Abstract

Chromosomal rearrangements can drive adaptive evolution; however, whether the rearrangements in non-coding and non-promoter regions can lead to new phenotypes under selective pressures remains unclear. Additionally, highly producing recombinant proteins is a key industrial task but poses stress on host cells. Therefore, it is desirable to investigate the role of chromosomal rearrangement in non-coding and non-promoter regions during high-yield recombinant protein phenotype formation. In this study, we utilize the Kluyveromyces marxianus strain as the host for recombinant protein production, with the recombinant fusion protein comprising leghemoglobin (LBA) and enhanced green fluorescent protein serving as a reporter. Iterative evolution is conducted to select high-yield strains using Cre-loxP mediated chromosomal rearrangement technology and high-throughput fluorescence intensity screening. The evolved strains exhibit ~seven-fold increase in fluorescence intensity and a 1.7-fold improvement in LBA yield, identified with chromosome VIII inversion and chromosomes III and V translocation. Introducing these rearrangements into wild-type strains significantly increase recombinant protein yield to about 1.5-fold. Cascade networks are reconstructed based on RNA-seq analysis to elucidate rearrangements’ impact on global metabolic processes. Our study confirms that chromosomal rearrangements in non-coding regions can establish adaptive phenotypes and provides new ways of engineering host cells to improve recombinant protein productivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chromosomal rearrangements, resulting from the reconnection of large DNA fragments after DNA breaks, comprise unbalanced structural variations characterized by gain or loss of DNA copy numbers, as well as balanced events, such as translocations and inversions, where the copy number remains unchanged1,2. Both the unbalanced and balanced rearrangements contribute to the phenotypic evolution of organisms2,3,4,5,6 and are frequently observed in human diseases and tumors7. In-depth explorations into the mechanisms of chromosomal rearrangements facilitating species evolution primarily focus on the unbalanced structural variation, such as newly formed genes6 and highly expressed fusion genes8 directly generated by the rearrangements, as well as the increased copy numbers of resistance genes9. The effects and mechanisms of balanced chromosomal rearrangements are less investigated10,11,12. Engineered chromosomal inversions based on Ty1 elements showed no fitness advantage or disadvantage in either rich or minimal media11. Translocation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (S. cerevisiae) between Chr XV and Chr XVI involving the promoters of genes ADH1 and SSU110, and an inversion in Chr XVI involving the promoters of SSU1 and GCR112, both enhanced the adaptation to sulfite. However, the impact of balanced chromosomal rearrangements in prevalent non-coding regions (excluding promoters) on cellular function and their potential to establish new phenotypes remain unclear.

Using yeasts for high-yield recombinant protein production is a central task in the industry. Currently, modifying a single gene or a few genes can significantly enhance recombinant protein yields13,14,15. However, employing large-scale chromosomal rearrangements to improve these yields has not yet been reported. On the other hand, the high production of recombinant proteins can be toxic to cells15,16,17, which imposes selective pressure on the host. Additionally, during industrial fermentation, vigorous aeration and stirring generate large amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS), which are toxic to the strains and impair cell viability18. Therefore, it is desirable to enhance strains’ recombinant protein productivity while also increasing their resistance to ROS in the environment.

Cre-loxP is a site-specific chromosomal recombination technology that involves Cre recombinase and loxP sites. The Cre recombinase recognizes integrated loxP sites in the genome, facilitating chromosomal rearrangement19. Currently, a synthetic chromosome recombination and modification by LoxP-mediated evolution system based on Cre-loxP has been established for S. cerevisiae, enabling the rearrangements of synthetic chromosomes20 and the entire genome21. By inducing chromosomal rearrangements in S. cerevisiae22, improved industrial phenotypes have been selected, including the production of novel drug molecules, increased tolerance to environmental stresses, and higher growth rates on xylose media20. These studies establish a substantial foundation for improving recombinant protein productivity via chromosomal rearrangements.

Kluyveromyces marxianus (K. marxianus) is a novel yeast known for its food-grade safety, rapid growth, high-temperature tolerance, and ability to utilize various carbon sources23,24. It has successfully achieved efficient production of various industrial enzymes and virus-like particles14,25. Previously, we established a Cre-loxP-based technique to induce chromosomal rearrangements in K. marxianus19. Specifically, we randomly selected two loxP sites on each of the eight chromosomes of the wild-type strain, positioning each site after the coding sequences (CDS) of two oppositely oriented genes. Then, the CRISPR technology was employed to insert these loxP sites, resulting in the created strain LHP1044, which contains a total of 16 loxP sites. The Cre recombinase facilitates both inversions and translocations19.

To address the above issues, this study utilized K. marxianus as the host to achieve high production levels of a recombinant fusion protein comprising leghemoglobin (LBA) and enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP), which serves as the reporter. Iterative evolution was conducted using two strategies in an environment conducive to chromosomal rearrangements occurring in non-coding regions, facilitated by the Cre-loxP system. Strategy 1 relied on high-yield recombinant protein production as the sole stressor, while Strategy 2 used high -yield recombinant protein production and H2O2 as both stressors. Following seven rounds of iterations, fluorescence intensity increased by 8.1-fold and 6.7-fold with the two strategies, respectively. The high-yield strains from Strategies 1 and 2 underwent inversion of Chr VIII and translocation between Chr III and Chr V, respectively, and exhibited stable inheritance. Introducing these rearrangements into wild-type strains can significantly enhance recombinant protein yields. RNA-seq analysis revealed that the rearrangements may directly activate cAMP signaling pathway, strengthen mitochondrial functions and the respiratory chain. These changes may cascade to impact global cellular metabolism and provide sufficient energy and materials for recombinant protein production. The inferred elevated cAMP, ATP, and acetyl-CoA levels were ultimately validated through experiments.

Results

Improved recombinant protein yields in strains were achieved through iterative evolution screening via two strategies

The K. marxianus strain LHP1044 was used as the starting strain19, featuring two loxP sites on each chromosome (see Supplementary Table 1), located in the regions after the CDS of two oppositely oriented unessential genes. To minimize the impact of the recombination site on cellular function, the loxP sites were manually positioned primarily near genes encoding ribosomes.

Using the fusion protein LBA-eGFP as a reporter, two iterative screening strategies based on the action of Cre recombinase were employed to ultimately obtain evolved strains that produce high levels of recombinant protein (Fig. 1). Strategy 1 used high-yield recombinant protein as the sole selection pressure, while Strategy 2 employed it as the primary stressor alongside 10 mM H2O2 as the secondary stressor. This concentration of H2O2 is critical for the survival of Cre recombinase-expressing strains (Supplementary Fig. 1). Each round of the screening process is depicted in Fig. 1. The starting strains first undergo Cre recombinase treatment, after which they are cultivated either without H2O2 (Strategy 1) or with H2O2 (Strategy 2). Subsequently, the Cre plasmid is removed, and the strains are incubated on petri dishes, followed by three steps of screening to finally isolate 1–5 clones with the highest fluorescence intensity (see “Methods”). If their fluorescence intensity is greater than that of the initial mixed strains in the current round, the top clones are selected, preserved, and then mixed together as the starting strains for the next round; otherwise, the iterative evolution process is terminated.

