Abstract

Recent experiments have implemented resetting by means of a time-varying external harmonic trap, whereby the trap stiffness is changed in finite-time and the system is reset when it relaxes to an equilibrium distribution in the final trap. Such setups are very similar to those studied in the context of the finite-time Landauer erasure principle. In this work, we analyze the thermodynamic costs of such a setup by deriving a moment generating function for the work cost of recurrently changing the trap stiffness, thereby maintaining a non-equilibrium steady state. For this heretofore unstudied case, we obtain explicit expressions for the mean and variance of the work both for a specific experimentally viable protocol as well as an optimal protocol which minimizes the mean cost. For both these procedures, our analysis captures both the large-time and short-time corrections. For the optimal protocol, we obtain a closed form expression for the mean cost for all protocol durations, thereby making contact with earlier work on geometric measures of dissipation-minimizing optimal protocols that implement information erasure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Stochastic resetting refers to processes in which a system’s natural evolution is interrupted and restarted according to some predefined scheme, naturally driving the system out of thermal equilibrium1,2. Rich behaviors, such as non-trivial non-equilibrium steady state properties3,4, anomalous relaxation dynamics5,6,7 and potential for optimization in search processes8,9, have attracted much attention over the past decade, both theoretically and experimentally. Given this rich behavior and the multitudinous applications, it is very natural to consider the thermodynamic cost of a resetting operation or the cost associated with maintaining a steady-state resetting process. Particularly interesting are questions relating to fundamental thermodynamic bounds for such costs.

These questions take on an even greater significance in the light of the fact that the conceptually simple yet powerful renewal structure built into a resetting process (every reset erases memory and correlations of the system’s past evolution) also hints at deep connections to information erasure10,11. Early studies on the thermodynamic cost of resetting12,13, quantified this connection by bounding the average entropic cost for (instantaneous) resetting in analogy with Landauer’s principle of information erasure10. However, these studies did not take into account the actual work needed to implement a reset, which would necessarily also be influenced by the mechanism used to accomplish resetting, finite-time effects, as well as imperfections in the actual resetting.

Recent experiments14,15,16 that implement resetting provide a very easy and elegant framework within which to investigate such questions further. In these experiments, a colloidal particle moves either freely or within a trap until it is reset. Here, the resetting mechanism is facilitated via an optical confining (resetting) trap. The resetting trap is switched on either periodically or stochastically, for a duration long enough to relax the particle to the corresponding equilibrium thermal distribution in the trap. After this duration, the resetting trap is switched off. Notice that in contrast to resetting to an exact location (see ref. 17 for the corresponding experimental procedure), here the particle resets instead to a position drawn from the equilibrium thermal distribution in the resetting trap.

In this guise too, the resetting problem can be posed as an information erasure problem, whereby, in analogy to how classical bit erasure is implemented via optical traps18,19,20,21,22, one could ask what the thermodynamic cost is for turning on the resetting trap, very slowly, instantaneously or in finite-time, and hence erasing all previous information at a (time-dependent) cost. In analogy with Landauer’s principle, it is also very interesting to understand what the fundamental bound is on such a cost now taking into account the physical constraints of both time and energy which need to be spent to carry out the erasure.

In previous work, we have studied such a system and obtained the average and fluctuations of the work needed to turn on the resetting trap23,24 or the heat dissipated25 as the particle relaxes in the resetting trap. Other studies involving “first-passage-resetting", i.e., when an optical trap is kept switched on until the particle makes a first-passage to a specified location, have also considered average work costs26,27,28 and fluctuations27. In all these studies however, the resetting trap is considered to be switched on instantaneously. If however, in analogy with several studies on finite-time bit erasure18,19,20,21,22,29,30,31,32, one is interested in lower bounds on the thermodynamic cost of resetting, it is necessary to consider the cost as a function of the time it takes to switch on the resetting trap. Such a cost will now also depend on the protocol used for turning on the trap, namely on how the trap parameters are modified to transform the initial trap into the final one.

If the state of the system at the start is an equilibrium state, the second law of thermodynamics places a bound on the minimum work required to change the control parameter; this is just the equilibrium free energy difference between the initial and final state. Any protocol that pays only this minimum cost is a protocol that operates quasi-statically, so that the system is never out of equilibrium for the entire duration. In the context of bit erasure, many experiments18,19,20,21,22,31 have been performed to probe both the bound as well as the actual cost to carry out the erasure process in finite time. Several theoretical works29,30,32,33 also address this issue.

Although it is possible to look at specific, experimentally viable protocols, theoretically, such questions are best addressed in the context of optimal protocols; a protocol engineered so as to minimize some cost of interest such as the mean work performed or the mean dissipation. Two optimization problems that are typically studied in this context are: 1) Designing optimal protocols that transition between two specified distributions within finite time34,35,36,37,38,39,40 and 2) designing optimum protocols that minimize the cost needed to shift between two different potential energy landscapes, often harmonic, in finite time38,39,41,42,43,44,45,46. A different but related class of problems, inspired by the so-called shortcut to adiabatically processes47,48,49,50,51, study optimal protocols devised so as to take the system from one equilibrium state to another in a time much faster than the intrinsic relaxation time of the system52.

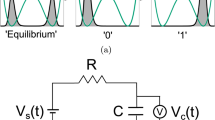

In this paper, we address the second optimization problem mentioned in the above paragraph. Namely, we address the question of estimating the work cost of a classical overdamped system when changing the potential from U to V, effectively implementing an erasure in a fixed time τ. We formally write down the moment generating function for this process for any U and V. However, we carry out explicit calculations for the mean and variance of the work for harmonic potentials where we transform a harmonic potential U to a harmonic potential V by changing the stiffness of the trap in a finite time τ according to a generic experimentally viable protocol as well as an optimal protocol. This system has been studied very extensively in the past, in experiments14,16,52,53,54,55,56,57 and theoretically41,42,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68. In contrast to most of these previous studies (two exceptions are16 which studies this case albeit from a different aspect and63 who study an out-of-equilibrium though Gaussian state created by a measurement), we consider a steady-state system obtained by repeated applications of our erasure scheme shown in Fig. 1. The resulting state that needs to be erased is hence an out-of-equilibrium, non-Gaussian state. This fact has implications for the work cost of both generic as well as optimal protocols. As noted recently in the context of bit erasure69, it is possible, when beginning with an out-of-equilibrium initial state, to get costs lower than \({k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T\ln 2\) in agreement with a generalized Landauer bound70. We study this aspect in-depth for our system by formally obtaining, under very general conditions, the full moment generating function of the work performed in one cycle. From the expression for the moment generating function, we are able to compute the average work required to carry out one erasure cycle (as in Fig. 1) in the case of harmonic traps, both for a generic experimentally-viable protocol as well as optimal protocol. Our results hold for all time and not only in the short or large-time limits as in most earlier works. Our formalism also allows us in principle to look at and optimize higher moments of the work, or Pareto-optimal fronts encoding trade-offs (as done theoretically in71, numerically in67, or in Ref. 72 for quantum systems).

