Abstract

Meeting targets under SDG 11 depends on qualitative improvements implemented through planning and design processes. In many less developed countries (LDCs), the upgrading of informal settlements has potential to make significant gains towards SDG 11, but the allocation of limited resources must be targeted appropriately. This paper presents an empirical method for determining the prioritization of settlements for upgrading as part of a national informal upgrading policy in Rwanda. The study constructs an assessment model considering national policies, urban resilience strategies, and progress towards SDG 11 using data that is publicly available or analysable through GIS applications. It proposes that the ease of use of the model and alignment with larger development strategies allows for prioritization of specific settlements for resourcing, highlighting areas of concern from which implementable projects may be developed. Similar models may be applicable to other sub-Saharan African countries and/or other urban upgrading efforts in LDCs.

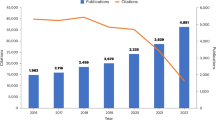

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Making “cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable”1 is among the more difficult of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) to benchmark success against because its targets are relative, subjective, or both. Although quantitative indicators are given, their effectiveness in measuring qualitative conditions is debatable2. Much of the progress towards SDG 11 depends on the interpretation of safety, adequacy, affordability, inclusivity, and a slew of other subjective terms which populate the language of the targets. Appropriate measurements are particularly difficult in the global South, where informal settlements are of greater prevalence and data collection often more challenging3.

Perhaps counterintuitively, these somewhat shapeless targets under SDG 11 have some potential to give urban (and to a lesser extent, architectural) design considerations a substantive role4,5 in clarifying the definitions of the targets and creating pathways towards achievement. Much-needed local specificity can be applied to assessments and potential indicators6, if local evaluation frameworks can be developed.

In contrast to many of the other goals, SDG 11 is therefore not driven primarily by broad political aims, but by trans-sectorial physical implementation. On its own, sound policy is ineffective without adequate implementation, and sensible design is insignificant if untethered to larger development strategies. This mutual dependency of design criteria with coherent SDG 11 development goals results in a nexus of influence between policy and design which can only yield results if the targets are collectively considered as an interconnected network7,8, informed by inclusive and contextually relevant data collection4, rather than as individualized measurements.

At the time of the last Rwandan census, 61.3% of the urban population lived in informal settlements9,10. The National Strategy for Transformation (NST1), which is aimed at domesticating the SDGs, states a goal to reduce this to 52% by the end of this year11. While the upgrading of informal areas has the potential to make gains towards most of the SDG 11 targets, the problem is immense and resources comparatively minute, so the allocation of finances and resources towards informal settlements must be carefully considered. Despite a plethora of policy initiatives, no clear guidance on the prioritization of interventions is available.

At issue, then, is that criteria and methods for distributing the limited available resources for informal settlement upgrading are often unclear. This lack of clarity leaves space to manoeuvre, but not always in positive ways: the process can be subject to political whims, undue influence, or in extreme cases, outright malfeasance. Political pitfalls aside, even well-intentioned investments may not be best placed if there is no clear hierarchy of considerations promoting the systems thinking sometimes lacking in urban development decision-making12 and essential to concepts of sustainability13 advanced by the SDG 11 targets. If the resourcing of projects is not directly tied to a holistic vision of sustainable and resilient development, collective impact is diminished. Addressing this requires systematically tying the targets to resource allocation in ways that are most likely to achieve them. Investment itself does not beget sustainability; much depends on the detailed implementation, and the end goals of the resourcing process must be clear and transparent.

While formulaic approaches always carry some risk of inadequate contextual adaptation, and design nuances are of equal importance, a systematic identification of problem areas and goals with measurable benchmarks is needed to help steer both development decisions and design implementation requirements (which are intrinsically linked to each other) towards a more sustainable and resilient urbanism. This paper presents a model and rationale for how such a framework was developed in Rwanda under the National Urban Informal Settlements Upgrading Implementation Programme (NUISUIP), for which the secondary author of this paper served as lead technical advisor, and the primary author as a sub-consulting advisor in developing the framework presented here.

Results

The purpose of this study is to develop a process model, rather than to present final data. For this reason, the methodology and the results are somewhat fluid, and the reader may find it more informative to first review the ‘Method’ section below, only later returning to the results outlined here.

