Abstract

Intense rainfall from tropical cyclones has the potential to induce coastal acidification, which will become more common and severe as climate change continues. We collected carbonate chemistry samples from Galveston Bay, Texas before and after Hurricane Harvey in 2017 and 2018. Here, we show ecosystem level acidification and calcium carbonate undersaturation in Galveston Bay following the storm. This acidification event, driven by extreme rainfall from Harvey, persisted for over 3 weeks because of prolonged flood mitigation reservoir releases that continued for over a month after the storm. In addition, the large volume of stormwater led to high oyster mortality rates in Galveston Bay and acidification may have impeded recovery of these vital reefs. It is also likely that undersaturation has occurred outside of our study, unrecorded, following other high-rainfall storms. The projected increase in tropical cyclone rainfall under climate change may thus represent a significant threat to coastal calcifying ecosystems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coastal ecosystems are among the most diverse and productive environments in the world, contributing to approximately one third of the estimated value of global ecosystem goods and services1,2. However, the coastal ocean is threatened by several local (e.g., overfishing, pollution, eutrophication) and global (e.g., warming, acidification) anthropogenic stressors. Marine organisms that form calcium carbonate (CaCO3) shells and skeletons, such as oysters and corals, are particularly important in many coastal environments. They create complex three-dimensional reef structures that provide habitat for thousands of marine species; coastline protection from storms and erosion; and income through fishing and tourism3. Calcifying organisms are especially vulnerable to ocean acidification because it slows calcification and enhances CaCO3 dissolution, thereby threatening the essential services that depend on the reef framework4.

Ocean acidification is caused by the oceanic absorption of anthropogenic atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2), leading to a decline in seawater pH and CaCO3 saturation state (Ω). The Ω indicates the thermodynamic favorability of formation (Ω > 1) or dissolution (Ω < 1) of CaCO3 in seawater4. Atmospheric CO2 levels have increased from ~280 to more than 400 ppm since the Industrial Revolution, and the threat of ocean acidification to calcifying ecosystems continues to worsen4,5. In the coastal ocean, acidification can be further influenced by local processes including changes in river discharge, flooding, storms, nutrient loading, etc., which are collectively referred to as coastal acidification4,6. Ocean and coastal acidification also have complex interactions with other global climate processes that are of particular concern for coastal regions. While it is well documented that tropical cyclones can cause physical damage and destruction in calcifying ecosystems7,8,9,10, the effect of these storm events on coastal ocean chemistry is not well understood.

Rainfall and runoff associated with tropical cyclones have been shown to contribute to coastal acidification that can be damaging to calcifying ecosystems11,12. It has been predicted that by the end of this century, tropical cyclones could cause short-term (days to weeks) coastal acidification, leading to waters that are corrosive to aragonite (i.e., aragonite Ω (Ωar) < 1)11, a mineral form of CaCO3 produced by many calcifying organisms including corals and larval oysters. The intensity and rainfall associated with tropical cyclones are projected to increase under business-as-usual CO2 emission scenarios13,14, making the need to understand and accurately predict the impact of these events on coastal acidification ever more urgent for both environmental and resource management reasons.

Of the top ten wettest tropical cyclones on record in the United States, five have made landfall on the Texas coast. On August 26, 2017, Hurricane Harvey (hereafter called Harvey) made landfall near Port Aransas, Texas as a Category 4 hurricane (wind speeds of 209–251 km h−1), becoming the wettest tropical cyclone in US history to date15. Harvey released more than 92 million m3 of water across Texas and Louisiana, an unprecedented amount of rainfall for the region16,17. The Houston metropolitan area was hit particularly hard as the storm stalled over the southeastern coast of Texas from August 26 to 30 (Fig. 1a) and caused catastrophic flooding, with some areas receiving more than 100 cm of rainfall15. To mitigate inland flooding, the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) manually released stormwaters from the Addicks and Barker reservoirs in the Houston area, which flowed through Buffalo Bayou and merged with the San Jacinto River before entering Galveston Bay through the Houston Shipping Channel (Fig. 1). This controlled release of stormwater began on August 28, 2017, increased in volume through September 3, and the reservoirs were finally closed over a month later, on October 12 (Addicks) and 13 (Barker), 2017. The reservoir releases resulted in a maximum combined discharge into Galveston Bay of 370 m3 s−1,18 comparable to the annual mean river discharge into the bay of approximately 350 m3 s−1,16. This large volume of freshwater introduced to Galveston Bay over an extended period had the potential to cause prolonged changes in bay water chemistry.

a This map shows the path of Hurricane Harvey through Texas and Louisiana, with points marking 12-h intervals beginning August 25 (data from National Hurricane Center archive, https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/). The shape and colors represent the storm severity at each timepoint (Tropical Depression (TD), blue triangle; Tropical Storm (TS), teal diamond; and Hurricane, circles (Cat 1, green; Cat 2, yellow; Cat 3, orange; Cat 4, red)). The 200 m isobath identifying the shelf break is outlined in gray on the map. The black box indicates zoomed area in b showing stations 15–24 on the Texas coast in the Gulf of Mexico in red, as well as the location of Texas Automated Buoy System, buoy B (TABS-B) in black. c Is a map of Galveston Bay showing sampling sites 1–14 in red and the relative location of the Addicks and Barker reservoirs colored in blue. The Trinity River, San Jacinto River, and Buffalo Bayou are marked in (c) with black lines and the city of Houston is marked by a star.

Galveston Bay (Fig. 1) is home to valuable oyster reefs that have historically accounted for 18% of the total average annual US Eastern Oyster harvest between 1991 and 200719. However, that percentage has since decreased to 8.7% for 2007–201620. Oyster larvae and permanently settled larval oysters, referred to as spat, biomineralize aragonite, the more soluble form of CaCO3, compared to calcite, the form produced by adult oysters. Studies have shown that decreases in Ωar have significant negative impacts on larval oyster growth and calcification, which can have serious implications for the continuation and recovery of damaged reefs2,21,22. Similarly, decreases in calcite Ω (Ωca) have been correlated with declines in adult oyster calcification23. Since long-term acidification has already been documented in several Texas estuaries, including Galveston Bay24, understanding the role of tropical cyclones on coastal acidification is needed to aid in predicting the long-term survival of these oyster reefs.

