Abstract

Malaria is one of the major health threats in Africa, and the risk of transmission is projected to be exacerbated by global warming. Rwanda experienced an 11-fold increase in malaria incidence from 2011 to 2015 despite extensive funding and implementation of control measures. Here, we focus on Rwanda as a case study and simulate monthly malaria incidence between 2010 and 2015, employing an ensemble learning method. Next, we project future malaria prevalence using shared socio-economic pathways (SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5). We find that the projected increases in temperature and precipitation may shift malaria transmission risk to the highlands of western and northern Rwanda. These two regions that currently experience low malaria transmission. The seasonal effects of malaria incidence may be less apparent from January to June, and the peak season for malaria transmission in the highlands could occur one month earlier. Our findings highlight the impacts of climate change on malaria epidemics in Rwanda, which have implications for other world regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malaria remains as one of the most substantial public health challenges in the Global South, especially in sub-Saharan Africa and Southeast Asia1,2,3. As a representative region of the Global South, Africa accounted for 95% of global malaria cases in 20214. Fortunately, the effectiveness of control measures against Plasmodium falciparum has reduced the incidence of clinical malaria by 40% in Africa between 2000 and 20153,5. However, some regions in Central Africa, especially those countries with savannah climates (e.g., Rwanda, Nigeria and the Republic of the Congo), still experience a large number of malaria cases due to local environmental conditions. For example, Rwanda—one of the most densely populated countries in Africa—experienced an increase in malaria cases from 0.64 million in 2010 to 3.4 million in 20166. As a result, Rwanda is one of the countries with the highest incidence of malaria in Africa, with approximately 90% of all Rwandans at high-risk6, even if a considerable amount of funding was consistently allocated to mitigate malaria risk efforts during this period.

To help mitigate global risk of malaria incidence, previous studies have developed mathematical models driven by precipitation and temperature to simulate mosquito population (e.g., birth and bite rates of adult mosquitoes) and malaria-vulnerable, exposed, and infected human populations2,7,8,9,10. Forecasted changes in global malaria transmission patterns pointed the changes in the seasonal and spatial characteristics of future malaria risk as an important concern under various climate change scenarios8,11,12,13. Furthermore, most dynamic malaria models also considered the time-lag effect of precipitation and temperature on the life cycles of mosquitoes and their sporogonic cycles to improve malaria forecast10,14. These results can support local governments in generating evidence-based policies and control measures to effectively mitigate malaria risk under a warming climate. These models mainly relied on a linear growth assumption to predict the densities of future infected human populations and malaria transmission. However, according to the United Nations projection of the world population15, Africa is experiencing an exponential increase in its population. The integrated population growth of African countries may contribute to more than 50% of global growth by 2050. This rapid population change is expected to have a pronounced effect on the intensity of malaria transmission in the Global South, especially in African countries. Specifically, population growth is likely to increase exposure and thereby enhance transmission. On the other hand, a growing urban population means better access to medical services and healthcare infrastructure, which, in turn, would reduce levels of malaria transmission16. Furthermore, altitude plays a fundamental role in temperature variation; for example, high elevation areas, characterised by cooler temperatures, are typically less prone to mosquito development, resulting in lower malaria incidence17. Therefore, we believe that the malaria projections that incorporate human populations and elevation information would further improve future malaria assessments.

This study conducted a comprehensive malaria risk assessment to evaluate the spatiotemporal variability of malaria incidence in Rwanda. Rwanda is representative in research because of its suitable climate conditions and rapid population growth, and it can serve as a reference for other malaria-endemic countries because of its extensive experience in malaria control. The Rwanda Malaria Operational Plan FY 201718 highlighted a potential mechanism of local transmission due to a multifaceted interplay of various factors, including increased temperature, modification of rainfall and agricultural lands, a substantial decline in the coverage of insecticide-treated mosquito nets (ITNs), increased mosquito resistance to pyrethroid insecticides, increased availability of rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) and artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs). The Rwandan government has also developed several strategic plans, including vigilant monitoring of insecticide resistance, a rigorous biannual rotation of insecticides and prioritisation of high-risk malaria transmission regions, with a primary focus on the distribution of long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) in districts with high malaria burden19,20. However, the relationship between changing climatic factors and malaria incidence has not been sufficiently investigated at the regional scale, hindering the effectiveness of malaria control strategies21.

