Abstract

Density-based clustering is used in many contexts including in single molecule localization microscopy (SMLM), where it is commonly used to elucidate the nanoscale organization of molecules. However, little guidance is available for evaluating clustering performance, which is often dependent on user-input parameters. Here, we develop an efficient implementation of density-based cluster validation (DBCV) that can quantitatively evaluate clustering in SMLM-sized datasets. We demonstrate that maximizing DBCV scores accurately identifies clusters in noisy, simulated data. Coupling DBCV with Bayesian optimization, we outline a method, DBOpt, that selects input parameters in an unbiased manner for density-based clustering algorithms. We demonstrate that optimal parameters can be selected for popular algorithms (DBSCAN, HDBSCAN, OPTICS) with minimal user input. Finally, we show that DBOpt reports accurate feature sizes in 2D and 3D experimental data. In sum, DBOpt will improve the integrity, reproducibility, and quality of cluster analyses for SMLM and beyond.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Single-molecule localization microscopy (SMLM) describes a class of super-resolution techniques commonly employed to overcome the diffraction limit associated with traditional microscopy1. Many forms of SMLM exist, including stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM)2, photoactivatable localization microscopy (PALM)3, and point accumulation in nanoscale topography (PAINT)4. Regardless of the chosen technique, SMLM data consists of point coordinates with associated uncertainties that correspond to fluorophore positions. While great advances have been made to develop new and refine established SMLM techniques, efficient and accurate analysis of the resulting data still presents major challenges5. In coordinate-based SMLM data, clustering analyses are commonly performed to reveal insights into the complex underlying structure and spatial coordination of biological molecules5,6. Among clustering methods, density-based clustering is a common choice for SMLM data, as it avoids biasing towards convex shapes like other clustering methods such as k-means, Gaussian mixture models, and various hierarchical clustering algorithms7,8,9,10. Instead, density-based methods allow arbitrary cluster shapes by identifying clusters as high-density connected regions separated by regions of low density6,7,11,12,13.

A popular density-based clustering method is density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (DBSCAN)14. DBSCAN connects points into clusters based on a reachability distance. DBSCAN is commonly employed for SMLM data and has been shown to perform well when ground truth information is available6,15. A recent modification of DBSCAN, hierarchical DBSCAN (HDBSCAN), aims to improve DBSCAN by allowing clusters to vary in density through selection from a hierarchical tree constructed from mutual reachability distances16,17. HDBSCAN is relatively understudied compared to DBSCAN, likely due to its more recent development. A third algorithm, ordering points to identify the clustering structure (OPTICS), allows variable density clusters to be identified through the ordered reachability of points18. For each of these algorithms, at least two input parameters are required to identify clusters.

In nearly all clustering algorithms, challenges in choosing input parameters exist, and parameter choice is not intuitive even when domain knowledge is available12. Thus, cluster validation should be implemented to guide parameter selection and increase reproducibility. Many choices for cluster validation exist, falling primarily into two classes, external and internal. External validation requires ground truth knowledge, allowing comparisons to be made between clustering algorithm outputs and the ground truth assignment of points into clusters19. While effective, external validation is impractical in almost all real-world scenarios, where ground truth information is rarely available. Despite this, there are practical uses of external validation for experimental SMLM data. For example, Nieves et al. proposed a framework in which experimental data is compared to a set of simulated datasets to determine which simulation most closely matches the experimental data. A clustering algorithm and corresponding parameters are then chosen for experimental data that perform best on the nearest matching simulated data15. To our knowledge, Nieves et al. provide the most comprehensive guidance for choosing clustering parameters for SMLM. However, critical limitations exist with this approach. The method is limited to the simulated datasets analyzed, restricting users to predefined structures and making the approach impractical for varied and/or complex clusters. Moreover, given that there can be no standard set of simulations for all possible clustering scenarios, outcomes could vary across research groups.

Alternatively, internal validation methods do not rely on ground truth information, instead scoring the clustering performance based on intrinsic properties of the data19. Many internal validation algorithms exist, such as the commonly used silhouette score or Davies-Bouldin index20, though most are unsuitable for validating non-globular clusters. Density-based cluster validation (DBCV) is one of the few validation methods tailored to density-based algorithms21, although it remains underutilized. In brief, DBCV evaluates clustered data by comparing the intra-cluster spread of points to the inter-cluster separation locally. Intuitively, clusters are scored higher as the spread of points within a cluster decreases and the separation between clusters increases. Unlike other density-based validation methods, such as the composed density between and within clusters (CDbw) index22, DBCV does not require input parameters, improving its strength as an unbiased evaluator21.

Here, we propose a clustering optimization method that utilizes the internal validation metric DBCV to identify optimal clustering input parameters. This method optimizes clustering by iteratively assessing the performance of different parameter combinations and selecting the combination with the highest validation scores. To our knowledge, the fastest publicly available implementations of DBCV remain far too slow for validating SMLM-sized datasets, especially when considering many distinct parameter combinations23,24,25. Furthermore, naively sweeping parameters to find optimal clustering is not scalable to large parameter spaces. Therefore, this approach requires both a performance-efficient implementation of DBCV and a method to efficiently sweep large parameter spaces where there is little knowledge of appropriate parameter bounds. Herein, we (1) provide an efficient implementation of DBCV that is appropriate for SMLM data, (2) couple this improved DBCV implementation with Bayesian optimization to efficiently sweep the parameter space of density-based clustering algorithms to find DBCV maxima (DBOpt), and (3) demonstrate the efficacy of DBOpt by evaluating its performance on simulated and experimental datasets.

Results

DBCV Implementation

DBCV calculates individual cluster scores (Ci score) based on the intra-cluster sparseness and inter-cluster separation of each cluster (Ci), as shown in Eq. 121. An aggregate DBCV score summed over all clusters (l) is computed from the individual cluster scores as a weighted average based on the number of points in each cluster (NCi) and the total number of points in the dataset, including noise (Ntotal) (Eq. 2, see Methods: Eqs. 3, 4 for more details)21.