LHP1044 was utilized as the starting strain, with 16 loxP sites on genomes. The fusion protein LBA-eGFP was used as a reporter of recombinant protein. Two strategies were employed to ultimately obtain evolved strains producing high levels of recombinant protein. Strategy 1 utilizes Cre recombinase without applying H2O2, while Strategy 2 employs Cre recombinase along with 10 mM H2O2 as the secondary selection pressure. For each round of screening process, the starting strains first undergo Cre recombinase treatment, then cultivated either without H2O2 (Strategy 1) or with H2O2 (Strategy 2). Subsequently, the Cre plasmid is removed, and the strains are incubated on petri dishes, followed by three steps of screening to finally isolate 1–5 monoclonal clones with the highest fluorescence intensity. Specifically, in the primary screening, petri dishes are exposed to irradiation from excitation light source (wavelength 488 nm) to identify clones exhibiting high fluorescence intensity. From each petri dish, the top 1–5 clones are selected and transferred to a 96-deep-well plate for subsequent cultivation. In the secondary screening, following a 72 h growth period in the 96-deep-well plate, fluorescence intensity is measured using a multifunctional microplate reader. Clones showing at least a 50% increase in fluorescence intensity compared to strain LHP1044 are chosen for further cultivation in shake flask. In the tertiary screening, clones cultivated in shaking flasks for 72 h are further measured by the multifunctional microplate reader. If there is an increase in the fluorescence intensity, the top 1–5 clones displaying the highest fluorescence intensity are selected, preserved, and then mixed together as the starting strains for the next screening round. If there is no increase in fluorescence intensity, the iterative screening process is terminated.

The results from the primary screening (Fig. 2A, B, 96-well plate cultivation) demonstrate that as the number of iterations increases, the distribution of recombinant protein expression levels among the clones broadens. Notably, compared to Strategy 1, Strategy 2 exhibits a broader range of clone diversity starting from the 2nd round, peaking by the 5th round, after which its diversity decreases and approaches stability. In contrast, Strategy 1 reaches maximum clone diversity by the 7th round. This suggests that the stressor H2O2 may accelerate the evolution of high yields of recombinant protein.

A Relative fluorescence intensity of strains selected from primary screening cultivated in 96-deep-well plates during Strategy 1 screening. For Round 1, n = 690; for Round 2, n = 464; for Round 3, n = 455; for Round 4, n = 279; for Round 5, n = 212; for Round 6, n = 516; and for Round 7, n = 356. B Relative fluorescence intensity of strains selected from primary screening cultivated in 96-deep-well plates during Strategy 2 screening. For Round 1, n = 460; for Round 2, n = 396; for Round 3, n = 882; for Round 4, n = 353; for Round 5, n = 216; for Round 6, n = 567; and for Round 7, n = 372. C Relative fluorescence intensity of strains selected from shake-flask in Strategy 1 screening. Values for fluorescence intensity are presented as average ± SD, n = 3. D SDS-PAGE evaluation of fusion protein production for high-yield strains obtained from Strategy 1. The grayscale values are presented below each lane. E Relative fluorescence intensity of strains selected from shake-flask in Strategy 2 screening. Values for fluorescence intensity are presented as average ± SD, n = 3. F SDS-PAGE evaluation of fusion protein production for high-yield strains obtained from Strategy 2. The grayscale values are presented below each lane. The strains from Strategy 1 and Strategy 2 are named as ‘‘Round-C’’ and ‘‘Round-H,’’ respectively, followed by the clone number.

According to the fluorescence intensity results from the tertiary screening (Fig. 2C, E, shake flask), strains obtained from Strategies 1 and 2 achieved the highest fluorescence intensity with increases of 8.1-fold (Fig. 2C) and 6.7-fold (Fig. 2E) compared to strain LHP1044, respectively. In particular, Strategy 2 reached fluorescence intensity of 2.8-fold and 5.4-fold in the 2nd and 4th rounds of screening, respectively, whereas Strategy 1 achieved only 1.3-fold and 2.8-fold in the corresponding rounds. This is accordant with the results from the 96-well plate cultivation. We further validated the yields of the fusion protein from these selected strains using SDS-PAGE (Fig. 2D, F), with the grayscale values presented below each lane. The protein yields were consistent with fluorescence intensities, showing the highest grayscale values of LBA-eGFP with increases of 3.8-fold and 2.4-fold in strategies 1 and 2, respectively. Note that the increase in the grayscale values (Fig. 2D, F) is not as great as the increase in the fluorescence intensity (Fig. 2C, E). This may be attributed to the discrepancy between the fluorescence measurement system and the grayscale measurement system, or it could be due to the decline in high-yield capacity of these strains after being stored for a certain period prior to SDS-PAGE analysis. Nevertheless, a positive correlation still exists between the fluorescence intensity and protein quantity. In brief, following seven rounds of iterative evolution, a total of 23 high-yield strains were obtained from Strategies 1 and 2.

To verify the universal high-yield capability of the evolved strains for recombinant protein production, these 23 strains were stripped of the LBA-eGFP fusion plasmid, and then recombinantly expressed LBA (Fig. 3A). Taking into account the LBA production and the goal of covering as many rounds as possible, 13 (labeled in red font in Fig. 3A) out of the 23 strains were selected for further investigation. Subsequently, the 13 strains were individually recombinantly expressed with melibiose esterase Mel1 from Rhizomucor miehei (Fig. 3B), glucanase Badgla from Arxula adeninivorans (Fig. 3C), and feruloyl esterase AnFaeA from Aspergillus niger (Fig. 3D). Although all the 13 strains demonstrated increased recombinant protein expressions compared to the original strain LHP1044, they exhibited lower productivity for LBA alone, with the highest increase of 1.7-fold (Fig. 3A), compared to the 3.8-fold increase for the LBA-eGFP fusion (Fig. 2D, F). This decrease may be attributed to the instability of the newly formed phenotype or to the expression assistance provided by eGFP, which is a readily expressible protein. Additionally, these 13 strains, stripped of the LBA-eGFP fusion plasmid, demonstrated a globally higher expression capacity for Mel1 and Badgla compared to LBA, suggesting a distinct preference for recombinant proteins. Moreover, strain 5-C12 exhibited prominently higher expression of AnFaeA compared to other strains, indicating its strain-specific characteristics. Since the aim of this study is to investigate the general effect of balanced chromosomal rearrangement on recombinant protein productivity, we will not delve further into these particularities in protein preference and strain specificity. Overall, the 13 evolved strains demonstrated universal high-yield production capabilities for various proteins.

All the strains were stripped of the LBA-eGFP fusion plasmid. A Relative expression of the recombinant protein LBA in 23 strains. The selected strains are highlighted in red font. B Relative activity of the recombinantly expressed β-galactosidase Mel1 in the selected 13 strains. C Relative activity of the recombinantly expressed glucosidase Badgla in the selected 13 strains. D Relative activity of the recombinantly expressed feruloyl esterase AnFaeA in the selected 13 strains. Values are expressed as average ± SD, n = 3.

