mortar. Vegetable oil-free diet (VOFD) (powdered diet) was custom-made by Research Diets, Inc. (Supplementary Table 1). Phytosterol mix-containing VOFD was prepared by adding 20 mg of β-sitosterol, 9 mg of campesterol, 840 µg of stigmasterol, and 400 µg of brassicasterol to 100 g of VOFD and mixing thoroughly using a mortar (Supplementary Fig. 3). Individual phytosterol-containing VOFDs were also prepared by adding each amount (as described above) of individual phytosterols to 100 g of VOFD and mixing well using a mortar.

Metformin administration

Metformin was administered by dissolving metformin hydrochloride (2 mg/mL) in bleeding water.

Fertility evaluation

Eight-week-old female WT and KO mice fed each diet were evaluated for pregnancy and delivery by cohabitation and mating with fertile male mice for three weeks in one cycle, for up to three cycles until the mice gave birth and began rearing pups (Fig. 1a). After the start of mating, the vaginal plug was checked as an indicator of mating, and body weight changes were monitored.

Untargeted metabolomics analysis of serum specimens

Serum samples (100 µL) were vortexed for 5 min with four volumes of methanol containing prednisolone as the internal standard, followed by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and dried using a SpeedVac. After drying, the residue was redissolved in 100 µL of methanol for untargeted metabolomics analysis.

Untargeted metabolomics analysis was performed using a Thermo Scientific Q Exactive Orbitrap LC-MS/MS System (Thermo Fisher Scientific K.K., Tokyo, Japan) coupled with a DIONEX Ultimate 3000 Rapid Separation LC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific K.K.), as reported previously56. Briefly, a volume of 2 μL of the sample was injected onto a Syncronis aQ column (100 × 21 mm, 5 μm; Thermo Fisher Scientific K.K.) and then separated. Elution was performed using a linear gradient mobile phase (0–40 min: 0–100% B) of 0.1% formic acid in ultrapure water (A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (B), at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min. The column and autosampler temperatures were maintained at 40 °C and 10 °C, respectively. Ionization was performed in atmospheric-pressure chemical ionization mode. The S-lens level was set at 80. The capillary and vaporizer temperatures were set at 250 °C and 400 °C, respectively. The nitrogen sheath and auxiliary gas flow rates were set as 50 and 20 arbitrary units, respectively. Detection was performed using a Q Exactive mass spectrometer controlled by the Excaliber software (Thermo Fisher Scientific K.K.), and the exact masses were calculated using the Qualbrowser program (Thermo Fisher Scientific K.K.). Full MS scans were performed with a full-spectrum acquisition from m/z 100 to 800. The resolution was 70,000 FWHM at m/z 200 with a maximum injection time of 0.25 s. The automatic gain control was set at 1 × 106. To detect differences among mouse groups, we performed a differential analysis of profiling data using SIEVE software (Thermo Fisher Scientific K.K.), resulting in the generation of a dataset consisting of ion peaks [m/z and retention time (Rt)] and their respective intensities (peak areas). Peak detection and Rt corrections were performed using the following parameters: mass range, 100–800 m/z; mass tolerance, 10 ppm; Rt range, 0–40 min; and intensity threshold, 50,000.

Sample preparation for sterol quantification

For the analysis of sterols in the ovary and serum specimens, ovaries from each mouse were homogenized in 250 µL of saline, and ovarian homogenates (100 µL) and 100 µL of serum specimens were vortexed with 200 µL of 10 µM ergosterol (ethanol solution) as an internal standard. Then, 50 µL of 1 mg/mL butylated hydroxytoluene (ethanol solution) and 500 µL of 1 M potassium hydroxide (KOH) (ethanol solution) were added to the sample and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h to saponify. After saponification, 140 µL Milli-Q water was added to the sample, and the saponified sterols were extracted with hexane (500 µl × 2). The combined organic layers were dried using N2 gas at 40 °C, followed by picolinoyl derivatization.

For the analyses of sterols in the diets, each diet (1 g) was mixed with 5 mL of 3 µM 5α-cholestan-3β-ol (ethanol solution) as an internal standard and vortexed thoroughly. The mixture was then centrifuged at 500 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and evaporated with N2 gas at 40 °C. The residues were dissolved in 100 µL of 50% KOH solution and 400 µL of ethanol, and incubated at 85 °C for 20 min. The samples were then cooled to room temperature, and 250 µL Milli-Q water and 500 µL hexane were added, and vortexed thoroughly. The mixture was then centrifuged at 500 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and evaporated under N2 gas at 40°C, followed by picolinoyl derivatization.