The Assessment Process

The method used in the NUISUIP utilizes a scoring system to rationalize priorities, degrees of need, and urgency in upgrading. Each settlement under consideration is assessed at national and urban levels (mirroring the monitoring needed for the SDG 11 indicators14), based on the policy-based priorities and mapping to be done at that level.

The national-level assessment is done first, determining an alignment of needs towards national development criteria. This is intended to be a rapid assessment capturing broad principles; it may be thought of as a form of shortlisting to determine settlements most in need of resourcing. Following the national assessment, the urban-level assessment is done, assessing settlements against more nuanced code requirements, urban planning, and urban design goals. The combination of the two assessments allows for a classification and hierarchical ranking of needs.

Applying Data to Development and Design Priorities

Within each level, a level score is made up of weighted parameters, which are categories of need relating both to objectives at the respective national/urban level, and (sometimes indirectly) to some of the targets of SDG 11. Each level is allocated a point value of 100, with 100 representing the most urgent need and strategically important score. Between the two levels, 200 points are possible.

What determines the score within each parameter is a set of indicators based on the specific data and calculations below. These are either measured against benchmarks, or are ranges of benchmarks which represent either best-case and worst-case scenarios, or simply better and worse conditions.

Each indicator is assigned a 0–4 score, with 0 representing a low priority for upgrading and 4 representing a high priority. In many cases, a 0 score indicates that a desired condition has already been met within the settlement, and thus upgrading is not a priority, while a score of 4 represents a serious need for upgrading due to a misalignment with policy goals, code requirements, or best practice standards used in the assessment. However, some metrics are meant to promote investment in areas which satisfy larger sustainable development strategies, such as promoting growth near existing urban centres and transport networks, avoiding sprawl, and avoiding socio-economic isolation. Indicators related to these are scored highly if the surrounding conditions are favourable, and are scored low if they are not, thereby prioritizing investments in areas which better align with SDG 11 objectives overall.

Parameters are made up of different numbers of indicators (and therefore achieve different sums of indicator scores), but the number of indicators does not necessarily relate to the degree of relative importance. For this reason, parameter scores are assigned a weight, making up a percentage of the total level score (100 points). This weighting is partially an adjustment to correct for the number of indicators relative to other parameters, but is also used to place additional hierarchical weight on certain parameters. While there is no objective means of determining this hierarchical weight, the proportional weight of each parameter was workshopped with stakeholders and aligned with policy initiatives. Parameters which indicate potentially life-threatening or otherwise catastrophic risks are weighted more heavily, as are parameters which connect to strategic development and policy targets across multiple policies.

National Level Parameters & Rationale

Definition of the indicators under each parameter is considerably more nuanced in the NUISUIP itself, but an overview of the scoring method requires a certain degree of brevity, so below is a succinct summary of the rationale, benchmarks, and SDG linkages of each indicator measured.

The “Environmental Risk” parameter seeks to mitigate dangerous or potentially calamitous environmental risks and issues. In Rwanda, this is often associated with flooding, erosion, and landslides. Indicators include:

-

Slope risk factor: benchmarked against the Kigali City Masterplan15 and National Informal Settlement Upgrading Strategy (NISUS)16, which have differing measurements of acceptable buildable land, with high slopes to be avoided. Settlements with higher proportions of area on steeper slopes are prioritized for upgrading, linked to SDG target 11.5.

-

Flood risk factor: flood, rainfall, and overlap hazards (defined in the ‘Method’ section below) are used to assess and reduce risks, contributing to SDG target 11.5. Settlements which have a high combined risk factor gain priority for upgrading and/or resettlement.

-

Stormwater management: The Rwanda Urban Planning Codes (UPC) requires all roads to be provisioned with stormwater channels17, but this is currently rare in informal settlements. The Kigali Citywide Slum Upgrading Strategy18 places a high priority for upgrading on any settlements which have less than 50% stormwater drainage along roads, and a medium priority for settlements with less than 50% of stormwater drainage along feeder roads. This is used as a benchmark. Settlements with lower proportions of streets with appropriate stormwater drainage are given a higher upgrading priority.

The “Socio-economic Marginalization” parameter steers investments towards the most impoverished settlements:

-

Poverty rate: Though more directly related to SDG targets 1.3, 1.4, 1.5, and 10.2, built environment patterns influence economic opportunities19 and support networks20. The NISUS prioritizes upgrading in areas with the direst poverty levels16 according to national standards, and the NST1 sets specific targets for poverty reduction21. If these targets are already met, settlements are not prioritized for upgrading.