In terms of H2O2 tolerance, the 23 high-yield recombinant protein strains obtained from Strategies 1 and 2 did not show significant differences in their ability to resist H2O2 compared to strain LHP1044 (Supplementary Fig. 2). It implies that evolution under two stressors does not necessarily result in a phenotype that simultaneously tolerates both selection pressures. This is concordant with the previous report indicating that when adaption to multiple stressors, populations cannot optimally perform multiple tasks (i.e. adapting to each stressor), leading to a bias toward one particular stressor26.

Identification of chromosomal rearrangements and stability analysis

To assess chromosomal rearrangements in the 13 evolved strains and to understand the specific types of rearrangements, 16 pairs of primers were designed (Supplementary Table 4) targeting the 16 loxP sites in strain LHP1044 (Supplementary Table 1). Each pair of primers was located ~500 bp upstream and downstream of the loxP sites. If a specific site can be amplified to produce the expected band, it indicates that no rearrangement has occurred; conversely, the absence of amplification suggests that a rearrangement has taken place at that site.

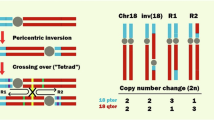

The genomic PCR results are presented in Fig. 4A, seven strains (4-C13, 6-C21, 6-C3, 7-C1, 4-H19, 5-H10, and 5-H14) showed no rearrangement, while six strains (5-C12, 7-C2, 6-H13, 7-H4, 7-H5, and 7-H9) exhibited chromosomal rearrangements. Among the rearranged strains, strain 7-C2, obtained from Strategy 1, exhibits rearrangements occurring at sites 1 and 15 (Fig. 4A), both located on Chr VIII. The rearrangement between sites 1 and 15 were further validated by PCR (Fig. 4B), confirming an inversion on Chr VIII. Strains 6-H13, 7-H4, and 7-H5, obtained from Strategy 2, exhibit rearrangements at sites 7 and 11 (Fig. 4A), which are located on Chr III and Chr V, respectively. The rearrangement of sites 7 and 11 were validated by PCR (Fig. 4B), indicating a translocation between Chr III and Chr V. Additionally, strains 5-C12 and 7-H9 underwent rearrangements solely at locus 16 and locus 1 (Fig. 4A), respectively. This suggests that gene loss or amplification may have occurred near the single rearrangement site, or that rearrangement at this site may involve interactions with other unknown sites in the genome. This aspect falls outside the scope of this study, which focuses on chromosomal rearrangement between given sites; therefore, these two strains are not considered further. In summary, the strains evolved through Strategy 1 primarily experienced an inversion on Chr VIII, while the strains evolved through Strategy 2 mainly underwent a translocation involving Chr III and Chr V.

A Genomic PCR for the 13 strains. The PCR results for 16 pairs of primers targeting the 16 loxP sites are arranged in separate lanes. Seven strains (4-C13, 6-C21, 6-C3, 7-C1, 4-H19, 5-H10, and 5-H14) showed no rearrangement, two strains (5-C12 and 7-H9) exhibited solely one rearrangement site, and four strains (7-C2, 6-H13, 7-H4, 7-H5) exhibited two rearrangement sites. B PCR validation for the rearrangements. For strain 7-C2, the primer pair 1-F and 15-F successfully amplified the target band, suggesting that an inversion has occurred within Chr VIII. Strains 6-H13, 7-H4, and 7-H5 showed amplification with the primer pair 7-F and 11-R, indicating a translocation between Chr III and Chr V.

We further conducted stability tests on the strains 7-C2 and 7-H4 through stress-free passaging. Every ten generations (~every 24 h by default), we transferred the strains and measured their OD600 to assess cell growth. During the consecutive passages of 100 generations, cells retained stable growth (Supplementary Fig. 3A, B). PCR identification was then conducted on the genomic DNA extracted from samples at 50 and 100 generations (Supplementary Fig. 3C, D), showing that strains 7-C2 and 7-H4 could still successfully produce the inversion and translocation bands, respectively. This demonstrates that the rearranged chromosomes in the evolved strains can be stably inherited.

Chromosomal rearrangements indeed enhance the recombinant protein productivity of strains

To ascertain that the elevated recombinant protein productivity in the rearranged strains is primarily due to chromosomal rearrangements rather than earlier accumulated epigenetic alterations or SNPs, we introduced these rearrangements into the wild-type K. marxianus strain FIM1. Specifically, we first constructed the rearrangement precursor strain AY-45, which contains the loxP sites on Chr VIII for inversion, and then constructed the rearranged strain Inv-45 with the completed inversion. We also created the precursor strain AY-23, which contains the loxP sites on Chr III and Chr V for translocation, along with the rearranged strain Tra-23 with finished translocation. The rearranged strains Inv-45 and Tra-23 exhibited significant increases in recombinant protein LBA production compared to their respective precursor strains AY-45 and AY-23 (Fig. 5A), with a 1.5-fold increase. This is consistent with the 1.7-fold increase in LBA production observed in the evolved strains (Fig. 3A).

A Comparison of recombinant protein LBA production in engineered strains before and after chromosomal rearrangement. B Comparison of LBA production in constructed strains before and after chromosomal rearrangement, founded on the CYR1N1546K mutation. C Relative fluorescence intensity of engineered strains before and after chromosomal rearrangement. D Comparison of growth curves between engineered strains before and after chromosomal rearrangements. E Enriched GO pathways of differentially expressed genes in Inv-45. Red and green bars represent the upregulated and downregulated genes, respectively. F Enriched GO pathways of differentially expressed genes in Tra-23. Purple and blue bars represent the upregulated and downregulated genes, respectively. Values are presented as average ± SD, n = 3. **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001.

In our previous study15, we identified that a mutation in the adenylate cyclase CYR1 enhances K. marxianus’ capability to produce recombinant proteins. Building on this, we began with the strain CYR1N1546K, which carries this mutation, and introduced the inversion and translocation, resulting in strains CYR1N1546K-Inv and CYR1N1546K-Tra, respectively. The LBA yields of these strains were significantly higher compared to CYR1N1546K (Fig. 5B), underscoring the capacity of chromosomal rearrangements to augment a strain’s proficiency in producing recombinant proteins.

Furthermore, the LBA-eGFP fusion plasmid was transferred into the strains AY-45, AY-23, Inv-45, and Tra-23, resulting in the fluorescence intensity significantly increased by ~1.8-fold (Fig. 5C), which is less pronounced than the roughly 7-fold enhancement observed in the freshly evolved strains (Fig. 2C, E). This implies that the regression of high-yield productivity is not primarily attributable to the expression assistance of eGFP; rather, it may stem from the inherent instability of the newly formed strains themselves. Nevertheless, the chromosomal rearrangements did significantly improve the production of recombinant proteins (Fig. 5A–C).

RNA-seq analysis reveals potential mechanisms of chromosomal inversion and translocation for enhance chassis cells’ productivity

To analyze how chromosomal inversion and translocation influence the chassis cells for producing recombinant proteins, we first compared the cell morphology of the strains before and after the rearrangements, both without recombinant protein plasmid. Strains Inv-45 and Tra-23 exhibited slower growth than their respective precursor strains AY-45 and AY-23, with no noticeable difference in growth between Inv-45 and Tra-23 (Fig. 5D).

