Abstract

InSb nanoflags represent an interesting platform for quantum transport and have recently been exploited in the study of hybrid planar Josephson junctions. Due to the uncovered semiconductor surface, they are also good candidates for surface probe techniques. Here, we report Scanning Gate Microscopy (SGM) experiments on Nb-contacted InSb nanoflag-based Josephson junctions. In the normal state, sizable conductance modulation via the charged tip of the SGM is recorded. In the superconducting state, we report the application of Scanning Gate Microscopy to superconducting weak links, demonstrating the possibility of manipulating the supercurrent flow across a semiconductor-superconductor heterostructure at a local level. The experimental findings are consistent with theoretical predictions and establish a way of investigating the behavior of superconducting weak links. This raises the perspective of locally imaging the supercurrent flow, once the spatial resolution is significantly improved, e.g. by nano-sculpting the tip.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the last decades, a strong interest revolved around hybrid semiconductor/superconductor (SC) devices where the proximity effect can lead to a wide variety of phenomena. Among all, the possible emergence of topological states, such as Majorana modes, triggered huge efforts starting from the proposal based on hybrid SC-semiconducting nanowires with strong spin-orbit coupling1,2,3,4. More recently, planar Josephson junctions, where a 2D semiconductor is placed in between two SCs forming a super-normal-super (SNS) junction, emerged as an alternative platform to achieve non-trivial topological phases5,6,7,8.

Interestingly, in planar junctions, superconductors can be contacted laterally, retaining the semiconducting surface of the device uncovered, allowing for the investigation by spatially resolved techniques. Among all surface probe techniques, in the last twenty years, scanning gate microscopy (SGM) has proven itself to be successful in the study of semiconductor-based devices9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41. This technique combines surface and transport studies: an atomically sharp tip is used to perform local gating on a semiconductor. By current or voltage biasing the sample and recording its conductance response as a function of tip position, information can be obtained on the current density distribution in the sample as well as the presence, nature, and location of defects19,20,21,42,43. Electron transport in quantum wells9,10,11,12,13,16,18,19,20,21,22,23, two-dimensional materials, such as graphene17,24,25,26,27 and MoTe228, carbon nanotubes29,30,31, quantum dots32,33,34, quantum rings36, and nanowires37,44 has been investigated by SGM.

To date, only three SGM experiments have been performed on superconducting devices so far. In 2009, Huefner et al.35 investigated a superconducting single electron transistor based on an Al island, in a regime where no Josephson effect was present across the tunnel junctions connecting the dot to the electrodes. In 2020, Bhandari et al.38 imaged Andreev reflection in graphene in an architecture with a single superconducting electrode, by exploiting cyclotron motion to spatially separate the particles impinging on the electrode from those reflected by it. In 2024, Hegedüs et al.39 studied the effect of two-level defects as noise sources in superconducting qubits. To our knowledge there is so far no record of SGM experiments performed on superconducting weak links (SNS), such as hybrid SC-semiconductor Josephson junctions. Such hybrid structures have been intensively investigated by transport techniques, but it is still an open challenge to map and manipulate individual features in their supercurrent density distribution, e.g., Josephson vortices. Furthermore, superconducting junctions based on materials with large spin-orbit coupling (e.g., InSb) promise to host exotic topological phases, whose local manipulation would be a key step in the route toward topological quantum computation2. Therefore, assessing to local supercurrent density and visualizing electronic flow in hybrid devices by SGM can give relevant information also in the context of topological platforms.

We note that recently an alternative way of investigating supercurrent flow by scanning probe microscopy has been demonstrated: Chen et al. mapped the magnetic field distribution generated by the supercurrent in a Josephson junction via a scanning probe magnetometer based on a single nitrogen vacancy in diamond45. Despite its undeniable potential, which includes the possibility of mapping the supercurrent distribution in conditions different from criticality, this technique requires samples with high critical current densities to create a sufficiently strong magnetic field to be detected.

InSb nanoflags have recently sparked interest as a quasi-two-dimensional alternative to InSb nanowire-based devices46,47. Several groups have investigated high mobility InSb nanoflag-based devices, demonstrating gate tunable proximity-induced superconductivity48,49,50 as well as electrostatic control over spin-orbit interaction51,52, superconducting diode effect53, and half-integer Shapiro steps54. In these devices, the normal semiconducting region between the superconducting electrodes remains exposed, which opens the possibility for the application of the SGM technique.

In this paper, we report SGM measurements of InSb nanoflag-based Josephson junctions with Nb contacts, both in the normal and in the superconducting regime. These measurements represent to the best of our knowledge both the first SGM experiment on InSb nanoflags and, at the same time, the first SGM report on SNS devices, demonstrating local critical current modulation via the charged tip of the SGM.

Results

Experimental setup and SGM

Measurements have been acquired in a Janis bath cryostat equipped with a 3He refrigeration stage with a base temperature of 300 mK and a custom-made Attocube SGM. Both the electrical transport lines and the connections necessary for the operation of the microscope have been filtered to preserve the superconducting behavior of the devices under study55,56.

