Abstract

Superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) aggregation is implicated in the development of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS). Despite knowledge of the role of SOD1 aggregation, the mechanistic understanding remains elusive. Our investigation aimed to unravel the complex steps involved in SOD1 aggregation associated with ALS. Therefore, we probed the aggregation using ThT fluorescence, size-exclusion chromatography, and surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS). The removal of metal ions and disulfide bonds resulted in the dimers rapidly first converting to an extended monomers then coming together slowly to form non-native dimers. The rapid onset of oligomerization happens above critical non-native dimer concentration. Structural features of oligomer was obtained through SERS. The kinetic data supported a fragmentation-dominant mechanism for the fibril formation. Quercetin acts as inhibitor by delaying the formation of non-native dimer and soluble oligomers by decreasing the elongation rate. Thus, results provide significant insights into the critical steps in oligomer formation and their structure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The complexity of the mechanism of protein aggregation continues to intrigue chemists and biologists alike particularly because certain proteins can have similar secondary structures but can have completely different aggregation mechanism1,2,3. Amyloid fibrils are a class of protein aggregates associated with neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and ALS, so the protein aggregations are currently the focus of extensive mechanistic research4,5,6. ALS is a catastrophic neurodegenerative disease responsible for the degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons, affecting muscular functions and ultimately leading to death within a few years from the onset of the disease. Sporadic (sALS) and familial (fALS) are the two types of ALS constituting 90% and 10% of cases, respectively. The origin of sALS is largely unknown, whereas familial cases originate from family history7,8. Superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) is a metalloenzyme that catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide anion radical into hydrogen peroxide and an oxygen molecule and is majorly present in the cytosol of the cell. It is a 32 kDa homodimeric protein with one copper ion, one zinc ion, and one intramolecular disulfide bond in each subunit9,10,11. For around one-fourth cases of fALS, aggregation of mutant SOD1 is considered highly liable. The link between ALS and wild-type (WT) SOD1 is quite contentious; however, in both fALS and sALS cases, the SOD1 immunoreactive aggregates were observed12,13,14. The fibrillation kinetics of SOD1 in vitro accurately mimic disease progression in transgenic mice15 as shown by Lang et al. Oliveberg et al. and Dokholyan et al. have made significant efforts to shed light on SOD1 misfolding and aggregation15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31.

SOD1 fibrillation can also be induced in vitro by removing metal ions, disrupting disulfide bonds, or applying mechanical agitation. Even a small amount of misfolded protein in the motor areas is sufficient to cause cytotoxicity21 and is often associated with chelation of Zn2+. Norland et al. investigated the influence of zinc ions on SOD1 folding and noted that without zinc ions, SOD1 undergoes local unfolding and exhibits structural properties similar to ALS-associated mutations16. Furthermore, the misfolded apo species serves as the precursor for SOD1 aggregation, either through exposure of hydrophobic patches, local unfolding of the central β-barrel, polymerization via long active site loops, oxidative crosslinking via Cys6-Cys111, or a combination of mechanisms24. Some studies propose that the apo SOD1 monomer must fully unfold to aggregate24, while others suggest that the misfolded monomer is the primary precursor for SOD1 aggregation8,32,33,34,35. After translation from the ribosome, SOD1 maturation occurs by incorporating zinc ion followed by copper insertion and disulfide bond formation to obtain WT SOD1 dimer. These maturation events are critical as the absence of these leads to SOD1 misfolding and aggregation and can be the target for potential therapeutic agents7,32,33,34,35. The SOD1 aggregation is dynamic, and therefore, suitable tools and techniques are required to comprehensively probe the structural underpinnings of the aggregates.

Although the link between ALS and the aggregation of superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) is very well known36,37,38, the initial events leading to oligomer formation, the role of metal ions and their interplay with subsequent aggregation of SOD1 is not fully elucidated. Herein, we have probed the dynamics of aggregation of SOD1, from dimer to monomer formation and subsequent formation of oligomers through the highly sensitive technique of surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) combined with SEC and biophysical studies. The plasmonic substrates made up of gold or silver nanostructures can enhance the Raman scattering cross-section greatly, specifically of biomolecules which are prone to photodegradation or quenching and can tolerate lower laser powers39,40. The salient point of SERS is the ability to probe biological systems without any exogenous optical labels with extremely low detection limits, and multiplexing capabilities, making it a promising analytical technique for biological systems39,41,42,43. It is particularly useful in cases where the structure of the protein is not available in form of crystal structure or nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) data, which is the case for many intermediates in the protein aggregation process44,45,46. Also, being an extremely sensitive technique with sensitivity in single-molecule level, SERS can detect very low quantities of intermediates that can be outside the detection limits of other popularly used spectroscopic tools such as circular dichroism and NMR. In this study, we have employed SERS to probe the structure of SOD1 oligomers, whose poor signals due to low concentration have been enhanced by the localized electromagnetic field of plasmonic silver nanoparticles. The dimer or monomer formation in SOD1 is strongly correlated to the local structural changes of the protein, which could be effectively detected through SERS, along with the structural changes in monomer that act as the precursor for the non-native dimer leading to oligomer formation.

The protein’s aggregation eventually leads to the formation of toxic species which dictates the progression of neurodegenerative diseases3,47,48,49,50,51,52,53. A comprehensive understanding of the inhibitory mechanism holds the potential to aid in the rational design of potent small-molecule inhibitors. Quercetin, a phytochemical flavonoid, has been known to impede SOD1 aggregation with remarkable efficiency54,55. We have earlier reported that the fibrils formed with quercetin exhibited reduced toxicity when contrasted with those formed in the absence of quercetin54. Nevertheless, the intricate mechanistic underpinnings of its inhibitory action remain inadequately characterized. Here, we seek to uncover another crucial piece of the puzzle that will advance our comprehension of SOD1 aggregation in the absence and presence of an inhibitor. This mechanism was also validated through the comparative SERS study of the oligomer versus the native dimer, highlighting the importance of the cysteine and the interfacial residues which migrate to the core on oligomerization. The study also predicts a fragmentation-dominant nucleation mechanism which leads to the exponential increase in fibril formation. Firstly, the dimer rapidly converts into a monomer following a first-order reaction, followed by the formation of the extended monomers. These associations of monomeric units lead to the formation of non-native dimers. Quercetin was found to inhibit the elongation of the oligomer, thus inhibiting the fibril assembly. This provides a rubric for development of suitable therapeutic options for slowing the progression of ALS.

Results and discussion

SOD1 is a homodimer, where the dimer is held together with hydrophobic contacts, and this structural feature imparts stability to the protein11. The metal binding to the protein dimer, the bridging between them through a histidine side chain and other secondary hydrogen bond links impart additional stability to metalloenzymes such as SOD17,11. In this study we have probed the mechanism of aggregation of SOD1 with respect to the disruption of dimer structure brought through disruption of disulfide bonds and removal of metal ions, and the events during aggregation in the presence and absence of quercetin.