The “Provision of Basic Services” parameter promotes the provisioning of basic infrastructure in underserved areas:

-

Reliable access to clean, potable water: Touching on SDG target 6.1, both the UPC17 and the NISUS16 requires accessible access points at a maximum distance of 250 m, with a maximum catchment of 2000 people; settlements not meeting this are prioritized for upgrading.

-

Access to improved sanitation: Similarly, but for SDG target 6.2, the UPC17 and NISUS16 set a maximum distance of 80 m and catchment of 250 people for public toilets, for those without improved sanitation at home. Upgrading is prioritized based on the degree to which this is met.

-

Access to electricity: Directly affecting SDG target 7.1, and indirectly 10.2, settlements with lower rates of access to electricity are the highest priorities for upgrading; near universal access is desired.

-

Access to solid waste disposal: A direct response to SDG target 11.6, standards are again set by the UPC17 and NISUS16 of a waste disposal point within 250 m of every resident; settlements not meeting this are prioritized for upgrading based on the degree of improvement needed.

The indicator scoring and formulaic assessment, as well as parameter weighting, is shown in Table 1. A summary of linkages between parameters, indicators, benchmarks and SDG targets is given in Fig. 1.

Urban Level Parameters & Rationale

Following the national-level assessment, which provides an overview of the alignment with policy initiatives and first indication of suitability for resource allocation, each major municipality is expected to assess settlements according to more detailed urban-level criteria.

The “Urban Condition” seeks to promote investment and development in areas already served by existing infrastructure and transport systems, and closer to higher density job centres, thereby promoting noon-motorized transport (NMT), social inclusion, and access to services:

-

Built-up space in surrounding area: Taking a holistic approach, this indicator looks not at the settlement itself, but a 500 m offset immediately surrounding it. Seeking to promote urban cohesion and discourage sprawl, it prioritizes upgrading that reconnects and integrates settlements into an existing urban fabric, thereby directly influencing SDG target 11.3. Given a design goal of approximately 30% of urban land allocated for streets22, and a design goal of public space in the vicinity of 15% of available land, 45% of the land area in any well-designed urban area is likely to remain unbuilt23, with 55% remaining available for development. In many parts of urban environments, plot coverage areas can dip as low as 25-30% and remain urban in character. 25% of the 55% of land available for development is equivalent to 13.75% of total land area; this indicator rounds up and uses 15% of built-up space as the benchmark for a reasonably dense urban environment.

-

External connectivity: Promoting better-connected settlements (and thus, indirectly, SDG targets 11.2, 11.3, and 11.a), the metric on this indicator is the external connectivity ratio: the average distance between primary or secondary distributor roads entering/exiting the settlement24. There is no regularized international standard for this; a benchmark of 400 m/node is established as adequate connectivity, and settlements more poorly connected are prioritized for upgrading.

-

Internal connectivity: Promotes connectivity within the settlement, touching on the same SDG targets as external connectivity. The Street Connectivity Index (SCI) defined by the UN City Prosperity Index (CPI)25 is used as a benchmark; less connected settlements are prioritized for upgrading.

-

Physical accessibility of plots: Seeks to ensure proper access and servicing of plots from a public right of way. 100% accessibility is expected; settlements not meeting this are prioritized for upgrading.

The “Density and Built Environment Quality” parameter promotes positive synergies between densities and public spaces:

-

Settlement density: Investment in settlements already at a benchmark density but in need of upgrading are prioritized, contributing to the interconnected systems which benefit from density and directly impacting SDG targets 11.2, 11.3, and indirectly 11.a. The UN-Habitat benchmark23 of at least 150 p/ha is used as a standard to be worked towards.

-

Overcrowding: Acts as a counterpoint to density, seeking to avoid inhumane, unsanitary, or otherwise dangerous living conditions, impacting on housing (SDG target 11.1). International standards26,27, to which the NISUS16 refers and harmonizes, consider living conditions in which less than 3.5m2/p of covered living space is available to be overcrowded. If overcrowding is present, upgrading is prioritized.

-

Public open space (excluding roads): Counteracts a lack of prioritization of public space in Rwanda28 and promotes social interaction and an overall healthier environment29 by prioritizing settlements which lack open spaces (excluding streets) within 400 m of homes25 for recreational use. This indicator directly impacts SDG target 11.7.