Next, we conducted RNA-seq analysis on the strains Inv-45 and Tra-23, as well as their precursors AY-45 and AY-23, during the logarithmic growth phase at 30 °C. The log2FoldChange values of gene expression were calculated by comparing the rearranged strains to their precursor strains, as listed in Supplement Data 1 and Data 2. Using the traditional criteria for differential gene identification (|log2FoldChange|> = 1), only two upregulated and 14 downregulated genes were identified for inversion, while 71 upregulated and eight downregulated genes were identified for translocation. The limited number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) restricts the ability to capture the overall internal state changes in the rearranged cells. Previous studies have recognized that changes in a cell’s global state can arise from the accumulation of subtle expression variations across many genes27,28,29. Therefore, in this study, we adjusted our criteria for differential genes to |log2FoldChange| ≥ 0.5 and |Cohen’s d-value|>0.8, ensuring that the identified differential expressions are meaningful and not a result of random fluctuations. And there are 41 upregulated and 243 downregulated genes in Inv-45 (enriched GO pathways shown in Fig. 5E), and 215 upregulated and 21 downregulated genes in Tra-23 (enriched GO pathways presented in Fig. 5F). Relying on the GO analysis alone cannot reveal clear mechanisms that enhance the rearranged strains’ ability to produce recombinant protein. Therefore, in the following, we will explore in detail how chromosomal rearrangements cascade to influence the overall state of the chassis cells, commencing with the analysis of the changes in the rearranged chromosomes.

For the inversion analysis, Fig. 6A illustrates the 33 DEGs on the rearranged Chr VIII. It also provides the distance of each gene to the rearrangement site, along with annotations highlighting the primary cellular processes in which these genes are involved, based on their functional characteristics as described by UniProt. It was found that DEGs are distributed at varying distances from the rearrangement site (Fig. 6A), which is consistent with previous reports30. Studies on the three-dimensional conformation of chromosome have shown that during transcription initiation, chromosome spontaneously folds into localized, dense “chromatin globules”31,32. This folding facilitates long-range interactions between distant enhancers and promoters, thereby promoting gene transcription30. During this process, the time taken by DNA sites to encounter is largely independent of genomic distance30. Thus, our results support these findings from the perspective of chromosomal rearrangements.

A Cellular processes associated with differentially expressed genes on Chr VIII resulting from inversion. Chr VIII and Chr VIII’ represent chromosome VIII before and after the inversion, respectively. A total of 33 differentially expressed genes located on the rearranged Chr VIII are illustrated, with orange representing upregulation and green representing downregulation. The distance of each gene from the rearrangement site is provided below. The letters in each gene serve as an index for the cellular pathways in which it primarily participates. The red font highlights the key cellular processes. B Inversion-induced changes in global cellular metabolic pathways. This focuses on glucose metabolism. The blue circles represent metabolites, the arrows indicate metabolic reactions, and the rectangles represent differentially expressed gene involved in these reactions. Orange indicates upregulation, green indicates downregulation, and pink represents enhanced pathway. C The levels of cAMP, acetyl-CoA, and ATP before and after the inversion. Values are presented as average ± SD, n = 3. *: p < 0.05, ****: p < 0.0001. D The H2O2 resistance before and after the inversion.

For the cellular pathways involving the DEGs on the inverted Chr VIII (Fig. 6A), the upregulated genes are primarily involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and the respiratory chain. Additionally, the cAMP generation was also influenced by the downregulated gene RGS2 in the inverted region. RGS2 inactivates CYR1 in yeast by hydrolyzing GTP to GDP, while CYR1 converts ATP to cAMP; thus, downregulating RGS2 can promote cAMP generation33. Therefore, it can be inferred that mitochondrial biogenesis, the respiratory chain, and cAMP generation may be directly activated by chromosomal inversion.

We then analyzed the changes in overall cellular metabolism induced by inversion, centering on glucose metabolism. As shown in Fig. 6B, the glycolysis was downregulated in two steps involving genes PFK1 and PYK1. The pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) was downregulated in two steps involving genes TKL1 and TAL1. The branches from the PPP to nucleotide biosynthesis, aromatic amino acid biosynthesis, and tetrahydrofolate biosynthesis and interconversion were all downregulated. The branch from glycolysis to trehalose biosynthesis was also repressed, as indicated by the downregulation of PGM2 and TSL1. Pyruvate, the end product of glycolysis, typically enters the mitochondria to generate acetyl-CoA for the TCA cycle. While three steps in the TCA cycle were downregulated, the conversion of succinate to fumarate was upregulated, possibly due to its connection with the respiratory chain. In the mitochondria, the pathways from pyruvate to leucine biogenesis and to CoA biogenesis were downregulated. However, it is important to note that the consumption of acetyl-CoA in the cytoplasm was reduced, based on the downregulated gene MLS1, mediating the conversion of glyoxylate to malate. Since the inversion in Chr VIII may directly enhance cAMP generation by downregulating RGS2, and cAMP’s target protein kinase A in turn repress trehalose synthesis34, the observed downregulation of trehalose synthesis (Fig. 6B) confirms the activation of cAMP signaling.

Our previous study15 found that increased cAMP boosts mitochondrial function and the respiratory chain while simultaneously reducing ROS production35. Therefore, to validate the aforementioned speculations, we measured the levels of cAMP (Fig. 6C), ATP (Fig. 6C), acetyl-CoA (Fig. 6C), and H2O2 resistance (Fig. 6D) before and after the inversion of Chr VIII, during the logarithmic growth phase. The cAMP content in Inv-45 was significantly higher than in AY-45, ~4.5-fold greater, providing strong evidence that the inversion promotes cAMP generation. The significantly upregulated ATP values in AY-45 implies an enhanced respiratory chain, while the increased H2O2 resistance in Inv-45 suggests lower ROS generation within the cells. The significantly increased acetyl-CoA level in Inv-45 is likely the result of its repressed cytoplasmic consumption during the conversion of glyoxylate to malate. To sum up, the upregulation of cAMP, ATP, acetyl-CoA, and H2O2 resistance not only supports the strong reliability of the above molecular mechanism analysis, but also ensures an adequate supply of energy, material, and reducing power necessary for recombinant protein production.

For the translocation analysis, Fig. 7A depicts the 31 and 11 DEGs located on the rearranged chromosomes III and V, respectively. The distance of each gene to the rearrangement site, along with their primary cellular processes based on UniProt annotations, is provided. It also shows that DEGs are widely distributed across the rearranged chromosomes (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, the translocation resulted in the up-regulation of many genes on the rearranged chromosomes, while the genes located on both sides closest to the rearrangement sites were down-regulated.

A Cellular processes associated with differentially expressed genes on Chr III and Chr V resulting from translocation. B Translocation-induced changes in global cellular metabolic pathways. C The levels of cAMP, acetyl-CoA, and ATP before and after the translocation. Values are presented as average ± SD, n = 3. *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01. D The H2O2 resistance before and after the translocation. The figure legend is consistent with that of Fig. 6.