V(x): Resetting potential. U(x): Exploration potential. \({{{\mathcal{U}}}}(x;\lambda (t))\): Potential with a time-dependent protocol λ(t) such that \({{{\mathcal{U}}}}(x;\lambda (0))=U(x)\) and \({{{\mathcal{U}}}}(x;\lambda (\tau ))=V(x)\). The trapped particle is represented by the red sphere. The exploration time-interval t_1 is drawn from a distribution f(t_1) and duration for the protocol is τ. \({x}_{0}^{(V)}\) and \({x}_{0}^{(U)}\), respectively, are the particle’s positions at the beginning and end of the exploration phase.

Results and discussions

Model

Our system is subjected to a sequence of erasing protocols in time. Each erasing cycle (see Fig. 1) involves a single resetting event composed of two switching processes: 1) An instantaneous jump from the resetting (or stiff) potential V(x) to an exploration (or shallow) potential U(x) at time t = 0, after which the system stays in the potential U(x) for a time distributed according to some temporal distribution f(t). We call this phase the exploration phase. 2) After the completion of the exploration phase, a time varying potential \({{{\mathcal{U}}}}(x;\lambda (t))\) is switched on, in such a way that at the beginning and end of the resetting protocol, respectively, \({{{\mathcal{U}}}}(x;\lambda (t=0))=U(x)\) and \({{{\mathcal{U}}}}(x;\lambda (t=\tau ))=V(x)\). Here, τ is the duration of the potential-switching time. We call this phase the resetting phase. Once the potential V(x) has been turned on, the system stays a fixed amount of time in this potential, say a few times the relaxation-time, so that at the end of this relaxation phase, the system has relaxed to the Boltzmann distribution in this potential. At this point the cycle is complete and we switch instantaneously back to U(x). For convenience, henceforth, we drop the explicit mention of the time-dependence from λ(t). The time evolution of the system consists of a series of such erasing cycles.

The system’s dynamics is governed by the overdamped Langevin equation:

for the inverse temperature \(\beta \equiv {({k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T)}^{-1}\), and the diffusion constant D. Notice that the above equation is valid for both exploration and relaxation phase by respectively replacing \({{{\mathcal{U}}}}(x;\lambda )\to U(x)\) and \({{{\mathcal{U}}}}(x;\lambda )\to V(x)\). In the last term η(t) is a Gaussian thermal white noise which has zero mean and delta-correlations in time: \(\langle \eta (t)\eta ({t}^{{\prime} })\rangle =\delta (t-{t}^{{\prime} })\).

In this paper, we are interested in the cost of performing a complete erasing cycle. By the definition of our erasing cycle, this consists of two contributions. For the initial instantaneous jump, the performed work along a single stochastic trajectory is the change in the energy due to an instantaneous switch from potential V(x) to U(x),

whereas the work performed during the change of the potential from U(x) to V(x) in a time-dependent manner via the control parameter λ(t) is

for the switching time τ. Here, x( ⋅ ) represents the system’s trajectory. Therefore, the total stochastic work for one implementation of the erasing cycle is w = w1 + w2. Notice that during the relaxation phase, there is no work contribution since the control parameter is fixed. The stochasticity in this quantity has its origins in two factors: 1) the system’s size is small, so thermal fluctuations are significant, and 2) the time to stay in the exploration phase is drawn from a distribution f(t).

Moment generating function

For a trajectory containing n erasure cycles, i.e., n replicas of the cycle shown in Fig. 1, the total stochastic work performed will just be the sum of the stochastic works performed during each of these n cycles. Hence, we turn our attention first to understanding the distribution of work for a single cycle. The moment generating function of work w for a single erasure, implemented according to the scheme in Fig. 1, is defined as (For n cycles, the moment generating function is \({\langle {e}^{kw}\rangle }^{n}\)):

where the angled brackets indicate the average over thermal fluctuations, initial condition, and stochastic exploration time t. Here k is the conjugate variable with respect to work w. This implies

where we have substituted w1 from Eq. (2). Several comments are in order. \({C}_{0}(k,\tau ;{x}_{0}^{(U)})\) is the moment-generating function of work performed while changing the potential from U to V in a time-dependent manner (3), and herein we average the trajectories emanating from the position \({x}_{0}^{(U)}\). This \({x}_{0}^{(U)}\) is the position of the particle at the end of the exploration phase, therefore, \({x}_{0}^{(U)} \sim {P}_{U}({x}_{0}^{(U)},t| {x}_{0}^{(V)})\), where \({x}_{0}^{(V)}\) is the initial condition for the exploration phase’s trajectories. Notice that \({x}_{0}^{(V)}\) is drawn from the initial equilibrium distribution with respect to the potential V, \({P}_{{{{\rm{eq}}}},V}({x}_{0}^{(V)})\), since the system initially instantaneously switches from V to U after the relaxation phase. We have weighted Eq. (5) with respect to a temporal density, f(t), of time intervals in the exploration phase.

Inverting the above Eq. (5) for any form of potential seems difficult; nevertheless, it provides the means to obtaining the nth order moments of work. This is done as follows. Differentiating both sides of Eq. (5) n-times with respect to k and setting k = 0, we get,

Analytical calculations of the moments for arbitrary potentials is involved. Therefore, in what follows, we restrict ourselves to the case of harmonic potentials, as these are easily implemented and manipulated in experiments14,15. For this case, we obtain the mean and second moment of the work as follows (see Supplementary Note S1 for more details):

where

and we have defined a dimensionless length

for the trap relaxation time \({t}_{V,U}\equiv {(\beta D{\lambda }_{V,U})}^{-1}\). Here λV,U are the stiffnesses in the traps U and V respectively and \(\tilde{f}(s)=\int_{0}^{\infty }\,dt\,{e}^{-st}\,f(t)\) is the Laplace transform of the exploration time density. Note that tV/tU≤ζ2≤1 for any distribution f(t). I1,2,3 in Eq. (8) are respectively evaluated in Supplementary Eqs. (S16), (S17), and (S22).

