Abstract

Lactacystin is an irreversible proteasome inhibitor isolated from Streptomyces lactacystinicus. Despite its importance for its biological activity, the biosynthesis of lactacystin remains unknown. In this study, we identified the lactacystin biosynthetic gene cluster by gene disruption and heterologous expression experiments. We also examined the functions of the genes encoding a PKS/NRPS hybrid protein (LctA), NRPS (LctB), ketosynthase-like cyclase (LctC), cytochrome P450 (LctD), MbtH-like protein (LctE), and formyltransferase (LctF) by in vivo and in vitro experiments. In particular, we demonstrated that LctF directly transferred the formyl group of 10-N-formyl tetrahydrofolate to CoA. The formyl group of formyl-CoA was then transferred to ACP1 by LctA_AT1 to form formyl-ACP1. This is the first example of an AT domain recognizing a formyl group. The formyl group is perhaps transferred to methylmalonate tethered on LctA_ACP2 to yield methylmalonyl-semialdehyde-ACP2. Then, it would be condensed with leucine bound to PCP in LctB by the C domain in LctA. Using a mimic compound, we confirmed that LctC catalyzed the formation of the cyclic α,α-disubstituted amino acid structure with concomitant release of the product from PCP. Thus, we figured out the overall biosynthesis of lactacystin including a novel role of a formyl group in a secondary metabolite.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lactacystin (1) is a 20S proteasome inhibitor isolated from Streptomyces lactacystinicus by Omura et al. in 19911. Because of its potency and specificity toward the 20S proteasome, lactacystin has been used for various studies of proteasome functions and mechanisms2,3,4,5,6. The mode of action of lactacystin has already been elucidated. Omuralide (2) formed through the spontaneous elimination of the N-acetylcysteine moiety from lactacystin irreversibly binds to the N-terminal Thr residue of the proteasome’s beta subunit via β-lactone ring opening4,5,7. This results in the loss of proteasomal protein degradation activity.

Lactacystin possesses a unique structure comprising a complicated cyclic α,α-disubstituted amino acid including a γ-lactam-β-lactone. α,α-Disubstituted amino acids are relatively rare moieties in natural products but a few examples of their biosynthesis have been reported, including salinosporamide A8, altemicidin9, labionin-containing peptide natural products such as microvionin10,11, α-Me-l-Ser (a building block of JBIR-34 and -35)12, and dimethylglycine13 (a building block of tryptoquialanine and other peptides) as shown in Figs. 1 and S1.

In the biosynthesis of salinosporamide A, the ketosynthase (KS)-like protein SalC forms the α,α-disubstituted amino acid including a γ-lactam-β-lactone with an acylated nonproteinogenic amino acid intermediate bound to the peptidyl carrier protein (PCP) in PKS-NRPS with concomitant off-loading of the product from the PCP domain (Fig. S1)8. As for the formation of γ-lactam-β-lactone moiety, Moore et al. proposed the reaction mechanism. The substrate is attached to the side chain of a Cys residue. Then, α-proton is abstracted by a His residue followed by an intermolecular aldol reaction to form a γ-lactam moiety. Subsequently, the oxyanion emerged during the aldol reaction attacks to thioester to form a β-lactone moiety with concomitant off-loading of the product from SalC (Fig. S2). Because the chemical structure of the γ-lactam-β-lactone moiety in salinosporamide A is similar to that in lactacystin and omuralide, the lactam-forming mechanisms might be similar. However, the other biosynthetic mechanisms of lactacystin are still elusive.

To investigate the biosynthetic mechanism of the cyclic α,α-disubstituted amino acid moiety in lactacystin, some feeding experiments using stable-isotope labeled compounds were previously conducted14,15. L-[2-13C]leucine, [1-13C]isobutyrate, L,L-[1,1ʹ-13C2]cystine, and [1-13C]propionate were incorporated into lactacystin. With universal 13C-labeled l-leucine, all six carbons were incorporated into lactacystin (Fig. S3). These results suggested that methylmalonate semialdehyde formed from isobutyrate and Leu would be the building blocks of the omuralide moiety. However, there are no studies on the genes and enzymes responsible for the biosynthesis of lactacystin.

Here, we identified the biosynthetic gene cluster of lactacystin and examined the functions of the genes in the cluster by gene inactivation and heterologous expression experiments. Furthermore, we conducted in vitro experiments to confirm the biosynthetic reactions. The results revealed the overall biosynthesis of lactacystin and provided new insights into the molecular bases for the engineering of lactacystin biosynthesis.