A typical device design is reported in Fig. 1a: it consists in a ~ μm-sized InSb nanoflag deposited on a highly conductive p-type Si(100) substrate, which serves as a global back gate. A 285 nm thick SiO2 layer covers the Si substrate as dielectric. The InSb nanoflags have a typical thickness of 100 nm. The nanoflag is contacted through two Nb electrodes46,50,53,54, separated by a gap about 200 nm long, i.e., the semiconducting region of the Josephson junction. Electrostatic control of the global behavior of the junction can be achieved by polarizing the back gate electrode with a voltage difference Vbg with respect to the grounded device. In the experiments, we have investigated the action of an additional gate electrode, the SGM tip, once it is placed in proximity to the junction and polarized with a voltage difference Vtip with respect to it. Details on the device fabrication are provided in Supplementary Section 1.

a Graphical representation of a Scanning Gate Microscopy experiment. The light blue section corresponds to the exposed semiconducting region of the nanoflag. b Conductance modulation of device SC6 versus back gate voltage. The back gate working point Vbg = 3 V is indicated by a red x. The numerical least squares fit of the rising slope in proximity to the working point with a linear model is indicated by the red dashed line. c Conductance map as a function of tip position acquired in lift-mode with a 60 nm tip offset with respect to the topography scan. Working point: Vtip = 10 V, Vbg = 3 V. d Conductance map acquired in the same conditions as (c), but with Vtip = −10 V. In (c) and (d), the device outline is indicated by the dashed yellow lines.

First measurements were performed at 77 K. At this temperature, the devices behave as conventional n-type field-effect transistors, as displayed by the conductance modulation curve shown in Fig. 1b. When the charged tip is placed close to the exposed semiconducting region of the junction, it modifies the local carrier concentration. This effect can be recorded by measuring the conductance across the device as a function of the tip position. SGM measurements have been performed in lift-mode (see Methods) by acquiring the in-phase component of the voltage difference across the junction via lock-in technique.

In order to enhance the effect of the tip, as working point a back gate potential of Vbg = 3 V has been set, where the change of sample conductance with back gate voltage is maximized, as shown in Fig. 1b. In Fig. 1c we report a conductance modulation map induced by a tip voltage of Vtip = 10 V. The location of the exposed region of the nanoflag is shown as a red area in the conductance map: once the positively charged tip gets sufficiently close to the device, it induces charge carrier accumulation in the InSb nanoflag, thereby enhancing its conductance. To demonstrate that this effect is caused by tip-induced charge carrier density modulation, SGM maps have been acquired with both positive and negative voltages applied to the tip (see Fig. 1c, d). As expected, while the positive polarization of the tip induces conductance enhancement, the negative polarization induces conductance reduction (blue area in Fig. 1d) once the tip is placed close to the exposed semiconducting region. We note that in both Fig. 1c, d the junction conductance recorded in the SGM scans is smaller than that corresponding to the working point in Fig. 1b. We attribute this effect to a shift in the position of the conductance modulation curve caused by the presence of the tip close to the device. In fact, the change in both tip-to-sample distance and Vtip involved in lift-mode operation can trigger charge-redistribution effects. However, the presence of this effect does not affect the analysis nor the interpretation of the data, since it affects all measurements in the same way.

The effect of tip bias Vtip has been studied by performing lift-mode scans with a lift-off height of 60 nm with respect to the reference topography, see Supplementary Section 2. From these measurements, we extract a tip gating efficiency \({\alpha }_{tip}=dG/d{V}_{tip}=0.047\pm 0.008\,\frac{{{{\rm{e}}}}^{2}}{{{\rm{hV}}}}\) at Vbg = 3 V, defined as the change in device conductance with respect to the variation in tip-sample voltage difference. Furthermore, we have extracted the back gate efficiency αbg = dG/dVbg with the tip placed far away from the semiconducting region, i.e., the slope of the linear region of the opening curve of the device, as \({\alpha }_{bg}=0.62\pm 0.05\,\frac{{{{\rm{e}}}}^{2}}{{{\rm{hV}}}}\), see the red dashed line in Fig. 1b. This results in a ratio of gating efficiencies between the tip and the back gate of αtip/αbg = 0.08 ± 0.02. This indicates that, when placed at 60 nm distance from the sample, the effect of 10 V on the tip is equivalent to a variation of the back gate potential of about 0.8 V.

One of the main difficulties found in performing SGM measurements on these samples was related to the strong susceptibility of the system to electric perturbations. Therefore, for the data show below, we decided to work in flying mode (see Methods) with 100 nm as the optimal safety distance between tip and sample.

Supercurrent flow manipulation

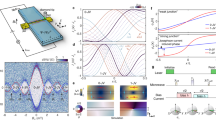

Mapping supercurrent profiles with SGM on SNS devices has been theoretically proposed recently57. Here, we report the experimental demonstration of SGM on superconducting weak links. The device is displayed in Fig. 2a. At 300 mK, we report an open channel switching current of about 80 nA (see Fig. 2c), a value consistent with the ones reported from previous experiments on similar structures50,53. As the back gate voltage is reduced, we identified three regimes in the junction behavior (see Fig. 2d): (i) For Vbg > 14 V, no back gate induced critical current modulation is present, similar to what was reported in ref. 50. (ii) For 14 V > Vbg > 2.5 V, the critical current experiences an overall downward trend. We have identified this as the optimal region to place the back gate set-point in order to maximize the influence of the tip on the behavior of the junction. (iii) For Vbg < 2.5 V, the Josephson effect is completely suppressed in the weak link. Thus, the device works as a Josephson field-effect transistor (JoFET).

a Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) image of device SGM1 D8D2. The scale bar corresponds to 1 μm b Critical current as a function of back gate voltage. The green line indicates the position of the working point Vbg = 9.5 V. The red line shows to the best linear fit of the critical current modulation by the back gate in the neighborhood of the working point. c Current-voltage curve of the device at Vbg = 20 V. d Differential resistance map as a function of back gate voltage and current bias.