DTT and EDTA-induced aggregation of SOD1: aggregation kinetics using SEC during initial phase

Determining the presence of different soluble species in the aggregating mixture can provide insights into complex mechanism of aggregation. The time evolution of soluble species formed was seen through SEC at regular intervals. SOD1 was treated with EDTA to chelate out the metal ion, and incubated with DTT to cleave the disulfide bonds. Just after addition, the dimer was predominantly present in the sample and negligible amount of monomer can be observed at t = 0 min. The dimer and monomer were eluted at 15.38 ml and 16.12 ml, respectively (Fig. 1a). SEC profiles were also obtained at different time intervals (t = 10, 15, and 30 min) after addition of EDTA and DTT. The concentration of dimer decreased progressively due to its conversion to monomer. In just 30 min time, the dimer was completely converted into monomer. The dimer and monomer ratios present at different times were calculated from the fitted area under the curve of the SEC data obtained after deconvolution. The data could be fitted with first-order reaction equation (Fig. 1b), and the value of rate constant (k1) was found to be \(3.69\times {10}^{-2}\pm 2.7\times {10}^{-3}{s}^{-1}\). This shows that, during the initial stage of aggregation, dimer-to-monomer conversion was a key event and was particularly rapid in comparison to time scale of aggregation. This fast dimer to monomer conversion at the initial stages of aggregation followed first-order kinetics.

a Size exclusion chromatogram of EDTA and DTT-treated SOD1(30 μM) at different times (t = 10, 15, and 30 min), b fitting of decrease in dimer area with for first order (Eq. 6), c the time evolution of soluble species observed between 6 and 18 ml, d at lower elution volume (6–13 ml).

Oligomer formation during growth and saturation phases

The SEC data shows the presence of both dimer and monomer during initial hours (Fig. 2(a)). However, after 4 h, a new peak emerged between dimer and monomer which may correspond to misfolded or unfolded monomer, also referred to as “extended monomer peak” (Fig. 2b). A slight left-side shift in the elution volume of this extended monomer peak is most probably due to the misfolding of native monomer upon metal ions and disulfide bond removal which continued till 8 h (Fig. 2(c)). Previous studies have also suggested that precursor for SOD1 amyloid formation can be either an unfolded monomer or a misfolded monomer24,56,57, but the ambiguity still remains. Modified SDS-PAGE58 confirms that the peak is a monomer peak whereas circular dichroism (CD) spectra revealed increased random coil content compared to holo-SOD1, indicating misfolding (Supplementary Fig. 1)59. Interestingly, at the same time point, the emergence of one broad peak occurs between 14 and 15 ml, near native dimer peak, which can be assigned to the formation of a non-native dimer60. After 12 h, the intensity of extended monomer peak decreased further while the intensity of the non-native dimer peak increased. At 16 h, the intensity of the non-native dimer peak reached its maximum and an oligomer peak emerged at a lower elution volume (~11 ml). There is a rapid formation of the oligomer formation after 16 h, suggesting that dimer has achieved critical concentration to serve as nucleus in the fibrillation of SOD1. The amount of oligomer kept on increasing till 28 h (Fig. 1c). At this point, the soluble oligomer rapidly disappeared due to their complete incorporation into insoluble amyloid fibrils. The slow rate of monomer to non-native dimer conversion was validated through another SEC experiment where the incubated protein is sampled after every hour up to 6 h. The non-native monomer concentration obtained from deconvolution of data was fitted with various kinetic models, including zero-order, first-order, and second-order reactions, but the best fit was obtained for second-order reaction which suggests that the conversion of non-native monomer to non-native dimer follows second order kinetics and the size of nucleus is 2 (Eq. 7) (Fig. 2i and j).

a–h Time evolution of soluble species at higher elution volume (13–18 ml), i Size exclusion chromatogram of EDTA and DTT-treated SOD1 (30 μM) at different times, j fitting of ratio of monomer area at t = 0 over t = 0–6 with second-order equation (Eq. 7).

Probing the structure of the SOD1 native dimer and oligomer using SERS

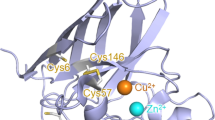

Raman and CD spectra of oligomer samples suffered from extremely low SNR (signal-to-noise ratio) to enable any kind of analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2). Therefore, we have done an extensive analysis of the SERS spectra of protein and oligomer to understand the orientation with respect to the nanoparticle surface. Citrate-capped silver nanoparticles were used for obtaining the SERS spectra of native proteins and oligomers. Citrate is a weak capping agent and is a better choice for obtaining SERS of proteins due to easy displacement from the surface, and non-interference with the protein spectra61,62. The colloidal silver nanoparticle was also ‘activated’ or partially aggregated to increase the binding of protein which further enhanced the SERS signals. The SOD1 structure consists of positively and negatively charged surface domains as seen in Fig. 3a whereas nanoparticles are negatively charged. The protein-nanoparticle binding was facilitated through electrostatic attractions, where the negatively charged nanoparticle interacts with the positively charged domain of the protein (Supplementary Figs. 3–4). This is of particular significance as the electromagnetic field in the vicinity of the plasmonic nanoparticles decays exponentially with distance63,64 and therefore, enhances the SERS signals65. This also causes the SERS spectra to be different from the normal lyophilized protein Raman spectra (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Table 1)66, where the former is highly surface-selective. In the case of SOD1 protein, domain containing maximum positive charge residues has mostly beta-sheets and some alpha helix. (Fig. 3a). Since the enhancement of various modes depends on the SERS selection rules, the conformation and orientation of the molecule with respect to the nanoparticle surface is important for various mode assignment63,65. The SERS spectra of SOD1 are shown in Fig. 3(c) and the SERS signals were assigned (Supplementary Table 2). The SOD1 protein Raman peak at 1580 and 1169 cm−1 can be assigned as the phenyl C-stretching (ν8a) and combination of in-plane C-H bending (ν9a) with ring stretching respectively, of the phenylalanine amino acid65. Interestingly the Phe peak at 1000 cm−1, which arises due to the aromatic ring, is not observed in the spectra of protein, which is consistent with the fact that no surface Phe residues are present in the protein. Glutamic acid and aspartic acid are the two amino acids that have acidic side chains, and SOD1 showed peaks which could be assigned to the stretching vibration of C–COO− as a doublet at 909 and 937 cm−1. The various amide bands arise due to vibration in the peptide chain and are important markers of the protein secondary structure. The combination mode containing out-of-phase CN stretching vibration, CCN deformation, and N-H bending in addition to CO stretching vibration is the amide I band65,67. The combination of the CO in-plane bend, the CC and NC stretching vibrations, the NH in-plane bend, and the CN stretching vibrations form the amide II mode65. In a typical Raman, the amide II band is a Raman inactive mode. But in the case of SERS, the surface selection rule is modified, which makes the amide II band Raman active65,68. The amide III band is the combination of the NH bending and CN stretching vibration with the CO in-plane bending and the CC stretching vibrations. In SOD1 SERS spectra, the 1613 cm−1 peak was observed and can be assigned as the amide I band65,68. Each monomer of SOD1 protein is a β-barrel made up of eight anti-parallel beta-sheets69. Therefore, the amide I band can be assigned to an anti-parallel β-sheet, whose band location in Raman spectra is close to 1620 cm−1 65,67,70,71. This secondary structure region further overlaps with the positively charged domain further validating the binding region of the protein to the nanoparticle surface (Fig. 3a). The amide III band is typically detected in the 1200–1400 cm−1 range, where there is interference from other bands too. This band was observed at 1290 cm−1 in both SOD1 and the oligomer. Amide II band often appears between 1510 to 1530 cm−1, and the peak at 1531 cm−1 in the spectra of SOD1 is assigned as the amide II band. In the SOD1 protein SERS spectra, peaks corresponding to the tryptophan residues and C-S vibrations could not be observed. This was probably because all the cysteine and tryptophan residues were oriented away from the nanoparticle surface.

a Represents the SOD1 (PDB ID: IHL5100) positive charge residues responsible for the electrostatic attractions with the silver nanoparticle and surface charge (blue for positive, red for negative) give an idea about possible attachment orientation of SOD1 protein, (R = Arginine, K = Lysine, H = Histidine) b give idea about possible attachment orientation of oligomer with the silver nanoparticle, c SERS spectra of protein (black), oligomer (red) and oligomer formed in presence of quercetin (blue)65,85,90,91,101,102.