In recent decades, Rwanda has taken good steps to alleviate the burden of malaria through the effective implementation and expansion of malaria control measures. However, unexpectedly, the incidence of malaria in Rwanda increased after 2011. Malaria cases reached a staggering 2.66 million in 2015, which present a formidable challenge to malaria control efforts in the country. Here, we use Rwanda as an example because Rwanda experienced slight changes in annual total funding (~$42 million) for malaria control between 2010 and 2015 (Supplementary Table 1). This relatively stable funding situation allows us to attribute changes in malaria incidence primarily to meteorological variables, minimizing the impact of changes in malaria control efforts. Therefore, we applied an ensemble learning method, namely, the Random Forest Model (RFM), to comprehensively estimate the effect of changing climate on malaria incidence according to historical observations in Rwanda. Based on this forecasting model, we predicted the future risk of malaria and its spatiotemporal changes under two distinct shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs). Since projections for the impacts of climate change on future malaria transmission at district levels in the Global South have not been rigorously examined, this knowledge is also critical for the development of early warning systems in Rwanda and other malaria-endemic regions.

Results

Spatiotemporal Variability of Malaria Incidence Between 2010 and 2015

Large incidence values in Rwanda are spatially clustered in the east and south during 2010–2015, while the western and northern areas experienced low incidence (Fig. 1a). This spatial pattern suggests that temperature is the main factor affecting malaria incidence but not precipitation, which is associated with local topography (Fig. 1b). In general, elevation in Rwanda is above 1000 metres, with an extensive north-south mountain plateau in western Rwanda. This plateau is above 1500 metres, with some areas reaching approximately 4500 metres. The west-facing slope is steep while east-facing slope is relatively gentle. Consequently, the population of Rwanda is mainly concentrated in the low-elevation eastern and southwestern regions (Fig. 1c). This terrain also induced a rain shadow effect in eastern Rwanda, as a result, higher temperature conditions in the east during 2010–2015 provided optimal conditions for the extrinsic development of mosquitoes even when precipitation was low (Fig. 1d–f). However, when ambient temperatures are below 15–16 °C, the predominant Anopheles mosquitoes cannot develop from eggs to adults22. Due to the absence of optimal temperature conditions (Tmin >16 °C), high rainfall in western Rwanda did not result in a significant malaria transmission as modelled in the eastern part of the country. Observing the monthly dynamics, a distinctive bimodal pattern in malaria incidence becomes evident, featuring double peak seasons in June, the month following the long rain season, and in December, the last month of the short rain season (Fig. 1a, f). The prevailing warm conditions in eastern Rwanda created an ideal habitat for the development of the parasite in the mosquito vector, which promoted malaria transmission (Fig. 1a).

Annual mean pattern of malaria incidence in Rwanda during 2010–2015, with monthly variation of malaria incidence are shown at the top of the map, with black dots indicating endemic areas (a); Map of 30 districts in Rwanda with meteorological stations (red triangles) and topography (contour color) (b); Map of human population distribution (c); (d–f) are the same as (a), but for Tmax, Tmin, and rainfall. Blue areas denote the lakes, and error bar denotes one standard deviation, n = 180. The base map is retrieved from GADM data54.

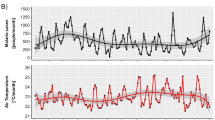

High consistency was observed between interannual variations in malaria incidence and meteorological conditions. Specifically, malaria incidence was lowest in 2011, coinciding with the lowest annual average monthly maximum temperature (Tmax) and minimum temperature (Tmin), and the highest rainfall, conditions that were not suitable for mosquito development (Fig. 2). In contrast, 2015 was the year with the highest malaria incidence, while Tmax and Tmin were the highest and rainfall was the lowest. Generally, both Tmax and Tmin demonstrated a similar pattern of inter-annual variability with malaria incidence, while rainfall displayed an inverse relationship.

Time series of annual-averaged malaria incidence (a), Tmax (b), Tmin (c), Rainfall (d) during 2010–2015. Mean (square), 1st and 3rd interquartile ranges (box caps), minimum and maximum values (whiskers), outliers (asterisk), and the inter-annual trend (dashed line), n = 30. e Accuracy of malaria incidence projections by RFM compared to observed malaria incidence, f Variable importance derived by RFM. Note malaria incidence (MI) scaled by the natural logarithm in the RFM. The variables 1–3 respectively denote the lag effect of the variable for 1–3 months.

Thus, spatiotemporal variability and the intricate interplay among Tmax, Tmin, and rainfall may substantially induce the uncertainty in estimating malaria transmission in specific areas. Furthermore, the time-lag effects of individual or combined meteorological factors play a pivotal role in shaping favourable environments for malaria vectors23. As such, the RFM was developed to incorporate climate variables for the current month along with a delay of 1 to 3 months, acknowledging the lagged effects of temperature and rainfall on the incidence of malaria. Based on the RFM with Tmax (lag 0 to 3 months), Tmin (lag 0–3 months), rainfall (lag 0–3 months), geographic location (latitude and longitude), month of year, elevation and total human population as predictors, our prediction was accurate, with R square (R2), mean square error (RMSE), and mean relative error (MRE) values of 0.79, 0.64, and 24.74%, respectively (Fig. 2e). The main determinants of malaria incidence were human population and geographic factors (latitude and longitude), followed by factors related to elevation and temperature, while all variables of precipitation had the lowest contribution to the model (Fig. 2f). Specifically, rainfall had a strong lag effect on malaria incidence, especially rainfall (lag 2 months). All lagged rainfall values were of greater significance in malaria incidence compared to rainfall in the same month (lag 0 month).