We identified the optimal working point as Vbg = 9.5 V and performed a least squares fit with a linear model of the critical current modulation by the back gate voltage close to the working point, as shown in Fig. 2b. We obtain a critical current modulation efficiency \({\beta }_{bg}=\delta {I}_{c}/\delta {V}_{bg}=6.5\,\frac{{{\rm{nA}}}}{{{\rm{V}}}}\).

The SGM tip has then been placed in the middle of the junction at a safety distance of 100 nm above the highest point recorded in a previously acquired AFM topography map (for the reasons discussed above). Then, keeping the tip position fixed, we have acquired I − V curves in a four-probe DC current bias configuration for different values of the tip potential. The resulting variation in critical current as a function of the tip-to-sample voltage difference is reported in Fig. 3a as blue dots, showing a clear reduction in critical current when Vtip < 0 and an enhancement when Vtip > 0 (see also Supplementary Section 3).

a Critical current (with error bars) as a function of tip-to-sample voltage difference Vtip when the tip is placed close to the geometrical center of the junction; the best linear fit to the displayed data is shown in orange, while the result of numerical simulations is reported in green. b SGM map measurement: 20 pixel × 20 pixel critical current map as a function of the position of the tip. Vtip = −10 V, Vbg = 9.5 V. c Numerical simulation of the tip-induced critical current modulation map (details on the theoretical model can be found in the Methods). In (b) and (c), the device outline is indicated by the dashed yellow lines. Device SGM1 D8D2.

The observed modulation in critical current is of a few nA, which is in agreement with numerical simulations, see the green line in Fig. 3(a). For details on the simulations, see below and Methods. By performing a least squares fit with a linear model, we obtain a critical current modulation efficiency \({\beta }_{tip}=\delta {I}_{c}/\delta {V}_{tip}=0.35\,\frac{{{\rm{nA}}}}{{{\rm{V}}}}\) (orange line in Fig. 3(a)). This indicates that, in these conditions, the effect of applying 10 V on the tip is equivalent to a variation in the back gate voltage of about 0.5 V, which is roughly consistent with the value obtained at 77 K. Such trends have been reproduced over multiple acquisitions, confirming that the tip exerts an influence on the superconductive behavior of the sample, opening up the possibility of performing SGM critical current maps.

Next, the tip has been scanned in an evenly spaced grid of 20 x 20 positions while maintaining a constant vertical distance of 100 nm; we have kept a fixed voltage difference Vtip = − 10 V with respect to the sample, in order to induce depletion of charge carriers. For each grid-point we have acquired an I − V curve of the device in a four-wire DC current bias setup, using a NiDAQ acquisition board for both signal generation and acquisition at its maximum sampling frequency of f = 5 kHz. From these data, the critical current for each grid-point was determined. The results are reported in Fig. 3b. The map shows a clear reduction of the supercurrent of the device, indicated by the blue area in the middle of the plot, once the tip is placed close to the location of the junction. As the tip-to-junction lateral distance increases, an increase in the critical current is observed, indicating the local nature of the tip-device interaction. We observe a ΔIc = 2 nA critical current signal difference between the center and the margins of the scan area: this is consistent with the measurements reported in Fig. 3a; we can explain the difference between ΔIc and its expected value ΔIc0 = 10 V ⋅ βtip = 3.5 nA with the presence of a residual electrostatic interaction between the device and the tip when it is placed at the margins of the scan range.

In Fig. 3c we report the results of a numerical simulation of the tip-induced critical current modulation, which reliably reflects all features observed in the experimental data. In the simulations we assume that the effect of the tip is to induce a local electrostatic energy shift in the normal region that we model as a Lorentzian-like potential of strength V0. It has been shown, starting from a microscopic theory with density functional theory, that the Lorentzian profile of the effective potential is a good description58. The half-width of the Lorentzian curve is described by dx,tip and dy,tip. We expect dx,tip and dy,tip to depend on the tip curvature and on the tip-sample distance. To reproduce the experimental data, we set dx,tip = 750 nm, dy,tip = 1200 nm, and V0 = 1 meV corresponding to ΔVtip = −10 V. Further details on the theoretical model and simulation parameters can be found in the Methods. We underline that consistent results were obtained on a second device, see Supplementary Section 4.

Discussion

We have reported SGM experiments performed on both InSb nanoflag-based devices and superconducting weak links. In particular, we have reported SGM critical current modulation maps, demonstrating the possibility of locally manipulating the behavior of superconductive weak links through a charged SGM tip. This last achievement is a proof of principle that will set a path for future experiments to characterize and manipulate the superconducting behavior of hybrid systems at a local level.

In order to progress in the development of the SGM technique, it is necessary to improve its spatial resolution. Furthermore, the tip-to-sample capacitive coupling decreases with increasing sample-to-tip distance, limiting the experiment signal-to-noise ratio. Therefore, it is of pivotal importance for the future development of the technique to find ways of reducing this distance.