The SERS spectra of the oligomer were obtained in the same manner as the SOD1 protein to probe the structural change of protein on oligomerization. As reported in the literature, the aggregate of SOD1 contains some protease-resistant residues in the core regions, including 1-30, 90-120, and 135-15372. Therefore, all these residues are supposed to be present in the core structure of oligomer. SOD1 protein contains four cysteine residues Cys6, Cys57, Cys111, and Cys146 and on oligomer formation, out of four cysteines, only Cys57 is not among protease resistant residues and hence should not be involved in the core structure of the oligomers73. Since the spectra of both protein and oligomer show significant similarity, the interaction of protein and oligomer with the nanoparticle involves some common residues. However, many changes in peak positions were also observed. In SERS spectra of oligomer, a C-S stretching peak at 667 cm−1 was observed which was absent in native protein spectra. This implies that on oligomerization, Cys57 residue comes in the proximity of the nanoparticle surface, thus providing a structural clue about the oligomer formation. (Supplementary Fig. 6) Another difference we observe between SOD1 native and oligomeric samples is the emergence of a 1697 cm−1 peak in the oligomer which can be assigned to a random coil structure or simply the carboxyl stretching mode, particularly when attached to a solid nanoparticle surface as the random coil structures can equilibrate with antiparallel beta-sheet type of structures74,75. So, in the case of oligomer, the nanoparticles may interact with residues having random coil structure in 56 to 82 region, consisting of Cys 57 and residues from Zn binding loop. It is consistent with the flexible region in the fibril structure73. The entire region has 7 positive charge residues and 3 negatively charged residues. Out of this region, residues 56 to 75 have 5 positively charged residues with no negatively charged ones. The Electrostatics loop region can be ruled out since it is no longer a flexible region in fibril and consists of β-barrel 11 and 12 in fibril. The electrostatic loop region has 4 positively charged residues and equal number of negatively charged residues, with negatively charged residues concentrated in short region from 124 D to 133 E, making a negative patch as shown in Fig. 2f from reference73. Thus, SERS study has provided the subtle differences between the structure of native protein and the oligomer.

Aggregation kinetics of SOD1 at different protein concentrations

To understand the mechanism of aggregation, the kinetics of aggregation of SOD1 was also studied by monitoring the ThT fluorescence with time (Fig. 4a). The aggregation kinetics showed a sigmoidal profile with a distinct lag phase which is the characteristic of nucleus formation. To understand the possible role of primary and secondary nucleation, seeding experiment was carried out by adding seeds at the beginning of the aggregation kinetics. On addition, lag time completely vanished, implying the importance of nucleus formation in lag phase of aggregation as shown in Fig. 4b. The values of lag time and aggregation rate are given in Supplementary Table 3, the lag time of EDTA and DTT-treated SOD1 varies between 10–12 h as calculated using Eq. 8. The aggregation rate of SOD1 increased linearly upon increasing the protein concentration, as suggested by the log kapp vs log protein concentration plot (Fig. 4c).

a Aggregation of different concentrations of SOD1 in 2 mM EDTA and 80 mM DTT at 37 °C, 25 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4, b EDTA and DTT induced fibrillation of SOD1 alone and in the presence of seeds. c log-log plot of aggregation rate vs. SOD1 concentration. d–h Different concentrations of SOD1 aggregation early time rise of the ThT fluorescence intensity fits well with the relation Δ = A(cosh(bt)-1) referring to the presence of secondary pathways. i Calculation of the secondary nucleus size from the parameter κ.

The analysis of the kinetic profiles of protein aggregation from the ThT fluorescence data has provided valuable insights into the underlying mechanisms of the process. In the case of SOD1 aggregation, the initial stages exhibited rapid exponential growth, fitting well with the equation Δ = A(coshBt−1) for the early time rise of the aggregation (Fig. 4d–h). This sudden growth pattern in the kinetic curve suggests the involvement of secondary pathways in the system76, where existing aggregates play a role in facilitating the formation of new aggregates. These secondary pathways may include fragmentation, heterogeneous nucleation, and branching, have been extensively studied77. The control of primary and secondary pathways during aggregation is influenced by two key parameters, λ and κ. If the rate constants for the formation of the primary nucleus and elongation are kn and k+, respectively, then λ is given by \(\lambda =\sqrt{2{k}_{+}{k}_{n}{m}_{0}^{{n}_{c}}}\), where nc is the size of the critical nucleus the order of the reaction and m0 is the initial concentration of the monomer77,78. SOD1 protein exists as a dimer so the concentration of monomer was obtained from Eq. (1). The value of dissociation constant KD lies in the micromolar range, therefore, the KD was taken in the range \(1\times {10}^{-6}-1\times {10}^{-9}{{{\rm{M}}}}\)28.

Where,

\({m}_{0}\) = Concentration of monomer

\({C}_{{dimer}}\) = Concentration of dimer

\({K}_{D}\) = Dissociation constant of dimer into monomer

As suggested by Ferrone76, the reaction order of the secondary processes can be determined by linear fit of the logarithmic values of κ against the logarithmic monomer concentration. The value of κ is obtained by fitting the early time data to Eq. 2, where Mt is total fibril at time t77,79.

The log-log plot of κ vs. SOD1 protein concentration was constructed in Fig. 4i, which was linear with a positive slope equal to 0.32. If secondary pathways exist as monomer-independent fragmentation, then κ is given \(\kappa =\sqrt{2{k}_{+}{k}_{-}{m}_{0}^{{n}_{2}+1}}\) where n2 and k− are the reaction order and the rate constant for the secondary processes, respectively77. Equating the slope equal to \(\frac{{n}_{2}+1}{4}\) gave n2 equal to 0.25, which can be taken as zero, suggesting fragmentation as a secondary pathway in SOD1 aggregation77,78,80. It is consistent with Lang et al. observation for apo SOD1 monomer under denaturation conditions15,24.

The fragmentation mechanism of aggregation of SOD1 was validated using Amylofit81. The global fitting of the experimental data is performed with different aggregation models such that the free-fitting parameters (rate constants and reaction orders) come out to be equal. The rate constants and reaction orders were also obtained from the fitting parameters. The un-normalized aggregation kinetics data of SOD1 fits well with the fragmentation dominant mechanism. The fitting of data with different models is shown in Fig. 5, and the obtained parameters for the fragmentation dominant mechanism are given in Supplementary Table 4. The reaction order for the primary nucleation nc is 2, suggesting the formation of dimeric nucleus. The data also fits well with the fragmentation and secondary nucleation model but in that case, unrealistic values of n2 (~15) were obtained, hence, the possibility is discarded for this model.

Reaction order can also be obtained from the scaling law according to which half-time of the aggregation reaction is dependent upon the initial monomer concentration as a power law80,81,82,83, as given Eq. 3.

Where γ is the scaling exponent. The log-log plot of half-time versus monomer concentration, the scaling exponent obtained is equal to 0.55 (Supplementary Fig. 7). The value of the scaling exponent further confirms the dominance of the fragmentation mechanism.

Effect of Quercetin on the aggregation of SOD1 and the formation of non-native dimer

Quercetin is a potent aggregation inhibitor and demonstrates a dose-dependent capacity to hinder SOD1 aggregation, similar to previous observations from our laboratory54,55. The mechanism of SOD1 inhibition by quercetin can throw light into the protein aggregation mechanism itself through precise molecular interactions. We have investigated the effect of quercetin during the non-native dimer formation and subsequent conversion to oligomer, which are the two key events from where the aggregation is induced in SOD1.