For the picolinoyl derivatization of sterols, the resulting residue was dissolved in 170 µL of picolinoyl derivatization solution [2-methyl-6-nitrobenzoic anhydride (1244.5 mg), 4-dimethylaminopyridine (373.3 mg), picolinic acid (995.5 mg), triethylamine (2.5 mL), and dry pyridine (18.7 mL)] and incubated overnight at room temperature. The reaction mixture was diluted with a 5% sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3) solution (1 mL), and the product was extracted with ethyl acetate (1.5 mL × 2). The combined organic layer was washed successively with a saturated sodium chloride (NaCl) solution, 5% hydrogen chloride (HCl) solution, and again with a saturated NaCl solution, and then, it was evaporated with N2 gas at 40 °C. The residues were dissolved in methanol for ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC)-MS/MS analysis as described below.

Quantification of sterols

An LC-MS/MS system consisting of an ACQUITY UPLC instrument coupled with a Xevo TQ-S triple-quadrupole MS/MS system (Waters, Milford, MA, USA) was used to measure sterol concentration. Separations were performed with a VanGuard BEH C18 (1.7 µm) as the pre-column (Waters) and an ACQUITY UPLC BEH C18 Column (1.7 µm, 2.1 × 100 mm) (Waters) as the main column. The sample and column temperatures were maintained at 4 and 40 °C, respectively. The mobile phase comprised a mixture of 0.1% formic acid in Milli-Q water (Solvent A) and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (Solvent B). Isocratic elution (5% solvent A and 95% solvent B) was performed for 20 min at a flow rate of 0.3 mL/min. The analytes were monitored using multiple reaction monitoring in electrospray positive ionization mode. The monitoring parameters and settings (Rt, m/z of the parent and daughter ions, cone voltage, and collision energy) are listed in Supplementary Table 5. Peak analyses were performed using the MassLynx NT software version 4.1 (Waters).

Ovary histology

Eight- to twelve-week-old female mice were treated with 7.5 IU PMSG. Forty-eight hours after PMSG treatment, ovaries were collected. The collected ovaries were fixed in a 10% formalin solution. The preparation of paraffin blocks of fixed ovaries, thin (5 µm) sections, and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining were outsourced to the Department of Human Pathology, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo. In each H&E-stained thin section, the number of follicles was counted by follicle type, with flattened granulosa cells considered primordial follicles, a single layer of granulosa cells surrounding the ovum considered primary follicles, multiple layers of granulosa cells surrounding the ovum considered secondary follicles, and the follicle cavity observed considered antral follicles. Histological examination of the ovaries was performed in a blinded manner.

In vitro fertilization

IVF was performed as reported previously57. Briefly, cauda epididymides were obtained from WT male mice over 12 weeks of age, and spermatozoa were suspended in 100 µL of the FERTIUP sperm preculture medium covered with liquid paraffin. Subsequently, the samples were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in 5% CO2 and 95% humidified air until insemination. Eight- to twelve-weeks-old female mice were superovulated using 7.5 IU of PMSG and 7.5 IU of hCG, and 15–17 hours after the hCG administration, their oviducts were isolated and transferred to fertilization dishes containing a drop (200 µL) of CARD MEDIUM covered with liquid paraffin. Cumulus-oocyte complexes (COCs) were introduced into a drop of CARD MEDIUM. After pre-incubation of fresh sperm, 3 µL of the sperm suspension was added to a drop containing COCs. Fertilization dishes were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 and 95% humidified air. After 3 h, the inseminated oocytes were washed three times with the mHTF medium. The cumulus cells were removed by pipetting with a glass capillary during washing. After washing, the inseminated oocytes were cultured in mHTF medium. Six hours after insemination, fertilized eggs were identified and counted based on the presence of two pronuclei (2PN) were observed. Fertilized eggs with 2PN were cultured further in mHTF medium. Twenty-four hours after insemination, two-cell stage embryos were counted and transferred to KSOM/AA. Every 24 h thereafter, the four-cell stage embryos, morulae, and blastocysts were counted.