Here we present the changes and recovery timescale of the seawater carbonate chemistry system in Galveston Bay following Harvey using data collected from June 2017 through September 2018, including two post-storm sampling periods after Harvey in September 2017. We show persistent storm-induced coastal acidification and bay-wide CaCO3 undersaturation following Harvey, describe the likely mechanisms driving this storm-induced acidification, and discuss the role it may play in the multi-stressor environments of calcifying ecosystems. The excessive rainfall and runoff associated with Harvey (referred to hereafter as stormwaters) provides a valuable opportunity to characterize the effects of high-precipitation storms on the acidification of coastal marine ecosystems, which will become more common as climate change progresses.

Results

Tropical cyclone-induced acidification

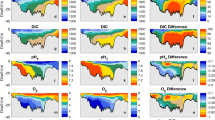

To characterize the impact of Harvey on the carbonate chemistry and coastal acidification of Galveston Bay, we analyzed salinity, temperature, pCO2, pH, Ωca, and Ωar data pre- (June 2017) and post-storm (September 2017 to September 2018). The average bay salinity in Galveston Bay ranged from 13 to 24 (Table 1) for months outside of September 2017 (2–3 weeks following Harvey), consistent with previous studies25, with generally well-mixed conditions (Supplementary Fig. S1). In September 2017, the average salinity in the bay was 3.4 ± 3.8 (Table 1 and Fig. 2), indicating primarily freshwater conditions following Harvey that persisted for >3 weeks. Average temperatures in Galveston Bay were not statistically different before (June 2017 = 27.6 ± 0.7 °C) and after (September 2017 = 26.9 ± 1.0 °C) Harvey and generally follow expected seasonal trends, with March and November showing lower average temperatures than June and September, for both 2017 and 2018 (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

Average values and standard error for discreet sampling time points of a pH, b aragonite saturation state (Ωar), c calcite saturation state (Ωca), d in situ partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2; red) and temperature-normalized pCO2 (npCO2; blue) to 26.0 °C (average in situ temperature across sampling period), e salinity, and f temperature. Solid lines show carbonate parameters calculated using constants from Millero41 recommended for estuaries; dotted lines with open circles show carbonate parameters calculated using Lueker et al.42 constants recommended for seawater (S > 15). The gray horizontal shading in (b) and (c) indicates undersaturated conditions (Ω < 1) and in (d) represents average atmospheric CO2 levels (~405 μatm) during the study. The yellow vertical bar shows the period of August 26–30 associated with heavy rainfall in the Houston area associated with Hurricane Harvey.

Samples collected in June 2017 prior to Harvey showed the average partial pressure of CO2 (pCO2) and pH in Galveston Bay were 470 ± 107 μatm and 8.0 ± 0.1, respectively. There was no undersaturation (Ω < 1) observed at any sampling site for either calcite or aragonite (Fig. 2 and Table 1), with a monthly average Ωca of 3.7 ± 1.0 and Ωar of 2.3 ± 0.6. Two weeks after Harvey made landfall (September 9, first post-storm sampling period), a significant acidification event was observed: average pCO2 increased to 985 ± 359 μatm; average pH decreased to 7.6 ± 0.2 (>200% increase in acidity of bay waters); all stations were undersaturated with respect to aragonite (Ωar < 1); and all stations except the bottom-water sample at station 1 (Ωca = 1.47) were undersaturated with respect to calcite (Ωca < 1). These shifts in Galveston Bay carbonate chemistry following Harvey were not driven by changes in temperature, since temperature did not change significantly before and after the storm (Table 1 and Fig. 2). Similarly, average temperature-normalized pCO2 (npCO2) increased from 431 ± 97 μatm before Harvey to 981 ± 372 μatm on September 9. All average values for carbonate chemistry parameters and salinity were significantly different (p < 0.05) on September 9 compared to pre-Harvey values in June and all other months sampled (Supplementary Table S1). Given that the stations sampled on September 9 were those closer to the mouth of the bay (stations 1, 3, 4, 6; Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table S2), which is usually the bay’s most saline region, it is likely that the acidification measured at these sites is representative of bay-wide conditions, since stormwaters primarily entered the northern part of the bay following Harvey (i.e., San Jacinto Estuary and Trinity River, Fig. 1c)16.

Enhanced acidification persisted in parts of the bay through September 16 (second post-storm sampling period), 3 weeks after Harvey made landfall: elevated pCO2 (>500 μatm) and depressed pH (pH ~7.9) were measured in bottom-water samples from stations 6, 8, and 14; aragonite undersaturation (Ωar = 0.04–0.93) was recorded at the surface and bottom at stations 8, 10, 13, 14; and calcite undersaturation (Ωca = 0.07–0.99) was measured at the surface and bottom at stations 13 and 14, and in the bottom-water samples of stations 8 and 10. However, compared to September 9, September 16 average pCO2 (435 ± 288 μatm) decreased; average pH (8.2 ± 0.2) increased; and average Ωar (0.6 ± 0.4) and Ωca (1.1 ± 0.7) increased. While average pH and pCO2 3 weeks post-storm were comparable to pre-Harvey levels, the standard deviation remained large, indicating considerable variability across the bay. Furthermore, average Ωar and Ωca remained significantly lower (p < 0.001) 3 weeks post-storm compared to pre-Harvey conditions (Supplementary Table S1 and Figs. 2 and 3).

For all plots, symbols are categorized according to sampling month (shape) and year (fill). Shapes: squares for March, circles for June, stars or asterisk for September, triangles for November; filled symbols for 2017 and open symbols for 2018. Diamonds indicate the average calculated endmember values connected by dark gray mixing lines. The standard deviation for each average endmember (error bars on endmembers in (a)) was used to determine the uncertainty associated with the mixing envelope shown by the gray shaded region. The mixing envelope uncertainty includes seasonal variability in the endmember values. The dotted line in (a) indicates a comparative 1:1 relationship for TA:DIC and endmembers are highlighted in yellow for clarity in (a). Color bars show values for b salinity (S), c aragonite saturation state (Ωar), d pH, and e partial pressure of carbon dioxide (pCO2).