DBCV for SMLM must be scalable to large datasets. To our knowledge, the fastest implementations currently available are too slow for practical use on SMLM-sized data23,24,25. To improve upon this, we quantified cluster separation leveraging a k-dimensional tree to find nearest neighbor distances of core points. A k-dimensional tree is constructed with an approximate time complexity \(O\left(\right.{N}_{{\mathrm{core}}}(\log ({N}_{{\mathrm{core}}}))\) where Ncore are all clustered, core points as defined by DBCV26. Once constructed, the separation value of each cluster can be calculated by querying the tree with approximate time complexity \(O\left(\right.{N}_{{C}_{i}{\mathrm{core}}}(\log ({N}_{{C}_{i}{\mathrm{core}}}+1))\)26. With many other steps in the algorithm, the overall theoretical time complexity of the improved implementation (k-DBCV) is difficult to calculate. Thus, we benchmarked the performance of k-DBCV on simulated datasets and show up to orders of magnitude increases in speed relative to previous implementations while maintaining efficient memory usage (Fig. S1).

Density-based clustering parameter selection with Bayesian optimization (DBOpt)

With an improved implementation of DBCV in hand, we now optimize clustering by selecting parameters that result in the highest DBCV score. DBOpt combines k-DBCV computation with Bayesian optimization to maximize the DBCV score of a clustering algorithm within a user-defined parameter space. Bayesian optimization provides an efficient method to maximize the output of a function without requiring exploration of every possible parameter combination, making it suitable for cases where there is little to no knowledge of optimal parameters and/or sensitivity to parameters27. In brief, the optimization relies on a Gaussian prior function with an upper confidence bound acquisition function that balances maximization and exploration during optimization to iteratively select points for evaluation. Multiple iterations are performed to efficiently find the maxima27,28.

The proposed cluster analysis pipeline is shown in Fig. 1. Before the optimization process, hyperparameters must be selected for DBOpt. This includes the lower and upper bounds of the parameters unique to the clustering algorithm employed and the number of iterations to be performed. The clustering algorithm parameters, the recommended parameter bounds, and the number of Bayesian optimization iterations to perform are described in Supporting Text 1 and Fig. S2.

The Bayesian optimization step produces a series of parameter combinations with corresponding DBCV scores between −1 and 1, with −1 automatically assigned when there are fewer than two clusters identified. In addition to the global DBCV score (Eq. 2), the resulting clusters have individual cluster scores (Eq. 1), allowing for comparisons across datasets as well as outlier detection within datasets, respectively. The output commonly contains several parameter combinations that produce equal maximum global DBCV scores (to within two significant figures). DBOpt selects between these by choosing parameters for which the median individual cluster score is highest.

Additional DBOpt runs should be performed in cases where the initial hyperparameters for parameter bounds may be too small or too large to effectively optimize the parameters. Evidence of insufficient size would be maximum DBCV scores at the edge of the parameter space. Evidence of an optimization space that is too large would be a small number of parameters evaluated near the DBOpt selected parameters or a small number of scores near the maximum DBCV score. Confirmation of proper optimization can be achieved by performing DBOpt multiple times on the same dataset from a random set of initial parameters and ensuring the maximum score converges to approximately the same value. Following DBOpt, cluster analysis can be performed, and the selected clustering parameters, along with the cluster validation scores, should be reported.

Validation of DBOpt with simulated data

To assess DBCV as a validation metric and test the ability of DBOpt to identify optimal parameters, we evaluated simulated datasets with the three density-based algorithms, DBSCAN, HDBSCAN, and OPTICS. We simulated SMLM data across five categories of clusters, with representative datasets shown in Fig. 2. For each category of clusters, 25 unique datasets were simulated on a ≈3 × 3 μm 2D plane as described in Methods. The simulations varied in cluster size, shape, density, number of clusters, and noise density (Supporting Text 2, Table S1a–e).

a Circular (C02), b elliptic (E14), c micellular (M22), d fibrillar (F18), and e mixed (V12) cluster scenarios. Alphanumeric code in parentheses corresponds to simulations described in Table S1. Simulated clusters are shown in color, noise is shown in gray. a, d, e have gradient noise. b, c have homogeneous noise.

To evaluate the performance of each algorithm against ground truth, we use the external validation score V-measure (see Methods)29. We choose V-measure rather than other external validation scores such as adjusted Rand index, Fowlkes–Mallows index, or adjusted mutual information29,30,31,32, as V-measure handles diverse scenarios, as detailed in ref. 29. Here, we systematically explored parameter combinations with the three density-based algorithms considered and assessed the V-measure score of the resulting clusters against the ground truth assignments. We refer to this method as a naive external validation sweep (EVS). We then select the parameters that result in the maximum V-measure score for comparisons between clustering algorithms and against DBOpt performance. For all simulations, naive EVS was performed with DBSCAN, HDBSCAN, and OPTICS as described in Methods. Separately, DBOpt (which does not use ground truth information) was performed to assess its ability to match EVS performance.

Representative results corresponding to simulations shown in Fig. 2 from EVS and DBOpt on challenging simulations (>50% noise) are shown in Fig. 3. The contour plots depicting V-measure scores for EVS and DBCV scores for DBOpt show qualitatively similar character. To quantify this, we calculated the Pearson R correlation coefficient between V-measure and DBCV scores for every simulation across the parameter space assessed as described in Supporting Text 3. This shows a generally high correlation between V-measure and DBCV scores, with DBSCAN yielding the highest overall correlation (Fig. S3). Furthermore, the contour plots show that the DBCV and V-measure scores are at or near their maxima over a range of parameter combinations for a given simulation. Thus, multiple runs of DBOpt may produce different parameters for the same dataset without significantly affecting the clustering result.

Elliptic (E14), micellular (M22), and mixed (V12) parameter sweeps of cluster scenarios are also shown in Fig. 2 for DBSCAN, HDBSCAN, and OPTICS, with optimal EVS and DBOpt cluster outcomes plotted in the right panel. Parenthetical notations indicate the simulated data as described in Table S1. Points on the contour plots represent each parameter combination that is scored from which the contour plot is prepared (discrete sampling for naive EVS, Bayesian sampling for DBOpt); the white “X” represents the optimal chosen parameters from EVS and DBOpt. Right panel plots show clusters identified from the highest scoring set of parameters from the highest scoring algorithm and correspond to those marked with * in Fig. S4.