The moment generating function for the work performed as the stiffness of the harmonic trap changes, has been studied in earlier work58,61,64,65,68 but only when the process begins from an equilibrium initial state. (We note that ref. 65 has a closed form expression for the moment generating function for arbitrary initial conditions. They investigate it however only for equilibrium initial conditions.) In the process we study here, the initial state is in general out-of-equilibrium. It becomes a Boltzmann distribution in the trap U only if the mean exploration time 〈t1〉 ≫ tU (see Fig. 1).

An experimentally motivated protocol with a Poissonian resetting rate

While the above analysis and the expression for the moments [Eqs. (7) and (8)] are true for any protocol λ(t), we specialize to an experimentally feasible protocol16:

Here, t* controls the speed of the protocol: the smaller the t* the faster λU transforms to λV. The total average work W [Eq. (7)] is the sum of two terms W1 + W2; W1 is the mean contribution of the instantaneous switch at the beginning of the cycle [this is the first term in the Eq. (7)] and W2 is the mean contribution of the finite-time switch back to potential V [the second term in Eq. (7) which we can now calculate explicitly].

Figure 2 shows the comparison of analytical mean and variance of the work W [using Eqs. (7) and (8)] for f(t) = re−rt as a function of t*, where r is the resetting rate. In both simulations and analytical results, we set the duration of the protocol to τ = 10t* so that at the end of protocol λ(τ) ≈ λV, as required. Both the mean and variance approach their respective stationary values in the quasi-static driving regime t* → ∞. From Fig. 2a we see, however, that unlike transformations between equilibrium states, the work performed during the quasistatic limit is not necessarily the minimum. To investigate this further, we focus only on the average work in what follows and compare what we get from an instantaneous versus quasi-static protocol.

Harmonic exploration and resetting potentials are used. Mean (〈W〉) and variance (〈W2〉 − 〈W〉2) as a function of time t* are plotted. Symbols: Numerical simulation. Lines: Analytical results using Eqs. (7) and (8) with f(t) = re−rt and the protocol in Eq. (11). a, b Red horizontal dashed lines indicate asymptotic values of mean work Wslow (14) and variance \({[D{t}_{V}({\lambda }_{V}-{\lambda }_{U})]}^{2}/2\) (see Supplementary Note S2 for more details). The color intensity increases with increasing resetting rate r. Here, we take the diffusion constant D = 0.5, γ = 1, λU = 0.125, λV = 0.25, and simulation time τ = 10t*. Number of resets: 105. a Error bars are one standard error of mean and are smaller than the symbol size.

In the limit t* → 0 (i.e., the fast switching limit), the total work simplifies to the following two contributions: 1) an instantaneous switch from V to U starting from equilibrium Peq,V(x), and 2) another instantaneous switch from U to V:

starting from the time-averaged distribution:

in the U(x) potential, where \({P}_{U}(x,t)\equiv \int_{-\infty }^{+\infty }d{x}_{0}{P}_{U}(x,t| {x}_{0}){P}_{V}^{{{{\rm{eq}}}}}({x}_{0})\). This time-averaged distribution is the non-equilibrium state at the beginning of our resetting/erasure protocol. Note that because of the renewal structure of our scheme, this distribution does not depend on any details of λ(t).

In contrast, in the infinitely slow switching of potential t* → ∞ (i.e., t* ≫ tU,V), we expect the average work to be

i.e., we expect that changing potential U to potential V sufficiently slowly will give rise to a work cost equal to the free energy difference between the two potentials. For this protocol, we can explicitly carry out an expansion in the long-time limit (see Supplementary Note S2) and show that this is indeed the case. As we will see in the next section however, this need not necessarily be the case for arbitrary protocols, i.e., an arbitrary protocol connecting out-of-equilibrium states need not have a work cost that equals the equilibrium free energy difference at long times.

The right-hand side of Eq. (14) can also be rewritten in the form of a KL-divergence (\({D}_{{{{\rm{KL}}}}}[p(x)| | q(x)]\equiv \int\,dx\,p(x)\ln \frac{p(x)}{q(x)}\)):

for the equilibrium distributions Peq,V(x) and Peq,U(x), respectively, with respect to potentials V and U. Thanks to the non-negativity of the KL-divergence we expect Wslow≥0. Using Eqs. (12) and (15), we get

Thus, the sign of the left-hand side depends on the KL-distance of PU(x, t) from the equilibrium distributions in the V and U potentials.

For harmonic potentials, we can explicitly compute the total average work in the instantaneous (12) and slow switching (14) limits, and hence also their difference. The total average work is W1 + W2, where

and

where the dimensionless length ζ is defined in Eq. (10).

Figure 3a shows the parameter regimes for f(t) = re−rt, where the average work Winst [Eq. (19a)] is larger or smaller than Wslow [Eq. (19b)]; in the unshaded region Winst > Wslow otherwise Winst < Wslow. Note that our erasure protocol can lie anywhere below the red diagonal (where tV < tU). In the shaded region, switching the potential in a finite time costs less work than switching quasi-statically, and is therefore a finite-time cost-effective region.

Harmonic exploration and resetting potentials with f(t) = re−rt are used. a Phase diagram using Eq. (19c) in the (rtU, rtV) plane, for resetting rate r and relaxation time \({t}_{V,U}\equiv {(\beta D{\lambda }_{V,U})}^{-1}\). b, c Mean work as a function of time t*; inset in c shows work as a function of t* (where t* is longer than that of the main panel). Note that the approach to the asymptotic value is from above in (c), indicating non-monotonic behavior at large times. Lines: Analytical results Eq. (7). The horizontal dashed line indicates Wslow (19b). Here, we take the diffusion constant D = 1. Number of resets: 105. Error bars show one standard error of mean. d Phase diagram from Panel a with added panels [obtained using Eq. (20)] indicating regions where mean work W is non-monotonic “NM” or monotonic “M” as a function of time. Blue regions: Winst < Wslow. Red regions: Winst > Wslow.

Figure 3b, c shows the mean total work W (in the region below the diagonal line in Fig. 3a) as tV increases from region II to I for a fixed tU for f(t) = re−rt. We can see that the work can be made smaller for smaller t* in region I of phase diagram 3a. Additionally, Fig. 3b, c exhibits the non-monotonic nature of the average work for some values of the parameters. To understand where in parameter space this occurs, we need to explore the large but finite t* to understand how the t* → ∞ limit is approached.