-

Green area per capita: There is ever-mounting evidence that access to green areas in dense cities has a positive correlation with mental and physical health30,31,32,33,34; this indicator prioritizes greenery in both public and private spaces, working towards the benchmark of 15m2 of green area per person from the UN CPI25. Settlements far below the benchmark in green area per capita receive the highest priority.

The indicator scoring and formulaic assessment, as well as parameter weighting, is shown in Table 2. A summary of linkages between parameters, indicators, benchmarks and SDG targets is given in Fig. 2.

Classification

Ultimately, the purpose of the assessment is to create a simple but rigorous methods to empirically (or at least objectively) determine priorities for allocating limited resources towards upgrading and leverage the urban development and resilience strategies being promoted through public policy.

At both levels, national and urban, the sum of weighted parameter scores totals 100; the higher the score, the greater the alignment with national policy and strategic goals. Settlements may then be ranked according to their national level score, which can be used to guide funding and resource allocation at the national level. A classification of this can be understood as shown in Table 3.

Following the national level rapid assessment described above, particular settlements can be identified as higher priorities for upgrading, and resources allocated accordingly. Once the highest priority settlements are known, a more specific assessment to be done at the urban level can align the priorities with additional criteria not defined at the national level. Similar to the national level score, the weighted parameters at urban level sum to 100, with higher scores indicating better alignment with specific characteristics of each city, and with preferential development strategies. The urban level classification can be understood, as shown in Table 4.

While this assessment system can generate a total ‘score’ for each settlement by summing the level scores, this is only one of a possible set of influences in decision-making about resource allocation towards upgrading. Other unquantifiable factors, such as alignment with major infrastructure projects, may also shape the resourcing process.

As a numerical assessment, ease of use can be facilitated by visualizing the scoring, offering a brief overview of how settlements compare to each other (see Fig. 3 below). The development of visual diagrams highlighting the largest areas of need according to the indicators is programmed into the assessment tool, and can be used to clearly see both the relative needs overall, and the specific areas of need across multiple settlements.

Case Studies

Three settlements evaluated as case studies in the development of this assessment tool are indicative of ways in which the quantitative assessment can be used to understand areas of need and formulate specific interventions to address them.

In the visual sunburst diagrams, the colours represent the scale of the assessment (national or urban), the parameters are labelled, and the wedge-shaped radial bursts each represent one indicator within the parameters. The width of the radial bursts is determined by the weight of the indicator relative to the level score. The concentric rings of the radial burst represent the 0-4 scores of the indicators within each parameter. The more segments filled in, the greater the need for that indicator.

In the test cases shown in Fig. 3 below, a number of determinations can be made easily and visibly, even without scrutinizing the detailed data. First, it is clear the Settlement 1 has the highest overall score, and therefore the greatest need for upgrading, while Settlement 3 has the lowest overall score, and thus the lowest need. This represents one possible way of allocating resources: identifying areas of upgrading by settlement and then launching projects within those areas. However, the diagrams also show other information by indicator which may also be used to develop upgrading projects. For instance, all three settlements show significant needs for reliable access to clean, potable water, and for access to improved sanitation. Similarly, both Settlement 1 and Settlement 2 show high risks due to the slope risk factors. It is thus conceivable to launch upgrading projects around those specific shortcomings, inclusive of all settlements which indicate those needs, rather than creating interventions settlement-by-settlement. In this way, the conceptualisation of upgrading projects remains flexible, even if the data is rigidly quantitative.

Discussion

The tool used to develop the Rwanda NUISUIP is meant to define a logic and systematic framework for adoption and, over time, adaptation, to better align the resources invested in informal settlements upgrading to larger urban resilience strategies. Even in a rapidly developing society, the pace of change inherent to urban development and design means that empirical measures of success (or failure) will take years – possibly decades – to fully assess. Long-term tracking is needed. However, several key points can be made at this early stage.