Partial dependent plots of the RFM models further identified a complex spatiotemporal variability between all factors and malaria incidence from 2011 to 2015 (Supplementary Fig. 1). Specifically, the human population had a clear J-shaped association with malaria incidence, with a sharp increase in malaria incidence when the population ranged from 0.3 and 0.4 million people. Geographic locations had relatively linear associations with malaria incidence, where higher incidence tended to be in the south and east. Elevation had a complex association with malaria incidence, with the lowest incidence in areas at approximately 1600 metres between 2010 and 2015. Furthermore, the accelerating effects of Tmin on malaria incidence were high, while the impacts of Tmax variables on malaria incidence were gradual, except for Tmax at a 3-month lag. Importantly, rainfall in the current month showed a gradual negative association with malaria incidence, while rainfall at a 1-month lag and at a 2-month lag showed a positive association, especially rainfall at a 2-month lag. These results underline the delayed effects of rainfall on malaria incidence in Rwanda.

Seasonal advance and elevation dependence of malaria incidence in the future

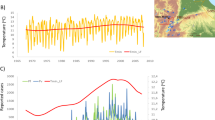

Under both the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios, there is a discernible and substantial increase in both Tmax and Tmin. The complete maturation process of mosquito sporozoites is highly sensitive to temperature, P. vivax in vectors grows at minimum temperatures above 16 °C, whereas P. falciparum develops at temperatures above 18 °C24. It is particularly noteworthy that Tmin basically exceeds 16 °C and 18 °C under both SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5, creating a more favorable environment for the development of the parasite in the mosquito vector (Supplementary Fig. 2b and 2f). In addition, the historical dry season (in 2010–2015) could experience an increase in rainfall in the future, especially under SSP5-8.5. Thus, the dry season is projected to become a susceptible period for future malaria transmission, this finding is consistent with the 2-month lagged relationship between rainfall and observed malaria in 2010–2015. Overall, the increase in temperature and rainfall is expected to create suitable environmental conditions for the development of mosquito vectors, resulting in a marked increase in malaria incidence for both future climate change scenarios (Fig. 3, Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). In terms of seasonal variations, the national average relative change (RC; %) in malaria incidence shows a positive trend under the SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5 scenarios (Fig. 3d, h). The two peak seasons of increased malaria may occur between (1) February to April and (2) August to October, which were historically documented as periods with low malaria incidence during 2010–2015 (Fig. 1a). In the future, a substantial increase in malaria incidence is simulated in the dry season; consequently, seasonal fluctuations in malaria incidence in Rwanda are expected to weaken and fade out from January to June. Ultimately, the malaria incidence pattern is expected to transition to a single peak, with the highest incidence occurring in November and December in future simulations (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Violin plots for absolute changes in Tmax, Tmin, Rainfall and the relative changes in malaria incidence for the periods 2030–2035, 2050–2055, and 2090–2095 under SSP2-4.5 (a–d) and SSP5-8.5 (e–h) in Rwanda compared to 2010–2015. * indicates: p < 0.05, ** indicates: p < 0.01, *** indicates: p < 0.005. White scatters indicate the average, colored scatters indicate distribution, and shadings indicate kernel density estimation.

Additionally, the high-resolution climate simulation indicates that spatiotemporal patterns of variability in malaria incidence will shift to higher altitudes in the future due to global warming (Fig. 4). Under the SSP2-4.5 scenario, the spatial pattern of RC in malaria incidence shows a positive trend over the central plateau region for 2030–2035, including the Muhanga, Nyamagabe and Rubavu districts. Similarly, Ruhango and Kamonyi will cluster with the aforementioned districts, experiencing more prevalent malaria transmission during 2050–2055. Furthermore, the projection for 2090–2095 shows that there will be three more districts (Nyamagabe, Nyamasheka and Muhanga) with annual malaria prevalence >1% compared to 2010–2015 (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 3). Notably, the model shows a marked increase in malaria incidence in the mountainous areas in the northern region under both SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5. Historically, the northern part has recorded fewer malaria cases, primarily due to its lower temperatures. However, it is expected that the northern region will become more suitable for malaria transmission in the future, driven mainly by the increase in Tmax and Tmin. For low altitudes, where malaria transmission is already a concern, warmer temperatures can alter the parasite growth cycle in mosquitoes, with faster development, ultimately amplifying the local malaria burden25. Districts with high variability in malaria incidence are projected to gradually shift from medium altitude (~1800 m) to medium high altitude (1800–2000 m) by the 2090 s. While malaria classes are not expected to change in most parts of Rwanda in the future, the duration of malaria transmission season might lengthen in eastern and southern Rwanda in the future. Approximately 15 districts are projected to experience 6-month transmission season by 2090–2095 according to SSP5-8.5, and 12 districts are expected to become year-round endemic areas (Supplementary Fig. 4). Additionally, the human population is the most important variable in predicting malaria incidence, while future changes in malaria incidence are characterised primarily by seasonal variation, as well as elevation dependence through the influences on temperature and humidity. These seasonal and spatial variations in malaria incidence are largely attributable to projected changes in rainfall (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Spatial pattern of relative change (%) in malaria incidence (denoted as RC in MI) for the periods 2030–2035, 2050–2055, and 2090–2095 under SSP2-4.5 (a–c), SSP5-8.5 (d–f). The scatter in the subplot on each panel indicates the relationship between RC in MI and elevation, while the solid line represents the fitted Gaussian curve relating RC in MI to elevation, and blue areas indicate the lakes. The base map is retrieved from GADM data54.