In order to do this, we adapt a technique sketched in64 to our system and expand the average work W2 in the slow-switching limit (t* → ∞) to first order in 1/t*(see Supplementary Note S2 for a detailed derivation). We show that the difference of average work W2 from the equilibrium free-energy difference in this limit is given by the correction term

where α ∝ 1/t* [Supplementary Eq. (S25)] is the slowness-parameter in the limit t* → ∞. Depending on the sign of the term inside the square brackets in Eq. (20), the approach to 0 is either positive or negative. Note that beginning from an equilibrium state (as in64 which we can also get by putting ζ2 = 1) results in a purely positive correction term. The fact that we get either a positive or negative contribution from the correction term is purely a result of the non-equilibrium state at the start of the protocol. Equation (20) together with the phase diagram in Fig. 3a, hence helps us identify regions where the average work is non-monotonic as a function of t*. This is displayed as a modified phase diagram in Fig. 3d.

Bounds on the average total work W

Long-time limit

Even though the above results hold for a specific protocol, it is clear that the equilibrium free energy difference is no longer in general a lower bound on the average work required for performing our erasure cycle, when the system starts from an out-of-equilibrium state (as was also noticed in the context of bit erasure in ref. 69). It is interesting to understand nevertheless if there are bounds on the total average work even in this case. As we have seen, the total average work is composed of two contributions: a contribution due to the average instantaneous work W1 and the average work W2 related to our protocol λ(t) for manipulating the trap stiffness. Since the first contribution to the total work does not depend on the protocol at all, we concentrate henceforth on W2. On very general grounds [irrespective of protocol λ(t), exploration time distribution f(t), and arbitrary U(x) and V(x)], it is expected that a bound on W2 will relate to the non-equilibrium free energy differences between the states at the start and end of the protocol. The minimal work required to transform one out-of equilibrium state into another is studied in ref. 70 and translates in our case to the following expression:

where Pta,U(x)(13) and P(x, τ), respectively, are the probability of the particle’s position at the beginning [λ(0) = λU] and end of the protocol [λ(τ) ≈ λV]. We refer to this bound as the Generalized Landauer work-bound (GL work-bound)70. For completeness we follow ref. 70 in Supplementary Note S3 to show how Eq. (21) can be derived just from the requirement that the the total entropy production be non-negative for the above process.

Figure 4a shows that the GL work-bound (21) clearly bounds the average work cost W2 of implementing the protocol (11). Tighter bounds may be found by minimizing W2 as a functional of the protocol λ(t) to obtain an optimal protocol as discussed below.

a Mean work W2 as function of (dimensionless) protocol duration rτ for the hyperbolic tangent protocol (7) (points) and the optimal protocol Eq. (22) (solid line). We use resetting probability density function f(t) = re−rt. The dashed line represents the theoretical bound (21). Here, we take the non-dimensionalized harmonic trap relaxation times rtU = 4, rtV = 0.5 where r is the resetting rate and tU, tV are the harmonic trap relaxation times. b Deviation from the theoretical Generalized Landauer (GL) work-bound (21) in the quasi-static limit as a function of the ratio of trap relaxation times tV/tU. Parameters used are D = γ = kBT = r = 1, and tU = 4.

Optimal protocol: long-time bounds

We search for the optimal protocol of varying the control parameter λ(t) that minimizes the average work W = W1 + W2. Since W1 does not depend on the protocol λ(t), it suffices to consider W2. Optimal protocols for harmonic traps have been studied in a wide range of contexts, including overdamped and underdamped Brownian motion34,35,39,41,46,63,67,73,74, with constraints on maximum trap stiffness44,75 as well as for active particles76,77.

In the context we are interested in, the calculation of the optimal (minimal work) protocol can be performed by using the standard Euler-Lagrange minimization of the work functional W2[λ(t)] as carried out in ref. 41. As opposed to all earlier studies however, we begin with a non-Gaussian out-of-equilibrium state Pta,U(x0) (13) at the start of the protocol, and this has to be incorporated into the minimization procedure. In ref. 63, the authors consider an initial state which has been rendered out-of-equilibrium by a measurement process. The state is however still Gaussian.

The optimal work performed on the system is

where the dimensionless length ζ is defined in Eq. (10), and the constant c2 is given by

A detailed derivation of the optimal protocol is included in Supplementary Note S4. The out-of-equilibrium initial state plays a role in the initial conditions. In the long-time limit (τ → ∞), we can show that \({c}_{2}\tau =-1+\sqrt{{t}_{V}/({t}_{U}{\zeta }^{2})}\), and this gives

Several points are worth noting. Since \(\ln {\zeta }^{2}+(1-{\zeta }^{2})\) is non-positive for all ζ, the long time work \({\lim }_{\tau \to \infty }{W}_{2}^{{{{\rm{opt}}}}}\le {F}_{U\to V}^{\,{\mbox{eq}}\,}\) irrespective of the choice of f(t), with the equality holding only when ζ2 = 1. Notice that ζ2 = 1 is only achieved by either tV = tU or \(\tilde{f}(2/{t}_{U})=0\). The former is a trivial solution and not interesting. The latter corresponds to when the system is in equilibrium in the U-trap. Hence, beginning from an out-of-equilibrium state reduces the long-time cost below the equilibrium value. (See Supplementary Fig. S1 for discussion on \({W}_{2}^{{{{\rm{opt}}}}}\) and behavior of the optimal protocol.)

Equation (24) can also be used to get a lower bound on the work as the distribution of the duration in the exploration phase, f(t), is varied. Note first that since \(\tilde{f}(2/{t}_{U})\le 1\), tV/tU≤ζ2≤1. In this range, the function \(\ln {\zeta }^{2}+(1-{\zeta }^{2})\) is non-positive and monotonic and attains a maximum value at ζ = 1. This ultimately gives the bound

Here, the equality is obtained for the case of vanishing duration in the exploration phase, f(t) = δ(t). In fact, the same holds for any protocol duration τ in the limit of vanishing exploration duration. This can be seen by expanding \(\tilde{f}(2/{t}_{U})=1-2\langle {t}_{1}\rangle /{t}_{U}+\ldots \,\) in Eq. (22), which results in

The first term on the right-hand side is the negative of the average work done due to the potential switch at time t = 0, i.e., − W1 [see the first term on the right-hand side of Eq. (7)]. Interestingly, to the first order there is no dependence on protocol duration (in the limit of vanishing duration in the exploration phase). Intuitively, in this regime the particle has no time to relax in the shallow trap, and the state at the beginning of the protocol is close to the Boltzmann state in the sharp trap. Hence, the optimal protocol is simply to discontinuously switch almost fully back to the sharp trap and remain there for the rest of the protocol duration, and therefore, the total work, \({W}_{1}+{W}_{2}^{{{{\rm{opt}}}}}\), performed in this limit vanishes.