The first is that in a defined framework such as this, goal-setting and protocols must be coupled not only with data-driven metrics, but also with design-based ones in order to create a holistic strategy35. The targets and implied metrics defined under SDG 11 are, by themselves, inadequate to directly inform design, but they can – and should – be linked to a strategic framework with an urban-resilience and sustainable design-based focus36,37,38. Put another way, a decision-matrix which informs the resourcing and implementation requirements of informal upgrading may be informed by the SDG 11 targets as indirect, complementary means of attainment. In the case of the NUISUIP, 7 of the 10 targets are either directly or indirectly affected by the strategic framework, and one of the targets excluded from that accounting is at least partially achieved separately by the very existence of an informal settlements upgrading policy in the first place. Namely, targets 11.1, 11.5, 11.7 are directly influences through indicators of housing qualities, environmental risks, and open and green space provision, respectively. Targets 11.2, 11.6, 11.a, and 11.b are indirectly influenced through promotion of appropriate urban densities, promotion of walkability and greening of public spaces, the support of intervention planning through the assessment, and remediation of environmental risks, respectively. Target 11.3, which promotes inclusive and sustainable urbanization, is part of the objective of this assessment tool, and is thus separately influenced. Target 11.c is international in nature, so cannot be accomplished through a national- and urban-level assessment. Only target 11.4 goes unaddressed in this assessment model. From this standpoint, the impacts of the described method on SDG 11 are clearly present, though not immediately assessable.

This assessment tool was constructed specifically for Rwanda; adaptability to other contexts is possible if guided by relevant expertise. Existing policy initiatives and development plans – where they exist and, especially, where they align with SDG targets – must be integrated into the assessment.

Although it is too early to measure long-term success of the rollout, objective methods to assess upgrading needs can at least partially demystify the resource allocation processes for informal settlement upgrading while simultaneously highlighting core areas of need, which implementation projects may be conceptualised around.

Adaptation may also be made over time as initiatives and policies change. The prioritization of criteria is, at least hypothetically, adjustable, and can (and should) be scrutinized and edited over time. It is perhaps less important to ‘get it right’ in the first deployment than to understand the overall strategic intent and assess whether the rollout of projects generated through this method are achieving that intent. Defining this allows for later evaluation as to whether the hierarchies, priorities and achievements towards SDG 11 are correctly defined and, if necessary, adjust them over time.

The reliance on a strategic framework of decision-making related to project development and design does carry inherent risks of inflexibility and/or inability to adequately adapt to changing circumstances over time. However, both of these risks can be mitigated through periodic updates to the hierarchical weighting of strategic planning and design factors (assuming problematic issues are appropriately diagnosed, and adequate measures taken to redesign the framework). The hierarchies placed on the categories of assessment in the NIUSUIP framework are, to some extent, judgment calls which are open to critique and can (and probably should) be refined over time, particularly as or when results can be better measured empirically.

Ease of use is also important. A strategic directionality towards SDG 11 goals – or any resilience-based framework for that matter – does little good if the use and implementation is unnecessarily complex, costly, or too time-consuming to adhere to, or if it is overly dependent on institutional knowledge which may be shaky in public agencies prone to staff turnover and bureaucratic shuffling of personnel. It was with this in mind that the visual representation of needs and opportunities became a key component of the framework: a clear indication of issue areas can be summarized and easily understood, unlocking entry points into the more detailed data and encapsulating core areas of need which may contribute to specific project development. Policies intended to work towards SDG 11 can only be effective if they provide a coherent vision and clear outputs for the projects which stem from them.

The NUISUIP framework also contained an additional, finer-grained, settlement-level assessment, which could be used to diagnose specific needs and define specific actions, thereby allowing the assessment to directly contribute to the formation of projects which may be implemented. Since the focus of this paper was the relation of the assessment model to SDG 11, this settlement-level assessment was left out; it may be the subject of a future paper.

Much of the data to be collected is dependent on reasonably accurate census information and, especially, GIS data sets. Although the operations needed to be performed can be completed straightforwardly by anyone with moderate GIS expertise (and an instruction manual is included in the NUISUIP for this purpose), these operations can only retrieve information from what is already available in the datasets. In contexts where the necessary information is lacking, a pre-assessment would need to take place to obtain a baseline dataset, which makes the assessment tool somewhat more cumbersome. This limitation may be a challenge, but with improving remote sensing techniques and the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into the data collection processes, such an impediment may be better overcome in the future.

Many of the benchmarks used for the indicators are derived from national or municipal policies, frameworks, or regulations. Such documents will vary from place to place, and in some contexts may not provide obvious benchmarks, or may not relate to the SDGs in any meaningful way. For this reason, significant expertise would be needed to adapt the benchmarks and, if necessary, redevelop the scoring of the indicators to better relate to local contexts. Where policies and plans have shortcomings in their alignment with sustainable development principles, these gaps must be identified, critiqued, and benchmarked measured against alternative benchmarks, a process which would likely require both relevant expertise and political will, both of which may prove challenging in certain contexts.