Due to the co-effect of meteorological factors and elevation in the future, a change in the peak season of malaria incidence is also found from the simulation. Specifically, in high-elevation western Rwanda, future warmer temperatures, supported by the rainy season, may lead to more severe malaria epidemics. In the low-altitude areas of eastern and southern Rwanda, the peak season for malaria is largely influenced by changes in precipitation in the previous 1–2 months, due to the lag effect of precipitation. As a result, the peak of future malaria incidence will shift to a later time in December in southeastern Rwanda and to an earlier time in November in western Rwanda. For the eastern region, the future peak in malaria incidence will still occur in December as it did in 2010–2015 (Fig. 5 and S6). Generally, high variability in future malaria incidence at high elevations, including a marked increase and an earlier peak season of malaria incidence, should be of concern for citizens and malaria control policymakers, as it matters for future malaria prevention and control priorities.

Spatial pattern of shift in the month of peak season of malaria incidence for the periods 2030–2035, 2050–2055, and 2090–2095 under SSP2-4.5 (a–c) and SSP5-8.5 (d–f). Green means an earlier occurrence, fuchsia means a later occurrence, white means no change, and blue areas indicate the lakes. The base map is retrieved from GADM data54.

Discussion

Our results reveal a pronounced change in future malaria incidence in Rwanda under different climate change scenarios (SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5). In the western and northern highlands of Rwanda, currently experiencing low malaria transmission, malaria incidence is projected to face an exponential increase in the future, likely due to increases in temperature and precipitation. This change is likely to create a more favorable environment for Plasmodium-carrying mosquito breeding and survival at higher altitudes26. Furthermore, seasonal variation in malaria transmission is expected to differ significantly from the present pattern. The bimodal malaria transmission season has a high probability of shifting to a single peak pattern in Rwanda in the future, extending the duration of the transmission season. Changes in precipitation patterns will emerge as the predominant driver of seasonal and spatial variability in malaria (Supplementary Fig. 5), with increasing rainfall in January and lag effects that might enhance mosquito habitability and reduce seasonal differences in the first half of the year in the future. The peak malaria season in the western and northern highlands is likely to occur earlier approximately one month due to seasonal shift in precipitation. In summary, temperature changes create conducive conditions for malaria transmission. This statement, is supported by studies have already confirmed that climate change is already exacerbating malaria transmission in the eastern African highlands17,27. Not only do the results of RFM in this study, but other dynamical malaria models driven by climatic factors also forecast an increase in malaria burden in the Indian and African highlands in the future9,13,26,28. Furthermore, our results suggest that the projected future shift in the high variability of malaria incidence and its peak seasons should be of concern to the relevant public health stakeholders in Rwanda and other countries with similar environmental conditions.

The impacts of climate change on the dynamics of malaria have been widely debated. Some studies have stated that climate fluctuations only exert a relatively minor influence on malaria transmission, with their effects considerably overshadowed by factors such as the state of public health infrastructure, resistance to antimalarial drugs, reductions in mosquito control measures, population growth, and migration patterns27,29. In contrast, other studies highlighted that climate change will have a non-negligible influence on malaria transmission dynamics2,9. Evidently, the recent increase in malaria incidence observed in East African highland regions and specific South American countries is linked, in part, to the early impact of global warming13,17,30. Climate change will directly or indirectly impact the evolving vulnerability of populations and their ability to address and respond to disease burdens8,31,32,33. Specifically, rainfall, temperature, and humidity play a central role in modulating malaria incidences, through their impacts on ecosystems, parasite life traits and mosquito survival34,35,36,37. Projections on the impacts of future climate change underscore the increased susceptibility to malaria resurgence in specific regions of East Africa and Ethiopia by 205035,38. Furthermore, another study predicted that previously malaria-free African highlands (including the western highlands of Rwanda) may become endemic by 204013.