In the opposite limit ζ2 = 1, the particle has time to equilibrate in the exploration phase, and the protocol connects two equilibrium states. In this case, we expect the work in the quasistatic limit to be given by the free energy difference \({\lim }_{{\zeta }^{2}\to 1}{\lim }_{\tau \to \infty }{W}_{2}^{* }=\Delta {F}_{U\to V}^{\,{\mbox{eq}}\,}\), as we verify from Eq. (24). One can also verify that the two limits commute, i.e. \({\lim }_{{\zeta }^{2}\to 1}{\lim }_{\tau \to \infty }{W}_{2}^{* }={\lim }_{\tau \to \infty }{\lim }_{{\zeta }^{2}\to 1}{W}_{2}^{* }\).

Another interesting aspect of the optimal protocol is that the average work is monotonic as a function of the duration τ, in contrast to the hyperbolic tangent protocol, i.e., for an optimal protocol, large τ implies lower mean work. This is seen in Fig. 4a, where the solid line shows the mean work associated with the optimal protocol. We also see that the optimal case indeed results in a lower mean work as compared to the hyperbolic tangent protocol, as it should. The late time work in the optimal protocol approaches the bound (24), which is different as explained above, from the GL work-bound (21). In Fig. 4b we quantify this by plotting the difference between the optimal work bound that we obtain and the GL bound Eq. (21). The bound is approached monotonically as tV → tU which is the limit corresponding to the trivial case when both potentials are identical and hence both the mean optimal work and the GL work-bound are zero.

Information-geometric interpretation

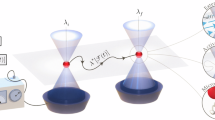

Equation (24) has a natural information-geometric interpretation. Since our initial state deviates from the Boltzmann state, we expect the information content of this non-equilibrium state to contribute to the work70,78. However, the full information content may not always be converted into (negative) work since we are constrained to harmonic trap shapes79. To make this argument more precise, we first consider the so-called m-projection

into a subspace \({{{\mathcal{B}}}}\) of Boltzmann states compatible with our trap, i.e., Gaussian densities in the context of harmonic traps (Fig. 5).

Projection π[Pta,U] of the true state Pta,U at the beginning of the protocol into a subspace \({{{\mathscr{B}}}}\) of Boltzmann densities compatible with the trap. DKL(p∣∣q) is the KL-divergence between two distributions p(x) and q(x). Only the deviation from the initial equilibrium state \({P}_{U}^{{{{\rm{eq}}}}}\) measured within this subspace can be converted to work.

Since q(x) is a generic Gaussian density, let’s say it has mean μ and standard deviation σ, the KL-divergence we want to minimize can be written as

where S[Pta,U] is the Shannon entropy of the true initial state. To minimize this over (μ, σ), we simply take the derivative with respect to these two parameters and solve for stationary points. This results in μ = 0 and \({\sigma }^{2}={\langle {x}^{2}\rangle }_{{{{\rm{ta}}}}}=D{t}_{U}{\zeta }^{2}\). Hence, the projected state π[Pta,U](x) is simply a Gaussian with matching first two moments of Pta,U.

The information between the true initial state and the instantaneous equilibrium state associated with the initial trap is measured by \({D}_{{{{\rm{KL}}}}}({P}_{{\mbox{ta}},U}\parallel {P}_{U}^{{{{\rm{eq}}}}})\), which in principle can be converted into work as seen in the GL work-bound (21). However, due to the constraints on the protocol (i.e., harmonic traps) only the KL-divergence \({D}_{{{{\rm{KL}}}}}(\pi [{P}_{{\mbox{ta}},U}]\parallel {P}_{U}^{{{{\rm{eq}}}}})\) between the projected initial state and the instantaneous equilibrium state (the accessible information) can be converted into work; see Fig. 5. Indeed, using well-established formulas for the KL divergence between two Gaussians, we find that Eq. (24) can be rewritten as:

Hence, the deviations from the bound given by Eq. (21) originates in the information loss associated with the projection of Pta,U → π[Pta,U].

Optimal protocol: finite-time results

The manner in which the bound in Eq. (24) is reached can be better understood in the light of recent work on geometrical measures of optimal minimum-work or minimum-dissipation protocols (see80 for a recent review on some of these aspects). To understand these results in our context, we first get the full τ-dependence of the optimal work \({W}_{2}^{{{{\rm{opt}}}}}\) by separating the time-independent and time-dependent terms in Eq. (22) by substituting c2 from Eq. (23):

The time-independent terms are just the non-equilibrium free energy difference that we obtained in Eq. (24). From general considerations32,34,35,37,38,39,80, we expect the time-dependent terms to be strictly positive for all time and equal to the entropy production in the system due to finite driving speeds. For overdamped systems, the entropy production has been shown to be related to the L2- Wasserstein distance36,37,39 between specified initial and final distributions. As we have emphasized, our problem involves instead changing a potential U to a potential V in a finite time. However, the structure is similar46,80.

It is easy to show in certain limits that the time-dependent terms in Eq. (30) are indeed related to the L2- Wasserstein distance. If we carry out a large-τ expansion on the time-dependent terms, it is easy to see that W2 can be written as:

In this limit the τ-dependent term can be expressed in terms of the square of the L2- Wasserstein distance between two Gaussians, where one of the Gaussians is simply the Boltzmann distribution in the V-trap while the other is a Gaussian in a modified shallow trap with variance Dζ2tU. This is the Gaussian projection of the time-average nonequilibrium state as mentioned in Subsection “Information-geometric interpretation”.

When ζ2 = 1 (which is the limit when Pta,U(x) → Peq,U(x)), the second term in Eq. (31) vanishes and the third term simplifies to the square of the L2-Wasserstein distance between the two Boltzmann distributions in the harmonic potentials U and V45. In this limit Eq. (31) takes on the form expected from the Jarzynski equality81 which connects in this context, the expected value of the work to the variance58. It is interesting that Eq. (31) has this form for any value of ζ whereas the Jarzynski equality holds strictly when starting from equilibrium.