Results and discussion

Identification of the biosynthetic gene cluster of lactacystin

To identify the biosynthetic gene cluster of lactacystin, we conducted a draft genome analysis of its producer, S. lactacystinicus NBRC 110082. Based on the chemical structure of lactacystin and the results of previous tracer experiments, the core structure of lactacystin was suggested to be formed by a PKS-NPRS system. By searching for PKS-NRPS hybrid proteins in the draft genome, several candidate genes were found. Among them, one PKS-NRPS gene was surrounded by genes similar to those in the salinosporamide A biosynthetic gene cluster (sal)8. In particular, an ortholog of the salC gene responsible for the formation of the γ-lactam-β-lactone moiety, which is found in both lactacystin and salinosporamide A, existed in the cluster. We therefore speculated that this region is responsible for the biosynthesis of lactacystin. The putative cluster was composed of a gene coding for a major facilitator superfamily (MFS) transporter (lctT), a hypothetical gene (lctH), genes similar to sal genes (lctA–E), and a formyltransferase gene (lctF) (Fig. 2a and Table S4). To examine whether the cluster is involved in lactacystin biosynthesis, we in-frame deleted the lctD gene encoding cytochrome P450, which perhaps hydroxylates the leucine moiety (Fig. S4). The resultant disruptant strain (∆lctD) lost lactacystin productivity, indicating that LctD is involved in lactacystin biosynthesis (Fig. 2b). Moreover, we observed accumulation of a compound with m/z 361, which is 16 mass units less than that of lactacystin (Figs. 2b and S5). This suggested that the compound was dehydroxyl-lactacystin (7) but we were unable to determine its exact structure because of low productivity. To narrow down the essential genes for lactacystin production, we employed a heterologous expression experiment. Two DNA fragments possessing “lctT to lctF” and “lctA to lctF” were prepared by PCR and each was inserted into a shuttle vector. The constructed plasmids were introduced into Streptomyces lividans TK23. The strains possessing lctT–lctF (8 genes) and lctA–lctF (6 genes) produced significant and small amounts of lactacystin, respectively. In contrast, the strain harboring the empty vector produced no lactacystin (Fig. 2c). These findings suggested that LctA–LctF play a vital role in lactacystin biosynthesis and that LctT and LctH might be crucial for high productivity.

a Biosynthetic gene cluster of lactacystin. The cluster contains lctA, PKS-NRPS (ACP, acyl carrier protein; KS, ketosynthase; AT, acyltransferase; C, condensation domains); lctB, NRPS (A, adenylation; PCP, peptidyl carrier protein domains); lctC, cyclase; lctD, cytochrome P450; lctE, MbtH-like protein (MLP); and lctF, formyltransferase. b LC-ESI-MS analysis (positive ion mode, monitored at m/z 377 (black) and 361 (blue)) of (i) lactacystin standard and broths of (ii) the wild-type strain and (iii) the ∆lctD strain. Traces monitored at m/z 377 were enlarged 25-fold vertically. A peak (*) with mass of 361.1439 corresponding to 7 (calculated mass, 361.1428) was detected (Fig. S5). c LC-ESI-MS analysis (positive ion mode, monitored at m/z 377) of (i) lactacystin standard and broths of transformants harboring (ii) lctT to lctF, (iii) lctA to lctF, and (iv) the empty vector. d LC-ESI-MS analysis (positive ion mode, monitored at m/z 377) of (i) lactacystin standard and broths of transformants harboring (ii) lctT, B, C, D, E, F, and ACP1-inactivated lctA (S45A) and (iii) lctB, C, D, E, F, and AT1-inactivated lctA (S791A).

Putative Biosynthetic Pathway of Lactacystin

Based on the abovementioned results and in silico analysis, the biosynthetic pathway of lactacystin was estimated as follows (Fig. 3). A putative formyltransferase (LctF) transfers a formyl group into CoA from 10-N-formyl tetrahydrofolate (10N-fTHF) to form formyl-CoA, and then the formyl group is loaded onto ACP1 by LctA_AT1. Concurrently, LctA_AT2 loads a methylmalonyl moiety, which is supplied from methylmalonyl-CoA, onto ACP2; this possibility was predicted by multiple alignment analysis of the AT2 domain (Fig. S6). Then, the KS domain in LctA catalyzes a Claisen-type condensation to form ACP2-tethered methylmalonyl-semialdehyde (3). The A domain of LctB likely loads Leu or 3-hydroxyl-Leu (OH-Leu) formed by LctD onto PCP domain of LctB after activation by adenylation. The MbtH-like protein (LctE) perhaps interacts with and activates the A domain16. Next, compound 3 tethered to ACP2 and Leu or OH-Leu bound to PCP are condensed to form an intermediate, 4 or 5, by the C domain in LctA. The intermediate is then cyclized and off-loaded by a stand-alone KS-like cyclase, LctC, to give 6 or 2 in a manner similar to the biosynthesis of salinosporamide A. It is then converted into 7 or lactacystin (1) by spontaneous addition of N-acetyl cysteine7. We next examined the plausibility of these proposed pathways by in vivo and in vitro analysis.