By November 2017, 2 months post-Harvey, the average salinity (15.6 ± 5.2), pCO2 (382 ± 83 μatm), pH (8.10 ± 0.10), Ωar (2.0 ± 0.4), and Ωca (3.3 ± 0.6) had returned to pre-Harvey levels in June (Table 1 and Fig. 2). From November 2017 through September 2018, average monthly bay pCO2 and pH ranged from 382 to 475 μatm and 8.03 to 8.10, respectively (Fig. 2 and Table 1). In addition, almost no undersaturation for aragonite or calcite was observed at any of our sites for this post-Harvey period (with the exception of station 14 in March 2018 following elevated Trinity River discharge); average post-Harvey Ωar and Ωca ranged from 1.5 to 2.4 and 2.5 to 4.8, respectively (Fig. 2 and Table 1).

Tropical cyclone influence on freshwater carbonate chemistry

The two main sources of freshwater to Galveston Bay are river water and rainwater. In the bay, total alkalinity (TA) and dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) have linear relationships with salinity (Supplementary Fig. S2). Therefore, linear regression analysis can be used to provide estimates of the TA and DIC of all the combined freshwater (river water + rainwater) entering Galveston Bay. Using linear regression analysis, we evaluated the influence of Harvey on these freshwater signatures, comparing pre- and post-Harvey estimated endmembers. Before Harvey in June 2017, the combined freshwater TA (TAFW) was 1853 μmol kg−1. On September 9, 2017, 2 weeks post-storm, TAFW was 847 μmol kg−1, a decrease of 1006 μmol kg−1 compared to June 2017 (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. S2). This decline in TAFW likely occurred immediately post-Harvey, but conditions in the bay prevented carbonate chemistry sample collection prior to September 9, 2017. One week later, on September 16, TAFW had increased to 1260 μmol kg−1. TAFW remained low in November 2017 (1504 μmol kg−1) compared to June 2017 but had returned to pre-storm levels by March 2018 (1795 μmol kg−1). From March 2018 through September 2018, TAFW ranged from ~1700 to 1900 μmol kg−1, similar to pre-Harvey observations (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. S2). The combined freshwater DIC (DICFW) showed very similar trends as described for TAFW: a decline that likely occurred immediately post-storm and persisted 2 weeks after the storm (pre-Harvey DICFW: 1843 μmol kg−1; 2 weeks post-Harvey DICFW: 905 μmol kg−1); an increase in DICFW the following week (3 weeks post-Harvey DICFW: 1239 μmol kg−1); and a continued increase through March 2018 (1756 μmol kg−1), after which DICFW ranged from ~1670 to 1760 μmol kg−1 through September 2018 (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. S2). Like TAFW, DICFW appeared lower than pre-Harvey observations in early November 2017 (1417 μmol kg−1).

Drivers of storm-induced acidification

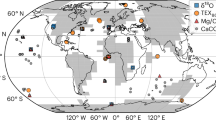

To investigate the influence of biological versus physical mixing processes on the Galveston Bay carbonate chemistry system, a TA versus DIC plot (Deffeyes diagram26) was examined with average TA and DIC endmember measurements for the three source waters to Galveston Bay: Gulf of Mexico (GOM) seawater, Galveston-watershed river water, and rainwater (Fig. 3; endmember values enumerated in Supplementary Table S3 and explained in the Methods). Each source water has a distinct signature in TA-DIC space and mixing lines were defined between all three endmembers. The standard deviation for each average endmember was used to quantify the uncertainty associated with mixing between the three source waters, referred to as the mixing “envelope” (Fig. 3 gray shading). Data that fall within the envelope are influenced by physical mixing between the three endmembers. In addition, other processes may cause minor modifications in the exact position of data points within the envelope. However, data that fall outside the envelope are significantly influenced by additional processes (i.e., biological activity). All data from this study lie within the uncertainty of the TA-DIC mixing envelope, demonstrating that physical mixing is dominating changes in the carbonate chemistry system. Even though biological processes are also occurring, any biological TA or DIC signal is simply overwhelmed by the physical mixing signature. Data from all months except September 2017 are heavily influenced by the seawater endmember and lie between and along the seawater-river water and seawater-rainwater mixing lines (Fig. 3). In contrast, data from both sampling dates in September 2017, 2–3 weeks following Harvey, lie closely along the mixing line between the river and rainwater endmembers, indicating the dominance of freshwater sources in the bay.

To further examine how Harvey affected mixing of source waters within Galveston Bay, a fractional composition analysis was performed to determine what percentage of bay water was GOM seawater, Galveston-watershed river water, and rainwater during our study (see Methods). In June 2017, the bottom water at station 1 was approximately 28% freshwater (river water + rainwater) and 72% GOM seawater, with the freshwater fraction increasing, and seawater fraction decreasing moving north from the mouth of the bay (79 ± 4% freshwater and 24 ± 3% GOM seawater at station 14, Supplementary Data 1 and Fig. 4). In contrast, in September 2017 following Harvey, post-storm freshwater fractions were ≥90% (≤10% GOM seawater) at all but two stations: station 1 on September 9 (~72% freshwater) and station 6 on September 16 (surface: ~81% and bottom: ~52% freshwater) (Supplementary Data 1 and Fig. 4). In addition, rainwater fractions for all reoccupied stations increased from June 2017 (1–21%) to September 2017 (23–48%), while river fractions remained similar (June 2017: 24–78%, September 2017: 29–77%) (Fig. 4). Therefore, the acidification event across Galveston Bay following Harvey was mainly associated with a dramatic increase in the rainwater fraction, which has low TA, DIC, pH, Ω, and buffering capacity (i.e., higher Revelle factor), as well as a negative [TA-DIC]27, compared to river water and GOM seawater (Supplementary Table S3, Fig. 3 and Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3).

Stacked bar charts indicate water column composition for 2017 sampling in a, b June, c, d September, and e November. The “b” indicates bottom sample (~1.2 m from bottom) and “s” indicates surface sample (~0.5 m) data. Teal is rainwater, brown with backslashes is Galveston-watershed river water, and dark blue with forward slashes is Gulf of Mexico seawater. Note that Galveston Bay water composition is summarized for 2018 sampling dates in Supplementary Fig. S3.

Rainwater fractions were greater on September 9 than September 16, despite the latter consisting of stations closer to freshwater sources (i.e., Trinity and San Jacinto Rivers, Figs. 1 and 4). Station 6, which was sampled on both dates in September, also showed a decrease in the rainwater fraction and increase in seawater fraction in surface and bottom waters between September 9 and 16 (Fig. 4). By November 2017, rainwater fractions (Nov 2017: 0–12%) were comparable to those in June 2017 (pre-Harvey: 1–21%) and March-September 2018 (1–16%) (Supplementary Data 1 and Supplementary Fig. S4).