This can be achieved by depositing on the region of interest a few-nm thick layer of high performance dielectric (e.g., HfO2 or h-BN). Indeed, we have chosen a safe working point with a fixed tip distance of 100 nm from the highest point of the device, which are the Nb electrodes. They are 150 nm thick and placed on top of the InSb nanoflag. Therefore, the tip is at a distance of 250 nm from the surface of the semiconductor, which limited the resolution of the SGM measurements, since the strength of the tip potential decreases quadratically with the distance. On the other hand, it is challenging to work in the narrow gap between the two Nb electrodes, because the slightest contact between the sample and the biased tip leads to a catastrophic discharge. This problem can be solved by a thin (few nm-thick) dielectric layer that covers and protects the exposed surfaces. This will allow to perform SGM with the polarized tip placed directly in contact with the dielectric layer while at the same time preventing the danger of electrical discharges and increasing the tip-to-sample capacitance. In addition, the large dielectric constant of HfO2 would allow to reduce the bias applied to the tip, further contributing to a safe measurement.

Another important factor regarding the tip resolution is the physical dimension of the tip itself that is reflected in the dx,tip and dy,tip values of the tip potential. To emphasize this point, we present additional results from numerical simulations of SGM scans, performed for smaller values of dx,tip and dy,tip, considering a spherical shape instead of an elongated one, and values of V0 equal to or exceeding those discussed above. This would describe the potential induced by a tip brought closer to the sample.

In Fig. 4a, we show a heatmap similar to that in Fig. 3c, but for dx,tip = dy,tip = 200 nm. As in Fig. 3c, we set V0 = 1 meV and all other parameters as given in Table 1 and Table 2 (see Methods). By comparing with Fig. 3c, one can clearly see that the effect induced by this narrower effective potential is qualitatively the same as that induced by a wider one. However, although the overall supercurrent modulation slightly decreases, the resolution is significantly improved: Indeed, the region presenting current modulation is much more localized around the weak link area.

Heatmaps of the critical current versus SGM tip position resulting from the numerical simulations, for an effective Lorentzian potential of semi-axes dx,tip = dy,tip = 200 nm for (a) and 50 nm for (b–d), for different tip strengths V0, and in the presence or absence of disorder in the normal region (parametrized by Vdis). a V0 = 1 meV, Vdis = 30 meV; b V0 = 1 meV, Vdis = 30 meV; c V0 = 10 meV, Vdis = 30 meV; d V0 = 1 meV, Vdis = 0. In the simulations we set all other parameters as in Table 2. The yellow dashed lines delimit the normal region and the superconducting leads.

In Fig. 4b, c we show analogous plots, but for dx,tip = dy,tip = 50 nm and for two values of V0, respectively 1 and 10 meV. Thanks to the further enhanced spatial resolution, local modulation patterns within the weak link even at low tip potentials can be discerned. These features appear to be closely tied to the underlying disorder configuration. Indeed, in our simulations, the on-site potential fluctuations are randomly distributed within the interval [ − 15 meV, 15 meV], making them comparable in magnitude to the energy shift induced by the tip (see also Supplementary Section 5). To strengthen our claim, in Fig. 4d we show the results of the SGM scan simulation in the absence of disorder, with V0 = 1 meV and all the other parameters unchanged. In this case, no local features can be resolved.

We can draw two main conclusions from these additional simulations. First, independent of the presence or absence of disorder, for values of V0 of the same order of magnitude of the barrier strength, the tip induces a strong modulation of the current when scanning the NS interfaces (see the region around the vertical dashed yellow lines in Fig. 4c). This apparently counter-intuitive effect has a simple explanation: When the tip is located at the NS interface and its induced potential is comparable to the barrier strength, it strongly affects the junction transparency.

Second, as the effective area of the tip potential (i.e., the tip resolution) becomes smaller than the area of the normal region, we can resolve disorder-related features even for weak tip potentials, and thus extract information relative to the disorder distribution (cf. Supplementary Section 5). We notice en passant that features similar to those reported in Fig. 4c, obtained for a strong tip potential, have been reported in previous SGM experiments on normal-semiconductor devices59,60,61.

Once these developments come into play, it will be possible to acquire well-resolved critical current modulation maps, opening up a way to perform supercurrent flow imaging, to better understand the physics of superconducting weak links. In perspective, the SGM technique demonstrated here can be applied to such structures also in the presence of an external magnetic field (both in-plane or out-of-plane)57.

Finally, it is worth mentioning that our study opens up a promising way of investigating and manipulating topological phases at a local level via SGM. Indeed, topological transitions were observed by measuring Josephson junctions made of proximitized ballistic InSb quantum wells62. It has been shown that 0 − π transitions can be monitored by changing the in-plane magnetic field or the gate voltage. In perspective, this control could be exerted by the biased tip of the SGM at a local level with spatial resolution, a key step in the path to engineering devices suitable to perform fault-tolerant quantum computation. In fact, the presence of the polarized tip can be used to locally deplete a topological device, inducing a local topological phase transition, and leading to the formation of Majorana zero modes.

Methods

SGM measurement modes

Lift-mode

Lift-mode is an operation mode that is already built in the microscope controller software and consists in performing a double raster scan, see Fig. 5 (top):

-

At first, one line of topography signal is acquired (forward and backward): the tip is in contact with the sample and kept grounded while doing this, in order to prevent discharges (here we are implying that the tip is kept at a distance from the sample determined by the AFM feedback loop, not that it is actually scratching the sample).