The effect of quercetin on extent of protein unfolding and exposure of hydrophobic patches can be quickly tested through ANS dye. In the absence of quercetin, the change in hydrophobicity was monitored as a function of time, a blue shift in wavelength maximum and enhanced ANS intensity was observed after 15 min (Fig. 6a). After 1 h, the ANS showed the maximum intensity and subsequently, no change in the intensity and emission wavelength took place, indicating that all the hydrophobic patches became exposed within first hour of aggregation and no further change happened after this. In the presence of quercetin, the ANS intensity again increased, however, increase was half of the increase in absence of quercetin. Thus, quercetin significantly reduced the exposure of hydrophobic patch of the protein (Fig. 6(b)) indicating that it can have aggregation inhibitory action which was further probed through SEC, kinetics experiments and SERS.

In order to probe the inhibition mechanism of quercetin further, SEC experiments were carried out to monitor the events. In the presence of quercetin (50 μM), the conversion of native dimer to monomer (Fig. 7a) followed first-order kinetics with observed rate constant of 1.26 × 10−2 ± 7.55 × 10−4 s−1(Fig. 7b) which is one-third of the rate constant observed in the absence of quercetin. The formation of non-native dimer also decreased in the presence of quercetin. Additionally, the peak corresponding to the monomer did not exhibit a significant leftward shift in elution volume indicating the formation of a more compact monomer (Fig. 7c), consistent with smaller increase in ANS intensity. During the lag time, no significant formation of non-native dimer and no oligomer formation was observed suggesting that quercetin delays or halts the aggregation.

a Size exclusion chromatogram of EDTA and DTT-treated SOD1 30 μM in the presence of 50 µM quercetin at different times, b fitting of decrease in dimer area with first-order equation, c SEC at different times to monitor the formation of different soluble species formed during the SOD1 aggregation in the presence of quercetin (50 μM).

The ThT aggregation experiments were performed to study SOD1 aggregation in the presence of quercetin (Fig. 8a). When quercetin is introduced during the initial stages of aggregation, an elongation of the lag phase and a reduction in the aggregation rate are observed (Fig. 8b).

a Aggregation kinetics of 30 μM SOD1 in the presence of different concentrations of quercetin (10, 30, 40, and 50 μM), b plot of lag time and kapp versus quercetin concentration, c Aggregation of different concentrations (20, 30, 40, 50 µM) SOD1 protein in the presence of 25 µM quercetin, d log-log plot of half time versus protein concentration.

Aggregation of different concentrations of SOD1 protein (20, 30, 40, 50 µM) was also carried out in the presence of 25 µM quercetin (Fig. 8c). The scaling exponent γ was calculated by the slope of the log-log plot of half-time versus protein concentration (Fig. 8d). The scaling exponent was observed to be 0.25 (this value was 0.5 without quercetin) suggesting that aggregation of SOD1 in the presence of quercetin can no longer be represented by fragmentation dominant pathway.

Earlier, it was observed that in the presence of quercetin, some monomers were observed at the end of aggregation. Upon the addition of quercetin to the pre-formed fibril, it partially dissociated into monomers54,55. These observations also highlight the depolymerization potential of quercetin55,84. The kinetics data in the presence of a different concentration of quercetin was fitted with the below-modified Eq. (4) which takes depolymerization of aggregates into account79,80,82.

Where M(t), \({m}_{{tot}}\) and f represent the amount of aggregate formed at time t, total monomer, and parameter incorporating the rate of depolymerization. f is given by the following Eq. (5) where \({k}_{{off}}\) is the rate constant for depolymerization, and \({\lambda }^{{\prime} }\) and \({\kappa }^{{\prime} }\) are the modified rate parameters due to the depolymerization in the presence of quercetin.

In the presence of quercetin, the values of both primary and secondary parameters decreased, but the percentage decrease was greater in the primary rate parameter. λ depends on k+ and kn, and κ depends on k+ and k- for fragmentation and k+ and k2 for secondary nucleation, therefore, quercetin most prominently affected k+ and decreased both λ and κ (Supplementary Table 5). Thus, quercetin decreases the rate of elongation to inhibit the SOD1 aggregation. In brief, the analysis of SEC and ThT kinetic profiles show the following about the inhibitory action of quercetin: (i) it slows conversion of SOD1 native dimer to monomer, (ii) the monomer formed is more compact and less unfolded, (iii) smaller concentration of nucleus formation from this monomer leading to less oligomer formation (v) fibrils do not not fragment leading to overall significantly lesser amount of SOD1 aggregates.

The decrease in the ThT intensity may be due to competition between ThT and quercetin. To assess such possibility, concentration of ThT added to aggregate sample was varied while keeping quercetin constant. There was no change in ThT fluorescence on the increase in ThT implying that ThT and quercetin do not have same binding site on fibril and hence do not compete (Supplementary Fig. 8).

TEM images were also obtained to see the morphology of aggregate formed in the presence and absence of quercetin (Supplementary Fig. 9). The images of fibril of SOD1 alone suggest that smaller fibrils are formed whereas, in the presence of quercetin, almost no fibrils are observed under similar condition as control.

To demonstrate the inhibition effect of quercetin on seeded aggregation, we conducted experiments by adding seeds at the start with varying concentrations of quercetin (Supplementary Fig. 10). The quercetin does indeed slow down the effect of seeding of aggregation by preformed fibrils suggesting that elongation and/or fragmentation gets affected in the presence of quercetin.

SERS insights into SOD1 aggregation and its inhibition by quercetin

The Raman fingerprint region between 400 cm−1 and 1700 cm−1 contains molecular information regarding the protein's secondary and tertiary structure as well as the amino acid residues and the aliphatic side chains85. The SERS spectral region was plotted for SOD1, oligomer, and the oligomer in the presence of quercetin, and principal component analysis was performed on the spectroscopic data. PCA is a multivariate method and is used for dimensionality reduction and feature extraction in data analysis86. This allows us to visualize, and differentiate the SERS spectra, which would otherwise be difficult to categorize or classify86,87,88,89.

The SERS spectra of the native dimer of SOD1 and the oligomeric protein show common spectral features, particularly in aliphatic and aromatic amino acid regions. However, the major difference arises in the amide regions, where an extra mode at around 1697 cm−1 is present which can be assigned to the random coil configuration of the protein90. This certainly points to the partially uncoiled state of the extended monomer which acquires a structured state as the fibrils stack against each other. This is also evident from a band in the amide I region at around 1613 cm−1 which can be assigned to antiparallel β-sheet65. Although the differences in SERS spectra of protein and oligomers are not very prominent through the naked eye, they can be picked up efficiently through the PCA analysis. Thus, PCA is applied to the entire fingerprint spectral region (400–1700 cm−1). The protein and oligomer clusters are well separated by PC1 component (Fig. 9a). The PC1 and PC2 loading plots from 400–1700 cm−1 show the differences in the spectra of the native dimer and the oligomer species (Fig. 9c). A positive peak of PC1 loading along with negative peaks of PC2 corresponds mostly to the oligomer (in red) whereas negative peaks PC1 with positive peak of PC2 corresponds mostly to the protein (in black). A positive peak in PC1 around 1697 cm−1 with negative peaks in PC2 corresponds to the regions of random coils. Other prominent changes can be seen at around 1270, 1400, 1470, 1530, and 1590 cm−1 in oligomer. Changes at wavenumbers, such as 1530 cm−1 and 1270 cm−1 correspond to the changes in the amide II and amide III region respectively91.