ACP1 and AT1 in LctA were essential for lactacystin biosynthesis

First, the functions of the ACP1 and AT1 domains in LctA (PKS-NRPS hybrid) were investigated because of its unique domain organization. LctA consisted of ACP1-KS-AT1-AT2-ACP2-C domains but the existence of an ACP domain as the first domain is rare in PKS-NRPS hybrid enzymes and the same is true for the last C domain17. Furthermore, it was impossible to predict the substrate of the AT1 domain from its amino acid sequence using programs such as Minowa through antiSMASH 7.0 analysis18,19. Therefore, we investigated whether ACP1 and AT1 were necessary for lactacystin biosynthesis. We constructed two derivatives from the plasmid used for heterologous expression, in which ACP1 or AT1 was inactivated by replacing the active Ser residue with an Ala residue (ACP1 (S45A) and AT1 (S791A)). The plasmids were then introduced into S. lividans and each culture broth of the transformants was analyzed by LC-ESI-MS. As shown in Fig. 2d, both transformants lost lactacystin productivity, indicating that both AT1 and ACP1 were necessary for the biosynthesis of lactacystin.

Formyltransferase (LctF) catalyzed formation of formyl-CoA

We next performed in vitro analysis of LctF, which has 32% identity to methionyl-tRNA formyltransferases. This type of enzyme usually requires 10N-fTHF as a formyl group donor, which was chemoenzymatically prepared from commercially available 5N-fTHF (Fig. S7)20,21. 5N-fTHF was anaerobically acidified with 1 M HCl in the presence of 1 M mercaptoethanol to form 5,10N-methylene THF20. Recombinant 5,10N-methylene THF cyclohydrolase FolD was then added to the neutralized reaction mixture to synthesize 10N-fTHF. Because 10N-fTHF is unstable and sensitive to molecular oxygen21, it was directly used for the in vitro reaction of LctF without purification, and all solutions used for the preparation and the in vitro reaction were bubbled with N2 before use. Recombinant LctF was incubated with CoA in the presence of 10N-fTHF under a nitrogen gas atmosphere. We detected a specific peak, which eluted at the same retention time and had the same m/z as the chemically synthesized formyl-CoA, by LC-ESI-MS analysis only in the presence of LctF and 10N-fTHF (Fig. 4a). These results clearly indicated that LctF catalyzed the transfer of a formyl group to CoA with 10N-fTHF as a cofactor. To the best of our knowledge, this is the novel route to biosynthesize formyl-CoA using formyltransferase22,23,24.

a LC-ESI-MS analysis (negative ion mode, monitored at m/z 794) of (i) formyl-CoA standard and reaction mixtures containing (ii) LctF and 10N-fTHF, (iii) 10N-fTHF, and (iv) LctF. b LC-MS analysis of reaction mixtures of LctA_AT1 and formyl-CoA; (i) without LctA_AT1, (ii) with LctA_AT1 (Fig. S8). A mass of 12794.3 corresponding to formyl-ACP1 (calculated mass, 12793.5) was detected in (ii). c LC-MS analysis of reaction mixtures of a triple mutant of LctA_AT1 (M-LctA_AT1) with (i) acetyl-CoA and (ii) formyl-CoA (Fig. S9). A mass of 12807.9 corresponding to acetyl-ACP1 (calculated mass, 12807.5) was detected in (i). d Relative activities of LctA_AT1 and M-LctA_AT1 toward formyl- (For-), acetyl- (Ac-), and malonyl- (Mal-) CoA. The activities were quantified with Ellman’s reagent (DTNB) reacting with free thiol released from the substrates. Error bars indicate standard deviation (SD) (n = 3), and data are presented as mean values ± SD. Black dots denote individual data points.

LctA_AT1 recognized formyl-CoA and transferred the formyl group to ACP1

We next examined the functions of the LctA_AT1 and ACP1 domains in LctA by in vitro analysis. Truncated holo-ACP1 prepared with Sfp25 and recombinant LctA_AT1 were incubated with formyl-CoA, and the reaction mixtures were analyzed by LC-ESI-MS. A specific peak corresponding to formyl-ACP1 was observed only in the presence of LctA_AT1, confirming that LctA_AT1 accepted formyl-CoA and formed formylated ACP1 (Figs. 4b, and S8). This is the first example of an AT domain recognizing formyl-CoA as a substrate.