Notably, among the cellular processes illustrated in Fig. 7A, four genes related to mitochondrial biogenesis and six genes involved in glucose uptake were upregulated. Additionally, the genes CTT1 and GUT2, with anti-ROS activity in peroxisomes and mitochondria, were upregulated. Furthermore, the genes PUT1 and PUT2 involved in proline degradation within the mitochondria were also up-regulated. PUT1 converts proline into (S)-1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate (P5C), meanwhile transforming quinone (Q) to quinol (QH2) (Fig. 7B), thereby providing anti-ROS capability in the mitochondria. PUT2 transforms P5C to glutamate, concurrently converting NAD+ to NADH (Fig. 7B), which supplies electrons to the respiratory chain. Therefore, the upregulated proline degradation process may enhance both ROS resistance and the respiratory chain in mitochondria.

The impact of translocation on global cellular metabolism, particularly glucose metabolism, is analyzed below (Fig. 7B). For glucose uptake, six upregulated genes are located on the rearranged chromosomes. The increased glucose uptake may stimulate cells to enhance two pathways for generating extracellular glucose (Fig. 7B): upregulating the gene INU1 to facilitate inulin hydrolysis into glucose and fructose, and upregulating the gene LAC4 (located on the rearranged chromosome) to hydrolyze lactose into glucose and galactose. For intracellular glucose utilization, the glycolysis was upregulated in two steps, as indicated by the genes GLK1 and PFK26. In terms of glycolytic branches, the PPP remained unchanged, while lactose catabolism was enhanced by the upregulation of genes LAC4, GAL1, GAL7, and NPP1, likely as a result of increased LAC4 expression. Additionally, the pathway from glycerol to DHAP may be bolstered by the upregulated genes YPR1, GUT1, and GUT2, which facilitate the conversion of NADP+ to NADPH in the cytoplasm and the conversion of Q in QH2 in the mitochondria. In the mitochondria, the TCA cycle remained unchanged, while the conversion of ethanol to acetate was upregulated by the genes ADH3 and ALD5 (Fig. 7B). This upregulation may result in an increase in NADH and NADPH generation, as well as an increase in the production of acetyl-CoA.

Additionally, increases in glucose uptake can activate the glucose receptor GPR136, which in turn activates CYR1 independently of RAS237, thereby promoting cAMP production36. Therefore, cAMP signaling may be activated by the upregulated glucose uptake, and may result in boosted respiratory chain and reduced ROS generation15. To validate the above speculation regarding translocation, the levels of cAMP (Fig. 7C), ATP (Fig. 7C), acetyl-CoA (Fig. 7C), and H2O2 resistance (Fig. 7D) were measured before and after the translocation, during the logarithmic growth phase. The levels of cAMP, ATP, and acetyl-CoA in Tra-23 were significantly higher than those in AY-23, and the H2O2 resistance was also markedly increased in Tra-23. These findings provide strong support for the molecular derivations in the translocation analysis. It should be noted that, cAMP levels increased by 4.5-fold and 1.8-fold in inversion and translocation, respectively. Meanwhile, ATP levels rose by 1.4-fold and 2.3-fold in inversion and translocation, respectively. The more substantial increase of ATP in translocation may be attributed to enhanced QH2 and NADH generation in the mitochondria, which were boosted exclusively in Tra-23 and provides electrons to the respiratory chain.

Discussion

This study involved two fundamental biological questions in its experimental design. (1) Organisms are likely to encounter multiple stresses in their growth environments. During the evolutionary process under multiple stresses, can species evolve phenotypes that simultaneously adapt to various pressures? Additionally, how do the stresses influence each other? These questions remain unresolved. (2) Currently, most reported chromosomal rearrangements that positively influence the phenotypic formation of species involve unbalanced structural changes or alterations in promoter changes. However, the effects and potential mechanisms of balanced chromosomal rearrangements occurring in non-coding and non-promoter regions remains to be unraveled.

In this study, we attempted to approach the above two issues. We found that under the combined stresses of high recombinant protein production and H2O2, K. marxianus displayed a phenotype characterized solely by increased recombinant protein production, with no discernable improvement in H2O2 tolerance. This observation aligns with Orr et al.’s evolutionary experiments on Brachionus calyciflorus26, which showed that populations often experience trade-offs under multiple stressors, meaning that populations cannot adapt to all stressors, thereby generating a bias towards synergism. Additionally, Hiltunen et al. conducted experimental evolution using Pseudomonas fluorescens and its predator Tetrahymena thermophila, finding that the combination of predation pressure and sublethal antibiotic concentrations delayed the evolution of anti-predation defense and antibiotic resistance compared to situations where only one pressure was present38. It indicates that simultaneous selective pressures may slow the adaptive evolutionary rate of each other. In our study, we found that the combined pressures of recombinant protein production and H2O2 accelerated the evolution of recombinant protein yield (Fig. 2A, B). Therefore, the influence of multiple evolutionary pressures on each other’s processes should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

For balanced chromosomal rearrangements occurring in non-coding and non-promoter regions, the inversion and translocation can significantly enhance recombinant protein productivity in strains (Fig. 5A, B), indicating that such rearrangements can drive the emergence of new phenotypes in species. The potential cascading effects of these rearrangement were further elucidated: the inversion on Chr VIII may directly activate cAMP signaling (Fig. 6B), while the translocation between Chr III and Chr V may directly enhance glucose uptake, subsequently activating the cAMP signaling (Fig. 7B). The activated cAMP pathway may enhance the respiratory chain (Figs. 6C, 7C) and antioxidant capacity (Figs. 6D, 7D), providing sufficient energy and reducing power for recombinant protein production.

On the other hand, while evolving new phenotype under selective pressures, we encountered a problem: the degradation of recombinant protein production in the newly evolved strains. Specifically, the evolved strains carrying the LBA-eGFP fusion plasmid demonstrated fluorescence increases of 8.1-fold (Fig. 2C) and 6.7-fold (Fig. 2E) in strategy 1 and strategy 2, respectively, with protein grayscale values of LBA-eGFP rising by 3.8-fold (Fig. 2D) and 2.4-fold (Fig. 2F). However, after discarding the fusion plasmid, LBA expression alone increased only 1.7-fold (Fig. 3A). This may be attributed to the influence of eGFP on facilitating protein expression, or the instability of the newly evolved strains. To identify the possible causes, we reintroduced the LBA-eGFP fusion plasmid into the engineered strains, resulting in only a 1.8-fold increase in fluorescence (Fig. 5C), much lower than that the newly evolved strains (Fig. 2C, E). This indicates that the internal instability in these fresh strains is a major reason for the degradation of the high-yield phenotype. It is consistent with current knowledge39, which recognizes that phenotypic variation in most species populations is determined by two factors: genotypic difference and environmental conditions during trait formation, leading to phenotypic plasticity39. Therefore, the same genotype can yield different phenotypes under varying environments39. In this study, the newly evolved strains experienced environmental changes after removal from selective pressure and during the discarding of the fusion plasmid, potentially leading to a decline in high-yield of recombinant protein production. We conjecture that the phenotypic changes caused by environmental alterations are primarily mediated through epigenetic modifications, which are probably influenced by the surrounding environments40. Furthermore, PCR analysis revealed that chromosomal inversions and rearrangements occurred in the evolved strains (Fig. 4). These rearrangements remained stable during the pressure-free passaging, and their introduction into wild-type strains can significantly increase the recombinant protein yields (Fig. 5A). This indicates that inversion and translocation are crucial factors at the genotype level that enhance recombinant protein production. Additionally, since this study focuses on chromosomal rearrangements, our genomic analysis of the evolved strains primarily concentrated on the rearrangements occurring between the specified loci. We did not further investigate other genomic variations, such as SNPs or rearrangements occurring at unspecified locations.