When adjusted to suit local contexts, the appropriate inclusion or exclusion of indicators may be debatable, and the benchmarks indicators are measured against can be contested, potentially raising some ethical concerns around the imposition of certain political agendas. The objectivity of the assessment tool itself blunts this criticism to some extent, as the measurements are transparent, verifiable, and open to public scrutiny. However, public scrutiny depends on civic engagement, which should not be assumed. A good starting point in identifying appropriate indicators in other contexts would be an overarching, participatory, visioning process in which a broad coterie of residents is invited to express their priorities. This would then need to be coupled with technical analyses of major risk factors in the planning process. Compiled priorities may then be taken back to residents for conceptual validation before appropriate indicators are assigned.

Methods

Measurements & Indicators: A Framework for Resource Informal Upgrading

In the NUISUIP, an analytical assessment tool was created to rationalise how limited resources may best be allocated to informal settlement upgrading. The assessment tool uses data from readily available sources (GIS data, census data, climate data), and uses it to shape priorities.

The method used does not invent any new metrics. Rather, it uses a compilation of empirically measured direct inputs, pre-established formulaic assessments, and some assessment factors unique to the NUISUP). The inputs are run through a hierarchical weighting (loosely tied to SDG 11), which categorizes settlements according to national and urban development strategies, scoring them against priorities in both absolute and relative terms. This scoring system is made up of:

-

Indicators, which are specific, measurable issues that help determine risk factors and/or priorities in selecting settlements for upgrading, and which have a specific metric;

-

Parameters, which are broader categories of issues made up by one or more indicators and are intended to align with policy and/or strategic initiatives;

-

Levels, namely the national and city levels, which each have their own parameters carrying a different weight of influence based on degrees of importance.

Once a specific settlement has been prioritized for resourcing, the assessment tool also identifies settlement-level needs and opportunities which may define the specific projects and interventions needed to contribute to more sustainable upgrading, though this part of the process is not detailed in this paper. Overall, the goal of the scoring system is to accurately reflect pre-defined priorities that may help propel urbanization in general, and informal settlements in particular, towards development patterns that align with some of the parameters of SDG 11, work towards achieving national strategies, policies and standards, and selectively intervene based on identified characteristics.

Data Utilized

At national and urban levels, the basic data needed (in Rwanda) is publicly available from pre-existing sources, thus ensuring ease of use and simplicity of compilation. Availability of similar data elsewhere may differ, but adjustment to local conditions was considered as part of the framework. The data belongs to six categories:

-

1.

Area measurements, available through GIS data and/or simple GIS-based analysis, and ultimately used to determine the degree of environmental risks, provision (or lack of) public space, and density versus overcrowding assessments (both within an immediately surrounding the settlement). Availability of the GIS data is necessary, and may be lacking in other contexts. Once the relevant data is obtained, all operations required to extract relevant information can be performed with only moderate-level GIS expertise.

-

2.

Population & income measurements, available through a basic GIS assessment and/or census data, and ultimately used to determine densities and assess social facility needs. While census data may not be precisely accurate, it is generally available in all contexts.

-

3.

Household measurements, also available through GIS and census data, and ultimately used to assess infrastructural and socio-economic needs.

-

4.

Climate measurements taken from readily available climate data and used in environmental risk assessments. The data used here in this category is readily available everywhere.

-

5.

Infrastructure & settlement features measurements, available through a GIS assessment, is used to determine degrees of connectivity in promotion of non-motorized and public transport. The information in this category is quite unique to Kigali, using national and local benchmarks to generate measurable criteria. This data category would need to be revised and linked to relevant local benchmarks for wider application.

Additional settlement-tier data is also used in the assessment to assess needs and generate opportunities for interventions which may guide project creation and their terms of reference. However, the settlement-tier assessment only begins once a decision to avail resources to a particular settlement has been made, so is beyond the scope of this paper.

For ease of identification, each data point to be collected is given a notation, which is used in later numerical computations. The full list of data utilized is given in Table 5.