PCA scatter plot for the first two principal components (PC1 and PC2) for (a) protein and oligomer, (b) oligomer and oligomer in presence of quercetin. Each dot represents one spectrum (black for protein, red for oligomer, green for oligomer in presence of quercetin), (c) PC loading plot for PC1 and PC2 for protein and oligomer, (d) PC loading plot for PC1 and PC2 for oligomer and oligomer formed in presence of quercetin.

In summary, the similarity of SERS for both oligomer and protein dimer suggests that oligomer has similar surface characteristics to bind with nanoparticles but PCA suggests significant changes in the amide II, amide III, and random coils regions. This implies that the nanoparticle-protein attachment has not much changed, but rather there is a conformation change in the oligomer species which now contains more random coil components. Thus, these results directly support the formation of oligomers from extended monomers and non-native dimers.

The scatter plot for protein oligomer and the oligomer in the presence of quercetin55 shows clusters that are well separated by the PC1 component (Fig. 9b). Particularly, the presence of a peak at 1697 cm−1 with positive PC1 and negative PC2 suggests that the oligomer formed in the presence of quercetin has more random coil (Fig. 9d). Similar peaks at 1611 cm−1 and 1643 cm−1 show major changes in the amide I region further pointing towards structural changes. Other changes at around 1365, 1170, 909, and 750 cm−1 were also observed corresponding to the changes in the carboxylate and Phenylalanine group. The scatter plot figure (Supplementary Fig. 11) shows a score plot based on two components PC1 and PC2, and these two components account for 36.6% of the total variance.

The scatter plot for protein and its oligomer formed in the presence and absence of quercetin shows that the protein and oligomer clusters are separated by the PC1 component and oligomer in the presence and absence of quercetin is separated by the PC2 component (Supplementary Fig. 11). Thus the PCA analysis elucidates the structural aspects of the inhibitory potential of quercetin towards fibril aggregation. This inhibitory mechanism seems to be coming into play through the structural changes in the SOD1 protein in the presence of quercetin.

Conclusions

In this study, we tried to decipher the steps involved in the complex mechanism of aggregation of SOD1 linked to ALS in the absence and presence of quercetin. Proteins aggregate mainly through nucleation-dependent or independent pathways92,93,94. The aggregation of SOD1 follows a sigmoidal profile which became concave upon the addition of pre-formed fibrils or seeds, implying the importance of nucleation event. The early time rise of SOD1 aggregation, log-log plot of κ vs. protein concentration, and log-log plot of half-time vs. protein concentration suggests that the aggregation mechanism is fragmentation dominant. The global fitting of kinetics data with Amylofit also suggests fragmentation dominant mechanism. The SERS studies also support the formation of oligomers from extended monomers and non-native dimers. From the PC analysis of the SERS spectra, it was seen that the oligomer has similar structure and surface characteristics, but there is a change in the secondary structure where the some of the beta sheets have converted into random coils. While in the presence of quercetin, the aggregation mechanism becomes more complex. Monitoring the evolution of soluble species with time using size exclusion chromatography predicted the steps in the aggregation process (Fig. 10). After removal of metal ions and disulfide bond from native protein (dimer), dimer rapidly converts into monomer within an hour and the conversion is first-order reaction. In the second step, monomer takes extended form which has a tendency to associate and form non-native dimer. The decrease in monomer concentration follows second-order kinetics. The formation of non-native dimer is also supported by the results obtained from Amylofit. Once the critical concentration is reached, oligomerization process starts expeditiously. Quercetin inhibits the aggregation of SOD1 by moderately affecting the dimer-to-monomer conversion during initial hours, by delaying the formation of non-native dimer and soluble oligomers and by decreasing the rate of elongation. In a nutshell, EDTA and DTT-induced aggregation SOD1 follows a fragmentation dominant mechanism in which the formation of non-native dimer serves as rate-limiting step. Quercetin inhibited the aggregation of SOD1 by affecting the crucial steps involved in the aggregation. Additional studies need to be done to characterize the different species formed during the aggregation process. Further, based on our proposed mechanism, inhibitors can be designed to suppress the aggregation of ALS causing SOD1, and the mechanism can be elucidated through a combination of SERS and SEC.

After removal of metal ions and disulfide bond from native protein dimer rapidly converts into monomer which is first-order reaction. Then monomer takes extended form which has tendency to form non-native dimers which act as nucleus. Once the critical concentration of nucleus is reached, oligomerization process starts expeditiously. Then larger oligomers fragmented and act as seeds for further aggregation. Overall, SOD1 aggregation follows a fragmentation-dominant mechanism in which the formation of non-native dimer serves as rate-limiting step.

Methods

Materials

Thioflavin T (ThT), 8-anilinonaphthalene-1-sulfonic acid (ANS), isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG), Luria broth (LB), 1,4-dithiothreitol (DTT), imidazole were purchased from Sisco Research Laboratories (SRL), India. Quercetin, Tris buffer, phosphate buffer, copper sulfate, zinc sulfate, sodium chloride, silver nitrate, sodium citrate, sodium acetate, ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA) were obtained from Merck. Ampicillin was purchased from Biobasic and Ni-NTA resin was obtained from Qiagen.

ThT-based SOD1 aggregation kinetics assay in the absence and presence of quercetin

SOD1 was expressed and purified according to the earlier protocol95,96. The purity of the protein was checked through SDS-PAGE. The concentration of the obtained protein was measured by monitoring the absorbance at 280 nm using the molar extinction coefficient value of 10800 M−1 cm−1 96,97. Aggregation kinetics of SOD1 was monitored at five different concentrations: 15 μM, 20 μM, 25 μM, 30 μM, and 35 μM of the protein. For every aggregation reaction, five replicates were set up. The aggregation of protein was initiated by adding 2 mM EDTA and 80 mM DTT at a constant shaking of 420 RPM and under physiological conditions (37 °C, 25 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4). The aggregation kinetics was recorded by adding 40 μM ThT, keeping the excitation wavelength at 446 nm and the emission wavelength at 482 nm. The slit-width was kept at 5 nm, and the readings were taken after an interval of every 15 min. All ThT non-normalized raw data are shown in Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13. For the seeding experiment, 30 μM protein was allowed to aggregate for 30 h. Subsequently, the freshly prepared seeds were sonicated and added to a fresh 30 μM SOD1 solution. For the seeding experiment, the kinetics were monitored in a similar manner as mentioned before. Quercetin was prepared at a concentration of 1 mg/ml in ethanol. The effective concentration of ethanol was kept at around 2% of the total volume of the sample. Aggregation kinetics of 30 μM SOD1 was also monitored in the presence of 10, 30, 40, and 50 μM quercetin as mentioned earlier. Similarly, aggregation kinetics of different concentrations of SOD1 protein (20, 30, 40, 50 µM) was monitored in the presence of 25 µM quercetin.

Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) of proteins

The samples were collected at different time intervals from the aggregation kinetics experiments involving 30 μM SOD1 in the absence and presence of 50 μM quercetin. After filtering the samples with 0.22 μm syringe filter, 500 μl of the sample was injected into the column. For the aggregation analysis and oligomer isolation, the sample was passed through fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) using Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 GC, (GE Healthcare) size exclusion column. A 25 mM phosphate buffer of pH 7.4 was used as the mobile phase for the isocratic elution. The absorbance was recorded at wavelengths of 254 nm and 280 nm. The protein peaks in the chromatogram were deconvoluted to find dimer and monomer areas under the curve using OriginPro 2020b software.

The kinetic profile of dimer to monomer formation was fitted with the first order integrated rate law

D = dimer area at different time t

\(D\)0 = dimer area at t = 0 min

k1= rate constant

The kinetic profile of monomer to non-native dimer conversion was fitted with second-order integrated rate laws : -

\({A}_{{mono}}\)= monomer area at different times,

\({A}_{{mono}(0)}\) = monomer area at t = 0 min

k2 = rate constant for the second-order reaction.