Moreover, the newly evolved strains carrying the LBA-eGFP fusion plasmid did not demonstrate improved H2O2 tolerance compared to LHP1044 (Supplementary Fig. 2). In contrast, the engineered strains Inv-45 and Tra-23 exhibited obviously higher H2O2 resistance than the non-rearranged strains AY-45 and AY-23. To eliminate the possibility that this difference was due to the lower H2O2 tolerance of AY-45 and AY-23 compared to LHP1044, we conducted H2O2 resistance tests on these three strains (Supplementary Fig. 4) and found no differences in their H2O2 resistance capabilities. We speculate that the increased H2O2 tolerance in strains AY-45 and AY-23 may be linked to their lower recombinant protein yield compared to the newly evolved strains. High expression of recombinant proteins generates oxidative stress during protein folding41, consuming reducing power and thereby weakening the resistance to external H2O2. Therefore, when recombinant protein production is lower, the trade-off within the cells can allow an enhancement of reducing power used for resisting external H2O2. Besides, the translocations obtained from Strategy 2 can directly activate the anti-ROS pathways in both the cytoplasm and mitochondria (Fig. 7A, B), potentially serving as a molecular signature of the selection pressure exerted by H2O2 treatment.

Finally, we acknowledge that the selection of rearrangement loci and evolved strains for further investigation was somewhat arbitrary. The primary aim of this study was to illustrate that chromosomal rearrangements in non-coding and non-promoter regions can significantly enhance recombinant protein production and to propose potential cascading mechanisms. We hope that this work will lay a foundation for future systematic studies that leverage chromosomal rearrangements to achieve phenotypic improvements.

Methods

Strains and plasmids

The strains, plasmids, and primers used in this study are presented in Supplementary Tables 2–4. The starting strain for iterative evolution is K. marxianus strain LHP104419, which has two loxP sites on each chromosome, resulting in a total of 16 loxP sites across its eight chromosomes (Supplementary Table 1). Each site is located after CDS of two oppositely oriented genes. The newly constructed plasmids in this study are deposited in Zenodo repository under the DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.15221498.

In the K. marxianus wild-type strain FIM1, we used CRISPR/Cas9 technology to construct the inversion strain AY-45, which contains only the loxP sites 1 and 15 on Chr VIII, and the rearranged strain AY-23, which contains loxP site 7 on Chr V and loxP site 11 on Chr III. We then introduced the Cre recombinase plasmid LHP893 to induce rearrangements between the sites, resulting in an inversion within Chr VIII (designated as strain Inv-45) and a translocation between Chr III and Chr V (designated as strain Tra-23).

The C-terminus of leghemoglobin LBA was fused with the coding gene for eGFP and assembled into the pUKDN115 vector14, resulting in the LBA-eGFP fusion expression plasmid. The LBA gene was assembled into the pUKDN115 vector to obtain the recombinant expression plasmid pUKDN115 -LBA. The coding genes for the glucosidase Badgla, the melibiose esterase Mel1, and the feruloyl esterase AnFaeA were amplified and assembled into the pUKDN112 vector42, resulting in a series of recombinant protein expression plasmids. The amino acid sequences of the recombinant proteins are presented in Supplementary Table 5.

High-throughput screening of fluorescence

The K. marxianus strain LHP1044 was utilized as the starting strain19, with two loxP sites on each chromosome (see Supplementary Table 1), positioned downstream of two genes oriented in opposite directions. Using the fusion protein LBA-eGFP as a reporter, two iterative screening strategies based on the action of Cre recombinase were employed to ultimately obtain evolved strains producing high levels of recombinant protein (Fig. 1). Strategy 1 utilizes Cre recombinase without applying H2O2, while Strategy 2 employs Cre recombinase along with 10 mM H2O2 as the secondary selection pressure, which is the critical concentration of H2O2 that the Cre recombinase-expressing strains can withstand (Supplementary Fig. 1). Each round of screening process is depicted in Fig. 1. The starting strains first undergo Cre recombinase treatment, then they are in cultivated either without H2O2 (Strategy 1) or with H2O2 (Strategy 2). Subsequently, the Cre plasmid is removed, and the strains are incubated on petri dishes, followed by three steps of screening to finally isolate 1–5 monoclonal clones with the highest fluorescence intensity. Specifically, in the primary screening, petri dishes are exposed to irradiation from our laboratory-made excitation light source (wavelength 488 nm) to identify clones exhibiting high fluorescence intensity. From each petri dish, which typically contains around 100 clones, the top 1–5 clones are selected and transferred to a 96-deep-well plate for subsequent cultivation. Each round involves picking ~1000 clones from 600 petri dishes. In the secondary screening, after 72 h of growth in the 96-deep-well plate, fluorescence intensity is measured using a multifunctional microplate reader. Clones showing at least a 50% increase in fluorescence intensity compared to strain LHP1044 are chosen for further cultivation in shake flask. In the tertiary screening, clones cultivated in shaking flasks for 72 h are further measured by the multifunctional microplate reader. If there is an increase in the fluorescence intensity, the top 1–5 clones displaying the highest fluorescence intensity are selected, preserved, and then mixed together as the starting strains for the next screening round. If there is no increase in fluorescence intensity, the iterative screening process is terminated.

Recombinant protein assays and quantitation

Following transforming the recombinant protein expression plasmids into yeast cells, they were inoculated into 50 mL of YG medium (2% yeast extract, 4% glucose) and incubated at 30 °C with shaking at 220 rpm for 72 h. For secreted recombinant proteins, the activities of Mel1, AnFaeA, and Badgla in the supernatant were measured using previously described methods14,43. For intracellular recombinant proteins, 1 mL of the fermentation broth was centrifuged to collect the yeast cells, which were then disrupted using previously described methods25. The lysate was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4 °C for 30 min, and the supernatant was used for SDS-PAGE analysis. The intensity of the bands corresponding to the recombinant proteins on the SDS-PAGE gel was analyzed using the GenoSens analysis software. Bovine serum albumin was used as a standard to establish a standard curve, and the expression levels of the recombinant proteins were calculated based on this standard curve.

Determination of critical concentration for H2O2 screening

The determination of the critical concentration was initially conducted through qualitative experiments. Monoclonal cultures were mixed and inoculated into YD liquid medium containing 0, 8, 10, and 12 mM H2O2, with an initial OD600 of 0.3. The cultures were then incubated in a shaking incubator at 30 °C for 12 h until reaching the early logarithmic growth phase, at which point the OD600 was measured. A gradient dilution was performed, starting with an initial OD600 of 0.6 for the spot test. Cell growth during the spot test was monitored over an 18 h period.