In the opposite limit of \({\zeta }^{2}=\frac{{t}_{V}}{{t}_{U}}\) it is easy to see from both Eqs. (30) and (31), that the τ-dependent terms entirely vanish. This is consistent with the interpretation of this limit as the trivial case of vanishing exploration duration, as also mentioned earlier.

The instantaneous limit τ → 0 can also be taken in Eq. (30). In this case one recovers Eq. (19a). Details of the limits as well as the derivation of Eq. (30) are given in Supplementary Note S4.

In all of the above, the out-of-equilibrium nature of the initial state is parametrized via ζ which is itself a function of the strength of potentials U and V as well as the distribution of durations in the exploration phase f(t1) [Eq. (10)]. To understand the role of f(t1) better, we plot Eq. (30) in Fig. 6a, for a Gamma distribution

where r〈t1〉 ≠ 1 corresponds to deviations from the Poissonian case. In the following, we fix the mean duration in the exploration phase 〈t1〉 = 1 and vary r. This changes the shape of the distribution f(t1) (Fig. 6b). In Fig. 6a we plot the mean work as a function of protocol duration. We see that, for all protocol durations, W2 increases with r. To relate this to the shape of f(t1), we see that \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{ < }=\int_{0}^{\langle {t}_{1}\rangle }dt\,f(t)\) grows as r decreases. This implies that large fluctuations which enable stochastic realizations with sub-mean exploration duration result in a lower work value while suppressing fluctuations in f(t1) results in higher work values. This is in line with our previous discussions on Eq. (25) which showed that the lesser the time in the exploration phase, the lower the value of W2. Indeed, when r → 0 the probability accumulates at zero (Fig. 6b), resulting in the same work as the bound in Eq. (25) (dot-dashed line in Fig. 6a). When r → ∞ in the Gamma distribution the fluctuations around the mean become vanishingly small, and we approach the limit of deterministic exploration durations. In Fig. 6a the dashed line shows the resulting work for the corresponding case.

a Mean work W2 as a function of resetting duration τ. Here the exploration durations t1 are drawn from a Gamma distribution f(t1) with different shape parameter r〈t1〉. The value of r, ζ2 as well as the sub-mean probability mass \({{\mathbb{P}}}_{ < }\) is reported. The dashed line shows the bound when r → ∞ (small fluctuations around mean), and the dot-dashed line r → 0 (small fluctuations around zero). b Corresponding probability density f(t1) for durations of the exploration phase. Vertical grey dashed-dotted line marks t1 = 〈t1〉. Parameters are set to tU = 4, tV = 0.5 and 〈t1〉 = 1.

Conclusions

We have investigated the connections between the thermodynamic cost of an experimental procedure which has been used to implement resetting14,15,16 and earlier well studied problems of information erasure70,78 and geometric measures of optimal protocols that minimize work or heat in overdamped stochastic systems32,34,36,37,39,45,80. The problem we study is very similar to those studied in the above contexts, but a few important distinguishing aspects are the out-of-equilibrium nature of the system we study, the moment generating function of work from which we can, in principle, obtain all moments of the work for this system, as well as the explicit expression we obtain for the optimal work Eq. (30) which holds for all protocol durations τ and not just in the slow and fast limits as often studied.

We see from the expressions for the optimal work that at late times (31) appears to be the square of a L2-Wasserstein distance between two Gaussians, one of which has a variance Dζ2tU. The non-dimensional length ζ is a quantifier of the out-of-equilibrium initial state at the start of the resetting protocol and itself depends on both potentials U and V as well as the waiting time f(t) in a non-trivial manner [Eq. (10)]. In addition this length scale quantifies the variance of the projected state π[Pta,U](x). This seems to suggest that, at least for some results, we can replace our time-averaged non-equilibrium state Pta,U by a Gaussian with the same mean and variance, if all manipulations are only done via harmonic traps. It would be interesting to see how general this result is and whether it translates to other non-harmonic potentials.

Investigating optimal protocols further in the context of the erasure of out-of-equilibrium states is a very interesting direction to pursue. In particular, it would be very illuminating to understand if there are trade-offs between minimizing the mean work and minimizing the variance67,71 of the work done or the heat dissipated and if this results in phase-transitions in protocol space67. It would also be interesting to understand if there are cases when these protocols can be non-monotonic as observed in46. Investigating the so-called thermodynamic metric structure of the optimal-protocol-parameter space40,43,82,83 is yet another interesting direction to pursue, as is also the study of optimal transport in discrete cases84.

Finally, coming back to the context of resetting, it is very interesting to also understand thermodynamic costs when there is an absorbing barrier. Such an analysis has been done in ref. 28, though resetting has been implemented there by considering a first passage excursion to a specific point in a trap ("first-passage resetting"), unlike in our case when resetting is accomplished when the Boltzmann distribution in the trap has been reached. It would be very interesting to carry out a similar analysis as done in ref. 28 for our case. The nature of optimal protocols in the presence of absorbing barriers is also very interesting to understand26,28.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author [D.G.].

References

Evans, M. R. & Majumdar, S. N. Diffusion with stochastic resetting. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 160601 (2011).

Evans, M. R., Majumdar, S. N. & Schehr, G. Stochastic resetting and applications. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 53, 193001 (2020).

Pal, A. Diffusion in a potential landscape with stochastic resetting. Phys. Rev. E 91, 012113 (2015).

Nagar, A. & Gupta, S. Diffusion with stochastic resetting at power-law times. Phys. Rev. E 93, 060102 (2016).

Majumdar, S. N., Sabhapandit, S. & Schehr, G. Dynamical transition in the temporal relaxation of stochastic processes under resetting. Phys. Rev. E 91, 052131 (2015).

Gupta, D. Stochastic resetting in underdamped Brownian motion. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2019, 033212 (2019).

Di Bello, C. et al. Partial versus total resetting for Lévy flights in d dimensions: similarities and discrepancies. Chaos 35, 043129 (2025).

Reuveni, S. Optimal stochastic restart renders fluctuations in first passage times universal. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 170601 (2016).

Evans, M. R. & Ray, S. Stochastic resetting prevails over sharp restart for broad target distributions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 134, 247102 (2024).

Landauer, R. Irreversibility and heat generation in the computing process. IBM J. Res. Dev. 5, 183 (1961).

Bennett, C. H. The thermodynamics of computation—a review. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 21, 905 (1982).

Fuchs, J., Goldt, S. & Seifert, U. Stochastic thermodynamics of resetting. Europhys. Lett. 113, 60009 (2016).

Busiello, D. M., Gupta, D. & Maritan, A. Entropy production in systems with unidirectional transitions. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 023011 (2020).