Specifically, malaria control measures are paramount for reducing and eliminating malaria39. Since 2007, Rwandan health authorities have developed more flexible and detailed malaria control interventions, prioritizing high-risk regions with limited resources20. For example, funding and malaria control programs implemented by relevant authorities since 2008 have prioritized the distribution of LLINs and indoor residual spraying in areas with high malaria endemicity20. Furthermore, high-burden malaria areas have also been prioritized for insecticide spraying before the rainy season18. As reported, Rwanda reduced malaria cases by at least half from 2005 to 2010 after expanding control interventions40. However, these measures have also led to a reduction in malaria control coverage and a failure to provide adequate and timely malaria control interventions in areas of lower risk. In particular, Rwanda has experienced a persistent surge in malaria across its 30 districts since 2012, despite stable malaria control funding efforts. The country attributes this to meteorological factors such as increased temperature and rainfall, mosquito insecticide resistance, and low coverage of malaria control interventions18,41. Indeed, changes in the climatic environment directly affect the growth of Plasmodium-carrying mosquitoes, thereby influencing malaria transmission8. Therefore, changes in endemic areas and seasonal variations in malaria due to climate change must be considered in future malaria control measures undertaken by relevant authorities. Our study reveals a substantial increase in malaria incidence during the off-season due to climate change. Consequently, sustained insecticide spraying initiatives and ITN distribution should be extended throughout the year, especially before the peak season. Given the projected year-round prevalence of malaria, it is recommended that the insecticide rotation be adjusted to the corresponding pre-peak months (August–October) to mitigate vector resistance. Furthermore, ongoing prioritization of high-risk malaria regions is crucial to prevent post-control resurgence, necessitating stringent control measures in potential malaria surge areas (e.g., west-central Rwanda) to prevent them from becoming high-burden zones.

This model still has some limitations. Firstly, to improve predictive accuracy and provide more scientifically robust recommendations for malaria elimination, it is useful to consider quantifiable indicators related to mosquito resistance and malaria interventions. While such data were not available in this study, future research should include them. Secondly, to enhance the modelling outcomes, it is necessary to include longitudinal evaluations of mosquito resistance to specific insecticides and variables such as the allocation of malaria funding and the coverage of insecticide-treated bed nets in the training regimen of the RFM. Hence, further research on this topic should be carried out. Finally, establishing models to project global malaria trends is a forthcoming endeavor, contingent on, for instance, the accumulation of more extensive health and climate data at the district level. This type of database is vitally important for Rwanda and other African countries experiencing malaria transmission.

In summary, evaluating the impact of climate change on malaria incidence contributes to the development of more targeted and sustainable public health policies, drives actions for adaptation and mitigation of climate change, and fosters international collaboration to address this global health challenge.

Materials and methods

Study area

Rwanda, despite its relatively small area (26,338 km²), is one of the most densely populated countries in Africa42. In 2015, 19 of its 30 administrative districts were classified as at-risk areas, and 90% of the population faced a high risk of malaria exposure18. Generally, malaria transmission in Rwanda persists throughout the year in endemic regions with two distinct peak seasons (May to June and November to December)43. These peaks are associated with two rainy seasons throughout the year. Due to the topography of Rwanda, eastern areas with lower altitudes are at higher risk of malaria parasitemia than other regions40,44. The diverse topography of Rwanda, with elevations ranging from 1000 to 4500 meters above sea level, offers an ideal case study for examining the impact of future climate warming on malaria transmission at different altitudes.

Collection of retrospective and observational data

Monthly malaria cases (2010–2015) were recovered from the Rwandan Health Management Information System (HMIS). Monthly Tmin, Tmax, and rainfall data for 30 districts were retrieved from the Rwanda Meteorological Agency (specific locations of meteorological sites are shown in Fig. 1b).

It is important to note that HMIS provided the most complete, accurate, and timely information for routine program monitoring of diseases at the national level. PMI (President’s Malaria Initiative), Global Fund, and the Malaria and Other Parasitic Diseases Division (MOPDD), in collaboration with the HMIS Unit at the Rwanda Biomedical Center (RBC) also conduct annual data quality audits (DQA) across the country to validate HMIS data. Thus, Rwanda’s surveillance, monitoring, and evaluation (SM&E) systems constitute one of the most robust and comprehensive SM&E systems in Africa18.

To stratify the extent of malaria transmission, endemicity classes are identified by annual prevalence rates (PR) in children (malaria-free areas for PR < 1%, hypoendemic areas for 1 ≤ PR < 10%; mesoendemic areas for 10 ≤ PR < 50%; hyperendemic for 50% ≤ PR < 75% and holoendemic areas for PR ≥ 75%)45,46. In the absence of infection rates in children, we identified endemic areas with an PR for all-age greater than 1% and examined the duration of malaria endemic transmission.