Subsequently, the determination of the critical concentration was carried out through quantitative experiments. Monoclonal cultures were mixed and inoculated into YD liquid medium containing 0, 8, 10, and 12 mM H2O2, with an initial OD600 of 0.3. The cultures were then incubated in a shaking incubator at 30 °C for 12 h until reaching the early logarithmic growth phase, at which point the OD600 was measured. Following several ten-fold gradient dilutions, a final OD600 of 10−4 was performed for plating. The plates were then incubated in a 30 °C incubator for 48 h to count the number of colonies. The survival rate was calculated by dividing the colony number by the average number of colonies from the control experiment (0 mM H2O2).

H2O2 tolerance spot assays

Cell cultures were diluted five times with a 5-fold dilution factor from an initial OD600 of 0.6. They were then incubated for 18 h at 30 °C, which were in the H2O2 concentration of 0.04%, 0.06%, 0.08%, respectively.

Growth curves of cells

Cells were cultivated at 30 °C. Cells were grown in YPD medium (2% peptone, 1% yeast extract, and 2% agar). The culture was diluted into 50 mL YG medium at an OD600 of 0.2 and grown for 72 h at 30 °C. OD600 of the culture was measured after 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 h. The experiment was performed with three parallel cultures.

Identification of chromosomal rearrangement

The identification of rearrangement was based on the methods described in our previous study19. Specifically, we designed 16 pairs of primers (Supplementary Table 4) targeting the 16 loxP sites (Supplementary Table 1), with each pair located ~500 bp upstream and downstream of the respective loxP site. Genomic DNA was extracted from the strains for PCR analysis using the genomic DNA as a template. Amplification was performed using the primer pairs; failure to obtain the expected product indicated that a rearrangement had occurred at that locus. For clones with rearrangements occurring at multiple loci (at least two sites), it was inferred that rearrangements happened between those sites, and specific primers were designed for further verification.

Genetic stability of the rearranged strains

The strains were inoculated into 50 mL of YPD medium and cultured overnight at 30 °C with shaking at 220 rpm. Then, they were transferred to a new 50 mL YPD medium with an initial OD600 of 0.1 and cultured for 24 h (~ten generations). The OD600 was measured to assess the growth of the strains, and the process was repeated by transferring to a new 50 mL YPD medium with an initial OD600 of 0.1. Genomic DNA was extracted from the cultures at generation 0, 50, and 100 to use as templates for PCR analysis to identify rearrangements and translocations. For the samples cultured to generation 100, appropriate dilutions were plated on YPD agar plates. After two days of incubation, individual colonies were picked for colony PCR analysis to verify rearrangements and translocations.

RNA-seq analysis

The strains were inoculated into 50 mL of YPD medium and cultured overnight at 30 °C with shaking at 220 rpm. They were then transferred to a new 50 mL YPD medium with an initial OD600 of 0.1 and cultured at 30 °C with shaking at 220 rpm until reaching the logarithmic phase (OD600 = 0.6). An appropriate amount of cells was collected, washed twice with sterile water, and stored at −80 °C. The samples for analysis were sent to Lingren Biotechnology Company for total RNA extraction, quality assessment, cDNA library preparation, and sequencing. The library was constructed using the Illumina Truseq™ RNA sample prep kit, followed by sequencing. The quality-controlled sequencing reads were aligned to the reference genome of K. marxianus FIM1 (assembly accession GCA_001854445.2). DEGs between the two groups of samples were analyzed using the edgeR package (v3.8) in R. Each group of RNA sequencing samples included three biological replicates.

Quantification of cAMP by HPLC

The monoclonal clones were inoculated into 50 mL of YPD medium and cultured overnight at 30 °C with shaking at 220 rpm. Subsequently, they were transferred to a new 50 mL YPD medium, initially containing an OD600 of 0.2. Cultivation was conducted at 30 °C with shaking at 220 rpm until the logarithmic phase was attained (OD600 = 0.6). The concentrations of cAMP were measured using HPLC as described by Ren15.

ATP and acetyl-CoA analysis

Cells for test were collected at the logarithmic phase (OD600 = 0.6), cultured in YPD medium, at 30 °C. The samples were submitted to Shanghai Medical College, Fudan University for ATP and Acetyl-CoA quantitative analysis (SCIEX7500-MS).

Statistics and reproducibility

All experiments in this study were conducted with a minimum of three biological replicates (except the genomic PCR analysis). Student’s t test was used for inter-group sample significance analysis, with a p value less than 0.05 indicating significant differences between the two groups. Cohen’s d value was utilized as the statistical metric for measuring effect size. In the results, ‘‘*’’ represents p < 0.05, ‘‘**’’ represents p < 0.01, ‘‘***’’ represents p < 0.001, and ‘‘****’’ represents p < 0.0001. The n biological replicates are defined as follows: after strain activation, n single clones were selected and inoculated into n independent tubes or shake flasks for separate experiments, where n represents the number of biological replicates. Error bars in each figure are calculated as the standard deviation.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The original RNA-seq datasets presented in this study can be found in online NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) repositories as follows: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1132577. The numerical source data behind the graphs can be found in Supplementary Data 3. All untrimmed and unedited blot/gel images are provided as Supplementary Figs. in Supplementary Information file. All other data are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Code availability

The differential expression of genes between two sample groups was analyzed using edgeR (https://www.bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/edgeR.html). The GO enrichment analysis for DEGs in K. marxianus was based on the homology to S. cerevisiae and was performed using perl. The code is provided in the file named ‘GO enrichment analysis for K marxianus.zip’ and has been deposited in Zenodo repository under the https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15194603.

References

Kot, P. et al. Mechanism of chromosome rearrangement arising from single-strand breaks. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 572, 191–196 (2021).

Tang, X. X. et al. Origin, regulation, and fitness effect of chromosomal rearrangements in the yeast. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 786 (2021).

Rieseberg, L. H. Chromosomal rearrangements and speciation. Trends Ecol. Evol.16, 351–358 (2001).

Navarro, A. & Barton, N. H. Chromosomal speciation and molecular divergence—accelerated evolution in rearranged chromosomes. Science 300, 321–324 (2003).

Sinclair-Waters, M. et al. Ancient chromosomal rearrangement associated with local adaptation of a postglacially colonized population of Atlantic cod in the northwest Atlantic. Mol. Ecol. 27, 339–351 (2018).

Stewart, N. B. & Rogers, R. L. Chromosomal rearrangements as a source of new gene formation in Drosophila yakuba. PLOS Genet. 15, e1008314 (2019).

Weckselblatt, B. & Rude, M. K. Human structural variation: mechanisms of chromosome rearrangements. Trends Genet. 31, 587–599 (2015).

Mitelman, F., Johansson, B. & Mertens, F. The impact of translocations and gene fusions on cancer causation. Nat. Rev. Cancer 7, 233–245 (2007).

Chang, S. L., Lai, H. Y., Tung, S. Y. & Leu, J. Y. Dynamic large-scale chromosomal rearrangements fuel rapid adaptation in yeast populations. Plos Genet. 9, e1003232 (2013).

Zimmer, A. et al. QTL dissection of lag phase in wine fermentation reveals a new translocation responsible for saccharomyces cerevisiae adaptation to sulfite. Plos One 9, e86298 (2014).