Discussion

Galveston Bay experienced a severe, tropical cyclone-induced coastal acidification event following Hurricane Harvey that caused bay-wide CaCO3 undersaturation for 2 weeks, with undersaturation persisting in some areas of the bay for at least 3 weeks post-storm (Table 1 and Figs. 2 and 3). This coastal acidification event corresponded with an unprecedented increase in freshwater throughout the bay (Fig. 4)20,28. The increased freshwater fraction, however, was driven almost entirely by an increase in rainwater, with little change in river water fractions relative to pre-Harvey conditions. This rainwater increase is due to the short flushing time of Harvey stormwater within the Galveston Bay watershed16, likely resulting in minimal rock weathering and other reactions that impart a distinct carbonate chemistry signal to river water compared to rainwater. Changes in Galveston Bay carbonate chemistry were therefore dominated by the displacement of seawater within the estuarine system by Harvey stormwater (Fig. 4), which given the acidic nature of rainwater, led to dramatic coastal acidification of the bay.

In addition to the influx of stormwater, biological processes may have contributed to the acidification of Galveston Bay following Harvey. Enhanced respiration following storms can contribute to acidification in coastal environments12. In the Guadalupe-San Antonio estuary, southwest of Galveston Bay and close to where Harvey made landfall, elevated pCO2 levels were observed following a large influx of freshwater after Harvey and were attributed to enhanced respiration29. In Galveston Bay, an increased flux of terrigenous dissolved organic carbon was hypothesized to enhance microbial organic matter degradation and potentially produce a large flux of CO2 from the bay30,31. Elevated pCO2 levels measured 2 weeks post-landfall in this study are consistent with this hypothesis (Fig. 2). In addition, most of the data collected 2 weeks post-storm fall slightly below the predicted mixing line, which may be indicative of enhanced respiration (Fig. 3). However, these post-storm data fall within the uncertainty of the endmember mixing relationship, precluding attribution of elevated pCO2 specifically to enhanced respiration in the bay. In addition, the fractional analyses showed no major differences when calculated using TA or DIC (see methods for details of fractional analyses), providing further evidence that shifts in the carbonate chemistry following Harvey were dominated by the influx of rainwater, rather than increased respiration. Similarly, dissolution of aragonite and calcite may have occurred when bay waters were undersaturated, but a dissolution signal cannot be discerned in our TA and DIC data (Supplementary Data 1). Therefore, while enhanced respiration and CaCO3 dissolution may have played important ecological roles following Harvey, any signals in the carbonate chemistry system are overwhelmed by the physical mixing signature of a high volume of stormwater that entered Galveston Bay.

Signs of enhanced acidification in Galveston Bay persisted even 3 weeks post-storm, including widespread CaCO3 undersaturation (Figs. 2 and 3), large variability in the other carbonate parameters (e.g., pH, pCO2; Table 1 and Fig. 3), and increased rainwater fractions (Fig. 4) that are not observed except in September 2017. By November 2017, 10 weeks after Harvey made landfall, Galveston Bay appeared to have largely recovered to pre-Harvey carbonate chemistry conditions, consistent with the timescale reported in previous studies30,31. Despite indications of recovery in the recorded bay observations for November 2017 (i.e., salinity, carbonate chemistry, fractional analysis), the estimated combined freshwater endmembers (rainwater + river water; TAFW, DICFW) remained depressed (November 2017: TAFW = 1504 μmol kg−1, DICFW = 1417 μmol kg−1) compared to pre-Harvey (June 2017: TAFW = 1853 μmol kg−1, DICFW = 1843 μmol kg−1) and 2018 data (March, June, September 2018: TAFW = 1691–1885 μmol kg−1, DICFW = 1665–1756 μmol kg−1). Since this is the only November sampling in this time series, it is not clear whether the lower endmember value is driven by Harvey or seasonal changes in freshwater flux to the bay. Given the relatively long residence time (>45 days) in upper regions of the bay and the extended release of stormwater from local reservoirs16, it is possible that residual stormwaters were still present in the bay. Outside the influence of Harvey, variability in the river endmember carbonate chemistry may be due to seasonal effects, changes in streamflow, and/or shifts in the major contributing rivers to Galveston Bay16,24.

Coastal acidification was previously observed following Tropical Storm Kate12 and Tropical Storm Isaac11, and it was predicted that aragonite undersaturation could occur in coastal waters following tropical cyclones by 210011. Here, we show an extended (2+ weeks) period of bay-wide, ecosystem-level undersaturation with respect to aragonite and calcite in Galveston Bay following a tropical cyclone under current climate conditions. The volume of rainfall and the extended release of stormwater from the built environment (i.e., reservoirs) following Harvey caused an acidification response that was larger in magnitude and longer in duration than previously observed. Thus, prolonged coastal undersaturation can occur today with the input of large volumes of freshwater from high-rainfall tropical cyclones.

The relatively shallow depths (~2–3 m) and restricted circulation within a bay ecosystem are environmental characteristics that contributed to the severity of acidification in Galveston Bay. Of the top ten wettest tropical cyclones in US history, nine have resulted in high maximum rainfall (≥985 mm) over short periods of time (3–4 days) near shallow, semi-enclosed bays (Table 2). While the duration of acidification in Galveston Bay was extended due to the manual release of stormwater from reservoirs for over a month after the storm, the severity of acidification was principally due to the extreme rainfall associated with Harvey. Thus, although the stochastic nature of tropical cyclones limits the availability of pre- to post-hurricane carbonate chemistry studies, it is possible that previous instances of tropical cyclone-induced coastal undersaturation have occurred but were not recorded. For example, in 2018 Hurricane Lane brought extreme rainfall and flooding to the area around Hilo Bay, Hawaii and concerns arose regarding potential impacts to coastal water quality32. While ocean exchange is greater in Hilo Bay compared to Galveston Bay, the total bay volume is considerably smaller, and the Lane rainfall maximum was only 4% less than Harvey (Table 2). Therefore, it is possible that, while not recorded, Hilo Bay may have experienced a short-term coastal acidification event that reached undersaturation following Lane. In addition, areas of the continental US that are particularly prone to tropical cyclones, such as the Gulf Coast, Florida, and the southeast US coast33 are also home to extensive lagoonal systems where cyclone-induced acidification would be most likely34. As climate change progresses and high-rainfall storms become more frequent13,14, storm-induced coastal acidification will also become more common and severe, making these extreme weather events an increasing threat, particularly for coastal calcifying ecosystems including coral and oyster reefs.