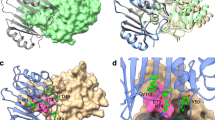

Recognition mechanism of formyl-CoA by LctA_AT1

LctA_AT1 recognized formyl-CoA but its ortholog, SalA_AT1, for salinosporamide A biosynthesis utilizes acetyl-CoA (Fig. 5a). We then examined whether LctA_AT1 accepts acetyl-CoA. However, no specific products were detected by LC-ESI-MS analysis (Fig. S8). To understand the basis of the strict substrate specificity of LctA_AT1, we constructed a modeled structure with local ColabFold (Fig. 5b)26 and compared it with the modeled structures of SalA_AT1 (Fig. 5c)27. The substrate binding pockets of LctA_AT1 and SalA_AT1 were also estimated by comparison with the crystal structure of malonate-bound AT in FabD (Fig. 5d)28. As shown in Fig. 5c, the substrate binding pocket of LctA_AT1 was smaller than that of SalA_AT1 and this observation was reasonable because formyl-CoA is smaller than acetyl-CoA. The residues near the pocket were highly conserved between the two ATs; however, Leu718, Val794, and Leu840 in LctA_AT1 are replaced with Val741, Met820, and Val866 in SalA_AT1 (Fig. 5b, c), suggesting that these residues determine the pocket size. This hypothesis was supported by a modeled structure of mutant LctA_AT1 (M-LctA_AT1) possessing L718V/V794M/L840V replacements. Its pocket size was suggested to be sufficiently larger to accept acetyl-CoA, similar to SalA_AT1 (Fig. 5e). We therefore constructed M-LctA_AT1 and used it for in vitro assay with formyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA as the substrates (Fig. 4c). The LC-ESI-MS analysis revealed that M-LctA_AT1 could accept both formyl-CoA and acetyl-CoA, and the latter was more efficiently accepted (Figs. 4c, d and S9), indicating the importance of the three residues for recognition of the substrate.

a Alignments of orthologs of LctA_AT1 and SalA_AT1. Through genome database search, SalA_AT1 orthologs (1 to 3) and LctA_AT1 orthologs (4 to 9), which constitute similar gene clusters to the salinosporamide A and lactacystin clusters, respectively, were selected (Fig. S10). Residue numbers are based on LctA_AT1 and each accession number is described in Table S5. The red circles indicate pocket-forming residues conserved within each group (LctA_AT1 and SalA_AT1) but that are different between the groups. The His residues shown by the blue circle are usually Arg residues in acyltransferases utilizing malonyl-CoA. b Modeled structure of LctA_AT1. The amino acid residues shown in red are different from those in SalA_AT1. c Modeled structure of SalA_AT1. The substrate-binding pocket is shown by the dashed black circle. d Crystal structure of the AT in FabD accepting malonyl-CoA. The malonate-bound conserved Ser residue is shown (PDB: 2G2Z)28. e Modeled structure of M-LctA_AT1 (L718V/V794M/L840V).

AT domains usually accept malonyl-CoA. However, neither LctA_AT1 nor SalA_AT1 accepted it (Fig. 4d). Previously, an Arg residue in ATs of fatty acids synthase accepting a malonyl-CoA (labeled in blue in Fig. 5d) was reported to be important to recognize malonyl-CoA by making a salt bridge with the carboxylic acid of malonyl-CoA (Fig. 5d)28,29,30. The replacement of the Arg residue to Ala or Lys residue switched the substrate selectivity from malonyl-CoA to acetyl-CoA30. Both LctA_AT1 and SalA_AT1 have His residues instead of Arg at the corresponding position (His 714 in LctA_AT1 and His737 in SalA_AT1, Fig. 5a–c). Therefore, the loss of the salt bridge might be a reason for the unavailability of malonyl-CoA by LctA_AT1 and SalA_AT1.

In vitro Analysis of the Adenylation Domain of NRPS in LctB

Because the hydroxyl group of lactacystin was suggested to be important for biological activity by structure-activity relationship studies7, the hydroxylation timing is an important issue for the engineering of lactacystin derivatives. The hydroxylation enzyme, LctD, perhaps accepts either free Leu or PCP-tethered Leu. We therefore investigated the substrate specificities of the A domain of LctB. We first tried to obtain a full-length LctB, but it was expressed as an insoluble form. Therefore, a truncated A domain was prepared. Because MbtH-like proteins were reported to interact with A domains and to enhance the adenylation activity31, a MbtH-like protein (LctE) was also prepared as a recombinant protein. The recombinant A domain and LctE were incubated with Leu or OH-Leu in the presence of ATP, and then the adenylation activities were measured by detecting the side product, inorganic diphosphate, by colorimetric assay32. The activity with Leu was 10-fold higher than that with OH-Leu (Fig. 6a). This result showed that the hydroxylation would occur after loading of the Leu moiety to NRPS. The adenylation activity without LctE was 20-fold lower than that with LctE (Fig. 6a), showing the importance of LctE in the adenylation reaction catalyzed by the A domain of LctB. The importance of LctE was also postulated by the multimer analysis between A domain in LctB and LctE using ColabFold (Fig. S11)26,31.