Naseeb, S. et al. Widespread impact of chromosomal inversions on gene expression uncovers robustness via phenotypic buffering. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1679–1696 (2016).

García-Ríos, E., Nuévalos, M., Barrio, E., Puig, S. & Guillamón, J. M. A new chromosomal rearrangement improves the adaptation of wine yeasts to sulfite. Environ. Microbiol. 21, 1771–1781 (2019).

Mattanovich, D. et al. in Recombinant Gene Expression: Reviews and Protocols, Third Edition Vol. 824 Methods in Molecular Biol. (ed A. Lorence) 329–358 (2012).

Liu, Y. et al. Mutational Mtc6p attenuates autophagy and improves secretory expression of heterologous proteins in Kluyveromyces marxianus. Microb. Cell Fact 17, 1186 (2018).

Ren, H. et al. Coupling thermotolerance and high production of recombinant protein by CYR1N1546K mutation via cAMP signaling cascades. Commun. Biol. 7, 1038 (2024).

Tyo, K. E. J., Liu, Z., Petranovic, D. & Nielsen, J. Imbalance of heterologous protein folding and disulfide bond formation rates yields runaway oxidative stress. BMC Biol. 10, 16 (2012).

Marciniak, S. J., Chambers, J. E. & Ron, D. Pharmacological targeting of endoplasmic reticulum stress in disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 21, 115–140 (2022).

Li, Q., Harvey, L. M. & McNeil, B. Oxidative stress in industrial fungi. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 29, 199–213 (2009).

Ren, H. et al. Establishment of a Cre-loxP system based on a leaky LAC4 promoter and an unstable panars element in Kluyveromyces marxianus. Microorganisms 10, 1240 (2022).

Blount, B. A. et al. Rapid host strain improvement by in vivo rearrangement of a synthetic yeast chromosome. Nat. Commun. 9, 1932 (2018).

Cheng, L. et al. Large-scale genomic rearrangements boost SCRaMbLE in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat. Commun. 15, 770 (2024).

Jin, J., Jia, B. & Yuan, Y.-J. Yeast chromosomal engineering to improve industrially-relevant phenotypes. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 66, 165–170 (2020).

Yu, Y. et al. Comparative genomic and transcriptomic analysis reveals specific features of gene regulation in Kluyveromyces marxianus. Front. Microbiol. 12, 598060 (2021).

Mo, W. et al. Kluyveromyces marxianus developing ethanol tolerance during adaptive evolution with significant improvements of multiple pathways. Biotechnol. Biofuels 12, 63 (2019).

Yang, D. et al. Investigation of Kluyveromyces marxianus as a novel host for large-scale production of porcine parvovirus virus-like particles. Micro. Cell Fact. 20, 24 (2021).

Orr, J. A., Luijckx, P., Arnoldi, J. F., Jackson, A. L. & Piggott, J. J. Rapid evolution generates synergism between multiple stressors: linking theory and an evolution experiment. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 1740–1752 (2022).

Lopez-Maury, L., Marguerat, S. & Baehler, J. Tuning gene expression to changing environments: from rapid responses to evolutionary adaptation. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 583–593 (2008).

Levine, J. H., Lin, Y. & Elowitz, M. B. Functional roles of pulsing in genetic circuits. Science 342, 1193–1200 (2013).

Vogelstein, B. et al. Cancer genome landscapes. Science 339, 1546–1558 (2013).

Brückner, D. B., Chen, H., Barinov, L., Zoller, B. & Gregor, T. Stochastic motion and transcriptional dynamics of pairs of distal DNA loci on a compacted chromosome. Science 380, 1357–1362 (2023).

Sanyal, A., Bau, D., Marti-Renom, M. A. & Dekker, J. Chromatin globules: a common motif of higher order chromosome structure? Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23, 325–331 (2011).

Song, T. et al. Integrative identification by Hi-C revealed distinct advanced structural variations in lung adenocarcinoma tissue. Phenomics 3, 390–407 (2023).

Versele, M., de Winde, J. H. & Thevelein, J. M. A novel regulator of G protein signalling in yeast, Rgs2, downregulates glucose-activation of the cAMP pathway through direct inhibition of Gpa2. EMBO J. 18, 5577–5591 (1999).

Thevelein, J. M. & de Winde, J. H. Novel sensing mechanisms and targets for the cAMP-protein kinase A pathway in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Microbiol. 33, 904–918 (1999).

Bouchez, C. & Devin, A. Mitochondrial Biogenesis and Mitochondrial Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS): a complex relationship regulated by the cAMP/PKA signaling pathway. Cells 8, 287 (2019).

Yun, C. W., Tamaki, H., Nakayama, R., Yamamoto, K. & Kumagai, H. Gpr1p, a putative G-protein coupled receptor, regulates glucose-dependent cellular cAMP level in yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 252, 29–33 (1998).

Xue, Y., Batlle, M. & Hirsch, J. P. GPR1 encodes a putative G protein-coupled receptor that associates with the Gpa2p Gα subunit and functions in a Ras-independent pathway. EMBO J. 17, 1996–2007 (1998).

Hiltunen, T. et al. Dual-stressor selection alters eco-evolutionary dynamics in experimental communities. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 1974–1981 (2018).

Lajus, D. L. & Alekseev, V. R. Phenotypic variation and developmental instability of life-history traits:a theory and a case study on within-population variation of resting eggs formation in Daphnia. J. Limnol. 63, 37–44 (2004).

Peltier, E. et al. Dissection of the molecular bases of genotype x environment interactions: a study of phenotypic plasticity of Saccharomyces cerevisiae in grape juices. BMC Genom.19, 772 (2018).

Borges, C. R. & Lake, D. F. Oxidative protein folding: nature’s knotty challenge. Antioxid. Redox Sign 21, 392–395 (2014).

Shi, T. et al. Characterization and modulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress response target genes in Kluyveromyces marxianus to improve secretory expressions of heterologous proteins. Biotechnol. Biofuels 14, 236 (2021).

Wu, P. et al. Transfer of disulfide bond formation modules via yeast artificial chromosomes promotes the expression of heterologous proteins in Kluyveromyces marxianus. Mlife 3, 129–142 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the colleagues in Engineering Research Center of Industrial Microorganisms in Fudan University for their generous assistance, and thank the Arawana Scholarship provided by Yihai Kerry Arawana Holdings Co., Ltd. This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2021YFA 0910601), Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (2021-03-52), and the Science and Technology Research Program of Shanghai (Nos. 23HC1400600 and 2023ZX01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.L. and W.M. supervised the study. W.M. and H.R. designed the experiments. H.R. and Q.Z. performed the experiments. W.M., H.L. and K.S. analyzed the data. W.M., H.L., H.R., Q.Z., Y.Y., and J.Z interpreted the results. W.M. and H.R. wrote the manuscript. H.L. organized this research project. All authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks J.D. and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: E.P. and M.X. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ren, H., Zou, Q., Song, K. et al. Enhancing recombinant protein production through Cre-loxP mediated chromosomal rearrangement evolution in Kluyveromyces marxianus. Commun Biol 8, 672 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08110-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08110-y