In addition to causing intense coastal acidification, Harvey stormwaters caused prolonged low salinity conditions in Galveston Bay that led to a freshwater oyster mortality event, with some reef complexes in the eastern bay experiencing up to 100% mortality20. Galveston Bay oyster mortality also occurred following Hurricane Ike in 2008 but was caused by burial of oysters under sediment19. In contrast, mortality caused by extended freshwater exposure post-Harvey resulted in clean, dead shells remaining at the surface of the reefs, providing ideal substrate for larval settlement. While substrate is a critical factor in larval settlement, undersaturated water can prolong the time oyster larvae spend in the water column before settling and increase energetic requirements for metamorphosis to the spat stage2, thereby creating unfavorable conditions for oyster larval recruitment and survival. In fact, despite the presence of ideal substrate post-Harvey, oyster recruitment remained low in East Bay reefs compared to reefs in the central bay through June 2022 (unpublished data from Texas Parks and Wildlife Department). However, the exact role of acidification in depressed oyster spat numbers is still unclear and requires further investigation. Along the US Gulf and Southeast coastlines, the oyster spawning season generally overlaps with hurricane season. Thus, storm-induced acidification following high-rainfall events has the potential to negatively affect oyster reef health and post-storm recovery, as well as threaten the ecosystem services and fishery species supported by these reefs.

Methods

Study site

Galveston Bay is the largest of twelve estuaries along the coast of Texas, covering an area of approximately 1500 km2 (94.5–95°W and 29.2–29.8°N) and an average water depth of 2–3 m35 (Fig. 1). It sits in one of the most industrialized and urbanized areas on the Texas coast, with more than half of the Texas population living within the Galveston Bay watershed, including the populations of Houston and Dallas-Fort Worth. The Trinity River, San Jacinto River, and Buffalo Bayou are the major sources of freshwater to the bay16,35 (Fig. 1c). The bay receives a mean river inflow of 350 m3 s−1 annually, with most of this inflow from the Trinity River (~77%) entering the bay from the northeast, and the San Jacinto River (~19%) entering the northwest side through the Houston Shipping Channel16 (Fig. 1c). The bay is vertically well-mixed, with a spatial gradient in salinity, which increases toward the mouth of the bay where it connects to the Gulf of Mexico through the channel between Galveston Island and the Bolivar Peninsula known as Bolivar Roads25. The residence time of the water in the bay varies from <1 day to more than 45 days. The longest residence times occur in the regions farthest removed from the mouth of the bay, including the northern end of the bay where the Trinity River enters, and the eastern arm of the bay known as East Bay36.

Study setup

Samples were collected at 14 different sites quarterly from June 2017 through September 2018 in Galveston Bay and at 10 sites along the Texas coast in the Gulf of Mexico in June, August, and November of 2017 (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S2). This time frame allows us to assess both the immediate impact following Hurricane Harvey (September 2017) and the recovery of the bay ~1 year out from the storm (September 2018). The 14 study sites in Galveston Bay were established to characterize the range of environments within the bay, including near the two major freshwater sources (sites 11 and 14), the mouth of the bay (1–3), the center of the bay (6, 7, and 9), and near the oyster reefs in East Bay (5 and 8) (Fig. 1c). Not all sites were sampled during every cruise due to time and vessel restrictions. Stations in the Gulf of Mexico were selected less than 60 km offshore for the upper 15 m of the water column to characterize the seawater transported into the bay. The 15 m depth restriction is based on the approximate depth of the ship channel that runs from the bay entrance to the Port of Houston37.

Water sample collection and analysis

Discrete water samples were collected with a Niskin (General Oceanics) bottle at the surface (0.5 m) and 1.2 m off the bottom (referred to as the bottom sample hereafter). The depth of the bottom samples ranged from 0.5 to 7.2 m. The water samples were transferred from the Niskin to 250 mL narrow-mouth borosilicate glass bottles using a 0.2 μm polypropylene Whatman Polycap 36 Tissue Culture Grade (TC) in-line filter for total alkalinity (TA) and dissolved inorganic carbon (DIC) analysis, leaving approximately 5 mL headspace for thermal expansion. Some samples in September and November 2017 were collected using 0.2 μm Whatman Polycap 36 Aqueous Solution (AS) filters, which because of their glass microfiber substrate could theoretically alter the TA of the sample as it was transferred. However, no significant difference was found in the carbonate chemistry analysis for samples using either filter, therefore no distinction is made from here on (Supplementary Table S4). Each sample was poisoned with 100 μL saturated mercuric chloride solution immediately after collection to inhibit biological activity, and then sealed with silicone-free type L Apiezon grease and ground glass stoppers with rubber bands and plastic clamps38. Conductivity, temperature, and depth (CTD, SonTek Castaway™) profiles were conducted concurrently with Niskin samples at each station.

TA and DIC were analyzed simultaneously on a Versatile INstrument for the Determination of Total inorganic carbon and titration Alkalinity (VINDTA) 3C. The VINDTA uses coulometric titration for DIC analysis and an open cell potentiometric titration for TA analysis. DIC and TA measurements were calibrated using certified reference materials (CRMs) obtained from Dr Andrew Dickson at Scripps Institute of Oceanography39. The mean precision for these samples was ±2.5 and ±2.0 μmol kg−1 or better for DIC and TA analyses, respectively. A small subset of duplicate samples (13) collected in September and November 2017 were sent to Dr Andrew Dickson at Scripps Institution of Oceanography for TA/pH analysis to compare to our results for samples with low salinity (S < 20; Supplementary Table S5).

