Abstract

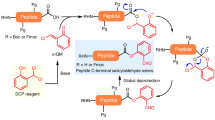

Native chemical ligation (NCL) has emerged as the most extensively employed chemoselective reaction in chemical protein synthesis (CPS). Nevertheless, the inherently low reactivity of peptide alkyl thioesters often necessitates the use of excessive nucleophilic additives in NCL to facilitate the reaction. Herein, we describe a rapid, and additive-free peptide ligation reaction between peptide thioacid and N-terminal cysteinyl peptide without epimerization in the present vinyl thianthrenium tetrafluoroborate (VTT). VTT promotes quantitative and chemoselective activation of fully unprotected C-terminal peptide thioacids into thioester intermediates, which demonstrate exceptional reactivity, facilitating rapid NCL in an additive-free manner with high yields. This additive-free strategy is fully compatible with post-ligation desulfurization, allowing for a streamlined one-pot process that enhances the overall efficiency and simplicity of CPS workflows. The effectiveness of this methodology is demonstrated by synthesizing hyalomin-3 from two fragments through a one-pot thioesterification-ligation-desulfurization protocol and ubiquitin through a one-pot C-to-N sequential three-segment condensation (six steps in one pot).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Proteins, the most abundant biomolecules in living systems, play essential functional and structural roles within cells and are integral to advancements in synthetic, biomedical, pharmaceutical and materials chemistry. Chemical protein synthesis (CPS), which involves the chemoselective ligation of synthetic peptide fragments, enabling the incorporation unnatural amino acids, biophysical probes or specific post-translational modifications at any desired protein sites, has emerged as a powerful strategy for generating homogeneous proteins of interest1,2,3,4,5,6,7. Among various ligation strategies developed (e.q., serine/threonine ligation (STL)8, cysteine/penicillamine ligation (CPL)9, α-ketoacid-hydroxylamine (KAHA) ligation10, and diselenide-selenoester ligation (DSL)11), native chemical ligation (NCL), introduced by Kent and colleagues in 199412, has proven to be the most popular ligation reaction in CPS13. It involves the chemoselective coupling of an unprotected C-terminal peptide thioester with an N-terminal cysteinyl peptide through an initial transthioesterification, followed by a rapid intramolecular S-to-N acyl transfer to generate the native peptide bond (Fig. 1a). However, the reliance on cysteine (Cys) at the ligation site limits its utility, as Cys residues are relatively rare in proteins (1.7%)14 as well as not all such residues are suitable as ligation sites. A significant breakthrough in ligation methodology was the development of metal-free desulfurization (MFD) chemistry15,16,17 which converts Cys residues into alanine (Ala) following the ligation event. Given that Ala is the second most common amino acid (7.8%)14, the combination of NCL with desulfurization significantly expands the scope of NCL-based CPS15,18. In fact, most previously synthesized proteins have relied on NCL and its extended methods13.

Streamlining sequential NCL and MFD reactions through a one-pot operation is highly desirable to minimize operational complexity, reduce costs and improve synthetic efficiency. Due to their ease of preparation and stability to long-term storage, peptide alkyl thioesters are commonly utilized in ligation chemistry. However, their intrinsically low reactivity often demands an excess of nucleophilic additives (as high as 0.2-2.5 M) to enhance reaction kinetics and achieve efficient ligation (Fig. 1a)19,20. Among them, 4-mercaptophenyl acetic acid (MPAA) being the most widely employed and gold standard additive13 however, significantly quenches the radical-based MFD process, which led to a required operation of removing it between the NCL and MFD steps. Recently, a variety of thiol and no-thiol additives have been explored as replacements for MPAA to facilitate one-pot NCL-MFD operations, including 2,2,2-trifluoroethanethiol (TFET)21, methyl thioglycolate (MTG)22, 2-sulfanylmethyl-4-dimethylaminopyridine (SMDMAP)23, Thiocholine24, imidazole25, 1,2,4-triazole26 and 3-methylpyrazle27. Despite advancements. a significant excess of additives is still essential to facilitate the additional nucleophile-thioester exchange step. Therefore, the development of rapid, additive-free ligation reactions provides excellent compatibility with the one-pot NCL-MFD strategy, while simultaneously improving atom economy and contributing to enironmental sustainability.

Herein, we report that fully unprotected C-terminal peptide thioacids can be quantitatively and selectively converted to the corresponding epimerization-free thioesters in the presence of vinyl thianthrenium tetrafluoroborate (VTT) under acidic NCL conditions. The resulting highly reactive intermediates rapidly undergo NCL without the need for an additive with high yield in a one-pot process, termed VTT-promoted thioacid-based additive-free NCL (VTANCL) (Fig. 1b). The absence of an additive in the ligation steps allows the VTANCL strategy to be applied for the synthesis of target proteins through a one-pot thioesterification-ligation-desulfurization approach. The validity and practicability of this new strategy are demonstrated through the efficient total synthesis of hyalomin-3 (Hyal-3)28 and ubiquitin in a one-pot process.