Calculation

To assess upgrading needs, raw data must be put into useful forms. In some cases, this requires intermediary calculations which move data closer to what is finally being assessed. Many of these intermediary calculations are straightforward percentages or units per area, units per population, etc. However, some – such as assessing the risks associated with natural disasters (in this case, flooding and landslides are the core focus) – require creating a numerical means of assessing risk. Potential risks from measurable elements, such as slope and rainfall, are combined based on their degree of severity to create a risk factor (R). Other risk factors, such as flooding, are combinations of multiple data inputs (slope, rainfall, and overlap of steep slopes within flood plains). For these, a hazard factor (Z) is first generated using similar means, with increasing risk being weighted linearly or exponentially more than lower risks. These hazard factors are used to compile a flood risk factor (Rf).

Distances and catchment populations of residents to basic services such as water collection points, public toilets, and waste collection points are dictated by the Rwanda Urban Planning Code (UPC)17, itself heavily influenced by SDG 11. For these items, existing conditions are benchmarked against the UPC. Clearly, different localities would need to adjust these benchmarks based on local requirements (if they exist), or borrow from international best practice standards. Urban form and connectivity – which directly influences NMT and public transportation (SDG 11.2) – is assessed against measures from UN Habitat’s City Prosperity Index (UN CPI)25; thus calculations for items such as street connectivity, nodal intersections, and access to transport are based on the CPI.

Specific calculations, the basis from which they are made, and the formulas necessary to make them, are given in Table 6.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Sustainable Development Goal 11, nd. [Online]. Available: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal11. [Accessed 26 Nov 2024].

Thomas, R., Hsu, A. & Weinfurther, A. Sustainable and inclusive – Evaluating urban sustainability indicators’ suitability for measuring progress towards SDG-11. Environ. Plan. B: Urban Analytics City Sci. 48, 2346–2362 (2020).

Musango, J. K., Currie, P., Smit, S. & Kovacic, Z. Urban metabolism of the informal city: Probing and measuring the ‘unmeasurable’ to monitor Sustainable Development Goal 11 indicators. Ecol. Indic. 119, 106746 (2020).

Klopp, J. M. & Petretta, D. L. The urban sustainable development goal: Indicators, complexity and the politics of measuring cities. Cities 63, 92–97 (2017).

Hoşkara, Ş. and Koç, Ö. S. The Role of Urban Design in Achieving the UN SDGs. in An Agenda for Sustainable Development Research, W. Leal Filho, A. Salvia and C. Portela de Vasconcelos, Eds., Cham, Springer, 2024.

Giles-Corti, B., Lowe, M. & Arundel, J. Achieving the SDGs: Evaluating indicators to be used to benchmark and monitor progress towards creating healthy and sustainable cities. Health Policy 124, 581–590 (2020).

Blanc, D. L. Towards integration at last? The sustainable development goals as a network of targets. Sustain. Dev. 23, 176–187 (2015).

Scharlemann, J. P. W. et al. Towards understanding interactions between Sustainable. Sustain. Sci. 15, 1573–1584 (2020).

UN-Habitat, “Rwanda,” nd. [Online]. Available: https://unhabitat.org/rwanda. [Accessed 26 Nov 2024].

Ministry of Infrastructure, “Forward Looking Joint Sector Review Report, Fiscal Year 2022/2023: Urbanization and Human Settlement Sector,” Government of Rwanda, Kigali, 2022.

Republic of Rwanda, “7 Years Government Programme: National Strategy for Transformation (NST1) 2017-2024,” Minecofin, Kigali, 2017.

Allen, C., Metternicht, G. & Wiedmann, T. Initial progress in implementing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): a review of evidence from countries. Sustain. Sci. 13, 1453–1467 (2018).

Donaires, O. S., Cezarino, L. O., Ferreira Caldana, A. C. & Liboni, L. Sustainable development goals – an analysis of outcomes. Kybernetes 48, 183–207 (2019).

United Nations, “Tracking Progress Towards Inclusive, Safe, Resilient and Sustainable Cities and Human Settlements: SDG 11 Synthesis Report,” United Nations, New York, 2018.

Surbana Jurong Consultants, Kigali Master Plan 2050, Kigali: Ministry of Infrastructure, 2019.

Ministry of Infrastrcuture, Republic of Rwanda, National Informal Settlment Upgrading Strategy, Kigali: Mininfra, 2015.

Government of Rwanda, Rwanda Urban Planning Code, Official Gazette no. special of 16/04/2019, 2019.

Rwanda Housing Authority, Profiling and providing indication of the status quo and trends in informal settlements and proposed mechanisms for their upgrading in Kigali City, Kigali: RHA, 2013.