In vitro follicle growth assay

Preantral follicles of approximately 100–200 µm in diameter were mechanistically isolated as described previously58 by tearing ovaries collected from 3-week-old WT mice with a 30-gauge needle in Leibovitz’s L-15 medium (Sigma-Aldrich) containing 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS). The isolated follicles were washed in L-15 medium containing 1% FBS, and 10–30 follicles were transferred into a 35 mm dish with 700 µL of mixture of growth factor reduced (GFR)-Matrigel Matrix (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA) and DMEM/F12 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) (1:1) containing recombinant human follicle stimulating hormone [rhFSH (Gonal-F®)] (100 mIU/mL), penicillin-streptomycin (PCSM) (1%), in the absence (3 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA) only for control) or presence of sterol-loaded methyl-β-cyclodextrin (MβCD) with or without PRC2 inhibitors [GSK343 (50 nM), EPZ005687 (125 nM), tazemetostat (25 nM), or metformin (1 µM)]. The concentrations of each PRC2 inhibitor were set at those that were not toxic to sterol non-treated follicles. Thirty minutes after seeding, 350 µL of the corresponding culture medium [DMEM/F12 supplemented with rhFSH (100 mIU/mL) and PCSM (1% w/v) in the absence or presence of sterol-loaded MβCD, with or without PRC2 inhibitors] was added to each well. Follicles were photographed using a Keyence fluorescence microscope (BZ-X800) (day 0). Subsequently, the follicles were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 and 95% humidified air, and half of the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium every two days. After 10 days of incubation (day 10), the follicles were photographed again using a BZ-X800. Follicle growth was assessed by measuring the increase in the size (area) of each follicle using the ImageJ software.

Preparation of sterol-loaded MβCD was as follows: 0.5 mL ethanol solution containing 741.2 µM cholesterol, phytosterol mix (400 µM β-sitosterol, 300 µM campesterol, 40 µM stigmasterol, and 1.2 µM brassicasterol) with or without 20 µM FF-MAS, or individual phytosterols at the same concentrations as phytosterol mix was added drop by drop to 5% (w/v) MβCD solution at 80°C (molar ratio of sterol:MβCD = 1:10) with stirring until becoming clear. The mixture was then dried in a SpeedVac and redissolved in 60 mg/mL BSA solution (0.5 mL). After reconstitution, the mixture was mixed with 10 mL of a mixture of the GFR-Matrigel Matrix and DMEM/F12 (1:1) or 10 mL of DMEM/F12, and the other required reagents were added. Final concentrations of each sterol in the culture medium and in the mixture of GFR-Matrigel Matrix and DMEM/F12 were set as follows based on ovarian concentrations of each phytosterol in infertile Abcg5/g8 KO mice: cholesterol (37.06 µM), β-sitosterol (20 µM), campesterol (15 µM), stigmasterol (2 µM), and brassicasterol (0.06 µM). The final concentration of FF-MAS in the culture medium and in the mixture of GFR-Matrigel Matrix and DMEM/F12 was 1 µM.

Total RNA extraction from ovaries

Ovaries were collected from 8- to 12-week-old female mice. Each ovary was then homogenized in 200 µL RNAiso Plus (TaKaRa, Osaka, Japan) (1 ovary/200 µL RNAiso Plus), incubated at room temperature for 5 min, centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant was collected. Then, 40 µL chloroform was added to the collected supernatant, shaken vigorously, incubated at room temperature for 5 min, centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min, and the top layer was collected. To the collected top layer, 200 µL isopropanol was added, mixed by inversion, incubated at room temperature for 10 min, centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min, and the supernatant was removed. Next, 200 µL of ice-cold 75% ethanol was added to the pellet, centrifuged at 7500 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant was removed. After the pellet was air-dried, it was redissolved in 16 µL of diethylpyrocarbonate-treated water, incubated at 65°C for 5 min, and rapidly cooled on ice. The resulting RNA extract was purified using the PicoPure® RNA Isolation Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purified RNA was subjected to RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) and real-time PCR analysis.