a Relative activities of the A domain in LctB with Leu or OH-Leu in the presence of LctE (left) and with Leu in the absence of LctE (right). Error bars indicate standard deviation (SD) (n = 3), and the data are presented as mean values ± SD. Black dots denote individual data points. b HPLC analysis (detected with absorption at 210 nm) of PCP domains in reaction mixtures (i) containing full components (LctB_A domain, LctE and Leu), (ii) without the LctB_A domain, (iii) without LctE, and (iv) with OH-Leu. A mass of 14533.71 corresponding to Leu-PCP (calculated mass, 14533.19) was detected (Figure S12). c The chemical structure of 4’ (left) and LC-ESI-MS (right, positive ion mode monitored at m/z 198.1) analysis of the reaction mixture using 4’ as the substrate (i) with LctC and (ii) without LctC. A peak with an m/z of 198.1130 (m/z, [M + H]+) corresponding to the exact mass of 6 (198.1125; m/z, [M + H]+) was observed in (i) (Fig. S13).

We next examined whether the adenylated Leu was transferred to the PCP domain. A truncated PCP domain was co-expressed with sfp in E. coli to obtain the holo form. The holo-PCP was reacted with the A domain, ATP, and Leu or OH-Leu. LC-ESI-MS analysis showed that only Leu was transferred to the PCP domain (Figs. 6b and S12). These results clearly demonstrated that Leu is the substrate of LctB (NRPS) and suggested that the hydroxyl group is introduced during a late step of the biosynthesis.

In vitro analysis of the ketosynthase-like cyclase LctC

To examine the last step of the enzymatic reaction of lactacystin biosynthesis, we investigated the function of the KS-like protein LctC, which has 66% identity with SalC responsible for biosynthesis of salinosporamide A8. SalC was reported to catalyze an intermolecular aldol reaction using ketone with concomitant off-loading of the cyclized product from the carrier protein8. Therefore, we hypothesized that LctC also catalyzes a similar reaction although LctC was suggested to use a substrate possessing an aldehyde moiety instead of the ketone moiety. To examine this hypothesis, we synthesized an N-acetyl cysteamine thioester of methylmalonyl semialdehyde-Leu (4’) (Fig. 6c) and incubated it with LctC. LC-MS analysis revealed that the cyclization reaction occurred with concomitant release of the product from PCP in the presence of LctC (Figs. 6c and S13). The proposed catalytic residues of SalC are conserved in LctC and the reaction mechanism would be similar to SalC although LctC uses an aldehyde as an electrophile (Fig. S14)8.

Conclusions

We conducted comprehensive in vivo and in vitro studies to elucidate the biosynthesis of lactacystin. We identified the biosynthetic gene cluster including genes encoding unique enzymes from the producer S. lactacystinicus NBRC 110082. By in vitro analysis, LctF was confirmed to be the first enzyme catalyzing the direct transfer of a formyl group to CoA from 10N-fTHF. LctA_AT1 specifically recognized formyl-CoA but not acetyl-CoA owing to its smaller substrate binding pocket. LctA_AT2 was suggested to accept methylmalonyl-CoA by bioinformatics analysis. The A domain of LctB recognized Leu but not OH-Leu and its activity was enhanced in the presence of the MbtH-like protein LctE. These building units were assembled by the LctA_KS and C domains to produce 4. LctC was demonstrated to catalyze the off-loading reaction besides the cyclization with a synthetic mimic substrate. The hydroxylation of Leu by LctD was thought to occur on PCP-tethered Leu. Overall, we have elucidated almost all steps of the biosynthesis of lactacystin by in vivo and in vitro studies. This knowledge will be useful for developing new lactacystin-related proteasome inhibitors by biosynthetic engineering.

Methods

Metabolite analysis of S. lactacystinicus WT and S. lactacystinicus ∆lctD strains

After preculture of cells in 10 mL TSB medium for 24 h at 30 °C, 1 mL preculture was transferred to baffled Erlenmeyer flasks containing 50 mL ISP3 medium and cultured for 6 days at 30 °C. After removal of cells by centrifugation, the broth was analyzed by LC-MS under the following conditions: column, Mightysil RP-18 GP Aqua column (150 mm × 2.0 mm, 3 μm, Kanto Chemical Co., Inc., Tokyo, Japan); column temperature, 40 °C; mobile phase, 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) in water (A) and 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile (B); flow rate, 0.2 mL min−1; gradient conditions, 5% B (0–10 min) and 5–95% B (10–30 min, linear gradient); injection volume, 10 µL. The HR-MS spectrum in Fig. S5 were recorded with Prominence HPLC instrument (Shimadzu Co.) equipped with LTQ Orbitrap XL (Thermo Fisher Scientific Co.) mass spectrometer.