Results and discussion

Reaction design

Peptide C-terminal thioacids, recognized as potent peptidyl thioester surrogates, are facilely accessed from peptide hydrazides obtained through SPPS or recombinant expression methods29,30,31,32,33. State-of-the-art methodologies have been established for the chemical synthesis of peptides or proteins using thioacids32,34,35,36,37,38,39,40. Vinyl thianthrenium salts, developed as unique vinylating reagents, have found widespread applications in a plethora of organic synthesis reactions41,42,43,44,45. Recent research has highlighted the utility of two specific variants, VTT and vinyl tetrafluorothianthrenium tetrafluoroborate (VTFT), in thiol alkylation within protein chemistry46. These compounds function as reactive Michael acceptors and leaving groups, facilitating the displacement of alkylsulfonium species to episulfonium intermediates that are reactive towards a range of nucleophiles under biological relevant conditions. Given these findings, we propose that these vinyl thianthrenium salts could be effectively employed for thioacid esterification in aqueous media. This transformation can convert peptide or protein thioacids into their corresponding alkyl thioesters with notable reactivity, owing to the favorable leaving ability of thianthrenium, thereby significantly facilitating subsequent chemical ligation. Additionally, the thioacid exhibits exceptional nucleophilicity and a lower pKa value compared to other proteinogenic groups, thereby enabling high selectivity in thioesterification process.

Proof of concept

In our initial study, we explored the reactivity of VTT with the model fully unprotected C-terminal peptide thioacid Ac-LYRAA-SH (1a) within an NCL buffer environment. Specifically, peptide 1a (2.0 mM) was treated with 1.2 equivalents of VTT in a solution of 6.0 M guanidine hydrochloride (Gn·HCl) / 0.2 M phosphate buffer, at pH 7.0 and 25 oC (Table 1, Entry 6; Supplementary Fig. 46A and B). Reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) and mass spectrometry analyses identified a new peak with rt = 23.8 min, corresponding to the molecular weight of peptide 1a combined with VTT. In contrast, peptide carboxylic acid Ac-LYRAA-OH (1b) remained intact under identical conditions (Supplementary Fig. 47). These results suggested that the product formed was peptide acythianthrenium Ac-LYRAA-SVTT (2a) (Supplementary Fig. 46C) (isolated yield 87%, MW = 893.35), rather than peptide acyepisulfonium 2a’, peptide hydroxyethyl thioester 2a” (arising from ring-opening by H2O) (Table 1) or other unprotected amino acid side chain conjugates with VTT. The observed difference in products formed between thioacid and thiol with VTT could be attributed to the lower nucleophilicity of sulfur in thioester compared to thioether (Supplementary Scheme 1). The unknown byproduct (MW = 452, rt = 18.4 min) and hydrolysis product resulted in a low yield, motivating us to further optimize the reaction. As the pH decreased, the yield experienced a significant improvement. Particularly under acidic aqueous conditions (pH = 2.0, 3.0, 4.0, and 5.0, Table 1, Entries 1-4; Supplementary Fig. 46A and B), yields exceeding 90% were achieved within 4.0 h. We selected a mild condition (pH = 5.0) for further optimization. Using 1.2 equivalents of VTT were sufficient for reaction completion (Table 1, Entry 4, 7, and 8; Supplementary Fig. 48). To speed up the reaction, we either elevated the temperature to 37 oC (Table 1, Entry 9; Supplementary Fig. 49) or introduced various organic solvents into the NCL buffer (Table 1, Entries 10-16; Supplementary Figs. 50 and S51). It was determined that the optimal result was obtained with 20% DMF in the NCL buffer (pH = 5.0) with 1.2 equivalents of VTT within 2.0 h at 25 oC. As will be further detailed in the subsequent sections, the VTT-promoted thioesterification step is fully compatible with all the proteinogenic groups.

Encouraged by these findings, we then turned our attention to the behavior of peptide acythianthrenium (2a) in NCL under one-pot reaction conditions. Given the favorable leaving ability of thianthrenium, 2a was expected to exhibit significant reactivity, promoting us to explore the feasibility of performing NCL without the need of additional additives. To quench the excess VTT, TCEP (10.0 mM, 10.0 eq.) was added to the above reaction mixture, and the resultant mixture was incubated for another 5.0 min. Subsequently, N-Cys peptide H-CGYAH-OH (3a, 1.5 mM, 1.5 eq.) was introduced, and the pH was adjusted to 7.0 ~ 8.0. Remarkably, the ligation product decapeptide Ac-LYRAACGYAH-OH (4a) was obtained with an impressive yield of 98% for two steps within 2.0 h (Scheme 1). Further control ligation was carried out between 2a and 3a, along with the N-Ala peptide H-AYYHA-OH (3b). Only desired ligation product 4a was observed, instead of direct aminolysis product Ac-LYRAAAYYHA-OH (4ab), even at a higher concentration of 3b (10.0 mM), indicating that the ligation is chemoselective toward the N-Cys peptide (Supplementary Fig. 52). Ac-LYRAA-MPAA (2b) thioester, the most reactive aryl thioester, was selected as a control to compare their kinetics in the ligation reaction (Fig. 2). 2a exhibited rapid ligation efficiency, achieving over 85% conversion in just 5.0 min and completing the reaction in 60.0 min, comparable to the performance of model 2b. Furthermore, the presence of MPAA (10.0 mM) resulted in only a slight enhancement in ligation efficiency. Notably, a controlled increase in pH (below 8.5) was found to improve their kinetic results, though the data is not shown here. These results validated our prior hypotheses. Consequently, we developed a strategy where VTT quantitatively promotes C-terminal peptide thioacid esterification, thereby ensuring that the corresponding thioester product undergoes NCL with high yield in a one-pot process without requiring additional additives.