We plotted representative simulated clusters (Fig. 2) and the clusters resulting from the highest scoring parameters for each clustering algorithm based on naive EVS V-measure scores and, separately, based on DBOpt DBCV scores in Fig. S4. Between all algorithms, we show the highest scoring cluster results in Fig. 3, right panel. Naive EVS identifies clusters that qualitatively match ground truth information for DBSCAN, while HDBSCAN and OPTICS deviate from ground truth for more complex clustering scenarios, indicating a weaker performance by these algorithms (Fig. S4).

When the best-performing parameters identified by EVS led to good clustering results and a high V-measure score, the best-performing parameters identified by DBOpt also performed well and qualitatively matched naive EVS performance (Fig. S4). To assess the quantitative performance of DBOpt on every simulated dataset, we calculated the V-measure scores of the parameters chosen by DBOpt and plotted them vs. the maximum V-measure scores achieved by naive EVS for each algorithm (Fig. 4a–c). We calculated the mean squared error (MSE) of the residuals and show them on each corresponding plot. Here, DBOpt paired with DBSCAN most closely matches scores achieved with naive EVS, with weaker performance for some fibrillar and mixed clustering scenarios. Also shown is the combined performance, where the selected parameters correspond to the maximum DBOpt DBCV score between all clustering algorithms (Fig. 4d).

Comparisons of V-measure scores for parameters chosen with naive EVS and V-measure scores for parameters chosen with DBOpt for a DBSCAN, b HDBSCAN, c OPTICS, and d all algorithms combined. MSE relative to the dashed line is shown on each plot. e Distributions of the ratio of DBOpt V-measure scores to maximum naive EVS V-measure scores (dotted line represents median and “X” represents mean; n = 125 simulations). f Maximum V-measure and g maximum DBCV score comparisons between algorithms for each cluster simulation type (n = 25 simulations). Box indicates 25th and 75th percentile, whiskers indicate 5th and 95th percentile, interior line indicates the median, and outliers are shown as points. h Percentage of the simulations for which each algorithm had the highest V-measure and DBCV scores, respectively (n = 25 simulations for each cluster type). The legend in f applies to (f–h). Statistical analysis of (e–g) is discussed in Supporting Text 4, Table S2a–c.

The overall performance of DBOpt relative to naive EVS is shown by taking the ratio of the DBOpt to EVS V-measure scores from Fig. 4a–d, and distributions of these ratios for all 125 simulations performed are shown in Fig. 4e. The median normalized V-measure score was 0.97, 0.98, 0.97, and 0.97 for DBSCAN, HDBSCAN, OPTICS, and all algorithms combined, respectively, indicating that in most cases DBOpt as effectively identified clusters as if ground truth assignments were known. We further compared V-measure and, separately, DBCV scores associated with optimal parameters between algorithms for every simulated SMLM dataset (Fig. 4f–h). Statistical analysis of Fig. 4e–g is discussed in Supporting Text 4, Table S2a–c. These comparisons indicate that DBSCAN generally scores significantly higher than HDBSCAN and OPTICS for each cluster type. In cases where noise was low, HDBSCAN occasionally returned a slightly higher V-measure score, and in rare circumstances, OPTICS returned the highest DBCV score. Finally, we compared the runtime of each algorithm with DBOpt. Here, DBOpt paired with DBSCAN and HDBSCAN had similar runtimes, while OPTICS was slower for every simulation (Fig. S5).

We note that, as can be appreciated from Fig. 4g, DBCV scores are relatively low compared to the theoretical maximum of 1 as well as to the maximum V-measure scores. This is primarily because DBCV values are reduced by the presence of noise, as in Eq. 2Ntotal includes points assigned to noise. With simulated datasets, we can ensure that clusters are properly identified even when DBCV scores are low because ground truth information is available. However, for experimental data, a threshold may exist where scores are too low to distinguish accurate clustering from the clustering of noise. To determine this threshold, we evaluated DBOpt on simulated 2D noise and showed that the threshold decreases as the lower bound of the MinPts parameter increases (Supporting Text 5, Fig. S6).

To broaden the simulations to capture more experimental scenarios, we also evaluated DBOpt performance on multi-emitter data. Here, each originally simulated point may have multiple corresponding points drawn from the same uncertainty distribution, resulting in more localizations for both clustered and noise points (Supporting Text 6, Fig. S7). DBOpt remains robust in most multi-emitter scenarios for DBSCAN and HDBSCAN. Furthermore, when accounting for fluorophore-to-antibody ratios when setting the MinPts hyperparameter, DBOpt fully recovers and in some cases improves its performance in the presence of multi-emitters (Fig. S7c). Regardless of parameter bounds, OPTICS performance is diminished by the presence of multi-emitters, limiting its practicality for evaluating SMLM data.

Extension of traditional SMLM to 3D imaging has revealed complex cellular structures in unprecedented detail33,34. To test whether DBOpt performs well on 3D data, ten unique datasets containing 3D ellipsoidal clusters and ten unique datasets containing 3D fibrillar clusters were simulated (Table S1f) as described in Methods. Naive EVS and DBOpt were performed separately for each algorithm. A representative simulation is shown in Fig. 5a, with the clustered data resulting from DBOpt shown in Fig. 5b. Comparisons between DBOpt and external validation of each algorithm are shown in Fig. 5c–f. The median normalized V-measure scores for DBSCAN, HDBSCAN, and OPTICS are 0.98, 0.99, and 0.99, respectively. Comparing across algorithms reveals that DBSCAN scores significantly higher than HDBSCAN and OPTICS with both naive EVS and DBOpt (Supporting Text 4, Table S2d). Simulated noise was evaluated to assess the presence of a threshold in 3D under which cluster identification cannot be distinguished from clustering noise (Fig. S8). Overall, the noise threshold was reduced by the increase in MinPts, as also seen in 2D simulations (Fig. S6).

a Representative simulation (S01, Table S1f) of 3D clusters, b optimal clustering of the representative simulated data via DBOpt, c comparisons of V-measure scores between naive EVS and V-measure scores for parameters chosen with DBOpt for both ellipsoid and fibrillar clusters, d distributions of the ratio of DBOpt V-measure scores to maximum naive EVS V-measure scores (dotted line represents median and “X” represents mean; n = 20 simulations), and e maximum V-measure and f maximum DBCV scores for each algorithm found via naive EVS and DBOpt, respectively (n = 20 simulations). Box indicates 25th and 75th percentile, whiskers indicate 5th and 95th percentile, and the interior line indicates median. Statistical analysis of d–f is discussed in Supporting Text 4, Table S2d.