-

Then the tip stops, and the tip is lifted up from the sample by a given amount; after the tip is lifted, there is the possibility of activating some “Alternatives”, such as generating a signal from one of the DAC channels of the microscope controller: here, a selected voltage value was used to polarize the tip.

-

After a user-selected delay, the tip performs a second line scan maintaining a constant distance from the device equal to the lift value, using as a reference the previously recorded topography signal.

-

Alternatives get deactivated, the tip is put again in contact with the sample, and after a user-selected delay interval, the following topography line of the raster scan is acquired.

Flying mode

Lift-mode does not allow the possibility of performing pixel-by-pixel actions (such as acquiring an I − V curve for each tip position); this is just an issue of the software that we use to control the microscope. For this reason, all critical current modulation measurements have been performed in flying mode. Flying mode, depicted in Fig. 5 (bottom), is an operation mode that requires a previously acquired reference topography map of the scan area; in this protocol, the tip is never in contact with the sample and, for this reason, no simultaneous topography is acquired. The reference topography is used to determine the highest point of the sample. Then the tip extension is limited to a maximum value equal to said reference minus a safety distance. After having polarized the tip, it can be scanned over the region of interest while simultaneously acquiring the desired electrical signals.

Theoretical simulations

Theoretical model

We now describe the theoretical model used to perform the simulations of the SNS device and the SGM experiment. We consider a planar Josephson junction in the x − y plane and extending along the x-direction. We denote the junction width by W, and the length of the normal region by L. Furthermore, we set the axis origin in correspondence of the the bottom-left corner of the normal region. The left and right leads are obtained by proximitizing the InSb nanoflag with a conventional s-wave superconductor. The junction is schematically represented in Fig. 6.

We adopt a tight-binding model on a finite square lattice to model the SNS junction. The Hamiltonian is given by

where \(i,{i}^{{\prime} }\) (\(j,{j}^{{\prime} }\)) refer to the discretized x (y) coordinates of the square lattice sites and \({c}_{i,j}^{t}=({c}_{\uparrow ,i,j},{c}_{\downarrow ,i,j},{c}_{\downarrow ,i,j}^{{\dagger} },-{c}_{\uparrow ,i,j}^{{\dagger} })\) with c↑/↓,i,j the fermionic annihilation operator with spin projection ↑/↓ on the site i, j, and

Here \({{\mathcal{T}}}=-i{\sigma }_{y}{{\mathcal{K}}}\) is the operator implementing time-reversal symmetry and \({{\mathcal{H}}}(i,j;{i}^{{\prime} },{j}^{{\prime} })\) models the non-proximitized region of the junction, i.e., the InSb nanoflag, perturbed by the electrostatic tip of the SGM. It reads

where σ0 is the 2 × 2 identity matrix, and σi, i = x, y, z are the Pauli matrices acting on the spin degree of freedom. Here μ is the chemical potential, \(t=\frac{{\hslash }^{2}}{2{m}^{* }{a}^{2}}\) parametrizes the first neighbor hopping, with a the spacing assumed in the lattice discretization, and m* is the electron effective mass. Moreover, \({{{\mathcal{E}}}}_{R}=\frac{{\alpha }_{R}}{2a}\) is the energy scale associated to the Rashba spin-orbit coupling. We have also included an on-site disorder potential with each of the vdis(i, j) randomly extracted from the interval [ − Vdis/2, Vdis/2] with a uniform distribution with Vdis the disorder strength. In Eq. (3) we have also introduced \({v}_{{{\rm{B}}}}(i,j)={{\mathcal{U}}}({\delta }_{i,0}+{\delta }_{i,l-1})\) to model the presence of potential barriers of strength \({{\mathcal{U}}}\) on the first and last column of sites in the normal region. Here, l = ⌊L/a⌋ + 1 represents the number of sites of the normal region, with a = 10 nm the discretization lattice parameter used in the simulations. Such barriers are added to tune the transparency at the NS interface, which according to the Blonder-Tinkham-Klapwijk (BTK) model63 is defined as

with \(Z={m}^{* }{{\mathcal{U}}}a/({\hslash }^{2}{k}_{F})\) a pure number parametrizing the barrier strength. If we assume a parabolic dispersion of the bands and \(\mu =\frac{{\hslash }^{2}{k}_{F}^{2}}{2{m}^{* }}\), then we have \(Z=\sqrt{\frac{{m}^{* }}{2\mu {\hslash }^{2}}}\, {{\mathcal{U}}}a\). The chemical potential is related to the back gate potential according to the following relation

In the simulations we assume that the effect of the tip is to induce a local electrostatic energy shift in the normal region that we model as a Lorentzian-like potential58 via

where xtip and ytip define the position of the tip. The parameters dx,tip and dy,tip describe therefore the half-width of the Lorentzian curve. For any \({r}^{2}\in {{\mathbb{R}}}^{* }\), the curve \({\left(\frac{x-{x}_{{{\rm{tip}}}}}{{d}_{x,{\mbox{tip}}}}\right)}^{2}+{\left(\frac{y-{y}_{{{\rm{tip}}}}}{{d}_{y,{\mbox{tip}}}}\right)}^{2}={r}^{2}\) defines an equipotential line. We expect dx,tip and dy,tip to depend on the tip curvature and on the tip-sample distance. In this sense, one may think of the ellipse of semi-axes dx,tip and dy,tip as the shadow-like projection of the tip onto the sample. To reproduce the experimental data, we set dx,tip = 750 nm, dy,tip = 1200 nm and assume that the effective parameter V0 describing the tip strength scales linearly with the potential difference of the tip, with V0 = 1 meV corresponding to ΔVtip = −10 V.