Climate and population data projections and downscaling

This study employed eight General Circulation Models (GCMs) based on the accessibility of monthly data for Tmin, Tmax, and rainfall from the sixth phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP6) archives47. To ensure the fairness and consistency of the data, GCMs (e.g., ACCESS-CM2, CanESM5, IPSL-CM6A-LR, GFDL-ESM4, MIROC6, MPI-ESM1-2-HR, CMCC-ESM2, BCC-CSM2-MR) were selected with variant labels of r1i1p1f1 (details about these GCMs can be found in Supplementary Table 2). The data used in this article comprise a set of historical simulations (2010–2015) and future projections (2030–2100) under two distinct SSPs, namely, SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5. Global mean air temperature at the end of the 21st century is expected to increase by approximately 1.27 to 3.00 °C under the SSP2-4.5 scenario and 2.40 to 5.57 °C under SSP5-8.5, relative to the average of 1995–2014. Simulated changes in precipitation show a variation between 4.2% and 7.3% for SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5, which is attributed to greater variability and uncertainty of the model response48.

All gridded climate datasets were interpolated to 1.0° × 1.0° grid using bilinear interpolation. We compared changes in Tmax, Tmin, rainfall, and malaria incidence in the future using two IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) scenarios, SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5, for the periods 2030–2020, 2050–2055, and 2090–2095. Future climate variables in Rwanda’s 30 districts under SSP5-8.5 and SSP2-4.5 were estimated by considering 30-site historical observed meteorological elements and gridded climate change signals from eight GCMs49. For example, monthly meteorological factors for the period of 2030–2035 can be calculated by Eq. (1):

where \({{Observation}}_{{site},2010\mbox{-}2015}\) represents the monthly meteorological factors detected in Rwanda’s 30 districts from 2010 to 2015, and \({\Delta {CMIP}6}_{{Rwanda},2030\mbox{-}2035}\) indicates the differences calculated between 2030–2035 and 2010–2015 using CMIP6 GCMs. Similarly, monthly meteorological factors for the periods 2050–2055 and 2090–2095 are defined by Eqs. (2) and (3), respectively:

Furthermore, the global gridded population data with spatial resolution of 0.5° under SSP2 and SSP550 were taken into account in future predictions of the malaria incidence model. It is worth noting that since the data represent the total population of the grid, we scaled the changes in human population according to the proportion of each district’s area within the grid. Then, the human population of 30 districts was calculated by historical population data and future changes according to SSP2 and SSP5. It is also important to note that the population data is annual, so there is no change in monthly human population data for the same year in our training and validation set of simulation.

Statistical analysis

Linear regression and Pearson’s correlation analyzes were used to explore the relationship between malaria incidence and climate variables. Additionally, trend analysis was conducted to assess the variability of the climate conditions.

Characterised by its use of multiple randomized decision trees, RFM serves as a powerful machine learning technique capable of efficiently discerning and predicting complex nonlinear associations, while offering valuable insights into the importance of variables51. Widely embraced for its versatility, the RFM demonstrates remarkable proficiency in elucidating intricate classifications with unwavering robustness52. To address the issues associated with one-sided test results and limited training data, we used a 10-fold cross-validation technique to assess the accuracy of RFM. Variable importance analysis was also performed based on the estimation of the increase in mean error after removing a specific variable from the model. Partial dependence plots were used to report the non-linear associations between malaria and all factors.

We used RFM to assess and forecast the impact of meteorological factors on malaria incidence. This framework considers the impacts of environmental factors (e.g., monthly Tmax and Tmin, rainfall, and topographic) and human population on malaria cases based on multiple decision tree processing, which improves the prediction of malaria incidence. In addition, taking into account the lag effect of climate factors, lagged variables (e.g., Tmax, Tmin, and rainfall) with delays of 1 to 3 months were included in the model training. This study explored the impacts of climate change on the monthly incidence of malaria within the country, dissecting the implications at the district level under different scenarios of global warming (SSP2-4.5 and SSP5-8.5).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data supporting this article, including meteorological observations and malaria incidence in Rwanda are available in the Zenodo53 at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13143289. Simulations from ACCESS-CM2, CanESM5, IPSL-CM6A-LR, GFDL-ESM4, MIROC6, MPI-ESM1-2-HR, CMCC-ESM2 and BCC-CSM2-MR are available at https://aims2.llnl.gov/search/cmip6. The gridded population data under Shared Socioeconomic Pathways is available at https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.0168350. The base map for Rwanda’s administrative districts is retrieved from GADM data at https://gadm.org/data.html54.

Code availability

The analysis was carried out and the figures were generated using MATLAB R2022b (https://in.mathworks.com/products/matlab.html) and R 4.2.3 (https://www.r-project.org/about.html). These may be shared on reasonable request.

References

Breman, J. G. The ears of the hippopotamus: manifestations, determinants, and estimates of the malaria burden. Am. J. Trop. Med Hyg. 64, 1–11 (2001).