G. Scruggs, Integrating the SDGs in Urban Project Design: Recommendations from the Global Future Cities Programme, United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat), Nairobi, 2022.

Uwizeye, D., Irambeshya, A., Wiehler, S. & Niragire, F. Poverty profile and efforts to access basic household needs in an emerging city: a mixed-method study in Kigali’s informal urban settlements, Rwanda. Cities Health 6, 98–112 (2022).

Republic of Rwanda, 7 Years Government Programme: National Strategy for Transformation, Kigali: Government of Rwanda, 2017.

UN-Habitat, The relevance of street patterns and public space in urban areas, United Nations Human Settlements Programme, Nairobi, 2013.

UN-Habitat, A new strategy of sustainable neighbourhood planning: Five principles, United Nationals Human Settlements Programme, Nairobi, 2016.

Yigitcanlar, T., Kamruzzaman, M. & Teriman, S. Neighborhood sustainability assessment: Evaluating residential development sustainability in a developing country context. Sustainability 7, 2570–2602 (2015).

UN-Habitat, “Measurement of City Prosperity: Methodology and Metadata,” United Nations Human Settlments Programme, Nairobi, 2016.

Econometrica, Inc., Measuring Overcrowding in Housing, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research, Washington, 2007.

World Health Organization, WHO Housing and Health Guidelines, World Health Organization, Geneva, 2018.

Gubić, I. & Baloi, O. Implementing the New Urban Agenda in Rwanda: Nation-Wide Public Space Initiatives. Urban Plan. 4, 223–236 (2019).

World Health Organisation, Health indicators of sustainable cities: In the context of the Rio+20 UN Conference on sustainable development, WHO, Geneva, 2012.

Lee, A. C. & Maheswaran, R. The health benefits of urban green spaces: a review of the evidence. J. Public Health 33, 212–222 (2010).

Maas, J., Verheij, R. A., Groenewegen, P. P., de Vries, S. & Spreeuwenberg, P. Green space, urbanity, and health: how strong is the relation?,”. J. Epidemiol. Community Health 60, 587–592 (2006).

Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J., Khreis, H., Triguero-Mas, M., Gascon, M. & Dadvand, P. Fifty Shades of Green: Pathwat to healthy urban living. Epidemiology 28, 63–71 (2017).

M. P. White, I. Alcock, B. W. Wheeler and M. H. Depledge, Would You Be Happier Living in a Greener Urban Area? A Fixed-Effects Analysis of Panel Data, Psychological Science, vol. 24, 2013.

Yeh, C.-T., Cheng, Y.-Y. & Liu, T.-Y. Spatial characteristics of urban green spaces and human health: an exploratory analysis of canonical correlation. Int. Jounral Environ. Res. Public Health 17, 3227 (2020).

Abastante, F., Lami, I. M. & Gaballo, M. Pursuing the SDG11 Targets: The Role of the. Sustainability 13, 3858 (2021).

H. Shankavaram, J. Jhunjhunwala, R. Krishna and S. Ramanan, Urban Design as a Spatial Assessment Tool in Achieving SDG 11: Case of Bengaluru, India, in SDGs in teh Asia and Pacific Region, W. Leal Filho, T. Ng, U. Iyer-Raniga, A. Ng and A. Sharifi, Eds., Cham, Springer, 2023, 1-37.

T. O. Ajayi, A. T. Akinyemi and T. B. Akintunde, Cultural Design and Sustainable Architecture: Impact on SDG 11 and Urban Development, International Journal of Modern Research in Engineering and Technology, vol. 9, 2024.

M. Dennis, P. A. Cook, P. James, C. P. Wheater and S. J. Lindley, Relationships between health outcomes in older populations and urban green infrastructure size, quality and proximity, BMC Public Health, vol. 20, 2020.

Acknowledgements

This research stems from the development of the National Urban Informal Settlement Upgrading Implementation Programme, under the Rwanda Ministry of Infrastructure, funded by World Bank. Only the authors’ original contributions are used in this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.L.M. headed the research and conceptualization of the scoring method; G.G. developed the quantitative analysis and led the composition of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gantner, G., La Mantia, C. A Method for Resourcing Sustainable Cities in Rwanda Through Informal Settlement Upgrading. npj Urban Sustain 6, 17 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-025-00321-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-025-00321-w