Experimental SMLM analysis

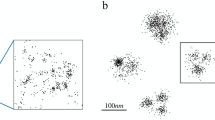

To demonstrate a practical use case for DBOpt, we quantified the size and shape of β1 integrin nanoclusters in the ligand-bound conformation within focal adhesions. MBA-MB-231 cells were fixed, and regions of interest (ROI) were identified by the presence of vinculin, an adapter protein localized to focal adhesions35. β1 integrin was labeled with an antibody specific to the ligand-bound conformation36. A widefield image of cells labeled for vinculin and β1 integrin was acquired, followed by 2D dSTORM imaging of β1 integrin. A representative reconstructed image is shown in Fig. 6a, b. To identify clusters, DBOpt coupled with DBSCAN was performed on each acquired dataset (Fig. 6c). The optimal parameters identified with corresponding DBCV scores are shown in Table S3. A representation of resulting clusters, colored to depict individual cluster scores, is shown in Fig. 6d, with the corresponding full cell integrin clustering result shown in Fig. S9. For analysis, clustered integrin localizations within the ROI co-localized with vinculin were selected. Identified clusters with positive individual cluster scores were analyzed (Fig. 6e). Cluster shape (aspect ratio) and size were determined (Fig. 6f) as described in Methods. This analysis reveals a short-axis median FWHM of 53 nm and a median aspect ratio of 1.51, results that are in close agreement with previously reported integrin cluster sizes37,38.

a dSTORM image (Integrin 02, Table S3) of a cell co-labeled for vinculin (red) and active β1 integrin (cyan). (scale bar: 10 μm) b Selected ROI (white box in (a); scale bar: 2 μm). c DBOpt parameter sweep of Integrin 02 localizations with DBSCAN. d Selected region (corresponding to (b)) of identified integrin clusters from DBOpt; color depicts individual cluster score. e Distribution of individual integrin cluster scores from vinculin ROIs; clusters scoring ≥ 0 were analyzed for size (n = 3462 clusters not excluded, pooled from five samples). f Width, length, and aspect ratio (AR) of all integrin clusters from vinculin ROIs (n = 3462 clusters, pooled from five samples). Box plot lines indicate median, “X” indicates mean, boxes represent 25th and 75th percentiles, and whiskers represent 5th and 95th percentiles. g dSTORM image (Clathrin 01, Table S3) of a cell labeled for clathrin (red) (scale bar: 10 μm). h Selected ROI (white box in (g); scale bar: 2 μm)) with inset showing a 100 nm axial region of a clathrin structure projected in 2D (scale bar: 0.2 μm). i DBOpt parameter sweep of Clathrin 01 localizations with DBSCAN. j Selected region of identified clathrin clusters from DBOpt; color depicts individual cluster score. k Distribution of individual cluster scores from full cell results; clusters scoring < 0 were excluded (n = 2045 clusters not excluded, pooled from five samples). l FWHMs of clathrin clusters from full cell results (n = 2045 clusters not excluded, pooled from five samples); inset depicts results with individual cluster scores < 0.5 excluded (n = 1406 clusters not excluded, pooled from five samples).

To analyze a more challenging dataset, we sought to quantify clathrin-coated pits in MDA-MB-231 cells. To do this, we performed 3D dSTORM on fixed cells labeled for clathrin. A representative reconstruction of all molecules projected in 2D is shown in Fig. 6g, with a select region shown in Fig. 6h, illustrating the pit structure. DBOpt was performed on each 3D dataset with DBSCAN (Fig. 6i). Maximum DBCV scores were between 0.09 and 0.15, above the corresponding noise threshold for the MinPts parameters used (Fig. S8 and Table S3). A selection of identified clusters is shown in Fig. 6j, with the corresponding full cell clathrin clustering results shown in Fig. S9. All clusters from the full cell results were evaluated for size, excluding clusters with a negative individual cluster score. The mean FWHM of clathrin clusters was found to be 145 ± 40 nm, in agreement with previously reported results (Fig. 6l)39. Excluding clusters with low individual cluster scores may be useful in particular cases. Here, evaluating clusters with a stricter individual cluster score requirement (individual cluster score ≥ 0.5; inset Fig. 6l) minimally affects results (FWHM 141 ± 39 nm). We note that while the FWHMs of clathrin clusters across five analyzed images were in close agreement with previous results, one result showed a distribution with notably greater cluster size (Table S3). We explored this further in Supporting Text 7 and showed that when experiments have a high level of noise and are therefore difficult to cluster, selecting a single parameter combination that results in the best average DBCV score across all datasets can reduce variability between datasets (Table S4).

The number of localizations and corresponding runtimes for all experimental datasets are shown in Table S5. Here, runtimes vary greatly between datasets, with a larger number of localizations typically corresponding to longer runtimes. In cases where datasets could be prohibitively large, we suggest using DBOpt to identify optimal parameters on a subset of the full data to improve runtimes (Supporting Text 8 and Table S5). We demonstrate the effectiveness of this approach by plotting cluster sizes for full cell data between the originally selected parameters and those identified through such sub-sampling, which are in close agreement (Figs. S10, S11).

Discussion

Cluster analysis is a common and important step in interpreting SMLM data. However, the importance of proper parameter selection is often overlooked, as evidenced by the relative lack of guidance for parameter selection in the literature. For these reasons, we developed DBOpt, which employs (1) a novel and efficient implementation of the internal validation metric DBCV, termed k-DBCV for its use of a k-dimensional tree and (2) a procedure for leveraging k-DBCV to choose optimal clustering parameters, incorporating Bayesian optimization to efficiently optimize large parameter spaces. Taken together, the DBOpt method provides a valuable tool for selecting robust and reproducible clustering parameters without the need for domain knowledge.

The results from simulated datasets suggest that in most scenarios, DBOpt, without ground truth information, is nearly equal in performance to naive EVS as evaluated via V-measure. Furthermore, we demonstrate DBOpt performance on experimental data and show sensible results from cluster evaluation. Among the clustering algorithms tested, DBSCAN was the best-performing algorithm for most simulated datasets. Paired with its relative simplicity and speed, we recommend DBSCAN when clustering SMLM data. While we evaluated DBSCAN, HDBSCAN, and OPTICS, DBOpt can be readily adapted to evaluate performance with any density-based algorithm, such as density peak or DENCLUE clustering, which could be a preferable approach for some datasets40,41.