Heterologous expression of the cluster

The DNA regions spanning lctT–lctF and lctA–lctF were PCR-amplified using primer pairs cluster_from_lctT_F/cluster_to_lctF_R and cluster_from_lctA_F/cluster_to_lctF_R, respectively (Table S2). PCR products were cloned into pWHM3 using XbaI and HindIII restriction sites to yield pWHM3-lctT-lctF and pWHM3-lctA-lctF. After introducing the plasmid into S. lividans TK23, each transformant was cultivated in 10 mL TSB for 1 day at 30 °C and then in 50 mL SK#2 for 6 days at 30 °C. Metabolites were analyzed with LC-MS as described above.

Preparation of 10-N-formyl THF

10N-fTHF was prepared with reported method with slight modifications20,21. Briefly, 10 mg of 5N-fTHF was dissolved in 1 M aq. 2-melcaptoethanol solution (630 µL) and the solution was adjusted to pH 1.5 with 1 M aq. HCl. The reaction was incubated on ice for 2 h. After neutralization by 1 M NaOH and addition of recombinant FolD (10 µM), the reaction was incubated at 37 °C for 0.5 h. All reactions were carried out under N2.

In vitro reaction of LctF

Freshly prepared 10N-fTHF (approximately 2 mM) was incubated with CoA (1 mM) and LctF (5 µM) in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) at 30 °C for 1 h. The reactions without either LctF or 10N-fTHF were also performed. The reaction was analyzed by LC-MS under following conditions: column, Mightysil RP-18 GP Aqua column (150 mm × 2.0 mm, 3 μm); flow rate, 0.2 mL min−1; column temperature, 40°C; mobile phase, (A) 10 mM aq. ammonium acetate buffer (pH 6.8) and (B) 10% (v/v) 10 mM aq. ammonium acetate buffer (pH 6.8) in MeOH; gradient conditions, 2% B (0–10 min), 2–98% B (10–15 min); detection, 260 nm and SQ Detector 2 mass spectrometer (ESI negative ion mode); injection volume, 10 µL.

In vitro reaction of (M-)LctA_AT1 and ACP1

Malonyl-CoA, acetyl-CoA, or freshly prepared formyl-CoA22,23,24 (500 µM each) was incubated with holo-ACP1 (100 µM) and either LctA_AT1 or M-LctA_AT1 (5 µM) in 100 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) at 30 °C for 1 h. The reaction was analyzed by LC-HR-MS under following conditions: column, Mightysil RP-18 GP Aqua column (150 mm × 2.0 mm, 3 μm); flow rate, 0.2 mL min−1; column temperature, 40 °C; mobile phase, (A) 0.1% TFA in water and (B) 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile; gradient conditions, 0% B (0–5 min), 0–95% B (5–30 min); detection, 280 nm and LTQ Orbitrap XL (positive ion mode); injection volume, 10 µL. The mass spectra of multiply charged ions were deconvoluted using the Mnova 14.2 software to provide molecular weight information of proteins.

Substrate specificity of LctA_AT1 and M-LctA_AT1

The formation of CoA was monitored by colorimetric assay of thiol group with 5,5ʹ-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB)33. For this purpose, LctA_AT1, M-LctA_AT1, and LctA_ACP1 were rebuffered with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) using Amicon Ultra (3 K, 0.5 mL, Millipore) before use. The reaction mixture (200 µL) containing malonyl-CoA, acetyl-CoA, or freshly prepared formyl-CoA (1 mM each), holo-ACP1 (200 µM), and LctA _AT1 or M-LctA_AT1 (1 µM) was incubated at 30 °C for 10 min. The reaction (100 µL) was quenched with acetonitrile (25 µL) and diluted with reaction buffer (600 µL). After the sample was mixed with 50 µL of DTNB solution (final 500 µM), absorption at 412 nm was measured with Spectrometer UV-1800 (Shimazu Co.).