Total RNA extraction from in vitro cultured follicles

Follicles cultured in a 35 mm dish (10–30 follicles per dish) for 10 days were released from the GFR-Matrigel Matrix using Cell Recovery Solution (Corning, Corning, NY, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA was extracted from the released follicular cells using the PicoPure® RNA Isolation Kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted and purified RNA solutions were used for real-time PCR analysis.

RNA-sequencing data acquisition and analyses

Purified RNA solutions from the ovaries of CD-fed WT mice (n = 2), VOFD-fed Abcg5/g8 KO mice (n = 2), and CD-fed Abcg5/g8 KO mice (n = 3) were used for RNA-seq. RNA-seq was performed using an Illumina HiSeq 2500 in 100 bp paired-end mode, outsourced to Eurofins Genomics (Tokyo, Japan). Quantified read counts and differentially expressed genes were determined using RaNA-seq (a bioinformatics tool for the analysis of RNA-seq data59; https://ranaseq.eu/index.php) based on an adjusted p-value of <0.05 and fold change of >1.5 or <0.66. Phenotype enrichment and Gene Ontology (GO) biological process analyses were conducted using Enrichr (a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis tool60,61,62; https://maayanlab.cloud/Enrichr).

Search for common genome-binding factors for specific gene sets

The ChIP-Atlas-Enrichment Analysis online tool was used to find common genome-binding factors (transcription factors and others) in the genome region (−5000 bp to +5000 bp around the transcription start site) of the downregulated genes in the ovaries of infertile Abcg5/g8 KO mice, as revealed by RNA-seq analysis. The significance threshold was selected as greater than 50 based on the peak caller MACS2 score (−10 × Log10 [MACS2 Q-value]) which means that peaks with a MACS2 Q-value (FDR) lower than 1 × 10-5 were considered. A list of all genes detected in the mouse ovary, except for the genes downregulated in Abcg5/g8 KO mice, was set as a control (referential) gene list.

Quantification of mRNA levels

The extracted total RNA was reverse-transcribed using ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Master Mix (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). qPCR was performed using SYBR Green ER qPCR SuperMix Universal (Life Technologies, Tokyo, Japan) and the Eco Real-Time PCR System (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 15 s and at 60°C for 1 min. The primer sets used for qPCR are listed in Supplementary Table 6.

Quantification of H3K27me3 levels in the ovary

Histone extraction from the ovaries was performed using a histone extraction kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. H3K27me3 levels in the extracted histones (200 ng/sample) were quantified using a Histone H3 (trimethyl K27) Quantification Kit (Abcam) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Quantification of female hormones in mice

The concentration of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), FSH, luteinizing hormone (LH), estradiol, and progesterone in the serum and ovarian homogenate extraction were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit for gonadotropin-releasing hormone (USCN Life Science, Wuhan, China), ELISA kit for follicle stimulating hormone (USCN Life Science), ELISA kit for luteinizing hormone (USCN Life Science), Estradiol EIA kit (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), and Progesterone EIA kit (Cayman Chemical), respectively.

Collection of human serum specimens, clinical laboratory measurements, and assessment of good-quality blastocyst development rate in IVF patients

Experiments using human samples were conducted according to the study protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Tokyo (Approval No. 0325), after obtaining informed consent from all subjects. Serum samples were obtained 2–3 days before egg retrieval from 21 outpatients aged <40 years who underwent IVF at The University of Tokyo Hospital between July 2018 and December 2019, and were used to quantify phytosterols. Clinical laboratory variables related to IVF, such as basal levels of FSH, LH, estradiol, and anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), were obtained by routine biochemical testing. Fertilized eggs were cultured to the blastocyst stage and evaluated according to Gardner’s criteria63. Blastocyst development rates were calculated as the number of blastocysts with a grade of 3BC or 3CB, or better, divided by the number of normal fertilized eggs with 2PN.

Statistics and reproducibility

All data are expressed as the mean ± S.D. Individual data are shown in all graphs, and at least two independent biological replicates were used for each experiment. Statistical analyses indicated in each figure or table legend were conducted using GraphPad Prism 8 software, and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Raw data of RNA-seq analyses have been deposited on GEO with accession number GSE279573. All other data are available in the main text or Supplementary Materials. All source data in this study are available upon reasonable request, and the source data for the graphs in the figures are provided in the Supplementary Data file.