ANS experiment to study changes in protein hydrophobicity

The ANS fluorescence spectra were measured to monitor any changes in the hydrophobicity of protein samples after removing metal ions and the disulfide bond. Protein samples (30 μM) with and without 50 µM quercetin were mixed with 600 μM ANS and spectra were recorded for 120 min at 15 min time intervals. The excitation and emission slit widths were kept at 5 nm and ANS spectra were recorded from 400 nm to 700 nm at an excitation wavelength of 350 nm.

Data fitting and analysis

For obtaining the kinetic parameters for the aggregation of SOD1, the kinetics profiles were fitted using the following equation77,97.

Where y = Fluorescence intensity

\({y}_{0}\) = Initial baseline of the kinetics curve

\(A\) = Final baseline of the kinetics curve

The apparent rate constant \({k}_{{app}}\) = 1/b and lag time \({\tau }_{{lag}}={x}_{0}-2b\)

Before fitting with Eq. (8), the kinetics data was normalized with respect to the maximum fluorescence intensity.

Sample preparation and spectral collection for SERS

The plasmonic silver nanoparticles (AgNP) were prepared using the Lee Meisel method98. 18 mg of AgNO3 was dissolved in 100 ml of water and brought to boiling. 2 ml of 1% aqueous sodium citrate solution was added and the mixture was stirred for 60 min. The heating was then stopped, and the solution was brought to room temperature while stirring and the solution was dialyzed for 24 h against pure water using a cellulose membrane with a cut-off molecular weight of 14 kDa. The nanoparticle solution was concentrated 10 times through centrifugation and 2 μL of the expressed protein solution was incubated with 10 μL of the nanoparticle solution activated by 2 μL NaCl solution (1.0 M) for 10 min. 10 μL of the solution mixture was dropped on an aluminum substrate for spectral acquisition. The Raman spectra of prepared samples were recorded using a Horiba Xplora Raman spectrometer. The excitation laser set at 532 nm and a 50x objective was used to collect the Raman spectra. For every sample, the holes, slit widths, and grooves were set to 300 μm, 100 μm, and 1800 groves/mm, respectively. The accumulation time was typically set at 10 s and 30 spectra were accumulated to obtain the final spectrum. The Origin 10 software was used to post-process the Raman spectra such as smoothing and background subtraction and for plotting the final spectra. Principal component analysis (PCA) was employed for the analysis of Raman data obtained from different samples of the protein and its oligomers (30 spectra from each sample). PCA was performed by converting the original variables into a set of linear combinations (principal components or PCs) and the analysis was done using the Orange software99.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper in its supplementary data files. The source data underlying Figs. 1, 2, and 7 are provided in Supplementary Data 1, Figs. 4, 5, 8, and Supplementary Figs. 8, 10, 12, and 13 are provided in Supplementary Data 2, Figs. 3, 9, and Supplementary Figs. 2(b), 11 are provided in Supplementary Data 3, Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig 1(b) and Fig. 2(a) are provided in Supplementary Data 4.

Abbreviations

- SOD 1 :

-

Superoxide dismutase 1

- ALS :

-

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

- SEC :

-

Size exclusion chromatography

- DTT :

-

Dithiothreitol

- ANS :

-

1-anilinonaphtalene-8-sulfonate

- EDTA :

-

Ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid

- ThT :

-

Thioflavin T

- UV :

-

Ultraviolet

- SERS :

-

Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy

- PCA :

-

Principal component analysis

- PDB :

-

Protein data bank

References

Nielsen, L. et al. Effect of environmental factors on the kinetics of insulin fibril formation: elucidation of the molecular mechanism. Biochemistry 40, 6036–6046 (2001).

Holm, N. K. et al. Aggregation and fibrillation of bovine serum albumin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 1774, 1128–1138 (2007).

Dolui, S., Roy, A., Pal, U., Saha, A. & Maiti, N. C. Structural insight of amyloidogenic intermediates of human insulin. ACS Omega 3, 2452–2462 (2018).

Blennow, K., De Leon, M. J. & Zetterberg, H. Alzheimer’s Disease. www.thelancet.com vol. 368 http://www.alzgene.org (2006).

Dauer, W. & Przedborski, S. Parkinson’s disease. Neuron 39, 889–909 (2003).

Rowland, L. P. & Shneider, N. A. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 344, 1688–1700 (2001).

R., H. et al. Folding and Aggregation of Cu, Zn-Superoxide Dismutase. in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (InTech, 2012). https://doi.org/10.5772/31629.

Pasinelli, P. & Brown, R. H. Molecular biology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: insights from genetics. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 710–723 (2006).

Sheng, Y. et al. Superoxide Dismutases and Superoxide Reductases. Chem. Rev. 114, 3854–3918 (2014).

Mccords, J. M. & Fridovich, I. Superoxide dismutase. An enzymic function for erythrocuprein (hemocuprein). J. Biol. Chem. 244, 6049–6055 (1969).

Rakhit, R. & Chakrabartty, A. Structure, folding, and misfolding of Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Basis Dis. 1762, 1025–1037 (2016).

Forsberg, K. et al. Novel antibodies reveal inclusions containing non-native SOD1 in sporadic ALS patients. PLoS One 5, e11552 (2010).

Bosco, D. A. et al. Wild-type and mutant SOD1 share an aberrant conformation and a common pathogenic pathway in ALS. Nat. Neurosci. 13, 1396–1403 (2010).

Rotunno, M. S. & Bosco, D. A. An emerging role for misfolded wild-type SOD1 in sporadic ALS pathogenesis. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 7, 253 (2013).

Lang, L. et al. SOD1 aggregation in ALS mice shows simplistic test tube behavior. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 9878–9883 (2015).

Nordlund, A. et al. Functional features cause misfolding of the ALS-provoking enzyme SOD1. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 106, 9667–9672 (2009).

Lindberg, M. J., Normark, J., Holmgren, A. & Oliveberg, M. Folding of human superoxide dismutase: disulfide reduction prevents dimerization and produces marginally stable monomers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 101, 15893–15898 (2004).

Lindberg, M. J., Byström, R., Boknäs, N., Andersen, P. M. & Oliveberg, M. Systematically perturbed folding patterns of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)-associated SOD1 mutants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 102, 9754–9759 (2005).

Jonsson, P. A. et al. Minute quantities of misfolded mutant superoxide dismutase-1 cause amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Brain 127, 73–88 (2004).

Byström, R., Andersen, P. M., Gröbner, G. & Oliveberg, M. SOD1 mutations targeting surface hydrogen bonds promote amyotrophic lateral sclerosis without reducing apo-state stability. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 19544–19552 (2010).

Zetterström, P. et al. Soluble misfolded subfractions of mutant superoxide dismutase-1s are enriched in spinal cords throughout life in murine ALS models. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 104, 14157–14162 (2007).

Teilum, K. et al. Transient structural distortion of metal-free Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase triggers aberrant oligomerization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 106, 18273–18278 (2009).

Johansson, A. S. et al. Cytotoxicity of superoxide dismutase 1 in cultured cells is linked to Zn2+ chelation. PLoS One 7, e36104 (2012).

Lang, L., Kurnik, M., Danielsson, J. & Oliveberg, M. Fibrillation precursor of superoxide dismutase 1 revealed by gradual tuning of the protein-folding equilibrium. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 109, 17868–17873 (2012).

Hnath, B. & Dokholyan, N. V. Toxic SOD1 trimers are off-pathway in the formation of amyloid-like fibrils in ALS. Biophys. J. 121, 2084–2095 (2022).