In vitro reaction of LctB_A

The reaction mixture (100 µL) containing ATP (5 mM), MgCl2 (5 mM), hydroxylamine (32 mM), Leu or OH-Leu (2 mM), LctB_A (2 µM) and LctE (2 µM) was incubated at 30 °C for 30 min. The control reactions omitting LctB_A, amino acid, or LctE were also performed. After the reaction, 1 mL of 60% acetonitrile solution containing HCl (0.6 M) and Na2MoO4 (20 mM) was added to the reaction and incubated at room temperature for 5 min, followed by addition of 20 µL of bis(triphenylphosphoranylidene) ammnonium chloride (50 mM). The resultant mixture was centrifuged (13,000 × g, 4 °C, 20 min) and the supernatant was discarded. To the suspension of precipitate in 100 µL of acetonitrile was added 10 µL of reducing solution (60% acetonitrile, 2 M HCl, 440 mM ascorbic acid) and 600 µL of acetonitrile. The absorption at 620 nm was measured with Spectrometer UV-1800.

In vitro reaction of LctB_A and LctB_PCP

The reaction mixture (200 µL) containing ATP (2 mM), MgCl2 (2 mM), Leu or OH-Leu (1 mM), LctB_A (5 µM), LctE (5 µM), and holo-LctB_PCP (100 µM) was incubated at 30 °C for 60 min. The reaction was analyzed by LC-HR-MS using compact mass spectrometer under following conditions: column, Sunshell C8-30HT (150 mm × 2.1 mm, 3.4 µm, ChromaNikTechnologies Inc., Osaka, Japan); flow rate, 0.3 mL min−1; temperature, 30 °C; mobile phase, (A) 0.1% TFA in water and (B) 0.1% TFA in acetonitrile; gradient conditions, 0% B (0–5 min) and then 0–95% B (5–30 min); injection volume, 10 µL.

In vitro reaction of LctC

Reaction containing 4’ (1 mM) and LctC (5 µM) was incubated for 10 min at 30 °C. After the reaction was quenched with addition of MeOH, the sample was analyzed by LC-MS under following conditions: column, Mightysil RP-18 GP Aqua column (150 mm × 2.0 mm, 3 μm); flow rate, 0.2 mL min−1; column temperature, 40 °C; mobile phase, (A) water with 0.1% formic acid and (B) acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid; gradient conditions, 5% B (0–2 min), 5–90% B (2–12 min); positive ion mode; detection, 260 nm and Xevo TQD mass spectrometer (ESI positive ion mode); injection volume, 10 µL.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The nucleotide sequence of the lactacystin biosynthetic gene cluster was deposited in the DDBJ/GenBank database (accession no. LC830955). Copies of the NMR spectra for new compounds are provided in the Supplementary Data 1 file (pdf). Source data for LC-MS chromatograms and mass spectra are provided in Supplementary Data 2 file (MS Excel). All other data generated during this study are included in this manuscript and supplementary files.

References

Omura, S. et al. Structure of lactacystin, a new microbial metabolite which induces differentiation of neuroblastoma cells. J. Antibiot. 44, 117–118 (1991).

Tanaka, K. Role of proteasomes modified by interferon-γ in antigen processing. J. Leukoc. Biol. 56, 571–575 (1994).

Katagiri, M. et al. The neuritogenesis inducer lactacystin arrests cell cycle at both G0/G1 and G2 phases in neuro 2a cells. J. Antibiot. 48, 344–346 (1995).

Fenteany, G. et al. Inhibition of proteasome activities and subunit-specific amino-terminal threonine modification by lactacystin. Science 268, 726–731 (1995).

Groll, M. et al. Structure of 20S proteasome from yeast at 2.4Å resolution. Nature 386, 463–471 (1997).

Dick, L. R. et al. Mechanistic studies on the inactivation of the proteasome by lactacystin in cultured cells. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 182–188 (1997).

Corey, E. J. & Li, W. D. Total synthesis and biological activity of lactacystin, omuralide and analogs. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 47, 1–10 (1999).

Bauman, K. D. et al. Enzymatic assembly of the salinosporamide γ-lactam-β-lactone anticancer warhead. Nat. Chem. Biol. 18, 538–546 (2022).

Barra, L. et al. β-NAD as a building block in natural product biosynthesis. Nature 600, 754–758 (2021).

Muller, W. M. et al. In vitro biosynthesis of the prepeptide of Type-III lantibiotic labyrinthopeptin A2 including formation of a C–C bond as a post-translational modification. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 49, 2436–2440 (2010).

Wiebach, V. et al. The anti-staphylococcal lipolanthines are ribosomally synthesized lipopeptides. Nat. Chem. Biol. 14, 652–654 (2018).

Muliandi, A. et al. Biosynthesis of the 4-methyloxazoline-containing nonribosomal peptides, JBIR-34 and -35, in Streptomyces sp. Sp080513GE-23. Chem. Biol. 21, 923–934 (2014).

Bunno, R. et al. Aziridine formation by a FeII/α-ketoglutarate dependent oxygenase and 2-aminoisobutyrate biosynthesis in Fungi. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 15827–15831 (2021).