Besga, B., Bovon, A., Petrosyan, A., Majumdar, S. N. & Ciliberto, S. Optimal mean first-passage time for a Brownian searcher subjected to resetting: experimental and theoretical results. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 032029 (2020).

Faisant, F., Besga, B., Petrosyan, A., Ciliberto, S. & Majumdar, S. N. Optimal mean first-passage time of a Brownian searcher with resetting in one and two dimensions: experiments, theory and numerical tests. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2021, 113203 (2021).

Goerlich, R. et al. Taming a Maxwell’s demon for experimental stochastic resetting. arXiv https://arxiv.org/abs/2306.09503 (2024).

Tal Friedman, O., Pal, A., Sekhon, A., Reuveni, S. & Roichman, Y. Experimental realization of diffusion with stochastic resetting. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 7350–7355 (2020).

Bérut, A. et al. Experimental verification of landauer’s principle linking information and thermodynamics. Nature 483, 187 (2012).

Bérut, A., Petrosyan, A. & Ciliberto, S. Detailed Jarzynski equality applied to a logically irreversible procedure. Europhys. Lett. 103, 60002 (2013).

Bérut, A., Petrosyan, A. & Ciliberto, S. Information and thermodynamics: experimental verification of Landauer’s erasure principle. J. Stat. Mech. Theory Exp. 2015, P06015 (2015).

Jun, Y., Gavrilov, Mcv & Bechhoefer, J. High-precision test of Landauer’s principle in a feedback trap. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 190601 (2014).

Gavrilov, Mcv & Bechhoefer, J. Erasure without work in an asymmetric double-well potential. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 200601 (2016).

Olsen, K. S., Gupta, D., Mori, F. & Krishnamurthy, S. Thermodynamic cost of finite-time stochastic resetting. Phys. Rev. Res. 6, 033343 (2024).

Olsen, K. S. & Gupta, D. Thermodynamic work of partial resetting. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 57, 245001 (2024).

Mori, F., Olsen, K. S. & Krishnamurthy, S. Entropy production of resetting processes. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 023103 (2023).

Singh, P. Emerging cost-time Pareto front for diffusion with stochastic return. N. J. Phys. 26, 103014 (2024).

Gupta, D. & Plata, C. A. Work fluctuations for diffusion dynamics submitted to stochastic return. N. J. Phys. 24, 113034 (2022).

Pal, P. S., Pal, A., Park, H. & Lee, J. S. Thermodynamic trade-off relation for first passage time in resetting processes. Phys. Rev. E 108, 044117 (2023).

Zulkowski, P. R. & DeWeese, M. R. Optimal finite-time erasure of a classical bit. Phys. Rev. E 89, 052140 (2014).

Boyd, A. B., Patra, A., Jarzynski, C. & Crutchfield, J. P. Shortcuts to thermodynamic computing: the cost of fast and faithful erasure. arXiv https://arxiv.org/abs/1812.11241 (2018).

Saira, O.-P. et al. Nonequilibrium thermodynamics of erasure with superconducting flux logic. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 013249 (2020).

Proesmans, K., Ehrich, J. & Bechhoefer, J. Finite-time Landauer principle. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 100602 (2020).

Giorgini, L. T., Eichhorn, R., Das, M., Moon, W. & Wettlaufer, J. S. Thermodynamic cost of erasing information in finite time. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 023084 (2023).

Aurell, E., Mejía-Monasterio, C. & Muratore-Ginanneschi, P. Optimal protocols and optimal transport in stochastic thermodynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 250601 (2011).

Aurell, E., Gawedzki, K., Mejia-Monasterio, C., Mohayaee, R. & Muratore-Ginanneschi, P. Refined second law of thermodynamics for fast random processes. J. Stat. Phys. 147, 487 (2012).

Zhang, Y. Work needed to drive a thermodynamic system between two distributions. Europhys. Lett. 128, 30002 (2020).

Dechant, A. & Sakurai, Y. Thermodynamic interpretation of wasserstein distance. arXiv https://arxiv.org/abs/1912.08405 (2019).

Chen, Y., Georgiou, T. T. & Tannenbaum, A. Stochastic control and nonequilibrium thermodynamics: fundamental limits. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 65, 2979 (2020).

Nakazato, M. & Ito, S. Geometrical aspects of entropy production in stochastic thermodynamics based on Wasserstein distance. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 043093 (2021).

Chennakesavalu, S. & Rotskoff, G. M. Unified, geometric framework for nonequilibrium protocol optimization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 107101 (2023).

Schmiedl, T. & Seifert, U. Optimal finite-time processes in stochastic thermodynamics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 108301 (2007).

Schmiedl, T. & Seifert, U. Efficiency at maximum power: an analytically solvable model for stochastic heat engines. Europhys. Lett. 81, 20003 (2007).

Sivak, D. A. & Crooks, G. E. Thermodynamic metrics and optimal paths. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 190602 (2012).

Plata, C. A., Guéry-Odelin, D., Trizac, E. & Prados, A. Optimal work in a harmonic trap with bounded stiffness. Phys. Rev. E 99, 012140 (2019).

Abiuso, P. et al. Thermodynamics and optimal protocols of multidimensional quadratic Brownian systems. J. Phys. Commun. 6, 063001 (2022).

Zhong, A. & DeWeese, M. R. Limited-control optimal protocols arbitrarily far from equilibrium. Phys. Rev. E 106, 044135 (2022).

Chen, X. et al. Fast optimal frictionless atom cooling in harmonic traps: shortcut to adiabaticity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 063002 (2010).

Chen, X., Lizuain, I., Ruschhaupt, A., Guéry-Odelin, D. & Muga, J. G. Shortcut to adiabatic passage in two- and three-level atoms. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 123003 (2010).

Schaff, J.-F, Song, X.-L., Vignolo, P. & Labeyrie, G. Fast optimal transition between two equilibrium states. Phys. Rev. A 82, 033430 (2010).

Schaff, J.-F., Capuzzi, P., Labeyrie, G. & Vignolo, P. Shortcuts to adiabaticity for trapped ultracold gases. N. J. Phys. 13, 113017 (2011).

Guéry-Odelin, D. et al. Shortcuts to adiabaticity: concepts, methods, and applications. Rev. Mod. Phys. 91, 045001 (2019).

Martínez, I. A., Petrosyan, A., Guéry-Odelin, D., Trizac, E. & Ciliberto, S. Engineered swift equilibration of a Brownian particle. Nat. Phys. 12, 843 (2016).