a Reaction scheme of ligation. b Results of various C-terminal amino acid substructs. aThe concentration of 1a, 1e-1u was 2.0 mM in the first VTT-promoted thioesterification step, and all 3a was 1.5 mM (1.5 e.q) in the second ligation step; Yields presented were calculated through the application of the internal standard method, whereas isolated yields obtained following RP-HPLC purification by weight over two steps are provided in parentheses; bConditions: pH 2.0 and VTT (1.5 eq.) during the first VTT-promoted thioesterification step; cConditions: pH 4.0 and VTT (1.5 eq.) during the first VTT-promoted thioesterification step; dConditions: VTT (1.5 eq.) during the first VTT-promoted thioesterification step; eConditions: pH 8.5 during the second ligation step; fConditions: VTT (1.4 eq.) during the first VTT-promoted thioesterification step, and pH 8.5 during the second ligation step; For more details, refer to the supplementary information.

Chemoselectivity study

Subsequently, we proceeded to examine the chemoselectivity of the VTT-promoted thioacid esterification among other unprotected amino acid side chains. When tripeptides containing basic amino acid residues Lys (5a), His (5b), Arg (5c) were treated with VTT under the standard reaction conditions, no reaction could be detected even after extended reaction time (6.0 h) (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 53A, B, C). This phenomenon was attributed to the protonation of these basic functional groups under weakly acidic reaction conditions, which led to a loss of nucleophilicity. Similarly, the unprotected nucleophilic hydroxyl groups of serine (5 d), and tyrosine (5e) (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 53D, E) remained intact, likely due to their low nucleophilicity. Other tripeptides containing Asp (5 f), Gln (5 g), and Trp (5 h) were investigated and found to be compatible under standard reaction conditions (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 53F, G, H). Furthermore, the VTT-promoted thioacid thioesterification was performed in the presence of all possible reactive side chains, excluding Cys (Fig. 3b). When a mixture of peptide 1a (2.0 mM) and peptide H-NWKHA-OH (1c, 2.0 mM) was treated with VTT (2.4 mM), only peptide 2a was observed, while 1c stayed unreacted. Even at a higher concentration of 1c (20.0 mM), almost no interaction with VTT was detected (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 54). Next, we focused on the chemoselectivity between thiol group in Cys residue and thioacid. Upon adding 1.2 eq. of VTT to a mixture of peptide 1a and Ac-LYRAC-OH (1 d), and incubating the solution for 2.0 h, compounds 2a, 2 d (episulfonium formed by Cys in 1 d reaction with VTT and hydrolyzing with H2O) and 2ad (a conjugate formed when episulfonium intermediate was attacked by thioacid in 1a) were identified (Fig. 3b, Entry 11). Given the pKa values of the thioacid (pKa = 3) and thiol (pKa = 8.0 ~ 8.5) group in Cys, we hypothesized that lowering the solvent pH might enhance the selectivity for the thioacid over the thiol group. Screening pH levels ranging from 2.0 to 6.0 (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 55), we found that at pH 2.0 and pH 3.0, the thiol group did not react, even increasing the concentration of 1 d to 20.0 mM (Fig. 3c). These findings suggest that VTT-promoted thioacid esterification is chemoselective towards other unprotected amino acid side chains under acidic conditions.

a Reaction testing of tripeptides containing different possibly reactive residues with VTT under standard conditions, N.R. = no reaction; b Reaction testing of model peptides containing all possibly reactive residues with VTT under different conditions, aHPLC yield was determined by integrated areas of RP-HPLC peaks at λ = 214 nm, bThe relative proportion of each product was calculated from its peak area; c Under pH 2.0 and 3.0, VTT-promoted thioacid esterification shows excellent selectivity over Cys residue, peak 1 d’ indicates the disulfide product of 1 d, peak 2a indicates peptide acythianthrenium Ac-LYRAA-SVTT, peak # indicates interior standard (Benzamide), peak * indicates the hydrolysis byproduct of 1a or 2a.