References

Wasilewski, T., Lukaszewicz-Zajac, M., Wasilewska, J. & Mroczko, B. Biochemistry of infertility. Clin. Chim. Acta 508, 185–190 (2020).

Committee on Gynecologic Practice American Sociesty for Reproductive Medicine. Infertility workup for the Women’s health specialist: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 781. Obstet. Gynecol. 133, e377–e384 (2019).

Ishihara, O. et al. Assisted reproductive technology in Japan: a summary report for 2018 by the Ethics Committee of the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Reprod. Med. Biol. 20, 3–12 (2021).

Salvaleda-Mateu, M., Rodriguez-Varela, C. & Labarta, E. Do popular diets impact fertility? Nutrients 16, 1726 (2024).

Cristodoro, M., Zambella, E., Fietta, I., Inversetti, A. & Di Simone, N. Dietary patterns and fertility. Biology 13, https://doi.org/10.3390/biology13020131 (2024).

Kohil, A. et al. Female infertility and diet, is there a role for a personalized nutritional approach in assisted reproductive technologies? A narrative review. Front. Nutr. 9, 927972 (2022).

Gaskins, A. J. & Chavarro, J. E. Diet and fertility: a review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 218, 379–389 (2018).

Berge, K. E. et al. Accumulation of dietary cholesterol in sitosterolemia caused by mutations in adjacent ABC transporters. Science 290, 1771–1775 (2000).

Graf, G. A. et al. Coexpression of ATP-binding cassette proteins ABCG5 and ABCG8 permits their transport to the apical surface. J. Clin. Invest. 110, 659–669 (2002).

Yu, L. et al. Overexpression of ABCG5 and ABCG8 promotes biliary cholesterol secretion and reduces fractional absorption of dietary cholesterol. J. Clin. Invest. 110, 671–680 (2002).

Yu, L. et al. Disruption of Abcg5 and Abcg8 in mice reveals their crucial role in biliary cholesterol secretion. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 16237–16242 (2002).

Solca, C., Tint, G. S. & Patel, S. B. Dietary xenosterols lead to infertility and loss of abdominal adipose tissue in sterolin-deficient mice. J. Lipid Res. 54, 397–409 (2013).

Altmann, S. W. et al. Niemann-Pick C1 Like 1 protein is critical for intestinal cholesterol absorption. Science 303, 1201–1204 (2004).

Garcia-Calvo, M. et al. The target of ezetimibe is Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1 (NPC1L1). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 8132–8137 (2005).

Yamanashi, Y., Takada, T. & Suzuki, H. Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 overexpression facilitates ezetimibe-sensitive cholesterol and beta-sitosterol uptake in CaCo-2 cells. J. Pharm. Exp. Ther. 320, 559–564 (2007).

Matsuo, M., Ogata, Y., Yamanashi, Y. & Takada, T. ABCG5 and ABCG8 are involved in vitamin K transport. Nutrients 15, 998 (2023).

Narushima, K., Takada, T., Yamanashi, Y. & Suzuki, H. Niemann-pick C1-like 1 mediates alpha-tocopherol transport. Mol. Pharm. 74, 42–49 (2008).

Takada, T. et al. NPC1L1 is a key regulator of intestinal vitamin K absorption and a modulator of warfarin therapy. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 275ra223 (2015).

Yamanashi, Y., Takada, T., Yamamoto, H. & Suzuki, H. NPC1L1 facilitates sphingomyelin absorption and regulates diet-induced production of VLDL/LDL-associated S1P. Nutrients 12, 2641 (2020).

Manabe, Y. et al. Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 promotes intestinal absorption of siphonaxanthin. Lipids 54, 707–714 (2019).

Davis, H. R. Jr. et al. Niemann-Pick C1 Like 1 (NPC1L1) is the intestinal phytosterol and cholesterol transporter and a key modulator of whole-body cholesterol homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 33586–33592 (2004).

Yu, L., von Bergmann, K., Lutjohann, D., Hobbs, H. H. & Cohen, J. C. Selective sterol accumulation in ABCG5/ABCG8-deficient mice. J. Lipid Res. 45, 301–307 (2004).

Mitsche, M. A., McDonald, J. G., Hobbs, H. H. & Cohen, J. C. Flux analysis of cholesterol biosynthesis in vivo reveals multiple tissue and cell-type specific pathways. Elife 4, e07999 (2015).