Nakagawa, A. et al. Biosynthesis of lactacystin. Origin of the carbons and stereospecific NMR assignment of the two diastereotopic methyl groups. Tetrahedron Lett. 35, 5009–5012 (1994).

Takahashi, S. et al. Biosynthesis of lactacystin. J. Antibiot. 48, 1015–1020 (1995).

Zhang, W. et al. Activation of the pacidamycin PacL adenylation domain by MbtH-Like proteins. Biochemistry 49, 9946–9947 (2010).

Miyanaga, A. et al. Protein–protein interactions in polyketide synthase–nonribosomal peptide synthetase hybrid assembly lines. Nat. Prod. Rep. 35, 1185–1209 (2018).

Minowa, Y. et al. Comprehensive analysis of distinctive polyketide and nonribosomal peptide structural motifs encoded in microbial genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 368, 1500–1517 (2007).

Blin, K. et al. AntiSMASH 7.0: new and improved predictions for detection, regulation, chemical structures and visualisation. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, W46–W50 (2023).

Rabinowitz, J. C. Preparation and properties of 5,10-methenyltetrahydrofolic acid and 10-formultetrahydrofolic acid. Methods Enzymol. 6, 814–815 (1963).

D’Ari, L. & Rabinowitz, J. C. Purification, characterization, cloning, and amino acid sequence of the bifunctional enzyme 5,10-methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase/5,10-methenyltetrahydrofolate cyclohydrolase from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 23953–23958 (1991).

Burgener, S. et al. Oxalyl-CoA decarboxylase enables nucleophilic one-carbon extension of aldehydes to chiral α-hydroxy acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 5526–5530 (2020).

Sly, W. S. & Stadtman, E. R. Formate metabolism: I. Formyl coenzyme A, an intermediate in the formate-dependent decomposition of acetyl phosphate in Clostridium kluyveri. J. Biol. Chem. 238, 2632–2638 (1963).

Jonsson, S. et al. Kinetic and mechanistic characterization of the formyl-CoA transferase from Oxalobacter formigenes. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 36003–36012 (2004).

Quadri, E. P. Characterization of Sfp, a Bacillus subtilis phosphopantetheinyl transferase for peptidyl carrier protein domains in peptide synthetases. Biochemistry 37, 1585–1595 (1998).

Mirdita, M. et al. ColabFold: making protein folding accessible to all. Nat. Methods 19, 679–682 (2022).

Eustaquio, A. S. et al. Biosynthesis of the salinosporamide A polyketide synthase substrate chloroethylmalonyl-coenzyme A from S-adenosyl-L-methionine. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 12295–12300 (2009).

Oefner, C. et al. Mapping the active site of Escherichia coli malonyl-CoA-acyl carrier protein transacylase (FabD) by protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 62, 613–618 (2006).

Serre, L. et al. The Escherichia coli malonyl-CoA:acyl carrier protein transacylase at 1.5-A resolution. Crystal structure of a fatty acid synthase component. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 12961–12964 (1995).

Rangan, V. S. & Smith, S. Alteration of the substrate specificity of the malonyl-CoA/acetyl-CoA:acyl carrier protein S-acyltransferase domain of the multifunctional fatty acid synthase by mutation of a single arginine residue. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 11975–11978 (1997).

Herbst, D. A. et al. Structural basis of the interaction of MbtH-like proteins, putative regulators of nonribosomal peptide biosynthesis, with adenylating enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 1991–2003 (2013).

Maruyama, C. et al. Colorimetric detection of the adenylation activity in nonribosomal peptide synthetases. Methods Mol. Biol. 1401, 77–84 (2016).

Ellman, G. L. Tissue sulfhydryl groups. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 82, 70–77 (1959).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported in part by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from JSPS (JP16H06452, JP18H03937 and JP22H04976 to T.D. and JP22H05130 and JP23H02145 to Y.O.) and The Uehara Memorial Foundation to T.T. We thank Robbie Lewis, MSc, from Edanz (https://jp.edanz.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.T. performed the experiments, data curation, and formal analysis, acquired funding, and wrote the manuscript; S.F. performed the experiments, data curation, and formal analysis; H.Y. performed the experiments, data curation, and formal analysis; C.M. performed the experiments, data curation and formal analysis; Y.H. performed data curation and formal analysis; Y.O. administrated the project and designed the experiments, performed data curation and formal analysis, acquired funding, and wrote the manuscript; T.D. conceived and supervised the project, performed data curation and formal analysis, acquired funding, and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsunoda, T., Furumura, S., Yamazaki, H. et al. Biosynthesis of lactacystin as a proteasome inhibitor. Commun Chem 8, 9 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01406-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01406-4