The remaining carbonate system parameters (e.g., pH, pCO2, Ω) were calculated using CO2SYS40 and the constants from Millero41 suggested for estuarine waters. Carbonate chemistry parameters calculated with Lueker et al.42 constants recommended for seawater (S > 15) are also shown in Fig. 2 for comparison. Duplicate samples measured for TA and pH by Dr Andrew Dickson’s lab (Supplementary Table S5) produced lower calculated Ωca and Ωar compared to those calculated from our TA and DIC analyses, by 0.57 and 0.34 on average, respectively, using Millero41 constants. Therefore, the Ω reported here may be a conservative (i.e., slightly high) estimate of Ω in Galveston Bay.

pCO2 was normalized (npCO2) to the average temperature over our sampling period in Galveston Bay (25.9 °C) following the procedure from Takahashi et al.43 to remove the effect of temperature on pCO2 variation. Linear regression analysis was performed for each sampling timepoint for TA-Salinity, DIC-Salinity, and TA-DIC relationships. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on the average values for TA, DIC, pH, pCO2, Ωar, Ωca, and salinity to determine significant differences (p < 0.05) between sampling timepoint averages (summarized in Supplementary Table S6). Multiple comparison was used to further identify significant differences for samples collected 2–3 weeks post-Harvey (September 2017) from the ANOVA results (summarized in Supplementary Table S1).

Water composition fractional analysis

Mixing fractions were calculated for each Galveston Bay sample assuming ternary mixing, or three-endmember mixing. The three endmembers for this analysis are Gulf of Mexico (GOM) seawater, Galveston-watershed river water, and rainwater. Rainwater has a unique carbonate chemistry signature compared to river water due to the lack of rock weathering reactions that alter the carbonate chemistry of river water, resulting in two freshwater endmembers with distinct carbonate chemistry signatures.

A Deffeyes diagram26 of TA vs DIC indicates that our TA and DIC data fall within the mixing envelope defined by the three endmembers (Fig. 3). While it is likely that respiration is occurring in the bay ecosystem, the Deffeyes diagram26 indicates that any biological signal in our carbonate chemistry data is overwhelmed by physical mixing effects. Based on this, here we assume TA to be a conservative tracer in our study. This results in the following system of linear mixing equations:

Where fi represents the fractional contribution, CC represents the relevant carbonate chemistry parameter (i.e., TA), and S represents the relevant salinity value of each ith water endmember. The fractional contributions (fi) of GOM seawater and Galveston-watershed river water were determined using TA derived from TA-salinity (TA-S) regressions (TAS) during non-storm (i.e., excluding the post-hurricane sampling in September and November 2017) conditions (see Supplementary Figs. S2 and S5 for TA-salinity regressions for river water and seawater, respectively). In addition to TA, we calculated the fractions using DIC derived from non-storm DIC-salinity (DIC-S) regressions (DICs) for comparison and to provide another avenue to investigate biological influences, since DIC is more strongly impacted by non-conservative effects than TA, including photosynthesis, respiration, and air-sea CO2 exchange. The results show no significant difference between fractions calculated using TAs verses DICs, indicating that physical mixing is likely the dominant factor influencing Galveston Bay TA and DIC during our study, in agreement with the mixing envelope analysis (Fig. 3). Fractional analyses results using both TAs and DICs are included in Supplementary Data 1 for comparison. The endmember values used in the calculations are summarized in Supplementary Table S3.

To determine the average salinity of seawater entering Galveston Bay, salinity data were downloaded at half-hourly intervals from the Texas Automated Buoy System (TABS) Buoy B (28.98°N, 94.90°W; http://pong.tamu.edu/tabswebsite/; Fig. 1b) for September 1, 2011 to September 23, 2018. We applied quality assurance for real-time oceanography data (QARTOD) standards to the raw data to exclude outliers and extreme values. The Gulf of Mexico endmember TAS and DICS were calculated for the median salinity (S = 31.7) and the upper and lower quartiles (S = 33.5 and 29.3, respectively) of the Buoy B data from the linear regression of surface (≤15 m) TA or DIC as a function of salinity for the Gulf of Mexico cruises listed in Supplementary Table S2 (Supplementary Fig. S5). The salinity median value and upper/lower quartiles were used to quantify the average conditions as the salinity data has a left skewed distribution; however, calculations with mean and standard deviation yielded no significant difference in results.

The river endmember salinity was assumed to be ~0. The river endmember TA and DIC were calculated as the average of the y-intercept (S = 0) of the TA-S and DIC-S linear regressions for each Galveston Bay cruise, excluding the post-hurricane sampling in September and November 2017 (Supplementary Fig. S2). It was assumed that under non-storm conditions, the Galveston Bay zero salinity intercept primarily represents the TA and DIC of Galveston-watershed river water, rather than a combined rainwater–river water endmember (i.e., TAFW and DICFW), since the majority of freshwater entering Galveston Bay is river water. Annual precipitation falling directly onto the bay accounted for <10% of the total freshwater delivered in both 2017 and 201844. In addition, to determine the TA and DIC of river water entering Galveston Bay, carbonate chemistry samples were collected in June 2019 from the Trinity (TA = 2050 ± 28 and DIC = 2177 ± 2 μmol kg−1) and San Jacinto (TA = 1022 ± 109 and DIC = 1125 ± 102 μmol kg−1) rivers. River endmember TA and DIC estimates, based on the June 2019 river samples and the average contribution to the bay from the Trinity (~80%) and the San Jacinto (~20%) rivers, are 1844 and 1966 μmol kg−1, respectively, consistent with the river endmember estimates calculated from the Galveston Bay TA-S and DIC-S linear regressions for June 2017 and 2018 (Supplementary Fig. S2). If rainwater had a significant effect on the river endmember TA-S and DIC-S regression estimates during non-storm conditions, the regressed values would be lower than the sample estimates, given the very low TA and DIC of rainwater (see the following paragraph for rainwater TA and DIC estimates). Therefore, the zero salinity intercepts of the TA-S and DIC-S regressions are likely reasonable estimates for the river water endmembers in our study during non-storm conditions (Supplementary Fig. S2). It is possible that the carbonate chemistry and TA-S and DIC-S relationships in Galveston Bay are influenced by submarine groundwater discharge (SGD) entering the bay. Global Positioning System (GPS) satellite data were used to show that approximately 14% of the total stormwater released by Harvey across Texas and Louisiana was eventually lost from the region through groundwater flow over ~6 weeks45. In addition, the slow recovery time (~1 month) of streamflow in an upper section of the Trinity River (6 km from the river mouth) was speculated to be due to groundwater flow entering the river16. However, the volume, discharge rate, and carbonate chemistry of SGD that entered Galveston Bay following Harvey, as well as during non-storm conditions, is unknown. Although we are unable to quantify the impact of SGD on Galveston Bay carbonate chemistry, the agreement between our river data and the zero salinity intercepts of our bay TA-S and DIC-S regressions suggest that under non-storm conditions, SGD is a minor component of the freshwater flux to the bay.