Ding, F. & Dokholyan, N. V. Dynamical roles of metal ions and the disulfide bond in Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase folding and aggregation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 105, 19696–19701 (2008).

Khare, S. D., Ding, F. & Dokholyan, N. V. Folding of Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase and familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Mol. Biol. 334, 515–525 (2003).

Khare, S. D., Caplow, M. & Dokholyan, N. V. The rate and equilibrium constants for a multistep reaction sequence for the aggregation of superoxide dismutase in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 101, 15094–15099 (2004).

Proctor, E. A., Mowrey, D. D. & Dokholyan, N. V. β-Methylamino-L-alanine substitution of serine in SOD1 suggests a direct role in ALS etiology. PLoS Comput Biol. 15, e1007225 (2019).

Redler, R. L. et al. Glutathionylation at Cys-111 induces dissociation of wild type and FALS mutant SOD1 dimers. Biochemistry 50, 7057–7066 (2011).

Proctor, E. A. et al. Nonnative SOD1 trimer is toxic to motor neurons in a model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 614–619 (2016).

Han-Xiang, D. et al. Amyotrophic lateral ssclerosis and structural defects in Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase. Science 261, 1047–1051 (1993).

Furukawa, Y., Kaneko, K., Yamanaka, K., O’Halloran, T. V. & Nukina, N. Complete loss of post-translational modifications triggers fibrillar aggregation of SOD1 in the familial form of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 24167–24176 (2008).

Valentine, J. S., Doucette, P. A. & Potter, S. Z. Copper-zinc superoxide dismutase and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Ann. Rev. Biochem. 74, 563–593 (2005).

Culotta, V. C., Yang, M. & O’Halloran, T. V. Activation of superoxide dismutases: putting the metal to the pedal. Biochim. et. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Mol. Cell Res. 1763, 747–758 (2006).

Rosen, D. R. et al. Mutations in Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase gene are associated with familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nature 362, 59–62 (1993).

Gurney, M. E. et al. Motor neuron degeneration in mice that express a human Cu,Zn superoxide dismutase mutation. Science 264, 1772–1775 (1994).

Shaw, B. F. & Valentine, J. S. How do ALS-associated mutations in superoxide dismutase 1 promote aggregation of the protein? Trends Biochem. Sci. 32, 78–85 (2007).

Siddhanta, S. & Narayana, C. Surface enhanced raman spectroscopy of proteins: implications for drug designing. Nanomater. Nanotechnol. 2, 1 (2012).

Cialla-May, D. et al. Raman spectroscopy and imaging in bioanalytics. Anal. Chem. 94, 86–119 (2022).

Hering, K. et al. SERS: A versatile tool in chemical and biochemical diagnostics. Anal. Bioanaly. Chem. 390, 113–124 (2008).

Gahlaut, S. K. et al. SERS platform for dengue diagnosis from clinical samples employing a hand held Raman spectrometer. Anal. Chem. 92, 2527–2534 (2020).

Han, X. X., Zhao, B. & Ozaki, Y. Surface-enhanced Raman scattering for protein detection. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 394, 1719–1727 (2009).

Davis, A. M., Teague, S. J. & Kleywegt, G. J. Application and limitations of x-ray crystallographic data in structure-based ligand and drug design. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 42, 2718–2736 (2003).

Wagner, G. Prospects for NMR of large proteins. J. Biomol. NMR 3, 375–385 (1993).

Durbin, S. D. & Feher, G. Protein crystallization. Ann. Rev. DURBIN.DUN 16 www.annualreviews.org (1996).

Sharma, S., Modi, P., Sharma, G. & Deep, S. Kinetics theories to understand the mechanism of aggregation of a protein and to design strategies for its inhibition. Biophys. Chem. 278, 106665 (2021).

Ivanova, M. I., Lin, Y., Lee, Y. H., Zheng, J. & Ramamoorthy, A. Biophysical processes underlying cross-seeding in amyloid aggregation and implications in amyloid pathology. Biophys. Chem. 269, 106507 (2021).

Ahmed, R. & Melacini, G. A biophysical toolset to probe the microscopic processes underlying protein aggregation and its inhibition by molecular chaperones. Biophys. Chem. 269, 106508 (2021).

Cawood, E. E., Karamanos, T. K., Wilson, A. J. & Radford, S. E. Visualizing and trapping transient oligomers in amyloid assembly pathways. Biophys. Chem. 268, 106505 (2021).

Mishra, R. et al. Lysozyme amyloidogenesis is accelerated by specific nicking and fragmentation but decelerated by intact protein binding and conversion. J. Mol. Biol. 366, 1029–1044 (2007).

Mishra, R. et al. Small-molecule inhibitors of islet amyloid polypeptide fibril formation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 4679–4682 (2008).

Dolui, S. et al. Order, disorder, and reorder state of lysozyme: aggregation mechanism by Raman spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. B 124, 50–60 (2020).

Bhatia, N. K., Modi, P., Sharma, S. & Deep, S. Quercetin and Baicalein act as potent antiamyloidogenic and fibril destabilizing agents for SOD1 fibrils. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 11, 1129–1138 (2020).

Sharma, S., Tomar, V. R., Jayaraj, A. & Deep, S. A computational strategy for therapeutic development against superoxide dismutase (SOD1) amyloid formation: effect of polyphenols on the various events in the aggregation pathway. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25, 6232–6246 (2023).

Sekhar, A. et al. Thermal fluctuations of immature SOD1 lead to separate folding and misfolding pathways. Elife 4, e07296 (2015).

Furukawa, Y. & O’Halloran, T. V. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mutations have the greatest destabilizing effect on the apo- and reduced form of SOD1, leading to unfolding and oxidative aggregation. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 17266–17274 (2005).

Tiwari, A. & Hayward, L. J. Familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis mutants of copper/zinc superoxide dismutase are susceptible to disulfide reduction. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 5984–5992 (2003).

Yamazaki, K., Tahara, S., Ohyama, T., Kuroi, K. & Nakabayashi, T. SOD1 gains pro-oxidant activity upon aberrant oligomerization: change in enzymatic activity by intramolecular disulfide bond cleavage. Sci. Rep. 12, 11750 (2022).

Redler, R. L., Fee, L., Fay, J. M., Caplow, M. & Dokholyan, N. V. Non-native soluble oligomers of Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD1) contain a conformational epitope linked to cytotoxicity in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Biochemistry 53, 2423–2432 (2014).

Schrand, A. M., Braydich-Stolle, L. K., Schlager, J. J., Dai, L. & Hussain, S. M. Can silver nanoparticles be useful as potential biological labels? Nanotechnology 19, 235104 (2008).

Keating, C. D., Kovaleski, K. M. & Natan, M. J. Protein: colloid conjugates for surface enhanced raman scattering: Stability and control of protein orientation. J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 9404–9413 (1998).

Ma, H. et al. Rapidly determining the 3D structure of proteins by surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh8362 (2023).

Li, C. Y. et al. Observation of inhomogeneous plasmonic field distribution in a nanocavity. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 922–926 (2020).

Siddhanta, S., Karthigeyan, D., Kundu, P. P., Kundu, T. K. & Narayana, C. Surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy of Aurora kinases: direct, ultrasensitive detection of autophosphorylation. RSC Adv. 3, 4221–4230 (2013).

Wang, Z. L., Luo, Q. H., Qian, W. & Shen, M. C. A study on bovine erythocyte superoxide dismutase by controlled potential electrolysis and Raman spectra. Bioelectrochemistry 64, 33–37 (2004).

Barth, A. & Zscherp, C. What vibrations tell us about proteins. Q. Rev. Biophys. 35, 369–430 (2002).