Finally, the superconducting correlations in Eq. (2) are described by

where Δ is the induced superconducting gap and θ(i) the usual step function.

The values adopted for the parameters to match InSb64 are reported in Table 1. Having defined the tight-binding Hamiltonian of both leads and the scattering region, the equilibrium Josephson supercurrent is computed through the recursive Green’s function approach65,66. Concerning the surface Green’s functions of the semi-infinite uncoupled leads, these are computed via the infinite recursive Green’s function method67. In order to fit the experimental data, we set the additional parameters listed in Table 2. It is worth underlining that small variations of the parameters with respect to those listed in Table 2 do not qualitatively alter the results of our simulations, as we discuss below.

For sake of completeness, in Fig. 7 we report a numerical simulation of the critical current versus back-gate voltage Vbg in absence of the SGM tip, showing a good agreement with the experimental data of Fig. 2b.

The result is plotted versus back-gate voltage in absence of the SGM tip, corresponding to the experimental data reported in Fig. 2b.

Parameters stability

The values of most model parameters are fixed by input from device characterization measurements. Specifically, the induced superconducting gap has been determined to be 250–350 μeV; the coefficient c, the lever arm converting a variation of the back-gate voltage to the corresponding variation of the chemical potential, is of the order of 10 meV V−1; and the voltage threshold is about 1V. Moreover, previous experiments conducted on devices obtained with the same fabrication process (see for instance50,53,54,68) have highlighted a good transparency of the junction, corresponding to a relatively low barrier. Finally, the high mobility found in these InSb nanoflags suggests a relatively small amount of disorder. Starting from these considerations, we run simulations in the absence of the tip and look for the parameters that yield the best fit of the curve Ic versus VBG presented in Fig. 2b. We explored the region of parameter space around the aforementioned values, and identified the parameters reported in Table 2 by minimizing the sum of squared residuals, in accordance with the least squares criterion. The resulting Ic versus VBG is reported in Fig. 7.

Qualitatively speaking, c and Vth are fixed to match the transition from the linear to the stationary regime of the experimental curve. By varying them, one simply dilates or translates the Ic versus VBG curve. Thus, the parameters whose variations are more interesting to investigate are the strength of disorder Vdis, the strength of the barrier \({{\mathcal{U}}}\), and the induced superconducting gap Δ. In Fig. 8, we show different Ic versus VBG curves, superimposed to the experimental data. Each of these curves has been obtained by averaging over different disorder configurations, to suppress the high frequency oscillations related to the specific disorder realization. Every panel reports the best fit curve (with the parameters given in Table 2) together with four curves obtained for different values (higher and lower) of Δ (Panel (a)), Vdis (Panel (b)), and \({{\mathcal{U}}}\) (Panel (c)). From these plots one can clearly see that variations of approximately 10−20% in any of the three parameters relative to the values reported in Table 2 yield numerical curves that, while still qualitatively consistent with the experimental trends, exhibit a noticeably reduced quantitative agreement. The deviations from the best-fit curve are especially pronounced when the barrier strength \({{\mathcal{U}}}\) is tuned. This sensitivity arises because \({{\mathcal{U}}}\) directly modulates the junction transparency via the BTK formula63, which relates the transparency τ to the barrier strength as \(\tau =\frac{1}{1+{Z}^{2}}\), where Z is a dimensionless parameter proportional to \({{\mathcal{U}}}\). Consequently, even small changes in \({{\mathcal{U}}}\) can substantially impact the supercurrent flow through the junction.

Comparison of the experimental curve Ic versus VBG with numerical simulations for different parameter values around those reported in Table 2. a Δ is varied, all other parameters are as in Table 2; b Vdis is varied, all other parameters are as in Table 2; c \({{\mathcal{U}}}\) is varied, all other parameters are as in Table 2. The values adopted are indicated in the labels of each panel. The experimental curve is colored in black in all panels, while the best fit curve is always colored in green.

Data availability

Source data are provided upon request from the corresponding authors (Matteo Carrega (matteo.carrega@spin.cnr.it), Stefan Heun (stefan.heun@nano.cnr.it)).

Code availability

Computer code used for the simulations is provided upon request from the corresponding authors (Matteo Carrega (matteo.carrega@spin.cnr.it), Stefan Heun (stefan.heun@nano.cnr.it)).

References

Kitaev, A. Y. Unpaired Majorana fermions in quantum wires. Phys. Usp. 44, 131 (2001).

Stern, A. & Lindner, N. H. Topological quantum computation: from basic concepts to first experiments. Science 339, 1179–1184 (2013).

Mourik, V. et al. Signatures of Majorana fermions in hybrid superconductor-semiconductor nanowire devices. Science 336, 1003–1007 (2012).

Prada, E. et al. From Andreev to Majorana bound states in hybrid superconductor-semiconductor nanowires. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2, 575–594 (2020).

Ren, H. et al. Topological superconductivity in a phase-controlled Josephson junction. Nature 569, 93–98 (2019).

Fornieri, A. et al. Evidence of topological superconductivity in planar Josephson junctions. Nature 569, 89–92 (2019).