Epimerization test

The potential loss of chiral integrity during both thioacid esterification and NCL was rigorously investigated before exploring scope and applications of our strategy. A series of thioacid peptides bearing C-terminal residues such as Phe, Ser, and Ala were examined, with Ser47 and Phe32,37 identified as particularly prone to epimerization. During thioesterification, peptide thioacids Ac-LYRA(L)S-SH 1p (Fig. 4a) and its D-isomer Ac-LYRA(D)S-SH (1p’) (Fig. 4b) produced distinct single products Ac-LYRA(L)S-SVTT (2p) (Fig. 4c) and Ac-LYRA(D)S-SVTT (2p’) (Fig. 4d) with unique retention times. The ligation products Ac-LYRA(L)SCGYAH-OH (4p) (Fig. 4e) and Ac-LYRA(D)SCGYAH-OH (4p’) (Fig. 4f) generated from 2p and 2p’ with 3a were compared with standard decapeptides synthesized by Fmoc-based SPPS (Fmoc-SPPS) (Fig. 4g). No detectable levels of epimerization were observed by RP-HPLC. Similar results were obtained with the C-terminal Phe thioacid peptide (Supplementary Fig. 56) and the C-terminal Ala thioacid peptide (Supplementary Fig. 57). These findings confirm that the stereochemistry of the C-terminal amino acid remains intact throughout both thioesterification and subsequent ligation.

a Analytical RP-HPLC trace of isolated Ac-LYRA(L)S-SH (1p); b Analytical RP-HPLC trace of isolated Ac-LYRA(D)S-SH (1p’); c Analytical RP-HPLC trace of thioesterification of 1p with VTT, Ac-LYRA(L)S-SVTT (2p) is the thioesterification product; d Analytical RP-HPLC trace of thioesterification of 1e’ with VTT, Ac-LYRA(L)S-SVTT (2p’) is the thioesterification product; e Analytical RP-HPLC trace of ligation of 2p with H-CGYAH-OH (3a), Ac-LYRA(L)SCGYAH-OH (4p) is the ligation product; f Analytical RP-HPLC trace of ligation of 2p’ with H-CGYAH-OH (3a), Ac-LYRA(D)SCGYAH-OH (4p’) is the ligation product; g Analytical RP-HPLC trace of isolated standard decapeptides mixture synthesized by SPPS, the all L-peptide is labeled with L and the D-Ser5 epimer with D. Peak # indicates interior standard (Benzamide), peak * indicates the hydrolysis byproduct of 1p or 1p’.

The scope of the VTANCL strategy

We next tested the VTANCL strategy on model peptide thioacids featuring various C-terminal residues (1a, 1e-1u, Ac-LYRAX-SH, Scheme 1) and found that most of these peptides achieved high yields of 86%-98% over two steps (in the present MPAA (10.0 ~ 100.0 mM), the yields were increased slightly only (data was not shown)). Notably, a moderate yield was observed for the C-terminal His thioacid peptide due to a certain amount of hydrolysis byproduct, which formed from the acyl imidazole intermediate (Supplementary Fig. 62). In typical NCL reactions involving C-terminal glutamyl peptides, a significant quantity of γ-linked side-product is often formed. Remarkably, in this study, only a trace amount of this side-product was detected in the C-terminal Glu thioacid peptide (Supplementary Fig. 71A, B). Based on our observations (Supplementary Fig. 71C), We hypothesize that under slightly basic conditions, the kinetics of ligation in our system are favored over those of glutaric anhydride formation. Ligation at Asp-Cys and Asn-Cys sites is widely acknowledged to be problematic. Attempts to prepare the corresponding peptide thioacids resulted exclusively in hydrolysis or with succinimide byproducts, with no detectable thioacid products. Sterically hindered amino acids (valine (Val), isoleucine (Ile), proline (Pro)), which are challenging substrates for traditional NCL, generally require prolonged reaction times or harsh conditions and result in low yields. Apart from steric effect, deactivation of the thioester by the Pro amide carbonyl results in Pro exhibiting the poorest reactivity. Nevertheless, our study demonstrated that these amino acids reacted smoothly and rapidly (2.0 h for Val and Ile, 24.0 h for Pro), yielding the desired products in acceptable yields. These data suggest that the VTANCL strategy proceeds smoothly over a wide scope of ligation sites.

Total synthesis of Hyal-3 and ubiquitin via one-pot thioesterication-ligation-desulfurization based on VTANCL