Byskov, A. G., Andersen, C. Y. & Leonardsen, L. Role of meiosis activating sterols, MAS, in induced oocyte maturation. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 187, 189–196 (2002).

Marin Bivens, C. L. et al. Meiosis-activating sterol promotes the metaphase I to metaphase II transition and preimplantation developmental competence of mouse oocytes maturing in vitro. Biol. Reprod. 70, 1458–1464 (2004).

Piunti, A. & Shilatifard, A. The roles of Polycomb repressive complexes in mammalian development and cancer. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 326–345 (2021).

Alexandrova, E. et al. Interaction proteomics identifies ERbeta association with chromatin repressive complexes to inhibit cholesterol biosynthesis and exert an oncosuppressive role in triple-negative breast cancer. Mol. Cell Proteom. 19, 245–260 (2020).

Wan, L. et al. Phosphorylation of EZH2 by AMPK suppresses PRC2 methyltransferase activity and oncogenic function. Mol. Cell 69, 279–291.e275 (2018).

Kong, Y. et al. Inhibition of EZH2 enhances the antitumor efficacy of metformin in prostate cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 19, 2490–2501 (2020).

Tang, G. et al. Metformin inhibits ovarian cancer via decreasing H3K27 trimethylation. Int. J. Oncol. 52, 1899–1911 (2018).

Chen, Q., Thompson, J., Hu, Y., Das, A. & Lesnefsky, E. J. Metformin attenuates ER stress-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. Transl. Res. 190, 40–50 (2017).

Jesch, E. D. & Carr, T. P. Food ingredients that inhibit cholesterol absorption. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 22, 67–80 (2017).

Nes, W. D. Biosynthesis of cholesterol and other sterols. Chem. Rev. 111, 6423–6451 (2011).

Calpe-Berdiel, L., Escola-Gil, J. C. & Blanco-Vaca, F. New insights into the molecular actions of plant sterols and stanols in cholesterol metabolism. Atherosclerosis 203, 18–31 (2009).

Shen, M. et al. Phytosterols: physiological functions and potential application. Foods 13, 1754 (2024).

Yuan, L., Zhang, F., Shen, M., Jia, S. & Xie, J. Phytosterols suppress phagocytosis and inhibit inflammatory mediators via ERK pathway on LPS-triggered inflammatory responses in RAW264.7 macrophages and the correlation with their structure. Foods 8, 582 (2019).

Yang, C. et al. Disruption of cholesterol homeostasis by plant sterols. J. Clin. Invest. 114, 813–822 (2004).

Sanchez, E. G. et al. Low progesterone levels and ovulation by ultrasound assessment in infertile patients. JBRA Assist. Reprod. 20, 13–16 (2016).

Tsafriri, A. & Motola, S. Are steroids dispensable for meiotic resumption in mammals? Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 18, 321–327 (2007).

Grondahl, C. et al. Meiosis-activating sterol-mediated resumption of meiosis in mouse oocytes in vitro is influenced by protein synthesis inhibition and cholera toxin. Biol. Reprod. 62, 775–780 (2000).

Mouzat, K. et al. Emerging roles for LXRs and LRH-1 in female reproduction. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 368, 47–58 (2013).

Ragazzini, R. et al. EZHIP constrains Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 activity in germ cells. Nat. Commun. 10, 3858 (2019).

Yang, Y. & Li, G. Post-translational modifications of PRC2: signals directing its activity. Epigenetics Chromatin 13, 47 (2020).

Li, Z., Ou, Y., Zhang, Z., Li, J. & He, Y. Brassinosteroid signaling recruits histone 3 lysine-27 demethylation activity to FLOWERING LOCUS C chromatin to inhibit the floral transition in arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 11, 1135–1146 (2018).

Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Role of metformin for ovulation induction in infertile patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS): a guideline. Fertil. Steril. 108, 426–441 (2017).

Marshall, J. C. & Dunaif, A. Should all women with PCOS be treated for insulin resistance? Fertil. Steril. 97, 18–22 (2012).

van Houten, E. L. & Visser, J. A. Mouse models to study polycystic ovary syndrome: a possible link between metabolism and ovarian function? Reprod. Biol. 14, 32–43 (2014).