Through the approach outlined herein, we expect that DBOpt will improve both the integrity and reproducibility of SMLM clustering. While this work highlights the utility of DBOpt for SMLM data, the importance of accurate clustering extends across biology and into many other fields of study42,43,44,45. Thus, we expect DBOpt to have many practical use cases outside of SMLM.

Methods

Simulations

Simulated data were generated using our custom-built Python library (ClustSim: https://github.com/Kaufman-Lab-Columbia/ClustSim). Generally, for each cluster, a centroid was randomly chosen on the ≈3 × 3 μm simulation plane, and points were placed around this centroid. When simulating in 3D, an additional axial dimension of 3 μm was added. Circular, spherical, and elliptic clusters were built by making random selections from a normal distribution centered around the centroid in each dimension. The cluster width was defined as four standard deviations of the underlying normal distribution. For elliptic clusters, the distribution was stretched randomly along one direction, defined by the desired aspect ratio. For micellular clusters, points were randomly and uniformly distributed between an inner and outer diameter, with the inner diameter defined as two-thirds of the outer diameter. Fibrillar clusters were generated via a three-step process. First, the fiber backbone was grown from a random starting point along a simulated trajectory, defined by an angular path dictating the direction of longitudinal growth. The angular path was generated using the method described in ref. 46. Subsequently, point deposition to a specified density was conducted around each backbone point using a normal distribution, with four standard deviations of the distribution equal to the reported widths. Finally, for clusters containing a variety of shapes, clusters were simulated separately and merged, ensuring that clusters were adequately separated by eye.

Each simulation was generated on a simulation plane containing either randomly distributed or gradient noise to mimic inhomogeneous illumination. Gradient noise was generated by increasing the percentage of points distributed every 300 nm in the x direction, such that the right-most side of the simulation had approximately four times more noise points than the left-most side. For multi-emitter simulations, the number of localizations at each target point was drawn from a Poisson distribution with a mean of three positions per molecule.

In all cases, after placement, point positions were relocated in the x, y, and (where relevant) z directions to mimic uncertainties associated with SMLM imaging. Each molecule was moved within an FWHM defined from a log-normal distribution47. This log-normal distribution was set with a mean uncertainty of 20 nm for the lateral directions and 50 nm axially for 3D simulations with a standard deviation of 5.7 nm33,47,48. Parameter information for each simulation can be found in Supporting Text 2 and Tables S1a–f.

DBOpt

DBOpt (DBOpt: https://github.com/Kaufman-Lab-Columbia/DBOpt) was performed by combining the improved implementation of DBCV (k-DBCV: https://github.com/Kaufman-Lab-Columbia/k-DBCV) with Bayesian optimization. Bayesian optimization was performed with a pre-built library using a Gaussian prior with an upper confidence bound acquisition function (Bayesian Optimization: https://github.com/bayesian-optimization/BayesianOptimization)27. For all simulations, hyperparameters were chosen to attempt to cover the relevant parameter space for all clustering scenarios and simulations while also testing the data against the minimum possible MinPts parameters for k-DBCV. For all simulations, 40 random sets of parameters were probed initially, followed by 200 optimization iterations (Supporting Text 1). The parameter space explored was 3 to 200 for all parameters of DBSCAN and HDBSCAN, and the MinPts parameter of OPTICS. For OPTICS, the ξ parameter space was optimized between 0.005 and 0.5.

At each optimization iteration, the DBCV score was calculated as described in Eqs. 1 and 221. Here, sparseness and separation are defined as the largest intra-cluster and smallest inter-cluster mutual reachability distances (MRD) between nearest neighboring core points, respectively. The mutual reachability distance between points is calculated as:

Here, oi is a point within the dataset, oj is any other point, Edist is the Euclidean distance between points, and allptscoredist is defined as:

where d is the number of dimensions, ni is the points in the cluster i, and KNN is the Kth nearest neighbor from point o in cluster i. We note that a minimum of three points is required for a cluster to have at least one core point. Here, we require core points to compute individual cluster scores; therefore, k-DBCV prohibits clusters with fewer than three points and automatically reclassifies points belonging to these clusters as noise.

After completing the optimization iterations, the parameter combinations with the highest DBCV scores to two significant figures were selected. Subsequently, from this set, the single parameter combination with the highest median individual cluster scores was chosen as the optimal clustering assignment. The data was then clustered with those parameters, and in the case of simulated data, external validation was performed for comparison to ground truth information and naive EVS.

External validation

Naive EVS was performed by analyzing every fifth value of each parameter between 3 and 200 for DBSCAN, HDBSCAN, and the MinPts OPTICS parameter. The ξ parameter of OPTICS was analyzed every 0.0125 between 0.005 and 0.5. V-measure was employed for external validation. V-measure is given by:

Here, homogeneity (h) and completeness (c) were calculated for comparison to ground truth information as described by Rosenberg et al.32. β was set to 1 to equally balance homogeneity and completeness. was set to 1 to balance homogeneity and completeness. V-measure is bounded between 0 and 1, with a score of 1 representing clusters that match perfectly with the ground truth assignment. We note that for simulations with noise, there is no distinction between noise placed inside or outside of simulated clusters. Thus, for such simulations, V-measure scores are expected to be high but < 1 even for optimal clustering, as noise points that fall inside clusters will likely be assigned to those clusters.

Cell preparation

MDA-MB-231 cells obtained from the American Type Culture Collection were used for both integrin and clathrin experiments. Cells were cultured at 37 oC and 5% carbon dioxide in high glucose DMEM (Fisher Scientific) with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 1% (v/v) 100x penicillin-streptomycin-amphotericin B (MP Biomedicals), and 1% (v/v) 100x non-essential amino acid solution (Gibco). Prior to cell experiments, 35 mm high-tolerance dishes (P35G-0.170-14-C: MatTek Corporation) were coated with 1 mL of 50 μg/mL acid-solubilized rat tail collagen type I (Advanced Biomatrix) in sterile filtered 20 mM acetic acid (97 + %, Sigma Aldrich) for 1 h. The plates were washed three times with 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Cytiva). Tetraspeck microspheres (Invitrogen) of diameter 0.1 μm were added at a concentration of ~4 × 1015 microspheres/mL in 1X PBS for 10 min at room temperature to deposit fiducials for later drift correction in post-processing. The plates were washed again three times with 1X PBS.