Inspired by the successful outcomes observed with model peptides, we advanced to assess the applications of the VTANCL strategy in the context of CPS. Oury primary target was Hyral-3, a thrombin-inhibiting hyalomin protein. In this research, the full-length Hyal-3 was disconnected into two segments at Lys37-Ala38 (Fig. 5a). Notably, Ala38 was incorporated as Cys during Fmoc-SPPS and could be desulfurized after ligation to restore the Ala side-chain (Fig. 5b). Hyal-3 (1-37)-SH (1) was facilely accessed from its hydrazide precursor, peptide hydrazide Hyal-3 (1-37)-NHNH2, through the Knorr pyrazole chemistry-based thiolysis reaction. Both of Hyal-3 (1-37)-NHNH2 and Hyal-3 (38-59)-OH (3) bearing a N-terminal Cys mutant were synthesized on 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin via standard Fmoc-SPPS. Initially, the purified peptide 1 (2.0 mM) was dissolved in weakly acidic ligation buffer (6.0 M Gn·HCl, 0.2 M Na2HPO4, 20% DMF, pH 5.0) and treated with VTT (2.4 mM). After incubation at 25 oC for 2.0 h, the thioesterification reached completion to produce 2, followed by adding TCEP (20.0 mM, 10.0 eq.) to quench excess VTT and maintain a reducing environment. After 5.0 min, peptide 3 (1.0 mM, 1.0 eq.) was added into the above solution and the pH was adjusted to 7.4 by NaOH aq. (1.0 M), followed by incubation for an additional 2.0 h at 37 oC to complete ligation. Without purification, the crude reaction was dosed with t-BuSH, TCEP and the radical initiator VA-044, and incubated for another 2.0 h, which led to complete desulfurization of Cys38 to Ala. Semipreparative HPLC purification then provided Hyal-3 (5) in 56.8% yield over the 3 steps, one-pot process.

a The sequence of Hyal-3 (1-59); the ligation site is indicated with a dash. b Scheme of the synthesis of Hyal-3 (1-59) via a one-pot thioesterification-ligation-desulfurization. aisolated yield was determined after deducting the inseparable impurity present in the starting material Hyal-3 (1-37)-SH. c Analytical RP-HPLC traces (λ = 214 nm) of each step of the reaction. Peak # indicates interior standard (Benzamide), peak * indicates inseparable impurity found in 1, peak ** indicates product formed by TCEP quenching excess VTT, 3’ indicates desulfurization product of 3. d ESI-MS characterizations of the major products (average isotopes).

To further explore effectiveness and efficiency of our strategy in multiple-segment condensation in one-pot, we proceeded to synthesize monoubiquitin, an important model protein that consists of 76 amino acid residues, which plays a crucial role in various cellular processes through a post-translational modification known as ubiquitination. We adopted a three-segment (1-27 + 28-45 + 46-76) approach in the C-to-N direction to sequentially assemble full-length ubiquitin (Fig. 6a). Similarly, Ala28 and Ala46 were mutated to Cys during Fmoc-SPPS and were converted back to Ala after desulfurization. N-terminal Cys of the middle segment Ubiquitin (28-45) was protected by 1,3-thiazolidine-4-carboxo (Thz) group to prevent cyclization. C-terminal peptide thioacids Ubiquitin (1-27) (6) and Thz-Ubiquitin (28-45) (7) were obtained from Ubiquitin (1-27)-NHNH2 and Thz-Ubiquitin (28-45)-NHNH2 respectively via the Knorr pyrazole chemistry-based thiolysis reaction. All of Ubiquitin (1-27)-NHNH2, Thz-Ubiquitin (28-45)-NHNH2, and Ubiquitin (46-76)-OH (9) were prepared on 2-chlorotrityl chloride resin via standard Fmoc-SPPS.

a The sequence of ubiquitin (1-76); the ligation site is indicated with a dash. b Scheme of the synthesis of ubiquitin (1-76) via a one-pot C-to-N sequential three-segment condensation (six steps in one pot). c Analytical RP-HPLC traces (λ = 214 nm) of each step of the reaction. Peak # indicates interior standard (Benzamide), peak * indicates the hydrolysis byproduct of 8, peak ** indicates product formed by TCEP quenching excess VTT, peak ◆ indicates deprotection product of *, peak ▲ indicates desulfurization product of ◆, 9’ indicates desulfurization product of 9, 11’ indicates desulfurization product of 11. d ESI-MS characterizations of the major products (average isotopes).

The first thioesterification was conducted in a ligation buffer containing 6.0 M Gn·HCl, 0.2 M Na2HPO4, 20% DMF, pH 5.0. The purified peptide 7 (4.0 mM, 1.5 eq.) was treated with VTT (4.8 mM, 1.8 eq.) at 25 oC and incubated for 2.0 h to complete the reaction, followed by adding TCEP (16.0 mM, 6.0 eq.). Upon addition of peptide 9 (1.6 mM, 1.2 eq.) to the above solution, the first ligation finished at pH 7.4 within 2.0 h at 37 oC to afford 10. Without further purification, the crude reaction was added 2.0 M methoxyamine·HCl (50.0 eq.) and adjusted pH to 4.0 to remove the Thz protecting group, yielding 11. Left segment C-terminal peptide thioacid 6 (4.0 mM, 1.0 eq) was esterified to produce 12 in the presence of VTT (4.8 mM, 1.2 eq.) within 2.0 h. The second ligation between 11 and 12 was performed at 37 oC under pH 7.4 and finished within 2.0 h. The resulting mixture was then incubated with additional TCEP, t-BuSH and VA-044 for another 24.0 h to achieve the desulfurization. Gratifyingly, full-length ubiquitin 14 was obtained with an isolated yield of 28.2% following a single semipreparative HPLC purification step (one pot over six steps, determined based on the limiting thioacid peptide 6).