Carberry, D. M. et al. Fluctuations and irreversibility: an experimental demonstration of a second-law-like theorem using a colloidal particle held in an optical trap. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 140601 (2004).

Blickle, V. & Bechinger, C. Realization of a micrometre-sized stochastic heat engine. Nat. Phys. 8, 143 (2011).

Martinez, I. A. et al. Brownian carnot engine. Nat. Phys. 12, 67 (2016).

Chupeau, M. et al. Thermal bath engineering for swift equilibration. Phys. Rev. E 98, 010104 (2018).

Rosales-Cabara, Y. et al. Optimal protocols and universal time-energy bound in Brownian thermodynamics. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 012012 (2020).

Speck, T. & Seifert, U. Distribution of work in isothermal nonequilibrium processes. Phys. Rev. E 70, 066112 (2004).

Engel, A. Asymptotics of work distributions in nonequilibrium systems. Phys. Rev. E 80, 021120 (2009).

Minh, D. D. L. & Adib, A. B. Path integral analysis of Jarzynski’s equality: analytical results. Phys. Rev. E 79, 021122 (2009).

Speck, T. Work distribution for the driven harmonic oscillator with time-dependent strength: exact solution and slow driving. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 44, 305001 (2011).

Nickelsen, D. & Engel, A. Asymptotics of work distributions: the pre-exponential factor. Eur. Phys. J. B. 82, 207–218 (2011).

Abreu, D. & Seifert, U. Extracting work from a single heat bath through feedback. Europhys. Lett. 94, 10001 (2011).

Kwon, C., Noh, J. D. & Park, H. Work fluctuations in a time-dependent harmonic potential: rigorous results beyond the overdamped limit. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 88 6, 062102 (2013).

Ryabov, A., Dierl, M., Chvosta, P., Einax, M. & Maass, P. Work distribution in a time-dependent logarithmic-harmonic potential: exact results and asymptotic analysis. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 46, 075002 (2013).

Manikandan, S. K. & Krishnamurthy, S. Asymptotics of work distributions in a stochastically driven system. Eur. Phys. J. B. 90, 1 (2017).

Solon, A. P. & Horowitz, J. M. Phase transition in protocols minimizing work fluctuations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 180605 (2018).

Manikandan, S. K. & Krishnamurthy, S. Exact results for the finite time thermodynamic uncertainty relation. J. Phys. A Math. Theor. 51, 11LT01 (2018).

Ciampini, M. A. et al. Experimental nonequilibrium memory erasure beyond landauer’s bound. arXiv https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2107.04429 (2021).

Esposito, M. & den Broeck, C. V. Second law and Landauer principle far from equilibrium. Europhys. Lett. 95, 40004 (2011).

Watanabe, G. & Minami, Y. Finite-time thermodynamics of fluctuations in microscopic heat engines. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, L012008 (2022).

Rolandi, A., Perarnau-Llobet, M. & Miller, H. J. Optimal control of dissipation and work fluctuations for rapidly driven systems. N. J. Phys. 25, 073005 (2023).

Gomez-Marin, A., Schmiedl, T. & Seifert, U. Optimal protocols for minimal work processes in underdamped stochastic thermodynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 129, 024114 (2008).

Gupta, D., Large, S. J., Toyabe, S. & Sivak, D. A. Optimal control of the f1-atpase molecular motor. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 13, 11844 (2022).

Chatterjee, M., Holubec, V. & Marathe, R. Optimal constrained control for generally damped Brownian heat engines. arXiv https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.19124 (2025).

Davis, L. K., Proesmans, K. & Fodor, É. Active matter under control: Insights from response theory. Phys. Rev. X 14, 011012 (2024).

Gupta, D., Klapp, S. H. L. & Sivak, D. A. Efficient control protocols for an active Ornstein-Uhlenbeck particle. Phys. Rev. E 108, 024117 (2023).

Parrondo, J. M., Horowitz, J. & Sagawa, T. Thermodynamics of information. Nat. Phys. 11, 131 (2015).

Kolchinsky, A. & Wolpert, D. H. Work, entropy production, and thermodynamics of information under protocol constraints. Phys. Rev. X 11, 041024 (2021).

Blaber, S. & Sivak, D. A. Optimal control in stochastic thermodynamics. J. Phys. Commun. 7, 033001 (2023).

Jarzynski, C. Equilibrium free-energy differences from nonequilibrium measurements: a master-equation approach. Phys. Rev. E 56, 5018 (1997).

Wadia, N. S., Zarcone, R. V. & DeWeese, M. R. Solution to the Fokker-Planck equation for slowly driven Brownian motion: emergent geometry and a formula for the corresponding thermodynamic metric. Phys. Rev. E 105, 034130 (2022).

Ito, S. Geometric thermodynamics for the Fokker-Planck equation: stochastic thermodynamic links between information geometry and optimal transport. Inf. Geom. 7, 441–483 (2023).

Van Vu, T. & Saito, K. Thermodynamic unification of optimal transport: thermodynamic uncertainty relation, minimum dissipation, and thermodynamic speed limits. Phys. Rev. X 13, 011013 (2023).

Acknowledgements

All the authors are very grateful to Satya Majumdar and Sergio Ciliberto for inspiring discussions on this problem during the Nordita conference “Measuring and Manipulating Non-Equilibrium Systems” in Stockholm (14–24, October, 2024). S.K. would also like to thank Patrizia Vignolo for an interesting discussion during the Indo-French workshop on “Classical and quantum dynamics in out of equilibrium systems", held at ICTS, Bengaluru, Dec 16th–20th, 2024. D.G. gratefully acknowledges the financial support provided by NORDITA and Stockholm University, as well as the support from the Special Research Fund (BOF) of Hasselt University (BOF number: BOF24KV10) during the academic visit in May–June 2024, which facilitated this collaboration. D.G. and K.S.O. acknowledge support from the Alexander von Humboldt foundation. S.K. acknowledges the support of the Swedish Research Council through the grant 2021-05070.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Stockholm University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: D.G. and S.K. Simulations: D.G. Analytical calculations: D.G., K.S.O. and S.K. Writing: D.G., K.S.O. and S.K.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Physics thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gupta, D., Olsen, K.S. & Krishnamurthy, S. Thermodynamic cost of recurrent erasure. Commun Phys 8, 355 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02277-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42005-025-02277-w

This article is cited by

-

Harnessing non-equilibrium forces to optimize work extraction

Nature Communications (2025)