Caminade, C. et al. Impact of climate change on global malaria distribution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, 3286–3291 (2014).

Bhatt, S. et al. The effect of malaria control on Plasmodium falciparum in Africa between 2000 and 2015. Nature 526, 207–211 (2015).

World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1484818/retrieve (2022).

World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2016. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1069305/retrieve (2016).

World Health Organization. World Malaria Report 2017. World Health Organization https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1091608/retrieve (2017).

Zhang, Y., Bi, P. & Hiller, J. E. Meteorological variables and malaria in a Chinese temperate city: A twenty-year time-series data analysis. Environ. Int 36, 439–445 (2010).

Ryan, S. J., Lippi, C. A. & Zermoglio, F. Shifting transmission risk for malaria in Africa with climate change: A framework for planning and intervention. Malar. J. 19, 170 (2020).

Parihar, R. S., Bal, P. K., Saini, A., Mishra, S. K. & Thapliyal, A. Potential future malaria transmission in Odisha due to climate change. Sci. Rep. 12, 9048 (2022).

Kim, Y. et al. Malaria predictions based on seasonal climate forecasts in South Africa: A time series distributed lag nonlinear model. Sci. Rep. 9, 17882 (2019).

Ren, Z. et al. Predicting malaria vector distribution under climate change scenarios in China: Challenges for malaria elimination. Sci. Rep. 6, 20604 (2016).

Diouf, I. et al. Impact of future climate change on malaria in West Africa. Theor. Appl Climatol. 147, 853–865 (2022).

Ngarakana-Gwasira, E. T., Bhunu, C. P., Masocha, M. & Mashonjowa, E. Assessing the Role of Climate Change in Malaria Transmission in Africa. Malar. Res Treat. 2016, 7104291 (2016).

Ikeda, T. et al. Seasonally lagged effects of climatic factors on malaria incidence in South Africa. Sci. Rep. 7, 2458 (2017).

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs & Population Division. World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results. https://desapublications.un.org/file/989/download (2022).

Hay, SI., Guerra, CA., Tatem, AJ., Atkinson, PM. & Snow, RW. Urbanization, malaria transmission and disease burden in Africa. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 3, 81–90 (2005).

Siraj, A. S. et al. Altitudinal changes in malaria incidence in highlands of Ethiopia and Colombia. Science (1979) 343, 1154–1158 (2014).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Agency for International Development & US Department of State. President’s Malaria Initiative: Rwanda Malaria Operational Plan FY 2017. https://www.pmi.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/fy-2017-rwanda-malaria-operational-plan.pdf (2016).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Agency for International Development & US Department of State. President’s Malaria Initiative: Rwanda Malaria Operational Plan FY 2016. https://www.pmi.gov/fy-2016-rwanda-malaria-operational-plan/ (2015).

Karema, C. et al. History of malaria control in Rwanda: Implications for future elimination in Rwanda and other malaria-endemic countries. Malar. J. 19, 365 (2020).

Udani Samarasekera. Climate change and malaria: predictions becoming reality. Lancet 402, 361–362 (2023).

Lyons, C. L., Coetzee, M. & Chown, S. L. Stable and fluctuating temperature effects on the development rate and survival of two malaria vectors, Anopheles arabiensis and Anopheles funestus. Parasit Vectors 6, (2013).

Nissan, H., Ukawuba, I. & Thomson, M. Climate-proofing a malaria eradication strategy. Malar. J. 20, 190 (2021).

Habtamu, K., Petros, B. & Yan, G. Plasmodium vivax: the potential obstacles it presents to malaria elimination and eradication. Trop. Dis. Travel Med Vaccines 8, 27 (2022).

Sutherst, R. W. Implications of global change and climate variability for vector-borne diseases: generic approaches to impact assessments. Int J. Parasitol. 28, 935–945 (1998).

Jetten, T. H., Martens, W. J. M. & Takken, W. Model Simulations To Estimate Malaria Risk Under Climate Change. J. Med Entomol. 33, 361–371 (1996).

Hay, S. I. et al. Climate change and malaria resurgence in East African highlands Europe PMC Funders Group. Trends Parasitol. 18, 530–534 (2002).

Ermert, V., Fink, A. H., Morse, A. P. & Paeth, H. The impact of regional climate change on malaria risk due to greenhouse forcing and land-use changes in tropical Africa. Environ. Health Perspect. 120, 77–84 (2012).

Nabi, S. A. & Qader, S. S. Is global warming likely to cause an increased incidence of malaria? Libyan J. Med. 4, 18–22 (2009).

Zhou, G., Minakawa, N., Githeko, A. K. & Yan, G. Association between climate variability and malaria epidemics in the East African highlands. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 2375–2380 (2004).