Conclusion

In summary, a novel and highly efficient additive-free NCL approach is introduced. In our strategy, vinyl thianthrenium salt VTT enables the quantitative and efficient in situ esterification of fully unprotected C-terminal peptide thioacids with excellent selectivity over all the proteinogenic groups, without any racemization under acidic NCL conditions. The resulting highly reactive thioester product facilitates smooth, additive-free, one-pot NCL with high yields under neutral conditions. It performed nearly as effectively as that MPAA thioester in ligation reactions. This additive-free ligation enables efficient one-pot ligation and desulfurization protocol, significantly improving the synthetic efficiency by reducing intermediary purification steps, and shortening overall operation time. Additionally, avoiding the excessive usage of additives can reduce synthesis costs, minimize the generation of chemical waste, and contribute to environmental sustainability. The efficacy and feasibility of the VTANCL strategy are demonstrated through the total synthesis of Hyal-3 from two fragments via one-pot thioesterification-ligation-desulfurization protocol and ubiquitin via one-pot C-to-N sequential three-segment condensation (six steps in one pot, in which each ligation step completed rapidly within 2.0 h). Given its efficiency and simplicity, the VTANCL strategy is promising for assembling multiple peptide segments to synthesize challenging protein targets, contributing to broaden the current synthetic toolbox. Another notable advantage of our strategy lies in the use of peptide thioacids as peptide thioester precursors, enabling one-pot N-to-C sequential multi-segment condensation without protecting groups, which is currently being investigated in our laboratory, and the results will be reported in due course.

Methods

Preparation of VTT from thianthrene-S-oxide

Thianthrene-S-oxide (500.4 mg, 2.2 mmol, 1.0 eq.), MeCN (10.0 mL, c = 0.22 M), and vinyl-SiMe3 (631.0 μL, 431.8 mg, 4.3 mmol, 2.0 eq.) were introduced into a round-bottom flask equipped with a stirring bar. The solution was cooled to 0 °C, followed by the sequential addition of trifluoroacetic anhydride (900.0 μL, 1.4 g, 6.5 mmol, 3.0 eq.) and trifluoromethanesulfonic acid (205.0 μL, 387.9 mg, 2.6 mmol, 1.2 eq.). The mixture was stirred at 0 °C for 30.0 min, then warmed to 25 °C and stirred for an additional 60 min. After concentration under reduced pressure, the residue was diluted with DCM (30.0 mL), washed with saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (30.0 mL), and the aqueous layer extracted with DCM (2 × 20.0 mL). The combined organic phases were washed with 5.0% NaBF4 solution (2 × 30.0 mL), dried over Na2SO4, filtered, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The crude product was dissolved in DCM (2.0 mL), and Et2O (13.0 mL) was added to precipitate a solid, which was collected by filtration, washed with Et2O (3 × 3.0 mL), and dried under vacuum to yield VTT as a yellow solid.

General procedure for the synthesis of peptide thioacids

Peptide thioacids were prepared from the corresponding peptide hydrazides using a Knorr pyrazole chemistry-based thiolysis strategy. Peptide hydrazides were synthesized on hydrazine-loaded 2-Cl-(Trt) resin (2-Cl-(Trt)-NH2NH2 resin) via standard Fmoc-SPPS. The resin was generated by treating swelled 2-Cl-(Trt)-Cl resin with 5.0 mL of 5% (v/v) NH2NH2/DMF for 30.0 min at room temperature, followed by sequential washing with DMF (3 × 5.0 mL), DCM (3 × 5.0 mL), and DMF (3 × 5.0 mL), repeated twice. The resin was subsequently capped with DCM/MeOH/DIPEA (17:2:1, v/v/v, 5.0 mL) for 10.0 min, repeated three times, then filtered and washed with DMF, DCM, and DMF (3 × 5.0 mL each). Fmoc deprotection was performed using 20.0% piperidine in DMF for 10 min, followed by washing with DMF (10 × 5.0 mL). Iterative peptide assembly yielded the peptide hydrazide product. The crude peptide hydrazide (15.0 mM, 1.0 eq.; 5.0 mM for Hyal-3 and ubiquitin) was reacted with acetylacetone (5.0 eq.) and MPAA (30.0 eq.) in buffer (6.0 M Gn·HCl, 0.1 M Na2HPO4, pH 2.0). After 1.0 h incubation at room temperature, Na2S·9H2O (20.0 eq.) was added, and the pH was adjusted to 7.0 with 10.0% aqueous HCl. The mixture was stirred for 4.0 h under argon to complete the transformation, confirmed by RP-HPLC. Products were purified by preparative RP-HPLC, and purity and mass were verified by analytical RP-HPLC and ESI-MS.