Rainwater was assumed to have both a salinity and TA of ~0. Rainwater DIC was calculated two ways to ensure consistency of the estimate. The first assumed a pH of 5.4 for rainwater based on the analysis conducted by Mullaugh et al.46 (consistent with average rainwater pH) and an average atmospheric pCO2 of 405 ppm in 201747. The DIC was then calculated with Eq. (4), assuming equilibration with atmospheric pCO2 and ideal conditions,

where kH is Henry’s law constant (10−1.5 M atm−1 at 25 °C) and k1 and k2 are equilibrium constants for the carbonate system (k1 = 10−6.3 and k2 = 10−10.3). Equation (4) yields a rainwater DIC of 14.4 μmol kg−1. Rainwater DIC was also calculated using the WEB-PHREEQ online application to equilibrate atmospheric CO2 with pure water at 25 °C, assuming an atmospheric pCO2 value of 405 ppm48. This results in a DIC of 16.3 μmol kg−1, which is within the measurement precision of the estimate from Eq. (4). Note that in contrast to the river water and GOM seawater endmembers, the rainwater endmember has a negative [TA-DIC]27.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data in this study are publicly available from the Biological and Chemical Oceanography Data Management Office, Project #809503 at https://www.bco-dmo.org/dataset/881549.

References

Costanza, R. et al. The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387, 253–260 (1997).

Miller, A. W., Reynolds, A. C., Sobrino, C. & Riedel, G. F. Shellfish face uncertain future in high CO2 world: influence of acidification on oyster larvae calcification and growth in estuaries. PLoS One 4, e5661 (2009).

Speights, C. J., Silliman, B. R. & McCoy, M. W. The effects of elevated temperature and dissolved ρCO2 on a marine foundation species. Ecol. Evol. 7, 3808–3814 (2017).

Doney, S. C., Busch, D. S., Cooley, S. R. & Kroeker, K. J. The impacts of ocean acidification on marine ecosystems and reliant human communities. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 45, 83–112 (2020).

IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2014).

Wallace, R. B., Baumann, H., Grear, J. S., Aller, R. C. & Gobler, C. J. Coastal ocean acidification: the other eutrophication problem. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 148, 1–13 (2014).

De’ath, G., Fabricius, K. E., Sweatman, H. & Puotinen, M. The 27–year decline of coral cover on the Great Barrier Reef and its causes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 17995 (2012).

Brown, K. T. et al. Habitat‐specific biogenic production and erosion influences net framework and sediment coral reef carbonate budgets. Limnol. Oceanogr. 66, 349–365 (2021).

Puotinen, M. et al. Towards modelling the future risk of cyclone wave damage to the world’s coral reefs. Glob. Chang, Biol. 26, 4302–4315 (2020).

Torda, G. et al. Decadal erosion of coral assemblages by multiple disturbances in the Palm Islands, central Great Barrier Reef. Sci. Rep. 8, 11885 (2018).

Manzello, D., Enochs, I., Musielewicz, S., Carlton, R. & Gledhill, D. Tropical cyclones cause CaCO3 undersaturation of coral reef seawater in a high-CO2 world. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 118, 5312–5321 (2013).

Gray, S. E. C., DeGrandpre, M. D., Langdon, C. & Corredor, J. E. Short-term and seasonal pH, pCO2 and saturation state variability in a coral-reef ecosystem. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 26, GB3012 (2012).

Knutson, T. R. et al. Tropical cyclones and climate change. Nat. Geosci. 3, 157 (2010).

Knutson, T. R. et al. Global projections of intense tropical cyclone activity for the late twenty-first century from dynamical downscaling of CMIP5/RCP4.5 scenarios. J. Clim. 28, 7203–7224 (2015).

Blake, E. S. & Zelinsky, D. A. Tropical Cyclone Report (AL092017): Hurricane Harvey. National Hurricane Center, 77 (2018).

Du, J., Park, K., Dellapenna, T. M. & Clay, J. M. Dramatic hydrodynamic and sedimentary responses in Galveston Bay and adjacent inner shelf to Hurricane Harvey. Sci. Total Environ. 653, 554–564 (2019).

van Oldenborgh, G. J. et al. Attribution of extreme rainfall from Hurricane Harvey, August 2017. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 124009 (2017).

US Army Corps of Engineers. Galveston District Website: August and September 2017, https://www.swg.usace.army.mil/Media/News-Releases/Year/2017/Month/8/ (2017).

Haby, M. G., Miget, R. J. & Falconer, L. L. Hurricane damage sustained by the oyster industry and the oyster reefs across the Galveston Bay system with recovery recommendations. A Texas AgriLife Extension Service/Sea Grant Extension Program Staff Paper, The Texas A&M University System TAMU-SG-09-201, 51 (2009).

Du, J. et al. Massive oyster kill in Galveston Bay caused by prolonged low-salinity exposure after Hurricane Harvey. Sci. Total Environ. 774, 145132 (2021).

Kurihara, H., Kato, S. & Ishimatsu, A. Effects of increased seawater pCO2 on early development of the oyster Crassostrea gigas. Aquat. Biol. 1, 91–98 (2007).

Talmage, S. C. & Gobler, C. J. The effects of elevated carbon dioxide concentrations on the metamorphosis, size, and survival of larval hard clams (Mercenaria mercenaria), bay scallops (Argopecten irradians), and Eastern oysters (Crassostrea virginica). Limnol. Oceanogr. 54, 2072–2080 (2009).

Gazeau, F. et al. Impact of elevated CO2 on shellfish calcification. Geophys. Res. Lett. 34, L07603 (2007).

Hu, X., Pollack, J. B., McCutcheon, M. R., Montagna, P. A. & Ouyang, Z. Long-term alkalinity decrease and acidification of estuaries in northwestern Gulf of Mexico. Environ. Sci. Technol. 49, 3401–3409 (2015).