Cells were detached with Accutase (MP Biomedicals) and then seeded onto the coated, high-tolerance 35 mm dishes at a density of 100,000 cells/dish in 2 mL high glucose DMEM and incubated for 1.5 h before fixing. Prior to fixing, cells were washed twice with 37 oC 1X PBS. For β1 integrin labeling, cells were fixed by initially adding 0.3% glutaraldehyde (8% EM grade solution, Electron Microscopy Sciences) and 0.25% Triton X-100 (10% solution, EMD Millipore Chemicals) in 1X PBS at 37 oC for 1 min followed by 4% methanol-free paraformaldehyde (16% solution, Thermo Scientific) in 1X PBS at 37 oC for 10 min. For clathrin experiments, 4% methanol-free paraformaldehyde in 1X PBS was added for 10 min at 37 oC. After fixing, quenching with 50 mM ammonium chloride (Sigma Aldrich) for 15 min was performed. Cells were washed for 10 min three times with 1X PBS. Triton X-100 (0.2%) was applied for 10 min to permeabilize the cell membrane, followed by three 10 min washes with 1X PBS.

Active β1 integrin was labeled with 9EG7 monoclonal antibody (0.5 mg/mL solution, BD Biosciences, 553715). The antibody was first conjugated to Alexa Fluor 647 NHS ester (Invitrogen). Alexa Fluor 647 NHS ester was dissolved in anhydrous dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma Aldrich) and dried for storage. The aliquots were desiccated and stored at −20 oC. Before conjugation, bovine serum albumin (BSA) was removed (when applicable) from the stock antibody solution with an antibody conjugation kit according to the manufacturer's instructions (Abcam). After BSA removal, the antibody concentration was measured via UV-vis with a Nanodrop Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific). The antibody was then conjugated with Alexa Fluor 647 NHS ester at a 4:1 fluorophore-to- antibody molar ratio for 30 min by adding 2 μL of reconstituted Alexa Fluor 647 in sterile DMSO (Sigma Aldrich) to 10 μL of 0.5 M sodium bicarbonate (7.5% stock, Gibco) and 40 μL of antibody solution in 1X PBS. Following conjugation, the antibody was purified with an Antibody Conjugate Purification Kit (Invitrogen). Briefly, the column was rinsed three times with 1X PBS and centrifuged at 1100×g. The antibody was then added to the column and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. The final solution was collected via centrifugation at 1100×g. The resulting fluorophore-to-antibody ratio was measured via UV-vis and calculated to be 1.6:1.

The conjugated 9EG7-Alexa Fluor 647 was diluted in 1% BSA (w/w) (Fisher Bioreagents) in 1X PBS for a final concentration of 10 μg/mL along with 10 μg/mL EPR8185 anti-vinculin Alexa Fluor 488 antibody (0.5 mg/mL solution, Abcam, ab196454). To label cells, 100 μL of antibody solution was added to the plate to fully cover the inner surface of the dish. The solution was incubated for 18 h at ~4 oC. After labeling, the cells were washed three times with 1% BSA in 1X PBS.

To label clathrin, a polyclonal anti-clathrin heavy chain antibody (0.9 mg/mL solution, Abcam, ab21679) was diluted to a final concentration of 3.3 μg/mL with 1% BSA (w/w) in 1X PBS. About 100 μL of antibody solution was added to the plate to fully cover the surface, and the solution was incubated for 18 h at ~4 oC. The plate was washed three times with 1% BSA (w/w) in 1X PBS for 10 min. About 100 μL of 4 μg/mL secondary, goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647 antibody (highly cross-adsorbed, Invitrogen) in 1% BSA (w/w) in 1X PBS was then added and incubated at room temperature for 1 h. The dish was washed again three times with 1% BSA (w/w) in 1X PBS following secondary antibody labeling.

Imaging

Prior to imaging, 1 mL of freshly prepared OxEA imaging buffer was added to the samples49. The buffer was composed of 3% (v/v) Oxyfluor (Oxyrase), 20% (v/v) sodium DL lactate (60% stock, Sigma Aldrich), and 50 mM cysteamine hydrochloride (Sigma Aldrich), all in 1X PBS with pH adjusted to 8–8.5 with 1 N NaOH (Sigma Aldrich). Images were acquired on a Zeiss Elyra 7 microscope. For 2D experiments, an initial image of vinculin was acquired using a 488 nm laser via total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF). For 2D SMLM, localizations were acquired over 30,000 frames with an exposure time of 30 ms in a TIRF configuration. For 3D acquisition, the microscope relies on a spatial light modulator to split the vertically polarized light into two lobes, forming a double helix point spread function (DH-PSF)50. Prior to imaging, a 0.1 μm Tetraspeck microsphere was imaged for calibration of the DH-PSF according to the manufacturer's instructions, such that the z-position of the PSFs could be extracted after acquisition. The localizations were acquired over 50,000 frames with an exposure time of 30 ms via highly inclined and laminated optical sheet (HILO) microscopy.

To process localizations found in 2D, the ThunderSTORM plugin was used within ImageJ, following the recommended protocol in the ThunderSTORM user guide51. Images were first filtered using a wavelet filter (B-spline order of 3 and B-spline scale of 2), after which molecules were identified using the local maximum approach (eight connected neighbors) with a peak intensity threshold of 1.5 times the standard deviation of the first wavelet level. Identified molecules were fit to an integrated Gaussian using the maximum likelihood method, with a fitting radius of five pixels and an initial standard deviation of 1.6 pixels. Spurious localizations were removed from reconstructed images by applying a minimum intensity cutoff of 50 photons, restricting the standard deviation of the Gaussian fit over the emission peak to 50–250 nm, and removing molecules with a lateral localization uncertainty greater than 35 nm. Lateral stage drift was corrected by tracking positions of ~3–6 fiducial markers (Tetraspeck microspheres, see above plating procedure) during the course of image acquisition. Axial drift was limited by using the microscope autofocus (Zeiss, Definite Focus system) in combination with a piezo stage to continuously maintain axial position for the duration of the imaging experiment. After drift correction using ThunderSTORM, molecules within 20 nm of each other were merged when in the on-state consecutively between frames, with a maximum off-time tolerance of three frames. Processing of 3D STORM data were performed within the Zen Black software (Zeiss). Axial position was first determined from the DH-PSF calibration. To remove outliers, the lateral localization uncertainty was filtered to be between 5 and 35 nm, and the axial uncertainty was filtered to be between 5 and 60 nm. The background variance of the number of photons was set to less than 80. The images were drift corrected both laterally and axially with the 0.1 μm Tetraspeck microsphere fiducials.