General procedure for the VTANCL strategy

The peptide thioacid (2.0 mM, 1.0 eq.) and internal standard (2.0 mM, 1.0 eq.) were dissolved in ligation buffer (6.0 M Gn·HCl, 0.2 M Na2HPO4, 20.0% DMF, pH 5.0). VTT (2.4 mM, 1.2 eq.) was subsequently added, and the mixture was incubated at 25.0 °C for 2.0 h. Aliquots (3.0 μL) were withdrawn, quenched with 57.0 μL of 1.0% TFA in water, and analyzed by analytical RP-HPLC. The remaining reaction mixture was treated with TCEP (20.0 mM, 10.0 eq.) and incubated for 5.0 min to quench excess VTT. N-terminal cysteinyl peptide (1.5 mM, 1.5 eq.) was then introduced, the pH was adjusted to 7.0 ~ 8.0, and incubation was continued for 2.0–24.0 h at 37.0 °C. Aliquots (6.0 μL) were quenched with 54.0 μL of 1.0% TFA in water and analyzed by analytical RP-HPLC to monitor thioesterification and ligation competition. The final ligation product was purified by semi-preparative RP-HPLC and characterized by ESI-MS. HPLC yields were determined using the internal standard method, while isolated yields were calculated from RP-HPLC purification over two steps.

Data availability

Detailed experimental procedures and characterization of all substrates and products can be found in the Supplementary Information. The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files, and are also available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

References

Kent, S. B. Total chemical synthesis of proteins. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 338–351 (2009).

Kent, S. B. Chemical synthesis of peptides and proteins. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 57, 957–989 (1988).

Dong, S. et al. Recent advances in chemical protein synthesis: method developments and biological applications. Sci. China Chem. 67, 1060–1096 (2024).

Bondalapati, S., Jbara, M. & Brik, A. Expanding the chemical toolbox for the synthesis of large and uniquely modified proteins. Nat. Chem. 8, 407–418 (2016).

Tan, Y., Wu, H. X., Wei, T. Y. & Li, X. C. Chemical protein synthesis: advances, challenges, and outlooks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 20288–20298 (2020).

Kulkarni, S. S., Sayers, J., Premdjee, B. & Payne, R. J. Rapid and efficient protein synthesis through expansion of the native chemical ligation concept. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2, 122 (2018).

Merrifield, R. B. Solid phase peptide synthesis. I. The synthesis of a tetrapeptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 85, 2149–2154 (1963).

Zhang, Y. et al. Protein chemical synthesis by serine and threonine ligation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 6657–6662 (2013).

Tan, Y. et al. Cysteine/penicillamine ligation independent of terminal steric demands for chemical protein synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 12741–12745 (2020).

Pusterla, I. & Bode, J. W. The mechanism of the α-ketoacid-hydroxylamine amide-forming ligation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 513–516 (2012).

Mitchell, N. J. et al. Rapid additive-free selenocystine-selenoester peptide ligation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 14011–14014 (2015).

Dawson, P. E., Muir, T. W., Clark-Lewis, I. & Kent, S. B. Synthesis of proteins by native chemical ligation. Science 266, 776–779 (1994).

Agouridas, V. et al. Native chemical ligation and extended methods: mechanisms, catalysis, scope, and limitations. Chem. Rev. 119, 7328–7443 (2019).

Agouridas, V., El Mahdi, O., Cargoet, M. & Melnyk, O. A statistical view of protein chemical synthesis using NCL and extended methodologies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 25, 4938–4945 (2017).

Wan, Q. & Danishefsky, S. J. Free-radical-based, specific desulfurization of cysteine: a powerful advance in the synthesis of polypeptides and glycopolypeptides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 9248–9252 (2007).

Jin, K. & Li, X. C. Advances in native chemical ligation-desulfurization: a powerful strategy for peptide and protein synthesis. Chem. Eur. J. 24, 17397–17404 (2018).

Sun, Z. Q. et al. Superfast desulfurization for protein chemical synthesis and modification. Chem 8, 2542–2557 (2022).

Yan, L. Z. & Dawson, P. E. Synthesis of peptides and proteins without cysteine residues by native chemical ligation combined with desulfurization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 526–533 (2001).

Johnson, E. C. & Kent, S. B. Insights into the mechanism and catalysis of the native chemical ligation reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 6640–6646 (2006).

Diemer, V., Firstova, O., Agouridas, V. & Melnyk, O. Pedal to the metal: the homogeneous catalysis of the native chemical ligation reaction. Chem. Eur. J. 28, e202104229 (2022).

Thompson, R. E. et al. Trifluoroethanethiol: an additive for efficient one-pot peptide ligation-desulfurization chemistry. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 8161–8164 (2014).

Huang, Y. C. et al. Synthesis of L-and D-ubiquitin by one-pot ligation and metal-free desulfurization. Chem. Eur. J. 22, 7623–7628 (2016).

Ohkawachi, K. et al. Sulfanylmethyldimethylaminopyridine as a useful thiol additive for ligation chemistry in peptide/protein synthesis. Org. Lett. 22, 5289–5293 (2020).

Suzuki, S. et al. Thiocholine-mediated one-pot peptide ligation and desulfurization. Molecules, 28, (2023).

Sakamoto, K. et al. Imidazole-aided native chemical ligation: imidazole as a one-pot desulfurization-amenable non-thiol-type alternative to 4-mercaptophenylacetic acid. Chem. Eur. J. 22, 17940–17944 (2016).