Laneri, K. et al. Dynamical malaria models reveal how immunity buffers effect of climate variability. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 8786–8791 (2015).

Cazelles, B., Cazelles, K., Tian, H., Chavez, M. & Pascual, M. Disentangling local and global climate drivers in the population dynamics of mosquito-borne infections. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf7202 (2023).

Mccarthy, J. J., Canziani, O. F., Leary, N. A., Dokken, D. J. & White, K. S. Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report (Cambridge University Press, 2001).

Parham, P. E. & Michael, E. Modeling the effects of weather and climate change on malaria transmission. Environ. Health Perspect. 118, 620–626 (2010).

Gebrechorkos, S. H., Hülsmann, S. & Bernhofer, C. Changes in temperature and precipitation extremes in Ethiopia, Kenya, and Tanzania. Int. J. Climatol. 39, 18–30 (2019).

Patz, J. A. & Olson, S. H. Malaria risk and temperature: Influences from global climate change and local land use practices. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 5635–5636 (2006).

Paaijmans, K. P. et al. Influence of climate on malaria transmission depends on daily temperature variation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 15135–15139 (2010).

Okunlola, O. A. & Oyeyemi, O. T. Spatio-temporal analysis of association between incidence of malaria and environmental predictors of malaria transmission in Nigeria. Sci. Rep. 9, 17500 (2019).

Cohen, J. M., Okumu, F. & Moonen, B. The fight against malaria: Diminishing gains and growing challenges. Sci. Transl. Med 14, eabn3256 (2022).

Kateera, F. et al. Malaria parasite carriage and risk determinants in a rural population: A malariometric survey in Rwanda. Malar. J. 14, 16 (2015).

Rwanda Ministry of Health. Rwanda Malaria Strategic Plan 2020–2024. https://www.rbc.gov.rw/fileadmin/user_upload/report23/Rwanda%20Malaria%20Strategic%20Plan%202020-2024.pdf (2020).

Imasiku, K. & Ntagwirumugara, E. An impact analysis of population growth on energy-water-food-land nexus for ecological sustainable development in Rwanda. Food Energy Secur 9, e185 (2020).

Tompkins, A. M. et al. A dynamical climate-driven malaria early warning system evaluated in Uganda, Rwanda and Malawi. Malar. J. 13, P99 (2014).

Rulisa, S. et al. Malaria Prevalence, Spatial Clustering and Risk Factors in a Low Endemic Area of Eastern Rwanda: A Cross Sectional Study. PLoS ONE 8, (2013).

Hay, S. I., Guerra, C. A., Tatem, A. J., Noor, A. M. & Snow, R. W. The global distribution and population at risk of malaria: past, present, and future. Lancet Infect. Dis. 4, 327–336 (2004).

Dalrymple, U., Mappin, B. & Gething, P. W. Malaria mapping: Understanding the global endemicity of falciparum and vivax malaria. BMC Med. 13, 140 (2015).

Kapwata, T. & Gebreslasie, M. T. Random forest variable selection in spatial malaria transmission modelling in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa. Geospat Health 11, 434 (2016).

Tebaldi, C. et al. Climate model projections from the Scenario Model Intercomparison Project (ScenarioMIP) of CMIP6. Earth Syst. Dyn. 12, 253–293 (2021).

Qing, Y., Wang, S., Zhang, B. & Wang, Y. Ultra-high resolution regional climate projections for assessing changes in hydrological extremes and underlying uncertainties. Clim. Dyn. 55, 2031–2051 (2020).

Jiang, T. et al. Gridded datasets for population and economy under Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Science Data Bank https://doi.org/10.57760/sciencedb.01683 (2022).

Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach. Learn. 45, 5–32 (2001).

Hastie, T., Friedman, J. & Tibshirani, R. The Elements of Statistical Learning Mining, Inference, and Prediction. Springer (2009).

Yang, Y. Source data supporting the Article “ Malaria transmission risk is projected to increase in the highlands of Western and Northern Rwanda ” [Data set]. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13143289 (2024).

GADM Database of Global Administrative Boundaries (version 3.4). [Data set]. GADM. https://gadm.org/data.html (2018).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42222503) and the Ministry of Education, Singapore, under its MOE AcRF Tier 3 Award MOET32022-0006.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.Y. designed research; L. Z., J. N. and Y. Y. performed research; L.Z. and J.N. analyzed data; and L. Z., J. N., Y. Y., S. Y., Y. Z., M. W., P. U., Z. X., H.C. H., M. G., S. T. and S. L. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth & Environment thanks Cyril Caminade, Ahmad Ali Hanafi-Bojd and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Paula Ribeiro Prist and Martina Grecequet. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zong, L., Ngarukiyimana, J.P., Yang, Y. et al. Malaria transmission risk is projected to increase in the highlands of Western and Northern Rwanda. Commun Earth Environ 5, 559 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01717-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-024-01717-9