For 2D integrin images, DBOpt was performed on the full cell. After clustering with the optimal parameters found for DBSCAN, clusters that fell within ROIs defined by the presence of vinculin were analyzed. For clathrin localization, DBOpt was first run on the full cell in 3D, and the identified clusters were projected onto an x-y plane. The covariance matrix of each cluster was used to find the long axis (length) and short axis (width). The clusters were treated as bivariate normal distributions, where the FWHM of each cluster was calculated. For clathrin clusters, the short-axis FWHM is reported.

Statistics and reproducibility

DBOpt was tested on 125 unique 2D simulated datasets with 25 simulations associated with each of five cluster types shown in Fig. 2. Details on each simulated dataset are shown in Table S1a–e. For 3D data, 20 unique simulated datasets were analyzed across ellipsoid (n = 10) and 3D fibrillar (n = 10) datasets. The details for all 3D simulations are shown in Table S1f. For experimental data, in both the integrin and clathrin analyses, five single cells, chosen from distinct areas on a single coverslip, were analyzed. Pooled results from DBOpt clustering of experimental data are shown in Fig. 6. We performed a two-sided paired t-test for data corresponding to Fig. 4e and a two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test for data corresponding to Figs. 4f, g, 5d–f. The results of these tests, including the p values and test statistic, are shown in Supporting Text 4, Table S2a–d.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Simulated datasets are available at https://github.com/Kaufman-Lab-Columbia/DBOpt52. The source data for all the graphs in the paper can be found in Supplementary Data 1. Experimental imaging data is available upon request.

Code availability

DBOpt code is available at https://github.com/Kaufman-Lab-Columbia/DBOpt52. k-DBCV code is available at https://github.com/Kaufman-Lab-Columbia/k-DBCV53. Cluster simulation code (ClustSim) is available at https://github.com/Kaufman-Lab-Columbia/ClustSim54.

References

Lelek, M. et al. Single-molecule localization microscopy. Nat. Rev. Methods Prim. 1, 39 (2021).

Rust, M. J., Bates, M. & Zhuang, X. Sub-diffraction-limit imaging by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM). Nat. Methods 3, 793–795 (2006).

Betzig, E. et al. Imaging intracellular fluorescent proteins at nanometer resolution. Science 313, 1642–1645 (2006).

Sharonov, A. & Hochstrasser, R. M. Wide-field subdiffraction imaging by accumulated binding of diffusing probes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 18911–18916 (2006).

Baddeley, D. & Bewersdorf, J. Biological insight from super-resolution microscopy: what we can learn from localization-based images. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 87, 965–989 (2018).

Khater, I. M., Nabi, I. R. & Hamarneh, G. A review of super-resolution single-molecule localization microscopy cluster analysis and quantification methods. Patterns 1, 100038 (2020).

MacQueen, J. and others. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. Berkeley Symp. Math. Stat. Probab. 1, 281–297 (1967).

Yang, M. S., Lai, C. Y. & Lin, C. Y. A robust EM clustering algorithm for Gaussian mixture models. Pattern Recognit. 45, 3950–3961 (2012).

Ward, J. H. Jr Hierarchical grouping to optimize an objective function. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 58, 236–244 (1963).

Xu, R. & Wunsch, D. Survey of clustering algorithms. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 16, 645–678 (2005).

Campello, R. J. G. B., Kröger, P., Sander, J. & Zimek, A. Density-based clustering. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 10, 1–15 (2020).

Bhattacharjee, P. & Mitra, P. A survey of density based clustering algorithms. Front. Comput. Sci. 15, 1–27 (2021).

Rubin-Delanchy, P. et al. Bayesian cluster identification in single-molecule localization microscopy data. Nat. Methods 12, 1072–1076 (2015).

Ester, M., Kriegel, H. P., Sander, J. & Xu, X. A density-based algorithm for discovering clusters in large spatial databases with noise. KDD 96, 226–231 (1996).

Nieves, D. J. et al. A framework for evaluating the performance of SMLM cluster analysis algorithms. Nat. Methods 20, 259–2667 (2023).

Campello, R. J. G. B., Moulavi, D. & Sander, J. in Advances in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining (eds Pei, J., Tseng, V. S., Cao, L., Motoda, H. & Xu, G.)(Springer, 2013).

McInnes, L. & Healy, J. Accelerated hierarchical density based clustering. 2017 IEEE Int. Conf. Data Min. Work. 33, 42 (2017).

Ankerst, M., Breunig, M. M., Kriegel, H. P. & Sander, J. OPTICS: ordering points to identify the clustering structure. ACM Sigmod Rec. 28, 49–60 (1999).

Arbelaitz, O., Gurrutxaga, I., Muguerza, J., Pérez, J. M. & Perona, I. An extensive comparative study of cluster validity indices. Pattern Recognit. 46, 243–256 (2013).

Xiong, H. & Li, Z. in Data Clustering: Algorithms and Applications (eds Aggarwal, C. C. & Reddy, C. K.) Ch. 23 (Chapman & Hall/CRC, 2014).

Moulavi, D., Jaskowiak, P. A., Campello, R. J., Zimek, A. & Sander, J. Density-based clustering validation. In Proc. 2014 SIAM International Conference on Data Mining 839–847 (SIAM, 2014).

Halkidi, M. & Vazirgiannis, M. A density-based cluster validity approach using multi-representatives. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 29, 773–786 (2008).

McInnes, L., Healy, J. & Astels, S. hdbscan: hierarchical density based clustering. J. Open Source Softw. 2, 205 (2017).