Lesser, O., Saydjari, A., Wesson, M., Yacoby, A. & Oreg, Y. Phase-induced topological superconductivity in a planar heterostructure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 118, e2107377118 (2021).

Pientka, F. et al. Topological superconductivity in a planar Josephson junction. Phys. Rev. X 7, 021032 (2017).

Eriksson, M. A. et al. Cryogenic scanning probe characterization of semiconductor nanostructures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 69, 671–673 (1996).

Topinka, M. A. et al. Coherent branched flow in a two-dimensional electron gas. Nature 410, 183–186 (2001).

Topinka, M. A. et al. Imaging coherent electron flow from a quantum point contact. Science 289, 2323–2326 (2000).

Jura, M. P. et al. Unexpected features of branched flow through high-mobility two-dimensional electron gases. Nat. Phys. 3, 841–845 (2007).

Jura, M. P. et al. Electron interferometer formed with a scanning probe tip and quantum point contact. Phys. Rev. B 80, 041303 (2009).

LeRoy, B. J., Topinka, M. A., Westervelt, R. M., Maranowski, K. D. & Gossard, A. C. Imaging electron density in a two-dimensional electron gas. Appl. Phys. Lett. 80, 4431–4433 (2002).

Percebois, G. J. et al. Reconstructing the potential configuration in a high-mobility semiconductor heterostructure with scanning gate microscopy. SciPost Phys. 15, 242 (2023).

Gold, C. et al. Local signatures of electron-electron scattering in an electronic cavity. Phys. Rev. Res. 3, 013287 (2021).

Gold, C. et al. Scanning gate microscopy of localized states in a gate-defined bilayer graphene channel. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 043380 (2020).

Aidala, K. E. et al. Imaging magnetic focusing of coherent electron waves. Nat. Phys. 3, 464–468 (2007).

Paradiso, N. et al. Imaging Fractional Incompressible Stripes in Integer Quantum Hall Systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 246801 (2012).

Paradiso, N. et al. Selective control of edge-channel trajectories by scanning gate microscopy. Phys. E 42, 1038–1041 (2010).

Paradiso, N. et al. Imaging backscattering through impurity-induced antidots in quantum Hall constrictions. Phys. Rev. B 86, 085326 (2012).

Tomimatsu, T., Hashimoto, K., Taninaka, S., Nomura, S. & Hirayama, Y. Probing the breakdown of topological protection: Filling-factor-dependent evolution of robust quantum Hall incompressible phases. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 013128 (2020).

Braem, B. A. et al. Investigating energy scales of fractional quantum Hall states using scanning gate microscopy. Phys. Rev. B 93, 115442 (2016).

Bours, L. et al. Manipulating quantum Hall edge channels in graphene through scanning gate microscopy. Phys. Rev. B 96, 195423 (2017).

Aharon-Steinberg, A. et al. Long-range nontopological edge currents in charge-neutral graphene. Nature 593, 528–534 (2021).

Marguerite, A. et al. Imaging work and dissipation in the quantum Hall state in graphene. Nature 575, 628–633 (2019).

Dou, Z. et al. Imaging bulk and edge transport near the dirac point in graphene Moiré superlattices. Nano Lett. 18, 2530–2537 (2018).

Sakanashi, K. et al. Investigation of laser-induced-metal phase of MoTe2 and its contact property via scanning gate microscopy. Nanotechnology 31, 205205 (2020).

Bachtold, A. et al. Scanned probe microscopy of electronic transport in carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 6082–6085 (2000).

Freitag, M., Johnson, A. T., Kalinin, S. V. & Bonnell, D. A. Role of single defects in electronic transport through carbon nanotube field-effect transistors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 216801 (2002).

Bozovic, D. et al. Plastic deformations in mechanically strained single-walled carbon nanotubes. Phys. Rev. B 67, 033407 (2003).

Denisov, A. O. et al. Microwave-frequency scanning gate microscopy of a Si/SiGedouble quantum dot. Nano Lett. 22, 4807–4813 (2022).

Gildemeister, A. E. et al. Imaging a coupled quantum dot-quantum point contact system. J. Appl. Phys. 102, 083703 (2007).

Huefner, M. et al. Spatial mapping and manipulation of two tunnel-coupled quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 83, 235326 (2011).

Huefner, M. et al. Scanning gate microscopy measurements on a superconducting single-electron transistor. Phys. Rev. B 79, 134530 (2009).

Martins, F. et al. Imaging electron wave functions inside open quantum rings. Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 136807 (2007).

Fan, Y. et al. Electric-field control of spin–orbit torque in a magnetically doped topological insulator. Nat. Nanotechnol. 11, 352–359 (2016).

Bhandari, S. et al. Imaging Andreev reflection in graphene. Nano Lett. 20, 4890–4894 (2020).

Hegedüs, M. et al. In situ scanning gate imaging of individual quantum two-level system defects in live superconducting circuits. Sci. Adv. 11, eadt8586 (2025).

Maji, S., Sowa, K. & Nowak, M. P. Scanning gate microscopy of nonretracing electron-hole trajectories in a normal-superconductor junction. Phys. Rev. B 109, 115410 (2024).

Maji, S. & Nowak, M. P. Scanning gate microscopy detection of majorana bound states (2025). arXiv: 2501.14562.

Iagallo, A. et al. Scanning gate imaging of quantum point contacts and the origin of the 0.7 anomaly. Nano Res. 8, 948–956 (2014).