Sakamoto, K., Tsuda, S., Nishio, H. & Yoshiya, T. 1,2,4-Triazole-aided native chemical ligation between peptide-N-acyl-N’-methyl-benzimidazolinone and cysteinyl peptide. Chem. Commun. 53, 12236–12239 (2017).

Liao, P. & He, C. Azole reagents enabled ligation of peptide acyl pyrazoles for chemical protein synthesis. Chem. Sci. 15, 7965–7974 (2024).

Watson, E. E. et al. Rapid assembly and profiling of an anticoagulant sulfoprotein library. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 13873–13878 (2019).

Fang, G. M. et al. Protein chemical synthesis by ligation of peptide hydrazides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 7645–7649 (2011).

Huang, Y. C., Fang, G. M. & Liu, L. Chemical synthesis of proteins using hydrazide intermediates. Nat. Sci. Rev. 3, 107–116 (2016).

Chen, C. C. et al. Thiol-assisted one-pot synthesis of peptide/protein C-terminal thioacids from peptide/protein hydrazides at neutral conditions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 12, 9413–9418 (2014).

Chu, G. C. et al. Ferricyanide-promoted oxidative activation and ligation of protein thioacids in neutral aqueous media. CCS Chem. 6, 2031–2043 (2024).

Flood, D. T. et al. Leveraging the Knorr pyrazole synthesis for the facile generation of thioester surrogates for use in native chemical ligation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 11634–11639 (2018).

Timmann, S., Feng, Z. & Alcarazo, M. Recent applications of sulfonium salts in synthesis and catalysis. Chem. Eur. J. 30, e202402768 (2024).

Crich, D. & Sharma, I. Epimerization-free block synthesis of peptides from thioacids and amines with the Sanger and Mukaiyama reagents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 2355–2358 (2009).

Wang, P. et al. Encouraging progress in the ω-aspartylation of complex oligosaccharides as a general route to β-N-linked glycopolypeptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 1597–1602 (2011).

Wang, P. & Danishefsky, S. J. Promising general solution to the problem of ligating peptides and glycopeptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 17045–17051 (2010).

Tatsumi, T. et al. Practical N-to-C peptide synthesis with minimal protecting groups. Commun. Chem. 6, 231 (2023).

Tam, J. P., Lu, Y. A., Liu, C. F. & Shao, J. Peptide synthesis using unprotected peptides through orthogonal coupling methods. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 12485–12489 (1995).

Tsuji, K. et al. Application of N–C- or C–N-directed sequential native chemical ligation to the preparation of CXCL14 analogs and their biological evaluation. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 19, 4014–4020 (2011).

Jia, H. et al. Trifluoromethyl thianthrenium triflate: a readily available trifluoromethylating reagent with formal CF3+, CF3*, and CF3- reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 7623–7628 (2021).

Meng, H., Liu, M. S. & Shu, W. Organothianthrenium salts: synthesis and utilization. Chem. Sci. 13, 13690–13707 (2022).

Julia, F., Yan, J. Y., Paulus, F. & Ritter, T. Vinyl thianthrenium tetrafluoroborate: a practical and versatile vinylating reagent made from ethylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 12992–12998 (2021).

Lansbergen, B. et al. Reductive cross-coupling of a vinyl thianthrenium salt and secondary alkyl iodides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202313659 (2023).

Ye, Y., Zhu, J., Xie, H. J. & Huang, Y. H. Rhodium-catalyzed divergent arylation of alkenylsulfonium salts with arylboroxines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202212522 (2022).

Hartmann, P. et al. Chemoselective umpolung of thiols to episulfoniums for cysteine bioconjugation. Nat. Chem. 16, 380–388 (2024).

Snella, B. et al. Native chemical ligation at serine revisited. Org. Lett. 20, 7616–7619 (2018).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the generous financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22007015), Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province, China (Grant No. 2023J01553), Joint Funds for the Innovation of Science and Technology of Fujian Province, China (Grant No. 2024Y9101), and Research Foundation for Advanced Talents at Fujian Medical University, China (Grant No. XRCZX2020008). Prof. Kenzo Yamatsugu, Prof. Eric R. Strieter and Prof. Jinshun Lin are thanked for helpful comments on manuscript. We also thank Mrs Xue Mi from the Public Technology Service Center of Fujian Medical University for providing assistance in mass spectrometry assay.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The project was conceived, designed, and supervised by J. A. L., W. C., and C. M. C. All experiments were performed by H. H. L., and S. J. X. Data was analyzed by H. H. L. Some peptides and small molecules were prepared by Z. C. Z., R. J. X., and J. Y. L. The manuscript was written by J. A. L., and H. H. L. with some important comments from J. J. M., and C. S. Z.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, H., Xu, S., Zhang, Z. et al. Rapid vinyl thianthrenium tetrafluoroborate-promoted thioacid-based native chemical ligation and its applications in chemical protein synthesis. Commun Chem 9, 1 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01811-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42004-025-01811-9