Jenness, C. DBCV. GitHub https://github.com/christopherjenness/DBCV (2017).

Siqueira, F. A. DBCV. GitHub https://github.com/FelSiq/DBCV (2024).

Maneewongvatana, S. & Mount, D. Analysis of approximate nearest neighbor searching with clustered point sets. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/cs/9901013 (1999).

Nogueira, F. Bayesian optimization: open source constrained global optimization tool for Python. https://github.com/fmfn/BayesianOptimization (2014).

Snoek, S., Larochelle, H. & Adams, R. P. Practical Bayesian optimization of machine learning algorithms. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 25, 2951–2959 (2012).

Rosenberg, A. & Hirschberg, J. V.-measure: a conditional entropy-based external cluster evaluation measure. In Proc. 2007 Joint Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing and. Computational Natural Language Learning 410–420 (Association for Computational Linguistics, 2007).

Hubert, L. & Arabie, P. Comparing partitions. J. Classif. 2, 193–218 (1985).

Fowlkes, E. B. & Mallows, C. L. A method for comparing two hierarchical clusterings. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 78, 553–569 (1983).

Vinh, N. X., Epps, J. & Bailey, J. Information theoretic measures for clusterings comparison: is a correction for chance necessary? In Proc. 26th Annual International Conference on Machine Learning, 1073–1080 (ACM, 2009).

Huang, B., Wang, W., Bates, M. & Zhuang, X. Three-dimensional super-resolution reconstruction microscopy by stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy. Science 319, 810–813 (2008).

Stubb, A. et al. Superresolution architecture of cornerstone focal adhesions in human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Commun. 10, 4756 (2019).

Peng, X., Nelson, E. S., Maiers, J. L. & DeMali, K. A. New insights into vinculin function and regulation. Int. Rev. Cell Mol. Biol. 287, 191–231 (2011).

Bazzoni, G., Shih, D.-T., Buck, C. A. & Hemler, M. E. Monoclonal antibody 9EG7 defines a novel β1 integrin epitope induced by soluble ligand and manganese, but inhibited by calcium. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 25570–25577 (1995).

Spiess, M. et al. Active and inactive β1 integrins segregate into distinct nanoclusters in focal adhesions. J. Cell Biol. 217, 1929–1940 (2018).

Keary, S., Mateos, N., Campelo, F. & Garcia-Parajo, M. F. Differential spatial regulation and activation of integrin nanoclusters inside focal adhesions. eLife 14, RP105270 (2025).

Jones, S. A., Shim, S. H., He, J. & Zhuang, X. Fast, three-dimensional super-resolution imaging of live cells. Nat. Methods 8, 499–505 (2011).

Rodriguez, A. & Laio, A. Clustering by fast search and find of density peaks. Science 344, 1492–1496 (2014).

Hinneburg, A. & Keim, D. A. An efficient approach to clustering in large multimedia databases with noise. In Proceedings of the Fourth International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining 58–65 (AAAI Press, 1998).

Liu, J. et al. Epitranscriptomic subtyping, visualization, and denoising by global motif visualization. Nat. Commun. 14, 5944 (2023).

Petegrosso, R., Li, Z. & Kuang, R. Machine learning and statistical methods for clustering single-cell RNA-sequencing data. Brief. Bioinform. 21, 1209–1223 (2019).

Ghosal, A., Nandy, A. K. Das, K., S. Goswami, S, & Panday, M. A short review on different clustering techniques and their applications. In Emerging Technology in Modelling and Graphics. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing (eds Mandal, J. & Bhattacharya, D.) (Springer, 2020)

Spielman, S. E. & Thill, J. C. Social area analysis, data mining, and GIS. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 32, 110–122 (2008).

Bi, D., Yang, X., Marchetti, M. C. & Manning, M. L. Motility-driven glass and jamming transitions in biological tissues. Phys. Rev. X 6, 1–13 (2016).

Mollazade, M. et al. Can single molecule localization microscopy be used to map closely spaced RGD nanodomains?. PLoS ONE 12, 1–17 (2017).

Dempsey, G. T., Vaughan, J. C., Chen, K. H., Bates, M. & Zhuang, X. Evaluation of fluorophores for optimal performance in localization-based super-resolution imaging. Nat. Methods 8, 1027–1040 (2011).

Nahidiazar, L. et al. Optimizing imaging conditions for demanding multi-color super resolution localization microscopy. PLoS ONE11, 1–18 (2016).

Pavani, S. R. P. et al. Three-dimensional, single-molecule fluorescence imaging beyond the diffraction limit by using a double-helix point spread function. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 2995–2999 (2009).

Ovesný, M., Křížek, P., Borkovec, J., Švindrych, Z. & Hagen, G. M. ThunderSTORM: a comprehensive ImageJ plug-in for PALM and STORM data analysis and super-resolution imaging. Bioinformatics 30, 2389–2390 (2014).

Hammer, J. L. et al. DBOpt v1.0.0. GitHub https://github.com/Kaufman-Lab-Columbia/DBOpt. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15489756 (2025).

Hammer, J. L. et al. k-DBCV v1.0.0. GitHub https://github.com/Kaufman-Lab-Columbia/k-DBCV. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15489735 (2025).

Hammer, J. L. et al. ClustSim v1.0.0. GitHub https://github.com/Kaufman-Lab-Columbia/ClustSim. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15489690 (2025).

Acknowledgements

J.L.H. acknowledges funding from the Katherine Lee Chen Fellowship at Columbia University. We acknowledge the Precision Biomolecular Characterization Facility for the use of the Zeiss Elyra 7 microscope.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology and data visualization: J.L.H., A.J.D., L.J.K.; Formal analysis and Writing—original draft: J.L.H.; Writing—review and editing: J.L.H. and L.J.K., Writing—code implementation: J.L.H. and A.J.D., Supervision, project administration and funding acquisition: L.J.K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Laura Rodríguez Pérez. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hammer, J.L., Devanny, A.J. & Kaufman, L.J. Bayesian optimized parameter selection for density-based clustering applied to single molecule localization microscopy. Commun Biol 8, 902 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08332-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-025-08332-0

This article is cited by

-

Enhanced spatial clustering of single-molecule localizations with graph neural networks

Nature Communications (2025)