Brun, B. et al. Wigner and Kondo physics in quantum point contacts revealed by scanning gate microscopy. Nat. Commun. 5, 4290 (2014).

Bleszynski, A. C. et al. Scanned probe imaging of quantum dots inside InAs nanowires. Nano Lett. 7, 2559–2562 (2007).

Chen, S. et al. Current induced hidden states in Josephson junctions. Nat. Commun. 15, 8059 (2024).

Verma, I. et al. High-mobility free-standing InSb nanoflags grown on InP nanowire stems for quantum devices. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 4, 5825–5833 (2021).

Prosko, C. G. et al. Flux-tunable Josephson effect in a four-terminal junction. Phys. Rev. B 110, 064518 (2024).

Yan, S. et al. Supercurrent, multiple Andreev reflections and shapiro steps in inas nanosheet Josephson junctions. Nano Lett. 23, 6497–6503 (2023).

de Vries, F. K. et al. Crossed Andreev reflection in InSb flake Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. Res. 1, 032031 (2019).

Salimian, S. et al. Gate-controlled supercurrent in ballistic InSb nanoflag Josephson junctions. Appl. Phys. Lett. 119, 214004 (2021).

Kang, N. et al. Two-dimensional quantum transport in free-standing InSb nanosheets. Nano Lett. 19, 561–569 (2019).

Chen, Y. et al. A double quantum dot defined by top gates in a single crystalline InSb nanosheet. Chin. Phys. B 30, 128501 (2021).

Turini, B. et al. Josephson diode effect in high-mobility InSb nanoflags. Nano Lett. 22, 8502–8508 (2022).

Iorio, A. et al. Half-integer Shapiro steps in highly transmissive InSb nanoflag Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 033015 (2023).

Guiducci, S. Electron transport and Scanning Gate Microscopy studies on ballistic hybrid SNS junctions. Master’s thesis (University of Pisa, 2014).

Guiducci, S. et al. Full electrostatic control of quantum interference in an extended trenched Josephson junction. Phys. Rev. B 99, 235419 (2019).

Kaperek, K., Heun, S., Carrega, M., Wojcik, P. & Nowak, M. P. Theory of scanning gate microscopy imaging of the supercurrent distribution in a planar Josephson junction. Phys. Rev. B 106, 035432 (2022).

Szafran, B. Scanning gate microscopy simulations for quantum rings: effective potential of the tip and conductance maps. Phys. Rev. B 84, 075336 (2011).

Burke, A. M. et al. Periodic scarred states in open quantum dots as evidence of quantum Darwinism. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 176801 (2010).

Aoki, N. et al. Direct imaging of electron states in open quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 136804 (2012).

Cabosart, D. et al. Recurrent quantum scars in a mesoscopic graphene ring. Nano Lett. 17, 1344–1349 (2017).

Ke, C. T. et al. Ballistic superconductivity and tunable π-junctions in InSb quantum wells. Nat. Commun. 10, 3764 (2019).

Blonder, G. E., Tinkham, M. & Klapwijk, T. M. Transition from metallic to tunneling regimes in superconducting microconstrictions: Excess current, charge imbalance, and supercurrent conversion. Phys. Rev. B 25, 4515–4532 (1982).

Vurgaftman, I., Meyer, J. R. & Ram-Mohan, L. R. Band parameters for III-V compound semiconductors and their alloys. J. Appl. Phys. 89, 5815–5875 (2001).

Furusaki, A. DC Josephson effect in dirty SNS junctions: numerical study. Phys. B 203, 214–218 (1994).

Asano, Y. Numerical method for dc Josephson current between d-wave superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 63, 052512 (2001).

Sancho, M. P. L., Sancho, J. M. L., Sancho, J. M. L. & Rubio, J. Highly convergent schemes for the calculation of bulk and surface Green functions. J. Phys. F: Met. Phys. 15, 851 (1985).

Chieppa, A. et al. Unveiling the Current-Phase Relationship of InSb Nanoflag Josephson Junctions Using a NanoSQUID Magnetometer. Nano Lett. 25, 14412–14419 (2025).

Acknowledgements

Useful discussions with Michal P. Nowak and Fernando Domingues are gratefully acknowledged. The authors acknowledge the support from the project PRIN2022 2022-PH852L(PE3) TopoFlags—"Non reciprocal supercurrent and topological transition in hybrid Nb-InSb nanoflags” funded by the European community—Next Generation EU within the program “PNRR Missione 4—Componente 2—Investimento 1.1 Fondo per il Programma Nazionale di Ricerca e Progetti di Rilevante Interesse Nazionale (PRIN)” and by PNRR MUR Project No. PE0000023-NQSTI.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.L. performed the measurements, data analysis, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. G.S., G.B., and S.S. fabricated the Josephson junction devices. G.B., V.Z., and L.S. grew the InSb nanoflags. S.T., S.F., N.T.Z., M.S., and M.C. performed the theoretical analysis. S.H. conceived the idea and supervised the work. A.L., G.S., G.B., S.S., V.Z., S.T., S.F., N.T.Z., M.S., M.C., F.B., L.S., and S.H. contributed to the interpretation of the results and to the revision of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Materials thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lombardi, A., Shukla, G., Bucci, G. et al. Supercurrent modulation in InSb nanoflag-based Josephson junctions by scanning gate microscopy. Commun Mater 6, 272 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-01000-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43246-025-01000-0