Rayson, M. D., Gross, E. S. & Fringer, O. B. Modeling the tidal and sub-tidal hydrodynamics in a shallow, micro-tidal estuary. Ocean Modelling 89, 29–44 (2015).

Deffeyes, K. S. Carbonate equilibria: a graphic and algebraic approach. Limnol. Oceanogr.10, 412–426 (1965).

Xue, L. & Cai, W.-J. Total alkalinity minus dissolved inorganic carbon as a proxy for deciphering ocean acidification mechanisms. Mar. Chem. 222, 107801 (2020).

Thyng, K. M. et al. Hurricane Harvey caused unprecedented freshwater inflow to Galveston Bay. Estuaries Coasts 43, 1836–1852 (2020).

Hu, X. et al. Disparate responses of carbonate system in two adjacent subtropical estuaries to the influence of Hurricane Harvey – a case study. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 26 (2020).

Yan, G., Labonte, J. M., Quigg, A. & Kaiser, K. Hurricanes accelerate dissolved organic carbon cycling in coastal ecosystems. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 248 (2020).

Steichen, J. L. et al. Microbial, physical, and chemical changes in Galveston Bay following an extreme flooding event, Hurricane Harvey. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 186 (2020).

Saingam, P., Li, B., Sung, S. & Yan, T. Immediate impact of Hurricane Lane on microbiological quality of coastal water in Hilo Bay, Hawaii. Environ. Sci. Technol. 55, 2960–2967 (2021).

National Hurricane Center. Tropical Cyclone Climatology, https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/climo/ (2021).

Dürr, H. H. et al. Worldwide typology of nearshore coastal systems: defining the estuarine filter of river inputs to the oceans. Estuaries Coasts 34, 441–458 (2011).

Roelke, D. et al. Co-occurring and opposing freshwater inflow effects on phytoplankton biomass, productivity and community composition of Galveston Bay, USA. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 477, 61–76 (2013).

Rayson, M. D., Gross, E. S., Hetland, R. D. & Fringer, O. B. Time scales in Galveston Bay: an unsteady estuary. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 121, 2268–2285 (2016).

Du, J. et al. A hydrodynamic model for Galveston Bay and the shelf in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Ocean Sci. 15, 951 (2019).

Shamberger, K. et al. Calcification and organic production on a Hawaiian coral reef. Mar. Chem. 127, 64–75 (2011).

Dickson, A. G., Sabine, C. L. & Christian, J. R. (eds). Guide to Best Practices for Ocean CO2 Measurements. 3 (PICES Special Publication, 2007).

MS Excel program developed for CO2 system calculations. Oak Ridge National Laboratory, US Department of Energy, Oak Ridge, Tennessee (2006).

Millero, F. Carbonate constant for estuarine waters. Mar. Freshwater Res. 61, 139–142 (2010).

Lueker, T. J., Dickson, A. G. & Keeling, C. D. Ocean pCO2 calculated from dissolved inorganic carbon, alkalinity, and equations for K1 and K2: validation based on laboratory measurements of CO2 in gas and seawater at equilibrium. Mar. Chem. 70, 105–119 (2000).

Takahashi, T. et al. Climatological mean and decadal change in surface ocean pCO2, and net sea–air CO2 flux over the global oceans. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. DEEP-SEA RES PT II 56, 554–577 (2009).

Neupane, R. & Schoenbaechler, C. Coastal hydrology for the Trinity-San Jacinto Estuary. Coastal Science Program, Texas Water Development Board, Austin, Texas (2021).

Milliner, C. et al. Tracking the weight of Hurricane Harvey’s stormwater using GPS data. Sci. Adv. 4 (2018).

Mullaugh, K. M., Willey, J. D., Kieber, R. J., Mead, R. N. & Avery, G. B. Jr. Dynamics of the chemical composition of rainwater throughout Hurricane Irene. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 13, 2321–2330 (2013).

Dlugokencky, E. et al. Long-lived greenhouse gases [in “State of the climate in 2017”]. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 99, S46–S49 (2018).

Saini-Eidukat, B. & Yahin, A. Web-phreeq: a WWW instructional tool for modeling the distribution of chemical species in water. Comput. Geosci. 25, 347–353 (1999).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Serena Smith, Miranda Hooper, Cody Padlo, Samantha Longridge, Cameron Henderson, and Andrea Kealoha for assisting in sample collection and analyses. Thanks to Shari Yvon-Lewis, Stanford Goodwin, Damian Simonini, J.N.F., and all the other faculty and students who contributed to the Galveston Bay time series expeditions. Funding was provided by the National Science Foundation (OCE #1760381 to S.F.D. and K.E.F.S.; OCE #1800913 to K.E.F.S.), Texas Governor’s Fund through the Texas OneGulf Center of Excellence, Texas A&M University (TAMU) Department of Oceanography, TAMU College of Geosciences, two TAMU T3 Triad grants to J.N.F. and K.E.F.S., respectively, and Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ). T.L.H. was supported by a TAMU College of Geosciences Graduate Merit Fellowship. Publication supported in part by the Texas Sea Grant College Program at Texas A&M University. Unpublished data provided by Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. WEB-PHREEQ is part of an instructional module for Geochemistry 428/628 at North Dakota State University. Many thanks to David Parkhurst and his crew for developing PHREEQC. The web implementation © B. Saini-Eidukat, Andrew Yahin, and Tim Mooney.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.L.H. designed study, performed sample and data analyses, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. K.E.F.S. designed and funded study, assisted in sample and data analyses, interpreted data, advised T.L.H. in writing the manuscript, and read/edited the manuscript. J.N.F. funded the study, assisted in data analysis and interpretation, and read/edited the manuscript. C.C.J. provided data and read/edited the manuscript. S.F.D. helped fund the study, assisted in data analysis, and read/edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Zong-Pei Jiang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Clare Davis.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hicks, T.L., Shamberger, K.E.F., Fitzsimmons, J.N. et al. Tropical cyclone-induced coastal acidification in Galveston Bay, Texas. Commun Earth Environ 3, 297 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00608-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00608-1

This article is cited by

-

Assessment of Nivar and Burevi Cyclone Impact on Meiobenthic Community Structure at Sandy Beach and Estuary of Puducherry Veerampattinam Coast, South India

Thalassas: An International Journal of Marine Sciences (2025)