Bouazzi, L., Sproll, P., Eid, W. & Biason-Lauber, A. The transcriptional regulator CBX2 and ovarian function: a whole genome and whole transcriptome approach. Sci. Rep. 9, 17033 (2019).

van Wijnen, A. J. et al. Biological functions of chromobox (CBX) proteins in stem cell self-renewal, lineage-commitment, cancer and development. Bone 143, 115659 (2021).

Tada, H. et al. Sitosterolemia, hypercholesterolemia, and coronary artery disease. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 25, 783–789 (2018).

Lek, M. et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 536, 285–291 (2016).

Ellegard, L. H., Andersson, S. W., Normen, A. L. & Andersson, H. A. Dietary plant sterols and cholesterol metabolism. Nutr. Rev. 65, 39–45 (2007).

Rocha, V. Z., Tada, M. T., Chacra, A. P. M., Miname, M. H. & Mizuta, M. H. Update on sitosterolemia and atherosclerosis. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 25, 181–187 (2023).

Kanaji, T., Kanaji, S., Montgomery, R. R., Patel, S. B. & Newman, P. J. Platelet hyperreactivity explains the bleeding abnormality and macrothrombocytopenia in a murine model of sitosterolemia. Blood 122, 2732–2742 (2013).

Rees, D. C. et al. Stomatocytic haemolysis and macrothrombocytopenia (Mediterranean stomatocytosis/macrothrombocytopenia) is the haematological presentation of phytosterolaemia. Br. J. Haematol. 130, 297–309 (2005).

Toyoda, Y., Takada, T. & Suzuki, H. Halogenated hydrocarbon solvent-related cholangiocarcinoma risk: biliary excretion of glutathione conjugates of 1,2-dichloropropane evidenced by untargeted metabolomics analysis. Sci. Rep. 6, 24586 (2016).

Nakagata, N., Sztein, J. & Takeo, T. The CARD method for simple vitrification of mouse oocytes: advantages and applications. Methods Mol. Biol. 1874, 229–242 (2019).

Babayev, E., Xu, M., Shea, L. D., Woodruff, T. K. & Duncan, F. E. Follicle isolation methods reveal plasticity of granulosa cell steroidogenic capacity during mouse in vitro follicle growth. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 28, https://doi.org/10.1093/molehr/gaac033 (2022).

Prieto, C. & Barrios, D. RaNA-Seq: interactive RNA-Seq analysis from FASTQ files to functional analysis. Bioinformatics, btz854 https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btz854 (2019).

Chen, E. Y. et al. Enrichr: interactive and collaborative HTML5 gene list enrichment analysis tool. BMC Bioinforma. 14, 128 (2013).

Kuleshov, M. V. et al. Enrichr: a comprehensive gene set enrichment analysis web server 2016 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W90–W97 (2016).

Xie, Z. et al. Gene set knowledge discovery with Enrichr. Curr. Protoc. 1, e90 (2021).

Gardner, D. K., Lane, M., Stevens, J., Schlenker, T. & Schoolcraft, W. B. Blastocyst score affects implantation and pregnancy outcome: towards a single blastocyst transfer. Fertil. Steril. 73, 1155–1158 (2000).

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Naomi Nakagata and Toru Takeo at Kumamoto University for providing instructions on the IVF procedures. This work was supported by grants from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (grant number JP20gm5910028 to Y.Y., JP23gn0110069 and JP23lk0310083 to Y.H., and JP23gn0110056 to Y.O.), the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) (KAKENHI; grant numbers 24K02852, 24K22202, and 20H04100 to Y.Y., 19J14316 to T.K., 22H02538 to Y.H., and 22H03222 to Y.O.), the Lotte Foundation (Lotte Research Promotion grant to Y.Y.), and the Takeda Science Foundation (Pharmaceutical Research Grants to Y.Y.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.Y. and T.T.; Methodology: Y.Y., T.K., and Y.H.; Investigation: Y.Y. and T.K.; Visualization: Y.Y. and T.K.; Funding acquisition: Y.Y., T.K., Y.H., and Y.O.; Project administration: Y.Y., H.S., Y.H., Y.O., and T.T.; Supervision: Y.Y., H.S., and T.T.; Writing—original draft: Y.Y. and T.K.; Writing—review & editing: Y.H. and T.T.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information