Moskovits, M. & Suh, J. S. Surface selection rules for surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy: calculations and application to the surface-enhanced Raman spectrum of phthalazine on silver. J. Phys. Chem. 88, 5526–5530 (1984).

Gu, S., Xu, M., Chen, L., Shi, X. & Luo, S. Z. A liquid-to-solid phase transition of Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase 1 initiated by oxidation and disease mutation. J. Biol. Chem. 299, 102857 (2023).

Pelton, J. T. & McLean, L. R. Spectroscopic methods for analysis of protein secondary structure. Anal. Biochem. 277, 167–176 (2000).

Jackson, M. & Mantsch, H. H. Protein secondary structure from FT-IR spectroscopy: correlation with dihedral angles from three-dimensional Ramachandran plots. Can. J. Chem. 69, 1639–1642 (1991).

Furukawa, Y., Kaneko, K., Yamanaka, K. & Nukina, N. Mutation-dependent polymorphism of Cu,Zn-superoxide dismutase aggregates in the familial form of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 22221–22231 (2010).

Wang, L.-Q. et al. Cryo-EM structure of an amyloid fibril formed by full-length human SOD1 reveals its conformational conversion. Nat. Commun. 13, 3491 (2022).

Bekard, I. & Dunstan, D. E. Electric field induced changes in protein conformation. Soft Matter 10, 431–437 (2014).

Stepanenko, T. et al. Surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) and tip-enhanced Raman scattering (TERS) in label-free characterization of erythrocyte membranes and extracellular vesicles at the nano-scale and molecular level. Analyst 149, 778–788 (2024).

Ferrone, F. [17] Analysis of protein aggregation kinetics. in 256–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0076-6879(99)09019-9 (1999).

Saha, S. & Deep, S. Protein Aggregation: Elucidation of the Mechanism and Determination of Associated Thermodynamic and Kinetic Parameters. Curr. Phys. Chem. 4, 114–136 (2014).

Cohen, S. I. A., Vendruscolo, M., Dobson, C. M. & Knowles, T. P. J. From macroscopic measurements to microscopic mechanisms of protein aggregation. J. Mol. Biol. 421, 160–171 (2012).

Saha, S. & Deep, S. Glycerol inhibits the primary pathways and transforms the secondary pathway of insulin aggregation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 18934–18948 (2016).

Cohen, S. I. A. et al. Nucleated polymerization with secondary pathways. I. Time evolution of the principal moments. J. Chem. Phys. 135, 065105 (2011).

Meisl, G., Michaels, T. C. T., Linse, S. & Knowles, T. P. J. Kinetic analysis of amyloid formation. in Methods in Molecular Biology vol. 1779 181–196 (Humana Press Inc., 2018).

Cohen, S. I. A., Vendruscolo, M., Dobson, C. M. & Knowles, T. P. J. Nucleated polymerization with secondary pathways. II. Determination of self-consistent solutions to growth processes described by non-linear master equations. J. Chem. Phys. 135, 065106 (2011).

Cohen, S. I. A. et al. Proliferation of amyloid-β42 aggregates occurs through a secondary nucleation mechanism. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 9758–9763 (2013).

Sharma, S., Tomar, V. R. & Deep, S. Mechanism of the interaction of toxic SOD1 fibrils with two potent polyphenols: curcumin and quercetin. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25, 23081–23091 (2023).

Altangerel, N. et al. Label-free drug interaction screening via Raman microscopy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2218826120 (2023).

He, X. et al. Raman spectroscopy coupled with principal component analysis to quantitatively analyze four crystallographic phases of explosive CL-20. RSC Adv. 8, 23348–23352 (2018).

Luo, Y., Zhang, X., Zhang, Z., Naidu, R. & Fang, C. Dual-principal component analysis of the Raman spectrum matrix to automatically identify and visualize microplastics and nanoplastics. Anal. Chem. 94, 3150–3157 (2022).

Hanson, C., Sieverts, M. & Vargis, E. Effect of principal component analysis centering and scaling on classification of mycobacteria from Raman spectra. Appl Spectrosc. 71, 1249–1255 (2017).

Shinzawa, H., Awa, K., Kanematsu, W. & Ozaki, Y. Multivariate data analysis for Raman spectroscopic imaging. J. Raman Spectrosc. 40, 1720–1725 (2009).

Sharma, A., Mondal, S., Ahuja, T., Karmakar, T. & Siddhanta, S. Ion-Mediated Protein Stabilization on Nanoscopic Surfaces. Langmuir https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.langmuir.2c03010 (2022).

Szekeres, G. P. & Kneipp, J. SERS probing of proteins in gold nanoparticle agglomerates. Front Chem. 7, 30 (2019).

Frieden, C. Protein aggregation processes: In search of the mechanism. Protein Sci. 16, 2334–2344 (2007).

Buell, A. K., Dobson, C. M. & Knowles, T. P. J. The physical chemistry of the amyloid phenomenon: thermodynamics and kinetics of filamentous protein aggregation. Essays Biochem 56, 11–39 (2014).

Kodaka, M. Interpretation of concentration-dependence in aggregation kinetics. Biophys. Chem. 109, 325–332 (2004).

Tachu, B. J., Wüsten, K. A., Garza, M. C., Wille, H. & Tamgüney, G. An easy method for bacterial expression and purification of wild-type and mutant superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1). Protein Expr. Purif. 134, 63–71 (2017).

Bhatia, N. K. et al. Curcumin binds to the pre-fibrillar aggregates of Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD1) and alters its amyloidogenic pathway resulting in reduced cytotoxicity. Biochim Biophys. Acta Proteins Proteom. 1854, 426–436 (2015).

Sharma, S., Tomar, V. R. & Deep, S. Myricetin: A Potent Anti-Amyloidogenic Polyphenol against Superoxide Dismutase 1 Aggregation. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 14, 2461–2475 (2023).

Lee, P. C. & Meisel’, D. Adsorption and Surface-Enhanced Raman of Dyes on Silver and Gold Sols’. J. Phys. Chem. 86, 3391–3395 (1982).

Demšar, J. et al. Orange: Data Mining Toolbox in Python Tomaž Curk Matija Polajnar Laň Zagar. Journal of Machine Learning Research vol. 14 (2013).

Strange, R. W. et al. The structure of holo and metal-deficient wild-type human Cu, Zn superoxide dismutase and its relevance to familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Mol. Biol. 328, 877–891 (2003).

Keskin, S., Efeoğlu, E., Keçeci, K. & Çulha, M. Label-free detection of proteins in ternary mixtures using surface-enhanced Raman scattering and protein melting profiles. J. Biomed. Opt. 18, 037007 (2013).

Pavan Kumar, G. V., Ashok Reddy, B. A., Arif, M., Kundu, T. K. & Narayana, C. Surface-enhanced raman scattering studies of human transcriptional coactivator p300. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 16787–16792 (2006).

Acknowledgements

This work is generously supported by SERB (CRG/2020/002091) date 22nd December 2020) through funds to Shashank Deep. Vijay Raj Tomar and Shilpa Sharma thank UGC India for the financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Vijay R. Tomar and Shilpa Sharma contributed equally. Vijay R. Tomar carried out all the experiments, analyzed the data, and reviewed the paper. Shilpa Sharma planned the research, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. S.D. planned the research and edited the final manuscript. Soumik Siddhanta supervised the SERS part of experiments and edited the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer review reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tomar, V.R., Sharma, S., Siddhanta, S. et al. Biophysical and spectroscopical insights into structural modulation of species in the aggregation pathway of superoxide dismutase 1. Commun Chem 8, 22 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01421-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01421-5